Contents

Introduction: Infrastructure That Connects/Infrastructure That Divides

Matti Siemiatycki and Kevin Ward

“Rail Linor Itu Pare”: Railways as Infrastructural Borders in Guwahati, Northeast India

Prerona Das, Tim Bunnell and James Sidaway

Infrastructures of Water and Ideas: The Struggle Against Environmental Racism in Black Urban Regimes

Alesia Montgomery

Sawyer Phinney

Whose Infrastructure is it Anyway?

Astrid R.N. Haas

Promoting Essential Green Infrastructure by Acknowledging Local Needs in Praxis

Ian Mell and Tenley Conway

Climate Resilient Infrastructure – Connecting and Dividing the Cities of the Future

Cathy Oke

Infrastructure That Connects/Infrastructure That Divides

Matti SiemiatyckiKevin WardWe live in an age of infrastructure, we are told repeatedly (Dodson, Citation2017). Around the world and across the ideological spectrum, firms and governments are dedicating trillions of dollars per year to infrastructure. Conservatives and Liberals, in the Global North and South, and in authoritarian and democratic regimes are championing major infrastructure programs. Infrastructure policy and spending is increasingly becoming a key tool in local, national and global statecraft.

While there is broad agreement across the ideological spectrum about the dire need to invest in infrastructure in order to achieve economic, environmental, and social objectives (as well as to make good on the damage done by past infrastructural policy), increasingly the term has become stretched to the point where we have seen the contesting of its meaning.

The most traditional and narrow definition of infrastructure refers to fixed capital stretched across space in networked facilities – roads, bridges, tunnels, railways, transit lines, water and sewage treatment facilities and pipes, power lines and associated generation plants and dams, energy pipelines, and telecommunication cables. These are what used to be known as public works, an underlying basis for a modern society.

Trees and naturalized habitats are also being categorized as green infrastructure, since they serve the same function as the built grey infrastructure that stores water or retains hillsides – only in many instances the green infrastructure is more successful. Ditto, blue infrastructure, such as canals and rivers, and their importance to urban metabolism.

More recently, we have seen the definition widening to include “social infrastructure,” such as care centers, hospitals, housing, libraries, and recreation centres. These are typically services provided in facilities on a single site, but are part of wider service networks. Because social infrastructure involves significant outlays for capital and maintenance and supports the social fabric of society, it is considered infrastructure. This includes new infrastructure but also repaired infrastructure. Now, in many countries, we are seeing the definition of infrastructure stretching ever further, with examples emerging of how activists and communities have sought to insert the notion of “care” into debates over working with existing infrastructural configurations. In the United States under the Biden infrastructure bill, for instance, we see the presentation of social services like childcare, health care, and elder care as the infrastructure of care.

Indeed, as the definition of infrastructure expands (Carse, Citation2016), it is becoming a magical term. Unlike more conventional spending on goods and services that get tied up in parochial debates, infrastructure is presented as an investment that is far sighted, visionary, transformational and non-partisan, paying dividends for future generations. Who could possibly be against infrastructure investment?

Of course, while infrastructure as a concept may have broad partisan and public support, particular infrastructure projects and political programs are most certainly contested, portrayed by opponents as wasteful, self-serving, politically motivated pork-barreling. For decades, there has been a visceral public and scholarly understanding of both the light and the dark sides of infrastructure. Infrastructure connects. However, infrastructure also divides. Infrastructure is not equally distributed, and the benefits and negative externalities of infrastructure do not affect everyone similarly.

Let us briefly outline the most glaring paradoxical and conflicting dynamics of infrastructure.

Infrastructure is central to the heroic founding mythology of many countries, but also played a key role in colonization (Cowen, Citation2020). In Canada, for instance, the construction of the Trans-continental railway physically and politically stitched together a massive and disparate country from sea to sea. Among the most iconic photos in Canadian history is the ceremonial driving of the last railway spike in 1885 by Donald Smith, Baron of Strathcona. A crowd of White men surround him. The railway was also critical in the dispossession of indigenous people from their lands as it brought settlers and state reinforcements to the West, and was built in part by Chinese labourers who faced deep-seated racism and discrimination. In the Global South, building energy and transportation infrastructure to serve the colonial imperative for control and resource extraction, rather than the needs of the local populations, left a legacy of uneven development (Táíwò, Citation2022).

Environmental racism is rife in the locating of infrastructure, with noxious and disruptive infrastructure facilities like stinking garbage dumps, polluting power plants and divisive highways disproportionately located in low income and racialized communities. The highways that were built through the Greenwood neighbourhood in Tulsa Oklahoma in the 1960s, Africville in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Hogans Alley, British Columbia, destroyed centres of Black economic activity and life in the name of urban renewal. It has only been in the past few decades that the state agencies that led these projects accepted responsibility for their actions. Nor is environmental racism a historic relic. The Flint water crisis, where polluted water and lead pipe contamination disproportionally affected Black residents, has widely been identified as stemming from environmental racism (Wilson & Heil, Citation2022). As Pulido (Citation2016, p. 6) writes: “The decision to neglect infrastructure so that it becomes toxic must be seen as a form of violence against those who are considered disposable.” And, elsewhere in the world, as we witness the urbanization of rural societies in the Global South, we see examples of accumulation by dispossession and the displacement of indigenous and racialized communities. In some cases, the profits from these activities are then used to upgrade infrastructure in cities of the Global North, reinforcing the inter-connectedness of decision-making.

In an age of accelerating climate change, heavily carbon-intensive infrastructure in transportation, energy production and buildings are at the core of the climate emergency. Yet paradoxes and tensions abound. Global access to low-cost consumer products is brought about through huge investments in ports and logistics infrastructure, which is powered by carbon fuels and massive amounts of emissions. Air travel faces similar tensions – the prospect of mass global travel is so seductive as a means of connecting the world for social, cultural and business reasons; yet air travel is the fastest growing source of greenhouse gas emissions and privileges a small minority of frequent flyers who travel the bulk of the miles globally, becoming a key target for climate activists. Enormous spending in the electrification and greening of infrastructure is also providing the path towards mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, with many governments setting net zero emission targets for 2050 or even earlier. Initiatives such as building energy retrofits and massive tree planting initiatives in infrastructure programs point to the further ways in which climate change is forcing a rethink of the definition of infrastructure. However to date, adapting existing infrastructure to protect against a changing climate that is warmer, wetter and wilder than in the past has received far less funding than mitigation efforts, with ever more costly climate-related disasters occurring each year.

Infrastructure also bridges and reinforces inequalities. Transit mega-projects designed to provide improved service and accessibility to low income, racialized communities are being found, in some instances, to spur gentrification and displacement of exactly the communities they are intended to serve. Infrastructure networks are increasingly being unbundled, reconstituted as premium services like express airport rail links, privatized water wells in drought stricken cities, and priority internet connections delivering ultra-high speeds, for those most able to pay. Rising energy costs may reduce demand and spur conservation efforts that ultimately reduce emissions, but they are putting dramatic inflationary pressures on households whose wages have stagnated, with little relief in sight. It is little wonder that many major social movements are sparked by unequal or diminishing access to quality infrastructure – a mere 4% rise in bus fares in Chile’s capital city Santiago set off widespread protests in 2019 (Holland, Citation2019); water privatization and rising prices sparked mass protests in Bolivia.

Additionally, infrastructure has special political purchase as a job creator. In many countries, the aim of green infrastructure investment is to support a broader transition to a green economy and workforce. However, questions remain about “jobs for whom?” The infrastructure sector is overwhelmingly male dominated, on construction sites and in the boardrooms where investment and policy decisions are made (Siemiatycki et al., Citation2020). Coming out of a pandemic that disproportionately impacted women and sparked what has been called a “she-cession,” an infrastructure-led recovery will disproportionately benefit men in the absence of intentional gender-based policy.

Despite the big promises made for infrastructure investments, it is now widely acknowledged that infrastructure mega-projects are beset by a systemic pattern of underestimated costs and timelines alongside overestimated benefits. It is uncanny how often the words “boondoggle” or “white elephant” are used to describe infrastructure plans and programs. This pattern of mega-projects going over budget and being late belies simple technical explanations about the complexity of delivering large undertakings. It is rooted in the behavioural biases and political dynamics of the people and organizations involved in project planning and delivery (Flyvbjerg et al., Citation2003). Planning, approving and delivering infrastructure projects is a very human activity, with all the human conditions and failings that this entails.

Infrastructure is also now increasingly at the heart of global geopolitical struggles and tensions. At one time, Western development banks, national overseas aid departments, and multilateral agencies had a monopoly on financing infrastructure in low-income countries. The World Bank and other investors typically attached “structural adjustment” conditions to loans related to economic liberalization, anti-corruption, human rights, transparency and democratic governance. The rise of China as an overseas infrastructure investor has created new geopolitical competition and tensions. China has become a major infrastructure investor in Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and Latin America, using a model that emphasizes loans as a business and political transaction rather than a vehicle to impose social, economic or governance transformations. In one model known as Resources-for-Infrastructure, Chinese banks provide loans to countries that may otherwise struggle to attract investment at competitive interest rates, with the loans secured against local resources. There is considerable debate about whether the arrival of China as a major international player in the global infrastructure sector frees countries from the paternalism of self-serving Western powers by providing another option, or is a form of “debt book diplomacy” that represents a new form of colonialism. Some analysts have gone so far as to question whether we may be entering a new cold war, with infrastructure investments a key site of global geopolitical engagement (Schindler et al., Citation2022; Singh, Citation2021).

The contributions to this Interface section highlight the dynamics and tensions that beset infrastructure.

Prerona Das, Tim Bunnell, and James D. Sidaway zero in on networked infrastructure as physical and symbolic connectors and borders. In vivid detail, they show how a railway line in Northeast India reflects and reinforces hierarchies of power, first extending British colonial power when initially built and more recently serving as a barrier dividing communities along ethnic, confessional and linguistic lines.

Alesia Montgomery examines the roots and struggles against environmental racism in Black urban communities with a spotlight on the water sector. Montgomery’s contribution forcefully highlights how physical, financial and ideological conditions together cause the uneven and deeply inadequate water systems in many majority-Black cities in the United States.

Similarly, for Sawyer Phinney, infrastructure plays a key role in racial capitalism. The financialization and practices of state austerity in majority-Black cities in America is a key driver of uneven infrastructure development.

A number of the contributions grapple in different ways with the politics of scale when it comes to infrastructure decisions. The key question at the core of Astrid Haas’s contribution is who gets to decide what gets built when there are multiple stakeholders involved, each with their own sets of interest. Drawing on the situation in Kampala, Uganda, Haas shows how local stakeholder interests mingle uncomfortably with those of foreign governments deciding how to allocate their aid budgets, international institutions and global investors.

For Ian Mell and Tenley Conway, the primary challenge is how to build support for urban greening as a form of infrastructure that delivers major public value, where it is often overlooked, downplayed and contested. The answer, Mell and Conway argue, lies in deep meaningful engagement in local practice so that green infrastructure responds to community needs and redresses the burdens that historically disenfranchised communities have faced.

Finally, Cathy Oke reflects on her experience as a local government politician in Melbourne, Australia implementing key climate resilient transport infrastructure. She shows how decision makers grapple with the ways in which critical infrastructure investments can be accelerated or stymied by deeply local narratives, memes and pressure that influence how choices are weighed and made.

Taken together, the fault-lines inherent in infrastructure are wide ranging, interwoven and cascading. The notion that infrastructure connects, and that infrastructure divides has many meanings – socially and spatially, culturally and economically, ideologically and politically, and as a tool of global geopolitics and geostrategy.

Notes on Contributors

Matti Siemiatycki is Director of the Infrastructure Institute and Professor of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto. [email protected]

Kevin Ward is Professor of Human Geography at the University of Manchester and editor in chief of Urban Geography. [email protected]

References

- Carse, A. (2016). Keyword: Infrastructure. In P. Harvey, C. Jensen, & A. Morita (Eds.), Infrastructures and social complexity: A companion. Routledge.

- Cowen, D. (2020). Following the infrastructures of empire: Notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method. Urban Geography, 41(4), 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1677990

- Dodson, J. (2017). The global infrastructure turn and urban practice. Urban Policy and Research, 35(1), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2017.1284036

- Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., & Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge University Press.

- Holland, A. (2019, November 1). Chile’s streets are filled with protests. How did a 4 percent fare hike set off such rage? Washington Post.

- Pulido, L. (2016). Flint, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013

- Schindler, S., DiCarlo, J., & Paudel, D. (2022). The new cold war and the rise of the 21st-century infrastructure state. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 47(2), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12480

- Siemiatycki, M., Enright, T., & Valverde, M. (2020). The gendered production of infrastructure. Progress in Human Geography, 44(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519828458

- Singh, A. (2021). The myth of “debt-trap diplomacy” and realities of Chinese development finance. Third World Quarterly, 42(2), 239–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1807318

- Táíwò, O. (2022). Reconsidering reparations. Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, D., & Heil, M. (2022). Decline machines and economic development: Rust belt cities and Flint, Michigan. Urban Geography, 43 (2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1840736

“Rail Linor Itu Pare”: Railways as Infrastructural Borders in Guwahati, Northeast India

Prerona DasTim BunnellJames D. SidawayIt seems almost a truism to note that urban infrastructure both reflects and reproduces hierarchies of power and privilege and plays a constitutive role in everyday socio-spatial dividing practices (Angelo & Hentschel, Citation2015; Lemanski, Citation2020). It connects some spaces and communities while excluding others. Infrastructures also shape everyday life and sensibilities within cities. In the words of Steele and Legacy (Citation2017), “critical infrastructure as a multidimensional and lived phenomenon is as much about space, place, ecology, and culture, as it is about pipes, scaffolding wire, and concrete” (p. 3).

On the one hand, we see the distribution of infrastructural systems or networks across and between state territories. On the other hand, we argue it is its omnipresent, place-based forms that act as an interface with the user (Larkin, Citation2018). Through such material urban forms, everyday urbanism intersects with larger scales, revealing the potential and power of infrastructure. Here we examine how a branch line of the railway infrastructure that connects the city of Guwahati in northeastern India to the rest of the country simultaneously borders urban lives and imaginaries. Locally, this line demarcates ”us“ and ”them“ – people on one side of the track differentiating themselves from those on the other (”rail linor itu pare“) – in ways inflected by a variegated (geo) politics of national belonging.

Railways and Partition (Geo) Politics in India’s Northeast

Indian Railways began as a key component of colonial infrastructural investment intended to connect British-controlled parts of extended India, both internally – across what are today the national territories of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan – and as part of a wider globalizing imperial economy. Railways facilitated exports of raw materials from India and transported people across imperial South Asia. This project intertwined railway technology, time and infrastructure with daily lives of Indians, signifying the presence of the colonial state at the everyday scale (Prasad, Citation2015). Railway infrastructure has retained prominence in the socio-spatial fabric of cities after the Partition and Independence of India. The railways remain important to urban life, not merely as a mode of transportation, but also as an agent shaping urban experiences and mental maps, and situating communities in relation to ”others“ at various scales. Otherwise divided, interactions with railway infrastructure that intersect urban spaces constitute a common experience for city residents. Yet within Indian cities, the railways also foster an awareness of difference and demarcate socio-spatial segments on ethnic and confessional grounds, tied to the geopolitics of Partition.

In northeastern India, connections/disconnections aided by railways become particularly visible; railways connect this frontier to what is often referred to as ”mainland“ India through the narrow Siliguri corridor, and railway infrastructures cutting across the region reinforce ethnic, confessional, linguistic and class divides, especially within cities. As a strategic geopolitical frontier, the northeast was both a settlement and a resource frontier of British India; the primary purpose behind the construction of the railways was to secure the region, facilitating a plantation economy. The construction of Assam-Bengal Railways commenced in the late nineteenth century primarily to boost the tea industry in Assam (Guha, Citation2016). The northeast was then thinly populated and the British imperialists sought labor for the tea trade and other plantations. The railways served as a cost-effective mode of transportation to transport workers from more populated areas like eastern Bengal (now Bangladesh) and Bihar (Das, Citation2022). This resulted in demographic change and bolstered ethno-confessional diversity in the region. Amidst the demarcation of an imagined Assamese community in the state of Assam, the Bengali Muslim population that migrated from eastern Bengal were perceived as ”others“ by Assamese Hindus who were the majority. Such tensions inflicted violence, as imagined borders, as well as new political borders, that defined who belonged where were hardened due to partition ().

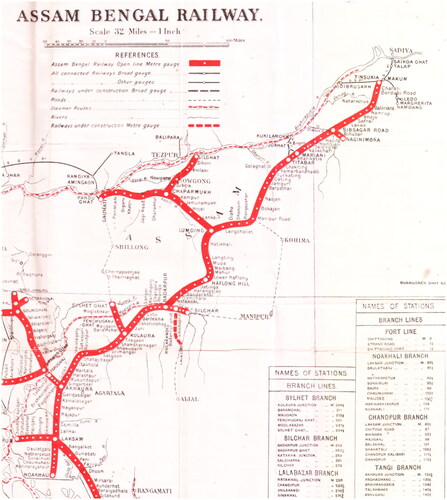

Figure 1. Map of Assam-Bengal Colonial Railways (exact date unknown). Source: Assam State Archives, Guwahati.

In 1947 when the Radcliffe line was drawn across the subcontinent, yielding India and (East and West) Pakistan, the railway network was also partitioned, almost cutting off northeast India from the rest of the country (Van Schendel, Citation2017) and reinforcing the peripheral status of the region. However, railways facilitated the movements of refugees from east Bengal (East Pakistan) to Assam during Partition, and concurrently railway stations and tracks also became sites of communal violence (Das, Citation2022). Hence, there was a historic intertwining of railway infrastructure with geopolitical and communal turmoil in the frontier of northeast India.

In Assam, the last decade has seen the reanimation of post-Partition contestations between communities Violence against minority Bengali Muslims increased in the state, especially after the pro-Hindutva Bhartiya Janata Party formed a national government in 2014, and came to power in Assam in 2016 (see Saikia, Citation2020). This became evident during subsequent turbulence over the National Register of Citizenship (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). We argue that railway infrastructure continues to play an important role in reproducing the wider (geo) politics of exclusion in everyday life within Assam’s largest city of Guwahati.

Railway Infrastructure as Everyday Borders in Guwahati

Different types of borders cut across urban spaces, including zoning laws, socio-spatial segregation, infrastructural exclusion, physical barriers, and imagined divides (Breitung, Citation2011; Jirón, Citation2019). Multiple bordering processes (re)demarcating identity and territorial claims intersect Guwahati, overlapping with other socio-spatial urban divides. This British administration-built railway line, originally a branch line of Assam-Bengal Railways (Barpujari, Citation1992), includes tracks and railway gates that cut across and serve to demarcate parts of the city. One of us grew up in Silpukhuri, a locality in east Guwahati divided by the railway line. It is home to communities including Assamese Hindus and Bengali Muslims, producing a “peculiar cosmopolitanism” (Kikon & McDuie-Ra, Citation2021). The railway tracks are a part of the area’s urban ecology, affecting socio-spatial dynamics and residents’ mobility patterns. Silpukhuri is also the location of one of the thirteen railway crossings of the Northeast Frontier Railway. The Railway gates close whenever a train passes through the locality, preventing commuter traffic. This can greatly increase residents’ travel times, and many therefore seek to avoid crossing the tracks as part of their daily commutes.

Because of the aesthetics and sensibilities associated with railway tracks and other infrastructural forms that sever spaces (Salomon, Citation2016), they become a feature of people’s mental maps, situating themselves and imaginatively separating “others.” In Silpukhuri, the UNB Road refers to the northern side of the railway tracks. Assamese middle class Hindus predominantly inhabit it. Across the tracks on the southern side, there exists Gandhibasti settlement, populated by Bengali Muslims who are mostly engaged in menial/low wage jobs such as construction work, street cleaning and ”rag-picking.“ The residents of Silpukhuri frequently use the expression ”rail linor itu pare“ in Assamese, which translates to ”the other side of the tracks,“ to refer to the residential segments on the other side. The majority of the families in Gandhibasti settlement have lived in Assam for generations and possess the legal documents to have their names included in the National Register of Citizenship. Yet the majority residents of Guwahati often deem them as Bangladeshi immigrants living on encroached railway land, where criminal activities such as drug peddling and gambling take place. Assamese Hindu residents of UNB Road who have security-related anxieties about Gandhibasti settlement – anxieties that are themselves felt differently along lines of age and gender, and according to the time of day – use the railway tracks as a point of reference for separating the two sides.

Conversely, residents of Gandhibasti settlement view the railway tracks as a boundary beyond which resides the affluent population of the locality/city. In terms of basic civic infrastructure such as water supply, drainage and roads there is some visible difference between both the sides. Residents from both sides of the tracks also face common problems such as shortages of drinking water and flooding during the monsoon. Nonetheless, the prevailing view amongst Gandhibasti settlement dwellers is that connections to local politicians and municipality officers privilege Assamese Hindu UNB Road residents, affording them better infrastructural access on their side. Regarding this (perceived) difference a woman from the settlement lamented, ”On the other side of the tracks (rail linor itu pare) many influential people live and they have good access to infrastructure facilities, but they don’t come forward to help us improve the infrastructure on this side.“ For the Gandhibasti settlement dwellers, therefore, the bisecting railway infrastructure is an everyday reference or reminder of the marginalization that they experience in the city and the nation more widely. The tracks are not just part of the material urban fabric, but also cognitive maps and everyday discourses reinforcing disconnections and wider communal divisions.

Conclusion

The agency of infrastructure takes the most potent form in certain urban nodes, where it simultaneously connects and disconnects communities and places. Connection and disconnection become legible at different scales and sites. However, in widespread infrastructural networks, we observe the intensified bordering processes most acutely in micro-urban sites. Massive infrastructure such as Indian railways had a major role to play in shaping the colonial and postcolonial socio-material history of India. However, in contemporary urban spaces it becomes a part of the ordinary, ”everyday“ urban materialities and imaginaries, reinforcing various connections and disconnections. In localities such as Silpukhuri where communities divided on confessional and ethnic lines live in proximity, interactions with everyday infrastructure such as railways become significant markers of wider geopolitical borders and identities. Large-scale, networked, colonial-derived infrastructure such as Indian railways (that in turn connect with planetary-spanning transport infrastructures) thus assume another local function and meaning as a dividing infrastructure.

Notes on Contributors

Prerona Das is a postdoctoral research fellow at Singapore Management University’s College of Integrative Studies. Her doctoral research was on borders reinforced by urban infrastructure in Guwahati, northeast India. As a research fellow she is currently working on a project about politics of smart city policy transfer in Southeast Asia. [email protected]

Tim Bunnell is professor of human geography and director of the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. His urban research has included examination of the planning and development of cities in Asia, and the lives and aspirations of people who call them home. [email protected]

James D. Sidaway has served as Professor of Political Geography at NUS since 2012. Following doctoral research on the intersections of conflict, planning and territory in Mozambique, he has worked on histories of geopolitics and cross-border relations of Portugal, and on urban geopolitics in Cambodia, Iraq, the Persian Gulf and Singapore’s Indonesian borderlands. [email protected]

References

- Angelo, H., & Hentschel, S. (2015). Interactions with infrastructure as windows into social worlds: A method for critical urban studies: Introduction. City, 19(2–3), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275

- Barpujari, H. K. (1992). Political history of Assam: 1826–1919. Government of India.

- Breitung, W. (2011). Borders and the city: Intra-urban boundaries in Guangzhou (China). QUAGEO, 30(4), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10117-011-0038-5

- Das, P. (2022). Tracking the border: Micro-geographies of infrastructural borders in Guwahati, India [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. National University of Singapore.

- Guha, A. (2016). Planter Raj to Swaraj: Freedom struggle and electoral politics in Assam, 1826–1947. Anwesha Publications.

- Jirón, P. (2019). Urban borders. In M. O. Anthony (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of urban and regional studies (pp. 1–5). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kikon, D., & McDuie-Ra, D. (2021). Ceasefire city: Militarism, capitalism, and urbanism in Dimapur. Oxford University Press.

- Larkin, B. (2018). Promising forms: The political aesthetics of infrastructure. In N. Anand, A. Gupta, & H. Appel (Eds.), The promise of infrastructure (pp. 175–202). Duke University Press.

- Lemanski, C. (2020). Infrastructural citizenship: The everyday citizenships of adapting and/or destroying public infrastructure in Cape Town, South Africa. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 45(3), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12370

- Prasad, R. (2015). Tracks of change: Railways and everyday life in colonial India. Cambridge University Press.

- Saikia, S. (2020). Saffronizing the periphery: Explaining the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party in contemporary Assam. Studies in Indian Politics, 8(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023020918064

- Salomon, D. (2016). Towards a new infrastructure: Aesthetic thinking, synthetic sensibilities. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 11(2), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/18626033.2016.1188574

- Steele, W., & Legacy, C. (2017). Critical urban infrastructure. Urban Policy and Research, 35(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2017.1283751

- Van Schendel, W. (2017). Afterword: Contested, vertical, fragmenting: De-partitioning “Northeast India” studies. In M. Vandenhelsken, M. Barakataki-Ruscheweyh, & B. G. Karlsson (Eds.), Geographies of difference (pp. 272–288). Routledge India.

Infrastructures of Water and Ideas: The Struggle against Environmental Racism in Black Urban Regimes

Alesia MontgomeryFrom the failure of the levees in New Orleans to the mass water shutoffs in Detroit to the lead poisoned water in Flint to the dry faucets in Jackson, water crises in majority Black cities of the U.S. have made headlines. Despite the proliferation of these cases, reporters often frame each disaster as a rare event. The reality is that aging systems for drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater – in need of an upgrade in much of the U.S. – have reduced a capacity to withstand severe weather and other stresses (ASCE, Citation2021; Christian-Smith et al., Citation2012; Deitz & Meehan, Citation2019; McDonald & Jones, Citation2018). Low-income racialized communities disproportionately rely on water systems that suffer from vast underfunding, inadequate regulation, and environmental degradation, which makes it hard for these systems to provide flood protection and safe, affordable drinking water.

Ideological and material conditions combine to shape the danger. Historian Carl Smith (Citation2013) describes how, during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the physical infrastructure of the first municipal water systems that were built in the U.S. by white elites was inseparable from their ”infrastructure of ideas“ about society and nature. The pumps, pipes, and wheels of the early waterworks, enclosed in neoclassical architecture, were at once engineering feats and monuments to the aspirations of the rising business class for purity, power, and elegance. Critical environmental justice (CEJ) scholars argue that today’s austerity discourse – proceeding from a neoliberal logic that has roots in African enslavement, Indigenous dispossession, and ecological exploitation under racial capitalism – hinders the upgrade of U.S. water systems in racialized communities (Pulido, Citation2016). The water infrastructure of these communities crumbles within a deadly infrastructure of ideas about race and nature. This ideological infrastructure frames residents of Black urban regimes as children of nature who must have (fiscal) discipline imposed on them. CEJ scholars borrow the term ”racial capitalism“ from historian Cedric Robinson, who notes that, since the rise of the modern world system, the ”development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions, so too did social ideology“ (Robinson, Citation2000, p. 2). Robinson posits a dynamic relation between racial capitalism and the Black radical tradition, which seeks to expand freedom for Africa and its diaspora. Gilmore (Citation2011) brilliantly articulates how this dynamic relation unfolded in battles over infrastructure during the civil rights movement of the 1960s:

The Freedom Riders and much of the civil rights movement targeted, of all

things, infrastructure for desegregation. They targeted schools, they

targeted highways, they targeted mass transportation. Their focus … sought

to put into the landscape, the land around us, something new: the capacity for

us to determine for ourselves protections from calamity and opportunities

for advancement, inspired by a long-term vision to shift the foundations for the struggle

for freedom ….so that freedom wouldn’t turn into…simply the absence of cuffs…or being in a cage.

Gilmore frames a (material | mental) struggle for collective self-determination that strives to liberate people by transforming the physical and ideological infrastructures that gird the social order. She juxtaposes the vision of abolition geographies against the nightmare of carceral geographies – jails, prisons – used to manage the anger and desperation of young people who live amid crumbling infrastructure in impoverished, racially segregated communities.

At this historical moment, Black urban regimes are critical sites of this (material | mental) struggle for freedom. I raise questions about the ethics of how scholars and practitioners of diverse races (you and I) participate in this struggle as we study or design infrastructure in Black urban regimes and other racialized communities. My questions emerge from my research: For over a decade, I have studied the extent to which African Americans of different classes are able to ”put into the landscape“ of Black urban regimes ”protections from calamity and opportunities for advancement.“ I am especially concerned about how the water systems of these cities – essential to life – are maintained and upgraded.

Between 2010 and 2012, I lived in Detroit and studied its green redevelopment projects, which were staffed by international and local teams of technical experts (engineers, architects, planners) and cultural workers (artists, activists, street scholars), affiliated with a wide array of firms and universities, who had been hired by philanthropic and business interests (Montgomery, Citation2020). These projects included innovative ideas – rooted in the urban vision of the mostly white experts – that included designs for green and blue infrastructure to improve air quality and to capture and clean stormwater. While this green vision was uncontroversial, it was embedded in a plan for rightsizing the city that stirred fear and anger among some Detroiters. They worried that rightsizing – aligning infrastructure investments with the population size and market potential of neighborhoods – might accelerate gentrification in greater downtown while depriving needed services from residents in depopulated, high poverty areas. The planning process included outreach, but it did not enable low-income Black residents to have decision-making power.

My interviewees in Detroit included local community organizer and ecologist Charity Hicks. Hicks was a founding member of the People’s Water Board, a grassroots group that advocates for human rights to water and sanitation. (Two years after my initial interview, Hicks would be hailed as a ”water warrior“ as she fought for low-income Detroiters during the mass water shut-offs of 2014.) Hicks had served on the Mayor’s Advisory Task Force for the public-private partnership that was developing a green city plan. Hicks liked some of their ideas, but she told me that they paid more attention to the physical infrastructure than the human infrastructure. She charged that some of them regarded low-income Black Detroiters as ”dredges“ and did not engage in authentic dialogues with them:

The aim is for a more efficient municipal operation, but you haven’t retooled the people. How do we invest in those structures, in those operations, that promote investment in people. How do we embody respect for people, not calling them dredges or prostitutes or the illiterate…. [We need structures] that will get underneath crime, that will get underneath a carjacking, that will make people feel worthwhile.

I interviewed a few members of the technical and outreach teams: One technical expert told me that what is possible to build is different from what is ideal: ”Capitalism is built on inequality. I don’t know if we can ever have justice, but we can further justice.“ Similarly, some cultural workers on the outreach team told me that the history of urban renewal made them cautious, but the public-private partnership had money to redesign Detroit (a rare resource in the city), so they had decided to work with it to make a difference.

I remain troubled by neoliberal planning that prevents low-income African Americans from democratically debating and deciding urban futures, but I am even more alarmed when I read about the water struggles and policy battles in Jackson, Mississippi. I see a growing interdependence between neoliberal planning and the construction of societal ignorance about environmental racism and ecological destruction. The city of Jackson – the capital of Mississippi – was named after Andrew Jackson, a U.S. president and planter who grew wealthy from the labor of enslaved Africans. He is also notorious for signing the Indian Removal Act, which forced thousands of Indigenous people from their ancestral homelands. The city of Jackson, located on land seized from the Choctaws, prospered in the early twentieth century as oil and natural gas industries boomed in the region, but the life chances of its Black residents were limited. In the 1960s, the civil rights struggle exploded in Jackson; the jailing of Freedom Riders ensued in 1961, and then a white supremacist murdered Medgar Evers, a NAACP leader, in 1963. In the 1970s and 1980s, after federal courts ordered school desegregation, white families fled Jackson for the suburbs, taking their wealth with them. Jackson became a Black urban regime, and similar to others, Jackson suffers from high poverty rates and a reduced tax base. Yet, as a capital city, it sits uneasily within the borders of conservative white power in the state.

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba describes his city of Jackson as ”the poster child of the infrastructure challenges that we see in this country“ (Democracy Now, Citation2022). On Monday, 29 August 2022, Lumumba, a Black Democrat, declared a water system emergency in Jackson. That night, Governor Tate Reeves, a white Republican, did likewise. The flooding of the Pearl River in a severe storm had caused the O.B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant, its operation already strained by aging equipment and inadequate staff, to lose water pressure. No water came out of the faucets for much of the city. Families – lacking water to drink, bathe, or flush their toilets – lined up at bottled water distribution sites. As tap water began to flow again, the city remained under a boil-water advisory because of contaminants – a problem that preceded the storm.

The city and the state were ill-prepared to handle the scale of the crisis in 2022, despite the disaster not being an entire surprise. State officials knew (and local residents knew that they knew) that conditions at the treatment plant made it vulnerable to the severe weather caused by climate change. Thus, the need discursively to manage inaction. When a winter storm led to a water outage and requests for help by the city of Jackson in 2021, Governor Reeves had framed the city as fiscally irresponsible (Murray, Citation2022). Tax policies limit Mississippi’s capacity to fund infrastructure upgrades. Months before the 2022 water system disaster, Reeves had signed the largest tax cut in Mississippi’s history (Vance, Citation2022).

This discursive maneuver of Reeves – characterizing residents as unwilling (not unable) to pay their water bills – mirrors what I saw in Michigan. However, added to the toolbox is a new tactic to ease government inaction. Conservative politicians in Mississippi and other U.S. states fight disclosures about climate change and systemic racism – disclosures that, among other things, might increase public understanding (and outrage) about the forces that shape the water crises in Jackson and other cities. Joining with governors from fifteen other U.S. states, Reeves had sent a letter to President Biden opposing a new rule, proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, that would require publicly traded companies to disclose their climate related risks and impacts (Warren, Citation2022). The governors argued that this rule would hurt oil and gas companies. The signatories of this letter overlap with the governors – including Reeves – who oppose the teaching of ”critical race theory“ (which they do not clearly define). In March 2022, Reeves signed a bill that bans teaching critical race theory (CRT) in the public schools – spanning kindergarten through high school (K-12) and higher education institutions – of the state (Lynch & Grisham, Citation2022). The vagueness of the law is perhaps a ”feature not a bug.“ Teachers may feel so intimidated that they avoid teaching about racism, unsure if it might be considered CRT. This silencing of critique secures the aging infrastructure of racist ideas, while the aging physical infrastructure in racialized communities crumbles.

As urban crises unfold, technical experts and cultural workers (you and I) are faced with a choice: Do we keep silent and operate strategically in line with the punishment and reward structures of the racist neoliberal order? If we do, can we subvert the system to further justice, or are we drawn inextricably into aiding the ideological and material reproduction of inequitable infrastructure? Do we have (or rather, can we craft) other options? To safeguard lives in Black urban regimes and other racialized communities as they endure the impacts of centuries of racial capitalism, which include climate change, dangerous conditions must be addressed in both the physical infrastructure and the ideological infrastructure that constitute water systems. Inequitable infrastructure forces a descent into carceral geographies as affluent communities barricade themselves in an attempt to ”ride out“ the floods. In the words of the late, great poet of Watts, Wanda Coleman (Citation2020):

It’s raining dirty water all over America….

The Arks are slowly filling with unknown species and new breeds

What happened to the brave? Have they departed with the free?

Think of the gutters crammed with souls gone needlessly to waste….

think of them, deeply injured, as disturbances unresolved.

Notes on Contributor

Alesia Montgomery is an Assistant Professor at UCLA’s Institute of Environment and Sustainability (IoES). An ethnographer, Montgomery studies the environmental justice challenges of low-income, racialized communities. Her book, Greening the Black Urban Regime: The Culture and Commerce of Sustainability in Detroit, focuses on battles over green redevelopment. [email protected]

References

- ASCE (2021). American infrastructure report card. https://infrastructurereportcard.org/

- Christian-Smith, J., Gleick, P. H., Cooley, H., Allen, L., Vanderwarker, A., & Berry, K. A. (2012). A twenty-first century US water policy. Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, W. (2020). A consciousness raising exercise. In Wicked enchantment: Selected poems. Penguin Books Limited.

- Deitz, S., & Meehan, K. (2019). Plumbing poverty: Mapping hot spots of racial and geographic inequality in U.S. household water insecurity. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(4), 1092–1109. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2018.1530587

- Democracy Now (2022). “We can’t go it alone”: Jackson, Miss., Mayor Lumumba on water catastrophe in majority-black city. Democracy Now! https://www.democracynow.org/2022/8/31/jackson_mississippi_mayor_chokwe_antar_lumumba

- Gilmore, R. W. (2011). Beyond the prison industrial complex. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sTPjC-7EDkc

- Lynch, J., & Grisham, J. (2022). Mississippi governor signs into law prohibition on schools teaching critical race theory – CNNPolitics. https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/14/politics/mississippi-critical-race-theory-law/index.html

- McDonald, Y. J., & Jones, N. E. (2018). Drinking water violations and environmental justice in the United States, 2011–2015. American Journal of Public Health, 108(10), 1401–1407. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304621

- Montgomery, A. (2020). Greening the black urban regime: The culture and commerce of sustainability in Detroit. Wayne State University Press.

- Murray, I. (2022). Jackson residents face clean water crisis – as state, local leaders point fingers. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/jackson-residents-face-clean-water-crisis-state-local/story?id=89071225

- Pulido, L. (2016). Flint, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013

- Robinson, C. J. (2000). Black marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. University of North Carolina Press.

- Smith, C. (2013). City water, city life: Water and the infrastructure of ideas in urbanizing Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

- Vance, T. (2022). Gov. Tate Reeves signs Mississippi’s largest tax cut into law. Daily Journal. https://www.djournal.com/news/state-news/gov-tate-reeves-signs-mississippis-largest-tax-cut-into-law/article_aba67377-d5dd-596b-a73b-f84cffb50aa8.html

- Warren, A. (2022). Reeves joins 15 governors in condemning rule requiring businesses to report climate change risks. WLOX. https://www.wlox.com/2022/05/31/reeves-joins-15-governors-condemning-rule-requiring-businesses-report-climate-change-risks/

Infrastructures of Race

Sawyer PhinneyHow does infrastructure weave through lives? What role does race play in reproducing economic power through infrastructures? How do infrastructure inequalities fragment, silence, and leave behind lives?

As Salamanca and Silver (Citation2022) remind us, infrastructures are vital technologies in the configuration of uneven geographies. Thinking through raced processes and colonial legacies, ”infrastructures as technologies“ has become entangled in alternative historical-geographical trajectories that continue to shape racialized political economies of infrastructure across the Global South and North today. Infrastructures are informed by regimes of race and segregation where racialization is a spatial process intimately connected to the planning, governing, financing and operation of infrastructures that enables racial hierarchies to be symbolized through socio-political constructs and materially experienced.

The formation of Black-majority U.S cities reflects the interconnections of infrastructure and race that is reflected in the governing and political economy of localities. Black-majority cities can be understood as liminal urban spaces – as they have moved through a transitional process, from once major seats of power within the Fordist cluster of developed cities in the Global North, to now occupying a place in the shadows of declining cities (see Sugrue (1996/Citation2014). The Great Migration, between 1910 and 1970, involved millions of African Americans fleeing poor economic conditions of the Jim Crow South to industrial and manufacturing urban centers in the Northeast and Midwest (Bouston, Citation2017; Gregory, Citation2005). However, during this period industrial cities still consisted of largely white populations. For instance, in the 1950s, 84% of Detroit’s population was still white. As of 2019, this figure now stands at 14% (U.S Census Bureau, Citation2019). Similar trends exist in other Black-majority U.S cities, such as Baltimore and Cleveland. In the years following 1970, there was an out-migration of white residents away from the inner city into the suburbs, a process referred to as ”white flight.“ This was due to post-war suburbanization in the form of the movement of manufacturing plants out of cities in the search for cheap land, subsidized detached homes and the construction of inter-state highways and underfunding of urban transit. All of this coupled with urban divestment and the decline of manufacturing jobs created infrastructural divides along racialized lines within these metropolitan regions. Out-migration by whites was also and undeniably underpinned by racism. The Federal Housing Authority’s lending guidelines were explicitly racist, instructing banks not to write mortgages in redlined neighbourhoods, or areas with Black residents that were deemed undesirable. The FHA also subsidized the construction of suburbs with overt covenants excluding developers from selling to Black homebuyers.

This history brings to light how race and space played out in housing and job discrimination, and specifically how segregation became more deeply entrenched in the physical space of cities versus suburbs in the United States. These cities are still coping with the infrastructural legacies of segregation, neglect and dispossession from the federally financed development of white suburban enclaves. In many ways, infrastructural inequalities are the products of racial and economic power (i.e racial capitalism) that characterize many Black-majority cities in the Midwest and Northeast today.

Succinctly to summarize the logics of racial capitalism, capital depends upon the social construction of race to reproduce and extract value whereby ”economic value is derived from devaluing spaces, places, and labour of racialized groups of people“ (Ponder, Citation2017, p. 15). According to Lowe (Citation2015, p. 150), capital expands itself by ”seizing upon colonial divisions, identifying particular regions for production and others for neglect, certain populations for exploitation and others for disposal.“ As an analytical framework, racial capitalism brings distinct forms and logics of colonization together into a relational ”global history of colonial modernity“ (Morgensen, Citation2011, p. 65), organized around racial hierarchies and ideologies. Others focus on the more contemporary moments of racial capitalism, such as how forms of racial warfare, working through housing markets (Bonds, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2019), the environment (McClintock, Citation2018; Pulido, Citation2016), policing and mass incarceration (Gilmore, Citation2007; Wang, Citation2018), and logics of finance and urban governance (Jenkins, Citation2021; Ponder, Citation2021).

In narrowing-in on the urban, work in Black geographies has interpreted patterns of urban development as unfolding relationally vis-a-vis Black and white infrastructures in the U.S (Bledsoe & Wright, Citation2019; Purifoy & Seamster, Citation2021). White urban and suburban built environments have developed via the devaluation of Black spaces through seemingly race neutral structures of property ownerships and public finance (Delaney, Citation2010; Taylor, Citation2019). Purifoy and Seamster (Citation2021) discuss the ”creation“ of white development through the persistent predation of Black built environments using complex forms of local governance, special districts, urban planning, and rules of legal jurisdiction (p. 52). Racialized underdevelopment is a key dimension of racial capitalism (Robinson, Citation2000), with the predication of value for white spaces on the devaluation and unmaking of Black places. Kobayashi and Peake (Citation2000) for instance describe racialization as a process, ”by which racialized groups are identified, given stereotypical characteristics, and coerced into specific living conditions, often involving social/spatial segregation and always constituting racialized places“ (p. 393). In this sense, racialization is framed as always having a specific geographic dimension where inequalities between racial groups are operationalized through spatial relations and materiality (Bonds, Citation2013, p. 399).

Clarifying mutual and interconnected processes of racialization working through capitalist relations generates new understandings of infrastructural inequalities across public services vital to social reproduction, such as water or transit, but also through space itself in the form of policing. For example, historical trends of anti-Black violence in the St. Louis Metropolitan area, such as in Ferguson, Missouri, can be related to policies of regressive taxation, fees, fine farming (incarceration for failure to pay municipal and civil fines) to generate revenue by the local government (Bledsoe & Wright, Citation2019, p. 15). The neoliberalization of cities means municipal debt is financialized and funds to pay for municipal services and infrastructure are increasingly provided by the municipal bond market, where local governments become more accountable to creditors than the public and their residents. Austerity urbanism is now operating through complicated legacies of uneven racialized geographies within and between U.S cities (Ponder, Citation2017; Ponder & Omstedt, Citation2019; Pulido, Citation2016; Ranganathan, Citation2016). Thinking through the contemporary dynamics of racial capitalism, we see the embedding of race and space in the extraction of urban infrastructures from a public good to capital asset – through both its privatization and financialization.

Locating the particulars of racial capitalism allows understanding its global reach. Drawing attention to the multiple and overlapping ways in which infrastructure is governed and folded into wider neoliberalization processes, Black-majority cities constitute an attractive new node for financializing investor projects where their only option to finance repairs is through the bond market. Due to their economic vulnerability through urban conditions of white flight and disinvestment that categorize these cities as having a higher risk of default, Black-majority cities have had to pay to municipal bondholders higher interest rates on their bonds. Geographers have rarely focused on the relationship between race and municipal finance, and therefore, have overlooked the functioning of government debt and the overall municipal bond market in legitimating and accruing white racial advantages based on the role that race plays in structuring assessments of municipal creditworthiness (Jenkins, Citation2020). To that end, municipal debt is essential to the development of white America and the underdevelopment of Black America, most visibly in Black-majority cities (Jenkins, Citation2020, p. 210, Citation2021). The racial implications of this have meant these municipalities have been under fiscal stress in managing their debt obligations, leading to long-term austerity measures, such as increasing the cost of local services and reducing the quality of services for their majority- Black residents. In using these finance mechanisms, they have dispossessed Black households from some of the basic needs of survival, such as water. Debt and finance have worked to structure the living conditions of racialized populations through means of disposability and dispossession where investment in white spaces has come at the expense of Black neighbourhoods. The devaluation of Black spaces leads to higher costs of borrowing to access finance to pay for day-to-day local services as poorer Black cities and neighbourhoods are viewed as a higher investment risk. Rather than exclusion, financial inclusion in the municipal bond market becomes an extractive tool to reproduce racialized uneven development.

The privatization and financialization of municipal services and infrastructures delivering those services, are examples illustrating the decisive role that race has played in reproducing power through physical infrastructures. Cities have been central targets of financialization, through infrastructural development (Furlong, Citation2020), as well as debt-led forms of financing to fund basic city government services and social provisioning, such as water and sewer, housing, transit, health care, and education (Peck & Whiteside, Citation2016). For example, debates on the relationship between financialization and neoliberalization emphasize how neoliberal forms of public-private partnerships and other urban governance strategies allow for the speculative infrastructure development in cities (Fainstein & Novy, Citation2019). Other analyses of austerity governance highlight the underfunding and privatization of infrastructure and the retrenchment of public sector spending that impact working-class, racialized and low-income communities (Lobao et al., Citation2009).

The effects of financialization were realized after the 2008 financial crisis in the form of austerity policies and a further dismantling of the social state. Municipalities struggled to manage their increasing debt and downloaded these costs even further onto residents through privatization, outsourcing, cutting back services and higher rates and fees (Davidson & Ward, Citation2018). Governance and finance have made residents in Black-majority cities vulnerable to expulsion, marginalization and dispossession through water infrastructures, fracturing spaces of everyday life and social reproduction. Understanding the neglect and deteriorating water dams, water mains, increased flooding, and toxic lead pipes prevalent in Black-majority cities is pivotal for understanding the contemporary urban crisis and the relationship between infrastructural failure, long-term austerity, and race in post-industrial contexts (Phinney, Citation2022; Silver, Citation2021).

Communities of color and low-income neighbourhoods are targeted by polluting industries. At the same time, people of colour are more likely to be exposed to high levels of fine particulate air pollution (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abf4491), which causes tens of thousands of deaths every year (Pulido et al., Citation1996). Other work has looked at similar forms of environmental racism. In the case of the Flint, Michigan’s water crisis in 2014, both Pulido (Citation2016) and Ranganathan (Citation2016) debate the underlying causes of the city’s lead poisoning through a long-standing, historical devaluation of Black populations. Ranganathan (Citation2016) views the decline of federal and state support to Flint, along with decline of their tax base, as rooted in structural and historical processes of racialization. By tracing periods of white flight, and property depreciation in Flint, Ranganathan describes how these events facilitated water infrastructure abandonment.

Capital flight is not the sole producer of infrastructure abandonment, but Ranganathan (Citation2016) argues it depends also upon a culture of racial liberalism, that is, anti-statist notions of the welfare state based on racist ideologies. Value-weighted concepts rooted in liberal-democratic norms of municipal governance, such as ”best possible use“ of land/resources, are ascribed to by local governments, harming Black spaces which do not fit into such formulations.

As Robinson (Citation1983 [2000], p. 26) has emphasized, ”The tendency of European civilization through capitalism was not to homogenize but to differentiate – to exaggerate regional, subcultural, and dialectical differences into ‘racial’ ones.” Thus, the history of capitalism is connected to differentiation in human value via racial regimes and associated with spatial colonial divisions between possessors (i.e. colonial empires) and the dispossessed. These social relations and geographical forces can be read as technologies of power. Race not only is a social construct but also grows out of physical infrastructures. Today we can see it in the brown-coloured water pouring from taps in Jackson, Mississippi or mass water shut offs in Detroit or the lead poisoning in Flint’s water system. Contemporary urban manifestations of neoliberal forms continue to operate through uneven and unequal geographies of racialized development that divides and conquers the connective tissue to our everyday lives – infrastructures.

Notes on Contributor

Sawyer Phinney currently works as a labour economist for the Greater London Authority doing research on green jobs and skills. Previously, they have worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the Heseltine Institute at the University of Liverpool. In 2022, they completed their PhD in Human Geography at the University of Manchester. Their research interests include municipal finance, racial capitalism, and transformations in urban governance. [email protected]

References

- Bledsoe, A., & Wright, W. J. (2019). The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818805102

- Bonds, A. (2013). Racing economic geography: The place of race in economic geography. Geography Compass, 7(6), 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12049

- Bonds, A. (2019). Race and ethnicity I: Property, race, and the carceral state. Progress in Human Geography, 43(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517751297

- Bouston, L. (2017). Competition in the promised land: Black migrants in northern cities and labor markets. Princeton University Press.

- Davidson, M., & Ward, K. (2018). Cities under austerity. Routledge.

- Delaney, D. (2015). The space that race makes: African American and Afro-Caribbean migrants and the politics of place in the United States and France. University of North Carolina Press.

- Fainstein, S. S., & Novy, J. (2019). Property speculation: Causes and consequences. In C. L. Chu & S. He (Eds.), The speculative city: Emerging forms and norms of the built environment. University of Toronto Press.

- Furlong, K. (2020). Geographies of infrastructure 1: Economies. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519850913

- Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden Gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. University of California Press.

- Gregory, J. (2005). The southern diaspora: How the great migrations of black and white southerners transformed America. University of North Carolina Press.

- Jenkins, D. (2020). Debt and the underdevelopment of Black America. Roundtable 3: Race and money. https://justmoney.org/d-jenkins-debt-and-the-underdevelopment-of-black-america/

- Jenkins, D. (2021). The bonds of inequality: Debt and the making of an American City. University of Chicago Press.

- Kobayashi, A., & Peake, L. (2000). Racism out of place: Thoughts on whiteness and an antiracist geography in the new millennium. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 90(2), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/0004-5608.00202

- Lobao, L., Martin, R., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2009). Rescaling the state: New modes of institutional–territorial organization. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 2(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp001

- Lowe, L. (2015). The intimacies of four continents. Duke University Press.

- McClintock, N. (2018). Urban agriculture, racial capitalism, and resistance in the settler-colonial city. Geography Compass, 12(6), e12373–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12373

- Morgensen, S. L. (2011). The biopolitics of settler colonialism: Right here, right now. Settler Colonial Studies, 1(1), 52–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2011.10648801

- Peck, J., & Whiteside, H. (2016). Financializing Detroit. Economic Geography, 92(3), 235–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1116369

- Phinney, S. (2022). The policing of Black debt: How the municipal bond market regulates the right to water. Urban Geography, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2022.2107257

- Ponder, C. S. (2017). The life and debt of great American cities: Urban reproduction in the time of financialization [Doctoral thesis]. The University of British Colombia.

- Ponder, C. S. (2021). Spatializing the municipal bond market: Urban resilience under racial capitalism. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 111, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.186648

- Ponder, S., & Omstedt, M. (2019). The violence of municipal debt: From interest rate swaps to racialized harm in the Detroit water crisis. Geoforum, 106, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.009

- Pulido, L., Sidawi, S., & Vos, R. O. (1996). An archaeology of environmental racism in Los Angeles. Urban Geography, 17(5), 419–439. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.17.5.419

- Pulido, L. (2016). Flint, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013

- Purifoy, D. M., & Seamster, L. (2021). Creative extraction: Black towns in white space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775820968563

- Ranganathan, M. (2016). Thinking with Flint: Racial liberalism and the roots of an American Water tragedy. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(3), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.120658

- Robinson, C. (1983/2000). Black marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. University of North Carolina Press.

- Salamanca, O., & Silver, J. (2022). In the excess of splintering urbanism: The racialized political economy of infrastructure. Journal of Urban Technology, 29(1), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2021.2009287

- Silver, J. (2021). Decaying infrastructures in the post-industrial city: An urban political ecology of the US pipeline crisis. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 4(3), 756–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619890513

- Sugrue, T. J. (2014). The origins of the urban crisis: Race and inequality in postwar Detroit. Princeton University Press.

- Taylor, K. Y. (2019). Race for profit: How banks and the real estate industry undermined Black homeownership. University of North Carolina Press.

- U.S Census Bureau (2019). QuickFacts: City of Detroit population estimates. American Community Survey Data. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/detroitcitymichigan,US/PST045219

- Wang, J. (2018). Carceral capitalism. Semiotext(e).

Whose Infrastructure is it Anyway?

Astrid R. N. HaasOne of the main jobs of elected governments should be to determine, on behalf of their citizens, how scarce resources are best allocated to optimise benefits. This can be a complex process given their diverse set of preferences. However, a democratic political process assumes one can slice through this complexity and have the citizen’s voice ”heard“ and acted upon accordingly. This, in turn, is the basis of the social contract between the government and its people. As noted, in all contexts, this process is deeply complex. However, it becomes even more so when the number of stakeholders, especially those operating outside the democratic process, grows, and thus accountability lines become increasingly blurred.

An illustrative example of this complexity is the decision-making process with respect to infrastructure investments across many developing countries. One of the most substantial sources of financing for infrastructure for these countries, given the significant resource constraints around the public budget, is from foreign financial assistance. This assistance primarily comes in the form of grants and debt, both concessional and non-concessional, from a host of different bilateral and multilateral partners. These resources can make up a significant share of a government’s budget. In Uganda, for example, total debt as a percentage of GDP has steadily increased over time, reaching 45.5% in 2021 (Deloitte, Citation2022). This is expected to rise even further, as Uganda is taking on more loans to finance its infrastructure portfolio.

Borrowing to finance infrastructure is not particular to developing countries, but the fact that these loans are often inextricably tied to various conditionalities is what makes these cases distinct. Perhaps the most well-known example of conditionalities, are the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), implemented during the 1980s and 1990s. Although these programmes have subsequently been abandoned, due to their overall detrimental economic, political and social effects (Forster et al., Citation2020), the notion of making lending (or granting) conditional, is still the convention even if some of these conditions may be implicit. For example, it may be that the loan will only be disbursed if the government selects a certain type of infrastructure.

A pertinent question therefore arises with respect to the social contract: who gets to decide what investments happen and to whom are the decision-makers accountable? As noted from the outset, governments should be accountable to their citizens. Analogously, assistance funded by foreign government’s budgets, including from their tax revenue, mean that these governments should be accountable to a different set of citizens. Multilateral institutions, like the World Bank, are answerable to their Boards, which in turn are made up of several different countries, albeit in proportions skewed to lenders rather than borrowers. In short, the actors providing the financing for infrastructure have little to no accountability lines to the citizens meant to benefit from the infrastructure.

In these cases, the question becomes whether the investments made in infrastructure connect citizens and strengthen the social contract? Or does it not reflect the prevailing preferences of the end-user, and is therefore potentially divisive? I explore this question through three different infrastructure investments in Uganda. The choice of these cases highlights how the question of ”whose infrastructure,“ can occur irrespective of its type.

Bus Rapid Transit System

Uganda was amongst the many countries required to adopt SAPs in the 1980s and 1990s to qualify for support from the World Bank and the IMF. Amongst a host of conditionalities that were imposed, one involved the removal of government subsidies in conjunction with the privatisation of many public infrastructures. This included urban transport and thus drastically reshaped the public transport landscape. For example, public bus companies that had emerged in Uganda’s post-independence period quite quickly went bankrupt after government support ceased (Behrens et al., Citation2016). This is perhaps unsurprising, given there is hardly any functional public transportation system in the world that is profitable and operating without significant government subsidies (Agarwal, Citation2018). To fill the ensuing void and meet the demand for movement, particularly in cities, a wide-reaching and largely unregulated informal transportation system emerged, which still dominates the transport landscape in Uganda.

Amongst the many challenges that come with an unregulated transportation system, dominated by low-capacity vehicles, is that it cannot meet the increasing demands of rapidly growing cities. To address this gap, the World Bank has once again emerged as a key player in shaping the urban public transport landscape. In Kampala, for example, the World Bank has been promoting the urgent need to introduce mass public transportation. Their preferred technology, as it is across many other African cities, is the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system. As such, they have financed several feasibility studies to move this work forward (IBIS, Citation2010; Ministry of Works & Transport, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). The firms contracted to carry out these feasibility studies are almost universally international, with teams coming in from abroad on short term visits to carry out their work. Big advisory, construction and transit vehicle contracts are at stake, often primarily for foreign companies, if the projects proceed.

It would be difficult to find a resident of Kampala who would not agree that the current transportation system is highly dysfunctional, and most would agree that some form of mass transportation is required. However, only a select few have been consulted in the choice as to whether the BRT is the appropriate technology and, more broadly, how their overall transportation system should be shaped. In fact, the resistance that is forming because of this lack of consultation, is preventing the implementation of the BRT. For example, many of the current transport providers oppose the BRT as they are unclear how they will continue to be involved in the overall transportation system (Spooner et al., Citation2020).

Ironically, therefore, one of the legacies of the SAPs is a disrupted and dysfunctional urban transport system. This in turn has now impacted the emergence of a mass transportation system. Yet during neither period were many of the actual users and providers of the existing system, in other words the intended beneficiaries, consulted.

Expressway

The lack of consultation with the target audience of infrastructure projects is not just a problem of large multilateral development institutions. It is a similar challenge when it comes to bilateral development partners. Currently, China has emerged as one of the most significant actors when it comes to financing and building infrastructure in developing countries (Economist, Citation2022). Much of this is done under the auspices of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and is implemented through various different instruments and by both public and private sector actors. Chinese investment involves all parts of the infrastructure value chain from design, financing, construction, and operation.

The recently completed expressway road between Kampala and Uganda’s main airport, located about 40 km away in the neighbouring municipality of Entebbe, provides numerous insights. From the outset there were several challenges stemming from an overall lack of consultation, as the construction of this road was sole sourced to a Chinese contractor because of direct negotiations between them and the President of Uganda. Lending from China’s Exim Bank has been critical to moving forward with the Entebbe Expressway project, while Chinese firms have played a leading role in all stages of the project (Nambiru, Citation2018).

As infrastructure professionals would understand, there are numerous downsides of sole sourcing of such a large and expensive infrastructure. Most notably, it is likely to significantly increase costs compared to if it was procured under a competitive approach. In this case, this is evidenced by multiple contract renegotiations, which have meant this expressway is now the most expensive road (per km) in the world (Mukiibi, Citation2022). Similar challenges exist with the actual design of the road which, due to a dearth of intersections and exits, means that users, outside those driving to the airport, derive far fewer benefits from it.

The significant burden of funding this road will fall on every tax paying Ugandan for decades to come, as the tolls are unlikely to recover costs. This begs the question of whether citizens, if asked, would have chosen to spend their limited resources on this road, given the prevailing alternative priorities. More generally, it re-enforces the concerns that, where resources are limited such that governments depend on significant outside support for financing infrastructure, the accountability mechanisms between citizens and their own government are substantially weakened.

Markets