ABSTRACT

There are few process evaluations of school-based alcohol education programmes, especially examining teacher’s role in implementation. Using a Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework, this qualitative study identifies the barriers and enablers to teacher delivery of the Talk About Alcohol (TAA) programme in UK secondary schools and provides strategies for improvement in this context. Ten teachers were interviewed about influences on their delivery of the TAA programme. Interview transcripts were analysed thematically using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and then Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) were identified for optimisation. Key enablers included increased knowledge from training and resources, increased confidence and effective resource design. Barriers included social pressure on students and further training on complex issues related to alcohol use such as consent. Delivery was influenced by a range of positive enablers which can inform other school-based alcohol interventions. Strategies for optimisation include follow-up training sessions, notifications of new updates to the programme resources, training highlighting past successes for teachers and further action planning for students. This evaluation highlights how the BCW approach can be used to improve teacher implementation in educational research.

Harmful use of alcohol can lead to a variety of negative health outcomes for young people, including impaired brain development, physical or mental health problems and alcohol-related injuries (Viner and Taylor Citation2007). While there has been a downward trend in the number of young people requiring treatment at drug and alcohol services for several years in the UK (Office for Health Improvement & Disparities Citation2022), early prevention must remain a priority given the potential for serious harm by drinking alcohol at a young age.

School-based interventions present a unique opportunity for early intervention, offering a clear point of access to adolescents (Hennessy and Tanner-Smith Citation2015). Talk About Alcohol (TAA) is one such school-based intervention (Citation2020). An outcome evaluation of TAA found evidence of its effectiveness in delaying the onset of alcohol use in secondary school students in comparison to those attending control schools (Lynch, Dawson, and Worth Citation2014), however, there has yet to be a process evaluation.

A process evaluation investigates the way in which an intervention is implemented, providing valuable insights into how the intervention can be optimised and replicated in different contexts (Craig and Petticrew Citation2013). The present study aims to illuminate the influences on teacher delivery and provide key strategies to improve the implementation of TAA and similar interventions. Using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) approach (Michie et al. Citation2014), we examine the barriers and enablers to teacher’s delivery of TAA and then identify strategies for its optimisation.

Research background

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of school-based alcohol interventions has been contested over the last two decades. Despite claims that school-based alcohol prevention programs are ineffective (Babor Citation2010; World Health Organization Citation2009), later systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown positive effects (Agabio et al. Citation2015; Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze Citation2012). Effectiveness may be increased by having a shorter-duration intervention, delivering the intervention online and including a parent-student component (Champion et al. Citation2013; Hennessy and Tanner-Smith Citation2015; Newton et al. Citation2017). Given variation in the reports of their effectiveness, a better understanding of the processes and implementation of school-based alcohol intervention programs are needed (Thom Citation2017).

In terms of implementation, delivery has been recommended for further evaluation in school-based alcohol interventions for some time (Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze Citation2012). Delivery can be defined as the features of an intervention that convey content to change human behaviour including the deliverer, format, materials, setting, intensity, tailoring, and style of the intervention (Dombrowski, O’Carroll, and Williams Citation2016). Despite often being the main deliverer of school-based interventions, teachers have been under-represented within this research (Davies Citation2016; Davies and Matley Citation2017).

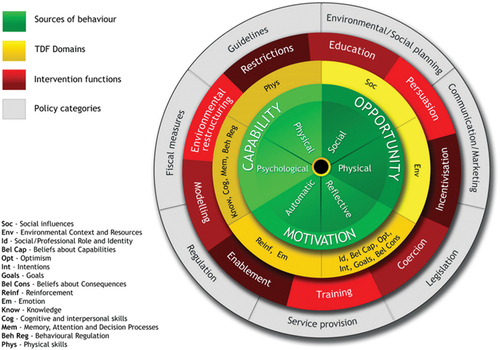

Although the BCW was not used in the design of the TAA programme, it can be a useful tool in process evaluation, with the aim of optimising an existing intervention. As the delivery of an intervention is considered a behaviour, the BCW has been used in previous process evaluations to identify the influences on how an intervention is delivered and suggest implementation strategies for improved delivery (e.g. Moran & Gutman, Citation2021; De Winter & Gutman, Citation2022). Developed from 19 behaviour change frameworks, the BCW identifies the sources of a behaviour, intervention functions and policy categories (see ). At the centre of the BCW, the COM-B posits that capability, opportunity and motivation are necessary for behaviour change to occur. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) provides more granular components of the COM-B domains (Michie et al. Citation2014). In a behavioural analysis, the COM-B model and TDF can be used to identify the barriers and enablers to a specific behaviour.

Figure 1. Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) and Theoretical domains Framework (TDF), Michie et al, (Citation2014).

The Behaviour Change Techniques Taxonomy (BCTTv1) is a tool that can be used to suggest strategies to address barriers and enhance the enablers identified in the behavioural analysis (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2013). Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) are considered the ‘active ingredients’ of a behaviour change intervention. The BCW and BCTTv1 are linked through expert consensus, which shows which COM-B or TDF components are most likely to map onto certain BCTs (Michie et al. Citation2014). Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) are listed within the BCTTv1 and some have already been incorporated into school-based interventions (Routen et al. Citation2017). An understanding of the influences on teacher delivery and the corresponding implementation strategies to enhance enablers and tackle potential barriers for improved teacher delivery can be used to optimise the design and delivery of TAA and similar school-based alcohol interventions.

Current study

The current study aims to address the existing research gap in school-based alcohol interventions with a process evaluation examining teacher implementation. Using the BCW framework, we focus on teacher delivery as a specific behaviour with the following research questions: 1. What are the barriers and enablers to teacher delivery of the TAA programme in UK secondary schools? 2. Which BCTs might be used to counter the barriers and enhance the enablers to improve teacher delivery of the TAA programme to secondary school students?

Methods

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University College London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee on 25/05/22 (Project ID: 22633/001).

Talk about alcohol programme

TAA was designed by the Alcohol Education Trust, an independent, UK-based charity which aims to keep young people (mostly 11–25-year-olds) safe around alcohol and to tackle social norms and stereotypes (The Alcohol Education Trust Citation2020). Resources are provided free of charge for schools, though training is recommended for teachers to understand and implement them. The resources include lesson plans, a teacher workbook, activity cards and films (see for a full list). In the Lynch et al., (Citation2014) outcome evaluation, minimum requirements were set as to what teachers needed to deliver in order to be a part of the evaluation, including specific sections of the teacher workbook and one hour on the www.talkaboutalcohol.com website.

Table 1. Resources provided as part of the TAA programme.

Participants

Participants were contacted via email by the Alcohol Education Trust using a convenience sampling approach. To be eligible for interview, participants must have either: a.) received training, b.) delivered the TAA resources or c.) coordinated or worked closely with colleagues who delivered the resources (for example, in the room during the training or delivery). Participants were offered a £20 Amazon voucher. In line with previous qualitative studies using the BCW (Hennink and Kaiser Citation2022; Richiello, Mawdsley, and Gutman Citation2022), ten participants were interviewed (see ).

Table 2. Participants.

Procedure

The COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) checklist was used to ensure accurate reporting in this study (Appendix A). Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted by the first author. Interview questions were based on the TDF (see Appendix B). Demographic information was not collected in this study as it was not deemed necessary to the research questions (Morse Citation2008). Interviews occurred online, lasted 30 to 50 minutes and were recorded using Mircosoft Teams.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim using Microsoft Stream. Reflexive thematic analysis was employed to identify barriers and enablers to delivery of TAA. Data were first coded deductively to the COM-B and TDF domains, followed by inductive coding to generate sub-themes by the first author. This sequencing of analysis can help to provide a more in-depth understanding of the influences on behaviour (Braun and Clarke, Citation2012) and has been used successfully in previous qualitative studies using the BCW (Moran & Gutman, Citation2021; De Winter & Gutman, Citation2022). The features of thematic analysis are not necessarily dependent on one epistemological or theoretical position (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Therefore, this study is not attributed to any one epistemological standpoint but takes a pragmatic approach to qualitative research (Pistrang and Barker Citation2012).

A codebook was generated which contained all codes and definitions of the COM-B and TDF components to facilitate phase 3 of the analysis (see Appendix C). Codes were mapped deductively to the COM-B and TDF framework before being grouped and coded inductively to draw out common sub-themes. Inductive sub-themes were categorised as barriers or enablers to delivery. Using the Theories and Techniques Tool (https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/) the final step involved mapping barriers and enablers onto BCTs. The APEASE criteria (Affordability, Practicability, Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, Acceptability, Safety and side effects and Equity) were applied to identify the most appropriate BCTs for the context.

Results

Participants reported multiple influences on delivering the TAA programme. The majority of these were enablers relating to the COM-B components of psychological capability, physical opportunity and reflective motivation (see ). The least reported COM-B component was physical capability, suggesting this was not a necessary element to delivery of the TAA programme. A few participants suggested improvements to the training which have been framed as barriers and are discussed further in the results. COM-B components have been described as major themes while the TDF domains are represented by sub-themes. Eleven inductive sub-themes were generated via thematic analysis to offer more description and specificity, however, only details of the main findings have been reported here (see for all definitions).

Figure 2. Map of themes: indicating the relationship between COM-B components with inductive sub-themes and the target behaviour.

Table 3. Inductive sub-themes identified as a barrier or enabler with a description of the sub-themes.

Psychological capability

Enabler: increased understanding from the resources or training

Participants described how the training and resources provided them with knowledge about alcohol, facilitating their programme delivery. This was often defined as specific content knowledge such as alcohol units or government guidelines on alcohol consumption. As well as content knowledge, several participants described gaining knowledge on the style of programme delivery in the TAA training. Participants noted that this helped them to deliver information to the students without judgment or preaching. ‘I suppose our job, we’re, you know, we’re not moral ethics teachers, we’re just giving them the information, the signs and the information about how these things can impact the young people’ (T5).

Barrier: absent knowledge or skills

Some participants suggested additional information to include in the TAA training, such as understanding how to adapt the resources for different age groups and receiving more knowledge about issues surrounding alcohol and consent. As the consumption of alcohol can have an impact on an individual’s ability to consent to sexual activity which has legal and traumatic implications, teachers felt it was important to discuss this with pupils to set clear guidelines. ‘Having deeper training on consent stuff and how to deal with those traumatic things from a teacher’s perspective, I think would be beneficial to teachers going forward’ (T3). Other suggestions included having an opportunity to debunk myths surrounding alcohol at the beginning of the training session. ‘I think it would have been really nice to have just a little 5 or 10 minute slot to talk about myths about alcohol because I know there are so many social erm, like, like whether you should have spirits before beer’ (T6).

Physical opportunity

Enabler: effective resource design

Participants voiced numerous positive views about the design of the TAA resources, noting that this made them easier to deliver. It was reported that resources were up-to-date and accessible, which made teachers feel more secure in what they were teaching. ‘I mean even, you know, spiking, they keep you up to date with everything now that spiking is coming in, so we’re updated on facts and figures and ways to be careful … which is really good’ (P1). Adaptability was another strong feature of the resources. Having flexible resources allowed teachers to tailor lessons to the specific needs of their students. Resources could be adapted based on the academic ability of students, the student’s curriculum interests, or student involvement with alcohol outside of school. For example, one teacher explained how they could skip certain topics if they knew a child in their class had been having issues related to this at home. ‘‘[The resource] wasn’t scripted, you know. It’s not like you’ve got to do this today, that today, that tomorrow like it is when you do some. If I thought for one minute that one of the kids had a bad time with the parents at home that evening, then I could completely skip that and do something completely different to that, we didn’t have to look at effects of families on that day’(T1).

Reflective motivation

Enabler: confidence to deliver resources

Participants mentioned how the training and resources themselves increased their confidence to deliver the materials. This was closely linked with knowledge. Many participants cited how being more informed led them to feel more equipped to deal with student questions and to feel confident they were delivering accurate and factual information. ‘Yes, it definitely gave me more confidence being able to talk to students who might need to ask questions and like, I was already able to respond to them. Whereas before I might have had to go away and look up some information’. (T2)

Barrier: social influences on the student

Some participants mentioned the social pressures students face around alcohol from peers or home. These were seen as obstacles to delivering the resources as they may go against some of the messaging around alcohol safety that teachers were trying to promote. Views of pupils were described as entrenched via social norms: ‘It wasn’t just the views of the young people, but it was actually, what they’d been brought up seen as being, you know, perfectly normal. And it’s trying to get them to see from a different perspective and I think that’s that is a really hard thing to do’ (T3). This translates into difficulty for teachers trying to counter what pupils may see as normal or desirable: ‘It’s a losing battle with teenagers, you know, the alcohol stuff, and you know, you’re really running against the wind because, you know, you’ve got pressure from social culture. That’s incredibly powerful’ (T5).

Optimisation of TAA

Building on these results, we may now consider how the three main enablers and two barriers for delivering the TAA resources can be optimised to improve the programme. In , relevant BCTs are selected for each enabler or barrier. Each of these are then discussed in detail in the discussion section.

Table 4. Optimising the main enablers and remaining barriers to delivering the Talk about alcohol programme using Behaviour Change Techniques.

Discussion

Using the BCW framework, this study identified the barriers and enablers to teachers’ implementation of the TAA programme in UK secondary schools. For the most part, the participants noted positive aspects of the intervention, which facilitated their successful delivery. The main enablers were increased understanding from the resources and training, confidence to deliver the resources and effective resource design. The flexibility and accessibility of the resources were also noted, in line with the outcome evaluation (Lynch, Dawson, and Worth Citation2014). The barriers included absent knowledge or skills and social influences on the student which represent areas of potential improvement. The core themes and BCTs identified in are discussed in further detail below.

Enabler: increased understanding from the resources or training

Improved psychological capability through resources and training enabled teachers to better deliver the TAA programme. In recent years, teachers reported having insufficient training and knowledge on PSHE topics including alcohol (Davies and Matley Citation2020), so this theme reflecting increased understanding highlights this aspect as a key strength of the intervention. ‘Information about social and environmental consequences’ was selected as an appropriate BCT to enhance this enabler. This is defined as ‘providing information (such as written, verbal or visual) about the social and environmental consequences of performing the behaviour’. This BCT already takes place within the initial training but in line with findings from Hoffman et al’.s TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al. Citation2014), the intensity of this training could be increased. An optional booster session at the beginning of a new academic year would increase the intensity of the training and act as a knowledge ‘top up’ for teachers, something found to be beneficial in previous school-based interventions (Reinke et al. Citation2014).

Enabler: effective resource design

Physical opportunity was increased through well-designed resources, specifically, being up-to-date, accessible and adaptive. Options to tailor an intervention is an important feature of delivery in Hoffman et al’.s TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al. Citation2014). Indeed, not being able to adapt a school-based intervention was reported by teachers as a barrier elsewhere in education literature (Arthur et al. Citation2011). To optimise the programme, ‘adding objects to the environment’ was selected as a BCT. This is defined in the BCTTv1 as ‘adding objects to the environment in order to facilitate performance of the behaviour’ (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). As teachers valued resources being up-to-date, regular updates and new materials could optimise the programme further. Notifications, perhaps through a newsletter, may help to increase positive support for the updated resources (Bell et al. Citation2020).

Enabler: confidence to deliver the resources

Increased reflective motivation gained through improved confidence was a key enabler of delivering TAA. Teachers reported that this increased confidence was directly associated with increased knowledge gained from training. ‘Focus on past successes’ was selected as an appropriate BCT, which is defined as ‘advise to think about or list previous successes in performing the behaviour (or parts of it)’ (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). Asking teachers who are already familiar with the programme to list past successes could be an effective way to sustain their confidence. This has been successful in previous interventions relating to physical activity (Koring et al. Citation2012). Focusing on past successes could be combined with the recommendation of top-up training sessions, allowing teachers to strengthen the link between their capability and motivation in a new academic year.

Barrier: absent knowledge or skills

A success of TAA was having teachers involved in the design of the intervention (Lynch, Dawson, and Worth Citation2014), something described as a vital component of school-based interventions more generally (Davies Citation2016). The programme could be optimised further by reviewing more recent suggestions from teachers. ‘Information about social and environmental consequences’ was selected as a relevant BCT. Suggestions made by teachers could be reviewed and added as extra modules to the training, delivered as part of top-up sessions or incorporated as e-learning modules. Evidence suggests that online training can effectively teach teachers to deliver evidence-based preventive interventions (Becker et al. Citation2014). Again, this could be combined with previous recommendations.

Barrier: social influences on the student

Teachers reported the context in which they delivered TAA was against student expectations and entrenched views on alcohol. Teachers felt they were competing with influences outside of school including friends, family and content from social media. ‘Action planning’ was selected as a relevant BCT, which is described as ‘prompting detailed planning of performance of the behaviour, the context of which may be environmental or internal’ (Michie, van Stralen, and West Citation2011). Role-play activities or games could be modified to include more concrete plans of action for real-life scenarios. One teacher described incorporating basic first aid skills into the intervention to give students practical strategies in emergency situations. This could be adapted into action planning and would meet calls for age-appropriate first aid and CPR instruction to be implemented in schools (Wilks and Pendergast Citation2017).

Limitations and next steps

By using a convenience sampling approach, this study may have inadvertently involved self-selection bias (Heckman, Citation1990). Those who chose to participate may have been more confident or wished to express positive views as a form of social desirability (Grimm Citation2010). Given the high number of enablers identified in this study, social desirability is a real possibility. Attempts were made to mitigate social desirability by including prompts in the interview script to stress the independent role of the researcher and to ask about any challenges or improvements to be made. Although demographic information about participants was not deemed necessary to collect for this study, it is acknowledged that including them could have highlighted another influence on teachers’ perceptions of enablers and barriers.

Building on the findings of this study, researchers may wish to carry out a cost-benefit analysis of the suggested improvements made using BCTs. This would have the benefit of assessing whether the suggestions are financially viable and may help policymakers develop a benefit-cost portfolio on alcohol interventions, as has been done in school-based interventions tackling obesity (An et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, future studies evaluating school-based evaluations using BCTs may also wish to consult the considerable literature in implementation science which has highlighted the complementarity between the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) and BCTs (McHugh et al. Citation2022; Powell et al. Citation2015).

Conclusion

Using the BCW framework, this study extends current knowledge on conducting process evaluation of school-based interventions. This study further adds to the evidence-base through examining the influences on teacher delivery, which is an important component of school-based interventions that is often overlooked (Dombrowski, O’Carroll, and Williams Citation2016; Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze Citation2012). The findings underscore key features for successful teacher delivery of alcohol education including increased knowledge from training and resources, increased confidence and effective resource design. Suggestions for optimisation include follow-up training sessions, notifications of new updates to resources and additional training focusing on past successes for teachers and action planning for students. Overall, this study offers a case study for the use of the BCW approach as a comprehensive and systematic method to characterize and improve teacher delivery of school-based interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agabio, R., G. Trincas, F. Floris, G. Mura, F. Sancassiani, and M. C. Angermeyer. 2015. “A Systematic Review of School-Based Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs.” Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health 11 (1): 102–112. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901511010102.

- An, R., H. Xue, L. Wang, and Y. Wang. 2018. “Projecting the Impact of a Nationwide School Plain Water Access Intervention on Childhood Obesity: A Cost–Benefit Analysis.” Pediatric Obesity 13 (11): 715–723. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12236.

- Arthur, S., M. Barnard, N. Day, C. Ferguson, N. Gilby, D. Hussey, and S. Purdon. 2011. “Evaluation of the National Healthy Schools Programme: Final Report.” London, National Centre for Social Research.

- Babor, T., Ed. 2010. Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity: Research and Public Policy. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199551149.001.0001.

- Becker, K. D., J. Bohnenkamp, C. Domitrovich, J. P. Keperling, and N. S. Ialongo. 2014. “Online Training for Teachers Delivering Evidence-Based Preventive Interventions.” School Mental Health 6 (4): 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-014-9124-x.

- Bell, L., C. Garnett, T. Qian, O. Perski, H. W. W. Potts, and E. Williamson. 2020. “Notifications to Improve Engagement with an Alcohol Reduction App: Protocol for a Micro-Randomized Trial.” JMIR Research Protocols 9 (8): e18690. https://doi.org/10.2196/18690.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. 2012. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association.

- Champion, K. E., N. C. Newton, E. L. Barrett, and M. Teesson. 2013. “A Systematic Review of School-Based Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention Programs Facilitated by Computers or the Internet: Systematic Review of Internet-Based Prevention.” Drug and Alcohol Review 32 (2): 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00517.x.

- Craig, P., and M. Petticrew. 2013. “Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: Reflections on the 2008 MRC Guidance.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 50 (5): 585–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.009.

- Davies, E. L. 2016. ““The Monster of the month”: Teachers’ Views About Alcohol within Personal, Social, Health, and Economic Education (PSHE) in Schools.” Drugs and Alcohol Today 16 (4): 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-02-2016-0005.

- Davies, E. L., and F. Matley. 2020. “Teachers and Pupils Under Pressure: UK teachers’ Views on the Content and Format of Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education.” Pastoral Care in Education 38 (1): 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2020.1713868.

- Davies, E. L., and F. A. I. Matley. 2017. “Research on School-Based Interventions Needs More Input from Teachers.” Education & Health 35 (3): 60–62.

- De Winter, L., & Gutman, L. M. 2022. Facilitators and barriers to fitness bootcamp participation using the Behaviour Change Wheel. Health Education Journal, 81(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/00178969211044180

- Dombrowski, S. U., R. E. O’Carroll, and B. Williams. 2016. “Form of Delivery as a Key ‘Active ingredient’ in Behaviour Change Interventions.” British Journal of Health Psychology 21 (4): 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12203.

- Foxcroft, D. R., and A. Tsertsvadze. 2012. “Cochrane Review: Universal School-Based Prevention Programs for Alcohol Misuse in Young People.” Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal 7 (2): 450–575. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1829.

- Grimm, P. 2010. “Social desirability bias.” Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. https://zhangjianzhang.gitee.io/management_research_methodology/files/readings/sdb_intro.pdf.

- Heckman, J.1990. “Varieties of Selection Bias.” The American Economic Review 80 (2): 313–318.

- Hennessy, E. A., and E. E. Tanner-Smith. 2015. “Effectiveness of Brief School-Based Interventions for Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis of Alcohol Use Prevention Programs.” Prevention Science 16 (3): 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0512-0.

- Hennink, M., and B. N. Kaiser. 2022. “Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests.” Social Science & Medicine 292:114523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523.

- Hoffmann, T. C., P. P. Glasziou, I. Boutron, R. Milne, R. Perera, D. Moher, D. G. Altman, et al. 2014. “Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide.” BMJ 348 (mar07 3): g1687–g1687. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

- Koring, M., J. Richert, L. Parschau, A. Ernsting, S. Lippke, and R. Schwarzer. 2012. “A Combined Planning and Self-Efficacy Intervention to Promote Physical Activity: A Multiple Mediation Analysis.” Psychology, Health & Medicine 17 (4): 488–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.608809.

- Lynch, S., A. Dawson, and J. Worth. 2014. “Talk About Alcohol: Impact of a School-Based Alcohol Intervention on Early Adolescents.” International Journal of Health Promotion and Education 52 (5): 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2014.915759.

- McHugh, S., J. Presseau, C. T. Luecking, and B. J. Powell. 2022. “Examining the Complementarity Between the ERIC Compilation of Implementation Strategies and the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy: A Qualitative Analysis.” Implementation Science 17 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01227-2.

- McKay, M. T., N. T. Mcbride, H. R. Sumnall, and J. C. Cole. 2012. “Reducing the Harm from Adolescent Alcohol Consumption: Results from an Adapted Version of SHAHRP in Northern Ireland.” Journal of Substance Use 17 (2): 98–121. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2011.615884.

- Michie, S., M. Richardson, M. Johnston, C. Abraham, J. Francis, W. Hardeman, M. P. Eccles, S. Michie, L. Atkins, and R. West. 2014. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. United Kingdom: Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., and Wood, C. E. 2013. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of behavioral medicine, 46(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Michie, S., M. M. van Stralen, and R. West. 2011. “The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions.” Implementation Science 6 (1): 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Moran, R., & Gutman, L. M. 2021. Mental health training to improve communication with children and adolescents: A process evaluation. Journal of clinical nursing, 30(3–4), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15551

- Morse, J. M. 2008. ““What’s Your Favorite color?” Reporting Irrelevant Demographics in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Health Research 18 (3): 299–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307310995.

- Newton, N. C., K. E. Champion, T. Slade, C. Chapman, L. Stapinski, I. Koning, Z. Tonks, and M. Teesson. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Combined Student- and Parent-Based Programs to Prevent Alcohol and Other Drug Use Among Adolescents: Combined Prevention for Alcohol and Other Drug Use.” Drug and Alcohol Review 36 (3): 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12497.

- Office for Health Improvement & Disparities. 2022. Young People’s Substance Misuse Treatment Statistics 2020 to 2021: report. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/substance-misuse-treatment-for-young-people-statistics-2020-to-2021/young-peoples-substance-misuse-treatment-statistics-2020-to-2021-report.

- Pistrang, N., and C. Barker. 2012. “Varieties of Qualitative Research: A Pragmatic Approach to Selecting Methods.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, edited by H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, 5–18. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-001.

- Powell, B. J., T. J. Waltz, M. J. Chinman, L. J. Damschroder, J. L. Smith, M. M. Matthieu, and J. E. Kirchner. 2015. “A Refined Compilation of Implementation Strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) Project.” Implementation Science 10 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1.

- Reinke, W. M., M. Stormont, K. C. Herman, and L. Newcomer. 2014. “Using Coaching to Support Teacher Implementation of Classroom-Based Interventions.” Journal of Behavioral Education 23 (1): 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-013-9186-0.

- Richiello, M. G., G. Mawdsley, and L. M. Gutman. 2022. “Using the Behaviour Change Wheel to Identify Barriers and Enablers to the Delivery of Web Chat Counselling for Young People.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 22 (1): 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12410.

- Routen, A. C., S. J. H. Biddle, D. H. Bodicoat, L. Cale, S. Clemes, C. L. Edwardson, C. Glazebrook, et al. 2017. “Study Design and Protocol for a Mixed Methods Evaluation of an Intervention to Reduce and Break Up Sitting Time in Primary School Classrooms in the UK: The CLASS PAL (Physically Active Learning) Programme.” British Medical Journal Open 7 (11): e019428. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019428.

- Spaeth, M., K. Weichold, R. K. Silbereisen, and M. Wiesner. 2010. “Examining the Differential Effectiveness of a Life Skills Program (IPSY) on Alcohol Use Trajectories in Early Adolescence.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78 (3): 334–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019550.

- The Alcohol Education Trust. 2020. “About the Alcohol Education Trust.” Accessed May 12, 2022. https://alcoholeducationtrust.org/about-aet/.

- Thom, B. 2017. “Good Practice in School Based Alcohol Education Programmes.” Patient Education and Counseling 100:S17–S23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.020.

- Viner, R. M., and B. Taylor. 2007. “Adult Outcomes of Binge Drinking in Adolescence: Findings from a UK National Birth Cohort.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 61 (10): 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.038117.

- Wilks, J., and D. Pendergast. 2017. “Skills for Life: First Aid and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Schools.” Health Education Journal 76 (8): 1009–1023. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896917728096.

- World Health Organization. 2009. “Evidence for the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Alcohol-Related Harm.” World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/107269/9789289041751-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Appendix A

COREQ (Consolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) Checklist