Abstract

Three popular songs of enormous cultural significance are ‘In My Life’, ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, all released by the Beatles in the 1960s and all set in the same part of Liverpool. In an original investigation, this article looks into the growth of that part of the city from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1950s, examining the changes to the landscape. This was as the initially rural environment gave way to a typical twentieth-century townscape of houses, roads, parks and schools. The memories of people who resided there are related and these along with old maps, photographs, newspaper articles and census details are examined to give a sense of the lived-in location that inspired the lyrics of Paul McCartney and John Lennon. The phenomenon of palimpsest – ancient features slightly visible underneath modern ones – is applied to this study of the location and a new concept of inverse palimpsest – the old consciously superimposed on the new – is put forward in a novel approach to landscape analysis.

Introduction

In 1967 a duo of popular songs titled ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ was released as a double A-sided single by the Beatles. Along with a ballad of remembrance, ‘In My Life’, that was produced a couple of years earlier, these became some of the most famous lyrics ever written that involve the concept of a specific location.Footnote1 ‘Penny Lane’ in particular has spawned numerous follow-up creative endeavours including novels and memoirs.Footnote2 All three songs are set in Liverpool, close together in the same southern quarter of the metropolis, but despite the songs’ huge popularity and the associated interest in learning more about their backgrounds,Footnote3 hitherto there has been no systematic investigation of related local history. The aim of the present article is to examine the growth of the built environment in an original suburban study, to show how the townscape that inspired the lyrics written by Paul McCartney and John Lennon came to life. Adam Menuge has shown how this sort of understanding of the history and character of a suburb can heighten the sense of place. The focus allows an appreciation of both natural and built features, and Menuge also highlighted the usefulness of ‘populating the landscape with real people’ by showing how individuals used and experienced the environment.Footnote4 Stephen Daniels identified intense and immediate moments in cultural geography that connect to a theatre of memory, and we will see this presented here.Footnote5 To undertake the investigation, I have gathered memories and found other repositories of recollections that are available in books and on the internet. Historic maps are of great importance in helping to follow developments, and photographs help discover details of architectural features. Contemporary newspapers, trade and postal directories and censuses provide crucial details of people’s lives. Documents in Liverpool Record Office including local societies’ newsletters also help to set the scene of increasing urbanisation.

Janet Donahoe has discussed how memory, tradition and place are intricately interwoven and brings in the seminal work of Gaston Bachelard who argued that memories of childhood domains play a necessary role in dreaming and imagination.Footnote6 Furthermore, in studies of psychological attachment, it has been shown that places can serve as prompts for memories, and these can link people to erstwhile events.Footnote7 This is directly related to the work of McCartney and Lennon, who drew on their young lives to create the three song tracks which have been described as ‘childhood nostalgia’.Footnote8 In an additional relevant aspect of geography, William Glover has shown how the very early layout of a city influenced later developments,Footnote9 and we shall see this in the study of Penny Lane. In both Donahoe’s and Glover’s works the idea of palimpsest comes to the fore. This is the overwriting of older forms with those earlier arrangements remaining visible through the new, although perhaps unclear or overlooked. As well as showing palimpsest in the developing landscape of Liverpool, I will put forward an innovative concept, that of inverse palimpsest where the past is retrospectively and consciously superimposed on the present, arising definitively from the cultural phenomenon that is the Beatles.Footnote10

The Penny Lane area in the nineteenth century

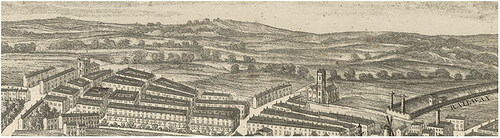

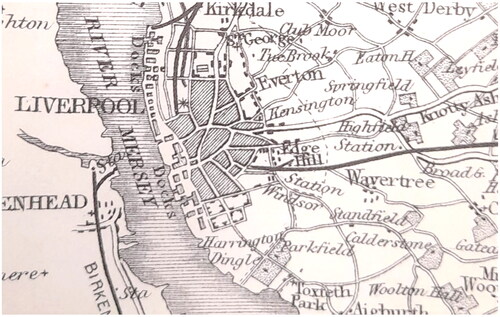

Penny Lane lay at the southern end of the district of Wavertree, which was a village in medieval times and merited a listing in the Domesday Book.Footnote11 During the Industrial Revolution, Wavertree grew to be a small town with a population of about 4000 by the late 1850s, lying just a few kilometres from the major port of Liverpool but with distinct rural features ().Footnote12 Ackerman’s panoramic map of Liverpool gives an idea of how the countryside looked in relation to the burgeoning urban area. One can discern gently rolling hills, with fields bordered by wooded hedges ().Footnote13 The railway is shown on the right-hand side of the figure, entering Liverpool from the west and a train arriving here will have passed close to Wavertree.

Figure 1. 1858 map showing Wavertree to the south east of Liverpool.Footnote14

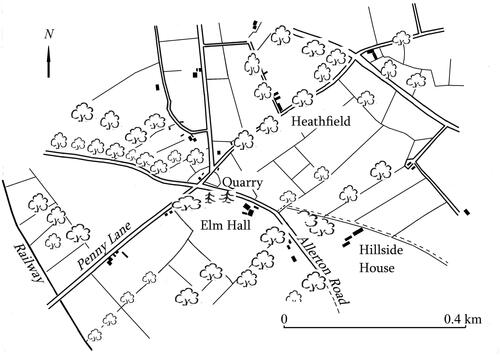

Farming in the area was mixed and included wheat, oats, potatoes and turnips along with sheep and dairy herds, and the field hedges were home to a variety of wildlife, including small birds the hunting of which provided sport for locals.Footnote15 Some agricultural buildings were thatched.Footnote16 There were abundant trees, species of which included fir, elm, oak, ash, sycamore, beech, lime, alder and cypress.Footnote17 The 6" Ordnance Survey map of 1864 shows more details (). There were many fields and a few of them were relatively large with sides around 100 metres. Some were very small with sides of around 50 metres, and some were meadows.Footnote18 There were several large houses marked on the 1864 map and Sari Maenpaa has shown how these were the homes of Liverpool businessmen, whose wealth allowed them to migrate from the crowded centre of Liverpool to these healthier regions.Footnote19 Wavertree was specifically identified as a wholesome area and as the local board of health completed a system of drainage in the mid-nineteenth century, property prices rose and a second railway line was installed that passed the western end of Penny Lane.Footnote20 A Roman Catholic bishop resided with staff in a monastery designed by Augustus and Edward Pugin,Footnote21 and other middle-class occupations represented were stock broker, university professor, solicitor, architect, and insurance broker. The occupant of Hillside House described himself as a magistrate and landed proprietor.Footnote22 There were signs of gentrification: naming houses after local nature, for example ‘Elmhurst’ and ‘Elm Hall’, ‘Sycamores’ and ‘Beech Lane’, and game shooting was practised by some.Footnote23 There was differentiation in the class of persons resident in the area. In leafy Penny Lane, corn merchant John Lynch employed four live-in servants including a gardener, and an advertisement for the sale of the property in 1858 gives a picture of the living accommodation:

Figure 3. Map showing Penny Lane, surrounding fields and built landscape (re-drawn from 1864 6" Ordnance Survey map).Footnote29

A commodious and well-built house in Penny’s Lane, near Elm Hall, Wavertree, with about 4 statute acres of land attached, laid out in gardens, lawn and paddock. The house contains three excellent entertaining rooms with the customary offices and spacious entrance and staircase on the ground floor, communicating with the conservatory. The first floor contains seven bedrooms, dressing room, bathroom and water closet; and also two rooms in the attic storey. The outhouses consist of two stalled stable, loose box, harness room, coach house and man’s room over, the whole being complete for the residence of a genteel family.

In nearby Hillside House, merchant Archibald Sinclair employed a gardener, three house servants and a coachman.Footnote24 The Royal Institution of British Architects has a lithograph of the building, created soon after the house was built in 1830, showing sheep grazing on a vast lawn surrounded by established trees.Footnote25 Other households also employed stable staff enabling movement to and from the city and by the 1850s there were horse-drawn omnibuses too,Footnote26 and horse-drawn trams in 1881.Footnote27 These helped to increase the desirability of Wavertree as a place of residence and, along with the pleasant landscape, it was a welcome escape from city smells. Views were ‘extensive and picturesque’, the area ‘salubrious and select’.Footnote28

While many of the household servants were Lancashire born, a large number were from elsewhere in the British Isles: Wales, the Isle of Man, Cheshire, Westmorland, Cumberland and Staffordshire, for example. Many were from Ireland indicating that country’s proximity to Liverpool and the effects of the famine.Footnote30 Some staff, particularly gardeners and coachmen, were given accommodation in separate, self-contained constructions. The bishop’s coachman lived in the lodge house, the groundsman had the dedicated ‘gardener’s house’ and the gardener at Hillside House resided in Hillside Lodge. Several properties were named after natural features such as types of tree, and John Lynch’s house in Penny Lane was titled Grove House. A footpath is marked, beginning in a field near Elm Hall and leading off in a south easterly direction and this is very likely to be the line of an ancient connection between Liverpool and the settlement of Woolton, about 10 km from the city centre. At the beginning of the twentieth century, this minor right of way was to be transformed into a major road which became significant in the Beatles story. This will be discussed in a later section.

The next available Ordnance Survey map, published in 1894, shows that the park around Heathfield House had also been landscaped and many trees planted. Most noticeable on the map was the changed field layouts. Many boundaries had been altered and kinks and bends removed, leaving larger fields of a more uniform shape, mostly rectangular or near square. Furthermore, near the bishop’s house there was now Liverpool waterworks.Footnote31 The changing field shapes could be to facilitate cultivation by the mechanised equipment that was increasingly used at the end of the nineteenth century such as the horse-drawn plough, hay rake and cultivator,Footnote32 but the water works are a sign of the growing housing provision and those regular-shaped fields lent themselves to housing estate layouts. In 1857, the owner of the Hillside estate had advertised his fields for development: ‘Hillside House estate, about 4 miles [6km] south of Liverpool… there is a private road to the land from Penny’s Lane…From 30 to 50 statute acres of this beautiful estate are now placed in the market for sale in one or more lots for mansions, villas or a public park’.Footnote33 A polo ground was put in place near the monastery by the late 1880s. However, the 1894 map shows that only a very few such villas had been erected, and the reason for this may lie a few hundred metres away to the north west where the lower and middle classes had begun a forward movement towards south Wavertree. Inspection of the map reveals that just beyond Penny Lane, in Toxteth, ranks of terraced dwellings had started an advance towards Elm Hall and the Hillside estate. The houses were built of red brick, with some decorative architectural features such as bay windows and ornamental brickwork underneath the eaves. The projecting bay windows allowed for small areas between the front of the house and road into which some householders put plants. Wage-earning occupants were typically travelling salesmen, clerks, factory workers, shop assistants and manageresses, or seamen. Some took in lodgers.Footnote34 There was differentiation in the accommodation provided in different streets. Avondale Road properties, for example, contained two double bedrooms and a single bedroom whereas the wider plots in Hawarden Avenue, while still terraced, allowed houses to have three downstairs reception rooms and five bedrooms.Footnote35 The targeted market of a more genteel working-class family in this street is clear from the use of the term ‘Avenue’ rather than ‘Road’, and inspection of the very detailed Ordnance Survey town plan of 1903 shows that the thoroughfare was indeed lined with trees. In 1911, as well as clerks and salesmen, Hawarden Avenue housed some professional men including a solicitor and an accountant.Footnote36 Just the same as all the other streets, however, Hawarden Avenue had only a rear, paved yard opening onto a back lane. This provided a safe space for the playing of ball games, and even the roads at the front of the houses were relatively secure as, even in the mid-twentieth century, there was little motor traffic and few parked vehicles meant that children could play games on the road and in the gutters.Footnote37

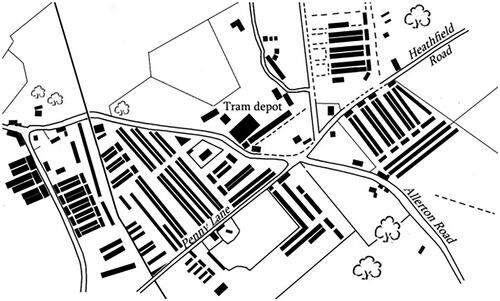

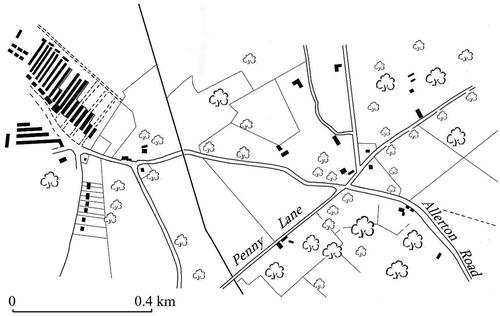

There was a new 30-acre burial ground named Toxteth Park Cemetery, which followed the nineteenth-century fashion for elegant grave sites involving plants, architectural headstones and ‘broad and winding walks.Footnote38 Also promoting a healthier environment by providing spaces for recreation were a lacrosse ground and cricket ground, and there were a football pitch and a cricket ground at the south-western end of Penny Lane. There were new Catholic and Anglican churches, and a workhouse which could accommodate up to 700 inmates.Footnote39 The unreliability of manual and industrial labour is clear from the numbers and proportions of porters, labourers, seamen, dressmakers, and charwomen present in the workhouse. An infectious diseases hospital was built and a children’s home was established in Richmond Lodge, formerly the home of Sir Thomas Earle.Footnote40 Inmates of the hospital included cleaners, labourers, factory and shop workers and many out-of-work sailors. One had earlier been a master mariner and in a later memoir, Jack Maddox details his childhood shock at learning of out-of-work skilled seafarers whose competencies were of no use on land.Footnote41 Patients were suffering from a range of complaints including syphilis, gonorrhoea, ulcers and chest complaints. The children’s home was an offshoot of the workhouse and could accommodate 80 children.Footnote42 A contemporary map captures a moment when the parallel lines of novel terraces were under construction, as dotted lines indicate roads that had been laid out but not yet built upon ().

Figure 4. Map showing housing to the north west of Penny Lane (re-drawn from the 1894 6" Ordnance Survey map).

Alice Butler-Warke has shown how Toxteth’s ‘spatial taint’ could be seen from 1900,Footnote43 but individuals with the means to move away were doing so some thirty years earlier. Shipping magnate George Warren lived with his family in a gracious tree-lined avenue, with large, semi-detached villas, some having summer houses and conservatories,Footnote44 but despite the quality of this individual street, the increasingly rough nature of Toxeth pushed Warren away. His wealth enabled him to leapfrog Penny Lane and purchase a building plot in exclusive Woolton, still very rural and away from the advancing terraces but nevertheless defined as part of the Wavertree Division of the Borough of Liverpool.Footnote45 He chose a site on a gentle, south-facing slope with commanding views over the river Mersey to the Welsh Hills.Footnote46 Warren built a large villa there. It took several years to construct but by 1876 the family had decided on its name – ‘Strawberry Field’, after the former agricultural plot on which it was built.Footnote47 A sale description in 1884 shows that the house was of big proportions, containing 16 bedrooms, a large and lofty dining room, billiard room, coach house and separate accommodation for the coachman, among other features.Footnote48 In due course, the garden was landscaped, trees planted and glasshouses installed, and more surrounding grand houses were similarly developed.Footnote49 The pattern of elegant properties with spacious grounds belonging to the higher classes that was seen around Penny Lane during the earlier part of the century is apparent again here in Woolton, and this particular mansion was to be another topographical feature that played a major part in the Beatles story as we shall see later.

Developments in the twentieth century

By 1909 a dramatic change could be seen as the advancing terraces had surrounded Penny Lane (). The houses were similar to those adjacent to the workhouse – bay windows, small spaces between the bay and the pavement, and a few decorative features to enhance the front wall.

Occupants included some professional types as well as retailers and those whose occupation combined artisanship with retail. These included butcher, confectioner and stationer’s assistant. In Calton Avenue there was a cowshed and dairy attached to no. 21, one of the many milk suppliers in the area. There were also other types of service providers including gardener and theatre manager.Footnote50 Many households had a live-in servant and in Calton Avenue of the 29 households, nearly half employed such a person – always female, unmarried and with an average age of 23. The local newspaper published a classified column labelled ‘Servants Wanted’ and often the advertisements would specify ‘Protestant’ or ‘Catholic’, an illustration of the religious dialectic present at that time.Footnote51 In Penny Lane, Grove House – the former home of John Lynch and then later industrialist Andrew George Kurtz and his heirs – became a ‘home for incurable children’.Footnote52 Here the comfortable, nine-bedroom house with grounds of about six acres and a conservatory that could be used as a playroom, proved of immense value in the care of the children.Footnote53 Most of the youngsters suffered from mobility issues including paralysis, knee, spine and hip disease. Nursing staff were often from a large distance away including London and Scotland.Footnote54 The Grove House side of the road continued as a more up-market location with a justice of the peace, company director, physician, dentist and a person of independent means.Footnote55

Nearby, Heathfield House still existed but its park had been decimated. While the house and its grounds remained a ‘sunny spot’, providing a happy ‘day in the country’ for 450 of the ‘poorest of the poor from the city’s slums’,Footnote56 a 1902 sale advertisement described the 31-acre estate as ‘ripe for building purposes’. It was bought by Charles Berrington,Footnote57 who immediately set about developing the site into the familiar pattern of terraced houses with some new, faux-Grecian features. These included porticoed front doors and Corinthian columns giving the false impression of supporting the bay windows. A house in one of these streets − 9 Newcastle Road – was later to be the birthplace of John Lennon. This house was unoccupied on census night in 1911 but on either side were music teachers and an artist.Footnote58 Other near neighbours included a barman, dressmaker, tyre repairer and labourer. Like many of them, Lennon’s maternal forebears, the Stanleys, moved in from rougher parts of the city. In their case it was various addresses around Toxteth including Windsor Street, Lydia Ann Street, and Upper Frederick Street which were sandwiched between the docks, foundries, soap works, railway depots, mills and the Cornwallis Street public baths.Footnote59 These wash rooms had been built as a nineteenth-century endeavour to improve public cleanliness and health and were confirmation that the area was unsanitary and often associated with the ‘dangerous classes’.Footnote60 The Brewer and Wyllie bird’s eye view of Liverpool gives a dramatic picture of the cramped, busy and smoky townscape in Toxteth that the Stanley family escaped,Footnote61 and their experiences in that location may well be the origins of the well-documented ‘middle-class pretensions’ of some members of the family and their desire to live in a more salubrious area.Footnote62 An advertisement for the sale of the Newcastle Road estate indicated that these were – fortunately for those fleeing the docklands – ‘cheap houses’ to be sold on ‘easy terms’ and showed that the dwellings included two parlours, a kitchen and scullery, three bedrooms, a bathroom and separate lavatory.Footnote63 Only one of the households in the 1911 census, that of a retired clerk, included a live-in servant.Footnote64 There were some larger and more desirable houses in nearby Heathfield Road and an early photograph illustrates that dwellings in this residential thoroughfare were large, with wide front doors and very solid-looking bay windows.Footnote65 The pavement was lined with saplings and in 2024 those trees have grown up providing deep shade in the summer. A former resident of Heathfield Road, whose father was a solicitor, recalls: ‘My parents saw it as a going up in the world since south Liverpool, where the Penny Lane area is situated, is a relatively affluent area’.Footnote66 Sounds from the docks, nevertheless, were audible. There were various routes to the city centre from this location and some residents occasionally chose to go via a slum area in order to look at the way in which poorer people lived.Footnote67

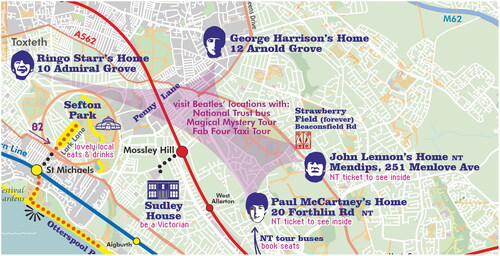

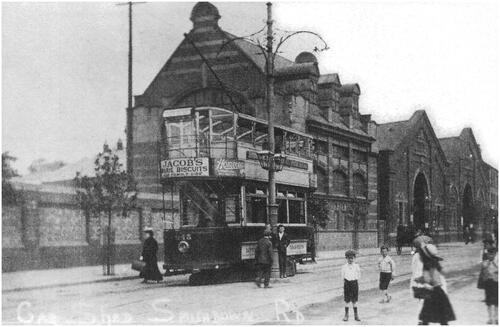

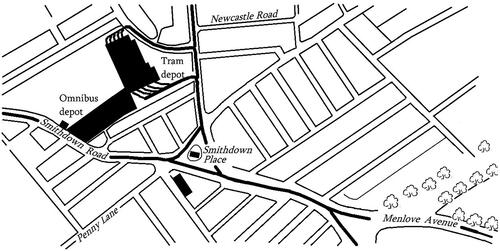

The nature of the Penny Lane district continued to change as the twentieth century progressed and the growth of the area went hand-in-hand with improved transport. While the early nineteenth-century sale particulars highlighted the villas’ close proximity to Liverpool thus enabling a walk to work,Footnote68 and sale advertisements for larger dwellings highlighted their coach houses, by 1858 Kelly’s Post Office Directory detailed an ‘omnibus to Liverpool and back every half hour’. In 1873 these ran every quarter of an hour,Footnote69 and by 1900 electric trams were serving Wavertree. These were part of a network serving the whole Liverpool area,Footnote70 providing a transport situation that changed demographic interactions as the working and higher classes met in close proximity.Footnote71 There were new criminal offences too. As soon as the tram system was underway, court appearances were seen, usually related to avoidance of ticket charges,Footnote72 and in one instance a conductor was convicted of embezzling fares.Footnote73 There was a case of a tram driver seeking compensation for injuries sustained in a collision with a horse-drawn vehicle,Footnote74 and several instances of people obstructing the rails.Footnote75 This innovative form of mobility changed the landscape too. There was a depot near the Heathfield Road/Penny Lane junction and with it was a refuse destructor which produced the necessary power, on a site that had formerly been rich in trees. Local waste materials were burned in the destructor – an early form of recycling that produced electricity along with noxious fumes – but an attempt to recreate something of the pastoral was made by planting saplings along the pavement (). There were many tragic accidents. Two of the worst cases were of a retired police officer who was knocked down and killed by a tram near the refuse destructor, and a retired master mariner similarly killed nearby two months later. The advent of the tram also explains the reformation of the quarry junction which is made plain in the 1939 25" Ordnance Survey map: levelling the quarry and cutting into the land around the simple crossroads enabled the construction of a triangular island within a surrounding layout of metal tracks. This arrangement allowed the electric vehicles to turn into and out of the various main roads (). To be named Smithdown Place, this meeting of roads is shown in the Kelly’s Directory of 1946 as a retail area encompassing a fruiterer, tobacconists, a dressmaker and a hairdresser named Leslie Bioletti, who was to become the most well-known barber in modern popular culture, thanks to prominent positioning in McCartney’s lyrics: 'In the corner there is a barber showing photographs…'.Footnote76

Figure 6. An electric tram outside the depot near the Penny Lane/Heathfield Road junction.Footnote77

Figure 7. Section redrawn from the 1939 25" OS map showing some key sites including the bus shelter on the island in Smithdown Place, which features in the Penny Lane lyrics. The church where McCartney sang as a choirboy is the highlighted building directly south of the bus shelter.

A cricket ground adjacent to the refuse destructor, newly installed at the turn of the nineteenth century into the 1900s, was covered with terraced housing by the 1930s and Heathfield House was eventually demolished and replaced in the same way. In nearby roads there were butchers, grocers, newsagents, more tobacconists, bakers, shoe repairers and all manner of trades and services that were essential for everyday life in a suburb. At a time of limited refrigeration in the home, daily shopping for food required an easy availability of provision dealers and there were a few door-to-door traders and Romani people selling pegs too. Coal was delivered by lorry, one of the few forms of motorised transport seen in the side roads.Footnote78 Home-made entertainment began to grow and flourish, particularly after the Second World War. For example, Wavertree Community Association was founded and established a gramophone society, men’s and ladies’ snooker leagues, and held regular dances. There was a football club, whist drives and a rolling programme of film shows and illustrated talks by guest speakers. The society established a library, hosted trainings given by the Workers’ Educational Association and organised fetes and shows.Footnote79 There was a Wavertree choir.Footnote80 Amateur sport could be played in Sefton Park, where class differentials were made plain. There were the genteel persons who paid sixpence to sit within an enclosure separated from most spectators, and an enormous gulf in behaviour between boys from Toxteth and their opposite side from the Wavertree terraces.Footnote81 Most children attended Sunday school, and churches offered opportunities for choral training.Footnote82 There were several cinemas in the area but the least expensive was the Grand, not far from Penny Lane, and a short tram ride away was the Pavilion theatre. Stan Hall recollects: ‘It wasn’t the top rank of theatre. They used to get some American comedians coming over. Arthur Askey came on once, I don’t know why he’d come, because he was quite big. He sang 'Maybe it’s Because I’m A Londoner' and they booed him off’.Footnote83 There was a swimming pool known as the Picton Baths, and during school term time, crocodile-like lines of school children could be seen wending their way there for coaching sessions, including from Dovedale primary school, which Lennon attended in the 1940s and early 1950s, situated just off Penny Lane.Footnote84 The grounds of Grove House were made into an athletics centre and the Wavertree Community Association organised their first annual youths’ sports festival there in 1950,Footnote85 but the grassy site was completely hemmed in with built accommodation by this date. The once bucolic Wavertree was overwhelmed with brickwork, and the mansions of the early nineteenth century were gone, with just ghosts remaining in street names including Hillside Road and Elm Hall Drive.Footnote86 In 1938, a newspaper reporter wrote of his amazement at learning of those grand houses:

Having occasion yesterday to consult an Ordnance map of 1846, I was interested to discover the origins of the names of several thoroughfares there now well known. Dudlow Hall and Elm Hall on the two sides of what is now Menlove Avenue … It was a surprise to discover that near what is now Hillside Road there stood a Hillside House, passed by a mere footpath on the Wavertree side, while south-west of Allerton Road stood Hillside Villa.Footnote87

The development of the road to Woolton shows an earlier pattern repeating itself. Where once Penny Lane was the place for the wealthy to establish gracious homes with park-like grounds, the advance of the lower-orders pushed them away. Now, as houses, roads and people approached Woolton, so the upper-middle classes moved away. The area began to lose some of its prestige and this was largely to do with the increased accessibility of the area with its associated traffic problems and crime. Menlove Avenue was officially opened in 1910,Footnote98 and the familiar occurrence of accidents arrived. A university lecturer’s wife was hit by a speeding motorcyclist and killed near the junction with Allerton Road and the rector of St Peter’s church, Woolton, was knocked off his bicycle by a car and killed at the junction near Vale Road.Footnote99 A 64-year-old labourer was killed by a tram while walking towards Woolton.Footnote100 Crime increased. For example, in 1935, young trouble makers travelled by tram and caused damage to growing crops. A newspaper reported: ‘Cheap tram fares in Liverpool are held to be responsible for an invasion of strawberry fields in Woolton. Market gardeners allege that large numbers of school children have been raiding their plants and a petition has been organised to withdraw their tickets’.Footnote101 A gas fitter stole jewellery from a house in which he was working,Footnote102 and in 1941 an unemployed man from nearby Bootle was charged with breaking and entering houses in Menlove Avenue and stealing cash and other items of value.Footnote103 Further mirroring the pattern seen a generation earlier in Penny Lane, the former large family homes, with extensive gardens prized for their therapeutic qualities, were sold and converted into a range of institutions. These included a council-run remand home for boys created from a mansion previously owned by a member of Prime Minister Gladstone’s family. The Salvation Army established two care homes, enabled by a legacy from Mary Jane Fowler, whose important philanthropy has been overlooked and forgotten.Footnote104 One care home was for elderly women and, to be of immense significance in the Beatles story, the other was a home for girls in George Warren’s mansion, Strawberry Field.Footnote105

The Lennon and McCartney years

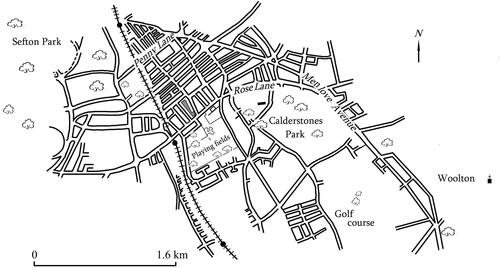

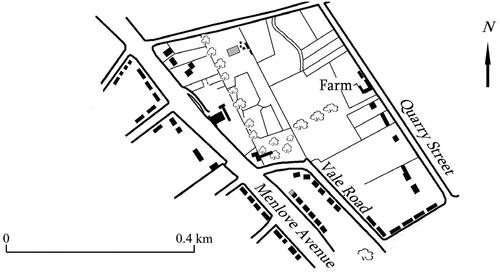

The Penny Lane and Menlove Avenue part of Liverpool had thus grown to be a thriving suburb containing infrastructure typical of a mid-twentieth century, edge-of-city neighbourhood. gives a wide-area view of the landscape at the time McCartney and Lennon were growing to adulthood and which was to provide memories that would later be built into their classic lyrics. The distinction between the built-up Penny Lane quarter and the more gracious and spacious land to the south east is very clear, with a frontier at Rose Lane. When Lennon was five years old, in a move that has been well documented, analysed and discussed, he was taken to Woolton to live with his aunt Mimi and her husband,Footnote106 and thus experienced most of his childhood in a leafy middle-class area (). Lennon’s half-sister has described how Mimi was anxious to purchase the house named Mendips, or 251 Menlove Avenue, forcing the sale by occupying the premises as the previous tenants moved out.Footnote107 The reason for this urgency is unclear but the house’s four bedrooms may well have been key as the 1945 electoral roll shows Mimi’s father and youngest sister being resident there too, while Lennon’s mother Julia – pregnant by a man who was not her husband – was living a short walk away. Mimi’s husband is not present on the roll but he may have been living away because of war work.Footnote108 This was a pivotal time in Lennon’s young life when the family was making plans to remove him from his mother’s care and for Mimi to take over the responsibility, a move that was to give him profound and long-lasting feelings of rejection.Footnote109 In due course, after the plans had been carried out, the smallest bedroom in Mendips, at the front and overlooking the road, became his. The house had features that fulfilled some of Mimi’s aspirations – she retained the servants’ bell as a constant reminder of class distinctions, and there was a good-sized garden in which the boy could play.Footnote110 There were other attractions to make enjoyable times for Lennon as he grew up. There were plentiful trees, farmland and a golf course where McCartney remembers trying to get a teenage job as a caddy as it was easily accessible from his home in the adjoining district of Allerton.Footnote111 shows the complicated arrangement of boundaries which enabled exciting adventures for small boys. There were walls to scramble over, including into the well-wooded grounds of Strawberry Field. Lennon’s very close friend Pete Shotton has written about how Woolton’s green expanses provided a multitude of secret dens and playgrounds, and there was a pond which engendered numerous escapades. Shotton recalls himself and Lennon starting bonfires that subsequently grew out of control and he remembers once running away from a blaze to hide on the golf course.Footnote112 Lennon himself said he was shot at while stealing apples.Footnote113 It was not all boyish adventure, though. Strawberry Field put on garden parties during the summer,Footnote114 and in 1969 Captain Edna Callaway of the Salvation Army said, ‘I think [Lennon] used to play with the children.Footnote115 Lennon remembered, ‘I used to go to their garden parties with my friends… We’d all go up there and sell lemonade bottles for a penny and we always had fun at Strawberry Fields’.Footnote116 Here Lennon has added the letter 's' to the end of the mansion’s name as he did in the song lyrics.

Figure 8. Wider view showing Woolton in relation to Penny Lane. Lennon’s senior school, Quarry Bank, is the shaded building above the 'C' of Calderstones. Map redrawn from the 1956 Ordnance Survey 25" edition.

Figure 9. The Strawberry Field part of Woolton. Mendips is the shaded building near the 'l‘ of Menlove; Strawberry Field is the larger shaded building to the north of the map. Redrawn from the 1956 1:10,000 Ordnance Survey map.

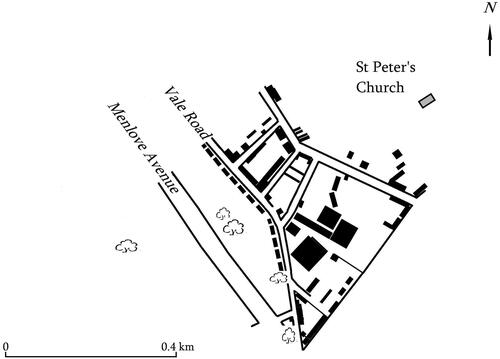

Figure 10. The southern part of Woolton, redrawn from the 1956 1:10,000 Ordnance Survey map. Eleanor Rigby Woods’s childhood home was near the southernmost end of Vale Road.

Lennon and McCartney each joined church choirs, the former at Woolton parish church, the other at St Barnabas in Smithdown Place, and both these places of worship had been built to answer the needs of growing communities and were designed by Liverpool architects.Footnote117 The wealth of the local congregation in Woolton was such that a house-to-house collection spread over 15 months realised £4000 in contributions in 1957, about £80,000 in 2024 money,Footnote118 but not everyone living in Woolton was affluent. Further away from Strawberry Field, Eleanor Rigby Woods, who may have been the real person behind the McCartney song ‘Eleanor Rigby’, grew up in a five-room, mid terrace house near a massive brick-built hosiery factory that towered over nearby houses ().Footnote119 Her neighbours included a pawnbroker’s assistant, general labourer, bricklayer, laundress and several gardeners and most of them were born within the parish.Footnote120 Within Woolton, therefore, there was a class and origin difference. To the north there were larger and less densely packed dwellings, housing a higher proportion of white-collar workers and more incomers.

While the Penny Lane area was not as open in its aspect as Woolton, there were nevertheless large and small sections of greenery that contrasted with this busy and bustling suburb and which residents could use to escape the brickwork. There was 267-acre Sefton Park, not far from the westernmost end of Penny Lane, part of the city council’s great plan to surround the whole metropolis with vegetation.Footnote121 Stan Williams recalls Sundays when multitudes of families would walk around the caves and waterfalls in the fairy glen or listen to band concerts near the lake.Footnote122 Although the park replaced farmland, and agriculture was largely gone, Tim Holmes remembers a farmer walking his dairy herd, twice a day, along Penny Lane from the farm near the railway bridge to a pasture near the edge of Sefton Park. The same field was also used for a travelling fair and circus and Ringo Starr, who lived in a different district but was drawn here, like thousands others, remembers: ‘… fairground music, and Frankie Lane and millions of people around and "Ghost Riders in the Sky"’.Footnote123 There was Calderstones Park, created from the estates of two nineteenth-century magnates and containing a lake and tree-line driveway created in the 1930s as a government-funded unemployment relief scheme.Footnote124 Theodora Cochrane remembers, ‘To us it was the countryside. No fancy attractions – just fields, trees, the lake, the old oak, the 'Echo Walk’ as we called it and the patch where the pet animals were buried with their little headstones’.Footnote125 As well as the park blocking the advance of terraced housing, a range of semi-detached dwellings grew southwards, with gardens front and back, laid out in attractive formations of curved roads and cul-de-sacs. Michael Hill recalls, ‘I was fortunate to live at the better end [of Dovedale Road] …houses set well back from the pavement… neat privet hedges or modest walls of brick or decorative stone. All the houses had long gardens at the rear, as did those in the road behind creating a large green expanse with plenty of light and air’.Footnote126 In a neighbouring block, the space encapsulated between the houses was given over to a recreation ground with a tennis court. Hill recalls himself and his young friends starting fires in the long grass on dry summer days, and, with Lennon among the group, being chased off the nearby university playing fields when spotted playing near the deep pools of water.Footnote127

The lyrics

McCartney has said, ‘I love Liverpool, every street has a memory’,Footnote128 and he gave the specific example of a line from the song ‘A Day in the Life’: ‘I would write songs about it [my earlier life] and then this memory here is “Got up, got out of bed, dragged the comb across my head”, that’s me running late for the bus’.Footnote129 For McCartney, a suggestion that ‘something of childhood’ be put into Beatles songs,Footnote130 became in ‘Penny Lane’ his clear memory of a view from the top deck of a Liverpool corporation bus. This included certain vivid images, described as ‘photographic detail’ and ‘couched in the primary colours of a picture book, observed with the shyness of a gang of kids straggling home from school’.Footnote131 The words captured forever a 1950s scene of Penny Lane that itself was reflecting the changing times. There was now a motor engineer, fish and chip shop, several confectioners and a snack bar.Footnote132 There were other cafes in neighbouring streets, notably the Old Dutch, which played a part in the 1950s’ rock and roll revolution with its juke box and pinball machine in a back room, and its clientele of teddy boys or ‘teds’.Footnote133 The cafe was situated not far from where Lennon and his first wife lived in a tiny flat and Lennon mentioned the Old Dutch in his original draft of ‘In My Life’.Footnote134 Indicating the changing times, Bioletti the barber by 1954 was employing Liverpool’s only female barber and a ‘stylist’– the new term for a hairdresser who could create film-star fashions for the clientele.Footnote135 Ann Carlton remembers the laundry run by George Leong where her solicitor father, who had a senior role in the town clerk’s department, sent his collars to be starched. In his office uniform of suit and bowler hat, her father was marked out as a ‘white-collar’ worker and working-class boys would shout impertinent comments at him, reminiscent of similar treatment received by the imagined banker in McCartney’s lyrics: ‘… children laugh at him behind his back’.Footnote136 Ann Carlton recalls: ‘My father saw the funny side of many things but he failed to share the boys’ sense of humour on that’.Footnote137 In Smithdown Place there were two banks and Betty Mullineux remembers her father withdrawing money in order to buy the family’s first television set in 1953, being one of the many who bought a television to watch the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, marking the enormous step forward in broadcast technology.Footnote138 Stan Williams recollects a teenage friend in her cadet nurse uniform, selling Remembrance Day poppies to travellers in the bus shelter.Footnote139 The roads around Smithdown Place were busy. On a weekday morning there would be school children walking to school with their mothers or cycling with perhaps two children sharing a ride with one balancing on the crossbar.Footnote140 Some would be using public transport and McCartney can remember first noticing Lennon with trepidation: ‘This ‘ted’ would get on the bus’, he recalls. ‘I wouldn’t stare at him too hard in case he hit me’.Footnote141 McCartney first met George Harrison on a bus too.Footnote142 There were thus a multitude of sights that McCartney could have depicted: the dairy cows or shoppers, Sefton Park fair or hedge-lined gardens, traffic or pedestrians. He chose to use the barber, the nurse, a banker and the bus shelter. A fireman features in the song too, and McCartney passed a fire station every time he caught a bus from his home to Penny Lane.Footnote143

Lennon’s response to the prompt to put childhood into his songs began with his first draft of ‘In My Life’, an imagined bus journey from Mendips, along Menlove Avenue and onwards to the docks. He included passing by the empty tram sheds near Smithdown Place which had given way to buses.Footnote144 Originally sounding ‘haphazard’ and ‘unwieldly’,Footnote145 Lennon said that he was trying to write clever lyrics but decided to abandon that initial draft. ‘Then I laid back’, he recalled in 1980, ‘and these lyrics started coming to me about the places I remember’.Footnote146 In the first stanza he accepts that some locations have changed and several have gone completely. In the second verse he refers to people, some of whom are dead. These are likely to be his dear uncle George, married to Mimi, and Lennon’s friend Stuart Sutcliffe who played bass in the Beatles before McCartney and who died the year before the Beatles hit the big time.Footnote147 It may also include Lennon’s beloved pet dog which Mimi put to sleep in a cruel act of control which Pete Shotton said was ‘one of the few times I saw John cry’.Footnote148 But no doubt at the heart of this lyric is Lennon’s mother Julia. Her death in a road accident in the summer of 1958 on Menlove Avenue, just outside Mendips, is a tragedy that has been dissected, discussed and debated by countless writers, Beatles scholars and Lennon himself for its deep and long-lasting impact and influence on the teenager and later lyricist.Footnote149

‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, with the letter ‘s’ added to the name of the house, appears at first to be a return visit to a place of youthful pleasure, inviting the listener to join him on the journey, be shown around and play in the trees. However, Lennon explained that just as Magritte’s painting of a crescent moon inspired the musical 'A Little Night Music' but had nothing to do with the plot, so did the mansion Strawberry Field inspire his song but be unconnected to the content. He said, ‘I just took the name, it had nothing to do with the Salvation Army, as an image’.Footnote150 Said by Ian MacDonald to be lyrics pursuing sensations too confusing, intense or personal to articulate, and a study of uncertain identity tinged with the loneliness of a solitary rebel,Footnote151 the song has captivated and intrigued millions of people the world over. Lennon’s ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, has a clear connection to Lewis Carroll’s [Alice] Through the Looking Glass,Footnote152 and thus achieves Lennon’s long-time aim of ‘writing an Alice’.Footnote153 In ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, Lennon opens a door into his past, enabling enthusiasts to push through and explore the landscape with the help of other sources. We are reminded of entering the different worlds of Carroll’s literary creations and thus Lennon once again achieved his ambition of writing an Alice.

Discussion and conclusions

This study of a part of Liverpool that has become one of the most famous urban areas in the world adds to the historiography of memory, landscape and suburban studies. The investigation of location has enabled observation of class differentials and of the border between pastoral and metropolitan landscapes. It has provided context for three popular songs of enormous cultural significance, and by trawling memories the article has populated the past with real people and real experiences and has used these recollections to help give a framework to the song narratives. It has been shown how the new suburb captured old characteristics including fields, boundaries and footpaths, and converted them into estates and roads. Here we saw palimpsest with those ancient features visible to the initiated – on maps, in memories, captured in newspaper reports, local ephemera and in the lyrics themselves. As the songs’ contents have such vivid and resonant geographical features that can be so easily identified, Penny Lane and Strawberry Field have become cultural icons and part of the tourist trail.Footnote154 There are bus tours around Liverpool that visit these two key locations and the Salvation Army has established a visitor centre in the grounds of the mansion. Strawberry Field was demolished years ago but an old photograph on a glass plate has been cleverly placed with a bench positioned such that when seated, one can look up and see the house seemingly in situ (). This is an example of the concept that I am calling ‘inverse palimpsest’, or the old purposefully superimposed onto the new, and there are other examples of this around the city and on a tourist itinerary in which images of the young Beatles are superimposed and applied to a modern plan (). It is remarkable that the changing map which charted the growth of the suburb contains, in this twenty-first century version, pictures and evocations of the main subjects of this article. The past is of course widely visible all around Liverpool as it is in most other towns and cities. It can be glimpsed in many ways lurking under the present, for example in old field patterns forming the alignment of streets of Victorian terraced housing. Yet what is now happening in Liverpool goes beyond this, to inverse palimpsest as the effects of the Beatles and the echoes of their local history are superimposed upon the modern Merseyside landscape to alter it and create a new identity, touristic cartography and present-day experiential reality. One can think of other examples of inverse palimpsest – so-called ‘living museums’ for example – which place old townscapes or cobbled-together rural buildings onto modern sites so that a visitor can enter a recreated environment. However, the siting of mid-twentieth century features connected to the Beatles onto present-day Liverpool is one of the most striking examples of the concept of inverse palimpsest in twenty-first century operation.

Figure 11. Old photograph of Strawberry Field near the Salvation Army visitor centre. Photo: author.

My final point links childhood to adult creativity. Gaston Bachelard was convinced that the childhood home was more than a repository for memories. Bachelard’s focus is on a child’s house with rooms, cellars and secret places leading to future, adult creations, which are grown-up versions of the younger self’s daydreams.Footnote155 I propose that his analysis also applies to the wider environment experienced by the child. In McCartney and Lennon’s case this is the streets, parks, shops, Penny Lane and Strawberry Field of the 1940s and 50s which led directly to the most remarkable of twentieth-century songs – part of the Beatles phenomenon and legacy.

Acknowledgement

I thank Tim Holmes for his enthusiastic and generous sharing of memories of Penny Lane and of John Lennon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rachael Jones

Rachael Jones is a research fellow at the University of Leicester and a tutor with the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. She has published widely on landscape, crime and family history. Email: [email protected]

Geolocation information: Liverpool; Northern England.

Notes

1 See also ‘Streets of London’ by Ralph McTell; ‘Waterloo Sunset’ by the Kinks; ‘San Francisco’ by Scott McKenzie; ‘Ferry across the Mersey’ by Gerry and the Pacemakers and ‘Fog on the Tyne’ by Lindisfarne.

2 For example, Ruth Hamilton, Daughters of Penny Lane (London, 2017) and Katie Flynn, The Girl from Penny Lane (Bromley, 2011). Memoirs include Stan Williams, Penny Lane is in my Ears and in my Eyes (Cambridge, 2008); Ann Carlton, Penny Lane: Memories of Liverpool (Borth, 2017).

3 See comments in Robert J. Kruse, ‘The Beatles as place makers: narrated landscapes in Liverpool, England’, Journal of Cultural Geography, 22:2 (2005), 89.

4 Adam Menuge, Ordinary Landscapes, Special Places: Anfield, Breckfield and the Growth of Liverpool’s Suburbs (Swindon, 2008).

5 Stephen Daniels, ‘Suburban pastoral: ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ and sixties memory’, Cultural Geography, 13 (2006), p. 28. See also R. Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London, 2012).

6 Janet Donahoe, Remembering Places: A Phenomenological Study of the Relationship Between Memory and Place (Washington, 2014), 25.

7 Eleanor Ratcliffe & Kalevi M. Korpela, ‘Memory and place attachment as predictors of imagined restorative, perceptions of favourite places’, Journal of Experimental Psychology, 48 (2016), 121.

8 John Higgs, Love and Let Die: Bond, the Beatles and the British Psyche (London, 2022), 8.

9 William J. Glover, Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City (Minneapolis, 2008).

10 See comments in Paul McCartney and Jill Lepore, 1964 Eyes of the Storm (London, 2023), 21.

11 In the mid-twentieth century Penny Lane was reassigned to the neighbouring district of Mossley Hill.

12 Victoria County History, 3 (1907), 111; Kelly & Co., Post Office Directory of Lancashire (London, 1858), 900 & map inside front cover.

13 Ackerman’s panoramic map of Liverpool, https://historic-liverpool.co.uk/old-maps-of-liverpool/(viewed 2 April 2023).

14 Kelly & Co., Post Office Directory of Lancashire (London, 1858).

15 Property sales, Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser, 29 August 1854; ‘Death from a Gunshot Wound’, Liverpool Mail, 28 January 1843.

16 ‘Country News’, Northampton Mercury, 5 August 1797.

17 ‘Sales by Auction’, Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser, 7 February 1805; ‘To be sold by ticket’, Liverpool Standard and General Advertiser, 16 May 1834; ‘Timber to be sold by ticket’, Liverpool Standard and General Advertiser, 1 February 1833.

18 ‘Wavertree Grange’, Liverpool Albion, 28 May 1828; ‘Country Residences’, Liverpool Mercury, 5 June 1835.

19 Sari Maenpaa, ‘Combining business and pleasure? Cottonbrokers in the Liverpool business community in the late nineteenth century’, in Trade, Migration and Urban Networks in Port Cities, c. 1640–1940, ed. A. Jarvis and R. Lee (Liverpool, 2008), 157–8.

20 Kelly, Post Office Directory (1858), 900.

21 ‘Bishop Eton Monastery’, https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk (viewed 10 April 2023).

22 National Census (Wavertree), 1851.

23 National Census, 1851; ‘Stealing game’, Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser, 29 August 1834.

24 National Census, 1851 (Wavertree).

25 https://www.ribapix.com/Hill-Side-or-Hillside-House-Wavertree-Liverpool-perspective-from-the-park_RIBA85293# (viewed 8 May 2023).

26 ‘Wavertree tithe barn and yard’, Liverpool Mail, 13 February 1858. See also comments about transport provision in E.K. Stretch, South Lancashire Tramways Company, 1900–1958 (Rochdale, 1972), esp. chapter 1.

27 Mike Chitty & David Farmer, Images of Britain: Wavertree (Stroud, 2013), 26.

28 ‘Wavertree’, Liverpool Mail, 3 February 1844; ‘Spacious mansion near Liverpool’, Liverpool Standard and General Commercial Advertiser, 7 October 1842.

29 National Library of Scotland Online Ordnance Survey map archive, https://maps.nls.uk (viewed 2023), map ref. Lancashire sheet CXIII.

30 John Belchem, Irish, Catholic and Scouse: The History of the Liverpool Irish, 1800–1939 (Liverpool, 2007).

31 National Library of Scotland Online Ordnance Survey map archive, https://maps.nls.uk (viewed 2023), map ref. Lancashire sheet CXIII NE.

32 See Stephen Caunce, ‘Mechanisation and society in English agriculture: The experience of the North-East, 1850–1914’, Rural History, 17:1 (2006), 23–45. See also comments in W. Alan Armstrong, ‘The Countryside’ in The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750–1950, ed. F.M.L. Thompson, 1 (2008), 113–4.

33 ‘Hillside House estate’, Liverpool Albion, 6 July 1857.

34 Barrington Road, Claremont Road, National Census (1911).

35 ‘House for sale, Barrington Road’, https://www.purplebricks.co.uk/property-for-sale/3-bedroom-terraced- house-liverpool-1116860 (viewed 25 April 2023); ‘Unfurnished houses to let’, Liverpool Mercury, 29 October 1892. See also Ordnance Survey large scale town plan map (1891), Liverpool – Lancashire CXIII.3.10.

36 Hawarden Avenue, National Census (1911).

37 Carlton, Penny Lane and All That, 34.

38 See Gian Luca Amadei, ‘The evolving paradigm of the Victorian Cemeteries: Their emergence and contribution to London’s urban growth since 1833’, PhD thesis (2014), University of Kent (online), especially 98–108; ‘Consecration of the Toxteth Park Cemetery’, Liverpool Daily Post, 10 June 1856.

39 https://www.workhouses.org.uk/ToxtethPark (viewed 18 April 2023).

40 ‘Toxteth and women guardians’, Liverpool Mercury, 19 September 1899. Sir Thomas was a descendant of slave traders and his father received compensation in 1835 for the loss of slaves following abolition (‘Hardman Earle’, 1851 National Census; see for example Legacies of British Slavery, claim ref. Antigua 265, https://www. ucl.ac.uk/lbs/claim/view/128 (viewed 18 April 2023). He was given his baronetcy for services to the Liberal Party.

41 Jack Maddox, In the Shelter of Each Other: Growing up in Liverpool in the 30s and 40s (Stroud, 2008, 2009), 9.

42 ‘Richmond Lodge’ in 1911 National Census summary book, Holy Trinity, Wavertree.

43 Alice Butler-Warke, ‘Foundational stigma: Place-based stigma in the age before advanced marginality’, British Journal of Sociology, 71:1 (2020), 140–152.

44 Ordnance Survey town plan of Liverpool, ref. Lancashire CXIII.3.8.

45 See Register of electors, Little Woolton Ward, Polling District MQ (1946), Liverpool Archives.

46 ‘Sales by auction’, Liverpool Albion, 27 September 1869.

47 George Warren’s home address given in Electoral Roll (1876), Liverpool polling district 13, Castle Street ward.

48 ‘Land, buildings, etc to be sold – Beaconsfield-Road, Woolton’, Liverpool Echo, 8 April 1884. See also George Warren’s entry in the 1911 National Census in which he has given the number of rooms as 32.

49 1893 25" Ordnance Survey map.

50 National Census, 1901 and 1911.

51 For example, ‘Servants wanted’, Liverpool Daily Post, 13 January 1911; P. Sutherland, ‘Sectarianism and evangelicalism in Birmingham and Liverpool, 1850–2010’, in Protestant-Catholic Conflict from the Reformation to the Twenty-First Century: The Dynamics of Religious Difference, ed. J. Wolffe (London, 2013), 135.

52 ‘The papers of Andrew George Kurtz (1824–1890)’, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk (viewed 30 April 2023).

53 ‘The Wavertree children’s rest’, Liverpool Mercury, 19 June 1900.

54 National Census, 1901 and 1911.

55 National Census, 1911.

56 ‘Lord mayor’s treat for poor children’, Liverpool Evening Express, 8 July 1903.

57 ‘Estate of the late John Karran Esq’, Liverpool Daily Post, 24 February 1902.

58 National Census, 1911 – Catherine and Nora Colvin; Joseph William Milliken.

59 Mary Elizabeth Stanley’s (Mimi’s) baptismal record, St James’s Church, Toxteth Park, 23 May 1906; Annie Georgina Stanley’s baptismal record, St Peter’s Church, Liverpool; George Ernest Stanley, 1891 National Census.

60 See comments in Sally Sheard, ‘Profit is a dirty word: The development of public baths and wash-houses in Britain, 1847–1915’, Social History of Medicine, 13:1 (2000), 63–86, esp. 64 & 71. See also James Newlands, Report on The Establishment and Present Condition of the Public Baths and Wash-Houses in Liverpool (Liverpool, 1856); James Allanson Picton, Memorials of Liverpool Historical and Topographical, 2 (1875), 275.

61 Brewer & Wyllie’s Bird’s Eye View of Liverpool, https://historic-liverpool.co.uk/old-maps-of-liverpool (viewed 25 August 2023). See also descriptions of tenements ‘in the shadow of Liverpool Cathedral’ in Williams, Penny Lane, 59.

62 Michael A. Hill, John Lennon: The Boy Who Became a Legend (Louisiana, 2013), 33; Craig Brown, One, Two, Three, Four: The Beatles in Time (London, 2020), 23; Bob Spitz, The Beatles: The Biography (Boston, 2005), 19.

63 ‘Cheap houses on easy terms’, Liverpool Echo, 8 December 1916.

64 Charles Bouren, 13 Newcastle Road, National Census, 1911.

65 Chitty & Farmer, Wavertree, 77.

66 Carlton, Penny Lane and All That, 19.

67 Carlton, Penny Lane and All That, 47–48, 175.

68 See for example, ‘Wavertree Hall Estate’, Liverpool Albion, 12 December 1842; Maenpas, ‘Combining business’, 160.

69 Kelly’s Post Office Directory of Lancashire, Liverpool and Manchester (1858), 902; Kelly’s Post Office Directory of Lancashire, Liverpool and Manchester (1873), 868.

70 ‘Encircling Liverpool by tram’, Liverpool Mercury, 10 January 1901; ‘Liverpool electric trams’, Liverpool Mercury, 3 December 1900; ‘Electric car collision at Wavertree’, Liverpool Evening Express, 6 August 1901. See also Stretch, South Lancashire Tramways, 9.

71 Elizabeth Amann, ‘The omnibus as social observatory’, Orbis Litterarum, 73:6 (2018), 533.

72 For example, ‘Yesterday’s police court’, Liverpool Mercury, 31 July 1900; ‘Tram conductor assaulted’, Liverpool Mercury, 15 September 1904.

73 ‘Embezzling tram fares: Conductor sent to prison’, Liverpool Mercury, 2 February 1904.

74 ‘Electric car collision at Wavertree’, Liverpool Evening Express, 6 August 1901.

75 ‘Yesterday’s Police Courts: Liverpool–Prosecutions by The Tramways Committee’, Liverpool Mercury, 18 October 1900.

76 Paul McCartney’s original manuscript, https://www.beatlesbible.com/songs/penny-lane (viewed 3 October 2023).

77 The tram car sheds are shown in the background. They are marked at the northernmost point of Figure 5.

78 Carlton, Penny Lane, 37–38.

79 Wavertree Community Association year books, 1948–1958, Liverpool Archives.

80 ‘Band Concert’, Liverpool Echo, 28 July 1951.

81 Williams, Penny Lane, 86–88.

82 Williams, Penny Lane, 160–162; Hill, John Lennon, 101.

83 http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/Liverpool/PavilionTheatreLiverpool.htm (viewed 25 August 2023).

84 Williams, Penny Lane, 202; Hill, John Lennon, 79.

85 Wavertree Community Association, Liverpool Echo, 30 June 1950.

86 Ian Rotherham has examined how old trees can indicate past landscapes and Paige Peyton has studied ‘ghost towns’ as a way of investigating abandonment: Ian Rotherham, ‘Searching for shadows and ghosts in the landscape’, Arboricultural Journal, 39:1 (2017), 39–47; Paige Margaret Peyton ‘The Archaeology of Abandonment’, PhD Thesis, Leicester University, published online (2012).

87 ‘Original Names’, Liverpool Daily Post, 19 July 1938.

88 See Jeremy W. R. Whitehand & M. H. Carr Christine, ‘The creators of England’s inter-war suburbs’, Urban History, 28:2 (2001), 218–234 (focusing on Birmingham); Jane Humphries, ‘Inter-war house building, cheap money and building societies: The housing boom revisited’, Business History, 29: (1987), 325–345. Michael Stratton and Barrie Trinder make the point: ‘One road or one suburb is to the eye of the stranger identical to another road or another suburb … Ruislip is indistinguishable from Cowley; Mapperley might as well just be in Bristol or Nottingham’, Michael Stratton and Barrie Trinder, Twentieth-Century Industrial Archaeology (Abingdon, 2000, 2013), 121.

89 Stratton & Trinder, Industrial Archaeology, 21.

90 ‘Liverpool Corporation Committees: Tramways – A new belt route’, Liverpool Daily Post, 21 October 1909.

91 Author’s interview with Tim Holmes, 25 August 2023. Recording deposited at Liverpool Record Office.

92 Williams, Penny Lane 58.

93 See a report of a private telephone being used to report a crime: ‘Chase and capture of fugitive’, Liverpool Echo, 22 January 1931; ‘A brief history of the telephone’, www.italktelecom.co.uk (viewed 4 August 2023); John Liffen, ‘Epsom: Britain’s first public automated telephone exchange’, International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology, 82:2 (2012), 210–32, esp. 227–229. See also comments in Carlton, Penny Lane, 37.

94 ‘Wallace found guilty and sentenced to death’, Liverpool Echo, 25 April 1931.

95 1939 Register for nos. 1–100 Menlove Avenue.

96 Browne, One, Two, Three, Four, 22. Lennon’s half-sister gives astonishing details about Mimi’s marriage in Julia Baird, Imagine This: Growing up with my Brother John Lennon (London, 2007), esp. 104–109.

97 Stephen Daniels, ‘Suburban pastoral’, 28–54; Ernest Brideson Harrop, 1939 Register.

98 ‘Liverpool’s great circular boulevard’, Liverpool Daily Post, 22 March 1910.

99 ‘Verdict of manslaughter against motor cyclist’, Runcorn Daily News, 29 July 1921; ‘Woolton Rector’s Death’, Liverpool Daily Post, 18 March 1941.

100 ‘Accident in enclosed tram track: Wavertree man’s fatal injuries’, Liverpool Daily Post, 19 July 1938.

101 ‘Liverpool meat imports’, Belfast Newsletter, 15 July 1935.

102 ‘Stolen diamond Rings’, Liverpool Echo, 5 September 1935.

103 ‘Bootle man on house breaking charges’, Liverpool Echo, 12 January 1932.

104 ‘The Salvation Army: Bequests for women’s and children’s homes’, The Times, 7 November 1913; ‘Large bequest to the Salvation Army’, The Times, 4 July 1914; Miss Fowler made several large bequests through her lifetime. See for example, ‘Opening of a new NCHO hospital’, Cheshire Observer, 19 June 1937.

105 ‘At Strawberry Field’, Liverpool Daily Post, 14 July 1936.

106 See for example Baird, Imagine This, 32–49.

107 Baird, Imagine This, 22.

108 Electoral roll: Wavertree division, Allerton ward, polling district MR and Wavertree division, Wavertree ward, District MG (1945).

109 Roger Appleton (Dir.), Looking for Lennon (Evolutionary Films, 2018). See also G. Giuliano, Lennon in America, 1971–1980 (New York, 2001), 7–28.

110 Hill, John Lennon, 42.

111 BBC TV, Michael Parkinson interview with Paul McCartney (3 December 1999).

112 Pete Shotton and Nicholas Schaffner, John Lennon In My Life (London, 1983), 28–30.

113 PYX Productions, The Beatles (London, 1964), 4.

114 ‘Salvation Army Fete’, Liverpool Daily Post, 5 June 1950.

115 ‘Penny Lane loses its identity’, Liverpool Echo, 27 February 1967.

116 David Sheff & G. Barry Golson, The Playboy Interviews with John Lennon and Yoko Ono (Sevenoaks, 1982), 132.

117 St Peter’s Church, Woolton, Richard Pollard & Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West (Yale, 2006), 507; St Barnabas Church, Smithdown Place, https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk (visited 2 October 2023).

118 ‘Woolton Parish Church’, Liverpool Echo, 23 December 1957; Bank of England, ‘Inflation Calculator’, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator (viewed 26 September 2023).

119 ‘Liverpool’s forgotten factory where generation of staff loved to work’, www.liverpoolecho.co.uk (viewed 3 October 2023). For analysis about the origins of the lyrics of Eleanor Rigby see P. Norman, Paul McCartney: The Biography (London, 2016), 246. See also, Paul McCartney, The Lyrics: 1956 to the Present (London, 2021, 2023), 119–123.

120 National Censuses 1891–1911. Note that the numbering of houses in Vale Road has changed. Woods’s childhood home was no. 8 but is now no. 225.

121 ‘Sefton Park, Liverpool’, https://historicengland.org.uk (viewed 26 September 2023).

122 Williams, Penny Lane, 81.

123 Williams, Penny Lane, 288.

124 ‘Caldestones Park heritage trail’, https://trails.thereader.org.uk (viewed 3 October 2023).

125 ‘These wonderful memories of Calderstones Park will make you feel like a kid again’, www.liverpoolecho. co.uk (viewed 3 October 2023).

126 Hill, John Lennon, 19.

127 Hill, John Lennon, 74 & 98.

128 Michael Parkinson interview with Paul McCartney (1999).

129 CBS, Carpool Karaoke with Paul McCartney (21 June 2018).

130 Sheff & Golson, Interviews, 129.

131 Norman, Paul McCartney, 258; Ian MacDonald, Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties (1994, London, 2005), 221–2.

132 Hill, John Lennon, 35.

133 Jon Pennington, ‘Old Dutch Cafe near Penny Lane’, www.quora.com (viewed 3 October 2023); ‘Lost shops and businesses, Smithdown Road’, www.liverpoolecho.co.uk (viewed 23 July 2023).

134 John Lennon’s original handwritten lyrics to the song ‘In My Life’, as displayed at the British Library’s 2012 exhibition ‘Writing Britain: From Wastelands to Wonderlands’, https://commons.wikimedia.org (viewed 4 October 2023).

135 Williams, Penny Lane, 254; ‘Jean Johnson keeps you posted’, Liverpool Daily Post, 29 April 1950.

136 Paul McCartney’s original manuscript, https://www.beatlesbible.com/songs/penny-lane (viewed 3 October 2023).

137 Carlton, Penny Lane, 44–45.

138 Personal recollection, www.facebook.com/LiverpoolPicturebook (viewed 12 August 2023); A. Web, ‘Two Coronations’, www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc (viewed 10 October 2023).

139 Williams, Penny Lane, 255–6.

140 Personal communication with Tim Holmes, 2 October 2023. Copy of the correspondence deposited at Liverpool Record Office.

141 Norman, Paul McCartney, 64.

142 Johnny Dean (ed.), The Beatles Book, 2 (London, 1963), 10.

143 See McCartney’s comments in McCartney, Lyrics, 400–401.

144 Sheff & Golson, Interviews, 151; Carlton, Penny Lane, 2.

145 MacDonald, Revolution, 69.

146 Sheff & Golson, Interviews, 30.

147 Lesley-Ann Jones, The Search for John Lennon: The Life, Loves and Death of a Rock Star (New York, 2020), 61–63 & 119; Philip Norman, George Harrison: The Reluctant Beatle (London, 2023), 142–3.

148 Shotton & Schaffner, John Lennon, 38.

149 For example, Jones, The Search, 83–85; Appleton, Looking for Lennon; Higgs, Love and Let Die, 233–240; Hill, John Lennon, 242–245; Elizabeth. Thomson and David Gutman (eds), The Lennon Companion: Twenty- Five Years of Comment (Basingstoke, 1987), 6–7, McCartney, Lyrics, 451.

150 Sheff & Golson, Interviews, 131.

151 MacDonald, Revolution, 216. See also David J. Pannell, ‘Quantitative analysis of the evolution of the Beatles’ releases for EMI, 1962–1970’, Journal of Beatles Studies, 1 (2023), 67.

152 Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass (London, 1871). See MacDonald, Revolution, 240 and BBC TV, ‘Sgt Pepper’s Musical Revolution with Howard Goodall’ (23 June 2017). See also Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (London, 1865). For a discussion of Alice, see R. Douglas-Fairhurst, The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland (London, 2015).

153 Shotton & Schaffner, John Lennon, 33.

154 ‘The Beatles in Liverpool’, Visit Liverpool, https://www.visitliverpool.com/things-to-do/attractions-in-liverpool/ the-beatles (viewed 17 October 2023). See comments in Clare Kinsella & Eleanor Peters, ‘There are places I remember’, Journal of Beatles Studies, 1 (2022), 56–58.

155 G. Bachelard, Poetics of Space (Boston, 1994), 3–37 & esp. 57.