Alzheimer’s disease has been a reference point for the promise and potential of genetic and genomic science from 1980s molecular biology through the sequencing of the human genome to ongoing efforts to identify new disease-associated loci and polygenic risk scores. Alzheimer’s disease research speaks to the potential of biomedicine to address fundamental problems of human existence, such as ageing and loss of personhood. Yet the relationship between “bench and bedside” has been rocky.

A decade after one of the headline findings of Alzheimer’s disease genetics, the identification of the ApoE e4 risk allele, Lock and colleagues argued that “no findings that derive from knowledge about the genetics of [Alzheimer’s disease] have as yet resulted in clear advances of any kind in the prevention or treatment of the disease” (Lock, Lloyd, and Prest Citation2006, 130). In subsequent years, new therapies, disease models and technologies have repeatedly run aground on the challenges presented by a complex, late-onset condition, while their pursuit prompts concern that attention is being deflected from care and social support in the context of austerity and diminishing collective responses to care in later life.

Alzheimer’s disease research, as with other areas of postgenomic science, continues to “promise big” (Richardson and Stevens Citation2015, 239). However, encounters between Alzheimer’s, genetics and postgenomic biomedicine over the last decades have resulted in consequential changes in how knowledge about the condition is generated, how the relationship between dementia and ageing is understood and how diagnosis and care are conceptualized and practice.

The papers in this special issue chart key dimensions of this changing landscape of Alzheimer’s disease, including the problematic relationship between the bench and the bedside in the contemporary moment, and explore the various individual, scientific and societal futures that each dimension implies. They build on papers and conversations at a workshop at the Brocher Foundation in 2016 on “The redefinition of Alzheimer’s disease and its social and ethical consequences.”

Background

Since the late 1970s, dementia – primarily Alzheimer’s Disease, with which around 70% of dementia cases are labeled – has come to be understood as one of the great threats facing older individuals, societies and their political and economic organization (Robertson Citation1990).

The growing promotion of Alzheimer’s Disease as a societal and biomedical challenge is an effect of the mobilization of political, scientific and clinical actors together with the growing importance of advocacy organizations (Ballenger Citation2006). Effects of these associations and mobilizations have helped reconceptualize the limits of the normal ageing and effectively conjoin senility and Alzheimer’s disease. In turn, significant work has been expended in establishing the continuity of a diagnosis between the work of Alois Alzheimer in early twentieth-century Germany, and the neurogenetics of nearly a century later (Keuck Citation2018).

The policy and scientific focus on Alzheimer’s Disease has gathered pace in the last decade, as the perceived threat of dementia associated with an ageing population has been influential in mobilizing political engagement. This has taken place both nationally and internationally, through initiatives by the G8, OECD, World Health Organization, and from national governments, perhaps most notably in the USA. For individuals, dementia features as one of the most commonly identified concerns of older adults (Corner and Bond Citation2004) as forgetting is stigmatized as an act of individualized “failure” to prevent dementia (Latimer Citation2018) in a “hypercognitive” society (Post Citation2000; Williams, Higgs, and Katz Citation2012).

The recent political emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease pulls together core themes of postgenomic biomedicine. First, it drives increased investment towards the promise of a “cure” for dementia. For example, the US National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA), signed into force by President Obama in 2013, has mobilized a rapid increase in government funding for dementia to $425 million in 2018 with the primary aim to treat or prevent Alzheimer’s disease by 2025. NAPA re-emphasizes the “urgency” of the public health need, reinforced by interventions from advocacy organizations.

However, Alzheimer’s disease has proved a particularly challenging site for biomedical research (Lock Citation2013). The growing political engagement has thus been accompanied by a scientific and clinical reorientation, in terms of the structure of research – through the growing importance of large public-private initiatives and an emphasis on “big data” (Milne Citation2018) – and, notably in the redefinition of the disease itself. The OECD’s Alzheimer’s disease initiative is typical here in its emphasis that:

therapeutic intervention in Alzheimer’s disease should start before the manifestation of symptoms … preventing the disease onset or its progression in pre-symptomatic stages. (OECD Citation2015)

The political-scientific-clinical approach to Alzheimer’s disease co-produces dementia as a future that should be considered, engaged with and acted upon in the present, by individuals and societies. Much effort has been expended in the mapping of these futures, particularly for ageing individuals. In the early 2000s, the introduction of a category of “mild cognitive impairment” (MCI) provided a first step in this process, introducing an object around which drug researchers and regulators could convene to address the potential of therapies in early stages of cognitive decline (Moreira, May, and Bond Citation2009). It also became an unstable and contested clinical category, moving from a risk status to a diagnostic label, albeit one with uncertain clinical or patient value (Beard Citation2016; Moreira et al. Citation2008). The clinical status of MCI was reinforced in revised diagnostic criteria, first in 2011 and subsequently in 2018 (Albert et al. Citation2011; Jack et al. Citation2018; Sperling et al. Citation2011a). The new criteria add further diagnostic categories encompassing individuals who have no symptoms but have biological changes thought to be associated with Alzheimer’s disease (the asymptomatic at risk or “preclinical” group) and, most recently, those who have “subtle” cognitive impairment, often identified through an individual’s subjective experience of memory loss. As Boenink, Van Lente, and Moors (Citation2016) observe, these diagnostic realignments raise questions about what exactly is being diagnosed by each test, and how reliable the resulting information is, but also how relevant and how useful.

The revised criteria distinguish between “research” and “clinical” applications. Indeed, the most recent criteria, which aim towards a biological definition of disease, are explicitly a research framework. However, as the case of MCI illustrates, this boundary is increasingly fuzzy in contemporary biomedical practice. This is particularly the case in contexts such as Alzheimer’s disease in which the range of therapies “in the clinic” is limited and in which clinical trials are seen as part of the therapeutic landscape, or genomic medicine, in which clinical investigations may be closely linked to research participation (Davis Citation2017; Dheensa et al. Citation2018; Wienroth, Pearce, and McKevitt, Citation2019). For Boenink (Citation2018), the diagnostic criteria, and accompanying moves to establish “appropriate use criteria” for biomarker technologies in the clinic, play a dual role. They first act as “gatekeepers,” identifying areas of responsible application of new diagnostics. However, Boenink argues, they also act as “trailblazers,” validating a future in which these tools will be used in the clinic, and setting out the path to this future.

Prediction, prevention and the temporality of Alzheimer’s diagnoses

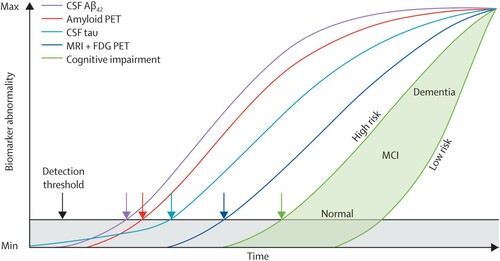

The changes in diagnostic categories are often illustrated with two recurrent tropes of twenty-first century Alzheimer’s disease research. The first is the downward arc of the continuum of Alzheimer’s disease presented by Sperling et al. (Citation2011a) that models the decline in cognitive function over years and the parting of ways between ageing and dementia. The second is that of the sigmoid “Jack curves” (), the model of biomarker progression proposed by Clifford Jack and colleagues (Citation2010, Citation2013). These two models illustrate the reconceptualization of Alzheimer’s disease as a continuum, along which an individual can be placed “in an appropriate order along a logical notion of the distance traveled along the AD pathophysiological pathway” (Jack et al. Citation2013: 213). The continuum itself is punctuated with thresholds, at which an individual can be detected moving from “normal” to “biomarker positive” or “cognitively impaired,” and thereby from healthy, to preclinical, prodromal and on to symptomatic dementia.

Figure 1. The revised “Jack Curves” proposed in Jack et al. (Citation2013), showing a model of change in different markers of change in biology and cognition associated with disease progression. The horizontal line shows the threshold at which these changes may potentially be detected.

Shifts in diagnostic classification reflect the entanglement of the history of Alzheimer’s disease with technological innovation in clinical technology. Alois Alzheimer’s use of novel staining techniques to identify tangles in post-mortem brain tissue provided support for the definition of a distinctive form of senile dementia. Later, electron microscopy techniques reinforced the reconnection of Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia. More recently, the redefinition of Alzheimer’s disease as a long-term process amenable to “presymptomatic” intervention has been inextricable from novel diagnostic technologies, notably in vivo assessments of biomarkers through lumbar punctures or brain imaging. Their construction relies on the layering of old and new technologies in the emerging diagnostic platform of Alzheimer’s disease, as cognitive tests are joined by the lumbar puncture and PET brain imaging, these latter to assess levels of the proteins beta-amyloid and tau in the spinal fluid and brain, or the ratio between them. The curves emphasize the relationships between these forms of assessment, their role in establishing both the biological and cognitive status of an individual, and their ability to retrospect and prospect trajectories of change.

The molecularized, multi-dimensional assessment of disease represented in the Jack curves and the new diagnostic categories for Alzheimer’s disease reflects the changing role of diagnosis, from the classification of patients, to the prediction of their future health based on their relationship with population models. As Armstrong (Citation2019) argues, this shift to prediction and prognosis is a major feature of new approaches to diagnosis, one that is underpinned by, and predicated upon, temporal dimensions of disease and an idea of a future trajectory. He remarks that such diagnostic classifications involve the assignment of individuals to a “population” of patients with similar prognostic trajectories, associated with a new terminology of disease, including staging, sub-types and diagnostic heterogeneity. Thus, as a “diagnosis” – albeit a contested one – categories such as MCI relate not only to current health, as to prognosis and the prediction of future change.

In her article, Swallow picks up this question of the new temporalities of diagnosis. Drawing on observations of clinical encounters and interviewees with staff members, she examines the relationship between the “imaginaries of deterioration” associated with biological definitions of disease and the crafted and negotiated futures of the clinic. She examines how practitioners negotiate tensions associated with prediction and early detection, emphasizing the material form that imaginaries of deterioration take in everyday clinical encounters and highlighting their consequences. In doing so, she examines who is impacted by the utility of earlier detection and prediction, and the values that are produced by these biomedical agendas. She identifies tensions between the redefinition of Alzheimer’s disease in terms of biology, and the “imaginaries of deterioration” found in the clinic that emphasize loss of cognition, memory and “self.” She argues that the focus on prediction associated with biomarkers has the potential to reinforce imaginaries of deterioration. Instead, building on work by Latimer (Citation2018), Beard (Citation2016) and others, she argues that we need to consider alternative discourses to account for the experiences patients describe and reconsider the importance ascribed to cognition and memory.

As Armstrong’s work suggests, the anticipatory orientation of the shift to prevention is not distinctive to Alzheimer’s disease. Indeed, Adams and colleagues argue that the “defining quality of our current moment is its characteristic state of anticipation, of thinking and living toward the future … [in which] sciences of the actual are displaced by speculative forecast” (Adams, Murphy, and Clarke Citation2009, 246). This identification of wider socio-cultural patterns is reflected in the explicit framing of Alzheimer’s disease research by clinico-scientific actors themselves – the 2010 diagnostic criteria for example emphasize that the logic of prevention draws on analogous logics with other domains that suggest similarities between Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease and cancer treatment (Sperling et al. Citation2011b).

Leibing’s contribution picks up the shift in emphasis from treatment to prevention and the confluence of different research and clinical trajectories. Leibing has previously identified the emergence of a reductive “cardiovascular logic” that dominates health promotion approaches to diverse conditions of the ageing body (Leibing and Kampf Citation2013). Here, Leibing begins from the growing recognition of the potential value of public health approaches to dementia risk reduction and the (hopeful) message that “prevention is possible,” but she argues how this plays out in policy and practice is problematic. Specifically, the “vascularization of dementia” when conceived as individualized lifestyle recommendations is value-laden, putting the moral burden for prevention on the individual, rather than recognizing that sub-groups are at different risk because of their social location. From her ethnographic study of geriatric medicine in Brazil, she explicates two possible directions for dementia prevention and unpacks how current research that presses how biological and social factors entangle in the production of dementia can be used to challenge notions that dementia is a democratic disease. On the one hand, she shows how the confluence of social inequities and inequalities in Brazil may contribute to the disadvantaged developing vascular disease, and suggests that clinicians “moral narratives” evaluate their clients as irresponsible. In contrast, focussing on community based centers with disadvantaged groups that promote preventative strategies, she argues that the classification of sub-groups at risk can be used not to perpetuate notions of a “vascular self,” but strategies of intervention as a collective and public responsibility. The move to prevention and focus on prediction also draws into focus the consequences of prediction. This is a theme of growing importance in current work on Alzheimer’s disease, both within the social sciences and in clinical engagements with new technologies for diagnosis and detection. This work recalls debates about the social, psychological and ethical implications of prediction and risk familiar from discussions of genetic testing (Arribas-Ayllon Citation2011), and are of growing importance given the increasing number of people in “asymptomatic” populations who are starting to learn information about Alzheimer’s disease risk. However, in this context, they also intersect with the specific context of dementia, and the fears, anxiety and stigma associated with cognitive decline (Latimer Citation2018; Milne et al. Citation2018).

Initial work in this area concentrated on the potential harms of learning genetic information, notably within the REVEAL study of ApoE disclosure (Green et al. Citation2009). This work suggested that, for the majority, but not all, individuals, there was no major negative impact of learning their ApoE status (Bemelmans et al. Citation2016). However, recent empirical work has concentrated on understanding how individuals make sense of and use risk information, and incorporate it into narratives of their personal and familial past and future. Following up participants in the REVEAL study, Chilibeck, Lock, and Sehdev (Citation2011), emphasized how participants interpreted genetic information as one among multiple complex causes of disease, and identified the importance of “familiarization,” whereby genetic risk estimates were embedded within pre-existing beliefs about who in the family was most likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. More recently, Mozersky et al. (Citation2017) studied the experience of 50 participants in Alzheimer’s disease prevention trials who were informed that they are at increased risk of developing dementia on the basis of amyloid biomarkers. This work again showed how new information about Alzheimer’s disease risk is positioned within existing expectations and narratives related to ageing and dementia.

The juxtaposition of biomarker and genetic testing emphasizes the need to consider the place and potential of social scientific knowledge around genetics as it relates to postgenomic biomedicine. For example, Arribas-Ayllon’s (Citation2011) discussion of ApoE testing raises the question of how much the experience derived from communication and counseling related to monogenic disorders can be transferred to susceptibility genes for complex late-onset conditions. Such questions have an ongoing practical relevance, as widely adopted guidance for communicating about biomarkers draws heavily on the genetic counseling model (Harkins et al. Citation2015).

In their contribution, Alpinar-Sencan et al. draw on qualitative work with groups of caregivers and members of the public in Germany to consider similarities and differences in lay assessments of predictive testing on a genetic and non-genetic basis, focusing on motives and anticipations behind a decision “to know or not to know” in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. They suggest a number of reasons for questioning equivalences between biomarkers and genetic tests in the context of dementia. These include the distinction between rare, monogenic conditions and complex, multi-causal diseases, and the uncertainties associated with APOE∊4. Further, they suggest the potential importance of diagnostic testing technology and disciplinary cultures in shaping patient and clinicians’ expectations of reliability or predictability. They also find that ideas of early detection and prediction establish narratives of decline and imagined future trajectories, which create imperatives to plan or divert and delay passage along these trajectories. However, they also describe how participants challenge the epistemic and economic status of the test – drawing attention to uncertainty and to the motivations of those involved in test development and marketing. Echoing the findings of Chilibeck et al., they stress the importance of personal and familial experience in shaping expectations and interpretations of genetic and non-genetic risk information.

Alpinar-Sencan et al.’s paper provides insight to inform ongoing deliberations about the value and purpose of predictive technologies in the clinic. As described above, the “trailblazing” nature of the revised diagnostic criteria means that such considerations are important. In particular, debates around the socio-ethical consequences of Alzheimer’s disease risk information continue to play an important role in shaping innovation. In Hedgecoe’s (Citation2004) analysis of the development of pharmacogenetics, he argued that, while promoters of the pharmacogenetic use of ApoE attempted to separate it from the ethical concerns associated with disclosing genetic information, their inability to do so contributed to the clinical failure of the technology. Similarly, contemporary discussions of the potential value of new technologies for early diagnosis and detection of cognitive or biomarker change are repeatedly drawn to engage with ethical considerations associated with the disclosure of biomarker status. Their value thus becomes linked to concepts of utility (a concept that itself features in multiple ways), the scientific consistency of biomarkers, and to the promise of drug development.

Definitional disarray

As a mode of engaging with the future, prevention aims to neutralize the causes of empirically assessable and identifiable threats, characterizing and engaging with uncertainties (Adams, Murphy, and Clarke Citation2009; Massumi Citation2007). As Massumi points out, “prevention operates in an objectively knowable world in which uncertainty is a function of a lack of information, and in which events run a predictable, linear course from cause to effect.” (Citation2007, 5). However, Alzheimer’s disease is emblematic of the “definitional disarray” (Lock Citation2013) of postgenomic science, in which discrete notions of bounded genetic effects have given way to dynamic and flexible understandings of biological systems. Such disarray, and its epistemic, ontological and practical consequences, echoes through efforts to predict and prevent dementia. It contributes to a picture of a condition in transition, in which the relationship between biology and environment, nosology and symptomatology is under constant local negotiation.

The emphasis on complexity and the novel directions of biomedicine since the genome has been taken up in much critical scholarship, notably that which has examined the rise of environment epigenetics and the “biosocial genome” (Müller et al. Citation2017; Pickersgill et al. Citation2013). The final set of papers in this issue draw into focus how “Alzheimer’s disease” as a biosocial entity is being constituted across sites and scales. They follow it through the spaces of laboratory science, clinical trials and clinical practice. In doing so, they provide insight into how the complexity of post-genomic science is situated and stabilized and the social, the clinical and the molecular brought into new alignments.

In their paper, Latimer and Hillman draw on this work to examine multiple situated and temporal understandings and materializations of neurodegeneration across laboratory and clinical settings. Their work, based on parallel ethnographic studies of basic neuroscience laboratories and memory clinics seeks to understand the implications of relational approaches to genomics in understanding long-term health and illness processes such as dementia. As they point out, the recognition in this approach of the situatedness of biology and a “biosocial genome” contributes to the profilerating instabilities and uncertainties associated with biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Through their empirical studies, they follow efforts to stabilize these biomarkers at different sites, as neurodegeneration is re-localized and re-situated in the worm laboratory, the animal model and the clinic. In turn, they propose that examining these divergent enactments of neurodegeneration provides a means of de-stabilizing biomarkers.

In the final paper, Milne picks up the “disjunctures” between animal modelling and the clinic highlighted by Latimer and Hillman. Drawing on long-term involvement in “translational” Alzheimer’s disease research and ethnographic work, he follows the development of a single Alzheimer’s disease pharmaceutical candidate. He uses this drug, Solanezumab, to draw into focus the translational moves through which Alzheimer’s disease is “scaled,” between rare human condition, animal model and common, late-onset disease. He positions this in the longer-term evolution of the Alzheimer’s diagnosis and the growing emphasis on biomarkers and complexity in Alzheimer’s disease research. Specifically, he points to what is critical in Solanezumab’s development, failure and success: that its failure may be connected to unstable translations and scaling between rare, common and animal diseases, but its success is in creating a “‘proto-platform’ (Gardner Citation2017) of practices and technologies associated with the definition, diagnosis and treatment of the condition” (Milne Citation2019, 8). As well as introducing the use of biomarkers, the Solanezumab case exemplifies how post-genomic epistemology and technology allow the creation of “pathological relations of equivalence” (10), between early onset Alzheimer’s Disease (the rare) and late onset Alzheimer’s Disease (the common), or between Down Syndrome Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease. This allows dementia science to shift scales, from a few individuals to high percentages of whole populations, as well as develop animal models upon which to test possible interventions. He shows how this creates the conditions of possibility for a new classification but also raises the question of how these translations create the possibility for failures of drug development, because:

Scaling genetic understandings through the materials and bodies of biomedical translation … privileges those elements of a system that are most amenable or least resistant (cf Tsing, Citation2012). (Milne Citation2019, 20)

Conclusion

The papers in this special issue thus contribute to a growing literature that sets out what is at stake in a field in which the political, the societal and the scientific are inextricably entwined, and, specifically, the value of focussing on Alzheimer’s Disease and dementia research to cast light on the dynamics of postgenomic bioscience. The promise associated with Alzheimer’s disease, its complexity and the difficulties associated with the development of new therapies and the “translation” of genetic knowledge have made it a valuable case study for the study of post-genomic biomedical science. On one hand, it illustrates the “times of great promise and great despair” (Reardon Citation2017) associated with biomedical research. On the other, it captures the diversification of the biological sciences, a move “beyond” the reductionism of genetics towards a more complex and entangled picture of the “biosocial” generated through the tools of epigenetics and an ever proliferating range of “–omics.”

Acknowledgements

The Brocher Foundation provided funding and support for the 2016 workshop that provided the basis for many of the papers in this special issue. The workshop was organized by Milne along with Shirlene Badger and Jason Karlawish, whose contribution is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Adams, V., M. Murphy, and A. E. Clarke. 2009. “Anticipation: Technoscience, Life, Affect, Temporality.” Subjectivity 28 (1): 246–265. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2009.18

- Albert, M. S., S. T. DeKosky, D. Dickson, B. Dubois, H. H. Feldman, N. C. Fox, A. Gamst, et al. 2011. “The Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations From the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia : the Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 7 (3): 270–279. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008

- Armstrong, D. 2019. “Diagnosis: From Classification to Prediction.” Social Science & Medicine 237: 112444. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112444

- Arribas-Ayllon, M. 2011. “The Ethics of Disclosing Genetic Diagnosis for Alzheimer’s Disease: Do We Need a New Paradigm?” British Medical Bulletin 100 (1): 7–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldr023

- Ballenger, J. 2006. Self, Senility, and Alzheimer’s Disease in Modern America: A History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Beard, R. 2016. Living with Alzheimer’s: Managing Memory Loss, Identity, and Illness. New York: NYU Press.

- Bemelmans, S. A. S. A., K. Tromp, E. M. Bunnik, R. J. Milne, S. Badger, C. Brayne, M. H. Schermer, and E. Richard. 2016. “Psychological, Behavioral and Social Effects of Disclosing Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers to Research Participants – a Systematic Review.” Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 8 (46): 46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-016-0212-z

- Boenink, M. 2018. “Gatekeeping and Trailblazing: The Role of Biomarkers in Novel Guidelines for Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease.” BioSocieties 13 (1): 213–231. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0065-0

- Boenink, M., H. Van Lente, and E. Moors, eds. 2016. Emerging Technologies for Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease: Innovating with Care. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Chilibeck, G., M. Lock, and M. Sehdev. 2011. “Postgenomics, Uncertain Futures, and the Familiarization of Susceptibility Genes.” Social Science & Medicine 72 (11): 1768–1775. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.053

- Corner, L., and J. Bond. 2004. “Being at Risk of Dementia: Fears and Anxieties of Older Adults.” Journal of Aging Studies 18 (2): 143–155. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2004.01.007

- Davis, D. S. 2017. “Ethical Issues in Alzheimer’s Disease Research Involving Human Subjects. Journal of Medical Ethics.” Institute of Medical Ethics 43 (12): 852–856. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103392

- Dheensa, S., G. Samuel, A. M. Lucassen, and B. Farsides. 2018. “Towards a National Genomics Medicine Service: the Challenges Facing Clinical-Research Hybrid Practices and the Case of the 100 000 Genomes Project. Journal of Medical Ethics.” Institute of Medical Ethics 44 (6): 397–403. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2017-104588

- Gardner, J. 2017. Rethinking the Clinical Gaze: Patient-Centred Innovation in Paediatric Neurology. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Green, R. C., J. S. Roberts, L. A. Cupples, N. R. Relkin, P. J. Whitehouse, T. Brown, S. L. Eckert, et al. 2009. “Disclosure of APOE Genotype for Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease.” The New England Journal of Medicine 361 (3): 245–254. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0809578

- Harkins, K., P. Sankar, R. Sperling, J. D. Grill, R. C. Green, K. A. Johnson, M. Healy, and J. Karlawish. 2015. “Development of a Process to Disclose Amyloid Imaging Results to Cognitively Normal Older Adult Research Participants.” Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 7 (1): 26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0112-7

- Hedgecoe, A. 2004. The Politics of Personalised Medicine: Pharmacogenetics in the Clinic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hillman, A., and J. Latimer. 2019. “Somaticization, the Making and Unmaking of Minded Persons and the Fabrication of Dementia.” Social Studies of Science 49 (2): 208–226. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312719834069

- Jack, C. R., D. A. Bennett, K. Blennow, M. C. Carrillo, B. Dunn, S. B. Haeberlein, D. M. Holtzman, et al. 2018. “NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14 (4): 535–562. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018

- Jack, C. R., D. S. Knopman, W. J. Jagust, R. C. Petersen, M. W. Weiner, P. S. Aisen, L. M. Shaw, et al. 2013. “Tracking Pathophysiological Processes in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Updated Hypothetical Model of Dynamic Biomarkers.” Lancet Neurology 12 (2): 207–216. NIH Public Access doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0

- Jack, C. R., D. S. Knopman, W. J. Jagust, L. M. Shaw, P. S. Aisen, M. W. Weiner, R. C. Petersen, and J. Q. Trojanowski. 2010. “Hypothetical Model of Dynamic Biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s Pathological Cascade.” Lancet Neurology 9 (1): 119. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6

- Keuck, L. 2018. “History as a Biomedical Matter: Recent Reassessments of the First Cases of Alzheimer’s Disease.” History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 40 (1): 10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-017-0177-7

- Latimer, J. 2018. “Repelling Neoliberal World-Making? How the Ageing–Dementia Relation is Reassembling the Social.” The Sociological Review 66 (4): 832–856. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118777422

- Leibing, A., and A. Kampf. 2013. “Neither Body nor Brain: Comparing Preventive Attitudes to Prostate Cancer and Alzheimer’s Disease.” Body & Society 19 (4): 61–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X13477163

- Lock, M. 2013. The Alzheimer Conundrum: Entanglements of Dementia and Aging. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lock, M., S. Lloyd, and J. Prest. 2006. “Genetic Susceptibility and Alzheimer’s Disease.” In Thinking About Dementia: Culture, Loss and the Anthropology of Senility, edited by A. Leibing and L. Cohen, 123–156. Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Massumi, B. 2007. “Potential Politics and the Primacy of Preemption.” Theory and Event 10: 2.

- Milne, R. 2018. “From People with Dementia to People with Data: Participation and Value in Alzheimer’s Disease Research.” Biosocieties 13 (3): 623–639. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-017-0112-x

- Milne, R. 2019. “The Rare and the Common: Scale and the Genetic Imaginary in Alzheimer's Disease Drug Development.” New Genetics and Society. Online ahead of print, doi:10.1080/14636778.2019.1637718.

- Milne, R., A. Diaz, S. Badger, E. Bunnik, K. Fauria, and K. Wells. 2018. “At, with and Beyond Risk: Expectations of Living with the Possibility of Future Dementia.” Sociology of Health & Illness 40 (6): 969–987. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12731.

- Moreira, T., J. C. Hughes, T. Kirkwood, C. May, I. McKeith, and J. Bond. 2008. “What Explains Variations in the Clinical use of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) as a Diagnostic Category?” International Psychogeriatrics 20 (04): 697–709. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007126

- Moreira, T., C. May, and J. Bond. 2009. “Regulatory Objectivity in Action: Mild Cognitive Impairment and the Collective Production of Uncertainty.” Social Studies of Science 39 (5): 665–690. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312709103481

- Mozersky, J., P. Sankar, K. Harkins, S. Hachey, and J. Karlawish. 2017. “Comprehension of an Elevated Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography Biomarker Result by Cognitively Normal Older Adults.” JAMA Neurology 75 (1): 44–50.

- Müller, R., C. Hanson, M. Hanson, M. Penkler, G. Samaras, L. Chiapperino, J. Dupré, et al. 2017. “The Biosocial Genome?” EMBO Reports 18 (10): 1677–1682. doi: https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201744953

- OECD. 2015. “Enhancing Translational Research and Clinical Development for Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias.” OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Pickersgill, M., J. Niewöhner, R. Müller, P. Martin, and S. Cunningham-Burley. 2013. “Mapping the New Molecular Landscape: Social Dimensions of Epigenetics.” New Genetics and Society 32 (4): 429–447. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2013.861739

- Post, S. G. 2000. The Moral Challenge of Alzheimer Disease: Ethical Issues From Diagnosis to Dying. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Reardon, J. 2017. The Postgenomic Condition: Ethics, Justice, and Knowledge after the Genome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Richardson, S., and H. Stevens. 2015. “Approaching Postgenomics.” In Postgenomics: Perspectives on Biology after the Genome, edited by S. Richardson and H. Stevens, 232–241. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Robertson, A. 1990. “The Policies of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Case Study in Apocalyptic Demography.” International Journal of Health Services 20 (3): 429–442. doi: https://doi.org/10.2190/C8AE-NYC1-2R98-MHP1

- Sperling, R. A., P. S. Aisen, L. A. Beckett, D. A. Bennett, S. Craft, A. M. Fagan, T. Iwatsubo, et al. 2011a. “Toward Defining the Preclinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations From the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 7 (3): 280–292. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003

- Sperling, R. A., C. R. Jack, P. S. Aisen, and P. S. Aisen. 2011b. “Testing the Right Target and Right Drug at the Right Stage.” Science Translational Medicine 3 (111): 111c. m33. NIH Public Access doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609

- Tsing, A. L. 2012. “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-Nested Scales.” Common Knowledge 18 (3): 505–524. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/0961754X-1630424

- Wienroth, M., C. Pearce, and C. McKevitt. 2019. “Research Campaigns in the UK National Health Service: Patient Recruitment and Questions of Valuation.” Sociology of Health & Illness 41 (7): 1444–1461. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12957

- Williams, S. J., P. Higgs, and S. Katz. 2012. “Neuroculture, Active Ageing and the ‘Older Brain’: Problems, Promises and Prospects.” Sociology of Health & Illness 34 (1): 64–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01364.x