Abstract

Marked by high levels of diversity and gentrification, changing demographics in east London highlight the need for new analytical tools to examine how formerly familiar spaces must now be re-negotiated. Conceptual frameworks of habit and affect have informed the contemporary analysis of how encounters with difference unfold within transforming cityscapes. However, findings from a participatory research project with young people suggest a more reflexive management of classed and racialised encounters is occurring as accumulated cultural knowledge is tested and revised from which new practices emerge. Attention to processes of reflexivity highlighted the capacity of young people to consciously weigh options and choose a range of strategies under conditions of ‘breach’, including: degrees of acceptance of change; re-working space use through avoidance and adapting everyday practices such as dress and food; as well as developing attributes that enable engagement such as empathy. Feelings of judgement appeared as a dominant driver of reflexivity, while disposition and place contextualised and modified responses. Yet, while the possibilities for subjective re-evaluation and adaptation are apparent, the study raises questions of inequality in the expectation that young people are being asked to adapt to new cultural norms not of their making.

Résumé

Marquée par une proportion élevée de diversité et de gentrification, l’évolution de la démographie à l’est de Londres fait ressortir le besoin de nouveaux outils analytiques pour examiner comment les espaces qui étaient familiers dans le passé doivent maintenant être renégociés. Les cadres conceptuels de l’habitude et de l’affect ont servi à l’analyse contemporaine de la manière dont les rencontres avec la différence se déroulent au sein de paysages urbains en transformation. Pourtant, les résultats d’un projet de recherche participative avec des jeunes suggèrent qu’il existe actuellement une gestion plus réflexive des rencontres de classes et de races au fur et à mesure qu’une connaissance culturelle accumulée est testée et révisée et à partir de laquelle émergent de nouvelles pratiques. L’attention accordée au processus de réflexivité a mis en évidence la capacité des jeunes à peser consciemment les options et à choisir une variété de stratégies dans des conditions de « rupture » telles que : le niveau d’acceptation de changement, la réutilisation de l’espace au moyen d’évitement et l’adaptation aux pratiques quotidiennes comme l’habillement et la nourriture ainsi que le développement d’attributs qui permettent l’implication comme l’empathie. Le sentiment de jugement est apparu comme le moteur principal de la réflexivité, tandis que la disposition et le lieu contextualisaient et modifiaient les réponses. Pourtant, alors que les possibilités de réévaluation subjective et d’adaptation sont apparentes, les travaux de recherche soulèvent des questions d’inégalité de par le fait que l’on attend des jeunes qu’ils s’adaptent à de nouvelles normes culturelles indépendantes de leur volonté.

Resumen

Marcada por los altos niveles de diversidad y aburguesamiento, la demografía cambiante en el este de Londres destaca la necesidad de nuevas herramientas analíticas para examinar cómo antiguamente los espacios familiares deben ahora ser renegociados. Marcos conceptuales de hábito y afecto han informado al análisis contemporáneo de cómo los encuentros con la diferencia se desarrollan dentro de paisajes urbanos en transformación. Sin embargo, los resultados de un proyecto de investigación participativa con jóvenes sugieren que una gestión más reflexiva de los encuentros clasificados y de carácter racial está ocurriendo a medida que se prueba y revisa al conocimiento cultural acumulado y del cual surgen nuevas prácticas. La atención a los procesos de reflexividad puso de relieve la capacidad de los jóvenes para sopesar conscientemente las opciones y elegir una gama de estrategias en condiciones de ‘incumplimiento’, incluyendo: grados de aceptación de cambio; la revisión del uso del espacio a través de la abstinencia y la adaptación de las prácticas cotidianas como vestimenta y comida; así como también el desarrollo de atributos que permitan el compromiso, tales como la empatía. Sentimientos juzgadores aparecieron como impulsores dominantes de la reflexividad, mientras que la disposición y el lugar contextualizaron y modificaron las respuestas. Sin embargo, si bien las posibilidades de reevaluación subjetiva y adaptación son evidentes, el estudio plantea cuestiones de desigualdad en la expectativa de que a los jóvenes se les pide que se adapten a nuevas normas culturales que no han sido creadas por ellos mismos.

Palabras clave:

Introduction

At the borders within hyper-diverse cities differences must be navigated as residents encounter each others’ entangled cultural spaces of divergent meaning and practice. This ‘thrown-togetherness’ (Massey, Citation2005) is marked by the labour of negotiation inflected by inequalities embedded in everyday practices and institutions (Awan, Citation2012; Harris, Citation2010; Landau & Freemantle, Citation2010; Muir & Wetherell, Citation2010; Noble, Citation2013; Watson, Citation2006). Debates on how urban encounters unfold under these conditions have been informed by theories of habit (e.g. Noble, Citation2013, Citation2011) and affective reciprocity (e.g. Amin, Citation2012). However, while these are useful frameworks, this paper calls for greater attention to the processes of decision-making inherent in the development and deployment of strategies and practices utilised to manage encounters with difference. This agency implies reflexivity, taking on board Archer’s (Citation2010) account of ‘internal conversations’ that enable the evaluation of actions, testing and revising accumulated cultural knowledge from which new practices emerge, and demonstrating how the ‘potential of conviviality’ might be realised ( Wilson, Citation2016, p. 10).

A focus on reflexivity is particularly salient when working with young people who must operate within adult frameworks and the dominant discourse of commercialised spaces that mark ‘neo-liberal’, ‘creative’ cities. Young people in particular can be perceived as being ‘out of sync’ (Butcher, Citation2011), their presence contributing to an experience of the urban as disorderly and insecure (Harris, Citation2010; Wallace, Citation2014; Wilson & Grammenos, Citation2005). They must negotiate from an inherently unequal position within stratified encounters that include classed and racialised barriers (Clayton, Citation2012). Yet, it is the position of this paper that young people are not passive in these encounters but rather managing positions of difference through assessing and creating new frames of reference within their capacity and the limitations set by others. Through consciously weighing options and deploying a range of adaptive strategies, everyday practices are reworked from which new structures of interpretation can be assembled. The affective is taken into account in this analysis, with the following narratives highlighting how processes of reflexivity can be instigated by the judgements of others that challenge existing cultural knowledge, generating discomfort in the process.

In addition, the following analysis highlights the significance of place as an assemblage of encounters with both the human and built environment. In the context of Hackney, a gentrifying east London borough, newly arrived middle class and creative professionals with greater socio-economic resources are converting space into their own likeness. As a result, existing residents, such as the young people in this study, have become marginalised in neighbourhoods that are increasingly unfamiliar, both in terms of built environment and encounters with classed and racialised others. This spatial breach has created a context from which reflexive re-workings of self and space are made. The impact of disposition is also evident, such as the willingness to encounter others as well as the ability to do so, supporting claims by proponents of hyper-diversity that it is not only socio-economic and ethnic markers that influence the outcome of interactions, but also lifestyles, attitudes and activities (Tasan-Kok, van Kempen, Raco, & Bolt, Citation2014).

The following section will elaborate on these arguments for a reflexive approach to understanding the outcomes of young people’s encounters with difference, illustrated by findings from the Creating Hackney as Home project (www.hackneyashome.co.uk). Utilising diaries kept by peer researchers, and the documentation of their experience participating in the project, reflexivity is evidenced in their acceptance of change at times, their material adaptations and re-working of space, as well as developing attributes that facilitate engagement such as empathy.

Reflexivity and the breaches of encounter

Marked by high levels of urban redevelopment, mobility, diversity and social inequalities, formerly familiar spaces in east London must now be re-negotiated as cultural frameworks shift along with the built environment (Davison, Dovey, & Woodcock, Citation2012; Watt, Citation2013; Willes, Citation2012). In densely populated neighbourhoods, the frameworks of space use are transgressed via practices of racial and class privilege embodied in the occupation of space under conditions of gentrification (Butler, Hamnett, & Ramsden, Citation2013; Drew, Citation2011; Garbin & Millington, Citation2012; Jackson & Benson, Citation2014; Wilson & Grammenos, Citation2005). The experience of difference is marked by everyday grievances often centred on the breaching of expected codes of conduct. In addition, ‘home’ spaces of comfort and familiarity are removed in processes of demolition and displacement (Butcher & Dickens, Citation2016).The outcome of encounter under these conditions has been widely documented, debated and variously described as agonistic, if not antagonistic (Britton, Citation2011; Butler, Citation2003; Harris, Citation2010; Permezel & Duffy, Citation2007; Vertovec, Citation2015; Vieten & Valentine, Citation2015; Watson, Citation2006), marked by the micro-politics of aggression and resentment (Bacqué, Charmes, & Vermeersch, Citation2014; Bloch & Dreher, Citation2009; Crozier & Davies, Citation2008; Drew, Citation2011; Tissot, Citation2014), as well as tolerance, conviviality and sharing (Neal, Vincent, & Iqbal, Citation2016; Wessendorf, Citation2014; Wise, Citation2005).

While this body of work has provided useful descriptions of contact within changing urban environments, the analysis of how encounter unfolds, that is, the processes involved in determining its eventual outcome, requires further consideration. Debates have coalesced around theories of ‘habit’ and ‘affect’, that is ‘the involuntary reflexes of urban negotiation’ between strangers (Noble, Citation2013, p. 172; see also Amin, Citation2012; Wilson, Citation2011). Under these conditions protagonists relate to each other in ways that are ‘more-than-social’(Kraftl, Citation2013, p. 20), with affective atmospheres influencing the orientation of bodies and the outcomes of contact with both the human and non-human (e.g. Amin, Citation2008; Anderson, Citation2009; Dirksmeier & Helbrecht, Citation2015). Through feelings of discomfort in particular, affective responses to difference impel a withdrawing from the strange or driving towards the comfort of the familiar (Ahmed, Citation2004; Conradson & Latham, Citation2007). The outcome of this contact is intertwined with power and privilege, and inflected by feelings of threat, competition, vulnerability, resentment and guilt (e.g. Anthias, Citation2001; Drew, Citation2011; Gilligan, Shannon, & Curry, Citation2007; Karner & Parker, Citation2011; Pagani, Robustelli, & Martinelli, Citation2011; Schuermans, Citation2017; Smollan, Citation2006).These responses are no less evident in young people encountering difference, managing positions of inequality and experiencing conditions of change (Nayak, Citation2010; Simonsen & Koefoed, Citation2015; Visser, Bolt, & van Kempen, Citation2015).

However, these arguments can present the experience of encounter as fleeting, passive and primarily neurological. They can neglect distinct histories (Harris, Jackson, Piekut, & Valentine, Citation2017), and sustained relationships with place and others that shape accumulated cultural knowledge and subsequent outcomes of encounter (Bennett & Crawley-Jackson, Citation2017; Neal et al., Citation2016; Wilson, Citation2016). As Valentine and Sadgrove (Citation2014, p. 1979) have argued, affective approaches have at times lost sight

of the significance of the subject: of the reflective judgements of ‘others’ made by individuals; of our ability to make decisions around the control of our feelings and identifications; and of the significance of personal pasts and collective histories in shaping the ways we perceive and react to encounters.

Therefore, I make the case for renewed attention to the capacity for reflexivity, rather than reflex, within processes of encounter; reemphasising the affective in a relational, rather than neurological, capacity. To take Archer’s (Citation2010, p. 2) definition, reflexivity entails a form of self-monitoring, a ‘“bending back” of some thought upon the self’, as subject monitors object which then impacts on the subject. Archer notes this differs from reflective thoughts that entail the subject reflecting only on the object, such as the appropriateness of a particular greeting when meeting a stranger. Reflexivity implies that responses to an entanglement of different bodies can include not only the habitual, but also contain the possibility of new practices, new relationships with people and place, new cultural frames of reference generated through deliberation on future actions and, I would add, a projection of the self into the future. This latter point appears particularly salient for young people transitioning through the life course and developing their own aspirations (Brown, Citation2011).

Archer (Citation2010) argues that processes of reflexivity are driven by breaches of extant norms. First, where existing repertoires of action and belief are no longer relevant nor providing a secure orientation for a predictable future, for example, within the speed of change and new forms of difference produced in processes of gentrification. A second form of breach stems from a disposition of curiosity, what Archer (Citation2010, p. 6) refers to as the ‘impulsive and propulsive “I”’ seeking out and exploring new conditions. In both cases, anomolies and contradictions in formerly familiar cultural practices and beliefs appear that can be neither categorised nor ignored. This in turn leads to forms of cognitive dissonance in the loss of secure attachments and the irreconcilability of the extant and the new (Marris, Citation1974).

Both forms of breach require that habit, that summary of past experience, is overcome through deliberations that produce what Valentine and Sadgrove (Citation2014, p. 1981) have described as ‘an intentional recasting of the self’ that may endure, or not last beyond the moment. These reflexive deliberations are imagined by Archer (Citation2007) as an ‘internal conversation’ sustained by the ‘ultimate concerns’ of strong emotional connections. Drawing back from the pre-cognitive and the habitual, her approach gives pre-eminence to agency and the human capacity to transform. While this appears an individual process, Archer reiterates its social dependency. Taking history and place into account, reflexivity is practiced heterogeneously, associated with social formations that vary according to context and that produce ‘distinct personal biographies’ (Archer, Citation2010, p. 11). Reflexivity is then ‘an invitation to explore the interplay between social conditioning and agential responses’ (Archer, Citation2010, p. 12).

Akram and Hogan (Citation2015), however, suggest caution in the over-subscription of reflexivity to agency (see also Farrugia & Woodman, Citation2015). They argue instead that there is a human preference for continuity given the emotional investment in maintaining ontological security, the strength of social ties and the desire to avoid rejection, marginalisation and shame. This ‘conservative impulse’ (Marris, Citation1974) is an investment in preserving meaning in familiarity including interpreting reality through existing cultural frames of reference and avoiding, or reorganising, that which engenders ambiguity and discomfort.

There is little doubt that the scripts of everyday practice and space use are deeply written into subjectivity and identity, as Akram and Hogan (Citation2015) suggest; for example, entrenched heuristics of race and gender (see also Wilson, Citation2016). Such constraints can impede reflexivity as internal conversations may be foreclosed by hegemonic discourse. As Reynolds (Citation2013) has demonstrated, young people cannot unproblematically adopt new behaviours particularly when disapproval of significant others is likely. Preferences and constraints work against each other, as, for example, an individual may be open to contact but not have the opportunity to engage (Gaffikin & Morrissey, Citation2011; Martinović, Citation2013). Strategies to reduce or eliminate affective discomfort can be faced with the inability to impact on change under conditions of globalisation that reach beyond the local (e.g. transnational investment in the housing market in London that drives urban redevelopment).The formation of new practices can also be obstructed by factors such as the speed of change that disables sustained reflection, learning and integration of new or modified practices (Harris, Citation1996). Nor can the argument tilt too far towards agency such that all human life is assumed to be a calculating machine (Reckwitz, Citation2002). It would inevitably be exhausting to exist in a state of permanent reflexivity; a state that would contribute to the conservative impulse noted above and the persistence of routinised everyday practices that reinforce self, others and our place in the order of things.

However, this paper does not dismiss structure or habitus, but rather emphasises the idea that social selves are not simply reactive, nor completely socialised, but rather engaged in processes of reflexivity that enable solutions to be formed. As Wilson (Citation2016) has argued, sites of encounter create the possibility of pedagogy. Nor do I suggest inevitable positive outcomes, given the intersections of social categories brought into any encounter. As Nowicka (Citation2015) has noted, reflexivity may not be transformative particularly when actors lack sufficient resources. It is in fact an aim of this research to explore these limitations and the impact of power relations on the capacity of individuals to engage in reflexive processes. The young people in the CHASH project, for example, lack power within an adult world in which they are also marginalised by socio-economic and racial categories. As a result, as the following findings suggest, reflexivity can engender doubt, resistance, anger as well as transformation. It may be entirely reasonable for a young person to decide not to adapt, or to learn to perform different forms of subjectivity in different spaces, to avoid discomfort and conflict. There is a weighing up of the costs and benefits, including emotional and mental resources required to adapt or maintain continuity, with an understanding that pain may result from either option. But it is a process of reflexivity, a measuring of risks, that enables that decision. As Archer (Citation2010, p. 12) argues, ‘agents are not rational maximisers but strong evaluators’.

Processes of change and contact with difference may even increase reflexive capabilities according to Nowicka (Citation2015).This capacity for plasticity can be demonstrated in the development and deployment of adaptive competencies in order to manage difference and to get along with others, including the imaginative ability to empathise (Bennett, Cochrane, Mohan, & Neal, Citation2016; Butcher, Citation2011; Schuermans, Citation2017). As noted in the following narratives, cultural knowledge and action that informs the nature and outcomes of encounter with others can be a dynamic, mutable set of procedures and understandings. The reflexive agency of judgement and decision-making can also be seen as part of an attempt to untangle the ambivalence of change (Van Leeuwen, Citation2008). In practice, this approach reduces the abstract quality of affect, habit and theories of reflexivity more broadly. It recognises the labour of negotiating change (Permezel & Duffy, Citation2007; Valentine & Sadgrove, Citation2014), as well as the possibilities of agency in managing difference from a position of inequality.

Creating Hackney as Home

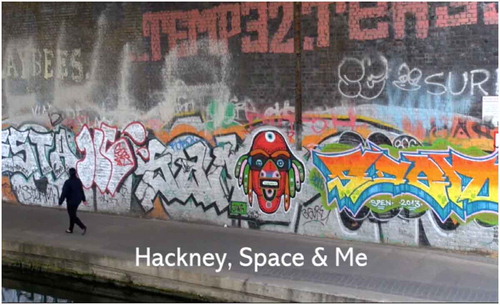

Grounding reflexivity further, place particularises these processes within an ecology of human and built environment, modulated through affective feedback loops of perceived negative and positive encounter, mitigated by factors such as age, class, race, gender and time (Bennett & Crawley-Jackson, Citation2017; Peterson, Citation2016; Valentine & Sadgrove, Citation2014). The site for this research, the east London borough of Hackney, has a complexity of cultural diversity to the extent that it is argued there is an habituated familiarity with difference (Wessendorf, Citation2014). Multiple permutations in the possibilities of daily contact mark out its public spaces. However, it has in recent years also been subject to rapid processes of urban redevelopment resulting from several factors: the Olympic site regeneration; its position close to London’s global financial centre; and a ‘creative cities’ agenda that has led to the growth of digital technology and media industry clusters. A growing population of middle class and creative professionals in the borough,Footnote1 as well as people coming into particular areas for tourism (Broadway Market) and nightlife (Shoreditch, Dalston Junction, Hackney Wick), adds to existing cultural diversity and social inequalities (Census, Citation2011; LBH, Citation2016; Mayhew, Harper, & Waples, Citation2011). Demands from competing stakeholders have led to juxtaposing expectations of space use and a concomitant potential for everyday conflict between residents (see, for example, Hackney Today, Citation2016). It could be argued that it is not so much the meeting of ‘strangers’ but others already ‘known’ through mediatised stereotypes of ‘Hoodie’ and ‘Hipster’ that mark out antagonistic social relations in Hackney (Butcher & Dickens, Citation2016).

Using a participatory visual methodology, the CHASH project was designed to explore how young people from Hackney experienced these changes and subsequent encounters with new residents.Footnote2 Working with community partners, six peer research assistants (PRAs),Footnote3 16–18 years old, were employed on a casual basis from April 2013–March 2014. All were from BME backgrounds and grew up on Hackney social housing estates, but also represented a diversity of attitudes and aspirations: aiming for university or a career in the arts, studying economics, focused on sport, an apprentice, youth worker, retail assistant, introvert and extrovert. All were considered ‘experts’ in observing their neighbourhoods: for example, Matthew, who watched his adjoining estate demolished and the new Dalston Square emerge; or Shekeila, who engages practices of psycho-geography in walking Hackney’s streets to find her own space for reflection.

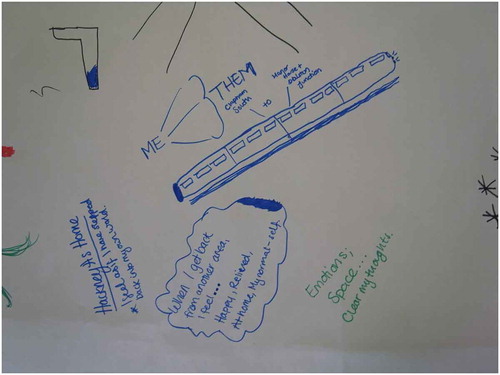

The choice of a participatory methodology was embedded in an understanding of the rights and responsibilities of young people in research contexts (Hopkins, Sinclair, & Student Research Committee, Citation2016: Mallan, Singh, & Giardina, Citation2010). Creative methods have also been found to enable young people to critically reflect on questions of social position and identity (Askins & Pain, Citation2011; Butcher, Citation2009; Fenge, Hodges, & Cutts, Citation2011); allow for self-expression, and the ‘full participation of young people as authors of their auto-biographies’(Bagnoli, Citation2007, p. 27); and evoke not only their social lives but their contribution to theory. Beginning with an initial two-day workshop, the PRAs developed their ideas for a film exploring the theme of ‘Home’, and were then responsible for research and film production over the course of the year supported by mentoring from the research team ().

Of key interest to this paper was material collected as part of the PRA’s critical reflections made throughout the project, primarily in video diaries. This method was used for its capacity to document thought processes, particularly indications of learning and transformation (see Ganesh & Holmes, Citation2011; Lavanchy, Gajardo, & Dervin, Citation2011; Roberts, Citation2011). Each PRA was given a flip-camera to record, whenever they chose, their thoughts about their film and the project as it developed. A rich, diverse data-set was generated that encapsulated the complexity of their experiences of a changing neighbourhood, the prosaic challenges of research and film-making, as well as the immediacy of their personal lives; the housing crisis, inequalities, frustrations and aspirations that had to be negotiated. This material became the basis of further discussion in one-to-one debriefs and within the team, generating themes as part of the analysis of emerging data (e.g. power and identity).Footnote4 These themes in turn became the subject of further reflection, building on our analysis using both the immediacy of the diaries as well as their possibility for replay. Recordings of both personal reflections and subsequent discussions were transcribed and coded.

In summary, the diaries captured the ‘internal conversations’ that informed the PRA’s decision-making and motivations for action at particular moments of encounter, in both the project and their daily lives. These deliberations, starting from a general position of ambivalence in their assessment of gentrification more broadly (Butcher & Dickens, Citation2016), were often impelled by perceptions of the judgments of classed (middle) and racialised (white) others who they were now required to share Hackney’s public spaces with. Subsequent processes and outcomes of reflexivity centred on four key areas: the extent to which change was accepted as necessary in the realisation that they were now ‘different’ in their own neighbourhoods; the re-working of space use (avoidance as well as finding points of contact); the adaptation of everyday practices such as dress and food consumption that highlighted the capacity for curiosity and flexibility, as well as the discomfort involved in managing difference; and deploying practices of engagement such as adjusting communication styles and developing positions of empathy, shifting attitudes and perceptions of others and themselves in the process.

Accepting change, re-working space

you can’t be in a gang in Hackney and wear chinos, that’s straight up.

you don’t eat chicken and chips on a bus in south London.

As Monét and Shekeila illustrate, above, there is an acute understanding of the cultural frameworks, learned and shared, governing everyday practices, reflecting the idea of culture as a set of ‘rules’ acquired in the course of living within a particular milieu. For the young people in this study, an assemblage of everyday practices, relationships, and built environment generated and reinforced familiarity within concentric cultural frameworks: with peers, adults and local authorities in particular. There was an awareness, however, that these ‘rules’ are mutable, that is, guidelines that can be questioned. Encounters between the visibly different expectations of space use in gentrifying neighbourhoods heightened this process of reflexivity, including the necessity to accept change and adjust ‘with the times’.

Yeah, it’s changing, it’s changing for, it is changing for the good, but not too much. It is changing for the bad as well, but not too much bad. It’s balanced. You just have to change with the times man. (Tyrell, debrief, 08 /07/14)

Obviously, it’s a comfort zone and then after you leave that comfort zone, you have to find a new comfort zone … (Monet, diary, 08/05/13)

And when we were talking about the changes in Hackney it was still under wraps, it was coming, it was popping up in places, but now it’s like so in your face you can’t escape it. […] You kind of have got to go with it. If you don’t adapt you’re pissed. It naturally just happens, with all the new cafes that are popping up everywhere. GreggsFootnote5 has closed in Hoxton. I was like, ‘what, where am I supposed to get my sausage roll from now? Everything is gone’. I don’t know. I still love Hackney. (Monét, debrief, 22/07/14)

Matthew’s comments hint at the importance of time in processes of adaptation and the outcomes of encounter. The continuity of cultural knowledge enables the prediction of outcomes, the ability to attach meaning and respond appropriately to experiences and events, as well as to be able to predict how others will respond in order to avoid collisions in crowded, complex cities (Herbert, Citation2008; Pagani et al., Citation2011; Phillips & Smith, 2006). The desire for this stability does not preclude the incorporation of new ideas, but this is done cumulatively, within limits, as new experiences are assimilated within familiar contexts. Therefore, the dissonance of gentrification’s breach of existing cultural frameworks in Hackney is exacerbated by the speed of change, when there is no time to become ‘used to’ difference. As noted by Matthew ‘it’s all happening at such a fast pace’ (debrief, 16/09/14).

The lack of familiarity with how particular spaces in Hackney should now be used resulted at times in the re-working of space, particularly strategies of avoidance. Broadway Market, a part of Hackney that was once Tyrell’s home, and which he described as ‘losing its culture’, is now ‘hurried through’ to avoid the judgement that is perceived in the presence of new, ‘hipster’, residents, even if no actual contact takes place.

Sometimes I see [a friend] walking and it’s just like he tries to walk a bit faster, he’s not really used to the … like on that street he don’t really chill there, like, as in like stand about and talk to his friends no more. (Tyrell, debrief, 08/07/14)

Choosing to avoid or exile themselves from particular space, or perhaps feeling that they have no choice, appears as a negative outcome of gentrification’s breach of former expectations of space use. However, Shekeila demonstrates both the impact of disposition in the capacity to deliberate (e.g. others chose to stay closer to home), as well as Noble’s (Citation2013, p. 177) argument that it is ‘the movements between spaces, not just repetitive actions within them, which are formative of the plasticity of habit’. Her practice of roaming through the city captured in her diary was not just a response to gentrification or housing insecurity, but also consciously exploring her sense of self; a curiosity driven by an apparent desire to experience difference. By choosing to attend college in south London, and working part-time in the West End, she travelled across the city each day, deliberately choosing to de-stabilise her boundaries while also noting in her film script that this can come at a cost to a sense of comfort. ‘It’s nice to get away from the normal and it’s something different. But when I’ve been away for a while it’s a relief to come home’.

Reflecting flexibility and judgement

Adapting particular material practices was a further indication of reflexive agency and an awareness of codes of comportment that they could deliberately break, conform to or experiment with under conditions of breach. In particular, flexibility was highlighted in practices of dress and food. Both Michael and Tyrell’s research pointed to how young men adjust dress and comportment to avoid being stereotyped as ‘gangsta’, aware of the implications of ‘hoodies’ and puffer jackets. But this response raises the role of judgement in reinforcing or directing their practices to different extents; judgments not only of themselves but that they make of others, as Matthew explained:

To be honest, I wont lie, I do it all the time and I think everybody does it whether they say they do or not, I think everybody does do it because it’s just part of human life … everybody has judged someone … everybody can look [at] a person wearing certain things and judge somebody … (diary, 09/05/13)

I think I do need to go into that pub down the road, but … every time I go in a pub I’m expected, the bartender just looks at me like I’m … ‘What’s this nigger doing here?’ … they just seem like I’m not meant to be in the bar … I’m gonna go in there soon, but … (Tyrell, diary, 05/11/13)

Basically, yeah, like sometimes I wear a tracksuit knowing that I’m going to an important place where I’ll network with people and then when they ask me what do you do with yourself, they’re expecting me to say ‘oh I don’t go to college or anything’, I shock them with saying whatever I do, and I find that it makes me happy sometimes … to know that they prejudged me before you got to know me by what I was wearing, it doesn’t matter, you should’ve at least heard my voice before you prejudged me by what I was wearing.

… it kind of shows that there is a bit of change, but nothing financially has changed for me, it’s just more of like my preferences are changing, and, in a way, it has been brought on by the changes in Hackney because of all these new places and all these new people: they bring new styles and new things … and, not to say that you want to change and be like them but you kind of want to understand what they like and try to see if you may like it as well, cos in a way it’s kind of like finding out about yourself, like you’re always gonna find new things about yourself – what you do like, what you don’t like, what you find interesting and what you just have no care in the world about. (Matthew, diary, 20/07/13)

If you notice, just then, I just changed my dialect throughout because as a person, you get judged through your identity … people will try and judge you, they will try and mock you, they will try to bully you, they will try and discriminate, oppress, even some people will be the oppressors, but everyone has their own different experiences, and everyone is an individual. (Josh, diary, 20/05/13)

Transforming encounter

It must be noted that contact between new residents and young people in this study was minimal, accidental and transitory at best, indicative of the difficulties in trying to create a ‘place for everyone’Footnote6 under conditions of rapid change. But that misperception, judgements and stereotyping caused pain and discomfort is without doubt. As Valentine and Sadgrove (Citation2014, p. 1982) argue, ‘raced memories and affects accumulate’ as encounters with difference are contextualised by the cultural baggage that an individual carries into any encounter. In addition, immersed in change not of their making, it is these young people that are required to engage reflexively in order to adapt, while those moving in habitually reproduced cultural frames of reference using their financial and cultural capital to appropriate and convert spaces into their own likeness. Hackney has seen a qualitative and quantitative shrinkage of space in which young people involved in the CHASH project felt they belonged.

The impact of different understandings of the knowledge and practices necessary to negotiate Hackney today is illustrated by Wadsley and Butcher (Citation2015) in their study on barriers to young people gaining access to employment and training opportunities in Hackney’s burgeoning digital hubs (see also Morgan & Idriss, Citation2012). Referring to differences in cultural capital, a major issue in accessing employment opportunities in this sector for young people from marginalised backgrounds is their perceived inability to ‘speak the language’ of the digital workplace; to not know what to speak about nor how to comport themselves.

However, several young people in this study demonstrated a reflexive capacity to develop and deploy skills that enabled them to navigate difference more competently. This, in particular, involved the adaptation of language, and the development of empathy. Demonstrating how she shifts the way she speaks, Monét notes the generation of discomfort in this labour of interpersonal, intergenerational contact.

Like talking to people, you have to change. You might change your lingo, your tone or your body language. Like if I’m interviewing an older person, I put on this dumb voice like, it’s not me, like it’s my voice, but it’s not me if you know what I mean, like being really polite and pronunciate every single letter, or whatever letters. It’s uncomfortable man. (Monet, team discussion, 28/04/13)

However, expressions of empathy, requiring the capacity to reflect on the state of mind of ‘the other’, suggest the potential to transform the outcomes of social interaction. Tyrell expressed an understanding that what he perceived other people to be thinking may not actually be the case.

I was walking past the bus [in Camden] and everyone was looking at us, I don’t know if it was to do with race or my colleague, Monét, was talking too loud on the phone so we don’t know because we never know what anyone’s thinking, so … they could be thinking that ‘oh I’ve never seen these people around here’, things like that, so you can always misjudge what people are thinking so yeah … that’s something to think about too, like why do I think like this? Maybe I think like this because the environment has made me like this, maybe it’s not me … (Tyrell, diary, 14/05/13)

Because I’d think that the people that will come here and move in are rich … but then, they’re not actually rich when you talk to them and get to know them they’re just normal people who are trying to get a living. … I used to think these people were just like, they don’t really care and they don’t really, but actually, they’re just normal people. It does change you, looks can be deceiving. (debrief, 08/07/14)

Conclusion

Gentrification in Hackney has led to a breach in the synchronicity between cultural frames of reference and place, shifting the composition and meeting points of encounter and generating ambiguity and affective discomfort in the process. With change ‘in your face’ on a daily basis, the young people in this study operated within what Reckwitz (Citation2002) described as interpretative crises, marked by the inadequacy of existing knowledge to manage unfamiliar encounters. There was the discomfort of becoming different at home as well as marked by inequalities, positioned within aged and socio-economic hierarchies, subject to displacement pressures and urban authorities that determine land use and housing policy. While new practices were needed to access changing city spaces and their contingent assemblies, there was privilege embedded in the uneven expectation of who has to adapt to fit in. Processes of reflexivity were therefore instigated within a context not of these young people’s making.

However, while power and privilege are inherent in the spatial transformation of Hackney, this research suggests that young people are not passive in the midst of this change. In experiencing the breaking and shifting of personal and social structures, that which was once un-thought of had the potential to emerge as a possibility to become part of a process of managing difference (Akram & Hogan, Citation2015). ‘Internal conversations’ (Archer, Citation2010) captured in the diaries and discussions in this study, highlighted that under conditions of breach there were conscious processes of re-evaluation and a suppleness in responses to new cultural contexts in an effort to untangle the ambivalence of gentrification. Deliberations, a series of choices that are part of the ‘doing of encounter’ as Wilson (Citation2016) notes, are seen in this study as a means to negotiate ‘fitting in’ (with both peers and new neighbours), and to renegotiate, within limits, forms of inclusion and exclusion. Change could be accepted, if reluctantly, everyday practices and place could be modified, and space use, and themselves, re-worked as part of adaptive strategies to alleviate dissonance. Skills such as empathy and dispositions such as curiosity enabled the crossing of boundaries that could transform encounters, generating the potential for new ways of thinking about self and others in a search for competent social agency. Affective responses to shifting cultural cues facilitated this reflexivity. The discomfort generated in the anomalies of change impelled a re-evaluation of subjectivity for some, drawing on the new cultural resources on offer, and moulded over time through repeated interactions with other people and re-versioned places in their neighbourhoods.

Yet while Archer (Citation2010) emphasised the production of ‘novel’ action as a result of reflexivity, these findings demonstrate that deliberation does not inevitably lead to innovation. When the potential for encounter was dominated by feelings of judgement, a conscious decision of avoidance or withdrawal could be made. The perceived entitlement to space by new residents could be challenged, but demolitions or affective forms of exclusion are not stopped. Empathy, while enabling a deeper understanding of the behavioural responses of others, can only translate into the political work of diminishing exclusion when it becomes bi-directional: a process hampered in Hackney I would argue by the minimisation of spaces of contact. The decision to maintain strong attachments, such as extant friendship networks, could ensure continuity and create meaningful patterns of relationships in the present, alleviating the discomforts of change. But this could also impede the curiosity and willingness for an engagement with difference that supports desired shifts in subjectivity, generating dissonance and frustration as seen at times in this study.

Here then I would disagree with Archer’s (Citation2010, p. 9) argument that reflexivity ‘trumps’ dispositions because ‘it can assess them, find them wanting, and elaborate alternatives’. For some this is a possibility, but individual capacities to manage change need to be taken into account to understand why responses to the same circumstances can differ. The choices of maintenance or exploration that result from reflexive processes are inflected by disposition: some have the will to put their body into unfamiliar situations and see what happens while others weigh up extant cultural frameworks, particularly relationship networks, as a better option even if it comes with its own frustrations and discomfort. As ‘strong evaluators’, these young people demonstrate diverse motivations, outcomes and benchmarks of what they are willing to settle for. There are different levels of willingness as well as capacities to reflexively re-evaluate subjective positions, to adapt to transforming cultural contexts, to choose to avoid the discomfort of transgression but also at times expressing a desire to feel it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Funding

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/K002066/1].

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend her deepest thanks to the PRAs and participants in the CHASH project. Early drafts of this paper were helped immensely by feedback from Gideon Bold, Peter Kraftl and the three anonymous peer reviewers. The project was ably assisted by Luke Dickens, Nadia Bartolini, Johanna Wadsley and Olly Zanetti.

Notes

1. The borough has benefited from rapid economic growth since 2010, with companies in key knowledge industries (e.g. digital, media) comprising 55% of the local economy. The overall statistics suggest that employment is higher, with a better educated, better skilled workforce. While it is still the 11th most deprived local authority in England, this is a significant improvement on its 2nd position in 2010. However, in correlation with these figures is the movement of people out of and into the borough. The highest levels of non-UK in-migration were from Australia, the USA and Western European countries suggesting gentrified displacement (2011 census, LBH, Citation2016). While Hackney has always been home to a middle-class population, under current conditions long-time residents from this socio-economic bracket are also being squeezed out of the borough through rent and property price increases.

2. See www.hackneyashome.co.uk for more details on the research team and methodology.

3. There were initially six PRAs employed with one leaving the project after the third month. The team are referred to in this paper as: Monét, Shekeila, Josh, Matthew, Michael, and Tyrell.

4. During the film-making period, summer 2013, PRAs could meet with the RA or PI each week to discuss material from their diaries as well as the research process. Throughout autumn and into winter 2014, bi-weekly team meetings were held to analyse emerging themes. There was a final one-on-one debrief with each of the PRAs at the end of the project.

5. A cheap bakery chain in comparison to the artisanal bakers that are now a well-established presence in Hackney.

6. Hackney council began a borough wide consultation in 2015 under the rubric of ‘Hackney: a place for everyone?’, to identify resident’s concerns about the social and economic transformations in the borough (https://www.hackney.gov.uk/HAPFE).

References

- Ahmed, S. (2004). Collective feelings. Theory, Culture and Society, 21, 25–42.10.1177/0263276404042133

- Akram, S., & Hogan, A. (2015). On reflexivity and the conduct of the self in everday life: Reflections on Bourdieu and Archer. British Journal of Sociology, 66, 605–625.

- Amin, A. (2012). Land of strangers. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Amin, A. (2008). Collective culture and urban public space. City, 12, 5–24.10.1080/13604810801933495

- Anderson, B. (2009). Affective atmospheres. Emotion, Space & Society, 2, 77–81.10.1016/j.emospa.2009.08.005

- Anthias, F. (2001). New hybridities, old concepts: The limits of ‘culture’. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24, 619–641.10.1080/01419870120049815

- Archer, M. (2007). Making our way through the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511618932

- Archer, M. (2010). Introduction: The reflexive re-turn. In M. Archer (Ed.), Conversations about reflexivity (pp. 1–14). London: Routledge.

- Askins, K., & Pain, R. (2011). Contact zones: Participation, materiality, and the messiness of interaction. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29, 803–821.10.1068/d11109

- Awan, N. (2012). Kurdistan in London. In R. Tyszczuk, J. Smith, N. Clarke, & M. Butcher (Eds.), ATLAS: Geography, architecture and change in an interdependent world (pp. 42–47). London: Black Dog.

- Bacqué, M.-H., Charmes, E., & Vermeersch, S. (2014). The middle class ‘at home among the poor’ – How social mix is lived in Parisian suburbs: between local attachment and metropolitan practices. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, 1211–1233.10.1111/ijur.2014.38.issue-4

- Bagnoli, A. (2007). Between outcast and outsider: Constructing the identity of the foreigner. European Societies, 9, 23–44.10.1080/14616690601079424

- Bennett, K., Cochrane, A., Mohan, G., & Neal, S. (2016). Negotiating the educational spaces of urban multiculture: Skills, competencies and college life. Urban Studies ( online edition). doi:10.1177/0042098016650325

- Bennett, L., & Crawley-Jackson, A. (2017). Making common ground with strangers at Furnace Park. Social and Cultural Geography, 18, 92–108.10.1080/14649365.2016.1231835

- Bloch, B., & Dreher, T. (2009). Resentment and reluctance: Working with everyday diversity and everyday racism in southern Sydney. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 30, 193–209.10.1080/07256860902766982

- Britton, M. (2011). Close together but worlds apart? Residential integration and interethnic friendship in Houston. City & Community, 10, 182–204.10.1111/cico.2011.10.issue-2

- Brown, G. (2011). Emotional geographies of young people’s aspirations for adult life. Children’s Geographies, 9, 7–22.10.1080/14733285.2011.540435

- Butcher, M. (2009). Re-writing Delhi: Cultural resistance and cosmopolitan texts. In M. Butcher & S. Velayutham (Eds.), Dissent and cultural resistance in Asia’s cities (pp. 168–184). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Butcher, M. (2011). Managing cultural change: Reclaiming synchronicity in a mobile world. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Butcher, M., & Dickens, L. (2016). Spatial dislocation and affective displacement: Youth perspectives on gentrification in London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40, 800–816.10.1111/1468-2427.12432

- Butler, T. (2003). Living in the bubble: Gentrification and its ‘others’ in north London. Urban Studies, 40, 2469–2486.10.1080/0042098032000136165

- Butler, T., Hamnett, C., & Ramsden, M. J. (2013). Gentrification, education and exclusionary displacement in east London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37, 556–575.10.1111/ijur.2013.37.issue-2

- Census. (2011). London borough of Hackney. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from https://www.hackney.gov.uk/census-2011.htm#.Uzk1styYYds

- Clayton, J. (2012). Living the multicultural city: Acceptance, belonging and young identities in the city of Leicester, England. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35, 1673–1693.10.1080/01419870.2011.605457

- Conradson, D., & Latham, A. (2007). The affective possibilities of London: Antipodean transnationals and the overseas experience. Mobilities, 2, 231–254.10.1080/17450100701381573

- Crozier, G., & Davies, J. (2008). ‘The trouble is they don’t mix’: Self‐segregation or enforced exclusion? 1. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 11, 285–301.10.1080/13613320802291173

- Davison, G., Dovey, K., & Woodcock, I. (2012). “Keeping Dalston different”: Defending place-identity in east London. Planning Theory & Practice, 13, 47–69.10.1080/14649357.2012.649909

- Dirksmeier, P., & Helbrecht, I. (2015). Everyday urban encounters as stratification practices. City, 19, 486–498.10.1080/13604813.2015.1051734

- Drew, E. (2011). ‘Listening through white ears’: Cross-racial dialogues as a strategy to address the racial effects of gentrification. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34, 99–115.

- Farrugia, D., & Woodman, D. (2015). Ultimate concerns in late modernity: Archer, Bourdieu and reflexivity. The British Journal of Sociology, 66, 626–644.10.1111/1468-4446.12147

- Fenge, L., Hodges, C., & Cutts, W. (2011). Seen but seldom heard: Creative participatory methods in a study of youth and risk. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10, 418–430.

- Gaffikin, F., & Morrissey, M. (2011). Community cohesion and social inclusion: Unravelling a complex relationship. Urban Studies, 48, 1089–1118.10.1177/0042098010374509

- Ganesh, S., & Holmes, P. (2011). Positioning intercultural dialogue-theories, pragmatics, and an agenda. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 4, 81–86.10.1080/17513057.2011.557482

- Garbin, D., & Millington, G. (2012). Territorial stigma and the politics of resistance in a Parisian banlieue : La Courneuve and beyond. Urban Studies, 49, 2067–2083.10.1177/0042098011422572

- Gilligan, R., Shannon, S., & Curry, P. (2007, September 24). First stages of an intensive case study of community relations in two north-inner city Dublin schools. Dublin: Trinity Immigration Initiative Migration Research Fair, Trinity College.

- Hackney Today. (2016, May 23). Respect our parks. Issue 379, 1.

- Harris, A. (2010). Young people, everyday civic life and the limits of social cohesion. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 31, 573–589.10.1080/07256868.2010.513424

- Harris, C., Jackson, L., Piekut, A., & Valentine, G. (2017). Attitudes towards the ‘stranger’: Negotiating encounters with difference in the UK and Poland. Social and Cultural Geography, 18, 16–33.10.1080/14649365.2016.1139165

- Harris, K. (1996). Collaboration within a multicultural society. Remedial and Special Education, 17, 355–362.10.1177/074193259601700606

- Herbert, S. (2008). Contemporary geographies of exclusion I: Traversing skid road. Progress in Human Geography., 32, 659–666.10.1177/0309132507088029

- Hopkins, P, Sinclair, C., & Student Research Committee. (2016). Research, relevance and respect: Co-creating a guide about involving young people in social research. Research for all. London: UCL IOE Press.

- Jackson, E., & Benson, M. (2014). Neither ‘Deepest, Darkest Peckham’ nor ‘Run-of-the-Mill’ East Dulwich: The middle classes and their others in an inner-London Neighbourhood. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, 1195–1210.10.1111/ijur.2014.38.issue-4

- Karner, C., & Parker, D. (2011). Conviviality and conflict: Pluralism, resilience and hope in inner-city Birmingham. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37, 355–372.10.1080/1369183X.2011.526776

- Kraftl, P. (2013). Beyond ‘voice’, beyond ‘agency’, beyond ‘politics’? Hybrid childhoods and some critical reflections on children’s emotional geographies. Emotion, Space & Society, 9, 13–23.10.1016/j.emospa.2013.01.004

- Landau, L., & Freemantle, I. (2010). Tactical cosmopolitanism and idioms of belonging: Insertion and self-exclusion in Johannesburg. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36, 375–390.10.1080/13691830903494901

- Lavanchy, A., Gajardo, A., & Dervin, F. (2011). Interculturality at stake. In F. Dervin, A. Gajardo, & A. Lavanchy (Eds.), Politics of interculturality (pp. 1–25). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing.

- Lawler, E. (2001). An affect theory of social exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 321–352.10.1086/324071

- LBH. (2016. September ). A profile of Hackney, its people and place. London Borough of Hackney Policy Team. Retrieved from January 24, 2017, from https://www.hackney.gov.uk/Assets/Documents/Hackney-Profile.pdf

- Mallan, K., Singh, P., & Giardina, N. (2010). The challenges of participatory research with ‘tech-savvy’ youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 13, 255–272.10.1080/13676260903295059

- Marris, P. (1974). Loss and change. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Martinović, B. (2013). The inter-ethnic contacts of immigrants and natives in the Netherlands: A two-sided perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39, 69–85.10.1080/1369183X.2013.723249

- Massey, D. (2005). For space. London: Sage.

- Mayhew, L., Harper, G., & Waples, S. (2011). Counting Hackney’s population using administrative data – An analysis of change between 2007–2011. Report commissioned by Hackney Council, Mayhew Harper Associates, London.

- Morgan, G., & Idriss, S. (2012). ‘Corsages on their parents’ jackets’: Employment and aspiration among Arabic-speaking youth in western Sydney. Journal of Youth Studies, 15, 929–943.10.1080/13676261.2012.683405

- Muir, R., & Wetherell, M. (2010). Identity, politics and public policy. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Nayak, A. (2010). Race, affect, and emotion: Young people, racism, and graffiti in the postcolonial English suburbs. Environment & Planning A, 42, 2370–2392.10.1068/a42177

- Neal, S., Vincent, C., & Iqbal, H. (2016). Extended encounters in primary school worlds: Shared social resource, connective spaces and sustained conviviality in socially and ethnically complex urban geographies. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37, 464–480.10.1080/07256868.2016.1211626

- Noble, G. (2011). ‘Bumping into alterity’: Transacting cultural complexities. Continuum, 25, 827–840.10.1080/10304312.2011.617878

- Noble, G. (2013). Cosmopolitan habits: The capacities and habitats of intercultural conviviality. Body & Society, 19, 162–185.10.1177/1357034X12474477

- Nowicka, M. (2015). Bourdieu’s theory of practice in the study of cultural encounters and transnational transfers in migration ( Working Paper 15-01). Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity. Retrieved July 01, 2016, from https://www.mmg.mpg.de/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/wp/WP_15-01_Nowicka_Bourdieus-theory.pdf

- Pagani, C., Robustelli, F., & Martinelli, C. (2011). School, cultural diversity, multiculturalism, and contact. Intercultural Education, 22, 337–349.10.1080/14675986.2011.617427

- Permezel, M., & Duffy, M. (2007). Negotiating the geographies of cultural difference in local communities: Two examples from suburban Melbourne. Geographical Research, 45, 358–375.10.1111/ages.2007.45.issue-4

- Peterson, M. (2016). Living with difference in hyper-diverse areas: How important are encounters in semi-public spaces? Social and Cultural Geography (online edition). doi:10.1080/14649365.2016.1210667

- Phillips, T., & Smith, P. (2006). Rethinking urban incivility research: Strangers, bodies and circulations. Urban Studies, 43, 879–901.10.1080/00420980600676196

- Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5, 243–263.10.1177/13684310222225432

- Reynolds, D. (2013). ‘Them and us’: ‘Black neighbourhoods’ as a social capital resource among Black youths living in inner-city London’. Urban Studies, 50, 484–498.10.1177/0042098012468892

- Roberts, J. (2011). Video diaries: A tool to investigate sustainability-related learning in threshold spaces. Environmental Education Research, 17, 675–688.10.1080/13504622.2011.572160

- Schuermans, N. (2017). White, middle-class South Africans moving through Cape Town: Mobile encounters with strangers. Social and Cultural Geography, 18, 34–52.10.1080/14649365.2016.1216156

- Simonsen, K., & Koefoed, L. (2015). Ambiguity in urban belonging. City, 19, 522–533.10.1080/13604813.2015.1051742

- Smollan, R. K. (2006). Minds, hearts and deeds: Cognitive, affective and behavioural responses to change. Journal of Change Management, 6, 143–158.10.1080/14697010600725400

- Tasan-Kok, T., van Kempen, R., Raco, M., & Bolt, G. (2014). Towards hyper-diversified European cities: A critical literature review. Utrecht: Utrecht University, Faculty of Geosciences.

- Tissot, S. (2014). Loving diversity/controlling diversity: Exploring the ambivalent mobilization of upper-middle-class gentrifiers, South End, Boston. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38, 1181–1194.10.1111/ijur.2014.38.issue-4

- Valentine, G., & Sadgrove, J. (2014). Biographical narratives of encounter: The significance of mobility and emplacement in shaping attitudes towards difference. Urban Studies, 51, 1979–1994.10.1177/0042098013504142

- Van Leeuwen, B. (2008). On the affective ambivalence of living with cultural diversity. Ethnicities, 8, 147–176.10.1177/1468796808088921

- Vertovec, S. (Ed.). (2015). Diversities old and new: Migration and socio-spatial patterns in New York, Singapore and Johannesburg. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vieten, U. M., & Valentine, G. (2015). European urban spaces in crisis. City, 19, 480–485.10.1080/13604813.2015.1051731

- Visser, K., Bolt, G., & van Kempen, R. (2015). ‘Come and live here and you’ll experience it’: Youths talk about their deprived neighbourhood. Journal of Youth Studies, 18, 36–52.10.1080/13676261.2014.933196

- Wadsley, J., & Butcher, M. (2015). Young people’s participation in TechCity: Barriers and opportunities. Retrieved from https://www.hackneyashome.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/OpenUniversity_Young-Peoples-Participation-in-Tech-City_March2015_0.pdf

- Wallace, A. (2014). The English riots of 2011: Summoning community, depoliticising the city. City, 18, 10–24.10.1080/13604813.2014.868161

- Watson, S. (2006). City publics: The (Dis)enchantments of urban encounters. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Watt, P. (2013). ‘It’s not for us?’. City, 17, 99–118.10.1080/13604813.2012.754190

- Wessendorf, S. (2014). Commonplace diversity: Social relations in a super-diverse context. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Willes, M. (Ed.). (2012). Hackney: An uncommon history in five parts. London: Hackney Society.

- Wilson, D., & Grammenos, D. (2005). Gentrification, discourse, and the body: Chicago’s Humboldt Park. Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, 23, 295–312.10.1068/d0203

- Wilson, H. (2011). Passing propinquities in the multicultural city: The everyday encounters of bus passengering. Environment and Planning A, 43, 634–649.10.1068/a43354

- Wilson, H. (2016). On geography and encounter: Bodies, borders and difference. Progress in Human Geography (online edition). doi:10.1177/0309132516645958

- Wise, A. (2005). Hope and belonging in a multicultural suburb. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 26, 171–186.10.1080/07256860500074383

- Yeoh, B. (2005). Observations on transnational urbanism: Possibilities, politics and costs of simultaneity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 31, 409–413.10.1080/1369183042000339006