Encounter is a central feature of urban life (Fincher & Iveson, Citation2008) and the ‘throwntogetherness’ (Massey, Citation2005) of people in the tight quarters of the city is credited with many social goods, from reducing bigoted views of ‘the other’ (Allport, Citation1985; Mayblin, Valentine, Kossak, & Schneider, Citation2015) to activating local places and their economies (Knack & Keefer, Citation1997) to creating more positive impressions of safety and security (Jacobs, Citation1992; Zelinka & Brennan, Citation2001). Arguably, it is the core business of planners to be understanding, facilitating and improving of the contact people have with each other in cities and neighbourhoods.

There are, however, identities that are ‘unspeakable’ (Grant-Smith & Osborne, Citation2016) and that challenge even the boldest advice regarding encounter as a building block to community cohesion, place making and the development of social capital. Among those identities are people who inject drugs, particularly when they inject drugs in the public realm.

The illicit nature of drug taking as well as the visceral aspects of injecting drug use combined with the common intersectionality of drug taking identities (with, for example, homelessness and mental illness) render people who inject drugs as “deviant, odd, strange, or criminal” and the encounter with them as “abhorrent, embarrassing, disgusting, unwelcome” (Grant-Smith & Osborne, Citation2016, p. 46). This ensures that these sorts of encounters between strangers are “encaged within discourses of ‘contamination’, ‘criminality’ and ‘public danger’ to the desired ‘order of things’” (Yiftachel, Citation2009, p. 89).

These narratives about injecting drug use mean that encounters between people who inject drugs and those who do not are often uncomfortable and tense. While the non-users feel at risk of violence and struggle with the sometimes chaotic social cues of people using drugs publicly, encounter also ensures that the very disadvantaged in society “are reminded of their deprivation on a daily basis” (Dikeç, Citation2017, p. 4).

This contribution engages with these tensions of encounter involving ‘unspeakable’ identities in our cities, using the experiences of an applied research case study in Melbourne, Australia. The article focuses on ways in which storytelling might act as an initial ‘proxy’ encounter in such challenging meetings. Instead of policing these encounters (ineffectively), can planning respond with approaches to public space use and encounter that help citizens question the “stereotyped expectancies about what stigmatized people are like” (Miller, Citation2006, p. 21)? Can the tales we tell about each other shift through hearing the tales we share of ourselves?

Encounters in Victoria Street, North Richmond

The tensions described above are contemporary tensions in the Victoria Street precinct of inner-city Melbourne, Australia. The neighbourhood is marked by hyper-diverse socio-economic and ethno-cultural populations, with public housing tenants living next door to wealthy gentrifiers and the Vietnamese migrants who created Victoria Street’s ‘Little Saigon’ identity living alongside those of multi-ethnic backgrounds. Very different lives are being led by immediate neighbours in this area.

The most polarising of these diversities, though, is Victoria Street’s association with the illicit drug market (and the heroin market in particular). This association is long-standing and durable and, as other drug markets in the metropolitan Melbourne area have shrunk and/or been displaced, the Victoria Street market has flourished, with tragic results for some. In 2016, 36 people died of drug overdoses in the Victoria Street neighbourhood, with roughly 70% of those deaths occurring in the public realm (Coroners Court of Victoria, Citation2017).

Not surprisingly, the drug market aspect of the neighbourhood absorbs the attention of the media, the community and various planning authorities, service providers and politicians particularly in the lead up to and time since the opening of Victoria’s first medically supervised injecting room (MSIR) in the area. The stories of the neighbourhood often revolve around the relationships and encounters that very different people have with those engaged in public drug-taking (or in activities/behaviours perceived to be drug-related).

These encounters are made even more visceral by the built form of the area (): narrow footpaths, dense living, a highly pedestrianised local population and trading and street furniture arrangement all lead to very close and sensory encounters with strangers in the street. These local encounters are a ‘dance’ in which two worlds collide and are pressed up against one another before parting and getting on with the very different errands that bring people to the neighbourhood. Such encounters may not offer the ‘meaningful’ contact that “breaks down prejudices and translates beyond the moment to produce a more general respect for others” (Mayblin et al., Citation2015, p. 67). Brief encounters may, in fact, act to reinforce the stereotypes and stigmas applied to the different people of the neighbourhood, reducing the neighbourhood to crudely drawn groups: gentrifiers and junkies, hipsters and migrants, Anglos and Asians.

A Storytelling Experiment

As part of a larger research project, a small story-focused ‘pop up’ was held in this neighbourhood in April 2018. The larger research involved the author as a University of Melbourne researcher working with local institutions (including research partners, the City of Yarra, the Neighbourhood Justice Centre and the Yarra Drug and Health Forum) to explore how ideas of restorative justice might be applied to larger urban contestation and conflict. The ‘pop up’ was an experimentation to this end and its lessons, for the agency and community people involved, were both unexpected and profound.

About 20 stories were gathered by the agency and researcher partners at the ‘pop up’, held in a small neighbourhood park over an afternoon. Stories were shared by people living on the street and those using drugs, people living in public housing, traders and residents in the private market (renting and owning). Stories included a portrait or an ‘avatar’ of the storyteller.

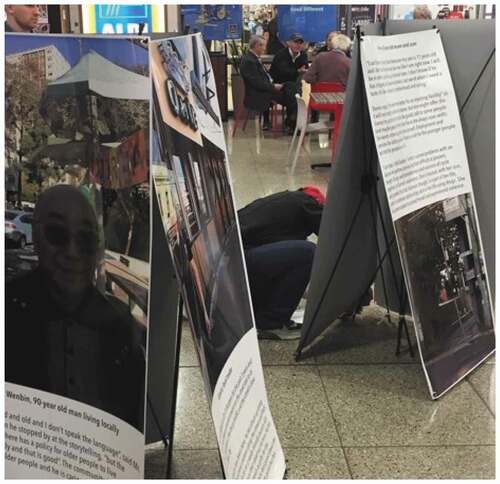

The result was a set of large banners which were exhibited at a busy local shopping centre and then at a local service provider’s community arts program. The audiences at the exhibits also represented a wide range of people from the local community and local and regional services.

Stories-as-Encounter

What was powerful (and potentially very useful for practitioners engaged in planning amongst communities of difference) was ways in which storytelling became a proxy for encounter between the very different communities of the Victoria Street neighbourhood.

The gathering of stories itself provided a physical, and a social/psychological space where people were able to encounter each other in a somewhat mediated way. Local service providers were present, providing some (non-clinical) structure to the encounters for those from the street. And the story gathering also reclaimed open space typically abandoned to ‘unspeakable’ uses, prompting different people to join in and mingle with each other and with the institutional authority of the research partners. Researchers noticed the “brief little interactions between different members of the community” during the day (source: author’s interview notes)

For many, the storytelling was profound in relation to the complexity of people’s lives and stories and in relation to the trust that sharing such stories involved. Even those practitioners with a great deal of experience working with community members in the area found they were interacting with people/groups they didn’t know as well. For example, the outreach staff who worked mainly with people living on the street had an opportunity to speak with middle class, waged and housed people. The policy making and public servant practitioners had an opportunity to speak directly with the disadvantaged who are often too ‘hard to reach’ via conventional engagement techniques (Brackertz, Zwart, Meredyth, & Ralston, Citation2005). As a result, several practitioners described their experience as revelatory, moving or cathartic on a personal and professional level, illustrating the power of encounter and the role that interpersonal connection can play in reducing stigma. However, the more profound (and unexpected) experience of encounter for community seemed to happen during the exhibiting of the stories.

Many people on their regular business in the shopping centre (getting groceries, etc.) stopped and read the stories (). There was a very ‘care-full justice’ (Williams, Citation2017) exhibited by a wide range of people: from the two local residents who stopped off to ask more about the story gathering, as they were interested in its application to their own practices, to the itinerant man who spent time on his hands and knees in the shopping centre, caring for and fixing the banners (), to the many who simply stopped and discussed the different stories – and what they represented – with each other and with the researchers.

Occasionally, a person engaged with the exhibit and the researchers staffing it in a confrontational way. For example, one woman arrived, read the story of a person experiencing drug addiction, and exclaimed “I don’t agree with this!” to two nearby researchers. Discussion revealed that she was referring to the then-proposedFootnote1 Medically Supervised Injecting Room (MSIR). When one of the researchers asked how she ‘disagreed’ with the story, the woman did accept that you can’t really ‘disagree’ with a person’s life story/experience. It isn’t an opinion or a stance in an argument or contestation: it is simply a fact, a history and a condition.

This observation underscores why a story has the power in the contested and stigmatised aspects of urban life, like the public use of drugs and other challenging behaviours: storytelling taps into more than simply explanation. It brings expressiveness, liveliness and emotion to an understanding of someone whose experience is very different to our own (Reason & Hawkins, Citation1988). This experiment with storytelling also suggested a third way in which storytelling can act to build community, and that is through the ways in which those involved – the story gatherers, the storytellers and the story readers – are empowered, emancipated and changed through their involvement in knowledge building (Freire, Citation1998).

Enriching our typically (in planning, at least) explanatory evidence with expressive and emancipatory knowledge steers us away from the occasionally negative outcomes of evidence that dispassionately ‘classifies’ and structures people into groups: groups which may be stereotyped, stigmatised, and criminalised.

Certainly, the storytelling serves to make the ‘unspeakable’ more knowable to many whose ideas about people using drugs are shaped only by voices other than drug users themselves. In this experiment, people’s own telling of their lives proved very compelling because it tapped into the emotional and empathetic responses people had to personal story. People recognised aspects of their own lives in such stories, even when they were the stories of people very different from themselves. This was an encounter of a type – arguably a very important type – given the visceral and other barriers described earlier. We, however, agree with Bourgois and Schonberg, (Citation2009, p. 297) that “ … studying people who live under conditions of extreme duress and distress [makes it] imperative to link theory to practice. Otherwise, we would be merely intellectual voyeurs.” To conclude, then, the following are some lessons (and some questions) for future applied research in this area.

First, given that “built environment researchers … have been slow to adopt constructivist grounded theory as a research method” (Allen & Davey, Citation2018, p. 225), this research has demonstrated how storytelling can be done in a neighbourhood setting and in a manner that “creates opportunities to sharpen the study of wicked problems in contemporary cities and bridge the research-practice gap” (Henderson, Citation2016, p. 33). There is still substantial scope to expand this methodological toolkit, though, through further experimentation with applied, ethnographic research such as this. Such approaches to urban scholarship offer multiple levels of innovation, with the capacity for significant academic impact as well as generating meaningful local interventions and knowledge around more well-established planning ideas like ‘encounter’. Thus, methodological experimentation can bridge theory and practice and help practitioners change aspects of our cities (like negative encounters) which erode public life and social capital.

Second, the ‘reclaimant narrative’ and storytelling activism employed in this research is often in the service of agonist approaches to conflict (Verloo, Citation2018). Our research, however, suggests ways in which activist storytelling may also be used and useful in restorative and deliberative approaches to problem-solving. This application would seek to “actually change values and translate beyond the specifics of the individual moment into a more general positive respect for – rather than merely tolerance of – others” (Valentine, Citation2008, p. 325), which needs more exploration.

As a method, what would deliberative, reclaimant storytelling look like and require? The story gathering could be done as a group discussion, tapping into a more deliberative mode of communicating. The prompts for the storytelling could also be more explicitly about values (and tensions, opportunities, visions, etc.) as a means of using storytelling to start a problem-solving dialogue in a neighbourhood. Finally, stories and storytelling are a methodological stepping stone and need to lead to a space (physical, social and discursive) where a deeper and more sustained encounter can occur. Without such a progression, applied research again risks being ‘intellectual voyeurism’, and the community left back where it began, struggling for meaningful contact across difference.

There are various kinds of spaces where evolving encounter might occur. Piekut and Valentine (Citation2017, p. 177) have developed and tested a typology of spaces of encounter, including public space (e.g. streets, parks or public transport), institutional space (like schools, Council and workplaces), socialisation space (e.g. the meeting spaces of social or religious groups) and consumption space (cafes, bars, restaurants, and clubs). While their research has found that socialisation and consumption spaces are most efficient in seeding meaningful encounter, there are also some barriers to ‘unspeakable’ encounter in such spaces. For example, how can the poor access consumption space without being subsidised?

The public realm offers the most realistic opportunity for following up with deepened encounter, just as it played a vital role in hosting the initial storytelling. This is not challenge-free, however, as power relations will continue to render some identities ‘unspeakable’ and highly stigmatised. Ongoing encounter will need mediation support if it is to be meaningful and emancipatory.

The application of storytelling to such ‘unspeakable’ encounter is promising, both for theory and practice. The synergies between storytelling and encounter tap into an elemental human interest in telling and hearing stories about lives and in using stories to better know and understand strangers. Stories are universal and a part of all cultures; they work as a communication form for people of wide age ranges and cognitive dispositions. In using the term ‘unspeakable’ in reference to certain identities, like people who inject drugs in the public realm, there is an implied understanding that some stories are not spoken and shared. This view can and should be challenged. Story-as-encounter has the possibility of being/feeling like a safer starting point for people because it exposes and blurs the socially constructed boundaries between self and Other and shifts the discussion about “what is allowed where, and what can be openly spoken of” (Grant-Smith & Osborne, Citation2016, p. 50). In this respect, it is not simply a good method for participants in urban research, it is a potentially indispensable tool for planners who must grapple with the social, spatial and civic repercussions of ‘unspeakable’ issues in our cities and neighbourhoods.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contributions of all the neighbourhood storytellers, the other research participants and the research partners from industry with profound thanks. Human research ethics approval was granted by the University of Melbourne on 13 October 2017, reference #1647851.2.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrea Cook

Andrea Cook is an urban and regional planner specializing in strategic and community planning, in both academic and practice-based environments. Andrea has taught and researched at the University of Melbourne since 2010 and has been the Director of RedRoad Consulting since 1998. Andrea’s interests lie in ‘rights to the city’, urban contestation, participatory and deliberative planning/policy/design, the ethics of planning work and applying creative methodologies to support more robust understandings of the city.

Notes

1. The Victorian State government announced a two-year trial of a Medically Supervised Injecting Room (MSIR) in December 2017, the exhibit was in April 2018 and the MSIR trial commenced in July 2018.

References

- Allen, N., & Davey, M. (2018). The value of constructivist grounded theory for built environment researchers. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 38, 222–232.

- Allport, G. W. (1985). The nature of prejudice ( Nachdr ed.). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Bourgois, P. I., & Schonberg, J. (2009). Righteous dopefiend, California series in public anthropology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Brackertz, N., Zwart, I., Meredyth, D., & Ralston, L. (2005). Community consultation and the ‘hard to reach’: Concepts and practice in Victorian local government. Melbourne: Swinburne University of Technology, Institute for Social Research.

- Coroners Court of Victoria. (2017). Submission to the inquiry into drug law reform. Melbourne: Author.

- Dikeç, M. (2017). Urban rage: The revolt of the excluded. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Fincher, R., & Iveson, K. (2008). Planning and diversity in the city. London: Macmillan Education UK. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-06960-3

- Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage, critical perspectives series. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Grant-Smith, D., & Osborne, N. (2016). Dealing with discomfort: How the unspeakable confounds wicked planning problems. Australian Planner, 53, 46–53.

- Henderson, H. (2016). Toward an ethnographic sensibility in urban research. Australian Planner, 53, 28–36.

- Jacobs, J. (1992). The death and life of great American cities ( Vintage Books ed.). New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 1251–1288.

- Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, London.

- Mayblin, L., Valentine, G., Kossak, F., & Schneider, T. (2015). Experimenting with spaces of encounter: Creative interventions to develop meaningful contact. Geoforum, 63, 67–80.

- Miller, C. (2006). Social psychological perspectives on coping with stressors related to stigma. In S. Levin & C. Van Laar (Eds.), Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 21–44). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Piekut, A., & Valentine, G. (2017). Spaces of encounter and attitudes towards difference: A comparative study of two European cities. Social Science Research, 62, 175–188.

- Reason, P., & Hawkins, P. (1988). Storytelling as inquiry. In P. Reason (Ed.), Human inquiry in action: Developments in new paradigm research (pp. 79–101). London: Sage.

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32, 323–337.

- Verloo, N. (2018). Social-spatial narrative: A framework to analyze the democratic opportunity of conflict. Political Geography, 62, 137–148.

- Williams, M. J. (2017). Care-full justice in the city: Care-full justice in the city. Antipode, 49, 821–839.

- Yiftachel, O. (2009). Theoretical notes on `gray cities’: The coming of urban apartheid? Planning Theory, 8, 88–100.

- Zelinka, A., & Brennan, D. (2001). SafeScape: Creating safer, more livable communities through planning and design. Chicago, IL: Planners Press, American Planning Association.