Abstract

This paper focuses on how local council members consider public-public contractual spatial planning practices. Our approach addresses concerns over the depoliticisation of planning processes within a neoliberal governmentality. Our findings from three Nordic countries show that some of the council members accept being sidelined from contractual processes. Local council members may thus become complicit political subjects who foster depoliticisation through their own actions. We argue that council members’ interpretations concerning contractual practices give direction, not only to future planning practice, but also to societal understanding of the idea of the political in spatial planning.

Introduction: Contractualism and the Evasion of Local Democracy?

In this paper, we contribute to the discussion concerning the potential threat contractual spatial planning practices present to local democracy. We concentrate on a less studied approach by focusing on local council members’ own perceptions of contractualism in relation to ideas of democracy in planning. In general, contractualism has become an essential tool in the neoliberalisation of governmental actions, linked to the shifting role of the State in spatial governance at the local level (e.g. Morphet, Citation2018; Raco, Citation2013; Van den Hurk & Tasan-Kok, Citation2020). Contractual planning deals with both public-private and, increasingly, public-public collaborative agreements, such as city-regional planning contracts between the State and local authorities.

It has been argued that contractual planning operates within the grey area of democratic control (e.g. Bäcklund et al., Citation2017; Jayasuriya, Citation2002; Tasan-Kok et al., Citation2021). Contractualism is feared to depoliticise planning through the acceptance of economic primacy and creation of complex accountability regimes with new political spaces at a remove from the democratic processes (Clarke & Cochrane, Citation2013; Galland & Tewdwr-Jones, Citation2020; O’Brien & Pike, Citation2019). Slobodian (Citation2018) claims that such depoliticisation is central to neoliberal politics that aims to curb democratic control by creating institutional conditions that work towards market-friendly solutions. Foster et al. (Citation2014) further argue that such governing rationality leads to depoliticised politics inside an instituted neoliberal order. The formal bureaucratic governance logic relying on input legitimacy may thus be subtly replaced by a managerial governance logic emphasising output efficiency (Mäntysalo et al., Citation2011). Consequently, the role of local elected representatives as defining goals for planning is replaced by a less clear one in relation to new spatial governance practices.

In this paper, we aim to make visible how Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish local council members interpret and explain their own role in affecting the content and the processes of public-public spatial planning contracts and discuss whether they consider contractualism a threat to local democracy. We analyse the interpretations of council members in relation to discussions of theoretical accounts of depoliticisation and consider whether local politicians accept current practices or attempt to create alternative agencies. The primary empirical material comprises 495 written comments by municipal council members from the municipalities that participate in contractual planning with the State in these three countries. Our starting point is that following the logic and ideals of the Nordic welfare state, fostering democracy should be in the interests of all parties of public-public contracts (see, e.g. Sager, Citation2009; Schmitt & Smas, Citation2018). This is especially noteworthy when the State designs the contract schemes for the city-regional level, at which there are typically no corresponding city-regional governments nor representative democratic control.

We begin by introducing our theoretical approach that centres on the discussions about contractualism and depoliticisation. After that, we present in more detail the societal context of the study. Next, we set forth methods, empirical findings, and theoretical insights concerning our findings. Finally, we discuss whether some council members are knowingly and through their own actions letting themselves be placed outside the sphere in which politics takes place, thus advancing the depoliticisation of planning.

Contractualism as Political Spaces

Various contractual spatial planning practices have emerged for dealing with challenges, especially in city-regions and cities, often explicitly in addition to and in aid of the established governmental systems. In Peel et al.’s words (2009, p. 407), “the new discourse around the idea of the ‘contract’ […] serves as an essential device to explain, legitimise, and promote a new set of institutional structures, regulatory arrangements and socio-economic relationships between the State and a variety of third parties.” As Janssen-Jansen and van der Veen (Citation2017) point out, contracts attempt to stimulate novel co-creative development and governance. Contracts aim to combine actors’ resources into “flexible co-management” (Amundsen et al., Citation2019, p. 10) to navigate the complexities of value creation where traditional systems fail for one reason or another.

However, within contractual arrangements, it becomes less clear who is doing what under what kind of mandate and by what mechanisms contractual practices attach to existing democratic control and accountability instruments. As Tasan-Kok, van den Hurk, et al. (Citation2019) note, the contractual approach creates fragmented governance practices since, despite clear contracts, there is an abundance of complexities concerning the institutions, norms and relationships of these processes. Tasan-Kok, Atkinson, et al. (Citation2019) claim that in contractual approaches, democratic controls are thin compared to economic ones. Likewise, moving towards contractualism creates exclusive negotiation spaces insulated from democratic processes (Clarke & Cochrane, Citation2013; also Bäcklund et al., Citation2017).

Tewdwr-Jones and Galland (Citation2020) note that these novel spatial planning and development practices are often seen as rolling out market orientation to replace formal state power. Yet, the State has often played a major role in initiating and controlling such activities. The State might have projected an image of retreat (Foster et al., Citation2014), or even presented itself as a barrier to development (Raco, Citation2013). In such a scheme, the State itself announces that its apparatus is incapable of delivering or that the State is not the appropriate actor to steer, and thus new informal forms of governance are in order (Ahlqvist & Moisio, Citation2014; Flinders & Wood, Citation2015). Tewdwr-Jones and Galland (Citation2020) note that contractualism thus enables the State to move away from transparency and public scrutiny.

These discussions point to questions about the nature, position and possibility of democratic control by elected representatives within contractual planning. The role of local politicians as public representatives has been giving way to two distinct new roles. One is that of an executive inner circle politician-manager (Hysing, Citation2013; Johansson, Citation2019; Mair, Citation2013), often corresponding to the top tier of professional politicians with a collegial relationship with civil servant managers and good access to information (Aylott, Citation2016). The other is that of an armslength decision maker with limited and pre-screened information (Brorström & Norbäck, Citation2020). The central question is whether these roles enable space for deliberating and discussing the issues. This reasoning is related to the growing concern that the space for doing politics is being foreclosed and that there is a one-sided tendency for depoliticising planning and development issues (Rancière, Citation2005; Sagoe, Citation2018; Van Wymeersch et al., Citation2020). Our paper focuses on whether local council members recognise these viewpoints and relate to them.

On Depoliticisation

There is a rough consensus that depoliticisation is happening (Foster et al., Citation2014; Hay, Citation2007; Swyngedouw, Citation2011). For Flinders and Wood (Citation2014, p. 135), depoliticisation “essentially refers to the denial of political contingency and the transfer of functions away from elected politicians.” Flinders and Wood (Citation2014, p. 136) note that depoliticisation concerns detaching decision-making from elected representatives and bringing power closer to “those best fitted in different ways to deploy it.” In their outlook, depoliticisation happens through two distinct yet intertwined trends. First, a neoliberalist primacy of the market and the imperative of growth through markets slowly and sporadically marginalise democratic governance, and this plays out as growing distrust in democratic processes. Second, a newfound belief in the State as a counterbalance to the market, brought about by the global financial crisis, gives the state new leeway in asserting its politics.

However, as the market favours not democratic debates but tough decision-making to enable the spatial fixes needed to ground investments (Ahlqvist & Moisio, Citation2014), the State has steered away from reinstating democratic control (see Foster et al., Citation2014). These intersecting aspects – less trust in democratic control and a perceived need to adopt business-like governance – are easing the functioning of neoliberal forces (Blühdorn, Citation2014; Flinders & Wood, Citation2015). Through neoliberal regulation, the State provides imaginaries that depict necessities that foreclose alternative development options (Baeten, Citation2012; Davoudi et al., Citation2021; Luukkonen & Sirviö, Citation2019).

For Foster et al. (Citation2014), depoliticisation is not quite what the first-wave depoliticisation literature states, namely the contraction of political space by creating “realms of necessity” (Hay, Citation2007, p. 81) resulting in political vacuums (Foster et al., Citation2014; Jon & Purcell, Citation2018). While in principle agreeing with the creation of realms of necessity, Foster et al. (Citation2014) state that depoliticisation is not so much about the statecraft of squeezing out politics but a toolbox for politicians to shift responsibilities elsewhere. As Allmendinger (Citation2016) notes, this often happens outside the established local decision-making procedures. However, Foster et al. (Citation2014) argue that a lack of a particular form of democratic control does not necessarily equate to the absence of politics. Hence, we need to be specific about the relation: what does democratic control denote, and what kind of politics – or lack of it – can we see in contractual practices (see Sagoe, Citation2018; Zakhour & Metzger, Citation2018)?

Foster et al. (Citation2014, p. 238) further state that depoliticisation takes place through a “governing rationality of the time” in which institutions and individuals are given responsibilities yet left to act seemingly freely. They claim that such neoliberal rationality is totalitarian yet without a power centre. It thus obscures who hands out the responsibilities. Slobodian (Citation2018) notes that individuals and states alike are to surrender to the knowledge of the economic institutions and system to preserve the necessary ignorance needed for asserting democratic accountability while locking-in market-friendly outcomes. In a Foucaultian sense, such governmentality (Blühdorn, Citation2014; Foucault, Citation2009; Lemke, Citation2002) works through a dispersed web of institutionalised and non-institutionalised forms of governance as well as through programmed individual behaviour. In this overarching scheme, Foster et al. (Citation2014) argue, politicisations are part and parcel of depoliticisation: the actual depoliticisation has happened at the level of instituting neoliberal rationality. Hence, the apparent politicisations that stay within this rationality are “complicit” (Foster et al., Citation2014, p. 236), enforcing the prescribed rationality. This means that the appearance and justification of complicit politics enable the image of everyone doing their jobs as parts of a necessary solution rather than creating spaces and viewpoints for political debates.

Complicit politicisations mark a shift towards decision-making that may be multiple times removed from the political space of its origin (Foster et al., Citation2014). Allmendinger and Haughton (Citation2015) have noted that the politics of spatial planning and development have been taken out of the legally defined transparent systems of planning and development into ambiguous arrangements, not necessarily formally outside established democratic control but misaligned with the existing democratic institutions. Decisions are still being made, just not in the representative democratic system or the way the system is designed to function. As a result, claim Foster et al. (Citation2014), the State has not receded but rolled forward. Hay (Citation2014, p. 307) contends that this roll-forward is not quantitative growth but a change that includes a seemingly receding government as a regulatory apparatus and a “web of governance that has grown in the shadows.”

In our study, this complicitly politicised space is the institutional milieu of contractualism in spatial planning and development practices. We see that, eventually, it is the local elected representatives who either accept this complicity or carve out political currency through agentic choice-making and alternative action. The crucial question in our approach is how council members themselves interpret this situation and their roles in fostering political debates around spatial planning.

Public-Public Spatial Planning Contracts in Finland, Norway and Sweden

The local context of our study is the recent public-public spatial planning and development contracts between the State and the municipalities in Finland, Norway and Sweden. They all have similar starting points: the State wants to provide for economic growth by actively directing investments in the regions it considers competitive.

At the onset, the Finnish State had grown weary of the ineffectiveness of providing vague voluntary frameworks for inter-municipal cooperation at the city-regional level (Mäntysalo & Kosonen, Citation2016). Thus, a contractual approach and focused targets were included, making the process more implementation-oriented than earlier attempts at instigating city-region-level collaboration. Parallel development can be seen in Sweden. Voluntary (city-)regional strategic planning had not turned good intentions into quick investments in the 1990s and 2000s (Fredriksson, Citation2011). Instead, the State relied on sectoral deals for infrastructure provision (Sehested et al., Citation2018). The ground was ready for novel deals: strategic and operationalisable, with clear targets for the State and municipalities alike. Such had already been introduced in Norway since the introduction of city(regional) deals for the Oslo region in the late 1980s (Fredricsson & Smas, Citation2013; Sehested et al., Citation2018; Smas et al., Citation2017), with a recognised need to develop speedier processes with more cross-sectoral actions. Hence, the contractual arrangements in Norway, Sweden and Finland combine integrated planning, strategic goals and operational milestone targets. They all are parallel and only partially complementary to formal spatial planning systems.

However, the contractual arrangements in the three countries have some differences. In Finland, the first contractual spatial planning and development initiatives date to 2011-2012, when the Finnish government started a pilot scheme for land use, housing and transport agreements at the city-regional level. The Finnish government has initiated two frameworks, MAL agreements on land use, housing and transport (MAL-sopimus, since 2012) and innovation ecosystem agreements (Kasvusopimus, since 2016, later called Ekosysteemisopimus) with the major urban regions (Bäcklund et al., Citation2017; Mäntysalo, Kangasoja, et al., Citation2015; Ryöti, Citation2021).

The arrangements involve multi-actor negotiations between the State and the municipalities of select city-regions. The scheme presupposes a city-regional consensus on the contract issues. The negotiations take place outside the formal planning system and utilise informal plans, with consultants and civil servants as information producers (Bäcklund et al., Citation2017; Ryöti, Citation2021). The State is represented by several ministries and state offices, so state presence is strong but also described as internally conflictual (Kanninen, Citation2017). Not all municipalities have representation in the actual negotiations with the State. The outcomes of negotiations concerning the contents of the contract are presented to the municipal councils for approval.

In Norway, two contractual frameworks started as Urban Environment Agreements (Bymiljøavtal, since 2014) and Urban Development Agreements (Byutviklingsavtal, since 2015) were phased into Urban Growth agreements (Byvekstavtal, since 2017). They have aimed at combatting city-regional issues in the largest urban regions (Amundsen et al., Citation2019, Westskog et al., Citation2020). This aim is further supported by the pre-existing public transport-focused rewards scheme (Belønningsavtal, since 2004).

The Norwegian contractual approach builds on the state transport goals that call for sustainability transitions and aims to integrate them with land use in the largest city-regions. The contractual practices are, in principle, connected to the planning system and the processes of local democracy (Amundsen et al., Citation2019; Millstein et al., Citation2016; Smas et al., Citation2017). However, in earlier studies, the State has been described as a strong actor with prescribed design and content for the negotiations (e.g. Amundsen et al., Citation2019). Some of the concerns have been that not all municipalities are necessarily directly involved in the negotiations (Amundsen et al., Citation2019), that there are mismatches between influence and responsibility (Bjørkås & Rasmussen, Citation2020) and that some political decisions have taken place outside the democratic organs (Beck, Citation2015). The outcomes of negotiations are presented to the municipal councils for approval.

The Swedish government has applied three contractual formulas: the Stockholm Negotiations (Stockholmsförhandlingen, from 2013 to 2014), National Negotiation on Housing and Infrastructure (Sverigeförhandlingen, between 2014 and 2017) and Urban Environment Agreements (Stadsmiljöavtalen, since 2015). The ongoing Urban Environment Agreements concern State financial support to the city-regions and an agreement between national and local authorities (Isaksson & Knaggård, Citation2019; Smas et al., Citation2017). The agreements deal with measures towards new transport and housing solutions.

In Sweden, the contractual arrangements concerning Stockholm and National negotiations were based on state-level decisions, and the participants were summoned to deliberations over predetermined agenda concerning national, regional and local transport and infrastructure issues (Näringsdepartementet, Citation2015; Trafikverket, Citation2015). The ongoing urban environment agreements scheme is bid-based, so the State selects the most fitting applicants who receive co-funding. Put together, Isaksson and Knaggård (Citation2019) argue, the Swedish approaches reflect State interests. Agreements are subsequently dealt with at the local level in ways that favour the expert-led processes that lead up to the contracts in the first place. It is unclear which contracts are presented to the municipal councils for approval.

In all three countries, the impact of these contracts is difficult to assess. However ambiguous the actual effectiveness is, the imaginary of the primacy of economic development is well conveyed in the contracts (e.g. Isaksson & Knaggård, Citation2019; Mäntysalo & Kosonen, Citation2016; Smas et al., Citation2017).

Empirical Material and Analytical Framework

Our primary empirical material comprises written comments by local council members concerning contractual planning practices. We collected the material in 2019 as a part of a larger research project Justification for agreement-based approaches in Nordic spatial planning: towards situational direct democracy, funded by the Academy of Finland. A questionnaire was sent to all 7075 council members of those municipalities in Finland, Norway and Sweden (altogether 150) that had signed or were in the process of negotiating (and signed after we collected the data) any of the contracts described in the previous chapter. In total 1018 responses were received.

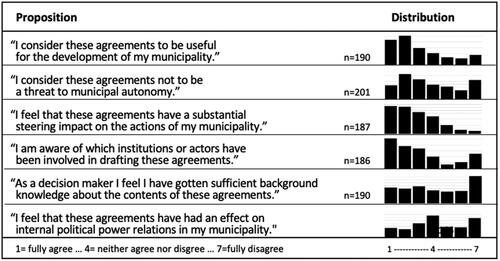

In the questionnaire, we presented propositions concerning, e.g. council members’ knowledge of contractual practices in their municipality and their thoughts concerning the effects of practices on municipal development, planning and decision-making (). We also included open-ended comment possibilities for all these propositions, as we wanted to know the reasoning behind the quantitative choices. Altogether, 216 council members provided 495 open comments of varying lengths. These comments are the primary empirical material for our qualitative analysis.

Those who wrote comments had fair experience in elected representative positions. On average, they had sat in the municipal council for ten years, with the longest experience spanning 46 years and the shortest only a single year. In addition to the municipal council, 93% also had experience with other democratic institutions in their municipality, the city board or boards related to planning, building and transport constituting the most typical ones. In a Nordic context, those having commented were representing small municipalities. Nearly half (46%) were from municipalities with less than 50,000 inhabitants, whereas 37% were from municipalities with more than 100,000 inhabitants.

In the questionnaire, we asked what their subjective evaluation is of their own party’s general ability to affect important decisions in their municipality. Only 15% of those who commented assessed their party as being in a strong position. As much as a third of them stated that it is in a weak position. We thus see that many comments are provided by council members who feel that their own party has limited possibilities to affect essential decisions in their municipality.

Overall, the response profiles to the six propositions presented were identical for all council members (n = 1018) and those who wrote comments (n = 216). The propositions the commenters most agreed with concerned the steering impact of the contracts (average = 2.79 on a scale in which 1 represents total agreement, 4 neutrality, and 7 total disagreement with the proposition), and the usefulness of the contracts (3.12). Correspondingly, the commenting council members disagreed most with propositions about the effect of contracts to political power relations (4.31) and having received sufficient knowledge about the contracts (4,21) ().

The starting point for our qualitative analysis was to shed light on how contractual practices affect the idea of democracy in spatial planning, depending on how council members themselves interpret these practices and their role in them. In analysing the comments, we found that council members were inspired to present their viewpoints, worries and ideas concerning the contractual practices in general, commenting not only on the actual propositions in question. This is common in open-ended comments. Through the broader framework of interpretative policy analysis (Wagenaar, Citation2011), we conducted a content analysis of the written comments based on our theoretical approach. First, we categorized council members’ explanations of their knowledge of the contracts, the contract processes, and the possibilities to participate in them. We interpret these arguments as concretizing the possibly depoliticizing practices of contractualism. Second, we categorized what kind of issues council members brought up in arguing about the importance of contracts and interpreted their arguments in relation to the discourses of neoliberal governmentality. Because of the nature of the data and the analysis method, we did not seek to make general statistical conclusions. Instead, we aimed to make visible the variety of council members’ interpretations to broaden the understanding of how planning practices are directing the idea of the political in planning.

A broader framework for our qualitative content analysis was the common democractic ideal of the Nordic Democracy Model in all of these countries (Aylott, Citation2016), with similar governmental hierarchies and practices of local self-governance. Even if there are some differences in political cultures and practicalities concerning the contracts, the relation between the contracts and local democracy is similar in all countries. In that sense, council members’ attitudes in our empirical material towards public-public contracts can be seen as an example of possible changes in the Nordic Democracy model.

Findings: Are Contractual Practices a Threat to Democracy from the Council Members’ Perspective?

Based on the content analysis of the written comments, we identified four broader themes concerning council members’ interpretations of contractualism: knowledge distribution and actor roles, trust and indifference, the primacy of economic imperatives, and profound critique of contractual schemes.

Knowledge Distribution and Actor Roles

We started our qualitative analysis with the quantitative finding concerning council members’ knowledge of whether their municipality is involved in such contracts. Some 43% of the respondents (n = 1018, total for all countries) were not aware that their municipality was involved. This seems like a high percentage considering that the questionnaire was only sent to the council members of the municipalities having or negotiating one or more of the contracts. In contrast to all council members, 75% of those who had written comments were aware that their municipality was involved in contractual agreements with the State. However, some council members were confused and surprised about not knowing about contracts in their municipality.

If there are no such agreements in my municipality, I am satisfied with the information I have received. If, on the other hand, there are such agreements in my municipality, I do not think I have received enough information. (Finland)

I was the opposition leader at the time, so I should have been aware of the contract! (Sweden)

Differences in council members’ awareness of the contracts can also be explained by the different roles they have in local governance. As Erlingsson and Wänström (Citation2015) and Wänström (Citation2016) note, there has been a shift away in the Nordic from municipal councils being inhabited by lay or leisure politicians (cf. Flinders et al., Citation2019; Gains et al., Citation2004; Stoker et al., Citation2007). Instead, full-time politicians have become dominant, especially in dealing with strategic issues. It would seem appropriate to see the dominant politicians as executive in strategic leadership, in contrast to the lay members who could be described as non-executives, i.e. doing local constituency politics (Stoker et al., Citation2007). In our empirical material, this division was well present.

As a leisure politician, it is at a very late stage that the agreements are presented. It is officials and full-time politicians who have the transparency and power in the process. (Sweden)

These are extensive and complicated topics where many factors must be taken into account. Such nuance and safeguarding of various aspects complicates both the process and the outsiders’ ability to understand and contribute to this (the process). (Norway)

Wänström and colleagues (Erlingsson & Wänström, Citation2015; Wänström, Citation2016) argued that executive politicians and civil servants seek support from each other, thus becoming more powerful together. Such professionalisation of local politics has been accompanied by technicization of much of what used to be within the realm of politics of strategic planning: i.e. preparatory work for many strategic issues and practices such as contract negotiations (see Brorström & Norbäck, Citation2020; Flinders & Wood, Citation2014).

Competent civil servants with a mandate to make decisions alongside the politicians are necessary to move forward. Anchoring and regular reporting as well. Then the steering process is simpler and faster. (Sweden)

An ethnographic study found that Finnish civil servants from different municipalities preparing the MAL agreement for the Helsinki region were well aware of the political nature of their doings (Ryöti, Citation2021). Moreover, they jointly discussed this political nature. They sometimes decided together not to deliver information to council members because they wanted to control which issues should be politicised in preparing contract content. Therefore, we consider it crucial for council members to actively question the content and evidence base of the contracts.

Trust and Indifference: Council Members Yielding Power

The comments that dealt with trust showed confidence in the possibility of gaining more information at will. While we did not ask about trust concerning civil servants’ work, this theme turned up in dozens of comments. Council members indicated that they believed in civil servants’ ability to make decisions concerning the content of the contracts and thus allowed themselves to be partly unaware of the contents and process of the agreements.

I have not seen the agreements but received info about what they contain. That was OK. (Sweden)

As an elected representative, I do not know about these agreements; I am a member of the council and the [planning] board. I believe the people in the City Hall will handle the contracts. (Norway)

Some council members noted that information from civil servants does not suffice, hence they need to be active to get information that enables effective agency. Not knowing was mainly explained by practical issues of council members’ own actions and only in a few cases by the nature of contractual practices.

I would probably get more if I went to talk to the draftsmen. Some things I could influence. However, it takes time and hobby to dig deeper. In meetings, information is scarce. (Finland)

I cannot remember that we in neither the committee nor the municipal board (I am a new member there) received a draft of the agreements. However, I’m sure I would have gotten it if I had asked for it. (Sweden)

In trustee’s actions, many things are often left unexamined, especially when there is not enough time. In addition to the trustee position, you have to take care of your own life, work, hobbies and family. Unfortunately, many trustees often completely follow the proposals of civil service management, and usually only the chairpersons get to know the issues in more detail. (Finland)

Torfing and Ansell (Citation2017) note that the distance between administration and political decision-making tends to increase in collaborative settings. Our findings seem to support this notion. Such distance is about access to information and about being a legitimate actor in the planning process. In theory, this is accompanied by a shift of power to the networks and other arenas of decision-making (Buller & Flinders, Citation2005).

Even when council members in our study recognised their lack of knowledge and the subsequent lack of agency, indifference often prevailed concerning the process behind the contracts:

We are informed about the process and will have the result of the negotiations for political consideration. I hope to be able to completely agree, once the process is finalised. (Norway)

The agreements have been submitted as annexes to the decision-making clauses, and sometimes the official in favour of concluding the agreement has explained in particular the benefits of the agreement. (Finland)

Economic Imperatives: Neoliberal Governmentality

The prevalence of the economy over other aspects of development has often been described as a central feature of neoliberal depoliticisation (Flinders & Wood, Citation2014; Swyngedouw, Citation2011). In our study, the ideas of democratic control and local self-determination seemed to be overtaken by those of economic gains and needs for city-region level collaboration, even in the face of financial costs and inevitably sub-optimal municipal development.

As a municipality, you can sometimes be a little bound by certain contract terms, but if you do not cooperate, it can mean that certain investments do not materialise at all. When you are involved and collaborate, you at least have an opportunity to be involved and influence the content of the agreements. (Norway)

We are a very small municipality as part of the […] region. The […] agreement focuses (quite rightly) on the growth of larger cities, but my own small hometown on the urban border very rarely has directly benefited from these agreements. At best, the benefits are indirect: if the urban area in general grows/develops, crumbs will soon fall on us too. (Finland)

The pervasiveness of constituted economic imaginaries and the central role played by political actors and other interests in creating them has been stressed by authors such as Jessop (Citation2005) and Olesen (Citation2020). Locally, such idealised economic imaginaries unfold as governance arrangements, planning practices and material affordances (Davoudi et al., Citation2021; Luukkonen & Sirviö, Citation2019). Policymakers then perform these for perceived gains within the dominant rationality, reproducing and reinforcing the imaginaries. Overall, the council members’ perceptions and interpretations balanced the possibilities of economic gains with the risks of getting the process and its consequences financially wrong for their municipality.

The agreements would be very useful IF the state would keep its part of the promises, i.e. that you could actually plan for 10 years ahead, i.e. that the projects are of course put in some kind of order, but that all projects that are ready would receive funding, and that you know that even five years in advance. (Finland)

The agreement is useful. But what becomes problematic is the constant transfer of costs from the State to the municipalities, specifically means the attitude of the [agency]. Which in turn affects the possibilities for [contract]. The State does not hold together and speaks with a ‘forked tongue’ towards the municipalities when it comes to partial financing issues. (Sweden)

Critique: Fractures in Governmentality?

Foster et al. (Citation2014) note that complicit politicisations need to be challenged to consolidate governmentality through controlled resistance. In this outlook, resistance politicisation is about criticising the existing norms yet remaining within the current governing rationality. This interpretation was also present in our study, and the resistance seems to work in favour of what Foster et al. consider forming a governmentality-induced neoliberal depoliticisation system. For example, some council members talked about the democratic deficit in local decision-making in explicit terms yet seemed to condition their disapproval by reference to poor economic decisions resulting from the processes.

[T]he State sometimes makes unreasonable demands. A clear example is the State’s requirement for the tramway expansion in the urban environment agreement […]. A BRT or light rail solution (which would be both cheaper and fully sufficient) is excluded only because [of national politics]. The bill for unnecessary overheads thus ends up with the municipality’s taxpayers. (Sweden)

The bigger actors decide what is done in our area, and those decisions do not think at all about what is best for our own municipality. Vice versa! [We are o]bliged to do things that only hinder the growth and development of our own municipality. (Finland)

However, we also interpreted concern over the democratic rationale of contractual practices. Some comments did sidestep from the primacy of the economy to seek better outcomes and more just and transparent processes. We interpret these worries as pointing at the need to have possibilities to politicise the contracts, their content and the process.

Agreements like this are apt to increase the power of civil servants when [agreements] are communicated to trustees in a limited way and not in a timely manner. The civil servant appeals to [the contract] in a meeting, and others do not have time to study the content of the agreement, etc. until it is time for a decision. However, contracts are also questions of interpretation, i.e. how does the trustee know that the civil servant interprets the contract in the only correct way? (Norway)

The agreement has been left aside [from municipal politics] for a long time. A small number of incumbents and a bureau of political decision-makers have highlighted the cost-effectiveness of the agreement. The pursuit of the agreement has become a competition between municipalities, but the municipality’s decision-makers have not been told what the whole is. The agreement has become a sacred liturgy without justification. (Finland)

These statements call for better, genuinely democratic processes. However, we do not know what the contract content would be and who would be the actors if the process was genuinely democratic. Nor do we know what the local people (or constituencies) actually want, or who they even are in the case of selective city-region level contracts. However, the point is not what a genuinely democratic process would entail nor what people would ultimately want but, as Rancière (Citation2005) has argued, whether properly political moments materialise.

I have experienced that my party has been asked by the mayor to leave a group leader meeting due to opposition to one element in a large agreement between the municipality, the county municipality and the State. This has meant that we are completely ignored in a number of cases in the city council that are linked to this agreement. The opposition is extra marginalised as a result. (Norway)

Concluding Discussion: The Interpretations of Council Members Matter

The focus of our qualitative study was to make visible the views of local council members concerning contractual planning. We specifically focused on how council members saw their own possibilities in affecting planning content and processes and how they explain the current situation and their own role in contractual practices. Our empirical material was 495 written commentaries of council members from municipalities participating in contractual planning practices with the State in Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Not unexpectedly, many council members saw multiple challenges and threats in the democractic aspects of contractual practices. Many considered their role in contractual processes to be that of a rubberstamp, presented with take-it-or-leave-it choices in both participating in and deciding the content of the contracts. Furthermore, critical notes concerned the strong power position of the State, which was seen to make contracts one-sided and thus contribute to bypassing local interests. Finally, the critique was directed at contractualism in general. Contracting as an approach was seen to sideline democratic principles. However, surprisingly many council members seemed to accept they cannot affect the contractual processes and know little about the processes or who is orchestrating them. From council members’ explanations of their distance from contractual processes, we recognised three interrelated broader explanatory categories. What is common to these explanations is that they all foster the depoliticisation of both the contents and the processes of contractual planning.

One explanation for accepting the role of an outsider was that contractual planning practices are complex and require high levels of expertise; hence, they are the domain of expert civil servants and executive politicians (also Erlingsson & Wänström, Citation2015). This points to the discussions of the professionalisation of politics and the technicisation of planning issues (Flinders & Wood, Citation2014). In a technicised planning environment, civil servants routinely take responsibility and make decisions about matters that need political debate. Hence, such matters never get to be actively politicised. For the lay council members, this situation means not getting sufficient knowledge of the contractual schemes, as much of the knowledge is distributed only between the experts and the executives.

Another explanation for being an outsider was trusting civil servants’ work. Many council members acknowledged they were unaware of the contractual schemes yet seemed somewhat at ease with their lack of knowing. This is understandable, considering that in the Nordic countries, trust in government and civil servants has been generally high. However, while trust is probably well-placed in general, it is most likely stretched too far if the consequence is that council members remain disinterested in the contractual practices and thus advance the depoliticisation of planning (cf. Torfing & Ansell, Citation2017).

The third explanation was the primacy of ensuring economic development over upholding dimensions of democratic action. While the process and the content of the contractual schemes were seen as flawed, the flaws involved poor economic performance rather than a lack of democracy. We interpret this as the working of neoliberal rationality through economic imaginaries that legitimise the depoliticising practices from the council members’ point of view. As Mäntysalo and colleagues (Citation2011, Mäntysalo, Jarenko, et al., Citation2015) have argued, in such schemes, the power of output efficiency can become politically and practically paramount over that of input legitimacy.

Our focus has been on a specific type of contractual practice, public-public contracts between the State and municipalities. In a public-public setting, all parties are expected to adhere to the principles set to public actors, such as openness, transparency and inclusiveness. In Nordic countries, codified legislation generally obligates public actors to advance democratic principles and to participate in fostering democratic action. In addition, local self-governance is strong both as an ideal and a practice (see Aylott, Citation2016). Thus, the Nordic context is suitable for uncovering flaws in the democratic dimensions of planning. Deviations from codified democractic principles quickly become visible when planning is not done in accordance with the formal planning systems. In other planning systems with less codification or more discretion, the characteristics of contractual planning might not differ from formal planning so obviously. Yet the same implications of depoliticisation still apply.

Our findings show that contractual planning is partially sidestepping both democratic principles and local self-governance. While the formal local decision-making power in contractual planning resides in the local councils, the role of politicians as the watchdogs of democratic ideals is diminished, while their role as managers of economic growth is heightened. This shift becomes more polarising with council members’ complicit indifference that sidelines them from the managerial position, thus giving few experts and executives a prominent role in planning processes. Due to this shift, crucial decision-making occurs inside the expert processes. It seems that what has been considered “arena shifting” (Flinders & Buller, Citation2006, p. 296), in an inter-institutional sense, has been amended with intra-institutional arena shifts that play out within the institutions in planning and governance processes. Thus, we may ponder whether or not this political space, the definitely existing arena where the politics of no alternative and of economic imperative are being instituted, has been re-placed at one or more removes from local representative democracy.

Furthermore, referring to Rancière (Citation2005), we might ask whether this removed action could be considered to have foreclosed real politics. As Ranciere points out, depoliticisation can be seen as a tool for doing politics. In this respect, what we see could be considered part and parcel of politics proper. However, as Flinders and Buller (Citation2006) note, the issue of politics is a matter of balance between de- and repoliticisation. In our empirical material, we found considerations for both more depoliticising actions and calls for repoliticisation.

To conclude, some council members are knowingly letting themselves be placed at a remove from the arenas where politics takes place. Thus, they may become complicit political subjects who uphold neoliberal governmentality instead of defending democratic ideals. We argue that the expressed views and actions of indifference are not just pragmatic solutions or passive resignations, but active unthoughtful deeds in favour of the neoliberal rationalities prescribed by the State. While we have developed our argument in the context of Nordic contractual spatial planning, we see that the self-perception of elected representatives of their role in upholding and advancing democratic values and practices is a fundamental issue for the future of societal decision-making at large, not only in spatial planning.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pia Bäcklund

Pia Bäcklund is a human geographer and a Professor of Urban and Regional Inequalities at the University of Helsinki. Her research concerns e.g. the democratic underpinnings of spatial planning, the politics and processes of city-regional planning, the role of experiential knowledge in spatial planning, and knowledge management practices in public administration.

Vesa Kanninen

Vesa Kanninen is a planning geographer and a Research Coordinator at the University of Helsinki. He holds a doctorate in land use planning and urban studies from Aalto University, Finland. His research focuses on land use planning, strategic planning at the city-regional level, governance of climate-wise housing, as well as theoretical and empirical issues in city-regional collaboration in planning, housing and transport.

Tomas Hanell

Tomas Hanell is a human geographer and a Senior Research Fellow at the Migration Institute of Finland. He holds a doctorate in strategic spatial planning from Aalto University, Finland. His research spans a wide range of regional development and regional planning issues in the Nordic countries, Europe and beyond. His approach is mainly quantitative and has in recent years dealt increasingly with subjective, experience-based data and the new analytical possibilities it brings about.

References

- Ahlqvist, T., & Moisio, S. (2014). Neoliberalisation in a Nordic state: From cartel polity towards a corporate polity in Finland. New Political Economy, 19(1), 21–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2013.768608

- Allmendinger, P. (2016). Neoliberal spatial governance. Routledge.

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2015). Post-political regimes in English planning: From third way to big society. In J. Metzger, P. Allmendinger, & S. Oosterlynck (Eds.), Planning against the political: Democratic deficits in European territorial governance (pp. 29–53). Routledge.

- Amundsen, H., Christiansen, P., Sandkjær Hanssen, G., Hofstad, H., Tønnesen, A., & Westskog, H. (2019). Byvekstavtaler i et flernivåperspektiv: helhetlig styringsverktøy med demokratiske utfordringer [Urban growth agreements in a multi-level perspective: A comprehensive management tool with democratic challenges] (Center for International Climate Research, report 2019:13).

- Aylott, N. (2016). A Nordic model of democracy? Political representation in Northern Europe. In N. Aylott (Ed.), Models of democracy in Nordic and Baltic Europe: political institutions and discourse (pp. 1–38). Routledge.

- Bäcklund, P., Häikiö, L., Leino, H., & Kanninen, V. (2017). Bypassing publicity for getting things done: Between informal and formal planning practices in Finland. Planning Practice & Research, 33(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2017.1378978

- Baeten, G. (2012). Normalising neoliberal planning: The case of Malmö. In T. Tasan-Kok & G. Baeten (Eds.), Contradictions of neoliberal planning (pp. 21–42). Springer.

- Beck, S. (2015). Interkommunalt samarbeid – Supplement til eller uthuling av lokaldemokratiet? En kvalitativ studie av Areal- og transportutvalget i Kristiansandsregionen og dets påvirkning på det tradisjonelle lokaldemokratiet [Inter-municipal cooperation – Supplement to or erosion of local democracy? A qualitative study of the Area and Transport Committee in the Kristiansand region and its impact on traditional local democracy] [Master’s thesis]. Universitetet I Agder.

- Bjørkås, E., & Rasmussen, I. (2020). Evaluering av Grenlandskontrakten 2016. Insentiver, samarbeid og forbedringer til dagens kontrakt [Evaluation of the Grenland contract 2016. Incentives, cooperation and improvements to the current contract] (Vista Analyse 2020/43). Vista Analyse AS.

- Blühdorn, I. (2014). Post-ecologist governmentality: post-democracy, post-politics and the politics of unsustainability. In J. Wilson & E. Swyngedouw (Eds.), The post-political and its discontents: Spaces of depoliticisation, spectres of radical politics (pp. 146–166). Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/j.ctt14brxxs

- Brorström, S., & Norbäck, M. (2020). Keeping politicians at arm’s length: How managers in a collaborative organization deal with the administration–politics interface. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 86(4), 657–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318822090

- Buller, J., & Flinders, M. (2005). The domestic origins of depoliticisation in the area of British economic policy. British. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 7(4), 526–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00205.x

- Clarke, N., & Cochrane, A. (2013). Geographies and politics of localism: The localism of the United Kingdom’s coalition government. Political Geography, 34, 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.03.003

- Davoudi, S., Kallio, K. P., & Häkli, J. (2021). Performing a neoliberal city-regional imaginary: The case of Tampere tramway project. Space and Polity, 25(1), 112–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2021.1885373

- Erlingsson, G., & Wänström, J. (2015). Politik och förvaltning I Svenska kommuner [Politics and administration in Swedish municipalities]. Lund Universitet.

- Flinders, M., & Buller, J. (2006). Depoliticisation: Principles, tactics and tools. British Politics, 1(3), 293–318. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bp.4200016

- Flinders, M., & Wood, M. (2014). Depoliticisation, governance and the state. Policy & Politics, 42(2), 135–149. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655873

- Flinders, M., & Wood, M. (2015). From folk devils to folk heroes: Rethinking the theory of moral panics. Deviant Behavior, 36(8), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2014.951579

- Flinders, M., Wood, M., & Corbett, J. (2019). Anti-politics and democratic innovation. In Handbook of democratic innovation and governance (pp. 148–160). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Foster, E., Kerr, P., & Byrne, C. (2014). Rolling back to roll forward: Depoliticisation and the extension of government. Policy & Politics, 42(2), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655945

- Foucault, M. (2009). Security, territory, population: Lectures at the College de France, 1977–78. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230245075

- Fredricsson, C., & Smas, L. (2013). En granskning av Norges planeringssystem. Scandinavisk detaljplanering i ett internationellt perspektiv [An examination of Norway’s planning system. Scandinavian detailed planning in an international perspective] (Nordregio Report 2013:1). Nordregio.

- Fredriksson, C. (2011). Planning in the ‘New Reality’. Strategic elements and epproaches in Swedish municipalities. Royal Institute of Technology KTH.

- Gains, F., Greasley, S., & Stoker, G. (2004). A Summary of research evidence on new council constitutions in sub-national government (Report, ELG Research Team). University of Manchester.

- Galland, D., & Tewdwr-Jones, M. (2020). Past, present, future: The historical evolution of metropolitan planning conceptions and styles. In K. Zimmermann, D. Galland, & J. Harrison (Eds.), Metropolitan regions, planning and governance (pp. 195–210). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Hay, C. (2007). Why we hate politics. Polity Press.

- Hay, C. (2014). Depoliticisation as process, governance as practice: what did the “first wave” get wrong and do we need a “second wave” to put it right? Policy & Politics, 42(2), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557314X13959960668217

- Hysing, E. (2013). Representative democracy, empowered experts, and citizen participation: visions of green governing. Environmental Politics, 22(6), 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.817760

- Isaksson, A., & Knaggård, Å. (2019). Kunskapsöversikt: Stadsmiljöavtalets politiska process [Knowledge overview: The political process of urban environment agreements] (K2 Working Paper 2019:10). Nationellt Kunskapscentrum för Kollektivtrafik.

- Jayasuriya, K. (2002). The new contractualism: Neo-liberal or democratic? The Political Quarterly, 73(3), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00471

- Janssen-Jansen, L., & van der Veen, M. V. D. (2017). Contracting communities: Conceptualizing Community Benefits Agreements to improve citizen involvement in urban development projects. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(1), 205–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16664730

- Jessop, B. (2005). Cultural political economy, the knowledge-based economy, and the state. In A. Barry & D. Slater (Eds.), The technological economy (pp. 144–166). Routledge.

- Johansson, V. (2019). Is the ability of politicians to act as representatives between elections hampered in systems inspired by NPM? Urban Research & Practice, 12(3), 264–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2018.1444085

- Jon, I., & Purcell, M. (2018). Radical resilience: Autonomous selfmanagement in post-disaster recovery planning and practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1458965

- Kanninen, V. (2017). Strateginen kaupunkiseutu: Spatiaalinen suunnittelu radikaalina yhteensovittamisena [The strategic city-region: Spatial planning as radical coordination]. [Doctoral Dissertations 227/2017]. Aalto University.

- Lemke, T. (2002). Foucault, governmentality, and critique. Rethinking Marxism, 14(3), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/089356902101242288

- Luukkonen, J., & Sirviö, H. (2019). The politics of depoliticization and the constitution of city-regionalism as a dominant spatial-political imaginary in Finland. Political Geography, 73, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.05.004

- Mair, P. (2013). Ruling the void: The hollowing of western democracy. Verso.

- Mäntysalo, R., Saglie, I.-L., & Cars, G. (2011). Between input legitimacy and output efficiency: Defensive routines and agonistic reflectivity in Nordic land-use planning. European Planning Studies, 19(12), 2109–2126. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.632906

- Mäntysalo, R., Kangasoja, J. K., & Kanninen, V. (2015). The paradox of strategic spatial planning: A theoretical outline with a view on Finland. Planning Theory & Practice, 16(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2015.1016548

- Mäntysalo, R., Jarenko, K., Nilsson, K. L., & Saglie, I.-L. (2015). Legitimacy of informal strategic urban planning: Observations from Finland, Sweden and Norway. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.861808

- Mäntysalo, R., & Kosonen, K.-J. (2016). MAL-aiesopimusmenettely ja sen kehittäminen [MAL letter of intent procedure and its development]. In S. Puustinen, R. Mäntysalo, & I. Karppi (Eds.), Strateginen eheyttäminen kaupunkiseuduilla. Näkökulmia kestävän maankäytön ja julkisen talouden kysymyksiin [Strategic integration in urban areas: Perspectives on sustainable land use and public finance issues] (pp. 31–44). Valtioneuvoston kanslia [Prime Minister’s Office].

- Millstein, M., Orderud, G., Hanssen, G., & Stokstad, S. (2016). Staten og bærekraftig byutvikling. En kartlegging av statens ansvar og roller I byutviklingsavtaler [The state and sustainable urban development: A survey of the state’s responsibilities and roles in urban development agreements] (NIBR-rapport 2016:10). NIBR.

- Morphet, J. (2018). Changing contexts in spatial planning: New directions in policies and practices. Routledge.

- Näringsdepartementet (2015). Uppdrag att ta fram förslag till ramverk för stadsmiljöavtal medfocuss på hållbara transporter i städer [Assignment to develop proposals for a framework for urban environment agreements with a focus on sustainable transport in cities]. (Diarienummer: N2015/532/TS). Näringsdepartementet [Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation].

- O’Brien, P., & Pike, A. (2019). Deal or no deal?’Governing urban infrastructure funding and financing in the UK city deals. Urban Studies, 56(7), 1448–1476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018757394

- Olesen, K. (2020). Infrastructure imaginaries: The politics of light rail projects in the age of neoliberalism. Urban Studies, 57(9), 1811–1826. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019853502

- Peel, D., Lloyd, G., & Lord, A. (2009). Business improvement districts and the discourse of contractualism. European Planning Studies, 17(3), 401–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310802618044

- Raco, M. (2013). The new contractualism, the privatization of the welfare state, and the barriers to open source planning. Planning Practice and Research, 28(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.694306

- Rancière, J. (2005). Disagreement: Politics and philosophy. University of Minnesota Press.

- Ryöti, M. (2021). “Tältä tää kaupunkiseutu näyttää”: Visuaalisen esittämisen politiikka alueellisen eriytymisen hallinnassa [“This is how this city-region looks like”: The politics of visualization of residential segregation] [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki]. Department of Geosciences and Geography A96. Unigrafia.

- Sager, T. (2009). Planners’ role: Torn between dialogical ideals and neo-liberal realities. European Planning Studies, 17(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310802513948

- Sagoe, C. (2018). Technologies of mobilising consensus: The politics of producing affordable housing plans for the London Legacy Development Corporation’s planning boundary. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(3), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1478118

- Schmitt, P., & Smas, L. (2018). Shifting political conditions for spatial planning in the Nordic countries. In A. Eraydin & K. Frey (Eds.), Politics and conflict in governance and planning (pp. 133–150). Routledge.

- Sehested, K., Harbo, L. G., & Kanninen, V. (2018). Functional urban regions in nordic countries: Cooperation for sustainable success in spatial planning. (IGN Report). University of Copenhagen.

- Skelcher, C., Klijn, E.-H., Kübler, D., Sørensen, E., & Sullivan, H. (2011). Explaining the democratic anchorage of governance networks: Evidence from four European countries. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 33(1), 7–38. https://doi.org/10.2753/ATP1084-1806330100

- Slobodian, Q. (2018). Globalists: The end of empire and the birth of neoliberalism. Harvard University Press.

- Smas, L., Fredricsson, C., Perjo, L., Anderson, T., Grunfelder, J., & Dymén, C. (2017). Urban contractual policies in Northern Europe (Nordregio Working Paper 2017:3). Nordregio.

- Sørensen, E. (2006). Metagovernance: The changing role of politicians in processes of democratic governance. The American Review of Public Administration, 36(1), 98–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074005282584

- Sørensen, E. (2007). Local politicians and administrators as metagovernors. In M. Marcussen & J. Torfing (Eds.), Democratic network governance in Europe (pp. 89–108). Palgrave.

- Stoker, G., Gains, F., Greasley, S., John, P., & Rao, N. (2007). The new council constitutions. The outcomes and impact of the Local Government Act 2000. Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2011). Interrogating post-democratization: Reclaiming egalitarian political spaces. Political Geography, 30(7), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.001

- Tasan-Kok, T., Atkinson, R., & Refinetti Martins, M. L. (2019). Complex planning landscapes: Regimes, actors, instruments and discourses of contractual urban development. European Planning Studies, 27(6), 1059–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1598018

- Tasan-Kok, T., van den Hurk, M., Ozogul, S., & Bittencour, S. (2019). Changing public accountability mechanisms in the governance of Dutch urban regeneration. European Planning Studies, 27(6), 1107–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1598017

- Tasan-Kok, T., Atkinson, R., & Martins, M. L. R. (2021). Hybrid contractual landscapes of governance: Generation of fragmented regimes of public accountability through urban regeneration. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(2), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420932577

- Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Galland, D. (2020). Planning metropolitan futures, the future of metropolitan planning: in what sense agile? In K. Zimmermann, D. Galland, & J. Harrison (Eds.), Metropolitan regions, planning and governance (pp. 225–236). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Torfing, J., & Ansell, C. (2017). Strengthening political leadership and policy innovation through the expansion of collaborative forms of governance. Public Management Review, 19(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1200662

- Trafikverket (2015). Regeringsuppdrag om stadsmiljöavtal – slutredovisning [Government assignment on urban environment agreement – final report]. (Trafikverket 2015:078). Swedish Transport Administration.

- Van den Hurk, M., & Tasan-Kok, T. (2020). Contractual arrangements and entrepreneurial governance: Flexibility and leeway in urban regeneration projects. Urban Studies, 57(16), 3217–3235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019894277

- Van Wymeersch, E., Vanoutrive, T., & Oosterlynck, S. (2020). Unravelling the concept of social transformation in planning: Inclusion, power changes, and political subjectification in the Oosterweel link road conflict. Planning Theory & Practice, 21(2), 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2020.1752787

- Wagenaar, H. (2011). Meaning in action. Interpretation and dialogue in policy analysis. M.E. Sharpe.

- Wänström, J. (2016). Kommunal styrning och koalitionsbildning i ett nytt parlamentariskt landskap – Utmaningar och möjligheter [Municipal governance and coalition formation in a new parliamentary landscape – Challenges and opportunities] (Centrum för kommunstrategiska studier, Rapport 2016:06). Linköping University.

- Westskog, H., Amundsen, H., Christiansen, P., & Tønnesen, A. (2020). Urban contractual agreements as an adaptive governance strategy: Under what conditions do they work in multi-level cooperation? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(4), 554–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1784115

- Zakhour, S., & Metzger, J. (2018). Placing the action in context: Contrasting public-centered and institutional understandings of democratic planning politics. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(3), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1479441