Abstract

Considering the growing demand for egg donation (ED) and the scarcity of women coming forward as donors to meet this demand, scholars have expressed concerns that clinics may (initially) misrepresent risks to recruit more donors. Additionally, (non-)monetary incentives might be used to try to influence potential donors, which may pressure these women or cause them to dismiss their concerns. Since the internet is often the first source of information and first impressions influence individuals' choices, we examined the websites of fertility clinics to explore how they present medical risks, incentives and emotional appeals. Content Analysis and Frame Analysis were used to analyze a sample of Belgian, Spanish and UK clinic websites. The data show that the websites mainly focus on extreme and dangerous risks and side effects (e.g. severe OHSS) even though it is highly relevant for donors to be informed about less severe but more frequently occurring risks and side effects (e.g. bloating), since those influence donors' daily functioning. The altruistic narrative of ED in Europe was dominant in the data, although some (hidden) financial incentives were found on Spanish and UK websites. Nonetheless, all information about financial incentives still were presented subtly or in combination with altruistic incentives.

Introduction

Although egg donation (ED) is an established treatment, it is still a medical procedure that entails risks (Tober et al., Citation2020). It is the responsibility of assisted reproductive technology providers to present an accurate description of the risks to prospective donors to ensure that these women are fully informed in their decision-making (Boutelle, Citation2014). Studies have found that potential egg donors will initially look for information about ED on fertility clinics’ websites (Keehn et al., Citation2012, Citation2015). Although the internet can be a useful source of information, it can also be used to advertise and attract consumers (in other words, egg donors and recipients) (Keehn et al., Citation2015; Swoboda, Citation2015). Considering the growing demand for ED, and clinics’ dependency on women coming forward as egg donors to meet this demand, some scholars have expressed concerns. One concern is that clinics may misrepresent risks during the initial recruitment to recruit more egg donors although they may give more detailed information later on in the process (Gurmankin, Citation2001). Since first impressions influence individuals’ choices (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation2013), it is important to study the websites of fertility clinics. Research in the US suggested that often the information presented to donors is incomplete. Keehn et al. (Citation2015) examined egg donor recruitment websites and found that the number of descriptions of risks were disproportionate to the number of indications of the financial benefits of donation. These websites used incentives (monetary and non-monetary) to try to influence potential donors, which Keehn et al. (Citation2015) argue, may cause these women to dismiss medical concerns. Similarly, Alberta et al. (Citation2013) concluded that women were influenced by financial compensation, and that especially those from a lower socio-economic class were significantly more likely to contact ED agencies. Another US study showed that 73% of donors with a lower educational level (meaning, high school diploma or some college) and 26.3% of those with a higher education (meaning, associate’s degree or higher) reported no awareness of physical risks (Gezinski et al., Citation2016). While one out of five donors in another study did not recall any physical risk, most of those who did considered the risks as minor or very minor (Kenney & McGowan, Citation2010). A recent study by Tober et al. (Citation2020) found that 66.5% of participants reported inconsistencies between their experiences and their expectations of ED based on the information they had received. Whilst the highly commercialized US context has been analysed in greater detail, less attention has been paid to the practices of European fertility clinics and the ways they inform their (prospective) donors. Within the European Union, it is not permitted to commercialize human tissue, such as donated eggs and therefore fertility clinics must align their practice within this common framework (European Parliament, Citation2004). In this study, we examine the websites of fertility clinics in Belgium, the UK and Spain in how they present ED to potential egg donors within a European and country-specific context. In particular, we study the presentation of medical risks, incentives (monetary and non-monetary) and emotional appeals on clinic websites. In the discussion, we will also contrast the information presented on the websites with literature concerning ED risks and egg donors’ experiences of them.

Method

Case selection

The data on which this paper is based are drawn from the EDNA study; a project aimed to explore the social, political, economic and moral configuration of ED in the United Kingdom, Belgium and Spain. The EDNA study used an interdisciplinary approach which drew on insights from sociology, bioethics and political economy. Whilst all three countries share a common position regarding the political legitimation of ED as a means of family building, and share features of technological innovation and expertise, they have adopted contrasting regulatory models in relation to the governance of ED (Coveney et al., Citation2022). When clinics recruit donors, they have to abide by their country’s specific laws. For one, Spanish donors must remain anonymous while UK donors are always identifiable. In Belgium, known donation is possible, yet the general position is anonymity. The level of financial compensation for donors also differs across all three countries. Such variety between the three countries provides an interesting and rich context in which to explore and compare representations of ED (Coveney et al., Citation2022).

Sampling: website selection

Stage one involved the identification and mapping of all fertility clinics that recruited egg donors in Belgium, Spain and the UK () (see also Coveney et al., Citation2022). Given the large number of fertility clinics that recruited egg donors, a total sample of 60 clinic websites was selected, taking into account the variety of clinics within each country. Data were collected July 2017–February 2018 (Coveney et al., Citation2022).

Table 1. Country level sampling.

We identified all clinics recruiting egg donors in the UK and Spain. A maximum variation sampling strategy was used to assist the selection of websites for a more detailed examination. This amounted to 30% of the total sample in the UK (n = 21) and 10% in Spain (n = 21). The maximum variability sampling strategy was employed to ensure a diverse and representative selection of clinics. Sampling was based on the clinic’s geographical location (we did not differentiate between but randomly selected clinics recruiting donors across all four nations of the UK; Scotland, Wales, England and Northern Ireland), yearly number of cycles or size of the clinic, whether the clinic was independent or part of a group; and whether the clinic was funded publicly or privately. Individual clinics that were part of a larger clinical group were grouped and counted as one unit as they shared advertisement and recruitment materials (Coveney et al., Citation2022). Clinics were randomly selected across these four criteria.

In Belgium there are two types of centres. A-centres and B-centres can both diagnose and treat fertility issues but only B-centres have access to an assisted procreation laboratory (Belrap, n.d.). All B-centres (n = 18) were included in the Belgian sample.

Three Belgian websites contained no relevant information and one Spanish public hospital was included that had no website devoted to this topic. These were included in the overall count (), but they were excluded from the analysis because these clinics are not contributing to the 'cultural space’ inhabited by clinic websites. Therefore, they were also excluded from the , and because they would otherwise distort the data. and are presented in percentages to make comparisons between countries possible.

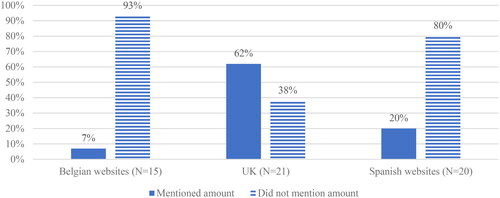

Figure 2. Differences between countries’ websites in mentioning the amount of financial compensation in percentages.

Website text and images were copied and pasted into word documents producing one document for each website. These documents were then uploaded to NVivo 12 for analysis.

Data analysis

Content Analysis (CA) was used in combination with Frame Analysis (FA). CA is used in qualitative research to determine the presence of certain words, themes, or concepts within a text. Once these are determined, they can be quantified (if applicable) and analysed. The focus is on the meanings and relationships of those words, themes or concepts. The text was divided (or coded) into identifiable code categories for analysis (Colombia public health, n.d.). CA is a flexible method that can be used on its own, but also in combination with other methods (White & Marsh, Citation2006). According to Entman (Citation1993) CA needs the conjunction with FA. FA examines the way a communication source defines and constructs a certain subject (Nelson et al., Citation1997). CA needs a theory of framing to avoid treating all positive and negative terms or utterances as equally striking and significant. If it were not guided by a framing paradigm, CA may often produce data that misrepresents the messages that most readers actually pick up on (Entman, Citation1993). Thus, these two analysis methods were combined.

Nvivo12 was used to organize website data specifically for this analysis into three separate datasets, one for each of the UK, Spain and Belgium. The same coding frame was used to analyse each dataset.

The first author reviewed the Belgian fertility clinic websites and drafted an audit report consisting of a coding scheme with descriptions of the codes and a selection of raw data per code. Co-author V. Provoost then audited this report (Provoost, Citation2020). Afterwards, the UK and Spanish websites were coded using the first coding scheme developed for the Belgian data. When codes were not applicable or, conversely, were lacking in relation to the culturally different content of the websites of the UK and Spain, the coding scheme was adjusted and the analysis was then repeated. For example, we coded all texts concerning infections under the code ‘risks’, while coding texts on the age limit for egg donors under ‘donor profile’. The codes were then further sub-divided into additional categories where necessary. For example, the risks category was sub-divided into ‘physical risks’ (including ‘medical risks’) and ‘non-physical risks’. An example of a country-specific code is ‘the possibility of being sued as a donor’, which only appeared in the UK data. At several stages during the analysis, the findings were shared and discussed with the international research team.

Results

The findings section presents three significant themes in the data: ‘physical and medical risks’, ‘incentives’ and ‘emotional appeals’. The main results on each of these sections are presented below.

Physical and medical risks

We focused our analysis on physical and medical risks as these are deemed to be broadly equivalent in each country, since ED follows a (more or less) standard procedure. Psychological/social risks (such as the potential burden of knowing you have a biological child you cannot have a relationship with) were excluded from our analysis as they may differ according to the countries’ legislation. For instance, UK donors are told whether their donation results in a birth and they can enquire about the number of children born, while this information is not accessible for Belgian and Spanish donors. We included risks that were discussed but rebutted or occurrences presented as being ‘no risk’.

Approaches to acknowledging risk

It is not only interesting to study which risks were discussed, but also how they were discussed. We found that acknowledgment or description of a risk was generally accompanied by minimization, normalization, or reassurance (for instance via a statement about the fertility clinic’s excellent care for their egg donors). These three approaches were often combined.

Minimization - when the effect, severity or chance of occurrence of a risk is significantly reduced - was particularly noticeable by the usage of words such as ‘may’, ‘occasionally’, ‘rare’ and ‘some’. This way of presenting risks was often used across the websites of all three countries. In some cases, the minimization came close to a denial of the risks. This way of minimizing risks occurred mainly when OHSS was discussed and was applied to both the frequency/prevalence of OHSS, and the gravity of the risk.

Does donating eggs have any risk?

No, practically none. Our donors usually tolerate the process well. In some very exceptional cases we have encountered ovarian hyperstimulation (excessive response to stimulation treatment). But thanks to the controls we program, we know your state of health in detail and, if this is the case, our medical team minimizes any risk that may exist. (Spanish clinic 19)

Normalization makes an unwanted effect appear as something normal or natural. This was done in three ways: by explicitly calling a risk ‘normal’ or ‘natural’, by comparing effects to things that are generally considered as normal, (such as blood loss and/or pain during a woman’s period) or by mentioning that risks occur in any kind of medical procedure.

You might experience a little abdominal discomfort similar to period pain, but this should subside in two to three days and can easily be controlled with paracetamol. You may also have some light vaginal bleeding for a few days afterwards. These symptoms are perfectly normal after egg recovery. (UK clinic 7)

Statements about the fertility clinics’ care for their egg donors mainly consisted of a description of the care the clinic would offer in case of unwanted effects, the caution they (would) apply and how they worked preventively. These statements suggest an intention to provide a sense of reassurance. They were also regularly used as an opportunity to advertise a clinic and the quality of care they provide.

The [Belgian clinic 2] pays great attention to the medical supervision of egg donors. Based on the reality of the shortage of donor material, we contrast the great motivation of the donor with our greatest professional expertise. Everything is done to keep the risk of infection to a minimum. (Belgian clinic 2)

Physical and Medical risks on websites

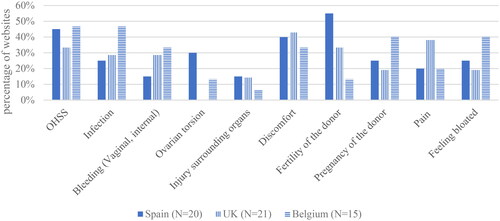

relates to the 40 different physical and medical risks of ED. The presents the ten risks that were discussed by the highest proportion of clinic websites according to the country of the clinic.

Table 2. The physical and medical risks (N = 40) discussed on the clinic websites listed according to the country of the clinics.

One of the potentially significant physical and medical risks of ED is Ovarian Hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS); an iatrogenic complication caused by the ovarian stimulation which is aimed to produce more eggs. While in each of the three countries OHSS was present on a high proportion of websites, there was considerable variation both between and within the countries with regard to which other risks were present. For instance, risk to the future fertility of the donor (mainly presented as the absence of risk) were discussed on more than half of the Spanish websites and a third of the UK websites, versus only 13% of the Belgian websites. Furthermore, risks (and their negation) related to the use of stimulation drugs, such as acne, growing excess body hair and starting menopause early were all discussed on three Spanish websites whereas none of the UK or Belgian websites mentioned them (). For instance, ‘difficulty breathing’ was only found on three UK websites and the risk of ‘an allergic reaction’ was only found on a Belgian website. Fourteen of the 40 identified risks were each only found on a single website. These included risks significantly varying in severity from death to diarrhoea and fainting. This shows how variable the presented risks were, and indicates that there is no standard approach within and between countries.

Pregnancy of the donor

Although the presentation of risks was highly diverse across the sample, there was a similarity in the descriptions and explanations of unwanted effects (including treatments or ways of prevention) that were discussed on websites across the three samples. Potential unwanted pregnancy of the donor (the only risk a donor could control) was the only risk that was consistently not subject to minimization, normalization or reassurance, thus situating the responsibility for mitigating against this risk in the hands of the donor herself. However, there were noticeable differences between the countries’ websites concerning the advice they provided to prevent pregnancy. Only three Spanish websites and one Belgian website advised donors not to have sexual intercourse. This Belgian website, however, indicated that the donor should only abstain from sexual intercourse during the final days of the hormonal stimulation, while the Spanish websites advised sexual abstinence throughout the entire process. The Spanish websites combined this advice with the warning that intercourse might be painful since the ovaries would be enlarged and sensitive because of the hormone stimulation, also increasing the risk for infection when having sexual intercourse. The risk of infection as a consequence of intercourse was never discussed in this context on the websites of Belgium or the UK.

Long-term risks

Within the academic literature, there is no clear consensus on the long-term risks of ED. Interestingly, the two most discussed long-term risks were either absent or refuted on all the websites: the future development of cancer (in this analysis no distinction was made between ovarian or breast cancer) and the possibility that ED might affect the donor’s fertility.

Cancer

Three Spanish, one Belgian and one UK website referred to cancer as a potential risk.

Most UK websites at least at some point referred to the Human fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA). However, only one website (UK clinic 13) mentioned the fact that ‘The HFEA have advised that patients should be aware of a theoretical risk that the stimulation drugs used in IVF could increase the chance of developing ovarian cancer later in life’. This line was followed by the sentence ‘However, a number of very large follow up studies have been reassuring and shown no actual increase, but further research is ongoing’. So although the website followed the HFEA advise, it presented the risk as unlikely.

The Belgian website was equally vague. The influence of ED on the development of cancer was denied, but without a statement that this was firmly proven.

Ovarian stimulation as part of IVF does not appear to increase the risk of breast or ovarian cancer (Belgian clinic 16)

Conversely, the three Spanish websites firmly denied the possibility that ovarian stimulation might increase the chance of cancer.

Does donating eggs have side effects?

No. There is no weight gain, menopause is not advanced, and the chances of developing cancer are not increased. Nor is there an appearance of acne or body hair as some believe. (Spanish 19)

The donor’s fertility

Some authors suggested that it cannot be concluded that the future fertility of egg donors is not compromised because of a lack of follow up studies with egg donors. The websites consistently dismissed the idea that ED would affect the donor’s fertility and thus her ability to have children of her own after the donation. Every Spanish website that discussed this risk, completely denied any chance of negative consequences for the fertility of the donor caused by ED. Some UK websites did not entirely deny the risk, but referred to it as so unlikely that it came across as near impossible.

Will donating my eggs affect my future fertility?

It’s extremely unlikely that donating your eggs will have any negative effects on your own fertility.(UK clinic 7)

The only website that did indicate the possibility of something in the procedure affecting the fertility of the donor was a Belgian website. It pointed out that, even though all precautions are taken, there is always a risk of infection which, in turn, implies a risk for a woman’s fertility.

Recruiting: incentives and emotional appeals

Incentives

The delineation of what was considered an incentive in this study was based on a definition of incentives used in a systematic review of incentives in the context of blood donation. According to Chell et al. (Citation2018) an incentive is ‘an extrinsic reward (monetary or nonmonetary) designed to motivate a specific behavioural action (e.g. recruitment, retention, or reactivation) that is offered before an action occurs’ (Chell et al., Citation2018, p. 245). The reward does not have to be materialistic but can also be a feeling (for example, ‘the donor will feel good about herself after the donation’). The Nuffield Council on Bioethics (Citation2011) defines recompense as a payment where the donor is reimbursed for financial and non-financial losses, whereas a reward goes beyond reimbursement and offers the donor material advantage. We argue that the compensation for the donor’s time, inconvenience, discomfort and pain goes beyond reimbursement. This reward can therefore be considered as an incentive.

Monetary incentives

Financial compensation

Each country offers financial compensation to their egg donors. In the UK, this is an fixed sum of £750, in Spain and Belgium there are no fixed sums but the compensation varies between €500 and €2.000. The financial compensation offered to egg donors was never directly portrayed as an incentive. The majority of websites explicitly presented it as a compensation for the time and effort the donor has to put in, as well as the risks and side effects she might face. However, two Spanish websites explicitly presented financial motivation as unproblematic.

You may already be a mother and you want to help other women to know that happiness or maybe you need financial compensation, whatever the case, you are a heroine. (Spanish website 7)

Additionally, ambiguous descriptions of incentives alluded to financial compensation as an incentive in sentences such as ‘and in addition to personal satisfaction, it offers a series of advantages’ (Spanish website 7) and ‘We compensate your solidarity’ (Spanish website 4). Such descriptions were often expressed in combination with a clarification that the money is compensation, not payment. This in turn was often accompanied with statements about how egg donation is an altruistic act. In this way, the Spanish websites tied the financial, emotional and other forms of rewards and emotional appeals together.

There was a difference between the countries’ websites concerning the specification of the prices of the compensation. This is presented in .

Although the majority of websites mentioned the reimbursement, only the majority of UK websites also indicated the exact amount. Only one Belgian website stated an amount.

Discounts

Only on UK websites, readers were incentivized with egg-sharing. This is a process whereby women undertaking fertility treatment are offered no cost or reduced cost IVF if they are prepared to donate a proportion of the eggs retrieved during their treatment. This was presented as an alluring option (‘reward’) for people who might have trouble paying for their own IVF. This was done by explicitly mentioning that this was an option for people who struggled to pay their own costs, or by stating that egg-sharers received significant discounts. The usage of words such as ‘substantial’ made it appealing as well as the consistent usage of the words ‘free IVF options’.

Worried you might not be able to afford fertility treatment? Our cost-effective options might help you. (UK website 6)

One UK website compared the discount that egg-share donors received with the financial compensation other donors received. However, this website also offered the IVF cycles for free for women who opted for egg-sharing. Another website mentioned that the regular price of £4000 can be reduced to £1575 or £500 (depending on which package chosen). Such reductions and free IVF cycles were clearly a more substantial financial compensation for women who opted for egg-sharing than the fixed £750 donors received in the UK. Four websites mentioned exact prices for egg-sharing. However, the discussion of price reductions were often accompanied by comments that egg-sharing is not only financially beneficial, but also an altruistic act.

Egg sharing helps with the cost of IVF treatment. If you choose to share your eggs then both you and the egg recipient will have the chance of having a baby and the fees for your IVF cycle and drugs will be heavily subsidised. Enabling someone to have a child through the gift of egg sharing is one of the most wonderful things you can do. Our donors feel a huge sense of pride and achievement, knowing the joy they have brought to people who could not otherwise become parents. (UK clinic 18)

Egg-sharing was also discussed on three Belgian websites but it was not promoted or portrayed as a way of reducing the costs of their own IVF cycle. This makes sense since Belgian recipients’ first six IVF cycles are reimbursed by the Belgian health insurance fund, whereas there is limited public funding of IVF in many parts of the UK. Nevertheless, foreign patients and Belgian patients who have used their six cycles could enter egg sharing schemes to reduce the cost of IVF cycles. Since egg-sharing is not offered in Spain, no Spanish website mentioned this option.

Non-monetary incentives

Gratitude/donor appreciation

Receiving appreciation from someone for something you have done to help them, is considered as an extrinsic reward. Such gratitude could encourage women to donate their eggs. The incentive of gratitude was only included in the analysis when it was explicitly given, as presented in the quote below.

We wish all couples who are waiting to receive an egg donation to become happy parents as soon as possible and we thank all the women who have already or are considering donating their eggs. (Belgian clinic 17)

Expressions of gratitude for (potential) egg donors were present on 6 UK websites, 3 Spanish websites and only 1 Belgian website.

The donor will have a rewarding experience

We considered the promise that the donor will feel good (about herself or in general) after the donation and that she will look back on the donation as a rewarding experience, as an extrinsic reward that – when presented on websites that inform potential donors - might motivate women to donate.

This incentive was emphasized on the UK and Spanish websites but not on the Belgian ones. UK websites mentioned that ED is worthwhile because the donor will feel good; about herself or in general. In this context, ‘rewarding’ was the term used most by the fertility clinic, sometimes by usage of testimonies or quotes from experienced egg donors. Other recurring words were ‘pride/proud’ and ‘achievement’. Spanish websites anticipated the good feeling a donor will experience after the rewarding process. Spanish websites mainly focus on how rewarding it is to help other women become mothers. This ‘reward’ is also described as ‘personal satisfaction’ for the donor.

By becoming a donor, you will receive much more than what you give: the satisfaction of knowing that you are helping other people fulfill their wish to have a baby, something that would not be possible without your help. For them, you are their great hope. (Spanish clinic 16)

(Free) extensive health check

Aspiring donors have to undergo certain health tests to check if they qualify as a donor. Frequently, the potential donor receives the results of these tests. This was disclosed on most websites but was not always put forward as an incentive. Only on Spanish websites were test results described as an incentive. These results were explicitly framed to look like an advantage of donating eggs. This was done by emphasizing that the potential donor receives information about her health that could benefit her or by presenting the tests as a free health check. It was also done by often listing the health check among other rewards and benefits associated with ED.

Emotional appeals

We differentiated between emotional appeals and incentives; the first are a way to try to convince women to donate while the latter promise extrinsic rewards. Even though appeals to emotions (such as pity) can motivate specific actions (such as donation), we did not consider them as incentives due to the absence of an extrinsic reward.

Emotional appeals can work in two ways: by making the reader feel pity for the recipient(s), which could motivate her to donate, or by making the reader feel good about herself which also might inspire her to donate.

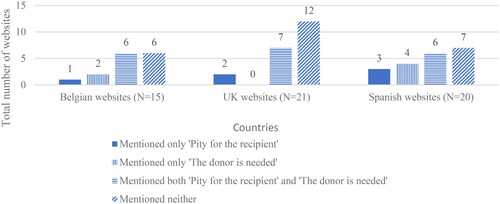

‘Pity for the recipient’ and ‘the donor is needed’

There were two emotional appeals that were often combined on the websites. The first is that websites often described the recipients as unfortunate and heartbroken people, accompanied by the second appeal which states that they need egg donors to achieve their ultimate dream of becoming parents. The idea that the recipients are heartbroken mainly provokes feelings of pity (rather than merely empathy) for the recipients, while the idea that egg donors are needed to ensure that the recipients are no longer heartbroken claims that only you, as potential donor, can help these recipients. The majority of websites that mentioned an emotional appeal, mentioned both. On the UK websites, emotional appeals were mentioned in fewer than half of the cases but websites that did use emotional appeals usually combined the two forms ().

Belgian websites mainly tried to persuade women by emphasizing how ED is the only solution for infertile women (hence, also showing how egg donors are needed) accompanied by statements about how long the waiting lists are, and how, ‘unfortunately’, egg donors are scarce and needed (and thus enticing pity while insinuating that you as potential donor can help). One (Belgian) website used testimonies of recipients to entice pity.

Spanish websites mainly emphasized how hard the recipients have been struggling. Also, the usage of the word ‘suffering’ shows emotional language which emphasizes the difficult situation of the recipients. Instead of saying these women are facing fertility issues, it is articulated as women that suffer from infertility. The usage of emotional vocabulary can subtly add to the feelings of pity towards the recipients. The idea that egg donors are needed was presented with sentences such as ‘we are counting on you’ and ‘this would not be possible without you’. No testimonies of recipients or donors were used to entice pity.

The UK websites combined both approaches found on the Belgian and Spanish websites: the long waiting lists and shortage of egg donors were emphasized, but also how recipients have been struggling for a long time and how ED gives hope to them. This is apparent from the usage of terms like ‘struggling’ and ‘hope’. One website used a testimony from a recipient, which was filled with terms like ‘heartbreak’, ‘struggling’, and ‘dreams’. Another UK website used two testimonies of experienced egg donors, in which the egg donors expressed their pity for the recipients. The idea that donors are needed was made clear by emphasizing that ED is the sole method or last resort for some couples trying to conceive.

Discussion

We found that the clinics framed ED as low risk by minimizing or normalizing risks associated with the procedure. One of the key findings of this study was an ambiguity on the Belgian and UK websites about long term risks while Spanish websites dismissed any long-term consequences of ED. The general denial of risks or implications on the Spanish websites was also shown by Molas and Whittaker (Citation2022). When compared with the medical evidence, we see that in fact the current research data seem to indicate that there are no long-term risks of ED for egg donors. However, such studies were mainly performed with IVF patients as participants instead of donors (Pearson, Citation2006; Woodriff et al., Citation2014). Relevant differences between these groups make it potentially problematic to extrapolate the findings of IVF patients to egg donors (Ellison & Meliker, Citation2011). Studies that were conducted with donors have significant limitations, making it difficult to obtain definitive conclusions on long-term risks (Woodriff et al., Citation2014). This difficulty was reflected on the Belgian and UK websites although the Spanish websites ignored this lack of conclusive evidence. All websites should clearly state that the absence of known risks does not equal the idea that there are no risks.

The field generally recognizes Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS) as the main medical risk (Jayaprakasan et al., Citation2007). We found that readers are informed that the chance of experiencing severe OHSS is very low and that all appropriate measures will be taken in the clinic. This idea is reflected in the literature (Bodri et al., Citation2008). However, mild and moderate OHSS were not discussed on the websites. Nevertheless, side effects of mild and moderate OHSS can also occur and impact donors’ health and functioning. In a Finnish study, approximately 16% of egg donors experienced typical side effects of mild and moderate OHSS such as pain, bloating and nausea (Söderström-Anttila et al., Citation2016). In a Spanish study, 44% of the donors reported physical discomfort of which 14% was about pain and 8% about side effects of ovarian stimulation (Gonzalo et al., Citation2019). Similarly, in a US study, in addition to 12.5% of the donors that experienced OHSS, 45% experienced pain (Kenney & McGowan, Citation2010).

Although mild and moderate OHSS were not discussed on the studied websites, some of their side effects were. For instance, pain was discussed on 20% of the Belgian websites, 20% of the Spanish websites, and 38% of the UK websites. However, experiencing pain during the process of egg collection is included in these statistics, thus the number of websites that reported pain as a side effect of OHSS is smaller than represented here. The proportion of websites that mentioned these side effects is low notwithstanding literature reports of substantial percentages of egg donors that experience them. The most frequent mild side effects and risks were not discussed by more than half of the websites of each country (for example, feeling bloated was discussed by 19% of UK websites, 40% of Belgian websites, and 25% of Spanish websites). A study by Kenney and McGowan (Citation2010) found that only 2.5% of donors were aware that there was a possibility of ‘feeling bloated’, while 31.3% experienced it (Kenney & McGowan, Citation2010). While these risks and side effects of mild or moderate OHSS are not as dangerous as severe OHSS, they occur more frequently, and can lead to disruptions of daily functioning such as work, or result in a general loss of quality of life (Pennings, Citation2020). It seems that mainly medical information is presented, while practical information concerning a donor’s daily life is less often presented. Information about potential difficulties to fit into one’s clothes due to bloating may not be medically relevant but an egg donor might consider this important given the impact on her day-to-day life. Overall, there is more attention to the purely medical information on side-effects and risks than the daily experiences of women – which is a recurring point of feminist critique (Pirie, Citation1988; Wigginton & Lafrance, Citation2019). It could be argued that donors need to be informed about the less serious medical risks and the likelihood of side effects which may impact on daily life (Tober et al., Citation2020). We have to keep in mind that we studied only a sample of fertility clinics’ websites in two of the countries and that clinic websites are not the only source of information that clinics provide for potential egg donors. However, clinic websites can be considered the first point of contact and primary source of information about egg donation for many women. Although potential egg donors are further informed of possible risks during consultations at the fertility clinics prior to the informed consent (Gurmankin, Citation2001), our research shows that the information on risks they are provided with at this initial contact is often incomplete and even, in some cases, misleading. It is difficult to determine what concrete information should minimally be provided on these websites, as no consensus exists on what information is essential for candidate egg donors. It would therefore be interesting if more research was conducted on what both experts and egg donors consider to be essential information in light of a candidate donor’s decision whether or not to donate. However, in the meantime we refer to the eight key criteria for disclosure related to ED that Cattapan (Citation2016) identified (i.e. the nature and objectives of treatment; the benefits, risks and inconveniences of ED; the privacy of donors and their anonymity (where applicable); disclosure that participation is voluntary (withdrawal); the availability of counselling; financial considerations; the possibility of an unsuccessful cycle and potential uses of the eggs retrieved.)

An interesting finding of this study was that financial compensation was never directly presented as an incentive. However, the ambiguous approach by some Spanish websites seems to indirectly present financial compensation as an incentive. By tying the financial, emotional and other types of incentives and emotional appeals together while emphasizing the altruistic nature of the donation, the Spanish websites were able to abide by the regulations whilst subtly portraying money as an incentive (Coveney et al., Citation2022). The UK websites similarly mentioned the altruistic motives for egg-sharing in conjunction with the financial benefits of egg-sharing. However, when discussing the amount of cost reduction, it was apparent that the financial benefits were used as an incentive. Beside the concern that fertility clinics might misinform potential egg donors to increase the number of donations, they can also use incentives as means to this end. Therefore the Nuffield Council on Bioethics published a report which considers how far society can go in encouraging people to donate bodily material (Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Citation2011). Purchasing bodily material is prohibited in all three countries by the EU Tissue and Cells directive (European Parliament, Citation2004). This prohibition is reflected in the finding that financial compensation was never directly presented as an incentive. Within the academic literature, there is a discussion on how to define ‘payment’ and how each compensation could be considered as a payment (Pennings, Citation2015). The clinics staff is using this confusion to their benefit. Hence, our data shows how, although the dominant narrative of ED in Europe is that of an altruistic act, which persists despite each country’s unique culture, economy and regulations (Coveney et al., Citation2022), indirect financial incentives are hidden in the altruistic framing presented on the Spanish and UK websites. We would recommend that clinic websites refrain from presenting financial compensations as a form of incentive, both for egg donation as for egg sharing.

Finally, we found the emotional appeal that ‘a donor is needed’. This type of encouragement is allowed by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics report in the form of ‘providing information about the need for the donation of bodily material for others’ treatment’. However, this appeal is almost always accompanied with the other emotional appeal (‘pity for the recipient’). By trying to elicit feelings of pity from the readers whilst informing them of the need for donors, there now is an emotional element to the informing. This relates to a point Gürtin and Tiemann (Citation2021) made in their analysis of the marketing of elective egg freezing on the websites of fertility clinics in the UK: these websites advertise persuasively, not informatively. However, this still abides by the EU tissue and cells directive and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (Citation2011) report as emotional appeals cannot be considered as misinformation.

Conclusion

In investigating how medical risks and incentives (both monetary and non-monetary rewards) are presented on the websites of fertility clinics, we found that their presentations are not entirely unproblematic.

The Spanish websites ignored the lack of conclusive evidence as they dismissed any long-term consequences of ED and they were the only websites to present free health checks as an incentive. The UK websites were unique in their promotion of egg-sharing and its financial benefits, as well as being the only websites to consistently mention the exact amount of compensation the donor receives. The Belgian websites never used financial incentives and they were the only websites to mention that ED could lead to infertility caused by an infection.

Overall, there seems to be too little attention given to the more mild and moderate risks and side effects of egg donation. The incentives and emotional appeals on the websites conform to the altruistic narrative of egg donation in Europe, with the exception of the (hidden) financial incentives offered on Spanish and UK websites. However, generally, it was done so subtly or in combination with altruistic incentives as to uphold the idea that all incentives and emotional appeals are ‘altruist focused’. Also, by emphasizing how the compensation is not a payment without making a clear distinction between the two, the idea of the altruistic nature of the donation could be maintained.

To conclude, we recommend all websites to clearly state how there are no known long-term risks, such as cancer, but that this does not equal the idea that there are no long-term risks. Furthermore, clinics should include more information on the risks and side effects of ED on their websites, including the effects that are less serious from a medical perspective. Especially, as Tober et al. (Citation2020) also argued, risks that could be considered minor but do affect a donor’s daily life.

Author contributions

L. Jacxsens: analysis; investigation; methodology; original draft; writing; review; editing. C. Coveney: design; methodology; review; editing. L. Culley: design; methodology; review; editing. S. Lafuente-Funes: design; methodology; review; editing. G. Pennings: original draft; writing; design; methodology; review; editing. N. Hudson: supervision; design; methodology; review; editing. V. Provoost: original draft; writing; design; methodology; review; editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-855467, reference number 855467.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alberta, H. B., Berry, R. M., & Levine, A. D. (2014). Risk disclosure and the recruitment of oocyte donors: Are advertisers telling the full story? The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 42(2), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12138

- Belrap. (n.d). Belrap: List of centers. https://www.belrap.be/Public/Centres.aspx

- Bodri, D., Guillén, J. J., Polo, A., Trullenque, M., Esteve, C., & Coll, O. (2008). Complications related to ovarian stimulation and oocyte retrieval in 4052 oocyte donor cycles. Reproductive Biomedicine Online, 17(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60200-3

- Boutelle, A. L. (2014). Donor motivations, associated risks and ethical considerations of oocyte donation. Nursing for Women’s Health, 18(2), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-486X.12107

- Cattapan, A. R. (2016). Good eggs? Evaluating consent forms for egg donation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(7), 455–459. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2015-102964

- Chell, K., Davison, T. E., Masser, B., & Jensen, K. (2018). A systematic review of incentives in blood donation. Transfusion, 58(1), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.14387

- Colombia Public Health. (n.d). Population health methods: Content analysis. www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/content-analysis

- Coveney, C., Hudson, N., Lafuente Funes, S., Jacxsens, L., & Provoost, V. (2022). From scarcity to sisterhood: The framing of egg donation on fertility clinic websites in the UK, Belgium and Spain. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 296, 114785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114785

- Ellison, B., & Meliker, J. (2011). Assessing the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in egg donation: Implications for human embryonic stem cell research. The American Journal of Bioethics: AJOB, 11(9), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2011.593683

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

- European Parliament. (2004). Directive 2004/23/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 on setting standards of quality and safety for the donation, procurement, testing, processing, preservation, storage and distribution of human tissues and cells, CONSIL, EP, 102 OJ L (2004). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2023-0250_EN.html

- Gezinski, L. B., Karandikar, S., Carter, J., & White, M. (2016). Exploring motivations, awareness of side effects, and attitudes among potential egg donors. Health & Social Work, 41(2), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlw005

- Gonzalo, J., Perul, M., Corral, M., Caballero, M., Conti, C., García, D., Vassena, R., & Rodríguez, A. (2019). A follow-up study of the long-term satisfaction, reproductive experiences, and self-reported health status of oocyte donors in Spain. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 24(3), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2019.1588960

- Gurmankin, A. D. (2001). Risk information provided to prospective oocyte donors in a preliminary phone call. American Journal of Bioethics, 1(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1162/152651601317139207

- Gürtin, Z. B., & Tiemann, E. (2021). The marketing of elective egg freezing: A content, cost and quality analysis of UK fertility clinic websites. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 12, 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2020.10.004

- Jayaprakasan, K., Herbert, M., Moody, E., Stewart, J. A., & Murdoch, A. P. (2007). Estimating the risks of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): Implications for egg donation for research. Human Fertility, 10(3), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647270601021743

- Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (2013) Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In: L. C. MacLean and W. T. Ziemba (Eds.), Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I (pp. 99–127). World Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814417358_0006

- Keehn, J., Holwell, E., Abdul-Karim, R., Chin, L. J., Leu, C.-S., Sauer, M. V., & Klitzman, R. (2012). Recruiting egg donors online: An analysis of in vitro fertilization clinic and agency websites’ adherence to American Society for Reproductive Medicine guidelines. Fertility and Sterility, 98(4), 995–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.052

- Keehn, J., Howell, E., Sauer, M. V., & Klitzman, R. (2015). How agencies market egg donation on the internet: A qualitative study. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 43(3), 610–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlme.12303s

- Kenney, N. J., & McGowan, M. L. (2010). Looking back: Egg donors’ retrospective evaluations of their motivations, expectations, and experiences during their first donation cycle. Fertility and Sterility, 93(2), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.081

- Molas, A., & Whittaker, A. (2022). Beyond the making of altruism: Branding and identity in egg donation websites in Spain. BioSocieties, 17(2), 320–346. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41292-020-00218-0

- Nelson, T., Oxley, Z., & Clawson, R. (1997). Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior, 19(3), 221–246. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024834831093

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics. (2011). Human bodies: Donation for medicine and research. https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/publications/human-bodies-donation-for-medicine-and-research

- Pearson, H. (2006). Health effects of egg donation may take decades to emerge. Nature, 442(7103), 607–608. https://doi.org/10.1038/442607a

- Pennings, G. (2015). Central role of altruism in the recruitment of gamete donors. Monash Bioethics Review, 33(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40592-015-0019-x

- Pennings, G. (2020). Mild stimulation should be mandatory for oocyte donation. Human Reproduction, 35(11), 2403–2407. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa227

- Pirie, M. (1988). Women and the illness role: Rethinking feminist theory. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 25(4), 628–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.1988.tb00123.x

- Provoost, V. (2020). Interdisciplinary collaborative auditing as a method to facilitate teamwork/teams in empirical ethics projects. AJOB Empirical Bioethics, 11(1), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2019.1705431

- Söderström-Anttila, V., Miettinen, A., Rotkirch, A., Nuojua-Huttunen, S., Poranen, A.-K., Sälevaara, M., & Suikkari, A.-M. (2016). Short- and long-term health consequences and current satisfaction levels for altruistic anonymous, identity-release and known oocyte donors. Human Reproduction, 31(3), 597–606. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev324

- Swoboda, D. (2015). Frames of reference: Marketing the practice and ethics of PGD on fertility clinic websites. In B. L. Perry (Ed.), Advances in medical sociology (Vol. 16, pp. 217–247). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Tober, D., Garibaldi, C., Blair, A., & Baltzell, K. (2020). Alignment between expectations and experiences of egg donors: What does it mean to be informed? Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 12, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2020.08.003

- White, M. D., & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends, 55(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0053

- Wigginton, B., & Lafrance, M. N. (2019). Learning critical feminist research: A brief introduction to feminist epistemologies and methodologies. Feminism & Psychology, 0(0), 0959353519866058. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353519866

- Woodriff, M., Sauer, M. V., & Klitzman, R. (2014). Advocating for longitudinal follow-up of the health and welfare of egg donors. Fertility and Sterility, 102(3), 662–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.037