ABSTRACT

Reflective practice is regarded as an essential competency to maintain high clinical standards by various professional bodies and is therefore emphasised within healthcare training programmes including Clinical Psychology. Clinical supervision is seen as the most common and useful way to encourage reflective practice in healthcare professionals but there is limited evidence on effective strategies for its development. Given this, this research aims to investigate the experience of clinical psychologist supervisors’ in developing reflective skills in trainee clinical psychologists. Six themes have been derived by using thematic analysis and the findings are discussed along with implications and future research directions.

Introduction

Reflective practice

Reflection is regarded as a vital component for lifelong learning (Grant et al., Citation2006) and has been the subject of research for more than 150 years (Hargreaves & Page, Citation2013). John Dewey was among the first to conceptualise and introduce the concept of reflective thinking (Leigh, Citation2016). Dewey described reflective thinking as ‘active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends’ (Lagueux, Citation2014, p. 1).

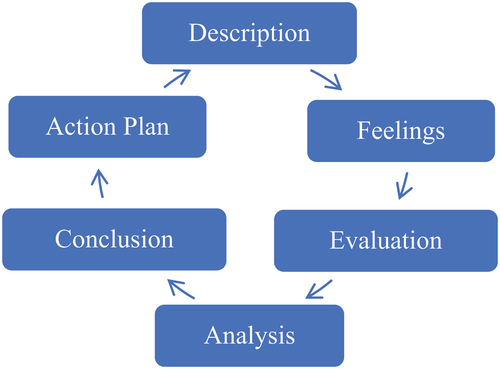

Donald Schön (Citation1983) introduced the concept of the ‘Reflective Practitioner’. In Schön’s view, reflective learning involves the exploration of experience, understanding its impact on oneself and others, and learning from this to inform future actions. Subsequently, Gibbs (Citation1988) developed the six stage Reflective Cycle model that has been used to make sense of a structured learning experience. The model offers a framework to examine recurrent experiences that fosters learning and planning from past experiences, as shown in .

Figure 1. Gibbs’ reflective cycle. Adapted from ‘The reflective practice guide: An interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection’ (Bassot, Citation2015).

Reflective practice and psychology

The use of reflective practice (RP) is necessitated by various professional bodies such as the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, Citation2014). The Psychology Board of Australia (PBA, Citation2015) included a requirement of an annual written reflection log in the guidelines for Continuing Professional Development for Psychologists seeking registration. Given its increasing importance, the British Psychological Society (BPS) included the concept of RP in their code of ethics and conduct from 2009. RP was regarded as an essential competency to prevent ethical or personal issues developing into serious concerns (British Psychological Society, Citation2009). Likewise, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) who regulate the profession of clinical psychology within the UK, also emphasised the use of reflection by registrant practitioner psychologists in their Standards of Proficiency guidelines (Health & Care Professions Council, Citation2015).

The BPS highlights the role of clinical psychologists: ‘as reflective scientist practitioners’ (p.8) in the Standards for the Accreditation of Doctoral Programmes in Clinical Psychology (British Psychological Society, Citation2017). One of the overarching goals and outcomes across the training programme for clinical psychology in the UK is ‘Clinical and research skills that demonstrate work with clients and systems based on a reflective scientist-practitioner model …’ (British Psychological Society, Citation2017, p. 15). Despite this, there is limited evidence of effective strategies for developing or learning RP. For instance, trainee clinical psychologists (TCPs) were unable to identify the strategies they used to assist in their reflection (Johnston & Milne, Citation2012). Furthermore, Curtis et al. (Citation2016) argued that clinical psychologists were not equipped with skills to apply reflection in clinical supervision despite receiving relatively intensive education and training in RP.

Supervision as a means to develop reflective practice

Supervision is mandated in professional practice, and notably in the training of clinical psychologists (British Psychological Society, Citation2017). To maintain practice standards and enhance professional development for psychologists, professional bodies and registration authorities stipulate minimum requirements for the hours of supervision before being eligible for independent practice (cited in O’Donovan et al., Citation2011). This has been supported by various international studies that supervision of clinical psychology practice ought to be a focus of training and professional accreditation (Gonsalvez & Calvert, Citation2014; O’Donovan et al., Citation2011). Milne (Citation2009) suggested that the ultimate goal for clinical supervision is to enhance and secure clients’ welfare that requires the: (1) provision of safe and ethical therapy, (2) development of competency and capability in the supervisee, and (3) development of long-term commitment to promote evidence-based practice.

Supervision models have been categorised into three major types: development models, psychotherapy models, and process-based models (cited in Gonsalvez et al., Citation2017). In the past two decades, competency-based models have emerged in the training of health-related professions and received attention from educators, supervisors, and practitioners (Gonsalvez & Calvert, Citation2014; Gonsalvez et al., Citation2017). The key features of competency models are centred around learning outcomes and evidence (Brown et al., Citation2005), and the scope of practice and disciplines (Gonsalvez & Calvert, Citation2014). As such, reflective skills are seen as fundamental for the development of competent professionals, with the ability to self-monitor their performance and continuously engage in learning throughout their professional career (see Embo et al., Citation2014).

Regular clinical supervision is seen to serve the function of encouraging RP and to ensure high quality and safe practice (Department of Health, Citation2004; Milne, Citation2009). Professional bodies such as the American Psychological Association (Citation2014), British Psychological Society (Citation2014), and Psychology Board of Australia (Citation2018) included RP as a core value in their guidelines for supervisory competency. Curtis et al. (Citation2016) argued that supervisory competence is derived from active and continuous reflection on knowledge, skills, and values/attitudes. To foster the use of RP during supervision, the British Psychological Society (Citation2017) states that ‘Reflective practice is also promoted through an effective use of supervision …’ (p. 9). Despite the regulatory interest in RP and supervision, research focusing on these areas remains scarce (Nguyen et al., Citation2014; O’Donovan et al., Citation2011; Truter & Fouché, Citation2015) especially in the field of clinical psychology (Fisher et al., Citation2015).

To effectively develop RP in TCPs, it is important to explore how this concept is understood and promoted by qualified clinical psychologists who supervise trainees. Some researchers (Davies, Citation2012; Priddis & Rogers, Citation2018) have argued that reflective supervision is the most common and useful method to cultivate the use of RP in healthcare professionals but the concept of RP was not adequately understood (Andersen et al., Citation2014; Nguyen et al., Citation2014) and there is still confusion around how to promote RP. Given the importance of developing reflective practitioners (British Psychological Society, Citation2017; Health & Care Professions Council, Citation2015), it is fundamental to understand how aspects of supervision can contribute to the development of RP competencies in TCPs.

Methodology

Research design

This qualitative research collected data using semi-structured interviews and analysed this data using a thematic analysis. Thematic analysis (TA) is a method used for identifying, analysing, and interpreting patterns within qualitative data sets (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017). TA was used to summarise the data content and interpret key features of the content guided by the research questions. A constructionist approach, which emphasises that reality is created in and through the research, was applied. The researcher does not look for or find evidence of psychological or social reality that sits behind people’s words but interprets how these words produce specific realities for the participants themselves within their context (Clarke et al., Citation2015). In the current research, TA was used to capture the experience of how clinical psychologists develop reflective competencies in TCPs across the group of participants rather than at an individual level.

Recruitment procedure and participants

Given that qualitative research can generate richer data, it tends to use relatively fewer participants than quantitative research. A recommended sample size for a small-to-medium qualitative study that involves interviews is between six and twenty (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). In the current study, 10 UK-based HCPC registered clinical psychologists were recruited through purposive sampling.

A senior member of a UK Doctoral Clinical Psychology Programme, who holds the contact details of HCPC registered clinical psychologist supervisors in the region, sent an email invitation on the Primary Investigator’s (PI) behalf to all programme supervisors. Participants who were interested in this research contacted the PI directly. Eligibility of potential participants was checked against the inclusion criteria and the characteristics of participants are summarised in Appendix 1.

Data collection

A semi-structured interview was used to collect data. A topic guide was constructed jointly by the PI and co-investigators, which consisted of questions relating to the participants’ current professional role, their conceptualisation of RP, their experience in applying RP in clinical settings, their experience in using RP during supervision, and what they found to be useful and/or difficult in promoting reflective skills in TCPs. Participants were encouraged to speak about the area of interest with limited prompting in order to enable the articulation of their experiential account. All interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed on completion.

Data analysis

The verbatim transcripts were analysed using a thematic analysis. The data analysis process was divided into six phases (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) which were iterative, so the researcher moves ‘forwards and backwards’ between phases to attain the best possible analysis (Howitt & Cramer, Citation2014). After initially identifying codes within the data they were categorised according to their similarities. The meaning of each code was carefully considered and similar codes placed together which led to the formation of subthemes. Patterns across subthemes led to the development of theme. At each stage, codes were reviewed to ensure the cohesion of the groupings and the relevance to research question. Subsequently, the name of respective themes and subthemes were assigned in accordance with the underlying, data driven patterns.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the commencement of the study, formal ethical approval was sought from the university and local research authority.

Results

From the analysis, six themes were developed as follows: (1) Interpersonal Aspects of Supervision, (2) Collaboration and Trainees’ Engagement, (3) Developmental Process of Reflective Practice, (4) Conscious Attempts to Promote Reflection, (5) Awareness of Potential Barriers to Reflection, and (6) Psychological Models and Reflective Practice. The themes and their respective subthemes were outlined in .

Table 1. The summary of themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: interpersonal aspects of supervision

The first theme outlined the relational properties of supervision that influenced the development and promotion of RP. The strategies used to create a trusting supervisory relationship and the use of self-disclosure were discussed.

Safe space and boundaries

Participants reported that providing an encouraging and respectful atmosphere in supervision was a key component to facilitate TCPs’ reflection. Some participants emphasised the importance of TCPs feeling safe and contained within supervision to enable them to truly speak their mind, including being able to decide whether to disclose certain information. Setting up a supervisory relationship with clear boundaries from the beginning of the placement was seen as a helpful way to promote reflection. Some participants suggested that maintaining a balance about asking the right question and not being too intrusive or overly enthusiastic reduced the risk of anxiety or unsafe feelings in TCPs.

… making sure that you’re doing it (developing self-awareness) enough that people are appropriately challenged, but not going so far that they get anxious and shut up and feel unsafe and don’t want to go any further …

Supervision boundaries also included supervisors making a clear distinction between clinical supervision and personal therapy. Mia, Nelson and Dorothy indicated that, at times, supervisors might not be able to support TCPs’ difficulties. When things went beyond supervisory containment, Dorothy would suggest TCPs address their personal issues in personal therapy.

… you only have to sort of think about, is this within a sort of normal range of therapeutic responses, or is it such a severe problem that you feel that unless they have some personal therapy themselves to address those past issues, they won’t really be able to be reflective in certain therapeutic situations …

Supervisors’ use of self

For some participants, curiosity was the foundation of any learning and helped improve the quality of therapy especially when TCPs felt ‘stuck’. Some participants noted that they consciously maintained this curiosity as a supervisor through the use of phrases such as ‘I wonder … ’ and noticing the language used within the supervision context. Humour was also seen as a way to make TCPs feel less guarded and be more reflective. Dorothy explained that a playful space is also a creative space where TCPs feel safe to explore things.

There’s more laughter um there’s more in jokes so the things that are problems become kind of in jokes and they become ok to be talked about …

The directiveness of the supervisor can also shape the use of RP in TCPs. More than half of the participants noticed that TCPs with limited clinical experience were more reliant on supervisors’ directives and guidance. Although it is easy to slip into a directive mode during supervision, Mia, Don, and Lily reminded themselves not to be too directive. For Lily, a non-directive approach was better at helping to develop the internal supervisor (Bell et al., Citation2017), and enhance TCPs’ confidence.

I think you’re owning it a bit more if you’re directing somebody to reflect, and you’re saying you know how was that, what do you think you did well, what do you think you might change, you know you’re helping them to think and weigh up and giving them some confidence in their own decision-making ability, it helps them develop their own internal supervisor.

In addition, Nelson believed that an appropriate level of self-disclosure helped to build trust in a supervisory relationship. Celine and Lily reported that sharing similar experiences often facilitated self-reflection as trainees would learn that supervisors went through the same things.

Sometimes it’s reassuring to, as a supervisor, for your supervisor to be saying “Yes, I’ve been there I know what that’s like”.

Theme 2: collaboration and trainees’ engagement

This theme captured participants’ attempts to cultivate a collaborative supervisory atmosphere to enable trainees engaging in the process of RP. The fear of being judged and the broader assessment context that contributed to TCPs’ engagement in RP is also discussed.

Working together

All 10 participants advocated collaborative reflection within supervision. For instance, they would go through issues together with TCPs, reflecting on matters that get in the way, discuss and formulate cases together, and give feedback and prompt for reflection following observation sessions. Six participants considered that mutual observation or joint sessions enabled the development of RP. Tina, Karina, and Dorothy suggested that modelling self-reflection following a joint session would encourage reflection in TCPs.

… it’s partly showing to the trainee that you’re not the one with all the answers, that you need to reflect on what you’re doing … and they watch you freeze or struggle with something or get something wrong, and then you can then reflect on it afterwards.

Performance-driven evaluative context

Some participants reported that TCPs often want to do or say the ‘right’ thing. For Jacob, a trainee’s reflective ability can be influenced by their perception of their performance and they often try to say what they think the supervisor wants to hear. This approach can become an inhibitor for TCPs to reflect or learn. To counteract this performance-driven attitude, majority of participants suggested a normalising approach, including normalising imperfection and encouraging learning from mistakes and successes to promote that there is no right or wrong way to feel or to reflect. Tina reported that:

I suppose you know you would say there’s not a right or wrong way to feel … I think the barrier might be that they think well you know, if I say “I saw this patient and they made me feel you know really angry or really sad” that I (as a supervisor) can’t hear that …

For some participants, the supervisors’ dual coaching and assessor roles could suppress the use of reflection in supervision. To address this, Dorothy proposed that developing trust and ensuring confidentiality so that TCPs feel safe to share or reflect within the evaluative context.

“I have to be caring” vs “I can’t be that good”

Jacob and Dorothy asserted that most trainees find it tough to admit that it is difficult to be reflective. Dorothy noticed in general that TCPs have difficulties in expressing negative feelings towards their clients.

… you’d want trainees to be able to talk very openly about feelings, negative feelings towards clients which they often find very difficult to express because they’re in a caring profession, and they’re a trainee, and they think they should be warm towards everyone.

About half of the participants reported that trainees often found it difficult to receive praise and positive feedback. For Celine, this was not only limited to TCPs, but psychologists in general, who are not good in recognising their own strengths and therefore she explicitly discusses things that are going well during supervision. Don felt that struggling to recognise one’s own strengths may be associated with the lack of reflection.

… I think if someone is feeling really uncomfortable and struggling to identify their strengths, then I would kind of wonder whether that’s actually primarily due to a lack of reflection, rather than a fundamental lack of strengths …

Theme 3: the developmental process of reflective practice

This theme described the development of RP, from initial exploration and learning about the concept of reflection to the active application of self-reflection in clinical setting.

Levels of reflective practice and experience

For some participants, TCPs come with different levels of reflective ability. They had often already engaged in self-reflection and were able to bring RP into supervision.

I’d be really surprised if somebody turned up at placement and had no concept of reflecting on their internal world or their practice. I’d be very worried about that if that happened, … it hasn’t really.

(Mia)

Four participants felt that some trainees were naturally more reflective than others. Lily, Tina, and Liam also found that some TCPs require some encouragement and inspiration to develop and enhance their reflective skills.

Some trainees they do it (reflect) very well, for some it doesn’t come as naturally and they need to be helped to work with it more …

The majority of the participants felt that TCPs that had clinical experience prior to training, or were in the latter stage of their training were generally more reflective. However, Nelson, Dorothy, and Liam expressed different views on this. For them, stages of training were not related to the ability to reflect as not every trainee develops as a reflective practitioner over the course of training. Nelson believed that some TCP’s are not ready for that level of curiosity and they would be more reflective when they feel more ready.

… they’ll kind of return to it (reflection) at a later date and I think that’s probably a positive reflection on that, but I think it also demonstrates that sometimes people aren’t ready for that level of curiosity or intrusion.

Demonstration of reflective practice

Most of the participants felt they could identify the development of RP through the behaviour of TCPs. Trainees were seen to be more reflective when they asked more reflective questions that were unprompted. The progress in RP can also be noticed when trainees feel more comfortable to take risks and go beyond their comfort zone. Participants also observed that TCPs became more reflective when they focused more on the contexts beyond the clinical work, modelled RP with other healthcare professionals, and became more active, relaxed and playful within supervision.

I suppose you might then see them modelling it with the wider team, kind of asking people to consider what they think might have been going on in that particular incident, or encouraging non-psychologists to think more psychologically …

However, it was noted that none of the participants used any formal tool to measure RP.

Theme 4: conscious attempts to promote reflection

The fourth theme depicted the active effort of participants using a number of strategies to foster self-reflection during supervision. This theme also captured participants’ perception of the use of psychological frameworks in promoting RP.

Consciously promoting reflective practice

Most participants took opportunities to enhance reflective skills within and outside supervision. This could be facilitated by the supervisor through the use of recordings, modelling and role-plays, guided discovery, and genograms. This often requires the participant to spontaneously model or demonstrate the use of reflection in front of TCPs.

… trainees tend to be in the room with us, so me and my colleague would maybe talk, would reflect on a case … I think to model well hopefully what’s good RP in front of trainees so that they realise that this is something that they can talk about as well …

Other strategies such as directed reading and keeping a reflective journal were more reliant on trainees’ tenacity in implementation, despite active involvement and encouragement by participants. However, some participants had a strong preference for a particular strategy over others.

… in the context of supervision, I will try and ask questions that promote reflection, I will try and provide reading materials around particular issues … I don’t tend to use role-play very much, I don’t try and get people to keep a reflective journal, that maybe my personal prejudice but also found that when I had a reflective journal what really happened was I tried to fill it in just before I had to discuss it with someone …

Using models to make sense of reflective practice

Eight participants believed that using a psychological model helped provide some structure to the way people reflect. Some participants advocated an eclectic approach and used elements of different models to inform RP. Others focused more on psychodynamic (see Deal, Citation2007), systemic (see Stratton & Lask, Citation2013), and cognitive analytical (see Denman, Citation2001) approaches given their relational components. For instance, Tina believed that a psychodynamic approach encouraged a deeper level of reflection.

I think (the) psychodynamic (approach) is very reflective because I guess it works just on the transference and counter-transference, and I suppose maybe it’s a stereotype, but I think CBT is maybe a bit less reflective.

Although cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT, see Keegan & Holas, Citation2009) was generally viewed as being too structural by some participants, Tina and Liam believed that RP does exist in the model but reflection is more on techniques.

I would recognise that RP would exist in CBT … RP might be on how we are using it at all, or why it’s not worked and someone’s not done their homework, um but I wouldn’t see it as entrenched in the model …

Some participants preferred to use a more generic reflective model such as Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, Gibbs’ reflective cycle, or Schön’s reflection in/on action, to promote self-reflection. Based on Karina’s experience, TCPs usually respond well to a reflective model if the supervisor can make it directly relevant and useful to them.

Theme 5: awareness of potential barriers to reflection

This theme described potential obstacles to reflection. Some participants identified that time restrictions and stress levels were two significant barriers to reflection and as such provided more time for reflection during supervision. Mia and Dorothy felt that a lack of intellectual curiosity and insight may also be a block to reflection.

I suppose you could see that as part of reflective or certainly it’s not even a problem with empathy but it’s a problem with you don’t know what you don’t know … If you see what I mean a sort of lack of intellectual curiosity was a bit of a concern.

Most of the participants found that TCPs became less reflective when they focused more on technical aspects of clinical work.

It is good to, you know to try new ways of working and to do things well … but I suppose recognising what can be lost sometimes with being so fixed on that you might you might miss useful information …

The majority of the participants thought it was important to be mindful about the way clinical work could resonate with TCPs’ personal life experiences. Previous challenging experiences of trainees could potentially interfere with their professional role and ability to reflect. Defensiveness, rigidity, and anxiety were often seen as traits that limited reflection in TCPs.

… all the people that I’ve supervised who felt very unresponsive um to supervision have quite common personality characters … people have very negative experiences they can be quite shut down to reflection you know because they feel that if they’ve been very pathologised…

Discussion

The data obtained in this study demonstrated the importance of RP within the supervisory experience. To most of the participants, reflection was a vital element across the breadth of clinical psychologists’ work and was viewed as a core competency in maintaining high professional standards and promoting experiential learning. In line with the findings, a recent study (Carmichael et al., Citation2020) suggested that RP plays an important role in clinical psychologists’ ability to maintain an open and curious clinical perspective. The present findings concurs with the widespread recognition of the importance of developing RP in healthcare professionals (Davies, Citation2012).

Interpersonal aspects of supervision are seen as helpful and significant in promoting RP. Some researchers (Hobbs, Citation2007; Naghdipour & Emeagwali, Citation2013) have also highlighted the importance of creating a proper and conducive learning environment to enhance the engagement of reflection. Currently, there is limited research focused on how to create a safe and trusting atmosphere, which help foster the development of RP. This study outlined some ways to provide a safe space for reflection: setting appropriate boundaries, maintaining an appropriate level of self-disclosure and directiveness, maintaining a curious stance as a supervisor, and using humour during supervision.

One finding from the current study less articulated in the literature was that a performance-driven attitude by TCP’s impacts on their ability to develop RP skills. The results suggested that TCPs demonstrated a need to get things right during their placement experience and this is likely associated with the evaluative context. Hobbs (Citation2007) believed that RP should not be assessed in the early stages of learning as the feeling of being assessed suppresses TCPs’ openness during supervision. TCPs should be provided opportunities to reflect and learn in a non-threatening way. For instance, some supervisors took the pressure off trainees’ by modelling being imperfect and not knowing the answers all the time. Further research investigating the performance-driven attitude from TCPs’ perspective would be useful when thinking about how to develop RP competencies with respect to clinical psychology training.

The findings from the study demonstrate that clinical psychology supervisors make conscious attempts to foster reflection in TCPs. There were a variety of different preferences for the promotion of RP, such as the use of recordings, genogram, modelling and role-play, guided discovery, directed reading, and reflective journal. However, TCPs’ preferences in terms of methods used to develop RP was not reported by participants and could be an area of focus for future research. It seems likely that taking trainees’ preferences into consideration when fostering RP would enhance their development and would likely have useful implications for training courses and placement providers. This was supported by O’Reilly and Milner (Citation2015) who argued that students at different stages of development prefer to use distinct RP methods.

Supervisors regarded the use of reflective frameworks as very useful in providing a further understanding of the concept of RP. With the help of the generic reflective models such as Kolb’s, Gibbs’, and Schön’s reflection models, the implementation of acquired knowledge into practice was made easier. Regardless of supervisors’ psychological stance or their preference towards particular supervision models, it is crucial to identify core components of reflective supervision (such as qualities and behaviours of a supervisor, as well as structure and process of reflective supervision) and incorporate them in education programmes or professional trainings across disciplines (Tomlin et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, there was a lack of any consensus about which models to use and this reflects the lack of agreed consensus regarding the concept of RP (Lowe et al., Citation2007; Smite & Trede, Citation2013). This lack of a clear conceptualisation of RP also impacts on attempts to measure RP and another notable finding was that despite measurement tools being available (Ooi et al., Citation2020) no supervisors described any formal psychometric measure of RP.

Another finding was that TCPs’ ability to reflect could be further developed throughout their professional training and this was aligned with Neville’s (Citation2018) and Tricio et al. (Citation2015) studies. Nonetheless, a small number of participants believed that the stage of training was not directly related to the level of engagement in RP and that some TCPs continued to struggle in RP in their final year of training. Despite the differing opinions and initial reflective ability, it would be beneficial if supervisors track the development of RP and tailor the promotion of reflective skills according to the comfort level of trainees’ engagement. This could be done by exploring level of reflection using standardised assessment tools during supervision, such as the Reflective Questionnaire and the Self-Reflection and Insight Scale (Ooi et al., Citation2020).

The study identified factors that inhibit self-reflection: time restriction, increased stress levels, lack of insight, and being too focused on technical aspects of clinical work. Previous research has highlighted similar factors that inhibit self-reflection. These include a lack of awareness and motivation, lack of metacognitive skills such as self-monitoring and self-evaluating (Renner et al., Citation2014), stress, teaching quality (Pai, Citation2015), time, and lack of understanding of the reflective process (Davies, Citation2012). To tackle these barriers, ensuring more time for reflective activities to be allocated during supervision, and being appropriately curious as a supervisor could help early identification of problem areas. Joint reflection between supervisor or other healthcare professionals and TCPs incorporating modelling and self-disclosure could be considered to further cultivate the reflective ethos. Hobbs (Citation2007) suggested that people may respond and reflect more positively if they were given the autonomy to decide on the format or strategy use for RP. Different psychological and reflective models were reported to be useful to inform RP.

Conclusion

A safe and conducive atmosphere is very important in helping to foster RP within supervision as is early identification of potential barriers. Performance-driven behaviours can be addressed by using commonly employed strategies, including active modelling and self-disclosure. Although there were conscious attempts to promote the use of RP in TCPs, there was a wide diversity in terms of how to develop RP. In addition, the lack of agreed consensus about the concept further complicates how supervisors and TCPs engage in RP. Research attempting to develop a consensus of terms regarding RP across clinical psychologists as well as to identify core components for reflective supervision would be a useful focus for future research.

Limitations

The self-selected, purposive sampling method of recruitment is a limitation of the current study. Given the inclusion criteria, the participants included in the study value and are currently using RP in a clinical setting. Accordingly, the range of views on the central importance and value of RP amongst clinical psychologists’ was constrained by the sample recruited. In addition, the definition of the concept of RP was not a focus in this research. Given that the way clinical psychologists understand RP may impact on how they try to foster these skills in TCPs, a clearer focus on the definition and measurement of RP would have been helpful.

Supplemental Material

Download (13.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2023.2210069.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Su Min Ooi

Dr Su Min Ooi is a clinical psychologist who has more than 10 years of clinical experience in healthcare settings. She has developed interests around clinical supervision and reflective practice when she underwent her doctorate training at University of East Anglia (UEA) and continue to involve in the development of reflective group and reflective training for staff at her work place.

Siân Coker

Professor Siân Coker is the Director of the Clinical Psychology Doctorate Programme at UEA. Her research interests include perfectionism and its’ role in the management of a number of health conditions. She is also a research enthusiast who has significantly contributed in the teaching of research methods, ethical practice, and ethics in research on the doctoral programme in Clinical Psychology.

Paul Fisher

Dr Paul Fisher is a Clinical Psychologist, Clinical Associate Professor and the Programme Director of the Clinical Associates in Psychology training at UEA. His teaching and research interests include professional practice issues for clinical psychologists such as formulation and reflective practice. He has expertise in the use of qualitative research methods, and this often informs his research.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Guidelines for Clinical Supervision in Health Service Psychology. http://apa.org/about/policy/guidelines-supervision.pdf

- Andersen, N. B., O’Neill, L., Gormsen, L. K., Hvidberg, L., & Morcke, A. M. (2014). A validation study of the psychometric properties of the Groningen reflection ability scale. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-214

- Bassot, B. (2015). The reflective practice guide: An interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection. Routledge.

- Bell, T., Dixon, A., & Kolts, R. (2017). Developing a compassionate internal supervisor: Compassion-focused therapy for trainee therapist. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(3), 632–648. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2031

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE Publications.

- British Psychological Society. (2009). Code of ethics and conduct. Guidance published by the ethics committee of the British Psychological Society. Retrieved April , 2017, from https://beta.bps.org.uk/sites/beta.bps.org.uk/files/Policy%20-%20Files/Code%20of%20Ethics%20and%20Conduct%20%282009%29.pdf

- British Psychological Society. (2014). DCP policy on supervision. Retrieved May , 2017, from http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Publicfiles/inf224_dcp_supervision.pdf

- British Psychological Society. (2017). Standards for the accreditation of doctoral programmes in clinical psychology. Retrieved January , 2019, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/clinical-psychology-doctorate/sites/clinical-psychology-doctorate/files/Appendix4r2010.pdf

- Brown, K., Fenge, L. A., & Young, N. (2005). Researching reflective practice: An example from post-qualifying social work education. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 10(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596740500200212

- Carmichael, K., Rushworth, I., & Fisher, P. (2020). ‘You’re opening yourself up to new and different ideas’: Clinical psychologists’ understandings and experiences of using reflective practice in clinical work: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Reflective Practice, 21(4), 520–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1775569

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In J. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 222–248). SAGE Publications.

- Curtis, D. F., Elkins, S. R., Duran, P., & Venta, A. C. (2016). Promoting a climate of reflective practice and clinician self-efficacy in vertical supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 10(3), 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000121

- Davies, S. (2012). Embracing reflective practice. Education for Primary Care, 23(1), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2012.11494064

- Deal, K. H. (2007). Psychodynamic theory. Advances in Social Work, 8(1), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.18060/140

- Denman, C. (2001). Cognitive–analytic therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7(4), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.7.4.243

- Department of Health. (2004). Organising and delivering psychological therapies. Retrieved May, 2017, from http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20040823180324/dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4086097.pdf

- Embo, M. P. C., Driessen, E., Valcke, M., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2014). Scaffolding reflective learning in clinical practice: A comparison of two types of reflective activities. Medical Teacher, 36(7), 602–607. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.899686

- Fisher, P., Chew, K., & Leow, Y. J. (2015). Clinical psychologists’ use of reflection and reflective practice within clinical work. Reflective Practice, 16(6), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2015.1095724

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Furhter Education Unit, Oxford University.

- Gonsalvez, C. J., & Calvert, F. L. (2014). Competency-based models of supervision: Principles and applications, promises and challenges. Australian Psychologist, 49(4), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12055

- Gonsalvez, C. J., Hamid, G., Savage, N. M., & Livni, D. (2017). The supervision evaluation and supervisory competence scale: Psychometric validation. Australian Psychologist, 52(2), 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12269

- Grant, A., Kinnersley, P., Metcalf, E., Pill, R., & Houston, H. (2006). Students’ views of reflective learning techniques: An efficacy study at a UK medical school. Medical Education, 40(4), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02415.x

- Hargreaves, J., & Page, L. (2013). Reflective practice. John Wiley & Sons.

- Health & Care Professions Council. (2015). Practitioner psychologists. Standard of proficiency: Practitioner psychologists. Retrieved June, 2017, from https://www.hcpc-uk.org/globalassets/resources/standards/standards-of-proficiency—practitioner-psychologists.pdf

- Hobbs, V. (2007). Faking it or hating it: Can reflective practice be forced? Reflective Practice, 8(3), 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940701425063

- Howitt, D., & Cramer, D. (2014). Research methods in psychology (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Johnston, L. H., & Milne, D. L. (2012). How do supervisee’s learn during supervision? A grounded theory study of the perceived developmental process. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 5(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X12000013

- Keegan, E., & Holas, P. (2009). Cognitive-behavior therapy: Theory and practice. In R. Carlstedt (Ed.), Integrative clinical psychology, psychiatry and behavioral medicine (pp. 605–630). Springer Publications.

- Lagueux, R. C. (2014). A spurious John Dewey quotation on reflection. https://www.academia.edu/17358587/A_Spurious_John_Dewey_Quotation_on_Reflection

- Leigh, J. (2016). An embodied perspective on judgements of written reflective practice for professional development in higher education. Reflective Practice, 17(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2015.1123688

- Lowe, M., Rappolt, S., Jaglal, S., & Macdonald, G. (2007). The role of reflection in implementing learning from continuing education into practice. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 27(3), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.117

- Milne, D. (2009). Evidence-based clinical supervision. Principles and practice. BPS Blackwell.

- Naghdipour, B., & Emeagwali, O. L. (2013). Assessing the level of reflective thinking in ELT students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 83, 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.052

- Neville, P. (2018). Introducing dental students to reflective practice: A dental educator’s reflection. Reflective Practice, 19(2), 278–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1437400

- Nguyen, Q. D., Fernandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48(12), 1176–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12583

- O’Donovan, A., Halford, W. K., & Walters, B. (2011). Towards best practice supervision of clinical psychology trainees. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00033.x

- Ooi, S. M., Fisher, P., & Coker, S. (2020). A systematic review of reflective practice questionnaires and scales for healthcare professionals: A narrative synthesis. Reflective Practice, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1801406

- O’Reilly, S. L., & Milner, J. (2015). Transitions in reflective practice: Exploring student development and preferred methods of engagement. Nutrition & Dietetics, 72(2), 150–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12134

- Pai, H. C. (2015). The effect of a self-reflection and insight program on the nursing competence of nursing students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(5), 424–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2015.03.003

- Priddis, L., & Rogers, S. L. (2018). Development of the reflective practice questionnaire: Preliminary findings. Reflective Practice, 19(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1379384

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2015). Registration standard: Continuing professional development. Retrieved December , 2018, from https://www.psychologyboard.gov.au/Standards-and-Guidelines/Registration-Standards.aspx

- Psychology Board of Australia. (2018). Guidelines for supervisor training providers. Retrieved November , 2018, from https://www.psychologyboard.gov.au/news/2018-06-08-revised-guidelines-for-supervisors-and-supervisor-training-providers-published-today.aspx

- Renner, B., Kimmerle, J., Cavael, D., Ziegler, V., Reinmann, L., & Cress, U. (2014). Web-based apps for reflection: A longitudinal study with hospital staff. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3040

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

- Smite, M., & Trede, F. (2013). Reflective practice in the transition phase from university student to novice graduate: Implications for teaching reflective practice. Higher Education Research and Development, 32(4), 632–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.709226

- Stratton, P., & Lask, J. (2013). The development of systemic family therapy for changing times in the United Kingdom. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9252-8

- Tomlin, A. M., Weatherston, D. J., & Pavkov, T. (2014). Critical component of reflective supervision: Responses from expert supervisors in the field. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21420

- Tricio, J., Woolford, M., & Escudier, M. (2015). Dental students’ reflective habits: Is there a relation with their academic achievements? European Journal of Dental Education, 19(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12111

- Truter, E., & Fouché, A. (2015). Reflective supervision: Guidelines for promoting resilience amongst designated social workers. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 51(2), 444. https://doi.org/10.15270/51-2-444