Abstract

In the emerging context of the knowledge economy, exploring how both the global economic environment and national context influence local research practices is of crucial importance. The Hwang scandal in South Korea illustrates a typical research practice geared towards the exploitation of labor and human resources in response to, and as part of, global competition in the life sciences. This article argues that the ongoing exploitation of young talent and labor in the Korean academic community, even after the scandal, represents the combined outcome of actors' interests, organizational power structures, and strategies of survival in a global knowledge system that constrains the conductivity of actors. Competition and exploitation are internalized in the self-governance of the life sciences, despite avowed commitments to more rational and democratic research practices at the institutional level.

Introduction

Much discussion has taken place on the regulative trajectories of stem cell research, both in Europe and in East Asia (Sleator Citation2000, Park Citation2004). An academic trend focusing on local particularities to explain different regulatory practices reflects the difficulty of reaching a global consensus on how best to guide research practice. In the case of East Asian countries, such as China and Korea, their cultures and status as “developing countries” are often quoted as undermining the effective regulation of stem cell research (Gottweiss and Triendle Citation2006), but little discussion takes place as to how different local cultures represent common global problems by which problematic cultural practices are reproduced.

This article argues that the emerging knowledge economy, which contributes not only to commercializing biotechnology research but also to the formation of micro-level human behavior, introduces a novel challenge to the effective regulation and sustainable governance of local research and research communities. While commercialization forces industry and academia to imitate each other's practices and organizational behaviors, it has been observed in the US biotechnology community that the convergence of research cultures exhibits an asymmetrical effect: whereas industrial researchers generally benefit from adopting a system that encourages academic autonomy and vibrant organizational cooperation, academics in universities generally lose their traditional autonomy and become more secretive and competitive, and less trustful of each other (Kleinman and Vallas Citation2006). This trend has also become an overwhelming problem in the Korean life sciences, although with some unique local manifestations.

The drive for commercialization in the knowledge economy undoubtedly provides an incentive for biotechnology research, especially in the industrial sector. In South Korea, however, scientific competition has mainly had negative effects on research communities. In South Korea, where the spirit of competition is emphasized without the necessary industrial–academic cohesion to support the research, fierce competition, especially in academia, has produced a vicious cycle of problematic scientific practices, such as fraud, coercion, and exploitation. This vicious cycle occurs in conjunction with individual actors' use of unsustainable survival strategies within this constrained environment. This problem continues to be observed in South Korea, even after the Hwang scandal.

The notorious 2005 Hwang scandal, involving the fabrication of experimental results and the coercion of junior female researchers to donate their oocytes, has inspired global reflection on the need for tighter ethical regulation of stem cell research. As I have argued elsewhere, Hwang and his colleagues' misconduct reflects many complex problems typical of South Korean society – one that leaves little room for spontaneous reflection on scientific practice and knowledge in general (L. Kim Citation2008). To further expand on the underlying influence of national culture, more explanation of the complex interactions of the Hwang scandal is required. Although culture itself is an important variable, the intersection of actors' interests, organizational power structures, and local strategies of socio-economic survival articulate national characteristics that are coupled with the global influence of the knowledge economy. The global mode of scientific production, micro-power relations between people and the way such power is exercised seem to reproduce Foucault's “conduct of conduct” (Dreyfus and Rabinow Citation1982) in the national context. As I demonstrate through a series of interviews, these variables shape and reshape local cultural characteristics.

By briefly reviewing the Hwang affair, as an introduction to my argument, I raise some new questions. Despite South Korea's successful transition from an authoritarian state to a democratic society over the last decades, why have many South Korean laboratories, including Hwang's, failed to establish a more democratic and rational research practice? Is the Hwang scandal merely representative of problems typically observed in “developing” countries? Or are there more fundamental, external factors related to global governance that significantly limit the choices available to individual actors and organizations? If so, what are the structural constraints, other than national and individual factors, that can be incorporated into a systematic reflection of both local and global stem cell research practices?

In an effort to answer these questions, I will review Hwang Woo-Suk's scientific experiments, explaining the structural constraints that eventually led to scientific disgrace. I argue that Hwang's case reflects the asymmetric effects of competition on institutions and actors in South Korea under the constraints of the global knowledge economy.

Research methods and data

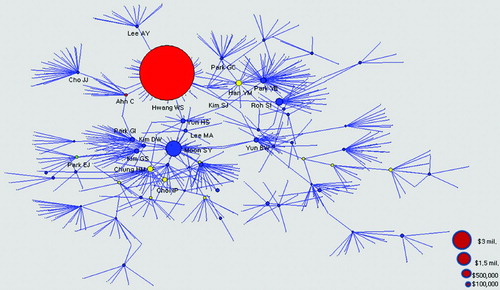

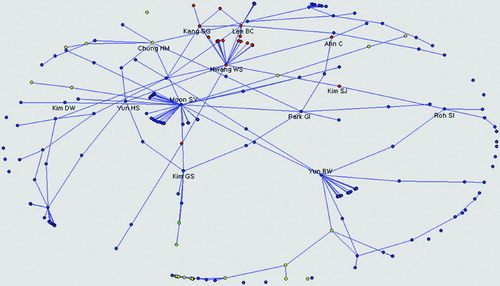

To review Hwang Woo-Suk's trajectory, I researched his alliances with scientific actors during the critical 2004–2005 period. I interviewed the chief investigator who interrogated Hwang and researchers who were involved in the collaborative work. Social network analysis (SNA) was applied to map life scientists' social relations that represent collaborations among stem cell laboratories that received governmental grants under the 21st Century Frontier Project. The visualized results identify core actors in the network, and reveal their alliance strategies as well as the overall characteristic of the collaborative network (de Nooy et al. Citation2005). The raw data used for the network coding were collected from the official documents stored in KORDI (Korea Research and Development Integrative Management System) in November 2006. To trace the research environment after the scandal and to substantiate my findings, I also conducted an ethnographic study with students, researchers and stakeholders in the scientific field.

New challenges in the knowledge economy

While Hwang's celebrated image of Korean science and technology faded away after he was charged with fabricating stem cell experiments that shocked the global stem cell community, the Korean public's urge to support him remains intact. This supportive sentiment partly stems from the limitless pressure to compete in a globalizing world, as many Koreans have a fixed notion that science should serve as a vital instrument in carrying out the global economic struggle (L. Kim Citation2008, Citation2009). Although this phenomenon might appear to be a local representation of the generalizing term “bionationalism” (Gottweis and B. Kim Citation2009), neither “bio” nor “nationalism” is predominately reflected in the Korean public's reaction. For the concrete political–economic base of “bio” has yet to fully develop or integrate into Korean society, and rhetorical expressions of nationalism conceal individual motivations and desires lying behind ritualistic support for Hwang and his research, as they embody a sentiment of criticism and distrust of official institutions that have failed to deliver responsible accounts of science to the public (J. Kim Citation2009). Therefore, the term “bionationalism” is an overly generalizing term.

The new stem cell science, with its messiah-like promises for medical application and economic profit, provided the Korean people with hope and relief and gave them confidence in a society fraught with competition. The typical attitude in South Korea that regards science as an “economic engine” dates back to the era of the developing state when Park Jung Hee's military regime rushed to industrialize the country in the 1970s (H. Kim Citation2006). No wonder its legacy has had an undeniable influence on the current role of the life sciences. But the sense of urgency for a quick scientific solution, felt by scientists and lay people alike, stemmed from the idea that the “knowledge economy” was essential for future survival. Especially after the financial crisis in 1997, Korea promoted “venture enterprises” to boost Korea's economy. The fortuitous “dot-com” boom helped the Korean economy quickly recover in the early 2000s, but the market was soon saturated and dominated by a few aggrandized IT companies. Subsequently, the government designed its “National Basic Plan for Science and Technology (2002–2006).” This scheme was inherited by the ascending Roh Moo Hyun administration, which saw biotechnology as a promising “growth engine” for the future economy, and used it to politically legitimize the new policy.

The nationwide aim to make science and technology lucrative, and therefore “worthywhile,” had a penetrating impact on academic life as well. Universities were required to produce star scientists and exhibit concrete results for commercialization. So-called “neo-liberal reform” began to use quantified methods of evaluation to assess universities' and individuals' academic performance. Hence the number of publications in reputable Science Citation Index journals became crucial for scholars and universities, as academic promotion and education budgets were to be decided on the basis of quantitative criteria. Universities also rushed to adopt profit-making “spin-off” practices, resulting from the prevailing belief that this trend reflected a zeitgeist for the orientation of academic knowledge, which could be adapted to industrial needs.

By the middle of the decade, it became evident in South Korea that the codes and practices of industry and academia in scientific research were increasingly traded across the boundary between the two, stimulated by the urge to collaborate in an effort to make scientific knowledge profitable. A few entrepreneurial scientists could start their own business successfully by seizing an opportunity in the expanding biotechnology market. At the same time, a number of academics came to experience intensifying competition and pressure to survive under the new evaluation system, inducing them to utilize whatever means and resources at their disposal to exploit the situation.

In addition to the challenges encountered in academia, the industrial sector in South Korea remains fragile: there are still very few biotechnology firms that are sizable and competent enough to guarantee successful, long-term research (Shin Citation2009). Compared to the economic success achieved in IT, biotech enterprises require more starting capital and more enduring investment to be profitable. Korean academics were noticeably overwhelmed by commercial and competitive pressures, which in turn encouraged a labor-exploitative model in research and rent-seeking behaviors as a solution. In retrospect, Woo-Suk Hwang's laboratory and his collaborators represented a possible outcome of all these elements.

Scientific networks and structural constraints

Hwang's laboratory was well known for its massive size by the time he published his article in Science. It started with only five researchers in 1986, but increased to 23 by 1999, and finally became a “clone factory” with 60 employees by 2005. The main stimulus for this expansion was the news of cloning Dolly the sheep in 1998. After this groundbreaking news, many people immediately saw its future potential for applications of somatic cell nuclear transplantation (SCNT).

The main source of funding did not come from stem cell research grants until 2005, but came from the already established animal cloning technology supported by the government (G. Kim Citation2007, p. 139). Thus, the team had to appropriate other short-term grants, and make a strategic alliance with another group that had already been granted government funding for stem cell research, the medical team of Dr Shin-Yong Moon based at Seoul National University. As the Korean government applied a “select and focus” strategy to support profitable scientific research (L. Kim Citation2008), there was only one group that could secure a sizable grant for the project.

Hwang's team also had to rely on other experts from MizMedi hospital and Seoul National University medical teams for the derivation of stem cells. The contribution made by Hwang's own stem cell team, having a veterinary science background, was limited to the technical SCNR process, whereas other, unfamiliar, procedures, such as extracting the inner cell mass from the blastocyst and culturing stem cell lines, were left completely to two experts at the MizMedi hospital. Jong-Hyuk Park and Sun-Jong Kim, the two medical researchers, fabricated the experimental results in 2004 and 2005.

According to the prosecutor's report (Anon Citation2006), the main motive of the medical researcher's initial fabrication derived from the great pressure exerted by Hwang to produce results, and to derive cloned stem cells, as soon as possible. Sun-Jong Kim testified that he was skeptical whether it was feasible that the seeded blastocyst would grow to form a colony, so he mixed the inner cell mass with an embryonic stem cell clump brought from the MizMedi hospital. Kim reported to Hwang that he grew and derived embryonic stem cells from the inner cell mass, but the stem cell was the one brought from MizMedi.

Despite his groundbreaking “success” in 2004, Hwang was in a great rush to produce results as soon as possible, even if it meant fabricating them. While Hwang's personal ambition may be one reason for this, his structural location in the South Korean stem cell research community, as revealed in the social network analysis diagram, may provide another clue for a sociological explanation. and illustrate the collaborative networks of stem cell researchers who were granted governmental funding. As the main source of research funding comes from the South Korean government, these Figures reveal researchers' collaborative strategy and their structural location in the field that play a decisive role in the expert's career. As illustrated in , Hwang's position is relatively marginal (or peripheral) to his ally Moon, who is positioned at the center of the network. At the time, Moon was the chief director of the Cell Application Project Team under the governmental 21st Century Frontier Entrepreneurial Scheme, so Hwang could secure his position only through the strategic ties made with him and Sung-Il Roh, the director of MizMedi hospital, who provided experimental staff and resources.

Figure 1. Stem cell network in 2004 (graphic produced and analyzed by Pajek). FootnoteNotes.

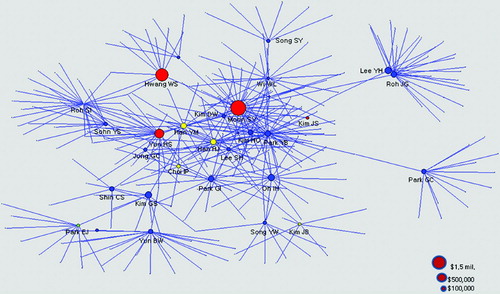

The situation noticeably changed in 2005, after Hwang acquired international fame by publishing his 2004 article in the journal Science. Hwang started to receive unprecedented amounts of research funding (see ). It also meant, however, that he had to legitimate his newly acquired status with new and better results. In the meantime, there was a growing tension between Hwang and Moon that led to them parting ways in 2004. According to Mr Park, the former chief of the National Board of Audit and Inspection that investigated Hwang prior to the prosecutor, it turns out that Moon's team made very little, if any, contribution to the research, though Moon listed himself as a corresponding author in the 2004 Science article. On the other hand, medical doctors in Moon's laboratory later complained to the auditing team that they were frustrated by Hwang's “greed,” which would have led him to encroach upon their area of research: the derivation of stem cells. Hwang himself had to suffer the doctors' pejorative attitudes against him as a veterinary scientist and their uncooperative behavior during the research process (interview with the chief investigator, 28 May 2009).

The impending pressure for another breakthrough, especially after the cessation of cooperation from Moon's team, seems to have seriously affected Hwang's overall position in 2005. As clearly represented in , Hwang's team had few external collaborators, and was isolated from the principal network led by the administrative figure Moon and the medical doctors. In order to overcome his precarious situation among his academic peers and to justify support from the government, Hwang used his personal capacity and position to make his junior researchers work even harder.

Hwang's success in cloning a dog, which resulted in the puppy Snuppy, and his failure in human embryonic stem cell research, represent both the potential and the limitations of the labor-intensive strategy he adopted under constrained circumstances, that is, intensely competitive circumstances in which micro-strategies and resources as well as scientific achievements can play a key role. It appears that there have been two typical ways of acquiring competence in the new cloning technology over the last decade. One way was to improve the fundamental knowledge and techniques as Wilmut's team did in introducing the reprogramming method. The other was to mobilize a maximum number of human and material resources to produce greater outcomes, i.e. Hwang's hit or miss strategy. In a sense, his strategic choice was not only inevitable – because of the limited scientific foundations in South Korea – but it was also workable thanks to Korean researchers' highly disciplined work ethic and technical skills.

This competitive atmosphere contributed to the results-driven mobilization of labor and the cloning of Snuppy the dog that resulted from highly repetitive and arduous experimentation to imitate the actual process of conception, but was deprived of scientific inspiration and academic passion from the researchers. While admitting that Professor Hwang had the warm-hearted and admirable characteristics of a father, one of his postgraduate students still described his five years of laboratory life as: “the coldest days in my life; I was never more admonished or learnt more than in this period, in which I experienced the most gloom in my life” (G. Kim Citation2007, p. 135). A testimony from an interviewed graduate student in the College of Agriculture and Biosciences of SNU confirms that a similar research environment to that of Hwang's laboratory is widespread in ordinary academic life in South Korea:

After the Hwang scandal, some changes were made in my department. For example, people now realize that they should keep experimental notes more accurately and would not embezzle research funds that easily. In terms of basic relationship between professor and masters students, it's still like something between master and slave in a feudal kingdom. Professors set the targeted result of experiments, and younger assistant professors alternately come over to the lab on Sundays to see if we are all there. On the next Monday, he would come over to our class and say something bad about the students who failed to turn up. That is deeply humiliating … [sigh]. When I was in the MA course, I could not expect it to be anything like science. You already have the result you should produce under the professor's command, and you just go for it with repetitive works. The smartest students would outperform the targets set that would be used as the professor's own work. They usually leave for colleges in the United States for PhDs, and would never come back [to Korea]. (Interview with former master's student in SNU, on condition of anonymity, 30 August 2009)

It should be noted that patriarchal leadership exercising authoritarian discipline (G. Kim Citation2007, L. Kim Citation2008), offset by carefully rationed paternalistic care, is not unique to scientific research in South Korea. Rather, it is a typical form of “governmentality” (Foucault Citation1997) pervasive in society, which functions as an effective way to impose discipline, carry out exhaustive operations, and reduce internal tension with a symbolic attitude of paternalism that is “cheaper” than a system of formal reward and payment. Making potentially problematic conduct controllable, by force at first, and reconstructing the conduct as a sign of success, either through implicit recognition or through more concrete compensation, as Hwang and other academics did, appears to encourage the research actor's opportunistic behavior that is difficult to expose and check by formal institutional measures alone, as the following two cases demonstrate.

After the scandal: two cases

It is obvious that many problems were caused by local cultural practices and internal competition in Hwang's case. The traditional problem of lack of expert autonomy vis-à-vis institutional and bureaucratic influence (Bourdieu Citation2004) is also observed in the Korean scientific community more generally. As demonstrated in the following two cases, however, “local cultural practices,” “internal competition” and the problem of “scientific autonomy” are becoming more deeply intertwined in today's mode of knowledge production. As the nature of what are “right” practices and “correct” knowledge are blurry and highly debatable in the life sciences, there is an incessant urge to make the most from the ambiguity. As Bernd Pulverer, chief editor of Nature Cell Biology, states, “99 per cent of articles submitted to scientific journals are somehow involved with beautification'” (Pulverer Citation2008). As the new entrepreneurial attitude among academics – one that is single-mindedly geared towards prevailing over competition – is adapted to and legitimized by the operation of the modern knowledge economy, it is extremely difficult for individuals to resist competitive pressures and the will to cheat for the sake of greater transparency. Compared to the “less modern” political dictatorship that had a visible, single center of power to resist against in South Korea decades ago, the implicit pressure of “economic considerations” is less visible but more pervasive in the country today. This new environment rewards submissiveness and punishes resistance to the prevailing, market-driven rationality in an invisible but more a sophisticated way.

Case 1

Jin-Yong (an alias) was a postdoctoral life scientist at the Korea Advanced Institute for Science and Technology (KAIST). He led major experiments in the neurochemistry department alongside his senior professor, and published first-authored articles in Nature and Science. By 2006, he was listed as one of the “100 most prospective young scientists” in the country. Then he accepted a fellowship in a high-ranked university in California. His successful career abruptly came to an end when a part of the experimental results he published in Science was questioned by the auditory body of the university. It was eventually exposed as a fabrication. It turned out that, although Jin-Yong had already brought about admirable achievements through the experiments, his professor had coerced him to exaggerate unproven results to augment the reputation of his venture business. Jin-Yong initially did not comply. But, faced with an outburst of furious admonishments, like those of a “mad man” according to his testimony, he finally gave in. Jin-Yong wrote in his statement:

After the press interview announcing the experimental results [including the fabricated part], the professor told me, “Your problem is that your face reveals everything when you're lying [in the public announcement]. Look at Hwang. He was so confident and sincere that at the brink of time [when] he was telling big lies, the public trusted him to the end! That is the capacity we need at this moment to win over the competition.”Footnote1

Case 2

On 16 April 2009, the Parliamentary Life Science Research Forum organized a workshop in the parliament building to explore ways of promoting human embryonic stem cell research more actively in the future. This undoubtedly provided encouragement to many stem cell scientists in South Korea after the humiliating disgrace caused by the Hwang scandal. The underlying motives for this promotion were especially spurred by US President Obama's brisk move to lift former President Bush's strict limits on embryonic stem cell research. South Korean policy on embryonic stem cell research, which had become strict, had to be reconsidered.

Dong-Wook Kim, chief of the National Stem Cell Research Center after Shin-Yong Moon's resignation, deplored the fact that Korea's position had been weakened over the previous few years by the “cynical atmosphere” following the Hwang scandal, and the subsequent withdrawal of government funding for stem cell research. Kim diagnosed that Korean scientists suffered from a “loss of war morale and ammunition.” Another keynote speaker, Hyung-Min Chung, claimed that now it was time to move away from an “unproductive” debate on bioethics, and seek ways to respond to the rapidly changing international research situation. Clearly, there was a shared notion among speakers to regard the change in US policy as the “global” trend; there was also an atmosphere of shared irritation regarding ethical regulation in Europe. Eventually, Jung-Chan Rah, Director of venture cloning firm RNL Bio, asked: “Why does the EU raise bioethical issues while America is silent?”Footnote2

Discussion: the global knowledge economy and science

The South Korean experience in stem cell research reveals the difficulties encountered in developing countries trying to simultaneously pursue the competitive application of scientific knowledge and the democratic governance of scientific practice. Sustainable governance of scientific research, including ethical regulation, presupposes a degree of regulative competence that is able to withstand the pressure of short-term interests, and a high level of basic scientific knowledge. Both elements also require sufficient economic and human resources to enable the implementation of long-term strategies. In that sense, it is conjectural that some leading South Korean stem cell scientists continue to rely on government funding, hard work, and a high number of biological resources, such as ova, for their ongoing research. In fact, a research culture that prioritizes an applied approach to science is the common reality for most East Asian countries. But the emerging local problems in the global knowledge economy can no longer be explained by national context alone.

Global norms for scientific conduct have yet to emerge. As observed in the UK, the effective alliance between policymakers who devise a permissive ethical regulative framework and the experts who are endowed with globally competitive knowledge can produce powerful global discourses for the governance of research. The regulative frameworks, such as the criterion of a 14-day limit on embryo research proposed by the Warnock Committee (see Jasanoff Citation2005), the endorsement of the “hybrid bill,” and recent changes in egg donation policy in the UK clearly reveal that they are the institutional outcomes of the aims of policymakers, scientists, scientific knowledge, and strategies to legitimate a particular research process for national and social interests. In a similar vein, discussions on the ethical regulation of stem cell research are not independent of current modes of governance. Debates on ethical regulation can also contribute to competition through “defining power” (Beck Citation2009) and setting “global standards” that serve the political–economic interests of particular states. From a genealogical perspective, it is the nature of “neo-liberal governance” (Foucault Citation2008) to justify itself through the mobilization of discourses in pursuit of economic self-interest. Regarding the governance of stem cell research, we come to observe the same mechanism of legitimation. For the actors in the scientific field to reach a consensus on ethical regulations on a global level, it is important to realize that ethical governance should reflect the embedded “economic way of thinking and conduct” in human behavior as well as develop a common notion of bioethics. In this regard, deliberate efforts to provide economic incentives and social recognition to non-commercially oriented researchers can be as important as clarifying the boundaries of good research practice.

In this context, the definition of ethical requires a semantic extension that goes beyond checking for the fabrication of experiments or the institutionalization of bioethical procedures such as “informed consent” or the establishment of an institutional review board. These conventional ways of institutionalization do not problematize the global environment in which the majority of researchers are confronted with mounting pressures for survival, which may encourage scientific malpractice. The internalization of the logic of competition and the “asymmetrical convergence” of scientific practices between academia and industry are not just experienced as problematic for researchers in developing countries. Novel ways of creating a global “breathing space” that especially support junior researchers' individual autonomy, good research practices and international collaborations in science need to be discussed at a transnational level, and used to establish ethical commitments. As observed by Eriksson and Webster Citation(2008), in their study of international cooperation in stem cell science, scientific communities can make concerted institutional efforts to invigorate basic scientific research on a transnational level. The international collaboration based on consensual ethical principles could also contribute to protecting the integrity of individual researchers and their rights as autonomous experts if the effort is effectively extended to the wider domains of scientific practice. Unless ethical considerations in science are extended to the core of the “conduct of conduct” to address the characteristics of the globalizing knowledge economy, the existing framework of regulation may at best externalize the modes of exploitation from wealthy countries to relatively peripheral, unwatched, countries. It is therefore important to find common pathways to reduce overall malpractice, which can be coupled with the current mode of global economic rationality practiced by the subject, rather than to simply blame local “cultures” for “underdeveloped” ethical governance.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to Margaret Sleeboom-Faulkner who provided remarkable support and demonstrated impressive leadership to make this research possible. I am also grateful to an anonymous reviewer and the Editor who showed strong trust in and support for my paper, despite a number of apparent flaws in my previous draft.

Notes

Notes: Red: Hwang and ally; blue: medical doctor; yellow: biology; green: bioethics (color online).

Jin-Yong's official statement presented to UCLA after the misconduct investigation.

Quotes are translated by the author. Source: International Institute for Asian Studies newletter

References

- Anon., 2006. The prosecutor's report of the investigation of the Hwang case. Seoul: The Prosecutor's Office..

- Beck, U., 2009. World at risk. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2009.

- Bourdieu, P., 2004. Science of science and reflexivity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2004.

- de Nooy, W., Mrvar, A., and Batagelj, V., 2005. Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

- Dreyfus, H., and Rabinow, P., 1982. Foucault: beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1982.

- Eriksson, L., and Webster, A., 2008. Standardizing the unknown: practicable pluripotency as doable futures, Science as Culture 17 (1) (2008), pp. 57–69.

- Foucault, M., 1997. Il faut défendre la société. Cours au Collège de France 1976. Paris: Gallimard/Seuil; 1997.

- Foucault, M., 2008. The birth of biopolitics. London: Macmillan; 2008.

- Gottweis, H., and Kim, B., 2009. Bionationalism, stem cells, BSE, and Web 2.0 in South Korea: toward the reconfiguration of biopolitics, New Genetics and Society 28 (3) (2009), pp. 223–239.

- Gottweiss, H., and Triendle, R., 2006. Koreanische Träume, Die Zeit (2006), 5 January.

- Hwang, W-S. et al., 2004. Evidence of a pluripotent human embryonic stem cell line derived from a cloned blastocyst. Science, 303(5664): 1669–1674.

- Jasanoff, S., 2005. Designs on nature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2005.

- Kim, G., 2007. Hwang myth and South Korean science [in Korean]. Seoul: Yukbi; 2007.

- Kim, H., 2006. The present and future of South Korean society in view of the Hwang scandal [in Korean]. Presented at Paper presented at the Biotechnology Monitoring Conference.

- Kim, J., 2009. Public feeling for science: The Hwang affair and Hwang supporters. Public Understanding of Science 18 (6): 670–686..

- Kim, L., 2008. Explaining the Hwang scandal: national scientific culture and its global relevance, Science as Culture 17 (4) (2008), pp. 397–415.

- Kim, L., 2009. Beyond Hwang “international stem cell war” in South Korea, International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter 52 (2009), p. 25.

- Kleinman, D., and Vallas, S., 2006. "Contradiction in convergence: universities and industry in the biotechnology field". In: Frickel, S., and Moore, K., eds. The new political sociology of science. Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press; 2006. pp. 35–62.

- Park, E., 2004. Park, E., ed. Stem cell research ethic and legal policy [in Korean]. Seoul: Ewha University Press; 2004.

- Pulverer, B., 2008. Research misconduct: plagiarism, fraud and the integrity of science. Presented at Paper presented at the Wellcome Trust Workshop on Mechanisms of Fraud in Biomedical Research. 17–18, October, London.

- Shin, J., 2009. Eight Q&As in the biotech era. Business report [in Korean]. Seoul: Mirae Asset; 2009.

- Sleator, A., 2000. Stem cell research and regulations under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. 2000, Rev. ed. House of Commons Library Research Paper 00/93.