Abstract

The quest to deliver sustainable development has led to a search for ways to engage all stakeholders in this collective endeavour. Currently, local planners across England and elsewhere use independent design review panels to help raise the design quality of new developments. This paper examines the extent to which such panels can instill the need to adhere to sustainable development principles. We focus on the Cambridgeshire Quality Panel, which has framed its review process around sustainable development principles, named the “4 Cs”: community, connectivity, climate, and character. Situating the panel’s work within a design governance framework, we scrutinise the value and limitations of this particular governance tool. We conclude that local planners’ ability to take forward the panel’s recommendations on delivering new developments to high sustainability standards remains problematic, compromised by national priorities and market decisions.

Introduction

The quest to deliver sustainable development, which is to meet present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, has led to a search for effective governance structures to fully engage stakeholders in this collective endeavour (WCED Citation1987). This paper examines the extent to which one particular governance structure, already utilised within English local planning authorities – independent design review panels – is able to foster, and achieve, this need to adhere to sustainable development principles. For the purposes of our paper here, the different stakeholders include all parties with a stake in shaping places for the better (Carmona, Citation2016, p. 726), notably local planning authorities, elected councillors, architects, urban designers and developers.

Design reviews have been defined by Scheer (Citation1994, p. 2) as “the process by which private and public development proposals receive independent criticism under the sponsorship of the local government unit.” The use of design review panels is common in many jurisdictions, with a large variety of review processes in existence, typically administered by local governments at the neighbourhood or city-wide levels (Kim & Forester, Citation2012; Punter, Citation2011; Scheer, Citation1994). In England, the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) recommends (but does not require) that local authorities establish independent expert design review panels to instil high design standards within development proposals (Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government – MHCLG Citation2021).Footnote1

Despite the lack of formalised recognition in statutory planning systems, independent design reviews have been valued for strengthening local planning authorities’ hand in negotiations with developers, providing them with expert arguments and evidence to pursue design improvements (Punter, Citation2011). Moreover, there is growing international interest in using independent expert design panels to broaden discussion away from matters of architectural details that overwhelmingly dominate development approval processes (Carmona, Citation2019; Farhat, Citation2021). Given their independence and high level of discretion, there is scope for design review panels to develop their own distinctive approaches to planning practices and raise the level of understanding generally around sustainability considerations (White, Citation2016). Although the advice is not binding, an opportunity exists for design review panels to provide guidance and support to local planning authorities, so that new developments are built to high sustainability standards.

The focus of this paper is on the Cambridgeshire Quality Panel (CQP), and the structuring of its review process around a set of overarching guiding principles (the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter) that relate explicitly to sustainable development matters. The Charter was initiated by the not-for-profit organisation Cambridgeshire Horizons, one of the delivery vehicles established by the then Labour Government and tasked with coordinating Cambridgeshire’s growth strategy, as embodied in the 2003 Cambridgeshire Structure Plan, and adopted Local Plans (Cambridgeshire County Council (CCC), Citation2003; CCC Citation2018; SCDC Citation2018). The Charter was endorsed by the then Minister for East of England in 2008, with the aim of establishing the principles that different stakeholders could agree upon, before development proposals of strategic importance were approved. Following the abolition of Cambridgeshire Horizons in 2010, the CQP came under the auspices of Cambridgeshire County Council (the tier of government operating above the local district level). Its remit is to provide independent advice on major development proposals (including new settlements and urban extension sites) submitted to the relevant Cambridgeshire local planning authorities, with Cambridge City Council and South Cambridgeshire District Council the subject of this paper.

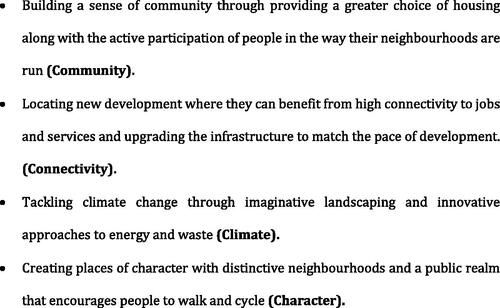

The Cambridge Quality Charter adopts a comprehensive approach to place-making, with the view to achieving long-lasting sustainable communities (UN, 2020). The principles adopted in the Charter are summarised as the “4 Cs”: community (which includes creating mixed income communities), connectivity (which is about connecting new development to services and jobs), climate (in terms of mitigating waste and energy usage), and character (creating places of character, with distinctive public realms) (see ).

In undertaking the investigation here, this paper draws on the design governance framework denoted by Carmona (Citation2016) to discern the value of design review panels against the limitations of this governance tool, which we argue, forms part of the wider “problematics of design governance” (Carmona, Citation2016, p. 714). To assess the value of the CQP, the paper first examines how its review process is distinct from conventional design review panels in England – by framing its review process around the “4 Cs.” It then considers the value of the CQP approach in raising stakeholders’ awareness around sustainability considerations. Finally, the paper considers the limitations of the CQP, focusing on its constrained capacity, to date, to enact change. The paper concludes that ability of local authorities to take forward panel recommendations and make developers adhere to sustainability principles is ultimately problematic, compromised by national priorities and market decisions.

Sustainable Development and the Role of Urban Design in its Delivery

A commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals means a clear obligation to plan and implement actions for more sustainable futures (UN Citation2020). The perception that planners have an intrinsic ability to deliver (sustainable) development that aligns with these goals is not new (Berke, Citation2016; Campbell, Citation2016). Given that the climate emergency has increased locally and globally, Carmona contends that the “notions of sustainability have moved up the public and political agenda and have led to a renewed questioning and refocusing of most professional remits” (2009, p. 49). In the United Kingdom (UK), New Labour’s election victory in 1997 heralded the promise of a new era of spatial planning, with increased emphasis on the role of planners in delivering sustainable communities (Raco, Citation2007). Moreover, the urban design discipline has for some while been expected to play a key role in creating sustainable development and communities, able to address all three vectors of sustainability – economic, social, and environmental (Ritchie & Thomas, Citation2009). However, as Carmona (Citation2009) also surmises, “the reality is that even if such notions have existed in theory, more often than not they are largely absent in practice. Instead, they are compromised by the need to deliver outcomes largely through market processes, and by public political agendas that prioritise economic growth” (2009, p. 49).

The result, for Carmona (Citation2009, p. 50) is that the urban design process often ends in a “token engagement with sustainability, rather than a serious attempt to reflect a more holistic sustainable urban design agenda.” Australian urban designer, Lang (Citation1994, p. 15) equally suggests that the responsibility for most privately commissioned architects and urban designers lies with the client and less with the environment and the local community. Macdonald (Citation2016, p. 44) likewise claims, within the context of the United States, that urban designers working for private sector clients often “do not have the resources or budget scope to investigate all aspects of local particulars related to sustainable urban form.”

Nonetheless, design-led principles have the potential to deliver sustainable futures, if adopted as a strategic priority for public sector policy. The Vancouver Declaration, signed by several planning bodies at the World Planners Congress in 2006, for instance, stresses that “there can be no sustainable development without sustainable urbanization and no sustainable urbanization without effective planning. Political will and investment are required for effective planning” (cited in Global Planners Network, Citation2018, p. 1). Yet, whilst there is international agreement that sustainable development is “guided by a political will, and ethical and ecological imperatives” (Glavič & Lukman, Citation2007, p. 1884), difficulties remain in raising a level of urgency within stakeholders to act upon their respective obligations, and elevate new developments beyond current practice, and towards greater sustainable outcomes (White, Citation2016).

Assessing the Potential Contribution of Design Review Panels

The initial concept of a design review process within urban development was founded in the Netherlands, with Belgium and Germany following suit in embracing the Dutch model (Punter, Citation2011). Design reviews have been adopted in numerous jurisdictions thereafter, with independent expert members providing recommendations on ways to achieve higher standards of urban design (Punter, Citation2003; Scheer, Citation1994). For Carmona (Citation2016, p. 705), these non-regulatory “informal” tools are of value within overall design governance, and which he defines as “the process of state-sanctioned intervention in the means and processes of designing the built environment in order to shape both processes and outcomes in a defined public interest.”

Design governance represents all the diverse processes through which planning authorities engage with private interests to enhance the quality of place, and, for the purposes of his theorising, Carmona (Citation2016) also includes the full range of instruments or tools available to planning authorities charged with such processes. Whilst formal tools are sanctioned by legislation, the design review process often occurs without specific legislative weight and at the discretion of local authorities. Nevertheless, they do still form an essential part of the decision-making environment, thus assisting the intention of design governance to achieve “‘better design’ than would otherwise be achieved without” (Carmona, Citation2016, p. 720).

Despite non-mandatory compliance, independent peer design reviews also provide an opportunity to promote capacity building and shape development culture, raising the overall standard of debate around place-making (Punter, Citation2003, Citation2011). Kim and Forester (Citation2012) summarise the potential value of expert panels in terms of their ability to: promote mutual learning between different stakeholders, act simultaneously as “educators, therapists, and ritual conveners” (p. 239), facilitate stakeholder deliberations, and build constructive relationships in the pursuit of higher design standards.

Distinct approaches to design review panels, as adopted within different cities, have been showcased in numerous studies. Notably, Punter (Citation2003) heralds Vancouver’s approach as “enlightened” (p. 429). Dawson and Higgins (Citation2009) examine Edinburgh’s “pioneering role in proactively promoting the design agenda” (p. 107). White (Citation2016) highlights how the panel adopted in the Toronto Waterfront revitalisation has an “influence on decisions more through moral suasion than legal authority” (p. 27). Farhat (Citation2019, Citation2021) stresses how design review has informed the broader civic discourse on place-making in Seattle and Portland, respectively.

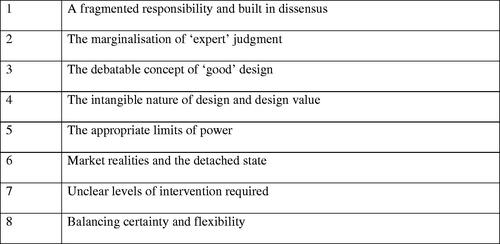

Although these examples illustrate how independent expert panels can and do provide value to design governance in different jurisdictions, there are also limitations in what they can achieve. Despite well intended motivations for planning authorities to engage in and establish design governance arrangements, the design review process, as with urban design generally, can be inherently problematic; not the least because “at its heart [is] the idea of complex shared responsibilities” (Carmona, Citation2016, p. 726). Carmona (Citation2016) cites eight core governance “problematics,” which are summarised in . For Carmona (Citation2016), ultimately, “balancing certainty and consistency with flexibility is the key challenge in all design governance” (p. 714).

Figure 1. Eight core design governance problematics (source: adapted from Carmona, Citation2016, p. 714).

These “problematics” form the basis of the criticisms that design review panels have received internationally. Whilst the Netherlands set the precedent in establishing panel reviews, the Dutch exemplar fell victim to criticisms of lack of transparency and detachment from planning practices (Punter, Citation2011). In the US, despite their proliferation in different cities, expert panels have been criticised for basing decisions on subjective, “vague concepts” (Punter, Citation2011, p. 114), and the superiority of such panels in improving design outcomes has been called into question by commentators favouring the clear, measurable dimensional criteria of traditional administrative form-based codes (Farhat, Citation2019, Citation2021). The work of design review panels in Canadian cities has faced similar criticisms, with notions of design considered debatable and subjective leading to arbitrary decision making. There remains no mandatory compliance to adopt a review panel’s recommendations in Canada (White, Citation2016). In Scotland, whilst it is acknowledged that design review panels offer access to expertise that otherwise would not be available in-house, the panels’ role remains solely advisory (Richardson & White, Citation2021).

Similarly in England, there is no legal basis for independent expert review, and this voluntary advisory status precludes any requirement for stakeholders to heed to a panel’s advice. Moreover, the Commission for Architecture and Built Environment (CABE), tasked by the UK Government in 1999 with establishing design-led principles and guidance across England, faced extensive criticism, with commentators arguing that the CABE was “unaccountable, lacked transparency, cliquish, groupism and stylism” (cited in Punter, Citation2011, p. 185). Government funding was withdrawn in 2011. The CABE subsequently merged with the (UK) Design Council, a move which reduced its effectiveness and influence on raising the standard of design within developments across England (Carmona et al., Citation2018).

Nonetheless, and despite these challenges, England’s NPPF maintains that local planning authorities should ensure that they have access to, and make appropriate use of, tools and processes for assessing and improving the design of development, including, design review arrangements (MHCLG, 2021, para.129). Whilst the aim of design review panels is to “raise the bar on design quality of new developments” (Platt, Citation2015, p. 1), the approach adopted varies by local authority (Design Council, Citation2013, Citation2018). Previous studies examining conventional design review processes in England note their limitations for being reliant on unpaid volunteers from private and public sector professions, with no local community representatives. Their remit primarily concentrates on local aesthetics and narrowly constructed guidelines on site planning. The panels invariably examine single projects, usually without concern for their place in the urban setting or impact on the overall built or natural environment within the given local authority (Carmona, Citation2016; Durmaz-Drinkwater & Platt, Citation2019; Punter, Citation2011). Moreover, scant attention has been given to how English design review panels could be of value in instilling greater awareness among stakeholders around broader sustainability considerations and their role in promoting design-led sustainable development principles.

Various international studies, however, have highlighted the contributions that design panels in different cities have made in raising awareness around sustainability issues, notably the Vancouver design panel’s “comprehensive commitment to environmental quality” (Punter, Citation2003, p. 429), the call by Toronto’s design experts for the review process to “incorporate progressive themes such as sustainability” (Farhat, Citation2019, p. 107, and White, Citation2016), and the “championing” by the Design Commission for Wales for “high standards of sustainability in Wales” (Punter, Citation2019, p. 605). Yet, these authors provide little detail on how design-led sustainability principles have been incorporated into each locality’s specific design review processes, nor have they assessed the limited capacity of those review panels to enact positive sustainable outcomes. Our study seeks to address this omission in reference to the particular design review process adopted in Cambridgeshire.

Research Methods

The Case Study

The not-for-profit organisation, Cambridgeshire Horizons, was established in 2006 under the auspices of the then Labour Government. It commissioned the consultant, Urbanism and Environmental Design Ltd (URBED) to co-produce guiding design principles for Cambridgeshire growth areas, incorporating extensive consultation with key stakeholders, locally, nationally, and internationally. The resultant ”Cambridgeshire Quality Charter for Growth” was published in 2008 and adopted by the CQP, once formally established in 2010 (Cambridgeshire Horizons, Citation2008). The Charter's design-led sustainable development principles (in short, the “4 Cs”) have been used as point of reference ever since. When the new UK Government abolished Cambridgeshire Horizons in 2010, responsibility for the CQP shifted to Cambridgeshire County Council.

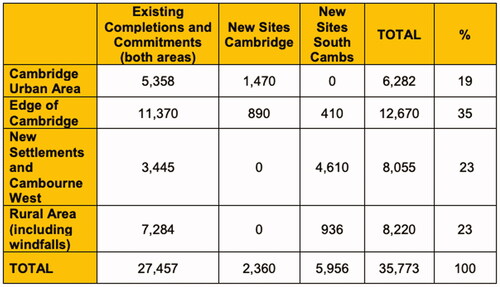

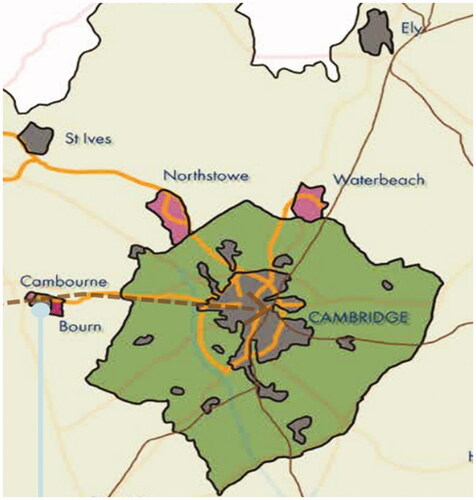

Cambridgeshire has one of the fastest house building rates in the UK. Large-scale new settlements and urban extension developments are also being built over long periods of time (see and ). Both processes point to the paramount importance of an on-going consistency in good quality design, and in line with the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter’s agreed sustainability principles (Cambridgeshire County Council (CCC), Citation2003; CCC Citation2018; SCDC Citation2018).

Figure 2. Housing completions and commitments in Cambridge City and South Cambridgeshire, 2011–2031 (source: CCC Citation2018; SCDC 2018).

Figure 3. Map of Cambridge and South Cambridgeshire, showing location of new developments of strategic importance (source: SCDC 2018).

The remit of the CQP includes ensuring that the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter is communicated to respective stakeholders before major development proposals are approved by both Cambridge City and South Cambridgeshire District councils; and that, as far as possible, equal weight is given to the values of all “4 Cs” when coming to their independent expert advice. The “4 Cs,” as defined in the Charter are shown in .

Figure 4. The Cambridgeshire Quality Charter’s “4 Cs” (as defined in Cambridgeshire Horizons, Citation2008, p. 4).

Research Design

Semi-structured, open-ended interviews were conducted with twenty six persons closely connected to the work of the CQP: (i) ten of the seventeen members of the CQP itself (with the Chair interviewed more than once to gain a deeper understanding) (ii) six planning officers (including the panel secretariat from the County Council), urban design and conservation managers and principal urban designers from both councils, and (iii) ten developers, architects and urban designers who have been directly involved in the CQP process. Given that most of the panel members sit on other design review panels across England, and the different developers, architects, and urban designers interviewed have undergone similar design reviews in different localities, the respondents were able to compare how the CQP’s review process is distinct from other, more conventional, design review panels – given its framing of the review process around the “4 Cs.” As such they were able to provide useful and informative advice on the operation of the CQP as an unusual or “deviant” case (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 230), and on how its processes and practices might be “especially good” (p. 230), and more effective than the norm.

The objectives of the interviews were three-fold:

To examine how the CQP differs from conventional review panels, and gauge, from the different perspectives of the interviewees, the value obtained from centring the CQP review process around the “3 Cs,”

To ascertain how the CQP has raised stakeholders’ awareness around sustainability considerations, not just in Cambridgeshire but also elsewhere, including nationally, and,

To consider the limitations of the CQP within the current design governance system that it operates within.

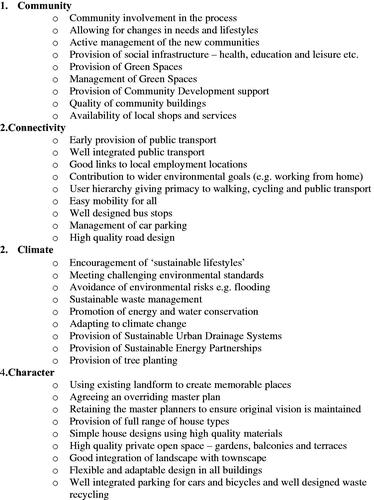

Several additional sources of evidence have been used to ensure the robustness of our findings. Minutes from the CQP meetings and the CQP annual reports were used to crosscheck the validity of the interview responses. These sources were also used to analyse the CQP’s workings between 2011 and 2020 and to trace, longitudinally, both the “4 Cs” and any broader sustainable development principles that the CQP focussed on in its deliberations (see ).

Figure 5. Checklist of criteria that applicants need to consider under the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter’s “4 Cs” (source: Cambridgeshire Horizons, Citation2008).

Whilst there are acknowledged, inherent difficulties in generalising from a single case study, triangulation of data from such different sources enhances validity and reliability of the case selection. In this instance the chosen case provides both an unusual and a “critical case” worthy of exploration (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 233). If, for instance, it is found that the Quality Charter canvassed here, with its focus on the “4 Cs,” fails to instil in stakeholders the need to consider sustainable development principles, then the “logical deduction” (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 203) is that it would be hard to see how those outcomes could be achieved through more conventional design review processes. On the other hand, if the CQP can achieve what it has set out to do (within the boundaries in which it operates), then there are opportunities for its process, as framed under the “4 Cs,” to become, as Gerring (Citation2007, p. 10) denotes, “an influential case,” able to play a key role in establishing new processes and practices across England.

Research Findings

The CQP Review Process

The core principles of the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter (the “4 Cs”: community, connectivity, climate, and character) were established back in 2008. More than a decade later, and despite the abolition of Cambridgeshire Horizons in 2010, the Charter is still considered today as the CQP’s “Holy Bible,” as one of the local authority officers called it. The CQP members and local authority officers agreed that the Charter represented a key component in raising the general expectation for high urban quality and place making, in line with the Charter’s agreed sustainable development principles. As one of the planning officers advised, the Charter was established because:

We wanted new developments, particularly the ones at Cambridge’s urban extension sites and new settlements around the city, to be really good and we wanted to be inspired. Design review is a typical process, but we did not want a conventional panel. We wanted it to be broader than just urban design, which gave rise to the “4 Cs.” The real idea was having a panel with independence and clout challenging both local authorities and developers to do better and to be more ambitious.

The CQP meets on average monthly under the Chair of a leading architect and comprises seventeen paid members. The CQP is self-funded, with panel member fees (£400 per day plus travel expenses) and local authority costs paid by developers when submitting applications for review. The CQP members are competitively recruited to ensure the maximum range of expertise in relation to the “4 Cs.” As of 2021, the members comprise four project managers and researchers experienced in “community” matters, three transport engineers (with related master planning expertise) experienced in “connectivity” issues, two climate specialists with expertise in sustainability, and two landscape architects and four architects with expertise in urban design and “character” matters. Five members live in Cambridgeshire and thus possess local knowledge, helping to ensure that development proposals are consistent with existing neighbourhoods. The range of expertise on the CQP, and particularly the recruitment of climate specialists, differs from normal practice. As one panel member, who like others, sits on one or more panels across England, argued:

The CQP is different and more effective than other panels in England. Most panels do not have CQP’s spread of skills. Some panels don’t even have a landscape architect present. They rarely have a climate specialist. It is slowly changing. I sit on two other panels as an architect, yet I was shocked to find that I am named on [one organisation’s] website as a climate specialist. At CQP, we bring these skillsets in and recruit the best. We have considerable experience here.

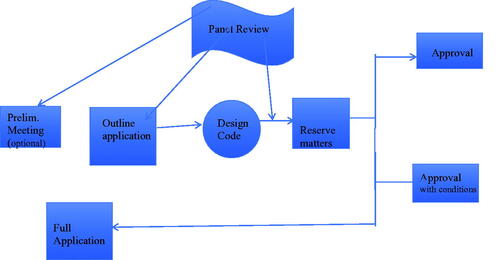

Between 2010 and 2020, the CQP reviewed 183 proposals, sometimes reviewing the same proposal twice, and preferably as early as possible to have a meaningful effect. Like many panel review processes in England, the aim is to schedule the first meeting with applicants before the initial planning application (Outline Planning Application). However, the CQP is also keen to review the scheme again prior to subsequent stages (the Design Code, and Reserved Matters stages) (see ). By dedicating time to this engagement process, the CQP builds up a collective knowledge base, providing local authority officers with support and reassurance “to boost their legitimacy, because it allows them to demand more and stops developers ruining new developments with ill-conceived plans” (CQP member). As one planning officer added: “the calibre of the people on the panel gives it the weight it needs,” and even though the role of the CQP is solely advisory, “it can still influence the process and development outcome at (Cambridgeshire and South Cambridgeshire’s) strategic sites.” This influence is of critical importance as the two Councils undertake their ambitious growth plans.

Moreover, unlike conventional review processes, the applicant is required to prepare a presentation to the CQP and planning officers that makes clear reference to each of the Charter’s “4 Cs” This then forces them to structure their 60-minute presentations differently to what might otherwise be the case. highlights the CQP’s checklist, according to each of the Charter’s “4 Cs” that the applicants must consider. Presentations are followed by a 60-minute review discussion with the developer, and then a closed session with the CQP and planning officers solely present. As the review process is only advisory, there is no reason for voting, and panellists can express difference of opinions. However, as a panel member remarked “this (i.e. differing views) is rare.”

After the meeting takes place, Cambridgeshire County Council is provided with written feedback from local authority officers and the Chair of the panel on any improvements to the scheme in line with each of the “4 Cs.” It is then the role of the planning officers to negotiate with the developer at the Reserved Matters Stage and to monitor whether suggestions have been taken on board in this meeting and thereafter. The final decision in granting planning permission is taken by the local planning committee (consisting of locally elected councillors), using both the planning officers’ recommendation of approval or refusal and the panel’s review as reassurance. If the developer does not show any sign of implementing the panel’s recommendations, it is likely that the local councillors could take this as a reason to refuse planning permission.

Perspectives on the Value of the “4 Cs”

The interviewees held differing views on the merits of framing the CQP’s review around the “4 Cs” and its effectiveness in instilling sustainable development principles. For the panellists, there was consensus that the review process was less drawn into matters of architectural details and narrowly constructed aesthetics, and which has been a concern raised in previous studies of conventional design review panels in England (Durmaz-Drinkwater & Platt, Citation2019; Platt, Citation2015; Punter, Citation2011). As one CQP panellist remarked:

The Cambridgeshire Quality Charter encourages holistic design which of course all panels should, but without the experts on the panel that can be a struggle. Without Connectivity, Climate and Community, we would get lots of discussion (in the review process) on Character. I explain at length to other panels I sit on that the aesthetics of the architecture is one of our CQP’s “4 Cs” – Character.

As another panellist also argued:

It is about changing expectations right at the outset through establishing a Quality Charter framed around the “4 Cs.” Change comes in many ways and changing mind-sets is key, so that poorly thought-out plans never materialise.

The planning officers equally saw the value in the way that the CQP structured the review process, with one officer noting that: “each sustainability principle is taken into account, and the right information is provided. It helps (the applicant) prioritise things to consider as important in relation to the ‘4 Cs’.” Although, another officer noted that members “cannot simply ask for more solar panels for example. It is a give and take.” As one panel member acknowledged: “suggestions are taken on board but not always implemented…I guess it remains an ambition that we are pushing for high sustainability standards through our Charter, as far as it’s possible.”

The architects also welcomed the CQP’s distinct review process, both for themselves and in relation to their interactions with clients. As one noted:

Presenting under the “4 Cs” makes us structure our arguments much more carefully and to consider different sustainability elements that we had not given much thought to before. This rigour also helps us persuade our client that we must raise the bar.

Yet, the architects also stressed the difficulty in making developers take suggestions on board because of their focus on economic viability, cost, and profit. In particular, when a developer plans to acquire and develop a site, they need to have an assurance about how much it will cost them. As one architect suggested:

If they (developers) think that the review is going to make for a more efficient scheme or more profit or a better place and then more profit, then that is what they want to hear, and they will be more willing to engage.

Many of the developers suggested that they had “pushed backed” on certain CQP recommendations, arguing that the members displayed “wishful thinking,” such as expecting green and smart technology to be included as a key component of the Charter’s “Climate” checklist (see ). Many suggested that the panel members were oblivious to market pressures, as one contended:

Developers are going through a period in which the market has flattened. We are a business at the end of the day. We must make sure that whatever we build hits the right price range for those who are going to buy, which has an impact on how projects evolve. I am not sure whether that is totally picked up by the panel. Quite often we are asked to add more detail or variety (with respect to sustainability considerations) and we can do all that, but it comes at a cost.

The Value and Limitations of the CQP Process

The CQP process is a private matter between the developer, local authority planners and the CQP, and not open to the public. This tension, between lack of access afforded to the public and local democracy, arguably creates the design review’s elitism and remains a feature of design review panels across England and elsewhere (Durmaz-Drinkwater & Platt, Citation2019; Richardson & White, Citation2021). Moreover, given that the design reviews are closed discussions among professional experts, difficulties also exist in measuring the impact of the panels’ specific recommendations on individual development proposals.

Our study sought to address this problematic by extracting relevant information, as far as possible, from the CQP minutes and annual reports (). The CQP minutes of each review are prepared by a secretariat. They only summarise the discussions among the respective stakeholders, however, (and are available on request). The CQP annual report is written by the Chair and the three Deputies. It is presented to the CQP Steering Group made up of Cambridgeshire County and the two local Councils’ senior executives and locally elected councillors, and then made available to the public on the CQP website. Despite the lack of public access to the meetings’ full discussions, the annual report has its merits. As one of the CQP panel members remarked:

The CQP invented the idea of making an annual report to the Steering Group in 2012. We have talked in many forums about its importance. This has now become common practice in London (design review) panels and Design Southeast. We led the way here.

The main purpose of the annual report is to document the CQP successes and wider impact, and to facilitate stakeholder debate around design issues and to offer more support, such as training to planning officers on how new development can be delivered to high sustainability standards. There was a consensus among panel members that discussing the CQP’s experiences has had major benefits in developing a wider understanding among elected councillors and senior officers about the importance of sustainability considerations, and in doing so has helped maintain political support in this regard.

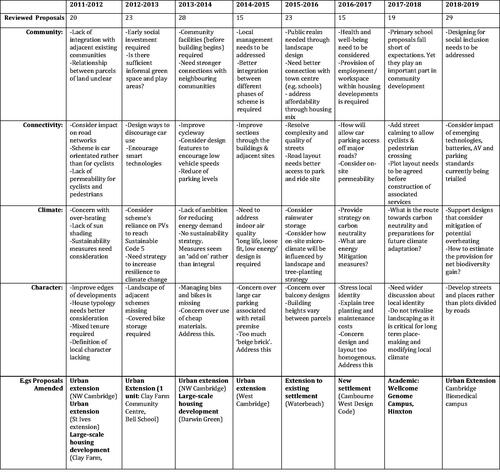

summarises the number of applications reviewed by the CQP between 2011 and 2019, and the types of issues that the panel raised in relation to the “4 Cs.” It also provides examples of development schemes where applicants took panel recommendations on board and altered their respective projects. These schemes varied in size, ranging from single units (for example, a school within a site of strategic significance) to large-scale housing developments and large masterplans (for example, the University of Cambridge Northwest Eddington).

Figure 7. Examples of issues raised by the Quality Panel in relation to the Quality Charter’s “4 Cs” (source: compiled by authors during fieldwork).

Whilst it remains difficult to substantiate whether framing the discussion around the “4 Cs” produces better sustainable outcomes on the ground, panel members drew attention to the numerous schemes which had undergone the rigorous CQP review process that had won national prestigious awards. A panel member, who is one of the co-organisers of England’s annual National Design Awards, noted that:

Since 2009, the Cambridge area overseen by the CQP has won 24 housing design awards, which is more awards than all the major English cities, with the exception of London.

Another panel member highlighted specific examples built to high sustainability standards:Footnote2

Housing developments in Cambridgeshire continually attract visitors and prestigious awards. Marmalade Lane co-housing won an award at the 2020 National Housing Awards. When Great Kneighton scheme was built as Code 4 (for Sustainable Homes), when the norm was Code 3, that changed the market. The Great Kneighton won the overall Building magazine’s Housing Award on 3rd November 2020.

Another example provided by a panel member was:

The University (of Cambridge) scheme Eddington raised the bar to ambitious Code 5 (for Sustainable Homes) and has won three Royal Institute for British Architects national awards. The CQP advised the scheme’s sustainability strategies and influenced the design of the buildings and spaces between them. There will be a wider market effect here when the latest sale schemes go on the market.

Moreover, substantiated evidence also exists in respect to how the CQP has shaped national planning processes and practices. A panel member provided an example, reaffirmed in CQP (Citation2020):

The Chief Planner and dozens of planning and development experts from the Republic of Ireland have visited the Great Kneighton scheme and met with the CQP panellists several times for advice. Their interest was in the super-efficient layout which is mostly three storeys but generates a sustainable family-orientated form of development to compete with tall buildings in high value locations. The Dublin government has since amended its planning codesFootnote3 to enable development proposals to follow the Cambridge model.

The CQP members have also played an influential role in stimulating the UK government’s debate around revising design review methodologies, and including in such reviews greater awareness around sustainability considerations (see CQP Citation2019, Citation2020). Notably, the Chair organised a workshop at the Design Council in 2019, with the discussions then feeding into the MHCLG (Citation2019) National Design Guidance. This Guidance is now framed around three of the CQP’s “4 Cs,” namely community, character and climate (MHCLG Citation2019, para. 36). In 2020, seven CQP members joined with the new Chief Planner and senior officials at the UK Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government in a high-level roundtable discussion on how “Climate Emergency” could play a more central role in the UK government’s new Planning White Paper (UK Parliament, Citation2021).

Yet despite the CQP influencing the establishment of new review processes and practices in England (MHCLG Citation2019), panel members still had reservations about their ability to instill in local planners and developers alike the urgent need to adhere to sustainable development principles. This collective concern was reflected in the CQP 2019 annual report, for example, when stating (with the underlining in that report):

The panel has considerable expertise in the area of climate change but how do we follow this through with the house builders with sufficient speed to effect the necessary change? (p. 4).

…. Platitudes are regularly offered but where are the planning policies with teeth and mechanisms to insist on preparation for future climate adaptations? Will the Councils set higher standards. (p. 5)

The limitations on what the CQP can achieve go beyond such local impediments. Ultimately political will and stronger national legislation are required so that sustainability considerations are elevated beyond current practice, with developers forced to comply.

Discussion

Overall, the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter has set up the expectation that fostering a design-led delivery of sustainable development is of paramount importance as Cambridgeshire and South Cambridgeshire Local Councils implement their strategic growth plans (CCC Citation2018; SCDC Citation2018). Further, the knowledge that the CQP’s independent and expert advice exists is of value to the local planning authorities. Mirroring other studies, the design review panel clearly offers access to expertise that is otherwise unavailable to planning officers (Platt, Citation2015; Richardson & White, Citation2021). Yet, the Cambridgeshire case also provides new findings to the extant literature. Structuring the CQP review process around the Charter’s “4 Cs” – it was argued by the planners – would strengthen their ability to encourage individual developers to pursue higher sustainability standards right at the outset of the development approval process. It is also of value to the architects of such developments themselves, and who often “struggle to persuade our clients on our own,” as one remarked. Overall, this approach provides an opportunity to move discussions beyond local aesthetics and built form into wider issues of sustainability considerations.

Moreover, the value that the CQP brings to design governance extends beyond the conventional design review process found in England. The CQP’s proactive spectrum of activities, including educational workshops, roundtable discussions, site visit tours and advice to other panels across the country, go beyond the CQP members’ remit, and play an influential role in shaping planning and development industry culture. The benefits of facilitating and establishing such mutual learning and capacity building processes within national design organisations have been described by White and Chapple (Citation2018) for example in respect to Architect and Design Scotland, Punter (Citation2019) in respect to Design Commission for Wales, and Carmona et al. (Citation2018) in respect to now disbanded CABE. Such processes are, however, rarer at the county and local authority level. Dawson and Higgins (Citation2009) highlight the wider educational role of the design review panel at the City of Edinburgh in Scotland. Yet for England, the CQP remains an unusual “deviant case” (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 233), with its influence extending beyond the confines of Cambridgeshire and shaping the national MHCLG (Citation2019) design guidance publication, which is now centred around three of the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter’s “4 Cs” – community, character and climate. By doing so, the government has signalled the importance that local planning authorities should place on sustainability considerations when negotiating with developers.

Limitations remain, however, in the ability of the CQP to enact positive sustainable outcomes on the ground. Despite using the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter’s “4 Cs” checklist to promote sustainability considerations, inherent design governance problematics prevail. The lingering dissensus between public and private interests, subjectivities in determining what in fact merits high sustainability standards, concerns around the apparent arbitrariness around the CQP recommendations and limited community input in the design review discussions, are illustrative of the unresolved design governance problematics suggested by Carmona (Citation2016). Further challenges centre on fragmented responsibility among the numerous professional specialisms and a lack of continuity and consistency, preventing coordinated action on delivering sustainable development principles at the site level. Illustrating the problem of continuity, our research found that while developers often hired renowned architects who would develop the design concept to high sustainability standards, after the review process they would continue with their cheaper in-house team, thereby tempering the original architects’ ideas. Equally, local authority case officers and panel members reviewing development proposals change over time. There was a consensus among the research participants that this loss of continuity negatively affects the design review process and final sustainable development outcomes. These concerns are not unique to Cambridgeshire but occur elsewhere in England (Platt, Citation2015) and in other jurisdictions (Farhat, Citation2019; Hassel Limited, Citation2011; Scheer, Citation1994; White, Citation2016).

The issue with consistency is equally hard to address. Invariably, sites are brought forward by different developers often within the same urban masterplan. Often also there is a lack of understanding as to how different sites fit together, and which only becomes visible on completion with, for example, building heights varying between and within specific development schemes. The CQP members argued that developers must take more time to research the local context, and to ensure their individual schemes have regard for neighbouring developments. Developers, however, know that they can justify their proposed scheme in front of the planning officers and councillors at a further (Reserved Matters) stage, without the CQP in attendance. The influence of the CQP is thereby marginalised, and opportunity is provided for negotiations to happen “behind closed doors” (Newman & Thornley, Citation2002, p. 214).

Moreover, in England, the NPPF allows developers to overturn a planning officer’s request to alter their proposal if they can argue it affects economic viability (MHCLG, 2021). English local authorities also cannot insist that the original architects who developed the proposal concepts continue to work on its implementation. This lack of statutory power explains, in part, the introduction of the design review process in England in the first place – to provide an independent voice to back up local authority decisions (Platt, Citation2015). Yet, the ability of local authorities to hold their ground and adhere to well-intended sustainability principles, as set out for instance in the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter, is ultimately undermined by national policy and priorities. Compromises are therefore made by the need to deliver development outcomes dictated by market processes, and by political priorities that rate economic growth over fostering design-led delivery of sustainable development (Carmona, Citation2009). As in other jurisdictions, competitive market pressures are likely to continue to work against the achievement of high-quality design that aligns with sustainable development principles (Hassel Limited, Citation2011; Paterson, Citation2011; White, Citation2016).

Conclusion

Advocates have long argued that urban design-led principles can provide a necessary framework for the development of long-lasting sustainable communities (Carmona, Citation2009; Lang, Citation1994; Macdonald, Citation2016; White, Citation2016). The adoption of the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter that frames stakeholder discussion around sustainable development principles creates an opportunity for developers to rethink – and improve – their development proposals in terms of the four sustainable principles of: community, connectivity, climate, and character. By moving discussions away from a preoccupation with local aesthetics, and narrowly constructed guidelines, and adopting a more comprehensive approach to place-making, the CQP not only makes recommendations on the quality of proposed schemes, but aims to instil in stakeholders the need to adhere to sustainable development principles as a fundamental criterion.

The approach adopted by the CQP aligns with England’s NPPF on the importance of promoting high quality design standards at the earliest opportunity (MHCLG, Citation2021). Such promotion needs to take place throughout the project evolution process, and the delivery stage. It also requires, as adopted in the CQP, interdisciplinary and experienced panellists dedicating time and effort, as well as a willingness by local planning officers, elected councillors, and applicants to engage in what can be a demanding process. By setting out the agreed principles and by reviewing schemes early on, design review panels can provide the necessary support to English local authorities at a time when they have access to ever fewer resources. As in other jurisdictions, fiscal austerity has hit the local planning profession hard, with different councils experiencing reduced budgets and constrained capacity to sufficiently champion good places on their own (Richardson & White, Citation2021).

Whilst non-regulatory tools are of value within a design governance framework, there remains, however, fundamental limitations as to what a design review panel can achieve, to date (Carmona, Citation2016). Independent panel members cannot insist on matters those developers are not legally obliged to realise (Platt, Citation2015); and without such authority, developers cannot be compelled to revise their development proposals to address panel recommendations. Given the reliance on private sector delivery, its vested interests and uneven bargaining power in negotiations, therefore, continue to hold sway.

Critical questions need to be asked about how such design governance tools are deployed in planning practice and whose interests are legitimised (Richardson & White, Citation2021). In England, while the NPPF encourages the use of design review panels, it also provides economic viability grounds for developers to overturn planning officers’ decisions and panel recommendations (MHCLG, Citation2021). These contradictory revisions in effect constitute a developer charter and assist a UK Government intent to speed up housing delivery. This status quo is retained at the expense of (perhaps more costly) high sustainability standards. As in other jurisdictions, continual demands to accelerate the development approval process work against achieving high quality design, despite being encouraged by well-intended design review principles and processes (Paterson, Citation2011; White, Citation2016).

Ultimately, political will and long-term investment decisions will determine where sustainable development ranks on public, private and political agendas. These key determinants affect the power of influence of design review panels, and of the ability of local planning officers to genuinely elevate design-led planning towards achieving sustainable development principles and outcomes (Glavič & Lukman, Citation2007). Further research is therefore required to focus on ways to overcome these problematics of design governance processes, of which the design review process forms part, and to continue to collectively make the case as to why sustainability matters. Whilst there are acknowledged, inherent difficulties in measuring design review panels’ impact on the ground, this challenge does not negate the need for in-depth, longitudinal research, and to further shine a critical light on the role of design reviews and design panels in promoting sustainable development principles, not just in this one case study location, but also nationally and internationally.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Robin Nicholson, Chair of Cambridgeshire Quality Panel, and all the research participants for their invaluable assistance in the research process, the anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts, and Dr Greg Paine and Jake Davies for their editorial assistance. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicky Morrison

Nicky Morrison is the Professor of Planning at Western Sydney University and senior Visiting Fellow at University of Cambridge. She is WSU’s Director of the Urban Transformations Research Centre and leader of the Urban and Regional Planning Program. She is the academic lead in transforming WSU's Penrith Campus into Penrith Sustainable Innovation Community (PSIC).

Lidija Honegger

Lidija Honegger studied political science in Switzerland and planning in the UK. She is currently working as a strategic urban planner at WSP UK Limited in London, where she follows a people-centred approach to development advisory and strategic placemaking.

Notes

1 The four UK countries, England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, have their own primary planning legislation and land use planning systems. This paper’s focus is on England.

2 Marmalade Lane is England’s largest co-housing project, consisting of 42 homes, and resulting from a collaborative design process. Great Kneighton consists of 2,300 homes in the southern part of the City of Cambridge. Eddington is the largest housing development undertaken by the University of Cambridge and comprising on completion 4000 homes. All of these schemes have been reviewed extensively by the CQP. Since 2010, the CQP has seen, for example the Eddington master plan, landscape plan, Design Code, all 16 lot plans, and individual building plans within Phase 1, and often twice (cited in interviews and panel reports).

References

- Berke, P. (2016). Twenty years after Campbell’s Vision: Have we achieved more sustainable cities? Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(4), 380–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1214539

- Cambridge City Council (CCC). (2018). Cambridge Local Plan October 2018. Cambridge City Council.

- Cambridgeshire County Council (CCC). (2003). Cambridge and Peterborough structure plan 2003. Cambridgeshire County Council.

- Cambridgeshire Horizons. (2008). Cambridgeshire quality charter for growth. Cambridgeshire Horizons.

- Cambridgeshire Quality Panel (CQP). (2019). Eighth annual report on the work of the Cambridgeshire Quality Panel for the period October 2018 to October 2019 for the Steering Group, the Quality Panel and Planning Officers. https://cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/8th-Annual-Report-on-the-Cambridgeshire-Quality-Panel.pdf

- Cambridgeshire Quality Panel (CQP). (2020). Nineth annual report on the work of the Cambridgeshire Quality Panel for the period October 2019 to October 2020 for the Steering Group, the Quality Panel and Planning Officers. https://cambridgeshireinsight.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/9th-Annual-Report-on-the-Cambridgeshire-Quality-Panel.pdf

- Campbell, S. (2016). The planner’s triangle revisited: Sustainability and the evolution of a planning ideal that can’t stand still. Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(4), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2016.1214080

- Carmona, M. (2009). Sustainable urban design: Definitions and delivery. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 12 (1), 48–77. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2009.027528

- Carmona, M. (2016). Design governance: Theorizing an urban design sub-field. Journal of Urban Design, 21 (6), 705–730730. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2016.1234337

- Carmona, M. (2019). Marketizing the governance of design: Design review in England. Journal of Urban Design, 24(4), 523–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1533373

- Carmona, M., de Magalhães, C., & Natarajan, L. (2018). Design governance the CABE way, its effectiveness and legitimacy. Journal of Urbanism, 11 (1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2017.1341425

- Dawson, E., & Higgins, M. (2009). How planning authorities can improve quality through the design review process: Lessons from Edinburgh. Journal of Urban Design, 14 (1), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800802452930

- Design Council. (2013). Design review: Principles and practice. Design Council.

- Design Council. (2018). Design review insight report. Design Council.

- Durmaz-Drinkwater, B., & Platt, S. (2019). Better quality built environments: Design review panels as applied in Cambridge, England. Journal of Urban Design, 24 (4), 575–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1533372

- Farhat, R. (2019). Is semi-discretionary design review wieldy? Evidence from Seattle’s programme. Planning Practice & Research, 34 (1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1548213

- Farhat, R. (2021). Design guidelines for wieldier discretionary review: Evidence from Portland. Journal of Urban Design, 26(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2020.1772045

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 (2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Glavič, P., & Lukman, R. (2007). Review of sustainability terms and their definitions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(18), 1875–1885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.12.006

- Global Planners Network. (2018). Vancouver Declaration 2006: World Planners Congress, Vancouver, Canada: Global Planners Network. Retrieved May 9, 2018, from http://www.globalplannersnetwork.org

- Hassel Limited. (2011). Design review research. Prepared for Green Building Council of Australia.

- Lang, J. (1994). Urban design: The American Experience. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Kim, J., & Forester, J. (2012). How design review staff do far more than regulate. URBAN DESIGN International, 17(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2012.11

- Macdonald, E. (2016). The planning dimension of sustainable urban design. Journal of Urban Design, 21(1), 43–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2016.1114378

- Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2019). National design guide: Planning practice guidance for beautiful, enduring and successful places. MHCLG.

- Ministry for Housing, Communities & Local Government (MHCLG). ( 2021) National planning policy framework. MHCLG.

- Newman, P., & Thornley, A. (2002). Urban planning in Europe: International competition, national systems and planning projects. Routledge.

- Paterson, E. (2011). Design review in the UK: Its role in town planning decision-making. URBAN DESIGN International, 16 (2), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2011.4

- Platt, S. (2015). Design Review: What is it for and what does it achieve? Planning Advisory Service. DCLG.

- Punter, J. (2003). From design advice to peer review. The role of the urban design panel in Vancouver. Journal of Urban Design, 8 (2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800306483

- Punter, J. (2011). Design review – An effective means of raising design quality? In Urban design in the real estate process, edited by S. Tiesdell and D. Adams, 182–198. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Punter, J. (2019). Design review in Wales: The role of the design commision for Wales. Journal of Urban Design, 24 (4), 605–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1557514

- Raco, M. (2007). Building sustainable communities: Spatial policy and labour mobility in post-war Britain. The Policy Press.

- Razaghi, T. (2018). Sydney sees “cultural shift” as major projects subject to design review panels. https://www.domain.com.au/news/sydney-sees-cultural-shift-as-major-projects-subject-to-design-review-Panels-20180404-h0yc5g/

- Richardson, R., & White, J. (2021). Design Governance, austerity and the public interest: Planning and the delivery of “well designed places”. Planning Theory & Practice, 22(4), 572–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1958911

- Ritchie, A., & Thomas, R. (2009). Sustainable urban design: An environmental approach. Taylor & Francis.

- Scheer, B. C. (1994). Introduction: The debate on design review. In Design review: Challenging urban aesthetic control, edited by B. C. Scheer and W. F. E. Preiser, 1–10. Chapman & Hall.

- South Cambridgeshire District Council (SCDC). (2018). South Cambridgeshire Local Plan 2018, South Cambridgeshire District Council.

- UK Parliament. (2021). Planning for the future: Planning policy changes in England in 2002 and future reforms. UK Parliament.

- United Nations (UN). (2020). Sustainable development goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/

- White, J. (2016). Pursuing design excellence: Urban design governance on Toronto’s waterfront. Progress in Planning, 110, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2015.06.001

- White, J., & Chapple, H. (2018). Beyond design review: Collaborating to create well-designed places in Scotland. Journal of Urban Design, 24(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1529537

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). The Brundtland Report: Our common future. UN Department of Public Information.