ABSTRACT

Transition in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) since 1989 has received much attention from various academic disciplines. However, the relationship between trust and corruption in the CEE context remains largely unaddressed. Therefore, we explore trust and corruption in the context of the Czech Republic via interviews with a group of new generation managers, who gained their business experience after the 1989 Velvet Revolution. We inquire about the nature of trust and corruption, and their relationship, in contemporary Czech society and business. The analysis highlights that the previously theorised dynamics between trust and corruption, often attributed to the low levels of social capital, may in fact be symptomatic of deeper issues. We find suspicion, pessimism, cynicism, and apathy, stemming from the country’s history, as the cause. However, hope is provided by the prospect of generational change and exposure to more transparent agents and environments in both societal and business terms.

1. Introduction

Studies of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) often focus on transition from Communist regimes to open, democratic systems. The unique shift from a socialist to a capitalist system, which is characteristic of the CEE transition, is one of the drivers of the continued interest in the region. However, most studies have focused on economic and political developments and studies of the important relational and societal transition remain sparse in comparison. Some particularly important questions were raised in the early stage of the CEE transition by Bowser (Citation2001) and Rose-Ackerman (Citation2001). Their concern was not as much about the economic and political, but about the societal, forces that were at play because of the former Communist regime and the behaviours it instilled. Social capital, and corruption and trust, were of particular concern.

Questions pertaining to social capital and societal changes are important. Rose-Ackerman (Citation2001) highlighted trust and corruption as the main phenomena that were going to determine the success of the CEE transition. The relationship between trust and corruption was said to be crucial, due to it encompassing some of the socio-political mechanisms of the former Communist regime (Bowser, Citation2001; Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001). The presence of strongly bonded social groups, which led to a highly fractionalised society, was one of them. Such fractionalisation is a theoretical paradox in view of the egalitarian ideology of the countries of the former Communist bloc. Some of the trust and corruption literature suggests that inequality leads to low levels of trust, social capital, and transparency (Morris & Klesner, Citation2010; Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005). However, there are also studies that identify the different nature of the interplay between trust and corruption in the artificially created egalitarianism of the societies of CEE (Bjørnskov, Citation2003a; Letki & Evans, Citation2005; Mishler & Rose, Citation2001). What they fail to say is how or why the trust and corruption dynamic in these societies is so different.

However, we know that in social trust, fairness often matters more than homogeneity (You, Citation2012). This is an important indication of why many CEE societies remain somewhat fractionalised. Corruption is essentially a sign and a by-product of a lack of fairness. With many CEE countries struggling to tame their corruption levels (Zakaria, Citation2012), the possibility of corruption eroding trust, and by extension, social capital is high. There are different ways in which corruption can be tackled, and the literature offers some solutions to reducing corruption levels. Collective action problem solving has been said to be particularly promising (Bjørnskov, Citation2011; Svendsen, Citation2003). However, the academic literature does not offer many insights into how the presence of this mechanism could help tackle corruption and improve trust in CEE.

Collective action problem solving is a particularly interesting phenomenon that requires a good level of social capital. We could see it at work in CEE in the Ukrainian refugee crisis when many CEE countries and individuals opened their homes to people fleeing the war (The Economist, Citation2022). The refugee crisis highlights the importance and effectiveness of the collective action mechanism very clearly. It also reminds us that such mechanisms are available in CEE, but not necessarily (fully) deployed. CEE societies may be able to deploy the collective action mechanism to overcome obstacles in times of crisis. However, the question is whether collective action and similar ‘assets’ are present in a society at more settled times. And if they are, then why are they not employed to tackle some of the issues, such as corruption, that CEE faces. Corruption is a particularly good issue to explore, because we cannot assume that people are unaware of or do not care about it. On the contrary, corruption is the source of much dismay in many CEE societies (EBRD, Citation2011; Møller & Skaaning, Citation2009; Obydenkova & Arpino, Citation2018; Transparency International, Citation2019; Zakaria, Citation2012). Therefore, a deep understanding of trust and corruption and some of its related mechanisms and their workings is needed.

It is important to note that some of the countries of CEE are no longer classed as transition economies (EBRD, Citation2011), but it does not mean that the former regime and its consequences have entirely disappeared. Indeed, the modern-day CEE is not free from its past. The older generation still remembers the Communist regime. The younger generation faces new challenges stemming from being brought up in a democratic environment tainted by the legacy of the former regime in the CEE collective memory (Kovalčíková & Lačný, Citation2016; Lyons & Kindlerová, Citation2016; Mihaylova, Citation2004; Rothstein, Citation2013). Therefore, some of the important questions raised by Rose-Ackerman (Citation2001), pertaining to the role of social capital and corruption in the CEE transition, may now be more relevant than twenty years ago.

The time is right to reflect on the transition process and to explore trust and corruption in depth. To do that, we reviewed the literatures on social capital, trust and corruption and the relationship between the two phenomena and the CEE transition process. Such a review enabled us to identify a significant gap in the literature in terms of a very limited knowledge of the interplay between trust and corruption in the region, and the perspective of the new generation of Central and Eastern Europeans. We aim to capture a combination of experiences from the cultural, socio-political, and business contexts. The Czech Republic has been selected due to its unique position ‘between East and West’ and its suitability will be explained below. Therefore, the overarching research question is: What is the nature of trust, corruption, and their relationship in contemporary Czech society and business?

The theoretical foundations of trust and corruption are introduced first. The transition context is discussed subsequently and the importance of studying trust and corruption in the Czech context – societal and business – is outlined. The research methodology and the findings are followed by a discussion and conclusions.

2. Trust and corruption theory

Studies of trust and corruption and social capitalFootnote1 became prominent at the turn of the millennium. Scholars identified that social capital can curb corruption (Bjørnskov, Citation2003a; Bjørnskov, Citation2011; Tonoyan, Citation2006; Uslaner, Citation2002), make institutions fairer for everyone (Bjørnskov, Citation2011; Fukuyama, Citation1995; Putnam, Citation1993; Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008; Uslaner, Citation2008a), lead to greater overall life satisfaction and happiness (Bjørnskov, Citation2003b), increase efficiency and the quality of business environments and organisations (Kramer & Tyler, Citation1996; Luo, Citation2002; Lui et al., Citation2006), and help mobilise collective action problem solving (Ostrom, Citation1998; Rothstein, Citation2013; Uslaner, Citation2008b). Whilst it is not entirely reasonable or fair for trust to bear such a burden (Latusek & Cook, Citation2012), the evidence and the enthusiasm surrounding the argument concerning trust is convincing. There is, however, a counter-stance which expresses two concerns: first, just as trust enhances institutions, societies and political climates, so are these responsible for the generation of trust, i.e. there is an issue of assigning causality due to endogeneity (Chang & Chu, Citation2006; Latusek & Cook, Citation2012; Morris & Klesner, Citation2010; Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008; Serritzlew et al., Citation2014); and second, there is evidence of some of the negative effects of trust, with corruption and illicit economic and political practices at the top of the list (DiFalco & Bulte, Citation2011; Hatak et al., Citation2015; Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001; Tonoyan, Citation2006; Uribe, Citation2014).

Social capital posits a logical connection between corruption and social trust and provides a picture of how trust can be used negatively, and thereby possibly result in corruption (DiFalco & Bulte, Citation2011; Hatak et al., Citation2015; Uribe, Citation2014; Tonoyan, Citation2006). Similarly, studies of trust and corruption assume that for corruption to thrive, the agents involved need to trust one another as such a relationship is based on reciprocity which often requires trust – although such trust might simultaneously be tainted by suspicion (Uslaner Citation2002). It is at these opposing ends of the trust and corruption interplay that a possible paradox arises – trust may lead to corruption and corruption may promote trust. Whilst it is possible that the causality between trust and corruption goes in both directions, which is what, for instance, Tonoyan (Citation2006), Hatak et al. (Citation2015) and Denisova-Schmidt and Prytula (Citation2017) propose, the typology of trust sheds some light on this issue.

Trust typology and contextualisation are an important consideration in understanding some of the perplexing aspects and seeming ambiguities of the interplay between trust and corruption. The literature concerned with assigning causalities between trust and corruption generally distinguishes between particularised and generalised trust types. Generalised and particularised social trust are two distinct types of social trust which coexist in societies.

Particularised social trust, sometimes referred to as ingroup trust, is one that exists within relatively small groups of people with very strong but closed ties, such as family members. Such trust is characteristic of fractionalised, suspicious and/or hostile environments (Banfield, Citation1958), such as within totalitarian regimes, or secretive groups, such as the Mafia (Gambetta, Citation1993; Torsello, Citation2015). It is a form of bonded social capital based on kinship, similarity and familiarity and is strongly embedded within societies under the former Communist regimes. Indeed, it was developed and employed as a coping mechanism to navigate the structures of power and control during the Communist regimes (Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001; Kovalčíková & Lačný, Citation2016; Mihaylova, Citation2004). Social capital scholars have suggested that the high levels of particularised trust in CEE may have rooted out generalised trust almost entirely (Freitag & Traunmüller, Citation2009; Richey, Citation2010; Rothstein, Citation2000; Uslaner, Citation2002).

Generalised trust, on the other hand, refers to trust in people in general, the belief that others can be generally trusted not to act in such a way that would cause one any (intentional) harm. It is also referred to as bridging social capital due to its social cohesive properties. Berggren and Jordahl (Citation2006) equate generalised social trust to social capital. Glanville and Shi (Citation2020), for instance, further distinguish between the generalised and outgroup forms of trust. They conceptualise the generalised trust as a general belief in people which could be extended to ‘humanity’ and outgroup trust as a trust towards those outside one’s inner circle who can be described within certain parameters; for instance, people within a geographical, social, or a historical context. Both types are particularly relevant to the CEE context.

Studies of trust often find a significant connection between the different types. Delhey and Welzel (Citation2012) found that particularised trust is an important pre-requisite for generalised trust. Such finding is in line with a more anthropological view of trust creation, such as that of life-history and the dilemma of opening one’s inner circle to outsiders, which, from a historic perspective was an important decision (Welzel and Delhey, Citation2015). Whilst we can see an important effect of particularised trust on the creation of generalised trust in many societies, Glanville and Shi (Citation2020) found that the mechanism is not as strong in collectivist contexts. This finding is directly relevant to the context of the former Communist countries of CEE which were essentially collectivist societies. Concerns about the potentially harmful effect of particularised trust on the development of generalised trust can be observed amongst many transition and CEE scholars who have been particularly concerned about the combination of high particularised and low generalised and outgroup trust stocks hampering the CEE transition due to corruption that might spiral out of control (Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001; Svejnar, Citation2002; Vachudova, Citation2009; Zakaria, Citation2012; Zaloznaya, Citation2014). This may result in generalised trust and social capital not only remaining at low levels, but possibly spiralling down further as the result of increasing corruption, i.e. falling into what Uslaner (Citation2002) calls a trust and corruption vicious cycle.

Trust is a complex phenomenon, and so is corruption. It is due to these complexities and the bidirectionality of the two phenomena that capturing their relationship is not an easy, and perhaps not an entirely possible, task. However, these complexities prompt us to consider the role of context, such as the CEE. CEE countries have a complicated past, of which many still suffer, and trust is one of those attributes that have been particularly damaged during the Communist regime (Kopecek, Citation2010; Mihaylova, Citation2004). We must remember that traumatic experiences have a damaging, and often a long-lasting effect on trust (Alesina & La Ferrara, Citation2002). In some countries, including the Czech Republic, social trust either eroded further or was not nurtured during the transition to democracy, mostly due to path-dependency, inappropriate means of privatisation, and state capture (Myant & Smith, Citation2006; Møller & Skaaning, Citation2009). The CEE literature often finds the persistence of the former networks that developed during Communism and were seen as particularly harmful by society (Kopecek, Citation2010; Vaněk & Mücke, Citation2016). The perpetuation of these issues by media is not conducive to the rebuilding of trust either. Therefore, it is possible that such low trust might lead to a more general pessimism about developments in the region. These specificities of the CEE region highlight the importance of the consideration of the role of context when studying trust and corruption in CEE or, more specifically in the context of our study, the Czech Republic.

Most studies of trust and corruption, however, have not focused on the CEE context. The most common approach to investigating trust and corruption is by means of comparative studies which focus primarily on the macro level, claiming vicious cycles (Bjørnskov, Citation2003a; Chang & Chu, Citation2006; Habibov et al., Citation2017; Kubbe, Citation2013; Mauro, Citation1998; Rothstein, Citation2000; Uslaner, Citation2002; Obydenkova & Arpino, Citation2018; Wroe et al., Citation2013), social traps (Denisova-Schmidt & Prytula, Citation2017; Gillanders & Neselevska, Citation2018; Habibov et al., Citation2017; Platt, Citation1973; Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005; Tonoyan, Citation2006) or inferences (Bowser, Citation2001; Kubbe, Citation2013; Mauro, Citation1998; Rothstein, Citation2000; Morris & Klesner, Citation2010; Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008; Rothstein & Eek, Citation2009; Richey, Citation2010; Radin, Citation2013;, Rothstein, Citation2013; Semukhina & Reynolds, Citation2014; Sööt & Rootalu, Citation2012; Sapsford et al., Citation2019) as the mechanism of the relationship between trust and corruption. The general thesis behind the vicious cycle and social trap theories posits that corruption breeds mistrust which, in turn, breeds more corruption; and, similarly, generalised trust curbs corruption which, in turn, generates trust. The idea of inferences is, to some extent, similar but focuses at a more agential level and is braided with more internal conflict.

Two inferences have been proposed – negative and positive. The negative inference theory suggests that if one sees wrongdoing, such as corruption, one will think that everyone does it and that, to survive in such an environment, one needs to engage in the same. The positive inferences work in the same way but in the context of positive action, and thereby result in virtuous cycles which, in the case of trust and corruption, means that trust breeds more trust. Notably, these inferences are the underlying mechanism and determine the success of the collective action which highlights the importance of a group of people to achieve a common goal, such as reducing corruption (Svendsen, Citation2003, Vodrazka, Citation2009). When inferences made about others within the group, such as a country, are mostly negative, this will block the mechanism, and lead to vicious cycles, i.e. it will result in a social trap. On the other hand, when inferences are positive, which is associated with high levels of social capital and social trust, collective goals can be achieved via the collective action which will result in virtuous cycles (Ostrom, Citation1998, Rothstein, Citation2013).

The theories of inferences, vicious cycles, and social traps helped the development of the trust and corruption literature and enabled fast movement in the field, with studies testing the relationship and the causality between trust and corruption using large-scale data.Footnote2 These studies have resulted in evidence about the interplay between trust and corruption from different contexts. However, the contextual evidence is both helpful and problematic – partly because contextless generalisations prevail, and information on transition is sparse, but comments about the difference of the state and causes of trust and corruption in the transition context are many (Bowser, Citation2001; Bjørnskov, Citation2003a; Mishler & Rose, Citation2001; Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001; Uslaner, Citation2002; Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005; Tonoyan, Citation2006; Kubbe, Citation2013; Radin, Citation2013; Denisova-Schmidt & Prytula, Citation2017; Habibov et al., Citation2017). Indeed, the evidence pertaining to the CEE context suggests that the trust and corruption mechanism that one would expect based on hermeneutics and which we observe in studies of trust and corruption from non-CEE contexts is not in alignment with what is happening in the CEE region.

This lack of knowledge presents a threat to our understanding of the region and its development and socio-political mechanisms. This is a major gap due to the increasingly important role that these countries have in global economic, social, and political affairs, but also due to their integration with Western European countries. This means that CEE structures, networks, and mechanisms are integrating with the Western ones, and assuming their similarity (or a mere dissimilarity) might lead to potentially problematic circumstances and pose a threat to development and beneficial initiatives. These gaps in understanding present a research opportunity. Accordingly, this study aims to enhance our understanding of these issues via an in-depth analysis of the issue of trust and corruption in the Czech Republic – one of the most economically developed countries of CEE but one which experienced a particularly totalitarian Communist regime.

3. Trust and corruption in the Czech Republic

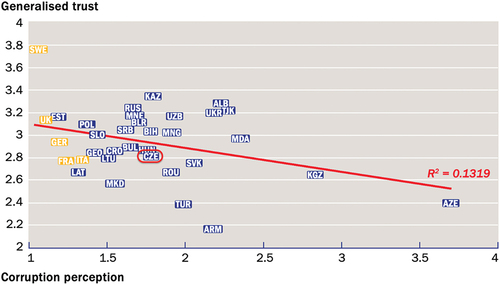

The Czech Republic, due to its unique socio-economic position in CEE, is an intriguing context for studying trust and corruption and understanding changes in the region. Its current political, economic, and social status are comparable to many Western European countries; yet, the country’s levels of trust, and social capital more generally, are low even in comparison with the other CEE countries (EBRD, Citation2011, Kovalčíková & Lačný, Citation2016, Transparency International, Citation2016). This is despite improvements in the country’s corruption levels (Transparency International, Citation2022). indicates the position of the Czech Republic in relation to generalised trust and corruption. Whilst there have been some further improvements in the country’s corruption levels which, according to the Corruption Perceptions Index, have gone up from 49 in 2012 to 56 in 2022 (Transparency International, Citation2022), the latest data from the 2017–2022 Wave 7 of the World Values Survey (WVS) indicated that only 36.8% believed that others can be generally trusted whilst over 62% believed that one needs to be careful when dealing with others (WVS, Citation2022).

Figure 1. Generalised trust and corruption in 2010Footnote3.

This situation posits some interesting questions to the inquiry into the trust and corruption dynamics, particularly to the more economic views of the phenomenon which suggest that the higher is the transparency and the quality of socio-economic life, the higher are the levels of trust (Bebbington et al., Citation2004; Baliamoune-Lutz, Citation2011; Berggren & Jordahl, Citation2006; Uslaner, Citation2008a; Woolcock, Citation1998). This has not been the Czech experience. Our study explores the specificities of the trust and corruption phenomenon in the Czech Republic by means of discussions with a new generation of managers.Footnote4 This generation of managers is particularly intriguing not only because of their upbringing and experience, but also due to their levels of mobility and emancipation, which are much greater than those of the older generations. Mobility, coupled with the political and economic openness of the Czech Republic, enables the exposure to different environments highlighted by Rose-Ackerman (Citation2001). Emancipation, which Welzel and Delhey (Citation2015) attribute to the freeing of oneself of close ingroup ties, which is what the relaxed socio-political environment following the 1989 Revolution enabled, is another area which makes these managers an important source of information. Given the focus on managers, we need to discuss some of the specificities of the country in terms of the level of social capital within its society and in its business environment.

3.1. Czech society

The Czech Republic shares a large part of its past with the other CEE countries. Of particular importance to the country’s social capital was the introduction of the StB (State Police) in 1945, which was used to spy on Czech citizens and protect the ideology of the Communist Party (David, Citation2003; Lizal & Kocenda, Citation2001; Semukhina & Reynolds, Citation2014). This not only resulted in citizens’ distrust of the police but also created a rift in society, resulting in high levels of suspicion, i.e. the opposite of trust, between people, including within families. The literature suggests that these views of the police are still prevalent (Crow et al., Citation2004, David & Choi, Citation2006, Kopecek, Citation2010, Lyons & Kindlerová, Citation2016), and some reports observe a perpetuation of these issues due to the entanglement of the Czech police in political scandals, including corruption (Kollmannová & Matušková, Citation2014, OECD, Citation2017).

However, more recent data highlight that the perceptions of police by Czechs seem to have improved considerably – the ESS (Citation2022) data suggest that trust in police has gone up to 6.5 in 2020–22 from 5 in 2010–13 when measured on a 10-point ascending scale. Additionally, the WVS (Citation2022) from 2022 confirms this trend with almost 70% respondents trusting the police. There is a possibility that the negative reports of corruption involving the police are attributed to the agents involved in those cases – mostly politicians. The ESS and WVS both find a considerably low trust in politicians and political parties – politicians scored 3.9 out of 10 (compared to the 6.5 scored by the police) in the latest ESS (Citation2022) and political parties were only trusted by approximately 20% in the latest WVS (Citation2022). Interestingly, the ESS found that the legal system has also improved in terms of the Czech citizens’ trust from 4.1 in 2010–13 to 5.8 in the 2020–22 wave. Additionally, the 2022 WVS found that over 50% respondents felt they could trust civil services. Such results further highlight that the Czech institutional environment is continuously improving. There is, however, an apparent issue with the Czech polity, which is still seen as fundamentally untrustworthy. Such views possibly reflect the political fragmentation which is, in part, caused by many populist movements, which are common in CEE (Lenik, Citation2024), and a relatively large number of political parties for a small country such as the Czech Republic (Bláha, Citation2023; Freedom House, Citation2023).

Some of the issues pertaining to the country’s political environment can explain the relatively low levels of social capital. Indeed, a large body of the literature on trust and corruption is concerned with the role of institutional trust as a basis for the creation of interpersonal and particularly generalised social trust (Chang & Chu, Citation2006, Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008, Morris & Klesner, Citation2010, Latusek & Cook, Citation2012, Serritzlew et al., Citation2014). Wave 7 of the WVS (Citation2022) results were very similar to those from the Life in Transition Survey report (EBRD, Citation2011) published over a decade ago. Over 62% people believed they had to be careful when dealing with others, a question used to approximate generalised social trust (WVS, Citation2022).

The WVS (Citation2022) responses regarding trust in one’s neighbourhood was generally more positive – nearly 80% suggested they trusted people in their neighbourhood. However, only 39% would trust people they have just met and with much less confidence. Additionally, there has been a significant level of distrust of other nationalities – approximately 53%. These results suggest that generalised trust was not particularly high, but that outgroup trust with the boundary of Czech nationals was less constrained. However, the results from the EBRD Life in Transition II report need to be mentioned here to raise caution about any premature optimism. EBRD (Citation2011, p. 43) found a significant disparity between real and hypothetical trust in one’s neighbours – whilst nearly 60% respondents said they trusted their neighbours, only about 20% believed that their wallet would be returned if it were lost.

Generalised and outgroup trust seem to remain problematic. Particularised, or ingroup, trust, however, seems to be high. The WVS (Citation2022) found that over 90% of respondents had high level of trust towards their family and nearly 90% in people they knew. Such a result, however, is not entirely surprising due to the country’s history of strongly bonded groups that helped people navigate the complexities, uncertainties, and often also dangers of the former communist regime, and the development of social capital which has also been highlighted by the early transition scholars (Bowser, Citation2001, Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001, Mihaylova, Citation2004). These results are very positive for particularised trust, but it seems that some level of uncertainty and possibly suspicion, which are detrimental to the development of generalised and outgroup trust, remain. This is interesting as particularised trust is sometimes seen as a prerequisite for generalised trust (Delhey & Welzel, Citation2012). However, there is also the issue of institutional trust and perceived fairness which was said to breed generalised trust (Rothstein, Citation2013) and is perhaps more important than ingroup trust in the Czech context where the importance of fairness, highlighted by You (Citation2012), is key.

The issue of institutions, political apparatus, and totalitarian history, including the StB and the erosion of the country’s social fibre is, however, only one part of the country’s problem with social capital. The other anomaly of the Czech context, and of CEE more generally, is its artificially induced egalitarianism – a factor which is often highlighted in studies of trust and corruption in this geographical region (Mishler & Rose, Citation2001, Rose-Ackerman, Citation2001; Bjørnskov, Citation2003a; Karklins, Citation2005; Letki & Evans, Citation2005; Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005). This is due to the literatures on trust and corruption and social capital suggesting that it is inequality that breeds distrust and leads to the triggering of mechanisms such as negative inferences and social traps (Platt, Citation1973; Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005; Rothstein, Citation2013). However, this was not the case in the Czech Republic, where corruption thrived in an ideologically egalitarian context.

The cause, contrary to the corruption experience of Western countries, was necessity, rather than greed (Svejnar, Citation1990; Lizal & Kocenda, Citation2001; Svejnar & Uvalic, Citation2013). Indeed, the exchange of favours and gifts, which could be considered corruption or bribery, were common tools for accessing scarce resources during the Communist era and in the early stages of the transition process (Lizal & Kocenda, Citation2001; Myant & Smith, Citation2006; Lyons & Kindlerová, Citation2016). This led to the development of close-knit ties and to many strongly bonded trust groups but was counterbalanced by the erosion of the country’s generalised social trust. It is therefore plausible that there was trust which was attached to illicit practices to which Czechs became tolerant as they became internalised in the national socio-cultural fibre (Lizal & Kocenda, Citation2001; Myant & Smith, Citation2006; Wallace & Latcheva, Citation2006; Vodrazka, Citation2009; Lyons & Kindlerová, Citation2016). There are, however, also reports of the emergence of less favourable attitudes towards corruption (David & Choi, Citation2006; EBRD, Citation2011; Chládková, Citation2018).

3.2. Czech business environment

Social capital, trust and corruption are, much like in Czech society, in evidence in the Czech business environment. Rose-Ackerman (Citation2001) asserted that large MNCs and foreign companies could have a crucial role in the improvement of the transparency of the CEE business environment. Although the WVS (Citation2022) found that only 50% of Czechs trusted big corporations, which includes foreign firms, and 30% believed that most or all business executives were involved in corruption, a study of the state of the country’s business ethics by Šípková and Choi (Citation2015), via a large sample of Czech firms, suggests that Rose-Ackerman’s (Citation2001) predictions were correct. Šípková and Choi (Citation2015) found that the quality of the Czech business environment, in relation to corruption, had improved. However, other studies have found a clear distinction between the behaviour of foreign-owned and Czech businesses (Chládková, Citation2018; Vnoučková and Žàk, Citation2017). The disparity lies in the approach taken by these two groups. Foreign-owned firms had a corporate approach to transparency, whereas most Czech businesses had no code-of-conduct in place and the responsibility for transparency was perceived to lie with individuals, rather than with organisations. This observation links back to the societal issues derived from the country’s social capital. More specifically, it appears that judgements are made on an individual basis, i.e. inferences (Mauro, Citation1998; Rothstein, Citation2013). Coupled with the lack of responsibility attached to organisations per se, this highlights a possible tendency to view social structures by means of singularities, rather than social complexities, such as broader, bridging structures, which are synonymous with generalised trust forms.

Management and business in the Czech Republic operate partly via a gift culture. The exchange of small gifts between customers and business partners, and even between public officials and professionals, including doctors, policemen or bureaucrats, is very common (Pitt & Abratt, Citation1986; Lambsdorff & Frank, Citation2010; Moldovan & Van de Walle, Citation2013; Akbar & Vujic, Citation2014; Šípková and Choi, Citation2015; Benesova & Anchor, Citation2019). Although an outsider might perceive such exchanges as non-transparent, they are culturally deeply rooted and an important part of the Czech environment. This is due to them representing the heritage of times when resources were scarce, and thereby showing one’s appreciation was mostly by means of offering a gift that would compensate for these scarcities. Common examples would be a box of chocolates, wine, flowers, or even theatre tickets (ČTK, Citation2016, Benesova & Anchor, Citation2019).

However, with the passing of time, and the fusion of foreign and Czech organisations, the benefit of this cultural trait has been questioned (Dufková, Citation2015; Chládková, Citation2018). Data from large-scale surveys are not particularly helpful in shedding light on the issue of gift-giving as they tend to inquire about gifts, favours, and bribery in a way that equates these forms of exchange. Although a small gift does not necessarily lead to or signify bribery or corruption, reports of businesses entangled in corruption with other businesses and even with political elites or the Czech prosecution service suggest that concerns might be justified (Gallina, Citation2013; OECD, Citation2017; Transparency International, Citation2019). The question that remains largely unanswered, however, is whether this is an issue for the entire country or is associated with specific sectors or agents. Information on how younger generation managers view these issues and conduct themselves is sparse too. Therefore, the filling of these gaps in knowledge by this study would increase our understanding of these issues.

4. Methods

The contribution to the gaps in the literatures on CEE and trust and corruption is achieved by identifying the nature of these phenomena in the Czech Republic. We designed a qualitative study which employed semi-structured interviews with 12 Czech managers between the ages of 25 and 55 to answer the overarching research question: What is the nature of trust and corruption, and what is their relationship, in contemporary Czech society and business?

A qualitative design was employed due to the exploration of social capital in the Czech context being a vastly under-researched topic. Such a design addresses the need to develop our understanding by building new theory (Sinkovics et al., Citation2008; Bluhm et al., Citation2011, Doz, Citation2011). Interviews enable access to perspectives and views which have not yet been described by the literatures on trust and corruption and CEE. However, since our aim is to address the theoretical gaps in the trust and corruption and CEE literatures, which were highlighted above, a choice was made to adopt a realist approach and therewith a semi-structured interview protocol (Guba & Lincoln, Citation1994; Sayer, Citation2000; Miller & Tsang, Citation2011; Fletcher, Citation2017). We follow the realism paradigm to explore the experiences, perceptions, attitudes, and feelings and emotions of our respondents and to retain the possibility of drawing on the literature for explanations, i.e. employing abductive reasoning (Maxwell, Citation2012). Unstructured interviews, following an approach closer to grounded theory, would not have been appropriate (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967; Healy & Perry, Citation2000; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2007). This is because some knowledge of the topic, although not the particular focus of our study, is already available in the trust and corruption literature. The resulting interview protocol in outlines the interview structure and offers examples of the interview questions. The protocol was first developed in the English language and a professional interpreter was recruited for back-translation to ensure that the meaning of the Czech language version of the protocol was the same (Sinkovics et al., Citation2008).

Initially, 15 Czech managers agreed to discuss trust and corruption and their connection; however, owing to the richness of the data and the reaching of a saturation point early in its collection (Fusch & Ness, Citation2015; Lowe et al., Citation2018; Saunders et al., Citation2018), interviews were conducted with 12 managers. The idea of saturation in qualitative research is somewhat contested and arguments against observing it exist (Sebele-Mpofu and Serpa, Citation2020). However, due to our study being realist in nature, i.e. aiming to extract shared mechanisms and patterns from the data, it was implemented in our data collection. There are various views on measuring when a study reaches its saturation point and different factors, such as the study purpose, the information power of respondents, or their diversity, pose different requirements on the number of respondents. Given that our study was conducted with a relatively homogenous sample, and we followed the data saturation guidance (Saunders et al., Citation2018), the 12 respondents were sufficient. This is also in line with the findings of Hennink and Kaiser (Citation2022) who, focusing on the issue of saturation point in medical studies, concluded that studies reached their saturation point between 9–17 interviews. We started noticing that only a negligible novelty was added to our interviews after about 8 interviews and conducted the additional 4 interviews to check whether this was due to a particular interviewee. Since the additional 4 interviews followed the same pattern, we stopped with the data collection after 12 interviews.

We employed purposive sampling and used a facilitator to recruit the respondents. Purposive sampling was useful in ensuring the information power of our respondents (Doz, Citation2011; Malterud et al., Citation2016). The decision to use a facilitator, who was a Czech businessperson with a wide network, followed recommendations for interviewing sensitive topics in untrusting environments by Roman and Miller (Citation2014) and observations made by EBRD (Citation2011) during their data collection in the Czech Republic which had suggested a low trust in researchers by Czechs. The facilitation of the relationship between respondents and researchers helped to build a relationship of a priori trust and contributed to greater openness in the interviews.

Profiles of the respondents are shown in and include their demographic and business contexts, including whether they have had international experience or exposure – either at home or abroad. It is noteworthy that most of our respondents were based in or previously worked in the country’s capital or some of the more economically developed regions which have strong international links. Bláha (Citation2023) found a regional divide in the Czech Republic in terms of its socio-economic environment, and despite the sample meeting the criteria to answer our research question, the regional differences, need to be highlighted here (Alesina & Giuliano, Citation2015).

Table 1. RespondentsFootnote5.

This resulted in approximately 30 hours of transcripts in the Czech language. The analysis was conducted in the Czech language to prevent the loss of meaning of some of the idioms which were used (Temple & Young, Citation2004; van Nes et al., Citation2010). This was possible due to the principal investigator being bilingual. However, with English being the language of theory, ambiguous meanings were discussed by the research team, in line with Nowell et al. (Citation2017) framework, to ensure its relevance to the literatures and theories of trust and corruption and CEE.

Thematic analysis was suitable to the purpose of the study and the nature of the data and Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) protocol, complemented by Nowell et al. (Citation2017) protocol which emphasises trustworthiness, were employed. The approach to data analysis in business and management studies is often undertaken using a software (Sinkovics et al. Citation2008). However, in studies which aim to explore the complexities and richness of their data, using a software could lead to the researchers’ loss of control over the data and potentially to the quantification of the qualitative data (Sobh & Perry, Citation2006). Data was, therefore, analysed manually to retain control over the process and researcher triangulation was adopted to ensure the reliability of the analysis. This involved the analysis of the data and consequent discussions of their meaning and the common themes. This approach also enabled constant comparison in the development of the themes and the checking of those themes against the literature and the exploration of adjacent literatures for some of the themes. It is noteworthy that the saturation point was also reached during the analysis, i.e. it satisfied the criteria set by the thematic saturation model (Saunders et al., Citation2018). The themes are presented and discussed below.

The study followed the ethics guidance set by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC, Citation2018) and there were strategies in place to eliminate researcher bias – researcher triangulation most notably. Additionally, since a facilitator was involved in the recruitment of respondents (although not the interviews per se), we trained the facilitator and signed confidentiality and non-disclosure agreements to protect both the respondents and our facilitator, given the sensitive nature of some of the topics.

5. Results

The results of the analysis are organised within four overarching themes: rifts in the Czech environment, the causes of these societal cracks, the mood in relation to these issues, and future change and hope. The results pertaining to these themes will be presented in that order.

5.1. Rifts: trust and corruption three decades after the 1989 Velvet Revolution

Rifts, gaps, and distance between, but also within, different parts of the Czech environment were prominent themes in our data. This fractionalisation was said to be partly due to issues of low trust and social capital. Our respondents did, however, offer some interesting views of corruption and trust.

Corruption, our respondents suggest, has changed over the last three decades, but it does not mean that it has disappeared completely. The themes derived from the respondents’ commentaries on corruption were intriguing and highlighted that not all corruption is seen to be equal. First, it was considered that the root cause of societal corruption has changed from necessity, which was the main reason during the Communist regime, to greed. However, greed was split between ‘pure greed’ and a somewhat ‘necessity-based greed’. The latter was said to be caused by differences still existing in the levels of the quality of services and consumer goods. The former shifts our attention to what some of the respondents referred to as corruption done by ‘the old pigs’ (R4) which leads to a ‘same style, new coat’ (R7) type of corruption, i.e. former Communist Party members who are still present in a different form. This was said to be the corruption which causes most rifts because it reminds our respondents of the Communist networks and undermines social trust and the country’s social capital more generally.

The low levels of trust and the persistence of suspicion among Czechs was apparent among most of our respondents. They did not say explicitly, with a few exceptions, that they did not trust people, but comments such as ‘you better be careful’ (R3), ‘you never know what others might do’ (R6), ‘you can never be too careful’ (R12) or the milder ‘you can trust … but always verify!’ (R10) were common in the data. Such caution should not be surprising given that ‘you’ve had people living in Communism for forty odd years!’ (R2). Indeed, the reference to the old regime was the most common theme pertaining to the explanations of the low trust and social capital stocks and the causes and consequences of corruption. This brings our results to the main rifts we observe in the data: fractionalisation of society via individualisation, distinguishing between clean and corrupt sectors of business, society and the public sector, and compartmentalising views into us and them.

The fractionalisation of Czech society was an issue that all our respondents agreed upon, even those who suggested that the circles in which they operate – both personally and professionally – suffer from this much less. The data highlight clearly that both change and the responsibility for it lies, according to our respondents, with individuals. They suggest that ‘everything goes down to individuals’ (R8). This is the case for a positive change where ‘people have to change [on individual levels], not institutions’ (R1), but also in assigning the responsibility for wrongdoing, such as corruption, because ‘it is the individual who did that, not the company[!]’ (R10). This individualisation of action and behaviour was apparent in the wider environment too. A gap is observed between the business environment and society more generally. Apart from a few industries, the business environment was said to be of a ‘relatively good quality’ (R5) and the respondents’ experience is that ‘everyone wants to do a good business, so why would they screw you over[?] it’s not like it used to be, it’s more of a win-win mindset now’ (R6). One of the main reasons is apparently the presence of ‘foreign companies and expats from more transparent countries with better trust [than in the Czech Republic]’ (R9).

The rest of society, however, was said to be unsettled. The greatest levels of suspicion, often resulting in animosity and hostility, was towards politicians and those who were referred to as ‘the old structures’ (R1, R3, R4, R5, R8, R9, R10, R12), meaning the social structures and networks which developed during communism, and which survive to date. To this end, politicians and the police were the common denominator in these problems. Interestingly, politicians were seen as either greedy, i.e. those who ‘just want to grab as much as they can for themselves’ (R11) or/and vicious, i.e. those ‘bastards who are still doing the same “pigsties” they used to … murders, corruption, and basically the same stuff as your typical mafia’ (R4). The police were said to be linked to the latter: ‘you have the cases of murder where police are basically hiding murderers, so that’s disgusting [!]’ (R12). On the other hand, bureaucrats and public officials, other than politicians and political elites, were perceived as good, efficient and generally transparent people. The planning and land office was an exception, but even that has, according to our respondents, improved. They mentioned that the gift culture still prevailed in relation to bureaucrats, but that it was mostly ‘small tokens of appreciation’ (R10), ‘basically just to say thank you for your help’ (R6), thus corresponding with the practice described in Czech business. One respondent (R2) made an interesting observation at the local tax office where a sign had been put up in the waiting room, which says ‘please, don’t give anything to our employees’; however, R2 says, in response to this sign, that ‘it is not the problem that [the Czech Republic] has with corruption … it’s like not an issue if I bring a chocolate or a coffee … this is just a cover-up of the real corruption … what a cliché [!]’.

This compartmentalised view of Czech society, institutions, officials, and, to a small extent, business, is best themed as ‘us and them’. The older generation was seen as them and the new, younger generation, was referred to as us. Czechs were referred to as us, and foreigners and foreign companies were referred to as them. Whereas the former was harsher on the them, the latter were harsher on the us. This suggests that the foreign environments they work with and know, which were mostly more developed, Western democracies, are perceived as more transparent, trustworthy and ‘better and more decent than [in the Czech Republic]’ (R2). The data make one ask whether it is possible that the exposure to more transparent agents and environments might lead to harsher views of the Czech environment and its agents. The following section, which uncovers some of the causes of these rifts will provide answers to this question.

5.2. Corruption: a scapegoat for an unhealed past

There are many causes of the current state of Czech social capital and of corruption. The question, however, is whether it is corruption that is at the heart of the country’s problems pertaining to social capital and trust. The answers that emerged from the data are intriguing. The respondents’ views seem conflicted and in some ways contradictory at first, which led us to explore the underlying issues via abductive reasoning. This is due to many respondents initially suggesting that corruption is why ‘no one trusts anyone and anything [in the Czech Republic]’ (R4) or that ‘if you have people see that corruption is normal all the time [on the news], of course you will think who else is doing it[?]’ (R3). However, when asked about whether times in which corruption affairs feature prominently on the news and make the headlines almost constantly, they were mostly indifferent. The most common response was that ‘[they] don’t get affected by these global news’ (R7) or that they ‘don’t notice [their] trust lowering in times of corruption seasons’ (R11). Some even suggested that they were ‘very sceptical about these big news [of corruption] because you never know if it’s true or if someone [the accuser] is using corruption to undermine or discredit someone [the accused]’ (R10) because this is ‘still very common [in the Czech Republic]’ (R9).

However, if corruption was said to be the common denominator of what eats away at the moral fibre of Czech society, but has very little effect on our respondents, what is happening? The data reveal some possibilities. First, the anger that accompanied the discussions of corruption is not necessarily a reflection on corruption per se, but of what corruption represents. The respondents were very clear that ‘the problem this country has with corruption is not some petty bribes of a magistrate lady or a doctor’ (R2), instead it is the ‘old friends [from the Communist regime] doing the same things they have always been doing, in front of everyone’s eyes’ (R9) and ‘[i]f someone does something [in the Czech Republic, they are] not even ashamed of it … a politician comes to the public and says joyously “So, now I have robbed you all off, and what are you going to do about it, if I have the right friends who are going to sort everything out!” … this doesn’t happen anywhere else in the world, but we let it go to such extent [in the Czech Republic] which is ridiculous’ (R10). The connection of corruption to the old regime that angered the respondents, coupled with the lack of decency and transparency in resolving and sentencing corrupt agents, of which most, according to our respondents, were politicians and businesspeople who used to be in the Communist party, was apparent among all respondents. Indeed, many suggested that ‘you can’t really trust [the Czech system] if you know that they take a decade to sentence [someone who has been caught red-handed] … that’s ridiculous[!]’ (R5). Indeed, concerns over the Czech prosecution service and loopholes in the Czech legal system that enables corruption to happen was a prominent concern in the data. The main concern was that policymakers were ‘serving themselves, not the [Czech] people’ (R12) and therefore ‘you cannot expect that those who abuse the [loopholes] will change the laws that help them do it[!]’ (R5).

These themes all point to one overarching theme – the old Communist structures and the painful past. The data suggest that scars run deep and remain unhealed to date. Every sign of corruption is like putting salt on the wounds and perpetuating those societal rifts that we observe in our data. This means that corruption gets the blame, but is not the cause, i.e. it is the scapegoat that helps our respondents cope with what they see as the ‘same [communism resembling] style, new coat’ (R7). The rage at the current state of political corruption is apparent in the respondents’ speech, but it covers up the emotion with which they reflect on Czech social capital and society which, in fact, was not anger. The next theme will delve into the mood and emotions we observed among our respondents.

5.3. Mood: suspicion, pessimism, cynicism, sarcasm and apathy

Suspicion and pessimism best describe the emotions displayed by our respondents, whereas cynicism and sarcasm best capture how they report these emotions. There were two additional emotions displayed by the respondents that require attention – sadness and disappointment. Therefore, it is not surprising that apathy was a prominent coping mechanism for all respondents.

Feelings of pessimism were mostly displayed or reported in relation to developments after the Velvet Revolution of 1989. This was because expectations were high, but the execution of the transition is perceived negatively. The ‘old structures [apparently] had even more opportunities’ (R8) to engage in malicious behaviour, which often involved corruption. Pessimism and often hopelessness were evident in the way in which the Czech legal system was said to deal with those corruptors who were caught ‘red-handed’. In addition to sadness, suspicion was a prominent theme too; however, this time, the subject of suspicion was not just politicians and those referred to as ‘old structures’, but people in society more generally. This was apparent from comments such as ‘you never know what [others] are doing’ (R10), ‘others might be doing it [meaning corruption] too’ (R12) or ‘maybe that if [people] see that [corruption] is a normal thing then they would do it too’ (R6). The suspicion was also accompanied by uncertainty about others, i.e. the inability of our respondents to be able to trust people in general with confidence. This was despite them ‘want[ing] to trust people, but you just never know’ (R2) or because one simply ‘can’t be too careful’ (R8).

Cynicism and sarcasm were prevalent in the manner of the reporting of views pertaining to corruption and trust, and it was apparent that they were some of the ways of coping with the feelings of pessimism and suspicion. However, they were not how most respondents cope with the feelings of disappointment, hopelessness and, to some extent, sadness. Apathy was instead a prominent theme when dealing with the latter. The commentaries were along the lines of ‘there’s nothing you can do about these things, so why bother’ (R1) and ‘the old generation will have to die out and then things will change [in the Czech Republic]’ (R4). These views might give the impression that no proactive change was observed in the data. However, the apathy towards what is happening in the country did not mean that our respondents were oblivious to change, and the need to work towards it. The next theme will report on the unique approach to carrying out change which we observe in our data.

5.4. Hope: natural and exposure-induced change

Hope is perhaps an unexpected theme, considering the findings presented above. However, it is one that was prominent in the data – in relation to change. The change was in terms of the country becoming more transparent with a better quality of social capital. Perceptions of and approaches to change were a combination of waiting for change to occur naturally and proactively working towards change via the respondents’ children or the children of our respondents’ generation more generally. The way in which our respondents intentionally bring up their children ‘to make the future look like what you want it’ (R5) was the main source of hope for those respondents who had children. Those who were childless suggested that they too ‘have faith in the next generation or two’ (R9) due to them witnessing ‘how my friends guide their kids and really trying to make them new [i.e. different from the current Czech population] people’ (R3) which is a reference to them ‘growing up into anything but the old, gloomy, narrow minded people like the generation [of our grandparents and parents]’ (R1) ‘who are scared of everything and everyone they don’t know’ (R4) or have the mindset where the others are ‘these invaders from the outside’ (R10).

Another important theme that emerged from the data was that of expectations and experiences of change due to exposure to more transparent agents and environments. The important role of exposure to clean(er) and more trusting agents and environments, however, related to mostly the business environment which was said to be in more frequent and direct contact with such agents and environments than the rest of the country. These two themes were both said to lead to change for the better. The importance of such exposure lies in ‘people seeing that the way things are done in [the Czech Republic] is not normal’ (R3) and in that people can ‘realise that you can have win-win [way of doing things]’ (R12) and ‘you don’t need to screw people over to get what you want’ (R10). The view that one can ‘see that there is justice, and it is possible to do things properly [about sentencing corruptors]’ (R12) is what the respondents think the country needs for social capital to improve because of the ‘healing effect’ (R5) of this justice on society. However, despite the hopes for the healing of society via changes in the system, individuals were viewed as the source of change, rather than organisations or institutions. It was also apparent that, in comparison with natural or generational change, the expected time horizon was different. Natural change was said to be expected ‘in the next two to three generations [when the Czech environment] will be clean’ (R1) and ‘comparable to that of developed, Western countries … but it will take a few generations’ (R10). Indeed, generational change was seen as the main hope for the country.

6. Discussion

What is the nature of trust, corruption, and their relationship in contemporary Czech society and business? The discussion of the results will answer this question and will also focus on the themes of fractionalisation and its implications, the role of exposure to foreign and more transparent environments and its implications for change and the country’s outlook for the future.

There have been some improvements in both trust, particularly in the police and courts and the institutions (ESS, Citation2022, WVS Citation2022), and corruption (Transparency International, Citation2022), compared to the Communist era and after the Velvet Revolution. However, corruption and trust, as well as social capital more generally, were clearly problematic for the respondents. The more pressing question, however, is whether the reported trust was low because of corruption and what was the role of trust in the reported corruption. The results pertaining to trust are fascinating in that they offer a different view of the link between trust and corruption than we see in the literature (e.g. Uslaner, Citation2002, Bjørnskov, Citation2003a, Rothstein & Uslaner, Citation2005, Chang & Chu, Citation2006, Rothstein & Stolle, Citation2008, Rothstein & Eek, Citation2009, Morris & Klesner, Citation2010, Richey, Citation2010, Bjørnskov, Citation2011, Sööt & Rootalu, Citation2012, Kubbe, Citation2013, Wroe et al., Citation2013, Uribe, Citation2014, Habibov et al., Citation2017).

The fact that corruption was said to influence trust very profoundly and directly at first, only to later be said to have no influence on the respondents’ trust, was a surprising outcome. However, when inquiring into the possible explanation of this finding, the view that corruption represented the real cause of low trust was commonly held. This is logical, in view of corruption being attributed to the old Communist structures, which we also identified as the main sources of pessimism, suspicion, and anger which led to low trust and social capital. One might argue that this points to corruption as the main cause of low trust, but this is not correct. Corruption was reported in two contexts – corruption linked to the old structures, and a more general corruption, such as when someone wants to obtain an advantage in the context of access to services or goods. While much understanding was expressed in relation to the latter, the ‘old networks’ type of corruption was viewed very negatively.

This result is different from what the extant trust and corruption literature suggests. One might wonder if this is a significant finding or if this observation is possibly a negligible nuance. Theoretically speaking, putting much emphasis on whether corruption influences trust (and social capital) directly or indirectly, is only slightly different. Bjørnskov (Citation2011) and Rothstein (Citation2013) highlighted that corruption might only be one factor which should not be isolated from the rest of the environment. However, the literature on trust and corruption often promotes corruption as the main agent in contexts with low trust and low social capital. CEE is prone to this generalisation too. However, the results show that corruption, how it is perceived, and the link between corruption and trust that was reported is not necessarily the cause of low trust and low social capital, but a phenomenon signalling a deeper issue.

Vaclav Havel, the first democratically elected president of the Czech Republic, highlighted the need for healing and proactively building trust in Czech society (Flores & Solomon, Citation1998). Acknowledging that the problematic relationship between trust and corruption might, in fact, signal deeper issues, such as the unforgiven past and the survival of its characteristics, will therefore enable a shift in focus to the real cause of the low levels of trust and social capital in the Czech Republic. This could potentially lead to a real change towards an improved social capital. Indeed, it appears that the need for transparency highlighted in our study was related to the transparency of agents and relationships in former Communist networks, rather than corruption per se.

Such transparency could be achieved in several different ways. However, a top-to-bottom approach might be most effective in the case of the Czech Republic. This argument is not only supported by our data, despite the issue of fractionalisation, but also the literature on trust, social capital and the link between trust and corruption, which suggests that ‘fish always rots from the head down’ (Rothstein, Citation2013), and that institutions have the ability to promote and generate generalised social trust more impactfully than agents (Bjørnskov, Citation2003a, Rothstein & Eek, Citation2009, Richey, Citation2010, Kubbe, Citation2013, Uslaner, Citation2013, Semukhina & Reynolds, Citation2014). Three themes from the data suggest how this might be possible.

Firstly, regulation and law, which were said to be problematic, if addressed, could indicate to society that things are improving. The view that those who need to make these changes, however, benefit from the current loopholes in the legal system (Lizal & Kocenda, Citation2001, Gallina, Citation2013), presents a barrier to such changes, and highlights the issue of state-capture faced by several CEE countries (Wallace and Latcheva, Citation2006, Zakaria, Citation2012, Éltető & Martin, Citation2024). The Czech Republic is no different, and the official statistics suggesting an extremely low trust in the politicians and political parties in the country highlight this issue (ESS, Citation2022, WVS, Citation2022).

Secondly, the theme pertaining to the role of the prosecution of corruption offers cues for reducing these barriers. Indeed, the legal system, including the police, are particularly impactful in making a change because they are the institutions representing justice. Justice, if carried out transparently, induces perceptions of fairness – perhaps the most important element in the development and retention of trust (Uslaner, Citation2008a, You, Citation2012). Whilst the WVS (Citation2022) as well as the ESS (Citation2022) highlighted that trust in police, courts, and the administrative system is changing, the data from OECD (Citation2017) highlight that inefficiencies in prosecuting corruption persist.

Lastly, the themes of reporting, prosecuting, and sentencing corruptors point to anti-corruption campaigns and their execution. This is partly related to the many cases where corruptors have been identified, as the result of such anti-corruption initiatives, but never sentenced or, as our respondents suggested, punished. A similar observation was made by Gallina (Citation2013) and OECD (Citation2017) in relation to Czech anti-corruption efforts and foreign bribery, respectively. Therefore, addressing these areas has the potential to make a particularly positive impact on trust and corruption. However, much like in relation to the previous point, the issue of state capture presents a barrier.

The literature on the CEE transition and the state of society talks about the nature of Czech social capital, which is characterised by high levels of particularised trust, but low levels of generalised trust (EBRD, Citation2011). This fractionalisation was also apparent in our findings, and it is therefore beneficial to look at this issue more closely using trust and corruption theory. Two main aspects of the interplay between the trust and corruption mechanism are particularly relevant – the concepts of inferences and that of collective action. Inferences were relevant to how corruption influences trust and social capital. It is interesting that Mauro’s (Citation1998), Uslaner’s (Citation2002) and Rothstein’s (Citation2013) theory of inferences was only observed to some extent. The analysis showed that the respondents were generally suspicious and made inferences about others, but most of them said that they would not engage in corruption themselves, despite them thinking that there is a strong possibility that others may do so. Whilst inferences indicate one of the mechanisms of the fractionalisation, the collective approach to problem solving was linked more strongly to the implications of the fractionalisation.

Collective action problem solving is a mechanism which is often seen as an extremely efficient approach to addressing corruption (Svendsen, Citation2003, Vodrazka, Citation2009, Rothstein, Citation2013). However, due to the fractionalisation observed at almost all levels of Czech society, collective action is seen as almost impossible. The business environment and, to a lesser extent, the bureaucratic layer of the Czech public sector were the only exceptions. The most plausible explanation of why this was the case is that the business and administrative environment has a relatively clearly defined set of rules and goals, which can unify its agents in their conduct (Coleman, Citation1990, Putnam, Citation1995). Indeed, solving issues collectively requires a shared understanding and conduct by the participating agents. On the other hand, in circumstances where agents have different goals and aspirations and not always a shared understanding of the purpose or, particularly in the case of corruption, the common goal might be generally understood but not fulfiled by all agents. This issue is not therefore only linked to collective action and fractionalisation but to a direct betrayal of trust, which is Rose-Ackerman’s (Citation2001) view of the link between corruption and trust, and as such leads to the further erosion of social capital. Additionally, the respondents were affected negatively not only by the former regime, but also by disappointment with the Velvet Revolution. Indeed, the way in which the transition was carried out has been said to have had a negative effect on social capital and transparency in the Czech Republic (David & Choi, Citation2006, Svejnar & Uvalic, Citation2013, Kovalčíková & Lačný, Citation2016), and our data confirmed this negative perception.

The continuous reinforcement of the old wounds is one reason why Czech society was said to remain unhealed to date. There were, however, signs of improvement. The two modes of change – exposure-induced and generational change – are both intriguing, for different reasons. Generational change is often discussed in literatures on change (Heath, Citation2014, Tremmel, Citation2019, Cingolani & Vietti, Citation2020), and transition in the CEE is no exception (Waechter, Citation2016). However, the intentional approach to change via children’s upbringing is, to the best of our knowledge, new. It is particularly interesting for three reasons. First, it aligns with the issue of the lack of hope, suggesting that actions associated with a direct, proactive change are seen as a waste of time and energy. This is not surprising in the light of the fractionalisation of society identified and the resulting lack of collective action problem solving. Secondly, it resembles the pre-revolution society which was based on bonded trust while preparing the revolution in the form of a ‘silent resistance’ (Vaněk & Mücke, Citation2016). This approach via a collective change by cumulative individual action resembles that and is supported by the WVS (Citation2022) finding that 90% of respondents trusted people in their close circle. Lastly, the views of childless respondents align with those who have children, which signifies intragenerational trust (Putnam, Citation2000, Holm & Nystedt, Citation2005). Since our respondents spent their adult lives in a democratic Czech Republic, this might be indicative of positive developments in the country’s social capital among those who have not been affected by Communism as much as previous generations. One might understand this as a common generational gap. However, this would not be correct. Indeed, the hope placed in the current young generation coupled with the perception that ‘the old generation will have to die out and then things will change’ (R4) was strong.

Exposure-induced change, via more transparent and foreign environments, was prominent in Rose-Ackerman’s (Citation2001) hope for CEE. However, her view was more direct than the one we found, or perhaps it would be more precise to say can be seen as an addition to it. The results do show how agents and organisations from foreign, more transparent and trusting environments influence our respondents. However, considering the strong emphasis on the importance of the ‘old structures’ in the expressed views of the respondents, the question we ask is whether this healing effect might be due to the foreign agents serving as a confirmation that the ‘old structures’ are not present. This is a plausible explanation in view of the secrecy surrounding the agents supporting the Communist Party prior to the Velvet Revolution. This is known to have resulted in the persistence of suspicion in Czech society as to which agents were members of the Communist Party or StB and is particularly prominent when old records, which reveal the identity of those agents, are released (Cibulka, Citation1999). If this is the case, it points to the possibility that foreign agents do not actually heal the Czech environment, but merely dilute it. It also begs the question of what would happen if these foreign agents disappeared from, or their concentration was lowered in, the Czech environment. It is not possible to rule out that it would lead to lower social capital in well performing areas of the Czech Republic, such as the business environment. The Czech Republic is enjoying high levels of foreign investment (Hampl et al., Citation2020); however, should the foreign presence decrease due to, for instance, increasing production and labour costs, it could present a challenge to the social capital of the country and its business environment.

Change via exposure, coupled with generational change, present hope for the Czech Republic, despite the current fractionalisation of its society and its low levels of social capital. The findings on trust and corruption and the current climate, however, suggest that certain areas of society and the country’s past will need to be healed before the country can move on. Indeed, the pessimism and negative perceptions about the impact of the country’s past were strong among our respondents. One might find the findings unsurprising since they are aligned with the literature on the early stages of CEE transition but given that our respondents were young people who had spent their adult lives in a democratic society, they are unexpected. However, the results also show that, despite the negative mood, the actions of our respondents were more transparent than the literature suggests. It was also apparent that they would like to trust, suggesting that they have hope. Therefore, these positive trends are likely to be seen in the country’s future – a prospect which would certainly be welcomed by institutions, businesses, investors and, most importantly, by Czech society.

7. Conclusions

Transition is a popular context for social studies. It is not only the transition that immediately followed the 1989 Revolution which is important. It is the kind of societies it resulted in. Some of the countries of the CEE, like the Czech Republic, have caught up economically and institutionally with some of the most developed Western countries; yet, under the surface, structures and mechanisms from the past survive. Since the CEE countries have all gone through a very similar experience in the past (EBRD, Citation2011), it is possible that the results are applicable to the region more widely. The findings also have some important implications for theory and practice.

First, the gap between the older and younger generation suggests that two experiences are lived in parallel in Czech society. The question, therefore, is whether the large-scale survey results, which suggest ‘grey’ social capital, are not simply blending the ‘dark’ of the older and the ‘bright’ of the younger generation. The social capital of the younger generation, which was found to remain detached from addressing socio-political issues, is a passive asset. Apathy and lack of faith were said to be the key that could unlock the door to the social capital of the younger generation. Additionally, creating links between the generations might help turn the accumulated social capital into positive action.

Second, the possibility that corruption might not be the cause of low trust is crucial. The real cause, which appears to be embedded in the historical networks, if properly diagnosed and addressed, could activate some latent social capital. Speeding up the prosecution of corruption and lowering the tolerance to it by Czech legislation would be particularly effective (OECD, Citation2017). To this end, a realistic approach to anti-corruption needs to be taken since uncovering corruption without prosecuting it would increase apathy and further damage social trust (Gallina, Citation2013).

Third, the economic success that the Czech Republic enjoys, despite the issues with its social capital, has theoretical implications. The literature argues that social capital contributes to economic growth (Berggren & Jordahl, Citation2006). This does not necessarily apply to the Czech experience. Future studies should therefore focus on CEE to identify the mechanisms that contribute to economic success amid low social capital. Alternatively, there is a possibility that the economic success of the Czech Republic may have been driven by the younger generation which has, in the business context, a relatively high level of social capital and generalised trust.

Fourth, the idea of foreign agents and companies diluting, rather than changing, the environment raises questions about the sustainability of the social capital of the business environment if it depends on the presence of those companies and agents, thus adding to Rose-Ackerman’s (Citation2001) theory of the role of multinational companies in CEE. Therefore, assessing such sustainability and finding ways to increase it would be a promising theme for future research.

Lastly, the change that is forming under the surface gives us an indication that swift changes can be expected from the next generation. Studies of change could map these changes to further inform us about what can be expected. Similarly, exploring the views of young people could help us understand what the future of the region might look like. An early understanding of these forces would help us, if socially and politically supported, to encourage and speed up change, and better prepare for the future Czech Republic and possibly other CEE countries.