Introduction

With each week’s news coverage of late, it seems we are in a ‘race against time before the ‘next big one’ hits, be it a natural disaster or drastic political and policy swings due to increasing polarization, rising conservatism and other challenges across the globe. The practice and scholarship of planning also is intimately connected to its own race with time – both in planning for the future, based on knowns and unknowns, and also sometimes against what time has wrought, righting the wrongs of past acts of history.

Planning values and objectives have sought to benefit all members of society. But the increasing organization of opposition groups, on the right and the left, assisted by the new technology of social media, is making hyper-polarization a more central feature of planning audiences and public policy. Thus, planning in our current contentious moment provides a vexing problem, particularly when the views of leaders in local and higher-level government, as well as some in the outspoken citizenry, do not align with progressive planning goals. As a result, planners are challenged to reassess and newly strategize the field. How do we proactively plan for the future in practice, research and education, with a long view about the role of planning while confronting today’s political challenges? Further, how should planners seek to communicate with conservative critics of planning? Might there also be ways of finding common ground on policy positions and narratives that speak to opposing actors across difference?

This Interface edition seeks to address these questions and related topics via the insights and writings of scholars who examine planning in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. Time, intergovernmental and citizenry conflict and waning public trust in government are omni-present in these contributions. So too are differing perspectives about the extent to which common ground is possible any more, or whether it is considered a worthwhile endeavor or just a devil’s bargain.

The questions of time and intergovernmental and citizenry conflict vary, however, as partisan conflicts between actors manifest differently across the cases and issues examined. Heather Dorries writes about the long view steeped in 400-years of conflict regarding the takings and efforts for reappropriation of Indigenous land in a Canadian settler history. This becomes crystallized through Dorries’ case examination of pipeline infrastructure that would cut through Indigenous land while simultaneously rupturing recent national efforts to confront the treatment of Indigenous people. Indigenous communities have engaged in a politics of refusal in opposition to this pipeline, spatially embodied in part by building ‘Tiny Homes’ in the pipeline’s proposed pathway. Dorries argues that alongside such a history, searching for common ground would be a bridge too far between the national government and First Nations, the latter of which have little trust in government. Rather, planners should seek to better understand such politics of refusal and make planning the object of analysis to consider how planning further subjugates communities in these contexts.

June Manning Thomas similarly argues that past histories and policies of racial exclusion affect current and future planning in older industrial cities and fragmented regions. She focuses on the case of Detroit, Michigan and its metropolitan region, where deepening disparities have raged over public investment and transportation infrastructure vis à vis wealthier white suburban areas versus lower income, communities of color in the central city. Thomas argues that conflict is context specific and that rigorous scholarship and education are needed to uncover the nuances of challenges and opportunities. To this end, she recommends that planners focus on traditional and non-traditional community driven strategies, geared towards self-sufficiency and tailored to varied contextual circumstances. She further argues that planners should hold steadfastly to values and professional ethics that support human flourishing when negotiating with others who hold differing perspectives or in times of resistance.

Willow Lung-Amam and Gerardo Sandoval in their contribution about immigration and sanctuary cities also look to ethics to guide grassroots advocacy. They feature intergovernmental confrontation in the U.S. but from a different perspective of time – short-term emergency responses to President Donald Trump and his administration’s implementation of deportations of undocumented workers, travel bans for certain immigrant groups and related challenging policies. The central questions Lung-Amam and Sandoval address are: what can planners do today under extreme circumstances and what can they do longer term to inform research and practice? To invoke Thomas’ call for specificity about context, these challenges come to the fore in “blue” (progressive) U.S. cities that have established sanctuary and welcoming cities for immigrants and that are now opposed by higher-level government in “red” (conservative) states and the current Presidential administration and federal actions.

Continuing with the theme of red states and conservative areas, Ann Foss draws from her dual vantage points as planning practitioner and scholar to consider the deepening partisan gap and intergovernmental conflicts with respect to confronting climate change. Through surveys of residents in the highly conservative area of Dallas-Fort Worth region in Texas, she finds that respondents from across the political spectrum are supportive in making personal behavioral and other changes to tackle climate change. Conservative elected officials and attendant governmental bodies are oppositional to such considerations. Further still, planners are publicly silent on the issue of climate change by not invoking the concept let alone its urgency when pursuing planning actions. As a result, Foss calls on planning education and research to laser in on addressing the day-to-day needs of planners working to address climate change in highly partisan contexts. This could include assistance, with the development of message framing for conservative audiences and creating planning narratives of common ground across the political divide. The challenge of climate change is that this global problem has dire consequences for the future but must be acted on locally, and in the present. The frustration is that political divides have blocked necessary agreements about a problem that affects all.

Framing and narratives of common ground to confront intergovernmental and citizenry conflict are also key themes of two additional contributions. In examining housing needs in England, Andy Inch examines ‘common sense’ cultural attachments to property, property rights and land development. He finds ideological tensions between, on the one hand, neoliberal market conservatism that promotes development in the name of the economy and regional needs for added housing, and, on the other hand, a protectionist conservativism as well as libertarianism that can be summoned to block development to preserve particular rural/semi-rural settings (see , Inch 19:4). Inch calls for further examination of the ideological to provide greater context for considering the larger structural opposition to planning. Parallel to Foss, he argues that planners should not shy away from better understanding ideologically-based worldviews wherein newly articulated positions may be developed and framed based on such analysis.

Table 1. Conservative orientations towards planning and development in England.

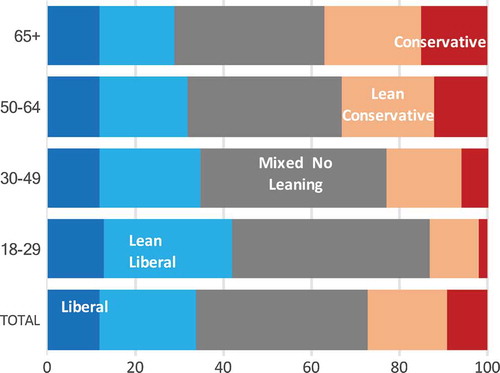

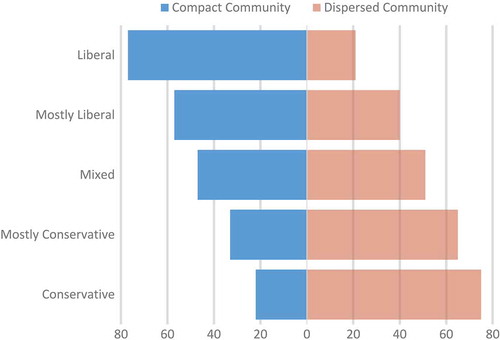

We, Karen Trapenberg Frick and Dowell Myers, similarly focus on ideological perspectives and argue that to tackle partisan and intergovernmental conflict in the current moment and into the future, planners should attend to the middle 40% of residents in the United States who do not align directly with political left or right. Whereas committed progressives and conservatives receive much public and political attention, planners and others provide little consideration of narrative appeals to those in the middle who could help turn the tide towards improving social equity for all. After delineating areas of potential common ground in planning between the middle, left and right, we provide recommendations for beginning to span the divide and build mutual trust on substantive and procedural matters. We suggest that fracturing and polarization of the citizenry and governments at all levels will continue without such efforts as each side seeks to conquer its enemy Other, only to see volatile swings in the balance of power.

Through these contributions, we hope this Interface sparks much spirited conversation and debate about the role of planning, and ways we can affect change for the social good, including at a featured roundtable at the 2018 Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning annual conference. No time is like the present for attending to today, moving forward with the future and reckoning with the past. The challenge to planners, as ever, is how to guide all the stakeholders to respect each other in coexistence on the same page, even while they advocate for different goals. Without building greater trust and communication of shared needs and common ground where possible, planners cannot secure the stability of decision making needed to improve social equity and promote long-term development and conservation projects that will require years of sustained commitment.

Notes on contributors

Karen Trapenberg Frick is Associate Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at University of California, Berkeley and Director of the University of California Transportation Center. Her current research focuses on the politics of infrastructure and conservative views about planning and planners’ responses. She is also the author of Remaking the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge: A Case of Shadowboxing with Nature (Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2016). Email: [email protected]

Dowell Myers is a professor of policy, planning, and demography in the Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California. He is author of Immigrants and Boomers (Russell Sage Foundation 2007) and other works that argue a mutual benefits strategy to span demographic divides. Originally schooled in anthropology, his planning theory ventures began with an internship with Paul Davidoff to open up the suburbs, followed by a course at UC-Berkeley when Mel Webber and Horst Rittel were newly writing their “Dilemmas” article about wicked problems. Email: [email protected]

Responding to the Conservative Common Sense of Opposition to Planning and Development in England

Sometime in 2016 a curious episode in English planning finally came to a close when Robert Fidler, a farmer from Surrey in the affluent south-east of the country, reluctantly set about demolishing the large family home he had built on his land. The case dated back to 2007 when the local planning authority for the area, Reigate and Banstead Borough Council, began enforcement action against Fidler for building without permission in the green belt. He appealed, arguing that his home had been substantially complete for more than four years when the action was initiated so the statutory time limit for prosecuting him had passed. But here’s the twist, and the reason this story gathered considerable national press coverage: Fidler had deliberately set out to hide what the media dubbed his ‘castle’, building it behind 40-foot high walls of straw bales that were only removed when he deemed the building was legally safe (see & ).

Figure 1. Robert Fidler’s house before the removal of straw bales. Source: Reigate & Banstead Borough Council.

Figure 2. Robert Fidler’s house after the removal of straw bales. Source: Reigate & Banstead Borough Council.

The case subsequently made its way through an administrative appeal and then successive legal hearings as Fidler exhausted the routes of challenge available to him. In these hearings the arguments revolved around technical interpretations of legislation, including whether a planning inspector was right to have rather artfully held that the building work was not complete until the last of the straw bales was removed. In the meantime, partly inspired by the public profile of this case, national government introduced new legislative provisions against attempts to deliberately deceive planning authorities.

What is most interesting about this story, for present purposes, is not the arcane detail of legal interpretation or legislative reform, but the way Fidler and some media commentators sought to frame his actions. Speaking in court after an initial legal challenge was overturned, he was reported as saying: “They say an Englishman is entitled to have his castle. I thought that maybe I could claim this to be my castle, and see if there was any mileage in that…” (Topping, Citation2010). Writing in the liberal-left leaning Guardian, meanwhile, the commentator Alexander Chancellor (Citation2010) expressed sympathy with Fidler’s cause:

Of all the restrictions on our liberties few are more oppressive than those imposed by local planning authorities. We may grudgingly accept the need for planning controls to save what’s left of our shrinking countryside, but the idea that an Englishman isn’t free to do what he wants with his own property is still widely resented. It offends against something in his DNA….

In these quotations, both Fidler and Chancellor appeal to deeply-held cultural attachments to private property rights. Associating the institution of property with freedom and liberty, they go so far as to position it at the heart of national identity. The oft-repeated proverb “an Englishman’s home is his castle” dates back to the 16th century and illustrates the extent to which understandings of private property have become sedimented into a peculiarly English common-senseFootnote1; ensuring that this deeply ideological construction seems so natural that its historical and political character are obscured (along with its complicity in perpetuating various forms of injustice).

There are family resemblances between Fidler’s libertarian attempt to be freed from state interference and those of the U.S. based property rights or ‘wise use’ movements that have gained considerable support over recent years. However, what is perhaps most striking is how much of an outlier a case like this remains in relation to the broader politics of planning in England. Attempts by citizens to assert private property rights against the legitimacy of planning law attract attention because they remain relatively rare. In this regard, whilst the United Kingdom’s decision to Brexit the European Union might be understood as part of a wider conservative-nationalist ‘uprising’ with parallels to right-wing populist developments in other parts of the world, the prevailing politics of planning in England have been more powerfully shaped by a different configuration of conservative political forces.

Conflicting Conservative Ideas of Planning: Preservationism vs. Neoliberalism

In keeping with the politics of the ‘home counties’ that surround London, Reigate and Banstead Borough Council who pursued the case against Fidler are led by a Conservative administration. Throughout, they maintained a strong defence of planning law and the protections it provides against unregulated development:

This was a blatant attempt at deception to circumvent the planning process, which particularly in the green belt is an important part of trying to protect the environment we live in… (Topping, Citation2010)

This quotation illustrates how the nationalization of development rights effected by England’s 1947 Town and Country Planning Act has come to be accepted as a legitimate, even necessary, form of state intervention in land and property. At first sight this may appear somewhat paradoxical from the perspective of a Conservative party that has traditionally stood as a defender of private property, individual freedom and a limited state.Footnote2 However, control against development and the powers it affords to preserve the villages, towns and (often mythical) open countryside of England’s green and pleasant landscape, has generated grassroots Conservative support for state intervention through the planning system. This support for planning is frequently characterised as a form of NIMBYism and perhaps mirrors commitment to exclusionary zoning controls in other parts of the world. However, it cannot be reduced entirely to the rational calculus of self-interested owners. The large membership of organisations like the Campaign to Protect Rural England and the National Trust are evidence that ideas of environmental and historical protectionism also find strong bases of support in the common-sense of English culture, and a tradition of “one-nation” Conservatism that stresses a paternalistic stewardship of the environment and society. Rallying cries to keep developers’ “hands off our land” or fight the “concreting over of the countryside” play on these attachments and the emotional investments they produce, generating sometimes fierce opposition to new development which can become a defining local political issue.

Over the past 30 years, the ascendency of neoliberal ideas has been in tension with this protectionist conservatism. Neoliberal critiques of planning have generated ideological and political pressure to deregulate state land-use controls and ‘free’ the forces of private enterprise to produce socially necessary development through the market. Ironically, by encouraging people to view homeownership as an important aspiration, and homes as (often increasingly valuable) financial assets, neoliberal ideology has also played a part in fomenting conservative political opposition to the market-led development it advocates. National governments, convinced that planning distorts the ability of the market to balance supply and demand, have therefore come into conflict with homeowning voters in places like Surrey who oppose deregulation in the name of strong, local planning control.

Rather than the anti-state libertarianism expressed by Fidler or some US based anti-planning movements, the politics of planning in England has effectively been framed by the struggle between these two different forms of conservative political thinking: a market liberalism that is broadly anti-state and anti-planning and an often localist protectionism that is anti-development but therefore supportive of planning control, in so far as it provides tools to block the developers. Whilst perhaps not as dramatically polarising as forms of conservative opposition found elsewhere, the interaction between these conservative tendencies has been powerful in shaping and delimiting prevailing approaches to planning. As illustrated in below, these different forms of conservatism are at times in tension. Political projects may therefore seek to rearticulate them in various ways, trying to hold them together, however uneasily. In doing so, they illustrate the capacity for conservative attitudes towards planning and development to take on diverse configurations in different times and places.

In England, as in many other parts of the Global North, this has recently been intensified by concerns about a ‘housing crisis’.Footnote3 The housing crisis has often been narrowly constructed as a failure to allow the market to build sufficient new housing to keep pace with need, generating powerful calls to further limit land-use regulation and weaken the power of localized opposition to prevent or delay development. Despite flirting with the rhetoric of localism, successive governments have used national policy to oblige local government to allocate increased amounts of land for private housing development, whether through the imposition of binding targets for numbers of new housing units, the specification of methodologies to calculate housing need, or the imposition of deregulatory policies that have weakened control at lower levels. As a result, the planning system in England has increasingly been defined by the overriding priority of pushing through sites for new housing irrespective of local political sentiment. Exacerbated by severe cuts to local authority budgets, this has arguably reduced the capacity of planners to win local political consent for, or positively shape, necessary development (Town and Country Planning Association [TCPA], Citation2018) whilst exacerbating the conditions that produce conservative opposition and undermine public trust in planning.

In certain respects, this dominant frame has been a very convenient shell for landowner and developer interests, allowing them to present their private interests as synonymous with the broader public interest in housebuilding, whilst deflecting political flak away from their own role in producing (and benefitting from) scarcity in land and housing (e.g. Edwards, Citation2015). Rather like the idea that the planning system presents a formidable barrier, conservative opposition to development may at times operate as a convenient scapegoat. This makes it important to carefully distinguish between its actual efficacy in blocking or delaying development and the political claims made about it by various actors. With planning permissions now running well ahead of rates of building, it seems increasingly clear that the narrow focus on planning and anti-development politics as a key source of constraint, has been at least partly missing the point. There are also emerging signs that the severity of the housing crisis, and particularly the threat that high housing costs will alienate younger generations from the core ideological promise of homeownership, may be beginning to change things. In the ferment created by Brexit and the rise in support for Jeremy Corbyn’s socialist alternative, opportunities may emerge to challenge the dominant configuration of conservative forces and the narrow ways in which they have come to define the politics of planning in England.

Building Support for Alternative Ideas of Planning

In this context, a key question for those interested in promoting alternatives to these conservative ideas of planning is how to respond to the current political moment?

In the sections above, I have sought to relate conservative understandings of planning in England to wider ideological positions and the ‘common sense’ of cultural attachments they have mobilized to secure support. I have therefore highlighted that a significant part of the necessary response to changing political realities rests at an ideological level. This is not to argue that conservative responses to planning and development can only be tackled once neoliberalism has buckled under the weight of its own contradictions or been toppled by counter-hegemonic insurgency. Rather, in drawing attention to tensions between different conservative orientations towards both planning and development, I have sought to highlight a terrain of potential struggle where political ideas, including prevailing definitions of planning, are produced and alternatives might be articulated and fought over. This rests on an understanding of political positions not as fixed beliefs but as fluid attachments that can potentially be reworked to produce quite different ways of thinking, relating and acting. I believe that political and ideological analysis can therefore be a valuable tool for planners at various levels.

In facing the challenges of practice, for example, it is important to understand how various forms of support and opposition for planning and development can be rooted in different worldviews. Being attuned to what matters and motivates people and to possible points of tension in their common-sense understandings, can open up possibilities to secure limited forms of agreement. For example, staunch opponents of new housing might be persuaded to support development by arguments that appeal to the future health of their family or community. This is where communicative planning theory has productively fixed much of its attention and remains an important and often politically unappreciated achievement of local planning practice.

However, drawing attention to the ideological is also important because it directs us towards the wider forces that both produce different variants of conservative opposition and frame the spaces of planning practice. I am concerned that this is a terrain that planners and their representative organisations have too often tended to avoid. This may be because they have viewed it as too political a space for a profession to contest, whether because they continue to cleave to a technical understanding of planning or are focused on pragmatically getting on with things at the coalface, even in circumstances that aren’t of their choosing. The English example clearly illustrates the dangers of such assumptions, as what Tina Grange (Citation2013) labels planners’ “acting space” has been gradually narrowed by conservative forces. Reasserting the planning project as a means of tackling major challenges like the housing crisis in ways that promote socially and environmentally just outcomes requires building political momentum for change; working on the terrain of people’s common-sense attachments to show how things could be different and how planning can be a positive part of that change.

Notes on contributor

Andy Inch is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the University of Sheffield, UK. His current research focuses on politics and ideology in planning, how planning engages with the future and relations between citizens and the state. Email: [email protected]

References

- Chancellor, A. (2010, February 5) Yes, furtively turning a cow shed into a castle was stupid of Robert Fidler, The Guardian. Retrieved May 24, 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/feb/05/robert-fidler-cowshed-mock-castle

- Edwards, M. (2015). Prospects for land, rent and housing in UK cities. London: Foresight, Government Office for Science.

- Gramsci, A. (2005). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Grange, K. (2013). Shaping acting space: in search of a new political awareness among local authority planners. Planning Theory, 12(3), 225–243.

- Shepherd, E. (2017, October 30) Continuity and change in the institution of town and country planning: Modelling the role of ideology. Planning Theory. doi:10.1177/1473095217737587

- TCPA. (2018). Planning 2020: Interim report of the raynsford review of planning in England. London: Author.

- Tait, M., & Inch, A. (2016) Putting localism in place: Conservative images of the good community and the contradictions of planning reform in England. Planning Practice and Research, 31(2), 174–194.

- Topping, A. (2010, February 3) Farmer loses fight to save home he hid behind hay bales. The Guardian. Retrieved May 24, 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/feb/03/farmer-castle-home-haystack-demolition

The Limits to Negotiation and the Promise of Refusal

Strategies to foster collective deliberation have long been a defining feature of progressive planning. The civil rights movements of the 1960s ushered in new approaches to planning, including advocacy approaches and participatory methods designed to reposition the public as drivers of planning decision making. Later, communicative planning emerged, and defined a set of principles that might guide the planner in shaping public deliberation. Rejecting the flawed premises of communicative approaches, both consensus building and agonism have been positioned as an alternative to communicative rationality.

While these approaches may differ in many ways, public engagement remains a core goal of progressive planning practice. Agonism, consensus building, and communicative approaches share in common the belief that public input is part of good planning practice. According to such approaches, the success of planning projects can be measured by the extent to which planning is able to generate public support for planning initiatives. Consequently, growing political polarization might be seen as a barrier to planning, and an obstacle to generating the broad support for planning that a participatory ethic requires. Thus, proponents of such approaches might ask how planning can cultivate common ground in the context of increasing political and social polarization. But, is overcoming political difference always warranted? Are there instances where an attempt to bridge ideological divides might actually be a bridge too far?

The Canadian context provides some food for thought, and points towards the stakes of cultivating common ground in contentious political circumstances. In May 2018, the Canadian federal government announced that it would purchase the beleaguered Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline project for $4.5 billion Canadian dollars (CAD). Once completed, the pipeline will transport crude oil from the tar sands in Alberta to the west coast of British Columbia (BC). The total cost to complete the pipeline has been estimated to be as much as $7.4 billion CAD (Harris, Citation2018).

The federal government cites national and economic interests in defending its decision to purchase the pipeline. One journalist has suggested that the true reason the Canadian government has purchased the pipeline is to avoid a lawsuit from Chinese investors. The Canada-China Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection agreement, signed by Canada and China in 2014, guarantees that a pipeline will be built from Alberta to BC, a boon to significant Chinese investments in Alberta’s oil sands (Livesey, Citation2018). The potential for such a lawsuit is real. In 2016 TransCanada Oil sued the US government for $15 billion US dollars (USD) after the Keystone XL pipeline was cancelled (Tucker, Citation2016). While the motivation for Canada’s decision to purchase the pipeline may be murky, the advantages the decision yields for private interests are much clearer. The benefit for Kinder Morgan is obvious: the company is able to walk away from a project that has been continually threatened by lawsuits from First Nations and environmental groups while still making a tidy profit.

Indeed, the pipeline has faced significant opposition. The Province of British Columbia, along with many Indigenous communities, and environmental groups oppose the project, not only due to the threat to mountain and coastal environments posed by spills from the pipeline or from tankers, but also point to the fact that increased transport capacity provides incentive for the expansion of Canada’s tar sands, which are the largest contributor to Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions.

The pipeline cuts through the territories of 130 Indigenous communities. 14 communities are currently engaged in a lawsuit claiming that the planning process for the project failed to honour the constitutionally mandated requirement to consult and accommodate Indigenous rights in such projects. At the same time, 43 communities have signed benefit agreements with Kinder Morgan (Jang et al., Citation2018). Although some communities have voiced support for the pipeline, citing the potential for economic growth which pipeline construction might bring to their communities, not all communities that have signed benefit agreements endorse the project (Paling, Citation2018). Rather, some community leaders have said they felt these agreements provided the best option for their communities, given that the pipeline was likely to be built regardless of how they felt about it.

The decision of the federal government to purchase the pipeline despite strong Indigenous opposition is surprising in light of the discourse of reconciliation that has shaped Canadian politics in recent years. The negotiation of relations between Indigenous peoples and settlers has been on the political agenda since before the founding of Canada. While past approaches have been defined by overt attempts at assimilation, and marked by the cultural genocide of the residential school system, which ran from the 1880s until 1986, more recently, a discourse of reconciliation has dominated public discourse in Canada, characterized by an acknowledgment of Canada’s history of colonialism, and increased discussions concerning the recognition of Indigenous rights. In 2008, the federal government apologized for its role in the residential school system, and submitted to a court settlement which ordered it to investigate the system through a public commission. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded its work, and released a set of 94 Calls to Action designed to radically re-orient relations between Indigenous peoples and Canada along with its final report. The federal government committed to implementing all recommendations within the report.

For Indigenous communities across the country who experience dire conditions, including a lack of access to clean water or adequate housing, the promise of reconciliation rings hollow in the light of this decision to purchase the Trans Mountain Pipeline. Many have pointed out that the same funds now earmarked for this project would have been more than money enough to resolve the drinking water crisis in Indigenous communities across the country, and see this decision as a betrayal of the promises of reconciliation made by the current federal government. Thus, it is not surprising that the decision to purchase the Trans Mountain pipeline is being viewed as a “declaration of war” (Secwepemcul’ecw Assembly, Citationn.d.). Many are anticipating yet another summer of protest, featuring blockades and other forms of direct action in response to this decision.

The plan to purchase the pipeline reveals a set of unexpected alliances. Environmental and Indigenous groups opposed to the pipeline are now joined by a host of right-wing organizations, such as the Canadian Taxpayers Federation, which condemns the expense associated with the nationalization of the pipeline. On the other hand, pipeline advocates may attempt to reposition the project as part of the reconciliation agenda by promoting Indigenous equity stakes in the pipeline. But what does this mean for planning? I suggest that rather than focusing on opportunities to unite divergent interests this situation presents, that resistance to the Trans Mountain Pipeline might provide greater lessons for approaches to planning that place a premium on conflict resolution, consensus, or collaborative deliberation.

In the fall of 2017, members of the Sewepemc Nation, which lies in the path of the pipeline, began constructing tiny houses in the pipeline’s path, and are now pledging to build more. Now known as the Tiny House Warrior Project, this action is more than a strategy of dissent or physical manifestation of an ideological impasse; it also symbolizes the persistence of Indigenous life in the face of forces that seek to destroy it. As they explain: “This is one of the most serious threats to our Territories. We have never provided and will never provide our collective free, prior and informed consent - the minimal international standard - to the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline Project” (Tiny House Warriors, Citationn.d.). Thus, the Tiny House project signals a refusal to negotiate, the rejection of a politics of compromise, and thus points to a politics beyond deliberative approaches to planning.

For Indigenous political theorists, the discourse of reconciliation is regarded as little more than a ruse designed to secure the political and moral coherence of Canada as a settler nation, and fails to dramatically alter the colonial nature of Indigenous-Canada relations. In this context, the rejection of discourses of reconciliation, which emphasize finding common ground, is more than a stubborn refusal to participate in a program of reconciliation, but signals an alternative strategy, which reflects Indigenous political aspirations. Audra Simpson offers the concept of refusal as an alternative to processes premised on state recognition, and as an analysis which reveals the structures of colonialism. Refusals are not only an act of resistance but also theoretically generative as they “tell us something about the way we cradle or embed our representations and notions of sovereignty and nationhood; and they critique and move us away from statist forms of recognition” (Simpson, Citation2014, p. 113). Similarly, Glen Coulthard observes that an unwillingness to get over the past is actually a “politicized expression of Indigenous anger and outrage directed at a structural and symbolic violence that still structures our lives” and argues that “the emergence of negative emotions like anger and resentment can indicate a break down of colonial subjugation and thus open up the possibility of developing alternative subjectivities and anticolonial practices” (Coulthard, Citation2014, p. 115).

There are many cases in which agonistic debate and processes which bridge ideological divides may be the best planning strategy. Planners have the tools to encourage agonistic debate. But what can be learned when these processes are refused? Progressive planning has frequently made justice its object. Indeed, multiple forms of justice—environmental justice, social justice, spatial justice—have been posited as plausible outcomes of planning action, and as important objectives for planning activity (Agyeman, Bullard, & Evans, Citation2003; Carmon & Fainstein, Citation2013; Soja, Citation2010). Advocacy planning, community planning, communicative planning, Indigenous planning, and other forms of progressive planning have all taken the promotion of justice as their key objective. However, positioning justice as the object of planning allows planning to divorce itself from a discussion of how planning is implicated in practices and processes that produce injustice. While a desire for justice may ‘justify’ planning action, this desire does not require planning itself to be placed at the centre of an interrogation of the causes of injustice. This orientation thus limits the lines of inquiry and action that planning might pursue, by training our attention on a set of outcomes—such as consensus—rather than forcing us to reflect on the conditions which precipitate polarization in the first place.

For planning research and teaching, this means that planning scholars make their own practices their object before embarking on an errand of promoting consensus. As long as planning’s own practices continue to shore up systems of inequality that give rise to political and social polarization, planning cannot begin to bridge ideological gaps. The existence of starkly divergent positions might be viewed as symptomatic of the stakes of these positions, rather than as barriers to planning. Questions about how planners can foster a politics of alliance, and the extent to which planners can intervene in order to bridge political polarization are important; these questions speak to the deeply political work of planning in shaping social relations, and are central to the ways that planners might facilitate the participation of diverse communities in planning processes. The example presented here could be viewed as an opportunity to consider how diametrically opposed groups unite around common interests. However, it is also an opportunity to consider the limits of alliance building, and to consider the possibilities an ethic of refusal holds for planning theory.

Notes on contributor

Heather Dorries is an Assistant Professor at Carleton University where she teaches in the Indigenous Policy and Administration Program. She received her MScPl and PhD in Planning from the University of Toronto. Her research on focuses on the ways that urban planning mediates relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. Email: [email protected]

Planning Contexts in a Hyper-Polarized World

In the U.S., the rise of strong conservatism has shaken up many ideas about government and planning, with a push toward small government, localism, and property rights and with weak support for environmentalism, regional strategies, or social welfare programs (Aberbach, Citation2015; Berry & Portney, Citation2017; Lewis, Citation2014; Trapenberg Frick, Citation2013). Anti-immigrant sentiments and overt signs of nationalism and racism challenge beliefs about the need to plan well for cities and regions of harmonious diversity.

Planners experience varying effects of repression or opposition because of increased polarization. At the national scale, environmental standards, housing programs, and support for mass transit options teeter on the edge of viability, but visible battles may also take place at the state, regional, and local levels. Conservatism has had an impact in some states for many years, as for example with tax limitations and government cutbacks without protection for public services. Working for a homogeneous political constituency, however, planners for isolated and prosperous suburbs could feign neutrality, in spite of obvious contradictions. In some regions, ideological difference is enshrined in political boundaries and exclusionary practices; no local confrontation is necessary.

Consider two possible examples of alternative contexts where increasing conservatism could affect planners and their communities. In metropolitan regions where income and racial inequality are pronounced and where political boundaries institutionalize separation, challenges emerge most clearly with regional planning. A second context could be distressed central cities, such as older industrial cities (OICs) lacking resources because of long-term effects (Berube & Murray, Citation2018). These call for different approaches to practice and research.

Regional Contexts

The region is a particularly apt place for battle lines in the U.S. Unified metropolitan governments are rare, and the tradition of localism has allowed municipalities to form in a balkanized way, divorced from regional consciousness. Particularly with plans for creating or improving regional transit systems, region-wide support is often necessary, but proposals for funding such systems can run into entrenched opposition from property-rights and minimal-government advocates.

Some strategies have overcome such hyper-polarization, with groups cooperating across the political spectrum. The concept of agonism, used to help theorize some of this work, suggests that building coalitions by finding common ground among such diverse interests, for either short- or long-term efforts, is one way to plan within such a context (Trapenberg Frick, Citation2013, Citation2018). This approach is very close to the main argument of communicative planning and to related strategies for mediation that counsel overcoming difference through various forms of guided dialogue and building of mutual trust, with evidence that this can work even in difficult situations (Forester, Citation2009; Innes & Booher, Citation2010). With the contemporary tone of politics, however, antagonism—the opposite of agonism–has sometimes reached a fevered pitch, making both communication and cooperation difficult (Roskamm, Citation2015). Another issue is that existing case studies are often of exceptional situations, such as ballot proposals that come only every few years, if at all. In the ordinary, low-profile, daily work of regional cooperation, such as by supporting open and affordable housing or financing existing transit systems, matters may easily settle into old borders.

Metropolitan Detroit offers an example of how habitual isolationism can affect larger initiatives. A key factor here is that metropolitan Detroit is one of the most racially estranged, hyper-segregated regions in the country; local exclusion is an embedded characteristic of the political fabric. This area has operated for some time with two essentially separate bus systems, city-sponsored Detroit Department of Transportation (DDOT) and the suburban Southeast Michigan Transportation Authority (SEMTA); this left many central-city residents (largely blacks) poorly served and unable to reach suburban jobs. In 2012, pressured by U.S. DOT Secretary Ray LaHood, the state government finally created a new Regional Transit Authority (RTA) (Lowe & Grengs, Citation2018, p. 6). Although this action was a major accomplishment in an area that had failed to create a unified system after many attempts, RTA funding was dependent on the voter approval of four counties. In the fall of 2016, those voters narrowly defeated a millage proposal to fund the RTA’s regional transportation plan, which included a unified system with light rail, commuter rail, bus rapid transit, and improved bus lines. Surveys carried out before the vote revealed strong differences in opinion about the viability of a RTA based on the respondents’ home county. Detroit’s Wayne County was largely in favor, as was Ann Arbor’s Washtenaw County. The prosperous, isolationist Oakland County and the more working-class Macomb County, however, revealed citizen opposition along ideological lines. Likely ‘no’ voters were apt to pick the following options, clear markers of conservative thought: “I do not trust my tax dollars will be spent effectively by the government,” and “I do not want my tax dollars to pay for public transit“ (Bernasconi, Zhong, Hanifin, Slowik, & Owens, Citation2015, pp. 25–26). RTA funding opponents recognized that some people needed transit, particularly inaccessible for low-income Detroit residents, but they did not want to pay for it. Coalitions formed of supporters, including Transportation Riders United, a citizen advocacy group, and regional business interests, but opponents were organized as well, citing financial concerns and localism rights.

Research that helps to illumine how to overcome entrenched opposition in high-profile cases, particularly in regions highly fragmented by race and socio-economic status such as this, will continue to be useful. We also need to know more about the specific elements of coalition-building or interest group mobilization that proves to be most effective as a form of strategic savvy that builds on activist tradition (Alinsky, Citation1989; Benveniste, Citation1989). What strategies can weaken invested and privileged self-interest besides more appeals to self-interest? How is it possible to address the low-profile estrangement, segregation, and isolation that affect everyday life as well as infrequent regional decisions?

Central-city Contexts

In some older industrial cities, the OICs, isolation and marginalization are so profound that the latest wave of political conflicts may seem to make little difference. The issue in such cities is not how to respond to rising conservatism but rather how to survive in deepening backwaters of neglect and decline that twentieth-century policies and attitudes have caused.

In Michigan, for example, several central cities have languished for years because of historic highway-based decentralization, federal policies such as Federal Housing Administration and Veterans’ Affairs mortgages, unenforced civil rights laws, and home rule and annexation laws that fragment governance. Contemporary conservative-driven actions include steady defunding of municipal governments along with limits in their ability to raise tax revenues; refusal to build up human capital in the face of deindustrialization; and the studied indifference of the state legislature to the poverty, racial segregation, and deteriorated public services that confront the state’s OICs. These trends are not distinct from the rising tide of conservatism, because such politics led to recent decisions such as ignoring the water crisis in Flint or pushing several OICs toward emergency financial managers. These are not circumstances, however, that are of recent origin, or that negotiation or temporary coalitions can solve. They are structural, with origins that date back many decades. Recent manifestations of conservative national or state policies—for example, stemming the foreign migration that helped rescue selected city neighborhoods—simply deepen the oppression.

In such contexts, even projects that appear to bring relief are suspect. In the Detroit transit case mentioned above, while debate over a regional system was raging, strong regional business interests were funding and pushing forward a pet trolley project in the middle of the ‘revitalizing’ central city. The three-mile trolley, now called Q-line, was supposedly the beginning of a regional transit system, but aimed to connect the central business district with office complexes in the New Center area using a transportation mode that urban elites found acceptable and would use (unlike buses). Q-line has not formed a good basis for a regional light rail system, in part because of its curbside design, and it shows that even a public ‘good’—mass transit—can evolve to support a neoliberal social order that further isolates the elite from the larger population, the disadvantaged, and regional needs (Lowe & Grengs, Citation2018). Understanding how this is possible will continue to be an important research topic, and this will need to reference the considerable urban theory—concerning growth coalitions, the entrepreneurial city, etc.–that predicts and analyzes similar circumstances.

While both practice and research aiming to improve the lives of vulnerable people living in OICs may not directly address the raging context of conservatism and polarization, they are realistic ways of continuing to do the work of planning in the ruins that historic conservative policies have created. In particular, planners could elevate the importance of work such as analysis and implementation of local transit equity, equal housing opportunity, inclusionary zoning, environmental justice, and neighborhood planning. Understanding how to protect access to public services for underrepresented minorities and low-income people is a research topic with endless potential.

Implications

So contexts are important, some more than others, in considering practice and research responses to the rise of citizen conservatism. Fragmented regions and distressed OICs offer two examples of potential concerns. The framing here was southeast Michigan, but the same two typologies in other U. S. states could suggest other issues. So too could different contexts such as small towns, suburban enclaves, less fragmented metropolitan areas, and varied locations in countries–ranging from the U. K. or Sweden to South Africa and beyond–with weakened planning institutions or strong neoliberalism driving urban development (Grange, Citation2017; Tait & Inch, Citation2016; Watson, Citation2014). In such diverse places, what are the commonalities?

For planners, students, and researchers concerned about current trends of conservatism, nationalism, and inattention to social equity, the need to maintain clarity of vision is important. This requires holding fast to core values about the human condition, such as in John Friedman’s “good city,” including respect for “human flourishing” of innate intellectual, physical, and spiritual potentialFootnote1; transparent and fair governance; adequate housing and public services; and access to remunerated work if desired (Friedmann, Citation2000). Such values, which may be enshrined in professional codes of ethics, would apply whether negotiating with people of differing opinions or exploring means of constructive resistance through practice or research.Footnote2

Even with diligent attention, however, the challenge is great. Strong ethnocentrism, privilege, and power now buttress conservative themes of localism, small government, and property rights, and with such power come varying forms of negligence, marginalization or oppression that may make countervailing efforts seem to be moot. Since this is the case, it is timely to focus research and practice on analyzing non-traditional options for improving cities, such as tactical urbanism, makeshift cities, or living ‘off-grid.’

For people in severely-neglected communities, this also means studying possibilities for self-driven action such as classic community development or “insurgent survivalism” writ large as a partial solution (Roberts, Citation2018, p. 285). To do so is, in some ways, a throwback; decades-old claims that people through community development could bring themselves out of poverty and economic oppression, even in the context of uneven power and structural inequality, proved overly optimistic and misleading. Yet in a world where social nets are shrinking, it may be necessary to revisit the concept of self-sufficiency as a means of survival and fulfillment. Needed now, particularly in distressed areas, are such strategies as building up ‘human flourishing’ through various means (such as intense neighboring, local service, and bonding), community-driven supplemental education of children and youth, bartering or sharing, micro-enterprise, and community agriculture. Having in place a coherent framework for action, purposeful goal-setting, and community-driven social and economic development would aid such strategies; this has been a hallmark of superior faith-based initiatives (Lowe & Shipp, Citation2014; Thomas, Citation2017). Research that helps us find, analyze, and understand such efforts and their potential may offer a wider array of compensating strategies in a hyper-polarized world than now seem to be available.

Notes on contributor

June Manning Thomas, Urban and Regional Planning Program, is Mary Frances Berry Distinguished University Professor at the University of Michigan. She writes about diversification of the urban planning profession, planning history, social equity in neighborhoods, and urban revitalization, particularly for Detroit, Michigan. Her books include the co-edited Urban Planning and the African American Community: In the Shadows (Sage, 1996), and Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997, second edition Wayne State University Press, 2013). Other books include the co-edited, Margaret Dewar and June Thomas, The City after Abandonment (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), and the co-edited June Thomas and Henco Bekkering, Mapping Detroit: Evolving Land Use Patterns and Connections (Wayne State University Press, 2015). Email: [email protected]

A Right to Sanctuary: Supporting Immigrant Communities in an Era of Extreme Precarity

Sanctuaries are places we go to recover a sense of safety and security amidst environments of extreme precarity. They lie in the quiet corners of churches, among the stacks of local libraries, in public parks and schools, and around kitchen tables filled with the scents that call to home. For an increasing number of economic, political and climate émigrés whose communities have been crippled by violence, poverty, and environmental devastation, such places of banal sanctuary are in high demand, yet increasingly hard to find on American soil.

Since the ascent of Donald J. Trump to the most powerful political position on the globe, U.S. immigration policies and rhetoric have pivoted—heightening the precarious position that immigrants have always held in the body politic and imagination of the nation. The reversals have been epic. From Obama-era policies that guaranteed sanctuary to nearly 800,000 undocumented young adults and children, to those poised to defer the dreams of an entire generation and cut federal funding from cities that refuse to use their resources to do the work of federal immigration officers. From over a half century of policies that diversified immigrant populations, especially among those from non-European countries, to those that have all but banned émigrés and refugees from several majority-Muslim countries in Africa and the Middle East. From decades in which increasing immigration and economic prosperity went hand-in-hand, to proposals to dramatically cut the number of green card holders to historic lows. From policies that limited prioritized deportations to immigrants with serious criminal convictions, to those that have increased detentions and separated families on an increasingly militarized southern U.S. border and prioritized deportations for those with offences as minor as a traffic ticket. Even immigrants arriving with professional degrees to take jobs in high-tech firms face an uncertain future under an administration that has shown little commitment to extending visas to those with skills in short supply in the U.S. These new measures corresponded with an increase in hate crimes towards immigrants and people of color and fear among communities most vulnerable to the shifting political winds.Footnote1

How can planners carry out their longstanding efforts and obligations to advance equitable processes and policies in the face of such profound reversals of federal policy? How can and should planners respond to the current political climate around immigration and immigrants through their research, practice and education? The present politics have heightened the role of planners in helping to secure sanctuary for immigrants. With the federal government all but abdicating its responsibility to protect its most vulnerable denizens, local spaces that can act as bulwarks against far right, nativist policies and practices are more important than ever. We argue that a ‘middle ground politics’ of planning for immigrants is not one forged through consensus with the far or center right, but one that claims a right to sanctuary as a central ethos of planning in service of social justice and the public interest. Professional ethics require planners to “seek social justice by working to expand choice and opportunity for all persons, recognizing a special responsibility to plan for the needs of the disadvantaged” as well as “urging the alteration of policies, institutions, and decisions that oppose such needs” (American Institute of Certified Planners, Citation2016). In today’s context, this requires creating and protecting spaces of immigrant sanctuary at the local level and particularly within the public sphere.Footnote2 This article provides ways of understanding the contemporary politics of immigrant precarity and how planning can help to advance and secure a right to sanctuary.

Between Love and Loathing: The Changing Politics of Immigrant Precarity

Immigrants, particularly those of color, have long held a precarious place in the national narrative. While founded as an immigrant nation, its stratified social order that privileges whiteness as the basis of claims to property and citizenship has long presented a deep contradiction (Lipsitz, Citation2006). Indeed, while the rhetoric of acceptance, inclusion, and the right to sanctuary run deep, the realities of a nation built on Manifest Destiny that denied Native Americans claims to the land and non-Europeans the rights and title of citizen, has tainted the young nation from the beginning. To be an American, was initially to be white, male, and a property owner—and to be a lawful immigrant was to be European.

Though the definition of citizen has changed over the decades, exclusions remain. The passage of the 1965 Immigration Act was a watershed moment in which immigrants from non-European countries were given more equal treatment, leading to a stream of the most diverse immigration that the U.S. had ever seen. This radical transformation was neither entirely expected nor welcomed. In bill after bill since, Congress has undermined its impact, prioritizing educated, skilled immigrants and creating an ever more economically and racially bifurcated system with a more exclusive path to citizenship (Pastor & Mollenkopf, Citation2016; Vitiello & Sugrue, Citation2017). In doing so, they have made ‘illegal’ many would-be Americans that fall outside of the increasingly narrow definitions.

In the past several decades, immigrants, both documented and undocumented, working class and wealthy, have faced heightened levels of precarity—lives without the promise of stability (Millar, Citation2017). As immigrants and refugees have settled in new places, particularly in new and emerging gateways in the American South and Sunbelt, their presence has raised white nativist fears over the loss of their privileged position in the social and economic order (Mollenkopf & Pastor, Citation2016). Historically, during periods of increased economic, social, and political change, immigrants have served as the scapegoats and targets for nativist fears, around issues such as taxes, job competition, and crime (Martinez & Valenzuela, Citation2006). These fears have become especially deep in recent decades with the erosion of the welfare state, globalization, the Great Recession, the ‘browning of America,’ and the election of the first African American U.S. President. As violence against immigrants, arrests and deportations have exploded in the Trump era, immigrants have increasingly struggled to claim a legitimate place in the nation. Indeed, the Trump Administration’s immigration policies suggest a throwback to the pre-Civil Rights era that threaten to undermine the slow, but steady gains made in the last several decades towards a more just and equitable immigration system.

The City as Sanctuary: Planning’s Response to the Anti-Immigrant Climate

National problems are often fought out in local spaces. From struggles over day laborers in exurban Washington, DC (Price & Singer, Citation2008) to the building of so-called McMansions in Silicon Valley (Lung-Amam, Citation2017), planning is deeply invested in the ways that immigration politics are fought. In the current climate, far right, nativist, anti-immigrant policies at the national level are overrunning the desires of the many local communities that do not support them. Planners can be neither passive nor neutral in such debates. Equitable process and outcomes require planners to advocate for an awareness of identity politics and different cultural practices, and the engagement of marginalized groups in decision-making processes (Krumholz & Forester, Citation1990; Young, Citation2011). In today’s immigration climate, this suggests standing with communities that are actively pushing back against national policies and other local efforts to promote community building and social inclusion. It suggests that planners need to help link national politics to local planning, promote welcoming cities, support sanctuary cities, and secure public spaces and forums as part of broader claims to a right to immigrant sanctuary.

Planners need to show how national immigration policies are intertwined with local planning. Increasingly punitive and conservative national immigration policies have increased fear and a sense of precarity in communities in which planners work, making engagement in planning processes more difficult. Planners need to be partners, rather than adversaries, in the fight for immigrant rights. Planning ethics and equity calls upon scholars, educators, and practitioners to challenge the conditions that create a sense of illegitimacy and illegality in communities (De Genova, Citation2002; Kim, Levin, & Botchwey, Citation2017; Maldonado & Licona, Citation2007; Miraftab, Citation2016; Miraftab & McConnell, Citation2008; Sandoval, Citation2013). For instance, many local governments have built strong partnerships with community-based organizations to provide documented and undocumented residents with a range of services, such as tax preparation, child care, and workforce training (Katz & Bradley, Citation2013). Planners also have an interest in creating a more fair, just, and comprehensive immigration policy that addresses issues such as the rights of low-wage immigrant workers to better pay and safer labor conditions, and providing undocumented immigrants with a path to citizenship.

To combat the politics of fear and exclusion, planners can actively promote welcoming spaces. Instead of building walls, many cities have invested in plans and policies to attract and support immigrants. Through networks like ‘Welcoming Cities,’ municipalities like Dayton, Ohio and various community-based organizations in many cities are creating more inclusive climates for immigrants (Butler, Flora, & Tapp, Citation2000; Grey & Woodrick, Citation2006; Harwood & Lee, Citation2015; Rios & Vazquez, Citation2012). Common policies include those that support immigrant businesses and entrepreneurship, bilingual signage, language access to city documents, immigrant supportive services, cultural festivals and events, and friendlier platforms and institutions for public engagement. Some have adopted stringent anti-discrimination housing policies and advocated for immigrant-friendly laws at the state and federal level.

Planners must also support communities that help immigrants feel safe. From New Orleans to New York, cities, counties, and even states, such as California, have refused to allow law enforcement agencies to collect or share information about residents’ citizenship status or provide detention spaces for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Gonzalez, Collingwood, & El-Khatib, Citation2017; McDonald, Citation2012). Many areas have also adopted regulations to ensure that landlords will not discriminate based on the citizenship status of their tenants, and that better records are kept of the human and civil rights violations committed in their jurisdiction (Ridgley, Citation2008). Likewise, several U.S. colleges and universities have adopted sanctuary campus policies. Provisions for counseling, legal, and other supportive services for undocumented students, and policies that ensure that universities do not share students’ citizenship information are critical to providing a safe learning environment. Under the Trump Administration, municipalities and campuses that have pushed back are at risk of losing federal funds. Planners hold interests not only in protecting such funding, but also in ensuring the communities and students with whom they work feel safe to participate in public life and decision-making.

Towards those ends, planners can also help to ensure greater access to public spaces and forums of public engagement. The past few decades have seen an assault on the public sphere. Neoliberal economic policies have promoted the increasing privatization and securitization of the public realm (Davis, Citation2006; Mitchell, Citation2014). Today, the public domain is a space of heightened fear around police violence and hostility for immigrants. Planners are critical to ensuring a sense of safety and inclusion for all occupants of public space (Sanchez, Plata, Grosso, & Leird, Citation2010; Vitiello & Sugrue, Citation2017). They also play an important role in advocating for open forums of public participation beyond planning (Sandoval & Rongerude, Citation2015). In Chicago’s 49th Ward, for example, participatory budgeting has increased the engagement of low-income Latino immigrants in local government by creating safe spaces for Spanish speakers to interact directly with their district alderman (Meléndez, Citation2017).

Towards a Middle Ground Planning Politics of Immigration

Immigration and politics of sanctuary cities have long been neglected in planning scholarship. But in today’s anti-immigrant climate, planners’ skills and perspectives are vitally needed. Whether documented or undocumented, refugees and immigrants have a “right to the city” that is not simply about access to public space or representation (Mitchell, Citation2014). It also includes the right to feel safe in their spaces of everyday life. In shopping centers, schools, parking lots, and public parks, immigrants rely on spaces of everyday sanctuary for a sense of safety and belonging. As the fear and loathing of immigrants takes on new forms at the national level, planners must use their research, practice, and teaching to stand up for the right to sanctuary as a core planning principle.

While not relenting in taking the federal government to task to uphold their responsibilities for the safety and security of its residents, planners need to actively work in spaces in which they have the most influence and strategic possibility. Notably, far more has been accomplished at the local level and on the legal front on issues such as fair and affordable housing and sanctuary city protections in recent years than at the federal level or through public policy. Further, more has been accomplished on the streets than in the halls of Congress. Social movements, such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #NeverAgain have linked issues of racial justice, gender equity, and gun violence to immigration policy and immigrant rights. Indeed, while the politics of immigration are dire, they are also hopeful. Every day, more and more communities are declaring themselves sanctuary and welcoming cities. Planners need to support and build on these efforts to support immigrant integration, challenge the criminalization of migration, and push for a recognition of the right to sanctuary.

This may sometimes require planners to actively weigh the costs and benefits of short-term responses to immediate crises and the long-term goal of building more equitable, inclusive communities. Planners are vitally needed to respond to crises, such as increased deportations as well as forced detentions and separation of families at the border. Planners can map the location of federal detention facilities, engage migrants and local communities in developing alternative plans for their temporary or permanent settlement, and push new local policy responses. However, planners’ efforts are also needed to build the capacity of communities to adopt longer-term policies and plans that promote welcoming and sanctuary cities. While planners have become more engaged in the latter in recent years, research is needed to better show how planners can work effectively on both fronts simultaneously.

A middle ground politics of immigration need not be about compromising the profession’s most valued and ethical obligations to secure the basic rights and freedoms of communities. It instead charges planners to make strategic choices about the best levers to pull, particularly during times of heightened precarity when the choice sets are constrained from the top. It is a time to switch, not abandon, tactics and principles. It is a time to redirect efforts to those in which we can build momentum and coalitions.

Notes on contributors

Willow S. Lung-Amam, Ph.D. is Assistant Professor in the Urban Studies and Planning Program and Director of Community Development at the National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her scholarship focuses on the link between social inequality and the built environment. She is author of Trespassers?: Asian Americans and the Battle for Suburbia (University of California Press, 2017) and has written extensively on immigrant suburbanization, equitable development, gentrification, suburban poverty, and geographies of opportunity. Email: [email protected]

Gerardo Francisco Sandoval is an Associate Professor in the Department of Planning, Public Policy, and Management at the University of Oregon. His research focuses on the roles of immigrants in community regeneration, the urban planning interventions of governments in low-income immigrant communities, and the transnational relationships that exist within immigrant neighborhoods. Dr. Sandoval’s books include Immigrants and the Revitalization of Los Angeles: Development and Change in MacArthur Park, and the co-edited Biking Justice and Urban Transformation: Biking for All? Dr. Sandoval has published in journals focused on urban planning and community development such as the Journal of Planning Education and Research, Urban Studies, Community Development, and the Journal of Urbanism. Email: [email protected]

Planning and Climate Change: Opportunities and Challenges in a Politically Contested Environment

Climate change is often referred to as a ‘wicked problem’ (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973): it is complex, has interconnected causes and impacts, is a long-term challenge, and is difficult for many to understand on local, short-term levels. While the scientific community agrees that anthropogenic climate change is happening and is a global emergency (Cook et al., Citation2013), in the United States and some other countries, it is also fiercely contested and partisan. U.S. polls consistently reveal that those who identify as democratic or liberal are more likely to believe climate change is happening and that it is caused by human actions, compared to those who identify as republican or conservative (e.g. Kiley, Citation2015; McCright & Dunlap, Citation2011). Additionally, rather than seeing this partisan gap closing, polls show the gap widening, signaling that climate change is a political debate that becomes ever more polarizing and entrenched.

This partisan gap can also be seen in the actions of local governments and regions across the U.S. Liberal regions, as well as those affected by tangible climate change impacts, such as coastal regions grappling with sea level rise and increased storm intensity, are taking more steps to address climate change, including joining global climate organizations, adopting climate action plans, and instituting policies aimed at mitigating and/or adapting to climate change. One example of this divide is seen in the politics of the municipalities that have signed the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, which is a commitment to try to meet the Kyoto Protocol targets and enact policies addressing climate change. In the liberal Seattle region, which has a population of just over 4 million people and 82 municipalities, approximately 35% of mayors signed the agreement. By contrast, in the conservative Dallas-Fort Worth (DFW) region, which has a population of 7.4 million people and 242 municipalities, only 6% of mayors signed the agreement. While signing this agreement does not necessarily translate into climate action, it is a public declaration of the reality of climate change and the intent to take actions to address it.

Planners, who are trained to work on complex, long-term, and partisan issues, should be a natural fit to help communities mitigate the causes of climate change and adapt to the effects, through land use, transportation, and environmental plans, policies, and actions. However, research and experience suggest that planners in politically conservative regions do not address climate change for a variety of reasons (Foss, Citation2018a; Foss & Howard, Citation2015; Gerber, Citation2013; Hamin, Gurran, & Emlinger, Citation2014). The Dallas Fort Worth (DFW) region of Texas is the fourth most populous region in the U.S. and one of the fastest growing. It is also geographically large, encompassing an area larger than the State of Maryland. It is largely politically conservative, and municipalities have a history of competing with each other for growth and economic development opportunities (Grodach, Citation2011). Since 2011, I have researched climate change planning in DFW, taught aspiring planners, and, since 2016, practiced planning in one of DFW’s larger municipalities. This experience demonstrates the range of challenges in planning for climate change in this region, as well as suggesting some opportunities to overcome these challenges in DFW and similar areas.

Interviews with planners and elected officials across DFW show that most cities are making no explicit climate plans and taking no explicit climate actions. Since the rise of the Tea Party in the region in 2010, local Tea Party groups have protested acceptance of federal funds for planning efforts, membership in global climate organizations, and plans addressing environmental topics (Foss, Citation2018a). The term ‘sustainability’ became a particular flash point, with some conservative groups seeing sustainability plans as a conspiracy to limit private property rights and personal freedoms (Whittemore, Citation2013). At the same time, the economic recession put pressure on municipalities in DFW, and spending time or money on environmental pursuits was seen as taking resources away from more important service provision. Some municipalities also avoided being seen as too environmentally friendly, fearing that would scare away economic development opportunities (Foss & Howard, Citation2015). In this context, interviewees report to either not think about climate change at all or actively avoid public discussion of climate change, to limit potential controversy or protest (Foss, Citation2018a).

Even now, when DFW has recovered rapidly from the recession and growth continues at a brisk pace, a shift from the emphasis on economic development to environmental protection does not appear to be occurring. As a practitioner, I see first hand that planners do not mention climate change within my municipality or at regional meetings with the metropolitan planning organization. Unsurprisingly, climate change is either absent or barely mentioned in the plans we write and implement. In the few instances when environmental plans or policies are promoted, planners in DFW tend to use frames such as saving money, improving public health, and enhancing quality of life, which are more palatable to local citizens (Foss, Citation2018b).

In contrast to this avoidance of climate change by local government staff and officials, the general public in DFW appears to support climate change action. We surveyed approximately 400 members of the public at the Texas State Fair, local festivals, and a university campus in the fall of 2015, and we found consistent support for climate change policies at the local, state, and national levels. Respondents also expressed a willingness to conserve water, conserve energy, and make personal behavior changes to address climate change. Consistent with other U.S. surveys, the DFW respondents display common misconceptions about climate science, such as conflating the hole in the ozone layer with climate change, and have an uneven awareness of local extreme weather risks and their correlation to climate change. These findings suggest opportunities for improving climate education and awareness of actions individuals can take to address climate change. With the absence of leadership by municipal staff and elected officials due, in part, to a fear of political backlash, it is also important to identify avenues for the public to promote a bottom-up climate agenda.