Abstract

Digital support tools, including smartphone apps, are increasingly being used alongside fertility treatments. These tools aim to harness the power of information and technology to improve care, facilitate communication and support patients through stressful treatment cycles. To warrant patient engagement, digital support tools must be perceived as useful. This review identifies and narratively analyses tools developed for fertility patients to date, discusses salient included features and evaluates user reviews. A systematic search of the app markets and electronic literature databases identified 46 digital support tools for fertility patients. The identified web-based tools focussed on psychosocial support, whereas the smartphone apps primarily have practical features, with some incorporating coping support. User feedback was collated from the Google and Apple app marketplaces and analysed using thematic analysis. Patients have high expectations of support apps, in particular the user experience. Nine published studies of web-based digital support tools were identified, but there was a complete absence of peer-reviewed studies of smartphone support apps for fertility patients. This review identifies the increasing range of available digital tools to support patients having fertility treatments and highlights the very limited evidence on which clinicians and patients can currently evaluate these tools.

Introduction

The use of digital tools throughout a patient’s fertility treatment is becoming more widespread, with use of virtual consultations, electronic consent and online peer-support forums now commonplace. Just under a decade ago, patient focussed web-based interventions in reproductive medicine were identified as a key area of development (Aarts et al., Citation2012). More recent research demonstrates that women’s health apps do not appropriately address the needs of patients struggling with infertility and are of low quality with significant inaccuracies in content (Zwingerman et al., Citation2020). The research evidence supporting mobile applications and internet-based technologies to mitigate the psychological effects of infertility is sparse (Meyers & Domar, Citation2021).

In the current decade, more widespread use of apps and other digital tools in fertility care is likely, potentially with inclusion of prognostic calculators, decision support and support aiming to reduce the psychological burden of treatment. Development of patient support tools should be a priority, as the burden of infertility and of undertaking infertility treatments is known to be significant (Cousineau & Domar, Citation2007). As the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) patient support pathway states, ‘Emotional support is important from start to finish of every patient’s experience’ and the main drivers of patient satisfaction are the ‘interest shown in you as a person’, the quality of counselling and the coordination and administration of treatment (HFEA, Citation2019). Traditional counselling support offered by clinics is often underutilised (Boivin et al., Citation1999). In other contexts, such as general anxiety disorders, digitalised versions of traditional psychological support have demonstrated significantly improved clinical outcomes in depression, anxiety, and stress (Linardon et al., Citation2019). Evidence suggests digital tools can improve medication adherence (Morawski et al., Citation2018), patient satisfaction and quality of life (Larson et al., Citation2018). It is known that fertility patients have considerable interest in peer support offered through mobile technologies (Grunberg et al., Citation2018), and further digital options for support may align with patient needs and preferences, increasing uptake. Digital tools are unlikely to replace the human interactions crucial for supportive care, but are likely to be increasingly used as an adjunct.

This review aims to identify and comprehensively summarise all digital support tools for fertility patients developed to date. It combines narrative analysis exploring the included features and costs and thematic analysis of user reviews to highlight aspects of particular value, and identify potential areas for future research.

Materials and methods

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement recommendations. The review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO, registration number 156441.

Search strategy

Digital support tools include smartphone apps, SMS-based tools and web-based apps or programs that are used directly by a patient undertaking fertility treatment to support them during this experience. We conducted a systematic search of the app market and scientific literature to identify relevant digital support tools for fertility patients that were available on the app marketplace in September 2020 or reported in a study or abstract published from 1 January 2000 to 1 October 2020. The start date was chosen to be in keeping with previous research capturing all relevant literature on apps and digital tools. The app market searches were conducted in the Google Playstore, Apple Appstore and Your Health App finder databases on 21 September 2020 with search terms including Fertility, IVF, In-vitro fertilisation, ICSI, IUI, Intrauterine insemination, Support fertility and Assisted Reproduction. The search terms were developed through an iterative improvement process, working with a healthcare librarian, to capture the most relevant results.

We searched the electronic literature databases (PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE (Ovid), Web of Knowledge, Psycinfo and Cinahl) using a syntax composed of ‘Internet’ and ‘eHealth’, ‘smartphone apps’ and their synonyms, ‘psychological distress’, ‘emotional support’ and their synonyms and combined these with ‘Infertility’, ‘IVF’ and ‘Reproductive techniques, assisted’ and their synonyms. The full syntax is shown in the on-line Supplementary Material. Secondary reference searching was performed by hand in the Web of Knowledge platform for all included articles to avoid missing relevant citations. The search was restricted to apps, tools, and studies available in English. Grey literature was searched for non-peer reviewed articles, posters and abstracts, including Google Scholar, mHealth intelligence and clinical trials databases.

Digital tools included are smartphone apps, web-based programs or SMS-based tools aimed at adult fertility patients. Fertility patients are defined as those under investigation or having treatment at a secondary or tertiary fertility centre. We excluded digital tools that were primarily menstrual trackers, aiming to prevent conception, those primarily for use by healthcare professionals and those containing solely pregnancy or antenatal content. Tools aimed at lifestyle factors only without a wider fertility support element were excluded. Mindfulness and relaxation focussed support tools were included only if there was a clear fertility treatment focus. Digital tools specifically aimed at cancer patients to address fertility preservation decision making were excluded from this review as they have been previously reviewed elsewhere (Speller et al., Citation2019). Tools were not included if they were peer discussion or forums only or were static websites with no interactive input from the patient.

Data collection and analysis

Following the app market and wider literature searches, relevant digital tools meeting the inclusion criteria of the review were identified. The search results were initially screened by title and Appstore summaries by two reviewers (IR/OO). Relevant results were then further screened for eligibility based on Appstore descriptions, articles, screenshots, downloading the apps/tools, searching relevant websites, and contacting the developers, if required. Any discrepancies between reviewer decisions were discussed with a third reviewer (YC). Data was collated and analysed on the stated tool aims, salient features and associated costs or availability of in-app purchases.

Thematic analysis was used to answer the research question ‘What are fertility patients’ experiences of using digital support tools during treatment?’. Reviews from ‘App stores’ are a valuable source of insight that can be quickly and easily extracted (Pagano & Maalej, Citation2013). App reviews are unprompted and thus free of researcher bias. Reviews of included digital tools were downloaded and collated from the Apple App store and Google Playstore marketplaces using the ‘AppFollow’ tool (API, Citation2020). Reviews that gave a numerical score only or were irrelevant (e.g. review of clinic rather than digital tool) were excluded. The remaining reviews were analysed thematically following the six-stage process outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Thematic analysis was chosen as it can identify key features and patterns of meaning across a large diverse dataset. An inductive approach to thematic analysis was used. The data was initially coded (using Nvivo software) based solely on the content of the written reviews and these codes were then evaluated to identify patterns of meaning and form themes. A thematic map was generated to determine whether the identified themes reflected the meaning of the coded extracts and the entire app review data set. Final themes were then defined, and results reported, with quoted examples from the review data presented as supportive evidence.

Results

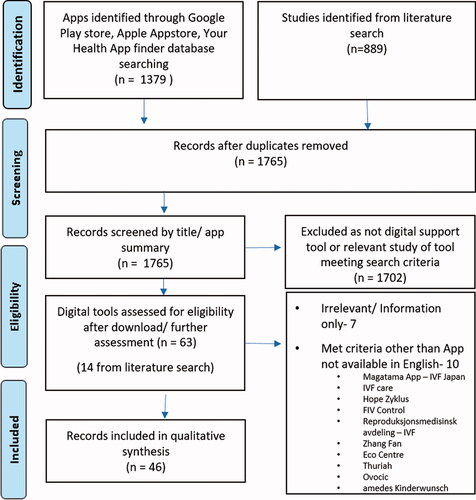

The Appstore search identified 1379 apps and a further 889 potentially relevant studies of digital tools were identified from the literature search (see ). After removal of duplicates, 1765 remained. After screening by title and Appstore summaries, 63 records were identified for further assessment, with 14 of these tools identified from the literature search. At completion, this search identified 46 digital support tools for fertility patients. There were 37 smartphone apps, eight web-based tools and one SMS based tool, as summarised in . and summarise the salient features of digital support tools included in this review.

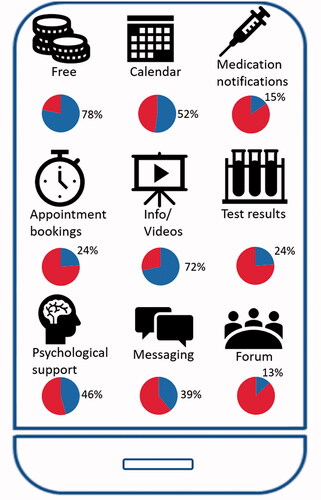

Figure 2. Features available in the digital tools identified within the review. Pie chart below each feature indicates the percentage of included tools containing each feature (blue), not included as feature in the tool (red).

Table 1. Identified digital tools by type/primary aim.

Table 2. Features included within digital support tools.

Information

The most frequent feature identified was the provision of information regarding infertility, fertility treatments and clinic processes (number of tools including n = 33). Treatment and appointment calendars were the next most common feature (n = 24). Calendars ranged from those requiring a patient to manually enter all prescribed medication, to calendars auto populated and updated by the clinical team, to those with the ability to link to a user’s existing electronic calendars. Additional related features (n = 7) included alerts and notifications to remind patients to take their prescribed medications. The medication information presented included drug dosage, information on how to give the injections and step-by-step instructional videos. One app (Wistim) also provided a photograph of the medication packaging to assist identification. These features aim to reduce the chance of medication errors and support patients who may struggle with the complex medication regimes of IVF.

Communication

A direct messaging feature was included in 39% of digital support tools (n = 18). In 16 of these messaging was bidirectional, allowing the patient and clinic staff to both message and respond to each other. Two tools included one-way messaging enabling the clinic to message the patient, but without a function for patients to respond within the app. In one app (Wistim), bidirectional messaging was an optional feature that could be chosen by clinics, with some centres choosing not to receive messages from patients via the app interface. The value of direct messaging was raised in many positive reviews, with patients valuing the convenience of two-way messaging interaction. Integration of the digital tool with the electronic health care record was possible in only two of the apps and one of the web-based programs.

Clinical features

Psychological and emotional support was a feature in 21 of the identified tools. This support ranged from a discussion forum for peer support (n = 6), to guided relaxation tracks, positive affirmations, and evidence-based psychological tools to support coping during stressful life circumstances. MediEmo additionally includes emotional tracking, with patients prompted to enter daily mood scores.

Two of the identified apps included a link to prognostic calculators based on the latest IVF prognosis research. In Kindbody:Fertility Care, these are presented as ‘Predict my success’ tools to ‘Explore the latest fertility research’ and includes a prognosis for the chance of live birth from an IVF cycle or for the predicted egg count from an egg freezing cycle. The SART mobile app includes a calculator to predict success rates for various treatment options based on individual information.

Cost

Most tools were free to access and download. Costs to download for paid apps ranged from £2.79/$3.67 (iMineIVF) to $9.99 (IVF Coaching). One charged a subscription of €15/month (Wistim) payable by the patient by monthly subscription or by the clinic and 6 (12%) offered optional in-app purchasing, with prices ranging from $0.99 to $99.99. For example, in one app (Embie), some features, including tracking symptoms and appointments and accessing the forum community, are free but logging and getting medication reminders requires a $9.99/month premium upgrade. Five included apps required login details provided by the clinic and are routinely included as part of the provider’s package of care (Apricity, MediEmo, Salve, eIVF mobile, Embryomobile).

Ratings/reviews

To analyse user reviews, 484 reviews of the included smartphone apps were downloaded from the worldwide Google Playstore and Apple Appstore. These were analysed using thematic analysis by two reviewers (IR/OO) as described. Twenty-six reviews were excluded as they were irrelevant (reviews of the clinic/clinic team rather than the app, or one-word answers that it was not possible to classify), leaving 458 reviews for thematic analysis.

Identified themes

Thematic analysis generated four main themes (). Firstly, ‘Easily accessibility of information and organisational tools was valued’. Most positive reviewers valued having helpful tools and the ability to communicate with their healthcare team at their fingertips. Reviewers noted that using an app made the complex process of IVF and communication with the clinical team easier:

Table 3. Results of thematic analysis of app reviews.

This app keeps me on my toes from appts, labs, email from nurses and doctors. THE Greatest communication between nurse, doctors, and patients this app has made my anxiety for my fertility more at ease, I love it

Secondly, there was a clear theme that ‘Patients felt cared for through the apps’. This was evident in statements such as ‘I think this was made for me’ and ‘should be prescribed along with the drugs’:

Great idea and made life during treatment easier for us… My partner could use it as well which kept us both on top of things.

The main negative theme identified was ‘Technical problems impaired function, frustrating patients’. It was clear in many reviews that patients were motivated and had tried to use the app but encountered technical and usability issues:

Very bad app. Buggy and gets hung up on every command…. I am going to uninstall the app…. I hope they make some improvements, as I would love the opportunity to access my information via an app!

Related issues around data security and the resultant need for repeated login to apps was mentioned by many negative reviews, with patients reporting that this issue significantly limited app utility. Reviewers made suggestions to improve tools and bypass the need for repeated password entry:

Good app, which is useful to have reminders. But could have better sign in -why put the password every time - better to use the inbuilt phone security as many other apps do.

The final identified theme was ‘Users felt additional costs associated with app use were unfair’. Reviews suggested low willingness to pay for these services on top of existing high treatment costs.

Most of the reviews which focussed on app content were positive, with negative comments overwhelmingly focussed on functionality and cost. These findings are further supported by the studies of included web-based tools that reported user feedback. These report high satisfaction ratings, but the single study reporting willingness to pay found ‘In 90% of all participants, there was no willingness to pay for this intervention’ (Cousineau et al., Citation2008, Haemmerli et al., Citation2010, Tuil et al., Citation2007, van Dongen et al., Citation2016). Overall, thematic analysis suggests fertility patient users are likely to have a positive experience of using digital tools alongside care, if the tools developed are reliable, properly maintained and not associated with additional costs.

Clinical validation/evidence

Despite some of these available tools having over 30,000 users so far, the literature search identified only nine published studies of web-based digital tools and twelve conference abstracts or posters presenting and evaluating various aspects of the use of digital support apps in fertility care. These identified studies are listed in the on-line supplementary material.

Discussion

This systematic review of the App marketplaces and published literature has demonstrated that, of more than 1000 fertility related apps and other digital tools available, only 46 are designed to support those having fertility investigations and treatments. Others are available (e.g. for cancer patients), but they were outside of the scope of this review. Most of the digital tools identified focussed on giving patients information, including via multi-media, at the correct time in their treatment cycle and dependent on their cycle progress. This may improve understanding and avoid the need for overwhelming and generic written or verbal pre-cycle information. Overall, smartphone apps are largely focussed on administrative and practical support, whereas the web-based tools identified were focussed on both psychological support and information provision. This observed focus of app design may reflect physician bias with a primary focus on operational improvements, rather than optimal alignment with patient preferences. The tools that reported involvement of a psychologist in development included psychological support as a central feature, and this should be considered in future designs.

The high prevalence of free to download apps may limit potential investment in developing these technologies, although payment models exist that can potentially continue to fuel their development (Gordon et al., Citation2020). The thematic analysis of app reviews demonstrated the high expectations users have of fertility app functionality, expecting equivalent quality to their other familiar apps and thus being intolerant of poor login processes, technical glitches, and design flaws. The inclusion of psychological support, such as direct messaging with staff, is valued, and some patients feel more ‘cared for’ because of their use of a digital tool. However, providing this additional care is dependent on a staffing model with enough time to send secure, accurate, timely and empathetic responses to patient messages and queries.

Although data security is critical and app developers must be aware of their responsibilities under the relevant law, effort should be made to ensure security features do not impede use of the tool as intended. Increased integration of apps into electronic health records and the provider workflow could improve both uptake and utility of digital tools (Gordon et al., Citation2020). Integration would enable provider prescription, streamline communication, and allow data generated by the digital tool to be accessible to both patients and providers. Involvement or co-production of digital support tools with potential users could optimise development. However, user satisfaction, although critical to engagement, does not always reflect clinical effectiveness (Singh et al., Citation2016).

This review aims to identify a snapshot of digital support tools developed to date and the supportive literature. However, a key limitation of the thematic analysis of app reviews is that it is only based on the opinions of a self-selecting population of app users who chose to post a review. It is likely people reporting strong negative or positive experiences would be more motivated to review and comment. Including only tools available in English and English language reviews is likely to have reduced the cultural diversity of participants and significantly reduced the number of reviews for some included apps, such as Wistim, which is currently predominantly in use in France.

Digital support tools are a rapidly expanding field in medicine, but only a small percentage of all health apps have been studied, and evidence tends to be low quality for those that have (Gordon et al., Citation2020). The development and availability of clear, reliable information on which patients and clinicians can evaluate digital tools is crucial. Available tools such as ORCHA's AppFinder, which underpins the ‘Your Health Appfinder’ used in this search, enables users to discover the strengths and weaknesses of an app before downloading or recommending it. However, evaluation studies and evidence of improvements in outcomes associated with use of digital support tools for IVF patients are very limited. The eight web-based programs and single SMS-based tool included have been evaluated in published randomised trials, but it is notable that none of the 37 smartphone apps identified in this review have yet been evaluated in any study subject to external peer review (see supplementary material online for all identified research). As such, all the included smartphone apps lack robust evidence of clinical and/or cost effectiveness.

If a digital tool aims to reduce anxiety, the impact of usage on validated anxiety scores should be evaluated and if aiming to prevent medication errors the effect on compliance with prescribed regimen should be measured. If a digital tool is designed to optimise workflow and clinic efficiency, then objective measures such as the number/length of unscheduled calls should be recorded. Claims on websites for included tools in the review that are made without any reference to supportive evidence include ‘reduces by 5 treatment errors’, ‘create time for your staff enabling them to provide a higher quality of care’, ‘experience less non-urgent phone calls’, ‘turn those 20 minute phone calls into 1 minute conversational exchanges’, ‘making the treatment more efficient and increasing the success rate’ and ‘reduce the risk of treatment failures’.

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has recently published an evidence framework for digital health technologies (NICE, Citation2019). Fertility teams could utilise this framework and lead evidence-based implementation of digital technologies, with important benefits to the reputation of the sector. Although currently available digital tools are limited, apps/programs for fertility clinicians, embryologists and patients are likely to rapidly expand in coming years. Now is the time to establish optimal standards and develop useful, pragmatic methodologies to evaluate digital tools in fertility care. Evaluation and validation are particularly important if, in due course, the digital tool is envisaged to be a clinician prescribed tool designed to add to, or replace, certain clinical processes or pathways to improve the patients’ experience and care within a fertility clinic. As with any new intervention, clinicians should be mindful of the potential of their tool to cause harm. If a digital support tool is a substitute for face-to-face counselling or educational nursing consultations, it should be proven to meet the clinical objectives at least as well as the existing paradigm.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.4 KB)Disclosure statement

Professor Y. Cheong was a co-founder and developer of the MediEmo smartphone App, which is an included tool in the review. Isla Robertson and Olufunmilola Ogundiran have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Aarts, J. W., van den Haak, P., Nelen, W. L., Tuil, W. S., Faber, M. J., & Kremer, J. A. (2012). Patient-focused internet interventions in reproductive medicine: A scoping review. Human Reproduction Update, 18(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr045

- API (2020). AppFollow. https://appfollow.io/app-review-monitor

- Boivin, J., Scanlan, L. C., & Walker, S. M. (1999). Why are infertile patients not using psychosocial counselling? Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 14(5), 1384–1391. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/14.5.1384

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cousineau, T. M., & Domar, A. D. (2007). Psychological impact of infertility. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 21(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.003

- Cousineau, T. M., Green, T. C., Corsini, E., Seibring, A., Showstack, M. T., Applegarth, L., Davidson, M., & Perloe, M. (2008). Online psychoeducational support for infertile women: A randomized controlled trial. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 23(3), 554–566. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dem306

- Gordon, W. J., Landman, A., Zhang, H., & Bates, D. W. (2020). Beyond validation: Getting health apps into clinical practice. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0212-z

- Grunberg, P. H., Dennis, C. L., Da Costa, D., & Zelkowitz, P. (2018). Infertility patients’ need and preferences for online peer support. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 6, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2018.10.016

- Haemmerli, K., Znoj, H., & Berger, T. (2010). Internet-based support for infertile patients: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 33(2), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9243-2

- HFEA (2019). Patient Support Pathway: Good emotional support practices for fertility patients. https://portal.hfea.gov.uk/media/1442/patient-support-pathway-table-and-long-version-final-002.pdf

- Larson, J. L., Rosen, A. B., & Wilson, F. A. (2018). The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association, 24(6), 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0112

- Linardon, J., Cuijpers, P., Carlbring, P., Messer, M., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2019). The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20673

- Meyers, A. J., & Domar, A. D. (2021). Research-supported mobile applications and internet-based technologies to mediate the psychological effects of infertility: A review. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 42(3), 679–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.12.004

- Morawski, K., Ghazinouri, R., Krumme, A., Lauffenburger, J. C., Lu, Z., Durfee, E., Oley, L., Lee, J., Mohta, N., Haff, N., Juusola, J. L., & Choudhry, N. K. (2018). Association of a smartphone application with medication adherence and blood pressure control: The MedISAFE-BP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178(6), 802–809. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0447

- NICE (2019). Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/evidence-standards-framework-for-digital-health-technologies

- Pagano, D., & Maalej, W. (2013). Conference Paper, 21st International Conference on Requirements Engineering, July). User Feedback in the AppStore: An empirical study., 2013, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. https://doi.org/10.1109/RE.2013.6636712

- Singh, K., Drouin, K., Newmark, L. P., Lee, J., Faxvaag, A., Rozenblum, R., Pabo, E. A., Landman, A., Klinger, E., & Bates, D. W. (2016). Many mobile health apps target high-need, high-cost populations, but gaps remain. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(12), 2310–2318. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0578

- Speller, B., Micic, S., Daly, C., Pi, L., Little, T., & Baxter, N. N. (2019). oncofertility decision support resources for women of reproductive age: Systematic review. JMIR Cancer, 5(1), e12593. https://doi.org/10.2196/12593

- Tuil, W. S., Verhaak, C. M., Braat, D. D., de Vries Robbé, P. F., & Kremer, J. A. (2007). Empowering patients undergoing in vitro fertilization by providing Internet access to medical data. Fertility and Sterility, 88(2), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.197

- van Dongen, A. J., Nelen, W. L., IntHout, J., Kremer, J. A., & Verhaak, C. M. (2016). e-Therapy to reduce emotional distress in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART): a feasibility randomized controlled trial. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 31(5), 1046–1057. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew040

- Zwingerman, R., Chaikof, M., & Jones, C. (2020). A critical appraisal of fertility and menstrual tracking apps for the iPhone. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada: JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada: JOGC, 42(5), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.09.023