Contents

Introduction: Disability Justice and Urban Planning

Lisa Stafford and Leonor Vanik

Planners, We Need to Talk about Ableism

Lisa Stafford

Leaky Bodies and Broken Bathrooms: Stories about Ableism and Going to the Loo

Ron Buliung and Rhonda Cheryl Solomon

Beyond Physical Access: The Importance of Thinking about Inclusion

Pippa Rogers

How to Make Every Space More Welcoming to Disabled People (Maybe Even Outer Space)

Hannah E. Silver

Ableism in Communicative Planning: An Autistic Perspective

Daniel Salomon and Minji Cho

Hindsight isn’t Necessarily 20/20: Reflections on Ableism in Planning Education and Practice

Gail Dubrow and Laura Leppink

Disability Justice Meets Climate Justice

Lisa Stafford and Ron Builing

A Conversation Amongst Disability Justice and Urban Planning Advocates

Leonor Vanik, Nikki Brown-Booker, and Dessa Cosma

An Artist’s View of Disability Justice and Urban Planning

Vincent Uribe and Arts of Life artists

Call to Action

From the collective authors of the Interface

Introduction: Disability Justice and Urban Planning

Lisa StaffordLeonor VanikDespite it being six decades since the disability rights movements in areas like North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia, where steadfast activists (past and present) called for an end to the oppression and institutionalisation of disabled and chronically ill people – we are still here, still being excluded.

While a raft of measures have been implemented due to disabled people’s activism such as community living, physical and digital accessibility, and anti-discrimination legislation – for many disabled people worldwide; dignity, choice, and control are still not realized.

The adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2006 should have been another significant turning point – yet the rights of disabled people cannot be fulfilled by the same entrenched ableist, colonist institutions and systems that continue to subjugate us.

In urban planning and design, these prejudices are played out and reflected in the built and digital form – through our housing and streets, infrastructure, interiors and exteriors, public and private spaces. Exclusion of body-mind diversity is far and wide – disabled people are constantly reminded that “you don’t belong—the world is not built for you.” Public planning conversations about matters that affect our lives fail to incorporate our diverse communication needs, or worse still – we’re not even thought about at all. Basic things like going to the toilet or taking public transport to attend an appointment are acts taken for granted by many–while these same acts for disabled people can require exhaustive planning with contingencies. Many trips are disrupted or not made due to being too adversarial and hard to navigate. Injustices and oppressions are also not experienced evenly; deep intersections are at play, as reflected by activist Indigenous disabled people, disabled people of colour, disabled people in the global south, queer disabled people, and disabled women and girls.

Across the globe disabled people’s identity and voice is strengthening. There is growing resistance and push back against the omission of and apathy towards disabled people.

This edition of Interface – Disability Justice and Urban Planning – reflects critically on urban planning’s role and calls into question the oppression of disabled people through ableist neoliberal policy, education, and practice.Footnote1 It seeks to bring visibility to a large and diverse group of people who have been unseen, excluded, and siloed for too long; and to open up conversations about disability justice and the embracing of our body-mind diversity.

We had an overwhelming number of responses to the call for contributions – sadly, more than could be accommodated in this edition. We also want to acknowledge the challenges to disabled authors around the globe working with a very specific journal production deadline – everyone’s professional and personal pressures, and bodies and minds all had to line up to hit dates– and we hope to see more of those writings in future commentaries.

The unique collection of short articles and reflections here speak to the heart of this edition – going beyond discussing accessibility to recognise and delineate how deeply ableism is embedded in planning theory, research, education, and practice, and to engage with vision and imagination about what it would look like to plan and make urban policy from a foundation of disability justice.

We are so excited about the powerful contributions and messages on disability justice and urban planning made by the diverse contributions of academics, students, practitioners and activists with different positionality – most of whom identify as disabled person/person with disability, or person with lived experience of disability.

We use the language of “disabled people” in line with social and critical models of disability that recognise that people with impairments and illness are disabled by society through the effects of ableist attitudes, systems and infrastructure, rather than the functioning of people’s minds, bodies and senses. However, we also acknowledge and respect that “person-first” language, which uses the phrasing “a person with – a condition or diagnosis,” is also used by some authors and is preferred by some in the disability community.

The edition commences with co-editor – Lisa Stafford, a disabled planning scholar and practitioner who opens up the conversation on ableism – a conversation we as a profession must have – Planners – We Need to Talk About Ableism. Lisa explains what it is, how it operates and permits the othering of disabled people, but importantly shows through examples from cities and towns around the world – what is being done to address exclusion by design through deliberative inclusive approaches to planning.

The next article Leaky Bodies, by Ron Buliung and Rhonda Solomon, is a poignant article that explores one of the most taken-for-granted built spaces there is – the toilet/bathroom. Personal account and critical questioning expose how a token compliance approach to buildings, such as toilets, simply do not cope with diverse leaky bodies. Such broken spaces render bodies to undignified experiences. The article shows this does not have to be the way – drawing on changing places as an example of the provision of dignified toilets/bathrooms.

Pippa Rogers, an expert-by-experience research assistant and person with disability, shares her personal story on Beyond Physical Access: The Importance of Thinking About Inclusion. Here Pippa shows the deep connection between stigma, built environment, and isolation, and the need to think about accessibility more broadly – encompassing social, physical and sensory access and inclusion as well as a connection with community to help make change.

Hannah Silver, an urban design instructor, who identifies as invisibly disabled, builds on Pippa’s personal story, by critically calling into question the sacredness of public and third places. Hannah reminds us of our duty and responsibility as urban planners and designers for shaping, not only our current places, but also public conversations about future spaces in her article How to Make Every Space More Welcoming to Disabled People (Maybe Even Outer Space).

Part of this responsibility is also ensuring disabled people are part of planning processes. There is a saying in the disability community “Nothing about us without us,” which is conveyed by Daniel Salomon’s and Minji Cho’s article Ableism in Communicative Planning: An Autistic Perspective. Daniel and Minji provide a critical and reflective understanding of communicative planning from a Neurodiversity perspective. Their article highlights how people on the autism spectrum experience exclusion in communicative planning process and provide ways forward to achieve the intended goal of authentic, inclusive dialogue.

This next article brings us to planning education. Gail Dubrow and Laura Leppink for REPAIR (Rethinking Equity in Place-based Activism, Interpretation, and Renewal: Disability Heritage Collective)– offer a compelling critical and personal reflection on planning education and practice in the context of historic planning – entitled Hindsight Isn’t Necessarily 20/20: Reflections on Ableism in Planning Education and Practice. The article commences with a specific dedication to the late Barbara Faye Waxman Fidducia, a brilliant disabled planning scholar who not only called out ableism but illuminated the inseparability of disability from planning. Through reflecting on her own scholarly journey and acquired visual impairment, Gail discusses the ableist foundations that exists in even the most progressive planning theories and practices – showing that we have a steep road to climb – but one that is possible – to achieve disability justice.

This brings us to the existential threat facing mother earth and inhabitants – Climate Change. While decades of climate policy have been established, the same area of policy has ignored or downplayed the involvement of key groups – Indigenous people and disabled people. In this short article we (Ron Buliung and Lisa Stafford) pay tribute to the steadfast disabled climate activists who at the intersection of racism, ableism and colonialism are calling out the failings of urban and climate policy interventions. These activists are leading the charge – one which urban planning must listen to by centring disabled people and Indigenous people in climate adaption urban policy and urban design inventions.

Our penultimate article is an excerpt from a series of conversations our co-editor, Leonor, had with her Disability Justice colleagues, Nikki Booker Brown and Dessa Cosma, where they explore opportunities for urban planners to include the disability community in the planning process. Here they provide personal reflections as disability activists on defining what disability justice can be; engaging the disability community in the planning process; and their thoughts for a call to action.

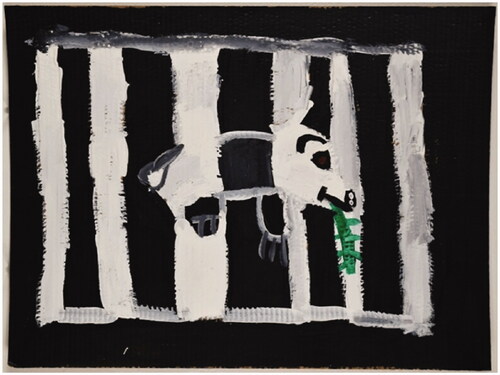

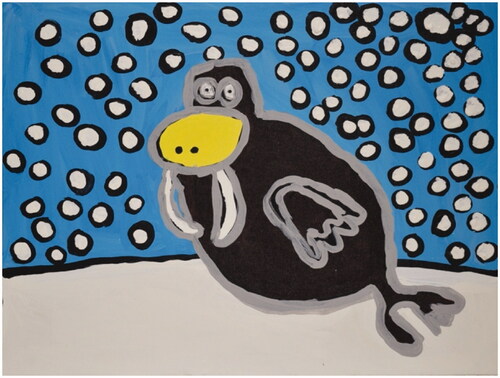

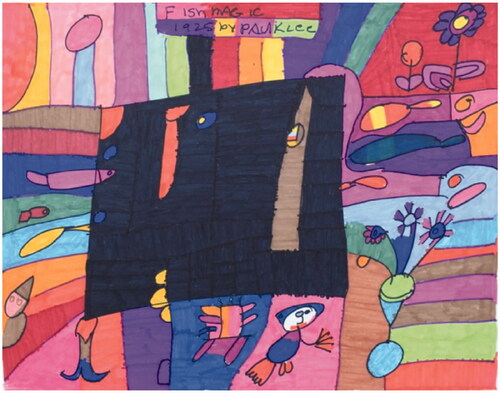

Rounding out the contribution is a compelling series of visual illustrations of the themes by eight artists with disabilities – Marcelo Añón, Nikki Huesman, Jean Wilson, Andrew Sloan, Alex Scott, Maria Vanik, Cole Fox and Chris Austin. Each artist is a member of the Arts of Life community – which advances the creative arts community by providing artists with intellectual and developmental disabilities a collective space to expand their practice and strengthen their leadership. The collection was enabled and curated by Vincent Uribe, Director of Exhibitions and External Relations, and Denise Fisher, Co-Founder/Executive Director.

The hope for this edition is to engender authentic conversations and more deliberative transformative planning education and practices towards disability justice by our urban planning profession.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Reference

- Sins Invalid. (2015, September 17) 10 Principles of disability justice. Sins Invalid. https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice

Planners, We Need to Talk about Ableism

Lisa StaffordOver the last 18 months, the global COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns have provoked more insight into what it’s like to not be able to move about freely and interact outside of our own “four walls.” The pandemic has revealed things we took for granted; magnified how wellbeing is eroded by the poorly-planned, -designed, and -invested in; and further exposed the growing exclusion and inequality experienced by marginalised groups and communities, many of whom are made up of disabled and chronically ill people.

As I read calls from our professions that “we can’t go back to the way things were” in how we plan and design communities and cities – I admit I was excited for a potential shift towards spatial justice for our diverse disabled and chronically ill communities. As restrictions eased, people acted with creativity, and placemaking activities were shared over planning networks. But as I looked on eagerly, I noticed how many of these ideas and approaches privileged ableness – failing to consider and respond to the diverse ways our body-minds inhabit, sense and experience space. Simple things, instead of emancipating, actually maintained our exclusion and isolation. Pop-up cafes and parklets used tape barriers and step-up platforms, while planter boxes or pallet seating were positioned to create what seemed like another obstacle course in getting about. Even with social distancing, there remains little refuge from sensory bombardment for those who need it. So, with a deep sigh … and some rage … . it struck me that as a society and a profession how little we have learned.

So, Why Are We Still Here?

Meet ableism – an insidious, unspoken and unchecked prejudice that favours an idealistic view of an “able body.” According to Vera Chouinard (Citation1997), a disabled scholar herself and one of the earlier writers on ableism, space and geographies, ableism is based on “ideas, practices, institutions, and social relations that presume able-bodiedness, and by doing so construct persons with disabilities as marginalized … and largely invisible ‘others’” (p. 380). Since the late 1990s, studies of ableism have flourished. Fiona Kumari Campbell, a leading disabled scholar of ableism, makes an important distinction that ableism is not just about negative views held about disabled people, but “is a trajectory of perfection, a deep way of thinking about bodies and wholeness” that rejects difference (Citation2014, p. 80).

Privilege and power are only afforded to a person that meets this able-body-in-space – that is the white, young, able, hetero male that Rosemary Garland-Thomson (Citation2017, p. 8) describes as the “the normate.” Normative conceptions of the body and the power it holds have been explored critically by feminist, race, crip and queer scholars (Weiss, Citation2015), illustrating how social-cultural and spatial processes uphold the normate. Research has also shown how identity, abilities, and markets are linked to deeply rooted assumptions of ability and normalcy (Wolbring, Citation2008). A normative body possesses value and worth and is afforded physical, social, economic, cultural capital (Campbell, Citation2014), while body-mind differences – a natural characteristic of being human – are constructed as misfits, unruly, hideous and burdensome through standardised language and images.

So, What Does This Have to Do with Urban Planning?

Despite being unrepresentative, this able-body-in-space has been upheld as the prototype to guide the planning of our cities and communities for centuries. This intensified in the twentieth century through the obsession with anthropometrics (Stafford & Votz, Citation2016), technocratic rationalism and the belief that urban planning is somehow neutral – a belief that Jane Jacobs (Citation1961) first debunked, followed by too many critical planning scholars to name.

Ableism exists across urban and regional planning, yet it is largely unknown, untaught, and unchecked in planning education and practice. It is entrenched in urban policy, codes, transport systems, and in the designs of our streets and communities. Ableism permeates walkability metrics and indices (Stafford & Baldwin, Citation2018), our approaches to livability (Badlands & Pearce, Citation2019; Baldwin & Stafford, Citation2019), and even lifespan approaches like 8–80 Cities (2014) which have sought to address ageism in planning, but unwittingly preserve ableism through narrow views of disability and “one-size-fits-all” approaches to mobility (Stafford & Baldwin, Citation2018). The invisibility of disability throughout planning reaffirms the othering of diversity.

Ableism is also rampant in planning and design decisions. Time and again I have heard universal design omitted in the provision of social infrastructure, due to budget shortfalls or due to inclusivity being “too hard” (code for too costly), a narrative that reveals for whom investments are not made. It still amazes me how often I hear “oh but that’s only a small proportion of the population,” yet disabled people represent anywhere from 17% upwards in global north countries and 26.8% in Tasmania, Australia, where I live (ABS, Citation2019). This is also evident in active transport policy and plans that omit access for disabled people, as outlined by Canadian Disabled Activist Gabriel Peters (https://mssinenomineblog.wordpress.com/2021/08/20/some-of-us-get-the-long-guns-accessibility-and-inclusion-and-making-and-holding-space/). Such inequalities continue to show how disabled people are not seen as equal or worthy of the same access to social infrastructure.

Planning is constantly making decisions on what and who to plan for. As Makani Themba, in the foreword to Bailey, Lobenstine and Nagel’s publication (Spatial Justice: a frame for reclaiming our rights to be, thrive, express and connect. Citation2012) notes “space is a place of intersecting struggles/oppression/opportunities. How we move or not move through it … shapes everything we do and big parts of who we are.” It is through ableist planning policy and practice that our profession contributes to the socio-spatial marginalisation, exclusion and oppression of disabled – chronically ill people. This is no more evident than in colonised Australia, where for more than 4.4 million Australians with disabilities, mobility and being-in-space remain conditional acts based on where you live, who you are, and the design of place around you: Recent Australian disability discrimination data shows one in three people had difficulty accessing locations or facilities due to barriers in mobility, sensory, communication, and information (AIHW, Citation2020). This is Exclusion by Design, socially created through our ableist frame of reference.

So, We Need to Talk About Ableism

Disability Justice in urban planning can’t be realised until we start to talk about ableism. The hardest part can be knowing where to start and addressing the fear of getting it wrong. My advice; start simply with what you are doing now – reading and getting informed. There is an amazing depth of ableism scholarship and disabled or chronically ill advocates – too many to list – but a good starting point is https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/about/. You can share and discuss readings with colleagues, you could even share this Interface edition. Most people don’t actually meet the “normate” requirement, so start there. Welcome disabled planners, engage with disability communities’ expertise, elevate the need for ableism education in planning associations. There are so many ways to start.

Another low hanging fruit, as we like to say in planning, is checking your own ableism. Whatever your field, you can simply ask the question in your own practice – for whom are we planning? Are we considering the diverse ways our body-minds inhabit, sense and experience space? This thinking can also encompass whole-of-life spatial needs – infants and toddlers, parents with prams, pregnant women, temporary injuries, older people. By critically reflecting about ableness, we can start to reframe our own learnt ableist thinking and ways of doing.

However, ableism cannot be the only lens – as ableism is not experienced evenly, nor the only oppressive prejudice at play. We must acknowledge axes of difference in identities, experiences and oppression. Ableism must be considered alongside intersectionality (see Kimberly Crenshaw’s work) and Indigenous knowledges (see the depth of Indigenous knowledge scholarship available, see Interface edition Porter et al., Citation2017). Embracing diversity without oppression is crucial for Indigenous disabled people, disabled people of colour, disabled people from the global south, disabled girls and women, low-income disabled people and LGBTIQA + disabled people.

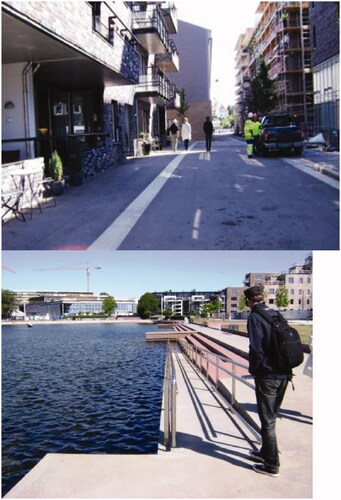

As planners, we can be more outward looking, open to more perspectives, and think more deeply about the connection between planning, design and society (Whiteley, Citation1997). Ideas like the Urban Village or 15-min Neighbourhood have merit, but must foreground diversity if they are to be just. An example of such foregrounding is the American Planning Association (Citation2011) multigenerational approach to neighbourhoods, where universal design (UD)Footnote2 and smart growth principles are considered simultaneously to meet the needs of various ages and abilities, understanding that everyone benefits from such an approach. Norway has also been a leader in embedding UD as a key planning strategy and applying it in everyday practice across municipalities (Ministry of the Environment (Norway), Citation2009). This includes infill development and public space renewal as in , which I observed from my trip to Norway in 2012, exploring examples of UD in action.

In terms of active transport, work like A Guide to Inclusive Cycling 2019 (2nd edition) (https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/FINAL.pdf) and the Bicycle Mayor of Halifax, Canada – Jillian Banfield’s blog (https://bycs.org/curbing-traffic-through-the-eyes-of-halifaxs-bicycle-mayor/) – discusses how to ensure disability is a natural part of the conversation and that diversity is promoted in active transport. Public Transport is also afflicted by inequality across the whole of a journey – yet there are examples showing inclusion and suitability working side by side – such as Australia’s Brisbane Rapid Bus Way and the Light Rail Transit in Paris, France (see ) and inclusive streets in Australia (see ).

Planning can make social change – it is more than regulating space, use and movement – it shapes lives and livelihoods. But to make real change, we need to confront ableism and dominant normative ideas that fail people. We now have a unique opportunity – awakened through our collective experience – to shape our approach to planning and creating more inclusive liveable communities for all, with renewed attention towards justice, engendering belonging and embracing our diversity.

Figure 1. Infill development and public space renewal Kristiansand Norway.

Image description: Images are of infill development in Norway using universal design principles in progress. Image A shows ease of access entry to new residential building and flat footpath same level. Image B is of a ramp with hand rails leading into a public lake for swimming as part of foreshore public space redevelopment approached from universal design principles. Image Sources: Stafford (Author), 2012.

Figure 2. UD Rapid Bus Way, Brisbane Australia.

Image description: (A) Universal Design and Green Design Light Rail Transport and Platform. An accessible bus as part of a rapid bus transit in Brisbane Australia is parked at an accessible bus stop designed using universal design approaches. (B) A picture containing tree, accessible outdoor platforms, light rail in Paris using universal design and green design approaches. Image Sources: Stafford.

Figure 3. Inclusive street in regional town Australia that enables connections, space to pause and belong.

Image description: A young person in an electric wheelchair patting a white furry dog on the footpath of town centre, the owner of the dog kneeling down to talk to the young person. There is also another dog in the background looking on – has white and black spots. Image Source: Stafford.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Planning Association. (2011). Multigenerational planning: Using smart growth and universal design to link the needs of children and the aging population (Family-friendly briefing papers 02). American Planning Association. https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/publication/download_pdf/Using-Smart-Growth-to-Link-Children-and-Aging.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019, October 24). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disabilityageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release

- AIHW. (2020). People with disability in Australia: In brief retrieve from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia-in-brief/contents/how-many-experience-discrimination

- Badland, H., & Pearce, J. (2019). Liveable for whom? Prospects of urban liveabilty to address health. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 232, 94–105.

- Bailey, K., Lobenstine, L., & Nagel, K. (2012). Spatial justice: A frame for reclaiming our rights to be, thrive, express and connect. Design Studio for Social Intervention https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53c7166ee4b0e7db2be69480/t/56cdf572fe5f74e12254ec7f/1325265917337/Spatial_Justice_DS4SI.pdf

- Baldwin, C., & Stafford, L. (2019). The role of social infrastructure in achieving inclusive liveable communities: Voices from regional Australia. Planning Practice & Research, 34(1), 18–46.

- Campbell, F. K. (2014). Ableism as transformative practice. In Rethinking anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive theories for social work practice (pp. 78–92). Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

- Chouinard, V. (1997). Making space for disabling difference: challenging ableist geographies. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 15, 379–387. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1068/d150379

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2017). Extraordinary bodies: figuring physical disability in American culture and literature (Twentieth anniversary ed.). Columbia University Press.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

- Ministry of the Environment. (Norway) (2009). August). Universal design as a municipal strategy: experience and results from the pilot municipality project 2005–2008 (Eckmann C B, Trans). (T-1472 E). https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/76dc9f0cce8a487d8e86c0bda613545f/t-1472e.pdf

- Porter, L., Matunga, H., Viswanathan, L., Patrick, L., Walker, R., Sandercock, L., Moraes, D., Frantz, J., Thompson-Fawcett, M., Riddle, C., & Jojola, T. (T. ). (2017). Indigenous planning: From principles to practice/A revolutionary pedagogy of/for Indigenous planning/Settler-Indigenous relationships as liminal spaces in planning education and practice/Indigenist planning/What is the work of non-indigenous people in the service of a decolonizing agenda?/Supporting Indigenous planning in the city/Film as a catalyst for Indigenous community development/Being ourselves and seeing ourselves in the city: Enabling the conceptual space for indigenous urban planning/Universities can empower the next generation of architects, planners, and landscape architects in Indigenous design and planning. Planning Theory & Practice, 18(4), 639–666. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1380961

- Stafford, L., & Volz, K. (2016). Diverse bodies-space politics: Towards a critique of social (in)justice of built environments. TEXT, 34, 1–17 http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue34/Stafford&Volz.pdf

- Stafford, L., & Baldwin, C. (2018). Planning walkable neighbourhoods: Are we overlooking diversity in abilities and ages? Journal of Planning Literature, 33(1), 17–30.

- Weiss, G. (2015). The normal, the natural and the normative: A Merleau-Pontian legacy to feminist theory, critical race theory and disability studies. Continental Philosophy Review, 48(1), 77–93.

- Whiteley, N. (1997). Design for society. Reaktion Books. ProQuest ebrary.

- Wolbring, G. (2008). The politics of ableism. Development, 51(2), 252–258.

Leaky Bodies and Broken Bathrooms: Stories about Ableism and Going to the Loo

Ron BuliungRhonda Cheryl SolomonHow did we get here? Kneeling close to the floor, gently and (care)fully placing my daughter’s body onto a beach towel we brought with us … again, because we have learned, through repeat exposure to unimaginatively produced, broken, and ableist design and infrastructure, to expect to have to change her on the dirty floor of a public bathroom EVERY time we venture out into the city.

Leaving the house with our disabled child has become a mind-bending logistical puzzle, and venturing out into the world, an act of resistance. We resist the temptation to simply disappear, to avoid the rows of staring eyes. We resist the temptation to simply give in to the exhaustion of resisting – and the unseen labour of trying to re-imagine, re-work, make work public infrastructure(s) designed and installed without having “us” in mind.

Who is “us”? We are just one family, one group of bodies of the many bodies out there disabled by “them,” the makers of this place. One assemblage of bodies, materials, and resources that does not fit the mold of the so-called neo-liberal “able” body – a body that can pee standing up or sitting down, a body that can leak with limited concern for where and when this happens, a body that can move freely in the spaces designed for it. And so, here we are again, alone in this place, the floor of a broken public restroom, pouring our love, our energy, and care into our child’s life, to make, for her and for us, a day that we will recall later as being one of our greatest adventures.

Ron B

Why is it that washrooms, bathrooms, loos, WCs, lavatories, latrines, and restrooms (public or private) seem to largely escape acts of thoughtful inclusive design and installation? We ask because token compliance with “the code” regarding accessible washroom installation, in the spatially obscure interior spaces of buildings, has been practiced for too long now. Is it simply that we can’t cope with our leaky bodies (Goodley, Citation2014; Shildrick & Price, Citation1999)? If yes, why? Perhaps because the modern public toilet is largely marked as a heteronormative space where “able” bodies are expected to perform in specific ways. A place where toilets, sinks, faucets, hand dryers, doors, ledges, change tables (maybe), and rolls of toilet paper lay dormant, waiting to be brought to life through moments of interaction with the types of bodies they have been designed and installed for: bodies that do “normal.”

Indeed, lack of universally accessible public washrooms in buildings used by the public often leaves people with severe disabilities and their caregivers (this type of care work is highly gendered) exposed to degrading and dehumanizing “away from home” toileting experiences, such as being changed on the washroom floor and sitting in soiled clothing when a suitably accessible washroom can’t be found. Because of the conditions to which they are subjected, many parents of children with disabilities, as well as many caregivers of adults with disabilities, choose not to, or indeed are unable to, leave home at will. Consequently, people with severe disabilities are at high risk of experiencing profound social isolation (Johnson, Citation2019).

In some cities, even “able” bodies are finding it increasingly difficult to leak in the public realm because quasi-public restrooms (e.g., Starbucks and McDonald’s) are becoming increasingly securitized spaces with codes or tokens for entry. The pandemic has made the situation even worse. We have been living outside probably more than ever as we have moved indoor activities into outdoor spaces with better ventilation. At the same time, public toilets (however defined) have been shut down and locked up to reduce the risk of aerosol virus transmission in the public realm (Cecco, Citation2021; Lowe, Citation2018; Moore, Citation2021). If the toilet situation is grim for the so-called able-bodied, then it is indeed entirely dire for people already disabled pre-COVID-19 by the absence of accessible public toilet facilities.

This is not the first time the question of “where” we empty our bladder and/or bowels has come under scrutiny, triggering intervention by the state. For example, in her book, “The Porcelain God: A Social History of the Toilet,” Julie Horan discusses state and police intervention into the “where” question during the early modern period in Paris, and across Europe, during periods of viral outbreak. Indeed, the public toilet has long come under scrutiny as a hazardous or dangerous place, a place to be policed, closely monitored, erased, locked down (Lowe, Citation2018). Moreover, in the neo-liberal city everything has a price, and so in some places in some cities, for instance in the Paris Métro, there are public and private toilets that charge a fee to pee. Pay toilets, however, are not a unique feature of the neo-liberal city; historians have traced that origin story to Rome (Magner, Citation1992).

Having travelled extensively for personal reasons and for reasons related to my work, and because I (Ron) am human, I have a relatively large experientially derived sample of toileting experiences to draw from. My experiences indicate a rather grim situation indeed, where normatively configured so-called “able bodies” of a particular size, stature and mobility are privileged within the toileting scene; they will not work for every body. Indeed, thinking about the diversity of disability in toilet design and installation appears to remain largely elusive. In their book, “Doing disability differently: An alternative handbook on architecture, dis/ability, and designing for everyday life,” Jos Boys cites the experience of Peter Anderberg, who paradoxically points to the disabling experience of using an adapted bathroom: “The bathroom held a number of different advanced adaptations; these were not helpful but rather in the way for me, and made the bathroom virtually unusable” (Boys, Citation2014, p. 29).

Many of our readers will likely have observed stalls with wider doors, hand railings around a potentially lowered bowl, and so on. These elements of design fit with a particular, and rather limited, idea about what disabled bodies do, what disabled people want and need, and how they want to and can move. And so, even when some “body” tries to get it right, the end result is often only superficially accessible, while in the broadest sense, functionally. Anecdotally, some of the first author’s best experiences toileting his child have occurred when things are arguably at their worst: when in hospital. The children’s hospital: a toileting oasis complete with adult-sized bath chairs, mats, tables, commodes and so on. To use these spaces, and to have the best experience possible with your leaky body, you have to be a client using clinical services. And even in that setting, the toileting spaces are not universally set up to work for every body.

I can’t help but wonder if planners, institutions, and the designers of public toilets should do some serious thinking about the issues behind what Titchkosky (Citation2008, p. 54) calls “careless caring,” – “a gesture to the act of caring, such as placing an icon of access on a door”-- or installing an accessible washroom that meets minimum requirements, yet screams of an unimaginative, Cartesian way of thinking about disability. Boys too writes about care – ”public care”: “the moments that act to support diverse bodies as we go about our ordinary lives, from door handles, to handrails, to places to sit, to public facilities” (Boys, Citation2014, p. 154). Careless caring, with intent or otherwise, when scattered across our cities, ultimately produces a failure in public care. Token compliance with code in the production of “accessible” public toilets fails to support the everyday lives of disabled people.

So, what would a public toilet look like if it was designed from the start with “disability” in mind? If we took greater care in our public care? Or, perhaps cast another way, what would a public toilet look like and how would it operate if the process(es) of design and installation were not ableist? If, indeed, these processes and resulting materials, equipment, and installations were conceived and assembled with a view to working for every body? Perhaps Changing Places toilets offer a way forward.

Changing Places toilets (Changing Places, Citation2021), first advocated for in the UK in 2003, are toilets designed to be completely accessible for people who are not able to use the toilet independently. Changing Places facilities provide: a height-adjustable adult-sized change table; a constant-charging ceiling track hoist system; a centrally-located peninsula toilet; circulation spaces as defined in the design specifications; an automatic door with a clear opening of 950 mm at a minimum (1100 mm for beach and lake locations); and a privacy screen. Changing Places toilets are intentionally designed and installed with all bodies in mind, and the multitude of ways these bodies “leak” (to be precise, not all bodies leak standing up in one square meter or less of space). Unlike the typical “accessible toilet” – these state-of-the-art restroom facilities are intentionally equipped to empower all bodies to access an away-from-home toilet with dignity and with acknowledgement of their human rights for a safe and comfortable place to be toileted (Victoria State Government, Citation2020).

The UK Government recently (January 2021) committed £30 million (CAD $50.4 million) for the installation of Changing Places toilets in all new builds, tourist attractions, parks, and other public places across the UK. Unlike in North America, where Changing Places are few in number, nearly 1200 registered Changing Places toilets (and counting) can be found in England. This means that over 250,000 people in the UK who cannot use standard “accessible” toilets can get out and about and enjoy the daily activities many of us take for granted. They can leave home knowing they will have a place to go. So, why is Canada, for example, lagging behind our UK counterpart in providing these life-changing public facilities, especially when the problem of insufficient toileting facilities for people with severe and/or prolonged disabilities has been identified (Johnson, Citation2019; AccessAbility, Citation2017)?

When a child or adult is placed on a dirty restroom floor to be changed, what does this say about us as a society? That some people deserve to experience the indignity and humiliation of lying in other people’s filth? That “they,” literally, are beneath the neoliberal “us,” too insignificant and unimportant to toilet/be toileted at the same level? What are we saying when someone intentionally dehydrates themselves simply because they want to use the city in ways others do? That there are different levels of humanity, differently valued human bodies to be included in society? Why has it become okay in the general imagination for “disabled”/”othered” bodies to be degraded and harmed in these ways? Why do only certain leaky bodies matter?

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AccessAbility. (2017). Accessible Canada: Creating new federal accessibility legislation. Employment and Social Development Canada.

- Boys, J. (2014). Doing disability differently: An alternative handbook on architecture, dis/ability and designing for everyday life. Routledge.

- Changing Places. (2021). https://www.changing-places.org/

- Cecco, L. (2021, May 24). No-go area: Pandemic highlights Toronto’s lack of public toilets. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/24/canada-toronto-public-toilets-lack

- Goodley, D. (2014). Dis/ability studies: Theorising disablism and ableism. Routledge.

- Johnson, J. (2019). Lack of accessible toilets keeps disabled B.C. girl stuck inside. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/lucy-diaz-accessible-washrooms-1.5197332

- Lowe, L. (2018). No place to go: How public toilets fail our private needs. Coach House Books.

- Magner, L. N. (1992). A history of medicine. Dekker.

- Moore, O. (2021, January 28). Nowhere to go: Lockdowns highlight a lack of public restrooms in Canadian cities. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-nowhere-to-go-lockdowns-highlight-a-lack-of-public-restrooms-in/

- Shildrick, M., & Price, J. (Eds.). (1999). Openings on the body: A critical introduction. In M. Shildrick & J. Price (Eds.), Feminist theory and the body (pp. 1–14). Routledge.

- Titchkosky, T. (2008). “To pee or not to pee?” Ordinary talk about extraordinary exclusions in a university environment. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 33(1), 37–60.

- Victoria State Government. (2020). Changing places design specifications 2020. Victoria State Government. https://changingplaces.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Changing-Places-design-specifications-2020-1.pdf

Beyond Physical Access: The Importance of Thinking about Inclusion

Pippa RogersI am sharing my personal story to illustrate the deep connection between stigma, built environment, and isolation, and provide you with some key thoughts about why we need to think about social, physical and sensory access and inclusion and to connect with community to help make change.

My Story

Inclusion is very important to me as a person of disability. I have faced many obstacles with all aspects of inclusion which has made me more stubborn to have my own voice heard within the community. Throughout the years I have faced many issues around social inclusion, this makes me want to see society evolve with how inclusion is seen by people in the community.

One of the big impacts on social inclusion was social isolation. This affected me socially, through feeling excluded, alone and stuck. I became more anxious in social settings as I felt uncomfortable and out of place. I felt like I lost my sense of belonging within the community. This was one of the biggest struggles I faced with social disconnection.

The struggle I faced due to this was reading the social cues of others because of the fact of being out of the community for such a long time. I found I could not match up what a person was saying to what their body was saying. Maintaining friendships was extremely hard as there was no support in place to do so. I was reliant on my mum and lost a sense of freedom.

I could see that people within the community stigmatised people with a disability. I found that this was one of the main contributing factors towards social exclusion that people with disabilities faced – including myself. Parts of the community seemed to believe that there were restrictions on what people with disabilities could and couldn’t do. I felt upset by the lack of understanding society had when it came to social inclusion. I find still, to this day, parts of the community have these social barriers in place.

As a member of the community, I think that accessibility needs to be improved. It is my observation that physical access is being improved, but I feel it’s important to also consider access in a social, physical and sensory way, because people living within the disability community aren’t all the same. We have different needs and access means different things to different people. Improvements to work towards social, physical and sensory access and inclusion would require research and connecting with others in the community, and people with disabilities having more input in this area.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

How to Make Every Space More Welcoming to Disabled People (Maybe Even Outer Space)

Hannah E. SilverAccessible Space

I recently read a newspaper blurb about the billionaire space race that managed to grate on me more than any other: “The Inspiration4 mission successfully lifted off from Florida, carrying with it an ambition of making spaceflight more accessible to the broader public.”

Thank goodness, I thought to myself. We’ve made everything in terrestrial space accessible to the masses, so we can finally send commoners like me to outer space.

Pardon my cynical tone, but I had just spent hours reviewing survey responses and video clips from interviews I had conducted with disabled people. “I can’t go anywhere without deeply considering my disability,” says a survey respondent. “My biggest struggle? The grocery store,” says another. Various gyms, restaurants, music venues, gay bars, and a florist in a quaint, adaptively reused building make the Can’t Access list. Outer space? Not a mention.Footnote3

But I like to focus on the joys of access, rather than barriers. Tentatively leaving my apartment on a high-pain day, I discover a particularly comfortable corner bench at the nearest coffee shop, where I bask in the sun streaming through the window and greet neighbours without having to push my body into panic mode. After more than a year of lockdowns, most people can relate – it’s fun to go places. I return home with a new buoyancy – from being outdoors, chit-chatting with the barista, watching dogs walk by.

Our public and third placesFootnote4 are sacred. As urban planners and designers, we hold responsibility for shaping not only physical places but also public conversations about future spaces.

In my work, I often ask people to imagine what a radically inclusive future would look and feel like. Rather than making incremental changes to a built environment that has, for hundreds of years, excluded many people by design, I want us to be bold. I encourage people to ask for accessible spaces that are generated from a place of unapologetic, authentic need, unbridled creativity, and collective care.

Maybe surprisingly, our imagined inclusive experiences and spaces seem modest. “My vision for an inclusive future is … I would like to be able to invite all my friends to meet me somewhere for a sandwich,” begins interviewee Sabine (seen in ).

We live in a digital age of wild possibility. Fed a stream of images like The Jetsons, Her, Black Mirror, and NASA landings, I’m as guilty as the next person of associating the word "future" with intergalactic pioneers and shiny, techy gadgets. We are not wrong to think that an accessible future depends on technology, but it is so far from rocket science. (A response from Sabine Rear to ableism in our future visions is seen in ).

Designing for Disabled Joy

Billionaires are unquestioningly out of touch with the public, but there’s also a dissonance between what many able-bodied people think the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has done for disabled people and what it has actually done. Due to inconsistent enforcement and design loopholes, the ADA – bless its heart – maintains a bare minimum of non-discrimination for those whose bodies and spatial needs are considered outside the norm. Many people are underserved.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1 in 4 adults in the US live with some sort of disability.Footnote5 If that seems shocking, then you probably aren’t disabled (or over 65 years of age – when disability stats reach 2 in 5). The visibility of disability is limited by the unfortunate Catch-22 that an inaccessible built environment and culture have made it challenging, if not impossible, for disabled folks to participate in public life.

Further, our go-to conception of a disabled person often involves a wheelchair, a white cane, or hearing aids. Lots of disability is invisible – pain, fatigue, cognitive differences, or mental illness – and therefore unacknowledged. Despite our expanding understanding of neurodiversity, many people whose comfort and access are greatly impacted by their environment are underrepresented in statistics that only offer cut and dried categories of physical disability.

To develop architectural education about inclusive design, I learn from people whose spatial profiles deviate from what critical disability scholar Aimi Hamraie calls the “normate template” (Citation2017). Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, Le Corbusier’s Modulor Man, and a long line of subsequent dimensioned human silhouettes make up this normalized architectural occupant. Approximately 6’ tall (∼180 cm), white, male, able-bodied, with idealized proportions, the normate template is a shortcut that produces design for an unrealistic, static human form – essentially “the body of a mythological being” (Stafford & Volz Citation2016).

No bodies or brains are exactly the same. But all bodies and brains deserve joyful participation! People with cerebral palsy dance.Footnote6 Blind and Deaf people go to comic book readings.Footnote7 People with chronic pain testify to Congress.Footnote8 Disabled people visit museums,Footnote9 parks, the permit counter, and neighborhood association meetings at their local churches and libraries. Though the ADA gave people cursory access to some of these spaces, many more disabled people deserve options that go above and beyond ADA to facilitate their engagement. Joyful access requires that we embrace deviation.

The Digital Bridge

In developing my on-demand course about designing for disabled joy,Footnote10 I was disappointed to find that the most common requests for inclusive spaces simply involve the ADA being applied in full – a bare minimum of safely ramped entryways and accessible toilets. The fact that many restaurants and stores cannot even achieve this points to some high-priority to-dos in code enforcement, as well as a need to support businesses and public spaces that don’t have the resources to comply appropriately.

But before you blast off to a new planet to escape the deeply embedded exclusion of Earth, let’s pump the brakes. The very first step to make spaces more accessible to the 1 billion people worldwide who live with disability? It’s even more modest than meeting ADA: use the Internet as a bridge. “I wish there was a way to know more about venues and if they will be accommodating before I decide if I want to go there or not,” one participant shares. If going somewhere new, another survey respondent says, they will drive there a couple days before and study pictures online to familiarize themselves with how accessible a place might be.

What a whole lot of extra work just to go to lunch. Though Google has recently added wheelchair access information to Maps,Footnote11 this assuages only some mobility needs. We can improve access immensely by simply describing physical spaces online, so people with needs beyond ramps and elevators can decide for themselves whether they would like to visit.

How You Can Make Every Physical Space More Accessible

Wouldn’t it be great if we could all know what to expect before we go out? Here’s how you can contribute.

Somewhere obvious on a Web Content Accessibility Guidelines-compliantFootnote12 website for any space or in-person event, include a page titled "Accessibility." On this page include images of not only the interior of the space, but also the approach from any transportation options – a bus stop, designated parking spots. Include information about the bathroom and furniture options. Note any components of the space that are flexible – can you adjust light or sound settings? Change temperature? Move tables? A floor plan can be especially helpful for people, as predictability is essential. Be sure to describe every image that is included – some people are consuming information via screen-readers, which only interpret text.

The most important piece of the Accessibility page is your receptivity. Disabled people want to go places where they are welcome. Make it obvious by providing a phone number or email form that goes directly to a human so people can ask specific accessibility questions. Train your team to be inviting and knowledgeable about access offerings. Solicit feedback on how you can do better. Understand that though you might get requests you can’t meet, trying to accommodate someone means a lot. Just don’t assume that your idea of a solution meets someone’s stated needs – ask them. Work together. Take time. Access is more of a verb than a noun – it involves constant engagement and evolution. And it involves joy. There is no better feeling than being included.

Next Practices

We are all stewards of some space – at least our own homes or reception areas of small businesses; at most, academic institutions full of lecture halls and offices, or civic spaces intended to serve the entire public. The digital bridge is only a stopgap until we can have fully inclusive buildings, streetscapes, and landscapes. Access that centers disabled joy goes way beyond compliance to prioritize creative, flexible design: imagine places that are attractive regardless of if you can see them, navigable even when your memory slips, and generous to those who need frequent sit-downs, bathroom visits, or sensory breaks. Instead of waiting for this world to be built, I challenge you to take the first small step: take stock of and share a complete image of how people can access your corner of built space.

But don’t stop there. Broad accessibility includes so much more beyond physical space: for disabled people to fully participate, we need a culture of flexibility and deep listening in every workplace, classroom, and public hearing. Only then can we support the growth of planners and designers who mirror the broader population, in abilities, race, and socioeconomic backgrounds. And only then will we plan and design inclusive communities as a default.

In the meantime, ask disabled people what they need. Provide spatial information up front so they don’t have to ask. And remember that access work is love. Remember that there is immense joy to be had and shared by community members when doors finally open to them – some of whom are your beloved elders, future friends, and even yourself. “When disabled people get free, everyone gets free,” writes Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (Citation2018). In our inclusive future, we get free via collaboration and humility in the way we plan, build, and maintain our shared spaces. Fortunately, it’s easy to start now from right where you are, here on Planet Earth.

Figure 1. Sabine describes her “joyful, big dream baseline.”

Image description: A still shot of Sabine being interviewed. Sabine has glasses, brown hair, fair complexion wearing a black t-shirt and a silver chain necklace and is smiling. Full video and transcript can be accessed here: https://youtu.be/zwAo5qlRFTc.

Figure 2. M. Sabine Rear’s comic “I Hate Space” addresses ableism in science fiction.

Image description:. A black and white rectangular comic panel. A text box across the top of the panel reads “how many blind people do you see in space?” And a word balloon below reads “and don’t bother Geordi, he’s exhausted.” The speaker is the artist – a white person with a floppy short haircut wearing a striped shirt, with arms crossed, leaning against a more realistically drawn portrait of the Star Trek character Geordi, played by Levar Burton. Burton is a black man with short cropped hair who wears a thin metal band across his eyes, which is the iconic visual signifier of the character of Geordi. Source: https://believermag.com/i-hate-space/.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Hamraie, A. (2017). Building access: Universal design and the politics of disability. Minnesota University Press.

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Stafford, L., & Volz, K. (2016). Diverse bodies-space politics: Towards a critique of social (in)justice of built environments. TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Programs, 34(Special Issue), 1–17. http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue34/Stafford&Volz.pdf

Ableism in Communicative Planning: An Autistic Perspective

Daniel SalomonMinji ChoBy the early 1990s, planning theorists were interested in developing democratic and participatory forms of the planning process in which all stakeholders could be involved. This idea was combined with Habermas’s communicative action theory, which suggests the precondition for an ideal democratic society, so that communicative planning theory was proposed as a strategy to promote public engagement and redistribute power between public officials and communities (Taylor, Citation1998, pp. 122–124). Although communicative planning theorists have an ideal that everyone’s opinions can be respected in the planning process, some scholars argue that relatively powerless groups can still experience systemic bias in the communicative planning process because the power of speech is strongly affected by how powerful the speaker is (Fainstein, Citation2000; Huxley, Citation2000).

Indeed, people on the autism spectrumFootnote13 have experienced exclusion in the communicative planning process because of the existing power relation, “ableism.” Reading (Citation2018) claims that human communication is based on the “culture of normalcy” which is a phenomenon that creates the illusion that there is a “normal” way and those who do not follow it should acquiesce. This tendency means that people on the autism spectrum, who have neurodivergent cultures are regarded as irrational, deficient, and not “normal” in the context of a conversation where most of the participants are non-autistic people. Furthermore, the persistent stigmatization of people on the autism spectrum has been furthered through neoliberalism, which undervalues interdependence (The Care Collective, Citation2020). Therefore, people on the autism spectrum continue to be marginalized, disenfranchised, underrepresented, exploited, and neglected by layering neoliberalism and ableism.

In the context of planning, many planners with neurotypical perspectives tend to think that neuro-normative professional bodies need to act as representatives for people on the autism spectrum in the communicative planning process. This happens because those of us on the autism spectrum are considered to be lacking the ability to speak for ourselves and to be unable to have our own informed political opinions and voices. Furthermore, even when people on the autism spectrum participate in the communicative planning process, “internal exclusion” (Young, Citation2002, p. 53) can occur. In other words, ableism gives preference to the communication methods of non-autistic peoples, which morally constricts what people on the autism spectrum can say and how we can express ourselves, so we can be heard. Daniel Salomon, the first author of this paper, gives the example of internal exclusion through his experience of participating in the planning process.

As a 41-year old early diagnosed person on the autism spectrum, my neighborhood association has empowered me to give comments to the City of Portland on several different issues which impact our neighborhood. I have received help from my neighborhood association on how to get my testimony into the right form to be heard. I have not had any trouble receiving ADA accommodations when I have testified before the city council; however, part of getting into the “right form” means that I have to fit into the constraints of an archaic setup that does not address values that do not fit into neurotypical normalcy. This makes it difficult for me to explain my real concerns beyond my self-interest.

His experience demonstrates that the pressures to employ privileged communication like language and forms, make people on the autism spectrum try to fit the voice into the rigid constraints of an archaic planning process, status quo, and legalese. As such, the current communicative planning process may not only create the inequity of unnecessary stress, fatigue, trauma, and emotional labor for people who already have sensitive mind-bodies but such narrow forms of communication processes cases also often lead to feelings of intimidation and discouragement, which often leads to withdrawal and complacency (Davidson, Citation2008; Grinker, Citation2021; Leadbitter et al., Citation2021). The status quo also fragments the autistic narrative, meaning that the autistic narrative, which includes autistic needs and an alternative vision of the good, identity, and disability culture, still does not get heard outside of specific accessibility issues (Grinker, Citation2021; Mireles, Citation2020).

Those of us on the autism spectrum increasingly see ourselves as members of an identity group, a part of humanity since the beginning, who have our own histories, cultures, and languages and are a “historically underrepresented population” needing belonging, justice, and dignity. Therefore, it is necessary for the planning field to devise a way that all individuals on the autism spectrum can engage in the communicative planning processes. This should be regardless of ability or diagnosis, and regardless of identities such as race, gender, and cultural backgrounds. By recognizing neurodivergent cultures, it is necessary to transform communicative planning theory and practices, rather than finding a way to make neurodivergent people assimilate into the existing planning process that is constructed by people with neurotypical perspectives.

In practicality, planners could disrupt this ableism in communicative planning by letting individuals on the autism spectrum speak from our hearts without censorship or scripting about our “life-world” through our preferred communication styles and skills, welcoming our creativity and innovation. For example, it is necessary to reconsider whether face-to-face communication based on speech and eye contact, which is emphasized in communicative planning theory and practices, is the most appropriate method for all neurotypes (Hillary, Citation2020). Indeed, Davidson (Citation2008) suggests that communication through the Internet can be an appropriate means for interaction with people on the autism spectrum compared to face-to-face communication. Furthermore, considering that interaction between people on the autism spectrum is effective, while people on the autism spectrum have difficulty in communicating with non-autistic people (Crompton et al., Citation2020), neurotypical planners should recognize that it is not that people on the autism spectrum lack the skills to interact, but that the communicative planning process is still not structured in a way that is appropriate for everyone.

We only provide an introduction to how to revise theories of communicative planning to address and avoid ableism; however, this topic must continue to be developed in planning theory and practices. In order to emphasize the importance of this topic, we would like to introduce the testimony of a person on the autism spectrum. She started expressing her opinions using an Augmentative and Alternative Communication aid, one of the alternative communication methods for people on the autism spectrum, at the age of thirteen. Then, she recalled a time when she was not able to communicate as follows:

I was sadly assumed to be mentally retarded. No one made the distinction in real life if I was labeled mentally retarded or was mentally retarded. (...) When I was not able to communicate, I was not relating to the world. (...) Actually, I was a non-person. (Rubin et al., Citation2001, p.418)

Her testimony illuminates that, for people on the autism spectrum, to be able to communicate with others is to recover our dehumanized subjectivity, to acquire dignity for ourselves, and to restore our relationship with communities, society, and the earth. In other words, the neurodiversity movement in communicative planning can save autistic lives and protect autistic human dignity beyond the accessibility issue. We further believe that escaping the ableism embedded in communicative planning theory and practices can be the basis for achieving the ultimate goal of communicative planning, which is overcoming the unequal distribution of power through authentic dialogue.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Crompton, C. J., Ropar, D., Evans-Williams, C. V., Flynn, E. G., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 24(7), 1704–1712.

- Davidson, J. (2008). Autistic culture online: Virtual communication and cultural expression on the spectrum. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(7), 791–806.

- Fainstein, S. S. (2000). New directions in planning theory. Urban Affairs Review, 35(4), 451–478.

- Grinker, R. R. (2021). Nobody’s normal: How culture created the stigma of mental illness. WW Norton & Company.

- Hillary, A. (2020). Neurodiversity and cross-cultural communication. In H. B. Rosqvist, N. Chown, & A. Stenning (Eds.), Neurodiversity studies: A new critical paradigm (pp. 91–107). Routledge.

- Huxley, M. (2000). The limits to communicative planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 19(4), 369–377.

- Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K. L., Ellis, C., & Dekker, M. (2021). Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–7.

- Mireles, D. (2020). Dis/rupting and Dis/mantling racism and ableism in higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of California]. UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zf0x9fv

- Reading, A. (2018). Neurodiversity and communication ethics: How images of autism trouble communication ethics in the globital age. Cultural Studies Review, 24(2), 113–129.

- Rubin, S., Biklen, D., Kasa-Hendrickson, C., Kluth, P., Cardinal, D. N., & Broderick, A. (2001). Independence, participation, and the meaning of intellectual ability. Disability & Society, 16(3), 415–429.

- Taylor, N. (1998). Urban planning theory since 1945. Sage Publications.

- The Care Collective. (2020). The care manifesto: The politics of interdependence. Verso Books.

- Young, I. M. (2002). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press.

Hindsight isn’t Necessarily 20/20: Reflections on Ableism in Planning Education and Practice

Gail DubrowDedicated to Barbara Faye Waxman Fidducia (1955–2001)

Do I want to be a psychologist who listens to disabled people tell me of their despair from loneliness? Or do I want to arouse the senses of disabled people and policymakers into feeling the urgency to transform social policy, which would fulfil our intrinsic rights to cultivate love, form families, and secure our privacy?

Barbara Waxman Fiduccia (Citation2000, p. 167)

So many educated people with disabilities are channeled into helping professions in counseling or advocacy as opposed to urban planning; fields split at the root in the gendering of social work and city planning at the dawn of the twentieth century. For that reason, Barbara Faye Waxman Fiduccia’s decision to study urban planning at graduate level at UCLA in the mid-1980s, following on the heels of alumni Don Parson, author of Making a Better World (Citation2005), signaled a remarkable decision to press for systemic change over ameliorating the personal consequences of oppressive but normalized social constructs and practices.

A mother of the disability and sexual advocacy movements, Barbara was the first person to raise my awareness of the inseparability of disability from every planning decision. I studied for a doctorate at UCLA’s Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning (GSAUP) at the same time Barbara was a master’s student. Her feminism, anti-racist politics, and most importantly, her vocal position on disability rights fused personal experience with a keen analysis of barriers in the built environment and landscape. Given the pervasive ableism in planning thought and practice then and now, for all practical purposes, these barriers were invisible. For example, UCLA’s recognized father of planning theory, John Friedmann, found no place for disability theory in his decidedly white male pantheon of intellectuals, Planning in the Public Domain (Citation1987). Feminist thought meets anti-racist politics fused with Crip theory? Not exactly on the Progressive planning agenda in the mid-1980s, no matter how inspiring the radical theories that emerged out of that hotbed of activist planning in Los Angeles.

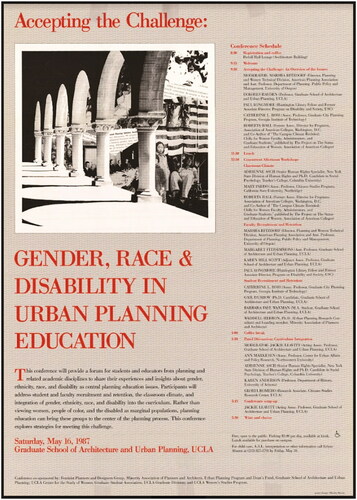

I was moved by what Barbara shared with the two groups of graduate student activists who exercised outsized agency in shaping our own education and redefining the principles that would guide our future careers in and out of planning. We were buoyed by the radicalism of GSAUPs extraordinarily and intentionally diverse faculty: Dolores Hayden, Jacqueline Leavitt, Leo Estrada, Martin Wachs, the list goes on. ( illustrates the kind of activities and scholars working at UCLA)

Working closely with Dolores Hayden on the Power of Place (Citation1995), we reimagined historic preservation to include the labor of all the people who built Los Angeles. Our emphasis on highlighting places that illuminated histories at the intersections of gender, race, and class, added momentum to the movement to preserve places associated with the diversity of the American people. As many sectors of the preservation movement came to take up the work through historic site surveys and theme studies, including the National Park Service, it is in hindsight striking that our best intentions to be inclusive were so strikingly absent of attention to disability as a subject. In recent years, single issue identity-based studies have drawn attention to intersectional identities, as highlighted by Megan Springate in the National Park Service study, LGBTQ America (Citation2016).

To the extent that my friendship and cabal membership led me to walk beside Barbara as she rolled, I got to observe some things closely. So many decades later, I vividly recall how she navigated the spaces of Perloff Hall in her power chair, whipping out of the library into the common areas where students gathered informally. She was way more nimble than me. In retrospect, as someone whose identity was then framed by socialist-feminist politics, precocious advocacy for racial justice in middle school, and the material consequences of coming out in high school as a lesbian in 1970, I felt empathy for, but no sense of personal identification with, people with disabilities.

In hindsight, however, and with deepest apologies to Barbara for not recognizing her genius, I now acknowledge my own long lag in integrating that experience and knowledge into three decades of work intended to make the histories of underrepresented groups metaphorically and materially present at historic sites and buildings. My conceptual blindness, and frankly the categorical omissions within my exceptionally progressive planning education, and subsequent decades of seemingly innovative practice, were only called into question by developing a visual impairment later in life. Diabetes can lead to diabetic retinopathy. My visual challenges stem from this metabolic disorder, which runs like a deep river through my own family history. Yet, the challenges are complicated by working in the field of planning that presumes and privileges visual acuity. I offer these reflections as a cautionary tale for planners like me who are committed to advancing social justice but have yet to educate themselves about disability justice.

At best, humans are only temporarily able-bodied through the life course. It was only when personal and professional life as I knew it, as a temporarily able-bodied person, imploded that most of my well-intentioned work to advance social justice revealed itself to be absent of attention to the diversity of human abilities. During my career in historic preservation, I have primarily worked to preserve places significant in the history of women, Japanese Americans, and LGBTQ heritage (Dubrow and Goodman, Citation2003). These efforts highlight the intentional development of intersectional, participatory planning methods, as Donna Graves and I addressed in “Taking Intersectionality Seriously” (Graves & Dubrow, Citation2019). Indeed, most of my past projects, even those specifically designed to be “accessible to public audiences,” are now barely accessible to me. My book with Donna Graves, Sento at Sixth and Main (Dubrow et al., Citation2002), beautifully styled with minute font, was unreadable to anyone who strained to see, including some of the elderly Japanese Americans who had shared their stories about places significant in their heritage. Nor had I considered whether people with disabilities were reflected in the histories we worked so hard to make visible through dozens of National Historic Landmark nominations. Beyond ADA-compliant access to historic buildings and landscapes, disability had no place as a consideration or a formal category of analysis in my portfolio of past projects.

It is urgent that our peers in planning education and practice shed the misconception that only a narrow class of people with a proscribed cluster of physical, cognitive, and/or psychological disabilities, comprise the interest group for design sensitive to variations in human abilities. Simultaneously, planners need to be competent at working with and in the interests of those most disadvantaged by ableist assumptions baked into the urban landscape. Our collective failure to recognize, much less remove, ubiquitous barriers indicts city and regional planners as complicit in reproducing and maintaining a severely disadvantaged class of people due to “environmental ableism” on a par with patterns of environmental racism – compounded for BIPOC and queer people with disabilities. Grappling with our own ableism is required to plan effectively in the public interest.

Long before I was diagnosed with visual impairment, I was at least conceptually legally blind to the ableist foundations of even the most progressive planning theories and practices. This humbling insight has brought into sharp relief the intellectual and practical poverty of our own field of study, in offering a clear understanding of the meanings we ascribe to human differences and their consequences for reproducing inequitable power relations. Not unlike the lags in understanding social relations of gender, race, and sexuality, as they are inscribed into and perpetuated by the normative assumptions that underlie the ways we plan and design the built environment, we have a steep road to climb in understanding disability in critical perspective.

Putting issues of human ability and disability into the center of our thinking offers a helpful corrective to urban visions pitched toward the most able-bodied, affluent, desirable, employable, autonomous, privileged individuals. As I have found my way to the few places of refuge that center the needs and priorities of disabled people in their own policies and practices, I find myself significantly less disabled than in most spaces shaped by professional planners. These rare and precious places of refuge from ableist assumptions are a sort of experimental imagined future for me. In 2020, my small team, including Laura Leppink and Sarah Pawlicki, founded REPAIR (Rethinking Equity in Place-based Activism, Interpretation, and Renewal: Disability Heritage Collective): Disability Heritage Collective. We have sought to establish a non-hierarchical group of learners to explore how we might integrate insights from scholarship in U.S. disability history with activist-inspired principles and practices to accelerate disability justice at historic places. Every social movement requires cultural initiatives that center the perspectives and forms of cultural expression directly associated with groups denied their full humanity. Through our exploration, REPAIR has centered disability justice as a method to understand better how dismantling ableism and addressing disability might transform fields such as urban planning, design, and heritage conservation.

Barbara Waxman Fiduccia is no longer an isolated figure asserting the importance of dealing with disability. Today, there is an entire field of scholarship on disability history, theory, methods, and best practices for planners and designers whose commitment to social justice extends to tackling the ableism baked into our thinking. As we frame our theoretical stances as planners, confident that feminist and BIPOC scholars have laid a foundation for our own initiatives, let us pause to remember that we will only be walking, limping, and rolling on solid ground when we fully integrate the experiences and perspectives of people with disabilities into our definition of justice.

Figure 1. Poster from May 1987 conference co-sponsored by Feminist Planners and Designers and the Minority Association of Planners and Architects.

Image description: A flyer for the conference schedule includes a photo collage of a walkway with arches, a woman in a wheelchair, people of color, document fragments and a flag. The conference name is prominent on the poster “Accepting the Challenge: Gender, Race & Disability in Urban Planning Education,” UCLA.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Dubrow, G. L., & Goodman, J. B. (2003). Restoring women’s history through historic preservation. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dubrow, G. L., & Graves, D., & Cheng, K. (2002). Sento at sixth and main: Preserving landmarks of Japanese American heritage. Seattle Arts Commission.

- Fiduccia, B. W. (2000). Current issues in sexuality and the disability movement. Sexuality and Disability, 18(3), 167–174.

- Friedmann, J. (1987). Planning in the public domain: From knowledge to action. Princeton University Press.

- Graves, D., & Dubrow, G. (2019). Taking intersectionality seriously: Learning from LGBTQ heritage initiatives for historic preservation. The Public Historian, 41(2), 290–316.

- Hayden, D. (1995). The power of place: Urban landscapes as public history. MIT Press.

- Parson, D. C. (2005). Making a better world: Public housing, the red scare, and the direction of modern Los Angeles. University of Minnesota Press.

- Springate, M. (2016). LGBTQ heritage theme study. National Park Service.

Disability Justice Meets Climate Justice