ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on understanding the institutional determinants of adaptive capacity to illustrate emerging challenges and opportunities for climate adaptation in the context of urban pluvial flood risk management. The paper explores and compares the formal-legal as well as the perceived roles and responsibilities of key actor groups in the context of adaptation to urban pluvial flooding in the Dutch city Arnhem. The concluding section questions the assumed power of formal-legal rules and institutions in motivating key stakeholders to take action. It poses that, in order to stimulate participation and collaboration in local climate adaptation, more attention should be paid to the informal institutional context, in particular to the perception of responsibilities.

Introduction

In the summer of 2014, as a result of intense rainfall, several cities throughout the Netherlands provided a playground for people paddling through the streets (De Gelderlander, Citation2014). In June 2016 inundation of urban areas throughout the country resulted in traffic disruptions, damage to buildings and businesses and production standstills (Nu.nl, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Although the downpour events of 2014 and 2016 were labelled ‘extraordinary,’ urban pluvial floods (urban floods from hereon) are not rare in Dutch cities, with several cities repeatedly affected in recent years (Nu.nl, Citation2016c; RIONED, Citation2007). In this paper we focus on one of these affected cities, Arnhem, which in 2014 received the title “the wettest place in the Netherlands” from the Dutch meteorological office, with July 28th recording 80–120 mm rainfall in less than 3 hours . The risk of urban flooding in the Netherlands and beyond is expected to further increase due to climate change (KNMI, Citation2014), socio-economic developments as well as institutional challenges connected to spatial planning and governance not being well equipped to deal with uncertainties (Botzen, van den Bergh, & Bouwer, Citation2010; De Vries, Citation2006). Governments as well as researchers have recognized the need to look beyond engineering measures to provide adequate solutions for urban pluvial flood events.

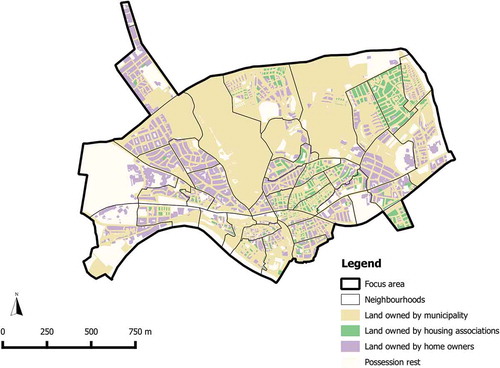

The ‘traditional’ approach to managing urban floods relies on technical measures, usually taken underground, to enhance the discharge capacity of sewage systems. Such interventions require large investments and may be unfit to deal with peak rainfall (Arnhem, Citation2009). Therefore, an increasing emphasis is put on finding above-ground, spatial planning solutions e.g. creating more space for water storage in gardens, parks, streets (Delta Program, Citation2018). Above ground the land is owned and used by a variety of public and private stakeholders with different capacities to engage in adapting to urban flood risk but also with differing interests, perceptions, values and power, that can potentially contribute to or hamper adaptation. To illustrate the fragmentation, depicts the division of land ownership between local municipality, individual home owners, housing associations and other smaller parties in our case study area, Arnhem. Connected to the land ownership, the legal responsibilities for rainwater collection above ground, rainwater discharge and flood protection are divided among different public and private actors. This creates an interdependency between public and private actors in successfully adapting the urban area to growing flood risk – meaning the different land owners need to collaborate and interact in order to achieve efficient ‘on the ground’ solutions for the area. The case of Arnhem thus well illustrates the argument by Campos et al., Citation2016, p. 537) who state that; “[w]ell beyond mere technical solutions, adaptation calls for multidisciplinary approaches and for the active involvement of a diversity of actors in decision-making processes.” The interdependency described above is reinforced by a withdrawing government and economic difficulties, making climate adaptation increasingly dependent on investments and incentives by private actors such as insurance companies (CPC, Citation2014). The research by Kooiman (Citation2003) illustrates that interdependencies can trigger interaction resulting in governance networks. In order to create effective governance arrangements it is therefore essential to uncover the interdependencies between the key actors. For this paper, we define urban flood adaptation governance as the totality of interactions between key state, market and civil society actors on a local level in realizing the collective goal of adapting to urban flood risk (Kooiman, Citation2003; Termeer et al., Citation2011). This paper analyses the capacity of these key actor-groups to work collectively to adapt to climate change in the context of urban pluvial flood risk management.

The fragmentation depicted above adds to the complexity of climate adaptation governance, and points to the necessity of interaction and collaboration between key actor-groups when developing governance strategies to reduce the risk of flooding above ground. The necessity to involve different non-governmental actors in urban flood risk management (FRM) resonates with (claims of) a paradigm shift in water management from policies of “flood defence” to “flood risk management” (Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). This shift entails both

“changes in approaches to FRM such as greater advocacy of soft flood management approaches and redistributions of responsibility including more emphasis on the responsibilities of private citizens” (Butler & Pidgeon, Citation2011, p. 533).

According to different authors, this shifted focus towards “risk” could “significantly change the role of the involved stakeholders” (Bubeck, Botzen, & Aerts, Citation2012, p. 1481; Butler & Pidgeon, Citation2011). In line with this paradigm shift in the Netherlands, many recent national-level policy documents on adaptation refer specifically to individual responsibility as an important strategy to cope with the impacts of climate change (Bergsma, Gupta, & Jong, Citation2012).

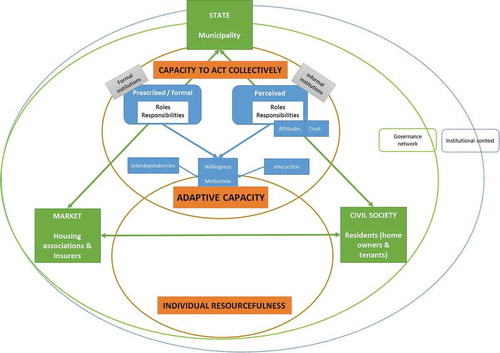

This paper focuses on understanding institutional determinants of adaptive capacity in a local context, specifically the ways formal and informal institutions influence the capacity of key actors to act collectively (Adger, Brooks, Bentham, Agnew, & Eriksen, Citation2004). Although often briefly discussed in social adaptive capacity studies (e.g. Yohe & Tol, Citation2002), adaptive capacity “is not much analyzed directly in relation to institutions” (Bergsma et al., Citation2012, p. 14). This paper aims to address this knowledge gap by zooming into both formal-legal roles and responsibilities and the perception of roles and responsibilities by the key actor groups in the context of urban pluvial flood risk management (see ).

Adapting to Urban Flood Risk: Adaptive Capacity as Capacity to Act Collectively

In the context of climate change adaptation, adaptive capacity determines whether a system is successfully capable of adapting to the adverse effects of climate change (IPCC, Citation2007). In more general terms, it implies possessing the capacities for making adjustments within the system to make it less vulnerable (e.g. Folke, Hahn, Olsson, & Norberg, Citation2005). Termeer et al. (Citation2011) point out that local climate adaptation depends on the involvement of many public and private actors with their own ambitions, interests, beliefs, knowledge and resources. This results in a complex multi-actor setting with mutual and unequal interdependencies between actors (Kooiman, Citation2003), but also potential discrepancies between formal/prescribed roles and responsibilities and the perception of them. In order to analyse such settings, Adger et al. (Citation2004) suggest focusing on two key elements which determine the capability of a system to adapt; the capacity of individuals to adapt (determined by the availability of certain resources) and the capacity to act collectively in the face of a threat. In this paper we focus on the latter indicator of adaptive capacity in connection to prescribed and perceived roles and responsibilities of the key actors.

Adger et al. (Citation2004) argue that societies have inherent capacities to adapt to climate change and that these capacities are dependent on the ability of societies to act collectively. Collective action requires networks and flows of information between parties (Adger, Citation2003). Ward, Pauw, van Buuren and Marfai (Citation2013) state that agreement on the distribution of responsibilities and tasks is a prerequisite for successful collaboration in complex multi-actor settings. Research by Runhaar, Mees, Wardekker, Sluijs, and Driessen (Citation2012, Citation2017) points specifically to the lack of clarity about responsibilities, lack of cooperation between key actors and lack of resources as the key barriers that hamper both problem recognition and the development of climate change adaptation plans. The above makes adaptation a dynamic societal process within which governance networks and relations between interdependent state, market and civil society actors play a key role (Smit & Wandel, Citation2006). Interdependence arises when the actions of one actor lead to consequences for another actor (Bisaro & Hinkel, Citation2016, p. 355). Adaptive capacity is also partly determined by governance structures and their institutional contexts to enable and stimulate adaptation (Root, van der Krabben, & Spit, Citation2015). This refers to both, institutional structures (hierarchical, rigid governmental or more fluid, synergetic governance), as well as leading attitudes (sense of urgency, problem recognition) within these institutions. Understanding and intervening in these institutional contexts and governance structures is an important means for increasing adaptive capacity (Adger, Citation2003). Creating synergies between institutions and individuals can stimulate climate change adaptation (Adger, Citation2003), and, on the flipside, conflicts can raise barriers that hamper adaptation (see Runhaar et al., Citation2012). At the local level, national regulations or economic policies; e.g. budget cuts and the increased decentralization of responsibilities to local governments, can form a barrier reducing the urgency for climate adaptation. Following on from Adger (Citation2003) as well as Runhaar, Wilk, Persson, Uittenbroek, and Wamsler (Citation2017), this paper focuses on exploring the institutional context of climate adaptation in Arnhem in order to understand the emerging challenges and opportunities for climate adaptation in both, planning theory and practice.

The factors that enhance the adaptive capacity, described above, remain quite general for a reason: adaptive capacity is context specific (Adger et al., Citation2004; Smit & Wandel, Citation2006). The capacity to adapt varies amongst countries, municipalities, cities, groups and individuals. Furthermore, it changes over time (Smit & Wandel, Citation2006) and also differs between types of risk. Different types of risks require different types of resources and involve different networks of interdependent actors. It is therefore important to note that in planning practice, an effective capacity building strategy needs to be tailor-made to fit the specific institutional and governance context.

Climate Adaptation, Institutionalism and Responsibility Attribution

Governance processes are embedded in an institutional context which shapes governance interactions (North, Citation1990). Institutions are essential for the evolution and persistence of collective action (Adger, Citation2003). In the growing adaptive capacity literature, Engle (Citation2011, p. 649) argues, there has been an

“affirmation of the integral role that institutions, governance, and management play in determining a system’s ability to adapt to climate change” (cf. Agrawal, Citation2008; Gupta et al., Citation2010; Yohe & Tol, Citation2002).

At the same time Berman, Quinn, and Paavola (Citation2012, p. 95) contend that

“[w]hile a substantial amount of research has examined the capacity of institutions themselves to adapt, there is much less research on how they influence adaptive capacity of individuals or communities”.

While a few recent studies (e.g. Glaas, Jonsson, Hjerpe, & Andersson-Sköld, Citation2010) have started to fill that gap, by focusing on the formal institutional context, not much is known about the role of informal institutions in climate adaptation. This is the knowledge gap this paper aims to address.

Although institutions can be interpreted in a variety of ways (Kim, Citation2011), they can generally be divided into formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include “state institutions (courts, legislatures, bureaucracies), state enforced rules (constitutions, laws, regulations), and official rules that govern organizations” and informal institutions “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels” (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004, p. 727). In contrast to the formal institutions, informal institutions are embedded and tacit, and include intangibles e.g. cultural norms, values, and accepted ways of doing things (Pelling, High, John, & Denis, Citation2008). Informal institutions are reproduced by, but also give shape to, repeated rounds of customary behaviour (Pelling et al., Citation2008). Because institutions provide taken-for-granted models for social interaction, they tend to be enduring and resist change (Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2006). New institutionalism, however, postulates that institutions are “not necessarily predetermined but are socially constructed in daily practice” (Hudalah, Winarso, & Woltjer, Citation2010, p. 2257) implying that institutions can also be reconstructed and changed through social practice (Kim, Citation2011). Compared to formal institutions and their speed of change, informal institutions are much more ambiguous, persistent and dynamic. However, when discussing institutional change, it is important to point out that formal and informal institutions do not exist separately from each other, but are rather intertwined – supporting, complementing or competing with each other (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004). The research by Helmke and Levistky (Citation2004) but also Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009) illustrates that it is particularly relevant for changes to formal institutions to become reflected in informal institutions and enacted in daily practices. According to Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009) embedding the formal rules in actors’ values and norms may be as important for compliance as enforcing them by formal sanctions.

In the context of this research, we follow Mees, Driessen, and Runhaar (Citation2014); to analyse the formal institutions/responsibilities instrumentally, as the tasks of an actor or organization for which it can be held accountable. Informal institutional context is conceptualized along two features: the perception of key actors on the (distribution of) roles and responsibilities in urban flood adaptation and their attitude/willingness towards taking action. Previous research has pointed to the relevance of a clear division of roles and responsibilities and importantly, agreement on this division of roles and responsibilities as a condition that influences climate change adaptation behaviour (Mees, Citation2014; Terpstra & Gutterling, Citation2008; Ward et al., Citation2013). In particular, Bubeck et al. (Citation2012) point out that, while individual’s perception of flood risk is often assumed to provide relevant insights for risk management, it is even more important to understand the perception of responsibilities, as the latter may be more influential for translating the high risk perception into protective behaviour (Bubeck et al., Citation2012).

In the context of the Netherlands – the principle of legal certainty is key to Dutch spatial planning, which hinges strongly on formal institutions (Spit & Zoete, Citation2009). Despite that, climate change adaptation as such is not integrated into Dutch legislation. The formal institutional context contains two ‘motivators’ for urban climate adaptation: the Dutch Water Act 2009 assigns legal responsibility to landowners for processing rainwater and for protecting owned property against urbanflood damage. Water management in the Netherlands has traditionally been centralized with narrow stakeholder participation and a dominance of governmental actors, technical approaches to risk management, expert knowledge, and engineering practices. Bergsma et al. (Citation2012) argue therefore that the recent institutional shift in Dutch water management creates challenges for increasing the adaptive capacity. The authors list the lack of clearly defined responsibilities and accountability procedures, an overlap in municipal and individual responsibility, and the scattered and not easily accessible information to individuals, as the main difficulties for increasing adaptive capacity (Bergsma et al., Citation2012). According to Bergsma et al. (Citation2012, p. 16)

“in an effort to clarify responsibilities in local water management, the Dutch government has initiated several new regulations, a number of which explicitly deal with individual responsibility.“

The above illustrates that changes to responsibility-attribution have taken place through formal, national-level instruments and institutions.

Focusing on informal institutions and changes in practices, Hartmann and Spit (Citation2014) emphasize the relevance of creating a common understanding (of climate problems) for successful climate adaptation, and argue that awareness, recognition and urgency are among its most important components. Research by Terpstra and Gutteling (Citation2008) shows that Dutch individuals have a low sense of urgency for thinking about their own responsibility in FRM (Flood Risk Management). The low sense of urgency is strongly related to the high levels of trust in the governmental actors for “keeping people’s feet dry.” According to Terpstra (Citation2011, p. 1658), a higher level of trust first “reduces citizens’ perceptions of flood likelihood, which in turn hampers their flood preparedness intentions” and second “trust also lessens the amount of dread evoked by flood risk, which in turn impedes flood preparedness intentions.” Wachinger et al. (Citation2013) explain that in a context where responsibility is attributed to another, highly trusted, party – individuals may understand the risk but do not realize any agency for their own actions; the responsibility for action is transferred to someone else. Trust and the related realization of responsibilities and willingness to act are, by extension, a great influence on the capacity to act collectively (Adger, Citation2003; Pelling & High, Citation2005).

The above literature review highlights, on the one hand, the relevance of understanding the institutional context in which climate adaptation takes place in order to create effective climate adaptation strategies, and, on the other hand, points out that knowledge of the way (particularly the informal) institutions influence adaptive capacity remains understudied. By comparing and contrasting the prescribed and perceived responsibilities of key actors in the context of local urban climate adaptation, this paper aims to contribute to filling this knowledge gap.

Operationalizing Adaptive Capacity for Urban Flood Risk Management

visualizes the conceptual framework of this research and summarizes the theoretical discussion above. For analysing adaptive capacities at the local level, four key actor-groups (municipalities, housing associations, insurers and residents) were identified and selected for empirical research. Municipalities, housing associations and residents are considered the key actors based on their ownership and occupancy of land and dwellings. Insurers are considered a key stakeholder since they bear a big financial share of an increasing total of weather-related damage (Mills, Citation2007a; Munich Re, Citation2006). Research by Mills (Citation2007a) shows that industry analysts, representatives and boards of insurance companies throughout the world rank climate change as a leading risk for the insurance sector. In addition, due to their financial capacity (Mills, Citation2007b) and ability to encourage risk-reducing behaviour amongst policy holders, insurers can play a relevant role in climate adaptation. In the empirical sections below, the paper focuses on exploring the way the perceived and prescribed roles and responsibilities of the four key actor-groups influence their capacity to act collectively in local climate adaptation.

Research Approach and Methods

To study the complex context in which climate change adaptation takes place in detail, this research employs a case study approach (Yin, Citation2003) using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods. Four embedded units of analysis within the city of Arnhem were identified: the municipality, housing associations, insurance companies and the residents. The data collection was conducted between 2014–2015. The results are based on the perceptions of the respondents during that period.

Semi-structured interviews and a survey were used to collect empirical data. Additionally, ESRI ArcGis and Q-GIS were used for analysing the landownership in Arnhem amongst key urban flood risk governance actors. The researchers made use of the municipal GIS-database to obtain the required spatial data.

As illustrates, eight key-actor interviews were conducted. The data obtained from the interviews were transcribed and coded using NVIVO software following the conceptual model ().

Table 1. List of interviewees.

A survey was used to gather data about the residents. Tenants and homeowners received slightly different questionnaires. The survey consisted mainly of fixed-response questions and was conducted online via Google Forms. To distribute the survey amongst the target population, the researchers spread 1000 letters randomly throughout the neighbourhoods in the focus area as well as sharing the link to the survey through social media. In addition, the municipality of Arnhem posted the link on their Facebook page and Twitter account. Furthermore, the regional newspaper De Gelderlander published an article about the questionnaire including the link. The target population of the survey were all 56 749 residents living in the focus area. In total 141 people filled in the questionnaire. 21% of the respondents were tenants and 79% home owners; the target population was 54% tenants, 43% home owners, 3% other/unknown. 42% were female and 58% male; the target population was 49.9% male, 50.1% female. 16% of our respondents were below the age of 30, 36% between 30–50 years old and 48% were older than 50; the target population was 0–25, 29%; 25–45, 29%; 45+, 41%. Extracting the responses from outside the focus area left a utilizable sample size of 125 respondents which corresponds to a confidence level of 91% (Yamane, Citation1967). This confidence level is not enough to make statistical generalizations (Smithson, Citation2003). Therefore the authors wish to emphasize that sounding a note of caution is in order when aiming to make general statements about the survey results below. However, since the survey outcomes were triangulated with data acquired by other methods, with the aim to make analytical generalizations, a confidence level of 91% was considered appropriate. To determine the significance and association between different variables and test the hypotheses, cross tabulation analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS software. The Chi-square test was used to determine the significance of the relationship between variables. Answers to the open questions were coded and analysed with qualitative data analysis software NVIVO.

Climate Adaptation and Governance of Urban Flooding in Arnhem

The municipality of Arnhem with a population of 152 288 is located in the East of the Netherlands (Gemeente Arnhem, Citation2015). Arnhem is the capital of the province of Gelderland situated along the river Nederrijn. Due to its key position in rail, water and road infrastructure network, Arnhem is of great economic value for the region. The gradient of the Veluwe lateral moraines, the river zone and polder areas on which the 101.54 km2 of the municipality of Arnhem is located give the city a very diversified appearance (Gemeente Arnhem, Citation2015) but also add to the risk of flooding and the unequal distribution of that risk in different neighbourhoods.

Four actors were identified as key in the local urban flood governance network in Arnhem: the municipality, housing associations, residents and insurance companies. The first three actors were selected based on land ownership. Although insurance companies in general do not possess land, they can have a strong influence on how the possessions on that land are managed and protected from hazards. In a similar vein, although tenants do not own dwellings, they can have an important indirect impact on climate change adaptation by influencing housing associations, and are therefore also included in our analysis.

The analysis in the sections below centres upon these four actors comparing and contrasting: a) the prescribed/formal roles and responsibilities (formal institutional context) and b) the perceived roles and (the division of) responsibilities and the attitude towards taking action (informal institutional context). Finally, the interdependencies between key actors and potential triggers for interaction are discussed.

Results and Discussion: Institutions, Interdependencies and Adaptive Capacity in Arnhem

Formal Institutional Context: Prescribed Roles and Responsibilities

Municipality

In the Netherlands, municipalities play a key role in climate change adaptation on the local level as they exercise a key influence on local spatial planning (Termeer et al., Citation2011). The Water Act (Waterwet) ascribes to municipalities the responsibility for collecting and processing rainwater (Article 3.5) and preventing structural groundwater flooding (Article 3.6). In addition the Environmental Management Act (Wet milieubeheer) assigns to municipalities the responsibility for the collection and discharge of sewage water. Runhaar et al. (Citation2012) state that this legal responsibility is a key motivation for municipalities to seek new ways to adapt to growing urban flood risk. The municipal responsibilities are labelled as a “duty of care” (zorgplicht). This municipal duty of care implies an obligation for the municipality to make an effort (inspanningsverplichting) rather than to achieve a certain result (resultaatverlpichting) in relation to urban flood risk management (Mols & Schut, Citation2012). The municipal duty of care is limited to the public domain. How a municipality fulfils its duty of care is determined in the Municipal Sewage Plan (Gemeentelijk Rioleringsplan). Previous research examining all Dutch municipalities showed that 60% anticipate increasing urban flood risk due to climate change in their sewage plans (RIONED, Citation2007). The expenses that municipalities incur for performing their duty of care are reflected in property owners’ sewage taxes (rioolheffing). Legislation allows for the sewage tax to be combined or spilt up in sewage water tax and a rain and surface water tax (VNG, Citation2007). Article 10.32a in the Environmental Management Act gives municipalities the power to define rules considering the discharge of rainwater. Ideally the processing of rainwater would occur locally by infiltration or discharge in open water.Footnote1 Establishing additional discharge rules should occur in integral deliberation with the province, regional water authorities and other concerned actors.Footnote2

Housing Associations

Housing associations are semi-private organizations that own ~ 30% of the total Dutch housing stock (CBS, Citation2014). In general, a single association possesses a large number of dwellings (CFV, Citation2012). Considering the amount of properties owned, it is not surprising that Roders, Straub and Visscher (Citation2013, p. 279) describe housing associations as an “important starting point in the implementation of climate change adaptation measures.”

Housing associations have two legal responsibilities relevant for implementing urban flood adaptation measures. The first is defined by the Water Act (article 3.5), stating that landowners are primarily responsible for processing rainwater on their land through either infiltration into the ground or discharge into open water. Only when it is not reasonable to expect property owners to process the water themselves does the collection and discharge of surface runoff become a municipal task (Mols & Schut, Citation2012). Measures that landowners can reasonably be expected to take are defined in the Municipal Sewage Plan.Footnote3 It is important to note that this plan, enforced from 2008, is not valid in retrospect and therefore only applies for dwellings built from 2008 onward (VNG, Citation2007). The rules which housing associations have to follow concerning processing and discharging rainwater thus depend upon the location and date on which the owned dwellings were constructed (Gemeente Arnhem, Citation2009).

The second relevant responsibility of housing associations is defined in the ‘Social Rent Sector Management Order’ (Besluit beheer sociale-huursector) which requires housing associations to provide their tenants with a good quality of life and housing, now and in the future (Roders et al., Citation2013).

The above regulations do not oblige housing associations to take additional urban flood adaptation measures when the risk increases, although they are accountable for flood damage to their dwellings.

Residents

For homeowners, the legal responsibilities for processing surface water runoff are the same as for housing associations, based on the Water Act (see above). In addition, article 5:38 of the Civil Code of the Netherlands (Burgerlijk Wetboek) states that lower-lying parcels are obliged to receive natural runoff from higher lying areas. This implies that property owners from properties located on higher ground cannot be held responsible for water damage that occurs lower due to natural runoff from their property, potentially creating an unequal distribution of risk. In addition, building regulations explicitly state that landowners are responsible for making sure their building and parcel meet their own wishes; this includes making a dwelling rainproof if that is desired (VNG, Citation2007). Tenants can exercise influence on the property owners to take adaptation measures, however they are not legally obliged to do so. They are, however, responsible for damage to their own belongings in the property.

Insurance Companies

Considering their private nature, the role of insurance companies cannot be discussed in terms of legal responsibilities, but rather legal and formal arrangements available and their potential as well as attitude towards making a contribution to climate change adaptation. According to Interviewees A & G, insurers in the Netherlands are at present not obliged to insure for urban flood damage.

Despite the lack of legal requirements, insurance companies do play a role in climate change adaptation by providing households with options to insure themselves for damage caused by urban flooding. In the Netherlands, damage by rainwater is usually covered by standard (home) building insurance (opstalverzekering) and household insurance (inboedelverzekering). The “precipitation clause” (neerslagclausule) determines that damage as a result of downpours more intense than 40 millimetres in 24 hours, 53 millimetres in 48 hours or 67 millimetres in 72 hours, on and/or nearby the location where the damage occurs, will be covered (Dooper, Lammers, & Kok, Citation2000).

Informal Institutional Context: Attitudes and the Perception of Roles and Responsibilities

“It [‘rainproofing’ a city] is like playing chess on multiple boards. You cannot be dependent on a single actor if you really want to be adaptive … I think if you do not focus on a wide diversity of actors you will miss relevant opportunities in making a city rainproof” (Interviewee D, Amsterdam Rainproof).

The interviewees from the municipality as well as its key documents are unambiguous about urban flood adaptation being a shared responsibility. The municipality considers individual land-owners key actors for taking measures to rainproof the city and emphasize the influence of residents on neighbourhood planning and their ability to ‘push’ the municipality and housing associations to take action.

“Climate adaptation demands a good spatial planning and design of public and private space and good urban development. […] Here lays an important role for residents. Residents determine what happens in a neighbourhood. […]With a shift in power from the office to the neighbourhoods, I think … neighbourhoods will more often choose for spatial quality, something I have missed in the past ten years” (Interviewee B, Municipality).

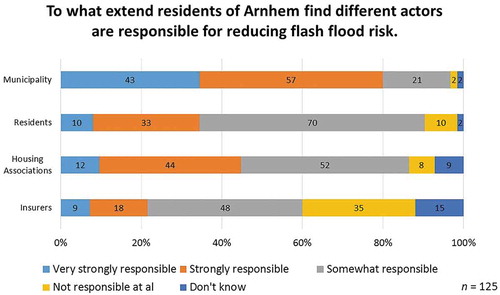

However, as illustrates, the residents of Arnhem consider the municipality as the actor bearing the greatest responsibility for reducing urban flood risk. Housing associations, insurers and residents are all considered relatively equally and relatively marginally responsible (between 9–12%). Similar research conducted by Watermonitor (Citation2009) (1227 respondents) shows that citizens consider urban flood risk management the responsibility of the government (90%), and see themselves as the least responsible actor (28%). Furthermore, only a small percentage considers climate change adaptation an urgent matter (8%) (Watermonitor, Citation2009).

The survey results also illustrate that the residents are not well aware of their legal responsibilities for processing rainwater on their own parcel(s), with 19% of respondents being aware of such responsibilities. The respondents were somewhat more aware (21%) of their legal responsibility to protect owned property against urban flood damage. This is in line with the findings of Terpstra and Gutteling (Citation2008) and Watermonitor (Citation2009). A strong significant association was found between awareness of legal responsibilities to protect owned property against urban flood damage and taking measures to protect owned property against urban flood damage (P = 0,001, Phi = 0.364). Attributing responsibilities to another party and the strong trust in that other party (the municipality) for FRM could be possible explanations for the low awareness and preparedness of citizens.

The lack of taking preparedness measures is often associated with low awareness about alternative measures. However, the answers to the open question posed in this research show residents to be well aware of alternative measures to reduce urban flood risk – measures, which they could also take on their own privately owned land. The open question “How can the municipality improve its approach to urban flooding?” yielded a variety of ideas from the residents. While the majority of respondents mentioned increasing sewage capacity as a relevant improvement, alongside they also proposed spatial planning solutions. “More plants, less concrete” and “ponds, parks and green roofs” were the most frequently mentioned improvements. In addition, although often implicitly, the role of individuals was acknowledged. “Stimulate citizens and companies to design their land in a way that water can infiltrate into the ground”, “provide subsidies for green roofs” and “make it compulsory for higher parcels to remove tiles and concrete from their gardens” were among the suggestions made. In addition, raising awareness of citizens of what measures they could take and importantly, involving them in planning their neighbourhood were discussed by a number of respondents: “Do more than just distributing an information folder. Ask citizens per neighbourhood/street to make plans together and support implementation” and “Give citizens a chance to also react to the changes planned for the neighbourhood” were among the answers given. The responses to the open question indicate that residents are aware of the relevant role they (in particular the land-owners) can play in reducing urban flooding. However, the responsibility is attributed predominantly to the municipality who is expected to take initiative in stimulating citizens to play a role and take associated responsibilities.

The perception and attitude of the housing associations is summarized in the quote below where the Interviewee housing association C states that:

“Climate adaptation is not something we take a leading role in […]. When an extreme downpour happens we know where the problems will occur. Then we know we have to assign extra workers […] But at the moment we only react when something happens.”

According to the Interviewees (C and I) climate change adaptation is not something housing associations in Arnhem are concerned with. Therefore, it is not a part of their policy. This is in line with what Climate Proof Cities (Citation2014) states on the attitude of Dutch housing associations towards climate change adaptation. Although the downpour event of 2014 had an impact on the housing associations’ assets, it was no reason to change their policy or take a more proactive role. Whenever housing associations engage in urban flood risk management it is demanded or initiated by the municipality (Interviewees housing association C and I). The municipality is considered as playing a leading role in urban flood adaptation and being the main responsible actor:

“[t]he discharge capacity of the municipal sewer system is too low, this will result in problems. Therefore we lay the responsibility with the municipality and not with us” (Interviewee housing association C).

The international insurance sector increasingly perceives itself as a key actor in climate change adaptation: “Insurers are, by definition, interested in preventing losses rather than paying to repair post event damages” (Mills, Citation2007b, p. 829). Mills (Citation2007a) shows how this interest motivates the insurance sector to get involved in diverse public-private partnerships. In the context of local climate adaptation, it should noted, however, that the spatial organisation and priorities of many insurers may make it hard for them to achieve territorially-focused action. Contrary to the examples by Mills (Citation2007a), our research indicates the rather passive attitude of the Dutch insurance sector and a lack of perceived interdependencies. Results from different interviews illustrate that the sense of interdependency is connected to the perception and attitudes of insurance companies. Interviewee insurance A does not see climate change adaptation as an urgent issue but acknowledges that insurers have a social responsibility in providing their customers with knowledge and information on threats of climate change and possibilities to reduce urban flood risk. The respondents stated that at present, insurers are not getting involved in urban flood adaptation. They are likely to respond to growing risks by changing policy conditions, raising premiums or raising deductibles (Interviewee insurance A). Interviewee insurance F considers the growing urban flood risk as an urgent matter and is actively building a network with multiple municipalities aiming to reduce damage of extreme downpours:

“I see it as our job to work together with the stakeholders. And use our knowledge. Because we know what the economic damage of an extreme downpour is … We could consider what is heading towards us as a threat but also as an opportunity. Threat in the sense that it will result in a higher burden of claims and that we have to give customers different policy conditions. But you could also grasp it as an opportunity by working together […] I will never be able to prevent rising burden of claims. I will only be able to dampen the blow with collaborating on innovative prevention.”

The residents in our survey reported being insured by 22 different insurers. Since, as our results indicate, different insurers can be expected to take a different approach to dealing with climate change adaptation, this fragmentation illustrates an incoherence of approaches that can be expected to be found within a single neighbourhood. Despite the fragmentation, similarly to the municipality, Interviewee insurance F emphasizes the central role of the residents in influencing decision-makers and (other) property owners to take climate change adaptation measures.

Interdependencies, Sense of Urgency and (Finding) Triggers for Interaction

Our findings align with the argument by Kooiman (Citation2003) about interdependencies triggering interaction. The strong sense on interdependency from the municipality towards the housing associations was a trigger to start discussions about urban flood management. The extreme downpour in 2014 was another trigger for interaction. Following the event, the housing associations joined the neighbourhood visits of the municipality (Interviewee municipality J) and offered some households the possibility of getting a removable barrier installed (Interviewee housing association C). Interviewee housing association I pointed out that, in collaboration with the municipality, they will start providing their tenants with information on urban flood adaptation.

After the flood of July 2014 the municipality started compiling the “Municipal Action Plan Urban Floods” (Actieplan Wateroverlast) (MAP from hereon), which aims to assess what measures can be taken to reduce the impact of heavy downpours and to create a platform for interaction (Gemeente Arnhem, Citation2014). In addition, the Municipal Strategic Note (Perspectiefnota 2016–2019) formulated renewed principles of collaboration between the municipality and the society. Among other principles, the necessity to optimise the expertise and creativity of residents is emphasized as well as the need for a more structural interaction between residents, the municipality and other institutions (Gemeente Arnhem, Citation2015). The MAP is therefore created in close collaboration with the residents (Interviewee municipality B). However, the results from our questionnaire show that only 22% of the respondents were aware of the MAP although the residents surveyed were residing in the neighbourhood most severely affected by the 2014 flooding. This indicates the interaction may not have involved a broad audience. The results also show that 96% of the respondents are willing to play an active role in preventing flooding. There is thus much underutilized potential for collaboration on the issue.

The interactions between the municipality and the residents are predominantly based on the exchange of informational resources and knowledge. In the past the municipality has stimulated residents to implement urban flood adaptation measures by offering a subsidy. However, Interviewee municipality E doubts its usefulness and prefers to focus more on awareness-raising and communication. Indeed, throughout the interviews the relevance of communication and the municipality explaining responsibilities to other actors was brought up, in particular in relation to the MAP. Interviewees municipality B and E emphasize the importance of the municipality playing a facilitating role. Interviewee municipality B sees this facilitating role as setting the right example when designing public spaces, and giving private actors more opportunities to introduce their ideas in the design process. Interviewee municipality E sees the facilitating role as providing information and formulating clear policy frameworks within which residents have the freedom to take their own initiatives. In addition, the role of housing associations in providing the tenants with information and communicating about the relevance of climate change adaptation was emphasized.

As a result of the 2014 downpour, the housing associations received around 1200 complaints from the tenants (Interviewee municipality B). When repairing the damage fell under the responsibility of the housing association their maintenance team took action. Although the interaction between the tenants and the housing association increased, the financial damage was not mentioned by the housing associations’ representatives as a motivation to take further adaptive measures.

The interdependencies between residents and other actors differ slightly between tenants and homeowners. For instance, tenants, unlike homeowners, need the approval of their landlord to take certain adaptation measures. Results from the survey show that residents feel a strong dependency on the municipality for reducing urban flood risk with more than 70% of respondents stating feeling “strongly or very strongly dependent.” Statistical analysis shows that the sense of interdependency is strongly associated with the perception of the distribution of responsibilities. Residents feel interdependency towards the actors they consider responsible for urban flood adaptation.

Results from the survey show that only 5% of the residents feel strongly dependent on insurers for urban flood adaptation. Statistical analyses show that the feeling of interdependence has a strong association with residents’ perceptions of to what extent insurers are responsible for reducing urban flood risk (strength of association 0.818). The residents’ low perception of the urgency of urban flooding is perhaps best illustrated by the finding that 42% of the respondents did not know whether they were insured for urban flood damage.

Interviews show a weak sense of interdependency and very limited interactions between the insurance sector and both the housing associations and the municipality (Interviewees J, C, I). For housing associations – both Interviewees C and I state that as far as they know, the downpour of July 2014 did not result in significant damage to their housing stock and no insurance claims were filed. Although no strong sense of interdependency is reported, both Interviewees municipality B and J state it will be valuable to know the exact financial damage of the downpour of July 2014 to also evaluate the economic benefits of taking urban flood adaptation measures:

“Is it [urban flood adaptation] something we should invest in? It is such an extreme exception […] What does something like that cost? There is no idea about that” (Interviewee municipality B).

This lack of information could hamper the municipality’s understanding of urban flood vulnerability and damage but also implies a lack of willingness to prioritize the pluvial-flood related issues and to make financial resources available. The above example illustrates the interdependency and potential benefits of interacting with the insurance companies who state that they do possess relevant information on the financial consequences of urban flooding (Interviewee insurance F).

The results of the interviews with representatives of the insurance sector show that the sense of interdependency on residents in urban flood adaptation differs per insurer and is connected to the perception of their own role. Interviewee insurance A sees insurers more as a service provider, and does not see growing urban flood risk as a danger for the sector. From that perspective insurers are not dependent on residents for urban flood adaptation. Interviewee insurance F however considers residents to be the key actors in urban flood adaptation, able to halt the expected rise of the burden of claims. Therefore, Interviewee insurer F hopes to enhance the interaction between the insurers and the residents:

“We have a trajectory promoting awareness of residents though diverse channels […] We want to create a game for residents where they can motivate each other. They can show, here we experience problems after extreme downpours in the public domain or in our home or garden, tag the location on the map, make a picture. By doing that they become ‘sensors’ for the city and they also receive green coins. […] With the coins they receive they get a discount on the measures that can be found in our online prevention store. That is how we want to stimulate social engagement, awareness and prevention.”

Our findings indicate that, while residents generally do not see the changing precipitation patterns as a threat for their personal situation, they do consider them as a threat for Arnhem in general. Perhaps surprisingly, the residents seem to be generally interested in urban flood management as a topic. The home owners in particular are feeling either strongly or very strongly responsible (77%) for protecting their home against damage and somewhat less responsible (44%) for reducing runoff from their property.

Conclusions

This paper focused on exploring the institutional determinants of adaptive capacity in a local context, specifically the ways formal and informal institutions influence the capacity of key actors to act collectively in managing the risk of urban flooding. Using the city of Arnhem as an example, the paper explored the prescribed and perceived roles and responsibilities of the key local actors (municipality, housing associations, residents, insurance companies) in adapting to the growing pluvial flood risk.

Our findings highlight a gap between the prescribed and perceived responsibilities of the key actors and a lack of agreement on the distribution of responsibilities in urban flood risk management. Ward et al. (Citation2013) state that agreement on the distribution of responsibilities and tasks is a prerequisite for successful collaboration in complex multi-actor settings. The findings of this research illustrate that when the responsibility for urban flood risk management is attributed to another, trusted, party – the key actors relevant for local climate adaptation may understand the risk but will not proactively take protective measures against it and will not look for ways to collaborate. For effective local climate adaptation, this paper thus argues, it is necessary to pay more attention to achieving an agreement on the distribution of roles and responsibilities at the local level, in parallel to the changes taking place in the formal-legal distribution of responsibilities at the national level.

Previous research illustrates that a change to informal institutions and ‘the ways things are done’ may take a long time and, rather than being negotiated, needs to be enacted in shared practices (Pahl-Wostl, Citation2009). According to Pahl-Wostl (Citation2009), involving actors in the design of formal institutions can increase their compliance and effectiveness. Cases such as the HafenCity in Hamburg could serve as examples of public authorities investing in continuous collaboration with the local residents (Mees et al., Citation2014). Another recommendation for planning practice, based on the findings from this research, is for the authorities to invest in local level collaboration and interaction, aiming to create a common understanding of the problem as well as the necessary actions and contributions by different parties, and only later formalizing the responsibilities through, for example, a special local law. Such experiences of trust-forming relationships have been found to increase the willingness to act (Wachinger et al., 2013) and can result in a shift towards realizing personal agency to protect oneself. The findings of this research show that trust, and the related realization of responsibilities and willingness to act, are, by extension, of great influence on the capacity to act collectively (Pelling & High, Citation2005).

The research reported in this paper underlines that a sense of urgency and problem recognition are the key drivers for interaction in a governance network. This point is particularly critical in the context of the Netherlands where private responsibility by individual citizens in FRM has not existed and flood risk has never been a subject of public debate (Terpstra & Gutteling, Citation2008). Finding opportunities for creating a common understanding of the problem amongst different actors could therefore go a long way in improving their willingness to take a more active role in climate adaptation. However, when focusing on the distribution of resources and impacts of climate adaptation measures, it should be acknowledged that neither is distributed equally among the actors. The interests and ‘stakes’ of the key actors as well as their ability to be involved in climate adaptation can radically differ. In order to do justice to the different and unbalanced interests, and recognize the place-based vulnerabilities, Paavola and Adger (Citation2006, p. 595) call for a fair process which recognizes and enables “the participation of affected communities in planning and decisions regarding collective adaptation measures.” This was also echoed by our survey respondents. The results of this research thus highlight the value of creating a more permanent platform on which climate adaptation related interactions could occur, where affected parties could voice their concerns, and which would coordinate adaptation efforts. The literature furthermore suggests that interaction is important for relocating resources and for enhancing the capacity to act collectively (Termeer et al., Citation2011). Stimulating interaction in such a broad urban flood adaptation network/platform enhances the potential exchange of resources, the potential for innovative collaborations and coalitions as well as the potential for balancing the different interests and vulnerabilities and, by extension, contributes to an increase in adaptive capacity. Our findings show that due to their access to data and connection with policyholders it could be particularly valuable to also involve the insurance sector on such a platform.

Above all, the findings of this research reveal that the formal institutional context – the formal-legal rules and regulations – is in itself not enough to stimulate key actors to take action for climate adaptation. Our findings call for more emphasis to be put on (understanding) the informal institutional context in order to motivate the key actors, to involve them in adaptation plans and to ultimately create effective governance arrangements for climate adaptation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers as well as the editors of Planning Theory and Practice for their valuable feedback on the earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

E-M. Trell

E-M. Trell is assistant professor at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment at the University of Groningen. Her research focuses on the role of collective action (citizen initiatives, participatory governance but also protest movements/dissent) in creating more resilient, sustainable and inclusive places. The themes she explores within this context include: agro-food movements and food sovereignty/democracy; community resilience in declining (rural) areas; climate change adaptation and community resilience to flooding.

M.T. van Geet

M. T. van Geet is a PhD-researcher at the Department of Spatial Planning and Environment at the University of Groningen. His research focuses mainly on the interrelation between transport infrastructure and land use planning. More specifically, his research focusses on aligning policy goals and instruments to encourage the successful development and implementation of integrated land use and transport policies.

Notes

1. Parliamentary Papers II 2005–06, 30 578, nr. 3, p.30.

2. Parliamentary Papers II 2005–06, 30 578, nr. 3, p.31.

3. Parliamentary Papers II 2005–06, 30 578, nr. 3, p.12.

References

- Adger, W. N. (2003). Social aspects of adaptive capacity. In J. B. Smith, R. J. T. Klein, & S. Huq (Eds.), Climate change, adaptive capacity and development, pp. 29–49. London: Imperial College Press.

- Adger, W. N., Brooks, N., Bentham, G., Agnew, M., & Eriksen, S. (2004). New indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity ( Technical Report 7). Norwich: Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research.

- Agrawal, A. (2008). The role of local institutions in adaptation to climate change. International Forestry Resources and Institutions Program, Working Paper, # W081-3. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

- Arnhem, (2009). Gemeentelijk rioleringsplan 4. Arnhem: Gemeente Arnhem.

- Bergsma, E., Gupta, J., & Jong, P. (2012). Does individual responsibility increase the adaptive capacity of society? The case of local water management in the Netherlands. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 64, 13–22.

- Berman, R., Quinn, C., & Paavola, J. (2012). The role of institutions in the transformation of coping capacity to sustainable adaptive capacity. Environmental Development, 2, 86–100.

- Bisaro, A., & Hinkel, J. (2016). Governance of social dilemmas in climate change adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 6, 354–359.

- Botzen, W. J. W., van den Bergh, J. C. J. M., & Bouwer, L. M. (2010). Climate change and increased risk for the insurance sector: A global perspective and an assessment for the Netherlands. Natural Hazards, 52, 577–598.

- Bubeck, P., Botzen, W. J. W., & Aerts, J. C. J. H. (2012). A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior. Risk analysis, 32, 9.

- Butler, C., & Pidgeon, N. (2011). From `flood defence’ to `flood risk management’: Exploring governance, responsibility, and blame. Environment and Planning C, 29, 533–547.

- Campos, I., Vizinho, A., Coelho, C., Alves, F., Truninger, M., Pereira, C., … Penha Lopes, G. (2016). Participation, scenarios and pathways in long-term planning for climate change adaptation. Planning Theory and Practice, 17(4), 537–556.

- CBS. (2014). Woningvoorraad naar eigendom; regio, 2006–2012. Retrieved from http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?VW=T&DM=SLNL&PA=71446ned

- CFV. (2012). Sectorbeeld realisaties woningcorporaties, verslagjaar 2011. Baarn: Centraal Fonds. Volkshuisvesting.

- CPC. (2014). Climate proof cities –Final report. Climate Proof Cities, component National Research programme “Kennis voor Klimaat”, co-financed by Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment. Wageningen: Knowledge for Climate.

- De Gelderlander. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.gelderlander.nl/regio/arnhem-e-o/hevige-wateroverlast-in-regio-arnhem-1.4467167

- De Vries, J. (2006). Climate change and spatial planning below sea-level: Water, water and more water. Planning Theory and Practice, 7(2), 223–227.

- Delta Program. (2018). Delta Plan on Spatial Adaptation 2018. Retrieved from https://ruimtelijkeadaptatie.nl/english/delta-plan/

- Dooper, H. F., Lammers, I. B. M., & Kok, M. (2000). Verzekeren van regenschade. Waterschap, (2000(17), 802–807.

- Engle, N.L. (2011). Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 647-656.

- Folke, C., Hahn, T., Olsson, P., & Norberg, J. (2005). Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 30, 441–473.

- Gemeente Arnhem. (2009). Gemeentelijk Rioleringsplan 4 2009–2013 [Municipal seweage plan]. Retrieved from http://www.arnhem.nl/Wonen_en_leven/Milieu/Water_en_riolering/Gemeentelijk_Rioleringsplan

- Gemeente Arnhem. (2014). Actieplan Wateroverlast stap 1 [Action plan pluvial flooding]. Retrieved from http://arnhem.notudocnl/cgi-bin/collegebericht.cgi/action=view/id=66748

- Gemeente Arnhem. (2015). Perspectiefnota 2016–2019 [Municipal strategic note]. Retrieved from http://www.arnhem.nl/Politiek_en_organisatie/Gemeente/Jaarverslag_en_begroting/Perspectiefnota_s/Perspectiefnota_2016_2019.pdf

- Glaas, E., Jonsson, A., Hjerpe, M., & Andersson-Sköld, Y. (2010). Managing climate change vulnerabilities: Formal institutions and knowledge use as determinants of adaptive capacity at the local level in Sweden. Local Environment, 15(6), 525–539.

- Gupta, J., Termeer, C., Klostermann, J., Meijerink, S., van den Brink, M., Jong, P., … Bergsma, E. (2010). The adaptive capacity wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environmental Science and Policy, 13(6), 459–471.

- Hartmann, T, & Spit, T.J.M. (2014). Capacity building for the integration of climate adaptation into urban planning processes: the dutch experience. American Journal Of Climate Change, 3(3), 245–252.

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2004). Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics, 3(4), 725–740.

- Hudalah, D., Winarso, H., & Woltjer, J. (2010). Planning by opportunity: An analysis of periurban environmental conflicts in Indonesia. Environment and Planning A, 42(9), 2254–2269.

- IPCC. (2007). Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, & C. E. Hanson (Eds.), Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, pp.976. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kim, A. M. (2011). Unimaginable change: Future directions in planning practice and research about institutional reform. Journal of the American Planning Association, 77(4), 328–337.

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2006). Institutional design: Changing features of networks. Public Management Review, 8(1), 141–161.

- KNMI. (2014). KNMI’14: Climate change scenarios for the 21st Century – A Netherlands perspective. De Bilt: Author.

- Kooiman, J. (2003). Governing as governance. London: Sage.

- Mees, H. (2014). Responsible Climate Change Adaptation: Exploring, analysing and evaluating public and private responsibilities for urban adaptation to climate change ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

- Mees, H. L. P., Driessen, P. P. J., & Runhaar, H. A. C. (2014). Legitimate adaptive flood risk governance beyond the dikes: The cases of Hamburg, Helsinki and Rotterdam. Regional Environmental Change, 14(2), 671–682.

- Mills, E. (2007a). From risk to opportunity: Insurers responses to climate change (Ceres Report). Boston: Ceres.

- Mills, E. (2007b). Synergies between climate change mitigation and adaptation: An insurance perspective. Mitigation Adaptation Strategies Global Change, 12, 809–842.

- Mols, J., & Schut, M. (2012). Gemeentelijke aansprakelijkheid bij wateroverlast; wetgeving, rechtspraak en praktijkvoorbeelde. Bennekom: Drukkerij Modern.

- Munich Re. (2006). Topics geo—Annual review natural catastrophes 2005. Munich: Author.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nu.nl. (2016a). Schade door noodweer Randstad geschat op 20 miljoen euro. Retrieved from http://www.nu.nl/binnenland/4282024/schade-noodweer-randstad-geschat-20-miljoen-euro.html

- Nu.nl. (2016b). Onweer en hagel veroorzaken overlast in Noord-Brabant. Retrieved from http://www.nu.nl/wateroverlast/4282520/onweer-en-hagel-veroorzaken-overlast-in-noord-brabant.html

- Nu.nl. (2016c). Kan Nederland zich wapenen tegen het extreme weer? Retrieved from http://www.nu.nl/weekend/4282921/kan-nederland-zich-wapenen-extreme-weer.html

- Paavola, J., & Adger, N. W. (2006). Fair adaptation to climate change. Ecological Economics, 56, 594–609.

- Pahl-Wostl, C. (2009). A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Global Environmental Change, 19, 354–365.

- Pelling, M., & High, C. (2005). Understanding adaptation: What can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Global Environmental Change, 15, 308–319.

- Pelling, M., High, C., John, D., & Denis, S. (2008). Shadow spaces for social learning: A relational understanding of adaptive capacity to climate change within organisations. Environment and Planning A, 40(4), 867–884.

- RIONED. (2007). Onderzoek regenwateroverlast in de bebouwde omgeving. Retrieved from http://www.riool.net/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=2fc9a665-cc84-422e-b848-789f52e71b7f&groupId=10180&targetExtension=pdf

- Roders, M., Straub, A., & Visscher, H. (2013). Evaluation of climate change adaptation measures by Dutch housing associations. Structural Survey, 31(4), 267–282.

- Root, L., van der Krabben, E., & Spit, T. (2015). Bridging the financial gap in climate adaptation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58(4), 701–718.

- Runhaar, H., Mees, H., Wardekker, A., Sluijs, V. D. J., & Driessen, P. P. J. (2012). Adaptation to climate change-related risks in Dutch urban areas: Stimuli and barriers. Regional Environmental Change, 12, 777–790.

- Runhaar, H., Wilk, B., Persson, Å., Uittenbroek, C., & Wamsler, C. (2017). Mainstreaming climate adaptation: Taking stock about ‘what works’ from empirical research worldwide. Regional Environmental Change, 18(4), 1201–1210.

- Smit, B., & Wandel, J. (2006). Adaptation, adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16, 282–292.

- Smithson, M. (2003). Confidence intervals: Quantitative application in social sciences. New Delhi: Sage.

- Spit, T., & Zoete, P. (2009). Ruimtelijke ordening in Nederland. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

- Termeer, C., Dewulf, A., van Rijswick, H., van Buuren, A., Huitema, D., Meijerink, S., … Wiering, M. (2011). The regional governance of climate adaptation: A framework for developing legitimate, effective, and resilient governance arrangements. Climate Law, 2, 159–179.

- Terpstra, T. (2011). Emotions, trust, and perceived risk: Affective and cognitive routes to flood preparedness behavior. Risk Analysis, 31(10), 1658–1675.

- Terpstra, T., & Gutteling, J. M. (2008). Households’ perceived responsibilities in flood risk management in The Netherlands. International Journal of Water Resources Development, 24(4), 555–565.

- VNG. (2007). Van rioleringszaak naar gemeentelijke watertaak: de wet gemeentelijke watertaken toegelicht. Retrieved from http://www.rotterdam.nl/GW/Document/Waterloket/Van%20rioleringszaak%20naar%20gemeentelijke%20watertaak.pdf

- Wachinger, G, Renn, O, Begg, C, & Kuhlicke, C. (2013). The risk perception paradox -implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Analysis, 33(6), 1049-1065.

- Ward, P. J., Pauw, W. P., van Buuren, M. W., & Marfai, M. A. (2013). Governance of flood risk management in time of climate change: The cases of Jakarta and Rotterdam. Environmental Politics, 22(3), 518–536.

- Watermonitor. (2009). Inzicht in waterbewustzijn van burgers en draagvlak voor beleid (Intomart GfK bv, projectnummer 22265).

- Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, an introductory analysis (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CO & London: Sage.

- Yohe, G., & Tol, R. S. J. (2002). Indicators for social and economic coping capacity: Moving toward a working definition of adaptive capacity. Global Environmental Change, 12, 25–40.