ABSTRACT

Gamification in digital design harnesses game-like elements to create rewarding and competitive systems that encourage desirable user behaviour by influencing users’ bodily actions and emotions. Recently, gamification has been integrated into platforms built to fix democratic problems such as boredom and disengagement in political participation. This paper draws on an ethnographic study of two such platforms – Decide Madrid and vTaiwan – to problematise the universal, techno-deterministic account of digital democracy. I argue that gamified democracy is frictional by nature, a concept borrowed from cultural and social geographies. Incorporating gamification into interface design does not inherently enhance the user’s enjoyment, motivation and engagement through controlling their behaviours. ‘Friction’ in the user experience includes various emotional predicaments and tactical exploitation by more advanced users. Frictional systems in the sphere of digital democracy are neither positive nor negative per se. While they may threaten systemic inclusivity or hinder users’ abilities to organise and implement policy changes, friction can also provide new impetus to advance democratic practices.

RÉSUMÉ

La gamificación en el diseño digital toma ventaja de elementos similares a los juegos para crear sistemas de gratificación y competencia que fomentan el comportamiento deseable del usuario al influir en sus acciones y emociones corporales. Recientemente, la gamificación se ha integrado en plataformas creadas para resolver problemas democráticos como el aburrimiento y la falta de compromiso en la participación política. Este artículo parte de un estudio etnográfico de dos de estas plataformas, Decide Madrid y vTaiwan, para problematizar la versión universal y tecno-determinista de la democracia digital. En este artículo, argumento que la democracia gamificada es de naturaleza friccional, un concepto tomado de las geografías culturales y sociales. La incorporación de la gamificación en el diseño de la interfaz no mejora inherentemente el disfrute, la motivación y el compromiso del usuario mediante el control de sus comportamientos. La ‘fricción’ en la experiencia del usuario incluye varios problemas emocionales y explotación táctica por parte de usuarios más avanzados. Los sistemas de fricción en el campo de la democracia digital no son per se ni positivos ni negativos. Si bien pueden amenazar la inclusión sistémica o dificultar la capacidad de los usuarios para organizar e implementar cambios de políticas, la fricción también puede proporcionar un nuevo impulso para promover prácticas democráticas.

RESUMEN

La ludification dans la conception numérique utilise des éléments de type ludique pour créer des systèmes gratifiants et compétitifs qui encouragent le comportement désiré de ses utilisateurs en influençant les actions et les émotions corporelles de ceux-ci. Récemment, la ludification a été intégrée dans des plateformes conçues pour corriger les problèmes que face la démocratie, tels que l’ennui et le désengagement envers la participation à la vie politique. Cet article s’appuie sur une étude ethnographique qui concerne deux de ces plateformes, Decide Madrid et vTaiwan, pour problématiser la description de la démocratie digitale en tant qu’universelle et techno-déterministe. Je soutiens que la démocratie ludifiée est de nature frictionnelle, un concept emprunté aux géographies culturelles et sociales. L’incorporation de la ludification dans la conception numérique n’améliore pas intrinsèquement le plaisir, la motivation et l’engagement de l’utilisateur par le contrôle de son comportement. La « friction » dans l’expérience de l’utilisateur comprend diverses situations émotionnelles et de l’exploitation tactique par des utilisateurs plus avertis. Les systèmes frictionnels dans le domaine de la cyberdémocratie ne sont ni positifs ni négatifs en soi. Bien qu’ils puissent menacer l’inclusion systémique ou limiter les capacités des utilisateurs pour organiser et implémenter des changements politiques, la friction peut aussi apporter un nouvel élan au progrès des pratiques démocratiques.

From digital democracy to gamified democracy

Digital democracy is widely defined as the use of an array of information and communications technologies (ICT) ‘for purposes of enhancing political democracy or the participation of citizens in democratic communication’ (Hacker & Van Dijk, Citation2000, p. 1). The notion of e-democracy, in its early development, was dominated by a techno-deterministic belief that ICT could reinvigorate the Habermasian public sphere and enhance deliberation (Chadwick, Citation2009; Loader, Citation1997). Many scholars of e-democracy have critically viewed such beliefs not only as normative and ‘one-size-fits-all’ accounts of digital democracy (failing to consider local and institutional complexity), but also as overemphasising the democratic potential of ICT (Chadwick, Citation2009; Hague & Loader, Citation1999; Loader & Mercea, Citation2011; Wright, Citation2011). In this regard, researchers have sought to uncover the real effects of e-democracy through empirical research which does not take techno-deterministic rhetoric at face value (Hague & Loader, Citation1999; Wright, Citation2011).

Many geographers approach digital democracy from the perspective of policy-making in the media/digital space (Barnett, Citation2003, Citation2004; Pallett, Citation2015), viewing popular culture as a mediator between technology and the public (Barnett, Citation2003) or foregrounding digital impacts on spatialities (Jackson & Valentine, Citation2014; Woods, Citation2020). However, recently, digital geographers (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018; Ash, Kitchin et al., Citation2018; Kinsley, Citation2014) have called on researchers to examine the impacts of human-technical relationalities – ‘what technology is and does in relation to “the human”’ (Kinsley, Citation2014, p. 371). This paper joins digital geographies with studies of e-democracy, which empirically examine the democratic effects of digital technologies by considering ‘how technologies are designed, exploited and adopted (or not) by humans’ in specific social-political contexts (Hague & Loader, Citation1999; Wright, Citation2011, p. 216).

Following this shared line of inquiry across digital geography and e-democracy studies, this paper examines two inter-related questions: 1) How do new digital platforms designed to facilitate democratic participation mediate the practices and experiences of their users via their gamified interfaces? 2) How can users’ experiences and practices with these systems help us rethink the role of gamified interfaces – and more specifically, their points of friction – in opening up or closing down new possibilities for digital democracy?

This paper draws on two relatively high-profile but under-researched platforms designed to facilitate digital democracy via gamification: vTaiwan and Decide Madrid. The platforms, each developed in 2015 by self-proclaimed ‘reform governments’ (Madrid City Council and the Taiwanese government), were greatly influenced by the culture of civic hacking and by wider social movements through which citizens, civic hackers, and activists made demands for ‘real’ democracy (15 M and the Sunflower Movement). Embedded within these particular cultural, social and political contexts, Decide Madrid and vTaiwan’s central purpose was to utilise new gamified solutions to tackle issues in Taiwanese and Spanish democracy such as distrust, low motivation, and disengagement. The app interfaces, which incorporate game elements (e.g., avatars, rules of competition and visual aid effects), claim to excite and motivate citizens to vote and comment on digital issues (vTaiwan) or propose and vote on participatory budgeting proposals (Decide Madrid). The two case studies offer insight into discussions about incorporating game elements into specially-designed digital interfaces and technologies to solve democratic problems (Lerner, Citation2014; Morozov, Citation2013). The gamified solutions of Decide Madrid and vTaiwan quickly became award-winning and widely distributed fixes for democracy, with vTaiwan being portrayed as a world exemplar for digital democracy (The Economist, Citation2019; The New York Times, Citation2019) and Decide Madrid winning the United Nations’ Public Service Award (The United Nation, Citation2018).

Drawing on six months ethnographic fieldwork, I argue that gamified democracy should not be framed as a universal and effective solution for democratic problems such as low motivation and disengagement in political participation. Rather, incorporating game-elements in the interface design produces various points of ‘friction’ – such as emotional predicaments and tactical exploitation – which emerge from unexpected encounters between interfaces and users in the localised process of digital political participation. This friction is double-edged: in one sense, it is seen as ‘practical, affective and emotional contestations between bodies and interfaces’ (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018, p. 1140) that undermine the inclusivity and equality of e-democracy. In another sense, as these contestations can undergo further development with user bodies and actions, friction can open new opportunities for democratic practice. In the sphere of digital democracy, friction is neither positive nor negative per se. Centring locally-produced friction(s) allows us to question the universal and technological-driven gamified solution of digital democracy. The existence of friction(s) re-problematises the techno-solutionist assumption that game-elements are capable of increasing users’ positive emotions and engagement in digital democracy.

This paper begins with a critique of the prevailing assumption of gamification-as-control, problematising this idea by considering the implications of frictions within the digital interface and beyond. It then reflects upon my ethnographic fieldwork, particularly on how frictions were observed and the importance of frictions in understanding the gamified interface. The paper then reviews how the interface designs of Decide Madrid and vTaiwan attempt to create a new, game-based solution for participatory democracy before challenging this notion by revealing various emotional and strategic forms of friction. I conclude with a discussion on whether these frictions can spark new democratic possibilities.

Going beyond gamification-as-control via the lens of friction

Gamification & game

Gamification is ‘an umbrella term for the use of video game elements (rather than full-fledged games) to improve user experience and user engagement in non-game services’ (Deterding et al., Citation2011, no page). Gamification has been a popular global phenomenon since 2011 when Google News introduced a badge-based rewarding system to turn news-reading into a game. Game elements are now applied widely to solve problems related to education, democracy, marketing, health care, smart cities and environmental sustainability (Morozov, Citation2013; Vanolo, Citation2018). The growth of gamification accompanied the expansion of smart phones and mobile apps, which allow access to various services via a digital interface (Morozov, Citation2013). Gamification is said to solve problems like low motivation, boredom, disengagement, and distrust (Hassan, Citation2017) and has proliferated as a tool for democratic participation – notable examples include participatory budgeting in Argentina and Canada (Lerner, Citation2014), urban planning in Finland (Thiel et al., Citation2016) and civic discussion of social issues in Nigeria (Fisher, Citation2020).

‘Game-based elements’, despite having no agreed-upon definition, are generally thought to include two characteristics: rule-based competition and incremental rewards building toward a specific goal (Bateman, Citation2018; Deterding et al., Citation2011; Lerner, Citation2014). Game-based elements imply the existence of direct or indirect competition, guided by rules on how users can compete (in groups or individually) with other users. During a rule-based competition, users are rewarded with points, badges or other incentives for completing designated tasks towards a clearly defined goal (Lerner, Citation2014; McGonical, Citation2011, p. 22). Some scholars argue that such game-based elements, which are designed to impose some control over users’ behaviour and emotions (usually to make them enjoy and engage with the process of competition), are central to the process of gamification (Bateman, Citation2018; Morozov, Citation2013). For Bateman (Citation2018, p. 1201), gamification ‘manag[es] contingency, construed in this context expressly as a challenge’. Gamification, in this telling, inevitably constrains the user’s autonomy by reducing the ‘possibilities for play into those already prescribed by those who made the game’ (Bateman, Citation2018, p. 1198).

Discussions on digital democracy and political participation often view gamification as a form of control. Scholars of participatory democracy argue that controlling contingencies through game mechanics reduces the high levels of user boredom, frustration, and disengagement while producing more empowered democratic processes (Hassan, Citation2017, p. 252; Lerner, Citation2014, p. 25). According to Lerner (Citation2014, p. 25), integrating features of game design and mechanics into democratic processes can empower users by ‘mak[ing] democratic participation more fun’ and ‘increasing citizen engagement and trust in democracy’. A good game design produces an ‘artificial conflict’ in which users (either individuals or groups) compete against each other based on predetermined rules (Lerner, Citation2014, p. 29). Game-based democracy, therefore, utilises certain design rules to lead and provoke users to become active and engaged, and to feel enjoyment and fun.

Geographers have explored the spatial and power practices made possible through various forms of games (e.g., sports games and videogames). They argue that such games unify or reinvent the nation-state via sport (Moser, Citation2010; Waitt, Citation2005), unleash (im)possible futures (Shaw & Sharp, Citation2013), and animate new spatial experiences (Ash, Citation2009). Geographers also refuse the reductionist framing of videogames as a space where relationships between users and videogame technologies are predetermined by game designs (Ash, Citation2009, Citation2015; Shaw & Sharp, Citation2013). Rather, videogames are understood to be open-ended environments/spaces of emergence, unfolding, and becoming as they are experienced by users (Ash, Citation2009, Citation2015; Shaw & Sharp, Citation2013). For Ash (Citation2015), designers of videogames have to manage and anticipate (but not completely control) contingencies. After all, unpredictable interplays between users and the gamified interface generate and encourage creative responses from players. However, a gaming environment that is too open might ‘fail to captivate and capture an audience or community of users at all’ (Ash, Citation2015, p. 668; also see, Vanolo, Citation2018).

Studies of gamification offer one view of digital democracy, but they tend to paint a rather linear and techno-solutionist picture. They assume that game-elements will effectively exert control over ‘undesirable’ user behaviours to create fun’, ‘engaging’, and ultimately ‘empowering’ ‘democratic’ experiences and actions. They ‘do not consider the impacts of various failures, glitches and contestations which come along with the package. We must avoid the assumption that ‘those who design such systems have complete control over what they do’ (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018, p. 1140). Geography and democratic studies have theorised the ‘failures, glitches and contestations’ that constitute ‘friction’.

Friction

‘Friction’ has been used by social and cultural geographers both as a concept and a metaphor to describe points of contestation and their effects (human and non-human or human-human) which either slow the effects of power in practice or create alternative power formations (Anderson, Citation2017; Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018; Perng & Kitchin, Citation2016; Rabbiosi, Citation2019). Tsing (Citation2005, p. 6), an anthropologist, first coined the term ‘friction’ to question ‘the smooth operation of global power’. Friction, emerging from ‘heterogeneous and unequal encounters’ in a particular locality, can ‘lead to new arrangements of culture and power’ (Tsing, Citation2005, p. 3). The concept fragments and variegates the singular and universal account of global capitalism; it foregrounds the lived encounters with different local terrains of regulations, social-cultural norms, and materialities.

Building on Tsing (Citation2005), many geographers have examined the double-edged and productive nature of friction, or as Rabbiosi (Citation2019, p. 6) puts it, how ‘people, ideas or objects move, creating glitches … [but] also producing ideas for future developments’. Friction, in this sense, is seen as either human mistakes/technological ‘glitches’ (Rose, Citation2016) or as a generative force produced by working through conflict or unexpected encounters between human actors (e.g., programmers, designers, citizens) and digital technologies or interfaces (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018; Leszczynski, Citation2019; Perng & Kitchin, Citation2016). Friction, seen either as glitches or human-digital contestations, can help to facilitate the creation of new formations of power and creative possibilities.

Many areas of geography, like digital urban innovation (Perng & Kitchin, Citation2016), digitally-mediated urban everyday life (Leszczynski, Citation2019), interface design and practice (Ash, Kitchin et al., Citation2018), and mobility studies (Cresswell, Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2014) understand friction as productive disruptions. The concept allows an alternative account of digital-human relationships – it challenges the linear, totalised, and techno-solutionist narratives of ‘clean interfaces and tightly controlled interactions’ (Karpp, Citation2011, p. ix).

Friction in democratic studies

The idea of more-than-human friction in geography runs parallel to the two different understandings of friction in democratic studies. One view, mainly associated with French scholars of radical democracy, sees friction as productive while theorists of participatory democracy view friction as unproductive. For scholars of radical democracy, democracy is the existence of conflict, disagreement or disruption generated by ‘the people’ against existing powers. This conflict is called ‘politics’ (Ranciere, Citation1998) or ‘the political’ (Mouffe, Citation2005) and its struggle is against the entity holding power, termed ‘the police’. For Rancière (1998, p. 99–100), democracy is ‘a singular disruption’ of policed bodies, communities, and powers – it is achieved through ‘the people’s’ actions and accounts for those who do not count. The appearance of ‘the people’ – unified beyond ethnic categories, identities, political parties, or the sum of the population – disrupts these orders in the name of freedom and equality. Disruption is productive: ‘the people’, by disagreeing, disturbing, and confronting police orders, configure and create a specific space for (democratic) politics to take place (Rancière et al., Citation2001).

In contrast, scholars of participatory democracy, such as Benjamin Barber, David Miller, and Jane Mansbridge (all of whom were deeply influenced by Jürgen Habermas), have a more negative view of disruption. As Young (Citation2000, pp. 47–49) notes, while these scholars never explicitly regard deliberation as a practice of following specific norms and rules, they draw on a narrow idea of democracy. In this view, democratic deliberation can only generate consensus when it operates using a strictly defined agenda with well-prepared and highly rationalised statements. Forms of disruption to orderly routines and deliberation, like dissent and street protests, are viewed as threats to a rational and good deliberative democracy (Mouffe, Citation1999; Young, Citation2000, p. 49).

This fundamental disagreement between the two schools of democratic thought offers a rather binary understanding of the unproductive/productive relationship between disruption and democracy. Incorporating the idea of friction from geography and democratic studies has the potential to create a cross-disciplinary analytical lens for examining gamified democracy. My use of friction does not assume a dichotomy of good/bad democracy; friction is contextually shaped by ‘any engagement with an interface’ (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018, p. 1140; Rose, Citation2016). I use the lens of friction to re-problematise gamified democracy – it is not an effective and universal solution that smooths over undesirable user behaviours, but rather a site of emotional contestation, tactical exploitation, and democratic innovation.

Ethnographies of digital gamification

Ethnographic methods, particularly participatory observations and interviews, are common and effective ways to study digital design and user interfaces (Ash Anderson et al., Citation2018). As Kitchin (Citation2017, pp. 24–26) states, ethnographic studies of a digital design team can shed light on the rationales of design practices and what such practices might mean in the wider social, cultural and political context. Such methods address key concerns of e-democracy scholars like Wright and Street (Citation2007) and Chadwick (Citation2009), who understand the digital interface to be the primary space for (not) enabling participatory actions and user experiences. Ethnographic methods also allow a trans-territorial, yet locally situated, account of how gamification affects democratic practices across digital/physical spaces, and across the political and social places of Madrid and Taipei. By focusing on interface design and user experience, I de-emphasise (but am aware of) other important aspects of digital democracy, such as urban places and politics (Tseng, Citationforthcoming; Woods, Citation2020), digital infrastructure, and cybersecurity.

Participatory observation allowed me to navigate the rapidly-changing, fast-paced, and fluid practices of digital design and gamified interfaces taking place within the distinctive political culture of civic hacking in Taipei and Madrid. Activists and civic hackers had recently gained political power and developed platforms using game-elements for democratic solutions. I was embedded within the Decide Madrid and vTaiwan teams as an intern and a researcher between September 2017 and March 2018. I immersed myself into everyday flows and politics of designing and using the gamified interface; this placed me in a position where I could wait for contestations to emerge and develop unexpectedly. I shadowed key policymakers for Decide Madrid, sitting through various meetings, public events and informal chats in office corridors, cafés, and pubs. In Taiwan, I regularly visited the digital office of the Taiwanese government, where I participated in 30 meetings, events, and discussions about digital democracy and vTaiwan. As I ‘lived with’ these informal/formal events and chats, a dynamic picture of the encounters between users, programmers, and gamified interfaces began to unfold.

I conducted 60 interviews with users, policymakers, and researchers involved in Decide Madrid and vTaiwan to understand how gamified interfaces mediated between users’ bodily movements, feelings and spoken words, along with their political concerns and the digital design practices. In Madrid, I conducted interviews with former and current programmers and policymakers to understand the design practices of Decide Madrid’s interface. I also observed ten users of different ages, genders and walks of life take part in a usability test carried out by Torresburriel Estudio for Decide Madrid. In Taipei, I interviewed Taiwanese policymakers and users about their perceptions and use of vTaiwan’s interface design. I also interviewed programmers from the US-based company Pol.is, the third-party supplier of vTaiwan’s software.

I encountered many challenges – including unequal power relationships, language differences and accessibility – while conducting interviews with Taiwanese and Spanish practitioners and users. To circumvent these challenges, I strategically harnessed my multi-positionality as a Taiwanese researcher who was studying in the UK and doing an internship in the Spanish and Taiwanese governments to better negotiate with different actors (Tseng, Citation2021). In Madrid, I leaned on whichever positionality (e.g., the credentials from a British university and the internship with the two governments) that made the potential interviewees feel closer to my research (despite the fact that I ‘looked’ and ‘sounded’ differently from what they were used to). This strategy increased people’s interest in my research. Spanish colleagues were often kind enough to serve as translators for those who did not speak English and willingly shared important resources (e.g., usability reports) with me. In Taiwan, I deployed the same strategy to mitigate power and cultural hierarchies within the Taiwanese government. This helped me alleviate the unequal power relationships between the political elites and myself and made them comfortable enough to discuss the digital design and its potential issues. To keep my ethnographic practices as ethical as possible, I took an ‘overt’ (Cook, Citation2005) approach and made my multi-positionality clear to the practitioners in Taipei and Madrid. I foregrounded the academic purpose of my research to pre-empt any concerns that I might pose a threat to Spanish or Taiwanese elites.

Gamification as a new techno-solution for digital democracy

Decide Madrid and vTaiwan are positioned as textbook examples of ‘technological solutionism’ (Morozov, Citation2013, p. 5), the idea that new digital technologies can reframe any social, political and economic issues ‘as neatly defined problems with definite, computable solutions’. In particular, Decide Madrid and vTaiwan integrated game elements into their interface design to address various democratic problems like low motivation and disengagement in democratic participation (Gastil & Richards, Citation2017; Lerner, Citation2014), online ‘trolling’ (irritating other players), and polarisation caused by social media (Simon et al., Citation2017). Decide Madrid has been called a ‘scalable software solution’ for e-participation (López, Citation2016), while the Digital Minister of Taiwan, Audrey Tang, believes that vTaiwan ‘remains one of the best ways to improve participation’ as its machine learning algorithms can tease out ‘common ground … creating consensus, not division’ (The New York Times, Citation2019). Clearly, gamification ‘has already become a favourite trick in the solutionist tool kit’ (Morozov, Citation2013, p. 298) for e-democracy.

By design, vTaiwan’s digital interface includes specific engagement tools – such as an avatar and generated artificial conflicts – which are deployed to make digital political participation, which is often perceived as boring and serious, into something fun, engaging and reflexive. By visualising each participant as a moving avatar, vTaiwan’s interface provides ‘motivational affordance’ (Hassan, Citation2017, p. 249) to prompt users to cast more votes or comments. Participants can easily see their moveable avatar’s position as it either remains within an Opinion Group or moves into another based on how the user responds to comments. This click-movement correspondence creates a rewarding feedback loop (Lerner, Citation2014) for participants. The more users want to see which Opinion Group they belong to, the more they are incentivised to cast votes on the interface.

Chandler, a software engineer for Pol.is Inc., explained that depicting participants as avatars is a classic engagement tool to motivate people to cast more votes:

Putting people’s images in there … went from people being able to get it when you took a minute to explain it to them to people just instantly voting on a few comments … they see their twitter images showing up and [they say] ‘that’s where I am in the conversation and where the [other] people are …Footnote1’

The second element of gamification, Lerner’s (Citation2014) creation of ‘artificial conflicts’, is produced through the purposeful visual display of (different) Opinion Groups on the user interface. The interface visualises how many users support and oppose each Opinion Group, positioning users in conflictual positions. The design is supposed to ‘nudge’ participants to explore and reflect on the opposite group’s opinions (for each issue under discussion). By singling out and visualising different voices from various Opinion Groups, vTaiwan’s interface design makes it possible to ‘listen to lots of people and really digest and synthesise what it is they are thinking and saying’ (interview with ChandlerFootnote2). These methods are different from a traditional online forum, which only rewards the most ‘liked’ opinion (Simon et al., Citation2017, p. 41).

Decide Madrid’s design interface follows a similar logic of gamification. However, it establishes a set of rules and emphasises ‘competition’ amongst participants over generating a consensus (Lerner, Citation2014). From e-petitions to a participatory budget process funded by a significant chunk of public revenue (100 million euro), Decide Madrid’s participatory processes are structured by fairly complicated goal-oriented rules.

To produce a successful proposal within the Decide Madrid participatory budget process, a user must follow a variety of rules about when and how they can propose/improve an idea, when they can vote on ideas, and how much support (positive votes) their ideas need to receive. Users can only propose their ideas within a specific period of the year (e.g., 12 November 2018–6 January 2019) and their ideas must achieve a minimum-support threshold (usually a proposal must receive 50% more support than other proposals) within two weeks (3 June 2019–30 June 2019) and fit various legal and financial criteria. Then, the idea must receive a majority of votes within another specifically designated time period (3 June 2019–30 June 2019). Only those proposals that comply with the rules and receive enough votes will be ‘winners’ – rewarded with money and administrative resources from Madrid City Council.

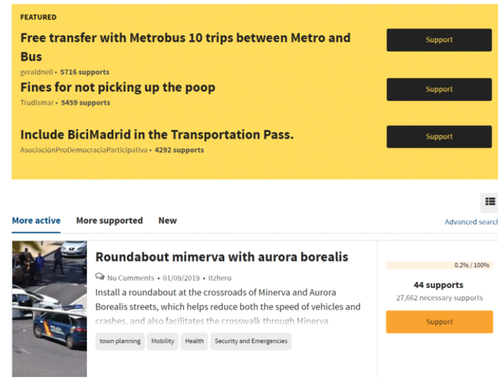

The intensity of the competition is reinforced with visual aids to hold users’ attention as they participate in the e-petition process (Lerner, Citation2014, p. 72). A yellow banner (see, ) highlights (and rewards) the three most voted-upon proposals at the top of the e-petition section. Participants are either expected to engage with the most voted proposals or to obtain more votes for their own proposals. Mike, a policymaker at Decide Madrid, explains that when the interface design tidies up ‘noise in the platform’ – the many proposals which are slightly popular, new, or not currently popular – it focuses participants’ attention on ‘the most interesting proposals and make[s] them win’. Decide Madrid’s interface design has attempted to reframe the process of e-petitioning as an intense competition, in which each participant’s attention and action is channelled to elevate ‘winner’ proposals over the ‘losers’.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the proposals highlighted in the yellow banner on Decide Madrid. (source: https://decide.madrid.es/proposals, access at 01/09/2019).

One danger of using a gamed-based approach to fix democracy – as Morozov (Citation2013, p. 5) warns – is that it can easily lead to ‘unexpected consequences that could eventually cause more damage than the problems they seek to address’. The various frictions within a gamified user interface could potentially facilitate such a situation. What follows is a description of the friction-rich reality of gamified democracy to disrupt the simple narratives of gamification-as-control, in which participants enjoy and actively engage with whatever rules are established for participatory democratic processes.

Friction as sites of emotional predicaments

Though scholars of gamification claim that game-elements allow participants to have fun and feel motivated and engaged (Lerner, Citation2014), participants of vTaiwan and Decide Madrid often experienced otherwise. Many participants encountered emotional forms of friction and experienced frustration, confusion, or disengagement when they were not able to adequately process information displayed on the digital interface. As Rose (Citation2016) notes, frictions are sites of practical and emotional contestation in user-interface relationships. Emotional predicaments are an unavoidable part of gamified participation, and the digital interface sometimes loses control of participants’ emotions and behaviour.

During Decide Madrid’s usability test, several users – including an elderly man and a middle-aged woman – struggled to create a participatory budgeting proposal. They struggled to navigate the interface, going back and forth, and constantly hesitating. Movements of pause and hesitation as users attempted to interact with the interface filled up silent moments in the usability test. Users were clearly confused and frustrated as they struggled to find the place to write a participatory budgeting proposal. After diligently attempting to use the app for about five minutes, six of the ten participants could not differentiate between an e-petition proposal (‘una propuesta’) and a participatory budget project (‘un proyecto para los nuevos presupuestos participativos’). Decide Madrid’s interface design did not ease the citizen-participants’ frustrations and often failed to facilitate participatory actions. To avoid emotional stress, users disengaged from the process of digital political participation. Emotional friction effectively ‘stifled’ the participatory budget process (Saulière et al., Citation2018) – in 2016 and 2017, fewer than 1% of all participants wrote proposals for the participatory budget process (Saulière et al., Citation2018, pp. 10–11).

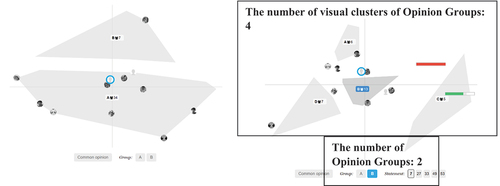

vTaiwan’s system was much easier to navigate; however, participants were still confused when they encountered unexpected and inconsistent visualisations stemming from ‘glitches’ in the digital interface. During a public consultation on ‘Opening Up Data in the Public Sector’, I noticed glitchy information on vTaiwan’s interface. Key information regarding the number of opinion groups underwent dramatic changes throughout the day. At 12:00 on 7 November 2018, there were only two opinion groups, A and B. Opinion Group A thought that governments should establish new regulations to increase citizens’ access to their open database and Opinion Group B wanted the Taiwanese government to improve the management and assessment of its open database by establishing a consultancy team (see, , left diagram).

Figure 2. vTaiwan’s interface at 12:00 (left); a glitchy moment in vTaiwan’s interface at 14:46 (right), 7 November 2019 (Source: https://polis.pdis.nat.gov.tw/5nckzdszrc, assess at 07/11/2019).

By 14:47, the digital interface visualisation was displaying four – not two – Opinion Groups (as indicated in ). shows the striking difference between the number of opinion groups indicated in visualised clusters (4: A, B, C, D) and the number of those indicated in the section next to common opinions (2: A, B). This meant that citizen-participants were shown inconsistent information, depending on when they logged in. Many citizen-participants reported that they were aware of this strange visual configuration and incoherent information regarding the Open Data consultation. These glitches emerged whenever there was ‘extreme’ engagement with the interface, for example, when multiple comments from different users were submitted in a short period of time or when a user voted ‘yes’ on multiple comments. Here, friction manifested as a glitch, a disruption to the visualisation and distribution of information, which plays a vital role in e-democracy by informing users about the issues under consultation (Hague & Loader, Citation1999). Friction-as-glitch in this process causes users to pause, hesitate and disengage. As Ash, Anderson, et al. (Citation2018, p. 1140) note, emotional friction – users’ frustration and confusion – are fundamental components of these two gamified interfaces.

Tactical friction by networked and knowledgeable citizens

Tactical friction is caused by knowledge asymmetries between participants. This type of friction is usually exploited at specific points within the participation process, like commenting and voting, in both Decide Madrid and vTaiwan. Participants can strategically exploit the rules of the game to gain more visibility and political clout for their positions at the expense of others with less knowledge. Participants use social media (e.g., Twitter) and offline networks, such as their cultural and social communities, to mobilise other like-minded users to participate in Decide Madrid and vTaiwan. While some researchers show that ‘clever’ users can transform technical glitches into creative outputs (Karpp, Citation2011; Leszczynski, Citation2019), the existence of tactical friction had harmful implications for digital democracy. Tactical friction facilitates unequal and less-inclusive processes of participatory democracy in which the majority of participants are not given the same consideration as privileged, middle-class citizens with knowledge and networks (Hague & Loader, Citation1999; Loader & Mercea, Citation2011).

In Decide Madrid, proposals written and submitted by users who are embedded within collectives (e.g., NGOs, local forums, or associations) are more likely to receive support and win project funding from the participatory budget (Decide Madrid, Citationn.d.). Paul, a Decide Madrid programmer, considers that understanding the numerical logic through which the digital interface operates makes a significant difference in how likely a proposal is to be seen and voted on:

If people do not understand how they [interfaces] work, some people will be able to make a profit out of them and some people will not … like knowing how many votes you have to receive per day to keep your proposal at the top … .and how to use marketing campaigns to maximise it, some people know how to do this and some don’t … .Footnote3

During the voting stage, specific groups of usersFootnote4 can leverage their greater knowledge and ability to access wider networks of support to help their proposals dominate in the hierarchy. Active Decide Madrid users can mobilise other citizens via social media (Saulière et al., Citation2018) and through offline channels. For example, a group of parents successfully promoted a proposal to create a rugby field by leveraging their offline/online parental community.

Like with Decide Madrid, vTaiwan participants – including civic hackers and active-minded citizens – exerted hegemony over participatory processes by leveraging their specific knowledge of the operative rules of the interface and their political networks. Detailed knowledge of how the interface prioritises political opinions allowed participants to make their voices heard, mobilise their political-social networks, and influence political decisions at the expense of other opinions. Gwen, a vTaiwan participant, who was also a contract worker for a government institution, explained how she wrote very clear and broadly agreeable comments to maximise her chance of attracting votes and gaining valuable supportive comments.Footnote5 Participants like Gwen have an advantage in e-democratic processes because they can make the interface work in their interest, at the expense of other less-knowledgeable participants. While vTaiwan is said to represent the views of ‘the public’, in practice, it is dominated by a small number of well-educated and politically-networked citizens. Gwen notes that often, when there is a lack of participants, the so-called ‘public’ is simply a collection of elite friends:

I feel some part of vTaiwan does not fulfil the claims that we made, well, for example, we said about the public and the community, but there are not many people there … we did not give vTaiwan to anyone … . this is why sometimes there are not many people attending to the participation … Footnote6

The existence of tactical friction indicates that Decide Madrid and vTaiwan, despite incorporating new game-elements in their participatory process, have recreated the old problems with digital democracy – the tendency of participatory processes to be influenced by the same group of participants (Bright et al., Citation2020; Hague & Loader, Citation1999; Wright, Citation2012). Groups of highly-networked citizens exploit game rules and mobilise online/offline networks, jeopardising the gamified technologies’ ability to equally and inclusively empower citizens (Lerner, Citation2014, p. 21–22).

Discussion: friction for engendering democratic moments

In this section, I seek to move the discussion of friction beyond the dichotomy of being good/bad for democracy by exploring how tactical friction can engender positive transformations in democratic politics via new, hybrid digital-human practices of care. Such hybrid and cultural practices of care enable Rancière’s (1998, pp. 18, 28, 99–100) vision of democracy as the disruption of dominant political-social orders by ‘the people’. A gamified democracy must embrace positive frictional effects by creating cultural spaces where care and concern for the disadvantaged, the forgotten, and the marginalised can proliferate.

The case of Decide Madrid reveals that cultural practices of care on digital platforms – rooted in place and society – can foster more inclusive democratic practices (but also inhibit them). The democratic utility of friction became visible when dominant users exploited the rules of the game and activated their digital and social networks to advocate for the disadvantaged. Participants, especially from NGOs and other social groups, leveraged their knowledge of digital/social campaigning to reorient the democratic process to serve those who were physically, financially or socially excluded (e.g., low-income residents, Alzheimer patients, the homeless and victims of domestic or animal abuse; Decide Madrid, Citationn.d.). The agentive power of hybrid digital-human encounters indicates a positive friction and pushes us to rethink Rancière’s understanding of democracy as strictly driven by ‘the people’. Participants cracked open the participatory process to help the vulnerable by forging alliances with digital technologies, both in the gamified interface and on wider platforms. Unlike Rancière (1998), who understands democracy as the moment hegemonic orders are broken down, the participants did not tear apart the rules of gamification. Rather, they worked around these rules to advocate for others.

The cultural and hybrid practices of care resulting in positive friction were more evident in Decide Madrid. It is rooted in the anarchist culture of Spanish autonomous movements, which have a long history and a strong ethos of claiming rights for subaltern groups (Fominaya, Citation2009; Juris, Citation2012). In contrast, vTaiwan’s participants and practitioners were generally elite politicians and civic hackers who emphasised a meritocratic cultural practice over care. In vTaiwan, attention was more focused on talented and highly educated netizens’ interests (e.g., discussing the legal and regulative aspects of sharing and platform economies) than on opening the participatory process to address the needs of the socio-economically and politically marginalised.

Conclusion: moving forward with friction

This paper examines the impacts of gamified technologies on digital democracy through the lens of cultural and social geography. The concept of friction challenges mainstream accounts of gamified democracy that assume game-elements offer quick, innovative, and universal techno-solutions to democratic problems. Instead, I argue that gamified democracy is frictional by nature. Participatory processes via gamified interfaces are saturated with uneasy encounters in which users feel frustrated or confused by the complicated rules of competition (friction as points of emotional predicament), and where specific groups of users can utilise their advanced knowledge of the rules and their networks to manipulate ‘the game’ (friction as points of tactical exploitation). This paper accounts for the unexpected and contested encounters between participants and gamified interfaces that not only challenge the notion of gamification-as-control but also open and close democratic possibilities.

While some frictions are glitches and unpleasant encounters, other (positive) frictions can foster democratic moments for the vulnerable and marginalised. Geography and democratic studies should build on this insight to further discuss how different forms of friction can engender new forms of democratic politics. Friction in gamified democracy as not simply good or bad. Rather, it oscillates between vulnerability and possibility until hybrid digital/human agency resolves the friction in one way or the other. The emergence of these more-than-human frictions in gamification requires us to rethink human-oriented democratic politics (Ranciere, Citation1998) and reassess what or who produces a more socially inclusive democracy. This discussion also refines Tsing’s (Citation2005, p. 93) use of friction to illustrate the fragility, new hopes, and nightmares of global capitalism within the context of digital gamification and democracy.

The persistence of locally-generated friction(s) reminds us that we cannot assume ‘power will transfer to the demos once they are armed with ICTs’ (Hague & Loader, Citation1999). Practitioners and researchers should pay attention to the social and cultural spaces and places where some friction(s) flourish into democratic politics. After all, the different cultural and social practices of vTaiwan and Decide Madrid’s user-communities have major implications. When friction is directed towards democratic politics, practices of care can address the needs of the underrepresented and marginalised through gamified democracy.

Future research should continue to innovate and strengthen (existing) discussions about friction in the fields of gamification, geography, and democracy studies. We must acknowledge friction as inherent to digital participation while also foregrounding how social and cultural places and practices reconfigure friction into democratic moments and spaces. Which specific cultural and social practices (e.g., care, empathy and fantasy) translate emotional and tactical frictions afforded by digital gamification into new forms of democratic politics to address marginalised, racialised and gendered life? Furthermore, how can comparing cases of gamification across social, cultural and political spaces and places help us to further unpack the relationships between friction and digital democracy?

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to three anonymous reviewers and editors for their comments. I thank Minna Ruckenstein and Sarah Hughes for their feedback and support on the earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Interview on 15/10/2018.

2. Interview on 15/10/2018.

3. Interview on 15/12/2017.

4. Examples of collectives include local forums for the official 21 districts in Madrid City (the more active ones being Chamberi, Salamanca and Hortaleza) and various single-issue interest groups (such as Rabbit Rescue Spain, Association against Light Pollution).

5. Interview conducted on 28/06/2018.

6. Interview conducted on 28/06/2018.

References

- Anderson, B. (2017). Cultural geography 1 : Intensities and forms of power. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 501–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516649491

- Ash, J. (2009). Emerging spatialities of the screen : Video games and the reconfiguration of spatial awareness. Environment & Planning A, 41(9), 2105–2125. https://doi.org/10.1068/a41250

- Ash, J. (2015). Technology and affect : Towards a theory of inorganically organised objects. Emotion, Space and Society, 14 , 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.12.017

- Ash, J., Anderson, B., Gordon, R., & Langley, P. (2018). Digital interface design and power: Friction, threshold, transition. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 36(6), 1136–1153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818767426

- Ash, J., Kitchin, R., & Leszczynski, A. (2018). Digital turn, digital geographies? Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516664800

- Barnett, C. (2003). Culture and democracy: Media, space and representation. Edinburgh University Press.

- Barnett, C. (2004). Media, democracy and representation: Disembodying the public. In C. Barnett & M. Low (Eds.), Spaces of democracy : Geographical perspectives on citizenship, participation and representation. SAGE. 185–206 .

- Bateman, C. (2018). Playing work, or gamification as stultification. Information, Communication & Society, 21(9), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1450435

- Bright, J., Bermudez, S., Pilet, J. B., & Soubiran, T. (2020). Power users in online democracy: Their origins and impact. Information Communication and Society, 23(13), 1838–1853. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1621920

- Chadwick, A. (2009). Web 2.0 : New challenges for the study of E-Democracy in an Era of informational exuberance. Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, 5(1), 9–41. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9006.003.0005

- Cook, I. (2005). Participant observation. In R. Flowerdew & D. Martin (Eds.), Methods in geography: A guide for students doing a research project (2nd ed., pp. 167–188). Pearson Education.

- Cresswell, T. (2010). Towards a politics of mobility. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 28(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11407

- Cresswell, T. (2012). Mobilities II: Still. Progress in Human Geography, 36(5), 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511423349

- Cresswell, T. (2014). Mobilities III: Moving on. Progress in Human Geography, 38(5), 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514530316

- Decide Madrid. (n.d.). DecideMadrid. from https://decide.madrid.es/presupuestos-participativos-resultados

- Deterding, S., O’Hara, K., Sicart, M., Dixon, D., & Nacke, L. (2011). Gamification: Using game design elements in non-gaming contexts. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. Association for Computing Machinery. January, 2425–2428. https://doi.org/10.1145/1979742.1979575

- The Economist. (2019). Inside Taiwan’s new digital democracy. The Economist. from https://www.economist.com/open-future/2019/03/12/inside-taiwans-new-digital-democracy

- Fisher, J. (2020). Digital games, developing democracies, and civic engagement: A study of games in Kenya and Nigeria. Media, Culture and Society, 42(7–8), 1309–1325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720914030

- Fominaya, C. F. (2009). Autonomous Movements and the Institutional Left : Two Approaches in Tension in Madrid ’ s Anti-globalization Network. South European Society & Politics, 12(3), 335–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608740701495202

- Gastil, J., & Richards, R. C. (2017). Embracing digital democracy. PS, Political Science & Politics, 50(3), 758–763. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096517000555

- Hacker, K. L., & Van Dijk, J. (2000). What is digital democracy ? In K. L. Hacker & J. Van Dijk (Eds.), Digital democracy (pp. 1–9). Sage.

- Hague, B., & Loader, B. (1999). Digital democracy: Discourse and decision making in the information age. Routledge.

- Hassan, L. (2017). Governments should play games: Towards a framework for the gamification of civic engagement platforms. Simulation & Gaming, 48(2), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116683581

- Jackson, L., & Valentine, G. (2014). Emotion and politics in a mediated public sphere : Questioning democracy, responsibility and ethics in a computer mediated world. Geoforum, 52 (0) , 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.008

- Juris, J. (2012). Reflections on #Occupy Everywhere: Social media, public space, and emerging logics of aggregation. American Anthropological Association, 39(2), 259–279.

- Karpp, P. (2011). Noise channels : Glitch and error in digital culture. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kinsley, S. (2014). The matter of “virtual” geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513506270

- Kitchin, R. (2017). Thinking critically about and researching algorithms. Journal Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1154087

- Lerner, J. (2014). Making democracy fun: How game design can empower citizens and transform politics. MIT Press.

- Leszczynski, A. (2019). Glitchy vignettes of platform urbanism. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 38(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819878721

- Loader, B. D. (1997). The governance of cyberspace. Routledge.

- Loader, B. D., & Mercea, D. (2011). Introduction networking democracy? Social media innovations and participatory politics. Information Communication and Society, 14(6), 757–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.592648

- López, G. (2016). Decide Madrid’s legacy: source code and support for more and more eParticipation portals in Spain. European Commission. Epractice.Eu. Epractice.Eu. https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/egovernment/document/decide-madrids-legacy-source-code-and-support-more-and-more-eparticipation-portals-spain

- McGonical, J. (2011). Reality is Broken. The Penguin Press.

- Morozov, E. (2013). To save everything, click here: Technology, solutionism, and the urge to fix problems that don’t exist. The penguin books.

- Moser, S. (2010). Creating citizens through play: The role of leisure in Indonesian nation-building. Social and Cultural Geography, 11(1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360903414577

- Mouffe, C. (1999). Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research, 66(3), 745–758. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40971349

- Mouffe, C. (2005). On the political. https://doi.org/JA 71.M6. Routledge.

- The New York Times. (2019). A strong democracy is a digital democracy. The New York Times. from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/15/opinion/taiwan-digital-democracy.html

- Pallett, H. (2015). Public participation organizations and open policy: A constitutional moment for British democracy? Science Communication, 37(6), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547015612787

- Perng, S.-Y., & Kitchin, R. (2016). Solutions and frictions in civic hacking: Collaboratively designing and building wait time predictions for an immigration office. Social & Cultural Geography, 19(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2016.1247193

- Rabbiosi, C. (2019). The frictional geography of cultural heritage. Grounding the Faro Convention into urban experience in Forlì, Italy. Social and Cultural Geography 23 1 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1698760

- Ranciere, J. (1998). Dis-agreement: Politics and Philosophy. University of Chicago Press.

- Rancière, J., Panagia, D., & Bowlby, R. (2001). Ten theses on politics. Theory & Event, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2001.0028

- Rose, G. (2016). Rethinking the geographies of cultural ‘objects’ through digital technologies: Interface, network and friction. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 334–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515580493

- Saulière, S., Escudero, D., & Rebeca Abellán, A. (2018). Digital analysis of Decide Madrid: Users, themes and strategies proposals, for the strengthening of communities. Media Lab Madrid.

- Shaw, I. G. R., & Sharp, J. P. (2013). Playing with the future: Social irrealism and the politics of aesthetics. Social and Cultural Geography, 14(3), 341–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.765027

- Simon, J., Bass, T., Boelman, V., & Mulgan, G. (2017). Digital Democracy: The tools transforming political engagement. Nesta. https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/digital-democracy-the-tools-transforming-political-engagement/

- Thiel, S. K., Reisinger, M., Röderer, K., & Fröhlich, P. (2016). Playing (With) democracy: A review of gamified participation approaches. EJournal of EDemocracy and Open Government, 8(3), 32–60. https://doi.org/10.29379/jedem.v8i3.440

- Tseng, Y. (2021). Navigating the Field. In M. O. Ajebon, C. Y. M. Kwong, & D. A. de Ita (Eds.), Navigating the Field (pp. 91–100). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68113-5

- Tseng, Y. (forthcoming). Assemblage thinking as a methodology for studying Urban AI phenomena. AI & SOCIETY. Springer.

- Tsing, A. (2005). Friction. Princeton University Press.

- The United Nation. (2018). 2018 UNPSA Winners. from https://publicadministration.un.org/unpsa/database/Winners/2018-winners

- Vanolo, A. (2018). Cities and the politics of gamification. Cities, 74(2018), 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.12.021

- Waitt, G. (2005). The Sydney 2002 Gay Games and querying Australian national space. Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, 23(3), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1068/d401

- Woods, O. (2020). The digital subversion of urban space: Power, performance and grime. Social and Cultural Geography, 21(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1491617

- Wright, S. (2011). Politics as usual ? Revolution, normalization and a new agenda for online deliberation. New Media & Society, 14(2), 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811410679

- Wright, S. (2012). Assessing (e-) Democratic Innovations : “ Democratic Goods ” and Downing Street E-Petitions. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 9(4), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.712820

- Wright, S., & Street, J. (2007). Democracy, deliberation and design: The case of online discussion forums. New Media and Society, 9(5), 849–869. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444807081230

- Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford University Press.