ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to illuminate and discuss assessment within dance education in Swedish upper secondary schools through teachers’ reflections. The study investigates how teachers reflect upon the range of possibilities explored and difficulties encountered in their assessment practice. In order to be able to comprehend the phenomenon of teachers’ reflections regarding their assessment practice, both written and verbal teacher reflections were gathered by means of seven interviews with four teachers, and one trilateral talk. Four teachers participated in the study. In the analytical process, the phenomenon was seen, broadened, varied, and then condensed into two themes: Conditions for assessment for learning and Making space for assessment. Both themes have aspects, which are intertwined: both include conditions for assessment as seen through various modalities, methods and tools.

Introduction

I believe grades are mechanical goals in dance education. The students enter this education with their bodies, experiences, preconceptions and difficulties, which makes them vulnerable. As teachers we should affirm students’ development, both in dance and in their identities. It is an emotional and affective process and I believe the scale of assessment in dance should be formulated in such a way that a performance can be graded as either satisfactory or not satisfactory.

A Swedish upper secondary school teacher expresses, in the quote above, that assessment in dance can be experienced as an emotional process, and that the scale of given grades should include only two progression levels – satisfactory or not satisfactory. However, whether or not teachers agree with the current assessment system, they are obligated to assess and grade their students in the regular Swedish school context, which requires them to grade according to the Scale A–F.

Black and Wiliam (Citation2010) emphasise the importance of assessment when expressed as an interactive process. Such interactive assessment can include an action expressed by the teacher, followed by some kind of response from the student (based on his/her understanding of the teacher’s action). The resultant learning experience will be based on the student’s response. Lack of response will have an equally significant impact on the learning process. The teacher must analyse and interpret any divergence between the student’s actual performance and the expressed goal or goals. It is important to note, however, that any such interpretation is by necessity subject to the individual nature of formative personal experiences and differences in worldview on the part of the teacher. According to Sandberg (Citation2012) the curriculum can be understood as a cultural document that relates earlier experiences to the future. Teachers assess their students by themselves and are then required to communicate what has been assessed to the student. Furthermore, teachers are required to make equal assessments, meaning that the goals and scale are universal for all schools, though the way the assessment is put into practice is not prescribed. In addition, they need to provide documentation for all assessments (Ferm et al. Citation2014; Styrke Citation2015; The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011). This grading practice, using a criterion-referenced grading system actually starts as far back as comprehensive schoolFootnote1 (year 6) for Swedish students. While dance is not a mandatory subject in Swedish comprehensive school, it is possible to study dance within the Arts programmeFootnote2 in upper secondary school. Offering a dance concentration in Swedish upper secondary school started with the implementation of curriculum Lpf94, in 1994. No new curriculum was implemented until 2011 when Gy11 began to be introduced and still inheres. While dance knowledge in Lpf94 was presented as separate components (i.e. practice and theory), Gy11 presents dance knowledge in a more holisticFootnote3 way, intertwining the different components (Andersson and Thorgersen Citation2015).Footnote4

The aim of this study is to illuminate and discuss assessment within dance education in Swedish upper secondary schools through teachers’ reflections. Due to the implementation of Gy11, it is relevant to research how teachers reflect upon the range of possibilities explored and difficulties encountered in their assessment practice. Following a brief definition of educational assessment, the life-world phenomenological method chosen for the study will be presented. Thereafter, the method of analysis will be described, followed by the result of the study, which will be discussed in relation to earlier research and life-world phenomenology.

The use and interpretation of syllabi within an assessment practice

In this context, the syllabi can be described as a series of principles and living documents.Footnote5 Based on Styrke’s (Citation2013) study, teachers in Swedish upper secondary school express a need for further knowledge when it comes to interpreting steering documents. Formulations in the syllabi are based on the writers’ collective experiences, negotiations, and instructions (Andersson and Thorgersen Citation2015). Prior studies emphasise the need for the individual teacher’s voice to complement the collective institutional group voice as expressed in the steering documents.

Teachers’ relationships to steering documentsFootnote6 can change over time, and in this process transform the application of the syllabi to the educational process. The use of given criteria in steering documents is dependent on how teachers implement them (Atjonen Citation2014), both in terms of clarity of goals as well as the way in which the teacher realizes them. In order to fully implement syllabi in dance it is necessary for the teachers to develop an understanding of the meaning of both movement elements and structuring elements (Meiners Citation2001). In addition to these elements a professional approach – being aware of one’s conceptions of quality while interpreting and implementing the syllabus into the teaching practice – could be useful (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2012).

The way teachers choose to work with their interpretations of syllabi can have consequences for and determine the assessment practice. According to Klapp Lekholm (Citation2010), it is a teacher’s responsibility to interpret steering documents, to assess and grade students. This process of individual interpretation can be greatly augmented through collegial discussions. Atjonen (Citation2014) and Zandén (Citation2010) emphasise the importance of collegial discussions in assessment. Zandén (Citation2010) further argues that reflections that take place within collegial discussions can make teachers aware of their conceptions of qualities.Footnote7 By embracing other teachers’ assessments through collegial discussions, teachers can question and re-evaluate their own teaching (Atjonen Citation2014).

There are three major types of assessment, which will be discussed here, namely Assessment of learning, Assessment for learning, and Assessment as learning. Assessment of learning refers to conclusive assessment of a specific domain, such a student’s final grade in a specific dance course. Additionally, assessment for learning involves assessment that results in further learning, for example spoken constructive feedback communicated to the student during a dance class. Furthermore, assessment as learning is assessment that steers the learning process, which could emerge if the teacher solely teaches specifically what is formulated in the criteria for a course (Torrance Citation2007). Scholars note that the assessment practice can become too narrow and criteria-based, which moves the practice towards assessment as learning instead of assessment for or of learning (Atjonen Citation2014; Torrance Citation2007). This could mean that explicit criteria and assessment dominate and steer the learning process, making the focus to check off students’ work in relation to the criteria instead of using holistic assessment. Also Sadler (Citation2007) stresses the risk that a too narrow perspective of criteria and assessment leads to fragmentation of knowledge, which, in turn, can limit the way teaching will be executed. Hence, criteria-based assessment can have negative effects (Torrance Citation2007), such as diminishing independence for the student and can influence the degree to which the student is dependent on the teacher (Ferm et al. Citation2014). Observation of dance teachers shows that while their teaching is not strictly controlled by goals and knowledge requirements, these elements are implicit in their teaching (Andersson Citation2014). Tradition in dance also plays a major role in the formation of a teacher’s individual method of teaching and assessment practice. A teacher’s seminal experiences become part of the fabric of the design and practice of dance education and therefore dance assessment. Buckroyd (Citation2000) questions the more traditional role of the teacher as the one, who is totally responsible for the students’ achievement and shows an interest in developing alternate teacher roles wherein students also take responsibility for their own learning process. The roles of teachers in relation to their students are beginning to transform.

Tools for assessment

Sadler (Citation2009) highlights two different approaches to grading, analytic and holistic. Analytic grading is based on separate assessments of different parameters of a domain, for example assessing alignment and movement quality with separate sets of criteria. The results are summarised into a collective assessment of the entire domain. Critiquing the analytic model, Sadler (Citation1989) states that the sets of criteria are intertwined and cannot truly be separated because they each affect the other. Holistic grading on the other hand means that the teacher embraces the domain as a whole, for example assessing sets of criteria simultaneously. Teachers can also verify their assessments by referring to separate criteria if necessary. For the criteria to become less abstract, they need to be applied in a concrete way. For example, to be able to clarify expression in movement a teacher might demonstrate a convincing performance of a certain emotion. Different formulations of criteria can be interpreted and applied in various ways depending on the context, which makes the ground rules for assessment impossible to set in advance. To effectively apply holistic grading method, it is necessary for teachers to understand bases for criteria they are using. Sadler (Citation1989) expresses this as follows: ‘Professional qualitative judgement consists of knowing the rules for using (or occasionally breaking) the rules’ (s.124). Similarly, Zandén (Citation2010) argues that qualitative assessments should involve an assessment covering the whole domain that can be verified by contextually relevant criteria. Each teacher must, whether consciously or unconsciously, routinely meet the challenge as to which of the two grading methods best suits his/her teaching practice.

Traditionally, assessment practice in schools consists of a summary of a student’s achievement and progress (Atjonen Citation2014). The summary is an example of what Brown (Citation2004) calls summative feedback, which if positive, can have effects such as providing motivation, pressure to improve and can also constitute a guideline for the students, teachers and parents (Atjonen Citation2014). If negative, there may be a risk that those students who have a low target achievement might not see the value in persevering. The way in which the information is shared and received by the students is an area of great significance.

Feedback is an important factor in assessment and essential in the learning process (Andersson Citation2014, Citation2016; Brown Citation2004). Assessment should include information about educational goals, the student’s target achievement and guidelines working towards improved achievement (Lundahl Citation2011; The Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011). Various uses of feedback can contribute to unbiased assessment (Atjonen Citation2014). For example, the educational goals regarding expression in movement would need to be clearly communicated to the students along with their current standing in relation to the goals and guidelines for further learning. According to Atjonen (Citation2014) and Brown (Citation2004), assessments should be given to the students more than just once for each area of study. In assessment, feedback, including follow-up, serves a purpose, giving students a steady stream of information about their on-going work, and giving them the possibility of acknowledging their own learning process (Andersson Citation2014). This in turn can function as motivation. Motivation is the reason the students are working. Students need to be sure that they are training for themselves, and not doing it because of some external factor or other person (Buckroyd Citation2000). Feedback can help students to identify and understand their motivation.

In dance education, both individual and general feedback for the whole group can be used (Andersson Citation2014). In order for feedback to have meaning for the student, it is necessary for him/her to understand the feedback, whether directed to an individual or a group. From a life-world phenomenological perspective, this feedback can be seen as intersubjective, where language including various modalities and creates meaning. The meaning of this feedback derives from the mutual understanding between teacher and student. An understanding of someone’s experiences can appear through sharing being-in-the-world (Bengtsson Citation1993). In dance education, feedback is communicated trough various modalities such as the teacher’s own performance as well as verbal words and sounds (Andersson Citation2016).

Rubrics, self, peer and group assessment are tools, which are used in the assessment process. How they are used determines whether or not they are constructive in the student’s learning process. These different ways to work with assessment can be tools for teachers to understand information regarding students’ achievements, while also embracing different individual experiences of the world with which they are inseparably intertwined. Rubrics can also be used as a tool to make students aware of their own learning. Andersson (Citation2016) emphasises that to embrace knowledge in dance, embodied actions, such as a satisfying performance of movement qualities, should be included in the rubric, as a complement to written communication. Even if the student is involved in the assessment process, it is important to be aware that there is still a power relationship between teacher and student (Gipps Citation1999). Teachers are the final arbiters of student grades and student achievement, which makes the intersubjective relationship between them still unequal. Brown (Citation2004) specifically points out that students’ understanding of the assessment criteria can be increased by working with these variations of assessment. The importance of student involvement and engagement in the assessment process has been emphasised in the studies of a number of scholars (Andersson Citation2014; Atjonen Citation2014; Gipps Citation1999). Student involvement in assessment can help to develop confidence, which can be seen as a condition conducive to learning (Atjonen Citation2014).

Making space for learning

In order to learn specific kinds of dance knowledge, such as alignment or movement quality, some conditions are essential. Both teachers and students are body–subjects both situated in the world and inseparable from each other and the world (Alerby Citation2009; Merleau-Ponty Citation1962). Meaning making in dance is dependent on the understanding of this concept (Andersson and Thorgersen Citation2015). Body–mind–soul form the entirety of the body-subject.

According to a life-world phenomenological view of learning, learning takes place as we are experiencing the world through our lived bodies. As body-subjects we are situated in various contexts (such as dance education), where we – through our intentionality and actions – form part of a weaving through our intertwinement with other human beings, things, and phenomena (Andersson Citation2016). Education can be seen as an interactive process, which provides teachers with information about students’ learning difficulties and learning progressions (Black and Wiliam Citation2010), where teachers, students and different phenomena are intertwined. In dance education communication is intersubjective expressed both verbally and non-verbally (Andersson Citation2014). Within this intersubjective communicative educational setting, assessment emerges as a social phenomenon where understanding between the teacher and student is central (Andersson Citation2016; Gipps Citation1999). Through intersubjective communication teachers can experience student expression of dance knowledge. Therefore, learning in art school subject areas, such as dance, is a complex learning process (Andersson Citation2014; Eisner [1991] Citation1998; Sadler Citation1989). Nevertheless, teachers in art school subject areas, such as dance, are still assessing students using direct qualitative judgements. These teachers are solely responsible for both understanding and interpreting their students’ progress and level of achievement according to assessment criteria.

Methodology used to comprehend teachers’ experiences of their assessment practice

To be able to comprehend the phenomenon assessment in dance education, material was gathered through both written and spoken teacher reflections as well as seven interviews with four teachers, and one trilateral talk. These methods provided materials, which made it possible to embrace teachers’ lived experiences of the assessment practice. The different methods allowed follow-up questions, making it possible to further comprehend teachers’ experiences. The reason some teachers chose written reflections and others spoken ones was that the teachers had different preferences. The study adapted to these preferences. Four teachers from three different upper secondary schools are included in the study. Although they all work within the Arts programme in dance their experiences of teaching in Swedish upper secondary schools are varied. The first teacher has an educational degree specific to upper secondary school and has taught within this type of school since the start of the Arts programme in 1994. S/he also has over 10 years experience teaching students of dance pedagogy. Furthermore, this teacher has a professional dance education as well as experience as a professional dancer. The second and third teachers have had education in dance pedagogy. One is perusing a teaching degree for upper secondary schools. This teacher has already had seven years experience in teaching in that form. The other has been teaching within this school form for nine years. The fourth teacher has no formal education in dance pedagogy, but has experience as a professional dancer. While the four respective teachers have different educational backgrounds and teaching experiences, it is important to note that this study does not seek to compare and contrast them, rather it seeks to illuminate and discuss assessment in dance through their written and spoken reflections.

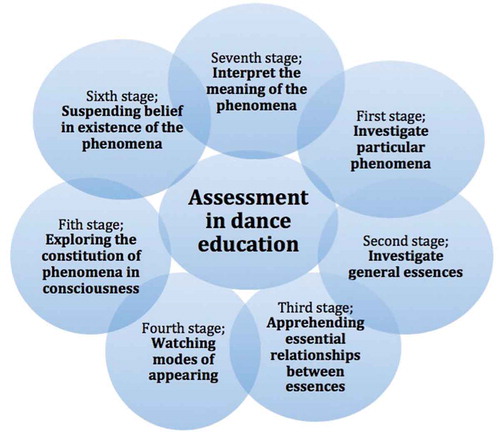

Prior to gathering the materials, the four teachers were informed that participation was optional, inline with the Swedish Research Council’s ethical guidelines (Swedish research council Citation2002). Notes were made during the interviews, which were rewritten into a text document. The trilateral talk was sound recorded and later transcribed. The method used for the analysis of the materials is based upon Spiegelberg’s (Citation1960) seven stages of phenomenological analysis (see ). These stages of analysis provide a framework that makes it possible to comprehend the phenomenon, assessment in dance education, without using a strict fixed structure. The method of analysis includes a systematic process of continuously allowing for adaptability and openness towards the phenomenon, as well as providing a guideline. This method of analysis allows assessment in dance education to be embraced in a broader sense as well as to vary, condense and make the essence of the phenomenon apparent through themes and their various aspects. As body-subjects we are intimately interwoven within the world, the method of analysis supports an open and adaptable relationship with the material. The author’s earlier experiences of the phenomenon, assessment in dance education, continue to be essential in the process of seeing, analysing and describing the phenomenon.

The first stage consists of investigating the phenomenon, assessment in dance education, through phenomenological lens consists of three phases namely intuitive/seer phase, an analytical phase, and a descriptive phase. The materials collected through the various methods were reviewed several times in a non-critical way and various aspects of the phenomenon appeared to be significant and were eventually highlighted with different colours in the documents. Furthermore, the themes and their various aspects of the phenomenon were related to each other in preliminary structures, as general essences. Additionally, based on the highlighted aspects, themes of the essences emerged. The essences as well as the structure in between them were explored in relation to the original material. The phenomenon was visualised as the essences showed themselves through the intuited and analysed material. The second stage involves generalisation of essences. The essences were related and compared by comparing similarities and differences and by examining and conceptualising the phenomenon. Some of the essences of the phenomenon were merged, and new ones were added. Through the connections between essences, themes of the phenomenon began to become clear. Additionally, the third stage includes relations between essences and a first image of the phenomenon was crystallised. This process refined the primary structure of the phenomena. The fourth stage involves eidetic variation, an attempt to identify different modalities that emerged. The relationship between the essences continued to be investigated. Questions that asked in the analysis process were: What aspects become visible in each theme and how do they relate to one another? How does the phenomenon appear as an entirety? Images of the relation between themes and aspects were explored and eventually crystallised in the way they are described in the result of the study. The two themes that appeared were: Conditions for assessment for learning and Making space for assessment. The fifth stage includes exploring the constitution of phenomenon in consciousness. The phenomenon was explored how it was constituted in the consciousness for a scholar in interaction with the material. The phenomenon was examined from different perspectives and in the scholar’s consciousness the phenomenon appeared as a complexity of the entirety. The sixth stage embraces phenomenological reduction; validation of the phenomenon by so called epoché. Translations of Husserl have explained epoché as putting ones earlier experiences in brackets (Citation2004). Merleau-Ponty disclaims an idealistic approach and argues that the idea that one can separate him/herself from his/her own consciousness can be problematic. Instead I have worked not to be separated from but be aware of my experiences of the phenomenon in the analytical process, in order for the phenomenon to be moved towards an independent general description of the phenomenon. The phenomenon, assessment in dance education, including themes their various aspects have been related back to the original gathered material in an effort to ensure that all dimensions of the phenomenon have been taken into account and to explore the ways they have been emerging. The seventh stage involves interpreting the meaning of the phenomenon assessment in dance education. The phenomenon has been interpreted to comprehend the meaning through the different themes and connected aspects. To the participants the question has been raised, within the assessment practice, what consequences for teaching dance and also for dance teacher education might be expected? This is presented later in the discussion section. The results of the study are presented in the following section.

The phenomenon of assessment in dance education

In the course of the analytical process of this study, two themes emerged: conditions for assessment for learning and making space for assessment. Each of the themes, both equally important, in turn consists of various aspects, to be discussed individually.

Conditions for assessment for learning

In the analytical process, different conditions for assessment emerged. The theme, conditions for assessment for learning, comprises four aspects of conditions, which are necessary for assessment to take place; embodied dance material, student motivation and responsibility for learning in dance, students’ various needs and abilities and the meaning of communicated feedback.

Embodied dance material

In order to enable teachers to assess students’ dance knowledge, students’ embodiment of dance material was shown to be important. According to the teachers, a condition for making assessments is to be able to watch the students, which requires that the students perform the material/exercises independently. In analysing the material different methods of embodiment are made visible, which appeared as a condition for being able to assess students’ achievements in dance knowledge. Independence in the assessment practise can be threatened if the assessment practice steers the learning process and becomes assessment as learning (Torrance Citation2007). It hangs by a single thread between making criteria explicit to the students and not letting them control the practice.

Teachers in the study highlight the importance of working with different modes and methods while communicating with the students. An important part of embodiment of dance and a way to influence students’ embodiment is the teacher’s own embodiment of the dance material, i.e. the teacher’s own ability to perform the dance material. One teacher describes a need for students to see the teacher’s bodily demonstration though it becomes ‘… the only template they [the students] can imitate’, and that there is a need for the students to review the material several times. The teachers express that one goal is that students reach independence in their performance. That can for instance mean that teachers do not need to be a visual support for them to remember and perform a specific dance material. One teacher expresses how students can work with learning dance material and indicates that this way of working is something to aim for.

It’s some kind of a perfect specimen in how you want them [the students] to work. You want them to embrace the material, not just embrace it but to get it into their body and preferably give their own unique quality to it, that it should become personal and come from within.

The teachers mentioned that one method is to vary which class material the teacher is embodying for each class. When the teacher steps out of the material the students are left to remember the sequences without a visual guide. In this respect, it is relevant for the students to know themselves whether they need to practice more on the class material or not. In this way, students have the opportunity to practise to see, interpret and recreate dance in their bodies. Another important method of communicating is letting the students compare two different performances of the same dance material, so that students can observe not only how dance material can be embodied in various ways, but also see and understand and what is desirable. Such a comparative approach might include working with images connected to the teacher’s performances and asking questions about similarities and differences in order to develop a critical sensibility. While the teacher is embodying the relevant material through performance, spoken communication can also be used to achieve and clarify material. Going beyond their own performances, teachers can embrace other students’ performances in order to comprehend and reflect upon dance material. One teacher wrote:

They [the students] visualise in how many various ways a movement can be performed and are forced to analyse what makes it right. They can step out of their own performance (and my evaluation) for a moment and observe what they should learn without producing [a dance performance] themselves all the time.

The quote above highlights the importance of embracing other students’ performances in order to get inspiration for your own, as well as get a break from the feeling of being assessed constantly. In addition, beyond the teachers’ performance, other factors that can have significant impact on the students’ embodied dance material were emphasised in the teachers’ reflections. Learning methods such as working in pairs, video recording with mobile phones, dividing the material into smaller parts, watching the material from another perspective, can allow students to comprehend different parameters such as space. The importance of writing notes was also emphasised.

Student motivation and responsibility for learning in dance

The material shows that teachers feel that motivation and responsibility are important aspects of student development and that they play such an essential role in enabling assessment for learning that they can be considered a necessary condition for it. In other words motivation and responsibility in this sense are significant for assessment for learning.

The teachers’ reflections make clear that a student’s motivation is connected to a student’s responsibility for his/her own development. Teachers emphasised that, for learning to take place, it is not enough that they are doing their job as teachers but actions are also required from the student. In dance education, exercises and movements are repeated many times to make inhabitation of movement possible for students. The motivation for learning is crucial for this to become meaningful. Teachers expressed a hope that trust exists between students and teachers, allowing students to take initiative and responsibility for their own work. In order to develop the ability to embrace knowledge, teachers need to be constantly able to challenge and motivate them in their dance performance. One teacher says ‘They are the ones who need to work to reach further and we assume that they want to’. For this kind of work to take place, teachers emphasise that clarity and framework in dance education are necessary elements for the creation of a comfortable and safe environment for learning.

Teachers also emphasised students’ time management in relation to motivation and responsibility. In dance technique classes, it is common that all students do the exact same exercise together, following the teacher’s directions. If a teacher starts to communicate with one particular student, the rest of the class needs to keep working. One teacher states ‘If I am engaging in a private conversation with one student, I want the rest of the class to work on either the previous activity or stretching’. While the teacher gives individual corrections to one student at one end of the dance studio the rest of the group can become cold and passive if they don’t take responsibility for their own learning and find something to work on until the teacher is ready to work with the whole group again. Their ability to work while the teacher is occupied is connected to their responsibility for their own development and work toward a higher target achievement. The students continuing ability to work is based on reflections and feedback from their own performance, which is part of the process of assessment for learning. The teachers point out that it is important to express the importance of individual responsibility at the beginning of the students’ course of study, to make it a natural part of dance education. Responsibility can also be related to the student’s independence in relation to their work, as one teacher clearly states; ‘My absolute stance in my work with students is that they should become independent’. Teachers also related independence and the student’s sense of his/her own work to the memorising of dance material from the class. Take the initiative and the responsibility to learn material by heart can be a concrete result of motivation.

According to Atjonen (Citation2014), grades can also have a positive effect on motivation for students and provide an important guideline for their achievement, but grades in themselves do not create a valuable reason to try unless it is also possible for students to see their own improvements and progress. Teachers in this study do not emphasise grades as a factor for motivation, rather the opposite, as mentioned in the introductory quotation of this paper. Types of motivation that are significant here are more related to communication as well as to the student’s own responsibility. According to the teachers, the social aspect of assessment and learning is important for motivating students and letting the education be an interactive process.

Students’ various needs and abilities

Teachers’ ability to individualise dance education and feedback is prerequisite for working with assessment for learning. Teachers stress that individualized learning is about different student needs, such as learning difficulties and different bodily conditions as well as to help develop individual abilities. For example student’s receptivity to feedback can differ and they also can have different abilities to assimilate feedback because of their health problems or motivational issues. For students who have health conditions and are not able to take part in a regular dance class, teachers can introduce individual modifications and re-assess parts of the course content to suit the specific needs of those students. According to the teachers, this will make it possible for the student to at least fulfil parts of the syllabus. Teachers stress that students have different capacities to absorb individual corrections, which are needed in future learning and development. One teacher states the following:

Overall I think I’m doing different things because some [students] can handle corrections and some can’t handle corrections, they must first learn what a correction is and how to receive it. There are always a few who are unable to receive a correction. In the beginning you must sometimes give some students a little time and then it can also occur that some are stressed if you even touch them.

Teachers say that body contact is important for assessment for learning. However, some students are particularly sensitive to this kind of close contact. Some teachers choose not to use body contact at the beginning of a term to avoid potential negative reactions others that they try to notice and decide whether it is ok for students to be touched.

Education in dance has long-term and short-term goals, and the teachers show some flexibility as well for the individuals as for the group. The adaptability to the intersubjective learning context is therefore important. This flexibility has to take into consideration the power relationship that exists within a teacher-student relationship (Andersson Citation2016; Gipps Citation1999). According to the teachers’ reflections the need for balance between teaching towards goals and students’ needs and abilities is something that teachers must constantly be aware of to find harmony (between teaching goals and individualisation). Teachers in this study clearly emphasised the importance of using a variety of feedback methods based on students’ needs and abilities to individualise their teaching. Teachers consider the use of various types of feedback is a necessary condition for assessment for learning (Atjonen Citation2014). Teachers’ feedback can be connected motivating students, increasing the student understanding and experience of feedback, and enhancing the quality and understanding of the goals of feedback. Pushing students to develop themselves to their full capacity and give them individual praise and encouragement are techniques emphasised by teachers. The purpose for using these various methods is to improve student learning in as many ways as possible. As one teacher states ‘I know it’s important with many roads to learning, and by using several paths, you can increase the chance that the students will have an a-ha experience’. Teachers stress that communicated feedback depends on students’ daily physical condition and that teachers need to be responsive to student’s impressionability, which can change on a daily basis. Student development can be facilitated if the teacher encourages development of the student’s dance performance ability. By encouraging students to spread their wings, the opportunities for learning and an improved target achievement are increased, which is part of assessment for learning.

The meaning of communicated feedback

Feedback between teacher and student requires an understanding to exist in order for the student to comprehend and learn how to improve his/her achievement (Andersson Citation2016; Gipps Citation1999). Teachers and students must also have a common understanding regarding corrections to avoid misunderstandings. Effective communication needs to connect to the student’s frame of reference. Just as teachers introduce body contact at the beginning of a term, teachers also point out the importance of introducing what a correction means and how to handle it in order to be able to meet students’ needs. One teacher introduces images as background to a discussion about different body placement in order to have mutual references for the body placement target. Using feedback that involves body contact is by teachers considered as a ‘natural’ part of dance education. Body contact is a form of feedback in which the student’s embodied response can show the student’s understanding of the meaning of the feedback. As a teacher, it is difficult to be sure that students really understand; Often students’ communicated response based on feedback can be a bit unclear. One teacher writes:

I usually ask to see if they understand. Sometimes I feel that body contact makes it easier to explain though I physically can see that the student understands when she or he makes corrections. It is tricky as a teacher to know if the student has understood because it is certain, even though the student makes a physical correction.

Based on the student’s continuing work with previously given feedback, follow-ups can function as continuous work with understanding. These follow-ups can play an important role, letting students know that they are on the right path. This can be seen as adaptability between the student’s learning and the teacher’s communication as a form of feedback, to see feedback as something recurring instead of a one-off. Teachers emphasised that students are embodying general feedback directed to the whole group, as a way to get the knowledge into the body. Teachers expressed the significance of being clear to whom the feedback is being directed. To make this direction of feedback clear, the teachers sometimes say the student’s name, or in communication use their bodily focus directed to a specific student. By diversifying to whom the teacher directs his/her communication to, in different exercises, the teachers can meet all the students during class. One teacher says:

I try to distribute corrections evenly between students and emphases on different exercises during different lessons, so that students themselves have the opportunity to work on corrections in peace at certain times.

Teachers also emphasise that prioritising their work is important. The purpose of teaching is one thing, but it is additionally important to prioritise different aspects of dance knowledge that need to be developed in order for students to have the opportunity to achieve higher target achievement. Within the core content of the course, different areas can get different priorities. Understanding can be created as a condition for assessment if students are being introduced to the purpose of corrections. Corrections can be seen as something positive and something students should expect to get. In the quotation below, one teacher states, that the teachers’ underlying purpose in using corrections is not always clear to the students.

It [correction] is a reward, they take it often as a punishment, and that it’s a way to be told that you are doing something wrong. I usually have to explain to those that it is when one is not corrected at all it should feel unfair, not the other way around.

Encouragement such as ‘good and nice’ is justified by the purpose to spread positive energy and a fighting spirit. This can become intertwined with the acknowledgment and confirmation to increase learning that is made visible as an aspect of individualisation. This type of feedback can be provided to strengthen this particular person or follow-up what the teacher and student worked on previously. Teachers emphasised that self-confidence can have positive effects on the learning process and the students’ involvement and engagement can be one way to accomplish that (Atjonen Citation2014). One risk that is emphasised is the teachers’ spontaneity in their communications, for example by saying ‘good’. Some teachers expressed this type of communication spontaneously, despite being aware that this could be considered non-constructive feedback. Subsequently, some teachers clarify themselves by adding further specific information to the feedback to clarify the purpose. The importance of pinpointing feedback was seen in the gathered material, where communication such as ‘good’ is not always communicated as precise feedback.

The meaning of the corrections can appear as help for students and a way for teachers to guide students further in their development. Through using variation in spoken feedback different tempo, volume, dynamics, intonation, can convey the qualities of movements and can function as guidance for the student as to what to focus on. Another way to understand corrections is that they function as a code in dance education, and codes are a part of the criteria in the syllabi. A teacher says:

It’s something they have to work on, like the codes that are part of the criteria, they should be able to take a correction and be able to use it and if they cannot even get a correction then we have nothing to … there is no development and we have nothing to grade either. It [correction] is such a big part of coping with a dance lesson.

Based on the quote above, corrections can become visible not only as a requirement for obtaining material as a basis for grading but also seen as a natural part of the dance class. As mentioned, feedback is apprehended as a ‘natural’ part of a dance lesson and also a main ingredient in assessment. In this study, teachers emphasised assessment for learning more clearly than assessment of learning, which does not follow Atjonen’s (Citation2014) argument that summary of assessments are more conventional.

Making space for assessment

This theme revealed that teachers use various tools to critically view, broaden and deepen three different aspects of assessment: self-assessment as tool for assessment of dance knowledge, teacher assessment of dance knowledge, and syllabi as tools for assessment.

Self-assessment as tool for assessment of dance knowledge

Self-assessment was highlighted in different ways by teachers and was seen as a tool for assessment. Teachers expressed that the students who cannot participate physically in dance education, for example because of injury, can instead actively observe the dance class. The purpose is to reflect upon their own learning and to create strategies for further learning. According to the teachers, active observation could be that the student writes down reflections based on goals and purposes of the class content. Subsequently, they assess what they need to work on with their own learning outcome. Teachers expressed that they then take part of these notes and make comments to the student. These written notes create communication about the assessment of the student’s dance knowledge based on the student’s self-assessment. By making the goals of the syllabi visible, students can gain an understanding of the assessment practice. The teachers emphasise the importance of observing other students. One teacher says:

They also work in pairs at times, and students are forced to understand the core of the movement, so they do not talk about insignificant things. Or conversely, a student can demonstrate this understanding more than the body is able to show. That is to say the understanding is in the head, but not yet in the body (e.g. due to physical barriers).

An active observation of other students can also, according to the teachers in this study, be used to make a self-assessment that can improve the student’s understanding. One teacher states: ‘Sometimes they actively look at each other, observe and learn how to correct themselves.’ Students also get the opportunity to work with the assessment of one another, so-called peer assessment. Atjonen (Citation2014) argues that this dialogue between peers can be beneficial. By communication with other peers, it is possible to get perspective and reflect upon your own learning process, which is an important part of assessment.

When it comes to spoken reflection about students’ own learning, it is difficult for students to make themselves heard and to take a position in discussions. The teacher is responsible for creating opportunities for all to be heard, but it can be difficult to get the discussion to ‘flow naturally’, as one teacher argues. Students’ self-assessment could be part of dialogues between teacher and student about grading. Teachers emphasise the importance of students’ own responsibility for learning, which is also intertwined with the theme Conditions for assessment for learning, see above.

Teacher assessment of dance knowledge

To step out of the process of embodying the material creates an opportunity for the teacher to embrace students’ achievement, work and communicate feedback. According to teachers, there are few advantages of embodying dance material when teachers make assessments. Observing students’ dance performance enables teachers to assess the performances in different ways. By finding tools that help them to step out of the role as a visual demonstrator, it makes it easier for the teacher to focus on the students and be able to assess them. One teacher expresses that it involves ‘scanning students’, which could be interpreted as different ways of assessing student performances.

Organizing the students in smaller groups enables the teachers to assess the students one at a time. For instance, teachers expressed that students can work in pairs across the diagonal of the room. One teacher says

For me it’s about seeing how they [the students] are placed and that I’ll get to see them one by one. That means that sometimes they have to do an exercise many times for me to get to see everyone.

Another tool that can be used is collegial assessment, where teachers assess student performances together. One example mentioned was that when teachers have trainees taking over the teaching, they can allow the trainees to assess students and then compare these with the teachers’ own assessments. Another way is to use dance trial, which offer possibilities for a collegium to observe students’ performances at the same time. Furthermore teachers can then have a discussion with one another about their experiences of the students’ performances. Teachers expressed the importance of collegial discussions, but emphasise the lack of time to make that possible.

According to teachers, documenting student performances could be a basis for assessment, and also a tool for assessment. Teachers use written notes, video recordings, students’ written reflections and journal communication. This is used to remember prior feedback and to document assessments made during class. By using a longer period of notes the teachers can follow the progress. The teachers emphasised that it is common to use rubrics in documentation. One teacher states: ‘How can we use rubrics and words in dance without disrupting the class by taking out pen and paper and start writing, how can we instead make it a part of our education?’ Teachers that used rubrics used it as a method for working with assessment, documentation, and communication with students. The purpose is to compile tools that will help clarify the students’ current achievement level. Rubrics are also used as a tool in grade conferences during the academic year, but as the quotation above shows, it can disturb an influence the actual teaching, and may not be a well-suited tool to enable teacher assessment of dance knowledge.

Syllabi as tools for assessment

The teacher participants in this study had different ways of relating to steering documents and how the syllabus is used in the assessment practice. Several teachers split the teaching actions within the same course, and together covered the goals of the course. Teachers therefore also assessed the course together. Teachers emphasised their responsibility to make the syllabus explicit for students to have the same point of reference when it comes to assessment. Different approaches to steering documents are based on how teachers perceive the syllabus and its function. Some of the teachers said that their teaching is based on the syllabi, and that the syllabi support their assessment. One teacher stressed that the syllabi describe common steps in a dance class, and is therefore not used as a living document during the school year because the teacher felt confident that the core content is a ‘natural’ part of dance education. One teacher had not read the syllabus because in his/her opinion, his/her dance teaching experience enables him/her to recognize a good performance.

Discussion

Even if assessment criteria are self-evident to dance teachers, they may not be obvious to students. According to assessment research, implementing criteria and making them explicit for students is important, and is significant in the communication between students and teachers. In this study, it was seen that teachers had varying approaches as to how to use the syllabi and therefore, had different prerequisites and strategies for communicating course goals to students. The varying approaches regarding steering documents reflected variations in the use of criteria by different teachers and schools (Atjonen Citation2014). Teachers are responsible for interpreting the steering documents (Klapp Lekholm Citation2010). The resulting differences in teachers’ approach can lead to differences in students’ education, hence the teachers’ different interpretations are steering what is included in students’ education. Teachers usually have more experience in dance education from different perspectives than their students. In researching assessment it is clear that students’ awareness of their educational goals is also an important part of their learning process (Lundahl Citation2011). Teachers’ experience is also an important part of the learning process, though their implementation of syllabi is dependent upon their respective interpretations of the given formulations (Meiners Citation2001).

To be able to understand the student’s feedback in relation to the goals of a course, it is essential that goals, criteria and educational process are intertwined and constitutes the intersubjective setting. But as Torrance (Citation2007) emphasises, there is a necessary balance to be achieved between focus on criteria and the learning process as a whole. Too wide a focus on criteria, however, can control the practice, and have a negative influence on the students’ independence. Neither this study nor life-world phenomenology can provide a single answer to this challenge. Openness and adaptability on the part of teachers is crucial to finding the appropriate solution for each specific situation and student, as well as to ensure that students are involved in the process (Atjonen Citation2014).

Follow-up feedback is an essential part of students’ learning processes as well as for the development of teaching practices (Lundahl Citation2011). Documentation can also help to provide accurate feedback regarding the communication between teachers and students. Dance teachers commonly teach students in groups and repeatedly meet the same students in different courses. Without documentation, the teacher is wholly dependent on the embodied experiences and intersubjective communication they have with their students, which can be challenging especially in a repetitive setting. Tools for documentation and communication between teachers and students can give intersubjective communication and feedback a deeper meaning and improve the understanding of assessment processes. It is important to specify and build understanding of the meaning underlying the feedback (Andersson Citation2016; Gipps Citation1999). In this study, teachers emphasise feedback as a ‘natural’ part of dance education. Based on this study and my own experiences as a dance student and teacher I believe that feedback, traditionally, is a major part of dance education (Andersson Citation2016). It would be interesting for teachers and students to reflect upon the content and quality of feedback, to question and reflect upon earlier experiences and traditions.

The assessment process must take place more than once (Atjonen Citation2014; Brown Citation2004), which requires that dance examination not be a one-time activity. Through a process by which the activity of assessment is both more frequent and more individualised, a variety of assessment methods can be used during the term (Brown Citation2004). Variety of assessment methods is also apparent in teachers’ reflections, where the variety of tools for assessment is brought to our attention. For example one method was to modify and adapt the assessment process to the individual students. This is, to adapt to a student’s learning needs in order to make the education equitable and thereby giving all students opportunity to progress, each at his/her own level. This is in line with The Swedish National Agency for Education (Citation2011). Seeing students as one homogenous group of people in a predefined context can diminish the social phenomenon assessment because it limits seeing them as individuals. Teachers are expected to be open and adaptable in the ways they meet and communicate with students. Their different lived experiences constitute various conditions influencing the assessment practice. Variety in feedback methods (Atjonen Citation2014) can be one option used to accomplish equitable assessments. For example, the development of rubrics as a feedback method is important in this study. I see rubrics as fulfilling a purpose in holistic assessment depending on how and when they are used. Holistic assessment involves returning to specific criteria (Sadler Citation1989), such as spatial awareness and dynamic variations made up of various aspects, which together create its meaning. The rubric is the puzzle and the different criteria are the various pieces completing the puzzle, which you can barely see when you embrace its entirety. Dance is embodied action that needs to be transformed from movements into written words when we work with rubrics (Andersson Citation2016). The use of a digital video-based rubric instead of written words, could be a solution to the difficulty of incorporating embodied action into assessment documentation.

Collegial discussions were also highlighted as useful for assessment, which is in line with earlier research (Atjonen Citation2014; Zandén Citation2010). Teachers expressed their need to engage in collegial discussions, but finding the time was an issue. Based on the study, conditions regarding time and logistics needed to make collegial conversation possible and they provide a way to develop adequate and equal assessments. It is important that teachers critically reflect over their earlier experiences in order to become aware of their conceptions of quality (Zandén Citation2010). Collegial discussions might also be helpful in this process to provide professional approach. As mentioned earlier this process can be connected to the phenomenological method of analysis, to become aware of one’s earlier experiences regarding a specific phenomenon.

This study presents teachers’ experiences regarding conditions for assessment of dance knowledge and in the way in which the teachers reflect on possibilities and difficulties in their assessment practices. For assessment to be meaningful, it is important that there be an understanding between students and teachers. This understanding combined with the teacher’s openness and adaptability, is more likely to result in an individualised, equitable assessment. To be able to comprehend the range of possibilities explored and difficulties encountered with assessment, collegial discussion can also be a valuable tool. Support for assessment in dance from the Swedish National Agency for Education could be given to provide teachers in the development of their assessment practice. Such discussions and reflections are necessary for the future development of authentic assessment practices in dance education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ninnie Andersson

Ninnie Andersson, PhD, is currently a Senior Lecturer in arts education with focus on dance at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Ninnie is coordinator for the five yearlong dance teacher program at the same university. She graduated in 2016 with her phenomenological thesis about assessment in dance education in upper secondary schools. Ninnie has presented her work internationally at educational conferences focusing on dance as well as assessment. Beside her research and work at the university she is also a dance teacher at a dance program in a Swedish Upper secondary school. Her main focus is in jazz dance, and she has been certified in the Simonson technique by Linn Simonson. Since 2013 is she teaching the certification course of Simonson Method of Teacher Training together with Lynn.

Notes

1. Comprehensive school is equivalent to American middle school.

2. The Arts programme is a national program and is a higher education preparatory program.

3. In holistic assessment, the domain is assessed as an entity.

4. The syllabi in Gy11 include various competencies that should be included in dance education. Based on three roles the syllabi include generic abilities and subject specific knowledge areas, For exact wording of the syllabi see http://www.skolverket.se/laroplaner-amnen-och-kurser/gymnasieutbildning/gymnasieskola/sok-amnen-kurser-och-program (last accessed 18 November 2015) and what dance knowledge should be assessed can be found in the paper: Andersson and Thorgersen (Citation2015).

5. The Swedish curriculum includes the schools’ assignment and the basic values that should impregnate the school. Subject specific syllabi and their related knowledge requirements are also included in the curriculum. The government determines both the curriculum and syllabi.

6. Steering documents include different documents that regulate the school activity and consist of laws, statutes, curriculum, goals, prescriptions and guidelines.

7. Teachers’ conceptions of quality are used normatively and are based on the teachers’ perception and earlier experiences.

References

- Alerby, E. 2009. “Knowledge as a ‘Body Run’: Learning of Writing as Embodied Experience in Accordance with Merleau-Ponty’s Theory of the Lived Body.” Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 9 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/20797222.2009.11433984.

- Andersson, N. 2014. “Assessing Dance: A Phenomonological Study of Formative Assessment in Dance Education.” InFormation-Nordic Journal of Art and Research 3 (1). doi:10.7577/if.v3i1.936.

- Andersson, N. 2016. “Teacher’s Conceptions of Quality Expressed through Grade Conferences in Dance Education.” Journal of Pedagogy 7 (2): 11–32. doi:10.1515/jped-2016-0014.

- Andersson, N., and C. F. Thorgersen. 2015. “From A Dualistic toward A Holistic View of Dance Knowledge: A Phenomenological Analysis of Syllabuses in Upper Secondary Schools in Sweden.” Journal of Dance Education 15 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/15290824.2014.952007.

- Atjonen, P. 2014. “Teachers’ Views of Their Assessment Practice.” Curriculum Journal 25 (2): 238–259.

- Bengtsson, J. 1993. Sammanflätningar: Husserls och Merleau-Pontys fenomenologi [Intertwinings: Husserl’s and Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology]. (2., rev. uppl.). Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 2010. Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment. London: Granada Learning Assessment.

- Brown, S. 2004. “Assessment for Learning.” Learning and Teaching in Higher Education 1 (1): 81–89.

- Buckroyd, J., ed. 2000. The Student Dancer: Emotional Aspects of the Teaching and Learning of Dance. London: Dance.

- Eisner, E. W. (1991) 1998. The Enlightened Eye: Qualitative Inquiry and the Enhancement of Educational Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. ISSN 1833-1505

- Ferm, C., O. Zandén, J. Vinge, J. Nyberg, N. Andersson, and L. Väkevä. 2014. “Assessment as Learning in Music Education the Risk of ‘Criteria Compliance’replacing’learning’in the Scandinavian Countries.” In Nordic Network for Research in Music Education. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1005102/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Gipps, C. 1999. “Socio-Cultural Aspects of Assessment.” Review of Research in Education 24: 355–392.

- Husserl, E. 2004. Idéer till en ren fenomenologi och fenomenologisk filosofi [Ideas to a Pure Phenomenology and Phenomenolgical Philosophy]. Stockholm: Thales.

- Klapp Lekholm, A. (2010). Lärares Betygsättningspraktik. In S. Eklund (Ed.), Bedömning för lärande: - en grund för ökat kunnande [Assessment for learning: - a base for increased knowing]. Stockholm: Stiftelsen SAF i samarbete med Lärarförbundet. Retrieved from http://www.forskul.se/tidskrift/nummer3/

- Lundahl, C. 2011. Bedömning för lärande [Assessment for learning]. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Meiners, J. 2001. “A Dance Syllabus Writer’s Perspective: The New South Wales K-6 Dance Syllabus.” Research in Dance Education 2 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1080/14647890120058339.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge.

- Sadler, D. R. 1989. “Formative Assessment and the Design of Instructional Systems.” Instructional Science 18 (2): 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF00117714.

- Sadler, D. R. 2007. “Perils in the Meticulous Specification of Goals and Assessment Criteria.” Assessment in Education 14 (3): 387–392. doi:10.1080/09695940701592097.

- Sadler, D. R. 2009. “Indeterminacy in the Use of Preset Criteria for Assessment and Grading.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 34 (2): 159–179. doi:10.1080/02602930801956059.

- Sandberg, R. 2012. “Towards a Critical Curriculum Theory in Music Education.” Nordic Research in Music Education Yearbook 11 (13): 33–55.

- Spiegelberg, H. 1960. The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction. The Hague: Kluwer.

- Styrke, B.-M. 2013. Dans, didaktik och lärande: om lärares möjligheter och utmaningar inom gymnasieskolans estetiska program [Dance, Didaktics and Learning: About Teachers Possibilities and Challenges within Upper Secondary School’s Arts Programme]. Stockholm: Dans och Cirkushögskolan.

- Styrke, B.-M. 2015. “Didactics, Dance and Teacher Knowing in an Upper Secondary School Context.” Research in Dance Education 16 (3): 201–212.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2012. “Bedömningsstöd i Musik [Support for Assessment in Music].” Accessed April 19 2016. http://www.skolverket.se/polopoly_fs/1.171599!/Menu/article/attachment/Bedomningsstod_Musik_Om_materialet_150107.pdf

- Swedish research council. 2002. Forskningsetiska principer -inom humanistisk-samhällsvetenskaplig forskning [Ethical Guidelines for Research- within Humanistic and Social Scientific Research]. Accessed January 20 2015. http://www.codex.vr.se/texts/HSFR.pdf.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education. 2011. “Curriculum for the Upper Secondary School.” http://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=2705

- Torrance, H. 2007. “Assessment as Learning? Assessment in Education: Principles.” Policy & Practice 14 (3): 281–294.

- Zandén, O. 2010. “Samtal om samspel. Kvalitetsuppfattningar i musiklärares dialoger om ensemblespel på gymnasiet [Discourses on music-making: Conceptions of Quality in Music Teachers’ Dialogues on Upper Secondary School Ensemble Playing].” PhD diss., Art Monitor, Gothenburg.