ABSTRACT

The paper provides an empirical review of a widely used tool in the English planning system – pre-application discussions (‘pre-apps’) and a theoretical exposition of governmental ‘logics’ that underpin neoliberal-informed planning reforms. We present five logic frames of growth, efficiency, commercialisation, participation and quality, and apply these to pre-application negotiation practice, to highlight how Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) are faced with the challenge of reconciling a complex of multiple and often competing aims that appear irreconcilable in practice. We highlight that whilst ‘ordinary’ planning tools such as pre-apps may appear mundane, they can provide valuable instantiations where logics collide.

Introduction

The planning system in England is again going through a period of reform. The latest set of reforms presented in 2020 has proposed a shift away from the ‘discretionary’ case-by-case approach to planning decisions based on technical (planning policy and development management officers) and political (elected member and planning committee) judgements on the national and local policy framework that is unique to the UK and Ireland, towards a ‘codified’ consenting route (zoning) seen in a variety of specific forms across planning systems internationally (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG], Citation2020). However, whether or not such changes come to pass, either through this current reform agenda (and emerging Planning Act) or any future reformulation of the English planning system, is not the focus of this paper. Rather than detail any particular package of reforms contemplated and/or enacted in England, we seek to draw attention to the wider ideological and political ‘logics’ underpinning myriad planning reform agendas as set within neoliberalised political economies. In particular we highlight how political rationalisations derived from neoliberal ideology seek to steer the aims and objectives of the system and have purchase in the discursive interactions of planning practice (i.e. how logics are reflected in local practices and where/how they are reconciled by key stakeholders). We do this by drawing on the empirical case of a ubiquitous but under-researched planning tool in the English system – pre-application discussions (‘pre-apps’) – to highlight how broad reform aims are embedded (and contested) in local practice. We mobilise the case of pre-apps here because, whilst they appear at surface-level to be a routine or mundane informal part of the English planning system, we argue that they are a container or bounded space where exchanges take place over competing logics that can expose system biases (cf. Coaffee & Healey, Citation2003) and help discern how the logics are navigated by the local planning authority (LPA) and applicant/developer. In other words, rather than being seen as neutral discussions (i.e. as a process of ‘sense-checking’) they can shut down, re-open or fix key issues at the very earliest stages of a development scheme, and this negotiation and bargaining takes place before proposals are subject to wider (public) scrutiny and may foster a sense of opaque, fuzzy decision-making in the system while also trading elements of public policy goals.

Whilst we focus on ‘pre-apps’ as a specific tool used within the English planning system, these types of informal discussions about development between planning authorities and developers have parallels internationally, with many forms of pre-apps found across national planning systems (Parker & Arita, Citation2019; Reimer et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, such spaces have been regarded as part of a growing set of ‘soft’ and ‘fuzzy’ planning arrangements which act to supplement, if not replace, formalised regulatory planning structures and institutions (Haughton et al., Citation2009; Healey, Citation2013); with key decisions increasingly being negotiated and agreed by informal bodies/spaces within the system but outside of formal regulatory oversight.

We see logics, and the associated concept of planning rationality, as an operationalised form of ideology and power mobilised to achieve certain ends, and particularly to convince or coerce others of the merit and necessity of such ends – with the vehicle here being planning reform. Planning rationality has been widely discussed and set out in a particular sense to express the thinking underpinning planning practice (Alexander, Citation2000; Verma, Citation1996), based around the generalised definitions of “making decisions based on clear thought and reason” (Cambridge Dictionary, Citation2021). While abstract definitions suggest a level of objectivity or neutrality, the literature has shown that these are far from ‘value neutral’ and are instead shaped by power and ideology (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998; Rivero et al., Citation2017; Watson, Citation2013). The concept of political rationality is defined as ways of thinking about the nature and practice of government (Foucault, Citation1991) which is based on a particular reasoning. Political rationalities are associated with technologies of government, which are the techniques used to shape conduct, needs and desires with a particular set of goals in mind (Dean, Citation1999). Similarly ‘logic’ may be defined in general terms as ‘a particular way of thinking, especially one that is reasonable and based on good judgment’ or as ‘sensible methods of thinking and making good decisions’ (Cambridge Dictionary, Citation2021). In this way we see logics as closely related to ‘rationality’, which ostensibly appear (or are presented) as ‘common-sense’ thinking, but are entwined and infused with a political rationality that seeks particular ends (and that can complement or conflict with each other).

Given the above, we deploy the term logics here as a shorthand for the singular elements or base components discernible in a particular governance agenda; that form the building blocks used to construct broader (more or less stable) political rationalities for reform. These are effected through the deployment of different packages or bundles of ideas and ‘tests’ that successive governments impose to orient and judge planning systems. We deliberately retain the use of logics to highlight the ideational strands that are present and combined as part of the broader political rationality pursued for driving system (re)design, policy and a modality whereby planning is both a tool and producer of politics. That is how various logics are calculatingly weaved together within techno-political rationalities to present a set of reforms or specific planning policy or tool(s) that shape the realrationalitat of practice (Yiftachel, Citation1998).

Within this nested (‘Russian Doll’) conceptualisation of governmental reform, ‘ideology’ sits at the apex, shaping the operationalised rationalities and logics, and serving as a political frame for the set of beliefs or principles being pursued, but which are inherently unstable in practice (Shepherd, Citation2020). Ideology forms the overarching aims but requires ‘power’ as the means to pursue those aims through ‘the ability or right to control people and events, or to influence the way people act or think in important ways’ (Cambridge Dictionary, Citation2021). While it is beyond the scope and purpose of this paper to present a wider exposition of rationality, power and ideology here – and this has already been well-developed in the literature (see e.g. Allen, Citation2003; Dean, Citation1999; Flyvbjerg, Citation1996, Citation1998; Foucault, Citation1991; Lukes, Citation1974), such ideas are important for understanding how development decisions are made on a day-to-day basis through discussion and negotiation with other stakeholders to reach agreement(s) on issues. Such interactions may be genuinely ‘collaborative’ (Healey, Citation2003), but can also form the spaces/tools of post-political choreographed ‘consensus’ (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2012).

As we outline, pre-apps form an important bargaining space that sits within the interstices of the planning system and where various logics (kept deliberately and explicitly separate from any overriding or composite idea of rationality), shaped by ideological aims and power relations, take on a ‘material form’ in practice (Allmendinger et al., Citation2016; Inch, Citation2018).

Local authority funding and commercialisation in planning are also important contextual factors that shape the ‘actually-existing’ bargaining/negotiation practices that take place within pre-application discussions. Local Authorities in England have experienced significant public funding cuts as part of the austerity drive between 2010–2015 and which have not been subsequently reversed. As such they have had to develop alternative means to produce revenue and act more commercially in order to secure their own financial self-sufficiency (Dobson, Citation2019; Slade et al., Citation2021). During this same period there has been a significant upswing in the role of the private sector in planning and a greater emphasis on development viability and deliverability in national policy. Such trends have served to shift the balance of skills, knowledge and power between public and private sector planning actors (Parker et al., Citation2019). These have heightened interest in pre-apps as a means to generate income for LPAs on the one hand and ensure the commercial viability of larger schemes on the other – the latter has become a dominant consideration for planners both in the UK and beyond (Ferm & Raco, Citation2020; Waldron, Citation2019), a context within which the former can all too easily become ancillary to the servicing of viability.

In this paper we present five logic frames; growth, efficiency, commercialisation, participation and quality and apply these to pre-application negotiations. We do this to draw attention to how LPAs and public sector planners are faced with the challenge of reconciling a complex of multiple and often competing logics in practice. We also highlight these because, within an increasingly financialised property market and commercialised public sector planning context, certain logics may be privileged over others. Whilst this prioritisation is not necessarily an issue in itself, it does raise questions around how other logics are viewed and promoted/defended, or displaced in informal (soft/fuzzy) discussion spaces; and, significantly, when they may not carry the same weight as measures that, for example, prioritise speed, certainty and costs to developers over other planning goals that do not fit neatly with neoliberalist policy agendas.

Planning Reform and Governmental Logics

Planning reforms in England have been oriented towards supporting neoliberal pro-growth policy agendas for a considerable time, and such a trajectory has been a common feature across many planning systems internationally (cf. Gunder, Citation2010; Sager, Citation2011). Whilst the generalities and specifics of planning systems across national borders are quite different, the trends towards market and business-oriented solutions, and the increasing role of investment finance in society are now widespread. For such states informed by neoliberal ideology, their land-use planning system (whatever its specific structure and operation) becomes one key policy enactment field in which particular governmental ends can be achieved (e.g. growth).

The intention here is not to rehearse the already well-developed and extensive literature on neoliberalism and planning (e.g. Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2013; Tasan-Kok & Baeten, Citation2011), but Lord and Tewdwr-Jones (Citation2014, p. 346) summarise the various broad aspects of neo-liberal planning forms in the literature as involving:

greater marketization of planning, a more prominent role for the private sector in determining policy, the replacement of local discretion in favour of an agenda created by a central government–business nexus and the deregulation of state planning with the removal of higher strategic levels of planning.

More recently the academic literature has been alive to changes that exhibit these characteristics, particularly given the increasingly critical links between development and investment finance as the product of such regulatory (planning) activity. As such, there has been recent interest focusing on related but distinct terms, such as the commercialisation, financialisation and monetarisation of planning services and development activity – which are seen as being in service of a set of wider neoliberal goals in different policy and practice contexts (Bradley, Citation2021; Savini & Aalbers, Citation2016).

Added to this milieu, the rolling planning reforms since the 1980s have featured a shift from traditional administrative models of public services to formulations of New Public Management (NPM) practice. Pollitt and Bouckaert (Citation2017, p. 6) highlight that through the NPM agenda “there arose a fast-spreading desire to make government more business-like – to save money, increase efficiency, and simultaneously oblige public bureaucracies to act more responsively towards their citizen-users”. Similarly Clifford (Citation2016, p. 384), focussing on local planning, specifically saw NPM as a highly normative corporate archetype of public sector organisation, distinct from previous traditional public administration models; whereby the emphasis on ‘efficiency’ became “the sine non qua of public services”. This shift in operational environment involves a composite set of objectives and reforms that “clearly has wide-ranging implications, not just for the citizen-consumers of public services, but also for the professionals providing these services” (Clifford, Citation2016, p. 384).

These drivers are also implicated in attempts to change the ‘culture’ of planning, to align actors towards governmental agendas and to adopt more efficient practices (Shaw & Lord, Citation2007). In the UK, the national government have sought to reorient the culture of local planning for at least the past two decades, stating as far back as 2002 an aim levelled at “a culture which promotes planning as a positive tool: a culture which grasps the opportunities to improve the experience of planning for those affected by its decisions whether businesses, community groups, individual members of the community or planning professionals” (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister [ODPM], Citation2002, p. 2).

Neoliberal policy contexts emphasise reductions in state and public spending that has driven ‘commercialised’ orientations in local government. One example of this culture change is the Local Government Association (LGA) guidance for councils to be more ‘enterprising’, stating “establishing a commercially focused culture is imperative for the successful commercialisation of services … [but] for some parts of the organisation it could present a real challenge from a skills, capability and cultural point of view” (Local Government Association, Citation2017, p. 17). The Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI) highlight that “reductions in budgets have forced local planning authorities to focus on development management and income generation … public planning is increasingly reliant on income from development management, which now accounts for about half of all spending on planning” (RTPI, Citation2019, p. 3). Jones and Comfort (Citation2019, p. 2) also note “key attributes might be seen to include the quality and speed of decision making; customer focus and creativity; the ability and freedom to attract and retain top talent; and the ability to invest for the longer term”.

Within this context, we focus on the underpinning logics and how they are translatable into practice at the local authority level through planners’ decision-making discretion on development proposals. This builds on the findings of Blanco et al. (Citation2014, p. 3129) that calls for “the study of local practices, in ways that recognise the multiple logics at play in different conjunctures, and the spaces such ambiguities and ‘messiness’ open up for different forms of situated agency”. For them, the local state acts as the container of ‘the logic of the local’ but this issue remains largely divorced from broader accounts of neoliberal urban governance practices. Rose et al. (Citation2006) discern the “need to investigate the role of the grey sciences, the minor professions, the accountants and insurers, the managers and psychologists, in the mundane business of governing everyday economic and social life, in the shaping of governable domains and governable persons, in the new forms of power, authority, and subjectivity being formed within these mundane practices” (Rose et al., Citation2006, p. 101), and as a means to answer the questions “Who governs what? According to what logics? With what techniques? Towards what ends?” (ibid: p85). Inch (Citation2018, p. 1080) also argues that, because dominant conceptions of state modernisation in the UK have been strongly shaped by neoliberal logics, it has become “crucial to develop modes of analysis that can trace the complex ways in which such logics are stitched together as part of processes of state restructuring”.

A deeper focus on and fine-grained analysis of the mixture of component logics present within different planning tools and spaces may also assist in addressing emerging critiques that neoliberalism has become “a deeply problematic and incoherent term that has multiple and contradictory meanings, and thus has diminished analytical value” (Venugopal, Citation2015, p. 165).

This leads us to consideration of the specific mix of logics sitting behind repeated attempts at planning reforms. Healey (Citation2006, Citation2013), Harris and Thomas (Citation2011) and Watson (Citation2003) identify how planning can be a site for conflicting or competing logics. Furthermore, when assessing fields where more than one logic is present, Reay and Hinings (Citation2009) showed how a logic of efficiency can be combined with others in practice (e.g. professionalism) – although they stress that this is unusual and is unlikely to be maintained indefinitely where there are competing logics. Instead, one logic is likely to dominate where authoritative power adopts and pursues one as an overarching or organising ‘prime’ logic around which other logics must eventually align or be subordinated in some way – as we highlight later through the practice of pre-apps.

The literature on neoliberalised forms of planning reforms and NPM help to identify persistent governmental logics which have been driving reform and have shaped practice both in the UK and internationally. A concern to enable and deliver economic growth and associated physical development as the primary goal of the planning system is the first and the prime organising logic. Second is an efficiency imperative, concerned with speed and other costs of the system, including brokering certainty. Third is public sector financial autonomy and increased self-sufficiency through various forms of innovation and income generation as part of commercialisation. Fourth is a rhetoric signified by a concern to engender democratic participation, which has been discernible most obviously through the localism agenda (Wargent, Citation2021). We add to these a fifth logic concerned with quality of outcome (with ‘policy compliance’ as a cipher for quality) and arising as a concern to aid (and possibly justify) the prioritisation of the first three logics (e.g. Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission, Citation2020).

We contend that each of these governmental logics has a different ‘audience’ in mind and are ‘discursive containers’ (or rhetorical bundles) for a wide range of ideas and assumptions aimed at driving a range of behaviours as expressed below:

Growth = e.g. development (esp. house building), employment, infrastructure.

Efficiency = e.g. speed, certainty, deregulation, mitigated risk/costs, performance.

Commercialisation = e.g. markets, private sector mentality, business-like, culture change, entrepreneurial, customer and service focussed, profit making.

Participation = e.g. consultation, engagement, transparency, democracy.

Quality = e.g. of outcome, value, policy compliance, improvements, public interest, design standards, sustainability, professionalism.

We deploy the terms Growth, Efficiency, Commercialisation, Participation and Quality as shorthand to label the logics. These terms are likely to evoke different meanings from the varied audiences of reforms – indeed these logics are directed to and received variously by different planning audiences – and combinations of the logics and their import serve particular interests or are likely to militate against the interests of other audiences. shows this indicatively by highlighting the anticipated primary and secondary prioritisation of, or alignment with, the logics and their receiving audiences.

Table 1. Key planning interests as ‘audiences’ and the driving logics

These logics can be mapped onto the government objectives for reform agendas. For example, the previous Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government announced their own set of pledges to reform planning post-2010 (see Conservative Party, Citation2010). DCLG (now DLUHC), as the UK government department overseeing planning, were set six objectives for reform:

lift the burden of bureaucracy [i.e. Efficiency logic]

empower communities [i.e. participation logic]

increase local control of public finance [i.e. commercialisation logic]

diversify the supply of public services [i.e. commercialisation logic]

open up government to public scrutiny [i.e. participation logic]

strengthen accountability to local people [i.e. participation logic]

(DCLG/MHCLG, Citation2011, p. 16 – our emphasis)

Here we can see that a number of different logics were presented as one coherent reform package that underplayed the potential competition and trade-offs between achieving such varied goals. The logics may also be distinguished as ‘instrumental’ and ‘value’ rationalities. The instrumental rationalities of speed, delivery and commerciality are seen to jostle with other considerations that shape value rationalities centring around questions of democracy and/or the substantive ends of planning (e.g. public interest, wellbeing, design and sustainability). This highlights how such national policy and reform agendas can be maintained at the abstract ideological level up until they have to be made concrete at the local practice level, where the (deliberately or otherwise) masked/hidden tensions emerge and trade-offs have to be made.

The extent to which certain logics are prioritised and how they directly or indirectly affect interest(s) will vary across contexts, stakeholders and schemes; but they act to shape LPA approaches regarding how they plan, who with, and on what basis. This policy world view is percolated down to the actual working practices of planners who are obliged to attempt to navigate such a mix of reform logics within local ‘landscapes of antagonism’ specific to their geographical, political, economic, social and institutional contexts (Newman, Citation2014). For Newman (Citation2014, pp. 3294–95) “[l]ocal governments play an active role in strategies for governing populations by installing ‘economic’ logics of calculation (constituted through discourses of markets, efficiency, responsibility, consumer choice and individual autonomy) and strategies for promoting ‘self-governing’ subjects’; and warning that the ‘temptation is to see local authorities as the passive victims of global and national forces … [that] may, through their own policy agendas, be crucial actors in producing, reproducing, reworking and reconstituting neoliberalism”. The local state and public planners are the facilitators/agents of government reforms, and how they respond individually to the (mixed) logics at the local level determines their success. A focus on national logics and local compliance can also assist understandings of ‘structure-agency’ theory in the planning and development process (Healey & Barrett, Citation1990).

Therefore, we contend that planning logics are an important theoretical construct here because they help to explain connections that create a sense of common purpose and which orient decisions about what is (and is not) done and how to act. These act in a crosscutting way across structures, processes, cultures and behaviours. The logics that are acted upon form the basis of more or less taken-for-granted rules and tests guiding the practices of actors and that become constitutive of “ … the belief systems and related practices that predominate in an organizational field” (Scott, Citation2001, p. 139). A single logic or bundle of logics require a carrying culture: both operationally and in terms of policy orientation, and underpin institutional arrangements that also help explain actual decision-making and reflect different ways of seeing the world.

highlights the multiple logics, spaces and audiences for a range of planning tools, emphasising the more complex nature of competing rationales behind local planning practices and decision-making. Again, whilst the terminology and policy/regulations behind each of these tools are specific to the English planning system, such planning tools and features are found across planning systems internationally and carry relevance to the specific terms and tools used within other systems (e.g. all have some form of local authority and community plan-making, planning contributions, permitted development and financial viability considerations).

Table 2. Planning tools, logics and audiences in the English planning system

We contend that these logics (although present in different specified forms and extents) are driving reform policies, practices and tools in other neoliberalised planning systems, and therefore have relevance to researchers, policy-makers and practitioners working in contexts beyond England. Furthermore, whilst we focus here on pre-apps, demonstrates that this framework for logics can be applied to a range of different planning tools and audiences.

Pre-Apps in the English Planning System

At their most basic, pre-apps typically involve developers discussing the relative merits of a development proposal before investing time and resources in formal or finalised plans for a planning application. Pre-apps are an unregulated and discretionary part of planning that sit outside of formal statutory processes – forming an element of what has come to be labelled ‘fuzzy’ or ‘soft’ planning spaces – albeit at the local scale and applied in development management rather than in policy-making or institutional arrangements (Haughton et al., Citation2009). Whilst pre-app consultation has been made mandatory for some particular types of development (e.g. shale gas development, wind turbines), our focus is on the non-mandatory mainstream use of pre-apps, which includes large development schemes. Pre-apps are also ubiquitous with almost every local authority in England, making use of them to discuss emerging development proposals. Furthermore their use has recently expanded, and different types and scales of emerging developments are routinely discussed. Despite this, there is little work on the history and specific advice on the practice of pre-apps, but what is available is largely presented in our review (see also Local Government Association [LGA], Citation2014; Parker & Arita, Citation2019;; Dobson et al., Citation2020).

Whilst austerity has been a key driver for the commercialised use of pre-apps post-2010, government policy had already been urging its use for some time (then via appeals to the efficiency and to a lesser extent participation logics). The Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG, now DLUHC) under the previous New Labour government produced a consultation document entitled Development Management: Proactive Planning from Pre-application to Delivery in 2009, stating that “Government should strengthen and clarify national policy and guidance, so as to set out clearly its key expectations from applicants, statutory consultees and local planning authorities in the pre application process”, based on a number of claimed benefits as outlined below (DCLG, Citation2009, p. 4):

Early notice of investment proposal.

Ensuring applicants understand the range of considerations against which a planning application would be considered.

Allowing all parties to gain a better understanding of any constraints or opportunities, background and history of the site.

Helping to avoid applicant costs.

Establishing what the information requirements will be for any particular application.

Establishing a better understanding of timescales and administrative processes.

Early engagement to reduce or prevent delays at the determination stage.

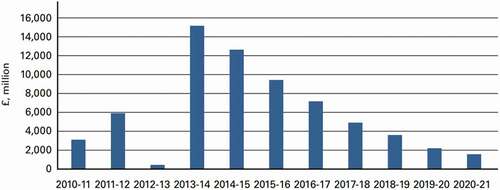

Prior to this, the 2003 Local Government Act had allowed LPAs to charge for ‘discretionary services’ and this included pre-apps, while subsequent guidance indicated that charges for pre-apps should be proportionate to the type and scale of development. These set the necessary foundations but not the necessary conditions for the widespread adoption of pre-apps by local authorities; this came later in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and election of the Coalition government in 2010. The result of the austerity measures imposed was a 49.1% real-terms reduction in government funding for local authorities between FY2010-11 and 2017–18, which equates to a 28.6% real terms reduction in ‘spending power’ (government funding and council tax; NOA, Citation2020). Annually, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG, now DLUHC) produces The Local Government Finance Report (England) to outline the government’s financial settlement for local authorities for the year. highlights the reduction in Revenue Support Grant (RSG) provided to English local authorities between 2010/11 and 2020/21 and before the removal of the RSG for 168 local authorities in 2020.

Figure 1. Central government funding for LPAs via Revenue Support Grant (2010–2019)

It is sobering to note that since the economic recovery from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in the UK, the RSG has decreased from £15.2 billion in 2013/14 to just over £1.6 billion in 2020/21 – a reduction just shy of £14billion in seven years. This sets into context the local authority imperative to raise additional revenues to supplement their remaining core income from council tax and business rates; particularly given that local authorities have a legal duty to set a balanced budget and avoid a ‘Section 114ʹ (i.e. a sanction applied in response to illegal overspend by local authorities under the Local Government Finance Act 1988). It is in this context that discretionary service provision has increasingly commanded fees as a relatively easy way for LPAs to commercialise in response to national reforms to funding and policy.

Central government provide some general guidance indicating how they see charging for pre-applications advice by LPAs:

“where local planning authorities opt to charge for certain pre-application services, they are strongly encouraged to provide clear information online about: the scale of charges for pre-application services applicable to different types of application … [and] the level of service that will be provided for the charge, including:

the scope of work and what is included (e.g. duration and number of meetings or site visits);

the amount of officer time to be provided (recognising that some proposed development requires input from officers across the local authority; or from other statutory and non-statutory bodies);

the outputs that can be expected (e.g. a letter or report) and firm response times for arranging meetings and providing these outputs”.

(NPG, Citation2019b: Paragraph: 004 Reference ID: 20–004-20180222)

Yet despite the growing use and commercialisation of pre-app services in practice, such services are loosely managed through broad and suggestive national policy and practical guidance. Recent exhortations to use pre-apps have been expressed in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), but clear guidelines, regulations, procedures or terms of engagement for the process are absent. The National Planning Guidance (NPG) outlines that:

“Pre-application engagement by prospective applicants offers significant potential to improve both the efficiency and effectiveness of the planning application system and improve the quality of planning applications and their likelihood of success. This can be achieved by:

providing an understanding of the relevant planning policies and other material considerations associated with a proposed development;

working collaboratively and openly with interested parties at an early stage to identify, understand and seek to resolve issues associated with a proposed development, including, where relevant, the need to deliver improvements in infrastructure and affordable housing;

discussing the possible mitigation of the impact of a proposed development, including any planning conditions;

identifying the information required to accompany a formal planning application, thus reducing the likelihood of delays at the validation stage”.

(NPG, Citation2019b: Para 001 Ref ID: 20-001-20190315 – our emphasis)

The online Planning Practice Guidance (PPG) also simply states: “Pre-application engagement is a collaborative process between a prospective applicant and other parties which may include: the local planning authority; statutory and non-statutory consultees; elected members; local people. It is recognised that the parties involved at the pre-application stage will vary on a case by case basis, and the level of engagement needs to be proportionate to the nature and scale of a proposed development. Each party involved has an important role to play in ensuring the efficiency and effectiveness of pre-application engagement” (NPG, Citation2019a, NPG Para: 003, Ref. ID: 20–003-20140306).

This envisages a wide range of situations and spaces that could conceivably be considered as part of a ‘pre-app’ stage – with some resulting definitional confusion over ‘pre-apps’ which are actually developer-led consultations with communities over emerging schemes. Loose policing and diversity of practices tends to obscure whether LPAs are serving a national policy agenda for inclusion and transparency in the pre-app discussions that they host. This is particularly acute given the tension between a drive to encourage engagement and localism and the push to deliver a customer satisfaction priority. Whether or not any improprieties exist is unknown; the point is rather that neither government, nor the public, nor professional bodies nor researchers really know what is being discussed, with whom and at what cost (and income) within this widespread practice. It is not clear what level of scrutiny, if any, pre-app negotiations are subject to at the local level, and this leads to questions over their transparency and accountability, not least when the applicant/developer is now paying for a service from the public sector and altering the role of the public sector planner. This raises issues around what is expected by the applicant as a client within a more business-oriented local authority practice culture and also begs questions about how pre-app revenues are used by councils. We do not contend that corruption is a feature within the English planning system, but such situations are unlikely to develop trust relations between local government and the public (Grosvenor, Citation2019).

Methods

The research involved a two-stage mixed-methods approach. The first stage involved a desk-based review of available information about pre-apps on LPA websites and a national benchmarking survey that obtained data from 114 of the 318 LPAs in England (with all being invited to complete the survey). Of the 114 LPA survey responses from across England, 70 provided complete pre-app income/expenditure data. The second stage then identified 12 case study LPAs to explore how pre-apps were being used in practice through semi-structured interviews with planners experienced in undertaking pre-app discussions. The cases were drawn from these 70 LPAs and using the below selection criteria to ensure a range of practices and their contexts was captured in the primary data:

Pressure to commercialise found in the survey

Claimed commitment for involvement of communities

Geographical spread across England

Local Plan status

Relative growth pressures and market context

This approach served to underscore the potential conflict between competing objectives within the English planning system as experienced by planners. It is evident that geography, local plan status and relative growth pressures are relevant to how LPAs develop and deliver on their commercial strategies, commitment to enhance participation and promote transparency.

The respondents were anonymised to ensure open accounts about experiences of pre-apps. We specifically targeted the level between Heads of Planning/Development Management and Senior Directors with the portfolio for planning services to elicit knowledge of both the high-level discussions around corporate strategy and budget/revenue objectives within the local authority, but also an understanding of planning activity ‘on the ground’. Commercialisation is a key factor for understanding pre-apps, but so are efficiency, public participation and quality; and interviewees who spanned these issues were targeted. The case study interview data was analysed using open and focussed coding to develop key themes with an emphasis on the aims (logics) shaping pre-app practices. There are also two caveats to be highlighted here. Firstly, whilst there is a diverse range of practices across England, the focus of this paper is not to provide a geographical analysis of pre-apps, but rather to outline the types of practices and highlight the associated driving logics. Secondly, we only present the views of professional planners and local authorities in our empirical data, and the views of developers/agents and local communities on pre-apps and consultations should form part of a wider research agenda.

Findings and Analysis

The logics of growth, efficiency, commercialisation, participation, plus the concern for quality, were clearly expressed within the empirical survey and interview data elicited. Whilst these logics overlap in practice, we review each in turn below to structure our findings and analysis.

Logic 1: Growth

Growth is the overarching government logic for the planning system in England as expressed through the NPPF ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’ and emphasis on ‘viability’. It is the prime logic into which all others align or are subordinated, with efficiency and commercialisation drives broadly supporting such ends and participation and quality potentially acting as hindrances. Local authority leadership mirrored this prime logic through recourse to planning for growth, with the key metric being housebuilding as a driver for economic development; the “expectations of the planning service are related to the ambitious growth programme … The expectation from senior management is to focus on homebuilding” (CS2). ‘Planning risk’ is often presented as stifling much needed economic growth through slowing down and imposing conditions on development – and from this perspective pre-apps can be seen to add confidence to developers/proposals through early interaction with local planners.

The concern is that when growth is prioritised, issues over quality and participation are often overlooked in terms of questioning what type of growth and development is taking place and for whom, especially where planning conditions/contributions are being informally negotiated.

Logic 2: Efficiency

Efficiency in planning is most commonly measured by central government in terms of speed of decision-making on planning applications, and as a main way of measuring planning ‘performance’. It is also concerned with costs in the round (i.e. financial, time, human) and deregulation as in the removal of ‘red tape’, often contrasting an inefficient bureaucratic public sector with the dynamic/innovative private sector. Pre-apps sit uneasily with deregulation as they add another stage to the planning process, which would explain government resistance to making it a formalised part of the planning system. This is overcome by assumptions that ‘front-loading’ planning discussions with the LPA and consultation with the community will remove political and public risk further down the line when such disruptions are more costly/harmful to a development scheme and thereby provide greater development certainty.

From the internal LPA perspective, ‘efficiency’ was discussed by planners primarily in terms of a ‘customer satisfaction priority’ and ‘cost recovery of the service’, along with a secondary concern for managing staff/case workload; as one planner explained “by investing time in pre-apps we incur less cost and are less likely to have repeat applications”. Externally to the LPA, certainty was acknowledged as the ‘number one priority’ for developers/agents to provide ‘confidence’ over a site or scheme gaining permission. The data highlights that Local Plan compliance, design requirements and access/transport are the main issues typically covered within a pre-apps, along with references to flooding/drainage and heritage/conservation. The efficiency logic here seeks to solve these issues early on through pre-apps, whilst trying not to place additional burden on developers. A concern for speed was also expressed through the need for ‘timely’ and ‘swift’ responses that can ‘advise enquirers about relevant information’ and ‘speed up [the] registration process’. In terms of speed, we found that there tends to be no set time limit for a single session of advice, and the different approaches vary across LPAs. Minor householder discussions tend to last up to an hour with major residential and commercial sessions requiring more time. The ‘suite’ of negotiations tends to last for one to three months for major residential and commercial pre-app discussions, whereas the overall time taken for minor development can be less than a day or up to four weeks depending on the issues.

Interestingly here internal LPA/Planner and external Government/Developer concerns for the inter alia provision of speed, certainty and costs jostle when determining ‘efficiency’ in practice – demonstrating the nuances and tensions within individual logics as well as between them.

Logic 3: Commercialisation

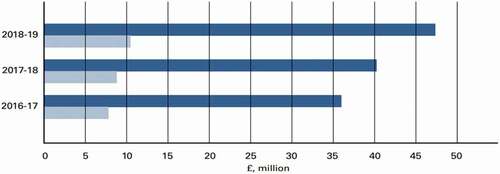

While it has been presumed that the income from pre-apps is an increasingly important source of revenue for LPAs under austerity, we did not know how much revenue pre-apps were bringing into planning departments and what percentage they made up of overall development management revenue. Our work shows that the fee income from pre-application advice over the past three years averaged well over £40million per annum. We extrapolated from our sample to provide an overall average income figure of around £47million in 2018–19. shows that LPAs are increasing their share of income through pre-apps as a revenue source.

Figure 2. English local planning authority pre-app income (reported and estimated)

These figures are significant and account for a substantial and growing tranche of overall planning service income. While this demonstrates how significant the income from pre-apps can be for LPAs in England, and for funding the planning system, we do not know how this money is used to support the planning department, given the increasing need for cross-subsidy within planning services to support areas that are not easily commercialised – such as policy-making. This income may be used by planning authorities to fund a pre-app officer or extra development management capacity, or may be directed back into the overall council budget.

The commercial and efficiency logics played a key role in thinking about how pre-apps should be delivered at the local level. In all cases these planners stated pre-apps had become “increasingly important … [due to] the lack of cost recovery from statutory planning application fees” and crucially as “one area where we can demonstrate added value to the authority”. The claimed benefits of a commercial approach were viewed as positive adoption of different ways of working and increased morale due to a private sector mentality, with CS5 stating their team like “the buzz of making money [and] being commercially minded”. Others were quick to point out that commercialisation was a “double-edged sword because of the pressure to deliver” but also an “opportunity” (CS11) with planning services now “big business” (CS2). Although CS8 was keen to point out that pre-apps should be about cost recovery and not “making profit” arguing income generating was not the important thing but rather the quality of the service: “The money itself is not important, [the] Chief Executive will not agree – but my view is the quality of service is most important”. This highlights the potential conflict planners face between the commercialisation logic (emphasised by the Chief Executive priority for income and financial self-sufficiency) and the professional prioritisation of the quality logic. CS7 expressed initial unease about the introduction of pre-apps fees but stated there was no reduction in service use which validated “an expectation out there now that fees should be [charged]”. CS1 similarly reflected “I felt that I am a public servant working in local government and at the time felt that was something we shouldn’t charge for, but over the years I realised its benefits. Now I am more of the view that I know we offer a very good service and if a developer were to contract a planning consultant they would be charged considerably more”. One planner even argued supporting development was so important and different to previous approaches that:

Not all planners are suitable to give pre-app service … [we] need someone to do it as fast as possible … Ideally it is someone who understands the pressures of developers and the need for commercial development and understand the industry. Most planners don’t have the mind for working that way … someone who works and empathises with them [developers/applicants]. (CS2)

This highlights the ‘culture change’ element as planners have had to reorientate their views to rationalise the need to develop a more commercialised planning service – and the resultant change to their practices represents a (re)prioritisation of logics to align with reform agendas.

Logic 4: Participation

Public engagement is usually undertaken by the ‘client’ (applicant/developer) in addition to pre-application discussions with local authorities. Although for some it is a more formal requirement of the process, such as part of an LPA’s Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) or the establishment of LPA-Developer forums or other innovative spaces for deliberation (Parker et al., Citation2021a, Parker, et al., Citation2021b). Such forums were viewed by planners as being ‘valuable’ where “frank discussions can be held with developers on a confidential basis”. Many LPAs did not advertise pre-apps to the public or elected members, instead highlighting that developers wanted some level of confidentiality. Around a third of respondents did not make any records of pre-app discussions of any type, whereas two thirds kept pre-app minutes, with only some then being made public. Some LPAs stored minutes: “sensitively in the document management system” that were “not for public viewing”; whereas others stated written responses are “published at point of submission of the planning application”. Generally, LPAs would not disclose any information about a live pre-app, with the matter considered confidential due to possible commercial sensitivity of market data (and linked to related development ‘viability’ narratives). This was often at the request of the developer who could specifically state they wanted to be Freedom of Information request (FoI) exempt. The majority stated that their pre-apps are confidential being “totally in confidence” (CS8) and “completely sensitive” (CS9).

Whilst it was acknowledged that there is political pressure from members and communities to be more transparent about what is discussed with developers and kept confidential until the planning application stage, the respondents expressed mixed views over their role in pre-apps. One argued that “Pre-application proposals are speculative, may never lead to a planning application, and spread rumour and mistrust among the local community. Community involvement in pre-application would reduce the amount of advice sought and is all round a seriously bad idea”. Similarly, CS7 was concerned about such inputs where local communities “may be totally ignorant about developments on their doorstep”. In contrast CS9 was critical of the lack of participation in pre-apps, arguing that “by not involving the local people – how do we know we are doing it right? Sitting in an ivory tower thinking we have got it right”. CS12 also noted that where communities are not involved “there is an acceptance that it [development] is a done deal or stitch-up at pre-app”. These mixed accounts raise critical issues over the perceived value of community input and supporting development at such informal stages on the one hand, and building public transparency and trust on the other. This position is further complicated because “Developers want local planning authority certainty; they want to understand obligations, design etc. or anything that is controversial in that particular area. The problem for local planning authorities is how you give that certainty when you don’t know the views of the community. It’s hard at this time to make the difficult calls developers would want you to”. Here the confidentiality of the commercialisation logic, certainty of the efficiency logic and public consultation of the participation logic clash in practice – leaving LPAs and planners caught in the middle of competing planning aims and having to make trade-offs between them.

Planners rationalised this as “public interests need to be balanced with the private sector demands [so the] commercial partner sees the benefit in delivering the public interest”; where a key role of the case officer is balance and “impartiality”; for example, accepting that “housing-developers are making lots of money for shareholders but they are also delivering a public good” (CS10). Such reorientation of practices highlight tensions around the participation logic.

Logic 5: Quality

A fifth consideration that did not figure strongly in governmental rhetoric until recently is quality and outcomes. Some respondents observed that the pre-apps stage was quite commonly viewed as a ‘tick-box exercise’ for developers, with others stating that pre-app advice was often ignored after significant officer time had been spent providing advice. Furthermore, some commented that schemes are often too far advanced, even at pre-app stage, to be influenced. Some suggested that a requirement for “applicants to adhere to the advice provided” could be introduced, or that “greater powers to refuse schemes and backing from PINS at appeal” could be provided if pre-apps were ignored. Another argued that “Developers do not recognise the benefits. Householders tend to consider it a waste of money as their agents tell them to just apply for permission and try to negotiate. Larger schemes benefit from pre-app, but not when the landowner/promoter attends meetings with the opinion that the local planning authority is a barrier. Sometimes they forget this is a positive discussion to help improve their developments [and] not just beat obstacles”. Particularly as pre-apps can “add value to development and reduce time required to deal with applications”. Although for smaller householder enquiries, one respondent felt that there was a need for ‘more flexibility’ for those who “just need advice or guidance without forcing them into a formal pre-application … but I sometimes feel there is a pressure or reliance on the fee income generation, which could be at the expense of offering simple or quick advice to those not versed in the planning system”.

This empirical findings section has used the example of pre-apps to highlight how LPAs and planners are attempting to square a number of complex, multiple and often competing planning reform aims (logics) that may not be reconcilable in practice. Rather than being a ‘win-win-win’ tool that can achieve a number of presumed ends, pre-apps highlight how the prime neoliberal logic for growth overshadows more traditional planning concerns for public participation and quality of development logics that form a key justification for public interest planning rationality.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper has sought to make two contributions to the planning literature. The first contribution is theoretical to highlight the potential of a logics framework for investigating and explaining how different planning practice tools are operationalised in service of government planning reform agendas. We contend that few have demonstrated how trade-offs are viewed by LPAs and planners within specific planning tools and stages, particularly where they operate within informal fuzzy/soft spaces, and that this approach can be applied to other planning systems. The second contribution is empirical given the lack of research on a ubiquitous planning tool that has become increasingly important and diversified in practice but continue to present unknowns about what is being negotiated and how competing reform claims are reconciled.

When focussing on pre-apps it becomes clearer to see how planners (and LPAs) are expected to achieve competing objectives simultaneously. A conceit is apparent in the actions of central government who at best wilfully misunderstand, or at worse simply ignore, the tensions within the competing logics that they promote through their reform agendas. They are presented to local government and other audiences as compatible and thus as a coherent (ideological and practical) approach. Instead our analysis is that unrealistic (and sometimes contradictory) expectations are being transmitted to the local scale and that these logics highlight government simplification of planning issues and goals that also act to drive continuous attempts at reform. As such, pre-apps provide a valuable case where all the logics collide in practice, and ongoing reforms indicate government frustration that local outcomes are not aligning with ideological assumptions about how planning should work to deliver on multiple objectives set nationally.

Our view is set within the general consensus that the principles of pre-apps in national policy appear sound, but become muddied when the original governmental logics for promoting pre-apps in the planning application process (\. based on the normative desire for more efficient, higher-quality and participatory outcomes), clash with LPA needs to operationalise pre-apps as a commercialised service to generate revenue and deliver on pro-growth reforms. Further research is needed to examine how such priorities are negotiated and/or overshadowed within informal bargaining spaces such as pre-apps. Yet it is clear that pre-apps can have a number of potential advantages for local authorities, developers and the wider community than as currently practiced – particularly if pre-apps become deliberative and include all key users.

We contend that informal negotiation spaces will remain, both in the UK and internationally, and merit much closer attention given that professional discretion cannot be completely removed from decision-making and that political rationalities will influence systems. If anything, such discretion and exemptions become more important within codified systems, where particular logics may have already been ‘baked into’ the system and become concealed through normalisation. Indeed, the UK government is still presenting multiple logics as compatible for further planning reform across speed, certainty, design, digital and engagement (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG], Citation2020). Once again the efficiency logic takes on a central role (through speed and certainty of development) and participation (through digital and engagement), with design now elevating the quality logic more explicitly. Our analysis has shown that reform attempts based on ideological premises alone ignore the trade-offs that LPAs and planners have to make for the different (competing) goals and across the audiences and interests that operate within them. Until governments accept the trade-offs that their reforms and political rationalities impose on planning systems, and for the specific policy tools that follow from them, these logics will continue to collide in practice with local government and public planners left to resolve (irreconcilable) tensions.

This work highlights two wider issues of import to planning scholars and practitioners. First is that the logics most closely aligned with neoliberal ideology such as growth, efficiency and commercialisation are promoted and incentivised and/or sanctioned through government policy and reform agendas that seek to promote and consolidate market and business interests within and through their land-use planning systems. Within such neoliberalised political economies, these logics will be prioritised over others despite expressing secondary concerns for the improvement of areas such as participation and quality. This links back to the wider literature on neoliberalism and planning concerning the ‘negative externalities’ that can accrue from the pursuit of ideological shibboleths centring on free markets (rather than the state or civil society) as the most effective mechanism to organise, produce and distribute resources in contemporary societies. Hence the prioritisation of development and finance. In other words, these logics align with the ‘structure’ of national and international elite thinking on how to deliver growth. This leads to the second and related issue of ‘agency’ to operate within such contexts that shape the institutional corporate and financial leadership of local authorities; whereby planners either ‘fall in line’ and (re)rationalise their behaviours according to these nested logics, or risk facing the consequences of choosing to prioritise alternatives. It is clear that asking planning practitioners to be more ‘political’ in this context is relevant but risks destabilising their career on the one hand and overestimates their power on the other (although see Albrechts, Citation2020).

Therefore the stakes are much higher than the focus on pre-apps as ‘negotiative’ space may suggest on a first reading. The question of how neoliberal thought pervades the whole planning system are substantive, and particularly where issues concerning, for example, housing affordability, environmental degradation and climate change are not being robustly addressed or are otherwise sacrificed in the English system. Further research could examine and reflect on how these logics are operationalised and sustained across different policy contexts and planning spaces. This could usefully deepen knowledge about how neoliberal planning agendas are shaped, promoted or challenged internationally, and their impact on both trust in planning processes and the delivery of substantive goals.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gavin Parker

Gavin Parker is Professor of Planning, Department of Real Estate and Planning at the University of Reading, UK.

Mark Dobson

Mark Dobson is Lecturer in Planning and Development, Department of Real Estate and Planning at the University of Reading, UK.

Tessa Lynn

Tessa Lynn is Principal Consultant at the Kingfisher Commons consultancy, UK.

References

- Albrechts, L. (2020). Planners in politics: Do they make a difference? Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Alexander, E. (2000). Rationality revisited: Planning paradigms in a post-postmodernist perspective. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X0001900303

- Allen, J. (2003). Lost geographies of power’. Blackwell.

- Allmendinger, P., Haughton, G., & Shepherd, E. (2016). Where is planning to be found? Material practices and the multiple spaces of planning. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(1), 38–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614178

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2012). Post-political spatial planning in England: A crisis of consensus? Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 37(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00468.x

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2013). The evolution and trajectories of English spatial governance: ‘Neoliberal’ episodes in planning. Planning Practice & Research, 28(1), 6–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.699223

- Blanco, I., Griggs, S., & Sullivan, H. (2014). Situating the local in the neoliberalisation and transformation of urban governance. Urban Studies, 51(15), 3129–3146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014549292

- Bradley, Q. (2021). The financialisation of housing land supply in England. Urban Studies, 58(2), 389–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020907278

- Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. (2020, January). Living with beauty (Report). https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/building-better-building-beautiful-commission

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2021). The Cambridge English Dictionary online. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/

- Clifford, B. (2016). Clock-watching and box-ticking’: British local authority planners, professionalism and performance targets. Planning Practice & Research, 31(4), 383–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2016.1178038

- Coaffee, J., & Healey, P. (2003). My voice, My place: Tracking transformations in urban governance. Urban Studies, 40(10), 1979–1999. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098032000116077

- Conservative Party. (2010, February). Open source planning (Policy paper 14). London: The Conservatives.

- DCLG/MHCLG. (2011). ‘The Local Government Finance Report (England)’ from 2010/11 – 2020/2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/local-government-finance-reports

- DCLG. (2009). Development management: Proactive planning from pre-application to delivery.

- Dean, M. (1999). Governmentality: Foucault, power and social structure. Sage.

- Dobson, M. (2019). Neoliberal business as usual or paradigm shift? Planning under austerity localism [Doctoral thesis]. University of Reading.

- Dobson, M., Lynn, T., & Parker, G. (2020). Pre-application advice practices in the English planning system. Town and Country Planning, 89(6–7), 196–201.

- Ferm, J., & Raco, M. (2020). Viability planning, value capture and the geographies of market-led planning reform in England. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1754446

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1998). Rationality and power: Democracy in practice. University of Chicago Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (1996). The dark side of planning: Rationality and realrationalität. In S. Mandelbaum, L. Mazza, & R. Burchell (Eds.), Explorations in planning theory (pp. 383–394). Center for Urban Policy Research Press.

- Foucault, M. (1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon, & P. Miller (Eds.), The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality (pp. 87–104). University of Chicago Press.

- Grosvenor. (2019). Rebuilding trust. Discussion Paper. https://www.grosvenor.com/Grosvenor/files/b5/b5b83d32-b905-46de-80a5-929d70b77335.pdf

- Gunder, M. (2010). Planning as the ideology of (neoliberal) space. Planning Theory, 9(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095210368878

- Harris, N., & Thomas, H. (2011). Clients, customers and consumers: A framework for exploring the user-experience of the planning service. Planning Theory & Practice, 12(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.580157

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., Counsell, D., & Vigar, G. (2009). The new spatial planning: Territorial management with soft spaces and fuzzy boundaries’. Routledge.

- Healey, J. (2013). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries and spatial governance in post‐devolution Wales. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(4), 1325–1348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01149.x

- Healey, P., & Barrett, S. M. (1990). Structure and agency in land and property development processes: Some ideas for research. Urban Studies, 27(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989020080051

- Healey, P. (2003). Collaborative planning in perspective. Planning Theory, 2(2), 101–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952030022002

- Healey, P. (2006). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our times. Routledge.

- Inch, A. (2018). ‘Opening for business’? Neoliberalism and the cultural politics of modernising planning in Scotland. Urban Studies, 55(5), 1076–1092. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016684731

- Jones, P., & Comfort, D. (2019). Commercialisation in local authority planning. Town and Country Planning, 88(1), 32–36.

- Local Government Association [LGA]. (2014). Pre-application suite. Retrieved July 23, 2020, from https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/10-commitments-effective–46b.pdf

- Local Government Association. (2017). Enterprising councils. Supporting councils’ income generation activity. LGA.

- Lord, A., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2014). Is planning “under attack”? Chronicling the deregulation of urban and environmental planning in England. European Planning Studies, 22(2), 345–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.741574

- Lukes, S. (1974). Power: A radical view. London: Macmillan.

- Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG]. (2019). National planning policy guidance online.

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government [MHCLG]. (2020, August 6). Planning for the future. Planning White Paper. MHCLG.

- National Audit Office [NAO]. (2020, March). Departmental review. Local Government.

- Newman, J. (2014). Landscapes of antagonism: Local governance, neoliberalism and austerity. Urban Studies, 51(15), 3290–3305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013505159

- NPG [National Planning Guidance]. (2019a). Before submitting an application. Retrieved November 14, 2019, from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/before-submitting-an-application

- NPG [National Planning Guidance]. (2019b). Enforcement and post-permission matters. Retrieved November 14, 2019, from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ensuring-effective-enforcement

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister [ODPM]. (2002). Sustainable communities: Delivering through planning.

- Parker, G., & Arita, T. (2019). Planning transparency and public involvement in pre-application discussions. Town and Country Planning, 88(2), 66–70.

- Parker, G., Dobson, M., & Lynn, T. (2021a). Community involvement opportunities for the reformed planning system: Frontloading and deliberative democracy. University of Reading. http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/98773/1/Community%20Involvement%20Report%20June_2021_FINAL.pdf

- Parker, G., Dobson, M., & Lynn, T. (2021b, October). ‘Paper tigers’: A critical review of statements of community involvement in England (Published report). Reading, UK: University of Reading. http://www.civicvoice.org.uk/uploads/files/SCI_Research_Final_Report_Oct21.pdf

- Parker, G., Street, E., & Wargent, M. (2019). Advocates, advisors and scrutineers: The technocracies of private sector planning in England. In M. Raco, and F. Savini (Eds.), Planning and knowledge: How new forms of technocracy are shaping contemporary cities (pp. 157–167). Bristol: Policy Press.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2017). Public management reform (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Reay, T., & Hinings, C. (2009). Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30(6), 629–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609104803

- Reimer, M., Getimis, P., & Blotevogel, H. (2014). Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe: A comparative perspective. In Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe. A comparative perspective on continuity and changes (pp. 1–20). Routledge.

- Rivero, J., Teresa, B., & West, J. (2017). Locating rationalities in planning: Market thinking and its others in the spaces, institutions, and materials of contemporary urban governance. Urban Geography, 38(2), 174–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1206703

- Rose, N., O’Malley, P., & Valverde, M. (2006). Governmentality. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 2(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.2.081805.105900

- RTPI. (2019, July). Resourcing public planning. RTPI research paper. RTPI.

- Sager, T. (2011). Neo-liberal urban planning policies: A literature survey 1990–2010. Progress in Planning, 76(4), 147–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2011.09.0

- Savini, F., & Aalbers, M. (2016). The de-contextualisation of land use planning through financialisation: Urban redevelopment in Milan. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), 878–894. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776415585887

- Scott, R. (2001). Institutions and organizations. Sage.

- Shaw, D., & Lord, A. (2007). The cultural turn? Culture change and what it means for spatial planning in England. Planning, Practice & Research, 22(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450601173538

- Shepherd, E. (2020). Liberty, property and the state: The ideology of the institution of English town and country planning. Progress in Planning, 135, 100425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2018.09.001

- Slade, J., Tait, M., & Inch, A. (2021). We need to put what we do in my dad’s language, in pounds, shillings and pence’: Commercialisation and the reshaping of public-sector planning in England. Urban Studies, 004209802198995. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098021989953

- Tasan-Kok, T., & Baeten, G. (eds.). (2011). Contradictions of neoliberal planning: Cities, policies, and politics. Springer.

- Venugopal, R. (2015). Neoliberalism as concept. Economy and Society, 44(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2015.1013356

- Verma, N. (1996). Pragmatic rationality and planning theory. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 16(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9601600102

- Waldron, R. (2019). Financialization, urban governance and the planning system: Utilizing ‘development viability’ as a policy narrative for the liberalization of Ireland’s post‐crash planning system. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(4), 685–704. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12789

- Wargent, M. (2021). Localism, governmentality and failing technologies: The case of Neighbourhood Planning in England. Territory, Politics, Governance, 9(4), 571–591. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1737209

- Watson, V. (2003). Conflicting rationalities: Implications for planning theory and ethics. Planning Theory & Practice, 4(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935032000146318

- Watson, V. (2013). The ethics of planners and their professional bodies: Response to Flyvbjerg. Cities, 32, 167–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.003

- Yiftachel, O. (1998). Planning and social control: Exploring the dark side. Journal of Planning Literature, 12(4), 395–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/088541229801200401