ABSTRACT

Although once placed solely in deaf schools, a growing number of deaf students in Sweden are now enrolling in mainstream schools. In order to maintain a functional educational environment for these students, municipalities are required to provide a variety of supporting resources, e.g. technological equipment and specialized personnel. However, the functions of these resources and how these relate to deaf students’ learning is currently unknown. Thus, the present study examines public school resources, including the function of a profession called a hörselpedagog (HP, a kind of pedagogue that is responsible for hard-of-hearing students). In particular, the HPs’ perspectives on the functioning and learning of deaf students in public schools were examined. Data were collected via (i) two questionnaires: one quantitative (n = 290) and one qualitative (n = 26), and (ii) in-depth interviews (n = 9). These show that the resources provided to deaf children and their efficacy are highly varied across the country, which holds implications for the language situations and learning of deaf students.

Introduction

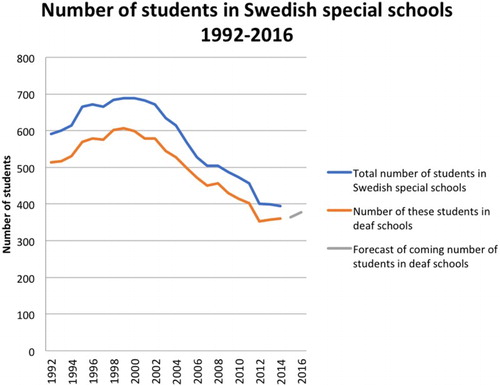

Since at least the mid-twentieth century and continuing today, a great number of technological innovations have impacted deaf education in Sweden in several ways. Enrolled solely in deaf schoolsFootnote1 at one time, deaf students began being placed in other school settings in increasing numbers from roughly the 1950s onwards, following the development and spread of hearing aids. Consequently, deaf students have been divided in two sub-groups: deaf students (who primarily communicate via Swedish Sign Language) and hard-of-hearing students (who primarily rely on hearing aids and communicate via spoken Swedish). While most deaf students have continued to attend deaf schools where sign bilingual education is offered, most hard-of-hearing students instead get their schooling in mainstream settings. During the 1990s, cochlear implants (henceforth CIs) became available as medical intervention to deaf children, and from 2000, most deaf newborns received these implants. As a consequence, there has been a steep increase in the number of deaf and hard-of-hearing (henceforth, DHH) students in mainstream schools, while at the same time the number of students in deaf schools has dropped (see ).Footnote2

At present we lack knowledge about what support, preparedness and understanding Swedish municipalities have for providing equal education to DHH students in mainstream settings. Hence, in light of changing patterns in the school placement of DHH students, there is an urgent need to newly investigate the education of DHH students and appraise the extent to which they receive the support and resources that are most in line with their particular aptitudes for learning. This study therefore aims to examine the resources provided to DHH students in mainstream schools by different municipalities around the country. We investigate how municipalities exercise responsibility for these students and what kind of knowledge they have regarding students with hearing loss per se. In particular, we focus on a profession referred to as hörselpedagog Footnote3 (‘hearing pedagogue’; henceforth, HP) in an effort to assess their importance in DHH students’ schooling. An HP is employed by a municipality in order to support mainstream schools that have DHH students enrolled in their activities, but there is no common official definition of what an HP is or what he or she is required to do. In this article, we therefore examine more closely the work of HPs and their role in the schooling of DHH students, and what opportunities and barriers they report on concerning the participation of these students in mainstream education. Parallel to this, we are also interested in language issues, because sign bilingual education is not offered in these settings. Specifically, we explore what access DHH students have to Swedish Sign Language (SSL) and what knowledge teachers have regarding language issues for DHH students.

Schooling for DHH students

Unlike Sweden’s five deaf schools, which are all under governmental authorization, mainstream schools are controlled by 290 municipalities around the country. All schools, regardless of whether they are authorized by the government or by municipalities, are required to follow the Swedish Education Act and curricula.Footnote4 In the section below, we provide policy background on municipalities’ responsibilities to DHH students, attend specifically to some directives concerning SSL that apply not only to deaf schools but equally to municipalities, and discuss findings from previous studies in mainstream settings.

Directions for supporting DHH students in mainstream schools

The Swedish Education Act stipulates that municipalities are responsible for allocating resources and organizing schooling. They also ensure that education complies with national laws and regulations, including the curricula. Municipalities are thus responsible for their mainstream schools at an overarching level to ensure that all students have access to the resources that are necessary for their schooling. Furthermore, the Education Act specifies that the principals of schools are responsible for the quality of education and performance in each school (SFS Citation2010:Citation800, chapter 2). This implies that they are responsible for organizing teaching in such a way that all students can achieve their educational goals. In addition, the Education Act stipulates that all students are given the opportunity to develop according to their abilities (SFS Citation2010:Citation800, chapter 1, 4§ and chapter 3, 3§) and that the schools strive to compensate students for differences in the opportunities they are provided through education (SFS Citation2010:Citation800, chapter 1, 4§ and 9§). This means that students who have disabilities that make it difficult for them to achieve their educational goals are entitled to receive support from the school and that teachers must adapt their teaching in order to help these students. Furthermore, students who find it easy to reach their goals have the right to further progression through guidance and encouragement. In sum, the official policy demands that municipalities, principals and teachers carry special responsibilities for students with hearing loss in their schools at various levels. However, it is not clear what relevant knowledge and skills exist in municipalities and among school staff members, nor is it clear where staff can turn to for support in this regard. The present study therefore seeks to locate specifics regarding the challenges faced in educating DHH students through Swedish mainstream education, aiming in particular to shed light on what needs and difficulties exist in mainstream schools for DHH students.

Previous studies on DHH students in mainstream schools

Only a few previous studies have focused on DHH students in mainstream schools in Sweden, and most of them were conducted in the 1990s or early 2000s (see Tvingstedt Citation1993, Bagga-Gupta Citation1999, Heiling Citation1999, Brunnberg Citation2003, Holmström Citation2013). Heiling (Citation1999) shows that classroom hearing technologies are very important for hard-of-hearing students in teaching, but despite the presence of such technologies, students cannot fully participate in classroom communication. Additionally, the partial and variable knowledge teachers possess with respect to hearing loss and their often particular use of hearing technologies often further confound this situation. Holmström’s (Citation2013) study of interaction in two mainstream classrooms, both of which included one child with CIs, revealed that while mainstream classrooms are often equipped with many hearing technologies, classroom interaction, rather than DHH students’ needs, generally frames how these technologies are used. Holmström thus found that students with CIs are not fully involved in classroom interaction and that visual communication is situationally subordinated to oral communication. She argues that students with CIs generally thus have a more peripheral identity position when compared to their hearing classmates and that they are sometimes marginalized. Similar results were also presented by Bagga-Gupta (Citation1999), who examined interaction during class breaks and found that hard-of-hearing students in mainstream setting had a marginalized position compared to hearing students. Also Tvingstedt (Citation1993) found such marginalized positions of identity being held by hard-of-hearing students in mainstream school settings predating cochlear implantation. The students in her study themselves reported that they could not participate in social interactions in the same way as hearing classmates. Findings from present research in Swedish schools thus suggest that cochlear implantation does not self-evidently lead to greater educational participation or inclusion than hearing aids did previously, at least as far as classroom communication and participation are concerned.

More recently, a government reportFootnote5 by Coniavitis Gellerstedt and Bjarnason (Citation2015), based on a study of 85 hard-of-hearing students in mainstream schools in Stockholm, was published. This study notes that a satisfactorily working hearing technology is of great importance for DHH students’ educational access. In the report, factors related to a successful hearing technology were described in terms of sound environment, hearing aids and teaching approach. These factors were deemed critical for the degree of educational access that hard-of-hearing students sought in their schools and were indeed found to influence the participation of these students. The study’s results also showed, however, that the sound environment in school settings did not meet the society’s minimum requirements for noise levels and that hearing aids presented major shortcomings regarding technical features. In only 41% of the cases did the hearing aids work well throughout the lesson. In addition, the students often complained about sound quality, but, despite this, used the available technologies to a great extent. Coniavitis Gellerstedt and Bjarnason consider this as an expression of hearing technology being necessary for the students. Particularly relevant to the current study is that their results indicate the support given to teachers and students also being of great importance. The authors report that HPs play an important role, but that this profession is lacking in many municipalities. For example, they found that only 17 of the 85 students in their study had support from an HP.

Finally, there are international studies of deaf students in mainstream settings that show that these students often interact with teachers and interpreters, and to a much lesser extent with their classmates (see e.g. Ramsey Citation1997, Shaw and Jamieson Citation1997, Keating and Mirus Citation2003, Ohna Citation2005). What these studies suggest is that access issues pertaining to fluent, unimpeded classroom communication are not characteristic of hard-of-hearing students alone, but extend also to deaf students in mainstream settings, so that issues of educational access cannot logically reduce to mere questions about technologies and how they are used: educational access remains firstly a pedagogical issue. Taken together, previous research suggests that the placement of DHH students in mainstream school settings is not unproblematic and that a number of aspects should be taken into account, aspects that concern not only technology but, more fundamentally, pedagogy. While the findings to date are of importance for broadening the knowledge base from different perspectives and in relation to various organizational levels, our study aims to significantly extend this base.

Official statements concerning access to SSL in education

Of interest to this study is the access that DHH students’ have to SSL in mainstream schools. The UN ConventionFootnote6 prescribes that the states shall facilitate full and equal participation for persons with disabilities in education. This includes the responsibility to facilitate the learning of the national sign language and that DHH students should be trained in the languages, and the forms and means of communication that are most appropriate for them, with the aim of maximizing their knowledge and social development. Furthermore, the Convention provides that the states take measures to employ teachers who are qualified in sign language. It is therefore interesting to closely examine what knowledge mainstream schools have regarding SSL and what access the students have to this language (see also SOU Citation2011:Citation30). Sweden also has a Language Act (Citation2009:Citation600), which states that the mainstream society has a particular responsibility for protecting and promoting SSL. This means that DHH people, as well as others who need SSL for any reason, shall be given the opportunity to learn, develop and use it. However, it is important to clarify that the Language Act applies to people who are ‘in need of’ SSL, but how this need is to be measured, or who should do the measuring, is not made clear in the Act, which makes these kinds of formulation unclear.

The language situation of DHH students from linguistic and communicative perspectives

The language situation of the DHH population has been relatively well described in the literature with regard to signing DHH students, i.e. sign bilinguals, especially from a linguistic view. For example, there are studies describing the importance of sign language skills for acquisition of a spoken/written language (Strong and Prinz Citation2000, Chamberlain and Mayberry Citation2008, Schönström Citation2010). However, linguistic and communicative research on the DHH population that in varying degree uses spoken or/and signed language on a daily basis in terms of the communicative mode is lacking. The common description provided for the DHH population in the literature points to the fact that many DHH students struggle with language and academic achievement to various degrees (see e.g. Knoors and Marschark Citation2012).

SSL is the national sign language in Sweden, but there are also other existing sign-based communication forms in Sweden, such as sign-supported Swedish (TSS) and manual augmentative and alternative communication (TAKK). TSS is used in situations in which the perception and understanding of spoken Swedish needs to be facilitated in a visual way and is, traditionally, the communication mode used most often in the DHH field for supporting the understanding of spoken Swedish. TAKK, in turn, comes from the special needs education field, with a focus on (impaired) language development. After some decades of great interest in learning SSL, as expressed by parents and special education teachers, the spread of cochlear implantation resulted in a shift in focus in the 2000s to a greater interest in TSS/TAKK, often under the pretence that DHH children, assuming they have spoken language competence, do not need SSL, but can benefit from visual support provided through TSS/TAKK, something that some researchers have also suggested (e.g. Knoors and Marschark Citation2012). Owing to the growing number of DHH children receiving CIs, recent research has paid greater attention to spoken language outcomes from various perspectives. On the one hand, research has shown a great variability in the spoken language outcomes of implanted children (Niparko et al. Citation2010, Humphries et al. Citation2014); on the other hand, the written production of DHH groups has been described as lagging compared to that of hearing peers (Antia and Kreimeyer Citation2005) or as being second language-like (Svartholm Citation2008, Schönström Citation2014).

Method

This study is an empirical one, consisting of a survey in two main parts. In the first part, we wanted to examine to what extent municipalities in Sweden had an HP and the number of HPs in each of them. As such, a request was e-mailed to all of Sweden’s 290 municipalities, asking if they had an HP bearing responsibility for DHH children in their schools. In addition, we requested contact information for the HP (or another responsible person if the municipality had no HP). After three months, a reminder was sent to all municipalities that had not replied. All answers (n = 264) were then analyzed and compiled in tables (see and ). As the tables show, some HPs are in-house or hired. However, some of the HPs are shared between different municipalities, while some municipalities have several HPs. However, based on the answers, our analysis revealed that there are 82Footnote7 unique HPs in total around the country. After this, we proceeded with the second part of the study, which was a qualitative survey based on two sub-parts: semi-structured interviews and a questionnaire. For the semi-structured interviews, we chose to focus on HPs working in the regions of Örebro and Stockholm, because these counties have large DHH populations and provide different school forms for DHH students from pre-school up to the university level. In addition, we chose the region of Kalmar with the aim of including a region without such variation in school forms. We contacted all the HPs identified in these three regions, asking them to participate in the study through interviews about their work and experiences regarding DHH students in mainstream school settings. In total, nine HPs answered positively to our inquiry: three from the region of Örebro, four from Stockholm and two from Kalmar. As mentioned above, the interviews were semi-structured, with 12 generally formulated questions that focused on the work of the HPs, the students’ situation in school, and language and communication issues (see Appendix 1). The interviews took between 45 and 90 minutes each, and were documented with a video camera. After the interviews, the video recordings were transcribed, and some sequences were selected to undergo deeper analysis. In the analysis, the responses of the HPs were compared, and recurring issues and phenomena were noted. Because we wanted to achieve a deeper understanding of both the HPs’ work and their perceptions of DHH students’ situations, the recurrent issues and phenomena that we noted formed the basis of a second follow-up questionnaire that was sent to the remaining 73 HPs identified through the survey in the first part of this study. These HPs were contacted through email and asked to answer a further set of questions with regard to their work as HPs and about DHH students in mainstream schools. They were asked to respond to the questionnaire in written Swedish (see Appendix 2) and send the responses back to the researchers via e-mail. After two months, a reminder was sent to all HPs who had not answered. We received 26 responses to the follow-up questionnaire, and these were analyzed and compared to the results from the interviews with the aim of identifying any further themes and descriptions that seemed prevalent.

Table 1. Answers from municipalities (n = 264).

Table 2. Distribution between Sweden’s 21 counties.

Results

In this section, we will present our results in two parts. In the first part, the municipalities’ responses, actions and prevalent knowledge among staff will be reported. The second part constitutes the main focus of this study and accounts for the results of the qualitative study, i.e. the responses from the interviews and the follow-up questionnaire. As the responses from the follow-up questionnaire generally correspond with responses from the interviews, we have chosen to account for them together. Our presentation of these results focuses on three issues: (i) the work and responsibilities of HPs; (ii) the situation of DHH students in general from the perspective of the HPs; and (iii) access to SSL and other signed communication.

It should be noted that because the interviews were semi-structured, the interviewees’ answers and descriptions proceeded in different directions. It thus became necessary to code for common themes, features, actions, etc. between them. However, some statements and explanations are of particular interest and have therefore been included in the account even though few interviewees addressed them. The lower commonality of these particular themes should not necessarily, we think, be taken to mean that other interviewees’ responses contradict the beliefs suggested by these statements, nor that they did not have these experiences as well. Wherever such instances arise, we have pointed to this issue clearly in the reporting of the results.

Part I

Responses from municipalities – distribution of HPs across the country

As mentioned above, Sweden has 290 municipalities. shows that 264 of them responded to our question on whether they had an HP or another person responsible for students with hearing loss, which means the response rate was 91%. Of these, 96, or 33%, reported having access to an HP. This means that these municipalities either had one or more in-house HPs, or that they shared with or bought HP services from another municipality in their county. Of these, only 59 municipalities (20%) stated that they had in-house HPs, but of these a few reported having more than one HP.Footnote8 Therefore, we identified a total of 82 persons being employed as HPs.

The rest, 67% (168), reported not having access to an HP, but mention people of other professions as being responsible for DHH students. As illustrated in , 63 municipalities (22%) reported having a special education teacher employed who was responsible for DHH students. This does not mean, however, that this teacher necessarily had special competence concerning hearing loss; rather, it means that a person had an education with respect to disabilities in general. Several of these special education teachers were placed in central divisions in the municipalities, but they might have also worked in specific schools. The 64 municipalities (22%) that reported another person being responsible for students with hearing loss vary greatly regarding who this person is and which position he or she holds. We were able to identify 23 different titles among these, of which the school principal was the most commonly mentioned (by 18 municipalities). This is formally correct due to the Educational Act stipulations described above, but the answers do not reveal whether the principals were competent in making suitable decisions regarding individual DHH students and the support they should receive in practice, nor how much of their time is devoted to supporting DHH students. Other responsible persons who were mentioned included other school healthcare (12), support from SPSMFootnote9 (12), the rehabilitation team at the county council (8), contact person (no title, 7), speech therapist (5), vision and hearing instructor (3), etc.

The results from the responses show that there is no unified system throughout Sweden. Instead, responsibility for DHH students varies greatly between different municipalities, and the knowledge and preparedness to meet with and support students with hearing loss seem to be greater in some places than in others. To gain a more overarching view of Sweden, we divided the answers between the 21 counties, as shown in . Through a calculation in which we divided the number of municipalities with HPs in the county with its population as a whole (see the numbers in ), it appears that the three counties with the highest number of HPs in relation to population are the medium-sized counties of Kalmar, Örebro and Jönköping. As a comparison, it should be noted that two of the three counties that are placed in the bottom are Sweden’s two largest counties in terms of population: Stockholm and Västra Götaland (Gothenburg). This can have implications for the very bleak depiction of the support for hard-of-hearing students in the county of Stockholm reported by Coniavitis Gellerstedt and Bjarnason (Citation2015), which was described in the literature review above. In sum, the answers from the municipalities indicate that few of them have access to HPs or other staff with specific knowledge concerning DHH students.

Part II

The work and responsibilities of HPs

As indicated in the introduction of this article, the profession of HP has no official definition. Nor does there exist a specific academic pathway to becoming an HP, although many of the HPs included in this study have special needs education training, often with specialization in DHH students, or an educational background in hearing science or audiology. To create a clearer picture of the work and responsibilities of HPs, the respondents to the questionnaire and the interviewees were asked to describe their work and responsibilities. From their answers, some core tasks and responsibilities were identified (see ).

Table 3. The tasks and responsibilities of HPs according to the interviews and survey.

As illustrates, HPs are greatly responsible for the educational support offered to DHH students and their teachers/staff. The role of HPs is to help teachers and school staff in a range of ways, by providing advice, information and support. But it is rare that HPs work individually, i.e. one-on-one, with DHH students. Nevertheless, according to our data, it so happens that HPs do provide students with support and advice, e.g. regarding their hearing loss, strategies for keeping up with classroom instruction, how to handle psycho-social feelings, etc. Some HPs report having close contact with DHH students, while others appear to have no personal contact at all with them. The responses also show that the responsibility for hearing equipment in schools is divided between the county and the municipality. The county council is responsible for the cost and installation of hearing equipment, but the schools themselves have to modify the acoustics of the classrooms and the furniture to optimize the performance of the equipment. The role of HPs in this respect is to support the teachers in how to use technologies in their teaching practices.

One important factor in the work of HPs is that they have knowledge of the school placements of DHH students, with the aim of supporting these schools and improving their knowledge with respect to the education of DHH students. But, according to the results of the interviews and questionnaire, it is not obvious how the HPs acquire such information. In Sweden, the responsibilities of county councils include, for example, habilitation, technological aids and support to families, while the responsibilities of municipalities include, for example, school issues. This system and the rules for secrecy complicate the access of HPs to personal data needed for identifying students with hearing loss. For example, parents have to provide approval for the county council to share information about their children to outsiders. Otherwise, the information cannot be shared with HPs. However, many HPs reported obtaining such information from the county council (six of the nine interviewees, and 24 of the 26 respondents to the questionnaire) and also said that they themselves then contacted the schools to prepare for efforts and visits there (mentioned by 4 and 14 participants, respectively). It is also the case that the schools themselves discover DHH students in their schools and therefore contact the HPs (as reported by 6 and 12 of the participants, respectively).

The investigation also suggests that differences exist between the municipalities in the school types and educational levels for which the HPs are responsible. Some claimed that HPs hold responsibility for elementary schools only, while others reported them being responsible for pre-schools and/or upper secondary schools as well. Some municipalities do not allow free schools to receive support from HPs, while others do. Such differences between municipalities make it impossible to draw any firm conclusions in this regard. Additionally, a mixed picture of the municipalities throughout Sweden emerges in this respect. Thus, there appears to be little consensus in the support provided to DHH students in mainstream school settings.

The situation of DHH students in general from the perspective of HPs

The interviews and questionnaire indicate that most DHH students in schools get what the HPs consider as being generally adequate hearing equipment for use in classrooms. Several HPs reported county councils being generous and providing the students all the equipment they needed. But the kinds of technologies that are offered differ. For example, some offer FM systems, while others provide soundfield systems. Through the interviews, however, a more nuanced picture of the use of technologies emerges. The descriptions given by HPs reveal that not all teachers consistently use the technologies that are offered in their teaching practices. Compared to teachers in higher grades, teachers in lower grades are more consistent in their use of the technologies and in reminding other students to speak into the microphones. But several of the HPs reported difficulties in training teachers to make consistent use of the technologies, which they maintained the importance of doing even when the DHH student is not present.Footnote10 They also mentioned that many DHH students assume responsibility for the microphones (e.g. bringing them to classrooms if they are portable, asking teachers to use them, telling the staff that they are broken, etc.) and that students in higher grades, apprehensive about raising these concerns, instead often tell the staff that they do not need the microphones. Three HPs pointed out during the interviews that classmates of the DHH students, rather than the DHH students themselves, sometimes reminded the teacher to use the microphones, which these HPs found to be positive and helpful for DHH students.

Generally speaking, different hearing technologies are thus offered across the municipalities in support of DHH students who attend mainstream schools. Another kind of support that may be offered is a resource person who can help the students in different ways; however, according to responses to the questionnaire, DHH students rarely receive such support. This is also mentioned in the interviews: it may be possible to obtain resource persons, but it is not primarily DHH students who ultimately receive such support. Instead, it is students with special needs, or DHH students with additional difficulties, who receive the support.

Responses to the questionnaire and in interviews also reveal that the HPs consider class sizes to frequently be too large for DHH students, and that these students would benefit from smaller class sizes given the additional demands their presence makes on good classroom communication. However, schools reported having few options for reducing the number of students in classes. Conversely, several of the interviewees mentioned that the lessons often work well and that the DHH students are often able to participate in classroom communication. But, the HPs also highlighted some social aspects of everyday life in school: when the DHH students are young, they often engage in play and activities during breaks, but at more advanced ages, several of them rarely participate in social activities, and therefore some become very lonely and isolated. The HPs also reported DHH students having greater difficulty in keeping up with communication outside the classrooms, where microphones are not available, and that they are often very tired when the school day ends.

Access to SSL and other signed communication

One of the main issues investigated in this study was the access of DHH students to SSL or other forms of sign communication, such as TSS/TAKK, in mainstream schools. In both the questionnaires and the interviews, HPs were asked about the role of SSL or TSS/TAKK for DHH students, and the students’ access to such communication. However, despite the direct question related to this issue, the questionnaire responses did not result in any detailed information about sign communication. The responses to this question were instead found to be short and insufficient across all of the questionnaires. The interviewees did, however, give more detailed information regarding this issue and discussed the existence of visual communication in mainstream settings. The results of the interviews and questionnaire are illustrated through the presentation of core sentences listed in . One notable feature is that the HPs who were interviewed did not differentiate between TSS and TAKK; rather, the two forms of signed communication appear merged in their discourse about signed communication.

Table 4. SSL/TSS/TAKK in mainstream schools.

shows that, according to the descriptions provided by HPs, the access that DHH students have to SSL is generally limited. Primarily, it is in the lower grades that any form of signing exists, as it is mostly pre-school teachers who want to learn and use sign communication in any form. In this regard, it is TSS/TAKK that are the most common forms of signing. The reasons underlying the low interest seems to be varied. One reason that was discussed by the interviewees was that natural environments for signing was lacking. From a practical perspective, if the DHH students learn to sign, they have nobody in their environment to sign with, because other students and adults do not know SSL or TSS/TAKK. Six HPs reported sometimes teaching both the DHH students and their classmates some signs, but that these were not commonly used. However, five of the interviewees and one respondent to the questionnaire reported thinking it would be good for the students to learn signing, at least for their future prospects. Nevertheless, teachers and parents did not show extensive interest in signing in the classroom.

Taken together, the results indicate that DHH students in municipality schools have limited access to SSL or other forms of sign communication and, instead, must solely rely, to a great extent, on hearing technologies for the purposes of classroom interaction.

Discussion

Our results in this study have shown that access to HPs, together with hearing equipment, may be the only support DHH students receive. Among other things, the advice and support offered by HPs help school staff to provide students with the training and support they are entitled to according to the Education Act (SFS Citation2010:Citation800). School staff do not themselves possess this knowledge, and therefore HPs emerge as very important resources, both for teachers and students. Despite this fact, only 33% of all municipalities reported having access to HPs. These results are in line with the report by Coniavitis Gellerstedt and Bjarnason (Citation2015), and show that the results from their study are not specific to Stockholm County solely, but are common in several counties in Sweden. Another issue revealed by our study is that if the principals of schools officially bear ultimate responsibility for their own educational activities in accordance with the Education Act, it does not mean that they have knowledge of hearing loss per se, nor is it necessarily given that time is clearly allotted to this responsibility. Therefore, resources in the form of HPs should be understood as highly essential, and there should be an increase in their number throughout Sweden to ensure that DHH students get an education comparable to that of other students.

As illustrated by this study, the municipalities differ in several ways regarding the support that they offer DHH students and the knowledge they have regarding these students. There is, however, also a wide range of variation regarding how teaching is structured in schools, how well the classrooms are equipped, and in how teaching is practiced. With respect to schools, our investigation has also shown that HPs consider class sizes in many parts of the country too large to provide a good learning environment for DHH students. Moreover, the compilation of responses offered by HPs in the study shows that the technical equipment that the county councils provide also varies. And although it appears that the county councils are often generous when it comes to providing hearing equipment, there is no guarantee that this equipment is actually used or used well in practice, something Heiling (Citation1999) mentioned previously with regard to the late 1990s and predating widespread cochlear implantation. This problem, therefore, seems to persist in mainstream school settings today. Several HPs stated that many teachers, particularly in higher grades, forget to use these technologies or ask students whether they need to use them. This indicates that many teachers significantly lack knowledge about what it means for a student to have hearing loss and to try to follow spoken communication in the classrooms. Taken together, the opportunities for DHH students to participate in the classroom seem to hinge largely on the efforts of individual teachers. In light of these results, it is justified to question whether DHH students in mainstream schools today really receive the support they are entitled to and if teaching practices are adapted to their needs, especially in municipalities that do not have access to the specialized competence that HPs offer.

As mentioned above, the UN convention on the rights of persons with disability stipulates that member states are obligated to make it easier for people with disabilities to participate fully and equally in the classroom, and that they must facilitate the learning of national sign languages. From this perspective, the convention is also important when talking about the rights of DHH students in mainstream school settings. In the present study, we have found that the availability of SSL is almost totally non-existent for DHH students in mainstream schools. As shown in the results section, several HPs reported that the interest among school staff members in learning SSL is low and that it is usually pre-school teachers and teachers at lower grades who express the most interest in learning ‘signs’ to any extent. HPs reported most of these teachers asking to learn TSS/TAKK, which indicates a highly technological approach to visual communication in which SSL is reduced to a set of signs used as a tool for facilitating spoken communication.

As shown in the results section, several of the HPs argued that DHH students would benefit from learning SSL, but that they have no access to it nor anyone with whom to use it. Another important factor is that many DHH students are not considered to ‘need’ SSL, a perspective on language that we also mentioned above. This can, for example, be found in the Language Act (Citation2009:Citation600), which emphasizes that SSL is for those who are ‘in need’ of it. Herein lies a serious problem, as nowhere is it clarified who can determine a DHH child’s ‘need’ for SSL, nor how this need can be measured. One question that must be asked here is whether hearing adults can determine a child’s ‘need’ for SSL. We therefore suggest that a logical approach would be to instead adopt an advantage-oriented perspective, a Sign Gain perspective (Hauser and Kartheiser Citation2014), in which SSL can be seen as a possibility from which DHH children (as well as hearing people) can benefit greatly. Hauser and Kartheiser (Citation2014) argue that learning a sign language provides children with both linguistic and cognitive advantages. Their review of research on the field show that

Signers have enhanced abilities to discriminate among people’s facial features, particularly the features critical to processing linguistic information in signed language: the eyes and the mouth. Signers have greater spatial spans, generate images in their memories faster, are more skilled at rotating images in their minds, and have better discrimination between some motions than nonsigners. These are only examples; there are other areas of cognitive processing in which signers have advantages. (p. 142)

This can be related to the Education Act and the UN Convention, which emphasize that students with disabilities have the right to receive the support they need to achieve proficiency in school. This study shows that this support seems to be lacking in mainstream schools. The prerequisites and resources provided in mainstream schools can be set in relation to the vast resources that are provided in special schools or classes for DHH children, i.e. deaf schools and schools for hard-of-hearing children. In these schools, students have access to a wide range of resources, and their needs are met individually, something that could hardly be done in mainstream schools (see e.g. Coniavitis Gellerstedt Citation2008, Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten Citationn.d.).

Conclusion

The overall results from the present study draw a largely divided picture of mainstream schooling in Sweden on a variety of levels. Our study has shown considerable variation in how different municipalities support pupils with hearing loss in mainstream schools. Instead, municipalities act in different ways, even when they belong to the same county. The investigation has, among other things, also revealed that municipalities make different decisions regarding who will be held responsible for DHH students. Although this study shows the importance for schools, teachers and DHH students to have access to an HP with an in-depth knowledge of hearing issues, most municipalities in Sweden do not have access to someone in this profession. The Education Act stipulates that all students have the right to develop to the extent possible based on their conditions. In light of this study, we must question whether this objective is being met today. It may in this respect be noted that no institution or authority now exists in Sweden with an overarching responsibility for DHH students. No one has the task of ensuring that students receive the support they need in order to benefit from teaching and to ensure that they are provided a useful school environment, regardless of where in the country they are receiving their education. In addition, a national strategic view of and clear set of ambitions for the schooling of DHH students is glaringly absent. Instead, knowledge, preparedness and support vary seemingly randomly between different municipalities, schools and teachers. Even aside from raising questions about the demonstrable quality of present provisions, the findings reported in this study suggest the image of a lottery with respect to regional educational support provisioning, which is likely to impact where DHH students choose to go to school and where their families might also consequently or in anticipation choose to settle. This surely stands in contrast to the general ambitions of commonality and communality, and the equity of treatment and opportunity that both the Swedish National Education Act and the international UN Convention seek.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for comments from Rickard Jonsson, Stockholm University, Ernst Thoutenhoofd, University of Gothenburg, and anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Ingela Holmström http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8762-7118

Krister Schönström http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8579-0771

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Sweden, these schools are called ‘special schools’, but here we use the internationally common term ‘deaf school’.

2 We use the term ‘DHH’ in this study when referring to students who are schooled in mainstream settings. Generally the terms ‘deaf’ and ‘hard-of-hearing’ refer to different groups in Sweden; deaf is used for people who primarily communicate through Swedish Sign Language, while hard-of-hearing refers to people with hearing aids that primarily use spoken Swedish. However, children with CIs in Sweden are sometimes referred to as ‘hard-of-hearing’ and sometimes as ‘deaf with CIs’. However, the focus in this study is on all DHH students in mainstream settings. Children who are severely or profoundly deaf and primarily use Swedish Sign Language are still mainly enrolled in deaf schools and are not part of this particular study.

3 What this profession entails will be examined in the study, and a definition will be established in the analysis.

4 For a more detailed description of the Swedish school system, see http://www.skolverket.se/om-skolverket/andra-sprak/in-english/the-swedish-education-system.

5 This report is called HODA, in Swedish: Hörteknik och dess användning i skolan. In English: Hearing technologies and their use in schools.

6 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-24-education.html.

7 These 82 persons had a specific job title named ‘hörselpedagog’ (HP), that will be more deeply examined in the results section below. In addition, the differentiation between them and other responsible persons will be further described there.

8 These are: Borlänge (2), Göteborg (5), Halmstad (2), Hässleholm (2), Lund (2), Malmö (2), Skellefteå (3), Sundsvall (2) and Örebro (3).

9 The National Agency for Special Needs Education and School.

10 With the aim of creating a common routine in the classroom.

References

- Antia, S.D.R. and Kreimeyer, H., 2005. Written language of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in public schools. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 10 (3), 244–255. doi: 10.1093/deafed/eni026

- Bagga-Gupta, S., 1999. Tecken i kommunikation & identitet: Specialskolan & vardagsdeltagande. In: U. Sätterlund Larsson and K. Bergkvist, eds. Möte – en vänbok till Roger Säljö. Studies in Communication 39. Linköping: Linköping University, 111–139.

- Brunnberg, E., 2003. Vi bytte våra hörande skolkamrater mot döva! Förändring av hörselskadade barns identitet och självförtroende vid byte av språklig skolmiljö. Örebro Studies in Social Work no. 3. Örebro: Örebro University.

- Chamberlain, C. and Mayberry, R.I., 2008. American sign language syntactic and narrative comprehension in skilled and less skilled readers: bilingual and bimodal evidence for the linguistic basis of reading. Applied psycholinguistics, 29, 367–388. doi: 10.1017/S014271640808017X

- Coniavitis Gellerstedt, L., 2008. Om elever med hörselskada i skolan. Report. Örebro: Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten.

- Coniavitis Gellerstedt, L. and Bjarnason, S., 2015. ‘Vad var det du inte hörde?’ Hörteknik och dess användning i skolan – HODA. FoU skriftserie nr 5. Härnösand: Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten.

- Hauser, P. and Kartheister, G., 2014. Advantages of learning a signed language. In: J.J. Murray and H.L. Bauman, eds. Deaf gain: raising the stakes for human diversity. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press, 133–145.

- Heiling, K., 1999. Teknik är nödvändigt – men inte tillräckligt: en beskrivning av lärarsituationen i undervisningen av hörselskadade elever. Pedagogisk-psykologiska problem no. 659. Malmö: Malmö Högskola.

- Holmström, I., 2013. Learning by hearing? Technological framings for participation. Örebro Studies in Education 42. Örebro: Örebro University.

- Humphries, T., et al., 2014. Bilingualism: a pearl to overcome certain perils of cochlear implants. Journal of medical speech-language pathology, 21 (2), 107–125.

- Keating, E. and Mirus, G., 2003. Examining interactions across language modalities: deaf children and hearing peers at school. Anthropology & education quarterly, 34 (2), 115–135. doi: 10.1525/aeq.2003.34.2.115

- Knoors, H. and Marschark, M., 2012. Language planning for the 21st century: revisiting bilingual language policy for deaf children. Journal of deaf studies and deaf education, 17 (3), 291–305. doi: 10.1093/deafed/ens018

- Niparko, J.K., et al., 2010. Spoken language development in children following cochlear implantation. JAMA, 303 (15), 1498–1506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.451

- Ohna, S.-E., 2005. Researching classroom processes of inclusion and exclusion. European journal of special needs education, 20 (2), 167–178. doi: 10.1080/08856250500055651

- Ramsey, C.L., 1997. Deaf children in public schools. placement, context, and consequences, sociolinguistics in deaf community series, Third Volume. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Schönström, K., 2010. Tvåspråkighet hos döva skolelever. Processbarhet i svenska och narrativ struktur i svenska och svenskt teckenspråk. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Schönström, K., 2014. Visual acquisition of Swedish in deaf children. An L2 processability approach. Linguistic approaches to bilingualism, 4 (1), 61–88. doi: 10.1075/lab.4.1.03sch

- SFS 2010:800. Svensk författningssamling. Skollag. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- SFS 2009:600. Svensk författningssamling. Språklag. Stockholm: Kulturdepartementet.

- Shaw, J. and Jamieson, J., 1997. Patterns of classroom discourse in an integrated, interpreted elementary school setting. American annals of the deaf, 142 (1), 40–47. doi: 10.1353/aad.2012.0241

- SOU 2011:30. Statens offentliga utredningar. Med rätt att välja – flexibel utbildning för elever som tillhör specialskolans målgrupp. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Specialpedagogiska skolmyndigheten. n.d. Skola på elevernas villkor. Available from: www.spsm.se.

- Strong, M. and Prinz, P.M., 2000. Is American sign language skill related to english literacy? In: C. Chamberlain, J.P. Morford, and R.I. Mayberry, eds. Language acquisition by eye. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 131–141.

- Svartholm, K., 2008. The written Swedish of deaf children: a foundation for EFL. In: C.J. Kellett Bidoli and E. Ochse, eds. English in international deaf communication. Bern: Peter Lang, 211–249.

- Tvingstedt, A.-L., 1993. Sociala betingelser för hörselskadade elever i vanliga klasser. Stockholm: Almqvist och Wiksell.

Appendix 1

Semi-structured interviews with HPs

Tell us about yourself and your background.

What does it mean to work as an HP?

How do you perceive the school situation for DHH students today (i.e. regarding knowledge, skills, resources, equipment, etc.)? Has anything changed from the past?

Tell us about DHH students today and how they were before. Have they changed?

How does communication work in school for DHH students (with peers, teachers, other staff, etc.)?

What is the role of Swedish Sign Language for DHH students and their schools? Usage and needs? Are other sign systems used?

What is the role of the Swedish language for DHH students and their schools? Usage and needs?

How do you perceive the state of knowledge in school in general regarding DHH students and their education? What knowledge do you think is needed?

What are your contacts with different stakeholders in the community and with parents?

What do you think the future holds for DHH students in schools?

Summarize some of your thoughts and tell us something overarching about the situation of DHH students in school.

Is there anything else you would like to tell?

Appendix 2

Questions to HPs in municipalities

Tell us briefly about what it means to work as an HP (what is included in your work, who are you working with, etc.).

How do you learn where students with hearing loss in your municipality are placed, and how has your support for them been initiated?

What kind of support is offered for students with hearing loss in the schools in your municipality (resource person, technical aids, acoustic adjustments, reduced class sizes, etc.)? How does this support work in your view?

How does the students’ functional speech and hearing competence work in general?

Do students with hearing loss in your municipality have access to Swedish Sign Language (or other forms of ‘signing’, such as TSS, TAKK) in any way? Please describe it in more detail.

What do you know about the students’ knowledge in Swedish language? Do they achieve the goals of Swedish as a subject?

Do the teachers possess knowledge about teaching students with hearing loss in Swedish?

Is there anything that you feel is particularly positive and/or particularly problematic for students with hearing loss in your municipality?

Is there anything else you would like to share with us regarding this group of students/schools/teachers and your work with them?

Thank you for your answers.