ABSTRACT

The aim of the article is to deepen the understanding of how a pedagogical model for reflecting talks can be used in order to make sustainable learning part of the daily work in the learning organization. From an interactive research approach, we have together with a project management group in a European Social Fund project worked with sustainable learning and knowledge development. Empirical data has been collected at the implementation of ten reflecting talks about sustainable equality. The results of the study lead to a strategy for how sustainable learning can become part of the daily work at a workplace. The strategy is constituted by a pedagogical model for reflecting talks, which clearly shows how sustainable learning in an organization can be structured. The core of the pedagogical model for the reflecting talks where both practically applied and theoretically anchored knowledge are important components. The learning process is based on observation, reflection, analysis and discussion of concrete situations/events. The models rests on four basic conditions; pedagogical competence, a delimited problem area, the learning group and timeframes. The model can be used in the daily work at short dialogues or at more penetrating discussions.

Introduction

The aim of the article is to deepen the understanding of how a pedagogical model for reflecting talks can be used in order to make sustainable learning part of the daily work in the learning organization. To reach our aim, we have from an interactive research approach collected empirical material at 10 reflecting talks, which were carried out with a project management group in the European Social Fund projectFootnote1 entitled ‘Competence in Nursing and Care’.Footnote2 As sustainable equality is a prioritized area in the Social Fund project, this field constituted our focus at all the reflecting talks that were carried out with the project management group.

The definition of the study of sustainable learning departs from the Swedish strategy for sustainable development where the focus lies on respect for knowledge and democracy. Sustainable development is divided into three dimensions; the economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Sustainable learning is then related to the social dimension of sustainable development where the central matters are learning and the capacity to benefit by knowledge and tools to develop a preparedness for action and trust one’s own capacity for lifelong learning (Government report, Citation2003). Furthermore, sustainable learning is also related to Hargreaves and Flink’s (Citation2008) line of reasoning. They suggest that everything that is learnt needs to have both breadth and depth and they develop their thoughts by adding the five main pillars of learning: learning to know, learning to do, learning to be, learning to live, and learning to live sustainably.

In addition to sustainable learning, the learning organization is central in the present study. According to Argyris and Schön (Citation1996), a learning organization is characterized by identifying and correcting errors. However, individual learning is not sufficient; the learning organization must be marked by learning at both group and organization level. The learning organization should, according to Senge (Citation2006), contain the five integrated fields of mature reflecting co-workers, the co-workers having a conscious common vision, the co-workers are stimulated to engage in common learning, new thinking, and holistic thinking. Ekman (Citation2004) is critical of Senge’s identified fields, meaning that they do not work in practice. Örtenblad (Citation2007) meets the criticism with the argument that Senge does not have the intention of defining the learning organization but merely describe its conditions. Ekman (Citation2004) describes the learning organization as an organization where constant learning at all levels of the organization is central. In this context, culture is important, as it creates the foundation for mutual learning, co-operation, and striving towards common goals.

Previous research

Research on learning in organizations commonly focuses on mutual learning, team learning, or collective learning. The concept of sustainable learning is used in only a few cases. The employment of different concepts and definitions, together with the fact that this research is carried out in many disciplines, renders a summary of the current research situation difficult. One can, generally, note that most of the studies are of a qualitative self-reflecting character and that there is a relative lack of research on the effect of collective learning.

Sustainable learning, the focus of the present article, is also central in some other studies. In one of them Albinsson & Arneeson (Citation2012) develop a model where learning seminars constitute the pedagogical method for systematic work with learning in a group. In a similar way, Amundsdotter (Citation2010) has also worked with network groups, where gender was discussed and the participants reflected upon their own experiences of gender marking. Other studies depart from reflection meetings, learning talks, and analysis seminars in order to describe mutual learning within different group constellations (Gunnarsson & Westberg, Citation2007). Common to these studies is the emphasis on the importance of mutual learning to develop both the individual and the collective in organizations. Olsson Neve (Citation2006, 2013) has also developed a model for sustainable organizational learning. The aim of her model is to develop an understanding of the individual’s role in the joint organizational learning process, but also to develop concrete knowledge about a mode of procedure which leads to sustainable organizational learning.

From a diachronic perspective, Senge’s (Citation2006) research on team learning has been of great importance for research on learning in the working life. Individual co-workers can learn their work, but if the team does not learn together, the organization will not develop. Ohlsson (Citation2013) has deepened the understanding of the interplay between the individual’s and the collective’s learning by identifying several processes of interplay and communication. According to Ohlsson (Citation2013), the decisive factor for the interplay and the learning is the degree of joint reflection. At the same time, he emphasizes that it is not only the verbal communication which is decisive for the learning; a concrete action that can be mutually observed is also required. He calls this the action dimension of common learning.

Knapp (Citation2010) also uses the concept of team learning but emphasizes that it is often used synonymously with the concept of collective learning. Here is a clear similarity with Agyris and Schön’s (1996) definition of mutual learning in organizations, their point of departure being that the learning starts when the separate individual in an organization reflects upon something which she/he has experienced. When the individual communicates this experience-based knowledge, individual, collective, and organizational learning start (Argyris, Citation1999; Argyris & Schön, Citation1996). The organization must create conditions for the learning and the organization culture must be permeated by norms and basic assumptions on what knowledge the organization is in demand of. The learning is also included in the learning process, single-loop learning (unreflected learning) and double-loop learning (a conscious, critical reflection, assessment, and evaluation of actions). Double-loop learning is required when the knowledge is not sufficient to understand mistakes or weaknesses in the daily work. Possibilities are opened to rectify processes, question previous knowledge, formulate questions, and discover new perspectives (Argyris, Citation1993; Argyris & Schön, Citation1996). Swieringa and Wierdsma (Citation1992) provide a third loop, as they suggest that changes in organizational behaviours take place at three different levels. Single-loop learning leads to a change of rules and double-loop learning deepens insights, whereas triple-loop learning, finally, is required at the change of principles.

In later research, McCarthy and Garavan (Citation2008) have shown the importance of meta cognition in the team. They bring out the value of the social process in which common thinking takes place. Together, the team creates an awareness of how they understand their work, of the existing basic assumptions, and what the team needs to learn.

There is also research directed at why collective learning processes do not arise. Both Granberg (Citation2003) and Janis (Citation1982) show that a learning process that has failed to appear can be understood by means of the concept of groupthink. The concept illustrates a closed unit where nobody in the group dares to be critical or ask questions. Brocbank and McGill (Citation1998) are also critical and warn against blind faith in the importance of reflection for collective learning, meaning that self-reflection can lead to the individual and the group being seduced by their own narratives, missing the critical reflection.

Several of the presented studies form the basis of the development and the theoretical deepening of our pedagogical model for reflecting talks.

Theoretical framework

Reflection is a central concept in this study and it is a concept that is used frequently in different pedagogical contexts. Students and professionally active individuals are requested to reflect upon different phenomena or experiences. So what are they then expected to do? One basic idea is to see reflection as developing possible interpretations, leading to new combinations, new structures, or new ways of understanding contexts (Grimmet & Ericksson, Citation1988). Dewey (Citation1933/1989) carries out a similar argumentation about the situation being the core of the reflection. This focus departs from a pragmatic tradition which emphasizes the reflection as contributing to solutions of problems and as leading to development. Schön (Citation1983) also points out that the situation is the most important thing. The practitioner apprehends the situation, examines and evaluates it in order to reflect upon it, and presents new thoughts or solutions in the next step. Hatton and Smith (Citation1995) describe the reflection from different levels. The first is descriptive and it contains an account of an occurrence or situation.Then the account is explained through the adding of the individual’s own reflection and constituted by an inner reflective dialogue and a reasoning around alternative solutions or consequences. Finally, we find the critical reflection with the consideration of a larger context; for example, at the group or community level. In their model, Hatton and Smith illustrate the difference between the reflection as an inner reflective dialogue and critical reflection.

To the reflecting practitioner, the different levels of the reflection, in combination with the significance of language, mean an anchoring in the everyday situations. The reflection is then characterized by the search for an understanding of complex interactions in order to find new alternatives of actions in the next step. Reflection is thereby seen as a learning process where the purpose is to bring together different elements into a new understanding by moving between observation and thoughts at different levels in order to relate these to each other at a later stage (Moon, Citation2000). To understand the importance of reflection for learning, we also bring in Schön’s (Citation1983) discussion on the concept of reflection-in-action from knowledge theory. According to Schön, the concept covers both reflection on what one has done and a more general thought about what one does. Furthermore, the dividing line between knowledge-in-action and reflection-in-action is constituted by the first-mentioned being a condition for the second one. The learning process and the learning in action are also central matters in Schön’s (Citation1983) reasoning. The reflecting practitioner learns, to quote John Dewey (Citation1933/1989), by doing and by talking about her/his reflections.

The concept of reflection is central to the definition of experience-based learning, which deals with what we experience and what we then do with our experiences (Larsson, Citation2004). In order to understand experience-based learning, the description of four fundamental learning forms is often used: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. The learning forms describe how the experience leads to reflection and how understanding is deepened through abstract concepts and experimentation (Kolb, Citation1984). The experience-based learning can also be related to Larsson’s (Citation2004) definition of organizational learning which presupposes principles, structures, activities, and processes for the individual to learn in collaboration with others.

Another central concept in this study is the talk. A fundamental idea is that the talk as pedagogical method creates a condition for development and learning by letting different interpretations meet. Ideas on the connection between language, thinking, and learning were developed already during the last century. The Socratic dialogue is a starting point for Molander’s (Citation1997) description of an ideal for the ongoing talk which comprises both theoretical and practical matters. The central idea is that knowledge, through dialogue, is further developed through the gaining of clarity about oneself, one’s thoughts, one’s knowledge, and one’s ignorance. The ideal type of dialogue is formed from the I–you perspective, resulting in a we that can develop a common, mutual knowledge creation. Vygotskij (Citation1934/2001) also suggests that when we speak, our thinking is developed. Senge (Citation2006) relates the dialogue to team learning, meaning that in a group of equals, the individual can expand her/his understanding. Also, Argyris (Citation1993) and Marsick and Watkins (Citation2015) emphasize how the talk and dialogue in small groups can promote critical reflection and thereby learning.

Research approach

The interactive research approach

The methodological considerations of the study departed from the project group’s work with a systematization of the learning. The choice of the interactive research approach was natural as it made it possible for us to try and develop a suitable pedagogical model together with practitioners. The approach has been used by several researchers in similar pedagogical research (Amundsdotter, Citation2010; Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012; Arnesson & Albinsson, Citation2012).

Interactive research and consensus-oriented action research both have their base in the hermeneutical research ideal where a community of values and the close relation between participants and researchers are emphasized. The interactive research process in our study meant that we, together with the five participants in the project management group for a Social Fund project, started carrying out reflecting talks. We had already collaborated with the group for several months, so closeness and dialogue were natural elements in our meetings, and the roles between practitioners and researchers were partly erased. We looked upon the collection of empirical material as an ongoing process during the entire research project, but it also turned into something more than just the gathering of empirical material (cf. Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2011; Hansson, Citation2003; Svensson, Ellström, & Brulin, Citation2007). Our approach as researchers during the entire research process stressed collaboration, closeness, and dialogue.

The implemented reflecting talks became a framework for systematic dialogue, reflection, and a mutual learning process. The dialogue created unbiased meetings between different perspectives, which deepened the knowledge creation. We exchanged and developed our reflections, and our role as researchers was oriented at listening, creating a learning environment, and asking questions. Our ambition was to attain a close, subject–subject relation and to take over the actor’s perspective and understand her/his thoughts and reality (cf. Cohen et al., Citation2011).

The interactive research approach should also be discussed from the concept of reliability. Critics suggest that reliability is low when researchers and participants work closely together during the entire research process, and the researchers become too involved and become part of the reality that is to be studied (Svensson et al., Citation2007). This criticism must be taken seriously and during the whole research process we have discussed what the closeness meant to us as researchers, how we approached the pendulation between closeness and distance, and how we maintained a critical approach. The reliability in this study is, thus, based on the ongoing discussion, our methodological and theoretical knowledge and experience, and the fact that the empirical material was collected through method triangulation in the form of observations and qualitative interviews/talks (cf. Aagaard Nielsen & Nielsen Steen, Citation2006; Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012; Arnesson & Albinsson Citation2012; Cohen et al., Citation2011; Svensson et al., Citation2007).

Collection of data

The empirical material was collected at 10 reflecting talks about sustainable equality and they were carried out in the project management group in a Social Fund project. In the project, we worked with learning evaluations. The project management group consisted of five women aged 33–64. The women were an administrative manager, an occupational therapist, an area manager, an economist, and a nurse. Together we started developing a pedagogical model where the reflecting talk made up the focus.

The observations were carried out at the reflecting talks and on these occasions we as researchers assumed the role of both active and passive observers. The active role departed from us being pedagogical leaders for the talks and in that role we asked questions so that together with the participants we could develop a model for the reflecting talks. We were also passive, and thus listening, observers. Our ambition was to write exhaustive field notes about the dialogue and the social interaction within the group. This meant that in that phase we did not make any selection; everything that occurred was deemed important. After each talk, we also summarized our own reflections (Patton, Citation2015).

After the tenth talk, individual semi-structured qualitative talks were carried out with the participants. These talks were informal and flexible and can, thereby, be described as talks between two equivalent individuals. We collected the informants’ experiences and understanding of the content and structure of the reflecting talks. Furthermore, during the interview/talk we worked with the development of a joint model for reflecting talks.

Results: a pedagogical model for reflecting talks

From an interactive research approach, we have in this study together with a project management group further created a pedagogical model for reflecting talks. The inspiration for the model is drawn from Albinsson & Arnesson (Citation2012), Moon (Citation2000), and Hatton and Smith (Citation1995).

The purpose of the model is to use it to create a recurrent systematic learning process where both practically employable and theoretically anchored knowledge make up the focus.

Reflecting talks in relation to learning can be understood as a process from perception of a phenomenon to processing in various steps.

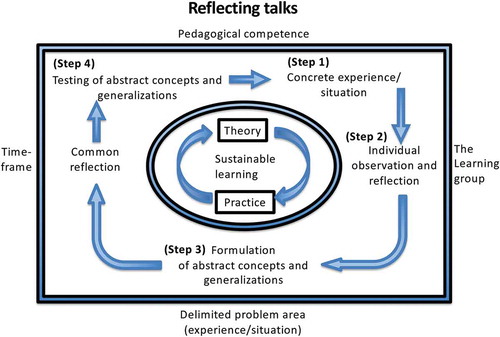

()The hub of the model contains the sustainable learning illustrated as a wheel in constant movement where theory and practice are integrated. The hub is surrounded by a learning process constructed from reflection in five different steps. The pedagogical model rests on the four basic conditions of pedagogical competence, the learning group, a delimited problem area, and time limitations (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012). A description of the five different steps of the learning process follows below. The first two steps are the same as in the ‘Learning platform for sustainable learning’ (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012), whereas steps three, four, and five are a development and simplification of the model. The model has also been developed with a deepened theoretical anchoring. These are the five steps of the learning process:

Step 1: concrete experience/situation

The learning process was initiated by each participant departing from a concrete situation/occurrence and preparing for the reflecting talk by reading, observing, and reflecting on the content on a rather superficial level based on questions like ‘What happens?’ or ‘What do I see?’ (Dewey, Citation1933/1989; Grimmet & Ericksson, Citation1988; Ohlsson, Citation2013; Schön, Citation1983).

Step 2: individual observation and reflection

Step 2 is constituted by a process of searching for understanding in order to create some form of meaning in the situation/occurrence. A condition for the reflection process is attention and perception of the course of events. ‘Why does this happen?’, ‘What does it mean?’, ‘What do I feel?’ and ‘Why do I feel like this?’. The reflection aims, then, ultimately to bring together one’s own experience-based knowledge with different phenomena which do not immediately present themselves together (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012; Dewey, Citation1933/1989; Grimmet & Ericksson, Citation1988; Moon, Citation2000; Schön, Citation1983). The individual reflection is also meant to lead to a deconstruction of one’s own thoughts, feelings, assumptions that are taken for granted.

Step 3: formulation of abstract concepts and generalization

Step 3 is about deepening the reflection in relation to previous experiences by adding abstract concepts and generalizations. That which is general is, thereby, made clear in the specific situation. The reflection can here be described as a pendulating movement between the individual reflection and theoretical explanations (Kolb, Citation1984).

Step 4: common reflection

In step four, individual understanding is used as the reflections are presented to the seminar group. This step can be seen as the starting point for the common reflection and, in the form of dialogue, the group reflects together. The group then tries to critically review and revise structures that are taken for granted and new understanding is developed and alternative interpretations are brought out (cf. McCarthy & Garavan, Citation2008).

Step 5: testing of general concepts and theories

By way of conclusion, we as researchers provided theories and abstract concepts, and the generalizations were tested and new interpretations were provided.

The model illustrates a learning process where the reflection in the centre can be interpreted by means of the concepts of phenomenon – understanding – conclusion/action (cf. Koppfeldt, Citation2005). In conformity with several reflection theories, the phenomenon constitutes the core of the reflection (Dewey, Citation1933/1989; Ernsheimer, Citation2005; Schön, Citation1983). The concrete situation/occurrence in our reflecting talks can be exemplified through individual experiences, the articles and reports which the participants read, or photographs upon which they reflected before each talk. Understanding refers to how the participants first individually and then in groups observe a concrete situation and reflect on how they experience the situation based on their review and evaluation of the situation. Thereafter they present some form of conclusion or solution and give suggestions for a new way of acting. To deepen understanding of the learning process, a model of experiential learning is added, which, besides the focus on the observation and reflection on a concrete situation, leads to a formation of concepts and generalizations which are implemented and tested in a new situation (Ernsheimer, Citation2005).

To understand the importance of the common reflection for learning, we also depart from Engeström’s socio-cultural perspective on that which takes place in the social interplay between people, that is, the collective learning (Chailin, Hedegaard, & Juul Jensen, Citation1999). In this perspective, the importance of language for learning is also emphasized. Through language, Vygotskij suggests the individual creates meaning and the relation between thought and language is dialectic (Vygotskij, Citation1934/2001). Säljö.’s (Citation2000) reasoning about how language liberates us from reality, thereby creating possibilities for meta thinking, can also be transferred to the definition of reflection of this study. Wertsch (Citation1993) adds the concept of social language, defining this as different ways of speaking and making oneself understood in different groups; for example, in disciplines or professional groups. In this way, all utterances are connected to a sociocultural environment. At the reflecting talks, the usage of language in dialogue is central. Bakhtin (Citation1986) sees language as dialogic and he means that language is used to create relations. The utterance is formulated with an expectation of reaction from the receiver. The receiver interprets the utterance and actively gives a response (Dysthe, Citation2003). In order to deepen the understanding of the importance of dialogue for learning, a perspective from activity theory is also added and learning is thereby placed in relation to the social structure and culture. This approach posits the individual as existing in society and society as existing in the individual. Learning is described as something which the actor acquires through an active dialectic process between individuals, the social others, and society.

The results of the study show that the model is practically applicable and a common understanding was that the model was well suited to deepen knowledge within the learning organization as it clearly describes the learning process in five steps. To work with the material in several steps was brought out by the participants as something very good. The individual reflection led to an experience of ‘having something to say that is important’ before the common dialogue. This creates self-confidence and the feeling that everyone has something to contribute to the group’s collective knowledge creation. One participant pointed out that the talks in the group had worked as an ‘alarm clock’ to her as she believed that she had more knowledge and was more aware than she actually was. Her interest in sustainable equality was strengthened and together with the others she wanted to deepen her knowledge further. The talks in the group, as part of the learning process, can be interpreted through Dixon’s (Citation1994) definition of collective learning. He means that collective learning is created in a context where specific experiences are generalized and the individual’s ideas become accessible and understood. The common understanding develops into knowledge in the group.

The pedagogical model for reflecting talks is surrounded by a structure consisting of four prerequisites: the learning group, pedagogical competence, a delimited problem area, and time frames (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012).

The learning group

Previous research shows that the conversation, the dialogue, and the reflection in the small group are central for learning (Argyris, Citation1993; Marsick & Watkins, Citation2015; Senge, Citation2006). According to activity theory, the driving force in the learning group is the individual’s need of community, belonging, and of learning from others. The common learning process is concretized through communication, where reflection and analysis are communicated through language (Knutagård, Citation2002). Albinsson & Arnesson (Citation2012) develop these thoughts by adding the notion that collaboration in the learning group leads to a deepening of both individual and collective knowledge. An important condition, however, is that the individual in the group must feel trust and security, and the learning environment must be permeated by a constructive and forward-looking climate. At our talks it was clear that it was important to listen to ‘different voices’ and that the premise of common knowledge creation rested on both the participants’ and the researchers’ perception of each other’s knowledge and experiences as valuable.

A success factor at our reflecting talks was the fact that the group consisted of only five people. This resulted in the participants feeling that there was speaking space and that everybody, thus, had the possibility to express ideas. Similar to Senge’s (Citation2006) research, we could see how the group practised collaboration and how it developed into being a well-functioning group with a willingness to listen to and learn from each other, which is a condition for a deepening of both individual and collective learning. According to the participants, our long pedagogical experience and deep interest and engagement in sustainable equality was of great importance for the climate of learning in the group.

At our first reflecting talks, the level of knowledge in the group was variable. One participant had long experience of equality work and two participants had an interest but little theoretical knowledge. The two youngest members of the group were not very interested; they tended to question ‘why so much time would be dedicated to sustainable equality’. The oldest participants of the group had, for natural reasons, more experience-based knowledge (cf. Wahl, Citation2018). The participants with a great interest in equality were driving and had a decisive importance for the group process and the mutual learning. At the beginning, the participants’ diverging ideas resulted in everybody having to ‘sharpen’ their arguments. Gradually, in relation to the knowledge becoming deeper, the argumentation changed and the group increasingly started to agree on the importance of knowledge of sustainable

equality both in society and in the working life.

Our task as researchers was to listen, ask deepening questions, and lead the discussion so that everybody could be heard. The learning climate in the group was very good and there was a willingness to listen, learn, and share experiences and knowledge. The talks were concluded by the researchers adding some theoretical concept or theoretical perspective in order to seek an understanding of the contents of the material on a more abstract level. Examples of these theoretical concepts were sex, gender, equality, patriarchy, superiority, subordination, gender power systems, political equality goals, Hirdman’s gender theory, and R. W. Cornell’s gender hierarchy.

Pedagogical competence

Pedagogical competence is a condition for individual and collective competence to be developed in the group. The pedagogical approach gives legitimacy to leading the learning process from an outlook on people that emphasizes how the individual actively seeks knowledge and is creative, engaged, and questioning. The learning then departs from an active approach to the group and the surrounding world, and the focus is directed at the seeking of contexts, a deepening of understanding, and new solutions (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012). This approach corresponds well with the role that we assumed at the reflecting talks. Our task was to create a structure for the talks, where every individual had her space and could express her reflections, but our task was also to create space for the common reflection and the theory connection. Schön’s (Citation1983) theoretical concept of knowledge was a guiding principle to help the individual to deepen the understanding of the concrete situation from the perspective of both knowledge-in-action and reflection-in-action. This meant that together with the participants we aimed at creating a climate where it was beneficial to be problematizing, questioning, and critical, to promote reflection and fresh ideas. The need for pedagogical competence and thus pedagogical leadership receives support from Brocbank and McGill’s (Citation1998) research on risks for reflection that fails to appear unless the individual is given pedagogical leadership. Hickson (Citation2011) also stresses the importance of guidance to steer the novice towards reflection and exploration on how and why different factors in a concrete situation interact with each other. Our pedagogical experience was challenged during the first talks as a result of the group members’ diverging ideas on sustainable equality. It was important to let everybody express her ideas and important for us not to become too steering and/or limiting in relation to those who viewed sustainable equality from a position different to ours. The participants pointed out that our theoretical knowledge was valuable for the common knowledge creation.

A delimited problem area

There are certain similarities between the case study and the delimited problem area. The purpose in both cases is to deepen the learning in regard to a specific phenomenon departing from an experience (Albinsson & Arnesson, Citation2012; Haigh, Citation2008). The delimited problem area can also be assigned to Schön’s (Citation1983) discussion on reflection-in-action.

The delimited problem area can in our study be illustrated by us handing out different articles to the participants before the opening seminars. The fact that the articles were current and often obtained from the daily press was understood as important for the participants’ motivation to read and analyse the articles. The participants’ motivation was further strengthened when before the second reflecting talks they had to be responsible for the choice of material. On one occasion, this resulted in analysing our own experiences from working life and, on another occasion, analysing images of Lego boxes, photographs, and films from YouTube from an equality perspective.

Time frames

According to Cahill, Turner, and Barefoot (Citation2010), established time frames constitute a condition for active learning with interaction between personal, emotional, and cognitive aspects. The time aspect is developed by Molander who suggests that reflection means ‘to take one step back to see and reflect upon oneself and what one does, in order to get perspective on a situation’Footnote3 (Molander, Citation1996, p. 143). Döös (Citation1997) uses the term of ‘reflection space’ to emphasize the importance of time for reflection. Transferred to our reflecting talks, this meant that we made sure that each participant had the possibility to, in the first hand, allocate working time to their reflection on a delimited problem area. In the next step, our reflecting talks were carried out during a limited, predetermined period of time. Our experience is that when everybody is well familiar with the pedagogical model, the time allocated for reflection talks may vary depending on what the talk is about. Some talks may be carried out in 15 minutes whereas others may require 60 minutes. The fact that the reflecting talks were carried out regularly every fortnight during the entire spring was a decisive factor for the good results. One participant explained this by stating that the knowledge needs to ‘mature’ for understanding to be attained.

To the time frames we add Giddens’ (Citation1991) concept of space–time. He uses the concept pair to describe a context for the social matters, where space constitutes both tools and resources for social action. Space creates possibilities for reflection when different experiences meet, collide, or collaborate. Our participants discussed the importance of space and they explained that their own reflection required an undisturbed environment. To avoid disturbance, someone chose to take a walk, whereas someone reflected best in the car or on the train.

Reflections and conclusions

The most important conclusion of the study is that the reflecting talk is well suited to the everyday work with the development of sustainable learning in a learning organization. The unique thing about the model is that it is practically employable as the talks are surrounded by a clear structure in the concrete work with reflection and learning. The results of the study show that structure is an important condition for the deepening of individual, collective, and organizational knowledge. The clarity and simplicity of the model makes it easy to learn and thus it becomes an important tool to create structure at both short talks and longer dialogues where the purpose in both cases is to develop mutual sustainable learning at a workplace. The reflection is the central matter in the learning process and it can be described as a pendulation between phenomenon/situation – understanding – conclusion/action. By describing reflection in practice as a research process, the elements and forward-looking character of the reflection is made visible. The model is surrounded by the prerequisites of the learning group, pedagogical competence, a delimited problem area and time frames. The learning group, with the meeting between individuals, the dialogue, the reflection, and the willingness to learn from each other, is central, and mutual learning leads to the integration of practically employable and theoretically anchored knowledge. Pedagogical competence gives legitimacy to lead the learning process and in practice transform a view of society with a dialectic relation between individual and structure, a humanistic outlook on people and a view of learning as an active, creative process leading to action. Leading the learning process means to give structure and driving force to the individual, collective, and organizational learning from a pedagogical approach. The attainment of collective learning, however, requires that the problem area is engaging to and accepted by the participants. This was a challenge in our study as the interest in, and the knowledge level of, sustainable equality varied so much. The motivation and the driving force in some of the participants became a decisive factor here. We could clearly follow how collective learning was developed as a result of the individual preparation which led to reflection on a level which could then be deepened by the other group members asking questions and adding their own reflections, concepts, and theories. The learning in practice then took place in a dialectic process between individual, group, and society. Time frames is the fourth prerequisite. Allocating time for the learning could appear as an obvious matter, but it only has value if the time is actually used for that for which it was intended. One experience was that the participants at the concluding reflecting talks were significantly more prepared in comparison to the introductory talks.

The second conclusion is that sustainable learning in an organization must depart from a conscious strategy in order for the learning to become part of the everyday work. The first part means, as in this study, a structured learning based on the pedagogical model for reflecting talks. The second part of the strategy is a common understanding of sustainable learning. This study defines sustainable learning as based on social sustainability, where knowledge, understanding, skills, capacity, ability, values, and approaches in the learning organization are created from a systematic reflection on the individual and group levels. The common reflection and the analysis give possibilities for correction, change, creativity, and new thinking in the daily work. Sustainable learning and a sustainable approach are not simple things, but necessary for meeting the challenges that exist in the working life.

The focusing on sustainable learning within organizations as a constantly active process must also be problematized. Illeris (Citation2001) suggests that uninterrupted learning with demands for change and development result in the individual becoming vulnerable and their identity is put to the test. Also, Ohlsson (Citation2001) points out that learning should not merely be described positively. An image is created of harmony prevailing in the learning organization, and the imbalance of power between co-workers and managers is rendered invisible. One cannot disregard the fact that it is the managers who direct what to learn and which development it is that should be rewarded. Coopey’s criticism calls attention to the fact that learning in organizations is directed by persons in key positions at the expence of the co-workers' influence and particiapation (Starkey et al, Citation2005). Ellström (Citation1996) is also critical and argues that learning, instead, is promoted if conflicts and oppositions are visible and form the point of departure for critical reflection. Brocbank and McGill (Citation1998) warn against blind faith in the importance of reflection for collective learning and suggest that self-reflection can lead to the individual and the group being seduced by their own stories, missing the critical reflection. One risk is also that the reflection and the story will become merely descriptive without practising and supervision. If we apply these arguments to the present study, we see the describe risks. Everyone was aware of the fact that there was, within the group, an imbalance of power. We could also follow how disagreement about sustainable equality was an important driving force for reflection and learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kerstin Arnesson

Kerstin Arnesson is Associater Professor and Senior Lecturer at Linnaeus University, Sweden. Her research is in learning in practice, learning organization, sustainable learning, organization within the public sector, equality and gender perspectives.

Gunilla Albinsson

Gunilla Albinsson is Associater Professor and Senior Lecturer at Linnaeus University, Sweden. Her research is in reflective learning in practice, common learning process, relationship between organization, gender perspectives and social relations.

Notes

1. European Social Fund. www. http://ec.europa.eu/social.

2. The main purpose of the project ‘Competence in Nursing and Care’ (KIVO) is to offer competence development to the personnel so that they can increase their employability and handle the demands for readjustment of the working life. The work with competence development is done to facilitate the individual development of the capacity for new thinking, flexibility, and mobility, and the work between and across section borders. The objective is also to design a more target-group-adapted system for competence development, a centre for flexible learning in healthcare.

3. Our translation.

References

- Aagaard Nielsen, K., & Nielsen Steen, B. (2006). Methodologies in action research. In K. Aagaard Nielsen & L. Svensson (Eds.), Action research and interactive research. Beyond practice and theory (pp. 63–87). Maastricht: Shaker Publishing.

- Albinsson, G., & Arnesson, K. (2012). Team learning activities: Reciprocal learning through the development of a mediating tool for sustainable learning. The Learning Organization. The International Jounal of Critical Studies in OrganizationalLearning, 19(6), 456–467.

- Amundsdotter, E. (2010). Att framkalla och förändra ordningen [To Provoke and Change the Order]. Stockholm: Gestalthuset Förlag.

- Argyris, C. (1993). Knowledge for action. A guide to overcoming barriers to organizational change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Argyris, C. (1999). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1996). Organizational learning II. Theory, method and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Arnesson, K., & Albinsson, G. (2012). Integration of theory and practice in higher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 5, 370–380.

- Bakhtin, M. (1986). The problem of speech genres. In C. Emerson & M. Holquist (Eds.), Speech genres and other late essays (pp. 60-102). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Brocbank, A., & McGill, I. (1998). Facilitating reflecting learning in higher education. Bukingham: Open University Press.

- Cahill, J., Turner, J., & Barefoot, H. (2010). Enhancing the student learning experience: The perspective of academic staff. Educational Research, 52(3), 283–295.

- Chaiklin, S. Hedegaard, M., & Juul Jensen, U. (Eds.). (1999). Activity theory and social practice. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Dewey, J. (1933/1989). The later works, 1925–1953. Essays and how we think. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dixon, N. (1994). The organizational learning cycle. How can learn collectively. London: McGraw-Hill.

- Döös, M. (1997). The qualitative experience. Learning at disruption in automatized production. Stockholm: Department of Pedagogy, Stockholm University.

- Dysthe, O. (Eds). (2003). Dialog samspel och lärande [Dialogue, interplay and learning]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Ekman, A. (2004). Lärande organisationer i teori och praktik: Apoteket lär [Learning organizations in theory and practice: The pharmacy learns]. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Ellström, P.-E. (1996). Rutin och reflektion. Förutsättningar och hinder för lärande i dagligt arbete. In I. P.-E. Ellström (Ed.), Livslångt lärande [Lifelong learning] (pp. 142–179). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Ernsheimer, P. (2005). Reflektionsteorier. [Reflection theories]. In P. Emsheimer., H. Hansson., & T. Koppfeldt. (Eds.), Den svårfångade reflektionen [The elusive reflection] (pp. 35–41). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Government report 192003/04:129. (2003). A Swedish strategy for sustainable development - economic, social and environmental. Stockholm: The Swedish Goverment.

- Granberg, O. (2003). Hinder för kollektivt lärande i team [Obstacles to collective team learning]. Stockholm: Stockholm universitet: Pedagogiska institutionen.

- Grimmet, P., & Ericksson, G. (Eds). (1988). Reflection in teacher education. New York: Pacific educational press.

- Gunnarsson, E., & Westberg, H. (2007). Att kombinera ett könsperspektiv med interaktiv forskningsansats: En utmaning i praktik och teori [Combining a gender perspective with an interactive research approach: A challenge in practice and theory]. HSS 07: Jönköping: Higher Education Institutions and Society in Collaboration, Jönköping University.

- Haigh, J. (2008). Integrating progress files into the academic process. Active Learning in Higher Education, 9(1), 57–71.

- Hansson, A. (2003). Practically. Action Research in Theory and Practice – in the wake of LOM ( Doctoral dissertation). University of Gothenburg: Department of Sociology.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2008). Hållbart ledarskap i skolan [Sustainable leadership in school]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching & Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49.

- Hickson, H. (2011). Critical reflection: Reflecting on learning to be reflective. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 829–839.

- Illeris, K. (2001). Lärande i mötet mellan Piaget, Freud och Marx [Learning in the meeting between Piaget, Freud and Marx]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Janis, I. (1982). Groupthink. Boston: Houghton Mifflin company.

- Knapp, R. (2010). Collective (team) learning process models: A conceptual review. Human Resource Development Review, 9(3), 285–299.

- Knutagård, H. (2002). Introduktion till verksamhetsteori [Introduction to activity theory]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Koppfeldt, T. (2005). Bearbetning genom bildsamtal [Processing through image conversations]. In P. Emsheimer, H. Hansson, & T. Koppfeldt (Eds.), Den svårfångade reflektionen [The elusive reflection] (pp. 169–178). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Larsson, P. (2004). Förändringens villkor- en studie om organisatoriskt lärande och förändring inom skolan [The conditions of change: A study of organizational learning and change in school] ( Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm School of Economics Institute for Research (SIR).

- Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. (2015). Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. London: Taylor and Francis.

- McCarthy., A., & Garavan, T. N. (2008). Team learning and metacognition: A neglected area of HRD research and practice. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(4), 509–524.

- Molander, B. (1996). Kunskap i handling. [Knowledge in action]. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Molander, B. (1997). Arbetets kunskapsteori [Knowledge theory of work]. Stockholm: Dialoger.

- Moon, J. (2000). Reflection in learning & professional development- theory and practice. London: Kogan Page.

- Ohlsson, J. (2001). Den överhettade arbetsmänniskan [The overheated hard worker]. In I. D. Tedenljung (Ed.), Pedagogik med arbetslivsinriktning [Pedagogy with working life direction] (pp. pp. 30–66). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Ohlsson, J. (2013). Team learning: Collective reflection processes in teacher teams. Journal of Workplace Learning, 25(5), 296–309.

- Olsson Neve, T. (2006). Capturing and analyzing emotions to support organizational learning: the affect based learning matrix ( Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm University: Department of Computer and Systems Sciences.

- Olsson Neve, T. (2014). Hållbart organisatoriskt lärande [Sustainable organizational learning]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Örtenblad, A. (2007). Senge’s many faces: Problem or opportunity? The Learning Organization, 14(2), 108–122.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods- integration theory and practice. London: Sage Publications.

- Säljö., R. (2000). Lärande i praktiken. Ett sociokulturellt perspektiv [Learning in practice. A sociocultural perspective]. Stockholm: Prisma.

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner – How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

- Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization. London: Cornerstone.

- Starkey, K., Tempest, S., & McKinlay, A. (Eds.). (2005). How organizations learn: managing the search for knowledge. London: Thomson Learning.

- Svensson, L., Ellström, P.-E., & Brulin, G. (2007). Introduction – On interactive research. International Journal of Action Research, 3(3), 233–249.

- Swieringa, J., & Wierdsma, A. (1992). Becoming a learning organization. Beyond the learning curve. Reading. Massachusetts: Addison- Wesley Publishing Company.

- Vygotskij, L. (1934/2001). Thinking and language. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Wahl, A. (Eds). (2018). Det ordnar sig alltid [It always works out]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Wertsch, J. (1993). A sociocultural perspective on mental action. SPOV: Studies of the pedagogical fabric, v 20. Härnösand: Department of pedagogical text interpretation.