Abstract

Consistent with ideas of urban shrinkage, many town centres have experienced years of increasing vacancy due to the loss of brand name retailers, and a crisis has emerged as conditions have deteriorated. This paper makes conceptual and practical linkages to the related “smart-decline”/“rightsizing” literature to provide insights regarding the challenges of town centre shrinkage and the strategies and governance structures required to realise the opportunities arising. These conceptions/ideas are applied through case study analysis, with the findings suggesting that adopting “smart-decline”/“rightsizing” concepts/ideas provides an important new lens for future town centre research.

Introduction

Over recent decades, the decentralisation of retail has generated serious concerns regarding the contemporary relevance of commercial town centre activities (Hospers, Citation2017; Robertson, Citation2001). The Covid-19 pandemic has both exacerbated and accelerated the challenges of retail decline. Meanwhile, against the backdrop of international literature suggesting a generalised oversupply of retail space, empty former retail units have become a pervasive feature of urban spaces (Guimarães, Citation2019). Given the negative feedback loops created by vacant properties and physical blight from a lack of maintenance, there is a pressing need to stabilize this “spiral of decay”; to ensure more “sustainable” levels of commercial offer (Powe, Citation2020, p. 245; Schilling & Logan, Citation2008, pp. 453–454).

When faced with retail decentralisation, town centres in the UK context have traditionally attempted growth-oriented retail/leisure property-led master planning solutions to boost their competitiveness as retail centres. Efforts mimicking the design of shopping centres have focussed on attracting brand name retailers that “anchor” and “claw back” trade – whilst benefiting pre-existing businesses – via the process of “linked trips” (Powe, Citation2012; Thomas & Bromley, Citation2003). But, given the context of retail space oversupply, this approach would appear no longer valid (Powe, Citation2020). Whilst there are plenty of other ideas as to how to revive the fortunes of town centres, previous conceptualisation has been limited. These challenges, however, are not unique to declining town centres. More broadly, ideas of urban shrinkage have been subject to much debate: drawing from this research has potential to enhance the conceptual understanding of town centre decline.

Ideas of “smart-decline”/“rightsizing” (subsequently shortened to smart-decline) refer to the need to plan for place-continuation in the context of shrinkage (Hollander & Németh, Citation2011). Place-continuation within town centres may mean maintaining their core purpose, which is their role as a central multifunctional visitor/community attraction (Powe, Citation2020; Rhodes, Citation2019). For local actors continuation may also imply maintaining the identity of their “community of place” (Powe et al., Citation2022). Some town centres will be sufficiently blessed that place continuation is not threatened; places which, perhaps with some public support, can reorient the visitor/community attraction for their whole centre, so that dependence on brand name retailing can be reduced without shrinking as an attraction (Powe & Hart, Citation2017). Likewise, at the other end of the spectrum, some town centres may face location obsolescence (Hughes & Jackson, Citation2015). But many town centres find themselves located between these polar points, having potential for a continuation of their core purpose/identity, albeit at a smaller scale.

Focusing on strategies to support smart-decline, the literature highlights the importance of bottom-up forces in place change – especially as a bespoke response is needed to meet the specific economic, social, political, and institutional challenges and contexts, within which place shrinkage is located (Béal et al., Citation2019; Hospers, Citation2017; Rhodes, Citation2019). Top-down market-led approaches tend to focus on replacement, rather than dealing with the local nuances and challenges associated with centre shrinkage (Hackworth, Citation2015; Hollander & Németh, Citation2011). Unlike the heavily planned environments of shopping centres, town centres are more complex, multi-functional and less coordinated in their activities. As a result, the diversity of actors and multi-functional uses supports the potential for town centres to adapt and reorient themselves (McGreevy & Wilson, Citation2017; Powe, Citation2020). Such forces might provide a form of self-organisation – the positive feedback from individual/commercial actions without central intent, perhaps encouraged through policy, but without central control (Rauws, Citation2016). Self-emergence can also be supported by efforts driven by a local consensus for town centre improvement. This can be coordinated through local government and/or self-governance organisations, where the latter have a degree of independence from local government, work to a collective intent and “actively try to establish a change … by means of cooperation” (Rauws, Citation2016, p. 345).

Given the context of an oversupply of commercial space within town centres, attention logically focuses on self-organisation by property owners. The few studies that exist suggest these actors tend to be relatively inactive, where strategic engagement with town centre regeneration is more the exception than the rule (Håkansson & Lagin, Citation2015). The smart-decline literature suggests a key motivation for public/community ownership is the danger that property owner acquisition strategies are “in conflict with community interests” (Mallach, Citation2010, p. 14). Common to these management strategies is a lack of property investment, as the UK policy literature suggests that retail property owners have “varying interest and involvement,” are asking for unrealistic rents, and asset ownership is often opaque (HCLGC, Citation2019, p. 12). Overcoming these negative feedback mechanisms of self-organisation has been a key challenge noted within the smart-decline literature.

In the context of decline, Powe et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate how positive support from self-governance can be a more important driver than self-organisation following place shrinkage. Although town centre management (TCM) and business improvement districts (BIDs) can provide essential coordinating activities, they often focus on issues of day-to-day management, rather than facilitating the repurposing of poorly maintained and redundant buildings (Espinosa & Hernandez, Citation2016; Ward & Cook, Citation2017). Although local authorities have often taken a lead on town centre regeneration, they may be constrained by the need to remain neutral across all centres (Guimarães, Citation2019); are unable to provide locally embedded self-governance (Rauws, Citation2016); lack sufficient flexibility to make quick decisions; and are inherently political in nature – which may constrain (or even conflict with) long-term smart-decline efforts (Otsuka & Reeve, Citation2007). In the context of an oversupply of retail space and resultant physical blight, something else is required if the situation is to be stabilised.

Experience in the USA highlights the crucial supportive role of the non-profit sector in developing the required bottom-up approach to change (Hummel, Citation2015). Community Development Corporations (CDCs) are locally embedded self-governance organisations, originating in the 1960s and have been the subject to sustained research (Yin, Citation1998). CDCs have played a crucial role within smart-decline in America, often operating at the neighbourhood level. Many CDCs “provide on-the-ground capacity that the city government cannot replicate” and are a significant counteracting force in the context of decline (Fujii, Citation2016, p. 301). CDCs have similarities with Community Enterprises (CEs) that have been developed within both UK and Dutch contexts, although these have been researched less extensively than CDCs (Varady et al., Citation2015). CEs are self-governing, not-for-profit organisations, owned and/or managed to some degree by community members, that provide a “combination of professional skills, entrepreneurial underpinnings, and a focus on their ‘community of place’” (Powe, Citation2019, p. 625). CEs are underpinned by successful social enterprise, but in practice their activities often extend into providing expertise and governance support for wider community activities (Powe, Citation2019). The self-governing nature of CEs ensures they have sufficient inbuilt flexibility to adapt to different circumstances and provide the necessary bespoke response to specific town centre challenges.

This paper explores the potential of applying smart-decline concepts/ideas in the context of shrinking town centres. Through detailed case study research in the North-East of England, the research asks how concepts of smart-decline offer insights into the experiences of struggling town centres (Research Question 1); and how self-governance structures can be enhanced to develop built environment strategies to support such “smart” approaches to shrinkage (Research Question 2). Whilst Hollander (Citation2018) and Hollander and Hartt (Citation2019) provide some interesting speculative suggestions related to the application of smart-decline to downtowns, this is the first detailed study to formally explore the application of the concepts/ideas to these central places. Whilst the link between CDCs and CEs has previously been made, the roles of the organisations within the town centre context have been neglected and may have potential to help address the built environment challenges emerging.

Strategies for Town Centre Smart-Decline

Urban shrinkage applies to situations where there have been years of decline driven by underlying structural change and leading to a crisis (Hummel, Citation2015). Whilst the smart-decline literature focuses mainly on places suffering from population decline, this paper engages instead with the continued net-loss of commercial operators within town centres and the resultant physical blight from empty and unmaintained properties. Net-loss of commercial operators in town centres can result from wider urban decline (Hollander & Hartt, Citation2019), but this paper focuses on the more generic challenges emerging from externally driven brand names closures. Following years of increasing vacancy, a crisis emerges as properties are not maintained, conditions deteriorate, and further businesses leave (Powe, Citation2020).

For local actors, developing policy responses to urban shrinkage involves a process of acceptance (Hospers, Citation2014). Perhaps initially the policy response is to do nothing, where local actors hope town centre decline will not last. According to Hospers (Citation2014), the second stage is acceptance of the problem, where the response is to develop growth-based strategies. In the context of town centres, previous responses to decline have focused on maintaining competitiveness through retail/leisure property-led growth. The rightsizing literature contains similar examples, where, in the context of an oversupply of housing, growth-based strategies have led to further housing being built (Hackworth, Citation2015). Building more housing or retail space in the context of oversupply is not addressing the underlying problem and can make the situation much worse, especially, for example, if new retail is built in out-of-centre locations (Powe, Citation2020; Rhodes & Russo, Citation2013). Whilst retail development within town centres may no longer be viable, chasing external finance for demolition and replacement uses is not conducive to the continuation of the core purpose/identity of these central places. Developing smart-decline policies implies a different way of thinking. There needs to be an acceptance by local actors, not only of the problem, but that the urban area considered will not grow back to its “former glory” (Hollander, Citation2018, p. 4). This third stage of acceptance involves policies to stabilize the dysfunctional market rather than growth. The fourth stage involves focusing on opportunities for place improvement through shrinkage.

The resultant smart-decline strategy requires planning for a consolidated and reoriented town centre, still a visitor/community attraction, but less dependent on brand names, and the creation of replacement uses that are complementary to the consolidated visitor/community attraction. Whilst an opportunist approach may still be required, growth possibilities must be focused within the centre itself. Struggling areas within town centres must not be neglected if the dysfunctional market is to be stabilized (Rhodes & Russo, Citation2013).

The smart-decline literature has tended to focus on built environment strategies: this focus is taken here (Hummel, Citation2015). Whilst reducing the density of housing through the demolition of vacant properties can be beneficial for the remaining residents, this is not likely to be the case for commercial properties in town centres (Rhodes, Citation2019). Indeed, Hollander (Citation2018, p. 82) questions the efficacy of demolition, where “some level of intensity [is required], in the face of decline.” Maintaining a high density of visitor attractions “will encourage the footfall upon which most stores depend for trade” (Robertson, Citation2001, p. 30). Furthermore, conserving buildings can help maintain the pre-existing urban form, help support the continuation of place identity/distinctiveness and the cultural/heritage value of properties (Bullen & Love, Citation2010; Hollander & Németh, Citation2011). Whilst much of the smart-decline literature has focused on the demolition of vacant properties, achieving these aims requires town centre policy to focus more on rehabilitation and adaptive reuse. This approach will help support place continuation, density of offer and place quality. Patience is needed where there are likely to be pressures for growth-orientated quicker fixes that do not sufficiently consider the potential for the continuation of visitor/community attraction uses (Heil, Citation2018; Robertson, Citation2001). The result is a flexible incremental process that will take time to implement, is locally situated and heterogenous in its application between places (Béal et al., Citation2019).

Developing a Supportive Governance

Whilst local government support is essential, self-governance organisations can be crucial within smart-decline processes (Powe et al., Citation2022). Where a local authority is particularly active within a town centre, there may be an overlap with potential self-governance activities. However, self-governance provides its own niche and contribution. Organisations such as TCMs, BIDs, CDC, CEs or other forms of strategic alliance can form a consensual approach and become intermediaries between stakeholders. Self-governance can provide a source of knowledge, a translator for the local communities, and/or a negotiator/mediator between actors (Heil, Citation2018; Powe, Citation2019). These boundary skills can help to provide a long-term professional “anchor” to support voluntary activities, help understanding of regulations and provide the necessary support to help manage the efforts of local volunteers (Powe, Citation2019). Examples that would support the town centre include events, awareness building, and place ambassadors, all of which can be supported through the boundary work of TCMs, BIDs, CDCs and CEs (Stubbs et al., Citation2002). Building on the CDC literature, this paper considers a further extension of such local governance roles to developing property-level built environment strategies to support town centre smart-decline.

Built Environment Strategies to Support Smart-Decline Processes

Challenged by an oversupply of commercial space, attention naturally focuses on the owners of the properties and conflicts between their property management practices and town centre interests. Whilst persuasion and enforcement may be effective, this can be a time-consuming process, which may not deliver the required changes. An alternative approach is direct ownership. In a similar way to the management of shopping centres, ownership provides control over property maintenance, design, rent levels, efforts to find tenants and the contribution of the properties’ uses to the town centre commercial mix (Powe, Citation2020). More generally, public/community property management can lead to more strategic and proactive ownership, where there is a drive to convert “urban blight” into assets for the local community (Schilling & Logan, Citation2008).

Implicit within public/community ownership is what Needham (Citation2007) referred to as the “two-hat problem” or, in the context of the CDC literature, the “double bottom line” problem (Bratt & Rohe, Citation2007). Ownership provides control over the use and maintenance of the property for the benefit of the town centre (“Hat Number 1”); however, management choices affect the financial return on the property which needs to at least break even (“Hat Number 2”). More generally, property management is a high-risk strategy within town centres, as there is the need to both purchase and service (refit/regenerate) the property for new uses. In the context of high risk and low potential return, cost recovery for these efforts remains a challenge. Balancing the “two-hats” requires alignment with local economic realities, which will involve focusing on areas that have not yet reached the “point of no return” and still have a degree of commercial potential (Rhodes, Citation2019, p. 221). This is not a policy for the most challenged areas. Even then, “Hat Number 2” may only be achievable if supported through grants, perhaps for adaptive reuse, where the charitable nature of CEs may bring in external public/charitable funding not otherwise available to a town centre (Powe, Citation2019). CDCs and CEs must be underpinned by a long-term sustainable business model (Fujii, Citation2016; Powe, Citation2019; Yin, Citation1998). Such business models enable non-profit organisations to both initiate and enhance local activity. In the case of CDCs, this has been through the provision of affordable housing.

Methods

The main case study research was undertaken in the towns of Stockton-on-Tees and Bishop Auckland in the North-East of England, where town centres are experiencing significant numbers of empty units due to brand name loss. This case study material provides an opportunity to explore how concepts of smart-decline can be related to the experiences of struggling centres (Research Question 1). The two case studies are outlined in detail within the next section.

Whilst these case study communities are insightful to Research Question 1, neither have a CE or other similar organisation engaging in built environment strategies. To explore how self-governance structures can enhance such strategies (Research Question 2), further case study material was required. Also located within the North-East of England is the County of Northumberland, within which some towns and large villages were encouraged in the 1990s to develop CEs. Whilst the CEs in Northumberland were engaged in whole place rather than specifically town centre regeneration, their work was particularly focused on the built environment and community development. Building on Powe’s (Citation2019) in-depth study of CEs within this county, new interviews with key actors were undertaken to explore specifically how CEs could support struggling town centres.

Twenty-one interviews were undertaken in 2020–2021 across the cases of Stockton, Bishop Auckland and Northumberland. This included actors working for the local authorities (community development, statutory planning, building control and regeneration); local councillors; directors of CEs (successful and unsuccessful); a chair of a clustered group of retailers; key actors from three other types of local self-government organisation; a coordinator of a town centre area action zone; as well as someone from a national charity supporting social enterprise activity. The interviews were semi-structured and, where possible, were recorded and transcribed. One of the authors has followed the progress in Stockton, Bishop Auckland and CEs in Northumberland over several years and, during this time, has benefited from insightful informal conversations that also fed into this study. The analysis is supported by detailed property surveys of ground-level visitor attraction uses in both Stockton and Bishop Auckland town centres. Given the controversial and sensitive nature of some of the comments made, sources of the comments are sometimes kept confidential.

Case Studies

Consistent with ideas of smart-decline, Stockton and Bishop Auckland town centres were chosen as they both have potential for place-continuation within the context of shrinkage. Whilst Stockton provides perhaps an “exemplar” case of smart-decline, research in Bishop Auckland and Northumberland provide crucial counter-cases that illustrate the challenges of replication elsewhere. The focus is initially on Stockton and Bishop Auckland and Research Question 1. The findings from Northumberland are included within the last two analysis sections (“Developing a supportive governance” and “Built environment strategies in practice”), which focus on Research Question 2.

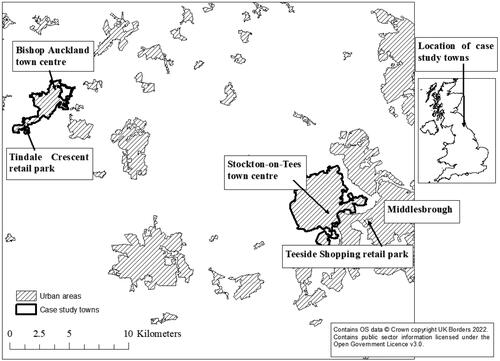

illustrates the context within which Bishop Auckland and Stockton operate. Bishop Auckland is on the urban fringe, with a rural area to the west, whereas Stockton is located close to the large urban area of Middlesbrough. Both Stockton and Bishop Auckland contain areas within the bottom 10% in the UK in terms of the 2019 index of multiple deprivation (https://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/iod_index.html). Whilst their place challenges clearly extend beyond their centres, unlike the troubled areas within many American shrinking cities, they do not experience similar racial issues. Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses the populations of Stockton and Bishop Auckland increased slightly. Indeed, the UK has few examples of population shrinkage, with, for example, no towns in the North-East of England declining in population between 2001 and 2011, according to the censuses (the city of Sunderland is the only exception with a marginal loss in population). Urban shrinkage discussed here relates purely to town centres.

Stockton-on-Tees (Population 83,000)

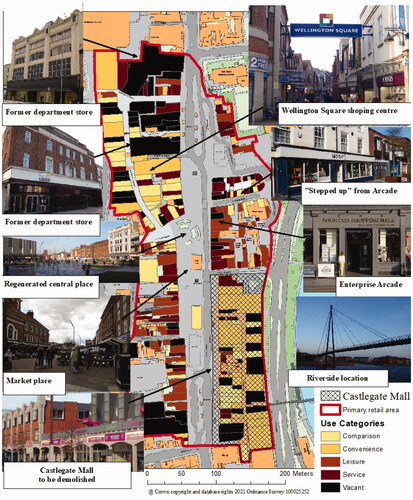

Located on the banks of the river Tees, Stockton High Street benefited from retail-property development in the 1970s through the development of Castlegate Mall (see ). Faced with severe competition from the larger town of Middlesbrough, and a free-standing large retail/leisure park (Teesside Shopping; location shown in ), parts of the centre were pedestrianised in the 1990s, and, following land assembly by the local authority (Stockton Borough Council), its competitiveness was further enhanced in 2001 through the private sector retail-oriented growth of a purpose-built pedestrianised shopping street including some large retail units (Wellington Square). provides an illustration of Stockton town centre in 2021.

With an increasing vacancy rate and proximity to other large retail centres, the local council embarked, in 2011, on a revival strategy involving public realm improvement (see the “Regenerated central place” in ), renovation of historic properties, the development of an incubation unit for small businesses (see “Enterprise Arcade” in ) and the adaptive reuse of an Art Deco theatre as an events venue just off the centre (completed in 2021). As a development officer suggested, there was an early acceptance that “we could no longer rely on national retailers and needed a much more even balance around independent retail and alternate reasons to visit a town.” Early acceptance proved to be insightful. As illustrated in , by 2018 the vacancy rate had been maintained at 14%, but between 2018 and 2021 further brand name stores closed (two were department stores; see ). Whilst a slight increase in independent stores had marginally compensated for this loss, by 2021 the overall vacancy rate had risen to 25%. Although many stores have closed in Stockton, and Middlesbrough centre is starting to struggle, brand name presence remains strong in the nearby Teesside shopping retail park (Teesside Park). Extending their previous efforts, the local authority accepted the need for town centre shrinkage and purchased both shopping centres (Castlegate and Wellington Square) (see ). At the time of writing in 2022 the council is embarking on a process of town centre consolidation, involving the demolition of the Castlegate Mall–with tenants encouraged to relocate to vacant properties within Wellington Square. As shown in , the demolition will reduce the supply of retail within the town centre, as well as open up views and attractive linkages, through a new urban park to the nearby river.

Table 1. Change in offer within Stockton-on-Tees (2018–2021).

Bishop Auckland (Population 24,000)

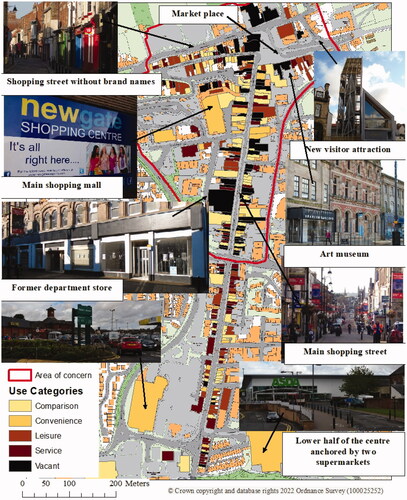

Whilst historically an important seat of power, as the home of the Bishop of Durham, Bishop Auckland expanded during the Victorian era as a service centre for the surrounding coalfield. Although the town centre survived the decline of the coalfield, it started to struggle in the 2000s. The response of the local authority (Durham County Council) was growth-oriented, facilitating and formally accepting plans for private sector retail-property development in 2008 on a brownfield site (now a car park at the top of ). Yet, partly due to the 2008 recession, this growth-oriented strategy failed to materialise. Against the advice of local planning staff, and in a context of an increasing oversupply of retail space, the local authority permitted significant out-of-town retail growth in the early 2010s (see location of Tindale Crescent retail park in ). Following this development, some key stores switched from the town centre to this out-of-town location. More generally, the 2010s and early 2020s have brought further significant decline. provides an illustration of Bishop Auckland town centre in 2021.

Anchored by two supermarkets with free car parking, the lower half of the town centre had a vacancy rate of only 11% in 2021 (see ). The focus of analysis is on the “area of concern” outlined in (upper half of the town centre). illustrates the process of brand name loss within the “area of concern.” As in Stockton, the growth of independents has to some extent compensated for the loss; however, by 2015 the vacancy rate in the “area of concern” had increased to 23%, then rising further to 33% by 2021. Despite suffering from brand name decline, the 2010s brought hope for alternative growth through cultural/leisure attractions around the marketplace. These attractions are being funded by a philanthropist who is spending over £200 m. In an extreme act of serendipity, he was initially attracted to the town by the edge-of-centre castle and the historic paintings contained within. The local authority has worked closely to support this growth-based strategy, for example, by developing a supporting masterplan and undertaking major environmental improvements to the town square. At the time of writing some of these leisure developments have been recently completed (renovation of the castle (completed); a new visitor centre with a viewing tower (completed); museums exhibiting mining art (completed); religious art museum (completed after 2021 survey). Others are not complete (such as the religious museum), or even started (a walled garden and upmarket hotels). These new visitor attractions have remained closed due to Covid-19, with great hopes for the summer of 2022. Whilst becoming a leisure/cultural destination will help significantly, as illustrated in , Bishop Auckland has a long high street and, as many interviewees suggested, there is “simply too much retail space” in the “area of concern.”

Table 2. Change in offer within Bishop Auckland town centre (2015–2021).

Constraining Nature of Town Centre Ownership

In the absence of external commercial investment, the onus is on the local private sector to develop an innovative/distinctive offer that attracts visitors to the town centre. Within Bishop Auckland, for example, an actor suggested many people still “dream … to own their own shop.” and illustrate a degree of independent growth is occurring in the case study towns. This is consistent with national trends, but with the caveat that the long-term effects of debt developed during the pandemic remain uncertain (Grimsey, Citation2021).

Consistent with the smart-decline literature (Mallach, Citation2010), frustrations regarding the nature of town centre ownership were widely expressed in the interviews. Inactive owners are constraining positive forces of self-organisation. Clearly some owners are maintaining and actively trying to fill vacant properties. However, there are clear examples of neglect within the case study centres. Town centre properties in these struggling towns are inexpensive: some properties have been speculatively purchased for resale should the market pick-up. In the meantime, such properties remain vacant and unmaintained. With some properties purchased through “shell” companies, questions were raised concerning owner priorities. Indeed, properties from various parts of the country are often sold together as a package, where regeneration efforts focus on the primary properties in the package with the highest potential premium and the owner never “gets to” investing in secondary properties. The focus on more viable locations is likely to further reinforce the difference between struggling and more successful retail centres. Given the disinvestment, as an interviewee suggested, “they just sit there for another 10–15 years.” Consistent with the UK policy literature, there was evidence of sticky rents, with several interviewees suggesting this reflected the need to maintain artificial “balance sheet values.” Rather than neglect, a process of maintenance and investment is required to better match the properties to local demand. As brand name loss leaves a legacy of large retail properties, some form of investment is required for new uses to be found.

Smart-Decline Strategies

Stockton council’s town centre shrinkage policy fits well with ideals of smart-decline. Having taken ownership of the two main shopping centres within the town, the consolidation strategy is to reduce retail supply within the centre by demolishing Castlegate Mall and finding replacement uses on the demolition site that complement the remaining centre. This 1972 shopping mall turned its back on the then heavily polluted river. Demolition will open the town centre to the river, where water quality has improved such that the river is now a leisure asset with its level maintained by a barrage. National Government will help fund an urban park on the former shopping mall site, improving the link to the attractive riverside location. New office development is also planned. These replacement uses continue the local authority’s town centre reorientation strategy, started in 2011, of “putting emphasis on quality of place, space for events and [now] access to the river” (development officer). Consistent with smart-decline strategies, the improvement in place quality is designed to support demand for commercial activity, and encourage the incremental process of self-organisation within the remaining centre (Schilling & Logan, Citation2008).

Whilst Hollander (Citation2018) questions the efficacy of demolition in the context of town centres, the edge-of-centre location of the shopping mall for demolition in Stockton does not challenge the density of offer within the consolidated centre. This process of smart-decline aims to “safeguard the traditional retail function … around consolidating the retail floorspace.” As the development officer continued, having a high “vacancy across an unsustainable number of units versus something more aligned with a national average vacancy rate across a much smaller area feels very different from a shopper/visitor perspective.” In the context of the smart-decline literature, this case example represents an “opportunity-based demolition” of a functioning shopping mall, which had a reasonably low vacancy rate prior to purchase (9% in 2018) (Hackworth, Citation2015, p. 775).

Purchasing two shopping centres and demolishing one to manage the supply of properties has involved terminating lease agreements. This process has so far been successful for some stores in Castlegate Mall, with often a preference for a smaller footplate. A failure to agree to relocation has meant that some brand names are no longer present in Stockton. At the time of writing the adjustment process is still ongoing. For some independent stores, Castlegate Mall’s pending closure has provided the “right time for them to shut-up shop.” However, as a solution to the oversupply of large retail stores in Wellington Square, unit subdivision has been undertaken by the local authority which has encouraged further independent traders to relocate from Castlegate Mall. Within the relatively modern Wellington Square development, subdivision was seen as less challenging than within other older large and vacant units in the town centre.

A development officer suggested that the long-term aim for Wellington Square, managed by a professional private company on behalf of the council, is to “fill it up and let it trade like a shopping centre does.” Brand name generated footfall will remain a key element for the success of the consolidated town centre, where the council is motivated by the importance of Wellington Square’s long-term success in supporting the remaining town centre (“Hat Number 1”) and the need to repay loans for the purchase of the two shopping centres (“Hat Number 2”). The revenue from a viable Wellington Square will be key to loan repayment. Vacancy is gradually improving through retail relocation from Castlegate Mall (demolition expected autumn 2022). Longer-term, combining the improved visitor experience of lower vacancy rates with improved environmental quality from opening-up the town centre to the river and forthcoming urban park (due for completion in 2025), will encourage positive feedback across the whole centre.

The Stockton case perhaps provides an exemplary example of town centre shrinkage, with timely acceptance of decline, an active local authority, long-term strong political buy-in to the vision and the possibilities arising from a shopping mall in an edge-of-centre location whose demolition opens-up an attractive riverside location without decreasing the density of offer. In Bishop Auckland a former brand name store has been converted into a much smaller retail unit with the remainder of the property being converted into flats. Planning permission has been granted for new housing to replace a former department store (see ), preserving the façade, but nothing has materialised due to viability issues. These remain the only known examples of retail property shrinkage in the main shopping street of Bishop Auckland.

Bishop Auckland provides an important illustration of the challenges of smart-decline following brand name retreat. Hollander and Hartt (Citation2019) illustrate how downtown decline within shrinking towns/cities is likely to occur in secondary edge-of-centre locations and how it is conducive to town centre consolidation. However, town centre decline through brand name retreat is likely to be more challenging as former large stores tend to be centrally located. In Bishop Auckland, the area around the marketplace (see ) currently provides an improving leisure destination. Close by is a shopping street without brand names (see ) within which distinctive independent businesses are emerging (supported by the local authority) that complement the improving leisure attraction. The Newgate Shopping Centre (see ) is becoming more multi-functional with the job centre soon to take up the remaining empty shop space. However, the central main shopping street within the “area of concern” is anchored by a declining number of brand names and a high vacancy rate. Shrinkage would mean the loss of part of this street to other uses, leading to a fragmentation of town centre offer rather than the consolidation proposed in Stockton. Whilst an interviewee explained how one of these properties would “effectively need to be demolished and rebuilt if it was to return to use,” this is not the case for most of these buildings. Indeed, a recent project has identified buildings of heritage importance, with a few being already listed for conservation. Whilst a dual economy may emerge (upper and lower centres), adaptive reuse within the main shopping street would at least enable a continuation of place identity/distinctiveness and the cultural/heritage value of properties. Whilst persuasion and threatened enforcement have been used to encourage owners to be more active, and support is available to encourage businesses to “step-up” to take on town centre properties, such efforts are proving insufficient to stabilize decline. Given the challenges faced, more is required. Whilst the local authority has obtained significant national funding from the Future High Streets and Towns Fund, at the time of writing, precisely how this funding is to be spent remains unclear. However, the focus of funding would appear to be on infrastructure improvement and the leisure destination growth strategy, rather than directly addressing the challenges of lack of maintenance and need for adaptive reuse in the former main shopping street.

Supportive Governance

Whilst local governments support all town centres within their administrative areas, there is a tendency in England to give more support to the main centres, such as Stockton and Bishop Auckland (Powe, Citation2019). In the UK, funding is highly centralised within national governments; however, local authorities can still provide a degree of their own funding, apply for national/charitable funding, have influence on key actors and provide a democratic mandate for their activities. Yet local authorities cannot regenerate town centres on their own; supportive self-governance is also needed.

Whilst the ideals of a local consensus/shared direction would significantly aid processes of smart-decline, achieving success is far from simple, and may take some time. Although the initial response to brand name loss in Bishop Auckland was further “lock-in” to the trajectory of brand name driven footfall, as the town centre continued to decline, key actors suggested that there was a gradual switch to feeling that: “everything that could possibly be done has been tried and, if it hasn’t, it’s not going to work.” A similar “doomed to fail” perspective has been experienced in shrinking American cities (McGovern, Citation2006, p. 533). A more “can do” attitude is required (Hospers, Citation2014; Powe, Citation2019). This can be supported through self-governance organisations. Working at the boundary between town centre actors and the local authority, interviewees reported that the BID in Stockton and a “town team” partnership in Bishop Auckland have been providing boundary work towards local acceptance of council policies as well as attempting to influence the local authority’s activities. They have also been directly supportive of activities to promote the town centre (marketing, events etc.). Whilst there have been some examples of small-scale social enterprise within both towns, there is no community-based social enterprise aiming to support the built environment.

Where local government is particularly active within a town centre, there is likely to be an overlap with potential CE built environment activities, where the self-governance nature of CEs provides a different approach to achieving the same goals and through boundary work can develop their own niche. Firstly, there are good reasons why many local authorities cannot be as active as Stockton council. Local authorities are highly party-political organisations. Party politics and changes in political colour/direction of leadership were observed to put strong constraints on place change within Northumberland and Bishop Auckland. In contrast to local government, the successful CEs in Northumberland followed a culture free from party politics and developed a long-term consensus focused on shared ideas for regenerating their “community of place” (Powe, Citation2019). Questions raised nationally about the appropriateness of their ownership of retail property probed the local authority role (Hammond & Pickard, Citation2020). Indeed, objections raised in Northumberland had similarities with the “market-first” ideas experience by Hackworth (Citation2014), given the strong divide along party political lines on public ownership of property, which did not extend to CEs. So even if a local authority becomes more active through property ownership, there are reasons to question if the commitment can be sustained long-term.

Secondly, as self-governance organisations with their own source of social enterprise funding, CEs have a degree of independence. This enables them to be more risk taking and “more agile” than local authorities. Consistent with the CDC literature (Bratt & Rohe, Citation2007; Heil, Citation2018), experience in Northumberland suggests the community-based nature of CEs can enhance acceptance of their activities. However, the experience in Northumberland suggests the process of achieving local and external accountability can be time consuming. With or without an active local authority, CEs have the potential to engage in built environment strategies at the town centre level. As a CE director explained, their unique form as a non-political organisation that “has some competence and individuality and independence” … “unlocks other things” and leads to acceptance through the resultant substantive outcomes.

Built Environment Strategies in Practice

In a similar way to Stockton council’s management of Wellington Square, property management by CDCs or CEs requires a viable business model underpinning their operation as responsible owners acting on behalf of their “community of place” (Fujii, Citation2016; Powe, Citation2019; Yin, Citation1998). Within Northumberland most of the CEs were initially based on a “managed workspace” business model, which involves property ownership and renting out space to a mixture of commercial/community uses. The initial capital to set-up and fund building renovation, usually from a public/charitable source, has been central to making the subsequent social enterprise viable (Powe, Citation2019). In the context of austerity, local authority funding for these Northumberland organisations has gradually declined, with only those establishing a portfolio of “enterprise” assets surviving. The CEs in Northumberland have a not-for-profit form common within the UK (Mswaka & Aluko, Citation2014).

In the context of struggling retail units, the prospects for CEs providing town centre residential properties became a key subject of discussion within the interviews, where two CEs in Northumberland have successfully provided residential properties above shops. In response to “milking” behaviour by some landlords (“absentee, low-quality landlords”), CEs can alleviate this challenge by becoming “ethical” private landlords (Mallach, Citation2010, p. 14). If there is a local market for such housing, then flats above shops may provide the lead activity for taking over an empty town centre property. Although capital intensive, a staged investment on empty property for adaptive reuse has previously been adopted in Northumberland. With residential rent underpinning the viability of the overall activity, the goal of filling the downstairs frontage becomes a longer-term challenge, where CE ownership at least provides some control over property maintenance.

Another business model might be providing spaces for innovation within a former brand name property. This has been achieved within a former department store in Stockton and delivered by the local authority (see the Enterprise Arcade in ). Whilst this “in-store” approach had not worked as a commercial operation within a former furniture shop within Bishop Auckland, the building was then successfully taken over as a social enterprise and has again returned to the private sector following the social enterprise director retiring. The empty shop next door to this social enterprise has been taken on by a former in-store tenant who prospered and “stepped-up” to their own store. Many more “stepping-up” successes were reported within Stockton Enterprise Arcade (Grimsey, Citation2021).

Faced with the “two-hats” problem, viability means that CEs are constrained to areas that face challenges but have potential for a degree of revival (Rhodes, Citation2019). Indeed, being over optimistic was seen as a reason for CE failure: “Call it what you like – community business, social enterprise, whatever you like, it is business, it’s money and, if it doesn’t stack-up, it is a project: and fund it as a project.” Property management by local authorities or CEs aims to eventually provide a viable rent-paying enterprise within properties. Whilst there needs to be this potential, delivery is inevitably a “project/enterprise” hybrid. This observation is as valid for Stockton’s town centre consolidation as CE efforts on a single building. The “project” elements require public/charitable external funding. As interviewees suggested, although the return on the “enterprise” elements might not be as large as required by the private sector, breaking even is necessary. Carefully balancing these “project” and “enterprise” elements can mean the difference between success and failure. The more challenging the context, the more the balance is towards “project” than “enterprise.” As the quote suggests, where “enterprise” is not possible, regeneration efforts become a “project” that needs to be funded as such.

Whilst a focus on rehabilitation and adaptive reuse has greater potential for maintaining town centre continuation/identity, in practice there are often significant constraints. For example, change from retail to a café may require ventilation; fire escape routes are required within conversion to residential. Former brand name store subdivision/adaptive reuse is challenged by natural light and limited frontage. As a planning officer suggested, “a building always performs best for its original intended purposes,” where repurposing is usually expensive and challenging. Careful selection is required, where adaptive reuse of some buildings is simply too complex. Consistent with the CDC literature (Hackworth, Citation2014), a key actor described inadequate maintenance of vacant properties as a “ticking time bomb” in terms of the potential for adaptive reuse. Delayed action reduces the possibilities for continuation of place.

Conclusion

Retail decentralisation is an ongoing and intensifying issue for town centres. The conceptualisation of the routes to maintaining core visitor/community attraction roles is incomplete. However, there is a growing realisation that many town centres can no longer maintain their former levels of commercial activity. Against the international backdrop of an oversupply of retail space, this paper asks how concepts of “smart-decline”/“rightsizing” can be insightful for struggling town centres. This represents the first detailed study to formally explore the application of these concepts to such central places, through two case studies from the North-East of England.

Consistent with urban shrinkage, both case study centres have experienced years of increasing vacancy where loss resulted from forced decoupling from brand name retail. A crisis has emerged as conditions have continued to deteriorate. Whilst there is acceptance of the problem, the initial response in Bishop Auckland was growth-oriented (focused on retail competitiveness). Although this policy failed, in an extreme act of serendipity, another growth opportunity emerged, shifting the focus from retail to leisure. Consistent with experiences documented by Rhodes (Citation2019), this strategy meant prioritising the area with the most potential.

Whereas the effects of wider urban decline on town centres may be most evident in secondary/peripheral commercial areas (Hollander & Hartt, Citation2019), the externally driven loss of brand names directly affects primary shopping areas, challenging ideas of consolidation. The Bishop Auckland case illustrates this well. At the time of writing, the upper end of the town centre is becoming an important leisure destination, with the complementary independent offer developing. The lower end provides more functional uses, anchored by two medium-sized supermarkets. The area suffering most is the main shopping street. Whilst fragmentation between the upper and lower areas of the centre is perhaps inevitable, in the context of a lack of viability and deteriorating conditions there is little evidence of the self-organisation of alternative uses. Although the issues involved in adaptive reuse are complex, whether in the form of a “project” or a “project/enterprise” hybrid, something else is required to stabilise the situation.

Experiences within Stockton-on-Tees fit more with the ideals of smart-decline. Early acceptance of the likelihood of brand name decline led to supportive policies starting seven years before major decline occurred. Such acceptance has alleviated the significant structural shock that has since materialised. Whilst vacancy rates have been increasing, the local authority has been working on opportunities that might emerge from town centre shrinkage. Following the purchase of the two main shopping centres in the town centre, demolition of one in an edge-of-centre location is enabling retail property consolidation. By relocating businesses, the offer and vacancy rate within the remaining centre is improving. Such ideals of consolidation have often not been realised in the context of place shrinkage, where residential displacement has been resisted (Hackworth, Citation2015). The termination of commercial lease agreements in the former retail mall and offer of relocation to the new centre has proved less controversial than residential displacement. Consistent with ideals of smart-decline, consolidation has provided an opportunity for place improvement by opening up the town centre to an attractive riverside environment.

Whilst local authority leadership has been key within the case studies of Stockton and Bishop Auckland, in the context of heightened risk and austerity, questions are increasingly asked about the appropriateness of local authority property ownership: positions on this issue can vary among political parties. This is a challenge to the development of a long-term consensus to smart-decline strategies. Drawing from recent research suggesting the importance of self-governance following place shrinkage (Powe et al., Citation2022), this paper has focused on Community Enterprises (CEs) which have similarities to Community Development Corporations (CDCs) that have provided such a crucial role within smart-decline efforts in America. Constrained by the “two-hat” problem, CEs are likely only effective in areas that at least have a degree of commercial potential (Rhodes, Citation2019). Compared to local authorities, CEs are often more focused on their “community of place” than on party politics. Whilst starting with a single building, through success, they can build up a portfolio of properties. Working long-term, they have the potential to combine external charitable/public funding, local knowledge and voluntary support, so that through a staged “project/enterprise” hybrid of activity, they renovate and find new uses for vacant properties. This potential might not otherwise be realised through private or public sector ownership. Whilst property ownership/management makes them particularly relevant to smart-decline, CEs represent a complementary form of self-governance to BIDs and other town partnerships. Working at the boundary between relevant actors within the town centre, over time, the self-governance and non-party political culture of CEs can encourage a “can do” attitude to help move beyond “doomed to fail” perspectives.

By making conceptual and practical linkages to the smart-decline literature, this paper has enhanced understanding of town centre decline and policy responses that might alleviate the challenges of town centre shrinkage. Two generic strategies have emerged: planning for a consolidated and reoriented town centre, still a visitor/community attraction but less dependent on brand names; and the creation of replacement uses that are complementary to the consolidated visitor/community attraction. Future research needs to focus on providing more case examples of such smart shrinkage and the opportunities it provides for place improvement. Making the link between CDC and CE research has extended understanding regarding the potential for new forms of self-governance to support built environment and community development roles. This topic has been neglected within the academic literature. Indeed, practical examples of CE activity within town centres remains scant and represents an important area for future research. The evidence presented here suggests the lack of such organisations in struggling town centres represents a missed opportunity.

The Covid pandemic has at best delayed progress responding to the challenges of town centre decline. The effects of debt accumulated during the pandemic are unclear. A reorientation to more leisure uses has been delayed and investment in vacant properties discouraged. The pandemic, however, may have increased acceptance of the need for town centre shrinkage. This paper provides a new lens for strategy development, and emphasises the need for future research to explore in more detail the application of smart-decline ideas to town centres, and has translated lessons from decades of American experience into a new context.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks for the support of Michael Waddell, Jade Harbottle and Kieran Campbell within the Stockton case study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Neil A. Powe

Neil A. Powe is Senior Lecturer in Planning at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at Newcastle University, UK. His recent research has focused on enhancing understanding of small town and town centre regeneration and recently co-authored the book Planning for Small Town Change.

Danny Oswell

Danny Oswell is a Lecturer in Planning at the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at Newcastle University. He has extensive experience in regeneration policy and strategy, strategic housing and corporate leadership. He has recently published on strengthening the quality of place agenda in post-Covid urban environments.

References

- Béal, V., Fol, S., Miot, Y., & Rousseau, M. (2019). Varieties of rightsizing strategies: Comparing degrowth coalitions in French shrinking cities. Urban Geography, 40(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1332927

- Bratt, R. G., & Rohe, W. M. (2007). Challenges and dilemmas facing community development corporations in the United States. Community Development Journal, 42(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsi092

- Bullen, P. A., & Love, P. E. D. (2010). The rhetoric of adaptive reuse or reality of demolition: Views from the field. Cities, 27(4), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2009.12.005

- Espinosa, A., & Hernandez, T. (2016). A comparison of public and private partnership models for urban commercial revitalization in Canada and Spain. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 60(1), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12226

- Fujii, Y. (2016). Spotlight on the main actors: How land banks and Community Development Corporations stabilize and revitalize Cleveland neighborhoods in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis. Housing Policy Debate, 26(2), 296–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2015.1064460

- Grimsey, B. (2021). Against all odds. Retrieved from: http://www.vanishinghighstreet.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/AgainstAllOdds-REVIEW-16th-July-optimised.pdf

- Guimarães, P. P. C. (2019). Shopping centres in decline: Analysis of demalling in Lisbon. Cities, 87, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.021

- Håkansson, J., & Lagin, M. (2015). Strategic alliances in a town centre: Stakeholders’ perceived importance of the property owners. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 25(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2014.949283

- Hackworth, J. (2014). The limits to market-based strategies for addressing land abandonment in shrinking American Cities. Progress in Planning, 90, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2013.03.004

- Hackworth, J. (2015). Rightsizing as spatial austerity in the American rust belt. Environment and Planning A, 47(4), 766–782. https://doi.org/10.1068/a140327p

- Hammond, G., Pickard, J. (2020). Treasury set to curb property investments by councils, Financial Times, Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/d68e46f9-2f13-465f-beb3-466c4f2d8530

- Heil, M. (2018). Community development corporations in the right-sizing city: Remaking the CDC model of urban redevelopment. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(8), 1132–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1443012

- Hollander, J. B., & Németh, J. (2011). The bounds of smart decline: A foundational theory for planning shrinking cities. Housing Policy Debate, 21(3), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2011.585164

- Hollander, J. B. (2018). A research agenda for shrinking cities. Edward Elgar.

- Hollander, J. B., & Hartt, M. (2019). Vacancy and property values in shrinking downtowns: A comparative study of three New England cities. Town Planning Review, 90(3), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2019.18

- Hospers, G. J. (2014). Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. European Planning Studies, 22(7), 1507–1523. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.793655

- Hospers, G. J. (2017). People, place and partnership: Exploring strategies to revitalise town centres. European Spatial Research and Policy, 24(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1515/esrp-2017-0004

- Housing Communities and Local Government Committee (HCLGC). (2019). High streets and town centres in 2030, House of Commons, London. Retrieved from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcomloc/1010/1010.pdf

- Hughes, C., & Jackson, C. (2015). Death of the high street: Identification, prevention, reinvention. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1016098

- Hummel, D. (2015). Right-sizing cities in the United States: Defining its strategies. Journal of Urban Affairs, 37(4), 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12150

- Mallach, A. (2010). Meeting the challenge of distressed property investors in America’s neighborhoods, Retrieved from https://www.lisc.org/our-resources/resource/meeting-challenge-distressed-property-investors-americas-neighborhoods/

- McGreevy, M. P., & Wilson, L. (2017). The civic and neighbourhood commons as complex adaptive systems: The economic vitality of the centre. Planning Theory, 16(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095216631587

- McGovern, S. J. (2006). Philadelphia’s neighborhood transformation initiative: A case study of mayoral leadership, bold planning, and conflict. Housing Policy Debate, 17(3), 529–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2006.9521581

- Mswaka, W., & Aluko, O. (2014). Legal structure and outcomes of social enterprise: The case of South Yorkshire, UK. Local Economy, 29(8), 810–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094214558007

- Needham, B. (2007). Dutch land-use planning: Planning and managing land-use in the Netherlands, the principles and the practice. SduUitgevers.

- Otsuka, N., & Reeve, A. (2007). The contribution and potential of town centre management for regeneration: Shifting its focus from ‘management’ to ‘regeneration. Town Planning Review, 78(2), 225–250. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.78.2.7

- Powe, N. A. (2012). Small town vitality and viability: Learning from experiences in the North East of England. Environment and Planning A, 44(9), 2225–2239. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44596

- Powe, N. A., & Hart, T. (2017). Planning for small town change. Routledge.

- Powe, N. A. (2019). Community enterprises as boundary organisations aiding small town revival: Exploring the potential. Town Planning Review, 90(6), 625–651. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2019.40

- Powe, N. A. (2020). Redesigning town centre planning: From master planning revival to enabling self-reorientation. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1749719

- Powe, N. A., Connelly, S., & Nel, E. (2022). Planning for small town reorientation: Key policy choices within external support. Journal of Rural Studies, 90, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.01.009

- Rauws, W. (2016). Civic initiatives in urban development: Self-governance versus self-organisation in planning practice. Town Planning Review, 87(3), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.23

- Rhodes, J., & Russo, J. (2013). Shrinking ‘smart’: Urban redevelopment and shrinkage in Youngstown, Ohio. Urban Geography, 34(3), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.778672

- Rhodes, J. (2019). Revitalizing the neighborhood: The practices and politics of rightsizing in Idora, Youngstown. Urban Geography, 40(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1258179

- Robertson, K. (2001). Downtown development principles for small cities. In M. A. Burayidi (Ed.), Downtowns: Revitalizing the centres of small urban communities (pp. 9–22). Routledge.

- Schilling, J., & Logan, J. (2008). Greening the rust belt: A green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(4), 451–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360802354956

- Stubbs, B., Warnaby, G., & Medway, D. (2002). Marketing at the public/private sector interface; town centre management schemes in the south of England. Cities, 19(5), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(02)00040-9

- Thomas, C. J., & Bromley, R. D. F. (2003). Retail revitalisation and small town centres: The contribution of shopping linkages. Applied Geography, 23(1), 47–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0143-6228(02)00068-1

- Varady, D., Kleinhans, R., & van Ham, M. (2015). The potential of community entrepreneurship for neighbourhood revitalization in the United Kingdom and the United States. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 9(3), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-01-2015-0009

- Ward, K., & Cook, I. (2017). Business improvement districts in the United Kingdom. In I. Deas, and S. Hincks (Eds.), Territorial policy and governance: Alternative paths (pp. 127–146). Routledge.

- Yin, J. S. (1998). The community development industry system: A case study of politics and institutions in Cleveland, 1967–1997. Journal of Urban Affairs, 20(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.1998.tb00415.x