ABSTRACT

Nursing education has made a journey from being mainly clinic-based education to being education that is carried out at universities and university colleges. The journey from being clinical education to being a university education has likewise created a gap between theory and practice. In this article, the aim is to describe the learning model of Developing and Learning Care Units (DLCU), based on caring science didactics with a lifeworld approach. To overcome the gap between theory and practice, students are supported by a reflective supervisory approach, to learn to take care of patients. Caring and learning are based on caring science with a lifeworld perspective to ensure caring and learning based on a holistic perspective that includes the individual patient and student.

Introduction

The aim of this article is to describe the Swedish learning model of Developing and Learning Care Units (DLCU), based on caring science didactics with a lifeworld-led approach. DLCU is one of the multiple learning models/structures for nursing students learning in clinical practice, other learning model based on caring science is described by Kolderstam et al. (Citation2021) and Eskilsson et al. (Citation2015) and Andersson et al. (Citation2020), describing reflection as a core element in learning. However, unique to these learning models is that caring, and learning is based on a caring science perspective. The aim of this perspective is to support students in learning to integrate theoretical and practical knowledge in clinical practice based on structural learning activities (Andersson et al., Citation2020; Eskilsson et al. (Citation2015); Hörberg et al. (Citation2011); Hörberg et al. (Citation2019); Hörberg et al. (Citation2014); Kolderstam et al. (Citation2021). Apart from the above mentioned learning models, DLCU adds learning in pairs to the caring science perspective. Furthermore, learning in pairs is similar to peer learning (Stenberg & Carlson, Citation2015) apart from didactics based on caring science perspective with a lifeworld-led approach. Core elements of DLCU include caring science with a lifeworld approach guiding the caring and learning approach, reflection intertwining theoretical and practical learning, learning in pairs, and supervision in groups of students based on patients’ narratives (Ekebergh, Citation2007, Citation2009; Hörberg et al., Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2019).

From the beginning, nursing education in Sweden has progressed from being mainly carried out in clinics to being carried out at universities and university colleges (Pilhammar, Citation1999). Difficulties in collaboration between clinics and universities have affected the opportunities in establishing and developing effective learning environments in clinical practice. The journey from clinic-based education to university education has likewise created a gap between theory and practice (Edgecombe et al., Citation2014). To encourage a professional way of caring, theoretical knowledge is important and necessary to be able to care for the patients based on compassion and craftmanship (Adamson, Citation2018), but students experience difficulties in applying their theoretical knowledge when caring for patients (Severinsson, Citation1998). Nursing students’ education in clinical practice is supposed to be based on learning activities that involve developments in compassionate care based on patients’ stories and experiences (Adamson & Dewar, Citation2015; Rosser et al., Citation2019). Likewise, Kolderstam et al. (Citation2021) describe the importance of using reflection to support students in learning to care for their patients.

Holst and Hörberg (Citation2012, Citation2013) describe that nursing students’ learning in pairs supports students’ ability to use reflection in learning to care for the patient, since they share learning experiences with each other. Learning in peers is also a positive way for students to support each other in developing their roles as professional careers (Aston & Molassiotis, Citation2003; Edgecombe & Bowden, Citation2009; Stenberg & Carlson, Citation2015; Vuckovic & Landgren, Citation2020). The possibility of learning together in peers is shown to reduce nervousness and to give a feeling of security since they can ask someone who understands their situation as a beginner (Stenberg & Carlson, Citation2015). Pålsson et al. (Citation2017) also describe students’ learning in pairs as developing an independence in caring for the patient, compared to students learning on their own.

Supervisory support also plays a pivotal role in students’ ability to bridge the gap between theory and practice by using reflection as a guiding star (Holst, et al., Citation2017a). Patients being cared for by students that have a good cooperation with their supervisors also consider themselves to be included in a professional interaction (Andersson et al., Citation2020; Eskilsson et al., Citation2015; Strömwall et al., Citation2018). This is in line with Cant et al. (Citation2021), who describe the importance of the supervisory relationship, pedagogical atmosphere, the premises of nursing, and ward leadership as important factors in creating a learning atmosphere.

Nurturing collaboration between clinics and universities to overcome the gap between theory and practice has contributed to the development of structural learning environments around the world, aimed at supporting nursing students in bridging the gap between theory and practice. Clinicians and academics have developed structural learning environments together, built on a strong collaboration, knowledge in different areas, trust, respect, and open communication (Edgecombe et al., Citation2014; Hendersen et al., Citation2011). The purpose of structural learning environments is to create a learning environment that support students in developing their ability to be active in their own education and to enable learning to care for patients in a caring environment, incorporated into a more authentic learning environment such as on clinical placement (Masters, Citation2016). To remedy these problems, bridging the gap between theory and practice, and creating an effective and developing structural learning environment, Developing and Learning Care Unit(s), (DLCU) was developed. The didactic approaches of DLCU are founded on caring science with a lifeworld perspective (Hörberg et al., Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2019). Caring science describes how to support patients to strengthen their process of health, and as a healthcare professional to adopt an open attitude towards the patient´s lifeworld (Dahlberg, Citation2011). Supporting students’ education rooted in a lifeworld perspective means adopting a reflective approach guided by openness and sensitivity toward individual students’ learning. In the same way as the students are supported by their supervisors based on a lifeworld-led approach, students learn to care for patients based on a lifeworld-led approach (Ekebergh & Lindberg, Citation2020). The DLCU is described in further detail below under the headings: a lifeworld-led perspective, caring and learning from a lifeworld-led perspective, supervising team at DLCU, reflective approach based on a lifeworld-led approach at DLCU, learning in pairs at DLCU, and group supervision for the students participating in DLCU.

A lifeworld-led perspective

The lifeworld is described by Husserl (Citation1936/1970 as the world of where human beings exist, and that all humans have a unique lifeworld. This means that all humans experience the world from their own point of view (Husserl, Citation1936/1970). The lifeworld is based on each individual but is also a social world that is shared with other human beings. Therefore, we can share each other’s lifeworlds while at the same time not fully understanding each other’s lifeworlds. Husserl (Citation1929/1992) describes the lifeworld as ‘taken for granted’ and that we have a ‘natural attitude’ toward our own experiences. Having a natural attitude to the world means that there is no conscious reflection on what is experienced. To fully understand lifeworld theory, we also need to understand Husserl (Citation1929/1992) theory of intentionality. This theory describes the direction of consciousness is directed outwards from ourselves. Central is that we always experience things as something, which is described as an intentional act that creates meaning; there is always a meaning in the relationship between subject and object. Intentional experiences are the same as experiences of consciousness, where ‘intentional’ means to be aware of something. Every situation experienced thus creates meaning for man. In the everyday attitude, we have a natural attitude to what is experienced; this connotes an unreflective attitude where what we experience is taken for granted. There is no distance to the lifeworld, which can be described as a naïve attitude to what is experienced. When we become aware of this and how we experience something as something, we can gain distance from ourselves and thus be able to approach a reflexive attitude. In a reflexive attitude, experiences make sense to us, because they are put in relation to our lifeworld and what we have previously experienced. Merleau-Ponty (Citation1945/2002 has further developed Husserl’s lifeworld theory by describing the living body. The living body is the centre of the world, and it is through the lifeworld that we gain access to the world by giving us the opportunity to experience the world. It is at the same time the body that limits our access to the world, in the case of illness. The lived body is a subject – object, where body and soul are a unit, which can neither be separated from each other nor from the world. Seeing the lived body as a subject – object means that objective knowledge cannot be fully understood without the subjective experience. This means that the lived body includes the physical, mental, existential, and spiritual at the same time.

Caring and learning from a lifeworld-led perspective

The patient is understood as a subject and a lived body with memories of earlier experiences, which means that the patient is searching for meanings which contributes to understand them as a lived body. The lived body is physical, psychical, existential, and spiritual at the same time (Merleau-Ponty Citation1945/2002), which means that the patient is understood from a holistic perspective (Ekebergh, Citation2009). To see and understand the patient from a holistic perspective based on the lifeworld perspective enables a caring relationship between the carer and the patient with a joint effort to alleviate suffering and to strengthen the patient’s health (Dahlberg, Citation2011). The patient is understood as an expert on him/herself and their experiences of health/unhealth. Caring actions from a lifeworld perspective are based on understanding the patient as a subject and lived body with memories of earlier experiences. Ekebergh (Citation2009) states that all learning is based on a lifeworld perspective, therefore didactics should also be based on the lifeworld perspective. Didactics with a lifeworld perspective aim to, through supervision, enable education for each individual student, based on the student’s understanding, knowledge, and experiences (Dahlberg & Ekebergh, Citation2008; Ekebergh, Citation2009, Citation2011). The supervisory approach is characterized by responsiveness to the individual student’s education through an open, flexible, and responsive approach (Ekebergh, Citation2005). At the same time as the students are being supported from a lifeworld perspective, patients are cared for by students from a lifeworld perspective (Dahlberg & Ekebergh, Citation2008). The nursing student complements the patient as an expert through their knowledge about health and suffering in general. The patient is the focus of the caring acts that are provided, and the aim is to support the patient’s wellbeing and health to help the patient to accomplish their life projects. To see and to understand the patient from a holistic perspective based on the lifeworld create possibilities to build a good caring relationship between the nursing student and the patient (Dahlberg & Ekebergh, Citation2008; Ekebergh, Citation2011). From a lifeworld perspective, learning cannot be separated from life, which also applies to learning to care. This means that a practical knowledge in caring and theoretical knowledge in caring science are intertwined based on the students´ lifeworld (Hörberg, Ozolins, Ekebergh, Citation2011).

Supervising team at DLCU

Students are supported by a supervision team that consists of one base supervisor (nurse at students’ clinical practice), one head supervisor (nurse at students’ clinical practice) and one lecturer (an academic educator from the nursing education). The base supervisor supervises students in the bedside area, and students can have multiple base supervisors. The head supervisor represents continuity and is responsible for a practical caring science perspective, for planning and assessing students’ progress, and supporting students’ education in group supervision. The lecturer is responsible for the theoretical caring science perspective, assessing students’ education together with the head supervisor, and supporting students’ education via group supervision. The supervisory approach is characterized by a reflexive approach based on supporting students’ learning in pairs as a learning unit at the same time as they strive towards supporting the individual student’s education. Supervisors support students by asking reflective questions designed to interlace with the student’s theoretical knowledge in the practical encounter with the patient. The reflective approach refers to creating prerequisites for students to learn through their own experiences and to develop knowledge about caring (Ekebergh, Citation2009, Citation2011).

Reflective approach based on a lifeworld-led approach at DLCU

The essence of DLCU is supporting caring and learning based on a reflexive supervisory approach, and to support development of students’ reflexive approach to caring encounters with patients. Reflection from a lifeworld perspective, in this context, from students’ experiences and knowledge, focus on intertwining the student’s lifeworld, the patient’s lifeworld and a caring science perspective. Personal experiences meet with lived and concrete knowledge as well as with scientific knowledge. To create a link between theory and practice supervisors communication with the students must touch their minds. Reflection could be understood as tied to the subject and as something more than just a cognitive action. Reflection enables the subject (in this case the student) to be aware of and articulate their lived experiences, which means that the learning process starts with reflection. To support nursing students in learning to reflect and to link theory and practice is based on the understanding that theory and practice creates a holistic view of caring actions (Ekebergh, Citation2007). Reflection is carried out in an open, flexible, and sensitive way in relation to the students (Ekebergh, Citation2007). The reflection is something more than just a discussion and is supposed to support the students in experiencing their professional caring approach and increasing awareness in their caring approach. Reflection must touch, engage, and create meaning for the caregiver/student; therefore, the reflection starts in the students encounter with the patients. Furthermore, theoretical knowledge can be incorporated in practical caring actions through reflection based on the students encounters with the patients (Ekebergh et al., Citation2018; Ekebergh, Citation2011). Reflection with a lifeworld perspective supports students in becoming aware of their own values, norms, and perspectives on life, which could be crucial for how students meet the patient´s world (Ekebergh, Citation2011). To enable a deeper understanding of students’ experiences in clinical practice, experiences need to be reflected against a theory (in this case, the theory of the lifeworld) that can provide nuances and variation of meaning to the lived caring situation.

Reflection is used in everyday caring and learning at a DLCU to support students learning; for example, in the end of the day together with the head- or base supervisor, during supervision in group (explained in a separate heading), and when the students are caring for patients. In relation to when students are caring for patients, supervisors ask questions before and after student encounters with patients (for example, when taking a blood test, providing medication, or taking vital parameters), to raise awareness and support students’ learning. Questions that could be asked by the supervisor of the students before an encounter with a patient include what are you planning to do? Why are you planning to do like that? Questions that could be asked by the supervisor after the students’ encounter with a patient, what happened and what did you do? How did you feel? What have you learned? The everyday reflection before and after encounters with a patient is also supported by reflection in group once a week. The supervisor sits down in a private room with a group of students to reflect over their experiences during the last week. Questions that the supervisors could ask of the students are, what situations have especially touched you? What have you learned? How do we support your learning in the future?

Learning in pairs at DLCU

DLCU are developed at selected caring units at general hospital, psychiatric care units, and municipal care units. The purpose of the DLCU and learning in pairs is to support learning between students during patient encounters. Depending on where students are conducting their clinical practice, learning in pairs has different layouts. In general, hospital students are learning in pairs of one student from second year and one student from third year (nursing education in Sweden consists of three years in total). In psychiatric care, students learn in pairs of two students from the second year. In municipal care, students learn in pairs of three students; two students from the first year supported by one student from the third year. The students have goals and assessments to fulfill based on the year they are studying. Students are randomly sorted into pairs and are introduced to each other the first day of clinical practice by their head supervisor and teacher. The more senior student is responsible for the role of supervising the more junior student. At the beginning of students’ clinical practice, students are caring and learning for one patient together within the pair; this starts from day one. The pair of students are caring for the patient in total, supported by their base supervisor in the bedside area and their head supervisor in practical caring science perspective. The students create a plan together for how they would like to care for the patient, and they present this plan to their base supervisor, who in a reflective dialogue discusses the plan with the students. Learning in pairs increases their time for reflection during their clinical practice, since they always have each other to reflect with. Learning in pairs becomes a way for students to enable reflection of their common caring experiences and a way to develop their reflective and professional caring attitudes. Students collaborate during their five weeks of clinical practice, but after two- or three-weeks students care for patients on their own. Students are always encouraged by their supervisors to return to each other for support in caring for their patients. Additional support to the students in caring for the patients is offered by the supervisors by being available for the students and having a supervisory approach, guided by reflection (Holst, et al., Citation2017b; Holst & Hörberg, Citation2013). Students’ experiences of learning in pairs are described as being both sensitive and as providing opportunities for learning together. An optimal learning in pairs is created when students are supporting each other’s learning by providing a base of security and their common conditions opens for honest exchange of knowledge (Holst & Hörberg, Citation2012, Citation2013).

Group supervision for the students participating in DLCU

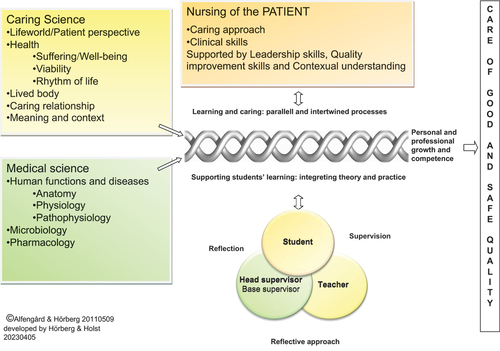

Students participating in DLCU have group supervision once a week during their five weeks of clinical practice. Students that are learning within the same unit or clinic are gathered with their responsible head supervisor and teacher. The student pairs take turns presenting a patient narrative that the group will reflect upon together. The reflection is based on caring science with a lifeworld perspective and aims to interlace the students’ experience, patient’s narrative, a caring science practical perspective, a caring science theoretical perspective, and a medical perspective to create a holistic perspective of the care provided for the patient (Ekebergh, Citation2009, Citation2011). The supervision in group is illustrated in .

Conclusive reflection

Caring and learning based on caring science with a lifeworld perspective shows that patients play a central role in students´ learning in pairs and that the encounters between the pairs of students and patients create a foundation for students’ learning. From a lifeworld perspective, learning cannot be separated from life, which also applies to learning to care (Holst et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, to implement DLCU, is , to meet and understand the lifeworld of the patients and the students. However, implementing DLCU requires a respectful cooperation between clinic and academic, referring to make the best use of everyone´s knowledge . To implement DLCU requires great commitment from both university and clinic. A disadvantage of upholding a DLCU is that a high staff turnover requires training and introduction to be able to adopt a reflective supervisory approach in clinic. However, it can be a struggle for some students to understand a lifeworld-led caring, learning in pairs could be helpful in this struggle, since learning in togetherness opens to understand different approaches in caring. It is shown in earlier research (Holst, et al., Citation2017a; Holst & Hörberg, Citation2012, Citation2013) that to reduce the risk of negative concurrence between the students, they need support from their supervisors. .

Furthermore, supervisors also support students learning to care for patients as described above by reflection in group of students, by supporting students to create a holistic understanding of the patient’s situation, including learning about leadership, quality improvement, clinical skills and contextual factors that influence the care. If the condition of understanding patients from a holistic perspective is missing, there is a risk of creating fragmented caring, where patients´ vulnerability and safety needs to be considered (Holst, et al., Citation2017b).

Reflection founded in students’ lived experiences based on caring action for the patient supports students in creating reflective dialogues within pairs of students as well as in group with the supervisor to link theoretical and practical knowledge. The reflection must be supported and given space to reach its full potential. By a reflective supervisory approach, the aim is to support the individual student in problematizing the encounter with the patient supported by reflection. The supervisor is showing respect towards the students by supporting learning in ‘togetherness’, where individual students are also reached and seen. Students’ ability to create a balanced learning cooperation is based on a balanced supervisory approach, which in turn is based on reflection and meant to illustrate the importance of collaboration between students. The supervisory approach is guided by reflection based on the theory of the lifeworld, which means waiting and giving time to students’ education by creating opportunities for a mutual exchange of knowledge and experiences between patients, students, and supervisors. The theoretical foundation also acts as a support for supervisors to uphold a reflective supervisory approach, as well as group-based supervision, to enable supervisors to find strategies for supporting students’ education in clinical practice (Holst, , et al., Citation2017a).

Implications to ensure learning that contributes to well-educated nurses

Caring and learning supported by caring science with a lifeworld perspective to ensure caring and learning based on a holistic perspective that includes the individual patient and student.

The patient plays a central role in students’ learning to care and must be cared for by a holistic perspective to reduce the risk of creating fragmented caring.

Learning in pairs of students need to be supported and balanced by a reflective supervising approach.

The supervisory approach needs to be balanced by providing guidance for instructors and pedagogical changes in medical education, based on caring science didactics with a lifeworld perspective.

Creating a collaboration between clinic and university to involve and use competence and knowledge from both perspectives in the best way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hanna Holst

Hanna Holst is a senior lecturer, and she is a member of the research group Lifeworld led Health, Caring and Learning (HCL) at Linnaeus University. Hanna has many years of experience teaching caring science and supervision at all educational levels, and she has developed the lifeworld led learning in clinical practice at Linnaeus University. Her research explores nursing students learning in health care contexts.

References

- Adamson, E. (2018). Helping student nurses learn the craft of compassionate care: A relational model. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 6(3), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v6i3.376

- Adamson, E., & Dewar, B. (2015). Compassionate care: Student nurses´ learning through reflection and the use of story. Nurse Education in Practice, 15(3), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.08.002

- Andersson, N., Ekebergh, M., & Hörberg, U. (2020). Patient experiences of being cared for by nursing students in a psychiatric education unit. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 40(3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057158519892187

- Aston, L., & Molassiotis, A. (2003). Supervising and supporting student nurses in clinical placements: The peer support initiative. Nurse Education Today, 23(3), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0260-69170200215-0

- Cant, R., Ryan, C., & Cooper, S. (2021). Nursing students’ evaluation of clinical practice placements using the clinical learning environment, supervision and nurse teacher scale – a systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 104, 104983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104983

- Dahlberg, K. (2011). Lifeworld phenomenology for caring and health care research. In G. Thomson, F. Dykes, & S. Downe (Eds.), Qualitative research in midwifery and childbirth phenomenological approaches (First ed., pp. 19–34). Routledge.

- Dahlberg, K., & Ekebergh, M. (2008). To use a method without being ruled by it: Learning supported by drama in the integration of theory with healthcare practice. The Indo- Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 8(sup1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2008.11433976

- Edgecombe, K., & Bowden, M. (2009). The ongoing search for best practice in clinical teaching and learning: A model of nursing students’ evolution to proficient novice registered nurses. Nurse Education in Practice, 9(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.10.006

- Edgecombe, K. K. Edgecombe & M. Bowden red. (2014). Dedicated education units in nursing: The concept. I: Clinical learning and teaching innovations in nursing: Dedicated education units building a better future. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7232-8

- Ekebergh, M. (2005). Are you in control of the method or is the method in control of you? Nurse Educator, 30(6), 259–262. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200511000-00011

- Ekebergh, M. (2007). Lifeworld-based reflection and learning: A contribution to the reflective practice in nursing and nursing education. Reflective Practice, 8(3), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940701424835

- Ekebergh, M. (2009). Developing a didactic method that emphasizes lifeworld as a basis for learning. Reflective Practice, 10(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802652789

- Ekebergh, M. (2011). A learning model for students during clinical studies. Nurse Education in Practice, 11(6), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.03.018

- Ekebergh, M., Andersson, N., & Eskilsson, C. (2018). Intertwining of caring and learning in care practices supported by a didactic approach. Nurse Education in Practice, 31, 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.008

- Ekebergh, M., & Lindberg, E. (2020). The interaction between learning and caring - the patient’s narrative as a foundation for lifeworld-led reflection in learning and caring. Reflective Practice, 21(4), 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1783223

- Eskilsson, C., Carlsson, G., Ekebergh, M., & Hörberg, U. (2015). The experiences of patients receiving care from nursing students at a dedicated education unit: A phenomenological study. Nurse Education in Practice, 15(5), 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.04.001

- Hendersen, A., Briggs, J., Schoonbeek, S., & Paterson, K. (2011). A framework to develop a clinical learning culture in health facilities: Ideas from the literature. International Nursing Review, 58(2), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00858.x

- Holst, H., & Hörberg, U. (2012). Students’ learning in an encounter with patients – supervised in pairs of students. Reflective Practice, 13(5), 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.670623

- Holst, H., & Hörberg, U. (2013). Students learning in clinical practice, supervised in pairs of students – a phenomenological study. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 3(8). https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v3n8p113

- Holst, H., Ozolins, L.-L., Brunt, D., & Hörberg, U. (2017a). The experiences of supporting learning in pairs of nursing students in clinical practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 26, 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.06.002

- Holst, H., Ozolins, L. L., Brunt, D., & Hörberg, U. (2017b). The learning space—interpersonal interactions between nursing students, patients, and supervisors at developing and learning care units. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 1368337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2017.1368337

- Holst, H., Ozolins, L. L., Brunt, D., & Hörberg, U. (2023). The perspectives of patients, nursing students and supervisors on “the caring–learning space”–a synthesis of and further abstraction of previous studies. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 18(1), 2172796. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2023.2172796

- Hörberg, U., Carlsson, G., Holst, H., Andersson, N., Eskilsson, C., & Ekebergh, M. (2014). Lifeworld-led learning takes place in the encounter between caring science and the lifeworld. Clinical Nursing Studies, 2(3), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.5430/cns.v2n3p107

- Hörberg, U., Galvin, K., Ekebergh, M., & Ozolins, L.-L. (2019). Using lifeworld philosophy in education to intertwine caring and learning: An illustration of ways of learning how to care. Reflective Practice, 20(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2018.1539664

- Hörberg, U., Ozolins, L.-L., & Ekebergh, M. (2011). Intertwining caring science, caring practice and caring education from a lifeworld perspective – two contextual examples. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v6i4.10363

- Husserl, E. (1929/1992). Cartesianska meditationer: en inledning till fenomenologin Ursprunglig titel: Cartesianische Meditationen. Eine Einleitung in die Philosophie. Daidalos.

- Husserl, E. (1936/1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology [Ursprunglig titel: Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die phänomenologische Philosophie]. Northwestern University Press.

- Kolderstam, M., Broström, A., Petersson, C., & Knutsson, S. (2021). Model for improvements in learning outcomes (MILO): Development of a conceptual model grounded in caritative caring aimed to facilitate undergraduate nursing students’ learning during clinical practice (Part 1). Nurse Education in Practice, 55, 103144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103144

- Masters, K. (2016). Integrating quality and safety education into clinical nursing education through a dedicated education unit. Nurse Education in Practice, 17, 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.12.002

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945/2002). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge. [Ursprunglig titel: Pehnoménologie de la perception]. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994610

- Pålsson, Y., Mårtensson, G., Swenne, L. C., Ädel, W., & Engström, M. (2017). A peer learning intervention for nursing students in clinical practice education: A quasi- experimental study. Nurse Education Today, 51, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.01.011

- Pilhammar, E. A. (1999). From vocational training to academic education: The situation of the schools of nursing in Sweden. Journal of Nursing Education, 38(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-19990101-10

- Rosser, E. A., Scammel, J., Heaslip, V., White, S., Phillips, J., Cooper, K., Donaldson, I., & Hemingway, A. (2019). Caring values in undergraduate nurse students: A qualitative longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 77, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.03.011

- Severinsson, E. (1998). Bridging the gap between theory and practice: A supervision programme for nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27(6), 1269–1277. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00644.x

- Stenberg, M., & Carlson, E. (2015). Swedish student nurses’ perception of peer learning as an educational model during clinical practice in a hospital setting-an evaluation study. BMC Nursing, 14(48), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0098-2

- Strömwall, A., Ozolins, L.-L., & Hörberg, U. (2018). “Seeing the patient as a human is their priority” – Patients’ experiences of being cared for by pairs of student nurses. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 8(7), 97. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v8n7p97

- Vuckovic, V., & Landgren, K. (2020). Peer learning in clinical placements in psychiatry for undergraduate nursing students: Preceptors and students’ perspective. Nursing Open, 8(1), 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.602