ABSTRACT

Most initial teacher education (ITE) programmes claim to develop reflective practitioners. Peer review is one means of developing reflective practice. In this study, Post-Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) Physical Education (PE) students engaged in a process of peer review to investigate how reviewees used feedback from reviewers to inform their reflections. Eleven post-lesson feedback audio recorded discussions were collected along with 11 reflection templates and 2 focus group interviews. In response to both low-quality and high-quality feedback received, students’ reflections were low-quality (pre-reflective and surface level) and/or high-quality (pedagogical). None reflected at the highest, critical, level. Students valued the peer review process, with some noting that the feedback often triggered deeper reflection, whilst for others the feedback was accepted uncritically. The process also allowed for sharing of ideas and for some reviewers, it triggered deeper thinking about their practice. Results are discussed in relation to developing students’ reflective practice.

Introduction

The motivation for this study derived from the author’s experience as a teacher educator where during his first 3 years he struggled to develop and improve students’ reflective capabilities. Prior to undertaking this study, the author noted that the quality of reflective work produced by the PGCE PE students was poor, with many producing very descriptive accounts of their teaching experience. Attempts were made to support students by providing a structured lesson reflection template. However, the majority of the reflective accounts were still categorised as descriptive, a standard that appears to be very common among prospective teachers (Poom-Valickis & Mathews, Citation2013). The author then decided to explore collaborative approaches to reflection, considered more effective than individual reflection (Kuit & Gill, Citation2001).

Dewey (Citation1933) defined reflection as, ‘turning a subject over in the mind and giving it serious and consecutive consideration … . Reflection involves active, persistent and careful consideration’ (p.9). Dewey (Citation1933) believed that reflective thinking should not be routinized, but rather a process that ‘emancipates us from merely impulsive and merely routine activity’ (p.17). Dewey’s work, therefore, provided the basis for the concept of ‘reflective practice’ (Finlay, Citation2008), which rose to prominence with the work of Schon (Citation1983). In his work, ‘The reflective practitioner’, Schon (Citation1983) identified two types of reflection: reflection in-action (during the event) and reflection on-action (after the event). However, despite a wealth of writing on the topic, attempts to define the nature of reflective practice have proven difficult (Parsons & Stephenson, Citation2005). According to Bell et al. (Citation2011, p. 799) the concepts of, ‘Reflection, reflective thinking, reflective learning and critical reflection are not clearly defined’. Reynolds (Citation1997) makes a clear distinction between reflection and critical reflection, by arguing that reflection is ‘concerned with practical questions about what courses of action can best lead to the achievement of goals or solutions’ whilst critical reflection ‘involves engaging with individual, organisational or social problems with the aim of changing the conditions which give rise to them, as well as providing the basis for personal change’ (p. 314). From this definition, it could be argued that reflection is operational whilst critical reflection is political (Smyth, Citation1989).

Despite the confusion surrounding reflection, it is important to note that over the years it has gained momentum in education (Fathi & Behzadpour, Citation2011). Fathi and Behzadpour (Citation2011) claimed that considering the discord that exists between theoreticians and practitioners, reflective practice was introduced because it was viewed as a ‘solution to the dilemma’ (p. 242). The General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland (GTCNI, Citation2011) describes teaching as ‘the reflective profession’ and their teaching competences mandate reflection, stating that reflective practice is the central component ‘which underpins the Council’s concept of competence’ (GTCNI, Citation2011, p. 12). This study investigates the use of feedback in peer review for developing student teachers’ reflective skills.

Whilst the use of peer review discussions and feedback for developing reflection has previously received attention (Lamb et al., Citation2012; McGarr et al., Citation2019), this study takes the research a step further in that it explicitly identifies how reviewer feedback impacts the reflective thinking of reviewees. Audio recordings of the peer feedback discussions are used and analysed to determine the type and content of the feedback. The students’ subsequent written reflections are analysed against Larrivee’s (Citation2004) reflective framework to identify if and how particular types and content of feedback impacted on students’ reflective work. Whilst other studies have shown that peer review can build confidence, promote reflective thinking (Weller, Citation2009) and enhance professional development (Desimone, Citation2011), no previous studies have analysed audio recorded peer feedback and mapped the impact of specific feedback content on students’ reflective practice, thus highlighting a gap in the field. This approach is unique in that the reviewee has the opportunity to listen to the recorded feedback discussion as opposed to simply relying on their note taking and memories from such feedback discussions. The researcher utilises focus group interview data to support the analysis and establish reasons as to why or how the peer feedback impacted students’ reflective work. This study shows that peer feedback can positively impact students’ reflective work, but for other students, there is little impact, supporting the work of Bard (Citation2014) and Hatzipanagos and Lygo‐Baker (Citation2006) respectively. Further, it suggests that there are other professional benefits associated with peer review and that there is a need to invest more time and effort to improve student teachers’ ability to engage with peer review (Lamb et al., Citation2012).

Reflection in initial teacher education

According to Day et al. (Citation2022), reflective practice is a critical component of teacher education, whilst Lane et al. (Citation2014) point to the long tradition of research which highlights the important role that reflection plays in ITE programmes. The consensus of this literature is that building reflective practice skills requires explicit teaching and modelling of evidence-based practice and the delivery of specific feedback for student teachers (Shoffner, Citation2008). Boulton and Hramiak (Citation2012) in reference to their 15 years of educating teachers emphasised, however, that one of the most difficult aspects for students on a teacher education course is developing a professional level of reflection and that prospective and novice teachers normally demonstrate rather low levels of reflection (El-Dib, Citation2007).

According to Shoffner (Citation2008), teacher educators often rely on certain frameworks to configure and guide reflective practice where student teachers are provided with specific guidelines in which to situate their reflection. She emphasised that such an approach censors alternative ways of approaching reflection and that pre-service teachers often accept that using a structured framework is the only way to reflect. Larrivee (Citation2008) however, argues that ‘without carefully constructed guidance, prospective and novice, as well as more experienced, teachers seem unable to engage in pedagogical and critical reflection to enhance their practice’ (p. 345). Larrivee (Citation2004) developed a framework where she identified four levels of reflective activity in teachers’ practice, ranging from low to high. These are as follows: pre-reflection, surface reflection, pedagogical reflection, and critical reflection (see Figure S1).

Hatton and Smith (Citation1995) support Larrivee’s views on the need for structure and guidance when developing reflection. They suggested that progression through the various levels of reflection is likely to be developmental in that teachers may need to reflect on technical aspects of teaching first, thus indicating a structured approach to guiding reflective practice.

Yee et al. (Citation2022) emphasise that journal writing is one of the most often-used methods of developing reflection in pre-service teacher education. Engagement with journal writing or other similar forms of reflective writing involves preservice or practicing teachers examining their practice introspectively (Finlay, Citation2008), an exercise which is predominantly individualistic (Reynolds & Vince, Citation2004). Finlay (Citation2008) recognises the onus on individuals to lead their reflection without meaningful collaboration as a weakness of reflective practice and that a mutual, reciprocal, and shared approach is required.

In recent years, there have been calls for a more collaborative approach to reflection (Lin et al., Citation2014), using web blogs (Xie et al., Citation2010), online communities of practice (Daniel et al., Citation2013) and peer review (Lamb et al., Citation2012). Web blogs and online communities of practice have received significant research attention in the research field, but the use of peer review in developing reflection has not had the same attention to date. It is therefore intended that this study will add to the research on the effectiveness or not of peer review for facilitating reflective practice.

Peer review and peer observation

Having acknowledged that the terms peer review and peer observation are used interchangeably, Hendry et al. (Citation2014) made a distinction between the terms. The critical difference for them is that in peer review the observer is required to provide feedback whilst in peer observation an observer can observe without providing feedback. The authors have used the distinction by Hendry et al. (Citation2014) as a guide to their use of the terms peer review and peer observation.

Peer review and reflective practice

Weller (Citation2009) argued that peer observation builds confidence and promotes reflective thinking whilst Hatzipanagos and Lygo‐Baker (Citation2006) note that despite the potential benefits to be gained, there remain doubts about the extent to which the process can enhance teachers’ reflective skills. Lamb et al. (Citation2012) utilized peer review in their study with 23 PGCE Physical Education (PE) student teachers and discovered that the students created a ‘number of spaces’ which helped to ‘foster the peer-review process for their reciprocal support and benefit (p. 34). The spaces identified were as follows: ‘safe, relaxed, equal, pedagogic, alternative and negotiated’ (p. 34).

Moon (Citation1999) believed peer review to be more effective than individualistic reflection since the involvement of others helps to ‘deepen and broaden the quality of the reflection’ (p. 172). Hammersley‐Fletcher and Orsmond (Citation2005) emphasized that the success of peer review is dependent on the ‘ … practice of those conducting observations’ (p. 213), a view supported by Gosling (Citation2009) who claims that many peer reviewers are ill-equipped to provide feedback on others’ teaching practices. Yiend et al. (Citation2012) argue that this claim by Gosling raises many doubts about the value of peer review in developing teachers’ critical reflective skills.

Bard (Citation2014) considered feedback to be a crucial element in the reflective process, emphasising that most of the difficulties surrounding the implementation of reflective practice results from the feedback that teachers receive. Nicol (Citation2010) added further support to this argument by emphasizing that for learning to occur, students must make use of the transmitted information by analysing the content, asking questions and discussing it with others in relation to prior understanding and future actions. It would seem that the feedback aspect of peer review is of fundamental importance in facilitating meaningful reflective practice.

Purpose of study

It has been noted above that very few studies have researched the direct impact of peer feedback discussion on the quality of reflections produced (Xie et al., Citation2008). Considering therefore, the significance of feedback in peer review for facilitating reflective practice by student teachers and teachers, this study was designed to examine the following research questions:

How do pre-service teachers use peer feedback when reflecting on their practice?

What are the views of pre-service teachers on engaging with the process of peer review for developing reflective practice?

Methodology

Sample

Purposive and convenience sampling was used to select the study participants (n = 11), the total population of those training to be PE teachers in Northern Ireland. The students were enrolled in a full-time (36 weeks) ITE programme that comprised of 12 weeks of university teaching and 24 weeks of school placement. Each student completed 12 weeks in two different schools. Six female and five male students comprised the group.

Procedure

The study developed as a result of a pilot study where PGCE PE students (n = 13) from the previous academic year engaged in a process of peer review. Having analysed the pilot study findings and identified areas for improvement, the revised version of peer review was implemented with the PGCE PE group during the following academic year. The students participated in a number of preparatory feedback workshops specifically designed to support the peer review process. In these workshops, the students explored different types of feedback and the content of feedback i.e. technical, pedagogical, or critical. The PGCE tutor used this opportunity to model effective feedback, a process considered beneficial for those less experienced (Daniel et al., Citation2013).

During the students’ second teaching practice (March–May) each student was required to conduct one peer review (as a reviewer) as well as have their own teaching peer reviewed (as a reviewee), meaning that each student would experience both roles. It was hoped that the use of peer review would allow the students to explore reflection in a collaborative and supportive environment (Buchanan & Stern, Citation2012) free from the involvement of teacher mentors and subject tutors who tend to be viewed as assessors (Bard, Citation2014).

Data collection

Data were collected through audio recorded post-lesson feedback discussions, written post lesson peer review reflection templates (to answer research question 1 & 2), and focus group interviews (answer research question 2). The audio recordings would allow the researcher to identify the types of feedback used by each reviewer as belonging to one of the following types, as identified by Scheeler et al. (Citation2004): corrective feedback, non-corrective feedback, general feedback, positive feedback, and specific feedback. Based on the initial reading of the transcripts, it was decided to add a 6th feedback type, known as suggestive feedback (Van der Schaaf et al., Citation2013).

The audio recordings also permitted the researcher to identify the content of each feedback segment in terms of whether the issues addressed were technical, pedagogical, or critical (M. Bell, Citation2001).

Comparison of each student’s reflection with the feedback discussion allowed for identification of the feedback discussion segments they chose to reflect upon.

Students used their iPad to record these discussions with the use of a recorder app. Eleven post-lesson feedback discussions were recorded, with the shortest recording lasting 4 min 32 s and the longest recording lasting 14 min and 8 s. The post-lesson reflective template was completed by each reviewee immediately after their post-lesson discussion, meaning that 11 templates were collected. Participants were instructed to reflect on the issues that were identified during the discussion and to highlight issues that emerged during the discussion that the reviewee had not noted in their initial lesson annotation. No word limit was placed on these reflections.

When all peer review sessions were completed, two focus group interviews took place, one that included five participants and the other six participants.

Data analysis

All 11 audio recorded feedback discussions were transcribed word-for-word by the researcher. The quality of feedback generated in each feedback discussion was determined by analysing the type of feedback and the content focus of each feedback segment through the coding of keywords and phrases. To increase the accuracy of this work, an experienced teacher educator colleague who was familiar with the six feedback categories in and the content categories in , repeated the content analysis process for four transcriptions. This gave the researcher the opportunity to compare the analysis which produced an 85% agreement. The slight disagreements (15%) were debated, before arriving at a consensus. Armstrong et al. (Citation1997) argue that ‘comparison with the original findings can be used to reject, or sustain, any challenge to the original interpretations’ (p. 598).

Table 1. Types of feedback.

Table 2. Feedback content.

The other key focus of the analysis was to identify the type and content of feedback each student chose to reflect upon to determine if the feedback discussion impacted students’ reflections. The content of each lesson reflection was compared to the type and content of the feedback discussion to determine which feedback segments the reviewees chose to reflect upon and how they reflected on them.

Both focus group interviews were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step approach to thematic analysis. In step 1, both interviews were transcribed word for word by the researcher which allowed for familiarisation with the data. Having analysed the transcripts, initial codes were then produced at stage 2 and once coding was complete, further analysis led to the identification of key themes (stage 3). An inductive approach to the data as proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) led to the establishment of codes and themes. Stages 4, 5, and 6 involved reviewing the themes, naming the themes, and compiling the report.

Ethics

The researcher was fully cognisant of his conflicting roles as PGCE tutor and researcher, therefore the PGCE students were fully aware that they could withdraw from this study at any stage and that if they were to make such a decision that this would not in any way adversely impact their progress. The research was approved by the University Research Ethics Filter Committee. The researcher also adhered to BERA (Citation2011) guidelines for research when conducting this study.

Findings

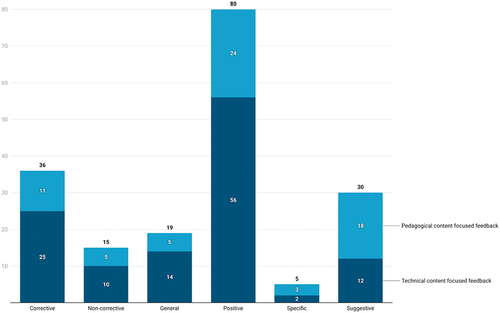

provides an overview of the types, content, and frequency of feedback delivered by reviewers (note: does not include critically focused feedback as analysis showed that there was no critically focused feedback delivered by reviewers).

Feedback provided

Feedback utilized for reflection

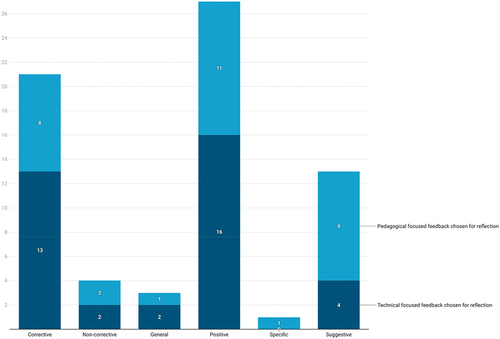

shows the feedback types and content utilized by the reviewees.

Each reflection was analyzed with a view to identifying the types of feedback that appeared to impact each student’s reflection and how the students chose to reflect on the feedback segments. The low number of segments chosen from specific, non-corrective, and general feedback suggest that these feedback types had little impact upon students’ reflections and thus will not be subjected to in-depth analysis. The other three feedback types will be the main focus of the presentation of the findings and subsequent analysis.

The most frequent category addressed was positive (27), with nine students choosing to address at least one positive segment in their reflection (16 technical; 11 pedagogical). Six of these students reflected at a descriptive/pre-reflective level by basically repeating what their reviewer had said to them without reflecting more deeply on the issue. For example, having been told that her ‘voice projection was very good’, student A reflected, ‘my voice projection was very strong’. Student F was told that his ‘classroom management was very good’, referring to this in his reflection by stating, ‘I managed the class very effectively’. When asked in the focus group interview whether the peer feedback helped or not with their reflection, student A stated, ‘the feedback from xxxx was good, it sort of helped me see what things needed improving and it was good that they were seeing the same things as me’ and student F stated, ‘the feedback was helpful in that it made me focus on those things in my reflection … cos if they hadn’t mentioned some of the points, I’m not sure I would have reflected on those’.

The remaining three students analysed the positive feedback in greater depth. For example, having been told by her reviewer that the ‘warm up was relevant and fun’ (general teacher issue), student D reflected by stating, ‘the warm up was very relevant to the javelin and it prepared the pupils both mentally and physically for what was to come. Pupils could see the links between the warm up and the opening development activity’. Student D chose a positive, technical feedback segment and reflected on this by producing a pedagogical reflection. Having received the comment, ‘your decision to use whole-part-whole was very effective’ (pedagogical focus) student G stated that, ‘the whole-part-whole approach worked well as the pupils had the opportunity to explore the skill in a realistic way before breaking it into the various components, although I should have differentiated the tasks better to suit some of the weaker kids’. Student G made reference to this feedback in the focus group, stating, ‘when I was told by xxxxx that I used whole-part-whole well, it made me think why I chose that teaching approach, but it also made me think about the task and it was only then I realised that they could have been differentiated much better … so if that hadn’t been mentioned, I would not have thought about the issue so you could say that the feedback made me think more deeply about the issue’. Thus, pedagogical feedback was reflected on pedagogically more deeply by making relevant links to practice and analysing why this approach was effective. These three students have shown an ability to reflect on positive feedback segments, both technical and pedagogical, in greater depth.

All 11 students chose to address at least one corrective segment. Six students (A, C, E, F, I, J) reflected at a surface level on technical feedback by simply repeating what their reviewer told them. For example, student C received the comment, ‘your classroom management could have been better. It is important to gain attention before speaking and use some of the less intrusive strategies such as proximity praise’, to which she responded in her reflection by stating, ‘I need to improve my management of this class and ensure I always gain their attention. I should be using less intrusive strategies’. Student C referred to this in the focus group, stating that ‘when xxxx said I need to improve my classroom management, it made me aware of this going forward. It is good to have that other viewpoint’. It seems that student C benefitted from the feedback in that it brought the issue to her attention, but it is not clear why student C did not reflect more deeply on this issue.

Similar comments were made by students F and J, where again they were grateful for having been made aware of issues that they could consider going forward. These reflective segments were assessed as being ‘surface’ level since the students may have repeated the feedback they were given, but they were accepting responsibility and identifying aspects of their practice that required improvement. However, reflecting on these issues did not trigger deeper reflection.

The remaining five students (B, D, G, H, K) displayed their ability to reflect on pedagogical corrective feedback segment(s) pedagogically in greater depth, beyond the feedback they received. For example, having been told that ‘you should have provided more individual feedback, particularly to those pupils who were struggling’ student B stated, ‘providing more feedback to these pupils may have helped but the bigger issue is that I thought they were ready for this activity but they weren’t, so it would probably be better to think of what I should have done to prepare them better or should they have been doing this activity at all? A more suitable activity for their needs is actually what they needed’. Student B touched on this issue during the focus group when he stated, ‘when xxxx said that I should have given more feedback to the weaker pupils, it sort of dawned on me that there was a bigger issue at play and I’m not so sure I would have reflected more on that if I hadn’t received that feedback’. Students D and G also stated in the focus group that the corrective feedback they received forced them to focus on the issue, and as a result, they both reflected more deeply on the issue. This evidence shows that the peer feedback for these students triggered deeper reflection.

Six students (B, D, E, G, H & I), addressed suggestive segments in their reflections. When the reviewer asked, ‘what could you have done with the two boys who were struggling with bowling’? student H reflected, ‘I should have differentiated the bowling activities much better. I was aware that *** and **** were struggling a little but looking back I realize that I should have allowed them to revisit their technique by breaking the skill down and using a slower ball’. The reviewer also asked, ‘what other teaching strategies might you have employed as it was too teacher led at times?’, with student H reflecting, ‘I should have utilized a TGfU (Teaching Games for Understanding) approach whereby the pupils had the opportunity to explore bowling and focus on developing their technique’. Student H considered the question and then provided a reflective thought that was pedagogical in nature.

The other five students also managed to reflect more deeply on the issue raised, whereas as previously noted, this was not the pattern for all those who reflected on positive and corrective segments. In the focus group, student D stated, I found the questions that xxxx asked were very good in that when it came to doing my reflection, I knew I had to address these questions as I wasn’t able to answer them fully during the post-lesson feedback session … the questions made me reflect more deeply on the issue … like one of the areas I had noted in my lesson annotation but because of considering the question I had to think more about it and then realised there were things I hadn’t thought about … I suppose I tended to reflect on the questions as they were linked to pupil learning and that is always my focus when reflecting, how I can think about improving pupil learning. Students A and K both received suggestive feedback but failed to address any of the segments in their reflections. Considering how some of the participants used this feedback to good effect, it would seem that the decision to not reflect upon this type of feedback segment may be significant. Students A and K both addressed the highest number of positive, technical segments compared to the other students and produced low quality reflections which were graded as pre-reflective. When asked during the focus group to explain why they chose particular feedback segments to reflect on and not others, student A stated, ‘I suppose I just listened back to the feedback and picked up on things I thought were important … I’m hearing others talk about responding to the questions they were asked and I’m not sure why I didn’t address the questions I got … perhaps I should have but I tend to go with the definite things xxxx said … maybe I just need to think more for myself then’. This shows that for most students, suggestive feedback positively impacted their reflective work, whereas for the minority, it failed to have any impact.

Focus group findings

In addition to the specific focus group comments included above, other key themes emerged during the focus group.

Reviewer thinking

There was a consensus across both groups that when reviewing their peer’s lesson, they thought more about their own practice. Student G stated, ‘when I was watching xxxxx teach, it really got me thinking about the way I do things and I actually jotted down some ideas for myself that I then used in my own lessons’. Student D had a similar experience, stating, ‘observing xxxxxx was brilliant because I picked up some great tips but it also made me think about my own practice and areas that I could improve on’. Student A stated, ‘It was good in that I picked up a couple of ideas but it also made me realise that what I was doing was just as good, sort of a confidence booster’. Student K held a similar view, seeing the process as confirmation of their own practice rather than triggering thoughts or reflections on their practice.

Pressure free

Across both focus groups, all participants agreed that the peer review process was a more relaxing experience than being observed by university tutors or school mentors. Student J’s comment reflected the views of both groups when stating that it just felt less pressured, ye know when you (Uni tutor) would be coming in, I’d be thinking, flip, I better do this, do that and get myself worked up whereas when xxxxx came in I was thinking, I can really be myself and if the lesson doesn’t go well, sure it’s no big deal. Student E stated, ‘I liked it, because it allowed me to take a risk and try something out that I would have not tried if you were observing or my mentor and it actually went well so I suppose that in itself is a positive because the situation allowed me to experiment … it was nice to feel that I was not really being assessed’.

Professional dialogue

Across both groups there was a recognition of the value of the feedback session. Students appreciated the time to sit down and discuss issues at length. Student I stated, ‘it was just good to be able to sit down and chat about the lesson without feeling rushed as you are normally thinking about the next class but because the time was given to this, it actually meant we could discuss things in detail … it really was a discussion as opposed to just listening to feedback and that was refreshing’. Student E also emphasised the importance of being given time to carry out the process, stating, ‘being able to sit down and discuss my lesson at length with xxxx was great as we actually got to discuss everything we needed to whereas normally it is a 30 second conversation with the mentor and you move on … it felt that we were equals in the process whereas the rest of the time we are being assessed or judged by someone more experienced … it felt like how professional dialogue should be and I hope that’s how it is when I get a job’. The following section discusses these findings.

Discussion

This section addresses the key issues emerging from the findings, beginning with a discussion surrounding the types of feedback that reviewees chose to reflect upon and how this influenced their reflections.

Impact of feedback on students’ reflections

Whilst the majority of students chose to reflect on positive feedback, relative to the total number of positive feedback segments delivered by reviewers, the actual utilization of positive feedback by reviewees is low. This shows that the students preferred to reflect on corrective feedback, suggesting that they may find it more useful. Scheeler et al. (Citation2004) argue that corrective feedback can be very effective at promoting reflection, allowing ‘teachers to plan and achieve new goals’ (Feeney, Citation2007, p. 193). However, some students accept corrective feedback without question and the directness of such feedback could possibly inhibit students’ reflection. Van der Schaaf et al. (Citation2013) found that the students in their study uncritically accepted the feedback they were given and based their reflections on the feedback without any analysis. Some students in this study welcomed the corrective feedback, and whilst it is a positive that it may have raised their awareness of issues that required attention, it shows that these students did not use the feedback to reflect more deeply on their practice. For those students who managed to reflect more deeply on the feedback, they point to the feedback triggering deeper thoughts, showing that the feedback impacted their thinking on the issue(s).

When reflecting on positive and corrective feedback segments, many of these students produced low level descriptive accounts that were either pre-reflective or surface level, although others reflected on positive and corrective segments in greater depth, with the focus on teaching/pedagogical issues. It is common for beginning teachers to reflect on issues in a very descriptive manner as they tend to reflect on aspects of their teaching that permit survival by drawing on existing beliefs (McGarr & McCormack, Citation2014). The results of this study suggest that these PGCE PE students reflected differently when responding to positive and corrective feedback segments, which supports the earlier work of Lyons (Citation1998, p. 116) who found that ‘reflection was not uniformly achieved’ with clear differences between the levels at which individual teachers reflect. What we cannot say for certain, is why feedback is a trigger for one individual to reflect more deeply and not for another, but it does highlight that peer feedback can support reflective thinking.

For some students, reflecting on suggestive feedback has stimulated deep reflective thoughts where issues have been dissected and analysed, producing further questions or possible solutions/improvements for practice. These findings support the work of Van der Schaaf et al. (Citation2013) who found that suggestive feedback in the form of posing questions was very effective for stimulating feedback dialogue. This view was supported by Jyrhama (Citation2001) who found that the use of ‘why’ questions in post-lesson feedback discussions allowed student teachers the opportunity to critically reflect on their practice. Quinton and Smallbone (Citation2010) agreed that feedback can be used as a catalyst for developing reflection but that the quality of the feedback is the crucial factor (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998). For some of these students, their reason for choosing to focus on suggestive feedback and answer questions was due to their focus on pupil learning, whereas the two students who did not reflect on suggestive feedback seemed to be more focused on issues connected to their teaching, perhaps suggesting they were not developmentally ready to reflect at a higher level (Griffin, Citation2003). Another possible reason worth considering is that they may not have agreed with the reviewer’s feedback and thus became defensive and ‘resistant to suggestions of change’ (Cosh, Citation1998, p. 172).

Across each feedback type, some students have shown an ability to use low-quality feedback and reflect deeply on the issue. There are several possible reasons for this finding. First, the content of the feedback was enough to trigger deeper reflection by particular individuals and therefore without the feedback they would not have thought to reflect on the issues identified. Feeney (Citation2007, p. 193) argues, however, that ‘feedback in the form of shallow and meaningless comments devoid of any connection to student learning’ inhibits teachers’ reflective development. Likewise, the results show that some individuals produced low-quality reflections in response to high-quality feedback. Therefore, whilst the type and quality of feedback is important, in some instances, it is the individual student’s capacity for reflection which determines how effectively they use the feedback. This supports the work of Gün (Citation2011) who argues that whilst providing feedback to teachers is ‘undeniably useful’ it is often insufficient in helping ‘teachers reach a level of reflection that will optimize their professional development’ (p. 127).

When acting as reviewers, the process allowed for sharing of ideas and triggered thinking about their own practice. For some, the process helped justify their own practice (Loughran, Citation2000), whereas for others, it triggered deeper thinking about their practice in relation to seeking improvement (M. Bell, Citation2005; Zowzdiak-Myers, Citation2012). The recognition by some students that the peer feedback discussion made them aware of issues they would not have reflected upon had they not received the feedback, is significant, and highlights the benefits of collaborating with a peer (Yiend et al., Citation2012). Therefore, regardless of how deeply they reflected on such feedback, it impacted their thinking.

It is clear that peer review created opportunities for students to engage in reflective practice and for those who were less impacted, it still proved to be a positive experience. Feeling less pressure, taking risks and feeling like a professional are positives that cannot be ignored.

Conclusion

This study was undertaken to explore the process of peer review in relation to developing PGCE PE students’ reflective skills. The students in this study were different in how they utilised the feedback when reflecting on their practice. Across the three main feedback types analysed, some students were able to reflect more deeply on both low-quality and high-quality feedback, whereas others were not able to reflect more deeply on either low-quality or high-quality feedback. This shows that peer review can help to stimulate students’ reflective thinking, but that it may not be the best approach for some individuals. However, the positive views generated among the entire group indicate that they will be willing to engage with peer review when they become an in-service teacher. It is possible that with more regular engagement with peer review, these individuals will improve their opportunities for deepening their reflective skills and help to foster a collaborative approach to reflection and improving practice among their colleagues.

For anyone considering utilising peer review as an approach for developing the reflective skills of pre-service teachers, it is important to have participants engage with regular practical sessions that focus on the giving and receiving of feedback, where the focus is on modelling high-quality feedback, i.e. suggestive and corrective pedagogical feedback. Establishing clear protocols regarding the role of the reviewer and reviewee is also crucial to ensure that pre-service teachers have the opportunity to maximise their learning when engaged in this process.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (96.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2024.2309880

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Paul McFlynn

Paul McFlynn is a Senior Lecturer in Education and course director for the Post Graduate Certificate in Education (Physical Education) at Ulster University in Northern Ireland. His research to date has concentrated on the role of critical reflection in initial teacher education and on the role of mentoring in initial teacher education.

Barbara Skinner

Barbara Skinner is a Professor of Education and TESOL at Ulster University in Northern Ireland. Her work focuses on teaching and researching in multicultural/multilingual education contexts. Currently, her research projects focus on supporting the teaching and learning of migrant children in schools and online, building partnerships between schools and migrant families and exploring the socio-emotional wellbeing of refugee children in Northern Irish primary schools. Her work also includes developing university partnerships overseas as well as being a member of council for the British Educational Research Association.

References

- Armstrong, D., Gosling, A., Weinman, J., & Marteau, T. (1997). The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology, 31(3), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031003015

- Bard, R. (2014). Focus on learning: Reflective learners & feedback. TESL-EJ, 18(3), 1–18.

- Bell, M. (2001). Supported reflective practice: A programme of peer observation and feedback for academic teaching development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440110033643

- Bell, M. (2005). Peer observation partnerships in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia Inc.

- Bell, A., Kelton, J., McDonagh, N., Mladenovic, R., & Morrison, K. (2011). A critical evaluation of the usefulness of a coding scheme to categorise levels of reflective thinking. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(7), 797–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2010.488795

- BERA. (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. Resources for Research.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

- Boulton, H., & Hramiak, A. (2012). E-flection: The development of reflective communities of learning for trainee teachers through the use of shared online web logs. Reflective Practice, 13(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2012.670619

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buchanan, M. T., & Stern, J. (2012). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the benefits of peer review. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 38(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2012.643654

- Cosh, J. (1998). Peer observation in higher education ‐ a reflective approach. Innovations in Education and Training International, 35(2), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355800980350211

- Daniel, G. R., Auhl, G., & Hastings, W. (2013). Collaborative feedback and reflection for professional growth: Preparing first-year pre-service teachers for participation in the community of practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2013.777025

- Day, S. P., Webster, C., & Killen, K. (2022). Exploring initial teacher education student teachers’ beliefs about reflective practice using a modified reflective practice questionnaire. Reflective Practice, 23(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2022.2048260

- Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171109200616

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Houghton-Mifflin.

- El-Dib, M. A. B. (2007). Levels of reflection in action research: An overview and an assessment tool. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.002

- Fathi, J., & Behzadpour, F. (2011). Beyond method: The raise of reflective teaching. International Journal of English Linguistics, 1(2), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v1n2p241

- Feeney, E. J. (2007). Quality feedback: The essential ingredient for teacher success, the clearing house. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues & Ideas, 80(4), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.80.4.191-198

- Finlay, L. (2008). Reflecting on ‘reflective practice’. PBPL, paper 52, The Open University.

- General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland. (2011). Teaching: The reflective profession. Albany House.

- Gosling, D.(2009). A new approach to peer review of teaching. SEDA paper 124, Chapter 1.

- Griffin, M. L. (2003). Using critical incidents to promote and assess reflective thinking in preservice teachers. Reflective Practice, 4(2), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940308274

- Gün, B. (2011). Quality self-reflection through reflection training. ELT Journal of Education, 65(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq040

- Hammersley‐Fletcher, L., & Orsmond, P. (2005). Reflecting on reflective practices within peer observation. Studies in Higher Education, 30(2), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500043358

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Hatzipanagos, S., & Lygo‐Baker, S. (2006). Teaching observations: Promoting development through critical reflection. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 30(4), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770600965425

- Hendry, G. D., Bell, A., & Thomson, K. (2014). Learning by observing a peer’s teaching situation. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2013.848806

- Jyrhama, R. (2001). What are the “right” questions and the “right” answers in teaching practice supervision? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Study Association on Teachers and Teaching, Faro, Portugal, September 21-25, 2001.

- Kuit, J. A., & Gill, R. (2001). Experiences of reflective teaching. Active Learning in Higher Education, 2(2), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787401002002004

- Lamb, P., Lane, K., & Aldous, D. (2012). Enhancing the spaces for reflection: A buddy peer- review process within physical education initial teacher education. European Physical Education Review, 19(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X12457293

- Lane, R., McMaster, H., Adnum, J., & Cavanagh, M. (2014). Quality reflective practice in teacher education: A journey towards shared understanding. Reflective Practice, 15(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900022

- Larrivee, B. (2004 June). Assessing teachers’ level of reflective practice as a tool for change. Paper presented at the Third International Conference on Reflective Practice, Gloucester, UK.

- Larrivee, B. (2008). Development of a tool to assess teachers’ level of reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 9(3), 341–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802207451

- Lin, Y. T., Wen, M. L., Jou, M., & Wu, D. W. (2014, March). A cloud-based learning environment for developing student reflection abilities. Computers in Human Behaviour, 32, 244–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.12.014

- Loughran, J. J. (2000, July). Effective Reflective practice, A paper presented at Making a difference through Reflective Practices: values and Actions Conference. University College of Worcester.

- Lyons, N. (1998). Reflection in teaching: Can it Be developmental? A portfolio perspective. Teacher Education Quarterly, ( Winter), 25(1), 115–128. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23478112

- McGarr, O., & McCormack, O. (2014). Reflecting to conform? Exploring Irish student teachers’ discourses in reflective practice. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(4), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2013.807489

- McGarr, O., McCormack, O., & Comerford, J. (2019). Peer-supported collaborative inquiry in teacher education: Exploring the influence of peer discussions on pre-service teachers’ levels of critical reflection. Irish Educational Studies, 38(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1576536

- Moon, J. A. (1999). Reflection in learning and professional development, theory and practice. Kogan Page.

- Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: Improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003786559

- Parsons, M., & Stephenson, M. (2005). Developing reflective practice in student teachers: Collaboration and critical partnerships. Teachers & Teaching, 11(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060042000337110

- Poom-Valickis, K., & Mathews, S. (2013). Reflecting others and own practice: An analysis of novice teachers’ reflection skills. Reflective Practice, 14(3), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.767237

- Quinton, S., & Smallbone, T. (2010). Feeding forward: Using feedback to promote student reflection and learning – a teaching model. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 47(1), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290903525911

- Reynolds, M. (1997). Towards a critical management pedagogy. In J. Burgoyne & M. Reynolds (Eds.), Management learning: Integrating perspectives in theory and practice (pp. 312–327). Sage.

- Reynolds, M., & Vince, R. (Eds). (2004). Organising reflection. Ashgate.

- Scheeler, M. C., Ruhl, K. L., & McAfee, J. K. (2004). Providing performance feedback to teachers: A review. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 27(4), 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/088840640402700407

- Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

- Shoffner, M. (2008). Informal reflection in pre-service teacher education. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 9(2), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802005392

- Smyth, J. (1989). A critical pedagogy of classroom practice. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 21(6), 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027890210601

- Van der Schaaf, M., Baartman, L., Prins, F., Oosterbaan, A., & Schaap, H. (2013). Feedback Dialogues That Stimulate Students’ Reflective Thinking. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(3), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.628693

- Weller, S. (2009). What does ‘peer’ mean in teaching observation for the professional development of higher education lecturers? International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 21(1), 25–35.

- Xie, Y., Ke, F., & Sharma, P. (2008). The effect of peer feedback for blogging on college students’ reflective learning processes. Science Direct, 11(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.11.001

- Xie, Y., Ke, F., & Sharma, P. (2010). The effects of peer interaction styles in team blogs on students’ cognitive thinking and blog participation. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 42(4), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.42.4.f

- Yee, B. C., Abdullah, T., & Nawi, A. M. (2022). Exploring preservice teachers’ reflective practice through an analysis of six-stage framework in reflective journals. Reflective Practice, 23(5), 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2022.2071246

- Yiend, J., Weller, S., & Kinchin, I. (2012). Peer observation of teaching: The interaction between peer review and developmental models of practice. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.726967

- Zowzdiak-Myers, P. (2012). The teacher’s reflective practice handbook:Becoming an extended professional through capturing evidence-informed practice. Routledge.