Abstract

Public Umbilical Cord Blood (UCB) banking is defined by the dominant bioethics and biomedical literature as working in a regime of valuation that connects the social value of solidarity and the clinical value of collected quality UCB. Adopting the notion of registers of valuing (Heuts, F., and A. Mol. 2013. “What Is a Good Tomato? A Case of Valuing in Practice.” Valuation Studies 1 (2): 125–146), this paper challenges the aforementioned view. By exploring the Italian public system of UCB banking, it discusses disputes around the organization of the logistic of UCB donation, inspired by divergent registers of valuing enacted by involved actors. This paper focuses on the Italian public UCB banks’ involvement in experimental clinical protocols, using cells derived from UCB. It demonstrates how these experimental applications are deployed by Italian UCB bank practitioners to legitimize their work and to advance claims of jurisdictional monopoly over UCB banking and donation. It concludes that concrete arrangements of UCB banking are the outcome of negotiations among involved actors.

Introduction

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) is a source of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) used in transplants to treat hematological malignancies and blood and inherited metabolic disorders. Employed as an alternative to bone marrow transplantation, UCB is collected at birth and stored in biobanks. The distinction and the opposition between public and private UCB banks has been widely debated, where the former collect voluntarily donated UCB units and redistribute them, mainly for transplantations to non-related patients (allogeneic), while the latter sell directly to parents a service of exclusive ownership of their new-born child’s UCB for possible future uses on the same donor (autologous) or on a family member. However, UCB-derived stem cells are not only used in hematological clinical protocols. Similar to bone marrow-derived stem cells, which are used as “a source of tissue-engineered regenerative medicines” (Brown, Kraft, and Martin Citation2006, 330) in several clinical trials outside the field of hematology (Hauskeller Citation2017; Hauskeller, Baur, and Harrington Citation2018), UCB also contains different types of stem cells employed in experimental protocols for treating neurological conditions and injuries (e.g. Cotten et al. Citation2014; Dawson et al. Citation2017).

Within the so-called narrative of opposition (Hauskeller and Beltrame Citation2016a) predominant in bioethical and biomedical literature, the distinction between public and private banking has also been linked to the uses of UCB-derived stem cells. Martin, Brown, and Turner (Citation2008) have proposed a distinction between a “regime of truth” and a “regime of hope” for characterizing the uses of UCB-derived stem cells within the two banking regimes. Public UCB banks operate in what can be characterized as a “regime of truth,” namely “a body of claims, legitimated on the basis of current present-oriented ‘evidence-based’ support for existing applications of [U]CB stem cells” (Martin, Brown, and Turner Citation2008, 136). Private UCB banks, on the contrary, work in a “regime of hope,” by advertising possible future applications of UCB-derived stem cells outside hematology, so that the value of UCB is “oriented towards the biological future” of regenerative medicine (Waldby Citation2006, 64; see also Waldby and Mitchell Citation2006; Brown and Kraft Citation2006). Public banks tend to frame these applications as highly speculative and “refrain from mobilizing the future and stress instead currently proven therapeutics within a ‘regime of truth’ oriented to a moral economy of altruistic mutuality” (Martin, Brown, and Turner Citation2008, 137).

However, as this paper will show, the use of UCB-derived stem cells outside the established protocols in hematological transplantation is not the prerogative of the private sector. Public UCB banks do indeed provide discarded UCB units to public research institutions (Hauskeller and Beltrame Citation2016a), which often work on new experimental applications of HSCs and other UCB-derived stem cells. This paper focuses on the involvement of Italian public UCB banks in the establishment of novel experimental clinical protocols, using cells and blood products derived from the UCB fraction usually discarded in UCB banking: i.e. platelet gel derived from UCB plasma, collyria and eye drops obtained from UCB serum, as well as UCB red blood cells.

Instead of positioning these new experimental protocols within the context of those promissory discourses which, according to Brown, Kraft, and Martin (Citation2006), characterized the establishment of the use of HSCs in clinics (see also Martin, Brown, and Kraft Citation2008), this paper shows how they are presented within a phase of consolidation in the context of a regime of established, evidence-based and routine applications. Moreover, these protocols are not deployed in order to contrast the claims of private UCB banking. This paper will instead show how they are employed by the Italian public UCB bank practitioners in what, following Abbott (Citation1988), I define as jurisdictional disputes around the organization of UCB donation and collection logistics in Italy.

Contrary to some assumptions of the dominant discourse in bioethics and biomedical literature, which posits a straightforward association between the social value of solidarity related to donation and the clinical value of collected UCB units, this paper argues that the harmonization of different values is something that should be accomplished. Building on the notion of “register of valuing” (Heuts and Mol Citation2013), this paper demonstrates how the concrete arrangements of UCB collection and banking logistics are the outcomes of the enactment of divergent registers of valuing, which orient the practices of involved actors (biobank practitioners, healthcare regulators, donors’ associations and politicians). This involves disputes between relevant actors who claim professional jurisdiction over the field of UCB banking and the logistics of donation and collection. In particular, this paper shows that the involvement in experimental applications of UCB-derived cells and blood products is deployed by UCB bank practitioners as a means of legitimizing their work, to advance their professional monopoly over the practices of UCB donation and collection, and to affirm a register of valuing that they feel is overrated in the current organization of UCB banking in Italy.

Registers of valuing in the field of public UCB banking

As first noted by Waldby (Citation2006), the dominant discourse in bioethics and biomedical literature around public UCB banking was inspired by the famous work of Titmuss (Citation1970), “The gift relationship: From human blood to social policy,” in which the British sociologist demonstrated that a system of blood supply based on free, voluntary donation not only provides blood of a better quality than a system based on market exchanges but also preserves the social order by promoting reciprocity and mutuality among fellow citizens, thereby reinforcing the web of social bonds and obligations. According to this view, public UCB banking “is promoted with reference to a solidaristic moral economy of gift and altruistic participation in imagined community and nationhood” (Brown Citation2013, 98) and the public UCB bank is seen as “a site for the constitution of both collective health and the best values of citizenship” (Waldby Citation2006, 57). The dominant discourse, what Hauskeller and Beltrame (Citation2016a) have called “a narrative of opposition,” tends to structure a rigid institutional regime of valuation in which the clinical value of UCB coincides unproblematically with the solidaristic value of the act of donation (e.g. European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies Citation2004).

By focusing exclusively on the public-private opposition in UCB banking, however, not only does this view fail to account for new public-private mixed banking models and other overlaps and hybridization between the two sectors (see Hauskeller and Beltrame Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Sleeboom-Faulkner and Chang Citation2016; Sui and Sleeboom-Faulkner Citation2019), but it also overlooks some tensions arising around the act of UCB donation and collection among different stakeholders. Brown (Citation2013) and Machin (Citation2016), for example, have explored the tensions among expecting parents, banks operators, midwives and neonatologists around donating UCB versus the practice of delayed cord clamping (i.e. transferring the UCB to the new-born). This paper adds to these analyses a discussion on tensions between the social value of the act of donation and the clinical value of collected UCB within a public system, showing how these values can come into conflict and, instead of being unproblematically associated, they are enacted in concrete UCB donation and collection logistical arrangements.

Analytically, this paper builds on the notion of registers of valuing (Heuts and Mol Citation2013) in order to contrast the rigid regimes of valuation posited by the dominant discourse in bioethical and biomedical literature. Some STS works on biobanks (e.g. Romero-Bachiller and Santoro Citation2018; Tupasela Citation2006; Wyatt, Cook, and McKevitt Citation2018), genomic databases (e.g. Singh Citation2018) and biomedical data platforms (Tempini Citation2017) have shown how these infrastructures are sites of multiple processes of valuation and valorization, including economic, epistemic and social values (e.g. related to identity-building and shared sociality). This literature has shown the existence and relevance of different values and practices of valuation enacted by involved actors. As Beltrame and Hauskeller (Citation2018, 25) stated, the production of multiple values is “the outcome of both the entanglement of a very specific banking configuration and the practices of participation and valuing enacted by biobanks staff, researchers and participants.” This involves avoiding rigid categories of institutional regimes of value production in favor of exploring the role of registers of valuing.

Indeed, registers of valuing aim to capture the enactment of different practices of valuation in concrete situations in order to assess value. Firstly, the term “register” indicates only a shared relevance (Heuts and Mol Citation2013, 129) that merely enables, rather than defines, the process of valuation. A shared relevance means that there is a common focus of attention on some problems or objects, allowing the social process of valuation to start. Secondly, the term “valuing” indicates concrete and situated practices or, as Heuts and Mol (Citation2013, 128, note 6) put it, valuing as something people do, rather than something caught in or framed by a culture. Using this framework, it is not only possible to study the practices of valuation but also to understand how divergent perceptions can result in tensions and conflict.

A register of valuing in which the relevance is put on the promotion of social solidarity through donation will prioritize the expansion of this altruistic act, as much as is possible. Donated UCB would be valued as an act of civic engagement in the common good that transforms what is referred to as “otherwise clinical waste” in UCB banking discourse (Brown Citation2013) into a gift. A different register of valuing, in which the relevance is instead put on those features of UCB units that enable successful engraftment and the match of the human leucocyte antigens (HLA) of the donor with those of the recipient, will prioritize practices of UCB collection aimed at maximizing the total cellularity and the HLA variability of banked UCB.

In biobanking, these registers of valuing must be enacted while avoiding tensions. Donors should be enrolled in participation, with discourses of gift-giving deployed to legitimize biobanking activities (Tutton Citation2004, Citation2008). At the same time, tissues collected must fulfill quality requirements around their use in research or clinics. Even if these registers of valuing are not incompatible in themselves, a combination of ethical values and clinical quality cannot be taken as a given. Concrete logistical setups of UCB donation and banking have to be arranged in a way that accomplishes both the social values of solidarity and the clinical values of quality UCB (Williams Citation2015). When tensions occur, contrasts and negotiations between registers of valuing result in what, following Abbott (Citation1988), can be named jurisdictional claims. According to Abbott (Citation1988, 2) professions are claiming a jurisdictional monopoly over certain domains of knowledge and their application against outsiders and other professions. In this sense, since “jurisdictional boundaries are perpetually in dispute” (ibid.), not only are public UCB bank practitioners involved in struggles against private UCB banks in terms of legitimizing methods of banking UCB but also against politicians and other parties involved in the logistical organization of UCB donation. The discourse around new experimental uses of cells and blood products derived from UCB enters into these jurisdictional claims and tensions between registers of valuing.

Italy presents an interesting case for the studying of these dynamics. In the first instance, this is because Italian UCB banks are directly involved in the development and clinical applications of these novel experimental protocols. Secondly, this is because the Italian system has been established following a register of valuing, which maximized opportunities to donate, while questions around the quality of banked UCB have been partially underrated, generating tensions with UCB bank practitioners. The Italian system of UCB banking is currently under re-organization aimed towards placing the quality of banked UCB at the core of the operating logic of the whole system. Therefore, it is an exemplary case in terms of studying how registers of valuing are mobilized in jurisdictional disputes and enacted in concrete logistical arrangements of UCB donation and collection.

Data and methods

The data presented in this paper comes from a three-year study (2015–2018) of UCB banking in Italy. Different methods were adopted in this study. I have undertaken a documentary analysis of regulations and reports, policy documents, statements, guidelines and standards published by the relevant medical authorities.

In order to study the principles inspiring the logistics of UCB donation in Italy, I performed a discourse analysis on several documents produced by different institutions. I considered position statements, published documents and the webpages of medical and donors’ associations directly involved with biobanks in promoting UCB donation. I have also analyzed webpages and supplementary informative materials provided by institutions involved in UCB banking in Italy (public UCB banks and hospitals acting as collection sites). This material was analyzed using the software Atlas.ti for coding relevant parts of the texts. One particular approach to critical discourse analysis was adopted by looking at how the discourse is constitutive of social identities, social relations, and systems of knowledge and belief (Fairclough Citation1992).

Finally, in order to study the registers of valuing adopted by UCB practitioners and the meaning they attribute to the experimental uses of UCB-derived products, documentary and discourse analysis were complemented by ten semi-structured interviews with seven biobanks operators, one biobanks inspector and two members of two regulatory bodies (regulators). Semi-structured interviews, lasting between 50 and 90 min, were recorded and transcribed in full. Each transcript was coded for themes using Atlas.ti and read three times, focusing on the views of practitioners regarding research and experimental protocols using UCB-derived products. The seven public UCB banks were chosen by using both a geographical criterion and a distinction around the size of the biobanks. Operators of three banks in the north of Italy were interviewed, as well as three in the center of Italy and one in the south of Italy. Two are considered large banks, two are of medium size and three are small.

Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee at the University of Exeter, College of Social Sciences and International Studies. Interviewees signed a consent form to participate in the interviews. In order to grant anonymity to the interviewees and avoid identification, any geographical or institutional references have been removed from the reports of the interviews.

The Italian Cord Blood Network and national regulation

The first public UCB banks were established in Italy during the 1990s. In 2002 the then Minister of Health promulgated the first ordinance regulating the field of UCB banking, by prohibiting the establishment of private banks. After several years in which the ordinance was renewed, in 2009 the definitive regulatory framework began to be enforced. The framework prohibits the establishment of private banks within Italy’s national territory, forbids personal or family banking within the Italian borders and hampers the export of UCB for autologous and family uses to private banks located abroad (Repubblica Italiana Citation2009).

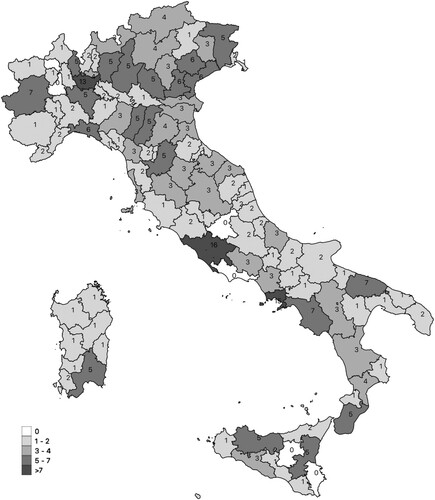

The same regulation officially established the Italian Cord Blood Network (ITCBN), consisting in 18 regional UCB banks with a complex governance structure and involving the Italian Ministry of Health, Regional Governments, the National Blood Service (“Centro Nazionale Sangue”; CNS), the National Transplant Service (“Centro Nazionale Trapianti”; CNT), the Italian Bone Marrow Donor Registry (IBMDR), which manages the Italian register of available HSC sources and local health units. Moreover, it is stated that one of the aims of the Italian Cord Blood Network is “the promotion, in collaboration with interested voluntary associations, of initiatives aimed at promoting the solidaristic donation of umbilical cord blood to the population and in particular to donor mothers” (Repubblica Italiana Citation2009, 26). Associations such as ADISCO (the Association of Women UCB Donors) and ADOCES (the Association of HSC Donors) have thus gained an important role in promoting UCB donation and in shaping the organizational arrangement of UCB collection sites. Indeed, under the pressure of these donors’ and other patients’ associations, regional governments and the directors of local health units have progressively extended the network of collection sites (which are usually public hospitals). According to the most recent report from the CNS, 18 public banks in Italy are connected with 269 collection sites, covering the 58% of annual childbirths (CNS Citation2017, 16). In 2014, as shown in , these collection sites amounted to 320, distributed across the whole national territory, and accounting for 66.5% of all births in that year (CNS Citation2014, 18).

Figure 1. Distribution of collection sites in the Italian provinces (number of collection sites).

Source: Elaboration on data of CNS (Citation2019).

In fact, if the network of public UCB banks and collection sites has increased over the years through the push for enlarging the opportunities to donate, then the ratio between donated and banked UCB units is set at 7% (CNS Citation2017, 11). This has triggered a debate around the functioning of a system in which the 93% of UCB units collected from donations are discarded as unsuitable for transplantation. Suitability for transplantation is, indeed, evaluated on the basis of cellular enumeration, by assaying the number of vital CD34 cells (i.e. HSCs) or by using a proxy combining the volume of UCB units and the Total Nucleated Cell (TNC) count. On the basis of international standards, the IBMDR enforces the minimum threshold of volume or TNC to a UCB unit to be banked. The high rate of discarded units is partially physiological; however, one factor influencing the low percentages of collected UCB units suitable for being banked is that, due to the extension of the network of collection sites, there are no sufficient resources to have a permanent and dedicated collection staff. The system relies on obstetricians and midwives who have been trained by the biobanks but who lack the necessary expertise and experience for collecting quality units in an effective manner. As reported by UCB bank operators, “the training of the staff doing collection is directly proportional to the quality of collection” (Biobank operator 1).

Moreover, a study based on data from 2012 (published in 2018) and promoted by the CNS and CNT (Pupella et al. Citation2018) has also called into question the economic feasibility of the Italian system, showing that the cost of collection is lower in large UCB banks and making the suggestion to “concentrate cost-consuming activities in no more than three to five [cord blood banks] to maintain a sustainable … network” (Pupella et al. Citation2018, 320). Accordingly, a drastic reduction and rationalization of collection sites (around 100), has also been suggested, in order to concentrate resources in sites with better performances in terms of collection-banking ratio. As a consequence, tensions between registers of valuing have emerged.

Conflicting registers of valuing in the Italian logistics of UCB donation

As presented in the previous section, it is the same Italian regulation that considers expanding the opportunity to donate as paramount when structuring the logistics of UCB collection in Italy. This was partially realized by the actions of the donors’ associations. For example, ADISCO (the Association of Women UCB Donors) declares that its mission is to “promote donation and conservation of umbilical cord blood through activities aimed at creating a culture of allogeneic and solidaristic donation” (ADISCO Citation2019) and “to promote initiatives aimed at incrementing cord blood donation by creating and educating groups of volunteers active throughout the country” (Sciomer Citation2010, 317). A 2011 position statement, signed by eight medical professional associations and supported by ADISCO and other donors’ and patients’ associations, states that:

The network of maternity units/collection sites must be incremented in order to respond optimally to the increasing demand for UCB collection. Institutions, scientific societies, and voluntary associations commit themselves to supporting the ethical value of donation as an inalienable collective capital for the health of citizens. (AIEOP et al. Citation2011, 3–4, emphasis added)

[Our region] wanted to grant donation to everybody. After a general training course to all the obstetricians, it has opened the door to everybody. Because, otherwise, there would have been cases of injustice as one mother could donate, another could not. This was the conception. (Biobank operator 6)

We have lost sight of who should be at the heart of our thoughts, that is a patient waiting for a transplant. Instead, we put the mothers at the heart. However, they are not the protagonists of this thing; they are co-protagonists of this program. Important co-protagonists … but it is not around them that the whole program gravitates. The program gravitates around the patient. And to the patient, I must provide beautiful units, with a lot of cells, with a lot of CD34 – well collected and well screened for … If we move our gaze from the patient to the mothers … then we must allow all mothers to donate anywhere, at any time in the day, and any day of the year. But then we’ve really missed our goal. (Biobank operator 1)

Donating is an opportunity, not a right! I don’t have the right to donate. I assure you that a 5% banking rate, that is the average which we are doing now, is immoral! Because against that 5%, there are 95% not banked but collected, incur expenses, and often they are neither recycled or used for research. Therefore, we fight to find something of use also for units we don’t bank, or I feel it is immoral to continue to waste public money. (Biobank operator 7)

There are other two points of interest in the previous excerpt. The first is that it expresses two different definitions of waste in the two registers of valuing. The discourse of avoiding what would otherwise be waste, as Waldby and Mitchell (Citation2006) and Brown (Citation2013) have remarked, is an important rhetorical and legal device for allowing UCB conservation. However, in the register of valuing underpinning the extended logistics of donation, “what would otherwise be waste” refers to non-donated UCB. Letting UCB go to clinical waste, in this view, prevents the circulation of a gift that, by embedding the social values of solidarity, promotes cohesion in the fabric of society. On the contrary, in the register of valuing whose relevance is on the clinical quality of UCB, “waste” refers to collected UCB units with scarce cellularity. This is due to the fact that they will be discarded as they are unable to circulate from donor to recipient or, if banked, they “occupy freezer space, and uselessly consume liquid nitrogen” representing “a completely immobilized inventory” (Regulator 1, emphasis added). As pointed out by Appadurai (Citation1986, 4), the value of any object is not an inherent feature but is set by its circulation; the two registers of valuing have “divergent perceptions” (ibid.) of the value of UCB, as they conceive of circulation in two different ways. The logistics of collection based on extending donation reduces the circulation of UCB for transplantation by creating instead “immobilized inventories.” The second point refers to the theme of finding “something of use for units we are not banking” (Biobank operator 7). This is the entry point of the research on, and experimental clinical applications of, UCB-derived cells and products in re-drawing the boundaries of good UCB banking practices.

From hope to truth: research on UCB-derived cells and jurisdictional claims

The possible research use for donated UCB units below the threshold for being banked is largely used in the promotion of donation, which aims to show that a non-banked unit is not waste, as reported in this informative leaflet prepared by the IBMDR, and largely used by biobanks and collection sites:

Your donation, if not corresponding to the quality requirements for transplantation, can be an important resource for research purposes. Units already addressed to be banked for transplantation could be used for research purposes just in case, due to unexpected events, they will prove to be no more suitable for preservation. (IBMDR Citation2016, 6)

Well, let’s say that we discard a lot anyway because units for research also needs specific characteristics. They shouldn’t have more than 24 hours; otherwise, they are too old for researchers. They need a 100% vitality. Or they need good cellularity anyway, and also this can be an obstacle. So, not all the units given for research are of use. Research laboratories need certain characteristics as well. (Biobank operator 3)

According to Martin, Brown, and Turner (Citation2008, 37), one of the features of the regime of truth is that public UCB banks orient their research activities “around improving the use of cord blood in its current application … with several working towards possible ‘cell expansion’” (Martin, Brown, and Turner Citation2008, 137). The case of cell expansion – i.e. the possibility of multiplying the number of HSCs so as to also use UCB units with scarce cellularity – particularly exemplifies how public UCB bank practitioners conceive experimental research in a regime of truth. For example, according to this operator, cell expansion can be framed as a “promissory past” (Brown, Kraft, and Martin Citation2006):

If we had already had good results from cell expansion, we would have solved a great limitation of cord stem cells. However, at the moment, it is still a dream. Important steps have been made compared to only 5–7 years ago. But we have not yet reached the goal. Currently, cell expansion has not provided great results. And consequently, we have to acknowledge this. And for these reasons we are exploring other routes; we are breaking other grounds. (Biobank operator 4)

Consolidation and legitimization: experimental uses of UCB-derived blood products

“We are breaking other grounds,” stated Biobank operator 4, and “we fight to find something of use also for units we don’t bank” (Biobank operator 7). This is the case in the three clinical applications employing the usually discarded fractions of UCB (plasma, serum and red blood cells) for producing platelet gel, collyrium or eye drops and blood cells for transfusion. These applications are not presented as promissory, but as in a consolidating phase. For example, in an informative website for potential UCB donors, it is reported that:

In recent years, regarding the use of cord blood, a new platform of cellular therapy is emerging and is deserving public investment toward applications that have showed positive results in pilot studies (platelet gel, transfusion for pre-term babies, collyriums for epithelial regeneration, etc.). (Calabria Cord Blood Bank Citation2019)

The first type of UCB-derived product is the Cord Blood Platelet Gel (CBPG), which is derived from the plasma fraction (usually discarded in UCB banking) by adopting a technique patented by the Fondazione IRCCS, which manages the Milan Cord Blood Bank (patent no.: US 8,501,170 B2). A fraction named platelet-rich plasma is gelificated using an additive (Parazzi, Lazzari, and Rebulla Citation2010) to produce a cellular product used to repair diabetic foot ulcers (Volpe et al. Citation2017) and for treating epidermolysis bullosa (Tadini et al. Citation2015). CBPG is a therapeutic product based on existing experience in the use of platelet gel from adult peripheral blood in orthopedics. Several public banks, as they are established within the transfusion service of hematology departments, routinely produce “adult” platelet gel. However, CBPG “seems to contain better growth factors and has greater anti-inflammatory capacities than ‘adult’ platelet gel and it is, therefore, more efficient in regenerating tissues” (Biobank operator 7). Not only do public UCB banks take part in the development of the protocol and in experimental applications but, as explained by a biobank operator:

We prepare it [CBPG] when requested for some patients in our hospital. The use of platelet gel for ulcers is now established, and thus it can be requested by clinicians as we have the bank and as we produce blood products from UCB. For instance, maxillofacial surgery requests a lot of platelet gel, and we provide it routinely, sometimes from UCB and sometimes from adult peripheral blood. (Biobank operator 6)

Similarly to this is the case of topical eye drops derived from UCB serum used for epithelial regeneration in eye syndromes. Topical eye drops and collyrium are derived from UCB serum, another blood component usually discarded, and are employed in the treatment of a vast range of conditions, from the simple dry eye syndrome to tissue regeneration in cases of severe keratopathies affecting eyes (Versura et al. Citation2016).

[eye drops derived from UCB serum] are more effective than pharmaceutical ones, because in serum and plasma there are several growth factors and a lot of proteins, a lot of things that one could hardly reproduce pharmacologically. They are useful for the regeneration of damaged tissues … We have this production line, and we manufacture eye drops from UCB-derived serum (and we do research) for patients with serious keratopathies provoked by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, that is graft-versus-host-disease, and patients with scleroderma-like Sjögren syndrome. … And we carried out experimental protocols approved by the ethics committee. We routinely produce this serum eye drop. (Biobank operator 6)

The third use of blood products derived from UCB is that of red blood cells used for transfusions in extremely underweight pre-term babies (Bianchi et al. Citation2015), as explained by a biobank operator:

We set a system, a clinical study around neonatal allogeneic transfusion, using blood cells from a donated cord, that is blood cells with fetal hemoglobin for preterm new-born babies. They are small babies who don’t have adult hemoglobin, and thus we support them for several weeks by transfusing a kind of hemoglobin which is physiologically compatible for them. This is a way to reconvert a good deal of UCB units because a unit lacking in stem cells does not mean that it does not constitute a good unit for red blood cells. (Biobank operator 7)

At this point, we speak no more of stem cells, but of cord blood in general, since we are working on growth factors from cord blood which are better and in a greater quantity than in peripheral blood, and which are used to prepare products like platelet gel and eye drops used for other pathologies. They justify the existence of the biobank because this demonstrates that donation, which justifies the existence of these structures, is always a very important act. If the unit is not transplantable, we get the message that donation is always important as nothing goes to waste: on what is not transplantable, I work on and use it to do other things. (Biobank operator 4)

Conclusions

The case of Italy analyzed in this paper shows how public UCB bank practitioners are involved in disputes around the jurisdictional monopoly over the practices of UCB banking that involve confrontations around the organization of donation and collection. The production of values, both social and clinical, is the outcome of these disputes and negotiations. The development and clinical application of experimental protocols with UCB-derived blood products are also part of these jurisdictional disputes inspired by different registers of valuing. In fact, rather than framing these new experimental protocols as promissory futures, they are anchored in the regime of truth of the established applications. This is demonstrated by the fact that public UCB bank practitioners do not simply explore experimental protocols but also declare that they are routinely engaged in the manufacture of cell- and blood products for current applications in tissue repair. By claiming their exclusive epistemic authority and jurisdictional monopoly over these applications, they are also re-framing the morality of donation in line with their registers of valuing: from an act of social solidarity, which has value in itself, to an ethical act when it leads to useful clinical products. This is according to a register of valuing in which it is the clinical usability that is of worth, which also generates moral value. Focusing on clinical qualities, UCB bank operators can also claim jurisdiction on the logistics of UCB donation. Experimental uses, anchored in a regime of truth, become a powerful means by which to further legitimize the existence and work of public UCB banks and, moreover, to support their claim of defining how a public system of UCB banking and donation should work. This is particularly significant in the Italian context, where an extended network of public banks and collection sites has been established for promoting the realization of values of solidarity through maximizing possibilities to donate.

The field of public UCB banking is, therefore, not characterized by a fixed regime of valuation in which solidarity unproblematically coincides with the quality of UCB banked. The concrete organizational arrangements of the logistic of UCB donation, collection and banking are the outcome of negotiations between divergent registers of valuing put forth by different parties. In some contexts, divergences can begin conflicts and tensions. The analytical concept of registers of valuing is, therefore, useful in studying how tensions arise and are managed, as organizational arrangements in biobanking result from the interactions among involved parties (biobankers, healthcare regulators, political authorities and donors’ associations). Solidarity and clinical quality are enacted in concrete arrangements in order to accomplish both the ethical values promoting and legitimizing participation and the provision of tissues for clinical needs, research and experimental applications. In this way, instead of positing the alignment of values as a given, it is possible to understand how these values are enacted and realistically accomplished in concrete banking configurations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Christine Hauskeller for her invaluable supervision during my MSC fellowship, which led to this publication. I also thank Niccolò Tempini, Matteo Santus and Massimiano Bucchi for their comments on a draft version of this article. Finally, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers who offered me well-received suggestions to improve this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Lorenzo Beltrame http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7235-8683

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, A. 1988. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ADISCO (Associazione Donatrici Italiane Sangue del Cordone Ombelicale). 2019. “Chi siamo.” Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.adisco.it/chisiamo.php.

- AIEOP (Associazione Italiana Ematologia Oncologia Pediatrica) et al. 2011. “Position Statement. Raccolta e conservazione del sangue cordonale in Italia”. Accessed March 24, 2019. https://www.adisco.it/chisiamo/7.pdf.

- Appadurai, A. 1986. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspectives, edited by A. Appadurai, 3–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beltrame, L. 2014. “The Bio-Objectification of Umbilical Cord Blood: Socio-Economic and Epistemic Implications of Biobanking.” Tecnoscienza 5 (1): 67–90.

- Beltrame, L., and C. Hauskeller. 2018. “Assets, Commodities and Biosocialities. Multiple Biovalues in Hybrid Biobanking Practices.” Tecnoscienza 9 (2): 5–31.

- Bianchi, M., C. Giannantonio, S. Spartano, M. Fioretti, A. Landini, A. Molisso, G. M. Tesfagabir, et al. 2015. “Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Red Cell Concentrates: An Innovative Blood Product for Transfusion Therapy of Preterm Infants.” Neonatology 107 (2): 81–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000368296

- Brown, N. 2013. “Contradictions of Value: Between Use and Exchange in Cord Blood Bioeconomy.” Sociology of Health & Illness 35 (1): 97–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01474.x

- Brown, N., and A. Kraft. 2006. “Blood Ties: Banking the Stem Cell Promise.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 18 (3–4): 313–327. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777044

- Brown, N., A. Kraft, and P. Martin. 2006. “The Promissory Pasts of Blood Stem Cells.” BioSocieties 1 (3): 329–348. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855206003061

- Calabria Cord Blood Bank. 2019. “Banca del Cordone.” Accessed July 4, 2019. http://www.ospedalerc.it/banca-del-cordone/.

- CNS (Centro Nazionale Sangue). 2014. “Banche di sangue di cordone ombelicale. Report 2014.” Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/Report%202014.pdf.

- CNS (Centro Nazionale Sangue). 2017. “Banche di sangue di cordone ombelicale. Report 2017.” Accessed March 21, 2019. https://www.centronazionalesangue.it/sites/default/files/Report%202017.pdf.

- CNS (Centro Nazionale Sangue). 2019. “Rete banche sangue cordonale.” Accessed July 2019. https://www.centronazionalesangue.it/node/64.

- Cotten, C. M., A. P. Murtha, R. N. Goldberg, C. A. Grotegut, P. B. Smith, R. F. Goldstein, K. A. Fisher, et al. 2014. “Feasibility of Autologous Cord Blood Cells for Infants With Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy.” The Journal of Pediatrics 164 (5): 973–979. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.036

- Dawson, G., J. M. Sun, K. S. Davlantis, M. Murias, L. Franz, J. Troy, R. Simmons, M. Sabatos-DeVito, R. Durham, and J. Kurtzberg. 2017. “Autologous Cord Blood Infusions Are Safe and Feasible in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Results of a Single-Center Phase I Open-Label Trial.” Stem Cell Translational Medicine 6 (5): 1332–1339. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/sctm.16-0474

- European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies. 2004. “Ethical Aspects of Umbilical Cord Blood Banking. Opinion No. 19 to the European Commission, 16 March 2004.” Accessed March 16, 2019. http://www.eurosfaire.prd.fr/lifescihealth/documents/pdf/PublOp19_sang_ombilical.pdf.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fondazione IRCCS. 2017. “Consenso informato per la raccolta e conservazione allogenica del sangue cordonale e per l’uso delle unità non idonee per il trapianto a scopo di ricerca.” Accessed July 4, 2019. https://www.policlinico.mi.it/AMM/DonneEGravidanza/M.01.515-CB.CONS_Rev.17_Consenso_donazione_per_uso_non_dedicato.pdf.

- Hauskeller, C. 2017. “Can Harmonized Regulation Overcome Intra-European Differences? Insights from a European Phase III Stem Cell Trial.” Regenerative Medicine 12 (6): 599–609. doi: https://doi.org/10.2217/rme-2017-0064

- Hauskeller, C., N. Baur, and J. Harrington. 2018. “Standards, Harmonization and Cultural Differences: Examining the Implementation of a European Stem Cell Clinical Trial.” Science as Culture 28 (2): 174–199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09505431.2017.1347613

- Hauskeller, C., and L. Beltrame. 2016a. “The Hybrid Bioeconomy of Umbilical Cord Blood Banking: Re-Examining the Narrative of Opposition Between Public and Private Services.” BioSocieties 11 (4): 415–434. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/biosoc.2015.45

- Hauskeller, C., and L. Beltrame. 2016b. “Hybrid Practices in Cord Blood Banking. Rethinking the Commodification of Human Tissues in the Bioeconomy.” New Genetics and Society 35 (3): 228–245. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2016.1197108

- Heuts, F., and A. Mol. 2013. “What Is a Good Tomato? A Case of Valuing in Practice.” Valuation Studies 1 (2): 125–146. doi: https://doi.org/10.3384/vs.2001-5992.1312125

- IBMDR (Italian Bone Marrow Donor Registry). 2016. “La donazione del sangue da cordone ombelicale.” Accessed March 24, 2019. www.sanmatteo.org/site/home/attivita-assistenziale/diventare-mamma-al-san-matteo/donazione-di-sangue-cordonale/documento7968.html.

- Machin, L. L. 2016. “The Collection of “Quality” Umbilical Cord Blood for Stem Cell Treatments: Conflicts, Compromises, and Clinical Pragmatism.” New Genetics and Society 35 (3): 307–326. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2016.1209109

- Martin, P., N. Brown, and A. Kraft. 2008. “From Bedside to Bench? Communities of Promise, Translational Research and the Making of Blood Stem Cells.” Science as Culture 17 (1): 29–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09505430701872921

- Martin, P., N. Brown, and A. Turner. 2008. “Capitalizing Hope: The Commercial Development of Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Cell Banking.” New Genetics and Society 27 (2): 127–143. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636770802077074

- Parazzi, V., L. Lazzari, and P. Rebulla. 2010. “Platelet Gel from Cord Blood: A Novel Tool for Tissue Engineering.” Platelets 21 (7): 549–554. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/09537104.2010.514626

- Pupella, S., M. Bianchi, A. Ceccarelli, D. Calteri, L. Lombardini, A. Giornetti, G. Marano, M. Franchini, G. Grazzini, and G. M. Liumbruno. 2018. “A Cost Analysis of Public Cord Blood Banks Belonging to the Italian Cord Blood Network.” Blood Transfusion 16 (3): 313–320.

- Repubblica Italiana. 2009. “Disposizioni in materia di conservazione di cellule staminali da sangue del cordone ombelicale per uso autologo – dedicato.” Decreto 18 Novembre 2009 del Ministero del lavoro, della salute e delle politiche sociali. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana. N. 303, 31 Dicembre 2009, pp. 19–21. Accessed July 4, 2019. http://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2009/12/31/303/sg/pdf.

- Romero-Bachiller, C., and P. Santoro. 2018. “Hybrid Zones, Bio-Objectification and Microbiota in Human Breast Milk Biobanking.” Tecnoscienza 9 (2): 33–60.

- Sciomer, C. 2010. “The Italian Association of Cord Blood Donors (ADISCO): 15years of History and Activities.” Transfusion and Apheresis Science 42 (3): 317–319. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2010.03.003

- Singh, J. S. 2018. “Contours and Constraints of an Autism Genetic Database: Scientific, Social and Digital Species of Biovalue.” Tecnoscienza 9 (2): 61–88.

- Sleeboom-Faulkner, M., and H.-C. Chang. 2016. “The Private, the Public and the Hybrid in Umbilical Cord Blood Banking – A Global Perspective.” New Genetics and Society 35 (3): 223–227. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2016.1219227

- Sui, S., and M. Sleeboom-Faulkner. 2019. “Hybrid UCB Banks in China – Public Storage as Ethical Biocapital.” New Genetics and Society 38 (1): 60–79. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2018.1549982

- Tadini, G., S. Guez, L. Pezzani, M. Marconi, N. Greppi, F. Manzoni, P. Rebulla, and S. Esposito. 2015. “Preliminary Evaluation of Cord Blood Platelet Gel for the Treatment of Skin Lesions in Children With Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa.” Blood Transfusion 13 (1): 153–158.

- Tempini, N. 2017. “Till Data Do Us Part: Understanding Data-Based Value Creation in Data-Intensive Infrastructures.” Information and Organization 27 (4): 191–210. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.08.001

- Titmuss, R. 1970. The Gift Relationship: From Human Blood to Social Policy. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Tupasela, A. 2006. “Locating Tissue Collections in Tissue Economies – Deriving Value from Biomedical Research.” New Genetics and Society 25 (1): 33–49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636770600603469

- Tutton, R. 2004. “Person, Property and Gift. Exploring Languages of Tissue Donation to Biomedical Research.” In Genetic Databases: Socio-Ethical Issues in the Collection and Use of DNA, edited by R. Tutton and O. Corrigan, 19–38. London: Routledge.

- Tutton, R. 2008. “Biobanks and the Biopolitics of Inclusion and Representation.” In Biobanks. Governance in Comparative Perspective, edited by H. Gottweis, and A. Petersen, 159–176. London: Routledge.

- Versura, P., M. Buzzi, G. Giannaccare, A. Terzi, M. Fresina, C. Velati, and E. C. Campos. 2016. “Targeting Growth Factor Supply in Keratopathy Treatment: Comparison Between Maternal Peripheral Blood and Cord Blood as Sources for the Preparation of Topical Eye Drops.” Blood Transfusion 14 (2): 145–151.

- Volpe, P., D. Marcuccio, G. Stilo, A. Alberti, G. Foti, A. Volpe, D. Princi, R. Surace, G. Pucci, and M. Massara. 2017. “Efficacy of Cord Blood Platelet Gel Application for Enhancing Diabetic Foot Ulcer Healing After Lower Limb Revascularization.” Seminars in Vascular Surgery 30 (4): 106–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2017.12.001

- Waldby, C. 2006. “Umbilical Cord Blood: From Social Gift to Venture Capital.” BioSocieties 1 (1): 55–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1745855205050088

- Waldby, C., and R. Mitchell. 2006. Tissue Economies. Blood, Organs, and Cell Lines in Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Williams, R. 2015. “Cords of Collaboration: Interests and Ethnicity in the UK’s Public Stem Cell Inventory.” New Genetics and Society 34 (3): 319–337. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2015.1060116

- Wyatt, D., J. Cook, and C. McKevitt. 2018. “Participation in the BioResource. Biobanking and Value in the Changing NHS.” Tecnoscienza 9 (2): 89–108.