At the annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) in Helsinki in July 2016, the founding Editor-in-Chief of Human Fertility, Professor Henry Leese of Hull York Medical School, was awarded honorary membership of the Society. A look back at the previous awardees shows that this is indeed a roll call of the ‘great and the good’, including luminaries in our field stretching back to 1985, such as Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards, Bunny Austin, Howard and Georgeanna Jones, Ryuzo Yanagimachi, Andre Van Steirteghem, Ian Wilmut and Anne McLaren, among others. As is customary on these occasions, the awardee was honoured with a short film of his career and interests, which can be seen at https://youtu.be/yAipBwYYVyQ.

Professor Leese (Henry to nearly everyone who knows him) spent most of his scientific career at the University of York. He described in the film how one day he was in the university library and on the shelves was a book on the Fallopian tube. Inside was a picture of a cross-section of a Fallopian tube which looked just like intestine. And he thought, ‘…wow this is interesting, much more interesting than the gut …!’ He worked on the Fallopian tube for around 7 or 8 years and then felt he needed to do something different scientifically, and by then had decided where he wanted to go. This was the laboratory of John Biggers at Harvard Medical School in Boston, USA. Henry turned up in Boston, whereupon Biggers said the words which changed Henry’s scientific career, indeed his life – ‘well you’re only here for a quite short period of time, about six months, so I suggest you work on early embryos.’ So Henry started working in Biggers’ lab, and then moved back to the UK and continued working happily on mouse embryos for the rest of his career.

One day in the mid-1980s, he had an unexpected phone call from Bob Edwards. In the film, Henry explains how you did not expect to be rung up by Bob, but he had done so because he had seen Henry’s paper on pyruvate and glucose uptake by mouse ova and preimplantation embryos (Leese & Barton, Citation1984). Bob asked if they could work together to study spare eggs and human IVF embryos. Henry agreed, they went ahead and it was successful, and moved from the basic profiling to look at whether the metabolism of an embryo could be measured non-invasively to predict the capacity to develop either to the blastocyst stage or to give rise to a pregnancy in an IVF cycle.

Henry started out expecting the best embryos to have the highest metabolism (i.e. to be the most active). However, the reality was not like that at all, if anything it was the other way round and those embryos that were metabolically ‘quiet’ seemed to have the best possibility of developing both in a dish and giving a pregnancy. Henry called this the ‘Quiet Embryo hypothesis’ (Leese, Citation2002). As with all hypotheses, it has been modified slightly over the years to take into account criticism and new data. Instead of considering only noisy and quiet embryos, we now look at the whole distribution of activity. Rather than just being two categories, embryo metabolism appears to obey the Goldilocks or ‘lagom’ principle, whereby ‘just enough’ metabolism is sufficient (Leese et al., Citation2016).

Henry has always felt keenly that there are real problems with human embryo culture in IVF, 8 or 10 standard media being used routinely. In the really good trials used to compare these media, no differences were found. A major embryo culture medium trial is required involving different countries, multinational and multi-centre. There is also emerging evidence that during the early stage of pregnancy, the first week right around conception, there is a window of opportunity during which environmental disturbances such as exposure to ART techniques and embryo culture media may lead to health problems in later life. The evidence is very good in animals but yet not definitive; however, many people are moving into this field (the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease) and it is becoming an interesting area of investigation (Feuer & Rinaudo, Citation2016; Leese, Citation2014).

Away from science, it is shown in the film how Henry loves to wander around art galleries and how he feels the great thing about art is being distinct from science. In the lab, scientists are looking for consensus and agreements and expect to be judged and questioned, and to justify what they say. However, in art, people can think whatever they like about a piece of music or a piece of art, and Henry sees it as a great escape or relief from some of the rigours of science.

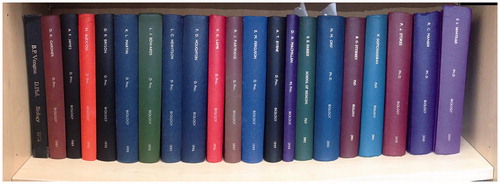

I know from Henry that one of his proudest achievements in science is his roll call of PhD students, many of whom populate our field and continue to stretch it in new directions. His most cherished scene in the film came when the camera slowly scanned his office shelves full of PhD theses (), but sadly this bit ended up on the ESHRE cutting room floor!

Figure 1. Some of the PhD, M. Phil. and D. Phil. theses supervised by Professor Henry Leese. (Photograph supplied by Dr Roger Sturmey)

On a personal note, as one of his many former students who has stayed in the field, I can only add that training and working in Henry’s lab was a truly inspiring experience. I not only learned how to do science, I also learned to want to do it and to have the intellectual curiosity to ask the right questions. I do not think it is possible to overemphasize Henry’s ‘success rate‘ in terms of the number of new PhDs who stay in the field and build their own careers. In US politics this would be known as ‘having long coat-tails’; however, I think of it as the Leese legacy. Like many former students, I continue to collaborate and write and teach with Henry and thoroughly enjoy every moment, long may it continue!

Disclosure statement

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Feuer, S., & Rinaudo, P. (2016). From embryos to adults; a DOHaD perspective on in vitro fertilisation and other assisted reproductive technologies. Healthcare, 4, 51. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4030051.

- Leese, H.J. (2002). Quiet please, do not disturb: A hypothesis of embryo metabolism and viability. Bioessays, 24, 845–849. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.10137.

- Leese, H.J. (2014). Effective nutrition from conception to adulthood. Human Fertility, 17, 252–256. doi: https://doi.org/10.3109/14647273.2014.944418.

- Leese, H.J., & Barton, A.M. (1984). Pyruvate and glucose uptake by mouse ova and preimplantation embryos. Journal of Reproduction Fertility, 72, 9–13. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0720009.

- Leese, H.J., Guerif, F., Allgar, V., Brison, D., Lundin, K., & Sturmey, R.G. (2016). Biological optimization, the Goldilocks principle, and how much is lagom in the preimplantation embryo. Molecular Reproduction and Development, Advance online publication. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.22684.