Abstract

Emerging evidence opens new possibilities to improve current breast cancer mammography screening programs. One promising avenue is to tailor mammography screening according to individual risk. However, some factors could challenge the implementation of such approach, specifically its potential impact on the equitable delivery of services. This study aims to identify the barriers and facilitators to the equitable delivery of services within a future integration of a personalized approach in the Québec screening program. We then propose different means to address them. We conducted 16 semi-structured interviews with stakeholders with a role in the management, implementation or assessment of the Québec screening program. The barriers and facilitators identified by respondents were regrouped in two themes: 1) Reproduction of social inequities, and 2) Amplification of regional disparities in access to services. We consider that fostering inclusion through communication strategies and relying on electronic communication technologies could help in addressing these issues.

1. Introduction

Currently, Canadian breast cancer screening programs provide biennial mammography to asymptomatic women between the ages of 50 and 69, regardless of individual risk factors (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Citation2011). Similar programs to detect cancer at an early stage exist around the world. However, there remains an ongoing debate about whether the benefits of these programs outweigh their possible disadvantages (such as overdiagnosis, false-positive results, unnecessary follow-up biopsies and anxiety) (Myers et al. Citation2015; Houssami Citation2017). Emerging evidence in personalized medicine opens new possibilities to improve these screening programs. One possibility that might be soon implemented is the assessment of personalized risk in order to target women most likely to benefit from mammography screening (Shieh et al. Citation2017; UK Government, Department of Health Citation2017). In this way, women who are at higher risk of developing breast cancer could be advised to start mammography screening at a younger age and/or have more frequent mammograms. This could improve patient outcomes, detection of earlier-stage cancer, and allocation of health care resources (Hall and Easton Citation2013; Onega et al. Citation2014).

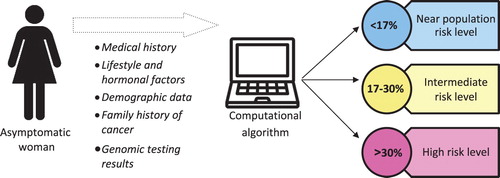

Recent discoveries have demonstrated that it is now possible to identify hundreds of genomic markers that slightly or moderately increase the risk of developing breast cancer (Mavaddat et al. Citation2015; Chatterjee, Shi, and Garcia-Closas Citation2016; Michailidou et al. Citation2017; Milne et al. Citation2017). These genomic factors may be combined with non-genomic risk factors (such as age, mammographic density, family history of cancer) in a computational algorithm, providing a useful assessment of individual risk (). Calculated individual risk would then allow recommended screening measures to be tailored to the appropriate level of risk (Gagnon et al. Citation2016; Rainey et al. Citation2018). This personalized risk-based approach would improve current mammography screening programs that primarily use age as the inclusion criterion (Hall and Easton Citation2013). Although this emerging approach has not yet been implemented by health authorities anywhere in the world, many ongoing research projects involving thousands of women could well favor its future adoption (e.g. BRIDGES [Breast Cancer Risk after Diagnostic Gene Sequencing]; FORECEE [Female Cancer Prediction Using Cervical Omics to Individualize Screening and Prevention]; MyPeBS European Commission Citation2017; PERSPECTIVE I&I [Personalized risk assessment for prevention and early detection of breast cancer: Integration and Implementation]; WISDOM).

Figure 1. Breast cancer individual risk assessment process: An example. The percentages used here are approximate; they were used to facilitate discussions between experts during the development of the PERSPECTIVE recommendations as explained in Gagnon, J.; Lévesque, E.; the Clinical Advisory Committee on Breast Cancer Screening and Prevention; et al. Recommendations on breast cancer screening and prevention in the context of implementing risk stratification: impending changes to current policies. Current Oncology 2016, 23, e615-e625, doi:10.3747/co.23.2961.

Because risk-based screening using genomic factors is a radical new approach with regard to screening programs, various organizational issues need to be considered prior to implementation (Dent et al. Citation2013). Equity in the delivery of services is one of the organizational issues that could challenge the implementation of this approach in current screening programs (Anderson and Hoskins Citation2012; Hall et al. Citation2014; McGowan et al. Citation2014; UK Government, Department of Health Citation2017). Equity is a fundamental value of the Canadian health system, and means that “citizens get the care they need, without consideration of their social status or other personal characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity or place of residence” (Romanow Citation2002). In the literature, equity in the delivery of services is also articulated in terms of the concept of “distributive justice,” referring to situations in which individuals or groups unfairly benefit from health services due to their socio-economic status, educational background or ethnicity (Hall et al. Citation2014).

Although some potential equity issues have already been identified in the literature (Anderson and Hoskins Citation2012; McClellan et al. Citation2013; Hall et al. Citation2014; McGowan et al. Citation2014; UK Government, Department of Health Citation2017), they may not be automatically transposable to the approach under study. The specificities that might prevent transposition of prior results include: the type of genomic markers used (e.g. when mutations on the high risk genes like BRCA1/2 are not targeted), the Canadian insurance context (e.g. where health services are public and tax-funded), and the public health-oriented approach (when services are population-based). Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize the factors likely to challenge the equitable delivery of services with the integration of this personalized risk-based approach in the Canadian context (Hall et al. Citation2014), and then identify the solutions that could be envisioned to manage them. In addition, it is recognized that exploring health professionals’ perceptions related to personalized screening might facilitate implementation (Rainey et al. Citation2018). To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine equity in the delivery of services for the risk-based approach through stakeholder perceptions.

2. Context and methods

As part of the Personalized Risk Stratification for Prevention and Early Detection of Breast Cancer (PERSPECTIVE) research project (Genome Québec), which is developing tools to implement a risk-based approach (e.g. calculation algorithm, genomic test, economic simulation model, screening policies), we had to consider the various parameters of tools developed through this project. This presupposes an individual risk assessment step to complement Canadian breast cancer screening programs. It is conducted with an algorithm (next version of BOADICEA (Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm)) which computes both genomic test results (only variants increasing lowly or moderately the risk) and extended personal risk factors (e.g. mammography density, alcohol intake, body mass index).

Each Canadian province has its own public screening program, but provincial programs share common bases and a similar health services delivery context. Our study focuses on one of them: the program in the province of Québec. Since 1998, this screening program has provided one mammogram every 2 years to all women between 50 and 69 years of age. It is managed by the Ministry of Health, implemented by hospitals and clinics and assessed by various governmental bodies.

Our global aim was to study the barriers and facilitators of the implementation of the personalized risk-based approach, by focusing on: 1) the influence of organizational factors, 2) the use of information by insurers, and 3) the equitable delivery of services. As analysis of parts of our interviews pertaining to the first and second aspects were presented in previous publications (Hagan, Lévesque, and Knoppers Citation2016; Dalpé et al. Citation2017), this paper focused on the results of the third remaining aspect.

Since our aim focuses on organizational aspects of implementation, we designed our data collection and analysis within an institutional framework, which offers a relevant sociological perspective to study processes of organizational change in healthcare (Pedersen and Dobbin Citation2006; Currie et al. Citation2012; Zilber Citation2012). We planned semi-structured interviews (open-ended questions) with stakeholders having a good level of knowledge of the delivery of services in the Québec breast cancer screening program and assuming some responsibility in this program at the organizational level (i.e. management, implementation or assessment).

The general themes selected for the interview guide (see ) reflect the main dimensions of the institutional framework, while the sub-themes were identified by analyzing the documents published on the current Québec breast cancer screening program (framework, reports, action plan and evaluations) and via analysis of the international literature on barriers and facilitators to the implementation of genetic technology and personalized medicine (using PubMed). Approval was obtained from the ethics committees of McGill University and the Québec University Health Center (CHU de Québec-Université Laval).

Table 1. Development of our interview guide on the barriers and facilitators of the implementation of the risk stratification approach (focusing on the influence of the organizational factors, the use of information by insurers, and the equity in the delivery of services).

In total, we completed 16 individual interviews (12 in person and 4 by phone), lasting each on average 50 min, between March and June of 2014. Interviewees were identified through our network of collaborators as well as via public documents available on the Internet, in addition to snowball sampling. Potential participants were approached directly or via email. Almost all the interviewees had a clinical background (14/16) and they were selected to ensure variation in the following criteria: region, gender, type of involvement in the program, affiliation and prior knowledge of the risk-based approach (Mason Citation2010) (see ). Recruitment continued until data saturation (i.e. until all viewpoints were represented without repetition) (Lai-Goldman and Faruki Citation2013). Interviews were conducted in French (excerpts presented in this paper were translated). However, 3 interviewees did not answer questions related to the equitable delivery of services because this topic was outside the scope of their expertise or due to lack of time. These 3 interviews are not included in the analysis presented in this paper.

Table 2. Profile of the 13 stakeholders who answered questions on equity in the delivery of services. Stakeholders who had previously taken part in an expert consensus meeting on the personalized risk-based approach (to achieve another aim of our PERSPECTIVE project) were considered to have prior knowledge of the approach.

At the beginning of each interview, participants were provided with standard information on the risk-based approach (also called “risk stratification,” see ) in order to ensure a common basic understanding of this new approach, and avoid confusion with the traditional approach used with women having a family history of cancer (i.e. through identification of high-risk mutations in the BRCA1/2 genes after genetic counseling). Stakeholders were informed that, with the risk-based approach, each woman would be provided with a statistical estimate of the risk of developing the disease until the end of life expectancy (80 years), thereby situating each woman within a risk level.

Table 3. Factual background provided to the stakeholders at the beginning of each interview.

The interviews were recorded (except for one who preferred handwritten notes) with the participants’ written consent and then transcribed. Interview transcriptions and handwritten notes were coded thematically (by J.H.) to address the issues identified in the literature (Currie et al. Citation2012) and new codes were assigned to the interview sections addressing empirical issues that we were not able to address using the initial literature-driven themes (Srivastava and Hopwood Citation2009). Transcriptions and thematic categories were discussed with a second researcher (E.L.) throughout the analysis process. Data relevant to equity were placed in the two broader thematic categories that emerged from our analysis.

3. Findings

Almost all answers provided by the interviewees were in relation or in comparison to the Québec screening program currently in place. As such, to support understanding, the presentation of our findings will be preceded in each sub-section below by background information on the Québec healthcare context. Due to the empirical experience of the interviewees, the facilitators identified were mostly formulated as solutions or proposals to address an existing or anticipated issue. The barriers and facilitators identified by respondents were grouped in two themes: (3.1) Reproduction of social inequities, and (3.2) Amplification of regional disparities in access to services.

3.1. Reproduction of social inequities

The stakeholders interviewed raised concerns about reproduction of social inequities across 3 stages: a) Solicitation of women b) Informed consent, and c) Return of results.

3.1.1. Solicitation of women

Under the Québec screening program, an invitation letter and a one-page information pamphlet (Québec Government, Ministry of Health and Social Services) is sent every two years to the home address of each woman between the ages of 50 and 69. The pamphlet encourages women to obtain a mammogram in one of the designated screening centers. Having an assigned primary care provider does not affect eligibility, though some women could be encouraged and/or reminded to participate by their assigned primary care provider. The methods that would be used to invite women to have a risk assessment in a personalized risk-based approach have yet to be determined. For instance, who will invite the women, when will women be invited and how they will be contacted, are still unknown.

Almost all respondents (12/13) raised concerns about the impact that the chosen method of invitation could have on equity of participation. They underlined current challenges to the inclusion of certain disadvantaged sub-groups of women in regard to language, ethnicity, literacy level and/or education. Some interviewees mentioned that this difficulty could be exacerbated by the complexity of the risk-based approach (e.g. several steps before mammography, probabilistic risk estimation process) and the contribution of a genomic component.

According to some respondents, in-person solicitation by the assigned primary care provider could be an adequate alternative to the traditional postal invitation to address these potential inequities. However, most of the interviewees (8/13) pointed out the fact that many women in Québec do not have an assigned primary care provider who oversees their preventive care. In this context, some stakeholders considered that relying only on the assigned primary care providers to solicit women could also replicate/reinforce difficulties in access to health services that these women currently experience. One respondent underscored the fact that, no matter how efficient the solicitation tools are, the recommendations of primary care providers will likely remain decisive:

Because health professionals have credibility among the population, more than any tools we can build. We can use the best tools to convince someone to participate, but when the doctor says “That’s not worth doing,” we lost everything we just obtained.

To address the issue of equity during the solicitation of women, some interviewees suggested using competing solicitation approaches (e.g. postal letter associated with solicitation from primary care providers and community health leaders), adapting communication tools to the particular concerns of sub-groups (e.g. cultural groups less comfortable with image of breasts) and involving women in the development of these tools (e.g. focus groups including women of different ethnicities). One interviewee pointed out a successful strategy developed to inform women in Indigenous communities:

We made a kind of collaboration with them to find the best strategy […] In the end, it was very simple. This was the portrait of the female chief, on a poster, who encouraged women to learn about the program.

3.1.2. Informed consent

Currently, written consent (Québec Government, Ministry of Health and Social Services) to participate in the Québec screening program is obtained without doctor involvement at the mammography clinic (Québec Government, Ministry of Health and Social Services). The informed consent process that would be adopted in a risk-based approach might take several forms, specifically with regard to the involvement of healthcare professionals and to the informational tools that would be used (e.g. website, poster, letter, pamphlet, video). It is still undetermined which professionals will be involved, as well as when and how they will obtain informed consent.

Several interviewees mentioned that the risk-based approach could add complexity to the informed consent process. But, only few of them expressed the opinion that this complexity could foster social inequality and challenge the informed nature of the consent. A stakeholder pointed out that this additional complexity could:

[…] significantly increase health inequalities by favoring university graduates (…) and by clearly disadvantaging those who have not finished high school.

Even when you try to obtain the most informed consent possible from women, it’s the doctor’s responsibility to explain things to the patient. Not to decide for them, but to recommend the right course of action […].

In addition, some interviewees mentioned the importance of considering the cultural specificities of different sub-groups (e.g. those not understanding the language of the majority; having a cultural taboo about breasts; showing reluctance to undergo screening without involvement of their husband; lacking trust in health authorities) and hence the need to adapt communication tools. For instance, one interviewee raised concerns about immigrant women:

With an immigrant population, I do not know how the message can really reach them when French is their third or fourth language. We must be very careful not to increase social inequalities in health.

Yet, many of them also emphasized the fact that the current Québec screening program information document was already adapted to local particularities in its many versions in order to decrease the impact of cultural particularities on participation in the program.

3.1.3. Return of results

Within the current Québec screening program, mammography results requiring follow-up are discussed between the women and her assigned primary care provider (or a primary care provider associated with the program if she does not have her own). They both receive the mammography results. Unlike the current program, a personalized risk-based approach would generate three types of results before starting the mammography screening: the estimated risk, the risk level and the risk-based screening recommendations. Communication of these results will need to be organized in order to support decision-making about the risk-adapted screening recommendations. Some of the unknowns are who will return the results, when and how this will be done, and also to whom the results will be communicated.

Many stakeholders (8/13) expressed concerns about the possibility of making results understandable for women due to their inherent complexity or an insufficient level of health literacy. One stakeholder explained why there should be additional resources to facilitate efficient communication:

There is a high proportion of the population who don’t have a sufficient level of literacy to understand these health concepts. Numeracy level, understanding numbers, is even worse because you talk about risk.

To mitigate inequity at the step of the return of results, stakeholders proposed to: use adequate communication tools (e.g. simple, efficient, with a visual design, easy to use by healthcare professionals who have little time to communicate information); rely on the experience of risk communication acquired from other health conditions in preventive medicine (e.g. cardiovascular diseases, colorectal cancer); and offer access to women and/or health professionals to a specialized resource (e.g. genetic counselors).

3.2. Amplification of regional disparities in access to services

In Québec, some remote areas are poorly equipped with health facilities and have scarce access to primary care providers or specialized doctors. The current screening program, with its decentralized implementation strategy, aims to provide equivalent health service delivery irrespective of geographical location. For example, mobile mammography services (i.e. portable mammography machines that are transported by plane, boat or train) currently provide screening to some remote communities that are hard to reach by land, for instance to Indigenous communities in Northern Québec (Cree Board Council of Health and Social Services of the James Bay). In addition, women who do not have an assigned primary care provider to follow-up with the mammography results are provided with an ad hoc primary care provider. How health services would be geographically available in a risk-based approach remains to be determined. For instance, it has yet to be decided which services will be available, and where and how women will have access.

Regional disparity in access to services in a personalized risk-based approach was identified as a key issue by most of the interviewees (9/13). They were concerned that “some regions would be advantaged compared to others.” Their concerns included the services required to calculate risk (e.g. sampling, genomic testing), but also the follow-up measures recommended for each risk level (e.g. imaging exams, consultation with a specialized doctor, genetic counseling). Many expressed the view that women living in rural or remote areas should have access to the same services offered to women in urban centers. For instance, equitable access to specialized imaging technology was mentioned:

What speaks to me is really to ensure that equitable access is offered. If a program is implemented, is offered to everyone, some regions don’t have magnetic resonance imaging.

In addition, access to services raised concerns among interviewees in respect of the services that would be required in a personalized risk-based approach for women experiencing anxiety, stress or other concerns. Almost all respondents (10/13) underlined the management of anxiety as an expected issue in any personalized risk-based approach. The potential lack of financial resources and of adequately trained health professionals and genetic counselors were the main challenges mentioned by the respondents in regard to psycho-social service delivery.

Many stakeholders (6/13) identified the measures and inventiveness of the current Québec’s screening program as a way to mitigate inter-regional inequities. One interviewee suggested setting up a specialized national telephone resource as a solution to the scarcity or uneven geographic distribution of genetic counselors and geneticists.

4. Discussion

Our findings revealed that interviewees involved in the management, implementation or assessment of the Québec breast cancer screening program expect that equitable delivery of services would be challenged by the addition of a risk-based component. Their concerns were chiefly concentrated on two issues: the reproduction of social inequities, and the amplification of regional disparities in access to services.

These findings are consistent with the concerns expressed by many authors in the literature on the implementation of personalized medicine in breast cancer and of genomic testing. In 2013, Burton et al. clearly summarized the issue of equitable access in the context of the future implementation of a risk-based screening approach:

With respect to distributive justice, it will be important to ensure that different societal groups have equal access to the program and that it is delivered in a fair and objective fashion so that, as far as possible, different societal groups have an equal chance of benefit (Burton et al. Citation2013).

More specifically, the literature has reported that: risk perception is affected by health literacy, health numeracy, and cultural beliefs (Anderson and Hoskins Citation2012); limited health literacy poses a particular challenge to communicating with underserved communities about genomics (Lea et al. Citation2011); people with lower health literacy may not be able to take advantage of precision medicine in the same ways as those with higher health literacy (Ferryman and Mikaela Citation2018); risk is a difficult concept that is not well understood by the public (Lea et al. Citation2011); and even a well-educated population might not fully understand the terminology associated with genetic testing (Hooker et al. Citation2014).

On the issue of regional disparities in access to services, the literature also reveals concerns in regard to the provision of genetics services in rural areas. Guttmacher et al. expressed this concern 17 years ago—long before the implementation of genomics in population-based programs was envisioned—in regard to the widespread integration of genomics in medicine generally:

Undoubtedly, many factors contribute to lack of equity in access to genetic services. Geographic barriers to access have been one such factor. With only a few thousand genetic specialists nationally, many cities have no genetic specialists and some states have only a few (Guttmacher, Jenkins, and Uhlmann Citation2001).

In order to manage the issue of equity for the future implementation of a risk-based approach, we looked into solutions proposed by the interviewees and in the literature. We identified, through discussions among authors, who are closely involved in the PERSPECTIVE project (J.S. is lead investigator and B.M.K. is co-lead investigator), what might be the most promising solutions. The two solutions relevant for the Québec context were considered to be: 4.1) fostering inclusion through communication strategies and 4.2) relying on electronic communication technologies.

4.1. Fostering inclusion through communication strategies

Interviewees underlined the complexity of communicating genomic information, pointing out that difficulties in making key concepts of this approach understandable could negatively impact the participation of women with low health literacy or who come from less privileged socio-economic groups. In the province of Québec, significant socio-demographic variances occur from one region to another, and so do literacy and numeracy rates. In general, Québec rural areas present a lower level of health literacy than metropolitan and/or urban areas. (Institut de la statistique du Québec) Cultural barriers may also affect communication about health issues, for instance with immigrants (Paternotte et al. Citation2015) or Indigenous communities (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health). Having a public healthcare system irrespective of the ability to pay doesn’t guarantee equity in its access to marginalized populations, such as homeless people (Hwang et al. Citation2010) or people from Indigenous communities (Tang and Browne Citation2008). In addition, interviewees expressed concerns about the impact of solicitation that would rely essentially on assigned primary care providers (in 2014, 28% of women in Québec lacked a primary care provider) (Institut de la statistique du Québec).

Due to its complexity, the personalized risk-based approach will likely require “more interactions between the service and the recipient” (Dent et al. Citation2013) than current age-based programs. While more interactions will occur, the efficiency of communication with women could have greater impact on participation. The adaptation of solicitation tools that address the particular needs of sub-groups, as well as the participation of women in developing these tools, have been offered as a solution by some respondents. They also mentioned that the current Québec screening program already uses a similar process in some regions. As reported in the literature, information “should be culturally sensitive, and culturally appropriate support should be provided for different groups of service users to ensure maximum coverage and inclusivity” (Hall et al. Citation2014). To address lower uptake among some ethnic or socioeconomic sub-groups, “active communication strategies […] will be needed to mitigate any exacerbation of existing inequalities” (Chowdhury et al. Citation2013).

We consider that fostering the inclusion of disadvantaged groups through communication strategies might support equitable delivery of services. This could consist of developing appropriate communication measures to support participation of those affected by inequities, including those with a minority language or culture, limited knowledge of the health system, low level of health literacy and numeracy, and reduced mobility. These measures could also ensure equitable solicitation of women that don’t have an assigned primary care provider, for instance by using a variety of methods of invitation. Finally, as the impact of ineffective communication can occur at different stages (solicitation, consent, and return of results), equitable communication strategies would need to cover all these steps.

However, some organizational barriers may impede the implementation of inclusion strategies. First, an increase in costs could be reasonably expected if methods to communicate were multiplied (e.g. in terms of language, format, place, and staff involved) or if they would involve more personalized interactions with healthcare workers. In addition, if adapted communication strategies relied on non-conventional healthcare channels of communication to reach the disadvantaged groups (e.g. community organizations, churches (Karcher et al. Citation2014)), it could be challenging to build collaboration and align procedures with organizations outside of the healthcare system (Maxwell et al. Citation2014).

4.2. Relying on electronic communication technologies

During the interviews, concerns were expressed about whether regional equitable access to health services (i.e. specialized expertise and psychosocial support) would be provided. In Québec, regional access might be challenged by the size of the territory and its highly variable population density, the unequal geographical distribution of healthcare services and resources, and difficulties in accessing certain types of healthcare professionals in some regions (e.g. primary care providers, genetic counselors). For example, many Indigenous communities don’t have year-round road access or a local hospital, and patients must leave their community to access more specialized care (National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health). In addition, there are a small number of genetic counselors and geneticists, and their practice is concentrated in urban and/or metropolitan areas (Québec association of genetic counselors).

The literature suggests that providing genetic consultations via videoconferencing offers a solution to provide services in a context were specialized resources are scarce and unevenly distributed (Elliott et al. Citation2012; Buchanan et al. Citation2015; Bradbury et al. Citation2016; Mette et al. Citation2016). Research results demonstrate that communication technologies contribute to avoiding unnecessary transportation of people from First Nations communities in remote areas, allowing them to stay with their family (Khan et al. Citation2017). This alternative method of genetic counseling delivery by a videoconference system that incorporates non-verbal cues is also called “telegenetics.” According to the literature, telegenetics increases patients’ knowledge and decreases depression and anxiety (Hilgart et al. Citation2012). Some results suggest that telegenetics is acceptable and convenient in the context of genetic counseling for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer (Zilliacus et al. Citation2010; Zilliacus et al. Citation2011; Pruthi et al. Citation2013). In contexts where genetic counseling resources are lacking, the potential of telegenetics should be considered. This technology could also be used to provide specialized expertise to health professionals themselves in order to address the lack of expertise of primary care providers and difficulties accessing this expertise.

Information technology can also be used to provide both clinical and psychosocial support to women. One interviewee proposed setting up a national telephone resource offering specialized expertise regardless of location. Specifically, electronic technologies enabling communication over distance between women and persons offering clinical or psychosocial support should be considered, by phone (Davis et al. Citation2015; Casey et al. Citation2017), text messaging (SMS) (Hall, Cole-Lewis, and Bernhardt Citation2015; Rico et al. Citation2017; Uy et al. Citation2017) and videoconference (Mette et al. Citation2016). Studies have demonstrated that communication technologies could be used to provide remote support, while maintaining the quality of the service (Melton et al. Citation2017).

We consider that the use of electronic communication technologies could offer a solution for regional inequitable access to clinical and psychosocial support. Not only could this solution be used to support women and health professionals at the stage of the return of results, but should also be considered at two earlier stages in the process: solicitation of women and informed consent. Several interviewees expressed apprehension in regard to the complexity of the information used to communicate with women at these stages. Electronic information technologies (e.g. video, chat, text messaging) might help address this concern at these stages, regardless of the region of residence of the women.

Nonetheless, implementation of electronic communication technologies in the healthcare system might encounter some organizational barriers. One of the most notable in the province of Québec is the strict, complex framework currently in place to ensure the confidentiality of communication between patients and healthcare providers. This framework includes laws, by-laws, professional codes of conduct, governmental policies, agreements on confidential data exchange, and institutional computer security rules. In addition, barriers related to the technology itself should not be overlooked. Mandatory public tenders in the health system could force the use of some software and/or interface brands that are not preferred by the users (Regulation respecting contracting by public bodies in the field of information technologies). Many remote regions, specifically where Indigenous communities are located, could also face limitations to access video communication technologies due to limited Internet capacity (The Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission).

5. Limitations and conclusion

There are a few limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the size of the Québec screening program made our recruitment challenging. Although our sample appears small, it is adequate for a qualitative study considering the size of the health system (the Québec population is 2,5% of the U.S. population, and 12% of the U.-K. population). Second, half of the stakeholders interviewed had previously taken part in an expert consensus on the risk-based approach to achieve another aim of the PERSPECTIVE project. These interviewees could have been influenced by some general information gathered during the expert consensus, although only medical aspects were discussed (Gagnon et al. Citation2016). On the other hand, the interviewees who participated in the expert consensus could also be better informed in identifying the issues relevant to implementation. Finally, while many respondents relied on their clinical experience to anticipate the potential needs and behaviors of women, our study did not include direct assessment of patient perspectives. Our focus was on the organizational barriers and facilitators, while women’s views are under study by other PERSPECTIVE researchers.

We should mention one emerging aspect of equity in the delivery of service that was not covered in our study: the reduction of mammography screening for women classified in the lowest risk level. Although some authors had raised this sensitive issue in terms of distributive justice (Hall et al. Citation2014) or social acceptability (Meisel et al. Citation2015), we did not include this topic in our interview guide because reducing the services currently offered was not planned in our PERSPECTIVE project. As the evidence available in 2013 did not support recommending decreasing mammography frequency for the lowest risk level, new evidence may well suggest exploring this issue in the future.

Many benefits are expected from risk-based screening, including higher detection rates at an earlier stage and a better allocation of financial resources in the health care system. Indeed, this new approach brings a “novel screening and prevention paradigm [that will] require a more complex framework” (Rainey et al. Citation2018). Health authorities will have to address these issues at the organizational level, including that of equity in the delivery of services. Our analysis allows us to conclude that fostering inclusion through communication strategies and relying on electronic communication technologies could help in addressing equity issues. Although our results came from analysis of the Québec health system context, they can be useful for the implementation of the risk-based approach in other similar health systems. Our findings will inform and advise our new research project, a continuation of the PERSPECTIVE project (Personalized Risk Assessment for Prevention and Early Detection of Breast Cancer: Integration and Implementation (PERSPECTIVE I&I)). Since this new project aims to offer a breast cancer risk assessment to 10,000 Canadian participants and to recommend risk-adapted screening measures, we will propose to foster participant inclusion through various communication technologies and to rely on electronic communication technologies if possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Emmanuelle Lévesque http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4618-6635

Bartha M. Knoppers http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7004-2722

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, E. E., and K. Hoskins. 2012. “Individual Breast Cancer Risk Assessment in Underserved Populations: Integrating Empirical Bioethics and Health Disparities Research.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23, doi:10.1353/hpu.2012.0178.

- BOADICEA (Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm). Accessed April 9, 2018. http://ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/boadicea/.

- Bradbury, Angela, Linda Patrick-Miller, Diana Harris, Evelyn Stevens, Brian Egleston, Kyle Smith, Rebecca Mueller, et al. 2016. “Utilizing Remote Real-Time Videoconferencing to Expand Access to Cancer Genetic Services in Community Practices: A Multicenter Feasibility Study.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18: e23. doi:10.2196/jmir.4564.

- BRIDGES (Breast Cancer Risk after Diagnostic Gene Sequencing). Accessed April 9, 2018. https://bridges-research.eu/.

- Buchanan, Adam H., Santanu K. Datta, Celette Sugg Skinner, Gail P. Hollowell, Henry F. Beresford, Thomas Freeland, Benjamin Rogers, John Boling, P. Kelly Marcom, and Martha B. Adams. 2015. “Randomized Trial of Telegenetics vs. In-Person Cancer Genetic Counseling: Cost, Patient Satisfaction and Attendance.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 24: 961–970. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9836-6.

- Burton, H., S. Chowdhury, T. Dent, A. Hall, and N. Pashayan. 2013. “Public Health Implications From COGS and Potential for Risk Stratification and Screening.” Nature Genetics 45: 349–351. doi:10.1038/ng.2582.

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. 2011. “Recommendations on Screening for Breast Cancer in Average-Risk Women Aged 40–74 Years.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 183: 1991–2001. doi:10.1503/cmaj.110334.

- Casey, R., L. Powell, M. Braithwaite, C. Booth, B. Sizer, and J. Corr. 2017. “Nurse-Led Phone Call Follow-Up Clinics are Effective for Patients with Prostate Cancer.” Journal of Patient Experience 4: 114–120. doi:10.1177/2374373517706613.

- Chatterjee, N., J. Shi, and M. Garcia-Closas. 2016. “Developing and Evaluating Polygenic Risk Prediction Models for Stratified Disease Prevention.” Nature Reviews Genetics 17: 392–406. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.27.

- Chowdhury, Susmita, Tom Dent, Nora Pashayan, Alison Hall, Georgios Lyratzopoulos, Nina Hallowell, Per Hall, Paul Pharoah, and Hilary Burton. 2013. “Incorporating Genomics Into Breast and Prostate Cancer Screening: Assessing the Implications.” Genetics in Medicine 15: 423–432. doi:10.1038/gim.2012.167.

- Cree Board Council of Health and Social Services of the James Bay. “Breast Cancer Screening.” Accessed September 10, 2018. http://www.creehealth.org/public-health/breast-cancer-screening.

- Currie, G., R. Dingwall, M. Kitchener, and J. Waring. 2012. “Let’s Dance: Organization Studies, Medical Sociology and Health Policy.” Social Science & Medicine 74: 273–280. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.002.

- Dalpé, Gratien, Ida Ngueng Feze, Shahad Salman, Yann Joly, Julie Hagan, Emmanuelle Lévesque, Véronique Dorval, et al. 2017. “Breast Cancer Risk Estimation and Personal Insurance: A Qualitative Study Presenting Perspectives From Canadian Patients and Decision Makers.” Frontiers in Genetics 8, doi:10.3389/fgene.2017.00128.

- Davis, T. C., C. L. Arnold, C. L. Bennett, M. S. Wolf, D. Liu, and A. Rademaker. 2015. “Sustaining Mammography Screening Among the Medically Underserved: A Follow-Up Evaluation.” Journal of Women's Health 24: 291–298. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4967.

- Dent, T., J. Jbilou, I. Rafi, N. Segnan, S. Törnberg, S. Chowdhury, A. Hall, et al. 2013. “Stratified Cancer Screening: The Practicalities of Implementation.” Public Health Genomics 16: 94–99. doi:10.1159/000345941.

- Elliott, Alison M., Aizeddin A. Mhanni, Sandra L. Marles, Cheryl R. Greenberg, Albert E. Chudley, Gwendolyne C. Nyhof, and Bernard N. Chodirker. 2012. “Trends in Telehealth Versus on-Site Clinical Genetics Appointments in Manitoba: A Comparative Study.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 21: 337–344. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9406-5.

- European Commission. 2017. “Randomized Comparison of Risk-Stratified Versus Standard Breast Cancer Screening in European Women Aged 40–70.” MyPeBS. Accessed April 9, 2018 http://www.brumammo.be/documents/docs/bmm-my-pebs-clinical-trial-protocol.pdf.

- Ferryman, K., and P. Mikaela. 2018. “Fairness in Precision Medicine.” Accessed April 9, 2018. https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Data.Society.Fairness.In_.Precision.Medicine.Feb2018.FINAL-2.26.18.pdf.

- FORECEE (Female Cancer Prediction Using Cervical Omics to Individualize Screening and Prevention). Accessed April 9, 2018. https://forecee.eu.

- Gagnon, J., E. Lévesque, F. Borduas, J. Chiquette, C. Diorio, N. Duchesne, M. Dumais, et al. 2016. “Recommendations on Breast Cancer Screening and Prevention in the Context of Implementing Risk Stratification: Impending Changes to Current Policies.” Current Oncology 23: e615–e625. doi:10.3747/co.23.2961.

- Genome Québec. “Personalized Risk Stratification for the Prevention and Early Detection of Breast Cancer (PERSPECTIVE) Project.” Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.genomequebec.com/158-en/project/personalized-risk-stratification-for-the-prevention-and-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html.

- Guttmacher, A. E., J. Jenkins, and W. R. Uhlmann. 2001. “Genomic Medicine: Who Will Practice It? A Call to Open Arms.” American Journal of Medical Genetics 106: 216–222. doi:10.1002/ajmg.10008.

- Hagan, J., E. Lévesque, and B. M. Knoppers. 2016. “; Influence des facteurs organisationnels sur l’implantation d’une approche personnalisée de dépistage du cancer du sein.” Revue Santé Publique 28: 253–351.

- Hall, A. E., S. Chowdhury, N. Hallowell, N. Pashayan, T. Dent, P. Pharoah, and H. Burton. 2014. “Implementing Risk-Stratified Screening for Common Cancers: A Review of Potential Ethical, Legal and Social Issues.” Journal of Public Health 36: 285–291. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdt078.

- Hall, A. K., H. Cole-Lewis, and J. M. Bernhardt. 2015. “Mobile Text Messaging for Health: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” Annual Review of Public Health 36: 393–415. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122855.

- Hall, P., and D. Easton. 2013. “Breast Cancer Screening: Time to Target Women at Risk.” British Journal of Cancer 108: 2202–2204. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.257.

- Hilgart, J. S., J. A. Hayward, B. Coles, and R. Iredale. 2012. “Telegenetics: A Systematic Review of Telemedicine in Genetics Services.” Genetics in Medicine 14: 765–776. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.40

- Hooker, G. W., H. Peay, L. Erby, T. Bayless, B. B. Biesecker, and D. L. Roter. 2014. “Genetic Literacy and Patient Perceptions of IBD Testing Utility and Disease Control: A Randomized Vignette Study of Genetic Testing.” Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 20: 901–908. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000021.

- Houssami, N. 2017. “Overdiagnosis of Breast Cancer in Population Screening: Does it Make Breast Screening Worthless?” Cancer Biology & Medicine 14: 1–8. doi:10.20892/j doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0050

- Hwang, Stephen W., Joanna J. M. Ueng, Shirley Chiu, Alex Kiss, George Tolomiczenko, Laura Cowan, Wendy Levinson, and Donald A. Redelmeier. 2010. “Universal Health Insurance and Health Care Access for Homeless Persons.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (8): 1454–1461. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.182022.

- Institut de la statistique du Québec. “Littératie en santé: compétences, groupes cibles et facteurs favorables.” Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/sante/bulletins/zoom-sante-201202-35.pdf.

- Institut de la statistique du Québec. “Percentage of People Registered With a Family Doctor by Sex and Age Group, Montréal Health Region and all of Québec, 2013 to 2017.” Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/statistiques/profils/profil06/societe/sante/taux_med_fam_06_an.htm.

- Karcher, R., D. C. Fitzpatrick, D. J. Leonard, and S. A. Weber. 2014. “Community-Based Collaborative Approach to Improve Breast Cancer Screening in Underserved African American Women.” Journal of Cancer Education 29 (3): 482–487. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0608-z

- Khan, I., N. Ndubuka, K. Stewart, V. McKinney, and I. Mendez. 2017. “The Use of Technology to Improve Health Care to Saskatchewan’s First Nations Communities.” Canada Communicable Disease Report 43 (6): 120–124. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v43i06a01

- Lai-Goldman, M., and H. Faruki. 2013. “Strategic Issues in the Adoption of Genome-Based Diagnostics.” In Genomic and Personalized Medicine, edited by G. Ginsburg, and W. Huntington, 447–456. London: Academic Press.

- Lea, D. H., J. L. Johnson, S. Ellingwood, W. Allan, A. Patel, and R. Smith. 2015. “Telegenetics in Maine: Successful Clinical and Educational Service Delivery Model Developed From a 3-Year Pilot Project.” Genetics in Medicine 7: 21–27. doi:10.109701.GIM.0000151150.20570.E7 doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000151150.20570.E7

- Lea, D. H., K. A. Kaphingst, D. Bowen, I. Lipkus, and D. W. Hadley. 2011. “Communicating Genetic and Genomic Information: Health Literacy and Numeracy Considerations.” Public Health Genomics 14: 279–289. doi:10.1159/000294191.

- Mason, M. 2010. “Sample Size and Saturation in PhD Studies Using Qualitative Interviews.” Forum Qual. Soc. Res 11. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1428

- Mavaddat, Nasim, Paul D. P. Pharoah, Kyriaki Michailidou, Jonathan Tyrer, Mark N. Brook, Manjeet K. Bolla, Qin Wang, et al. 2015. “Prediction of Breast Cancer Risk Based on Profiling With Common Genetic Variants.” JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 107, doi:10.1093/jnci/djv036.

- Maxwell, A. E., L. L. Danao, R. T. Cayetano, C. M. Crespi, and R. Bastani. 2014. “Adoption of an Evidence-Based Colorectal Cancer Screening Promotion Program by Community Organizations Serving Filipino Americans.” BMC Public Health 14: 246. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-246

- McClellan, K. A., D. Avard, J. Simard, and B. M. Knoppers. 2013. “Personalized Medicine and Access to Health Care: Potential for Inequitable Access?” European Journal of Human Genetics 21: 143–147. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.149.

- McGowan, M. L., R. A. Settersten, E. T. Juengst, and J. R. Fishman. 2014. “Integrating Genomics Into Clinical Oncology: Ethical and Social Challenges From Proponents of Personalized Medicine.” Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 32: 187–192. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.10.009.

- Meisel, Susanne F., Nora Pashayan, Belinda Rahman, Lucy Side, Lindsay Fraser, Sue Gessler, Anne Lanceley, and Jane Wardle. 2015. “Adjusting the Frequency of Mammography Screening on the Basis of Genetic Risk: Attitudes Among Women in the UK.” The Breast 24: 237–241. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2015.02.001.

- Melton, L., B. Brewer, E. Kolva, T. Joshi, and M. Bunch. 2017. “Increasing Access to Care for Young Adults with Cancer: Results of a Quality-Improvement Project Using a Novel Telemedicine Approach to Supportive Group Psychotherapy.” Palliative and Supportive Care 15: 176–180. doi:10.1017/S1478951516000572.

- Mette, Lindsey, Anna Saldivar, Natalie Poullard, Ivette Torres, Sarah Seth, Brad Pollock, and Gail Tomlinson. 2016. “Reaching High-Risk Underserved Individuals for Cancer Genetic Counseling by Video-Teleconferencing.” The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology 14: 162–168. doi:10.12788/jcso.024 doi: 10.12788/jcso.0247

- Michailidou, Kyriaki, Sara Lindström, Joe Dennis, Jonathan Beesley, Shirley Hui, Siddhartha Kar, Audrey Lemaçon, et al. 2017. “Association Analysis Identifies 65 New Breast Cancer Risk Loci.” Nature 551: 92–94. doi:10.1038/nature24284.

- Milne, Roger L, Karoline B Kuchenbaecker, Kyriaki Michailidou, Jonathan Beesley, Siddhartha Kar, Sara Lindström, Shirley Hui, et al. 2017. “Identification of Ten Variants Associated With Risk of Estrogen Receptor Negative Breast Cancer.” Nature Genetics 49: 1767–1778. doi:10.1038/ng.3785.

- Moser, K., J. Patnick, and V. Beral. 2009. “Inequalities in Reported Use of Breast and Cervical Screening in Great Britain: Analysis of Cross Sectional Survey Data.” BMJ 338: b2025. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2025.

- Myers, Evan R., Patricia Moorman, Jennifer M. Gierisch, Laura J. Havrilesky, Lars J. Grimm, Sujata Ghate, Brittany Davidson, et al. 2015. “Benefits and Harms of Breast Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review.” JAMA 314: 1615–1634. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13183.

- National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. “Access to Health Services as a Social Determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis health.” Accessed September 7, 2018. https://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/495/Access_to_health_services_as_a_social_determinant_of_First_Nations,_Inuit_and_M%C3%A9tis_health.nccah?id=22.

- Onega, Tracy, Elisabeth F. Beaber, Brian L. Sprague, William E. Barlow, Jennifer S. Haas, Anna N.A. Tosteson, Mitchell D. Schnall, et al. 2014. “Breast Cancer Screening in an Era of Personalized Regimens: A Conceptual Model and National Cancer Institute Initiative for Risk-Based and Preference-Based Approaches at a Population Level.” Cancer 120: 2955–2964. doi:10.1002/cncr.28771.

- Paternotte, E., S. van Dulmen, N. van der Lee, A. J. Scherpbier, and F. Scheele. 2015. “Factors Influencing Intercultural Doctor–Patient Communication: A Realist Review.” Patient Education and Counseling 98 (4): 420–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.018

- Pedersen, J. S., and F. Dobbin. 2006. “In Search of Identity and Legitimation Bridging Organizational Culture and Neoinstitutionalism.” American Behavioral Scientist 49: 897–907. doi:10.1177/0002764205284798.

- Personalized Risk Assessment for Prevention and Early Detection of Breast Cancer: Integration and Implementation (PERSPECTIVE I&I). Accessed September 18, 2018. https://www.genomecanada.ca/en/personalized-risk-assessment-prevention-and-early-detection-breast-cancer-integration-and.

- PERSPECTIVE I&I (Personalized risk assessment for prevention and early detection of breast cancer: Integration and Implementation). Accessed April 9, 2018 https://www.genomecanada.ca/en/personalized-risk-assessment-prevention-and-early-detection-breast-cancer-integration-and.

- Pruthi, S., K. J. Stange, G. D. Malagrino, K. S. Chawla, N. F. LaRusso, and J. S. Kaur. 2013. “Successful Implementation of a Telemedicine-Based Counseling Program for High-Risk Patients with Breast Cancer.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 88: 68–73. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.10.015.

- Québec association of genetic counselors. Clinics Providing Genetic Counselling in Quebec. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://accgq-qagc.ca/genetics-clinics/.

- Québec Government, Ministry of Health and Social Services. “Participant Authorization for the Transmission of Personal Information in the Québec Breast Cancer Screening Program.” Accessed April 9, 2018. http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/en/document-001824/.

- Québec Government, Ministry of Health and Social Services. “Taking Part in the Québec Breast Cancer Screening Program: It’s Your Decision.” Accessed April 9, 2018 http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/msss/en/document-000289/.

- Rainey, L., D. van der Waal, A. Jervaeus, Y. Wengström, D. G. Evans, L. S. Donnelly, and M. J. Broeders. 2018. “Are we Ready for the Challenge of Implementing Risk-Based Breast Cancer Screening and Primary Prevention?” The Breast 39: 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2018.02.029.

- Regulation respecting contracting by public bodies in the field of information technologies. Chapter C-65.1, r. 5.1. Accessed September 18, 2018. http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cr/C-65.1,%20r.%205.1.

- Rico, Timóteo Matthies, Karina dos Santos Machado, Vanessa Pellegrini Fernandes, Samanta Winck Madruga, Patrícia Tuerlinckx Noguez, Camila Rose Guadalupe Barcelos, Mateus Madail Santin, Cristiane Rios Petrarca, and Samuel Carvalho Dumith. 2017. “Text Messaging (SMS) Helping Cancer Care in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy Treatment: A Pilot Study.” Journal of Medical Systems 41: 181. doi:10.1007/s10916-017-0831-3.

- Romanow, Roy J. 2002. Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada (Final Report). Saskatoon, Canada: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada.

- Shieh, Yiwey, Martin Eklund, Lisa Madlensky, Sarah D. Sawyer, Carlie K. Thompson, Allison Stover Fiscalini, Elad Ziv, Laura J. van’t Veer, Laura J. Esserman, and Jeffrey A Tice. 2017. “Breast Cancer Screening in the Precision Medicine Era: Risk-Based Screening in a Population-Based Trial.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute 109, doi:10.1093/jnci/djw290.

- Srivastava, P., and N. Hopwood. 2009. “A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8: 76–84. doi:10.1177/160940690900800107.

- Tang, S. Y., and A. J. Browne. 2008. “Race’ Matters: Racialization and Egalitarian Discourses Involving Aboriginal People in the Canadian Health Care Context.” Ethnicity & Health 13 (2): 109–127. doi:10.1080/13557850701830307.

- The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. CRTC Submission to the Government of Canada’s Innovation Agenda (2016). Accessed September 18, 2018. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/rp161221/rp161221.pdf.

- UK Government, Department of Health. 2017. Chief Medical Officer Annual Report 2016: Generation Genome. London, UK: Chief Medical Officer.

- Uy, C., J. Lopez, C. Trinh-Shevrin, S. C. Kwon, S. E. Sherman, and P. S. Liang. 2017. “Text Messaging Interventions on Cancer Screening Rates: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 19: e296. doi:10.2196/jmir.7893.

- WISDOM. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://wisdom.secure.force.com/portal/.

- Zilber, T. B. 2012. “The Relevance of Institutional Theory for the Study of Organizational Culture.” Journal of Management Inquiry 21: 88–93. doi:10.1177/1056492611419792.

- Zilliacus, Elvira M., Bettina Meiser, Elizabeth A. Lobb, Patrick J. Kelly, Kristine Barlow-Stewart, Judy A. Kirk, Alan D. Spigelman, Linda J. Warwick, and Katherine M. Tucker. 2011. “Are Videoconferenced Consultations as Effective as Face-to-Face Consultations for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Genetic Counseling?” Genetics in Medicine 13: 933–941. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a1 doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a19

- Zilliacus, E. M., B. Meiser, E. A. Lobb, J. Kirk, L. Warwick, and K. Tucker. 2010. “Women’s Experience of Telehealth Cancer Genetic Counseling.” Journal of Genetic Counseling 19: 463–472. doi:10.1007/s10897-010-9301-5.