Abstract

This article offers a detailed ethnographic account of how people appropriate available space in compartments for disabled people in the Mumbai suburban trains, make it their own and monitor it, in the context of a succession of recent spatial changes. These compartments have increased in size over the years, and subsequently, the body of travellers has become more diverse. Passengers produce hierarchies based on need, physical differences, age differences and physical appearance, determining who can enter the compartments and who can’t, who can sit and who should stand, and where they should sit/stand. These hierarchies are mediated, but not dominated, by medical and disability certificates which are, in addition to a valid ticket, the documents that entitle people to travel in the handicapped compartments. Hierarchies are influenced by sexism, classism and audism and partially overlap but also are competing, such as in the case of deaf people who argue for the right to occupy seats and at the same time struggle with how to balance this quest with the need to act morally towards fellow travellers who seemingly suffer.

Résumé

Cet article propose un compte-rendu ethnographique détaillé de la façon dont les gens s’emparent de l’espace dans les compartiments pour les handicappés dans les trains de banlieue de Mumbai, se l’approprient et le contrôlent, dans le contexte d’une succession de changements récents de l’espace. Ces compartiments se sont agrandis au fur et à mesure des années, et, par conséquent, l’ensemble des voyageurs s’est diversifié. Les passagers produisent des hiérarchies fondées sur le besoin, les différences physiques, les différences d’âge et l’apparence physique qui déterminent qui peut et ne peut pas entrer dans les compartiments, qui peut s’asseoir et qui devrait rester debout et où l’on devrait s’asseoir ou rester debout (dans les compartiments ou près des portes). Ces hiérarchies sont arbitrées, mais pas dominées, par des certificats médicaux et des certificats de handicap, qui sont, en plus d’un billet valide, les documents qui donnent droit aux gens de voyager dans les compartiments pour handicappés. Les hiérarchies sont influencées par le sexisme, l’appartenance à une certaine classe ou la capacité d’entendre et se chevauchent partiellement mais aussi se font concurrence, comme dans le cas des sourds qui revendiquent le droit d’occuper les places et en même temps doivent composer avec leur désir d’équilibre entre leur quête et le besoin d’agir moralement envers leurs semblables qui semblent souffrir.

Resumen

En este artículo se ofrece una descripción etnográfica detallada de cómo la gente apropia el espacio disponible en compartimentos para personas con discapacidad en los trenes suburbanos de Mumbai, lo hace suyo y lo vigila, en el contexto de una sucesión de cambios espaciales recientes. Estos compartimentos han aumentado de tamaño en los últimos años, y posteriormente, el cuerpo de los viajeros se ha vuelto más diverso. Los pasajeros producen jerarquías basadas en necesidades, diferencias físicas, diferencias de edad y la apariencia física, determinando quién puede entrar en los compartimentos y quién no, quién puede sentarse y quién debe permanecer de pie, y dónde deben sentarse/pararse (en el compartimiento o cerca de las puertas). Estas jerarquías son mediadas, pero no dominadas, por certificados médicos y de incapacidad que son, además de un billete válido, los documentos que dan derecho a la gente a viajar en los compartimentos para minusválidos. Las jerarquías están influenciadas por el sexismo, el clasismo y el audismo y parcialmente se superponen y también compiten, como en el caso de las personas sordas que pelean por el derecho a ocupar los asientos y al mismo tiempo tienen dificultad para equilibrar esta misión con la necesidad de actuar moralmente hacia compañeros de viaje que al parecer sufren.

Introduction

Saturday 8 February 2014, 9.34 pm, on the way from Dadar to Mulund. It was hard to enter the crowded ‘handicapped compartment’ of the suburban train. The space near the doorways was packed with men, a large part of them seemed to be able-bodied unauthorized travellers. My husband Sujit and me, both deaf, moved to the middle of this 6 by 3 m compartment occupied by about 80 people. A pregnant woman got in sometime after Dadar, and moved towards the spot where we stood. I guessed she was about 7 months pregnant. When I saw her, I poked Sujit. He asked the woman whether she wanted to sit. She replied bitterly: ‘they won’t help’. Sujit gestured to a thin man sitting sideways on a corner of the nearest bench to get up for the woman. He refused. The woman repeated: ‘they won’t help’. A few minutes later the man suddenly got up after all. I thought he was going to alight the train but that was not the case: he joined the crowd near the doorways, moving swiftly. The woman took his seat and asked the two others who were already occupying the bench (designed for two passengers) whether they could shift a bit. They moved grudgingly.

A handsome broad-shouldered and muscled man in a pink T-shirt stood near to us. He had been watching us and eventually signed that he was hearing but had many deaf friends whom he had met in the train, and Sujit and the man conversed through a mixture of gesture and Indian Sign Language. An old man with a turban shuffled in our direction and was scrambling to sit somewhere. Pink T-shirt requested: ‘please have patience’ and told him that he also would like to sit as he had a bad leg. Turban looked annoyed. Somewhat later, Turban got a seat in the back of the compartment when someone got up to alight the compartment. Continuing their conversation, Pink T-shirt and Sujit complained about the mass of unauthorized travellers standing in the hallway. Sujit suggested playfully to pull the emergency brake. Pink T-shirt declined but looked unhappy. He explained that because of his leg, it is really difficult for him to alight the train when it is so crowded ().

The above movements and interactions, described from the point of view of myself as a deaf foreign woman travelling with my deaf Indian husband, happened in a compartment for disabled people in the most intensively used and overcrowded rail network in the world (Cropper & Bhattacharya, Citation2007): the Mumbai suburban trains. These compartments for disabled people have increased in size over the years, and subsequently, the number of travellers has increased and become more diverse, such as the much-contested addition of pregnant women and an increase in the number of able-bodied unauthorized travellers. The question of who has a claim on the space of these reserved compartments and who is the public that can access (seats in) that space or grant access to that space, is central in this article.

Since the 1990s, geographers have successfully and powerfully shown how disabled people are excluded from (particularly urban) spaces, are disabled by barriers in the built environment and have specific mobility needs or preferences (such as Gleeson, Citation1999; Imrie, Citation1996; Kitchin, Citation1998); including in public transport (Hine & Mitchell, Citation2001). This is one of the main foci in what Hall, Chouinard, and Wilton (Citation2010) call the first wave of the geographies of disability. However, rather than focusing on how (semi-)public spaces are made accessible, I look at how citizens self-regulate a segregated space that was seemingly created to enable disabled peoples’ mobility in the city. Here, access becomes something interpersonal, negotiated, contested and defended; and is mediated by arguments and discourses about differences between bodies.

As such, I contribute to the second wave of geographical studies of disability (Hall et al. Citation2010) in which researchers are concerned with bringing the body back into the understanding of disability (cf. Hansen & Philo, Citation2007). Thus, these researchers are moving away from the social model of disability, in which there is emphasis on disabling environments and disabling social processes/attitudes. The social model has been criticized for being one-dimensional, such as by Hansen and Philo (Citation2007) and Shakespeare (Citation2014); the latter argued that we need an interactional approach that focuses on interactions between bodies and (social and material) environments instead.

In this way, this account also contrasts with accounts about top-down implementations, programmes or spaces for disabled people in India created by a neoliberal state or NGOs to situate development interventions, or by corporations to engage in corporate social responsibility initiatives (cf. Friedner & Osborne, Citation2015). Friedner and Osborne argue that the majority of disabled Indians do not benefit from such initiatives, which rather benefit these very corporate actors, the state, NGOs and some middle-to-upper-class disabled individuals. Whilst the reservation of train compartments for disabled people is indeed a top-down implementation as well, this account analyses how diverse commuters themselves decide on, and (try to) implement their ideas on who should benefit from this space.

More particularly, I focus on the real negotiations and contestations that happen in this space where diverse disabled people interact. The diversity of the passenger body leads to the production of hierarchies when negotiating (and arguing about) who can enter the compartments and who can’t, who can sit and who should stand and where they should sit/stand (in the compartment or near the doors). These hierarchies are general but not overpowering directives with regard to entitlement to space in the compartments, produced by diverse commuters, not to be confused with social and religious hierarchies in India or hierarchies of stigma or abilities in general.

There is a tension between formal and informal rules as the produced hierarchies are mediated, but not dominated by the power of medical and disability certificates which are, in addition to a valid ticket, the documents that entitle people to travel in the compartments. Formal (official) regulations as to whom is entitled to travel in the compartments do not suffice here and are sometimes overruled, other times supplemented, as the space is governed by the passengers in the ‘handicapped compartments’ (called HCs from here onwards – ‘handicapped’ is commonly accepted to be an antiquated term in the western context but still in use in Mumbai). There is a connection between the existence of informality and morality. Augé (Citation2002) argues that the ordered and contractual nature of the Métro is found not simply in its explicit regulations but in its ‘collective morality’, the unspoken and complex etiquette that is made necessary by the fact that people travel together in a confined space.

Because the right to occupy (urban) space is a major theme in this article, my approach is reminiscent of Lefebvre’s ‘Right to the City’ (Citation2009) (also see Imrie & Edwards, Citation2007 who argue for further exploring and using Lefebvrian theories in geographies of disability). The creation of informal rules about how to use the space is resonant with Lefebvre’s concept of spatial autogestion; inhabitants manage urban space for themselves as opposed to entirely relying on legal rights (Purcell, Citation2014). The literal translation of autogestion is ‘self-management’, but according to Brenner and Elden (Lefebvre, Citation2009), a better translation is ‘grassroots control’. Lefebvre’s ideal is that people let capitalism and state control ‘wither away’ by taking control of the conditions of their existence, thus organizing a radical, direct grassroots democracy (Lefebvre, Citation2009). Lefebvre applies this larger political vision to a variety of scales such as corporations or nations, and in his concept of the right to the city (see Purcell, Citation2014). This article contributes to a further understanding and specificationof how autogestion works as a ‘territorial mode of self-governance’ (Lefebvre, Citation2009, p. 29): how urban inhabitants claim their ‘right to the city’ by appropriating (partial) control over urban space, in this case the train compartments for disabled people. I will also point out how autogestion is actually a very conflictuous process that is not necessarily leading to a more just space for all.

In this article, I am particularly focusing on the production and contestation of hierarchies by deaf people who travel in the compartments, for two reasons. The first reason is simply the fact that, as a deaf ethnographer focusing on (and participating in) deaf lifeworlds in Mumbai, I had most access to deaf perspectives.Footnote1 Secondly, I noticed that deaf people have had to fight for their entitlement to space in the compartments, often resist the place others give them in the hierarchies, and generally produce different hierarchies than the other commuters, such as putting pregnant women higher in the hierarchy. Thus, in foregrounding deaf experiences and perspectives, I foreground how hierarchies compete in the process of autogestion. ‘Deaf geographies’ have developed largely as a separate strand (see Gulliver & Kitzel, Citation2016; Harold, Citation2013; Valentine & Skelton, Citation2003), however in this article I am not investigating much about what happens when deaf people come together and create deaf spaces in the HCs (see Kusters, Citation2009, in press), but when deaf individuals and groups enter a space where diverse people with disabilities come together and negotiate a limited availability of space.

I start with a description of the methodology and continue with a literature review on reserved and segregated compartments and contestation of space and seats in public transport. Subsequently, I provide a description of the structure and traveller body in the Mumbai suburban trains and the hierarchies produced in its HCs. I then zoom in on deaf people’s, unauthorized passengers’ and pregnant women’s position in the compartments and in the produced hierarchies, thus shedding light on the often fraught, contradictory and ambiguous process that is autogestion.

Methodology

The article is based on ongoing research since 2007, when a first study on the Mumbai trains was undertaken, consisting of exploratory participant observation and two case studies (Kusters, Citation2009). During regular travel in the HCs between 2006 and 2014 (including three years of living in the city); I noted changes in commuters’ spatial practices and space conflicts. I am a Belgian deaf woman and travelled in the compartments as an observer and as a participant, alone or accompanied by others; as friend, tourist, girlfriend, wife, daughter/sister-in-law, pregnant woman and mother; with and without disability certificate. My husband and family in law are deaf Mumbaikars. During all those years, observations and conversations with regard to traveling in the suburban trains were laid down in field notes.

In addition, 12 deaf people were interviewed in Indian Sign Language by myself and Sujit Sahasrabudhe, who was one of the participants in the 2007 study and became my husband and research assistant later on. The interviewed people had various backgrounds with regard to route of travel and destination, religion, age, caste, class and gender. The semi-structured interviews, organized in 2013, focused on the experience of traveling in the HCs, relations and interactions with fellow travellers, and change throughout the years. In addition, in 2013 and 2014, discussions were organized in three local deaf clubs: India Deaf Society (IDS), mainly attended by deaf men of all ages; Yuva Association of the Deaf, a club for deaf youth (18–35 years); and Bombay Foundation of Deaf Women, attended by deaf women of all ages. The audience (50–100 attendees) were asked questions and whomever wanted to reply or comment took the stage, which led to lively discussions. Whilst foregrounding deaf perspectives here, I also draw on written, gestured and sign language interpreted conversations with other disabled travellers, the president of a disabled train commuters advocacy group, railway officials and ticket officers.

Divisions and adjusting in public transport settings

Compartmentalizing in public transport has prevented and protected diverse people from mixing social classes, race and gender. Examples are racial segregation in public transport in the US; the existence of different levels of comfort which were historically associated with different social classes (going from first to fourth class); and the provision of separate services or compartments for ladies in order to prevent sexual harrassment. Today, on most intercity lines, separate classes and categories exist with the eye on comfort (typically 1st and 2nd class) and noise reduction (i.e. installing silent zones). Suburban public transport though is generally uncompartmentalized, in contrast to the Mumbai suburban trains.

A number of authors have analysed how people respond to the close proximity of other bodies in public transport in territorial, adjusting or avoiding ways, such as in Sydney (Symes, Citation2013), Birmingham (Wilson, Citation2011) and New York City (Evans & Wener, Citation2007). In public transport vehicles, there is constant negotiation of space: people occupy space, redistribute space, get up to let others pass by, squeeze past and change seats to give priority (Wilson, Citation2011). Some places have lower value than others, such as the middle seats in case of three adjoining seats (Evans & Wener, Citation2007). People position themselves strategically in ways to occupy the higher value places and to keep others out of their immediate environment as long as possible (Symes, Citation2013; Wilson, Citation2011). There are guidelines and certain understandings of what behaviour is appropriate, certain codes of conduct, which constitute a passenger knowledge. Civil inattention (explicitly disattending to one another whilst recognizing each other’s presence) is practiced along with tacit negotiations, largely based on eye contact, gestures such as pointing or inviting, and helping hands (Bissell, Citation2009). People’s maneouvres in and out of seats and in the queue to get off, or the group to get in, are co-motional, cooperative.

What I am interested in, then, is how people of different abilities participate in, or resist such codes of conduct in and around places that are reserved for people with disabilities. As Wilson (Citation2011, p. 639) observes, in buses in Birmingham, the existence of priority seats near the front door and an area for buggies near the door in the middle means that elderly people sit in the front, those with buggies in the middle and the rear of the bus, and upstairs places are mainly used by younger people – however, importantly, ‘the extent to which such rules are observed and adhered to, remains unmonitored in any official capacity and claims can only be informally exerted’. A number of authors report the unauthorized occupation of reserved seats such as in the Delhi metro (Butcher, Citation2011) and the London metro (Transport for London, Citation2010).

Reserving whole compartments (rather than seats or areas) for people with disabilities seems to be a quite unique phenomenon in the world, in contrast to organizing alternative, entirely segregated transport for disabled people such as dial-a-ride or handicabs (Hine & Mitchell, Citation2001). It is also in contrast to the current trends of Universal Design (Imrie, Citation2012) and shared space (Imrie, Citation2013) aimed at designing spaces that are widely accessible (which Imrie criticized for often being poorly designed with little understanding about the interrelationships between disability and space). (This led to a misunderstanding by a deaf Mumbaikar who had visited Paris and reported that half of the metro was reserved for disabled people – because he had seen a wheelchair logo on the sides.) I am not aware of other instances than India, where separate compartments for disabled people exist in both suburban and most intercity trains.

The Mumbai suburban trains

The population count in the Mumbai Urban Agglomeration was 18 million in 2011 (Bhagat & Jones, Citation2013). The city is located on a peninsula, and the city’s central areas and business district are located in its southern tip. Therefore, many people commute daily from within the entire urban agglomeration to this small area, and the majority of these commuters do so by the suburban railway system, along two North–South lines, called the lifeline or backbone of Mumbai. Everyday about 7 million people ride these commuter trains (Agarwal, Citation2013).

If wanting to travel fast during the rush hour in Mumbai, ironically the least comfortable travel option has to be chosen, in contrary to Cresswell’s (Citation2010) observation that there’s a social division between people who can and cannot afford to pay for fast journeys, and that slow travel infers inferiority. The trains are mainly used by the middle class, but travelling by train is much more affordable than buses and 15% of the poor travel by train (Cropper & Bhattacharya, Citation2007). Thus, the Mumbai suburban trains are used by an extensive and diverse segment of the Mumbai population, they are the trains that everyone rides.

Trains run between 4 am and 1 am with approximately 3-min intervals during peak hours. The morning peak runs from around 7 to 11 am and the evening peak from 4 to 9 pm. During peak times, a single commuter train carries up to 5000 commuters (Badami, Citation2006), most of whom are pressed against each other in ‘super dense crush loads’, a term coined to describe the phenomenon of 14–16 passengers standing per square metre in the Mumbai trains. To negotiate entry to the Mumbai trains during peak times, during the intense shoving and drumming of the dhakka-mukki (scruffle, or push-crush in Hindi and Marathi), who will alight/enter the compartment first (or whether they will enter/alight at all) depends on who is bravest, strongest and fastest. A number of blog articles and online step-by-step how-to guides describes how to negotiate the Mumbai local trains.Footnote2

The Mumbai suburban trains are characterized by ‘physical proximity between citizens whose ethos is geared toward avoidance and social distance between castes, communities and classes. (…) The idea of cohesive densities with common goals is supplemented by a practice and philosophy of “adjusting”’(Rao, Citation2007, p. 231). Phadke, Khan, and Ranade (Citation2011, p. 76) astutely remark that ‘Despite the many hardships attendant to commuting in this city, there is certain insouciance among commuters in Mumbai, both women and men, that has it roots variedly in optimism, resignation, lack of choice and de-sensitization’.

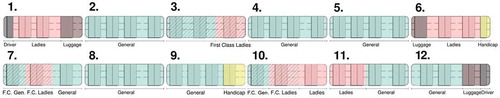

The suburban trains contain the following compartments: general (the largest part of the train), general first class, ladies, ladies first class, luggage (for vendors with loads) and the HCs. These compartments make travel without sexual harrasment possible for women and provide people with disabilities and people with luggage with relatively more space to enter, alight and navigate the compartments ().

Figure 2. The order of compartments in a 12-car maroon old (as opposed to white-purple new) train in Mumbai.

The train windows are barred (for preventing large objects to enter or exit the windows). The doors can be closed but generally remain open in order to let air pass through the compartment and to smoothen the alighting/boarding process which starts when the train is still running; and people hang out of doors and on window bars, and sometimes travel on the roofs.

The HCs and their traveller body

According to a World Bank report (Citation2007), 4–8% of the Indian population is disabled, which would mean that about 720,000–1,440,000 people with disabilities live in Mumbai alone. Causes of disabilities vary from illness, disease and old age to injuries. Following the reasoning that in developing countries at least two out of every 1000 people are deaf, I estimate that there are at least 36,000 deaf people in Mumbai. There are 22 schools for the deaf in Mumbai and a number of deaf clubs.

According to an estimate by the Mumbai-based Disability Advocacy Group (DAG), a disabled train commuters group, about 250,000 commuters travel in the HCs daily (Chaubey, Citation2011). The HCs in Mumbai started in 1993. The driver’s compartments located where carriages were joined were transformed into compartments reserved for disabled people, which measure only about 1, 5 by 3 m. In these compartments, there’s one bench with barely enough space for five people to sit during rush hour, and a number of up to 16 people stand around this bench and next to the doors ().

Figure 3. Sign ‘Reserved for handicapped and cancer patients’ on side of the train next to the door of the HC of an older small ‘handicapped compartment’.

Over the years, the size of the allocated compartments increased: in addition to these small compartments, bigger compartments of about 5 by 3 m were organized in 12-car trains () which started to ride in addition to the older 9-car trains. Then, between 2002 and 2011, under the World Bank financed Mumbai Urban Transport Project (Agarwal, Citation2013), new trains were implemented, which are grey-white with a purple stripe (rather than maroon), are better lit, more spacious, and there are two (in 12-car trains) or three (in 15-car trains) large HCs (about 6 or 7 by 3 m). These compartments contain six benches for two people (occupied by three when it is crowded), one long bench in the back where seven people can sit comfortably and ample standing space (with handholds on the ceiling) ().

When it is very crowded, up to 30 people sit on the benches (designed for 19 people) and many more people stand. Unauthorized travellers mostly stand in the hall of the compartment. On the floor near to the doors, unauthorized travellers such as beggars, transgender, poor non-disabled people, old people and people with leprosy sit, but also disabled (authorized) travellers who prefer to squat rather than sit on a bench, and/or who enjoy the breeze in that area. The space near the doors is thus an ambiguous space: it is an in-between space for people who don’t fully belong, but also a desired place where people can stand or sit in the breeze and can quickly alight the compartment ().

There are a lot of barriers for people with disabilities to get to the compartments: there are no lifts and few ramps in train stations, and to enter or alight the train, people have to negotiate a high step. There are some infrastructural differences between the HCs and the general and ladies’ compartments: there is no pole in the middle of the doorway that would hamper entrance, and benches are designed to hold only two instead of three people. Importantly, it’s not so much the infrastructural difference that makes this place more accessible (in contrast with the trend of Universal Design), but the lower density of commuters. Consequently, the DAG mainly focuses on keeping these compartments free from unauthorized travellers, rather than lobbying for a higher accessibility of trains and train station infrastructure.

A symbol next to the door of the HC shows a wheelchair and a crab (indicating cancer). Travelling in reserved compartments without the right documents (occassionally checked by ticket officers in the train and on platforms) is a breach of the law (section 155 in the Railways Act), and punishable with a fine (500 rs) and jail sentence (3–6 months). The Central Railways chief officer in Mumbai told me that there is not a clear document available on who’s allowed in the HCs, only some general guidelines: people with cancer, disabled people and pregnant women in advanced pregnancy are allowed. Cancer patients carry a ‘cancer card’ and pregnant women have to carry a doctor’s certificate with their due date. The disability certificate can be obtained at Sir Jamshedjee Jeejeebhoy hospital in the city, a tedious process consisting of (medical) investigations and complex bureaucracy. People are allocated a percentage of disability. Profoundly, deaf people who don’t speak get 100%. A senior ticket officer told me that a disability of minimum 40% is necessary, and that people who can see from one eye or have a missing digit are not allowed in, however such people carry a certificate (with their low percentage) and could be often seen in the HCs.

People with disabilities were joined by cancer patients a long while ago, but it’s only since 2011 that women in advanced pregnancy are allowed in the HCs in Mumbai, after a set of complaints from pregnant women for whom it can be extremely stressful and even dangerous to travel in the overcrowded ladies compartments. Women requested bigger ladies’ compartments, which was not possible, and it was decided that they were henceforth entitled to travel in the HC. The rule (written on the sides of a number of trains next to or under the weelchair symbol) is that pregnant women ‘in advanced stage of pregnancy’ could travel in the HC; a vague notion which was open to interpretation but seemed to mean the third trimester of pregnancy.

The traveller body in the HCs mainly consists of people who commute to and from their work and wear neat office outfits. Outside rush hours the traveller body is more diverse, consisting of people who travel for a more varied number of purposes (which is also the case in other compartments): workers with irregular hours, housewives, senior citizens. Most commuters in the HCs are male, though an increasing number of women could be observed in the HCs since the white-purple trains are riding because of the increased size of the HCs in those trains. The majority of passengers are people with disabilities that do not prevent them from negotiating the infrastructural limits of the trains and train stations and/or from commuting to and from school, a course or (office) job in the city. These people, for example, have a deformed hand, a missing arm, leg or toe, have a disability located in their back or leg, are blind or have low vision (and might use a stick) or are deaf. It also happens that people with intellectual disabilities travel accompanied by a member of their family.

In the HC, it is not always immediately obvious that this is a compartment for disabled people – this becomes particularly visible when people are in motion, i. e. enter the HC or move through the HC. Whilst a number of people use one or two walking sticks or crutches, people in wheelchairs or with severe mobility disabilities are typically not seen in the HCs, though a minority of legless travellers use a small handmade board on wheels on which they sit to navigate, and hop in the compartment using their arms.

Autogestion and hierarchies in the HCs

People who enter the compartments are scrutinized for visible signs of disability. It very often happened that my husband and me were addressed (most of the times in a friendly way), by being asked: ‘handicapped?’ (usually in English) as deaf people typically don’t look disabled at first sight. Carrying the disability certificate at all times is a means to avoid or alleviate conflict when people suspect that someone is not a bona fide disabled person, though most of the time a verbal or gestured confirmation is enough. When someone is traveling a certain line regularly around a similar time, a critical mass of travellers comes to know this person’s face, and will defend this person towards others who are not sure who they are.

Whilst the certificates are of great importance to ‘prove’ a disability when negotiating access to the HCs (and the lack of a certificate is used as argument to keep people out), people make use of the certificates in a partial and strategic way. Some people without certificates are actually allowed by fellow travellers (and conductors) because they are disadvantaged in crowds due to young or old age (senior citizens get the exclusive use of a part of the general compartment during allocated non-rush-hour times but are disadvantaged during rush hour), sexual harrassment or body size and weakness, (though not all of them are regarded as having the right to occupy a seat). In other cases, the certificate or allowment does not always convince fellow travellers of someone’s right to enter or to occupy seats (such as in the case of deaf people). This is in line with Lefebvre’s hypothesis that autogestion happens in the ‘weak points’ of society, i.e. where the official frameworks, structures and regulations (in this case, regulations about the use of the HCs) are not powerfully exercised (Lefebvre, Citation2009).

It is very hard to outline an overview of hierarchies that are produced, and such hierarchies are necessarily vague and subjective. I am basing the following enumeration on emic classifications derived from deaf people who were my main interlocutors. In general, people with severe leg and back limitations or pain (with certificate), very old people (without certificate), very sick people (without certificate, but cancer patients have a certificate) and blind people (with certificate) often come higher in the hierarchies. They are followed by moderately sick people (without certificate), people with minor disabilities (with certificate) and deaf people (with certificate): their presence in the compartments is not so much contested, but them getting seats is ambivalent. Next are some ambivalent categories without certificate: (authorized) escorts of people with disabilities, schoolchildren, pregnant women (who often stand near the doors), and yet lower on the hierarchy; there are the people who sit on the floor near the door: hijras (people who are born as men but emasculated, and usually dress as women, and who are part of hijra communities), very poor people without disability and people with leprosy.

I had the impression that most of the time it is not entirely clear what kind of disability or illness someone has. Also, decisions on what categories such as ‘very sick’, ‘moderately sick’ or ‘very poor’ mean are based on what people see and how much suffering people demonstrate or argue that they are experiencing. There is both collective and individual variation in opinions, so hierarchies are competing, leading to struggles and conflicts, which are inherent in Lefebvre’s understanding of autogestion as a framework ‘that not only permits social struggles and contradictions, but actively encourages and provokes them’ (Lefebvre, Citation2009, p. 16). Indeed autogestion is a ‘conflictual, contradictory process through which participants continually engage in self-criticism, debate, deliberation, conflict and struggle; it is not a fixed condition but a level of intense political engagement’, featured by an ‘affirmation of the differences produced in and through that struggle’ (Lefebvre, Citation2009, p. 16).

Other factors that play a role in these negotiations and struggles are: having friends or acquaintances in the compartment or not, passengers’ mood and energy levels and the presence of sexism, ableism, classism and audism. Audism is prejudice towards, and oppression of deaf people because of audiocentric assumptions and attitudes, and can be practiced overtly, covertly and aversively (Eckert & Rowley, Citation2013). An example of audism is mocking or devaluing someone because of their deafness or use of sign language.

Deaf people travelling in the compartments

Deaf people’s experiences of barriers are very different of those of people with other physical disabilities. Deaf people lack full access to auditory languages, and many of them use visual languages (i.e. signed languages) amongst themselves. This orientation towards language has led to intense debates in Deaf Studies and deaf organizations as to whether deaf people are disabled or not. This difference in orientation between deaf and otherwise disabled people is also translated into various kinds of conflicts in the HCs.

When only small HCs were available, deaf people’s presence in these compartments was often contested by people with other disabilities, and there were regular conflicts (through gesturing and physical fights). According to deaf people’s narratives, disabled people put emphasis on physical disability which restricts movements and argued that deaf people thus misuse the valuable and then very limited space in the small HC. Deaf people themselves pointed towards official regulations: their disability certificate allows them to travel in the compartments. They also compared themselves with people with a minimal disability such as a missing finger who also could be said to misuse the space in the HC.

Another argument was mainly used after the dissemination of my research results from 2007 (Kusters, Citation2009), by a subsection of the (aged mainly under 35) Mumbai deaf community. Their discourse references to deaf people’s right to use space for communication in sign language and gesture, which is not possible in the ‘super dense crush loads’ in the other crowded compartments, which are therefore experienced as oppressive environments. As most deaf people work with hearing nonsigning colleagues and live with hearing nonsigning relatives, the HCs became an important place for assembly and a significant language space (Kusters, Citation2009, in press).

Also, whilst deaf people typically might have no physical mobility problems, they encounter another barrier when traveling in the general compartments: no access to information when there are delays or problems with the train. In the HCs they get such information from the other disabled (hearing) passengers in gesture and/or Indian Sign Language. Indeed, a large number of hearing people in the compartments are used to gesture with deaf people and a number of them learned Indian Sign Language to various extents, such as Pink T-shirt in the opening vignette. The HCs thus became a space of socialization and access to information through visual language. What is more, acquaintances and mutual friendships between deaf and otherwise disabled people emerged over time.

Nowadays, deaf people only rarely experience that their presence in the compartment is challenged, saying that prejudices and conflicts diminished over time. Furthermore, on a number of occasions, deaf people fought physically when hearing people wanted to send them out, which, according to them, led to fear or respect and thus to acceptance or tolerance of deaf people’s presence. Also, with the arrival of the white-purple trains and thus larger compartments, the problem of available space became less acute than in the small compartments. Deaf people, when travelling in group, prefer to sit and stand in one of the back corners and on the long back bench (such as in ), explaining that this is because there are less interruptions in conversations, more space for playful behaviour, and they have a better view on what happens in the compartment (such as fights and people entering).

The occupation of seats

There are certain codes of conduct in the Mumbai trains (in general, and not just in the HCs) as to how to manage the occupation of seats: people circulate and swap seats, based on mutual agreements: someone stands for a while (such as until a particular train station) and then swaps with another person who then stands, or claims a seat from someone who will alight at a certain stop. Partaking in these practices is part of ‘collective morality’ (Augé, Citation2002). Small groups of people who commute longer routes and board the compartment when it is still relatively empty, have claimed parts of the compartments, tending to occupy a corner or benches facing each other.

In the HCs, seat-swapping happens particularly between people who know each other, such as friend groups of disabled people, and deaf people make use of the wide deaf network in Mumbai. Deaf-disabled aquaintances and friendships also lead to mutual seat-swapping, as well as pragmatic or strategic reasons: business purposes such as multi-level marketing, or swapping with a hearing disability advocate who can help deaf people to find employment.

People take it upon themselves to allocate their seats rather than just step off and leave it to the rest to sort out, as such strenghtening their connections and friendships, or expressing their views on the hierarchies. Deaf people narrated that when it gets crowded or when it is time to alight, it’s sometimes hard to assess whom to offer their seat: a deaf friend, a disabled person (who has or hasn’t offered them a seat before), a weak-looking person, a very old person, a pregnant woman. It was said that important criteria in such decisions were existing friendships, and when people demonstrate or argue suffering, such as explaining that they are really in pain or very tired after having stood at their work all day.

Whilst it is generally accepted by the other passengers in the compartments that deaf people occupy an area (such as in ), it happens that conflicts and grudges emerge when they do not want to give up seats for disabled people. Indeed, in addition to seat-swapping, another instance of ‘collective morality’ is to promptly pass on seats to people whose bodily conditions put them higher on the hierarchies that exist in the compartments, such as people with a bad leg. During conflicts with disabled people, it appeared that in their eyes, deaf people come lower in the hierarchy of people who deserve seats. A number of deaf people argued that being entitled to enter the compartment also gave them the right to sit down, and complained that deaf people are always the first ones who are asked (or ordered) to get up when someone enters a compartment where all seats are occupied. For example, a deaf young man narrated:

When handicapped people boarded and saw me, they walked to me directly and asked me for a seat. They knew that they would not get a seat from other handicapped people (…), only when someone alights the train. So they prefer to ask deaf people (…). I accepted and stood. I feel that we are cheap.

Whilst some deaf people (happily or grudgingly) obliged, others are fed up with these frequent requests and challenge the requests by gesturing that the requester should seek a seat elsewhere in the compartment. They argue that people with minor handicaps such as in their hand or finger, or escorts of disabled people (see further), can stand up or that disabled people can swap seats with each other, and that deaf people thus should not be ‘targeted’ all the time by people who look for a seat. Deaf interlocutors believed that the reason for being targeted was not only their lack of physical disability but also that they are not expected to be able to talk back in spoken language, hence people gather it is easier to order a deaf person to get up, which is an instance of audism. As a result, deaf people feel stupid, ‘cheap’ and oppressed. The longer the distance, the more conflicts about seats: people seem to be more fixated on comfort, and thus on occupying seats.

Some deaf people said that fights with disabled people and deaf group-based claims of seats were unethical and ableist when people with a painful leg or back need a seat, and also could lead to problematic relationships with disabled people in the longer term which would result in lesser access to seats and information, and they thought it even could result in deaf people being banned from the compartments. They depicted making decisions about refusing versus granting seats as a constant search for a balance which was like walking the tightrope as it involved making choices between accepting instances of audism; oppressing people who experience pain and discomfort (thus exercising ableism); and jeopardizing their position in the compartments (thus compromising opportunities for access and assembly). Switching seats after a number of stops was presented by some as a golden middle way to react on a request: not immediately offering the seat to a disabled person but promising or offering it to him after a number of stops (e.g. by gesturing ‘later’ or ‘5 min’); as such trying to negotiate a higher position on the hierarchy of seat-deserving people than they are initially ascribed by the other, but also trying to exercise morality and show respect for the other. Such mutual struggles and negotiations for power and control over space, mediated (but not dominated) by the need for collective morality, are essential to the process of autogestion.

Unauthorized travellers using the HC as a shortcut

There is a tradition of unauthorized travellers boarding the HC, especially since the size of the compartments increased. People enter the HC (whether or not as a last-minute decision) when the adjoining ladies or general compartment is too crowded, thus using the HC as a shortcut, rather than waiting for the next train. During quiet hours the presence of a few unauthorized travellers does not always lead to inconvenience for disabled commuters, but problems occur when a mass of them is present during rush hour (such as in the opening vignette). Disabled people have difficulties to enter or leave the compartments, and even fall due to the pushing. The HC is also used as an in-between destination by female ‘sojourners’: such women come in, stand next to the door and get off at one of the next stops (such as a smaller station where less people enter the train) in order to enter the adjoining ladies compartment at that point. Standing next to the door means taking into account the invisible boundary with the inner compartment.

In addition to regular checks by ticket officers, disabled commuters take it upon it themselves to monitor and defend the use of the HC (which is another example of autogestion): sending people out politely or telling them off loudly. Particularly, people standing in the doorway were acting as guards. Deaf people are involved with sending unauthorized travellers out, for example, by pointing at the weelchair symbol on the side of the train and on the wall in the compartment. However, whilst this simple gesture is enough to communicate that someone should get out, deaf people are disadvantaged when the encroacher protests in spoken language. In such cases, they leave it to hearing co-passengers to send people out: they are supporting a common purpose here, engaging in autogestion.

Sending out unauthorized travellers is most effective when the compartment is not ‘attacked’ at once by a group of unauthorized travellers. When there are many unauthorized travellers, the latter have the benefit of their number. Some of them threaten disabled passengers who complain about the crowd. Another available option then, is calling the Railway Protection Force (RPF) for assistance, but calling the RPF helpline in case of trouble was seen as pointless because unauthorized travellers can get off before the RPF arrives. During the past few years, control actions by the RPF in the HCs have led to fines, arrests and imprisonments, given wide coverage in newspapers such as DNA, Times of India, Mid-Day and the Asian Age. For example, in 2012, over 2000 unauthorized passengers per month were caught (Chaubey, Citation2012) and 33 offenders were imprisoned during the first 5 months of 2013 (Natu, Citation2013).

The RPF’s interventions, actions and fines have not proved a sufficient deterrant, leading to huge dissatisfaction and regular protest actions organized by the commuters themselves, and the above-mentioned DAG, which were reported in the same newspapers. The DAG, for example, put up posters in the compartments and on the platforms declaring the compartment as a third-class compartment which is allowed for everybody to enter, a kind of dustbin (hereby probably referring to ticketless travellers, see below); organized peaceful protests outside train stations; forcibly checked disabled certificates (see below); and regularly pull the emergency chain (causing to stop the train immediately). Chain pulling is not an unknown practice in the history of India. For example, between 1915 and 1930, chain pulling was done in overcrowded third class compartment in order to draw the attention from the railway authorities to the problem, hoping to be relieved from the circumstances by moving a number of passengers to other compartments (Mitchell, Citation2011). There is thus a combination of commuters appealing to official powers and taking it upon themselves to control the space of the HC (i.e. autogestion) where the execution of this power is regarded to be ineffective or lacking.

Unauthorized travellers who frequent the HC

In addition to the above-mentioned shortcutters, other types of unauthorized travellers travel in the HCs. There are people who come from outside Mumbai (such as from villages) and are unaware (or claim to be unaware) that the compartment is reserved for disabled people. Other unauthorized travellers are fully aware of this and enter the HC as a habit (rather than a shortcut in situations of extreme crowdedness). For example, off-duty policemen tended to travel in the first class in the past, but now that the HCs’ size has increased and often offer more space than the crowded first class compartments, policemen tend to travel in the HCs as well. Policemen can easily silence protesters, misusing their power. Several deaf informants reported having experienced or witnessed harassment and beatings by policemen. The city police has warned their policemen not to travel in the HCs and the DAG organized a petition against the police, but the problem continues.

Non-disabled poor people, beggars and people with an alcohol/drug dependency also frequent the compartment: when they carry an unfresh odour, unclean clothes and/or a strong alcohol smell and/or are ticket-less they are sent away in other compartments and try to board in the HC instead. Other regular unauthorized travellers are people who fake disabilities, injuries, illness or pregnancy, for example, by wearing sunglasses to pretend blindness, by wearing a mouth cloth (which cancer patients often wear in order to filter the air that enters their lungs), by gesturing to pretend deafness, by putting something under the clothes to claim pregnancy, or by wearing a cast or cloths around arms and legs to indicate that they are injured. Alka, a deaf woman in her fifties narrates:

I once saw an old woman with a lot of cloths around her arm and legs, in many colours. She was sending people out, helping blind people in and sending normal people out of the compartment; that was really stupid. So I saw her limp and in Andheri she got off, the train stopped a few minutes there, I saw how she took the cloths off and walked in a brisk way.

Deaf people told me several stories how they caught fake disabled or injured people, but moreover, they are those who best can identify people who fake deafness. When they see that someone’s body or movements does not immediately show a disability or illness, and they ask what he’s doing there, that person may gesture that he is deaf. When deaf people doubt the deafness of that person because that person’s signing or gesturing looks atypical (i.e. ‘not deaf’), they start interrogating, asking questions in Indian Sign Language such as ‘where do you live?’ or ‘where are you going?’. When that person is dumbfounded because they do not understand the signs, deaf people then send them out or report them to conductors or to fellow disabled people.

There are also people who don’t necessarily fake disabilities but carry fake disability certificates instead. During an action in 2012, the DAG forcibly checked the certificates and caught over 100 passengers who travelled in the reserved compartments with fake certificates. They were not authorized to do these checks but were supported by other passengers in the compartments. Thus this is another example of how disabled commuters, feeling a sense of ownership, defend the space that is theirs as they collectively engage in autogestion.

Unauthorized travellers with an ambivalent status

Whilst the above-mentioned unauthorized travellers are not tolerated, there is a fourth kind of unauthorized travellers: people who enjoy an ambivalent status and some of them even have various entitlements to seats. For example, among deaf people was a generally accepted argument that ‘really old people’ were allowed in and should get a seat (even though they had no certificate and had their own reserved section in the general compartment during off-peak), and that old people who in fact still seem fit, could come in but should stand rather than take a seat. They also argued that it strongly depends of how people look and smell. Old people ‘who smell bad and wear dirty clothes’ (in the words of my interlocutors), were sent by fellow passengers to the space near the door or sent out of the compartments, as were the other (of various ages) ‘poor people who smell’.

Sick people, people with fresh injuries or permanent scars, an intravenous infusion, a tube in their nose, a facemask, a brace around their arm or neck or with burns or skin diseases are generally tolerated by conductors and fellow passengers (hence the above-mentioned attempts to fake sickness or injury), though will not always get a seat when it is crowded, again depending of how well they seem to (be able to) care for themselves, how miserable they look, and the mood or characters of their fellow travellers. Hence, people who might be suffering more because poverty leads to lack of means to care for their wounds would be less tolerated; which is an instance of classism. There’s a kind of tipping point in the collective morality which is mediated by poverty. If the disability or misery is present despite having means to care for oneself, then people are more sympathetic.

Another ambivalent category are escorts. Disabled people are allowed to take an escort along with them although there was ambivalence about escorts for deaf adults as they don’t need mobility assistance when they travel. Because of the larger space available in the compartments nowadays, some disabled people more readily take friends or relatives to escort them, whilst in the past, they were more often helped by deaf people to negotiate the step to enter the compartment. Escorts were expected (and thus asked) to stand when seats are in demand (and deaf people argued that escorts, instead of deaf people, should be targeted by people looking for seats).

People with leprosy also tend to board the HC, but sit in the doorway: if they would enter the compartment they would meet with criticism as leprosy is understood to be contagious. Also seen in the doorway are hijras: they also travel in the ladies compartments and first class, but sometimes in the HCs when it is crowded in other compartments. They typically sit on the floor near the door (unless they are disabled), as such not entering the main body of the compartment and avoiding conflict. Disabled people sometimes try to send them out, but mostly leave them alone. Interestingly, hijras do not beg in the HC, whilst they do this in other train compartments. ‘Because handicapped people have problems just like them, they don’t beg’, Rahim, a deaf hijra, explained.

Pregnant women and contested hierarchies

In 2011, when it was announced that pregnant women could travel in the HCs, there was a controversy about this, observable in the trains and covered by Mumbai newspapers. The DAG and disabled people in the compartments argued that pregnant women should get their own compartment, thus supporting further segregation rather than the HC turning into a space to accommodate all kinds of people who cannot travel in the other compartments for a variety of reasons. During multiple incidents, pregnant women who were not believed to be in ‘advanced stage of pregnancy’ were sent out of the compartments, to the extent of aggressive discussions and shouting, and disabled people pulling the emergency brake. In other cases, pregnant women were not sent away but were asked to stand rather than to take a seat.

Several years after the new regulation, I observed that pregnant women were grudgingly tolerated, particularly when they were obviously heavily pregnant, but they still received angry or surly glares from the other (mostly male) commuters and when it was crowded they rarely got a seat (hence the expectation of the pregnant woman in the opening vignette that she would not be helped). On multiple occasions I observed pregnant women entering and standing in the doorways even when there was space to sit, avoiding conflict by signaling not intending to claim a seat.

Deaf people, particularly deaf youth, generally distantiated themselves from these actions and opinions of the other commuters. In deaf-authored hierarchies as to whom to offer a seat first, pregnant women often came either first or second (after blind and very old people, for example). Ritesh, a deaf man in his twenties, told us an anecdote:

The same handicapped person always asks me to get up. I was fed up with that person so when he asked me again, I told him to wait for a few minutes. When a pregnant woman came in, I offered my seat to her instead. I told him to go to the other group of handicapped people who he has known since long time and ask them for a seat.

A number of both male and female young deaf people narrated how they challenged disabled commuters when pregnant women were told to get out or not to occupy seats, gesturing that they didn’t agree and offering their own seat or a vacant seat near them, or by mediating to help pregnant women to a seat from someone else, wanting them to be safe from people bumping against their belly. Also, a number of deaf people didn’t agree with the ‘advanced pregnancy’ rule and argued that women in early pregnancy may feel weak and check those women’s facial expressions and body language to evaluate their need for a seat. Most deaf people said they would give a seat when asked from a pregnant women who seemingly suffers, and not necessarily to a disabled person when a disabled person asks.

Two questions arise then: why did those deaf people express empathy towards pregnant women whilst other people with disabilities seemingly didn’t, and why did those deaf people express more empathy towards pregnant women than towards other people with disabilities? Most importantly, deaf people and pregnant women do not have a history of quarrelling over seats. Deaf people put emphasis on attitude: pregnant women are usually friendly, smile, keep quiet and don’t claim seats. Harish, a deaf man in his early twenties, argued: ‘They do not gesture like: “see, I have a big belly, let me have a seat”, like disabled people do: “see here my leg, I want to sit”’. Deaf people do not feel oppressed (i.e. audism) or challenged by pregnant women and also feel sympathy for a number of reasons.

An additional reason is suggested by Ritesh above: disabled people usually have a certain power and (friend) network in the compartment and can ask or claim a seat from others, which pregnant women cannot. It was also said that the youth deaf club has spread more awareness about sexism and respect for women: whilst pregnant women and people with disabilities (who are mostly men) both could be said to suffer, after returning home after a long day at work, women are the ones to cook, to do the household and tend their family. Furthermore, deaf people are not physically challenged by crowds in the same way as people with other disabilities and might not feel threatened by an increase in categories and numbers of authorised travellers. On the other hand, pregnant women constituted only a very small minority of the passengers, and I frequently got the impression that sexism was involved as well.

Conclusion

During a group discussion in the IDS about the suburban trains in Mumbai, Bhaskar, a young deaf man, suggested that a new rule could be introduced in the HCs. He thought that the number of conflicts would be abated if a reserved-seat area was installed within the compartment; not including deaf people and people with minor disabilities as seat-deserving. As such he suggested the idea of formalizing a binary hierarchy of bodies, in contrast with the complex informal hierarchies that are in play on an everyday basis in these compartments.

Whilst Bhaskar suggests greater official regulation, such a suggestion does not recognize the complex dynamics that are at play in the compartments. Central to Lefebvre’s holistic approach to urban space is the need to look beyond official regulations, and in this line, the analysis in this article documents how people actually inhabit and manage space themselves, i.e. autogestion: ‘In claiming a right to the city, inhabitants take urban space as their own, they appropriate what is properly theirs’ (Purcell, Citation2014, p. 150).

People in the HCs appropriate the space in the HCs by creating regulations in the form of hierarchies that are not just gendered or social, but based on ability, need, age differences, physical appearance and oppression. These differences between people and their diverse bodies, interacting with and within a particular material environment (cf. Shakespeare, Citation2014 on the second wave in the geographies of disability), translate in different claims on and about space as to who can enter, about who can sit, where they can sit, and about who has most/least claim to these places. In producing hierarchies, there are interindividual and collective differences between deaf people and disabled people. Hierarchies are fluid too: who is accepted in the compartment and who will get a seat is contextual, decided on the spot and not a fixed given reality.

Whilst deaf and disabled people act as a common front when keeping unwanted unauthorized travellers out (thus authoring overlapping hierarchies), they also have a history of arguing about deaf people’s right to occupy seats and about pregnant women (thus authoring competing hierarchies). In daily life, deaf people are struggling so that their place in the hierarchy does not become fixed, recognized by all as belonging to the bottom, feeling that might thereby place even their status within the compartments in jeopardy. In fact, they argue for the ‘right to a Deaf-friendly city’ (Harold, Citation2013) where they can assemble and produce sign language spaces, and at the same time struggle with how to balance this quest with moral behaviour towards fellow travellers who suffer: there is pressure for collective morality to be exercised (Augé, Citation2002).

The competing hierarchies exist in contrast to and in addition to the official regulations and disability/medical certificates. Indeed, the fact that travellers engage in autogestion in the space of the HCs does not mean that official regulations are entirely discarded. Instead, in the process of autogestion, people in the HCs make selective and strategic referral to such regulations. People’s production of hierarchies, and their monitoring of the space, is mediated by the medical and disability certificates. People who enter the compartment are scrutinized by other passengers and when they do not look disabled or sick on first sight, they are asked to clarify their entitlement to enter the compartment. However, whilst these certificates are powerful documents, they are used selectively in negotiating or granting access. People without certificate (such as old people) can come high in the hierarchies, and authorized travellers (such as pregnant women) can be sent out of the HCs. The RPF is regularly called upon in cases of problems, but where they fail, the commuters (try to) take it upon themselves to regulate and defend the space of the HCs, with varying rates of success.

The regular disabled passengers in the compartment generally agree on who are definitely unaccepted (as opposed to ambivalent) unauthorized travellers and attempt to defend the space of the compartment against them, becoming audience to any conflict and also becoming involved in it. They implement problem-solving mechanisms and sanctions such as sending people to the space near the door, sending them out verbally or physically, organizing protest actions, pulling the chain or reporting people to the railway police. They thus appeal to officials but also (attempt to) defend the compartment space on their own.

In Lefebvre’s written work, autogestion is described as a mobilization that counteracts state-centred hierarchical organizations and moves towards a decentralization of political power, however, here we see that in asserting power over the use of space in the compartments, new hierarchies are produced, and influenced by sexism, classism, ableism and audism. Indeed, Lefebvre (Citation2009) does not promote ‘autogestion’ as a magic formula that will solve all citizens’ problems. In fact, those of relative privilege (male, hearing, middle/upper class) are exercising relatively more authority over the space in the process of autogestion, not only in enabling but also in oppressive ways, and have a greater claim on comfort during their commute. Indeed ‘autogestion cannot escape this brutal obligation: to constitute itself as a power which is not that of the State’ (Lefebvre, Citation2009, p. 147).

The change of the size of the compartments throughout the years is crucial in claims on space. Passengers in the HC interact directly with each other whilst negotiating the space in the compartment and as such modify the rules over time as to respond to the characteristics of the changing passenger body and the increase in available space. The interactional approach (cf. Shakespeare, Citation2014) adopted in this article allows us to analyse how such changes in material environments and changes in (traveller) bodies that interact with(in) such environments impact upon each other. The competing hierarchies described in this article are in formation and in future years we may witness a regimentation or greater acceptance of a particular hierarchy. On the other hand, would such a regimentation defy the rational logic of autogestion, in which ambiguity, conflict and struggle are central?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mike Gulliver, Michele Friedner, Sujit Sahasrabudhe, three anonymous reviewers and my colleagues at the MPI for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity for their comments on earlier versions of this paper. Thanks to Miete Kusters for designing Figures 2 and 6. And last but not least, thanks to my informants in Mumbai.

Notes

1. My use of the term ‘deaf’ here is meant to cover people who use Indian Sign Language with varying dialects and rates of fluency, and whose hearing loss varies from moderate to total.

2. See, for example, http://www.wikihow.com/Step-off-at-the-Desired-Station-on-a-Mumbai-Local-Train.

References

- Agarwal, A. (2013). Mumbai urban transport project – A multi dimensional approach to improve urban transport. Research in Transportation Economics, 40, 116–123.10.1016/j.retrec.2012.06.029

- Augé, M. (2002). In the Metro. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Badami, S. P. (2006). Urban transport in Mumbai: Two choices for the future. Economic & Political Weekly. 4724–4727.

- Bhagat, R. B., & Jones, G. W. (2013). Population change and migrationin Mumbai Metropolitan Region: Implications for planning and governance. Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

- Bissell, D. (2009). Comfortable bodies: Sedentary affects. Environment and Planning A, 40, 1697–1712.

- Butcher, M. (2011). Cultures of commuting: The mobile negotiation of space and subjectivity on Delhi’s Metro. Mobilities, 6, 237–254.10.1080/17450101.2011.552902

- Chaubey, V. (2011). Is pregnancy a handicap? Mid Day, June 26, 2011.

- Chaubey, V. (2012). Handicapped train commuters oust fakers from their coaches. Mid-Day, November 29, 2012.

- Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28, 17–31.10.1068/d11407

- Cropper, M., & Bhattacharya, S. (2007). Public transport subsidies and affordability in Mumbai, India (Policy Research Working Paper 4395). The World Bank.10.1596/prwp

- Eckert, R. C., & Rowley, A. J. (2013). Audism: A theory and practice of audiocentric privilege. Humanity & Society, 37, 101–130.

- Evans, G. W., & Wener, R. E. (2007). Crowding and personal space invasion on the train: Please don’t make me sit in the middle. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27, 90–94.10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.10.002

- Friedner, M., & Osborne, J. (2015). New disability mobilities and accessibilities in urban India. City & Society, 27, 9–29.

- Gleeson, B. (1999). Geographies of disability. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203266182

- Gulliver, M., & Kitzel, M. B. (2016). Geographies. In G. Gertz & P. Boudreault (Eds.), The deaf studies encyclopedia (pp. 451–453). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Hall, E., Chouinard, V., & Wilton, R. (2010). Towards enabling geographies: ‘Disabled’ bodies and minds in society and space. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hansen, N., & Philo, C. (2007). The normality of doing things differently: Bodies, spaces and disability geography. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 98, 493–506.10.1111/tesg.2007.98.issue-4

- Harold, G. (2013). Reconsidering sound and the city: asserting the right to the deaf-friendly city. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 31, 846–862.10.1068/d3310

- Hine, J., & Mitchell, F. (2001). Better for everyone? Travel experiences and transport exclusion. Urban Studies, 38, 319–332.10.1080/00420980020018619

- Imrie, R. (1996). Disability and the city: International perspectives. London: Paul Chapman.

- Imrie, R. (2012). Universalism, universal design and equitable access to the built environment. Disability & Rehabilitation, 34, 873–882.

- Imrie, R. (2013). Shared space and the post-politics of environmental change. Urban Studies, 50, 3446–3462.10.1177/0042098013482501

- Imrie, R., & Edwards, C. (2007). The geographies of disability: Reflections on the development of a sub-discipline. Geography Compass, 1, 623–640.10.1111/geco.2007.1.issue-3

- Kitchin, R. (1998). ‘Out of place’, ‘knowing one’s place’: Space, power and the exclusion of disabled people. Disability & Society, 13, 343–356.

- Kusters, A. (2009). Deaf on the lifeline of Mumbai. Sign Language Studies, 10, 36–68.

- Kusters, A. (in press). When transport becomes a destination: Deaf spaces and networks on the Mumbai trains. Journal of Cultural Geography.

- Lefebvre, H. (2009). State, space, world: Selected essays (N. Brenner & S. Elden, Eds., G. Moore, N. Brenner, & S. Elden, Trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mitchell, L. (2011). ‘To stop train pull chain’: Writing histories of contemporary political practice. Indian Economic & Social History Review, 48, 469–495.

- Natu, N. (2013). Illegal travel in disabled coaches accounts for 37% of offences on Central Railway till May The Times of India, July 23, 2013.

- Phadke, S., Khan, S., & Ranade, S. (2011). Why loiter? Women and risk on Mumbai streets. New Delhi: Penguin books India.

- Purcell, M. (2014). Possible worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the right to the city. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36, 141–154.10.1111/juaf.12034

- Rao, V. (2007). Proximate distances: The phenomenology of density in Mumbai. Built Environment, 33, 227–248.10.2148/benv.33.2.227

- Shakespeare, T. W. (2014). Disability rights and wrongs revisited. London: Routledge.

- Symes, C. (2013). Entr’acte: Mobile choreography and Sydney rail commuters. Mobilities, 8, 542–559.10.1080/17450101.2012.724840

- Transport for London. (2010). Exploring the journey experiences of disabled commuters. Retrieved from http://www.tfl.gov.uk/cdn/static/cms/documents/Exploring-the-journey-experiences-of-disabled-commuters-report.pdf

- Valentine, G., & Skelton, T. (2003). Living on the edge: The marginalisation and ‘Resistance’ of D/deaf youth. Environment and Planning A, 35, 301–321.10.1068/a3572

- Wilson, H. F. (2011). Passing propinquities in the multicultural city: The everyday encounters of bus passengering. Environment and Planning A, 43, 634–649.10.1068/a43354

- The World Bank. (2007). People with disabilities in India: From commitments to outcomes. Retrieved from http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2009/09/02/000334955_20090902041543/Rendered/PDF/502090WP0Peopl1Box0342042B01PUBLIC1.pdf