Abstract

The creation of commercial cord blood banks rests on the promise of stem cell based regenerative medicine and marks the capitalization of human tissues within a future-oriented “regime of hope”. This paper will present data from a survey of the international cord blood banking industry and will explore: (a) the way firms seek to commercialize cord blood as a new set of commodities; (b) the expectations and moral economy that are being constructed around this technology; and (c) how firms are acting as mediators of hope in what might be called a “promissory bioeconomy”.

Introduction

The rapid development of stem cell technology has stimulated a high level of interest about the economic potential of cell-based therapies among both social scientists and policy makers. This is being increasingly framed by the growth of a new bioeconomy based on the commercial exploitation of genes, cells and living organisms. Within what has been called the “tissue economy” (Waldby and Mitchell Citation2006) the banking of the umbilical cord blood (UCB) of newborns as a source of stem cells has both stimulated consumer interest and provoked controversy over the possible misselling of an unproven technology.

This paper explores the way commercial cord blood banking is emerging internationally, representing contrasting and overlapping spaces and dynamics across public and private sectors. In particular, it will draw on ideas from the sociology of expectations (van Lente Citation1993, Brown et al. Citation2000, Hedgecoe and Martin Citation2003) to analyze the political economy of this promissory bioeconomy and how hope itself is being capitalized as the basis of commodity value. Data are presented from a global survey of cord blood banking, describing the growth, distribution and strategies of public and private cord blood banks. This will help understand both the expectations surrounding cord blood stem cells and the flows between CB banking and different forms of “biovalue”. The latter will be analyzed as the emergence of a new “regime of hope” where different forms of economic commodity, health technology and ethical rationality are being co-constructed though a process of socio-technical network formation.

We begin by exploring the centrality of the promissory future – “regimes of hope” – in the development of the contemporary bioeconomy. The next section describes the results of the global survey of cord blood banking, followed by more detailed analysis of public and private cord banking, the expectations constructed by these organizations and the way they are attempting to create value. In the final section some conclusions are drawn about the promissory nature of cord blood banking, the co-construction of new technologies and regimes of hope, and the dynamic flow of biovalue between the future and the present.

Promissory bioeconomies

In exploring the capitalization of hope, we are drawing on a growing body of literature linking expectations and new biological markets, and the spatial variation of expectations across diverse communities of researchers, investors, patient groups and statehoods (Waldby Citation2002, Brown Citation2003, Citation2007, Moreira and Palladino Citation2005, Novas Citation2007). Several contributions have noted the increasing dependence of emerging bioeconomies on a promissory future economic value and potential rather than present use. This has come to signify shifts from “regimes of truth” (linked to established practice and proven evidence), to “regimes of hope”, from rationalistic authority embedded in the past and present towards the speculatively possible in the future (Moreira and Palladino Citation2005, Brown Citation2007).

This resonates strongly with writing on the production of “biovalue” and the work of the imagination:

The biomedical imaginary refers to the speculative, propositional fabric of medical thought, the generally disavowed dream work performed by biomedical theory and innovation … the fictitious, the connotative … desire. (Waldby Citation2002)

Here it is important to note that value is not purely economic. Rose and Novas Citation(2004) note three dimensions to biovalue:

… life is productive of economic value … that the manipulation of life generates a value accorded to the enhancement of health.… the production of both wealth and health is bound up with ethical values.

These transitions are evident in a widening number of high profile promissory fields commanding sizeable investment (genomics, pharmacogenetics, etc.) in addition to stem cell science under discussion here. Crucially, hope is foundational to the very production of capital itself. As Moreira and Palladino put it (2005, p. 69):

capital … demands a belief in a future rather than a resignation to, or an investment in, the present. The future, rather than the past, is this regime's distinctive temporal orientation. Continuous opening of action, with no point of return, is its strategic aim.

Markets in bioscience are increasingly dependent upon the participation of multiple constituencies collaborating in the establishment of such “communities of promise” (Brown Citation2003, Martin et al. Citationforthcoming). These links between markets and promissory expectations depend on the mobilization of publics as active consumers within newly neo-liberalized bioeconomies. New “political economies of hope” mediate between patient organizations and pharmaceutical companies, representing new arrangements for “benefit sharing” the dividends (Novas Citation2007). Brown and Kraft Citation(2006) write of active consumers and prudently responsible parents mobilized through commercial cord blood banking. Crucially, the internet has been central in the establishment of new direct relationships between consumers and biomedical industries (Fox and Rainie Citation2002, Nettleton et al. Citation2005). Cord blood banking echoes neo-liberalizing processes found across biomedicine where the state is increasingly seen to “take a back seat”, regulating standards but devolving decision making to the market and the consumer (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim Citation2002, Salter and Jones Citation2002).

In what follows we apply these related notions of promissory political economy to a growing market in the commercialization of stem cells and the deposition of cord blood by new parents. We focus on the capitalizations of hope, a future-oriented regime that goes far beyond discourse to become embedded in the structure of markets, and the mobilization of biological capital globally.

This survey examines the scale, scope and focus of the global cord blood banking industry. A comprehensive list of international cord cell banks was generated from web directories (A Parents Guide to Cord Blood Banks: http://parentsguidecordblood.org/content/usa/banklists/index.shtml?navid), industry databases (GEN, ReCap), and press release archives (NewsAnalyzer). A total of 194 banks were identified and data on all banks collected and cross-checked with websites, annual reports, etc.

Additional detailed information was generated from the largest banks (defined as having more than 5000 units of cord blood stored – see ), drawing on company websites and press releases describing activities and expectations. For practical reasons the main focus of detailed analysis was on resources that were in English and, as a consequence, developments in North America, the UK and Australasia are the main focus of this paper.

Table 1 Leading public and private cord blood banks (>5000 units in 2007).

The data represent a combination of quantitative and qualitative material on the scale, size and capacity of the contemporary cord blood economy and its development over recent years. The research also focused on a number of key claims made in documentary reports (usefulness of UCB banking and expectations associated with it), and the differences between public and private banking.

The emergence of cord blood banking

The development of cord blood stem cell transplantation has emerged over a 30-year period (see ). Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the immortal precursors of the blood and immune system and were the first type of stem cell to be routinely used in the clinic since the 1980s to reconstitute the blood and immune system following aggressive radiotherapy in the treatment of leukemia. The first clear evidence that stem cells existed in UCB came in 1974, but it would take a further 14 years for the existence of HSCs in cord blood to be used clinically in the first successful cord blood transplant to regenerate blood and immune cells in a child suffering from Fanconi's anemia (Gluckman et al. Citation1989, Brown et al. Citation2006). This proof of principle led to the first public and private cord blood banks in 1992.

Table 2 Timeline of key events in the development of cord blood stem cell transplantation.

A key distinction in this field is between autologous and allogeneic transplantation – the former referring to cells from the self (i.e. one's own cord blood which has been frozen at birth), the latter referring to related or unrelated tissue-matched donors. The first transplant from unrelated donors was carried out in 1993 leading to a steady growth in the number of autologous and allogeneic cord blood transplants undertaken internationally, although these are still relatively small in number and restricted to certain forms of cancer and rare genetic diseases. Expectations surrounding the field were initially limited to a small niche set of applications focused on childhood oncology.

A major shift in the promissory value of cord blood started to occur around 2000, as part of the more general emergence of regenerative medicine as a new field of hope (Brown et al. Citation2006) with much greater emphasis placed on the plasticity of stem cells in general and cord blood stem cells in particular to differentiate into a range of other tissues. This has precipitated a shift from seeing cord blood as just an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplants for children to a potential therapy for a number of degenerative diseases in both adults and children. It is this latter promise that has spurred the rapid development of commercial cord blood banking.

Overview of the cord blood banking sector

The growth of cord blood banking

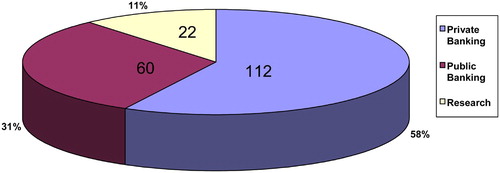

The survey of the global cord blood banking sector revealed three distinct, but overlapping banking sectors (), including 60 not-for-profit “public banks” usually based in the charitable, hospital or university sectors accepting samples by donation for allogeneic (non-self) transplantation; 112 commercial banks charging for storage, aimed at either autologous applications or use by closely related family members (allogeneic); 22 private biotechnology companies involved in R&D developing novel cord blood stem cell based therapies, as well as those manufacturing cord blood storage and processing devices. These categories are largely heuristic with fluid boundaries separating sectors. For example, a number of research companies also operated cord blood banks for use in therapy and the distinction between the public and private sectors was blurred by the existence of “hybrid” public/private banks (see below).

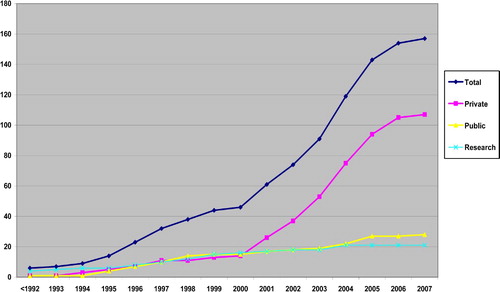

shows the historical growth of the three sectors since the early 1990s. There were only a handful of banks prior to 1996 followed by steady public and private growth until 2000, at which time there were roughly similar numbers of each. Crucially, we see parallel growth rates throughout much of this decade followed by a dramatic escalation in the commercial/private sector after 2000Footnote1 coinciding with several seminal events in the world of stem cell biology (mammalian cloning in 1997, the isolation of human embryonic stem cells in 1998 and increased interest in the potential plasticity or multipotency of adult stem cell types such as HSCs).

clearly shows the point at which a space begins to open up in both the growth rates, but also in the contrasting logics, of commercial and public cord blood banking. The rapid upturn in commercial banking rests fundamentally on the future-oriented promissory value of regenerative medicine, a “regime of hope” embedded largely in future potential rather than present utility. The stated aims of commercial and public banks are discussed at greater length below, but illustrate this patterned distribution of the public sector to the present, and the commercial sector to the future.

Another feature of the growth of the private banking sector is that the highly accelerated growth rate after 2000 began to slow significantly from 2005. This perhaps reflects an increased focus in public commentary on the obstacles facing the regenerative medical promise, as research and clinical communities have become more familiar with the difficulties of realizing early ambitious potential. Indeed, many of the original indications of adult stem cell plasticity associated with HSCs have been very heavily contested lately and the field as a whole continues to be characterized by acute uncertainty.

The leveling off of growth parallels other findings from the sociology of expectations where alternations in cycles of high expectations are followed by more modest realizations of the contingencies upon which new technologies depend (Brown et al. Citation2000). The phenomena of early promise/later disappointment suggest a temporal pattern in which dazzling expectations and promise are important in mobilizing early support, garnering resources, securing investment and encouraging involvement. But in time however, research communities are often likely to be confronted by problems that could not at first have been anticipated, as well as greater uncertainty about the original promise.

Spaces and places: geography of cord blood banks

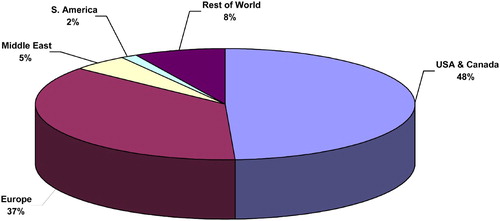

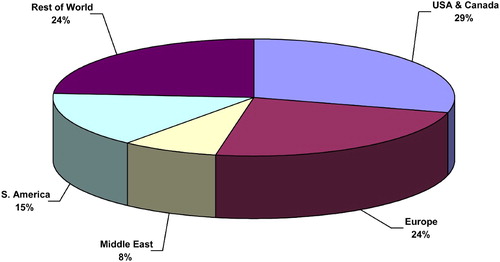

Other contrasts across public and private banking are geographical. shows the regional distribution of public banks, which closely maps to the geography of biomedicine as a whole. For example, North America has nearly half of all public banks, while Europe accounts for nearly another 40%. The remainder is spit between the Middle East (5%) and the rest of the world (8%). The US has the most public banks (30), Italy has 11 and Canada, Germany, Belgium and Israel have two each. The data on the distribution of private banks () are strikingly different; here North America (29%) and Europe (24%) account for just over half of all banks, with the rest of the world (mainly East Asia and Australasia) constituting nearly a quarter of the industry. South America (15% of total) and the Middle East (8% of total) are well represented. The US has 28 banks, Canada 10, the UK nine, Brazil seven and Germany five. Furthermore, the top five banks by number of samples held (see ) are based either in the US or the UK, and together represent nearly 70% of all samples. Sizeable banks have also been established in China, Singapore, Japan and Jordan. The growth of private cord blood banking has therefore involved the constitution of a new geography of promise, in which countries and regions not traditionally centrally involved in biomedical research are starting to play a leading role. More importantly, this geography illustrates the spatiality of a regime of hope focused initially on the US and the UK, but with Asia and the near east closely following.

Number of samples banked and commercial value

The survey generated detailed information on the number of cord blood samples held by different banks () and the fee charged for both the initial collection and annual storage. In total some 881,000 samples were held by private firms, with a further 66,200 held by the six largest public banks. Together these give a total of nearly 950,000 banked cord blood samples and it is highly likely that the total exceeds over 1,000,000 samples if the other 100 + banks for which we do not have detailed data are included.

Private banking is also highly concentrated with just four banks holding over 100,000 samples and 13 holding more than 10,000. It is notable that of this latter group, eight were founded before 2000, including all six US firms. A similar pattern exists with respect to the public sector, with all six leading banks founded before 1998. This suggests that while the main growth in banking has taken place since 2000, it has been incumbent banks established during the 1990s that have been the main beneficiaries of the turn to regenerative medicine.

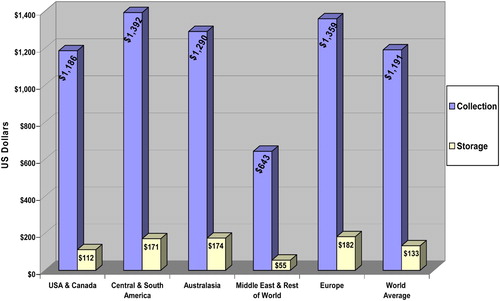

Finally, in nearly all regions the average cost of collecting a cord blood sample at birth is in excess of US$1000 and the average cost of storage is in excess of $100 a year (). Only in the “Rest of the World” category was the cost significantly less. Assuming that the private sector held over 1 million samples at the end of 2007 suggests an annual recurrent income of approximately $100 m a year and a nominal current value in excess of $1 billion based on the average cost of collection. If we assume a current 10% annual growth rate (justified by historic growth rates of leading banks over the last decade), a further 100,000 samples would be banked each year ($100 m), putting annual revenue for the sector at approximately $200 m. While modest compared to pharmaceuticals, this is a highly profitable source of revenue.

The following sections draw on the general survey data, as well as the more detailed profiling of leading banks to outline what might be called the regimes of biovalue production associated with the public and private banking sectors. The final section will then go on to examine hybrid banks and the way the public and private sectors, and the present and the future, are entangled with each other.

Public cord banking: a “regime of truth”

Public cord blood banking has been positioned principally within a body of claims that can be characterized as a “regime of truth”, legitimated on the basis of current present-oriented “evidence-based” support for existing applications of CB stem cells (Moreira and Palladino Citation2005, Brown Citation2007, see ), contrasting sharply with a future-oriented “regime of hope”. The institutional loci of this regime are public healthcare systems, where banks operate as small-scale services for allogeneically treating children with hematological cancers and rare genetic diseases. Usually, patients are from ethnic minorities with rare HLA sub-types. The New York Blood Center's National Cord Blood Program (NCBP), the largest public bank in the world with over 30,000 samples, epitomizes the rationale. It was established in 1992 as “a full-service public bank of frozen, ready-to-use cord blood units donated by delivering mothers for use by any patient who might need a stem cell transplant” (www.nationalcordbloodprogram.org; accessed December 2007). By September 2006 some 2199 cord blood transplants had been undertaken using NCBP units in 199 centers in over 30 countries worldwide, representing about a third of all cord blood transplants undertaken. Seventy-two per cent of these transplants were given to children under the age of 18 and 50% were to “non-Caucasians” (ibid.). In this context, it is striking that “American blood” is being exported internationally and distributed all over the world.Footnote2

Table 3 Key dimensions of the regimes associated with the public and private cord banking sectors

Of the 37 (of 60) public banks for which detailed data were available, only two (the University of Arizona Cord Blood Bank and the University of Iowa's Hematopoietic Stem Cell Bank) mentioned regenerative medicine and both collected samples for research use with the aim of investigating both improvements to established procedures as well as regenerative medicine, and generally placing the latter far into the future. Expectations of public banks focused around improving the use of cord blood in its current application as an alternative to bone marrow transplantation with several working towards possible “cell expansion” and the hope of treating adults.

It is clear that in every case, the value created by these public banks is not as a form of economic capital, but rather has a moral and utilitarian value for health. These biological samples are not commercialized or traded, but instead provide a resource for public healthcare and the treatment of patients living in the here and now. Within this moral economy the transaction of placing a sample of cord blood in a bank is constructed as an altruistic “gift to strangers”:

By donating your cord blood to us after the birth of your baby, you are making a voluntary donation that could help any patient who is in need of an unrelated cord blood transplant … (UK National Blood Service: www.blood.co.uk [Accessed 18 November 2007])

Public banks also stress their difference from the private banking by, first, highlighting that private banking is a highly speculative enterprise and that the public sector aims to meet current needs for existing therapies:

Private companies offer to store cord blood for anyone who wants it done, whether or not there is any medical reason known to do so at the time. … private storage is for purely speculative purposes … parents should know that a child's own cord blood … would rarely be suitable for a transplant. It could not be used at present to treat genetic diseases because the cord blood stem cells and their descendents would be affected by the same condition … physicians would not use a child's own cord blood to treat leukemia.

(National Cord Blood Program: www.nationalcordbloodprogram.org/donation/public_ vs_private_donation.html [Accessed 18 November 2007])

Furthermore, the public banks are more conservative than the private firms in their estimates of the likelihood that a banked sample will ever be used for transplantation.

In summary, public banks refrain from mobilizing the future in constructing biovalue, and stress instead currently proven therapeutics within a “regime of truth” oriented to a moral economy of altruistic mutuality. At the same time, public banks are involved in ethical boundary work in which private banking is cast as a speculative and morally questionable enterprise:

The odds of finding a suitably-matched, publicly-donated, unrelated cord blood unit are already quite high. … Many physicians do not recommend private cord blood banking except in cases where a family member already has a current need or very high potential risk of needing a bone marrow transplant. In all other cases … the use of cord blood as “biological insurance” [is] “unwise”.

(National Cord Blood Program www.nationalcordbloodprogram.org/donation/public_ vs_private_donation.html [Accessed 18 November 2007])

This is not to suggest that public sector banking is completely divorced from questions of promissory potential or vision. The whole ethos of a moral economy of gift upon which public blood services rely is highly value-based and, to that extent, fundamentally linked to an aspirational discourse of public good, and solidaristic communitarian goals.

Private cord banking: a regime of hope

In contrast to the public banking sector, the regime of biovalue creation centered on private banking has a different composition and rationality expressive of a “regime of hope” (see ). The institutional loci of the regime are commercial enterprises, established as for-profit private “family” banks as services, stored for future use by the child or family member. In general, their appeal is to autologous applications (i.e. using one's own cells) for either current disease indications (cancer or rare genetic diseases) or future regenerative therapies.

Biovalue takes the form of economic capital for the company involved, but also a speculative investment for parents banking their child's blood, as stem cells increase in future value through as yet unknown treatments. In general, private banks ally themselves with a broad spectrum of both present and future applications. Of 64 (out of 112) private banks for which detailed information was available only seven were focused solely on existing applications in oncology and hematology, with the remaining 57 working on regenerative medicine (12 banks) or covering both, with a greater emphasis on yet to be developed therapies (45 banks). Typically indications listed by private banks include: tissue repair, heart disease, diabetes, neurodegenerative conditions, cancers and blood disorders. Private banks rarely discriminate between expectations surrounding these indications, suggesting the imminent appearance of novel cures in the not-too-distant future:

Many experts describe the current time as an “inflection point” in science and medicine and believe that individuals who bank their cord blood stem cells will be in a position to take advantage of the many developing technologies involving stem cells.(www.cordblood.com/cord_blood_banking_with_cbr/common_misconceptions/index.asp [Accessed August 2007])

New medical technology may well use these cells to rebuild cardiac tissue, repair damage due to stroke or spinal cord injuries and reverse the effects of such diseases as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's. (www.cryo-cell.com/services/treating_diseases.asp [Accessed August 2007])

Another important difference from the public banks is the expectation that banked samples have a reasonably high chance of being used. This is well illustrated by the following statement from the Cord Blood Registry, which has a section on their website on common misconceptions, one of which is listed as “Odds that a family will ever need their banked cord blood are so low that people shouldn't bother doing it.” In response they argue that:

… according to medical research, the odds that a child will someday need to use his or her own newborn stem cells for current treatments are estimated at 1 in 400. Odds that the newborn or a family member may benefit from banked cord blood are estimated at 1 in 200.

(www.cordblood.com/cord_blood_banking_with_cbr/common_misconceptions/index. asp [Accessed August 2007])

The private banks encourage parents to bank cord blood through a series of promissory, practical and moral arguments. First is the promise that cord blood may become an invaluable biological resource in the future, tying into regenerative medical markets. Second, that banking cord blood offers reassurance (“peace of mind” according to Cells Limited) that is a “gift in itself”. Third, that the potential of cord blood is being offered at a cost parents cannot reasonably refuse. Within this moral economy the transaction cost of deposition is constructed as a form of biological insurance with promissory value for one's family, where parents are under an ethical duty to look after their child's future.

In justifying using a private rather than a public cord bank, companies mobilize a number of arguments, as illustrated by ViaCord:

Public cord blood banking stores cord blood … available to anyone … Those who donate their cord blood to a public bank are not guaranteed that it will be available if it is ever needed for their own family.… A family cord blood bank stores your newborn's cord blood stem cells exclusively for your family … private banking eliminates the need to search for a matching donor for the child and the uncertainty of trying to source cells from a public bank.

(www.viacord.com/private-public-banking.htm [Accessed January 2008])

Here the appeal is to self-interest, certainty and convenience. Furthermore, anxiety is evoked about the possible use of the child's cells by someone else, thus inverting the traditional view of altruism as a “gift to strangers”.

In summary, private cord blood banks actively mobilize the future in how they construct the value of cord blood. In particular, promissory regenerative therapies are seen as inevitable and in this context parents have a moral responsibility to their family to invest in cord blood banking as a form of biological insurance. The rationality at work here is that of a speculative market in which consumers choose private banks as a means of taking advantage of the latest advances in science and technology.

Flows: hybridizing presents and futures

While distinguishing between the public and private regimes of value, it is also important to consider the two domains as intimately entangled. It many senses, this relates to the mutual constitution of the future in relationship to the present, or the “parasitics” of hope and truth (Moreira and Palladino Citation2005). The hope for promissory therapies is built on the proven success of established techno-practices in oncology and hematology. While almost none of the public banks invested in the promise of regenerative medicine, the great majority of private banks relate their services to both current applications and the future potential of regenerative medicine.

Nowhere was this entangling of truth and hope more visible than in the case of three private banks that operate dual or “hybrid” models: the US Cryobanks International, the Canadian Cord Blood Registry, and the UK's Virgin Health Bank. The Canadian Cord Blood Registry offers parents three options for banking their child's cord blood (public, private, and in a collection for families with a history of hematological and genetic disease). Its Director justifies this choice as follows:

Debate continues on whether cord blood storage should be carried out only in the public [or private] arena. … swift advancement in stem cell science … has forced me to rethink public versus private … storage. If we use cord blood only for transplantation to regenerate blood cells as is the current practice, private storage is of questionable value. However, if we are considering the use of cord blood stem cells for cellular therapy, organ repair or organ regeneration, then self storage is the better option.… As we move towards the day that this revolution in medical care becomes reality, self stored cord blood stem cells … will be priceless, personal-health investments. … I have decided to offer parents the opportunity to donate … or to store it privately for future personal use. (www.ccbr.ca/letter_from_our_director.htm [Accessed January 2008])

Here the choice between the present and the future is still left to the consumer, but Virgin take this a step further by spanning the divide between the public and the private domains, splitting units with 80% going into a public bank and 20% retained for private use. This is justified as having benefit for both family and strangers, and for existing and future patients:

collecting cord blood stem cells increases the availability of donated matched stem cells (allogeneic transplants) and, we believe, the future potential of regenerative medicine treatments using your own stored stem cells (autologous transplants). (www.virginhealthbank.com/SavingCordBloodStemCells.html [Accessed August 2007])

In contrast to many private banks stressing autologous transplantion, Virgin note that “in your child's early years; their own stem cells are unlikely to help if they fell ill – they'd need healthy, donated cells” i.e. from a public bank. Furthermore, while they share the same sorts of expectations of cord blood as most private banks, these developments are placed on a much longer timescale:

The promise of regenerative medicine is not here today. However … expert scientists … believe that its potential could bring many benefits with new treatments for certain illnesses and conditions. To take advantage of this possibility – and this is where the private banks are useful – you'd need to have stored cord blood stem cells. (www.virginhealthbank.com/SavingCordBloodStemCells/WhyConsider.html [Accessed August 2007])

However, they caution that it would be “irresponsible” to suggest that this research is guaranteed to become a reality. Virgin also more conservatively estimate potential use in a child's early years at between 1 in 5000 and 1 in 20,000 (contra “1 in 200” quoted by the Cord Blood Registry; see above). Virgin's view occupies a hybrid space where regimes of truth and hope coexist. Nevertheless, regenerative medicine is still the underlying rationale for the bank. In this context it is interesting to note that while the 80% of the sample in the public part of the bank is valuable today, the 20% stored in the private part of the bank is too small for therapy and can only become useful if new cell expansion technologies are developed. The value of donation is predicated on a level of future scientific progress that remains greater than that suggested by most other private banks.

Conclusions

This paper has explored the key role of future expectations in the development of what might be called a promissory bioeconomy. In particular, we have focused on the creating of biovalue and explored how hope itself has become a commodity that has a major role in the formation of new firms, services and markets. In doing so, we have elaborated on the idea that these constitute “regimes of hope”, which involve the co-construction of a particular set of expectations, novel socio-technical systems, and new economic, technical and ethical rationalities. That these represent relatively new rationalities is evidenced in the timelines of recent CB banking developments (see above) in addition to new logics of deposition in the private CB banking sector.

The contrast between the public and private cord blood banking sectors has enabled the detailed analysis of the creation of biovalue in these two domains following the emergence of regenerative medicine after 2000. The promises that surround regenerative therapies have become embodied in a wave of private investment and the creation of a large number of new companies. By 2007 cord blood banking had become a sizeable international industry with annual revenues of over $200 m. It also shifted the locus of the global tissue economy away from Europe and North America through the emergence of new promissory geographies in East Asia and Latin America.

A number of different characteristics that mark regimes of truth and hope can be identified along the three dimensions outlined above (see ). In terms of economics, public banks operate outside the market economy and are not driven by the profit motive. Instead their rationale is to deliver value for health by treating patients in the present. In contrast, private banks are creating economic value by capitalizing on the hopes of parents for future regenerative therapies. In constructing this regime of hope, many boundaries are drawn and issues contested, including the timescale of progress and the likelihood of using samples. The two domains also have competing ethical rationalities, with public donation seen as an act of altruism for the benefit of the common good. In contrast, private deposition is a matter of consumer choice and family responsibility to one's kin.

As highlighted in the discussion of dual/hybrid banks, the present and the future are closely entangled. The future of regenerative medicine is mobilized in the present to promote innovation and technical change and to stimulate consumer markets. At the same time, future hopes draw heavily on past and current achievements; promises have to build on previous successes and the confidence that these will be repeated.

The constitution of this regime of hope around cord blood stem cells demonstrates the way new promissory technologies, novel therapeutic applications, and new types of consumers motivated by changing moral imperatives are co-constructed. These all rest on the expectation that scientific and technological development will usher in a new era of regenerative medicine. Yet, it must be stressed that this is a process of mutual creation where the realization of the future can only come about through the present development of wider socio-technical relationships. Future technologies must depend on the contemporary alignment of institutions, investment, professional practice and consumer demand. The emergence of a regime of hope in the cord blood field is a prerequisite for the realization of these promises and their conversion into a regime of truth for the treatment of future patients. The capitalization of hope and the circulation of expectations as promissory commodities therefore depend on the embedding and embodiment of futures in the heterogeneous web that constitutes the new bioeconomy.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on original research carried out under an ESRC Stem Cells Initiative grant: “Haematopoietic stem cells: the dynamics of expectations in innovation” held by Paul Martin (PI), Nik Brown, Alison Kraft and Philip Bath.

Notes

1. It is hard to generalize about the growth of public banking as we only have data on the start dates of ~60% of the public banks (compared to 90% of the private banks), so it is possible that their growth may have also increased following 2000. However, careful analysis of the geographical distribution of the banks with missing data and modeling of different scenarios suggest that this is highly unlikely.

2. This calls into question the extent to which donors are aware of the strangers who they are helping. Busby and Martin Citation(2006) have argued that tissue donation involves a gift to a recognizable imagined community, whose boundaries may be national. As a consequence, exporting samples for transplant therefore raises the issue of how strange a stranger can really be?

References

- Beck, U., and Beck-Gernsheim, E., 2002. Individualisation: institutionalised individualism and its social and political consequences. London: Sage; 2002.

- Brown, N., 2003. Hope against hype: accountability in biopasts, presents and futures, Science Studies 16 (2) (2003), pp. 3–21.

- Brown, N., 2007. Shifting tenses – from regimes of truth to regimes of hope?, Configurations 13 (3) (2007), pp. 331–355.

- Brown, N., and Kraft, A., 2006. Blood ties – banking the stem cell promise, Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 3/4 (2006), pp. 313–327.

- Brown, N., Kraft, A., and Martin, P., 2006. Imagining blood – the promissory pasts of haematopoietic stem cells, Biosocieties 1 (3) (2006), pp. 329–348.

- Brown, N., Rappert, B., and Webster, A., 2000. Contested futures: a sociology of prospective techno-science. Aldershot: Ashgate Press; 2000.

- Busby, H., and Martin, P. A., 2006. Biobanks, national identity and imagined genetic communities: the case of UK biobank, Science as Culture 15 (3) (2006), pp. 237–251.

- Ferreira, E., et al., 1999. Autologous cord blood transplantation, Bone Marrow Transplantation 24 (9) (1999), p. 1041.

- Fox, S., and Rainie, L., 2002. Vital decisions: how internet users decide what information to trust when they or their loved ones are sick. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2002.

- Gluckman, E., et al., 1989. Haematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with Fanconi's anaemia by means of umbilical-cord blood from an HLA identical sibling, New England Journal of Medicine 321 (1989), pp. 1174–1178.

- Hedgecoe, A., and Martin, P., 2003. The drugs don't work: expectations and the shaping of pharmacogenetics, Social Studies of Science 33 (3) (2003), pp. 327–364.

- Knudtzon, S., 1974. In vitro growth of granulocytic colonies from circulating cells in human cord blood, Blood 43 (3) (1974), pp. 357–361.

- Kurtzberg, J., et al., 1994. The use of umbilical cord blood in mismatched related and unrelated haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Blood Cells 20 (2–3) (1994), pp. 275–284.

- Martin, P. A., Brown, N., and Kraft, A., Communities of promise: blood stem cells in the unmaking, Science as Culture, In press..

- Moreira, T., and Palladino, P., 2005. "Between truth and hope". In: History of the Human Sciences. Vol. 3. Parkinson's disease, neural transplants and the self; 2005. pp. 55–82.

- Nettleton, S., Burrows, R., and O'Mally, L., 2005. The mundane realities of the everyday lay use of the internet for health, and their consequences for media convergence, Sociology of Health and Illness 27 (7) (2005), pp. 972–992.

- Novas, C., 2007. "Genetic advocacy groups, science and biovalue: creating political economies of hope". In: Atkinson, P., Glasner, P., and Greenslade, H., eds. New genetics, new identities. London: Routledge; 2007. pp. 11–27.

- Rose, N., and Novas, C., 2004. "Biological citizenship". In: Ong, A., and Collier, S., eds. Global assemblages: technology, politics, and ethics as anthropological problems. Oxford: Blackwell; 2004. pp. 439–463.

- Salter, B., and Jones, M., 2002. Human genetic technologies, European governance and the politics of bioethics, Nature Reviews Genetics 3 (2002), pp. 808–814.

- Van Lente, H., 1993. Promising technology: the dynamics of expectations in technological development. Enschede: Department of Philosophy of Science and Technology Enschede University of Twente; 1993.

- Waldby, C., 2002. Stem cells, tissue cultures and the production of biovalue, Health 6 (2002), pp. 305–323.

- Waldby, C., and Mitchell, R., 2006. Tissue economies: blood, organs and cell lines in late capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2006.