?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Industrial organisations increasingly face problems with recruiting its workforce. Recent years have seen the most acute labour shortages. To overcome this challenge, organisations must provide work that is attractive to a new and wider workforce. This article thus argues that the task of designing attractive work systems should be a task of ergonomics. To this end, the article positions the notion of attractive work within sociotechnical systems theory. It then shows how current perspectives on attractive work, while important, do not address the complex issues of actually designing attractive work systems. In doing so, the article expands on sociotechnical systems theory and theories on attractive work to suggest a conceptualisation that allows for the understanding of the notion of attractive work with reference to different actors and their position in relation to the work system and socio-organisational context. The conceptualisation is then applied to a case from the mining industry to investigate its applicability. The analysis finds that designing attractive work systems necessitates a user-centric approach with a widened scope. Concern must include all users, even those who in fact will not directly use the designs. In short, a sensitivity to the larger society, the external environment, is needed.

Relevance to human factors/ergonomics theory

This article argues for the inclusion of the notion of attractive work in ergonomics science. It shows how issues relating to the attraction and retention of a workforce are issues of ergonomics. This requires reformulation of concepts such as user-centric design.

Introduction

The significance of attractive work

Industrial organisations increasingly face problems securing – i.e. attracting and retaining – labour. One survey (Manpower Group Citation2018) found that 45% of employers cannot find the skills they need. For large organisations this figure is 67%. Effects of labour shortages in general include an economy that operates less efficiently and resources that are not put to their most productive use (Barnow, Trutko, and Piatak Citation2013). Concretely, labour shortages may, for example, lead to societies that are unable to fulfil future demands for pensions and elderly care (Salmenhaara Citation2009), industries such as mining that are unable to meet production targets (Lee Citation2011), workers having to work more hours than they desire which may result in lower output (Barnow, Trutko, and Piatak Citation2013). Lately, these issues has received more attention. But current efforts are not enough – 2018 reached a 12-year high, global ‘talent shortage’ (Manpower Group Citation2018). Strategies employed by companies today feature educational efforts, branding etc. – organisational strategies (see Ehrhart and Ziegert Citation2005). This focus is too narrow; this article hopes to show that securing labour also requires focusing on work itself, where work must be designed to be attractive with a new generation in mind.

The discussion on attractive work should not be reduced to the ability of an organisation to secure labour per se. A workplace that has all the labour it requires is not necessarily attractive. Likewise, an organisation that cannot secure enough labour is not necessarily unattractive. Indeed, plenty of jobs are probably unattractive – at least partly so, or have significant potential for improvement – yet does not have a shortage of staff. Consider for example the many workplaces with poor working condition that people actually work in. But questions of attractiveness tend to become salient when organisations are unable to recruit labour. An organisation that has all the labour it needs might not be very interested in whether it is actually attractive or not. Moreover, an organisation could have all its ‘workforce needs’ fulfilled but then see demands for a larger workforce. A potential inability to then recruit does not have to mean that the organisation is unattractive.

There is also a distinction between attractive work and attractive organisations. For instance, an organisation can be attractive even if its work is not (Åteg and Hedlund Citation2011). This article hopes to show that, in the end, both organisation and work must be attractive; if the organisation attracts, work cannot then repel. The division suggests that attracting and retaining labour are separate problems. Some have instead phrased it as a single problem of attractiveness (e.g. Hedlund Citation2007): attractive work is both work that people like having (retention) and want to have (attraction). A discussion of work that attracts but does not retain is not productive. All organisations involve work. So attractive organisations must also provide attractive work. (Consider as an example the organisations that continuously replaces its labour instead of making sure it stays. It may not have a labour shortage, but is it attractive?)

Thus questions of labour attraction and retention – indeed, of attractive organisations in general – are questions of attractive work. It makes sense then that ergonomics, being the study of work, should concern itself with developing attractive work. In fact, in line with the dual goal of ergonomics of improving system performance as well as well-being (International Ergonomics Association Citation2017), one could say that designing attractive work strives for system performance through well-being. If a work system does not provide good enough work, this will inhibit its performance through a lack of resources (cf. Carayon and Smith Citation2000). As work is a human activity, a work system cannot reach its goals without human involvement. In short, attractiveness ensures work-system performance.

Research on attractive work includes applicant attraction, retention, commitment and engagement. It extends over fields such as organisational and vocational behaviour, human resource management and organisational psychology (Åteg and Hedlund Citation2011). But ergonomics research investigating the issue is rarer. And often the question is treated implicitly when it does receive attention (but see e.g. Turisova and Sinay Citation2016).

Accordingly, this article makes the case for the recognition of work (system) attractiveness as a subject of ergonomics. In this it makes the case for designing these systems to be attractive, as opposed to working though organisational measures after the fact. The purpose is to outline a thinking of work system design that recognises attractiveness as an important (emergent) property of the system. The article positions the question within sociotechnical systems theory (cf. Carayon et al. Citation2015); see next subsection. As such, focus is on the design challenges and constraints that the notion of attractiveness introduces. Thus, unlike much previous research, what features actually make work systems attractive are not central. Instead, what must go into facilitating attractive work systems takes centre stage.

To clarify, a focus on (individual) factors or components is not sufficiently helpful in the actual design of attractive work systems. Previous research has identified factors that contribute to making work attractive (e.g. Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén Citation2004). These feature in attractive work systems. But their unique significance in each system and for each individual is so dependent on each system and individual that knowing of them and trying to accommodate them is not enough. Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén (Citation2004), for example, recognised the individual dependability of each factors, but the present study seeks to analyse what this means for the design of attractive workplaces. Or, in other words, previous research has demonstrated that the creation of attractive work systems is possible – indeed, what factors can feature in these systems. How this is accomplished is not as clear, nor is how to find a balance in cases where all important factors cannot be fulfilled or are conflictive. Åteg and Hedlund (Citation2011, 22) argued that other theories on attraction and retention does provide this perspective but primarily in the sense of mechanisms or logics of how or why attraction is created: ‘they explain by which processes the individual becomes attracted’. This is not the same as explaining how work systems that are attractive can be designed – a clear task for the discipline of ergonomics, and the concern of this article.

Attractive work and sociotechnical theory

Sociotechnical systems theory is used to frame this article and to position the notion of attractive work within ergonomics. More precisely it uses the model of sociotechnical systems developed by Carayon et al. (Citation2015). A full account of sociotechnical theory lies beyond the scope of this article (the curious reader is directed to e.g. Mumford Citation2006 or Carayon et al. Citation2015); instead this section summarises the most salient features.

As the name suggests, sociotechnical theory distinguishes between two subsystems: the technical and the social. The technical subsystem includes technology, machines, tools, equipment and work organisation; while the social systems include individuals and teams, their needs and requirements (Mumford Citation2006). Sociotechnical theory seeks (to understand) the joint optimisation between the two systems (cf. the dual goals of ergonomics). This is understood to involve the interaction among components, systems and external environment (Carayon et al. Citation2015).

None of this is static. For instance, workers adapt to the sociotechnical system which in turn adapts the system itself. Carayon et al. (Citation2015) referred to this as symbiotic interaction. That is, unlike traditional systems theory, sociotechnical theory does not assume that system components are deconstructable to discrete units and events, such that they are individually analysable; relationships are indirect, and their form is not given a priori but from the actual interactions within the system and between other systems. ‘Emergent properties’, Carayon et al. (Citation2015, 550) argued, is the system theoretical label for this phenomena, which ‘arise only when components interact and are not exhibited within the behaviour of individual components’. While the focus of these authors was safety, the present study suggests that attractiveness is also an emergent feature of sociotechnical systems. The inclusion of individual components in a work system (work rotation, good pay, flexible hours etc.), while separately attractive (Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén Citation2004), does not directly result in an attractive work system. Only when workers, themselves components in the system, interact with other system components does the nature of the ‘attractiveness property’ emerge. In other words, what is designed to happen needs distinguishing from what actually happens (Carayon et al. Citation2015).

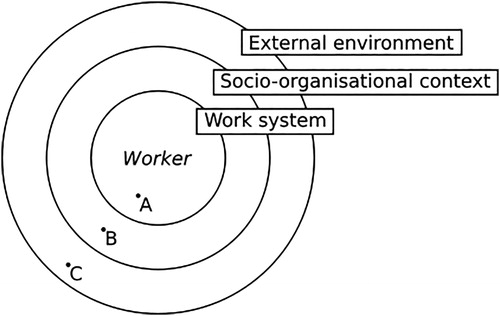

Work systems in this sense are ‘created’ in the interaction between social and technical systems. In creating system components, a designer can actively influence the technical subsystems (i.e. the work system is never fully ‘designed’ by a designer). In safety and the management of risk, concern has been with the design of systems to ensure safety. This focus has resulted in hierarchical models such as Rasmussen (Citation1997) and Leveson (2011). For the purposes of the present article these models are too complex; the further analyses below show that strictly placing workplace attractiveness in one of the levels outlined by these models is hard. Furthermore, the analysis here is less inclined towards the structures regulating and controlling work attractiveness, which interests the safety models. As Carayon et al. (Citation2015, 558) argued, ‘We need to complement this approach with a deeper understanding of work at “the sharp end” and its relationship to the rest of the organisation and the external environment’. To this end they proposed a concentric model consisting of the worker at the centre, then the work system, socio-organisational context, and external environment. Importantly, this model is not hierarchical but rather acknowledges that outer layers influence attractiveness through proximate and distal layers (Carayon et al. Citation2015).

The work system is the local context in which work activities are performed, while the socio-organisational system refers to the social and organisational culture and structure within the organisation (Carayon et al. Citation2015). The external layer represents the social, legal and political environment. In particular, the fact that this layer includes demographic context is important. Carayon et al. (Citation2015) noted that this broader occupational demographic influences organisations, their culture and so on. This demographic is essentially the concern of work attractiveness – it is the ‘target’ of attractiveness. Where for safety, understanding is important due to demographic influence on performance and safety, work attractiveness has the additional task of attracting part of this demographic; their viewpoints, wishes, desires, etc. must be taken into consideration in design to make the work system suitable for them. So while a safety-view on this model is concerned with e.g. legislature, regulatory and union influence on safety, work attractiveness faces a bigger challenge.

The present article makes use of this model to relate important concepts. presents the model, where it has been modified to include potential positions of actors/individuals; these different positions stand to have important bearing on attractive work system design.

Figure 1. A modified model of sociotechnical systems. Possible locations of actors/individuals denoted with A–C. (Based on Carayon et al. Citation2015).

Attractive work systems

Some current thought on attractive work

The terminology used in the discussion on work that is attractive differs between researchers and includes ‘attractive work’ (e.g. Biswas et al. 2017; Åteg and Hedlund Citation2011) and ‘attractive workplaces’ (e.g. Lööw et al. Citation2018). (This section makes no claim to be exhaustive on thought on attractive work and suchlike – see e.g. Åteg and Hedlund Citation2011 or Ehrhart and Ziegert (Citation2005) for this. Rather focus is on some important features of current thought to give a sense of how it needs to be developed further.) For clarity’s sake, here attractive work takes place at workplaces that are attractive – thus attractive workplaces are workplaces in which people want to work. In positioning the article in the fields of ergonomics as well as avoiding questions of what classifies as work and what classifies as workplaces, it uses the term ‘work system’ (e.g. Carayon and Smith Citation2000) which includes both the workplace and the tasks undertaken in that system.

What is meant by an attractive work system, then, is a system in which people want to work and keep working. This makes individual and subjective views on attractiveness central – a work system as either attractive or unattractive ultimately depends on the perspective of individuals. Hedlund (Citation2007) proposed that work attractiveness has an internal and external perspective. In the external perspective an individual judges the work from the ‘outside’, for instance someone seeking employment or deciding upon a job. In the sociotechnical systems model this corresponds to an individual in the external environment (position in ). In the internal perspective an individual judges the work from the ‘inside’, for example someone already employed at the workplace in question. This refers to someone in the work system in the sociotechnical systems model (position

in ). In this sense a work system can be both attractive and unattractive simultaneously, when attractive internally but not externally for instance. Crucially, individuals, being either inside the work system or in its external environment, ‘classify’ the system.

In this view, defining attractiveness as the ability to recruit labour is unsuitable (an organisation that is unable to recruit is not necessarily unattractive). For Hedlund (Citation2007) only when work is attractive in both an internal and external perspective can work classify as attractive. The other combinations of the two dimensions result in three additional classifications: unattractive, idealised, hidden and attractive (see ). With this reasoning, attractiveness as an emergent property arises not only from interaction within the work system but also from its interaction with the external environment.

Table 1. Internal and external attractiveness as conceptualised by Hedlund (Citation2007).

This model classifies jobs and industries. Unattractive jobs no one wants. An individual would take an unattractive job out of necessity. This could be due to a lack of available jobs, a dire personal economic situation and so on. Work, or industries, can also be unattractive because of norms (activities that damage the environment are unattractive, for instance).

Hidden jobs are essentially ‘good’ jobs but that people do not know about or do not consider attractive, i.e. only those already in the work system consider them attractive. This can be a problem of people not knowing about the job – the job might be in a small sector or remote location and thus does not get coverage in the media. Hidden jobs can also exist in sectors that are generally characterised as having unattractive jobs, even if the particular case is different.

Idealised jobs are those that are seen as good but in reality are not, i.e. the external environment views them as positive but they are negative if viewed from within the work system. This can be because norms make people view them as suitable, or the image of the job is different from reality.

Attractive jobs are the ideal. They are jobs that people want to have and like having.

Classification within this model gives a notion of the direction required of change, i.e. workplace interventions and their intended effects (e.g. should it affect internal or external attractiveness – or both). Being able to position a job or workplace in these terms, thereby forming an understanding for what course of action the situation requires, is useful. But in this situation shortcomings in current understanding of attractive workplaces and their design also become more obvious.

Problems with current thought on attractive work

To exemplify some of the problems of current thought on attractive work, consider the conceptualisation of attractiveness presented above. (To clarify, these are mainly problems from an ergonomics design point of view. Moreover, these accounts – here and above – are focused on thought that can be used in the design of attractive work.) It can help in classification and in decisions on future action. For instance, having classified a job as idealised the course of action should be reasonably clear: increase internal attractiveness (change the work system). But in what way? Moreover, what is internal attractiveness and how does it differ from external attractive (is there any difference at all)? That is, while there is a distinction between external environment and work system, are demands from these positions different? With hidden jobs, is the problem one of better communicating the attractive aspects of the job to improve external attractiveness? Or is it that those who consider the job as attractive are already employed – which is not enough for system performance – and the job therefore qualifies as hidden? In the latter case, communicating positive aspects is not the solution – the work system needs redesign.

Research such as Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén (Citation2004) and Hedlund, Andersson, and Rosén (Citation2010) breaks attractiveness into diverse factors. Given the sheer amount of factors that potentially affect attractiveness, it appears as a daunting task to try to summarise the status of these into a single classification of either unattractive or attractive. A job has both positive and negative features that on the one hand appeal to individuals differently, and on the other hand do not ‘cancel each other out’ or can be thought of in terms of cost–benefit (e.g. ‘I don’t like my working environment but the pay is good, so I consider the work attractive’). At least the point here is that, because the notion is of attractiveness as an emergent property, the result of the interaction between these component cannot be predicted before the fact.

Question of boundaries also arise. At what point does work go from being attractive to unattractive, from idealised to attractive and so on? At an individual level this might be trivial: a person simply ‘makes’ this judgement. But different people have the same job. If half the employees of a job considers the job attractive and the other half considers it unattractive, what is the final classification? Here the diversity of the social system introduces the need for considerable adaptability or variability on the technical system. To add to the complexity, taking a wider array of social demands into consideration may in fact be the solution to problem of attractiveness.

The problem grows in complexity still when going from binary to scalar classification, as well as when recognising that a job consists of different and sometimes conflicting factors. Given, for instance, three factors of varying contribution to attractiveness, is it possible for two less important factors to compensate for shortcomings in the more important factor? How do their combination affect the final attractiveness classification?

The consideration of the external perspective and environment in general increases complexity. Which scope does the external perspective/environment include? Local, national, international? Any population or a certain population? Most work is probably externally unattractive when considering a very wide perspective (e.g. a national population) – most people do not want the same job or want to work for the same company.

Finally, current thought does not clearly indicate the location of different ‘actors’. For instance, current models tends assume that a person is looking for a job or is employed in a job. This is important for classifying jobs but overlooks two important aspects. First, how often do companies, for instance, have access to this kind of information? Second, because employees that an organisation tries to retain or attract are not the ones who are able to change the character of work, the notion of attractive work should therefore be expanded to include those that actually create or otherwise develop work.

On expanding the concept of attractive work

This article suggests a conceptualisation of attractiveness with reference to three constructs: the preference of the individual, the individual’s view of the work system, and the work system’s actual properties (properties as in both emergent and of components).

The preference of the individual refers to what an individual considers attractive work. Which is not necessarily specific to a certain job but can be general. It does not matter if this individual is in the work system or the external environment, an applicant or employee, and so on. Ehrhart and Ziegert (Citation2005) referred to this as person characteristics and accounted for theories that predict attraction depending on the fit between person and environment characteristics.

The location of the individual becomes important when considering their view. The individual’s view of the work system represents what an individual thinks of a particular work system. (In their review Ehrhart and Ziegert Citation2005, referred to this as the ‘perceived environment’.) It differs from the actual properties of the work system (called ‘actual environment’ by Ehrhart and Ziegert Citation2005), which is independent from the individual. Here an individual is external when they judge the attractiveness of a work system indirectly, from the external environment (position in ) for instance. In which case the image of the work system stands in for its actual properties. This image is ‘constructed’ by the company through its communication, employees of the work system talking with others about the system, and so on. If the individual is internal, i.e. in the work system (position

in ), it has direct access to the properties of the work system – the view and the properties are the same in this case. The theories accounted for by Ehrhart and Ziegert (Citation2005) concern how individuals process information about actual characteristics, how these result in perceived characteristics affecting attractiveness. The addition of the present article is the suggestion that there is a point where these characteristics coalesce.

The external environment is not passive but can influence the work system and its properties. For instance, laws can mandate that certain aspects have a specific design. The external environment also affects the preferences of the individual, e.g. through norms. In turn individuals are part of the external environment and thus affects it. This can be compared to how individuals adapt the technical system and thus the work system as a whole; individuals form and are formed by the external environment, and the work system forms and is formed by the external environment. For instance, properties of the work system has effects on the surrounding environment. If it involves unhealthy tasks, people will get sick. This can cause the external environment to impose new laws.

The work system is rarely directly affected in this way. Instead, ‘actors’ are affected, who in turn influence the work system. The actors are in turn individuals and have their own preferences and views.

Actors and their role

The interest of this article is how to design work systems that are attractive. The aim of organisations striving for this should be to understand, and then change in accordance to, how properties of the work system relate to and align with individuals’ preferences as well their views of that work system. Thus, organisations can primarily change attractiveness by changing the actual properties of work or how they communicate those properties. The required change depends on where the ‘mismatch’ occurs, e.g. if actual properties do not match the view of those properties or if they do not match individual preferences. This puts into focus the socio-organisational context; organisations enact change from this context (position in ). Either they enact it outwards, towards the external environment. This can include changing the image of the organisations and its workplaces (e.g. branding) as well as educating and informing (changing perceptions). Or they enact change inwards, towards the work system, in which case its properties is the target. Change in this case can also originate from the external environment, such as when procuring new technology. This way actors in the external environment become important even when considering inwards change.

In all this, actors have their own views and preferences as they too are individuals. But these views and preferences are different from those of e.g. applicants and workers. The role of actors is to account for preferences in relation to properties and views. This depends on the current situation of the organisation as well as the preferences and views of the ‘intended’ workforce. The problem is that an actor has limited access to individual preferences and views the same way an external individual has limited access to the properties of the work system. Designing attractive work systems requires recognition of this fact.

It also possible for actors to aim to change preferences of the individual (both internal and external), e.g. information campaigns and education can change individual preferences. Other strategies include lobbying. For individual companies these may appear as unsuitable strategies – or even insidious if certain factors are changed against the individual’s best interest. Still, the next section looks at cases where changing preferences could be justified.

Objective and subjective attractiveness

The conceptualisation so far implies that individual preferences represent something positive. The assumption has been that important factors are also positive, e.g. for the employee’s health or motivation. This is not always the case. This section discusses factors that can be understood as subjectively and objectively good or bad. Referencing alienation as conceptualised Blauner (Citation1964, 15) introduces the notion:

… a general syndrome made up of a number of different objective conditions and subjective feeling-states which emerge from certain relationships between workers and the sociotechnical settings of employment.

Blauner’s findings on textile and automobile workers illustrate the difference between objective and subjective alienation. Both were objectively alienated, but only the automobile workers experienced subjective alienation. To Blauner this was because norms and values of the societies where the textile mills (i.e. the workplaces of the textile workers) were located prevented subjective alienation; the external environment interacted with the work system and individual so that the work system in some sense emerged to have positive attractiveness, even though its individual components may have been negative in an ‘objective’ perspective. Mayo (Citation1945) demonstrated a similar effect. Every change to working conditions, ‘objectively’ good or bad, increased productivity and motivation. That is, the individual’s preference of a factor as attractive or unattractive does not necessarily say anything about that practice being ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

This distinction is required to avoid adapting practices that individuals want but, for instance, can be negative to employees’ health (cf. Turisova and Sinay Citation2016). It builds in part on normative ambitions, that attractive work should be healthy, safe etc. (see Johansson, Johansson, and Abrahamsson Citation2010; Johansson and Abrahamsson Citation2009). For instance, extended work hours is a practice that has negative health effects (Dembe et al. Citation2005; Harrington Citation2001) but that workers at times prefer due to the additional days off that follow from the practice. The distinction is also required so that organisations can provide workplaces that are attractive in a long-term perspective. As an example, Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén (Citation2004) found that people consider autonomy an attractive job characteristic. At the same time, jobs with high demands and where the employee has limited control (i.e. where autonomy is low) result in poor health (Karasek and Theorell Citation1990). Similarly, good air quality is attractive (Åteg, Hedlund, and Pontén Citation2004). Failure to provide good air quality leads to work-related health problems. These negative effects can affect the view on the work as attractive, as society considers ill-health negative.

Another aspect of this issue, in trying to enact change, is resistance. For instance, when organisations implement equality measures they often encounter resistance (e.g. Abrahamsson Citation2002; Acker Citation2006). Those resisting these changes then view them as negative – but this alone cannot be the basis for classifying the changes as unattractive.

In other words, attractive work cannot only be work that people want to have; it must also be work that is good (or at least not bad) for employees. To this end it can be argued that there are some workplace features that organisations should provide, even if they are not requested. But this is far from simple. Positing that attractive work should be safe does not mean that safe work is attractive – work can arguably be made safe by strict routines, limiting decision latitude and so on (features that do not constitute attractive practices).

Furthermore, the relative importance of each factor could relate to an ‘objective–subjective’ distinction. For instance, if there are factors that result in a ‘creep’ towards lower attractiveness, then as long as these factors are present, the workplace will continuously ‘decay’ towards lower levels of attractiveness (such as if a workplace results in sick-leave due to stress). These factors must have priority if the long-term goal is attractive work systems (as opposed to only seeking temporary fixes). Consider the connection to motivators and hygiene factors of Herzberg (e.g. Citation1968; work attractiveness closely relates to work motivation; Biswas et al. 2017; Åteg and Hedlund Citation2011). Factors that dissatisfy are different from those that satisfy. This article suggests that attractiveness functions in the same way, and that the non-fulfillment of certain factors will hinder the fulfilment of others.

Coming back then to strategies for organisations. The notion that factors can be good and bad – and objectively and subjectively so – complicates the situation further. With (objectively) positive factors the situation may potentially be trivial. Elsewhere, a strategy is not obvious. The problem is perhaps not most pressing with job seekers but rather with other ‘externals’, such as designers and developers. That is, if an engineer tasked with designing an attractive work system has a view on what is attractive that is actually negative, this can have significant consequences. And a further question becomes, how to judge the negative–positive property?

In seeking an answer to these questions, and in attempting to exemplify the workings discussed above, the article will turn to some empirical examples. To reiterate, then, the model distinguishes between three concepts:

The location of actors (those who actively influence designs) and individuals (which includes actors). They can be located in the external environment, socio-organisational context, or the work system.

The views and preferences of individuals (including those of actors). How these are formulated will depend on the location of the individual.

The work system’s actual properties.

Case study: exploring attractive work in the mining industry

This section explores the applicability of the conceptualisation of attractive work systems by furthering an understanding of their facilitation. To do this, the section uses two case studies of new technology in the mining industry.

On the empirical material and its context

The empirical material comes from investigations undertaken within the frames of a European Union-funded research and development project for new mining technology. Part of the purpose of the project is to develop technology that contributes to making mining more socially sustainable and attractive. It seeks to use technology to tackle issues of social sustainability and attractiveness.

The problem of lacking attractiveness is already significant in the mining industry (Oldroy Citation2015; Hebblewhite Citation2008; Lee Citation2011). Changes to mining work demands a workforce that is more qualified and with skills and competences such as abstract knowledge and symbol interpretation (Abrahamsson and Johansson Citation2006; Abrahamsson, Johansson, and Johansson Citation2009). This exacerbates already existing problems of lacking attractiveness, as people with these skills may be less inclined to work for the industry.

The mining industry is technocentric and looks toward technology to solve these problems. Hartman and Mutmansky (Citation2002) saw advances in technology as an opportunity to improve the health and safety, and thus the public image, of the industry. Albanese and McGagh (Citation2011) argued that automation would solve the industry-wide problem of maintaining a qualified workforce at remote locations; younger people do not want to leave the cities, in which case remote-control technology is suitable, or technology itself might attract them. PwC (Citation2012) suggested mining companies should take advantage of new technologies to create more attractive working conditions. And Lever (Citation2011) argued that the lack of operators is a major driver for automation in general.

But increased technological sophistication in turn further increases the demands on the workforce. At the same time, mining companies are adaptors rather than innovators of technology (Bartos Citation2007). Thus they must rely on equipment providers for new technology (Hood Citation2004). Because mining companies still make active decisions on which technology to get, an analysis of the industry also allows for an analysis of the different positions of the different actors suggested by the present conceptualisation. Here Horberry (Citation2014) suggested that mining equipment, more than that of other industries, evolves in increments throughout the design process. Or rather that the context that the technology is design for evolves during this process, so that it is not clear which context the equipment needs to be adapted for (cf. Goodman and Garber Citation1988). Being an extreme case in this sense, it allows for clearer illumination of the theoretical concepts (Yin Citation2014). And insights, thus, may be applicable beyond this specific context.

The empirical material comes from field studies and observations at mining companies, technology developers and equipment providers. It includes interviews with managers (e.g. work environment managers) and engineers in these organisations, and also operators at mining companies. The details of these activities have been reported elsewhere (see Joel et al. Citation2017).

The intention here is not to reach general conclusions by making claims of empirical generalisation. Rather, the intent is to make analytical and theoretical points – analytical generalisations (cf. Yin Citation2014) regarding attractive work systems and their design. Thus, the presentation of the empirical material sacrifices descriptive depth to instead focus on illustrating phenomena. The presented material is not a representative sample, but aims to provide conceptual insight – insights that allow for inference to, in this case, the design of attractive work systems in general (Siggelkow Citation2007). That is, the section presents the material so that theoretical points can be made. Context and details is therefore presented only to the extent that it is required to provide conceptual insight. Siggelkow (Citation2007) refers to this use of case studies as illustrative (for conceptual contributions). He argues that pure conceptual arguments have two shortcomings. First, constructs (the ‘individual’s view’ and so on, in this case) are hard to understand without empirical representation. So, ‘By seeing a concrete example of every construct employed in a conceptual argument, the reader has a much easier time imagining how the conceptual argument might actually be applied to one or more empirical settings’ (Siggelkow Citation2007, 22). Second, in purely conceptual arguments underlying mechanisms tend to be speculative; the argument is lent strength if a case can illustrate the operation of concepts. This also means that the appropriateness of the data cannot be judged beforehand, only after the analysis, for instance by way of seeing the extent to which the phenomena was explained (cf. Åsberg, Hummerdal, and Dekker Citation2011).

In the following two subsections, then, two technologies (battery-powered loaders and semi-autonomous chargers of explosives) from the project mentioned above is investigated in more detail. In particular, their development receives attention (decisions and reasoning that have formed their design); the issue of designing attractive work systems is one of process rather than striving for a particular design. First an introduction to the technologies are given, then a more in-depth analysis follows.

Battery-powered loaders

The mining industry increasingly wants to replace diesel-powered mining machines with electric-powered mining machine in general and battery-powered vehicles in particular (Jensen Citation2016; Moore Citation2017; Morton Citation2017; Paraszczak et al. Citation2014; Rolfe Citation2017; Schatz, Nieto, and Lvov Citation2017; Schatz et al. Citation2015). Within the industry, arguments for battery-powered mining machines describe them as making underground mining more sustainable (Paraszczak et al. Citation2014), safer (Jensen Citation2016; Rolfe Citation2017; Schatz et al. Citation2015), healthier (Morton Citation2017) and more attractive (e.g. by making mining ‘greener’; Jensen Citation2016). In other words, battery-powered mining vehicles are seen both directly and indirectly as technology that can increase work system attractiveness.

There are three main motivators for using battery-powered mining vehicles. First, compared to diesel-powered variants, battery-powered vehicles have lower emissions of harmful particles, heat and sound. Second, reducing heat and the presence of harmful gases needs less ventilation, as battery-powered vehicles have zero emissions. A significant cost for mines comes from ventilation. They can thus save money by reducing ventilation. Third, reduced sound, heat and exposure to harmful particles means a better working environment for the operator. Some also argue that battery-powered machines in their capacity of being battery-powered vehicles are attractive because such vehicles are becoming more popular in society in general.

These motives are present in the current use of the investigated battery-powered mining vehicles. The mining vehicle developer in this study argued that battery-powered vehicle usage is either due to mines being so deep that heat, generated by diesel-powered vehicles and the bedrock, is too much for the ventilation system to handle. Mines then have to use battery-powered vehicles to be able to provide a decent work environment for their operators. Usage is also due to mines being located at such heights that diesel engines cannot operate optimally (oxygen content in the air is too low). In other words, technical challenges drive current usage. But the technology developer in this study also pointed to economic incentives: increasing diesel costs will make battery-power a more economic alternative. Arguments for an improved work environment had the character of positive side-effects; use of battery-powered vehicles were in this study never primarily motivated by improvements to the work environment.

Battery-powered loaders sold by the technology developer so far have been windowless. The reasoning seems to be that isolated cabins (cabins with windows that are ‘sealed’ against the external environment) exist to protect the operator from noise and harmful particles; as diesel-engines generate most of the noise and harmful particles, when battery-power replaces diesel-engines, the cabin serves no purpose in protecting the operator from this exposure. The technology developer also reported that, with no windows, operators can more easily communicate with each other. Other technology developers have acted similarly. Some deliver battery-powered loaders with no cabin at all; they argue for the improved visibility that this brings the operators (Artisan Vehicle Systems Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c). This reasoning can be problematic. To mention just one aspect, while a battery-powered loader produces a sound level of 80 dB measured from outside its cabin (for comparison, a diesel-powered loader produces a sound level of 125 dB measured from outside its cabin, and 80 dB measured from inside its cabin) this level is still too high (Reeves et al. Citation2009; McBride Citation2004).

For the operators’ perspective, some of those in this study operated diesel-powered loaders with isolated cabins. They did not consider air quality, noise or heat as pressing problems (even if air quality outside the cabins was noted as not being very good). Instead, physical ergonomics was the primary concern. When operating a loader, the operator is hurled around in the cabin due to bad surface conditions, poor suspension and limited sigh. Vibrations and poor sight leads to head turns that cause bodily strain. Some loaders had rotational chairs to decrease the need for head turns, and operators could only operate a loader for a limited time. Both measures were intended for decreasing bodily strain. Even so, the operators reported that ergonomic problems persisted.

The operators of the study did not necessarily see battery-powered machines as a more attractive alternative. For new mining machines they wanted improved cabin ergonomics; if a battery-powered loader would lead to improved cabin ergonomics, they would appear more attractive.

Jäderblom (Citation2017) conducted a small focus group with students regarding their views on switching from diesel to battery-power. Their views were positive – switching to battery-power would make this type of job more attractive. Reasons for this included the direct positive health effects for operators. But there were also concerns regarding the risk of fires and explosions. The participants drew parallels to documented accidents with electric cars and phone-battery failures that resulted in fires. They considered lithium batteries to be dangerous – everyone held that all lithium batteries would increase the risk of fire. According to the technology developer, on the other hand, the batteries do not increase the risk of fires or explosions.

Semi-autonomous chargers

The second technology is semi-autonomous chargers for explosives. Researchers and commentators (e.g. Albanese and McGagh Citation2011; Hartman and Mutmansky Citation2002; Lever Citation2011; PwC Citation2012) have argued for further automation to increase the attractiveness of the mining industry. Mining companies recognise reduced accidents as a way to increase workplace attractiveness (see Ranängen and Lindman Citation2017). Mining companies in turn pursue increased automation with the motivation that it increases safety. (There is a general discourse in the mining industry of improving safety by moving operators away from the dangerous operating areas. This is always accomplished, at least in part, with automation.) In this sense, mining companies use automation to increase workplace attractiveness, with some commenters (e.g. Albanese and McGagh Citation2011) suggesting that automation technologies themselves might be attractive to a younger generation of workers.

Thus for attractiveness, three arguments motivate automating work: it decreases strenuous tasks, improves safety by decreasing dangerous tasks or moving the operator to a safer environment, and the automated technology is itself an attractive factor. The first and second motivations were explicitly expressed for the semi-autonomous charger in this study.

The automated solution in question uses an industrial robot together with a vision system to scan the mine face and automatically insert a hose which charges drill holes with explosives. A vehicle transports and positions the system. The operator will handle an initiation procedure and then monitor the process. Initially, the operator would have to do this from close-by the machine (e.g. in a cabin mounted on the machine). In a longer-term perspective, the intention is for the operator to conduct these operations from a control room.

According to the developer of the automated solution, 40% of all accidents involving rock fall occur when charging. To the extent that an automated solution moves the operator away from areas that are prone to rock fall, the risk will decrease. This potentially increases attractiveness.

The work of the charging operators in this study was largely manual. It involved charging a mine face by filling drill holes with explosives. They reported that this, due to heavy and repetitive tasks, causes fatigue as well as pain in the back, shoulders and neck. To prevent this the mines had limited the number of faces that an operator can charge during a shift. Still the problems persisted. Lessening the physical burden could thus increase attractiveness.

But while strenuous, the work of a charging operator involves physical activity – they walk and move plenty during a shift. This ability (i.e. the manual tasks) disappear when automating. The operators of the study held that the ability to move around during a shift was a positive aspect of their work – the removal of these positive aspects of the manual labour would be negative. Moreover, the charger operators worked in teams of two in some cases. An automated solution would only require one operator, which the operators viewed as negative. At the same time, charging operators are not as exposed to noise and poor air as much as others, in different mine operations (current charging machines tend to run on electricity when charging drill holes). But to the extent that the mining environment in general is noisy and of a lower air quality etc., charging operators are exposed, especially as they do not work from cabins.

Illustrating the extended conceptualisation

The analysis will start by clarifying the ‘status’ of the different constructs of the model: the location of individuals and actors, their views and preferences, and the properties of the work system. The individual’s preference is variable and depends on the specific individual. Still, certain ‘configurations’ of preferences should be more common than others among operators in the mining industry. At least certain factors should feature more prominently. That is, if the work systems of the mining industry exhibits certain properties, then these must match certain preferences of the individuals who work there. For the individual’s view, among those located in the work system – the operators – there must be correspondence between preferences and properties of the work system (views and properties are more or less the same in the internal perspective), even if not all factors correspond.

The situation is different for individuals in the external environment. Here the conceptualisation distinguishes between ‘individuals’ and ‘actors’; they have, for example, different stakes in the issue. Individuals have a stake in the work system constituting a future place of work. Actors’ interest in the work system is as part of their job (or perhaps a general interest).

To the extent that ‘operator’ (‘loader’, ‘charger’ etc.) is a job that is unattractive because recruiting for these positions is difficult, there is a mismatch between individual preferences and views of the job. This is the external view. Note that preferences might actually correspond to actual properties, but that the view is different. Next, then, the analysis takes an interest in these differences in constructs and variation between individuals (including actors).

Looking at the battery-powered loaders, two ‘attractiveness factors’ – or underlying mechanics of changed attractiveness – are salient. As an example of the first factor, consider the change to technology that is more environmentally friendly. Here the preferences of individuals is, (mining) work should not pollute. By changing from diesel to battery-powered vehicles – i.e. changing actual properties – the hope is that the view of the industry will change as well (see Jensen Citation2016). The implicit ‘ordering’ of factors in this reasoning can be problematic. Considering the immense impact a mine can have on the environment, the use of more environmental friendly transports might be a moot point. That is, there might be other changes that have to be enacted before the use of battery-powered vehicles becomes a tipping point for considering mining work attractive or not.

Second, battery-powered loaders improve the work environment due to decreased emission of harmful particles, sound and heat. The aim here is to change the actual properties of the work system: internally to consider internal individuals and externally to change the view of the job. But the issue is the extent to which these changes correspond to actual preferences of individuals. Two problems arise here. One, technology (or its implementation) does not produce unequivocally positive changes. And two, the question, ‘who is to find the work system more attractive?’

On the first problem, removing the cabin can have positive effects such as easier communication, better sight, even making the vehicle cheaper to produce. But there are also negative effects. The question is if the positives outweigh the negatives, if the prioritisation is correct. But with the loader operators, other issues may weigh heavier, such as cabin ergonomics. And technological development is asymmetrical in mining (e.g. Abrahamsson and Johansson Citation2006). A diesel-powered vehicles might operate next to battery-powered variants. While battery-powered vehicles do not contribute to harmful exposure, other machines might. This then is an issue of preferences and views of the developers (i.e. actors); one explanation is that the technology developer considers the purpose of an isolated cabin to be to protect the operator from noise and harmful particles. Thus the cabin is no longer needed if one of the main sources of these hazards is removed. Alternatively, the technology developer might recognise that the decreased exposure in itself is not enough to motivate removing the isolated cabin. But with decreased exposure, the advantages (easier communication, better sight) might be seen as outweighing the negatives. Some developers of battery-powered machines note the improved sight due to having no cabin (e.g. Artisan Vehicle Systems Citation2017b). And impaired sight is a problem in mining (Simpson, Horberry, and Joy Citation2009). (There are some accounts of operators considering windows problematic because they quickly get dirty. Having no windows solves this problem. But if the environment is so dusty that windows impair sight, is it healthy to be exposed to that environment?)

This issue also surfaces with semi-autonomous chargers – i.e. preferences and views of different groups that differ without there being awareness of this. The technology developer might see strenuous labour and assume then that all aspects of this work is negative. But while some factors – those that relate to strenuous aspect of work, for instance – certainly are negative, this does not mean that the work system as a whole is unattractive. Alternatively, the technology developer might recognise this but make the judgement that the improvements that the new technology implies make it worth removing other positive aspects of the work. Again, this is a question of making a different rankings of factors.

Differing views also feature in the external environment. The workshop with students (Jäderblom Citation2017) suggests that the views of the work system might be as important as the actual properties of the work system. In this case, the views of individuals in the external environment are different from actual properties of the work system. This is expected to a certain extent. But it also illustrates that actual properties of the work system do not matter if they are not ‘communicated’. As long as the perception is that batteries increase the risk of fire, and this has an effect on the way individuals act, it does not matter if batteries increase such risks or not. Likely, this is the case in other situations as well – and is especially problematic when external views are of negative properties as positive.

A lot of this relates to communication and information/understanding of preferences, views and properties. Designers, for instance, need to be aware of individuals preferences and views; even if properties and preferences match, views might not. This can have important bearing on the design procedure. As a final example of this, diesel-powered mining machines have competed by improving working conditions through cleaner engines, cleaner fuel and air-conditioned cabins – all preferred by the operator (Morton Citation2017). Battery-powered loaders compete in output, capacity, energy savings and so on. This risks taking focus away from issues contributing to attractive workplaces (e.g. operator ergonomics). It can lead to battery-powered loaders sold windowless and without proper cabins. This outcome seems particularly probable if battery-powered machines are seen as cleaner and safer solely on the basis of being battery-powered. Here, several different views and preferences coalesce; the role of the designer is to ensure that from the resulting amalgamation attractive properties can arise.

Conclusions

This article has argued that the field of ergonomics should include the topic of workplace attractiveness. The implication of the analysis so far is that designing attractive work systems necessitates a user-centric approach with a widened scope. User-centric design recognises that design must include all users, including those implicated in maintenance and decommissioning. Designing attractive work must go one step further, to concerns those who are not users, specifically because they may have fallen outside the scope of a user-centric approach. So, resultant designs must speak to and be suitable for those who currently would not consider themselves potential users. It also means sensitivity to the larger society, the external environment, in general; the image of an industry or workplace can create norms that dissuade people who in fact may find that work attractive.

Seeking guidance in creating attractive work must expand beyond current employees. Focusing only on current employees almost by definition overlooks exactly those who an organisation might want to attract. Had the current employees of the mining industry been asked, ‘What do you consider attractive about your work?’, and the answers to these questions taken to be the basis for how to make mining work more attractive, one would likely end up with work that reinforces unattractive aspects.

Moreover, attractiveness is generally thought of as preferences of applicants and employees. But preferences of the designers of the work systems (including technology developers) are also crucial. Their thoughts (preferences) influence design decisions. For instance, how trade-offs should be made, which risks to be preferred over others, how ‘good’ or ‘bad’ the environment is and what should therefore be done about it. Like other individuals in the conceptualisation, designers (actors) do not make decisions about the work system based on its actual properties but rather on their view of them. Views of technology developers and operators differ. Or rather, while knowledge about the factors might be similar, preferences for them – their relative importance – differ. For instance, where a technology developer might prioritise improving air quality, an operator (though probably not against this) would prefer an improved cabin ergonomics.

There is similarly uncertainty about not only which factors are attractive but also which jobs are. Views are not enough to judge ‘objective’ properties, because the views could be misinformed. This means that a work system that is unable to attract a workforce does not necessarily need to change. The work system might align with preferences, and communication surrounding it might have to change. Consider the workshop, for instance, in which students noted a negative factor that arguably did not exist.

Issues of resistance and ‘wishes’ for unsustainable practices (e.g. piece-rate pay) relate to this as well. The notion of attractive work goes beyond designing merely in accordance to preferences and views. The mining industry in particular is a good example of this. For instance, Abrahamsson and Johansson (Citation2006) reported on the design of the remote controllers for semi-automated loaders. Due to wishes of the (male) workforce, they featured large joysticks that mimicked those of the actual loaders. Abrahamsson and Johansson (Citation2006) connected this to operators wanting to give the technology clear ‘masculine’ connotations, as a way of resisting feminisation by technology. Later, however, much smaller joysticks replaced the initial designs; the operators had found that this eased operation.

This reasoning extends to related areas such as technology acceptance. On this issue, specifically for mining, Lynas and Horberry (Citation2011, 75) have noted that

Positive adaptation occurs when a new technology brings about a positive change in operator behaviour … whilst being acceptable and well liked by the operators. Negative adaptation may make the operators engage in more risky behaviours. Technologies that are not accepted by operators are less likely to be used properly and are more likely to be sabotaged or misused; thus any inherent potential for increasing safety or efficiency may not be fully achieved.

Attractiveness adds to this issue that, if one considers that technology can outlast generations of workers, then technology must be widely accepted. And this connects to larger issues still. Bainbridge (Citation1983) highlighted the risks of making assumptions about design that preclude the consideration of the operator. If the fact that highly automated systems still need operators (to, in Bainbridge’s words, handle the tasks which the designer cannot think of how to automate) receives no attention, operators risks being left with mundane tasks and in the role of passive observer. Still the operator is expected to intervene when the system is not performing as expected. The notion of attractive work recognises that negative effects can result even if the operator is properly considered – the system might not be designed for the next generation of worker. In another aspect, an analysis by Sanda et al. (Citation2014) suggested that miners’ successful performance of mining activities may depend on openness. Here, increased attractiveness could also help system performance beyond providing resources, i.e. by fostering (an exposure that requires) an openness.

The issue of designing attractive work systems must receive proper attention in the future. And the field of ergonomics must take an increased interest in it. But the issues also requires more research. Hopefully, this article will have given an indication where future efforts should be focused.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interests was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Joel Lööw

Joel Lo¨o¨w is a PhD student in Human Work Science at Luleå University of Technology, Sweden. He has an MSc in Industrial Design Engineering with a specialisation in production design. His research interests center on issues of the work environment and technology in the mining industry, with a special focus on how these issues can be managed with respect to social concerns. He has experience working in the EU project, Innovative Technologies and Concepts for the Intelligent Deep Mine of the Future (I2Mine), and is currently involved in a mine-accident prevention research project and in the Attractive Workplaces work packages of the EU-project, Sustainable Intelligent Mining Systems (SIMS). Lo¨o¨w is involved in courses on workplace analysis, industrial production environment, production development, and organisational change management for M.Sc. engineering students. He teaches the subject of health and safety to mining engineering students. Lo¨o¨w has published on the subjects of mining, work environment, technology, and work organisation.

References

- Abrahamsson, Lena. 2002. “Restoring the Order: Gender Segregation as an Obstacle to Organisational Development.” Applied Ergonomics 33 (6): 549–557. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(02)00043-1.

- Abrahamsson, Lena, Bo Johansson, and Jan Johansson. 2009. “Future of Metal Mining: Sixteen Predictions.” International Journal of Mining and Mineral Engineering 1 (3): 304–312. doi:10.1504/IJMME.2009.027259.

- Abrahamsson, Lena, and Jan Johansson. 2006. “From Grounded Skills to Sky Qualifications: A Study of Workers Creating and Recreating Qualifications, Identity and Gender at an Underground Iron Ore Mine in Sweden.” Journal of Industrial Relations 48 (5): 657–676. doi:10.1177/0022185606070110.

- Acker, Joan. 2006. “Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations.” Gender & Society 20 (4): 441–464. doi:10.1177/0891243206289499.

- Albanese, Tom, and John McGagh. 2011. “Future Trends in Mining.” In SME Mining Engineering Handbook, edited by P. Darling, 3rd ed., Vol. 1, 21–36. Englewood, CO: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration.

- Artisan Vehicle Systems. 2017a. “A4 - Artisan Vehicles.”http://www.artisanvehicles.com/a4/.

- Artisan Vehicle Systems. 2017b. “A4 Statistics Sheet.”

- Artisan Vehicle Systems. 2017c. “A4 Technical Specification.”

- Åsberg, Rodney, Daniel Hummerdal, and Sidney Dekker. 2011. “There Are No Qualitative Methods – Nor Quantitative for That Matter: The Misleading Rhetoric of the Qualitative–Quantitative Argument.” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 12 (5): 408–415. doi:10.1080/1464536X.2011.559292.

- Åteg, Mattias, and Ann Hedlund. 2011. “Researching Attractive Work: Analyzing a Model of Attractive Work Using Theories on Applicant Attraction, Retention and Commitment.” Arbetsliv i Omvandling (2): 2011.

- Åteg, Mattias, Ann Hedlund, and Bengt Pontén. 2004. “Attraktivt Arbete - Från Anställdas Uttalanden till Skapandet Av En Modell.” Arbetsliv i Omvandling (1).

- Bainbridge, Lisanne. 1983. “Ironies of Automation.” Automatica 19 (6): 775–779. doi:10.1016/0005-1098(83)90046-8.

- Barnow, Burt S., John, Trutko, and Jaclyn Schede Piatak. 2013. Occupational Labor Shortages: Concepts, Causes, Consequences, and Cures. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute.

- Bartos, Paul J. 2007. “Is Mining a High-Tech Industry? Investigations into Innovation and Productivity Advance.” Resources Policy 32 (4): 149–158. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2007.07.001.

- Biswas, Urmi Nanda, Karin, Allard, Anders Pousett, and Annika Härenstam. 2017. Understanding Attractive Work in a Globalized World: Studies from India and Sweden. Singapore: Springer.

- Blauner, Robert. 1964. Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry. University of Chicago Press.

- Carayon, Pascale, Peter Hancock, Nancy Leveson, Ian Noy, Laerte Sznelwar, and Geert van Hootegem. 2015. “Advancing a Sociotechnical Systems Approach to Workplace Safety – Developing the Conceptual Framework.” Ergonomics 58 (4): 548–564. doi:10.1080/00140139.2015.1015623.

- Carayon, Pascale, and Michael J. Smith. 2000. “Work Organization and Ergonomics.” Applied Ergonomics 31 (6): 649–662. doi:10.1016/S0003-6870(00)00040-5.

- Dembe, Allard E., Jeffery B. Erickson, Rachel G. Delbos, and Steven M. Banks. 2005. “The Impact of Overtime and Long Work Hours on Occupational Injuries and Illnesses: New Evidence from the United States.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 62 (9): 588–597. doi:10.1136/oem.2004.016667.

- Ehrhart, Karen Holcombe, and Jonathan C. Ziegert. 2005. “Why Are Individuals Attracted to Organizations?” Journal of Management 31 (6): 901–919. doi:10.1177/0149206305279759.

- Goodman, Paul S., and Steven Garber. 1988. “Absenteeism and Accidents in a Dangerous Environment: Empirical Analysis of Underground Coal Mines.” Journal of Applied Psychology 73 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.73.1.81.

- Harrington, J. Malcolm. 2001. “Health Effects of Shift Work and Extended Hours of Work.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1136/oem.58.1.68.

- Hartman, Howard L., and Jan M. Mutmansky. 2002. Introductory Mining Engineering, Vol. 2. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Hebblewhite, Bruce. 2008. “Education and Training for the International Mining Industry–Future Challenges and Opportunities.” Paper presented at the First International Future Mining Conference.

- Hedlund, Ann. 2007. “Attraktivitetens Dynamik: Studier Av Förändringar i Arbetets Attraktivitet.” PhD diss., Royal Institute of Technology. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kth:diva-4401.

- Hedlund, Ann, Ing-Marie Andersson, and Gunnar Rosén. 2010. “Är Dagens Arbeten Attraktiva? Värderingar Hos 1 440 Anställda.” Arbetsmarknad & Arbetsliv 16 (4): 31–44.

- Herzberg, Frederick. 1968. “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees?” Harvard Business Review.

- Hood, Michael. 2004. “Advances in Hard Rock Mining Technology.” Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Mineral Economics and Management Society, 13th Annual Conference, 21–23.

- Horberry, Tim. 2014. “Better Integration of Human Factors Considerations within Safety in Design.” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 15 (3): 293–304. doi:10.1080/1463922X.2012.727108.

- International Ergonomics Association. 2017. “Definition and Domains of Ergonomics.”http://www.iea.cc/whats/.

- Jäderblom, Niklas. 2017. “From Diesel to Battery Power in Underground Mines: A Pilot Study of Diesel Free LHDs.” Master’s thesis, Luleå University of Technology.

- Jensen, Sara. 2016. “A Matter of Survival.”OEM Off-Highway, 9–13. https://issuu.com/oemoff-highway9/docs/ooh0916.

- Joel Lööw, Camilla Grane, Niklas Jäderblom, Jonatan Lundgren, Jan Johansson. 2017. A baseline study for each technology project. Report of the Sustainable Intelligent Mining Systems project 9–13. Luleå: Luleå University of Technology.

- Johansson, Bo, Jan Johansson, and Lena Abrahamsson. 2010. “Attractive Workplaces in the Mine of the Future: 26 Statements.” International Journal of Mining and Mineral Engineering 2 (3): 239–252. doi:10.1504/IJMME.2010.037626.

- Johansson, Jan, and Lena Abrahamsson. 2009. “The Good Work – A Swedish Trade Union Vision in the Shadow of Lean Production.” Applied Ergonomics 40 (4): 775–780. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2008.08.001.

- Karasek, Robert A., and Thores Theorell. 1990. Healthy Work. New York:Basic Book.

- Lee, G. Aubrey. 2011. “Management, Employee Relations, and Training.” In SME Mining Engineering Handbook, edited by P. Darling, 3rd ed. Vol. 1, 317–330. Englewood, CO: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration.

- Lever, Paul. 2011. “Automation and Robotics.” In SME Mining Engineering Handbook, edited by P. Darling, 3rd ed., Vol. 1, 805–827. Englewood, CO: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration.

- Leveson, Nancy. 2011. Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety. Engineering Systems. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Lööw, Joel, Bo Johansson, Eira Andersson, and Jan Johansson. 2018. Designing Ergonomic, Safe, and Attractive Mining Workplaces. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Lynas, Danellie, and Tim Horberry. 2011. “Human Factor Issues with Automated Mining Equipment.” The Ergonomics Open Journal 4 (1): 74–80. doi:10.2174/1875934301104010074.

- Manpower Group. 2018. Solving the Talent Shortage: Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge. Talent Shortage Survey. Manpower Group.

- Mayo, Elton. 1945. The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization. Boston: Harvard University.

- McBride, David I. 2004. “Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Hearing Conservation in Mining.” Occupational Medicine 54 (5): 290–296. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqh075.

- Moore, Paul. 2017. “E-Dumper All Electric Truck Becoming a Reality in Switzerland.” IM Mining.

- Morton, Jesse. 2017. “More Battery-Powered Options for LHDs.” Engineering and Mining Journal 218 (1): 36–40.

- Mumford, Enid. 2006. “The Story of Socio-Technical Design: Reflections on Its Successes, Failures and Potential.” Information Systems Journal 16 (4): 317–342. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2575.2006.00221.x.

- Oldroy, G. C. 2015. “Meeting Mineral Resources and Mine Development Challenges.” Paper presented at the Aachen Fifth International Mining Symposia, Mineral Resources and Mine Development. Aachen.

- Paraszczak, Jacek, Erik Svedlund, Kostas Fytas, and Marcel Laflamme. 2014. “Electrification of Loaders and Trucks – a Step towards More Sustainable Underground Mining.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality, Cordoba.

- PwC. 2012. Mind the Gap: Solving the Skills Shortages in Resources. PwC.

- Ranängen, Helena, and Åsa Lindman. 2017. “A Path towards Sustainability for the Nordic Mining Industry.” Journal of Cleaner Production 151: 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.047.

- Rasmussen, Jens. 1997. “Risk Management in a Dynamic Society: A Modelling Problem.” Safety Science 27 (2–3): 183–213. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(97)00052-0.

- Reeves, Efrem R., Robert F. Randolph, David S. Yantek, and J. Shawn Peterson. 2009. Noise Control in Underground Metal Mining. Pittsburgh: The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- Rolfe, Kelsey. 2017. “Caterpillar Announces New Proof of Concept Battery-Powered LHD.” CIM Magazine.

- Salmenhaara, Perttu. 2009. “Long-Term Labour Shortage. The Economic Impact of Population Transition and Post-Industrialism on the OECD Countries: The Nordic Case.” Finish Yearbook of Population Research 44: 123–136. https://journal.fi/fypr/article/view/45049.

- Sanda, Mohammed-Aminu, Jan Johansson, Bo Johansson, and Lena Abrahamsson. 2014. “Using Systemic Structural Activity Approach in Identifying Strategies Enhancing Human Performance in Mining Production Drilling Activity.” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 15 (3): 262–282. doi:10.1080/1463922X.2012.705916.

- Schatz, R. Schatz, Antonio Nieto, Cihan Dogruoz, and Serguei N. Lvov. 2015. “Using Modern Battery Systems in Light Duty Mining Vehicles.” Journal International Journal of Mining, Reclamation and Environment 29 (4): 243–265. doi:10.1080/17480930.2013.866797.

- Schatz, R. S., A. Nieto, and S. N. Lvov. 2017. “Long-Term Economic Sensitivity Analysis of Light Duty Underground Mining Vehicles by Power Source.” International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 27 (3): 567–571. doi:10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.03.016.

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj. 2007. “Persuasion with Case Studies.”Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 20–24. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160882.

- Simpson, Geoff, Tim Horberry, and Jim Joy. 2009. Understanding Human Error in Mine Safety. Simpson: Ashgate.

- Turisova, Renata, and Juraj Sinay. 2016. “Ergonomics versus Product Attractiveness.” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science 18 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/1463922X.2015.1126382.

- Yin, Robert. 2014. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage.