ABSTRACT

Feminist geopolitics has long been interested in deconstructing the assumptions of its masculinist counterpart, complicating notions of where geopolitics takes place and the agents and actions it involves. The geographies of making have similarly been interested in taken-for-granted processes, bodies and materialities, and the ways that they are implicated in wider cultural and political processes. These two areas converge within the phenomenon of charitable knitting. This article centres around research undertaken at a charity that sends donated knitted objects to refugees, food banks and others in need. Through a set of 15 interviews with knitters and volunteers at the charity, along with my own volunteer ethnography, this paper investigates how the geopolitical imaginations of those involved in the charity, shape its work and constructs certain bodies as being ‘needier’ than others. Making for, or knitting for, these bodies is an important part of the process, both as something that is thought to make connections between bodies, but also as practice that has inherent benefits for those doing the knitting. Through these discussions, the paper considers who ultimately benefits, and is cared for, by the work the charity does.

La geopolítica feminista ha estado interesada desde hace mucho tiempo en deconstruir los supuestos de su contraparte masculinista, complicando las nociones de dónde tiene lugar la geopolítica y los agentes y acciones que involucra. Las geografías del hacer se han interesado de manera similar en procesos, cuerpos y materialidades que se dan por sentados, y en las formas en que están implicados en procesos políticos y culturales más amplios. Estos dos ámbitos confluyen en el fenómeno del tejido benéfico. Este artículo se centra en la investigación realizada en una organización benéfica que dona objetos tejidos a refugiados, bancos de alimentos y otros en necesidad. A través de una serie de 15 entrevistas con tejedores y voluntarios de la organización benéfica, junto con mi propia etnografía voluntaria, este artículo investiga cómo la imaginación geopolítica de los involucrados en la organización benéfica da forma a su trabajo y construye ciertos cuerpos como ‘más necesitados’ que otros. Fabricar o tejer estos cuerpos es una parte importante del proceso, tanto como algo que se cree que hace conexiones entre los cuerpos, pero también como práctica que tiene beneficios inherentes para quienes tejen. A través de estas discusiones, el artículo considera quién se beneficia en última instancia y quién se cuida con el trabajo que realiza la organización benéfica.

La géopolitique féministe s’intéresse depuis longtemps à déconstruire les présomptions de son homologue masculiniste, compliquant les concepts des lieux où les géopolitiques prennent place ainsi que les acteurs et les actes que cela implique. De façon semblable, la géographie de la fabrication s’intéresse aux processus, aux entités et aux matérialités tenus pour acquis, et aux manières dont ils sont impliqués dans des processus culturels et politiques plus larges. Ces deux domaines convergent dans le phénomène du tricot solidaire. Cet article s’articule autour de recherches entreprises au sein d’un organisme bénévole qui envoie des articles tricotés aux réfugiés, aux banques alimentaires et aux personnes dans le besoin. À travers 15 entretiens avec des tricoteuses et des volontaires de cet organisme, et avec ma propre ethnographie de bénévole, cette communication examine la manière dont l’imagination géopolitique des personnes œuvrant pour l’organisme bénévole façonne ses travaux et érige que certaines entités ont « plus de besoins » que d’autres. Pour ces entités, l’acte de fabriquer, autrement dit de tricoter, est une part importante de ce processus, à la fois parce que c’est quelque chose que l’on conçoit comme un lien entre les entités ainsi qu’une pratique qui profite aux personnes qui font le tricot de manière fondamentale. Au travers de ces dialogues, la communication examine qui au bout du compte bénéficie du travail de l’organisme bénévole, et de qui ce travail prend soin.

Palabras clave:

Casting on: knitting and its geopolitical potential

Geopolitics is the study of the spatial ways power relations unfold; intimate geopolitics is the way ‘that geopolitical struggle is entangled in and comprised through our day-to-day intimate interactions with one another’ (Smith, Citation2020, p. 282). Intimate geopolitics, and feminist geopolitics more broadly emphasise the political-ness of things that were often deemed apolitical (Brickell, Citation2012, p. 576), but also the neglect of particular bodies and voices from traditional geopolitics (Mott & Cockayne, Citation2017). As Smith (Citation2012, p. 1523) highlights bodies and emotions are not without geopolitical importance ‘as individuals are caught up in the animation of geopolitical projects, love, fear, anxiety, and pain come to play a role … ’. Furthermore, Barabantseva et al. (Citation2019, p. 2) describe the intimate as something that: ‘ … thus foregrounds multi-scalar connections across global-local and past-present continuums … ’ This paper introduces an important site and process for intimate geopolitical attention; that of making. It calls for the weaving of creative subjects with intimate geopolitical concepts, both in theory and the practice of doing research. Both the geographies of making and intimate geopolitics aim to draw attention to often taken-for-granted processes, materialities and bodies, and how these interact with one another on a myriad of scales.

Hawkins and Price (Citation2018, p. 232) argue that making holds transformative power over materials and social relations it involves. Their edited collection considers how making transcends scales and sites, but also the ability it has to form interactions between bodies, materials and processes in unique ways. This reference to the body, in this case, as a maker, has been conceptualized by feminist scholars as sites of geopolitical action, on and through which geopolitics is performed (Dowler & Sharp, Citation2001; Hyndman, Citation2010). This article focuses on the intersections between intimate geopolitics and the geographies of making, investigating the motives and imaginations of those making for the ways they construct other bodies that heavily influences the work that knitting does in the world.

This article focuses on a charity whose work revolved around making for others. They find a home for donated knitted objects, from jumpers to socks, to premature ‘preemie’ baby clothes, giving them to those the charity identified as being in need. I was drawn to the charity when I discovered its campaign to send donations to refugees in camps in Kurdistan, and those living in the UK. After spending time there, however, I realised that its relations to both its knitting-donors and the receivers of its gifts were far more complex than it first appeared. I found myself having to come to terms with the idealised view I had of these activities as altruistically driven and free of inequalities of power.

The process of knitting, especially as a gift, makes objects that ‘ … are deliberately made with a purpose and/or recipient in mind … as gifts, as fundraisers or acts of philanthropy, to decorate the home as a sign of personal identity, and so on’ (Turney, Citation2012, p. 305). By sending these items to refugees, the charity was responding to a global crisis with an alternative method of action, embedded with generosity and creativity, intertwining these small acts with large-scale politics. Similar to the way Pain (Citation2009, p. 535) conceptualizes scale as a double helix, ‘ … two equivalent strands (geopolitics and the everyday life) wind[ing] into a single structure … ’, charitable knitting aims to weave together global crises with the comfort of bodies, using the object and process of knitting to craft a closeness between bodies that will never know one another. Yet, these created connections may take shape in a different way than those imagined by their creators.

This raised questions about what the charity and their donors hoped to achieve through making, parcelling, and donating. By making things in their homes, community centres and knitting groups, they would imagine distant people beyond their national borders, places imagined to be hot with conflict and trauma. This is yet another way we see the weaving together of scales. The ‘hot’ and ‘banal’, as Christian et al. (Citation2016, p. 66) describes it, is wound together by woolly threads with the hope that knitted blankets may smother the fiery heat of spaces imagined to be rife with conflict.

This paper will be structured as follows. In the next section I will reflect on the areas of intersection between intimate geopolitics and the geographies of making. Then the paper discusses the methods used in the research and considers the challenges that engaging creative subjects brings to political research. Following this, the analytical sections of the paper consider how the charity and its work situates bodies in different ways, emboldening some to take action, whilst constructing others as ‘in need’ or not. In this vein, the paper considers who the charity is really caring for, the ‘needy’ people it identifies, or the knitters donating their creations. It will conclude by reflecting on what the charity’s work achieves and what this means for scholarly intersections within the discipline.

First stitch: weaving intimate geopolitics with the geographies of making

Intimate geopolitics

Intimate geopolitics has aimed to rescale geopolitical study and move away from the idea of global and local scales as non-interacting and separate spheres. Rather, it aims to ‘dismantle the artificial scaling’ of the world (Pain, Citation2009, p. 467). As Christian et al. (Citation2016, p. 66) summarises, ‘feminist geopolitics argues that conventional approaches to geopolitics eclipsed that which was feminized private space, the local, everyday and routine experience, the body, and emotions from the realm of the (geo)political.’ That which had been previously deemed devoid of politics and power is now seen as wrapped into the global and equally shaping it (Pain, Citation2009).

Within this, Mountz and Hyndman (Citation2006, p. 447) explain, ‘the intimate encompasses not only entanglements rooted in the everyday, but also the subtlety of their interconnectedness to everyday intimacies in other places and times … ’. Equally, intimacy can lie within but also beyond family, friends and can even describe a closeness from not knowing someone at all. As Hall (Citation2019, p. 777) outlines in her work on austerity, ‘ … intimacy does not always equate to pseudo-familial relations resulting from domestic practices, whereby the spatial and relational dimensions of being or feeling close to others may result from unfamiliarity.’ Moreover, Berlant (Citation1998, pp. 281), considers intimacy to ‘ … involve an aspiration for a narrative about something shared, a story about oneself and others that will turn out in a particular way.’ In this context of making and donating objects, knitters may feel a closeness with bodies spatially distant from their own and tell their own story about what that object does for those bodies. As Valentine (Citation2008, p. 2105) emphasises, a richness can be added from thinking about wider conceptualisations of intimacy: ‘by focusing only on relationships in the domestic, we miss out on the complex web of intimate relationships that span different spaces and scales.’

This work demonstrates how layers and links, events and actions are wound together and simultaneously impacting one another. In Smith’s (Citation2012, p. 1517) discussions of love and babies in Leh in Ladakh, Kashmir, intimate geopolitics was found in the way the fertile potential of bodies became sites of territorial claim. What intimate geopolitics compels us to take seriously is the messiness of these bodies; their emotions, corporeality and relations, all of which are enrolled in processes of intimacy. As Fluri (Citation2011, p. 282) states, ‘bodies represent the most immediate and delicate scale of politics as corporeal sites and markers of gender and national identity.’ These bodies become impactful in the everyday work they do which in turn become entwined in global geopolitics.

The geographies of making

Geographers have become increasingly interested in the processes of making in recent years. As Hawkins and Price (Citation2018, p. 2) argue ‘making … [is] an embodied, material, relational and situated practice that spins connections between corporeal practices and formal institutional and political spaces.’ What this quote nicely highlights is the ability for making to do work across not only spaces, but between different kinds of bodies and affects. As has already been highlighted, intimate geopolitics is inherently interested in these kinds of interactions. Moreover, the process of assembling, making or creating by hand, has the ability to connect people, processes and things. As emphasized by Turney (Citation2012, p. 308) ‘the combination of touch and the knitted object, particularly when it is a gift, establishes a tactile relationship between the maker and intended recipient.’ Making, then, is a process that has generative power, but this power has not always been seen as political. Making is relational and situated; framed by the ideas of those making, their skills and abilities, creative choices, and motivations for doing it. There may be a particular goal or motivation driving them to make, or perhaps they simply get lost in the ‘doing’. There may be common ground in why makers make, but they each bring their distinctive combinations of experience and skill. The same method can produce inimitable results and no two pieces are alike. What distinguishes making from manufacturing is this ability to produce something unique rather than ‘a discrete, stable and segmented component of the contemporary economy’, therefore infusing it with different properties and values (Carr & Gibson, Citation2016). Atkinson (Citation2006a, p. 5) also describes the ‘democratizing agency’ that Do It Yourself activities, like knitting, provide. Within that, it is imperative to understand the motivations and imaginations of those doing the work and why people choose this method for trying to affect change in the world. This may not be the loudest form of activism, but it still provides a way for voices to be heard (Hackney, Citation2013). If the act of making is not without agency, then what is this agency doing, and who does it empower in ways that other means have failed?

Feminist researchers have called for a broadening of the concept of agency, for the ways it may invite less traditional forms of power into the critical eye (Flint, Citation2011). In order to do this work, we need to think beyond what currently counts as agency and whose actions count as political. Knitting, in particular, a craft with a feminized and domesticated history, provides the practice with radical potential. This is something that has been put to use in a myriad of forms, from the calls to knit socks for soldiers during World War Two, to its use in protest movements, such as the Pussyhat Project of the 2017 Women’s March. When we consider the generative power of knitting, we have to think about its historical ambivalences and geographies (Price, Citation2015). In this respect, this paper provides the new context of small-scale charitable knitting to the scholarly discussions around making and what happens when agency is sought through this means of action.

Points of intersection

With this in mind, there are two ways that the geographies of making and intimate geopolitics are able to cross-pollinate each other. The first is this joint attention to the body, its knowledge, the experiences it produces, and its prevalence as both a site and actor in different relationships of power. Both pay attention to similarly taken for granted sites, like the living room, garage or community centre, but the work done there aims to make impact in the world that spans beyond that space (Hawkins & Price, Citation2018). It is important not only to dwell on the space of the making, however, but the body of the maker. Hawkins and Price (Citation2018, p. 9) describe these bodies as ‘ … bodies that sense and are becoming skilled at sensing, through complex intersections of embodiment, materiality, matter, identity and skill, memory and habit.’ Moreover, as Carr & Gibson, Citation2016, p. 12) argue ‘focusing on making means being able to consider who is doing the making, as well as materials, their skilled manipulation, circulation, redeployment, and their agency, in the same breath across a much wider set of spaces and circumstances.’ In the work that they do, the maker body has impact. It becomes part of a tapestry of bigger relations, from the wider history and practices of that craft, or the global events which may spur it on.

The second area of potential engagement is within furthering the discussion of intimacy, and the ways in which connections can be made and facilitated through making. Intimacy can be about, and is often about, the building of connections. Gauntlett (Citation2011, p. 2) theorises that making is helpful in understanding this better. He says that making forms three different kinds of connections: (1) the connecting of one thing with another to make something new, (2) that process of making usually has a social dimension of meeting others to make, (3) the sharing of that made object in the world is an engagement with the world and an attempt to make a change in the social or physical environment. The argument made by Gauntlett is similar to the reflections of Hawkins and Price – the connections between corporeal, bodily practice and the practice of putting things together to make an object, can alter both its immediate surroundings and have wider impact in the world. These materials become a way of negotiating certain kinds of social and political relations and interactions (Price, Citation2015). Knitting although often solitary can be a connective act (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). Where Gauntlett’s focus could be taken further is in examining whether the process makes its intended connections successfully or not, and whether certain kinds of connections are stronger than others. What will be illustrated in the analysis section of this paper is how much messier this process is in reality, and the outcomes of these attempts at connection may be different than envisioned.

Neat rows and dropped stitches: methodological challenges in investigating charitable knitting

The methodology for this project had three broad strands; a volunteer ethnography, a set of interviews with volunteers and knitters, and learning to knit myself. Together these methods provided a rich understanding of charitable knitting within the organisation from the perspectives of the charity and its members. Yet, my time at the charity also required me to face up to some up to some of my own assumptions about the practice of charitable knitting versus what I learnt from volunteering there. For this reason, I have chosen not to name the charity this work is based on in order to not undermine the work they do and reflect more honestly on my experiences there.

I volunteered at the charity full-time for three weeks in 2017, following a three-day pilot period earlier in the year. Within my volunteer ethnography, as has been deliberated by Garthwaite (Citation2016, p. 67), the dual position of volunteer and ethnographer at the charity meant the boundaries of my roles became blurred. Other researchers have reflected on the dilemmas that arise from the duality of positions ethnography requires; from uncovering the power inequalities of charity work (Williams et al., Citation2016), to the ethical questions that working with social movements, even the insidious ones, can raise (Gillian & Pickerill, Citation2012). My research at the charity, similarly, required me to think ethically about the work I was doing and my position within it.

Autoethnographic accounts also became an important part of the methodology. I often found that many hours of my time as a volunteer would be spent alone, unpacking post, sorting knitted items or emailing those who had donated objects. Autoethnographic methods that engage the body recognise that the body of the researcher is deeply implicated and entangled at every stage (Atkinson, Citation2006b). Carr and Gibson (Citation20176b, pp. 11) write that autoethnographic methods prove particularly useful for those investigating the making process and have been vital to research in this field. In this instance, my body became a tool through which the banality of processes of the charity became known to me through the sensory knowledge produced in these solitary moments.

Beyond this, my positionality within the charity influenced the atmosphere that was created. It is important to acknowledge how the identity of the researcher and the relation they have to their research subjects influences the research (Rose, Citation1997). In this case, my identity as a woman became important as the charity was almost unanimously populated by women, with my presence continuing to construct a feminine space. Workspaces, as Warren (Citation2016, p. 49) argues ‘are key sites for the construction of gender subjectivities and power relations.’ Similarly, my gender seemed to grant me greater access and a legitimacy in the charity; as if my interest in knitting could be understood through my gender. In those moments, and throughout my time at the charity, the gendered history of knitting, became embodied within me as a female researcher with an interest in knitting. These moments undoubtedly shaped my experience at the charity.

During this time, I also conducted 15 interviews with members of the charity (volunteers and the charity’s founder) and knitters donating to it. All the interviewees (pseudonymized below) were white women and were aged between 30–80 years old. Volunteers often become involved in the charity whilst looking for volunteering opportunities post-retirement or as child-caring roles decreased. All were already knitters, and a handful had connections to the founder. Volunteering resulted in building rapport with charity volunteers, and all of those I met were happy to be interviewed. Knitting-donors were sampled by identifying groups who sent items earmarked for the refugee appeal. With the charity’s permission, I contacted their leaders and 3 knitting groups and around 3–5 knitters were happy to be interviewed from each group. Telephone interviews became both a necessity and a comfortable mode of contacting knitters as they were often based far away from the charity and of older generations. Quotes from telephone conversations can be identified by the use of italics without quote marks below. Throughout this methodology, each interview encounter became a way to intimately craft and co-create knowledge with the participants around charitable knitting. The process of interviewing is in itself intimate, but this was heightened from the ways in which interviews took place. From the comfort of the knitter’s homes and mine via our phone conversations, or in the knitting room of the charity in which the other volunteers and I would do our work alone, an atmosphere that allowed all kinds of conversations to occur as we sorted the knitting and felt it envelope us. Each interview felt like an intimate moment in which the interviewee would share their individual hopes, thoughts and even knitting tips with me. This in itself was always a partial process, where the knitters set out what they wanted from the practice of charitable knitting which often varied from person to person.

I found that learning to knit became an important part of my methodology in addressing the embodied nature of what the charity does and its material output. When I first came to the charity earlier in the year, I was struck at how consistently I was asked, ‘do you knit?’. The faces of those asking always fell when I answered with ‘no, I don’t knit’. It became clear that this was something I needed rectify on returning to the charity, as an important source of common ground with the volunteers I would be working with. This is similar to Squire’s (Citation2017, p. 6) reflections on being asked whether she dived, the consequent commonality of feeling that comes from physically experiencing that activity, to picking up the lexicon involved in it, was a legitimizing process within her research community. Carr and Gibson (Citation2017, pp. 5) describe how encounters with participants hang on this shared devotion to a craft or ultimately flops due to the gap between an unpractised eye and a skilled on. Knitting myself allowed me to feel and understand the knitted objects I was unpacking and sorting in a way only possible from having that visceral knowledge. I could identify stitches, complexity of pattern, the use of different wool or needles; things that became visible from learning myself. As Pinkerton and Benwell (Citation2014, p. 15) stress in their work on creative statecraft, ‘rarely has geopolitics been conceptualized as creative.’ Yet, this methodology highlights the importance of embracing creativity in all aspects of our research, be it in theme or method.

Discussion: examining the fabric

The maker’s body

The body of the maker is at the core of charitable knitting and the charity itself. It enrols bodies who can knit, stitch and make and puts them into contact with a network of people that can receive them. Hawkins and Price (Citation2018, p. 8) argue maker bodies are ‘ … bodies that are learning to do; bodies that are tired and strained; bodies that are repulsed, that are skilled, that are satisfied “in the flow”, that are passionate, that are privileged; that are being coerced, frustrated and damaged’. Reflecting on the inception of the charity, the founder, Sarah said:

‘ … Then somebody got to hear about it, I think first it was somebody in Canada that heard about it … and knitted and sent us hats for babies in Afghanistan. And then people contacted us and said look … we’re sending soldiers to Afghanistan; can’t we send these warm woolly jumpers and blankets for the children? And we thought, our policy at the organisation is to always encourage people if they want to help other people because if you say, no, that’s impractical, it knocks back a good motive.’

This quote is striking because the action described is seen to be deliberately parallel to violence, soldiers and formal state intervention, which sits in line with the overall anti-violent stance the organisation takes. In this, the associations knitting has, of taking place within domestic settings and made by a loving hand are deployed with the intent to be disruptive (Adamson, Citation2007). Further to this, the quote draws on the idea of encouraging or not holding back a ‘good motive’ no matter the idea or the method of charitable work. Within the organisation’s media, they state these donations go to over 200 destinations, from hospitals, to refugee camps, to food banks. Given the huge number of donations that I witnessed within my time at the charity, there is something that attracts people to this method. The image in shows the knitting room in which the majority of the charity’s work took place. It shows the encroaching numbers of bags filled with knitted items, categorised as shown in the boxes above. As the donations grew, the space we had to navigate the room become increasingly narrow and the room more inundated.

Figure 1. The room where most of the charity’s work is carried out which at times became flooded with more knitting than it was possible to find homes for. Author’s own.

The deep attraction that knitting has as a method for action was reflected in my interviews with knitters. Mabel, a knitter, describes the charity’s work in this way: ‘It’s heart-warming in a cold world … like chicken soup for the soul.’ The use particularly of the analogy of chicken soup, emphasises the kind of weight placed on each knitted object. Chicken soup is synonymous with the comforting effect the knitted object has on the knitter and the receiver, perceived to be acting against other kinds of injustice in the world outside of the individual’s control. Returning to the idea of intimacy, Moran and Disney (Citation2018, p. 180) theorise that comforting someone is an enabling circumstance for intimacy to exist. Comfort itself is deeply embodied (Bissell, Citation2008). It has effectual properties that resonates through objects and bodies (Price, Citation2015). Comfort wraps around bodies through the presence of comforting objects, but this also comes from the way they viscerally and emotionally move the body, much like a blanket, jumper or scarf can envelope their wearer.

Knitting can both bring joy to the knitter whilst honouring and uplifting the recipient (Greer, Citation2008). An act of connection at home from one body leads to a connection with both the world and another body elsewhere. This connection is felt to be personal, inviting the receiver of the object to feel warmed by the action that another has taken. This idea was reflected in some of the small additions that knitters made to their donations, which are further explained in interview responses. Knitter, Lorraine, and her knitting group stitched in labels in their knitted donations to let their receivers know who the object was from, as seen in the images below in .

Figure 2. Examples of labels or embellishments attached by knitters to communicate a message to those receiving the items. They include notes such as handmade with love, or the dove symbolising peace. These particular items were requested to be sent to refugees. Author’s own.

She said: ‘By letting people know there are other people at the end of the line … that impact spreads’. In this quote, the handmade and comforting properties of knitting affect the person who receives it and the impact this has on both maker and recipient radiates to the world around them. Knitting is often viewed with familiarity and comfort; conjuring an idyllic vision of grannies clicking needles in rocking chairs (Turney, Citation2012). Within this quote, the assumption is that comforting one person will produce a rippling effect of comfort, knitters being the initiators of a chain reaction.

This demonstrates a need to unpack knitting as clearly a loaded process that produces objects with particular qualities. A consistent theme in interviews was the idea of the value of knitting originating from its apolitical and non-monetary connotations, acting outside of those dominant global systems. This is demonstrated in an interview with volunteer, Dina, said: ‘No matter about the government policy, the charity knows that there are people in need and that is not acceptable.’ This a sentiment that is mirrored within my discussions with a knitter, Betty, went so far as to say that if the charity’s work was political, they wouldn’t do it. Lorraine felt that the power that knitting can have to intervene comes from the fact that it is non-monetary. The sentiments within these statements place value outside of traditional political power, looking for alternative methods to effect change in the world, away from systems they feel are unable to do this. Yet knitting is not an action that is devoid of power or worth. Craft, for example, can sometimes be described as ‘pre-capital’ for the ways in which it was previously viewed as having no market value compared to ‘high-culture art’ (Adamson, Citation2007). Beyond this, it is the time, effort and exertion that become another kind of capital in knitting, alongside its comforting properties. As Turney (Citation2012, p. 305) states about giving the gift of knitting, ‘to make an investment not merely of time … but of thought, consideration and contemplation of the intended recipient during the making process. This suggests the production and consumption of the knitted object are equally emotionally charged … ’. Significant hope is invested into these objects and the perceived outcome is felt to be worth the time it takes to make them.

Yet, this was clearly not the only aspect of this ‘good motive’ mentioned by Sarah, the founder of the charity. It became apparent that the reason why people choose knitting is beyond the impact it may have on the recipient. This is demonstrated well in this quote from our interview:

‘People would send us little notes when they sent us the knitting. What we found was that they were saying, ‘I’m so glad to be able to help someone, I’m happy to be able to knit, knitting keeps me happy, it’s the only thing I can do now I’m housebound, or we all get together in a knitting group because I’ve been widowed, it’s a great opportunity to go out.’

The charity helps these knitters by finding a home for the things that they so greatly want to make by providing a cause to knit for. Given the many benefits those knitting get out of the making process, it seems important for there to be a home for these objects to go and subsequently the knitters feel better as they feel they are making some kind of difference. It can produce a kind of imaginary agency in the world where these groups may otherwise feel diminished. Knitting can provide a sense of control (Corkhill et al., Citation2014). The charity provides knitters with someone to knit for, and someone who will be thankful for the object received. Moreover, it encourages people to create knitting groups, or otherwise a way of feeling connected to knitters across the country moved to make for the same cause. The knitters need to know these objects are being loved, that they are being homed by people who want and need them. As this piece from my ethnographic diary states:

‘Talking to another volunteer today, we were discussing why people send things. Talking about women growing up with these skills and then running out of people to knit for … making small things for children and grandchildren until there comes a point when they don’t want it anymore … then it becomes about trying to find something to do with it and someone who will want it … .’ (23/05/2017).

The bodies performing this rhythmic process, however, gain something from it, as I learned within my ethnographic work. This is a process described by Price (Citation2015, p. 84) as ‘an embodied, rhythmic and skilled practice that requires time, patience, and knowledge through the making with material.’ In this sense, knitting is a process which can create great enjoyment for the bodies doing it. These rhythmic qualities, shaped through the co-occurrence of movement and sound lead to almost a meditative effect (Turney, Citation2009). As Corkhill et al. (Citation2014, p. 39) nicely puts it, ‘knitting creates a strong, resilient, flexible fabric. Therapeutic knitting seeks to create strong, resilient, flexible minds in the process.’ For this reason, knitting has been praised for having all kinds of benefits for the knitter. It can help with a variety of problems, from the easing of chronic pain, relieving depression and improving mental wellbeing, and for preventing isolation and loneliness. For example, one of the groups I interviewed was formed with the aim of knitting for the charity. These are all benefits cited in the charity’s commission report into the positive effects of knitting. The maker body needs to make in order to get these benefits; the health benefits from performing the action, the intimacy made by making with another, for another, and warmth from feeling that the object produced from their labour will be needed and loved.

The imagined body

This section of the paper will discuss the geographical imaginations of those doing the knitting, whose body they imagine filling up the jumpers and hats they create, and what motivates them to take part in this process of making and donating. As was discussed above, knitted objects take time and energy to make, can be personalised and are imbued with emotions. Moreover, they are objects given alternative power and value. If the purpose of making is to give that creation away, it is evidently important who the recipient is and how they are imagined within the making process. Kuus (Citation2019, p. 168) argues that ‘today’s political geography explores politics especially through a close-up focus on everyday people, places, and things: on the quotidian lived experience in all of its ephemerality and ambiguity.’ Through this lens, the recipients of the objects and their bodies are of geopolitical interest; how can the process of knitting for certain bodies (re)construct ideas of who is in need?

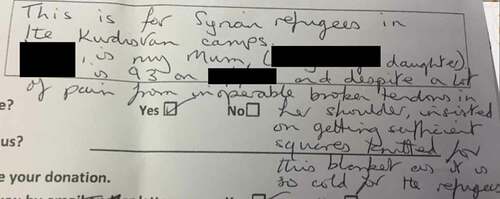

Whilst I was at the charity, the refugee appeal was a cause that captivated the hearts of those knitting and donating to the charity and became something that was referenced in the notes left with their knitting, for example, in the note pictured in .

Figure 3. A note received from a person donating their mother's knitting for refugees. The donor emphasises what it means to her Mum to be able to send these things to refugees to keep them warm. Author’s own.

These are the kinds of notes the charity received daily. Each provides a glimpse of who is imagined as in need of these objects, and the emotions attached to them. Geopolitical imaginations can be described as ‘a system of visualizing the world’, and one that is inherently constructed (Angew, Citation2003, p. 6). It can reflect atmospheres of collective feeling and dominant political narratives. To take this from an intimate viewpoint, where the scale of the body is valued as embedded in geopolitical relationships and processes (Dowler & Sharp, Citation2001), these imaginations shape how we think about other bodies. From the objects donated to the charity, it became clear that a certain kind of body had the power to evoke this outpouring of emotion and charitable spirit. There were certain bodies for which this connection was often meant for. Within charitable knitting, imaginations become manifest in another form. Every item that the knitter sends, the way they design it, the size they make, the shape and colour of the object, each of these choices becomes an expression of their imagination. They were designed for small bodies, children’s bodies.

These sentiments made visible in clothing, were verbalised in my interviews with knitters and volunteers. They would often reference the importance of caring for a child or small body. Volunteer, Louise said: ‘[in relation to refugees] … you know, you are destitute when you are out there and you see your kids so cold, it must be amazing … if somebody gives them a sweater.’ The emphasis of the quote lies in the idea of caring for a child and the appreciation of a child being cared for if their guardian is unable to do so. It is about making a difference, even if just to one child. Generally, the ‘child alone’ image is a media trope which has been timelessly used to generate humanitarian narratives and the training of ethical impulses in those that consume them (Fehrenbach & Rodogno, Citation2015). The child refugee has been an imagined body unforgettably imprinted onto the geopolitical imaginations of many following the images of Alan Kurdi’s motionless body lying on the Turkish coastline in 2015. It became an incredibly important moment within the refugee crisis in how it shaped imaginations about whose bodies require the most care. In this circumstance, it provided a figure on which these desires to comfort and take care could be attached, a renewed motivation to knit for.

When bigger bodies are involved, however, their need for care, comfort and affection is deeply scrutinised. In 2016, a group ofteenagers were granted asylum in the UK as child refugees and their claims were fiercely questioned because of their distinctly bigger bodies. Moreover, physical elements of their bodies were inspected and discussed to determine the legitimacy of this claim. Clearly then, certain bodies have the power to move and invite action on their behalf, whereas other bodies are cast with illegitimate need. Within the charity, care for bigger bodies was often similarly neglected:

‘Someone pointed out to me today that an awful lot of refugees are men. Yet, the majority of the stuff that we get is for kids … people always knit the stuff that they like, or using the pattern they like, like the fish and chip jumpers which no one really wants … makes me wonder when we send stuff out whether people like it or just think it’s a bit useless.’ (30/05/2017).

The design choices of the objects the charity received often meant they have no other possible recipient. As the number of children’s hats, jumpers and toys consistently grew from donations, we would struggle with the task of trying to match these donations with places that would take them. In one case, a charity sending donations to refugees said they simply did not need baby or children’s clothing as the majority service users were young male refugees. This disconnect between imagined need, whether refugee or not, child or adult, not only became evident in the items donated to the charity, but ultimately shaped and controlled the work they could do.

The process of categorisation of those who ‘counted’ as needy or not also became clear within my interviews. For example, in this quote a volunteer, Marie, said: ‘It’s important to send it to genuinely needy people. Then they don’t get wasted.’ The suggestion of an imagined classification of the ‘genuine’ needy person generates an imagined disingenuous or fraudulent needy person. A further hierarchy of need developed within my interviews with knitters. Knitter, Betty, said that they felt a homeless person would not appreciate their knitting as much as a refugee was likely to because they had not lost everything like a refugee has. The inference is that imagined exceptional circumstances, such as war, are required to produce ‘genuine’ need. As one of the main acceptors of donations, during my fieldwork at the charity, was UK foodbanks, these ideals of ‘need’ seem to be in conflict with the reality. This is not only revealing of the knitters and who they feel or imagine to be in need, but it controls the bodies that receive and wear that object when it reaches the charity and is sent out again. The items became a materialisation of their geopolitical imagination of where need exists, and which bodies they feel are in need.

Beyond these imaginations, the materiality of the object made not only reflects the whims of the knitter but constricts the usefulness of the garment given. The reality of this need is not in line with the knitters’ chosen method for attending to it. Considering the following quote from the charity founder, Sarah, she describes the process of her family rejecting her knitting on the basis that it is itchy and requires special care:

‘As soon as your grandchildren can say it’s itchy you’ve lost that as an option and I always remember my daughter coming up the garden path saying, keep it on until Grandma’s seen it. So, you know that it’s not going to be worn. And also, they think handwashing these days, they all treat it like you’re giving them a punishment.’

These are objects, made with time and love, but in reality, of a material that is delicate, difficult to care for and perhaps not enjoyable to wear. This further emphasised how much of the charity and its work was really about the knitter rather than the need they are supposedly attending to. The disparity between the bodies imagined to be needy and the reality is heightened by the material and object used in the process, an object likely to leave its recipient somewhat wanting. As Turney (Citation2009, p. 191) synthesises, ‘although there is no doubt that knitting for charity is formidable, sentimental and sometimes a necessary means of expressing support … [it acts in] communicating more about the knitter than the cause or the intended recipient(s).’ This demonstrates how much of the work done by the charity revolves around the knitters and their care, rather than those they knit for.

Casting off: rethinking charitable knitting

To conclude, the work done by the charity was all about bodies, both real and imagined. The charity provided a means for those knitting to feel like they have agency in the world whether or not their making fulfils the imagined future they have for it. This is done whilst encouraging them to use their skill and continue a hobby they enjoy. Yet, the objects they produce, their size, shape and colour, confines the work the charity can do. Each object became a representation of the geopolitical imaginations of their makers and who they felt needed caring for. This is particularly as the materiality of that object makes it inherently impractical and delicate.

The work the charity does in knitting and donating objects was about forging intimate connections of the kind described by Gauntlett (Citation2011), but these connections did not form in the way intended by those making. The reality is that it was far less about connecting knitters with recipients, and more about connecting knitters with one another. The charity convenes a community of knitters around this cause of making for others, that might otherwise never have formed. Giving knitters a motive to knit that warms their soul, caring for their donations, writing to them to say they have arrived, accepting their means of giving where few other places would, is all work the charity does to look after people and bring them together. In studying this subject and this charity, I had to confront that the work they do did not align with my own more idealistic construction of it. In actuality, I had to come to understand the real work the charity does and readjust my own way of imagining it. Moreover, it seems this is something the charity knows and understands as they try and fund another sack of children’s clothes to be shipped, or in carefully ensuring that every piece of knitting that comes in will go out again. The charity began by fulfilling the wants of knitters to send things to children in Afghanistan and continues to work in supporting knitters and their want to affect change using knitting.

The making that takes place, that the charity finds a home for, requires bodies and implicates others. The act of knitting is a method used by some to feel they are able to impact the world once their agency is diminished, and the objects made are political in the ways that they construct the bodies and imaginations of need. I invite other scholars to embrace the close connections between intimate geopolitics and the geographies of making, to investigate what other points of fertilization they can provide insight to.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Alasdair Pinkerton who initially supervising this work, and Katherine Brickell for her continued supervision. I would also like to acknowledge the help of Laura Price and Harriet Hawkins in advising on the work at its various stages.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ReferencesReferences

- Adamson, G. (2007). Thinking through craft. Berg.

- Angew, J. (2003). Geopolitics: Re-visioning world politics (2nd edn ed.). Routledge.

- Atkinson, P. (2006a). Introduction: do it yourself: democracy and design. Journal of Design History, 19(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epk001

- Atkinson, P. (2006b) Rescuing autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(4), 400–404

- Barabantseva, E., Ni Mhurchu, A., & Peterson, S. (2019). Introduction: Engaging geopolitics through the lens of the intimate. Geopolitics., 1-14. h ttp s://d oi-o rg. ezproxy01 .rhul .ac .uk /10 .1080 /1465 0045 .2019 .1636 558

- Berlant, L. (1998). Intimacy: A special issue. Critical Inquiry, 24(2), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1086/448875

- Bissell, D. (2008). Comfortable bodies: Sedentary affects. Environment & Planning A, 40(7), 1697–1712. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39380

- Brickell, K. (2012). Geopolitics of home. Geography Compass, 6(10), 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2012.00511.x

- Carr, C., & Gibson, C., . R. (2016). Geographies of making: Rethinking materials and skills for volatile futures. Faculty of Science - Papers, 2203

- Carr, C., & Gibson, C., . R. (2017). Animating geographies of making: Embodied slow scholarship for participant-researchers of making cultures and material work. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12317

- Christian, J., Dowler, L., & Cuomo, D. (2016). Fear, feminist geopolitics and the hot and banal. Political Geography, 54, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.06.003

- Corkhill, B., Hemmings, J., Maddock, A., & Riley, J. (2014). Knitting and well-being. Textile, 12(1), 34–57. https://doi.org/10.2752/175183514x13916051793433

- Dowler, L., & Sharp, J. (2001). A feminist geopolitics? Space and Polity, 5(3), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570120104382

- Fehrenbach, H., & Rodogno, D. (2015). ‘A horrific photo of a drowned Syrian child’: Humanitarian photography and NGO media strategies in historical perspective. International Review of the Red Cross, 97(900), 1121–1155. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1816383116000369

- Flint, C. (2011). Introduction to geopolitics (2nd edn ed.). Routledge.

- Fluri, J. L. (2011). Bodies, bombs and barricades: Geographies of conflict and civilian (in)security. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(2), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00422.x

- Garthwaite, K. (2016). The perfect fit? Being both volunteer and ethnographer in a UK foodbank. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 5(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-01-2015-0009

- Gauntlett, D. (2011). Making is Connecting. Polity Press.

- Gillian, K., & Pickerill, J. (2012). The difficult and hopeful ethics of research on, and with, social movements. Social Movement Studies, 11(2), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.664890

- Greer, B. (2008). Knitting for good. Trumpeter.

- Hackney, F. (2013). Quiet activism and the new amateur. Design and Culture: The Journal of the Design Studies Forum, 5(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.2752/175470813X13638640370733

- Hall, S. M. (2019). Everyday austerity: Towards relational geographies of family, friendship and intimacy. Progress in Human Geography, 43(5), 769–789. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518796280

- Hawkins, H., & Price, L. (2018). Towards the geographies of making: An introduction. In L. Price & H. Hawkins (Eds.), Geographies of making, craft and creativity (pp. 1–30). Routledge.

- Hyndman, J. (2010). Introduction: The feminist geopolitics of refugee migration. Gender, Place and Culture, 17(4), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2010.485835

- Kuus, M. (2019). Political geography I: Agency. Progress in Human Geography, 43(1), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517734337

- Moran, D., & Disney, T. (2018). ‘You’re all so close you might as well sit in a circle … ’ Carceral geographies of intimacy and comfort in the prison visiting room. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 100(3), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2018.1481725

- Mott, C., & Cockayne, D. (2017). Citation matters: Mobilizing the politics of citation toward a practice of ‘conscientious engagement. Gender, Place and Culture, 24(7), 954–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1339022

- Mountz, A., & Hyndman, J. (2006). Feminist approaches to the global intimate. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 34(1/2), 446–463. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40004773

- Pain, R. (2009). Globalised fear? Towards an emotional geopolitics. Progress in Human Geography, 33(4), 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508104994

- Pinkerton, A., & Benwell, M. (2014). Rethinking popular geopolitics in the Falklands/Malvinas sovereignty dispute: Creative diplomacy and citizen statecraft. Political Geography, 38, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.10.003

- Price, L. (2015). Knitting and the city. Geography Compass, 9(2), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12181

- Rose, G. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography, 21(3), 305–320. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297673302122

- Smith, S. (2012). Intimate geopolitics: Religion, marriage and reproductive bodies in Leh, Ladakh. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(6), 1511–1528. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.660391

- Smith, S. (2020). Political geography: A critical introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Squire, R. (2017). ‘Do you dive?’: Methodological considerations for engaging with ‘volume’. Geography Compass, 11(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12319

- Turney, J. (2009). The culture of knitting. Berg.

- Turney, J. (2012). Making love with needles: Knitted objects as signs of love? Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture, 10(3), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.2752/175183512X13505526963949

- Valentine, G. (2008). The ties that bind: Towards a geography of intimacy. Geography Compass, 2(6), 2097–2110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00158.x

- Warren, A. (2016). Crafting masculinities: Gender, culture and emotion at work in the surfboard industry. Gender, Place and Culture, 23(1), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.991702

- Williams, A., Cloke, P., May, J., & Goodwin, M. (2016). Contested space: The contradictory political dynamics of food and banking in the UK. Environment & Planning A, 48(11), 2291–2316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16658292