Abstract

When planning sustainable districts, planners mediate between the knowledge claims of citizens and experts. The planning strategies nudging and participation provide contradictory ideas about how planners can perform this mediation. We analyse handbooks for the two strategies, guided by the question: whose knowledge counts? These handbooks provide citizens, experts and planners with varying degrees of authority. While nudging positions behavioural experts as holding authority, and citizens are central in participation, planners feature in the background in both strategies. We show how these seemingly apolitical strategies are actually value-laden. Implementing them literally will undermine planning for urban sustainability.

Introduction

Sustainability is high on the urban planning agenda. A central concern is to plan districts so that they enable sustainable household practices in, for example, transport, living and food. In this paper, we analyse two popular strategies for influencing urban dwellers’ everyday practices: nudging and participation. These strategies do not force inhabitants into changing their way of life towards sustainability, but instead gently nudge citizens to make sustainable choices through changes in the physical and social environments, or invite citizens to participate in processes to influence their district. Hence, the two strategies provide different ideas about how to deal with the value-laden and contested character of urban planning. While nudging suggests expert-driven planning based on insights from behavioural science, participation makes the case for empowering citizens and including their local knowledge in urban planning.

We consider planning as “the guidance of future action” (Forester, Citation1999, p. 1). In this view, planning is not merely an organisational, technical and regulatory task, but also a value-laden practice of making choices about places and societies (Campbell et al., Citation2014). The making of societal choices inevitably involves excluding certain actors and certain ways of knowing from the process of planning (Kühn, Citation2021). How planning is to perform this necessary art of exclusion (Connelly & Richardson, Citation2004) has been the subject of longstanding debates within planning theory. The still influential ideas of rational planning entail that planning practice follows a positivistic scientific process by considering options and making optimal value-free choices (Faludi, Citation1973), while the theory of communicative planning instead conceptualises planning as a relational practice of making meaning through interaction (Forester, Citation2020; Healey, Citation1997; Innes & Booher, Citation2018). Nudging and participation can be related to these two planning theories: nudging might be understood as an attempt to renew rational planning, while participation is related to the ideas of communicative planning.

Planners can assume a constructive role in mediating between different ways of knowing in planning processes (Forester, Citation2020; Puustinen et al., Citation2017). The two predominant strategies of nudging and participation incorporate different ideas about the role of planners. The tension between expert-driven nudging and bottom-up participation suggests that planners, if they wish to exercise discretion, should choose between different ideas about whose knowledge counts. In this paper, we wish to clarify how nudging and participation charge planning actors with varying degrees of authority, and thereby influence the process and outcome of urban planning.

“Nudgers” and “participators” seem to operate in alternative universes. In the fragmented practice of urban planning, participation and nudging are often implemented in separate projects and the exchange of ideas between scholars in behavioural science and in communicative planning is limited. We argue that much can be learned about urban sustainability by comparing, contrasting and combining the two strategies and their theoretical underpinnings. The purpose of this paper is to analyse how nudging and participation allocate authority among citizens, experts and planners. We conduct a frame analysis of nudging and participation handbooks issued by intergovernmental and Swedish agencies in pursuit of the question: whose knowledge counts in nudging and in participation? Handbooks form ideal material for our inquiry, as they translate abstract ideas into planners’ everyday work. To analyse the implementation of the strategies is outside our scope. The practical interest in nudging and participation and the longstanding debates between the underlying rational and communicative planning theories contribute to the relevance of this paper.

First, we take stock of the debate between rational and communicative planning and explain how nudging and participation are recent articulations of the two core ideas in the debate. Further, we explain how we zoom in on the allocation of authority among planners, experts and citizens. We next describe our methodology: a frame analysis of intergovernmental and Swedish handbooks for nudging and participation. Thereafter, we show that nudging and participation frame different problems – namely flaws in citizens’ decision-making versus flaws in the governance system – but somewhat similar solutions – namely placing professional experts (behavioural scientists and facilitation experts) in positions of authority. Finally, we theorise our findings as alternative “scripts for the performance of authority” and argue that the dramaturgical perspective can be useful for understanding how nudging and participation allocate authority among citizens, experts and planners.

Nudging and Participation: Whose Knowledge Counts?

In nudging, behavioural science experts work in the backstage of planning to design environments that encourage people to do the right thing: to act according to expert definitions of sustainable behaviour. Nudging intends to make it easy to live healthily, use public transport and save water and energy. Nudging has attracted a lot of attention as a promising strategy for gently pushing inhabitants towards sustainability (Lehner et al., Citation2016; Schubert, Citation2017). Based on insights from behavioural economy, psychology and neuroscience, nudging holds that people’s rationality is bounded: i.e., that people make suboptimal choices based on habits, desires and preferences, rather than rational analysis. Nudging targets irrationality by subtly changing a physical or virtual environment and thus inviting individuals to choose “the better” (sustainable) option (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). While nudging was originally defined as a strategy for influencing individual behaviour to the advantage of these individuals, the strategy has recently been broadened. For instance, “the green nudge” (Schubert, Citation2017) aims to advance the common good through, for example, nudging in the design of urban districts to promote sustainable choices.

If expert authority is assumed in nudging, it is instead questioned in participation. According to the ideas of participation, professional experts ought not to single-handedly define problems and solutions for citizens, as citizens are capable experts in their own everyday life. Participation gained currency in reaction to top-down governance, where detached experts knew little about the specific situation, and inhabitants/citizens’ ideas and knowledge were not taken into account (Innes, Citation1998). Participatory processes engage citizens in the design, planning and management of their community. Participation is claimed to bring self-sustaining change processes through local ownership, improved action competence among citizens (Fung, Citation2015; Halbe et al., Citation2020) and improved compliance to norms. In participatory processes, goals and aims are developed by the citizens, and may or may not be in line with scientific definitions of sustainability. Even so, professional expertise and citizens’ knowledge are often combined in participatory processes, for example through “joint fact finding,” where actors with diverging interests are collaborating with expert support to develop knowledge about the planning issue at hand (see Karl et al., Citation2007). Participation is a strategy that has long been employed by planners in the planning of urban districts.

Nudging and participation can be linked to two ideal-typical approaches to planning: nudging can be understood as related to expert-driven rational planning (Faludi, Citation1973), and participation shares similarities with the competing ideas of communicative planning (Forester, Citation1999; Healey, Citation1997; Innes & Booher, Citation2018; Sager, Citation2018). Hence, the two strategies bring the classic discussion about the role of different kinds of knowledge to today’s urban planning.

The role of knowledge in urban planning is contested. Ever since the protests against social engineering in the 1960s, the idea of objective and thereby authoritative expert knowledge has been questioned. The planning scholar Paul Davidoff (Citation1965, p. 331) expressed the spirit of those times as: “The prospect for future planning is that of a practice which openly invites political and social values to be examined and debated. This argument rejects prescriptions for planning which would have the planner act solely as a technician.” Following the turbulence of the 1960s, the role of professional experts in planning was no longer clear-cut. The following decades saw a democratisation of expertise. The ideas of citizen participation were gaining ground in theory and in policy and, to some extent, in practice. During the 1990s, participation was mainstreamed into planning frameworks, and “communicative planning” was coined as the new planning paradigm (Innes, Citation1995). Agenda 21, with its emphasis on participation, became the global framework for transitions toward sustainability. The ideas of expert-driven planning were still in use, but now complemented and challenged by the ideas of participation.

Communicative planning theory challenged expert-driven rational planning with the argument that planning could become more democratic if citizens’ knowledge was included (Forester, Citation1999; Healey, Citation1997; Innes, Citation1995). A democratisation of planning would require improved communication between planning actors such as planners, politicians, citizens and private-sector representatives (Mattila, Citation2020). Scholars in communicative planning developed their ideas in theoretical streams influenced by sociological institutionalism (Healey, Citation1997, Citation2012), critical pragmatism (Forester, Citation1999, Citation2020) and the practices of consensus building and collaborative rationality (Innes, Citation1995; Innes & Booher, Citation2018). They had in common an interest in public debate, political accountability and transparency (see Sager, Citation2018, pp. 93–94).

Since these early days of communicative planning, the theory has been modified in response to sustained critique and changes in planning contexts (see Innes & Booher, Citation2018; Sager, Citation2018). Contemporary versions of communicative planning still deconstruct expert-driven planning, while also acknowledging that “without attention to research and expertise, we risk acting stupidly […]” (Forester, Citation2020, p. 19).

More recently, the rise of populism and post-truth politics have put the relation between professional expertise and citizens’ knowledge in a new light. Proponents of participation and communicative planning find themselves in bad company, as they are joined in their deconstruction of expertise by authoritarian politicians who challenge democratic institutions. Efforts to undermine expert authority are an integral part of populist movements that resist the scientific agenda of urban sustainability (Sager, Citation2020).

Nichols (Citation2017) claims that in the era of populism, we are witnessing an organised campaign, to replace expert authority with authoritarian politicians. He argues that the relationship between citizens and professional experts has collapsed, heralding the end of expertise and providing opportunities for the enemies of democracy.

Not only do increasing numbers of lay-people lack basic knowledge, they reject fundamental rules of evidence and refuse to learn how to make a logical argument. In doing so, they risk throwing away centuries of accumulated knowledge and undermining the practices and habits that allow us to develop new knowledge. (Nichols, Citation2017, p. 3)

Others argue that we have not come to the end of expertise, but rather to a crisis of expertise. This crisis is not merely about mistrust of experts, but rather about the interplay of two trends (Eyal, Citation2019): while some communities are increasingly sceptical and dismissive of scientific findings and expert opinion, other communities hold an unprecedented trust in science and expertise. These trends reinforce one another as communities drift apart.

Planners inevitably come across an “apparent tension between the inequalities of knowledge, experience and skill that characterize expertise, and democratic ideals and practices of equality and contestation” (Moore, Citation2017, p. 3) in their work. Hence, “whose knowledge counts?” is a key question for planners.

In the inquiry into nudging and participation, we subscribe to a relational view of knowledge. We define professional expertise as the possession of special skills, experience, information or knowledge grounded in a practice with shared rules for knowledge production recognised as legitimate in the wider society (see Moore, Citation2017, pp. 6–7). A claim to expertise is a claim to possess knowledge that those outside the community of experts do not possess. In the planning of urban districts, professional expertise meets citizens’ knowledge. This knowledge originates from experiences of everyday practices in urban places, from living, working, playing and travelling in those locations. Citizens have valuable and intimate knowledge, which might be largely inaccessible for experts, about the urban space. When professional expertise and citizens’ knowledge meet in urban planning, the question of who has the authority to define problems and solutions becomes prominent.

Authority is use of power that is considered legitimate by those subject to it. Authority is at play when one or several actors influence, or even direct, the thoughts and actions of other(s) in ways that the subordinate actors consent to (Forst, Citation2015; Haugaard, Citation2018; Weber, Citation1978). Weberian accounts of authority are interested in the command/obedience relationship between actors in positions of power (e.g., experts and planners) and their subjects (e.g., citizens). In addition to the Weberian understanding, we draw on more recent accounts of authority inspired by Austin (Citation1975), which emphasise the relational character of authority (Haugaard, Citation2018; Mik-Meyer & Haugaard, Citation2020). In our usage, the concept is concerned with negotiations between social subjects in everyday interactions. Thereby, we are, besides the authority of planners and experts, also interested in “citizens’ authority”; i.e., their right to be the author of their own actions and to be taken seriously (Mik-Meyer & Haugaard, Citation2020, p. 4). Authority is an important property in contested planning processes, as it crucially shapes which route sustainability transitions take. Our inquiry brings three positions of authority to the fore – expert, citizen and planner – each with its own justification. Expert authority presumes inequality: i.e., an expert has special wisdom, experience or knowledge not readily available to others (Moore, Citation2017; Warren, Citation1996). In contrast, citizen authority presumes equality: i.e,. in democracies adult citizens are equally deserving of respect and hold the right to speak for themselves and influence their own lives by having their knowledge recognised as valid (Haugaard, Citation2018; Mik-Meyer & Haugaard, Citation2020). Finally, the most established justification for planners’ authority is that they are working for the elected government, and thereby represent a presumably legitimate regime (Puustinen et al., Citation2017). Hence, planners can hold key positions in mediating between expert and citizen authority. There are also other kinds of less established justifications for planners’ authority, for example as advocates or activists working for various stakeholder groups (see Sager, Citation2016).

In sum, we inquire into the tension between the knowledge of experts and citizens in the planning of urban sustainability through the lens of authority. We do so by analysing how handbooks for nudging and participation distribute authority between three important subject positions in planning: the planner, the professional expert and the citizen. Notably, we study how handbooks construct relations of authority and thereby leave to future research to examine the extent to which these handbooks might shape the actual performance of authority in urban planning.

Analysing Handbooks for Nudging and Participation

We conducted a frame analysis into handbooks for nudging and participation issued by intergovernmental and Swedish agencies. Handbooks are suitable study objects since they reflect how government agencies understand relations of authority during the planning of sustainable urban areas. The agencies issue handbooks to structure the field of action for actors in planning practice. Handbooks construct subject positions such as “planner,” “expert” and “citizen” to justify their respective places in planning, explain how they should relate to each other, and provide them with varying degrees of authority in accordance with underlying ideas of sustainability planning. Hence, handbooks are attempts to “make up” the identities and authority of planning actors (Cashmore et al., Citation2015).

We consider the nudging and participation handbooks as alternative “scripts for the performance of authority” in the planning of urban sustainability. This dramaturgical perspective is fruitful since planning involves negotiations between actors with different roles and different knowledge claims about sustainability problems and solutions. Through the theatre analogy developed by Goffman (Citation1973) and Austin (Citation1975), we view these negotiations as social performances. Governance actors attempt to perform authority by assuming positions such as “expert,” “citizen” and “planner.” Attempts to perform in positions of authority can be rendered more-or-less valid by other actors. When a person is seen to perform an authority position correctly, their action is accepted as valid and vice versa. Whether an attempt to assume an authority position is considered as successful depends on how well accepted the justification of that position is among the involved actors in a specific situation (Haugaard, Citation2018). Nudging and participation handbooks charge planners, experts and citizens with different degrees of authority and thus script the performance of authority.

We selected handbooks from intergovernmental agencies, namely the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the UN, to obtain the most recent framing of the two strategies formulated by internationally leading experts. In addition, we chose handbooks from Swedish agencies. Sweden offers an interesting case, as Swedish authorities have worked for decades with participation as a planning approach, and nudging has recently gained policy ground (Lehner et al., Citation2016; Mont et al., Citation2014).

Our selection was based on a general search for handbooks about nudging and participation through a search engine, and a targeted search for publications of specific organisations that we knew worked in these areas. For our selection of nudging handbooks at intergovernmental level, we learned that many international organisations have recently started some sort of nudging (or behavioural insights) unit. While many such units have websites and published case studies, the OECD handbooks were often referred to as providing key guidance for planners across the globe. For Sweden, we selected the nudging handbooks from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, an influential organisation in sustainability planning. For our selection of participation handbooks at intergovernmental level, we selected the one published by the United Nations Democracy Fund, a key organisation in the field of democracy and participation globally. Just like the OECD handbooks, this handbook was authored by well-known specialists in the field. For Sweden, we selected the participation handbooks published by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, which is the key organisation for participation in Sweden ().Footnote1

Table 1. Selected handbooks.

Even if the handbooks at times explicitly discuss the relationship among planners, experts and citizens, the distribution of authority remains tacit: expressed in the topics selected and omitted, in the way problems and solutions are identified and in the metaphors used. Therefore, we opted for frame analysis (Van Hulst & Yanow, Citation2016; Rein & Schön, Citation1996), which enables the researcher to access the assumptions and ideas “that lie beneath the more visible surface of language or behavior, determining its boundaries and giving it coherence” (Rein & Schön, Citation1996, p. 88).

In the analysis, the terms “frame” and “framing” signify how the handbooks make certain features of sustainability planning salient and combine them into a more or less coherent pattern, with the purpose of guiding planning action. Just like a picture frame, the handbooks create a boundary separating what is inside from what is outside, and thereby suggest how planning actors can interpret situations. Hence, we analyse how framing performs two functions: explaining what is going on by identifying problems, and making certain actions seem logical by suggesting solutions to these problems (Van Hulst & Yanow, Citation2016; Rein & Schön, Citation1996).

We chose to focus the analysis on three frame topics (Van Hulst & Yanow, Citation2016) that reveal how the handbooks distribute authority among planning actors: governance strategy (since our interest is in the purposeful planning of urban sustainability); knowledge (because the framing of this topic reveals whose knowledge counts); and ethics (since the distribution of authority raises ethical questions). We gradually distinguished these topics through consecutive rounds of analysis. As we analysed the handbooks, we learned that these topics were central for understanding the distribution of authority in nudging and participation. In the analysis, we searched for how problems were framed within each topic, and how this provided a logic leading to certain solutions. Two questions guided the analysis of each topic: what is the problem with this topic according to the handbooks? and what solution do the handbooks prescribe for the problem?

Pursuing the analytical questions, we conducted the analysis in consecutive rounds. We first read the selected handbooks and identified quotes that were relevant for our purpose. The quotes were categorised as “topic,” “problem” or “solution.” We analysed the quotes with the view of identifying the framing of problems and solutions within the three topics. To do this, we searched for the features and concepts made salient, analysed the metaphors, elicited the narratives and identified what was omitted (the silences), and reconstructed how the framing of problems made certain solutions logical. As part of the analysis, we wrote consecutive reports of our interpretation of the framing of each topic in the nudging and participation handbooks. We discussed these reports in the research team to inform the next round of analysis. After three rounds of analysis, we arrived at the findings presented here. In the first analytical reports, we distinguished minor variation (“sub-frames”) between the Swedish and the intergovernmental handbooks. For example, we found that the Swedish nudging handbooks were to some extent more inclined to accept paternalism and that the Swedish participation handbooks provided a broader variety within the topic of governance strategy. Given the purpose of our inquiry, we decided that the level of detail in the first analytical reports was not needed. Hence, we arrived at the findings presented below.

Results: Whose Knowledge Counts in Nudging and Participation?

Handbooks for Nudging

Have you ever grabbed a chocolate bar at the check-out line only to regret it later? Filled up your entire bowl with pasta even though you intended to only take a small portion? […] Why do people make such choices? Before making assumptions, it is important to consider what drives decision-making […]. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 16)

The findings from our analysis of handbooks from the OECD and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency are summarised in .

Table 2. Summary of the findings from the nudging handbooks.

Framing Governance Strategy

Problem framing in the nudging handbooks revolves around an allegedly flawed knowledge basis for behavioural change interventions: governance is allegedly still informed by outdated perceptions of rationality.

Behavioural science has shown that context and biases can influence decision-making. Everyday examples of this include forgetting important appointments, filling out forms incorrectly because they are too difficult to understand, and even driving above the speed limit because other drivers are doing so. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 16)

In the BASIC-toolkit (OECD, Citation2019, p. 14), the shortcomings of human decision-making are succinctly formulated as ABCD: Attention (“People have limited attention and recall”); Belief formation (“People tend to underestimate speed and be overconfident when performing tasks, such as driving”); Choice (“People tend to align with the behavior of others and what others think is appropriate”); Determination (“people often have difficulty staying motivated if left to their own devices […].” The handbook frames a problem around the lack of appreciation of the boundedness of human decision-making in intervention design.

The solution flowing from framing a problem of bounded rationality is to suggest that governing ought to be based on insights from the behavioural sciences.

At all stages in the policy cycle, policies can be improved with BI through a process that looks at behaviours, analysis, strategies, interventions and change […]. This allows policy makers to get to the root of the policy problem, gather evidence on what works, show support for government innovation, and ultimately improve policy outcomes. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 14)

Hence, the handbooks suggest that knowledge from behavioural science ought to be applied to govern citizens’ behaviour more effectively because:

A better understanding of human behaviour can lead to better policies. Policy makers looking for a more data-driven and nuanced approach to policy making should consider what actually drives the decisions and behaviours of citizens rather than relying on assumptions of how they should act. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 13)

At the core is the idea that governance of behaviour ought to be adjusted to the context. The handbooks acknowledge that general knowledge about what works cannot be implemented without an understanding of contextual factors. Hence, there is an emphasis on conducting experiments and learning from the results before upscaling behavioural change interventions.

Before an intervention is implemented in full scale, the effects must be evaluated in order to identify the best way to influence behaviour and avoid potential negative effects. To use randomised controlled experiments is, according to us, the most suitable method, even if it might sometimes be necessary to use other methods for evaluation. (Gravert & Carlsson, Citation2019, p. 28)

The solution offered by nudging is to base governance on knowledge gained through experiments and systematic research. Controlled experiments based on behavioural science methodology are seen as the most reliable mode of developing knowledge about “what works” in a specific context. “Behavioural interventions are policy initiatives which are designed explicitly on previously existing behavioural evidence and/or based on a new experiment” (OECD, Citation2019, p. 4).

Framing Knowledge

The nudging handbooks frame behavioural science as relevant knowledge, capable of solving the problem, namely citizens’ inability to make rational decisions. Individual problems (obesity and bad economy) and collective problems (environmentally unfriendly behaviour) are linked to citizens’ bounded rationality and lack of self-control. The problem for governing is that intervention design is not informed by expertise in behavioural sciences.

In many cases, it is the lack of relevant knowledge that leads to the lack of evaluations. […] Practitioners ought to prioritize to hire people with relevant skills (statistics, behaviour sciences such as economy and psychology) that can help designing nudges and conduct evaluations. (Gravert & Carlsson, Citation2019, p. 25)

This quote illustrates the narrative in the handbooks: planners (“practitioners”) lack the knowledge needed to design and implement behavioural change interventions. The lack of knowledge includes relevant behavioural science research, but also knowledge about research methods in these disciplines.

The solution offered in the handbooks is to fill the knowledge gap by making use of behavioural science expertise and using scientific methods in planning. The logical solution is to charge experts in behavioural science with the authority to intervene in the design, implementation and evaluation of interventions.

To accurately implement a nudge requires planning and knowledge. Practitioners who wish to work with nudges are recommended to collaborate with experts in organizations and universities in order to design, implement and evaluate the intervention. (Carlsson et al., Citation2019, p. 5)

Framing Ethics

The handbooks, especially those of the OECD, discuss ethics at length, but only in terms of research ethics. Two core assumptions inform the framing of ethics: planning practice ought to mimic science and avoid or minimise intervention in individuals’ freedom of choice. Ethical problems and solutions are framed based on these assumptions.

One problem is framed around the observation that planning practice might depart from “the scientific method.” Hence, the OECD guidance identifies “bias” as problematic. “Policymakers suffer biases too, which can influence the decision to target certain behavior(s)” (OECD, Citation2019, p. 17). Similarly, the OECD handbooks make salient how ethical problems arise when scientific methods are used in planning.

Behavioral analyses usually observe or study human behavior close up and often in their individuals’ everyday environments, running the risk of affecting participants’ personal lives and colliding with people’s privacy. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 25)

These quotes exemplify how the handbooks construct ethical problems based on the assumption that planning ought to mimic scientific practice. A logical consequence is that solutions are derived from research ethics. Hence, ethical guidelines and review boards are suggested as solutions.

Seek ethical approval and competencies where necessary. Use the ethical review board or relevant authorities within which the behavior is studied to grant approval. […] Consider what guidelines must be followed when studying behavior up close. […] (OECD, Citation2019, p. 25)

The suggestion to apply research ethics prepares the ground for placing scientific experts in positions of authority. “Always consult experience. Make sure that experiments are conducted by people with experience in experimental design, intervention and reporting to ensure proper protocols are followed” (OECD, Citation2019, p. 39).

Based on the assumption that planning ought to refrain from interfering with freedom of choice, the OECD handbooks stipulate that nudging should not threaten “individual rights, values and liberties when targeting behavior change” (OECD, Citation2019, p. 17).

In line with the emphasis on freedom of choice, the handbooks stress that not all behaviours should be targeted by nudging.

Observe the limits of legitimate public policy interventions. Not all behaviors driving a policy problem fall within the legitimate confines of policymaking. Make sure that you refrain from targeting and changing behaviors that cannot be defended as being in the public interest or aligned with government priorities. (OECD, Citation2019, p. 17)

The Swedish handbooks on green nudges depart from the OECD handbooks by stressing that even if those who are nudged do not agree with the intention of the nudge, designers of nudges should stand firm in cases when the nudge is for the common good.

An important difference between a conventional nudge and a green nudge is that the green nudge is intended to decrease environmental impact from for example consumption. This means that the one who is nudged might actually be worse off after the nudge. I believe that it is best to stand up for the purpose with the nudge and not try to justify it with arguments like: “it is better for people to bike than go by car to work […].” (Carlsson et al., Citation2019, p. 3)

Handbooks for Participation

Non-participation by much of the community is the starting point for unrest and dissatisfaction – you may want to involve people, but cynicism holds people back. Demonstrating their ability to have a real connection to an informed decision and being genuinely heard in a process is essential to overcoming this. (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 24) ()

Table 3. Summary of the findings from the participation handbooks.

Framing Governance Strategy

The participation handbooks claim that it is increasingly difficult to implement contested decisions due to resistance from citizens: “[…] public opinion makes it hard to take complex decisions, resulting in these decisions being watered down or not taken” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 12). The underlying problem is that citizens are not involved in the democratic process in a way that facilitates their ability to make informed judgements. Rather, according to the handbooks, citizens tend to be encouraged to hold on to their preconceived opinions. The handbooks frame the problem, not as flaws in people’s judgement, but as flaws in the political systems – leading to polarisation due to lack of opportunities for citizens to engage in meaningful participation.

This is not the fault of either the community or you as politicians – it is the result of the political systems we have designed. But the fundamental problem with this way of making public decisions is that it is responsive to the wrong input. Decisions are made responding to public opinion and not to public judgment. (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 44)

The Swedish handbooks also draw attention to larger societal changes that have increased the need for participation.

The increased individualization due to societal changes […] has increased people’s trust in their own abilities and decreased their trust in authorities and established elites’ interests to handle local problems. (SKL, Citation2019a, pp. 7-8)

To address the lack of meaningful participation, the handbooks frame public judgement as the solution. “Can we get citizens to think in depth and not act on self-interest and opinion? Yes. We are confident we can help by creating incentives for citizens to explore issues […] with the purpose of having them reach a point where a real mix of people of all ages and backgrounds can stand behind a common ground position” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 30). The handbooks do not frame the solution in terms of general models for participation, but rather as approaches that can be contextualized to fit with the governance issue at hand.

The handbooks make their case for participation by way of contrast to representative democracy: “Voting for representatives and proposals is one mechanism, but we start from the position that we need to do more” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 18). Yet, the handbooks also acknowledge that public participation is not the only solution to governance problems: “The best solution to political inclusion is franchise and political equality” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 14).

Framing Knowledge

The handbooks problematise the lack of inclusion of citizens’ knowledge in planning processes. The lack of opportunities for meaningful participation result in citizens who are prone to opinions rather than reasoned judgement: “Think back to past attempts to involve the community and ask how many people supported their argument with facts or showed they had considered a range of perspectives” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 39). According to the handbooks, this problem is not intrinsic to citizens, but located in the political system.

To solve the problem of lack of meaningful participation, the handbooks suggest recasting relations of authority in the planning process. The intention is to construct possibilities for public participation. Instead of the tendency to exclude citizens’ knowledge from policymaking, the handbooks suggest that politicians ought to question their preference for top-down decision making.

It is not citizens’ dialogue [participation] when a decision is already taken or if there is a clear position and the elected officials are not open to change their position, but just there to inform citizens about the decision. (SKL, Citation2019a, p. 10)

Yet, to open policy making for participation ought not, according to the handbooks, mean that politicians give up their own authority.

In this case, clearly stating that the Government has made the decision that [for example] a Gender Equality Bill is being developed draws the discussion on the decision to be made away from “should we have a Gender Equality Bill?” This focuses the discussion and takes political attention away from the process and its participants. (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 105)

Recasting relations of authority opens the process to the entry of a particular kind of governance expert: the “Facilitator – one who contributes structure and processes so groups are able to function effectively and make high quality decisions” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 220). “Without a facilitator, […] meetings can become unproductive or create their own new problems” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 166).

If a participatory process is facilitated, it is, according to the handbooks, capable of overcoming the tendency for opinion and polarisation to replace deliberation and judgement. The expertise of a facilitator will enable citizens to contribute with their knowledge in planning processes: “You will be pleasantly surprised at how everyday people can understand quite technical information when they are given the time to understand it properly. They also often ask very good questions about the everyday work that helps the organization to think differently about an “old” problem” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 70). The expertise of facilitators enables citizens to increase their capability to think critically and reflect on their biases.

[…] Nobody becomes an expert in dialogue immediately, neither organizations nor individuals. Since the need for dialogue will not decrease, we believe that municipalities need to continue to build dialogue competence, also for conflictual issues. (SKL, Citation2019b, p. 15)

The handbooks suggest that different kinds of knowledge can be included in governance processes and hold varying degrees of authority in different stages of a decision-making process. Expertise in facilitation ought to be influential in setting up and implementing a participatory process: “The facilitator’s role begins with contributing to the design of the process. They should be an advisor on all the key design decisions including the number of days, number of participants and even the remit” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 167). With the support of facilitators, and within the boundaries set by political authorities, the handbooks suggest that citizens ought to be empowered through a participatory process that allows their knowledge to be included.

Framing Ethics

The participation handbooks do not elaborate explicitly on ethical issues. Instead, they presume that public participation is ethically desirable given its egalitarian, communicative and consensual character. Even so, some of the problems discussed in the guidance have to do with the ethics of participation. The handbooks suggest that an ethical risk is that facilitators and decision makers might manipulate processes towards certain outcomes under the cover of token participation.

The feeling of being led – you should be extremely careful around any perception that the group is being led to a certain decision by either you (the facilitator) or the decision maker or anyone else. (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 202)

The solution offered to this problem is, first, that political authorities ought to clarify the boundaries for citizens’ influence: “Is it possible to influence the issue? Are we as decision makers open to be influenced? If the answer is no on any of these questions, citizens’ dialogue should not take place” (SKL, Citation2019a, p. 54). Second, the handbooks frame neutral and transparent facilitators as part of the solution to token participation.

In order to be trustworthy when opening up an issue, there is a need for those who work with the citizens’ dialogue to be neutral. Neutrality is defined as impartial, non-valuing and compassionate. Neutrality is a role and a tool that workers in municipalities can be trained to assume and use. Nevertheless, it can be difficult and requires conscious practice. (SKL, Citation2019b, p. 13)

According to the handbooks, impartial, non-valuing facilitators ought to be transparent about the choices they make. “For transparency, facilitators should always make clear why a speaker is there i.e. [sic] who selected them and what their background is” (UNDEF, Citation2018, p. 182).

Additionally, the handbooks frame an ethical problem around “the usual suspects” in participation. The handbooks argue that it is problematic that certain groups of citizens are participating less than others. The solution offered is to include those who rarely participate. “No single citizens’ dialogue will be able to include all citizens. Instead, a purposeful work is needed to reach those who the municipality wishes to meet. It is about inviting, but even more about meeting citizens where they are” (SKL, Citation2019b, p. 31).

Discussion: Scripting the Performance of Authority

In this closing section, we theorise the findings from the analysis of nudging and participation handbooks as two alternative scripts for the performance of authority in the planning of urban sustainability. We leave the metaphor of frame, which helped us understand the internal logic of the two governance strategies, and now use the metaphor of script, to better understand the handbooks and the roles of authority they allocate to experts, citizens and planners. We thereby understand the nudging and participation handbooks as scripts intended to influence the performance of authority by providing justifications for authority positions; i.e. by “making up” planning actors (Cashmore et al., Citation2015). The government agencies have published these scripts for planners, who are supposed to use them in their mediation of different knowledge claims.

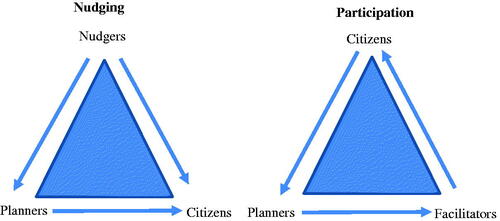

Seen in this way, the identified frames in the result section offer two alternative scripts, defining the roles of citizens, experts and planners in urban planning. The plays scripted by nudging and participation offer distinct plot lines, but also share some basic dramaturgical principles ().

Nudging’s script for performance of authority casts experts in behavioural science in positions of authority as “nudgers.” The script constructs expert authority by contrasting it with citizens’ and planners’ lack of knowledge about changing “unsustainable” behaviour. Citizens are positioned as being prone to behaviour that is irrational, i.e., against their own interest; planners are constructed as being inclined to design inefficient interventions based on flawed assumptions about citizens’ rationality. Thereby, experts in behavioural science are placed at the top of a pyramid, in positions of authority to experiment on citizens with the assistance of planners. The answer to whose knowledge counts is that planners and citizens should trust the expertise of nudgers when it comes to how to change “unsustainable” behaviour.

As “reviewers” of the nudge script, we see a clear and unambiguous story line developing around the nudger as the hero with capacity to correct planning failures. To strengthen the role of the lead actor, citizens and planners are delegated to supporting roles. The script places the nudgers in positions of authority by undermining the authority of citizens and planners. Hence, the nudging script simply absolves the tension between the inequality of expertise and the equality of democracy by favouring expert authority rather than the allegedly flawed judgement of citizens and the limited knowledge of planners.

In contrast, the script of participation emphasises citizens’ authority. A problem is constructed around citizens who are disenfranchised and prone to opinion rather than deliberate judgment due to top-down decision-making. The solution is to design inclusive planning processes that provide conducive conditions for public deliberation. This script places the citizens at a position at the top of the pyramid of authority. That position is underpinned by the role of planners who commission (or act as) facilitators in the planning process. Because of their expertise, facilitators are placed in a position of authority over the process of participation. Through – and bounded by – this process, citizens are cast in a position where their knowledge counts, a position from where they can influence the outcome of decisions through public participation.

The participation script has a much more complex story line than the nudging script. It aspires to change the political cultures that lead citizens to be prone to opinion rather than measured judgements. The key is to invite citizens to meaningful participation – to strengthen citizens’ authority and thereby restore trust in democracy. An interesting plot twist is that citizens are placed in positions of authority by casting facilitators as experts in participation. Paradoxically, the authority of the facilitator, in the end, rests on an assumption of inequality of experiences and skills. The tension between the principles of inequality and equality is thereby not absolved in the script but present below the surface.

Our findings, theorized as scripts, clarify how nudging and participation carry different ideas about the ethical question of whose knowledge counts (see Häußermann, Citation2020; John et al., Citation2011; Pedwell, Citation2017). Nudging assumes inequality in knowledge, and suggests a planning strategy based on an unambiguous authorization of experts in behavioural insights. In contrast, participation assumes equality and suggests that well-facilitated participatory processes can strengthen citizens’ authority. Despite this basic difference, both scripts – somewhat paradoxically given participation’s preference for equality – provide experts (the nudger and the facilitator respectively) with authority. Even so, the nudgers and the facilitators make different kinds of claims to authority. In nudging, experts are constructed as authorities based on substantive knowledge, while facilitators mainly aspire to provide procedural knowledge. In participation handbooks, the answer to the ethical question of expert authority is to make facilitators accountable to planners and citizens, whereas the nudging handbooks’ strong emphasis on the role of nudgers leaves the question of who these experts are accountable to largely un-answered.

Nudging and participation can be linked to two ideal-typical approaches to planning: nudging can be understood as related to expert-driven rational planning (Faludi, Citation1973) while participation shares similarities with the competing ideas of communicative planning (Forester, Citation1999; Healey, Citation1997; Innes & Booher, Citation2018). Our findings thereby provide insights into how intergovernmental and Swedish agencies use ideas related to rational and communicative planning to structure the field of action for planning actors.

Nudging reflects how contemporary advocates of rational planning have nuanced their aspirations for rationality. Hence, the behavioural economic and psychological theories that inform nudging assume that human rationality is bounded: i.e., humans are not always adhering to means-end-rationality. Relaxing the rationality assumption certainly holds potential for strengthening practical applications of rational planning. Even so, nudging also reflects a remaining flaw in this planning approach: the assumption of bounded rationality is only applied to citizens’ decision making, while behavioural insights experts are still assumed to be means-end-rational in the strict sense (see Lodge & Wegrich, Citation2016 on the “rationality paradox of nudge”). That experts can exist on an island of rationality in a sea of bounded rationality is unlikely given the decades of research showing that social interactions in planning practice cannot be assumed to be means-end-rational in the conventional meaning of the word (see Flyvbjerg, Citation2004).

Our analysis of participation handbooks provides insights into how intergovernmental and Swedish agencies use ideas related to communicative planning theory. The analysis shows how communicative planning draws attention to the important task of improving communication between planning actors. The ideas of communicative planning carry potential for bringing to the fore the contested character of knowledge claims in planning, and provide suggestions for how planning processes can be designed to make socially acceptable decisions.

Even so, the analysis of handbooks confirms that the uneasy relationship between hierarchical power and communicative planning might provide pitfalls in practice (Westin, Citation2021). This is evident when the handbooks construct facilitators as neutral, even when they are in positions of authority. The issue of neutrality has long been debated in planning (Westin, Citation2021). One outspoken ideal (see Susskind’s story in Forester, Citation2013) is that in which the facilitator acknowledges the impossibility of being neutral, but counters with non-partisanship and transparency. This ideal is not easily performed in practice, but Lawrence Susskind’s developed understanding of neutrality is helpful for facilitators (Forester, Citation2013). Indeed, the conventional meaning of neutrality is far too simplistic to capture the complexity of facilitation practice (Forester, Citation2013), and the participation handbooks would do well to update this. If citizens see through the neutrality charades in the handbooks, practical applications of communicative planning might just – as unreflective application of behavioural theories – reinforce the spiral of distrust between experts and citizens.

We conclude that a literal performance of authority according to either the nudging or the participation handbooks, is bound to lead to a problematic planning of urban sustainability. In our understanding, the pursuit of sustainability involves a tension between professional experts’ knowledge and citizens’ knowledge. On the one hand, complex democracies require a division of labour, including a multitude of fields of expertise making necessary contributions to the planning of society. On the other hand, a democratic transition towards sustainability demands citizens’ participation. Looking at the scripts we have distilled, we see that nudging seeks to absolve the tension between experts’ and citizens’ knowledge, while the tension is present under the surface in the participation script. Thereby, none of the scripts explicates how the tension between different, and equally justified, sources of authority is inherent to sustainability planning.

Finally, this inquiry into handbooks certainly casts light on the attempts by intergovernmental and Swedish authorities to structure the field of action in urban planning. Even so, this light does not necessarily reach the situated practices of planning. Hence, the findings about how nudging and participation script the performance of authority, should be complemented by future research into how the scripts are actually performed in the practices of urban planning.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Anke Fischer, Wiebren Boonstra, Jacob Strandell, the journal editors and the anonymous reviewers for useful feedback on previous versions of this paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martin Westin

Martin Westin holds a PhD in Environmental Communication. His work takes shape in the intersection between planning theory and practice. He conducts research into participatory planning and facilitates deliberation on wicked problems.

Sofie Joosse

Sofie Joosse is a researcher in Environmental Communication at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala. She holds a PhD in human geography. Currently she is investigating sustainability, everyday practices and governance.

Notes

1 All selected publications are freely available from the websites of the respective organizations.

References

- Austin, J. (1975). How to do things with words. Harvard University Press.

- Campbell, H., Tait, M., & Watkins, C. (2014). Is there space for better planning in a neoliberal world? Implications for planning practice and theory. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X13514614

- Carlsson, F., Gravert, C., Johansson-Stenman, O., & Kurz, V. (2019). Grön nudge – att designa och utvärdera. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:naturvardsverket:diva-8484

- Cashmore, M., Richardson, T., Rozema, J., & Lyhne, I. (2015). Environmental governance through guidance: The “making up” of expert practitioners. Geoforum, 62, 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.03.011

- Connelly, S., & Richardson, T. (2004). Exclusion: The necessary difference between ideal and practical consensus. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 47(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964056042000189772

- Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and pluralism in planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31(4), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366508978187

- Eyal, G. (2019). The crisis of expertise (1st ed.). Polity.

- Faludi, A. (1973). Planning theory. Pergamon Press.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Phronetic planning research: Theoretical and methodological reflections. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(3), 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000250195

- Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. MIT Press.

- Forester, J. (2013). Planning in the face of conflict: The surprising possibilities of facilitative leadership. American Planning Association.

- Forester, J. (2020). Five generations of theory–practice tensions: Enriching socio-ecological practice research. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 2(1), 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-019-00033-3

- Forst, R. (2015). Noumenal power. Journal of Political Philosophy, 23(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12046

- Fung, A. (2015). Putting the public back into governance: The challenges of citizen participation and its future. Public Administration Review, 75(4), 513–522. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12361

- Goffman, E. (1973). The presentation of self in everyday life. Overlook Press.

- Gravert, C., & Carlsson, F. (2019). Nudge som miljöekonomiskt styrmedel – Att designa och utvärdera. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:naturvardsverket:diva-8543

- Halbe, J., Holtz, G., & Ruutu, S. (2020). Participatory modeling for transition governance: Linking methods to process phases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 35, 60–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.01.008

- Haugaard, M. (2018). What is authority? Journal of Classical Sociology, 18(2), 104–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X17723737

- Häußermann, J. J. (2020). Nudging and participation: A contractualist approach to behavioural policy. Philosophy of Management, 19(1), 24–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40926-019-00117-w

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies. Macmillan.

- Healey, P. (2012). Re-enchanting democracy as a mode of governance. Critical Policy Studies, 6(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2012.659880

- Innes, J. E. (1995). Planning theory’s emerging paradigm: Communicative action and interactive practice. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 14(3), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9501400307

- Innes, J. E. (1998). Information in communicative planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 64(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944369808975956

- Innes, J. E., & Booher, D. E. (2018). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315147949

- John, P., Cotterill, S., Liu, H., Richardson, L., Moseley, A., Nomura, H., Smith, G., Stoker, G., & Wales, C. (2011). Nudge, nudge, think, think: Using experiments to change civic behaviour. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781849662284

- Karl, H. A., Susskind, L. E., & Wallace, K. H. (2007). A dialogue, not a diatribe: Effective integration of science and policy through joint fact finding. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 49(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.3200/ENVT.49.1.20-34

- Kühn, M. (2021). Agonistic planning theory revisited: The planner’s role in dealing with conflict. Planning Theory, 20(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095220953201

- Lehner, M., Mont, O., & Heiskanen, E. (2016). Nudging – A promising tool for sustainable consumption behaviour? Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.086

- Lodge, M., & Wegrich, K. (2016). The rationality paradox of nudge: Rational tools of government in a world of bounded rationality. Law & Policy, 38(3), 250–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12056

- Mattila, H. (2020). Habermas revisited: Resurrecting the contested roots of communicative planning theory. Progress in Planning, 141, 100431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2019.04.001

- Mik-Meyer, N., & Haugaard, M. (2020). The performance of citizen’s and organisational authority. Journal of Classical Sociology, 20(4), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X19860111

- Mont, O., Lehner, M., Heiskanen, E., & Sverige, N. (2014). Nudging: Ett verktyg för hållbara beteenden? [Nudging: A tool for sustainable behaviour?]. Naturvårdsverket.

- Moore, A. (2017). Critical elitism. Cambridge University Press.

- Nichols, T. (2017). The death of expertise: The campaign against established knowledge and why it matters. Oxford University Press.

- OECD (2019). Tools and ethics for applied behavioural insights: The basic toolkit. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/regreform/tools-and-ethics-for-applied-behavioural-insights-the-basic-toolkit-9ea76a8f-en.htm

- Pedwell, C. (2017). Habit and the politics of social change: A comparison of nudge theory and pragmatist philosophy. Body & Society, 23(4), 59–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X17734619

- Puustinen, S., Mäntysalo, R., Hytönen, J., & Jarenko, K. (2017). The “deliberative bureaucrat”: Deliberative democracy and institutional trust in the jurisdiction of the Finnish planner. Planning Theory & Practice, 18(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2016.1245437

- Rein, M., & Schön, D. (1996). Frame-critical policy analysis and frame-reflective policy practice. Knowledge and Policy, 9(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02832235

- Sager, T. (2016). Activist planning: A response to the woes of neo-liberalism? European Planning Studies, 24(7), 1262–1280. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1168784

- Sager, T. (2018). Communicative planning. In M. Gunder, A. Madanipour, & V. Watson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of planning theory (Vol. 2018, pp. 93–104). Routledge.

- Sager, T. (2020). Populists and planners: “We are the people. Who are you?”. Planning Theory, 19(1), 80–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095219864692

- Schubert, C. (2017). Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical? Ecological Economics, 132, 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.11.009

- SKL. (2019a). Medborgardialog i styrning. https://webbutik.skl.se/sv/artiklar/medborgardialog-i-styrning.html

- SKL. (2019b). Medborgardialog i komplexa frågor: Erfarenheter från utvecklingsarbete 2015-2018. Sveriges kommuner och landsting. https://webbutik.skl.se/sv/artiklar/medborgardialog-i-komplexa-fragor.html

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- UNDEF. (2018). Enabling national initiatives to take democracy beyond elections. UNDEF. https://www.fide.eu/research-and-documentation/blog-post-title-two-lrgrb

- Van Hulst, M., & Yanow, D. (2016). From policy “frames” to “framing” theorizing a more dynamic, political approach. The American Review of Public Administration, 46(1), 92–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014533142

- Warren, M. E. (1996). Deliberative democracy and authority. American Political Science Review, 90(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082797

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. University of California Press.

- Westin, M. (2021). The framing of power in communicative planning theory: Analysing the work of John Forester, Patsy Healey and Judith Innes. Planning Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952211043219