ABSTRACT

As UK cities and towns become increasingly ethnically and culturally diverse, researchers have tuned into how people inhabit multiculturalism. Ethnographic approaches have focused on the kind of togetherness that people generate as they go about their everyday lives, observing the affective textures of interactions and happenings of the here and now in granular detail. Missing from these accounts is what crowdsourced data might add to understandings of how multicultural places are experienced. What is vital about this kind of data is that it is ‘big’, involving a diversity of voices similarly intent on messaging their experiences, presenting opportunities to scale up the affect of encounters and to quantify what is difficult to qualify. This paper brings Digital Geographies into conversation with research on everyday multiculturalism to examine qualitatively and quantitatively how social media use folds into and expresses various practices of sociality and connection. Our paper involves Twitter, Nando’s and the city of Leicester in the UK to challenge and advance ways of understanding everyday multiculturalism in an era of global migration and ethnically complex populations.

Resumen

A medida que las ciudades y pueblos del Reino Unido se vuelven cada vez más diversos étnica y culturalmente, los investigadores se han sintonizado con la forma en que las personas habitan el multiculturalismo. Los enfoques etnográficos se han centrado en el tipo de vínculo que las personas crean en su vida cotidiana, observando las texturas afectivas de las interacciones y eventos del aquí y ahora en detalle granular. Lo que falta en estos relatos es lo que los datos de colaboración colectiva podrían agregar a la comprensión de cómo se experimentan los lugares multiculturales. Lo vital de este tipo de datos es que son ‘grandes’, involucrando una diversidad de voces con la misma intención de enviar mensajes sobre sus experiencias, presentando oportunidades para amplificar el afecto de los encuentros y cuantificar lo que es difícil de calificar. Este documento trae a las Geografías Digitales a la conversación con investigación sobre el multiculturalismo cotidiano para examinar cualitativa y cuantitativamente cómo el uso de las redes sociales se pliega y expresa varias prácticas de sociabilidad y conexión. Nuestro artículo involucra a Twitter, Nando’s y la ciudad británica de Leicester para desafiar y promover la comprensión del multiculturalismo cotidiano en una era de migración global y poblaciones étnicamente complejas.

Résumé

Alors que les villes et les localités du Royaume-Uni deviennent de plus en plus diverses sur les plans ethnique et culturel, les chercheurs ont commencé à observer la manière dont les gens vivent le multiculturalisme. Les approches ethnographiques se sont focalisées sur le genre d’unité que les personnes engendrent dans leur quotidien, en étudiant les structures affectives des interactions et des événements du moment en détail granulaire. Ce qui manque à ces narrations, c’est l’apport que des données participatives pourraient avoir envers la compréhension des expériences autour des lieux multiculturels. L’aspect essentiel de ce type de données est qu’elles sont « mégas » et regroupent une multiplicité de voix qui veulent toutes faire part de leurs vécus, ce qui offre des opportunités pour amplifier l’affect des rencontres et pour déterminer les éléments difficiles à qualifier. Notre article engage la géographie numérique dans un dialogue avec la recherche sur le multiculturalisme quotidien afin d’étudier sur les plans qualitatif et quantitatif la façon dont l’utilisation des réseaux sociaux devient partie intégrante de diverses pratiques de socialité et de connexion tout en communiquant celles-ci. Il se sert de Twitter, de la chaîne de restaurants Nando’s et de la ville de Leicester, au Royaume-Uni pour remettre en question et faire progresser les méthodes de compréhension du multiculturalisme quotidien dans une ère de migration à l’échelle mondiale et de populations composées d’une diversité ethnique complexe.

Introduction

Located in the heart of England, Leicester – ‘a city of diversity’ – is regularly the focus of debates about the successes and failures of multicultural Britain (Herbert & Kershen, Citation2008; S. Jones, Citation2015). With black and ethnic minority groups shaping over half (55%) of its population of 329,839 (Office for National Statistics, Citation2011), Leicester is often the poster girl for multicultural Britain, known for annually hosting the biggest Diwali celebration outside of India, its golden mile escaping the unrest that afflicted Bradford, Oldham and Burnley in 2001 (Popham, Citation2013). Leicester’s multiculturalism has also been subject to crisis talk, evident, for example, in Channel 4ʹs 2014 documentary ‘Make Leicester British’, with references to national identity, ethnic groups living separately from one another, different lifestyles and, most recently, the spread of a virus (Sokhi-Bulley, Citation2020; Watson & Saha, Citation2013). Yet away from this celebratory and crisis talk, what interests us and others is how multiculturalism is routinely lived and experienced on the ground (Hall, Citation2012; S. Neal et al., Citation2018; Wessendorf, Citation2014; Wise & Velayutham, Citation2009a). For the most part, this research on ‘everyday multiculturalism’ takes an ethnographic approach involving participatory methods focused on sites of interaction to explore how people live together, identify and negotiate their differences, and the social relations and senses of belonging they shape as they go about their lives. Whilst this research offers richly textured accounts of how multicultural places are experienced, missing from it is larger scale data generated through social media platforms as people photograph, text and message about their lives, experiences and activities. This is a significant absence given that most aspects of cultural life involve digital platforms, making this kind of data relevant to discourses of everyday multiculturalism. So, in this paper we bring Digital Geographies into conversation with research on everyday multiculturalism, examining quantitatively and qualitatively how TwitterFootnote1 – a microblogging service – mediates and expresses practices of sociality and connection. What might crowdsourced information, such as Twitter data, contribute to researchers’ analyses of everyday multiculturalism? Here, we attempt to address this question.

In this paper, we focus our Twitter data analysis on Nando’s, a restaurant chain, in Leicester. We do this for a few reasons. Firstly, although our chief concern in this paper is Twitter data, we wanted to focus our analysis on a site important to many of our participants. Nando’s was heavily referenced in another strand of our project involving young people, who loved going there to eat chicken and meet up with friends. Secondly, when we looked for Nando’s in our Twitter data, we found an appropriate number of references, hashtags and geotags to the restaurant (chain) in Leicester for both our qualitative and quantitative analysis. Finally, a rich vein of work on everyday multiculturalism similarly focuses on the conviviality of cafes and restaurants, places full of opportunity for research and conceptualization of how people live together in their diversity. Connecting our Twitter data analysis to this body of work made sense.

From the outset, we were nervous about what our Twitter data analysis would add, if anything, to ethnographic work on everyday multiculturalism. At first glance, most of the tweets didn’t seem to say much at all, limited in characters, ambiguous in content and obviously not specifically addressing our research concerns. What drove us on was a hunch that crowdsourced data might shape a different perspective on how multiculturalism is experienced, whilst linking with the slighter, distracted social relations that often fuel throwntogetherness as individuals simultaneously engage with digital technology and social media platforms. What might a plurality of voices and scaling up (tweets about experiences and encounters) contribute to ethnographic research on everyday multiculturalism (Wise, Citation2013)? Might we be able to quantify what is difficult to qualify about multiculture? Building on this, we were attracted to how twitter data shapes Nando’s togetherness into networks involving here and there, physical and on-line space, public and private, stretching across cities and continents, unfolding sites of interaction across scales and space. In the next section, we introduce ‘everyday multiculturalism’ and explain our interest in cafés and restaurants. We also set out the concept of conviviality, which describes a particular kind of togetherness, using ingredients of this concept to frame our analysis of Twitter data.

Multiculturalism, conviviality, cafes and restaurants

‘Everyday multiculturalism’ involves the “lived-in’ ethnic and racial diversity that characterises (… .) everyday realities’ (Valluvan, Citation2019, p. 40). It is a ‘dynamic, lived field of action within which social actors both construct and deconstruct ideas of cultural difference, national belonging and place making’ (Harris, Citation2013, p. 7) in contexts that involve social harm, prejudice, bordering practices, nationalism and racism (Clayton, Citation2008; Gilroy, Citation2004; Hardy, Citation2017; Valluvan, Citation2016). Everyday multiculturalism concerns how people inhabit diversity in ways that might feel ‘good enough’ (Harris, Citation2014, p. 584). This ‘good enough’ emphasis is a response to some of the crisis talk that coils around multiculturalism agenda (Lentin & Titley, Citation2011). On 5 February 2011, the British Prime Minister David Cameron gave a speech at the Munich Security Conference that marked a shift in public policy away from a multiculturalist agenda concerned with identity politics and group rights to one focussed on social cohesion. He said that ‘we have failed’ and that pandering to the needs of minority groups only fuelled their isolation and segregation from ‘mainstream’ society (Watson & Saha, Citation2013). This image of ethnic groups living parallel lives is powerfully pervasive, evident in the mapping of census data and focussed on in reports (Cantle, Citation2001; Phillips, Citation2005). Yet this isn’t the complete picture of how multiculturalism is experienced on the ground. Research focused on how people quietly and routinely inhabit their diversity has grown out of political contexts hostile to multiculturalism, immigration and focused on the concerns of so-called ‘mainstream’ society (Wise & Velayutham, Citation2009b). This quietly lived agenda of everyday multiculturalism also seeks to avoid some of the celebratory discourses that coil around diversity, obfuscating tensions, conflicts and inequalities (Watson & Saha, Citation2013).

Our spotlight on Nando’s connects our paper with ethnographic research on the sociality of (chain) cafes and fast-food restaurants, which, with their familiar layouts and routines, are similar from one place to the next (Piekut, Citation2013). (Chain) cafes and restaurants, like Nando’s, are important sites for convivial social relations in multicultural settings. They are a kind of ‘third place’ – not home (first place) or work (second place), but ‘an informal public gathering’ place (Oldenburg, Citation1999, p. 6), where individuals can go, be with others, feel at ease in a place that feels like a ‘second home’. As ‘third places’ they are informal, allowing people to be alone, meet up with friends, encounter others and shape a sense of togetherness in the warmth and neutrality of their surroundings (Laurier & Philo, Citation2006). They are semi-public so that whilst they are privately owned, ‘they take on the form of public space through the ways in which they are used’ (H. Jones et al., Citation2015, p. 645). Unlike community facilities often associated with particular ethnic, cultural or religious groups, these chain restaurants present alternative, comfortable venues for a kind of togetherness not dependent on the traditional, symbolic parameters of community, such as what people have in common. Instead, they help to shape ‘a form of convivial collective life that is an alternative to the more tightly knit collectives such as scouting and sports clubs’ (Laurier, Citation2008, p. 122). These sites of consumption are where people hang out in light touch, informal ways, do things together, encounter and rub along with others. Writing about Anglo senior citizens who were anxious about in-migration and the fragmentation of their imagined sense of community in Australia, Amanda Wise (Citation2011) described how the eating space in a local mall provided neutral space where they could hang out, feel at home, lunching and reading newspapers amongst others. It is this sense of shared ownership which connects these ‘third places’ of informal gathering to feelings of ‘being at home’ through the sense of ease, familiarity and security that they engender.

We draw upon recent writing on conviviality to frame our analysis of Twitter data. Researchers working on multiculture have looked at different ways of conceptualizing the kind of un/easy togetherness described in the Australian mall above and typical of ‘third places’. One such conceptual tool is conviviality which is broadly understood as ‘the capacity to live together’ (Wise & Noble, Citation2016, p. 423) but involves much slighter social relations and a much looser mode of togetherness than other concepts concerned with togetherness – like ‘community’ – suggest (Hall, Citation2012; S. Neal et al., Citation2019). Recent work, though, on community has ignited its more radical associations involving collaborative practices, communing and mutuality and there is a lot of cross-fertilization and reciprocal benefit to work on community and conviviality around this shared ground (S. Neal et al., Citation2019; Rogaly, Citation2016; Studdert & Walkerdine, Citation2016). The focus is on how a sense of togetherness is accomplished. That said, whilst community coils around shared commons, conviviality is more tuned into difference and how people muddle through and work things out between themselves often in the contexts of social harms, tensions and strain (S. Neal et al., Citation2019). Compared to community then, conviviality involves a lighter mode of side-by-side, rather than face-to-face, togetherness shaped by civil inattention and polite, friendly distance, which has brought it to prominence in work concerned with how difference is experienced in multicultural contexts. In this paper, we use conviviality as a lens to explore what analysis of crowdsourced data contributes to understandings of how multiculture is inhabited in Nando’s, focusing on ‘third place’, throwntogetherness, civil inattention and connectedness with others at a distance.

Multiculturalism and Twitter data analysis

To investigate how people inhabit everyday multiculturalism, researchers typically employ ethnographic approaches involving interviewing and participatory methods. The beauty of participatory methods is that researchers are often part of what they are studying, immersed, involved and living in the places at the heart of their ethnographies (Hall, Citation2012; S. Neal et al., Citation2018; Wessendorf, Citation2014). Prompting research is a political context shaped by ‘crisis’ talk about migration, diversity and multiculturalism, provoking researchers to explore counter-narratives, focusing on (their own) multicultural neighbourhoods to explore how diversity is lived as part of routine lives in ways that feel a lot less panicked (Watson & Saha, Citation2013). The concept of conviviality has been useful for work concerned with togetherness because ‘it points to the messy, contingent and often unremarked ways in which people live together and care about one another against the odds, in societies structured by racial division and hierarchy’ (Noronha, Citation2022, p. 160). At the heart of the concept is an anti-racist agenda and a ‘wider ethics ‘of refusing race and salvaging the human” (Noronha, Citation2022, p. 159).

Research on conviviality has faced plenty of critique. Whilst conviviality involves much more than happy togetherness, differences and friction are inadequately theorised (Noronha, Citation2022) and the concept is associated with a ‘descriptive naivety’ (Valluvan, Citation2016, p. 205) that is overly focused on the easiness of living together in super-diverse places, sliding over painful experiences of racism (Burdsey, Citation2013; Nayak, Citation2017). The ways in which structural racism is practiced and spatialized (through gentrification, bordering practices, exclusion and displacement) is not sufficiently woven through research on convivial multiculture (although see Jackson, Citation2019; Noronha, Citation2022). The positionality of researchers has also been critiqued, with the predominance of whiteness making researchers privileged in terms of structural conditions and hierarchical social relations, not identified as outsiders and exposed to the harms of racism and racialization that mediate places (Ang, Citation2018; Yang, Citation2019; Ye, Citation2017). Furthermore, whilst Gilroy’s (Citation2004) conceptualization of conviviality imagined alternative, non-racial, extranational processes of identification, descriptions of diversity trip over their multi-ethnic focus (Noronha, Citation2022).

In response to this critique, we explore what Twitter data analysis might contribute to work on everyday multiculturalism. Twitter data involves a larger scale of data and a plurality of voices, observations, activities and experiences curated by participants. Twitter users present themselves in ways of their choosing, curating their lives and experiences in their own words. Finally, whilst tweeting concerns experiences of places, it is also mindful of a broader context and audience mediating the here and now. To open up research on everyday multiculturalism to this spatial media/tion, we bring it into conversation with Digital Geographies, making use of location aware portable devices, social networks and social media platforms and the crowdsourced information they generate (Ash et al., Citation2016; Leszczynski, Citation2015). Our paper is inspired by research involving Twitter or Instagram data to investigate, for example, how people experience cities (Boy et al., Citation2016; Shelton et al., Citation2015). We expand on this work to explore what tweets express regarding practices and experiences of everyday multiculturalism. Twitter, launched in 2006, allows users to communicate short messages of up to 280 characters in length (Roberts, Citation2017). What particularly interests us here is the flow of mundane tweets that shape people’s lives rather than exceptional tweets (with lots of responses) or tweets about particular events that often inspire Digital Geographies (Rose, Citation2016). These kinds of banal tweets mirror the mundanity of everyday multiculturalism. So our paper focuses on tweets that do not generate a lot of response, that gently pull at ordinary awareness, but rarely come into full frame (Leszczynski, Citation2020; Pink et al., Citation2017; Stewart, Citation2007).

Our project involves a mixed methods approach, straddling the qualitative-quantitative chasm and bringing together researchers with training in Computer Science, Geography and Social Anthropology (Sui & DeLyser, Citation2012). Whilst the focus of this paper is our Twitter data analysis, our concern with Nando’s is shaped by our ‘virtual walking interviews’ (using Oculus Rift Virtual Reality headsets and Google Earth VR) with 24 young people attending colleges in LeicesterFootnote2 where the majority of students do not identify as white British. In 12 interviews, we found ourselves outside a fast-food chicken ‘shop’ or restaurant, most frequently Nando’s. This shaped some of our interrogation of our Twitter dataset, retrieved through the official Twitter API in 2018 and 2019 and comprising about one million public tweets with a geotag in Leicester (involving GPS coordinates or a place reference). Over 1500 tweets referenced chicken, chicken shops and restaurants, including 391 tweets referencing Nando’s (Nando, Nandos, #Nando’s). For this paper, we analysed the 391 tweets in two ways. The first involved a more qualitative approach, the second quantitative. Our qualitative approach involved hand coding tweets referencing Nando’s inductively (and contextually), working closely with the intent and context of tweets, attending to the broader strand of conversation (Jung, Citation2015). The intent of tweets is often unclear with words, such as ‘sick’, full of various meaning, so the broader context is important for a deeper understanding (Jung, Citation2015). Furthermore, the meaning of tweets is often conveyed through abbreviations, emoji, Twitter- or culturally specific – lingo, which require a wider reading to understand them better. This analysis of tweets inevitably involves blind spots caught up in researcher positionality and experience, which shape our reading of them with us variously positioned in terms of age, class, gender, residency status and personal use of Twitter. Whilst we all identify ourselves as white, Stefano is not white British and Katy’s family members don’t tick that box either, a diverse household living in a diverse city. The deductive element of this qualitative strand was framed by work on conviviality involving Nando’s as a ‘third place’, emotion, togetherness, civil inattention and connection across distance, with our coding involving these themes.

Our quantitative approach involved algorithmic sentiment analysis to estimate the sentiments expressed for Nando’s (Bifet & Frank, Citation2010). Before we began this analysis, we prepared the data to remove elements that could identify individuals or that sentiment analysis tools would not be able to handle. To do this, we preprocessed the text using the R package textclean (Rinker, Citation2018a), removing web links (i.e. URLs), emails and username mentions. Next, we removed the hash symbol from hashtag mentions, leaving them as plain text, and replaced contractions, word elongation and internet slang with plain text equivalents. We replaced dates, times, grades, ratings, numbers, symbols, emoticons and emoji with their text equivalent. Whilst these steps might not always align with what the author meant when they wrote the tweet, they usually provide more accurate results at the aggregate level than if left intact. We then used the R package textstem (Rinker, Citation2018b) to lemmatize the text and the R package sentimentr (Rinker, Citation2019) to compute the sentiment of tweets. The latter assesses the polarity (negative or positive) of sentences (not just individual words), taking into account valence shifters such as amplifiers, deamplifiers and negators. For instance, the word ‘good’ is generally marked as positive, but is negative if preceded by ‘not very’. This approach has been shown to outperform simpler approaches which don’t account for valence shifters (Naldi, Citation2019).

In what follows we introduce Nando’s as a semi-public, informal, ‘third place’ that mediates experiences of multiculture and is itself mediated by tweets that shape those experiences. We then interrogate the significance of Twitter data in relation to some key ingredients of conviviality concerning throwntogetherness, civil inattention and connectedness across distance. We pepper our writing and analysis with illustrative tweetsFootnote3 (in italics) to mirror how they are experienced as part of everyday lives. Let’s go Nandos!

Introducing Nando’s: a third place

@ Sam haha visit your second home- Nando’s ☺

Space and place matter in terms of how they are folded into opportunities, interactions and sentiment of togetherness (Wise & Velayutham, Citation2014). Nando’s, a globally operating restaurant chain, presents itself as broadly multicultural in its outlook (https://www.nandos.com/story/). Its food and dining experience cannot be associated with any particular people or location meaning that the Nando’s experience is not about, essentializing or ‘eating the other’ or cultural appropriation, but a place ‘where everyday multiculturalism is inhabited rather than appropriated as a form of cultural capital’ (Wise, Citation2011, p. 90). This is important because, as ‘the sociologist Richard Sennett put it, ‘people can be sociable only when they have some protection from each other’ (Oldenburg, Citation1999, p. 41). Founded in South Africa in 1987 by Robert Brozin and Fernando Duarte, this broad multicultural agenda is woven through its South African roots, its naming after Fernando, a Portuguese national, its menu offering and peri-peri sauces (made from Mozambique peppers) and the African Latino/a music played in restaurants (Sawyer, Citation2010). They’re playing Karolina in Nandos☺♥ Cardi Bs ‘I Like It’ sounds like something you’d hear in Nandos. There are approximately 1200 Nando’s restaurants operating worldwide across 30 countries and the restaurant chain is especially popular in South Africa, Canada, Australia and the UK. Four Nando’s restaurants have located in Leicester since 1992.

The attraction of Nando’s to young people shone through our Twitter data with its free refills of fizzy drinks (When it’s your 3rd time using a water cup for fizzy in Nando’s and the staff recognise you), social heat and escape from the stresses and strains of school and college life (Rhys-Taylor, Citation2017; Sawyer, Citation2010). My brother is at Nandos and im fkn revising now is that fair. This attraction is powerfully shaped by marketing campaigns involving social media platforms and well-known musicians. In 2010, Ed Sheeran and Example posted on YouTube their performance of Nando’s Skank, which has had more than five million views. The British desire for a ‘cheeky Nando’s’ has flooded social media platforms with the Peri Boyz performing a song about it https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOjG5usM_y4), whilst others explain the meaning of a ‘cheeky Nando’s’ (e.g.,https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gxbncxJYQMw) to older, middle-class audiences and baffled Americans, generating further social media attention. Class variously modulates Nando’s through its conspicuous consumption and depending on country context. In South Africa, for example, Chevalier (Citation2015) suggests that precarious, often on credit, new, black, professional class status is practiced through dining out and eating Nando’s (Chevalier, Citation2015). In contrast, our Leicester Twitter data involved a politician using Nando’s to downplay his status as he posted a picture of himself and colleagues eating there, generating responses such as I bet they just wondered in there because they thought it was some kind of posh eatery and didn’t realise normal people go there.

Tweets also reveal that Nando’s attracts an older demographic involving leisurely families – Celebrating the nephews birthday last night Nandos style☺can’t believe he’s now a teenager …. when did that happen (see, ). Nandos with the nagging mother and Diane – and people taking a break from work i also had a nandos for lunch that work paid for so yknow. Nando’s, as a third place, accommodates all kinds of social occasions – Have been bullied into watching Frozen 2 today … made them have Nandos first, including couples on a (first) date. One man was Sat in Nandos thinking my dates stood me up, nope she’s at the wrong fucking Nandos ☺☺. It’s also a place where people go alone – Sat having tea on my own in nando’s and they’ve put me in a booth for eight just cos its in the corner out of the way ☺ thanks huns. Twitter identifies Nando’s as a place where people can be alone, but together.

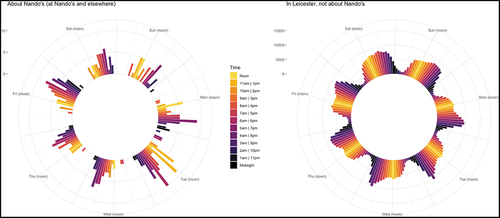

As a third place, Nando’s presents itself as a site where people can hang out and togetherness is comfortably accomplished throughout the week (). Twitter users often look forward to going to Nando’s, craving and wanting a Nando’s, hopeful and expectant about what lies ahead I hope you start getting some better days Zep. I’m collecting my Nandos points so I can treat you. This hopefulness mirrors some of the emotional tone of writing on everyday multiculturalism (Wise, Citation2013). Other accounts of everyday multiculturalism, though, are less expectant as they sketch out, at best, the ambivalence of the ‘breathable diversity’ woven through encounters with ‘familiar strangers’ (Ye, Citation2016) and the ‘festering resentment’ experienced (Aptekar, Citation2019; Nayak, Citation2017). In the next section, we interrogate what throwntogetherness in Nando’s adds up to and involves through our Twitter data analysis.

Throwntogetherness, civil inattention (and uncivil attention)

In total, 127 tweets were geotagged or explicitly concerned experiences of throwntogetherness inside a Nando’s restaurant in Leicester (other tweets were more ambiguous or commenting on Nando’s from elsewhere in the city). Massey (Citation2004) identifies throwntogetherness as involving people, place and temporality, dis/order and chance, heterogeneity, stuff and things, ‘an ever shifting constellation of trajectories’ ‘contoured through the playing out of uneven power relations’ (Massey, Citation2004, pp. 151–153). In Leicester, Nando’s throwntogetherness involves people, music, food, counters, queuing alongside others to place an order – Im currently standing in a queue with 10 other people which is fun when you’re on a crutch … ., pausing by the sauces whilst considering just how spicy to go, sliding into seats, noticing people and happenings at other tables, whilst waiting for food to arrive. Did I actually just say ‘thanks, you too’ to the nando’s waiter after he said ‘thanks, enjoy your food’. Waiting staff at Nando’s are typically young, under the age of 25, and reflect the ethnic and cultural diversity of its customers – so ya girl got a job at nandos? Their presence is significant, overseeing happenings, ‘transversal enablers’ front of house, facilitating togetherness (Crang, Citation1994; Wise & Velayutham, Citation2014). As the waiter walks away, chicken wings, thighs, sauce, sweetcorn, chips and creamy mash steam into the mix, demanding attention, finger licking and a search for some fresh serviettes. These routines, rhythms and (unwritten) codes of conduct are absolutely key to what individuals do, how they feel and the kind of togetherness accomplished in Nando’s (Laurier & Philo, Citation2006).

Most ethnographies of cafes and restaurants focus on the ‘uneventfulness’ of throwntogetherness, involving ‘thin forms of sociality’ around small smiles, brief eye contact and sharing paper napkins to mop up spills (H. Jones et al., Citation2015; Laurier & Philo, Citation2006). Shaping this uneventfulness is civil inattention – ‘the practice of recognition but not reaction’ (H. Jones et al., Citation2015, p. 647) – as people handle their vulnerabilities in throwntogetherness. Snatches of conversation are explored, with small gestures sometimes amplified through talk as Jones et al. (Citation2015) illustrate with a light-hearted moment in a Costa café that coiled round misrecognition: ‘you’re Greek’, a correction – ‘I’m Asian, you’ve got the wrong continent!’ which ‘felt banal and convivial rather than testing and sanctioning’ (p. 653). The quality of ethnographic research dwells in its attention to detail, observing individuals shape and negotiate their differences in ways described as uneventful.

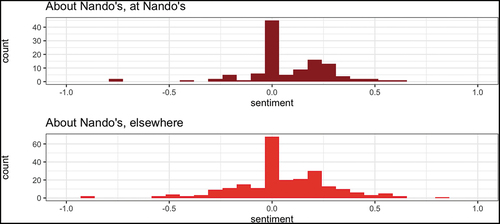

Our quantitative data analysis of Twitter data develops this ethnographic research in a few ways. Firstly, it gets beyond a focus on individuals and their interactions to investigate the (emotional) quality of sociality generated by throwntogetherness. This chimes with Nowicka’s (Citation2020) push for less focus on the collaboration of individuals and more focus on the sociality of conviviality, which analysis of social media data begins to enable. Secondly, algorithmic sentiment analysis begins to substantiate and quantify the emotional tone of sociality in sites and places, tuning into particular words in tweets and giving them a value, generating a sense of how the sociality of place, in all its throwntogetherness, is felt (see, ). This links to concerns that conviviality doesn’t just involve practices and the social, but ‘can be understood as an atmosphere and affect’ (Wise & Velayutham, Citation2014, p. 407). Twitter data analysis begins to express the cumulative affect of tweets, through brief strings of words concerned with dispositions, encounters, a place, chicken, happenings and involving degrees of positivity and negativity. Perhaps crowdsourced data analysis presents opportunities ‘to comprehend the full range of interactions, behaviours and meanings’ that shape coexistence (Wise & Velayutham, Citation2014, p. 425).

Figure 3. Algorithmic sentiment analysis of tweets geo-tagged in Leicester, about Nando’s, in Nando’s (top) and elsewhere (bottom), conducted in R using the sentimentr library (https://github.com/trinker/sentimentr). Values above zero indicate the algorithm has estimated a positive sentiment; values below zero indicate a negative sentiment; zero values indicate a neutral or undefined sentiment.

Thirdly, and building on the above, at first glance our quantitative analysis of tweets supports the civil inattention described in convivial sites and settings with showing the overarching neutrality of tweets in their sentiment. This means that people are neither negative nor positive about their experiences of Nando’s as they, for example, focus on what they and their companions are eating. You think you know someone then you find out they order a wrap at Nandos. Gone to medium at Nandos feelin like a new woman. That said, our Twitter data analysis began to show people noticing and tweeting more than their poker faces might reveal. At the more positive (+1) end of , Twitter users were reflecting on their friendly interactions with others, using words like ‘love’, which were picked up in our algorithmic sentiment analysis – love the reactions I get from Nando’s staff when they see how many chillis I have. In contrast, at the other end of the spectrum, Twitter data also began to reveal a thin negative thread (−1), uncivil attention – ‘some of the discreet performances of othering’ (Nayak, Citation2011, p. 554) – involving judgment of others who were identified as different or behaving differently. Just witnessed some radge schmuck in nandos put half coke half Fanta in the same glass like he was making a mixed ice blast. And People walk through Nando’s doors and all their common sense & manners stay outside. Tweets can be disapproving: There’s a girl in Nando’s in just a bra. I mean, is that even okay? I’ve just seen a group of students drinking Prosecco. I take everything I said back, put their fees up. Tweets reveal the power relations that saturate everyday multiculturalism, enabling some individuals to comment about, and judge, others. Anyone who holds chicken like that can’t be trusted.

Uncivil attention evident in tweets shows not only that people notice more than often assumed, but are also more judgemental than ethnographic research suggests. It brings into view how participants experience their throwntogetherness. Tweets involving negative, judgemental observation of others were much more evident in the Nando’s data set, than tweets about uncomfortable experiences involving sharp looks and racism. This might be a limitation of this particular, publically accessible, social media platform and what people feel able to tweet. It also reflects structural conditions, hierarchical social relations and politics that mediate place and multiculture, enabling the ‘we’ of community to tweet about their observations and experiences of those they identify as different, whilst others are silent and silenced (Ye, Citation2017). It shows that the kind of togetherness that shapes conviviality, and the civil inattention involved, is mediated by uncivil attention of a kind that is missed in ethnographic research because it does not involve any overt reaction or interaction. Tweets reveal the subtle, invasive resentments and attention that mediate space.

In the same way that there are gaps in ethnographic research on multiculture, so too are their holes in social media data analysis, which is restricted to those who use this particular social media platform, how they want to present themselves and what they want to tweet about (Leszczynski, Citation2018). Furthermore, algorithms miss the subtleties of tweets, such as humour and sarcasm, that more qualitative analysis of Twitter data explores. If you don’t get peri-salted chips from nandos you’re a pedo. I just got called a ‘weak ass bitch’ for having lemon and herb sauce on my Nandos burger. Swear to god if Jac violates me one more time about my Nandos choice I’m gonna sling a butterfly bugger straight off his forehead. *burger, leave me alone, I’m revision-stressed. Whilst our quantitative analysis was negative around the use of ‘bitch’ and ‘violates’, our more qualitative analysis recognized some of the humour in the tweets. Not just algorithms misunderstand, though, so do we with our blinkered positionalities. In many ways, we’re still no closer to any kind of truth than ethnographic research. Social media data does, though, offer another perspective that both compliments and asks questions of ethnographic accounts, such as, how civil is all the inattention?

#Nando’s and togetherness on Twitter

Ethnographic research on everyday multiculturalism is a ‘microgeographical phenomenon’, grounded in the micro-politics of everyday life in local neighbourhoods (Kaplan & Moigne, Citation2019, p. 393). Whilst researchers often see these places in the context of their wider sociospatial, historical and political relations, it is tricky to hold these broader contexts and networks in view whilst embroiled in the here and now of interactions. Geotagged tweets similarly could have a simple relationship with a location, pinning 280 (or less) characters to the longitude and latitude coordinates of a place. Interesting research agendas (Shelton et al., Citation2014), though, have demonstrated the importance of thinking about the complex sociospatial relations of a geotagged tweet beyond its simple relationship with a location.

Whilst Nando’s is an important physical space for sociality in a multicultural urban context, geotagged tweets about experiences in Nando’s connect people in the restaurant with others elsewhere and at home, involving private space. The 127 tweets in our data set that were purposely geolocated, or their content explicitly connected them to Nando’s restaurants in Leicester, meant that, on one hand, individuals are overt in their connection and involvement in Nando’s, whilst on the other, their tweets suggest a distracted, looser association with throwntogetherness as they interact digitally with others elsewhere. Connecting with others elsewhere, involving the domestic and private, is important for work on conviviality, because these spaces have been remarkable for their absence yet surely haunt how sociality is experienced (Nowicka, Citation2020). Whilst work on the conviviality of multiculture is concerned with the slighter, extensive rather than intensive, kind of sociality that shapes throwntogetherness, exploring how social media saturates it further emphasizes these looser (and broader) relations and connections that mediate how it is experienced. In her paper on ‘Platform affects of geolocation’, Leszczynski (Citation2019) explored how geolocation is ‘leveraged as an instrumentality of securing’ (p. 212) feelings of connection and trust as people use Twitter to affectively connect with others elsewhere, sharing a sentiment, opinion or what they are doing in a place. Is it just me or are the halloumi slices at nandos overly salty? And others become involved in experiences of Nando’s as they tweet their responses. swear everyone seems to be in nando’s tonight but Me xx. Social media platforms and physical (public and private) places weave through one another with the digital mediation of Nando’s shaping experiences of place both material and imagined.

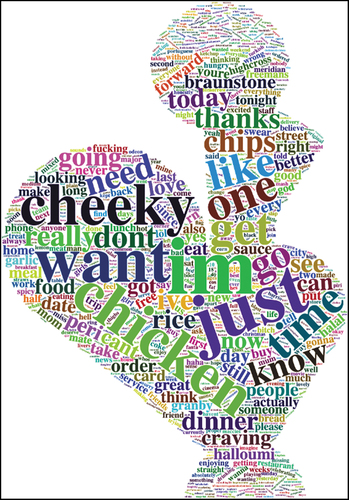

Individuals also hashtag #Nando’s to connect with others, when not in a Nando’s restaurant. Hashtagging creates a specific term that can be searched to connect users to a channel of chat (Fekete & Haffner, Citation2019), subsequently creating potential new social networks. Tweets invoking ‘Nando’s’ or (#Nando’s) are posted from restaurants in Leicester, but also from other locations too as individuals reference both the physical space and the social experience of Nando’s to hook up with others around, for example, craving a ‘PHATTTTT nando’s’ (see, ). 264 tweets were not geotagged to – or obviously tweeted inside – a Nando’s restaurant. shows similar patterns of sentiment in tweets sent from outside a Nando’s restaurant, peaking in their ambivalence, but trailing plenty of positive and some negative sentiment, nudging others into some kind of response. I really do not see the Nando’s hype. Nando’s is soooo overrated. Reply: Shut up. This invocation of ‘Nando’s’ generates a ‘digital third place’ (McArthur & White, Citation2016), where people gather on a social media platform (that has many of the characteristics of a physical third place involving informality, talk, easiness) around a shared interest and experience, in a channel of chat. Whilst most of the comments do little more than reference Nando’s (Really want a Nandos ☺☺), individuals associate with Nando’s, folding themselves into its stretched out contours (Bookman, Citation2013). Nando’s is rooted in urban places like Leicester, but has associations with Southern Africa, Portugal and nowhere in particular, so that eating and tweeting about Nando’s means connecting with its worldly vibe Kenapa tetiba craving nandos ni ☺☺☺☺. illustrates the words most keenly used in tweets about Nando’s with want, need, craving, just, go, get, one, cheeky and chicken figuring strongly as people connect with others around Nando’s.

Figure 4. Word-cloud generated from the text of tweets geo-tagged in Leicester, about Nando’s. The words ‘nando’, ‘nandos’, ‘nando’s’, ‘leicester’, ‘leicestershire’ have been excluded as their frequency would have rendered them too large for the visualization.

Whilst we set out to explore how a social media platform like Twitter mediates Nando’s restaurants, shaping how multiculture is inhabited, we began to flip this, letting Nando’s mediate #Nando’s as we observed individuals become invested in the ‘ecosystem’ of a social media platform, using it to reach out and connect with others. All I see on my news feeds tonight is everyone talking about wanting Nando’s and I’m craving one so badly. Yo @jjr I share your love for Nando’s too ☺. Reference to Nando’s prompted responses and emoji, encouraging “connectedness at a distance’ through which individuals both express and experience sensibilities of continuous technologically mediated connectivity’ (Leszczynski, Citation2019, p. 212). all I want is a nando’s but don’t think the 33p in my bank will suffice. Nando’s restaurants, though, always lingered, never disappeared entirely from view. Whilst some tweets were more about referencing Nando’s to simply connect with others, seeing who might respond, other tweets demanded more in the way of interaction and connection, nudging others into a more involved response, possibly even a trip to Nando’s:

Anyone in Leicester wanna go with me to Nando’s???

@curvieunicorn @Annahb @elsisha @sajidjavide1 Let’s go Nandos babes

Conclusions

A starting point for this paper is what Twitter data adds to understandings of how people inhabit and experience multiculture. We were not particularly interested in those tweets that attract immense attention, but in the vein of existing research on everyday multiculturalism, mundane tweets that flow across screens as part of routine lives. Interviews with young people in Leicester directed us to tweets involving Nando’s and these became the focus of our work for this paper. Our particular concern with Nando’s also connects our paper with ethnographic research on the significance of chain cafes and restaurants for experiences of everyday multiculturalism (H. Jones et al., Citation2015). The semi-public, informality of these places folds a diverse clientele into their rhythms and routines, accommodating the un/easiness of multicultural lives.

We finish on what we think working with social media data adds to research on everyday multiculturalism and the conviviality that shapes it. For Nowicka (Citation2020), research on conviviality has been too focused on the collaboration of individuals and could move more towards sociality – the togetherness created that transcends individuals – and the emotions, power and identity relations that underpin it. Research concerned with the conviviality of everyday multiculturalism also tends to put public, or semi-public, places, centre stage, leaving private and domestic settings in the shadows, unknown in terms of, for example, the kind of conviviality shaped by migrant domestic workers and their employers (Nowicka, Citation2020). Weaving social and spatial media analysis into research on everyday multiculturalism begins to address these absences.

Firstly, Twitter data involve a diversity of voices, not just that of the researcher and selected interviewees, enabling participants to curate themselves, their experiences and activities, entangling their smartphones and use of social and spatial media in the milieu of throwntogetherness. Twitter data analysis scales up experiences and encounters, providing a sense of how sociality – in its entirety – is felt and practiced, getting beyond individual experiences. This leads to a second point – that algorithmic sentiment analysis begins to quantify what is difficult to qualify in ethnographic research regarding the atmosphere and affect of conviviality. This is important to Wise and Velayutham (Citation2014), who suggest that conviviality doesn’t just involve practices and the social, but has an affective dimension too. Complimenting ethnographic research, our algorithmic sentiment analysis of Twitter data reinforces much of the neutrality described in accounts of everyday multiculturalism as people rub along together with nothing much to report. Twitter data though also begins to fill absences of ethnographic research through identifying not only positivity, but some negativity that demand attention. This leads to our third point, that tweets provide some insight into what people are thinking in places, contradicting some of the civil inattention – ‘practices of recognition rather than reaction’ (H. Jones et al., Citation2015, p. 647) – observed by researchers. Tweets revealed uncivil attention – ‘discreet performances of othering’ (Nayak, Citation2011, p. 554) – with some people empowered enough to judge, criticize and tweet about others, marking them out as different or behaving differently, whilst reinforcing the ‘we’ of community here and out there (Aptekar, Citation2019; Burdsey, Citation2013; Ye, Citation2017). General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) on the use of Twitter mean that inferring most user demographics is prohibited by Twitter for user privacy reasons, so prevented any characterization of our dataset by demography. Not being able to work with or infer user demographics means that analysis of who feels, for example, empowered enough to judge others is not possible, as we understand Twitter’s policies for researchers. Furthermore, our Twitter data involving Nando’s did not reveal how it felt to be subject to such judgment or resentment, which is perhaps another weakness of this particular social media platform, with its public orientation providing a stage for some to speak up, whilst others are silent or silenced, fearing the repercussions of their tweeting. Not being able to identify who tweets and who is tweeted about is both frustrating and interesting. On one hand, we’re unable to cut into the power relations that modulate who judges and who is judged. On the other, researchers attend to the conviviality of everyday multiculturalism in ways that might work against race. Twitter data analysis offers a way into ‘(t)he radical openness that brings conviviality alive and makes a nonsense of closed, fixed, and reified identity and turns attention toward the always-unpredictable mechanisms of identification’ (Gilroy, Citation2004, p.xi).

We experienced plenty of challenges in our (algorithmic sentiment) analysis of Twitter data. Our analysis is limited to those who use Twitter and what they (feel able to) tweet about as they carefully curate themselves, their experiences and activities on a social media platform that is publically available. It is shaped by ‘off-the-peg’ software libraries designed to attribute positive or negative sentiment to words that shape a tweet (Marciniak, Citation2016) and miss, for example, the humour and sarcasm of human interactions (Sykora et al., Citation2020). Incorporating more qualitative analysis of tweets into our quantitative analysis was how we tried to reduce some of these limitations. Another creative solution, enabling the use of bigger data sets, would be to inflect some of this qualitative insight into algorithmic programmes tailored to the particular needs of projects like this. Even with these adjustments and advances though, crowdsourced data analysis of this kind is no closer to any form of truth regarding how everyday multiculturalism is lived and experienced. What it does do is bring throwntogetherness into view, transcending individuality, quantifying what is difficult to qualify, scaling up and complimenting and contradicting ethnographic approaches and insight.

Finally, focus on social media platforms and crowdsourced data analysis connects research practices with theories and concepts like conviviality that are concerned with a looser mode of togetherness. Whilst tweeting in Nando’s, an individual shapes civil inattention (and uncivil attention) there, but simultaneously reaches out and connects with people and places elsewhere, making a network out of Nando’s shaped by here and there, public and private, that stretches across cities and continents. Twitter data also reveal how people use Nando’s when not in its restaurants to identify themselves and connect with others across distance. Associating with its popular appeal and worldly, sanitized vibe, people seek out others around, typically, wanting ‘a cheeky Nando’s’. This meant that Nando’s began to feel unmoored from its physical location when simply the suggestion of ‘Nando’s’ became a point of connection on a social media platform – Twittersphere (Bruns et al., Citation2017). These tweets prompted responses (or not), connecting with others in the slightest of ways. Given the liveliness of Twittersphere and the significance of social media platforms in the lives of young people, though, we would like to end by flipping our original concern. This paper has attempted to show what social and spatial media, such as Twitter, contribute to experiences of, as well as research on, multicultural places. The next step is to consider how physical places mediate young people’s experiences of multicultural Twittersphere, and the ramifications of this both for online togetherness – and for physical places.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the students, teachers and colleges in Leicester who took part in this research and to Isaac and Hannah for the trips to Nando's. Many thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their time and very helpful, thoughtful comments. Finally, big thanks to Helen Wilson for all her guidance. This research was funded by a Leverhulme Trust Research Project Grant: ‘Mapping Multiculture: Disrupting representations of an ethnically diverse city’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We chose Twitter over other social networks because of the text-based nature of tweets and the public – and often longstanding availability – of tweets. Posts on other platforms are often not publically available and/or only temporary. Twitter is a popular social media platform with a large number of users generating publically accessible and usable (open) data (Roberts, Citation2017). It is the most popular platform for referencing and following Nando’s too. In 2018, Nando’s UK Twitter feed had 1.49 million followers, whilst the company had 244,000 UK Instagram followers and 8767 subscribers on its YouTube channel (McCreesh, Citation2018)).

2. The research has been subject to research ethics policies at the University of Leicester and the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Leicester approved the research project on 20/1/20 (20,075).

3. Our reproduction of tweets (and related photographs) required ethical fabrication (Williams et al., Citation2017), whereby each tweet’s text was modified to render it undiscoverable by internet search engines without compromising its intended meaning.

References

- Ang, S. (2018). The ‘new Chinatown’: The racialization of newly arrived Chinese migrants in Singapore. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(7), 1177–1194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1364155

- Aptekar, S. (2019). The unbearable lightness of the cosmopolitan canopy: Accomplishment of diversity at an Urban farmers market. City & Community, 18(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12371

- Ash, J., Kitchin, R., & Leszczynski, A. (2016). Digital turn, digital geographies? Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516664800

- Bifet, A., & Frank, E. (2010). Sentiment knowledge discovery in twitter streaming data. In H. G. P. B & A. Hoffmann (Eds.), Discovery science lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 6332, pp. 1–15). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16184-1_1

- Bookman, S. (2013). Branded cosmopolitanisms: ‘Global’ coffee brands and the co-creation of ‘cosmopolitan cool’. Cultural Sociology, 7(1), 56–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975512453544

- Boy, J. D., Uitermark, J., & Preis, T. (2016). How to study the city on instagram. PLOS ONE, 11(6), e0158161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158161

- Bruns, A., Moon, B., Münch, F., & Sadkowsky, T. (2017). The Australian twittersphere in 2016: Mapping the follower/followee network. 34. Social Media Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117748162

- Burdsey, D. (2013). ‘The foreignness is still quite visible in this town’: Multiculture, marginality and prejudice at the English seaside. Patterns of Prejudice, 47(2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2013.773134

- Cantle, T. (2001). Community cohesion: A report of the independent review team. Home Office.

- Chevalier, S. (2015). Food, malls and the politics of consumption: South Africa’s new middle class. Development Southern Africa, 32(1), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2014.965388

- Clayton, J. (2008). Everyday geographies of marginality and encounter in the multicultural city. In C. Bressey & C. Dwyer (Eds.), New geographies of race and racism (pp. 255–268). Ashgate.

- Crang, P. (1994). It’s showtime: On the workplace geographies of display in a restaurant in southeast England. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12(6), 675–704. https://doi.org/10.1068/d120675

- Fekete, E., & Haffner, M. (2019). Twitter and academic geography through the lens of #AAG2018. The Professional Geographer, 71(4), 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2019.1622428

- Gilroy, P. (2004). After empire: Melancholia or convivial culture? Routledge.

- Hall, S. (2012). City, street and citizen the measure of the ordinary. Routledge.

- Hardy, S.-J. (2017). Everyday multiculturalism and ‘hidden’ hate. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Harris, A. (2013). Young people and everyday multiculturalism. Routledge.

- Harris, A. (2014). Conviviality, Conflict and Distanciation in young people’s local multicultures. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 35(6), 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2014.963528

- Herbert, J., & Kershen, D. A. J. (2008). Negotiating boundaries in the city: Migration, Ethnicity, and Gender in Britain. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jackson, E. (2019). Valuing the bowling alley: Contestations over the preservation of spaces of everyday urban multiculture in London. The Sociological Review, 67(1), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118772784

- Jones, S. (2015). The ‘metropolis of dissent’: Muslim participation in Leicester and the ‘failure’ of multiculturalism in Britain. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(11), 1969–1985. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2014.936891

- Jones, H., Neal, S., Mohan, G., Connell, K., Cochrane, A., & Bennett, K. (2015). Urban multiculture and everyday encounters in semi-public, Franchised cafe spaces. The Sociological Review, 63(3), 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12311

- Jung, J.-K. (2015). Code clouds: Qualitative geovisualization of geotweets. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 59(1), 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12133

- Kaplan, D. H., & Moigne, Y. L. (2019). Multicultural engagements in lived spaces: How cultural communities intersect in Belleville, Paris. City & Community, 18(1), 392–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12358

- Laurier, E. (2008). How breakfast happens in the Café. Time & Society, 17(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X07086306

- Laurier, E., & Philo, C. (2006). Possible geographies: A passing encounter in a café. Area, 38(4), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2006.00712.x

- Lentin, A., & Titley, G. (2011). The crises of multiculturalism: Racism in a neoliberal age. Zed Books.

- Leszczynski, A. (2015). Spatial media/tion. Progress in Human Geography, 39(6), 729–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514558443

- Leszczynski, A. (2018). Digital methods I: Wicked tensions. Progress in Human Geography, 42(3), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517711779

- Leszczynski, A. (2019). Platform affects of geolocation. Geoforum, 107, 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.011

- Leszczynski, A. (2020). Digital methods III: The digital mundane. Progress in Human Geography, 44(6), 1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519888687

- Marciniak, D. (2016). Computational text analysis: Thoughts on the contingencies of an evolving method. Big Data & Society, 3(2), 2053951716670190. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716670190

- Massey, D. B. (2004). For space. SAGE.

- McArthur, J. A., & White, A. F. (2016). Twitter chats as third places: Conceptualizing a digital gathering site. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 2056305116665857. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116665857

- McCreesh, L. (2018, July 5). There’s nothing cheeky about these Nando’s facts, including its HUGE fan base overseas. Bustle. Available from https://www.bustle.com/p/who-founded-nandos-channel-5s-new-doc-is-lifting-the-lid-on-the-peri-peri-kingdom-9676079

- Naldi, M. (2019). A review of sentiment computation methods with R packages. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08319

- Nayak, A. (2011). Geography, race and emotions: Social and cultural intersections. Social & Cultural Geography, 12(6), 548–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.601867

- Nayak, A. (2017). Purging the nation: Race, conviviality and embodied encounters in the lives of British Bangladeshi Muslim young women. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42 (2), 289–302. 1965. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12168

- Neal, S., Bennett, K., Cochrane, A., & Mohan, G. (2018). Lived experience of multiculture: The new social and spatial relations of diversity. Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

- Neal, S., Bennett, K., Cochrane, A., & Mohan, G. (2019). Community and conviviality? Informal social life in multicultural places. Sociology, 53(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518763518

- Noronha, L. D. (2022). The conviviality of the overpoliced, detained and expelled: Refusing race and salvaging the human at the borders of Britain. The Sociological Review, 70(1), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380261211048888

- Nowicka, M. (2020). Fantasy of conviviality: Banalities of multicultural settings and what we do (not) notice when we look at them. In O. Hemer, M. P. Frykman, & P.-M. Ristilammi (Eds.), Conviviality at the crossroads: The poetics and politics of everyday encounters (pp. 15–42). Springer International Publishing.

- Office for National Statistics. (2011). Leicester local authority local area report. Available from https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/reports/localarea?compare=E06000016

- Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. Marlowe & Co.

- Phillips, T. (2005 September 22). After 7/7: Sleepwalking to segregation. Speech to Manchester Council for Community Relations.

- Piekut, A. (2013). “You’ve got a Starbuck’s and coffee heaven … I can do this!” Spaces of social adaption of highly skilled migrants in Warsaw. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 2(1), 117–138 https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=206297

- Pink, S., Sumartojo, S., Lupton, D., & Heyes La Bond, C. (2017). Mundane data: The routines, contingencies and accomplishments of digital living. Big Data & Society, 4(1), 205395171770092. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717700924

- Popham, P. (2013, 26 July). We’re all in this together: How Leicester became a model of multiculturalism Independent . Available from https://www.independent.co.uk/

- Rhys-Taylor, A. (2017). Food and multiculture a sensory ethnography of East London. Routledge.

- Rinker, T. W. (2018a). textclean: Text cleaning tools. Available from https://github.com/trinker/textclean

- Rinker, T. W. (2018b). textstem: Tools for stemming and lemmatizing text. United State. Available from http://github.com/trinker/textstem

- Rinker, T. W. (2019). sentimentr: Calculate text polarity sentiment. Available from http://github.com/trinker/sentimentr

- Roberts, H. V. (2017). Using twitter data in urban green space research: A case study and critical evaluation. Applied Geography, 81, 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.02.008

- Rogaly, B. (2016). ‘Don’t show the play at the football ground nobody will come’: The micro-sociality of co-produced research in an English Provincial City. The Sociological Review, 64(4), 657–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12371

- Rose, G. (2016). Cultural geography going viral. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(6), 763–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1124913

- Sawyer, M. (2010, May 16). How Nando’s conquered Britain. The Observer Sunday https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/may/16/nandos-fast-food-chipmunk-tinchy

- Shelton, T., Poorthuis, A., Graham, M., & Zook, M. (2014). Mapping the data shadows of hurricane sandy: Uncovering the sociospatial dimensions of ‘big data’. Geoforum, 52, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.006

- Shelton, T., Poorthuis, A., & Zook, M. (2015). Social media and the city: Rethinking urban socio-spatial inequality using user-generated geographic information. Landscape AND Urban Planning, 142, 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.020

- Sokhi-Bulley, B. (2020) From exotic to ‘dirty’: How the pandemic has re-colonised Leicester.Discover Society, July 16th. Available from https://archive.discoversociety.org/2020/07/16/from-exotic-to-dirty-how-the-pandemic-has-re-colonised-leicester/

- Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary Affects. Duke University Press.

- Studdert, D., & Walkerdine, V. (2016). Being in community: Re-visioning sociology. The Sociological Review, 64(4), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12429

- Sui, D., & DeLyser, D. (2012). Crossing the qualitative-quantitative chasm I: Hybrid geographies, the spatial turn, and volunteered geographic information (VGI). Progress in Human Geography, 36(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510392164

- Sykora, M., Elayan, S., & Jackson, T. W. (2020). A qualitative analysis of sarcasm, irony and related #hashtags on Twitter. Big Data & Society, 7(2), 205395172097273. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720972735

- Valluvan, S. (2016). Conviviality and multiculture: A post-integration sociology of multi-ethnic interaction. Young, 24(3), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308815624061

- Valluvan, S. (2019). The uses and abuses of class: Left nationalism and the denial of working class multiculture. The Sociological Review, 67(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118820295

- Watson, S., & Saha, A. (2013). Suburban drifts: Mundane multiculturalism in outer London. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(12), 2016–2034. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.678875

- Wessendorf, S. (2014). Commonplace diversity: Social relations in a super-diverse context. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., & Sloan, L. (2017). Towards an ethical framework for publishing twitter data in social research: Taking into account users’ views, online context and algorithmic estimation. Sociology, 51(6), 1149–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517708140

- Wise, A. (2011). Moving food: Gustatory commensality and disjuncture in everyday multiculturalism. New Formations, 74(74), 82–107. https://doi.org/10.3898/NewF.74.05.2011

- Wise, A. (2013). Hope in a land of strangers. Identities, 20(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2012.752372

- Wise, A., & Noble, G. (2016). Convivialities: An orientation. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 37(5), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2016.1213786

- Wise, A., & Velayutham, S. (2009a). Everyday multiculturalism. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Wise, A., & Velayutham, S. (2009b). Introduction: Multiculturalism and everyday life Wise, A., Velayutham, S. eds. In Everyday multiculturalism (pp. 1–17). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Wise, A., & Velayutham, S. (2014). Conviviality in everyday multiculturalism: Some brief comparisons between Singapore and Sydney. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 17(4), 406–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413510419

- Yang, P. (2019). Psychoanalyzing fleeting emotive migrant encounters: A case from Singapore. Emotion, Space and Society, 31, 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.05.011

- Ye, J. (2016). Spatialising the politics of coexistence: Gui ju (规矩) in Singapore. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 41 (1), 91–103. 1965. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12107.

- Ye, J. (2017). Contours of urban diversity and coexistence. Geography Compass, 11(9), e12327–n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12327