This commentary centres on the question – how can we further develop the relationship between planning practice and academia? This question has been one of the central pillars of planning scholarship over several decades (Krumholz, Citation1986), but many would agree that previous arguments have not yet been taken far enough in action. Drawing upon the web of existing arguments for a closer theory-practice relationship, our intent is to unpack additional experiential dimensions of this overarching question that need to be understood in a relational manner. Any such understanding should be placed in the context of non-collaborative pressures in both practice and academia, and open new pathways for understanding structural barriers to their closer collaboration. To this end, we will start by explaining the demanding contexts that planning now faces. We then reflect on how planning in itself is a complex procedural practice. The central premise here is that planning is institutional, but ultimately a human action at its core, that is characterised by psychosocial dynamics that need to be accounted for. Advancing this argument, we will acknowledge previous reflections on psychosocial aspects of planners’ everyday. Arguing from inference, we conclude that furthering collaboration between practice and academia will require understanding the diverse and dynamic experiences of planners whose everyday practices are embedded within complex psychosocial processes, distributed across various social networks and time. Bearing in mind these deeper understandings of planning as a complex and deeply emotional practice, we reflect on potential actions for developing co-creation processes that engage both practice and academia.

Of Wicked Problems and Planning Complexities

In light of the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report (IPCC, Citation2019), humanity has to face the fact that wicked problems, highlighted decades ago (Rittel & Webber, Citation1973), still hang above us like Damocles’ sword. We live on a limited planet, where resources are often scarce compared to current human needs (Raworth, Citation2012). Moreover, natural, infrastructural, and technological systems have a large number of interdependent relations, resulting in a non-linear and rapidly changing reality (de Roo & Silva, Citation2010; Sengupta, Rauws, & de Roo, Citation2016). At the centre of this existential understanding is the idea that multidimensional human ends are not static and fully defined, and that various groups have different needs, over time. Thus, transitions out of our unsustainable lifestyles require not only changes in the built environment and technological systems but, most importantly, in our behaviours and societal values (Geels, Sovacool, Schwanen, & Sorrell, Citation2017). However, this state of irreducibly high uncertainty creates huge difficulty for any attempts to define and predict the consequences of our planning actions. This is why societal transitions will ultimately also require a transition in our planning institutions, and their multiple ways of (un)learning over time (Albrechts, Barbanente, & Monno, Citation2019; Baum, Citation1999).

Considering the potential to transform multi-actor planning institutions, let us focus on one set of central actors – spatial planners. After all, can there be “theory” of planning if one does not fully understand one of the essential objects of that theorisation – “the planners”? Here, we recognize that this is not a uniform group of people, as role diversification and multi-tasking continue to develop (Krumholz, Citation2007). Nonetheless, what expectations do we academics express in our writings for planners as civil servants? Bluntly put, it sometimes seems we expect them to be near superhuman (Abram & Cowell, Citation2004; Inch, Citation2010). We certainly expect them to embrace the complexity of our humanity and the wickedness of our environments by developing a systems and strategic thinking mindset (Byrne, Citation2003; Chettiparamb, Citation2006; de Roo & Silva, Citation2010; Healey, Citation2010; Innes & Booher, Citation2010; Sengupta et al., Citation2016), reflecting continuously over time (Kitchen, Citation2007). To name a few expectations, we academics ask for sustainability that balances economic, environmental, and social dimensions in cities as well as delivering just outcomes for current and future generations (Healey, Citation2007; Kenny & Meadowcroft, Citation2002). At the same time, we ask for balance between the competing needs of various actors, and compassionate planning (Lyles, White, & Lavelle, Citation2017). Moreover, we ask for wise trade-offs, such as tackling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while catering for citizens’ wellbeing and fighting off neoliberal forces (Grange, Citation2017; Olesen, Citation2014; Sager, Citation2009). Nearly every academic publication has some piece of advice for planners – be flexible but guiding, think about the long-term but act in the now, understand multidimensional and dynamic human behaviour, find and remember comprehensive information, be ready for communicative and co-creative mediation with a wide range of stakeholders … The list could go on.

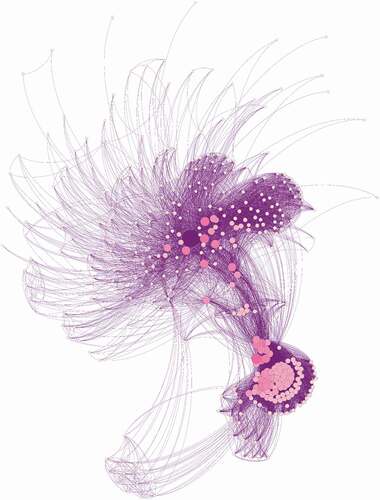

Such expectations and advice for planners draw on decades of analysis of wicked challenges in our built environments. In addition, scholarship has aimed to open the black box of, often siloed, planning institutions (De Leo & Forester, Citation2017; Salet, Citation2018). By now, we acknowledge that planning institutions are complex, emergent phenomena, happening on multiple scales, underpinned by the dialectics of structure and agency playing out as dynamic social practices (Jessop, Citation2001). However, do we fully understand the extent of temporal and organizational complexity, especially at the level of everyday activities within multi-actor, multi-scale, multi-year planning processes? One quick glance at below scratches the surface of this procedural complexity, developing over several years and in several organizations. Here, we can see the number of actors involved in an actual spatial planning process in Finland, represented by nodes, and connected by ties where these individuals have been in the same meeting together (Eräranta, Citation2019). What this figure shows is just a snapshot of the total number of actors involved, but it also shows the differences in their relations. Such relations define roles for different individuals within the network, shaping knowledge co-creation and process memory, ultimately highlighting the procedural complexity of spatial planning. Keeping in mind such a wide set of actors, one can only start to imagine the psychosocial dynamics that have been involved over several years, as knowledge was co-created in these meetings. Understanding such procedural complexity is daunting, but we cannot avoid the fact that planning processes are ultimately human processes. Planning for multidimensional humans is done by other multidimensional humans, thus shaping how organizational (un)learning and institutional transformation unfold in particular planning contexts.

Figure 1. The cumulative actor-relation network of one spatial planning process in Finland (Eräranta, Citation2019)

Planners as (Multidimensional and Relational) Beings?

Voilà! Planners are humans! However, this basic fact is not as simple as it might sound at first. How much of planners’ everyday human psychosocial reality within institutional structures do we actually understand? Planning research has been concerned for decades with what planners do (Hoch, Citation1994; Kitchen, Citation1997; Krieger, Citation1975; Udy, Citation1994). On the one hand, such concern had led to conceptual discussion on the roles and values of practicing planners (Fox-Rogers & Murphy, Citation2016; Hoch, Citation1988; Howe, Citation1980; Howe & Kaufman, Citation1979; Lauria & Long, Citation2017; Sehested, Citation2009). On the other hand, there is an accompanying discussion on dissonance between planners’ institutional roles and their personal values (Campbell & Marshall, Citation1998, Citation2002; Dalton, Citation1990; Mayo, Citation1982; Puustinen, Mäntysalo, Hytönen, & Jarenko, Citation2017; Zanotto, Citation2019). However, large-scale and comparative empirical studies on planners’ everyday lives remain rare (Birch, Citation2001; Dalton, Citation2007; De Leo & Forester, Citation2017; Fischler, Citation2000; Forester, Citation1983, Citation1989, Citation2012; Healey, Citation1992; Johnson, Citation2010; Kaufman, Citation1985; Kaufman & Escuin, Citation2000; Krumholz & Forester, Citation1990; Majoor, Citation2018; Rodriguez & Brown, Citation2014), including few personal accounts from practitioners themselves (Dalton, Citation2015; Kitchen, Citation1997; Tasan-Kok et al., Citation2016). These studies, especially those developed or inspired by John Forester’s pioneering work have done a great deal to gather and tell ‘practice stories’, illuminating several aspects of complex planning processes, and different everyday planning activities. They show us how practitioners muddle through challenging policy agendas in difficult political contexts. Such understanding of planners’ everyday activities has been important in moving away from the traditional rational model of planning, recognizing that knowing and acting (Davoudi, Citation2015), as well as knowing and feeling, are closely interwoven (Westin, Citation2016). Although emotional dimensions of these everyday experiences are mentioned in some studies of planners’ values, only recently has planning scholarship explicitly discussed the integral role of emotions in planners’ activities (Barry et al., Citation2018; Baum, Citation2015a; Ferreira, Citation2013; Hoch, Citation2006; Lyles et al., Citation2017; Porter et al., Citation2012).

Psychoanalytical theories have become a more important strand underlying the development of planning theory (Baum, Citation1999, Citation2011; Talvitie, Citation2009). The studies and writings of Howell Baum have pointed to the unconscious, psychological underpinnings of organizational processes, how they can hinder problem identification, and capacity for analysis and decision-making (Baum, Citation1987). Moreover, Baum has identified how certain aspects of group phenomena and social structures affect capacities for reflection on the exercise of power, leading to the overall conclusion that thinking and action in planning are based on passions, anxieties, and fantasies as well as reason (Baum, Citation2011, Citation2015b). Similarly, following post-Freudian strands of psychoanalysis, Gunder and Hillier on the one hand (Gunder, Citation2003, Citation2010; Gunder & Hillier, Citation2016), and Westin on the other (Westin, Citation2011, Citation2016), conceptualize the role of identification, fantasy and (un)conscious beliefs in shaping the ideological knowledge claims through which power is often distributed in planning processes. Despite these conceptualizations, only one in-depth, empirical study has focused on a particular emotion planners’ feel – fear (Sturzaker & Lord, Citation2017). Thus, the planning field’s theoretical concepts still rely on a limited relation to the field of psychological studies, with limited empirical cases lacking longitudinal studies of planning process dynamics.

Given that studies about planners’ everyday psychosocial reality remain limited, what else might be left undiscovered? It is reasonable to assume that the everyday life of planners – being part of long-term planning processes – is filled with various emotions and social relations. Providing an example of anxieties, Baum describes the feeling of insufficiency and burden, especially when one has to be in a constant state of aporia (Sartre, Citation1956), facing the wickedness of planning problems on a daily basis. It is almost an everyday situation for planners to hear that they should have considered additional aspects, perspectives and knowledges, while also saving more time and resources, or presenting information in a more comprehensible and comprehensive manner. If we just take a moment to reflect on feelings of insufficiency to which this might give rise, we will quickly realize that this emotion is underpinned with paradoxes. For example, a planner is supposed to consider new information, but not too much information. A planner should consider a wide range of alternatives, but also not waste too much time on generating alternatives. A planner should be a generalist and broad thinker, while accounting for many details of the planning context. The list of paradoxes and challenging dilemmas goes on, and one would start to wonder if the claim that planners display a God complex (Clinch, Citation2006) might actually turn out to be quite the opposite. Ironically perhaps, but one could argue that even if we would put Plato in the position of a planner for a couple of weeks, he would be left perplexed, with a constant feeling of “knowing nothing” despite being asked and held responsible for action. Asking anyone to live in such a constant state of aporic puzzlement might raise enough existential questions to make even Sartre uncomfortable.

Nonetheless, the multidimensional psychosocial underpinning of planners’ everyday experiences do not end with an aporic sense of burden and underachievement. Everyday planning activities, as one could reasonably guess – like any other aspect of human life – involve a wide range of deeply emotional states and human-to-human relations. To borrow from a more recent model of human emotions than the Freudian approach, such experiences can vary in valence, as the extent of pleasure, ranging between positive and negative, and activation, as arousal by environmental stimuli ranging between activated and deactivated (Russell, Citation1980). For example, in educational activities, we often try to exemplify for our students the pride of being a planner, stemming from the sense of joy when certain long-sought planning objectives are achieved. This could be considered as a state of high activation and high pleasantness. By contrast, it is not rare for planners’ everyday to be filled with irritation, frustration, distress, and long-term fatigue, often resulting in a state of high deactivation and unpleasantness. The list goes on to potentially include such emotional states as astonishment, delight, content, calmness, boredom, gloominess, misery, distress, annoyance, frustration, and anger. More than this, it is not just the existence of this variety of emotional states, but also that individual planners might have to jump from highly pleasant to unpleasant states of mind from one hour to the next in the course of a single day. Finally, as we know that planners think and act as members of groups and communities, (Baum, Citation1987, Citation2015b), relational, in addition to affective, dimensions of knowledge production need to be understood (Barry et al., Citation2018).

Such everyday psychosocial dynamics embedded in various social networks have long-term consequences for the psychosocial fabric and affect of planning institutions. As we know from the field of organizational studies, emotions play a central role in influencing individual cognition and behaviour (Brief & Weiss, Citation2002; Huy, Citation1999, Citation2012), as well as the associated formation of social identity and group mood (Adams & Anantatmula, Citation2010). Without deeper understanding of these dynamic emotions embedded in social networks (Chen & Huang, Citation2007), hand in hand with an appraisal of the structural limitations facing the planning institutions where those feeling planners are embedded (Osborne & Grant-Smith, Citation2015), a strategic transition in planning will be very hard to accomplish. If we fail to understand these important aspects of organizational (un)learning, institutional transformation will overlook organizational governance approaches for dynamic and interactive change (Ansell & Trondal, Citation2018). At the root of the change in understanding of planners’ everyday lives, lies a shift from an ontology of being to an ontology of becoming, continuing a commitment to the unsettling of our ways of knowing in planning (Barry et al., Citation2018). Thus, instead of focusing on end-states, institutional transformation would account for both the subconscious and revealed socio-emotional relations (Albrechts et al., Citation2019), shaping perceptions, understanding, intentions, and commitment (Hoch, Citation2017). Emphasis on actions, relations, and emergence in long planning processes would cast a different light on planners’ desires and anxieties, asking from us not only to understand points of failure and blind sides, but also that which cannot be spoken (Žižek, Citation1997). This would mean truly understanding other human’s lifeworlds, and maybe even lead us academics to question our own emotional experiences in academia alongside understanding those of planners.

All that Remained Was Hope … and Action?

Let us go back to the wicked challenges of our times, where we started this reflection. We are desperate for action, and there is no way out of that responsibility. Together, practitioners and academics could be stronger in urgently tackling the major challenges we collectively face. In this context, as many of us, including this journal, recognise learning between practice and academia is essential for responsible action (Baum, Citation1997; Watson, Citation2002). In the founding year of Planning Theory & Practice, Thompson questioned whether the climates of both academia and practice encouraged their interaction (Thompson, Citation2000). We already know some of the key aspects to act upon collectively, if we are to foster collaboration and mutual respect between practice and academia (Vogelij, Citation2015). As one particular example, planning researchers should leave their comfortable positions as disinterested commentators, highlighting failings and inconsistencies (Campbell, Citation2014). Moreover, Thompson suggested avoiding any solidification of the impenetrability that can discourage practitioners from reading planning theory publications. Another of the low-hanging fruit is further advancement in dissemination channels, beyond classical journal publications, if we are to expand the notion of engaged scholarship (Campbell, Citation2012). These new channels, such as policy briefs and blogs, paired with social media dissemination, could be quite effective in knowledge exchange, as long as they are not abused to show a false sense of societal engagement.

In addition to some of these existing suggestions, the transition of planning institutions will require the rethinking of research methods in relation to practice. After all, how is one to learn from practice and address important challenges if one does not have ways to observe and experience the full extent of the complexity of planners’ everyday work? In particular, there is a need to continue use and exploration of action-research methodological toolkits, as part of furthering reflection on engagement with practice, and understanding practitioners’ stories (Balducci & Bertolini, Citation2007). Furthermore, to advance planning research methods, there is a need to understand planning processes in-situ and in-tempo, as they are actually unfolding. New methodological approaches are needed to foreground many of the psychosocial aspects of planning episodes as they are unfolding, as opposed to macroscopic understanding of planning processes, often done years after their completion. Mixed methods, such as interviews, focus groups and surveys combined together with more visual-analytical methods, capable of uncovering distributed procedural complexity, such as complex network analysis, are one potentially fruitful avenue for further exploration (Dempwolf & Lyles, Citation2012; Eräranta, Citation2019). The use of such proven methods within planning processes themselves could be beneficial for unravelling many psychosocial dimensions of procedural and collaborative dynamics over extensive periods, especially due to their capacity to provide for deeper understanding of (the lack of) process memory (Eräranta & Mladenović, Citationin review). Moreover, understanding the multitude of existing roles and relations within planning processes would also help better define the role of academia, the types of relations required, and their timing with respect to practice. Besides the evolution of research methods, we will also have to question the criteria for peer-based assessment of action-research narratives (Saija, Citation2014).

If mixed and action-oriented methods are being adopted, academics and practitioners will need to learn how to develop initial trust to even initiate such action-research processes. In relation to the question of trust, we have to ask ourselves whether the required changes in planning institutions can happen without parallel changes in the attitudes and identities of both practitioners and academics, and ultimately changes in the ways they relate. Opening this Pandora’s box may entail facing difficult, existential questions. Similar to the mind-set required to embrace the complexity of a wide variety of the natural, technological, and social systems framing citizens’ everyday lives, the challenges might also lie in understanding the dialectic interdependence between emphatic attitudes and research methods and questions. On one side of this issue, one would need to acknowledge the difference between compassion and empathy. Respect and trust from both sides cannot rely on sympathetic pity for planners’ plight. This would build a relationship on very unhealthy grounds, eventually resulting in further misunderstanding and potentially trust-breaking conflict. By contrast, empathy would mean a willingness to understand the planners’ struggle, on the level of individual and long-term experiences. In addition, planning researchers have to stop treating practitioners solely as research “subjects” or even worse, “channels” for providing data and funding. Potentially in tenure promotion criteria, or even in personal reflection about one’s own success as a planning researcher, one can ask a straightforward question – how many practicing planners do you collaborate with on the basis of trust and respect? Answering this question would require placing higher emphasis in academic evaluation on societal significance alongside scientific excellence, but it might also be a way to prompt reflection on long-term institutional development.

On the other side of the table, practitioners need to be emotionally ready for a period of (un)learning, if they open the doors to academics. A large-scale cultural change towards collegiality and reflection leading to action has to recognize also differences in terms of skill-sets between practice and academia. This certainly also requires empathy – in this case for academia. Practitioners need to understand that researchers are similarly often struggling with limited and diminishing resources, pushed towards non-cooperative and competitive behaviour by modern funding schemes, and facing constant demands to provide better education. Moreover, understanding academic struggles involves understanding the limits of university structures, which often draw on performance indicators unrelated to planning practice (Krumholz, Citation1986), such as numbers of citations. Both sides need to talk about mismatches in the time horizons within which they operate, and missing channels for information flows. Previous suggestions have focused on the potential for movement between the sectors based on secondments, placements, partnerships or more flexible career paths (Thompson, Citation2000), as well as establishing positions for professors of planning practice who would specifically work closely with practitioners (Clinch, Citation2007). These organizational changes would also imply reflecting on alternative co-funding mechanisms, where collaboration between practice and academia requires a different approach from across different societal domains. Furthermore, it might be useful to consider mentoring programs for young planning researchers, where, in addition to academic supervision, doctoral researchers also have an advisor from planning practice. In many contexts, it might be advisable to start with small but regular activities, such as two-hour meetings twice a year, where practitioners and academics can present their ongoing activities, and provide each other with feedback. These apparently minor activities could be essential for gradual (un)learning and trust building. Reconsideration of relations between civil servants and academics could also help them reconsider their relations to other planning actors, such as citizens or politicians. Ultimately, we might all need to accept, perhaps with some surprise, that further development of practice- academic relations would inevitably force us to address the apparently simple yet simultaneously grand question – what does it mean to be human?

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Andy Inch and Crystal Legacy for their valuable comments on the two earlier versions of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Miloš N. Mladenović

Miloš N. Mladenović, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Spatial Planning and Transportation Engineering research group at the Aalto University. His research interests include development of decision-support concepts, methods, and organisational practices for a human-centred built environment.

Susa Eräranta

Susa Eräranta, D.Sc. (Tech.), is a researching practitioner working with urban planning topics. Her research interest is in analysing human-related perspectives of complex spatial planning processes.

References

- Abram, S., & Cowell, R. (2004). Dilemmas of implementation: ‘integration’ and ‘participation’ in Norwegian and Scottish local government. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 22(5), 701–719.

- Adams, S. L., & Anantatmula, V. (2010). Social and behavioral influences on team process. Project Management Journal, 41(4), 89–98.

- Albrechts, L., Barbanente, A., & Monno, V. (2019). From stage-managed planning towards a more imaginative and inclusive strategic spatial planning. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(8), 1489–1506.

- Ansell, C., & Trondal, J. (2018). Governing turbulence: An organizational-institutional agenda. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 1(1), 43–57.

- Balducci, A., & Bertolini, L. (2007). Reflecting on practice or reflecting with practice? Planning Theory & Practice, 8(4), 532–555.

- Barry, J., Horst, M., Inch, A., Legacy, C., Rishi, S., Rivero, J. J., … Zitcer, A. (2018). Unsettling planning theory. Planning Theory, 17(3), 418–438.

- Baum, H. (1987). The invisible bureaucracy: The unconscious in organizational problem solving. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Baum, H. (1997). Social science, social work, and surgery: Teaching what students need to practice planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 63(2), 179–188.

- Baum, H. (1999). Forgetting to plan. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(1), 2–14.

- Baum, H. (2011). Planning and the problem of evil. Planning Theory, 10(2), 103–123.

- Baum, H. (2015a). Planning with half a mind: Why planners resist emotion. Planning Theory & Practice, 16(4), 498–516.

- Baum, H. (2015b). Discovering and working with irrationality in planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(1), 67–74.

- Birch, E. L. (2001). Practitioners and the art of planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 20(4), 407–422.

- Brief, A. P., & Weiss, H. M. (2002). Organizational behavior: Affect in the workplace. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 279–307.

- Byrne, D. (2003). Complexity theory and planning theory: A necessary encounter. Planning Theory, 2(3), 171–178.

- Campbell, H. (2012). Lots of words … but do any of them matter? The challenge of engaged scholarship. Planning Theory & Practice, 13, 349–353.

- Campbell, H. (2014). The academy and the planning profession: Planning to make the future together? Planning Theory & Practice, 15(1), 119–122.

- Campbell, H., & Marshall, R. (1998). Acting on principle: Dilemmas in planning practice. Planning Practice & Research, 13(2), 117–128.

- Campbell, H., & Marshall, R. (2002). Values and professional identities in planning practice. In P. Allmendinger and M. Tewdwr-Jones (Eds.), Planning futures: New directions for planning theory (pp. 93–109). London: Routlege.

- Chen, C. J., & Huang, J. W. (2007). How organizational climate and structure affect knowledge management - The social interaction perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 27(2), 104–118.

- Chettiparamb, A. (2006). Metaphors in complexity theory and planning. Planning Theory, 5(1), 71–91.

- Clinch, J. P. (2006). Do planners need to be psychologically profiled? Planning Theory & Practice, 7(4), 361–364.

- Clinch, J. P. (2007). Academia, applied research and the planning profession. Planning Theory & Practice, 8(4), 423–426.

- Dalton, L. C. (1990). Planners in conflict: Experience and perceptions in California. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 7(4), 284–302.

- Dalton, L. C. (2007). Preparing planners for the breadth of practice: What we need to know depends on whom we ask. Journal of the American Planning Association, 73(1), 35–48.

- Dalton, L. C. (2015). Theory and practice, practice and theory: Reflections on a planner’s career. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(4), 303–309.

- Davoudi, S. (2015). Planning as practice of knowing. Planning Theory, 14(3), 316–331.

- De Leo, D., & Forester, J. (2017). Reimagining planning: Moving from reflective practice to deliberative practice-a first exploration in the Italian context. Planning Theory & Practice, 18(2), 202–216.

- de Roo, G., & Silva, E. A. (Eds.). (2010). A planner’s encounter with complexity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Dempwolf, C. S., & Lyles, L. W. (2012). The uses of social network analysis in planning: A review of the literature. Journal of Planning Literature, 27(1), 3–21.

- Eräranta, S. (2019). Memorize the dance in the shadows? Unriddling the networked dynamics of planning processes through social network analysis (Doctoral dissertation). Aalto University, Espoo.

- Eräranta, S., & Mladenović, M. N. (in review). The impact of actor-relational dynamics on integrated planning practice. Transactions of the Association of European Schools of Planning.

- Ferreira, A. (2013). Emotions in planning practice: A critical review and a suggestion for future developments based on mindfulness. Town Planning Review, 84(6), 703–719.

- Fischler, R. (2000). Case studies of planners at work. Journal of Planning Literature, 15(2), 184–195.

- Forester, J. (1983). The geography of planning practice. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 1(2), 163–180.

- Forester, J. (Ed.). (1989). Understanding planning practice. In Planning in the face of power (pp. 137–62, 236–246). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Forester, J. (2012). Learning to improve practice: Lessons from practice stories and practitioners’ own discourse analyses (or why only the loons show up). Planning Theory & Practice, 13(1), 11–26.

- Fox-Rogers, L., & Murphy, E. (2016). Self-perceptions of the role of the planner. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(1), 74–92.

- Geels, F. W., Sovacool, B. K., Schwanen, T., & Sorrell, S. (2017). Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science, 357(6357), 1242–1244.

- Grange, K. (2017). Planners – A silenced profession? The politicisation of planning and the need for fearless speech. Planning Theory, 16(3), 275–295.

- Gunder, M. (2003). Passionate planning for the others’ desire: An agonistic response to the dark side of planning. Progress in Planning, 60(3), 235–319.

- Gunder, M. (2010). Making planning theory matter: A Lacanian encounter with Phronesis. International Planning Studies, 15(1), 37–51.

- Gunder, M., & Hillier, J. (2016). Planning in ten words or less: A Lacanian entanglement with spatial planning. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Healey, P. (1992). A planner’s day: Knowledge and action in communicative practice. Journal of the American Planning Association, 58(1), 9–20.

- Healey, P. (2007). Re-thinking key dimensions of strategic spatial planning: Sustainability and complexity. In G. de Roo & G. Porter (Eds.), Fuzzy planning: The role of actors in a fuzzy governance environment (pp. 21–42). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Healey, P. (2010). Making better places: The planning project in the twenty-first century. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hoch, C. (1988). Conflict at large: A national survey of planners and political conflict. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 8(1), 25–34.

- Hoch, C. (1994). What planners do: Power, politics, and persuasion. Chicago, IL: American Planning Association.

- Hoch, C. (2006). Emotions and planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 7(4), 367–382.

- Hoch, C. (2017). Pragmatism and plan-making. In B. Haselsberger (Ed.), Encounters in planning thought: 16 autobiographical essays from key thinkers in strategic spatial planning (pp. 297–314). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Howe, E. (1980). Role choices of urban planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 46(4), 398–409.

- Howe, E., & Kaufman, J. (1979). The ethics of contemporary American planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 45(3), 243–255.

- Huy, Q. N. (1999). Emotional capability, emotional intelligence, and radical change. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 325–345.

- Huy, Q. N. (2012). Emotions in strategic organization: Opportunities for impactful research. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 240–247.

- Inch, A. (2010). Culture change as identity regulation: The micro-politics of producing spatial planners in England. Planning Theory & Practice, 11(3), 359–374.

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. London: Routledge.

- IPCC. (2019). Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. [ Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (Eds.)]. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/download/

- Jessop, B. (2001). Institutional re (turns) and the strategic–Relational approach. Environment and Planning A, 33(7), 1213–1235.

- Johnson, B. J. (2010). City planners and public service motivation. Planning Practice & Research, 25(5), 563–586.

- Kaufman, J. L. (1985). American and Israeli planners: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of the American Planning Association, 51(3), 352–363.

- Kaufman, J. L., & Escuin, M. (2000). Thinking alike: Similarities in attitudes of Dutch, Spanish, and American planners. Journal of the American Planning Association, 66(1), 34–45.

- Kenny, M., & Meadowcroft, J. (Eds.). (2002). Planning sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Kitchen, T. (1997). People, politics, policies and plans: The city planning process in contemporary Britain. London: SAGE.

- Kitchen, T. (2007). Skills for planning practice. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Krieger, M. H. (1975). What do planners do? Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 41(5), 347–349.

- Krumholz, N. (1986). From planning practice to academia. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 6(1), 60–65.

- Krumholz, N. (2007). Multi-tasking planners. Plan Canada, 47(2), 30.

- Krumholz, N., & Forester, J. (1990). Making equity planning work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Lauria, M., & Long, M. (2017). Planning experience and planners’ ethics. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(2), 202–220.

- Lyles, W., White, S. S., & Lavelle, B. D. (2017). The prospect of compassionate planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(3), 247–266.

- Majoor, S. J. (2018). Coping with ambiguity: An urban megaproject ethnography. Progress in Planning, 120, 1–28.

- Mayo, J. M. (1982). Sources of job dissatisfaction ideals versus realities in planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48(4), 481–495.

- Olesen, K. (2014). The neoliberalisation of strategic spatial planning. Planning Theory, 13(3), 288–303.

- Osborne, N., & Grant-Smith, D. (2015). Supporting mindful planners in a mindless system: Limitations to the emotional turn in planning practice. Town Planning Review, 86(6), 677–698.

- Porter, L., Sandercock, L., Umemoto, K., Umemoto, K., Bates, L. K., Zapata, M. A., … Sletto, B. (2012). What’s love got to do with it? Illuminations on loving attachment in planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(4), 593–627.

- Puustinen, S., Mäntysalo, R., Hytönen, J., & Jarenko, K. (2017). The “deliberative bureaucrat”: Deliberative democracy and institutional trust in the jurisdiction of the Finnish planner. Planning Theory & Practice, 18(1), 71–88.

- Raworth, K. (2012). A safe and just space for humanity: Can we live within the doughnut. Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience, 8(1), 1–26.

- Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

- Rodriguez, A., & Brown, A. (2014). Cultural differences: A cross-cultural study of urban planners from Japan, Mexico, the US, Serbia-Montenegro, Russia, and South Korea. Public Organization Review, 14(1), 35–50.

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(6), 1161.

- Sager, T. (2009). Planners’ role: Torn between dialogical ideals and neo-liberal realities. European Planning Studies, 17(1), 65–84.

- Saija, L. (2014). Writing about engaged scholarship: Misunderstandings and the meaning of “quality” in action research publications. Planning Theory & Practice, 15(2), 187–201.

- Salet, W. (2018). Institutions in action. In W. Salet (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of institutions and planning in action (pp. 27–47). London: Routledge.

- Sartre, J. P. (1956). Being and nothingness. ( H. E. Barnes, Trans.). New York, NY: Philosophical Library.

- Sehested, K. (2009). Urban planners as network managers and metagovernors. Planning Theory & Practice, 10(2), 245–263.

- Sengupta, U., Rauws, W. S., & de Roo, G. (2016). Planning and complexity: Engaging with temporal dynamics, uncertainty and complex adaptive systems. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 43(6).

- Sturzaker, J., & Lord, A. (2017). Fear: An underexplored motivation for planners’ behaviour? Planning Practice & Research, 33(4), 1–13.

- Talvitie, A. (2009). Theoryless planning. Planning Theory, 8(2), 166–190.

- Tasan-Kok, T., Bertolini, L., Oliveira E Costa, S., Lothan, H., Carvalho, H., Desmet, M., … Ahmad, P. (2016). “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”: Giving voice to planning practitioners. Planning Theory & Practice, 17(4), 621–651.

- Thompson, R. (2000). Re-defining planning: The roles of theory and practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 1(1), 126–133.

- Udy, J. (1994). The planner: A comprehensive typology. Cities, 11(1), 25–34.

- Vogelij, J. (2015). Is planning theory really open for planning practice? Planning Theory & Practice, 16(1), 128–132.

- Watson, V. (2002). Do we learn from planning practice? The contribution of the practice movement to planning theory. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 22(2), 178–187.

- Westin, S. (2011). Planning on the couch: Exploring Michael Balint’s concepts of ocnophilia and philobatism. Presented in Annual Conference of the Association of American Geographers 2011, Seattle, USA.

- Westin, S. (2016). The paradoxes of planning: A psycho-analytical perspective. London: Routledge.

- Zanotto, J. M. (2019). Detachment in planning practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 20(1), 37–52.

- Žižek, S. (1997). The Abyss of freedom. Ann Arbour, MI: The University of Michigan Press.