Abstract

Taking its cues from the conclusions of Edward Corp in The Stuarts in Italy, 1719–1766: A Royal Court in Permanent Exile, this article considers the evolution of the princely court held by the two final Stuart claimants, Charles Edward and Henry Benedict Stuart. It surveys the dénouement of this court from the deposed Catholic dynasty’s loss of de jure recognition of sovereignty in 1766 to the death of its last representative in 1807. By analysing the Stuarts’ interactions with the Papacy and European monarchies amid their ongoing struggle to uphold the appearance of royalty, it argues that the changing nature of their court emerged as a significant and distinctive nexus of cultural and symbolic meaning. The court of the exiled Stuarts from 1766 to 1807 emphasised the character, prerogatives and status of retreating Ancien Régime kingship in the decades preceding the French Revolution, during the years of its existence and in the Napoleonic era that followed.

After the exhibition La cour des Stuarts à Saint-Germain-en-Laye au temps de Louis XIV, organised by Edward Corp and staged in 1992 by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, a great interest developed in the roles the exiled Stuart courts and their Jacobites followers played in the shaping of early modern Europe.Footnote1 Since then, many studies have shown the forgotten relevance of the deposed Catholic Stuart dynasty and its adherents as cultural links between the British Isles and the Continent, as patrons of art and music at a transnational level, as privileged witnesses and participants of the phenomenon termed the Grand Tour and the final years of the Ancien Régime. The study of the Stuart courts in exile has been systematically addressed in chronological order by Corp in his works A Court in Exile: The Stuarts in France, 1689–1718 (2004); The Jacobites at Urbino: An Exiled Court in Transition (2009); and The Stuarts in Italy, 1719–1766: A Royal Court in Permanent Exile (2011).Footnote2 Two collections of essays, The Stuart Court in Exile and the Jacobites (1995) and The Stuart Court in Rome: The Legacy of Exile (2003), and many other works have further contextualised Corp’s focus on these courts.Footnote3

Nevertheless, adequate research has not covered the period after the death of King James III of England and VIII of Scotland –– as Jacobites and the European powers that acknowledged his rights named him.Footnote4 James’s enemies denounced him as the ‘Old Pretender’. Several biographical works have tried to portray this period while paying attention to his eldest son, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the ‘Young Pretender’. Then again, they usually emphasise his earlier years and underestimate the importance that the Prince’s court maintained in both cultural and symbolic terms. Even poorer are the studies concerning Charles’s younger brother, Prince Henry Benedict Stuart, called cardinal duke of York, whose ecclesiastical career did not prevent his claim nor completely extinguish the court established by his predecessors.

Therefore, this article serves as a coda to Corp’s magisterial three-volume study of the exiled Stuart courts from 1689 to 1766, which concluded with the cessation of the dynasty’s de jure recognition of sovereignty by its long-standing supporters. Corp’s research constituted a complete analysis of the royal court in exile, but he intentionally left 1766 to 1807 unstudied. Yet his doing so left unanswered the question of whether the princely court’s continuance under James’s sons, with the loss of its regal status, remained relevant and impactful. This study argues that aspects of the royal court endured in the subsequent princely one, primarily through the partial and intermittent survival of royal trappings, which gave this new entity an exceptional status among the milieu of Italian aristocratic households. In this way, the court of the last Stuart claimants remains of considerable historical and historiographical significance despite its steady decline. Hence, this research aims to help determine to what extent, from the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ to the French Revolution and beyond, the Stuart courts in exile were a political, cultural, religious and symbolic nexus throughout Europe, influencing the society around them and attracting substantial international interest.

The Struggle for Recognition

In late 1765, after an almost twenty-two-year absence from Italy, Prince Charles Edward Stuart began the process of returning to Rome to take control of the exiled court that had been in existence since the overthrow and flight of his grandfather, King James II of England and VII of Scotland, in the Revolution of 1688–89. Both the Prince’s grandfather and father had always been acknowledged by successive popes and, for a time, other European powers as the de jure monarchs of the three kingdoms, enabling each to hold a royal court for their respective lifetimes.Footnote5 Charles’s brother, Prince Henry Benedict Stuart, cardinal duke of York, had been pressing him for some time to rejoin the Stuart court and return to public life.Footnote6 Henry was likely worried that if his brother had not taken action, some would have cast doubt on the court’s survival if James had passed away. Realising his father did not have long to live, Charles agreed with the Cardinal Duke that he had to stabilise his political and social standing, prompting him to make an overture for recognition to Pope Clement XIII.Footnote7 The Pontiff did not commit to acknowledging the Prince as king but promised to receive him with all due honours.Footnote8 Charles soon afterwards received word that his ailing father’s death loomed ever closer, precipitating his homecoming. However, he took much time to prepare for the arduous journey via Paris from his long-term residence of Bouillon.Footnote9

James III died on 1 January 1766, the day after the Prince left the French capital for Rome.Footnote10 Cardinal York had been too grief-stricken to inform his brother of this news. It fell to the Scottish courtier Andrew Lumisden, James’s private secretary, to notify his new master –– now King Charles III to Jacobites –– of the aged claimant’s rather sudden demise and offer his condolences. He recommended that Charles return to Rome as soon as possible because the Holy See had not automatically recognised his accession, notwithstanding Clement XIII’s previous declarations that the Prince had understood as an assurance to confirm his ‘new rank’.Footnote11 Lumisden also advised Charles, on the counsel of Henry and ‘people (not Italians) of great distinction and weight’, that doing so would hasten the Pope’s acknowledgement of his sovereignty.Footnote12 He then stated, ‘May your Majesty long live, and soon enjoy your undoubted rights, and thereby render an infatuated people happy by the blessing of your reign!’.Footnote13

Charles did not reach the city of his birth until late January 1766, arriving there ‘with a great deal of troble [sic]’.Footnote14 Further trouble awaited the Prince on his return. He soon discovered that despite his pleas to Louis XV of France, Charles III of Spain and Ferdinand IV of Naples and III of Sicily for support, and though French, Spanish and Neapolitan ministers in Rome affirmed that it would be highly acceptable to their courts, the Pontiff refused to decide whether to recognise Charles by himself. Clement called a congregation of the Sacred College of Cardinals to aid him in judging its merit.Footnote15 Irrespective of this debate, Lumisden lamented that the congregation included the powerful Cardinal Alessandro Albani, whom the former defined as ‘the public minister of the [Holy Roman] Emperor [Joseph II], and the private but known minister and spy of the Duke of Hanover [George III]’.Footnote16 Albani, working in concert with Sir Horace Mann, the British diplomatic representative to the grand dukes of Tuscany in Florence and perennial secret agent, played a pivotal role in persuading the congregation to refuse to acknowledge any claim of Charles.Footnote17 Direct lobbying by the Stuarts’ supporters in Paris and Madrid achieved the Spanish king’s open criticism of the Holy See’s decision with the Papal Nuncio at his court. Still, it was futile as the Pope ignored his lamentation.Footnote18

At the same time, letters began arriving at the Palazzo del Re (‘the King’s Palace’) from Jacobites, expressing their sorrow at James’s passing and sending condolences to their new monarch as they pledged allegiance to him ().Footnote19 Requests for continued court patronage that his father had afforded loyal adherents also reached Charles during this transitional period from one Stuart claimant to another for the first time in almost sixty-five years.Footnote20 Such needs would be challenging to fulfil, owing to the Prince’s considerably more straitened financial resources. His calls for subsidies from France went unheard. The Spanish court could not answer his appeal because its state finances were dire. Shortly after promising some aid to the Stuarts, the treasury minister, Leopoldo de Gregorio y Masnata, marquess of Esquilache, was dismissed because of the riots his reforms were causing in Madrid.Footnote21

The question of Charles’s recognition sparked a complex decision-making process at the Papal court, revealing the issue’s political significance and sensitive nature. By 1766, it was apparent even in Rome that a Stuart restoration was no longer viable. This situation undermined the family’s political position and ability to maintain its royal status, which the Holy See questioned on James III’s death. Many factors influenced the Pope’s delay in resolving the matter. Clement, an elderly and frail man, was emotionally tied to the House of Stuart and a traditional view that saw the deposed dynasty deserving his political support. Regardless, he was well aware of the differing opinions within the Sacred College, leading him to break from the long-standing practice of autonomous papal judgment. Ultimately, the Pontiff chose and likely felt compelled to continue supporting the Stuarts economically. However, he accepted the prevailing view that doing so politically would be counterproductive to Catholic interests and the Church’s diplomatic affairs.Footnote22

Yet the Prince remained determined to obtain papal and broader recognition and soon left Rome, commencing a protracted protest against the decision of the Holy See. In what was to become a trend of several long, self-imposed periods of isolation, he removed himself from such vicissitudes, initially to Frascati and then to Albano. His obstinacy continued while enjoying the regal pleasures of life, such as hunting trips and musical evenings with the celebrated composer and cellist Giovanni Battista Costanzi.Footnote23 Despite this sojourn, Charles had no choice but to eventually return to the Palazzo del Re and confront the papal rejection first-hand in May 1767, when Clement XIII received him privately and remarked that he must relinquish his claim indefinitely.Footnote24 The Prince was, henceforth, forced to adapt to a different reality during this unprecedented transformation in papal relations with the exiled Stuart court. For instance, unlike his grandfather and father, who received recognition and benefaction from every reigning pope from 1688 to 1766, he had to obtain royal honours, wherever possible, only by requesting suppliantly.Footnote25

Papal Relations and Controversial Status

The French government withdrew its support for the Stuart court after the failed Jacobite rising of 1715–16 (termed the '15). As the Stuarts were thereafter wholly dependent on the Pope’s hospitality and generosity, the backing of the Holy See became increasingly important. The court was re-established at Avignon, then briefly at Pesaro, later at Urbino and finally at Rome.Footnote26 Much of the change process between the courts of Charles and his father was the differing degrees of political support experienced by each Stuart claimant. These differences were usually subject to broader external events and shifts in Jacobite fortunes. After 1766, it came mainly due to the Prince’s contrasting relationships with Popes Clement XIII, Clement XIV and Pius VI.Footnote27 The sharply dwindling reputation of the court in the eyes of the Papacy, as recounted by his brother Henry following Charles’s first papal audience, can be attributed to the elder prince’s ‘unabating stubbornness, indocility, and most singular way of thinking and arguing, which, indeed, passes anybodys [sic] comprehension’.Footnote28

These pontiffs’ dealings with Charles throughout his remaining years illustrate the court’s shift from being a political danger to a mere annoyance for an unwilling host. Clement XIII not only almost immediately rejected the Prince’s regal title of Charles III but swiftly expelled the English and Scots Colleges’ rectors and the Irish Dominican and Franciscan Orders’ abbots from Rome for acknowledging it against his directives. Similarly, Abbé Peter Grant, agent of the Scottish clergy in Rome, was reprimanded and had his pension from the Holy See withdrawn. The Pope then formally forbade all his subjects to address Charles with that designation or permit him honours of any kind.Footnote29 Clement also had the royal coat of arms of Great Britain removed from the façade of the Palazzo del Re at night, suspended the payment of the maintenance costs of the building and authorised the seizure of the Prince’s coach when the latter had ordered its adornment with the royal cypher ‘C.R.’ (‘Carolus Rex – King Charles’).Footnote30 This situation forced Charles to use incognito titles: the pseudonyms Baron Douglas or Baron Renfrew in Rome and, from 1770, also count of Albany ().Footnote31 This later title became his primary alias following his move to Florence with his wife, Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, in 1774 ().Footnote32

Figure 2 Hand-coloured Engraving of Charles Edward Stuart and Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, count and countess of Albany, after a medal by Alessio Giardoni, c.1770s–1800

(Royal Collection Trust)

Figure 3 Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, countess of Albany, incorporated within Charles Edward Stuart’s badge of the Order of the Thistle, possibly after a full-length miniature by Carlo Marsigli, 1774

(Royal Collection Trust)

The reign of Pope Clement XIV began apparently under the best auspices for the Stuarts, to the point that Domenico Corri, the entertainment director of the court, remembers this pontiff in his memoirs as ‘the friend of Prince Charles’.Footnote33 Clement granted the Prince some de facto honours. While asserting he could not officially reverse his predecessor’s decision, Clement invited Charles to rejoin Roman society and tolerated many cardinals and nobles calling him king publicly.Footnote34 The Prince hoped his marriage could be the occasion to formalise this change in relations with his papal benefactors. Charles charged Cardinal Mario Compagnoni Marefoschi, a supporter of his who held the Pope’s confidence, to convince Clement that the wedding and prospect of a Catholic heir obliged the Holy See to readdress its policy towards the Stuart court. Charles Fitz-James, duke of Fitz-James, the French cousin of the Stuarts, primarily devised the union with Louise. Fitz-James hoped to renew the alliance between the deposed dynasty and Versailles by asserting that the continuity of the direct Stuart line would be of long-term interest to the French.Footnote35 Yet Frank McLynn –– the Prince’s foremost biographer –– notes that Charles was ‘thunderstruck’ when Clement still refused to acknowledge him.Footnote36 The Stuart claimant again went through the motions of attempting to secure recognition as Charles III on the election of Pope Pius VI but to no avail.Footnote37

The exasperated Prince then commenced his voluntary exile in Florence, which lasted eleven years.Footnote38 In this period, it became evident that no Stuart expectations of an heir would ever transpire, and the marriage began to disintegrate. Louise soon after complained of severe maltreatment, resorting to building up a secret liaison with the Italian dramatist and poet Count Vittorio Alfieri, which ended with their flight together.Footnote39 The issued litigation is too long and complex to enter into detail here. Nevertheless, it came to a resolution only when Charles asked for mediation via Gustav III of Sweden, who visited the Stuart court during his Grand Tour en route to Rome to meet Pius VI. The King was doing so to improve his relationship with the Catholic Church as he promoted religious tolerance in his Protestant kingdom. Gustav offered the Prince symbolic help in the form of 4,000 riksdaler. He also persuaded Louise to revert to her husband the portion of the papal pension that she was enjoying in exchange for a formal separation, which Pius approved.Footnote40

Notwithstanding all setbacks, Charles continued to exert the royal prerogatives expected of a monarch. Most notable was his decree to legitimise his only surviving child, Charlotte Stuart, in 1784 and style her duchess of Albany ().Footnote41 Though the Prince legitimised his daughter and for some time cherished the notion of striking a medal to celebrate her as the last hope of the Jacobite cause, in the end, he never openly contested the succession rights of his brother.Footnote42 Considering Henry’s station as a Prince of the Church, this idea was quite an extraordinary step. However, as Charlotte later remarked, a British Act of Parliament would have been required to enable her succession.Footnote43 Nonetheless, Cardinal York was initially furious at her legitimisation, whose extent was ‘very much farther than has been the invariable custom in similar cases’.Footnote44

Figure 4 Charlotte Stuart, duchess of Albany, by Hugh Douglas Hamilton, c.1785/6

(Scottish National Portrait Gallery)

Consequently, the elder sibling reminded the younger of his regal authority, stating that Charlotte ‘is Royal Highness for you and everywhere’.Footnote45 Louis XVI of France subtly ratified Charlotte’s legitimisation, never referring to her as duchess or ‘Her Royal Highness’ but instead as Lady Charlotte Stuart d’Albany. In Pisa, Maria Luisa of Spain, grand duchess of Tuscany, and her sister-in-law and guest, Maria Carolina of Austria, queen of Naples and Sicily, warmly received Charlotte after being lobbied by Charles’s friends in the Florentine aristocracy.Footnote46 Crucially, Pius VI acknowledged Charlotte’s ducal title, leading to a reconciliation between the still self-exiled Prince and the Holy See.Footnote47

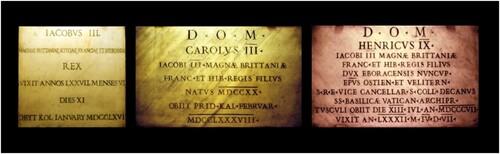

On Charles’s return to Rome in late 1785, the Pontiff had the former’s residence at Albano restored and furnished at the expense of the Camera Apostolica. Pius also permitted the Prince to use the royal arms of Great Britain publicly and ride in coaches adorned with the royal cypher. The Pontiff likewise granted him a tribune of honour for all public celebrations.Footnote48 These indulgences showed courtesy to Charles, a frail, rapidly deteriorating man of advancing years, while not recognising his regal title. He will likely have viewed them as vindicating his claim to de jure sovereignty. At the Prince’s demise on 30 January 1788, and despite several pleas from his brother and successor to the Stuart claim, Pius VI still reluctantly refused to acknowledge Charles III, even for his funeral mass. Henry –– now King Henry IX of England and I of Scotland to Jacobites –– therefore removed his brother’s body to Frascati, where, as its bishop, the unrecognised ‘Cardinal King’ ‘in partibus infidelium’ could preside over the service and interment at his discretion.Footnote49 Charles lay in state with the royal coat of arms displayed around the coffin, the Orders of the Garter and Thistle stars on his breast and a crown and sceptre to uphold the pretence of majesty in death.Footnote50 Still, on the monuments erected to the Prince and his family in Frascati Cathedral and Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome (the latter contains the most well-known one by the celebrated neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova), he is remembered as a ‘son of James III’.Footnote51

The broader effects of this gradual decrease in royal honours and privileges bestowed on Charles and his court from the ones accumulated by his father are most visible in the arena of Roman high society. The plight of the exiled Stuarts had long been venerated with music and celebrated in Rome, stretching back to the Revolution. When the court arrived there in 1719, James III, a keen lover of the opera, was given the best triple box at the Teatro Aliberti, the finest theatre in the city, emphasising his birthright as de jure king of the three kingdoms.Footnote52 Many musical and artistic works were dedicated to him during his exile in several host states –– attributable to the widespread political support and subsidies James received in recognition of his claim.Footnote53 Like his father, Charles often frequented operatic concerts but received no such acknowledgement. Long forgotten has been the role of the deposed dynasty as patrons of Italian music. Yet recent studies examining the court of James reveal a strong vein of Stuart patronage in Roman operatic society, which continued under his sons.Footnote54 For instance, the family contributed to launching the careers of young artists destined for fame like Domenico Corri and Maria Rosa Coccia, the latter a wunderkind who was grateful enough to dedicate compositions to ‘the Majesty of Charles III’.Footnote55 However, unlike his father, the Prince received almost no comparable musical and artistic dedication.

Charles eventually began to receive the above-mentioned papal dispensations, including the use of the royal arms, coach and cypher, and tribune of honour, given the venerable status of his family among the Catholic powers. Despite this standing, it fell to the Stuart claimant to promote his sovereignty through material and tangible mediums in the interim. He had himself portrayed by various artists in different formats. His official portrait was painted in 1770 by the renowned Laurent Pécheux, and at least four versions of it have survived ().Footnote56 It shows Charles III resplendent in armour, pointing to an ongoing battle on land and sea, with a crown, orb and sceptre signifying his birthright to majesty.Footnote57 In late 1777, Charles purchased the Palazzo Guadagni in Florence. Visitors can still see his painted royal coat of arms in the vestibule of the self-styled king’s residence. A Latin inscription in the lunette above the arms reads ‘CAROLUS. III. NAT. 1720. MAG. BRITANIAE [sic] ET HIB. REX FID. DEFEN. AN. 1766’ (‘Charles III, born 1720, King of Great Britain and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, in the year 1766’). Below is the royal motto ‘Dieu et mon droit’ (‘God and my right’) ().Footnote58 The Prince also had a bronze weathervane installed on the roof bearing the information ‘C.R. 1777’, denoting the self-appointed seat of his regal court.Footnote59 This palace was Charles’s favourite abode, and he had risked his financial situation by purchasing it for 21,000 scudi. He also invested considerable money in buying annexe buildings (mainly occupied by court servants) and renovating and improving his new home.Footnote60 In 1786, following his return to Rome and Pius VI’s relaxation concerning the Prince’s status as head of the Stuart court, the family retired to Albano. While there, Charles did not squander the chance to accentuate his royalty by touching people afflicted with the ‘King’s Evil’ (scrofula), perpetuating a tradition abandoned by the Hanoverians but preserved by the exiled Stuarts (A and B).Footnote61

Figure 5 Miniature of Charles Edward Stuart, styled as King Charles III, after the portrait by Laurent Pécheux, c.1770

(Tansey Collection)

These papal relations and societal fluxes demonstrate the differences between how James and Charles and their courts were regarded, depending on the political backing that they experienced as the Stuart claimants’ status swithered according to the broader outcomes of their particular epochs. The paradoxical significance of this pendulum swing is the critical distinction that James continually received royal honours and patronage via the formal conduit of de jure recognition. In contrast, his son never obtained the latter. Charles only received a modicum of royal trappings when the Papacy considered the Jacobite threat wholly extinguished from the mid-1780s and deemed the Prince and his court harmless and inconsequential. It coincided with the British government’s restoration of several forfeited Jacobite estates following the passage of the Disannexing Act of 1784.Footnote62 Indeed, Corp has already underlined that ‘the Stuart court in exile’ was progressively transformed into ‘the court of the exiled Stuarts’.Footnote63 Though not recognised as king nor granted official royal honours by any foreign power as his regal pretence endured, the residence of Charles remained, and one cannot consider it anything but a court, even if a crucial split had occurred. For the first time since 1689, an internal perpetuation of a royal Stuart court in exile and the external denunciation of this prerogative incurred a permanent rift between the Prince and his family’s long-standing papal benefactors until the extinction of the dynasty in the direct male line in 1807.

An Italian Court

As a result of this fissure, an inexorable transition period commenced. The court of Charles differed significantly from the courts of his grandfather and father. James II and VII had been provided sanctuary at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in his cousin Louis XIV of France’s second royal palace. This kingly regard garnered what Eveline Cruickshanks and Edward Corp call ‘one of the very finest of the French royal châteaux’, wherein the deposed monarch established a fully-fledged regal court in exile encompassing around 1,000 servants and a substantial number of British and Irish courtiers.Footnote64 The King’s son and namesake, James III, inherited this court. It existed in various forms until the gradually diminished court of the latter arrived in Rome –– though it still retained considerable prestige throughout Europe. Comparisons can thus be more easily made with the court led by Charles’s father, as it was established (permanently) in the Palazzo del Re.Footnote65

The courts of James and Charles experienced phases of improvement and decline based on the ever-changing favour or disfavour that their allies afforded the Jacobite cause as its standing ebbed and flowed and its fate hung in the balance. The fiscal and domestic stability of the deposed dynasty also influenced these bonds and, at times, interdependence. For example, the volatile relations between James and his queen consort, Maria Clementina Sobieska, and between Charles and Louise exemplify these peaks and troughs in support. When these couples were in harmony, their courts attracted more generous endorsement and aid, and the opposite happened when the relationships broke down. Even so, the two periods were markedly different when accounting for the rapport and recognition James and his court continued to enjoy under the Holy See, especially from 1730 onwards, following the collapse of his marriage, compared with Charles’s further fall from grace from the mid-1770s to the mid-1780s.Footnote66

The evidence suggests that this trend continued in the Prince’s court retinue, which never knew a splendour equal to that enjoyed by his father during its halcyon days, that is, the years between marriage and his children reaching adulthood (1719–43). At its zenith, the court of James counted wage-earners at between sixty-five and ninety persons, with the number of exiles whom he continually subsidised oscillating between a dozen and twenty. About seventy of these approximately 100 people were of British and Irish origin.Footnote67 At its apex, the court of Charles counted at least seventy-one wage-earners plus nine higher-ranking courtiers either receiving pensions or serving out of loyalty. Conversely, no more than ten at a time were British or Irish.Footnote68 Yet this situation improved compared to James’s declining phase; in the early 1760s, he had seven British courtiers and around forty servants.Footnote69

Besides, from the 1720s to the 1740s, the Stuart family encompassed the King, Queen and two princes, requiring a more extensive retinue. However, if we count Charles’s retinue as a single entity alongside that of Henry at any time throughout the former’s ‘reign’ — essentially a combined court incorporating the servants and salaried workers of his younger brother who were obliged to acknowledge the Prince as king — the numbers would have doubled. It would have exceeded 150 people, albeit with a much smaller British and Irish contingent than his father’s court.Footnote70 The two brothers’ households effectively became one entity on a fiscal level. The papal pension of 10,000 scudi that Charles enjoyed relied on the goodwill of his brother to redistribute it back to him.Footnote71 On the death of James, the Holy See had transferred the King’s pension to Henry. The Cardinal Duke decided to revert it to his brother, thereby making the Prince’s return more acceptable to the Pope, who, in this manner, would not have been forced to decide whether or not to give him a second pension. The dependence of the elder sibling on the younger severely strained the brothers’ relationship at times. For instance, around 1781, Cardinal York stated, ‘I am annoyed by taking note that the King my brother continues tormenting me because of his supposed poverty, when even if it were true it would be his guilt alone. He does not want to understand that the ten thousand [scudi] are mine and that I cannot give more in the current circumstances’.Footnote72

Still, in some phases, when interactions between the brothers were civil, both attended and hosted with such assiduity as to give the impression of a single court. They rented or briefly acquired several sumptuous palaces and villas in Rome, Florence and the Latium and Tuscan countryside to entertain guests and receive distinguished visitors.Footnote73 Their attention to always choosing residences ‘fit for any Soverain’ with spaces large enough to host social events adequate to their pretences was a symptom of their characters. It ostensibly reflected the court they wished to present.Footnote74 There are likewise numerous cases of individuals who, for a time, served the Stuart princes simultaneously; the musician Costanzi and the treasurer Giuseppe Cantini are two examples. At various points, it was not just the retinues of the two brothers that we can include but also that of Louise, who, after leaving her husband, held court in the Palazzo della Cancellaria at Henry’s expense for some time. Not only was Louise hosted by the Cardinal Duke at the Cancellaria, but the latter had his treasurer, Cantini, and his friend, Giorgio Maria Lascaris, patriarch of Jerusalem (a Venetian prelate whose career Peter Pininski has shown as having been closely tied to the exiled Stuarts’ patronage) attend her.Footnote75 Henry also deducted 4,000 scudi from Charles’s pension of 10,000 to the advantage of his brother’s wife and the continued promotion of her court.Footnote76 So, in some ways, we can speak of a single Stuart court composed of different households between 1766 and 1788.

The ‘Court of the Pretender’

The Prince’s ‘reign’ encompassed some of the darkest phases of his life, perhaps leaving the most significant trace and influencing common perceptions of this conclusive period of Stuart exile. Murray Pittock has characterised Charles’s reputational descent as ‘the long decline’, which stretched back to and contrasted, unavoidably, with the Jacobite rising of 1745–46 (termed the '45), the so-called ‘Year of the Prince’, known by Gaelic-speaking Jacobites as ‘Bliadhna a’ Phrionnsa’.Footnote77 In most biographical accounts, we see a chronicle of an unhealthy individual, with a squalid social life, consumed and semi-destroyed by alcohol, ostracised by the local nobility and despised by foreigners, who appeared in public only to confirm his degradation.Footnote78 For example, even in the late twentieth century, Christopher Hibbert, in his analysis of the Grand Tour, disparages the Prince as prone to being seen in the 1770s slumped in the corner of his box in a melancholic, drunken sleep during Florentine opera performances.Footnote79 There is no doubt some truth to this general portrayal, though Whig propaganda and prejudicial reports by characters like Horace Mann have influenced it.Footnote80 In his last years, all contemporary accounts evinced that Charles had entered a period of intensifying dotage and became so weakened that he spent most of his time, as Giuseppe Gorani noted, ‘sleeping on a sofa, or stroking a little dog that never left him’.Footnote81

Yet this ‘image’ does not do justice to the history of the man and his court. For instance, not much earlier, Louis Dutens stated that the Prince ‘spoke several languages well, and seemed to be extremely well acquainted with the political interests of the Courts of Europe’.Footnote82 Karl Victor von Bonstetten did not hesitate to define his household as ‘une jolie miniature de cour’.Footnote83 Notably, Charles’s home remained constantly open to the Italian aristocracy and unprejudiced British and Irish travellers on the Continent.Footnote84 Even royalty did not spurn such hospitality. The Prince counted among his guests on different occasions Gustav III and his brother, Prince Frederick Adolf, duke of Östergötland, Peter von Biron, the last sovereign duke of Courland and Semigallia, Prince Stanisław Poniatowski, nephew of the last king of Poland, and Abbé Louis Aimé de Bourbon, a legitimised son of Louis XV.Footnote85

Over time, as Jacobitism eroded into political oblivion, the diminutive court of Charles became something of an obligatory spectacle, an expectation that to spy on him at least for a moment at the opera or when walking the streets of Rome or Florence marked an ‘official stage’ of the Grand Tour.Footnote86 The ‘Court of the Pretender’ thus became a landmark of cultural and political significance. Many British and Irish travellers felt they had to return home with an anecdote about meeting the Prince, his wife or daughter while visiting their court. As an anonymous traveller recounted in 1797,

there were few [British and Irish travellers] who had any scruples about partaking of the amusements of a house whose master had become an object of compassion rather than jealousy, whose birth and misfortunes named him after a kind of melancholy respect, and whose desires and efforts to disturb the peace of Great Britain, in pursuit of what he considered his birthright, had long been impeded, and were rightly regarded as forever frustrated.Footnote87

The Last Stuart

However, the death of Charles did not mark the end of the existence of this court. Even though the Prince was only four years older than Henry, there was considerable probability and expectation until the mid-1770s that the former would sire a legitimate heir. Yet Cardinal York seemed confident he would succeed his elder brother sooner or later. As will be seen, Henry had been worried about his succession since his father died in 1766, if not earlier. Between 1766 and 1767, there are two clear indications of this concern. Firstly, the Cardinal Duke did not encourage his brother to strike any accession medals; instead, he had one of his own made in 1766 by Filippo Cropanese.Footnote90 It suggests he was more interested in asserting his rights than his brother’s.Footnote91 Secondly, Cardinal York continued the allowance that his father had given to Clementina Walkinshaw, the former mistress of Charles, but on condition that she signed a document swearing they had never been married.Footnote92 Doing so protected the family from scandals and allowed his brother to marry without such problems. It also ensured that Charlotte, the daughter of Charles and Clementina, would never undermine his succession when the time came. Following the legitimisation of Charlotte by her father in 1784, Henry showed his concern with a public protest regarding his brother’s bestowal of the dukedom of Albany to her, which he believed was his by right. Cardinal York highlighted the unprecedented nature of this situation, arguing that it was wrong for the Prince to recognise Charlotte

as of the stem of the royal house, by granting her titles which would be most justly contested if he [Charles] were in actual possession of his lawful right. Nor in that case would his royal brother, according to the law of the Kingdom, have the faculty thus to habilitate thus a natural child, and place her in the succession to the throne.Footnote93

Notably, Henry did not join the Sacred College of Cardinals out of mere interest but because of the pious attitude he inherited from his parents ().Footnote95 His piety had always been evident from a young age.Footnote96 Therefore, his view of the Jacobite succession differed from that of his brother. Cardinal York emphasised this point in a memorial to Clement XIII not long before James III’s death.Footnote97 The day after the King died, the Cardinal Duke stated in a letter to the Pontiff, ‘Here, Holy Father in your arms you have two orphaned Princes, sole Scions of the Royal House of Stuart, which had been most unfortunate in everything except for the great merit it enjoys of having the chance at the end of the Last Century to sacrifice three Kingdoms for Our Most Holy Catholic Faith’.Footnote98 The exiled Stuarts could thus be considered ‘martyrs for the faith’.Footnote99 The fact that Charles was not as committed on the religious front tormented Henry constantly. The latter had repeatedly done his best to rid the court of Protestant Jacobites and reconcile his brother with the Pope, even if that meant somewhat accepting the new papal policy of no longer recognising the Stuart claim.Footnote100 So, from a particular perspective, Cardinal York had developed a sense of foreboding that he would one day be the final legitimate Catholic claimant to the throne, and he was satisfied with it.Footnote101 Henry was not interested in being a de facto ruler or a de jure king but instead morally entitled to the throne from a Catholic standpoint, and he clearly stated this message on his medals. ‘Non desideriis hominum sed voluntate Dei’: the Cardinal Duke did not care about what people thought or did with his titles; only the will of God mattered to him.Footnote102 He was the last of the direct Stuart line and king, in his view, by divine right, who cared only about adhering to his role as a ‘martyr for the faith’, having openly chosen the priesthood over illusory chances of restoration.

Figure 8 Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal York, by Hugh Douglas Hamilton, after c.1786

(Blairs Museum)

This stance determined the nature of his court, which changed from a household of Jacobite exiles to one of priests and men functional to Henry’s role as a cardinal. The ‘Cardinal King’ accordingly transferred part of his religious vocation to the court overall. Such a gradual transformation had already begun while his father still lived. This shift partly occurred because finding potential recruits for the court from the British and Irish religious institutions in Rome was more straightforward than having other exiles come there. Given that motivation, the Cardinal Duke put a pious focus and influence on the court’s makeup. For example, he obtained extraordinary authorisation from the Pope to employ a priest as his maestro di camera, an otherwise not at all spiritual role. His first maestro di camera was the Irishman Father Leigh, a Jesuit, who was already a favourite of his father among the British and Irish priests of the city.Footnote103 Nevertheless, Leigh was old, and Cardinal York preferred an Italian priest closer to his age, Giovanni Lercari. This decision became a cause for quarrelling with his father, who had this man sent away.Footnote104

Over the long term, the son increasingly determined which people were permitted to frequent the court. Consequently, James III replaced his favourite and chief adviser, Captain Henry Fitzmaurice, with Lascaris, who was close to the Cardinal Duke. Fitzmaurice lamented that the King no longer cared about his opinions as Lascaris became James’s sole confidant.Footnote105 By proceeding this way, decades later, during Henry’s self-styled ‘reign’, the court of the final Stuart claimant almost completely emptied itself of British and Irish members. The last of them was Abbé James Waters, scion of a long-standing Jacobite family serving the Stuarts as their bankers and agents in Paris from at least 1735.Footnote106 However, Waters was a pious man and procurator of the Benedictines in Rome.Footnote107 The household of the ‘Cardinal King’ thus progressively became more and more typical of any Italian cardinal-bishop.

The court of Henry had only a trace of continuity with those of the preceding Stuart claimants, with doubt, for instance, remaining about the liveries that his household servants wore. On Charles’s demise, Charlotte dressed her servants with the liveries of the House of Stuart, which her uncle already used and no longer the royal ones used by her father.Footnote108 Furthermore, by abandoning the long-held seats of the Stuart court, the Palazzo del Re in Rome and the Palazzo Apostolico in Albano, now devoid of any British and Irish subjects, one could think the manifestation of the Stuarts’ royal pretensions –– expressed through their court –– had ended with the death of Charles. On the contrary, Henry took different steps to mark his self-proclaimed accession and now sovereign status.

Firstly, in the vein of his predecessors, he instructed his household to no longer address him as ‘Your Royal Highness’ but ‘Your Majesty’.Footnote109 The diocesan court complied. Yet the walls of his residence were not the limits of his pretended royalty as had often been the case for his brother. The Cardinal Duke had full spiritual and temporal power over his diocese as a bishop in a theocratic state. At the news of Charles’s expiration, he had the bells of Frascati sound a death knell, and the carnival feasts suppressed. As noted, Henry celebrated the funeral by himself to afford his brother royal honours that would not have been possible in Rome and to underline his new regal status before his flock. He also had the chancellor of the diocese open and read his protest of succession in the presence of all the civil and religious authorities of Frascati and hence began to sign his orders to them ‘Enrico R. Card.e Vescovo’ (‘King Henry, Cardinal Bishop’) or ‘Dux Eboracensis Nuncupatus’ (‘called Duke of York’), signifying this latter title was now only an alias as much as count of Albany had been for his brother. Secondly, in the following days, Cardinal York decreed that all his coats of arms displayed in the town were to be changed, removing the crescent of the younger son and replacing the ducal coronet with the royal crown.Footnote110 Correspondingly, on his coaches, he had the royal crown painted under the cardinal’s hat (galero).Footnote111 The diocese had to know that a king now ruled it. Another exterior sign of his newly acquired kingship was recommencing the thaumaturgical touch possessed by rightful kings alone via a direct conduit with God. Touching for the ‘King’s Evil’, a religious ceremony, was taken seriously by Henry, who performed it regularly, observing the family tradition sustained by his brother, as evidenced in the Cardinal Duke’s diaries. He also commenced a considerable production of touch-pieces, which continued until at least September 1803, with the jettons minted in the order of the hundreds (A and B).Footnote112

Outwith the diocese, only a few Jacobite ‘survivors’ acknowledged his royal title and wrote to him regarding condolences and seasonal greetings or asked for patronage, mainly of a religious nature. The clearest example was Denis O’Dea, a late ‘Wild Goose’ raised to the rank of brigadier in the Neapolitan army. He wrote various times, including once to commiserate for the loss of the duchess of Albany in 1789 and to ask Henry to protect his daughter and other relations as they conducted their education in religious congregations in Rome.Footnote113 However, it was not solely O’Dea who did so, as traces of correspondences with families of time-honoured Jacobite tradition from this later period have survived scattered in the archives, especially in the Stuart Papers.Footnote114 The ‘Cardinal King’ remained a quasi-patron for his Catholic subjects.Footnote115 This circumstance was due more to his religious position than his royal claim, but it was the primary way he could still have an active role concerning such sympathisers.

Conversely, in 1788, the Scottish Episcopal Church had finally accepted the Hanoverian succession, finding it impossible to go on praying and recognising a king who was now a Catholic prelate.Footnote116 Nevertheless, nothing changed for the few living individuals who sacrificed everything for the Jacobite cause. They continued to acknowledge the new Stuart claimant –– albeit one with no real prospect of restoration. Some letters between veterans of the '45 evidence this seismic shift in Episcopalian policy. For example, after corresponding with Cardinal York, Milord Henry Nairne described it to Laurence Oliphant the Younger of Gask as ‘ridiculous and unnecessary’, noting he was glad that among them lingered a non-juring Episcopalian reverend, John Maitland, who ‘was not in the number of the apostates’.Footnote117

Papal and Royal Relations

Immediately at his accession, Henry hurriedly forwarded a copy of his 1784 protest of succession to Pius VI. The Cardinal Secretary of State, Ignazio Boncompagni Ludovisi, answered this formal request on 1 February 1788, remarking that the protest was ‘moderate and prudent, and we have therefore nothing to say against it’.Footnote118 Condolences for Charles and a papal benediction accompanied the letter, which the Cardinal Duke, evidently satisfied, had transcribed in the diary kept by his secretary Angelo Cesarini.Footnote119 It was not a formal recognition of his titles nor a rejection of them. The Pope could not officially acknowledge the ‘Cardinal Kingship’ but did not deny Henry’s birthright as long as the latter asserted it with the prudence of bearing no political consequence, like Charles’s final years. Considering his long history of failure regarding his previous protests, the last Stuart probably viewed such an answer as a victory.

The next step was to strike accession medals, which Cardinal York gave to the Pontiff, the Sacred College and the Roman aristocracy.Footnote120 These medals, cast in gold, silver and bronze, and a new and embellished version of those commissioned in 1766, now openly named him Henry IX.Footnote121 Though showing less prudence than the protest, these medals were innocuous and inconsequential. Henry used them to symbolise the continuous reassertion of his self-styled status as king, ‘voluntate dei’. He also often gave them to any friend or visitor at his court as a souvenir for the remainder of their life. Among those who received them, we can count Clementina Walkinshaw, the Traquair family, Thomas Coutts, the royal banker (who would later give his medal to George III), Valentine Lawless, Baron Cloncurry, and even Prince Augustus Frederick, duke of Sussex (sixth son of George III).Footnote122 Some bills of the engraver Gioacchino Hamerani have survived in the Stuart Papers, testifying to a considerable mintage.Footnote123

The other step marking Henry’s accession was giving notice to the Catholic courts of Europe with which the Stuarts had kept contact during their exile. Most notably, Ferdinand IV and III answered with his condolences on the death of Charles, calling the Cardinal Duke ‘my brother and cousin’. It was a phrase that the King and his Queen reiterated in all their correspondence with the last Stuart. The appellation of ‘brother’ implied recognition of his sovereign status; otherwise, the term ‘cousin’ was only reserved for cardinals, princes and other stations beneath the rank of royalty.Footnote124 Cardinal York valued such regard highly. Yet, in contrast, the parvenu emperor of the French, Napoleon I, omitted it when inviting Henry to his coronation in 1804. This act showed a lack of tactfulness that did not go unnoticed by the elderly clergyman, whose pretence of royalty endured by this point only via courteous addresses.Footnote125

When the impact of the French Revolution reached the Papal States, inducing the Cardinal Duke and most of his fellow Princes of the Church to flee, the Neapolitan monarchs did not match their previous formal kindnesses with any tangible brotherly aid. Henry stayed ten months in Naples, but when the royal family abandoned the capital to the advancing French armies, embarking for Sicily, he had to find a ship independently and at his own expense. Also, on reaching Palermo, the final Stuart claimant had to persist with his rapidly diminishing resources, relying on mutual and reciprocal help from Cardinals Pignatelli, Doria and Braschi. He had to renounce much of his apparatus throughout this long period as a fugitive, eventually selling all the silverware he could to subsidise the reduced household, which followed its master and remained in his service at this unpredictable time.Footnote126

In this desperate phase, Henry stubbornly fought against all odds to preside over a new conclave, which the scattered cardinals felt could be required if the aged and fragile Pius VI died in French captivity. In the absence of the Vatican, the Sacred College decided that as many of its number who could do so should assemble in Venice, where they hoped to gather under the protection of Holy Roman Emperor Francis II. Pre-empting Pius’s sudden demise, Cardinal York hired a Greek merchant vessel in February 1799, safely transporting him and his companions, Cardinals Pignatelli and Braschi, to their Adriatic destination. Though landing in poverty, such intuitions proved accurate as the Pope died at Valence in August of that year. The resultant Venetian conclave concluded in March 1800 when a new pontiff, Pope Pius VII, was elected. During this interlude, the Cardinal Duke received unexpected financial aid from George III.Footnote127 In truth, it was the answer to a plea sent by a fellow cardinal, Stefano Borgia, to the King through the British diplomat Sir John Coxe Hippisley, who had already been a sympathetic guest of Henry’s little court some years before.Footnote128 This generosity certainly had many reasons behind it. One, above all, implicit but apparent, was the need for the ruling monarch to defend a man of royal blood and the senior Catholic Stuart line debarred from the British Protestant succession via the English Act of Settlement of 1701 from utter humiliation. It was an act that cost the long-established House of Hanover very little in the early nineteenth century but won them notable public approval.Footnote129

After two years of exile, the Cardinal Duke enjoyed his own again with the restoration of his episcopal seat. Regaining his position and, partly, his wealth, he immediately restored his residence and household to their former glories.Footnote130 A guest of Henry, Lord Cloncurry, remembered: ‘he was waited upon with all suitable ceremony, and his equipages were numerous and splendid.’Footnote131 Nonetheless, the revolutionary experience, adding to the lifelong frustration of the claims maintained by his family, may have caused some thoughts about the vanity of temporal royal trappings, which he and his brother had previously valued so much. Cardinal York entered this period in friendly relations with Charles Emmanuel IV of Savoy, king of Sardinia, who had been wandering through Italy since the French occupation of Piedmont. Charles Emmanuel had lost his beloved wife and queen consort, Marie Clotilde of France, in March 1802 and, in June, had spontaneously abdicated the Sardinian throne in favour of his younger brother, Victor Emmanuel I, to choose a more spiritual life.Footnote132 This selfless and pious example was likely meaningful to the Cardinal Duke. Significantly, in October of that year, Pius VII visited Henry in Frascati and repeatedly offered him to sit at his side –– an honour fit for a sovereign –– but the latter firmly declined.Footnote133 Also, a guest of this same period noted how Cardinal York had his table magnificently set with the finest china and silverware yet always used only common earthenware for himself.Footnote134

After Henry died on 13 July 1807, he received the stately funeral necessary for the Vice-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Catholic Church and Dean of the Sacred College of Cardinals. Still, the last rites showed no sign of royalty.Footnote135 At the same time, Charles, who had remained buried in Frascati Cathedral for almost twenty years, was reinterred in the vaults of Saint Peter’s Basilica alongside his father and brother. Situated in a place of honour among many popes, Charles and Henry were, in the end, afforded the royal titles denied to them in life. Small headstones featuring their regnal ordinals were erected in the secluded Vatican grottoes, marking the final resting places of James III, Charles III and Henry IX ().Footnote136 Charles’s long struggle for the Papacy to recognise him as the third three-kingdom monarch of his name had taken over forty years. In 1819, Pius VII had the cenotaph by Canova commemorating the three final Stuart claimants placed prominently in the basilica. Nevertheless, this monument only partially fulfilled such acknowledgement because it publicly remembers both brothers by their baptismal names and as ‘sons of James III’.Footnote137 These final honours attributed post-mortem to the Stuart family demonstrate the importance of politics long outweighing the ideological and religious principles that the Holy See felt constituted the birthrights of the deposed dynasty. However, they also allude to its view regarding the legitimate existence of the post-1766 court, above all with the private headstone inscriptions.

Conclusion

For their over-a-century-long exile, the inalienable status of Ancien Régime royalty protected the Stuart claimants. When such status ceased in an acknowledged de jure capacity, a certain amount of regal recognition survived, including that from their enemies, but only via diplomatic courtesy. Though impoverished and without previous political influence, the court maintained an exceptional status among the Italian aristocracy and enjoyed privileged relationships with the Papacy and the Bourbon monarchies. Notwithstanding the considerable vicissitudes experienced by the Stuarts, the post-1766 court remained esteemed, economically supported and shielded in numerous ways because their royal blood made them, to some degree, untouchable. Other monarchs could not expose even a deposed royal family to abject humiliation, and on entering the period of the French Revolution, this protection became even more apparent in how the ancient European royal houses treated the final Stuart claimant. This exceptional status discussed herein was reflected in a broad range of sectors during the life of this court, which requires further study in future research.

As stated, Edward Corp has argued that ‘the Stuart court in exile’ was gradually transformed into ‘the court of the exiled Stuarts’. Following an initial survey on the protraction of this court after the death of James III in 1766, it is evident and reasoned in this study that it metamorphosed from a royal court to a princely one and remained so until the extinction of the Stuart dynasty in the direct male line. From one Stuart claimant to the next, the court’s prosperity, influence and prospects changed. While James endeavoured to be restored de facto, Charles aimed only to achieve the de jure recognition afforded to his grandfather and father. Henry instead focused on defending his nominal rights as the last claimant in the Catholic line of succession. Though the post-1766 court was sometimes peripatetic and fragmented, the Holy See and several long-standing Jacobite-supporting European courts acknowledged its survival and respected its position. Such backing allowed it to maintain a perpetual pretence of royalty until 1807.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stefano Baccolo

Stefano Baccolo

Stefano Baccolo is an independent researcher of the early modern period. His theses to complete a bachelor’s degree and two master’s degrees at the Universities of Pavia and Pisa examined the mythification of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, the court of Charles Edward Stuart in exile in Italy and James Steuart’s Principles of Political Economy. He is also a member of the 1745 Association, for which he has organised tours in Italy to places connected with the Stuarts’ exile and regularly publishes in its journal, The Jacobite. A forthcoming publication includes Stefano Baccolo, ‘Sir Carlo Steuart, the last Jacobite in Italy’, The Stewarts, 37:1 (2024).

Calum E. Cunningham

Calum E. Cunningham

Calum E. Cunningham completed his PhD at the University of Stirling with a thesis entitled ‘Lawful Sovereignty: The Political Criminalisation and Decriminalisation of Jacobitism, 1688–1788’. He continues studying Jacobitism’s social, political and legal aspects. A forthcoming publication includes Calum E. Cunningham, ‘Jacobitism, High Treason, and the “Scottish Problem”: the evolution of post-Union treason legislation in Scotland, 1708-48’, in Darren S. Layne and Kieran German (eds), Cultures of Scottish Jacobitism: Identities, Memories, and Materialities, 1688–1788 (Manchester, 2025).

Notes

1 This article is dedicated to Professor Edward Corp, without whose research the authors could not have realised it. Unless otherwise stated as cited in Corp’s analyses, the authors have located all sources utilised in this study and referenced extensive material from the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle by gracious permission of His Majesty King Charles III.

2 Edward Corp, A Court in Exile: The Stuarts in France, 1689–1718 (Cambridge, 2004); The Jacobites at Urbino: An Exiled Court in Transition (Basingstoke, 2009); The Stuarts in Italy, 1719–1766: A Royal Court in Permanent Exile (Cambridge, 2011).

3 See Eveline Cruickshanks and Edward Corp (eds), The Stuart Court in Exile and the Jacobites (London and Rio Grande, OH, 1995); Edward Corp (ed.), The Stuart Court in Rome: The Legacy of Exile (Aldershot and Burlington, VT, 2003).

4 James was only referred to by his English regnal ordinal on the Continent as James III. The authors will adhere to that Continental convention herein. The King was also considered James III of Ireland but never proclaimed in that kingdom during the Jacobite risings fought in his name.

5 Corp, Stuarts in France, pp. 59-60, 160-2.

6 The Royal Archives at Windsor, Stuart Papers [hereafter RA, SP] 429/99, Prince Henry to Prince Charles, Frascati, 10 September 1765; RA, SP 429/132, Prince Henry to Prince Charles, Frascati, 24 September 1765.

7 The National Archives at Kew, State Papers [hereafter NA, SP] 98/71/fol. 37, ‘Copy of a letter from Prince Charles to Prince Henry’, [Bouillon], 3 October 1765; RA, SP 429/159, Prince Charles to Prince Henry, [Bouillon], 3, 7 October 1765.

8 NA, SP 98/71/fol. 38, ‘Copy of a Billet from Cardinal Giovanni Francesco Albani to Prince Henry, attached to the letter by Mann of 21 January 1766’, Rome, 28 October 1765. Cardinal York mediated these discussions, and Giovanni Francesco Albani, cardinal protector of Scotland, acted as his intermediary to the Pope.

9 RA, SP 433/29, Prince Charles to Lady Helen Webb and Cardinal Pier Girolamo Guglielmi, Rome, 29 January 1766; RA, SP 429/162, Giovanni Francesco Albani, Prince Henry and Prince Charles [and reply], 21 November 1765.

10 British Library [hereafter BL], Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. V, fol. 250, ‘Account of the death, autopsy and burial of the ‘Old Pretender’, January 1766’; Frank McLynn, Bonnie Prince Charlie: Charles Edward Stuart (London, 2003), originally published as Charles Edward Stuart: A Tragedy in Many Acts (London, 1988), p. 473; RA, SP 431/82, Prince Charles to Prince Henry, Paris, 22 December 1765. Charles had also long underestimated the magnitude of receiving James’s blessing before the latter died. Indeed, several of his supporters forewarned him of the consequences of such an omission. See RA, SP 402/62, Revd George Kelly to Prince Charles, 22 June 1760; RA, SP 415/153; Webb to Prince Charles, Paris, 24 February 1763.

11 RA, SP 432/18, Lumisden to Prince Charles, Rome, 2 January 1766; NA, SP 98/71/fols 43-4, ‘Billet by Albani to Prince Henry’, Rome, 28 October 1765; NA, SP 98/71/fol. 37, ‘Copy of a letter from Prince Charles to Prince Henry’, [Bouillon], 3 October 1765; RA, SP 429/159, Prince Charles to Prince Henry, [Bouillon], 3, 7 October 1765.

12 RA, SP 432/18, Lumisden to Prince Charles, Rome, 2 January 1766. The ‘people’ to whom Lumisden was alluding and noted Cardinal York sought the advice of were the French and Spanish ministers in Rome, Henri Joseph Bouchard d’Esparbès de Lussan, Marquis d’Aubeterre, and Monseñor Tomás de Azpuru y Jiménez. The Cardinal Duke also consulted Cardinal Domenico Orsini d’Aragona, the ambassador of the Neapolitan court.

13 Ibid.

14 RA, SP 433/29, Prince Charles to Webb and Guglielmi, Rome, 29 January 1766; Philip Henry Stanhope, Earl Stanhope (Lord Mahon), The Decline of the Last Stuarts: Extracts From the Despatches of British Envoys to the Secretary of State (London, 1843), p. 26, Sir Horace Mann to the Secretary of State, 1 February 1766.

15 Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 25, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 21 January 1766; McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, pp. 477-9; RA, SP 433/28, Prince Charles to Louis XV, Rome, 29 January 1766; Herbert M. Vaughan, The Last of the Royal Stuarts: Henry Stuart, Cardinal Duke of York (London and New York, NY, 1906), p. 114.

16 James Dennistoun, Memoirs of Sir Robert Strange . . . And of His Brother-in-law Andrew Lumisden, 2 vols (London, 1855), vol. II, pp. 80-1, Lumisden to James Murray, Jacobite earl of Dunbar, Rome, 14 January 1766. Alessandro Albani was the uncle of Giovanni Francesco, yet they had radically divergent political views about the Stuart family.

17 Vaughan, Last of the Royal Stuarts, pp. 115-8.

18 Ibid. The Prince charged a staunch Jacobite, Francis James Walsh, comte de Serrant (whose brother was Antoine Walsh, conveyer of Charles to Scotland aboard Le Du Teillay in 1745), of directly addressing the Spanish court. A relation of the Prince, Charles Godefroy de La Tour d’Auvergne, duke of Bouillon (whose wife was Maria Karolina Sobieska, elder sister of Jacobite Queen Maria Clementina Sobieska), interceded at the French court. Both men were also charged with asking for economic support but obtained nothing. Moreover, the influential Don Pedro Fitz-James Stuart y Colón de Portugal, marquess of San Leonardo, supported their demands without success. RA, SP 431/104, Prince Charles to Serrant, Paris, 28 December 1765; RA, SP 433/195, 198 and RA, SP 434/12, 42, 84, 116, 143, 161, Serrant to Prince Charles, Madrid, 22 February–6 April 1766; Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 30-2, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 15 April 1766.

19 For examples of Jacobites condoling their new king, see RA, SP 432/136, James Drummond, Jacobite duke of Melfort, to Prince Charles, Saint-Germain-en-Laye; RA, SP 432/160, Captain Francis Henry Stafford to Prince Charles, Avignon; RA, SP 432/166, Charles Fitz-James, duke of Fitz-James, to Prince Charles, Paris; RA, SP 433/3, David Ogilvy to Prince Charles, Paris; RA, SP 433/8, Sir John Graeme, Jacobite earl of Alford, to Prince Charles, Paris; RA, SP 433/16, Lord Louis Drummond to Prince Charles; RA, SP 433/23, Serrant to Prince Charles, Montpellier; RA, SP 433/24, Margrett O’Flannagan to Prince Charles, Paris; RA, SP 433/30, James O’Flannagan to Prince Charles, Gravelines; RA, SP 433/126, Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart, duke of Berwick, to Prince Charles, Paris, 24 January–4 February 1766.

20 RA, SP 433/53, Captain William Stuart to Prince Charles; RA, SP 433/54, Stuart to Lumisden, Boulogne-sur-Mer, 31 January 1766. Stuart was married to the only daughter of Colonel John Roy Stuart, and, in addition to condoling Charles, beseeched him on behalf of the colonel’s widow for ‘the same protection having no other dependance on earth’. This long tradition of the exiled Stuarts disbursing funds –– chiefly paying pensions –– to their supporters continued through the post-1688 ‘reigns’ of James II and VII, his son and grandsons. For accounts from 1760 to 1808, see BL, Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. VIII, fol. 70b, ‘James III, Accompts of sums supplied by, to James [via Neri Maria Corsini, marquis; afterwards cardinal]’, 1760–5; BL, Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. VIII, fol. 56b, ‘Accompts of an agent at Paris supplied by, to James III and Prince Charles [via Jean Waters and Niccolò Verzura]’, 1765–75; BL, Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. VIII, fol. 76b, ‘Accompts of an agent at Paris supplied by, to Prince Henry [via Jean Waters and Niccolò Verzura]’, 1770–2; BL, Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. VIX, ‘Accompts: Receipts and disbursements, etc., of Prince Henry’, 1760–1808.

21 RA, SP 434/143, 161, Serrant to Prince Charles, Madrid, 31 March–6 April 1766.

22 NA, SP 98/71/fols 43-4, ‘Billet written by Cardinal Giovanni Francesco Albani to Prince Henry, attached to the letter by Mann of 21 January 1766’, Rome, 28 October 1765. For the letter by Mann, see Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 25, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 21 January 1766.

23 Dennistoun, Memoirs of Strange and Lumisden, vol. II, pp. 96-7, Lumisden to Dunbar, Palidoro, 2 September 1766.

24 W.S. Lewis (ed.), The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, 48 vols (New Haven, CT, 1960), vol. XXII, pp. 514-7, Mann to Horace Walpole, Florence, 19 May 1767.

25 Historical Manuscripts Commission [hereafter HMC] 10th Report, Appendix, Part VI (London, 1887), pp. 228-9, ‘[Prince Charles’s] Instructions for Lord [John Baptist] Caryll with [Cardinal Mario Compagnoni Marefoschi’s] opinion’, 1772.

26 Corp, Stuarts in France, pp. 300-11; Jacobites at Urbino, passim; Stuarts in Italy, passim. The Stuarts’ dependence on the Papacy was preceded by the Lorraine period from 1713 to 1715, when Leopold, duke of Lorraine, received James III as his guest at Bar-le-Duc. Leopold and his noblemen spared no expense and organised parties, operas and entertainment for the Stuart claimant, who also attended the academy of Lunéville, a stop on the Grand Tour. For recent studies on time spent by James in the Duchy of Lorraine and at Lunéville, see Jérémy Filet and Stephen Griffin, ‘Duke Leopold’s Irish subjects and Jacobitism in Lorraine, 1698–1727’, History Ireland, 26:3 (May/June 2018), pp. 22-5; Jérémy Filet, ‘Jacobitism on the Grand Tour? The Duchy of Lorraine and the 1715 Jacobite rebellion in the writings about displacement (1697–1736)’, (PhD thesis, Université de Lorraine/Manchester Metropolitan University, 2021), passim; Jérémy Filet, ‘Many Happy Returns’, History Today, 73:6 (June 2023), pp. 22-4. For a further study examining the later relationship between the Lorraine and Stuart courts, including the interactions of James and Leopold, from 1716 to 1729, see Stephen Griffin, ‘Duke Leopold of Lorraine, Small State Diplomacy, and the Stuart Court in Exile, 1716–1729’, The Historical Journal, 65:5 (2022), pp. 1,244-61.

27 McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, pp. 470-550.

28 HMC 3rd Report (London, 1872), p. 421, Prince Henry to Unknown, 12 May 1767.

29 Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 26, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 1 February 1766; Dennistoun, Memoirs of Strange and Lumisden, vol. II, pp. 94-5, Lumisden to Dunbar, Palidoro, 15 April 1766; Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 30-2, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 15 April 1766.

30 Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 30, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 22 March 1766; Corp, Stuarts in Italy, pp. 353-4 (the Vatican Archives still preserve these payment accounts); RA, SP 437/92, Prince Charles to Prince Henry, 1 November 1766.

31 Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 26, 33, 35, 37-8, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 1 February, 12 July 1766, 30 June 1769, 18 August 1770; Augustin Theiner, Histoire du Pontificat de Clément XIV, 2 vols (Paris, 1852), vol. II, p. 158. Baron Douglas emerged from John Douglas, one of the Prince’s first self-designated pseudonyms, which he predominantly used after leaving Italy in 1744. Charles’s continued use of this pseudonym post-1766 likely occurred because it was one of the few Scottish (and not English) surnames recognised by Italians. Baron [of] Renfrew is a subsidiary Scottish title associated with the dukedom of Rothesay, bestowed on the heir apparent to the throne. The Prince primarily utilised it as his public title on returning to Rome before he departed for Florence. The count of Albany title appeared in many forms. These forms included the long-standing Scottish title of Albany (curiously used by Charles as the monarch traditionally gifted it as a dukedom to younger sons, usually the second son), the Italianised Albani and Albania, or the Frenchified Albanie.

32 Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 46-7, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 13 September, 1 November 1774.

33 Domenico Corri, ‘Life of Domenico Corri’, in The Singers Preceptor, or Corri’s Treatise on Vocal Music, 2 vols (London, 1810), vol. I, unpaginated.

34 Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 36, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 29 July 1769; McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, pp. 497-8; Anna Riggs Miller, Letters From Italy, Describing the Manners, Customs, Antiquities, Paintings &c. of that Country, In the Years MDCCLXX and MDCCLXXI, to a Friend residing in France, By an English Woman, 3 vols (London, 1776), vol. II, pp. 194-200.

35 McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, pp. 497-501. The Stuarts had obtained a promise from the French foreign minister that if Charles married, he would be awarded an astonishing pension of 240,000 livres, as his father before him. However, notwithstanding the Prince’s protestations, France never complied with such a promise.

36 Ibid., p. 501.

37 Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 50-1, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 26 September 1775.

38 According to Mann, Charles boasted that ‘he will not return to Rome till his brother is made Pope’. Mahon, Last Stuarts, pp. 48-9, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 27 December 1774.

39 RA, SP Box 3/129, ‘Louise’s Memorandum of complaint to Prince Charles circulated among her friends’, 5 June 1775. See also RA, SP 481/43, Louise to Prince Charles, 5 June 1775.

40 McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, pp. 530-6. The relationship between the later Stuarts and the Swedish king is significant, considering the long-standing relationship of that kingdom with the deposed dynasty since the aftermath of the ’15. See Costel Coroban, ‘Sweden and the Jacobite Movement (1715–1718)’, Revista Română pentru Studii Baltice şi Nordice 2:2 (2010), pp. 131-52. It was masonic interests that engendered Gustav’s involvement with the Stuarts. At that time, the King struggled to control neo-templar freemasonry, specifically the Order of Strict Observance. He wished to avoid extending its radical reforms to Sweden, promoted by the German provinces of this order at the Convent of Wilhelmsbad of 1782. The neo-templar movement regarded Charles as its Grand Master from a foundation myth invented by its creator, Karl Gotthelf, baron von Hund und Altengrotkau. During his visit, Gustav exchanged his help for a patent in which the Prince would recognise him as his coadjutor and successor as Grand Master. Pericle Maruzzi, La stretta osservanza templare e il regime scozzese rettificato in Italia nel secolo XVIII (Rome, 1990), pp. 221-86; Carlo Francovich, Storia della Massoneria Italiana: dalle origini alla Rivoluzione Francese (Milan, 2012), pp. 148-55.

41 BL, Add. MSS. 34,638, Stuart Papers, vol. V, fol. 341, ‘Charlotte Stuart, natural daughter of the ‘Young Pretender’, styled Duchess of Albany: Papers relating to her legitimisation’, undated. Following the elevation of Charlotte, her father again asserted the royal prerogative, creating a baronet (John Steuart) and two Knights of the Thistle (Milord Henry Nairne and Baron John Baptist Caryll of Durford) among his remaining few adherents. Stefano Baccolo, ‘The Last Jacobite Courtier: The Silent Life of Henry Nairne (Part II)’, The Jacobite: Journal of the 1745 Association, 172 (2023), pp. 20-2.

42 HMC 10th Report, Appendix, Part VI (London, 1887), ‘Suggestions for a medal in honour of the Duchess of Albany’, undated.

43 Henrietta Tayler, Prince Charlie’s Daughter: Being the Life and Letters of Charlotte of Albany (London, 1950), p. 109.

44 RA, SP 514/50-4, ‘Protest of Cardinal York’, 27 January 1784; Francis John Angus Skeet, The Life and Letters of H.R.H. Charlotte Stuart: Duchess of Albany, Only Child of Charles III, King of Great Britain, Scotland, France and Ireland (London, 1932), pp. 64-5. See also BL, Stowe MS. 158, fol. 247, ‘Declaration of Henry Benedict Stuart, Cardinal York’, 27 January 1784.

45 George F. Warner (ed.), Facsimiles of Royal, Historical, Literary and Other Autographs in the Department of Manuscripts, British Museum: Series I.–V., 5 vols (London, 1895–9), vol. V, pp. 11-2, Prince Charles to Prince Henry, Florence, 2 November 1784.

46 RA, SP 507/92, Louis XVI to Charlotte Albany, ‘Legitimisation of Charlotte, Duchess of Albany’, 1784 (transcribed in Skeet, Duchess of Albany, appendix III, pp. 161-3); Alice Shield, Henry Stuart, Cardinal of York and His Times (London, 1908), p. 248. Maria Luisa was the sister of Ferdinand IV and III. Her husband, Leopold I, grand duke of Tuscany, was the brother of Ferdinand’s wife, Maria Carolina.

47 Lewis (ed.), Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, vol. XXV, pp. 548-50, n. 11, Mann to Walpole, Florence, 18 December 1784; Mahon, Last Stuarts, p. 91, Mann to Secretary of State, Florence, 29 November 1785.

48 Tayler, Prince Charlie’s Daughter, pp. 79, 84, 106, 108-9; A. Viator (Anon. Traveller), ‘The Pretender’s Daughter’, in Edward Cave [Sylvanus Urban, pseud.] (ed.), The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle: For the Year MDCCXCVII., Vol. LXVII., Part the Second (London, 1797), p. 1,000; BL, Add. MSS. 34,635, Stuart Papers, vol. II, fol. 330, Pius VI to Prince Henry, 3 October 1785. This papal letter congratulated the Cardinal Duke on his brother’s improving ‘spiritual condition’. A tribune of honour was usually a temporary wooden stage with seats standing apart and set above the area reserved for bystanders of ceremonies. Such tribunes were erected only for guests of exceptional importance; popes granted them to royalty and sometimes distinguished attendees, including Christina, queen of Sweden, James III, Charles Edward and Charlotte Stuart. The Holy See also regarded Anna Amalia von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, who had been regent of the duchies of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach, as a sovereign and thus afforded her the same honour. Famiglia Chracas, Diario Ordinario (Rome), issues nrs. 1,164 (25 February 1786), 1,256 (13 January 1787), 1,460 (27 December 1788).

49 McLynn, Charles Edward Stuart, p. 549. Henry’s enemies used this contemporary Latin phrase translated into English as ‘in the lands of the unbelievers’ to mock his newly claimed status.

50 Urban (ed.), The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle: For the Year MDCCLXXXVIII., Vol. LVIII., Part the First (London, 1788), p. 363; RA, SP 515/72, Il Canonico Carlo Campoli, ‘Relazione Di quanto è occorso dopo la Morte del Sermo Carlo Odoardo Figlio di Giacomo III Re’ d’ Inghilterra, Scozia, Francia, Ibernia & Seguita in Roma li 31 Gennaro 1788’, 31 January 1788.

51 Kathryn Barron, ‘“For Stuart blood is in my veins” (Queen Victoria). The British Monarchy’s Collection of Imagery and Objects Associated with the Exiled Stuarts from the Reign of George III to the Present Day’, in Corp (ed.), Stuart Court in Rome, p. 155. Only on his daughter Charlotte’s tombstone was the Prince called Charles III until the end of the Jacobite epoch. Yet the tomb –– initially located in the Church of Saint Blaise in Bologna –– has been moved many times. The inscription visible today in the Church of the Holy Trinity in the same town bears no reference to him. Giuseppe Marinelli, ‘Note sullo scomparso monumento sepolcrale a Charlotte Stuart, duchessa d’Albany’, Strenna Storica Bolognese (Bologna, 2014), pp. 217-38.

52 Jane Clark, ‘The Stuart Presence at the Opera in Rome’, in Corp (ed.), Stuart Court in Rome, pp. 85-93.

53 The political heritage of the court –– or courts –– from 1689 to 1807 also appears in its material culture, such as the importance of portraiture, numismatic materials and glassware, including the crucial choice of artists, to promote the regal and social status of the deposed dynasty and disseminate their propagandistic aims. For notable studies on Jacobite material culture, see Noël Woolf, The Medallic Record of the Jacobite Movement (London, 1988); Geoffrey B. Seddon, The Jacobites and Their Drinking Glasses (Woodbridge, 1995; 2015 edition); Edward Corp, The King over the Water: Portraits of the Stuarts in Exile after 1689 (Edinburgh, 2001); Neil Guthrie, The Material Culture of the Jacobites (Cambridge, 2013); Murray G.H. Pittock, Material Culture and Sedition, 1688–1760: Treacherous Objects, Secret Places (Basingstoke, 2013).

54 Corp, Stuarts in Italy, Chapters 4 and 13.