ABSTRACT

Policy-makers in industrialised countries have been implementing polices to create neighbourhoods with diverse populations in the hopes of increasing and ameliorating inter-ethnic relations. However, social networks seem to remain largely segregated. The composition of people’s social networks is traditionally explained by population compositions and subsequent meeting opportunities versus preferences for homophilious interaction. Little attention has been paid to the social construction behind these two factors. This study of Turkish and native Dutch individuals in two neighbourhoods in Rotterdam from a time-geographic perspective shows that path-dependency plays a large role in keeping social networks segregated. The social circles individuals engage in during their lives are linked together. Individuals are introduced to places, activities and people by their existing social networks, starting with their parents and siblings. As such, they are likely to roam in spaces dominated by people of their own ethnicity, which lessens the opportunity to meet people from other ethnic backgrounds. This role of people’s existing social networks in ethnic segregation has been overlooked in the integration debate so far.

RÉSUMÉ

Les responsables politiques dans les pays industrialisés ont mis en œuvre des politiques pour créer des quartiers de populations diverses dans l’espoir d’augmenter et d’améliorer les relations inter-ethniques. Pourtant, les réseaux sociaux semblent rester séparés en grande partie. Traditionnellement, on explique la composition des réseaux sociaux des personnes par les compositions de la population et les opportunités de rencontre qui s’ensuivent plutôt que par les préférences d’interaction homophile. On a accordé peu d’attention à la construction sociale derrière ces deux facteurs. Cette étude de personnes turques et d’indigènes néerlandais dans deux quartiers de Rotterdam à partir d’une perspective chrono-géographique montre que la dépendance au sentier joue un rôle important dans le maintien de la ségrégation au niveau des réseaux sociaux. Les cercles sociaux auxquels se joignent les personnes durant leurs vies sont liés ensemble. Les personnes sont mises en contact avec les lieux, les activités et les gens par leurs réseaux sociaux existants, à commencer par leurs parents, frères et sœurs. Par conséquent, il y a de fortes chances qu’elles évoluent dans des lieux dont la prédominance ethnique est la même que la leur, ce qui réduit l’occasion de rencontrer des gens d’autres milieux ethniques. Jusqu’à présent, ce rôle de réseaux sociaux préexistants des personnes dans la ségrégation ethnique n’a pas encore été pris en compte dans le débat sur l’intégration

RESUMEN

Los legisladores de los países industrializados han estado implementando políticas para crear barrios con poblaciones diversas con la esperanza de aumentar y mejorar las relaciones interétnicas. Sin embargo, las redes sociales parecen permanecer en gran parte segregadas. La composición de las redes sociales de la gente se explica tradicionalmente por las composiciones de la población y las oportunidades subsiguientes para reunirse contra preferencias para la interacción hemofílica. Poca atención se ha prestado a la construcción social detrás de estos dos factores. Este estudio de individuos turcos y nativos holandeses en dos barrios de Rotterdam desde una perspectiva temporal-geográfica muestra que la dependencia del camino desempeña un papel importante en mantener a las redes sociales segregadas. Los círculos sociales en los que los individuos se involucran durante sus vidas están unidos entre sí. Los individuos son introducidos a lugares, actividades y personas por sus redes sociales existentes, comenzando con sus padres y hermanos. Como tales, es probable que deambulen en espacios dominados por personas de su propia etnia, lo que disminuye la oportunidad de conocer a gente de otros orígenes étnicos. Este rol de las redes sociales actuales de las personas en la segregación étnica ha sido pasado por alto en el debate de integración hasta el momento.

Introduction

Many industrialised countries have implemented policies to create neighbourhoods with a ‘mixed’ population-composition with regard to socio-economic backgrounds and ethnicity. One of the motivations for such policies is that this will help members of marginalised ethnic minority groups build ‘bridging ties’ (see Granovetter, Citation1973) with the better-off majority group through cross-cutting social circles (see Atkinson & Kintrea, Citation2000; Blau & Schwartz, Citation1984; Simmel in Spykman, Citation2009). The hope is that these bridging ties will facilitate the social mobility of marginalised ethnic minorities and contribute to social cohesion in an era where tolerance of cultural differences has decreased (Amin, Citation2002; Duyvendak, Citation2011; Galster, Citation2007; Ireland, Citation2008; van Kempen & Bolt, Citation2009; Phillips, Citation2010; Van Eijk, Citation2010).

Such policies assume neighbourhoods to be an important setting for meeting opportunities and constructing social ties (Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005; Galster, Citation2007; Ireland, Citation2008; van Kempen & Bolt, Citation2009; Verbrugge, Citation1977). However, recent studies show many contradictions with regard to inter-ethnic relations in mixed neighbourhoods, pointing to more inter-ethnic contacts on the one hand (Blau & Schwartz, Citation1984; Gijsberts & Dagevos, Citation2007b) and socially segregated networks within neighbourhoods on the other (Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005; Park, in Dixon, Citation2006; Schnell & Harpaz, Citation2005; Smets, Citation2005). After all, inter-ethnic contact is not synonymous with inter-ethnic friendship (Musterd & Ostendorf, Citation2009; Valentine, Citation2008). Though some individuals tend to ‘seek diversity’ (see, for instance, Van Eijk, Citation2010; Wilson, Citation2014), people also tend to prefer socialising with people who are similar in terms of age, social and ethnic background, social status and ambition, among other factors (Hamm, Citation2000; Marsden, Citation1988; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, Citation2001; Mollenhorst, Citation2009), and feel alienated and out of place when they are surrounded by people who are ‘different’ (Puwar, Citation2004; Duyvendak, Citation2011).

The neighbourhood mixing approach tends to ignore the pre-conditions for positive inter-group interactions and the reduction of negative prejudice found by Allport (Citation1954/1979) and others (see, for instance, Amir, Citation1969; Pettigrew, Citation1998). These preconditions are, among others, situations of cooperation, shared goals of aspiration and equal status, which implies that (shared) activities are relevant for constructing inter-ethnic ties. In other words, with whom people ‘meet and mate’ (see Verbrugge, Citation1977) is not so much dependent on where they live as it is on the co-presence and encounters that take place at various activity locations that are not necessarily located in one’s residential neighbourhood (Dijst, Citation2009; Drever, Citation2004; Kwan, Citation2012; Urry, Citation2002). Neighbourhood population compositions seem to be less relevant for inter-ethnic contact when individual activity patterns are taken into account (Heringa, Bolt, Dijst, & van Kempen, Citation2014). In modern, motorised and individualised societies with increasingly mobile people, physical (residential) proximity is less important for socialisation (Bauman, Citation2005; Urry, Citation2002; Wellman, Citation2001). At the same time, given ties, like neighbours and relatives, receive less priority than in traditional, collectivist societies (Allan, Citation2001, 2008). Past experiences and the attitudes, routines and social relations individuals have adopted throughout their life trajectories are relevant as well because they influence the daily activity patterns and pre-existing social networks from which new ties are built (Dijst, Citation2006; Elias, Citation1991; Feijten, Citation2005; Giddens, Citation1984; Hägerstrand, Citation1975; Mulder, Citation1993; Pred, Citation1981).

Little can be found in the literature about the activity-patterns of individuals and how they affect social networks. To understand how in-group and inter-group contacts are built, we need to look at the role of the spatio-temporal trajectories of individuals and ‘reassemble the social’ (see Latour, Citation2005; Sheller & Urry, Citation2006). In this paper, we present the findings from our study in Rotterdam, where we followed and interviewed native Dutch and Turkish-Dutch individuals in two neighbourhoods. The main question we pose is as follows:

What is the role of individual spatio-temporal trajectories for the development of ties with members of other ethnic groups, and how is this related to the ethnic composition of the neighbourhood?

In the following section, we will first explain the spatio-temporal approach in relation to social network structures and culture. Next, we illustrate our study of native Dutch and Turkish-Dutch individuals in two neighbourhoods in Rotterdam and discuss the findings. We especially want to draw attention to the importance of prior life trajectories; culturally influenced social orientations and preferences and life paths; and pre-existing ties that reinforce ethnic segregation. With this study, we want to contribute to the debate on (ethnic) integration in an era of increasing (ethnic) diversity (see Tasan-Kok, van Kempen, Raco, & Bolt, Citation2014; Vertovec, Citation2007).

Spatio-temporal approach

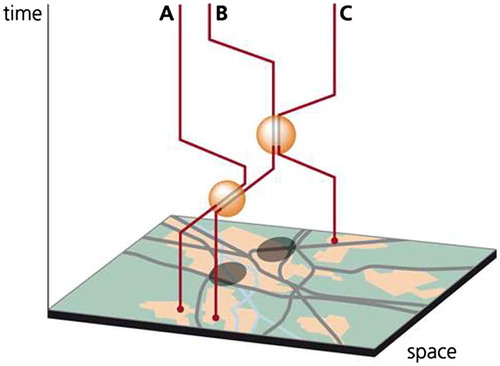

Time geography (developed by Hägerstrand (Citation1970); see also Dijst, Citation2009; Pred, Citation1981) provides a framework for analysing both the spatial and temporal aspects of social phenomena. The basic idea is that every entity has a (life) path across four-dimensional (Cartesian) time–space and is in constant movement. The paths of individuals form the network of which society consists. Spaces where these paths converge are considered ‘bundles’ or ‘stations’ (see ).

Figure 1. Example of time–space diagram showing time-space paths of individuals and bundling of their paths.

Explanation: The time–space diagram above shows the time-space paths of individuals A, B and C. The Z-axis represents the passing time during a day, starting at the bottom; the surface of the X-and Y-axes shows the geographical map of the area in which individuals travel. The circles are the bundles or stations where individuals are co-present and encounter each other in time–space, reflected on the map as a meeting location. The paths of individuals A and B are bundled during travel, with the parallel diagonal lines showing them moving through time and space together. The paths of individuals B and C are bundled at an activity site where both are stationary together and spend time in the presence of the other.

Individuals are not entirely free in choosing their activities and time–space locations. They are limited in their behaviour by capability, authority and coupling constraints because they need to have the cognitive and instrumental capacity to perform certain activities. They, for example, obey biological needs like sleep as well as social and legal rules and the need to synchronise their activities with others. Further, they can only be in one place at a time (Dijst, Citation2009; Hägerstrand, Citation1970; Pred, Citation1981). Many of their activities, like work and childcare, follow from their roles and subsequent obligations, are relatively fixed in time–space and shape their potential action spaces (Dijst, Citation1999). Where choice options in amenities are available within individuals’ potential action spaces in combination with distinct cultural preferences, this may result in members of different (ethnic) groups choosing different activity sites (Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005; Drever, Citation2004). Consequently, schools, shops, travel modes, routes, etc. can be segregated along social and ethnic lines, preventing individual time–space paths from bundling.

Not only the daily paths but also the life paths of individuals are important for understanding activity patterns and social structures (Giddens, Citation1984; Hägerstrand, Citation1975; Lanzendorf, Citation2003; Pred, Citation1981). Individuals have parallel careers with regard to household situations, occupation and residence that influence each other (Feijten, Citation2005; Mulder, Citation1993). For instance, changes in work location, education or household composition are often followed by a change of residence; this (new) home is the base from where daily activities are conducted. The choices made with regard to the different careers and daily activities are shaped by individuals’ goals in life and their preferences, constraints, obligations and societal changes. Path-dependency also exists because future behaviour is embedded in past actions and current situations and depends on the knowledgeability of individuals and the information and values they have obtained through interactions with others (Dyck & Kearns, Citation2006; Elias, Citation1991; Giddens, Citation1984; Hägerstrand, Citation1967; Maslow, Citation1956; Mollenhorst, Citation2009; Mulder, Citation1993; Pred, Citation1981; Spencer & Pahl, Citation2006; Urry, Citation2002).Through the encounters individuals have in their daily paths, they become acquainted with new places, people, objects, ideas and convictions, like religion and cultural values. In this path of diffusion, social structures like ethnic culture are reproduced in adapted form and further shape life and daily paths (Elias, Citation1991; Giddens, Citation1984; Hofstede, Citation2001; Pred, Citation1981).

The values and social norms immigrants bring from their home country are likely to affect their social contacts. Although they may adopt the cultural habits of the host society over time, they may also maintain distinct social orientations and develop hybrid cultures (Sam & Berry, Citation2010). Turkish culture, for instance, is more oriented towards collectivity than Dutch culture; maintaining hierarchy and power distances and avoiding uncertainties are considered more important by the Turks, whereas egalitarianism and adventurous behaviour are valued more by the Dutch. Turks, on average, are also likely to be less free in choosing their life partners and careers than the Dutch (Hofstede, Citation2001; Storms & Bartels, Citation2008; Wessendorf, Citation2013). Family plays a greater role in Turkish lives, and Turks may be less open to new places, activities and people than the Dutch (Hofstede, Citation2001; Wessendorf, Citation2013; Yücesoy, Citation2006). As such, the Turkish minority group in the Netherlands is perceived to be rather inwardly oriented, with relatively little social contact with the native Dutch (Huijnk & Dagevos, Citation2012; Wessendorf, Citation2013). Note that such cultural differences concern group averages (cf. Van Oord, Citation2008). Individual native Dutch people may also adhere more to values of collectivity and hierarchy, whereas Turkish-Dutch individuals may have more egalitarian and individualistic values than native Dutch individuals. Individuals may also be part of other (sub) cultural groups like youth cultures (Van Oord, Citation2008).

Individualistic and collectivist communities differ in the structure of their social networks. In traditional, collectivist societies, social networks are pictured by Simmel (in Spykman, Citation2009) as consisting of concentric circles of family, guild and community, the smaller circles being part of the larger ones (see also Tönnies, Citation1887/2005). Simmel argues that in modern, individualist societies, traditional social circles like family and local community are cross-cut by those of free associations like fraternities. This provides opportunities for interaction between individuals who would otherwise remain in separate circles (see also Blau & Schwartz, Citation1984). Both Simmel and Tönnies portray individuals in these modern societies as rather footloose, easily changing social circles (cf. Spencer & Pahl, Citation2006). In addition, Bauman (Citation2005) argues that the pace of such changes is increasing, creating ‘liquid lives’ where social structures, including human relationships, have little chance of stabilising.

It can be expected that differences in culture, as well as household and socio-economic situations and age, create differences between groups with regard to their (average) activity patterns, social orientations, social networks and subsequent meeting opportunities and interactions. We expect that the population composition of neighbourhoods has only a limited effect on individuals’ social networks because many people are not dependent on the neighbourhood for their social contacts and members of different groups often do not come together in the same social settings. When they do use the same spaces, homophily is likely to favour contact with co-ethnics.

Methodology

In our study, we asked native Dutch and Turkish-DutchFootnote1 residents in two neighbourhoods in Rotterdam to fill in travel and activity diaries for one day, while also recording the types of people they encountered in different locations (age groups, gender, native Dutch and ethnic minorities). In addition, they filled in a questionnaire concerning their socio-economic background, structural activities and social network. We asked about the number of friends and family members in the neighbourhood, the number of native Dutch friends, the number of ethnic minority friends and, for the Turkish-Dutch residents, the number of Turkish friends. We also inquired about the ethnic composition at the workplace or school. Participants were also asked to list the five people most important to them outside the household, the type of relationship (family, neighbour, colleague, etc.) they have. This double measurement allows for the measurement of both the ethnic diversity in the social network and the closeness of inter-ethnic ties (see Smith, Citation2002). On the basis of the questionnaire and the diary, an in-depth interview was held with each respondent.

The two groups were chosen to compare the experiences of an ethnic minority group to that of the native majority. Turkish Dutch were chosen as the ethnic minority group for several reasons: they were the largest non-Western ethnic minority group in the Netherlands in 2011 (CBS Statline). The many Turkish institutions and amenities provide Turkish-Dutch with ample (Turkish) alternatives to Dutch organised venues, making it interesting to study the selection of these venues(see Van Heelsum, Tillie, & Fennema, Citation1999). The relative isolation of Turkish-Dutch in comparison to other ethnic minority groups (cf. Heringa et al., Citation2014; Huijnk & Dagevos, Citation2012; Wessendorf, Citation2013) also makes them an interesting case for studying segregation patterns. The focus was on the age group between 20 and 55 because this is the most dynamic life phase with regard to educational, professional, household and residential careers that impact people’s activity patterns and social network. We also focused on Turkish-Dutch individuals who grew up in the Netherlands because they were not hampered by language barriers and had the opportunity to build inter-ethnic ties from childhood. Rotterdam was chosen because it has the largest Turkish-origin population: approximately 49,000 people at the time of the study (CBS Statline, Citation2011). As a port city, it also historically has been a multicultural society (Blokland, Citation2003; Chorus, Citation2010; Doucet, Citation2010).

For practical reasons (approaching and selecting respondents), and because we wanted to analyse the role of neighbourhoods and their population composition, we selected two neighbourhoods with different population compositions: Afrikaanderwijk and Liskwartier (see for an overview of neighbourhood characteristics). Afrikaanderwijk had the highest concentration of people of Turkish origin in Rotterdam (34%) and only 15% native Dutch residents in 2011 (CBS Statline). It is located south of the Meuse River and is a low-income area with many social rented dwellings. Like most of Rotterdam-South, it is a working-class neighbourhood and has always been an entry point for immigrants, first from the Dutch countryside in approximately 1900, for guest workers from the Mediterranean in the 1960s and 1970s, and now for migrants from Middle and Eastern Europe (Blokland, Citation2003; Chorus, Citation2010). In the past decade, the area has been targeted by urban renewal policies that focused on social mixing and improved transport connections with the city centre (see Doucet, Citation2010). Among its amenities are a marketplace, a swimming pool, a Turkish mosque, and several primary schools and shops.

Table 1. Neighbourhood characteristics in 2011.

Liskwartier’s population is more representative of Rotterdam, with 53% native Dutch and 9% Turkish-Dutch residents in 2011 (CBS Statline). It is located north of the city centre (see ) in between the low-income area of ‘Oude Noorden’ and high-income neighbourhood ‘Hillegersberg’. Like Afrikaanderwijk, it has a mix of single-family dwellings and apartments and has many amenities, including an Islamic university and many Turkish shops and some mosques just outside the neighbourhood boundaries. It has some infrastructure barriers (water, railways) that form the neighbourhood’s boundaries. There are more owner-occupied and private rented houses than in Afrikaanderwijk.

The data were collected in autumn 2011. To collect a varied sample, native Dutch and Turkish-Dutch research assistants approached potential respondents by ringing doorbells at different times of the day in different parts of the neighbourhoods. To increase the diversity in the sample, other potential respondents were approached in the streets of both neighbourhoods or through snowballing. The 39 participants, relatively equally distributed with regard to neighbourhood, gender and ethnicity, were given a €25 voucher that could be spent at a large number of shops.

The interviews took between 30 and 165 min (most approximately 90 min) and were held in the homes of the respondents, except for one. In most cases, it was possible to interview respondents alone, but in some cases, other household members were within hearing distance during (part of) the interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, apart from one interview where the recording failed. The interviews were analysed partly with the help of software for qualitative analysis, and partly manually, using open coding. The diaries were used to reconstruct the daily paths in the interviews, and through the interviews and background questionnaires, the life paths of respondents were reconstructed. To protect the anonymity of the respondents, we used aliases.

Findings

The daily and life paths of our respondents differed greatly, as did their social networks. Some, especially Turkish-Dutch women with children, had activity patterns that were focused on the neighbourhood and its amenities. For others, the residential neighbourhood was a site of passage on their way to work and other destinations located outside the neighbourhood.

Like in many other studies (e.g. Blokland, Citation2003; Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005; Schnell & Harpaz, Citation2005), we found that respondents’ social networks were largely homogeneous with regard to ethnicity, regardless of their residential neighbourhood. Living in an ethnically diverse neighbourhood did not necessarily lead to friendships among other ethnic groups, as respondents did not necessarily socialise with neighbours and often had friends and activities outside the neighbourhood. For those whose network was neighbourhood-based, the presence of ‘sufficient’ co-ethnics facilitated the formation of largely homogeneous social networks within a diverse neighbourhood. This was the case even for respondents who deliberately chose to live in a diverse neighbourhood. As we shall discuss later, this has in part to do with direct relatives, often co-ethnics, receiving priority in relationships and introducing one another to rather homogenous social situations.

Differences in the social network compositions of native Dutch and Turkish-Dutch respondents consisted mainly of geographical distributions, gender divisions and cultural differences in social orientation (focus on family and neighbours or friends and colleagues). These differences could partly be attributed to differing educational and work experiences. To understand how such social segregation comes about, we need to look at how people’s social networks are constructed. In the next subsection, we start with describing the path-dependency of life paths, socialisations and subsequent choices in residential location, activity patterns and social networks. Next, we discuss the priority given to existing ties, the type of ties given priority and openness to bonding with new contacts.

Starting point of individual life paths

Individuals do not arrive in the world free of social bonds. They generally start their lives with a set of parents and other household members as their ties. During childhood, their actual activity space is limited to that of their parents and those trusted by their parents with their care (Elias, Citation1991; Giddens, Citation1984; Visser, Citation2014). These pre-existing ties have a great impact on one’s life and daily paths. Social obligations, like attending birthday celebrations, weddings and other social gatherings, are just one aspect of this (cf. Carrasco & Miller, Citation2009). Friends, family, colleagues and other ties are also an important source of reference for selecting not just ‘base locations’ (like the residential neighbourhood, school and work) but also leisure activities and products like music. And, importantly they introduce one another to each other. In addition to influencing the knowledgeability of individuals, social ties create familiarity with certain spaces, activities and types of people impacting feelings of safety and ‘feeling at home’ (see Duyvendak, Citation2011; Jacobs, Citation1961).

Selection of base locations

Base locations, the centres of the daily paths of individuals to which they return regularly, like the home, school and workplace, influence opportunities for meeting other people (cf. Verbrugge, Citation1977). Base locations are often treated as given in time-geography, but in fact they are social constructs, resulting from human interactions and choices. In the interviews it was evident that the residential neighbourhood indeed played a role in developing the social network of some respondents. However, neighbourhood friendships often dissolve as a result of residential relocations that are related to educational, work and household careers and happen, especially after reaching adulthood. In this sense, there was an important difference between the Turkish-Dutch and native Dutch respondents. All but one of the Turkish-Dutch respondents had not lived in a Dutch town other than Rotterdam, and many had lived in the same neighbourhood all their life. Many of the native Dutch respondents had their roots outside of Rotterdam and those with roots in Rotterdam often no longer lived in their childhood neighbourhood.

This is mainly related to class differences: the native Dutch are generally higher educated and their education or work has required them to relocate to Rotterdam at one point or the other (cf. Feijten, Citation2005; Mulder, Citation1993; Spencer & Pahl, Citation2006). For the Turkish-Dutch, this was less often the case: those who studied in higher education or worked in skilled jobs were often born in Rotterdam and did not need to relocate to participate in education or work. Those who worked or studied outside Rotterdam could travel there from their childhood neighbourhood. Not only did the Turkish-Dutch respondents themselves relocate less often to other towns, so did their (Turkish) friends and relatives. In the case of some native Dutch, working-class respondents in Afrikaanderwijk, though the respondents themselves remained in their childhood neighbourhood, many relatives and friends in the neighbourhood had moved to other towns.

As a result, the social networks of native Dutch respondents were more geographically dispersed than those of the Turkish-Dutch. Although among the native Dutch respondents, there were also people whose social network was primarily neighbourhood-based, for the native Dutch, the social ties were more located in different neighbourhoods, cities and, in some instances, remote provinces (more than 100 km away). Some of the native Dutch did not mention people in Rotterdam at all, whereas for the Turkish-Dutch, the farthest social network members within the Netherlands were located some 50 km away;Footnote2 most lived in the same neighbourhood and few ‘important’ ties lived outside Rotterdam. This is important because social networks impact activity and travel patterns and spatial awareness, affecting both perceptual and actual action-space (cf. Arentze & Timmermans, Citation2008; Axhausen, Citation2008; Carrasco & Miller, Citation2009; Urry, Citation2002). Respondents partly based their residential and activity choices on their familiarity with spaces and places with which they had become acquainted through trips to friends, relatives, workplaces, etc. (cf. Blaauboer, Citation2011; Feijten, Citation2005; Pred, Citation1981). This in turn affected their meeting opportunities and social ties.

Respondents that did not live in their childhood neighbourhood often based their location decision on impressions and information that were rooted in their past life trajectories. They relied on information derived from their social network or their own experience obtained by travelling to or through spaces. After all, one will not consider travelling or living in a place if one is not even aware of its existence. In Menno’s case, his residential choice is partly rooted in his tie with his wife, her life trajectory (work) and the resulting daily trajectory.

My wife worked somewhere on [nearby street] and during her break she walked by and saw this house was for sale. So: ‘Cool house!’ Took a look. The real estate agent was right across, so she brought the brochure with her.

Menno, 33, native-Dutch man, Liskwartier

The neighbourhood preferences of respondents were influenced by where their social network members lived because they preferred to live proximate to people who were important to them. Segregation literature often points to preferences for co-ethnics in the neighbourhood as a cause for residential segregation (see, for instance, Bolt, Van Kempen, & van Ham, Citation2008), but for the Turkish-Dutch in this sample, the ethnic factor was not so prominent. It was the presence of relatives, rather than the presence of other Turkish-Dutch (cf. Zorlu, Citation2009), that motivated them to stay within their childhood neighbourhood. When the (older) married Turkish-Dutch respondents brought their partner to Rotterdam from Turkey, they often had no family ties elsewhere in the Netherlands. Thus, they had a strong preference for a single neighbourhood.

I have lived here all my [life], here in the neighbourhood. I just lived two-and-a half years in Charlois [other neighbourhood in Rotterdam South]. Because when I got married, I was going to bring my husband from Turkey, so I got a house, I had to take it, but I also had something like: Charlois is also far away for from here [appr. 2.5 km], because I was really used to this place. My whole family, my mother, my sister were here, so I swopped houses with here.

Cahide, 39, Turkish-Dutch woman, Afrikaanderwijk

For younger Turkish-Dutch respondents who, like the native Dutch, met their partners mainly through friends and educational facilities, choices had to be made between living close to one’s own relatives or those of their partner. Although some native Dutch respondents also lived close to their immediate relatives (cf. Blaauboer, Citation2011; Zorlu, Citation2009), for the native Dutch, the presence of friends was more of a pull-factor than family. While education and work made it more difficult for the more skilled native Dutch to remain in their childhood neighbourhood, the deinstitutionalisation of family ties in individualised native Dutch society was also a factor.

Differences in household formation between the two groups had consequences for residential choices. The Turkish-Dutch generally start families upon leaving the parental household, or they remain living with their parents (cf. Bolt, Citation2002). Therefore, they often move directly to relatively large dwellings from their parental house and are also more often reliant on the social rented sector due to financial constraints. Among the native Dutch, like in other modern societies, marriage and having children have become less of a social obligation (see Allan, Citation2001). Native Dutch are more likely to start their housing career as singles in smaller accommodations, or in co-residence with friends and classmates, especially the higher educated (Van Duin, Stoeldraijer, & Garssen, Citation2013). Respondents often found accommodation in the private rented sector at this stage through informal recruitment by friends. On relocation, they would sometimes stay in the neighbourhood. The presence of friends in the neighbourhood could keep them there, and their departure could weaken neighbourhood attachment, like in the case of Harold below. (cf. Conradson and Latham (Citation2010)

But you went back to Rotterdam [after moving away from the region with his mother a as a teenager]?

Yes, many friends lived in Rotterdam. Meanwhile most of them have left again.

Out of the neighbourhood or out of Rotterdam?

Out of the neighbourhood … a very good one, my best friend has moved to [small town appr. 50 km away], so that is [swear word], but all right.

But you’re staying for now?

No, I don’t think so, I don’t have much to keep me here, so … I don’t know where I’ll be going.

Harold, 37, native-Dutch man, Liskwartier

Segregation within the neighbourhood

It can be expected that the population composition of the neighbourhood influences the development of inter-ethnic ties during childhood. Although many childhood friendships do not continue into adulthood (see also Spencer & Pahl, Citation2006), experience with inter-ethnic interaction may help individuals construct inter-ethnic ties later in life, as they are more familiar and at ease with other cultural backgrounds (cf. Wessendorf, Citation2013; Wilson, Citation2014). Children’s potential activity spaces are often limited to the residential neighbourhood (cf. Visser, Citation2014), especially when their school is also located within the neighbourhood. The population composition of neighbourhoods is therefore more relevant for inter-ethnic ties during childhood than in later stages of life. However, opportunities for playing with children of other ethnic backgrounds in Afrikaanderwijk and Liskwartier were limited for several reasons, despite their population diversity.

First, on the street level, which is most relevant in early childhood, there was less residential mixing. Some streets and blocks were dominated by native Dutch, others by ethnic minorities, which has much to do with differences in social status and the distribution of owner-occupied and social rented housing. As explained above, because of differences in social class and employment, owner-occupied houses are dominated by native Dutch, whereas most ethnic minorities live in social rented housing. The aggregated effect of differences in life trajectories between both groups is residential segregation on the street level.

Inter-ethnic meeting opportunities also differed between generations. Forty-two-year-old Lale compared her own childhood to that of her daughter. When Lale was young, there were no other Turkish children for her to play with, so she had little choice but to play with native Dutch children. Over time, the number of ethnic minorities from Turkey and other countries has increased. Her daughter can find ample friends of non-native origin and socialises mainly with other Turkish and Moroccan girls.

It just that it’s more mixed, the schools. Children have more Moroccan and Turkish friends, but in my time it was only Dutch friends … When I came to the Netherlands, I was the only Turkish girl in school.

Lale, 42, Turkish-Dutch woman, Liskwartier

With the growing numbers of ethnic minorities over the past decades, the necessity and opportunity for Turkish children to play with native Dutch children has decreased, whereas native Dutch children growing up in areas of ethnic concentration have less opportunity to play with co-ethnics (see also Matejskova and Leitner (Citation2011, p. 728), who observe similar reduced contact opportunities in a Berlin neighbourhood). This implies a certain threshold level: above a certain number of co-ethnics, sufficiently ‘similar’ others can be found to satisfy the need for friendship, making the discomfort of adapting to others who are very different from oneself unnecessary.

Secondly, schools, which play an important role in constructing ties between parents and between children, are largely segregated along ethnic and class lines. Boterman (Citation2013) states that schools in the Netherlands are more strongly ethnically segregated than neighbourhoods due to free choice of schools. Even native Dutch parents who opt for ethnically diverse neighbourhoods tend to prefer ‘white’ schools for their children. Though fear of discrimination and standing out played a role in the choice of schools, prior life trajectories were also important. Respondents, for instance, sent their children to schools recommended by their social contacts, special schools with a (religious) affiliation that matched their own conviction (see quote below), schools that provided the after-school programme their fulltime jobs required,or schools they had attended themselves.

… it was an Islamic school, that’s why I went all the way from North to West. My dad really wanted that, so eight years I went to West, to school.

Jasmin, 23, Turkish-Dutch woman, Liskwartier

The social norms and routines they developed through life affected their decisions. Thus, the choice of school for one’s child(ren) was rooted in life trajectories and existing ties, shaping opportunities to meet people from other ethnic groups not only for the parents but also for their child(ren). This process generally resulted in respondents’ children being sent to schools with many co-ethnics.Footnote3 However, for some native Dutch respondents who had grown up in Afrikaanderwijk, and who sent their children to the same schools as they themselves had attended, the opposite was the case. These schools had, over time, become dominated by ethnic minorities and thus the respondents and their children came into contact with parents and children of other ethnic groups.

Recruitment for jobs and leisure activities

Respondents were often recruited for jobs through their existing social network, resulting in largely segregated workplaces, though differences in qualifications and discrimination also play a role (see also Dagevos, Citation2006). Nefis (28, Turkish-Dutch woman, Liskwartier) explained how she once found work in a market garden with many other Turkish employees, after being recruited by her mother, who worked there as well. Johan (44-year-old, native Dutch man, Liskwartier) found his current employer with only native Dutch staff after a tip from an ex-colleague. Such informal recruitment practices generally reinforce the ethnic segregation of workplaces because people’s social networks are quite homogeneous.

However, jobs found through informal venues can assist individuals with gaining work experience that helps them when applying for jobs through formal procedures. Camer, (26, Turkish-Dutch man, Afrikaanderwijk) found his last job with a shop in an affluent ‘white’ neighbourhood with all-native Dutch colleagues in another part of the city, after applying through official venues. His work experience in his father’s shop that sold the same type of products helped him get the job. At that new workplace, he met one of his best native Dutch friends. The increased opportunity for meeting native Dutch followed from his prior life trajectory, even when co-ethnics dominated his social environment in earlier times of his life. This shows how opportunities for meeting other ethnic groups are not constant, but vary along with their changes in activity and activity-site.

For social and leisure activities, the same recruitment mechanisms exist. Some leisure activities can also be rooted in social and religious obligations put on individuals by the existing social network. For instance, practically all of the Turkish-Dutch respondents had attended Koran lessons in one of the local mosques. Youth and football clubs were often organised from these mosques. Preferences for certain cultural products were also transferred through parents and friends. Adil (21, Turkish-Dutch man, Afrikaanderwijk), for instance, joined his father and other Turks in a Turkish Folk music band. By comparison, Menno (33, native-Dutch man, Liskwartier) was introduced to Hard Rock music by his father and a friend at his scouting club when he was young and now himself plays in a heavy metal band. He often frequents Heavy Metal concerts, a music scene generally dominated by ‘white’ men. This shows how primary ties affect activity patterns, whereabouts in time–space and thus opportunities to meet people from other ethnic groups. Both Adil and Menno were introduced to music by their fathers and other primary ties, and had joined a band, but in both cases, the style of music to which they were acculturated and the activities that came along with it tended to keep them within social circles that consisted largely of co-ethnics.

Even when respondents participated in similar activities, like swimming, these activities could also be segregated because of cultural preferences. Some Turkish-Dutch women visited the ‘women only’ hours in the swimming-pool, so they could exercise without being subjected to the gaze of male visitors. Not all Turkish women avoid sports in the company of men, but their activity companions often do, as the quote of Bediz below shows. The result is that those who do prefer gender segregation largely determine the site and timing of sports activities, in turn affecting meeting opportunities. Because native Dutch women usually do not attend these ‘women only’ activities, the women of the two groups have little chance of encountering each other, even if they use the same swimming pool, due to different activity timings. This shows that not only are the preferences of the individual relevant in the selection of activities, sites and timing, but so too are those of activity companions (cf. Yücesoy, Citation2006).

‘It was like: “do you want to go swimming together, it’s on Mondays?” and I said: “well that’s fun.”.’

‘Is that especially for women?’

‘Yes, because not everybody wants to go with men and women of course … well for me it doesn’t matter, I just go to sea when we’re in Turkey, so for me it makes no difference.’

Bediz, 38, Turkish-Dutch woman, Afrikaanderwijk

Other cultural and religious rules, such as the ban on alcohol in Islam, kept some Turkish-Dutch respondents (but certainly not all of them) from participating in activities or entering places where alcohol was being served. This meant that when meeting outdoors with friends, they preferred to do so at a mosque or teahouse, rather than a pub. These were places where they were likely to meet co-ethnics, though some emphasised they had also met a few Muslims from other ethnic groups there, including some native Dutch converts. Thus, value differences between the two groups diverted the time–space paths of some, leading to different activity sites or timings between groups, reducing the chances of meeting each other.

Those respondents who mentioned people of other ethnic backgrounds as one of their five most important ties had generally met these people in advanced education or in work situations. The key is that when it comes to education and work, these activities are more obligatory and choice options are limited. The higher the degree of choice, the more likely it is that activity locations are selected that have a homogeneous clientele, either because they know the place through reference or because they host a familiar (or similar) type of people with whom they can identify. Therefore, policy efforts to increase social cohesion in Afrikaanderwijk by creating more meeting places were counter-effective, as the quote by Fadil below shows.

‘It is more anonymous now … I used to know everybody in the street.’

‘That has become less?’

‘Yes, I think people look up their own people more now.’

‘That was less in the past?’

‘In the past there were not so many places where you could come together as a group, so you went to places were others also came.’

Fadil, Turkish man, 39, Afrikaanderwijk

Having a colleague or classmate with a different cultural background could create an opening for being introduced to other social surroundings and ethnic spaces, as Luuk’s quote illustrates:

It was a Moroccan … I don’t know how it’s called, where they smoke the water-pipe. I was there one time. I thought it was nice experience for once. It was a classmate’s, a Moroccan classmate’s, and I was curious what went on in such a café.’

Luuk, 21, native-Dutch man, Liskwartier

This, however, requires a preparedness to integrate one’s personal network and not keep contacts separated (see Hannerz, Citation1980). Although native Dutch individuals may also choose to separate their social circles (see Blokland, Citation2003), protecting the privacy of the home may be part of Turkish culture (cf. Hofstede, Citation2001; Yücesoy, Citation2006), preventing people of Turkish origin from introducing their relatives to ethnic-other friends and colleagues.

Social orientation

Not only are choices in educational, work and residential careers influenced by the existing social network, so too are choices in the type of social ties people choose to build and maintain (e.g. friendships, kinship). Existing ties introduce individuals to activities, places and people. They also help to transfer ideas and beliefs, and social norms, including social orientations, i.e. the type of people (e.g. family, neighbours, colleagues) on which individuals focus for socialisation.

This social orientation differed to some extent between the Turkish-Dutch and the native Dutch respondents. We have already discussed how the focus on family ties affected the residential choices of the Turkish-Dutch respondents. Though we did not see numerical differences in relatives being labelled as important, the Turkish-Dutch respondents had more frequent contact with their immediate relatives. The Turkish-Dutch were also more focused on neighbourly ties. Turkish-Dutch women in particular often mentioned direct neighbours among their five most important social network members. These neighbours were all (except for one) other Turkish-Dutch women. Bediz, a 38-year-old Turkish-Dutch woman from Afrikaanderwijk, said there was a Turkish expression ‘First buy neighbours, then house’ because one does not want neighbours with which one cannot get along. Although some other respondents also mentioned neighbours or other people in the neighbourhood as important, the interviews revealed these neighbours were primarily relatives, colleagues, classmates or pre-existing friends, and often did not live in adjacent houses. Native Dutch respondents stated they preferred to keep relations with neighbours more superficial to protect their privacy (cf. Müller & Smets,Citation2009). They rarely mentioned direct neighbours as their primary ties.

The native Dutch respondents listed more work relations as their most important ties. This may have to do with their employment status, as they were more often full-time employed than the Turkish-Dutch respondents. People who work full-time have little time for other activities and may restrict their social contacts to immediate relatives and colleagues. Some (native Dutch) respondents also met strangers from faraway places online, further dispersing their social network in a geographical sense. The Turkish-Dutch respondents tended to avoid encounters with strangers online, consistent with the stronger tendency towards ‘risk-avoidance’ in Turkish culture (see Hofstede, Citation2001; Yücesoy, Citation2006).

Prioritising existing ties

Contrary to many population-mixing policies (see, for instance, Atkinson & Kintrea, Citation2000; Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005), people do not move through urban areas with the intention of meeting as many people as possible and trying to befriend all the strangers they encounter. Respondents would sometimes observe strangers with curiosity, but even if they wanted more contact with other groups, day-to-day business kept them pre-occupied and strange others in the vicinity would sometimes be labelled as ‘obstacles’ who stood in their way. There is a limit to the number of ties one can maintain. Respondents explained their disinterest in people they encountered as ‘I already have friends’, as the quote by Alida below illustrates:

‘I keep my circle of friends the way it is. I don’t need to add any friends. I don’t need to lose some, but I also don’t need any friends extra[…]They’re people who’ve known me before my bad times, who’ve seen me fall and crawl up again … there I don’t have to […] I don’t like keeping up appearances as if I am enjoying myself terrifically.’

Alida, 39, native-Dutch woman, Afrikaanderwijk

Respondents stressed having trouble maintaining the relationships they already had, especially once they were in a life phase where they had jobs and children and their work and parent obligations consumed much of their time, like in the case of Duman:

‘Yeah, working people, actually having a very busy life and less social contact with people around them[…], if I go 20 years back, I was at school and yes you were free as a bird and you can go everywhere: acquaintances, family, friends, but now you have a family, three children,. Yes you’re tied to something, but it is very different from youth times so to say.

Do you still have friends from those days?

I have friends, but the contacts are getting less and less.

Duman, 34, Turkish-Dutch man, Liskwartier

As existing ties have already proven themselves useful and much time and social capital (such as providing consolation in times of grief) has been invested in them, these ties receive priority over new ones. Prioritising the maintenance of certain pre-existing ties, like family or neighbours, can also be culturally influenced by society (Hofstede, Citation2001). When gathering at activity sites like schools, socialising with existing acquaintances receives priority over interaction with strangers, effectively leading to grouping along ethnic lines, as Fadil highlighted:

‘Is there any contact between the Turkish and Moroccan parents [at child’s school]?’

‘No, not really, they come there because their children go to school there and usually there is not much contact with Moroccan and Turkish … its more Turkish groups together, Moroccan group together, Pakistani group together, so not really mixing at great scale, you have people that you know, but that is only a small number.’

‘And how do you know them?’

‘Because they go to the Turkish mosque, and we go to their mosque, only a few actually.’

Fadil, 39, Turkish-Dutch man, Afrikaanderwijk

The repeated encounter with the same people at various activity sites reduces strangeness (see Jackson, Harris, & Valentine, Citation2017), and creates a sense of positive public familiarity, shared identity (see Blokland, Citation2003; Jacobs, Citation1961) and sense of trust (through lack of negative experiences). Furthermore, a certain degree of inattentiveness to strangers in public spaces is often the prescribed code of civil behaviour (see Goffman, Citation1963; Noble, Citation2013). It may be considered intrusive to mingle in the conversations of strangers while ignoring one’s own acquaintances may be considered rude. The threshold to engage in conversation may be lower in situations of repeated encounter and identification as ‘belonging to the same group elsewhere’.

The chance of repeated encounter is small when activities are located farther away from home and the population at locations is drawn from a wider area. While some respondents had many activities in the neighbourhood, some others only experienced their neighbourhood while walking a few steps from their front door to their bicycle or car. For example, Johan (44, native Dutch man) came to live in Liskwartier after moving in with his Surinamese wife, who had already bought a house there when he met her at the birthday party of mutual friends. His most important contacts, his mother and brother, live in the east of the city. His job is located in a town southeast of Rotterdam, and every morning he leaves his house before dawn to travel there. After work, he goes to a fitness centre located along the highway route introduced to him by his wife. When showing him photos of his neighbourhood to extract information on which amenities he might use, he did not recognise anything. With his Turkish-Dutch neighbour, the only contact is a quick nod or wave at the front door on encounter, but he does not know how many children live there or their names.

Whether one is open to contact with strangers at activity sites also depends on the social setting in combination with individual motives for contact. These motives depend on life stage and preoccupations. Respondents were, for example, less open to contact when grocery shopping than during leisure and work activities. Waiting for a child to finish his or her swimming lessons or football practice were circumstances where respondents started conversing with strangers to kill time. Expecting to see somebody more often or for a long time on end (for instance, at the leisure-club or at work) made investing in the relationship more attractive. This depends on (future) life trajectories and expectations of repeated encounter.

Under specific circumstances, people may deliberately visit certain spaces or join clubs to meet new people because their existing social network is disrupted. These disruptions may occur through life events like changing jobs and moving to a new city (like in the case of Ilse below), disagreements with friends or because they are looking for a life partner.

‘When I just moved here, I didn’t know anybody of course. So I did consider like “shall I join some sport?” But no, and then I thought I might take some course …’

Ilse, 42, native-Dutch woman, Liskwartier

Often, the existing social network members will help fill the gap in the social network of the individual by introducing them to other members of their own social network, which will often consist of co-ethnics. As a consequence, the ethnically homogeneous personal social network, as well as most likely the type of connection, is reinforced. Turkish Dutch are more likely to be introduced to relatives of neighbours and other given ties, whereas the native Dutch introduce each other to more chosen ties like colleagues and friends. Because the native Dutch often moved over long distances, maintaining existing ties was more often constrained. The social networks of the native Dutch therefore seemed to be more ‘fluid’ than those of the Turkish Dutch, as friendship is more easily dissolved than kinship and because of the geographical volatility of their social network members.

Conclusions and discussion

In the past decade or so, there has been much debate on residential segregation and mixing policies and their role in impeding or enhancing inter-ethnic contacts and other neighbourhood effects. This is traditionally approached from the geographical and sociological standpoint of meeting opportunities created by population compositions and physical proximity (the supply-side; see, for instance, Bolt, Phillips, & van Kempen, Citation2010; Galster, Citation2007; Mollenhorst, Citation2009; Van Ham, Manley, Bailey, Simpson, & Maclennan, Citation2012 eds.). In contrast, social psychologists point towards the preference for homophilious interaction, which stands in the way of inter-group contacts even when the opportunity is there (the demand-side; cf. Marsden, Citation1988; McPherson et al., Citation2001; Mollenhorst, Citation2009). Neither standpoint captures the path-dependent social construction behind these supplies and demands. The current debate tends to ignore the fact that individuals do not start their lives free from social attachments and the influence of these social ties. Without a thorough understanding of these processes, policies for social mixing, often on a residential level (see, for instance, Dekker & Bolt, Citation2005; Ireland, Citation2008), may fail in promoting benevolent inter-ethnic contacts. For our analysis of the social networks of native and Turkish Dutch individuals in Rotterdam, we have used the approaches and methodology from time geography to understand the formation of segregated social networks. We think this time-geographic approach better explains the process of segregation and unites the two traditional approaches of meeting opportunities versus preferences for homophilious interaction.

Our analysis shows that neighbourhood population composition plays only a limited role in the development of residents’ personal social networks and depends on their daily activity paths and life trajectories. The homogeneity in social networks was hardly a conscious choice, as most respondents were open to people of other origins (cf. Wessendorf, Citation2013). However, social networks are strongly path dependent. Individuals are not as footloose in their social ties as the sociologies of modern societies (e.g. Bauman, Citation2005; Simmel in Spykman, Citation2009, Tönnies, Citation1887/2005) suggest. Building social relationships starts at birth, as the members of the parental household are the first ties formed in life (cf. Elias, Citation1991). Through parents and siblings, one is introduced to other people, activities and places, and from there, the path of introduction and familiarity continues. This generally results in activities and relations dominated by co-ethnics. In their social contacts, they are captured by their social networks, rather than being free floating and cross-cutting between social circles. Thus, they tend to move within a chain of homogeneous social circles. The aggregated result of these individual life and daily trajectories is a largely segregated society, on various levels. Even when the group of co-ethnics is small, shared social settings like mosques and schools, in combination with shared cultural preferences and social orientations, lead to homophilious interactions and ethnically homogeneous social networks. A great variety of meeting places further facilitates segregation by providing each group with its own spaces. Consequently, groups hardly meet each other in the same setting. Ethnic others are predominantly encountered in public space, where contact is superficial and the rules of civil inattention impede interactions between strangers. Though we have not discussed practices of discrimination, intimidation and other ‘daily racisms’ (cf. Pain 2001), such superficial encounters may reinforce prejudice (both positive and negative) and possibly intolerance (see Amir, Citation1969; Puwar Citation2004; Valentine, Citation2008; Van Oord, Citation2008). This may threaten social cohesion in diversifying urban societies (cf. Tasan-Kok et al., Citation2014; Vertovec, Citation2007).

This does not mean that base locations (like the residential neighbourhood, school and work, as the most frequently visited activity places)are irrelevant for constructing social circles. Their selection is the combined result of prior life trajectories and resulting contacts, information, attitudes and roles. As such, similarities between people who attract each other, like religion, culture, and taste in music, are largely socially constructed through interaction. Culturally taught attitudes, tastes and activities again lead to differences in activity patterns and careers between ethnic groups, separating their trajectories in time-space and preventing opportunities for meeting. Internalised cultural social norms can involve the prioritisation of certain types of ties, like family, over others. Generally speaking, existing social network members receive priority over new ones.

In addition, for many people, the neighbourhood is not the context in which they build their social relationships. Though neighbourhood networks can be found in both neighbourhoods in this study, they were largely segregated, co-existing, ethnically homogeneous networks, and there were several (native Dutch) respondents who did not have social ties in their neighbourhood at all and did not seek them. They deliberately kept contact with neighbours superficial to protect their privacy. Focussing on neighbourhoods as the main setting for ethnic integration policies is not very suitable when the culture of the majority population does not favour strong ties with neighbours but focuses more on professional and leisure-activity ties. The work of Piekut and Valentine (Citation2017) shows that the main context where individuals meet with ethnic-others differs between countries. Whereas the UK work and study were the most relevant contexts, as in the present study in the Netherlands, but in Poland public parks were more relevant in their study. Policy-makers need to take in account these cultural differences.

Ethnically mixed work and school situations may be important spaces where more durable inter-ethnic ties develop because trying to get along is more obligatory in these contexts. As argued by Allport (Citation1954/1979), situations of shared goals, cooperation and equal status in these contexts may help to reduce negative prejudice and shape friendly inter-ethnic interactions, though the necessity and sufficiency of such conditions are contested (see, for instance, Bekerman, Citation2007; Pettigrew & Tropp, Citation2006; Valentine, Citation2008).The presence of these conditions may also depend on the local work culture. Mixed settings in schools and workplaces can develop through the gradual influx of ethnic minorities in schools and workplaces, as they try to pursue their socio-economic goals. A sole inter-ethnic friendship constructed through such venues can provide an opening to more inter-ethnic ties if the ethnic-other friend introduces one to the social spaces of his or her ethnic group. This requires that personality and culture motivate individuals to blend the contacts within the personal social network. Though policy can do little to change this protection of privacy by individuals, policy can facilitate the creation of mixed work and school settings, as well as introduce people at a young age to (leisure) activities that are not prevalent within their social networks. Ethnic minority children in the Netherlands might for instance be encouraged to participate in typical ‘Dutch’ sports, like hockey. Gijsberts and Dagevos (Citation2007a) argue that programmes that focus merely on inter-group meeting without any shared interests for participants are likely to be unsuccessful. However, they add that more evaluation studies are needed to draw any definite conclusions on the most successful methods.

The present study comprises two neighbourhoods in Rotterdam. It is possible that in other areas, for instance less urban areas with a much smaller proportion of ethnic minorities, residents show very different patterns. Replication of this research in other contexts is therefore recommended. Future research should also pay more attention to the life path aspects of social network formation. This requires more longitudinal and quantitative studies that look at people’s daily activity patterns, activity locations and social orientations, rather than their residential environment. More research in different contact settings, both physical and virtual, while also paying attention to emotional aspects and self-selection processes, is required to attain a better understanding of the settings that are beneficial for inter-ethnic contacts and those that are not.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our respondents for participating and thank our anonymous reviewers, Brenda Madrazo, Maggi Leung and Mary Gilmartin for their useful comments.

Notes

1. We use the label ‘Turkish-Dutch’ and not ‘Turkish’ to emphasise the transnational and hybrid character of ethnicity.

2. Social network members in Turkey or other European countries were not listed as important.

3. In secondary and tertiary education, the segregation is aggravated by the separation of learning levels because ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the higher school levels and in higher education (CBS Statline).

References

- Allan, G. (2001). Personal relationships in late modernity. Personal Relationships, 8, 325–339.10.1111/pere.2001.8.issue-3

- Allan, G. (2008). Flexibility, friendship, and family. Personal Relationships, 15, 1–16.10.1111/pere.2008.15.issue-1

- Allport, G. W. (1954/1979). The nature of prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley, 25th Anniversary edition.

- Amin, A. (2002). Ethnicity and the multicultural city: Living with diversity. Environment and Planning A, 34, 959–980.10.1068/a3537

- Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71, 319–342.10.1037/h0027352

- Arentze, T., & Timmermans, H. (2008). Social networks, social interactions, and activity-travel behavior: A framework for microsimulation. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 35, 1012–1027.10.1068/b3319t

- Atkinson, R., & Kintrea, K. (2000). Owner-occupation, social mix and neighbourhood impacts. Policy & Politics, 28, 93–108.10.1332/0305573002500857

- Axhausen, K. W. (2008). social networks, mobility biographies, and travel: Survey challenges. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 35, 981–996.10.1068/b3316t

- Bauman, Z. (2005). Liquid life. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bekerman, Z. (2007). Rethinking intergroup encounters: rescuing praxisfrom theory, activity from education, and peace/co-existence from identity and culture. Journal of Peace Education, 4, 21–37.10.1080/17400200601171198

- Blaauboer, M. (2011). The impact of childhood experiences and family members outside the household on residential environment choices. Urban Studies, 48, 1635–1650.10.1177/0042098010377473

- Blau, P. M., & Schwartz, J. E. (1984). Crosscutting social circles: Testing a macrostructural theory of intergroup relations. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Blokland, T. (2003). Urban bonds: Social relationships an inner city neighbourhood (L. K. Mitzman, Trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bolt, G. S. (2002). Turkish and Moroccan couples and their first steps on the Dutch housing market: Co-residence or independence? Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 17, 269–292.10.1023/A:1020297016480

- Bolt, G. S., Van Kempen, R., & van Ham, M. (2008). Minority ethnic groups in the dutch housing market: Spatial segregation. Relocation Dynamics and Housing Policy, Urban Studies, 45, 1359–1384.

- Bolt, G., Phillips, D., & van Kempen, R. (2010). Housing policy, (De)segregation and social mixing. An International Perspective, 25, 129–135.

- Boterman, W. R. (2013). Dealing with diversity: Middle-class family households and the issue of ‘black’ and ‘white’ schools in Amsterdam. Urban Studies, 50, 1130–1147.10.1177/0042098012461673

- Carrasco, J., & Miller, E. J. (2009). The social dimension in action: A multi-level, personal networks model of social activity frequency between individuals. Transportation Research Part A, 43, 90–104.

- CBS Statline. (2011). Online database Netherlands statistics. Retrieved November 9, 2012; July 16, 2014, from http://statline.cbs.nl/statweb

- Chorus, J. (2010). Afri: Leven in een Migrantenwijk. Amsterdam: Olympus.

- Conradson, D., & Latham, A. (2010). Friendship, networks and transnationality in a world city: Antipodean transmigrants in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31, 287–305.

- Dagevos, J. (2006). Hoge (jeugd)werkloosheid onder etnische minderheden [High (youth) unemployment among ethnic minorities]. The Hague: SCP.

- Dekker, K., & Bolt, G. S. (2005). Social cohesion in post-war estates in the Netherlands: Differences between socio-economic and ethnic groups. Urban Studies, 42, 2447–2470.10.1080/00420980500380360

- Dijst, M. J. (1999). Two-earner families and their action-spaces: A case study of two Dutch communities. GeoJournal, 48, 195–206.10.1023/A:1007031809319

- Dijst, M. J. (2006). Oratie: Stilstaan bij beweging: Over veranderende relaties tussen steden en mobiliteit. Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht.

- Dijst, M. J. (2009). ICT and social networks: Towards a situational perspective on the interaction between corporeal and connected presence. In R. Kitamura, T. Yoshii, & T. Yamamoto (Eds.), The expanding sphere of travel behaviour research (pp. 45–75). Bingley: Emerald Publishing.

- Dixon, J. C. (2006). The ties that bind and those that don’t: Toward reconciling group threat and contact theories of prejudice. Social Forces, 84, 2179–2204.10.1353/sof.2006.0085

- Doucet, B. (2010). Rich cities with poor people: Waterfront regeneration in the Netherlands and Scotland. Utrecht: Netherlands Geographical Studies.

- Drever, Anita (2004). Separate spaces, separate outcomes? Neighbourhood Impacts on Minorities in Germany, Urban Studies, 41, 1423–1439.

- Elias, N. (1991). The society of individuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Duyvendak, J. W. (2011). The politics of home: Belonging and Nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230305076

- Dyck, I., & Kearns, R. A. (2006). Structuration theory: Agency, structure and everyday life. In S. Aitken & G. Valentine (eds.), Approaches to human geography (pp. 86–97). London: Sage.

- Feijten, P. (2005). Life events and the housing career: A retrospective analysis of timed effects. Delft: Eburon.

- Galster, G. (2007). Neighbourhood social mix as a goal of housing policy: A theoretical analysis. European Journal of Housing Policy, 7, 19–43.10.1080/14616710601132526

- Giddens, A. (1984). Time, space & regionalization. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration (pp. 110–119). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gijsberts, M., & Dagevos, J.. (2007a). Interventies voor Integratie: Het tegengaan van etnische concentratie en bevorderen van interetnisch contact [Interventions for integration: Countering ethnic concentration and promoting inter-ethnic contact]. The Hague: SCP.

- Gijsberts, M., & Dagevos, J. (2007b). The socio-cultural integration of ethnic minorities in the Netherlands: Identifying neighbourhood effects on multiple integration outcomes. Housing Studies, 22, 805–831.10.1080/02673030701474768

- Goffman, I. (1963). Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gatherings. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.10.1086/225469

- Hägerstrand, T. (1967). Innovation diffusion as a spatial process. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hägerstrand, T. (1970). What about the people in regional science? Presidential address. Ninth European congress of the regional science association. Papers of the Regional Science Association, 24, 6–21.10.1007/BF01936872

- Hägerstrand, T. (1975). Space, time and human condition. In A. Karlquist, et al. (Eds.), Dynamic allocation of urban space (pp. 3–14). Wermeads: Saxon House.

- Hamm, J. V. (2000). Do birds of a feather flock together? The variable bases for African American, Asian American, and European American adolescents’ selection of similar friends, developmental psychology, 36, 209–219.

- Hannerz, U. (1980). Exploring the city: Towards an urban anthropology. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Heringa, A. M., Bolt, G. S., Dijst, M. J., & van Kempen, R. (2014). Individual activity patterns and the meaning of residential environments for inter-ethnic contact. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 105, 64–78.10.1111/tesg.2014.105.issue-1

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations ( 2nd ed.). Thousend Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Huijnk, W., & Dagevos, J. (2012). Dichter bij elkaar? De sociaal-culturele positie van niet-westerse migranten in Nederland [Closer together? The social-cultural position of non-western migrants in the Netherlands]. The Hague: SCP.

- Ireland, P. (2008). Comparing responses to ethnic segregation in urban Europe. Urban Studies, 45, 1333–1358.10.1177/0042098008090677

- Jackson, L., Harris, C., & Valentine, G. (2017). Rethinking concepts of the strange and the stranger. Social & Cultural Geography, 18(1), 1–15.

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Kwan, M. P. (2012). The uncertain geographic context problem. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102, 958–968.10.1080/00045608.2012.687349

- Lanzendorf, M. (2003, August 1–15). Mobility biographies: A new perspective for understanding travel behaviour. Conference Paper 10th international conference of Travel Behaviour Research, Lucerne.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marsden, P. V. (1988). Homogeneity in confiding relations. Social Networks, 10, 57–76.10.1016/0378-8733(88)90010-X

- Maslow, A. H. (1956). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Matejskova, T., & Leitner, H. (2011). Urban encounters with difference: The contact hypothesis and immigrant integration projects in eastern Berlin. Social & Cultural Geography, 12, 717–741.10.1080/14649365.2011.610234

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444.10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Mollenhorst, G. (2009). Networks in contexts: How meeting-opportunities affect personal relationships. Enschede: Ipskamp Drukkers.

- Mulder, C. H. (1993). Migration dynamics: A life course approach. Amsterdam: Pdod.

- Müller, T., & Smets, P. (2009). Welcome to the neighbourhood: Social contacts between Iraqis and natives in Arnhem. Local Environment, 14, 403–415.10.1080/13549830902903682

- Musterd, S., & Ostendorf, W. (2009). Residential segregation and integration in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35, 1515–1532.10.1080/13691830903125950

- Noble, G. (2013). Cosmopolitan habits: The capacities and habits of intercultural conviviality. Body & Society, 19, 162–185.10.1177/1357034X12474477

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 65–85.10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 751–783.10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

- Phillips, D. (2010). Minority ethnic segregation, Integration and citizenship: A European Perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36, 209–225.

- Piekut, A., & Valentine, G. (2017). Spaces of encounter and attitudes towards difference: A comparativestudy of two European cities. Social Science Research, 62, 175–188.10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.08.005

- Pred, A. (1981). Social reproduction and the time-geography of everyday life. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 63, 5–22.10.2307/490994

- Puwar, N. (2004). Space Invaders: Race. Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Oxford & New York: Bergpublishers.

- Sam, D. L., & Berry, J. W. (2010). Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 472–481.10.1177/1745691610373075

- Schnell, I., & Harpaz, M. (2005). A model of a heterogeneous neighborhood. GeoJournal, 64, 105–115.10.1007/s10708-005-4093-0

- Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A, 38, 207–226.10.1068/a37268

- Smets, P. (2005). Living apart or together? Multiculturalism at a neighbourhood level, Community Development Journal, 41, 293–306.

- Smith, T. W. (2002). Measuring inter-racial friendships. Social Science Research, 31, 576–593.10.1016/S0049-089X(02)00015-7

- Spencer, L., & Pahl, R. (2006). Rethinking friendship: Hidden solidarities today. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Spykman, N. J. (2009). The social theory of Georg Simmel. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Storms, O., & Bartels, E. (2008). ‘De keuze van een huwelijkspartner’: Een studie naar partnerkeuze onder groepen Amsterdammers. Amsterdam: Free University of Amsterdam.

- Tasan-Kok, T., van Kempen, R., Raco, M., & Bolt, G. (2014). Towards hyper-diversified european cities: A critical literature review. Found online [quoted October 8, 2014]. Retrieved from http://www.urbandivercities.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/20140121_Towards_HyperDiversified_European_Cities.pdf

- Tönnies, F. (1887/2005). Gemeinschaft Und Gesellschaft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Urry, J. (2002). Mobility & proximity. Sociology, 36, 255–274.10.1177/0038038502036002002

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32, 323–337.10.1177/0309133308089372

- Van Duin, C., Stoeldraijer, L., & Garssen, J. (2013). Bevolkingsstrends 2013 Huishoudensprognose 2013–2060. The Hague: Netherlands Statistics.

- Van Eijk, G. (2010). Unequal networks. Spatial segregation, relationships and inequality in the city. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Van Ham, M., Manley, D., Bailey, N., Simpson, L., & Maclennan, D. (2012). Neighbourhood effects research: New perspectives. Dordrecht: Springer Science.10.1007/978-94-007-2309-2