ABSTRACT

This paper develops the notion of the technological unconscious by engaging with the geographic relationship between technology and the production of subjectivity. Drawing upon research with the Alternate Anatomies Laboratory in Australia, the paper advances this relationship through an empirical encounter with sonographic imaging. Contributing to conceptualisations of the ways technologies participate in unconscious activity, in this paper ultrasound imaging (sonography) is turned to as one way to think about the enunciation of subjectivity that assists the ultrasound technician in homing-in to particular signifying and a-signifying semiotic cues. Rather than siding with broad understandings of the technological unconscious, the paper articulates the production of specific processes of the technological unconscious via machinic enunciation, which reveals ways of rethinking human-technology relationships through infra-sensible semiotic operations.

Este artículo desarrolla la noción de inconsciente tecnológico al abordar la relación geográfica entre la tecnología y la producción de subjetividad. Con base en la investigación con el Laboratorio de Anatomías Alternativas en Australia, el documento avanza esta relación a través de un encuentro empírico con imágenes ecográficas. Contribuyendo a las conceptualizaciones de las formas en que las tecnologías están involucradas en la producción de un dominio de operación inconsciente expandido, en este artículo, se recurre a las imágenes de ultrasonido (ecografía) como una forma de pensar sobre la enunciación de la subjetividad que ayuda al técnico de ultrasonido a ubicarse en señales semióticas significantes y a-significantes particulares. En vez de alinearse con comprensiones amplias del inconsciente tecnológico, el artículo articula la producción de tipos específicos de inconsciente tecnológico como enunciación maquínica, que revela formas de repensar las relaciones humano-tecnológicas a través de las operaciones infra sensibles de la semiótica significante y a-significante.

Cet article approfondit la notion de l’inconscient technologique en étudiant le rapport géographique entre la technologie et la production de subjectivité. Il s’appuie sur la recherche avec l’Alternate Anatomies Laboratory (le laboratoire des anatomies alternatives) en Australie et présente ce rapport par le biais d’une rencontre empirique avec l’imagerie échographique. En contribuant à la conceptualisation des manières dont les technologies sont impliquées dans la production d’un domaine d’inconscient élargi de production, on se sert dans cet article de l’imagerie à ultrasons (l’échographie) comme moyen de réfléchir à l’énonciation de la subjectivité qui aide le manipulateur en échographie à localiser les indices de sémiotiques de signifiant et d’asignifiant. Plutôt que de se ranger aux côtés des grandes lignes de l’inconscient technologique, il articule la production de types spécifiques d’inconscients technologiques en tant qu’énonciation machinique, qui révèle des façons de repenser les rapports humains-technologie à travers les mécanismes infra-sensibles des sémiotiques du signifiant et de l’asignifiant.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

Consciousness in morphogenesis is not a superimposed principle, a deus ex machina, or a ‘ghost in the machine’. It is nothing other than form, or, rather, active formation, in its absolute existence.

(Ruyer, Citation2019, p. 161)

It is never an individual who thinks, never an individual who creates.

(Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 44)

Introduction

Recently, social and cultural geographers have developed how technologies are involved in producing an ‘expanded unconscious realm of operation’ (Dixon & Whitehead, Citation2008, p. 609), particularly in terms of urban advertising (Dekeyser, Citation2018), digital automation (Bissell, Citation2018), and through sensuous techniques and technologies of light (Zhang et al., Citation2019), scent (Kitson & McHugh, Citation2019) and sound (Duffy & Waitt, Citation2013). What this research mobilises is new ways of understanding how technologies participate in processes of ‘thinking’ in excess of the human, which includes the role of nonhuman matter as memory supports (Horton & Kraftl, Citation2012), nootropic modifications of the self (Rose & Abi-Rached, Citation2013), or the micropolitical work of habits in the constitution of agile movement (Dewsbury, Citation2015). Largely, this conversation has tended to emphasise how various technologies come to modify conscious and unconscious activity at the level of individuated subjects. My concern in this paper is to engage the technological unconscious as something that does not merely pertain to the capacities of individual subjects or objects, but of signifying and a-signifying subjectivation processes and components of subjectivity irreducible to individuated terms. In doing so, I develop the geographical notion of the technological unconscious in a different direction by turning to the concept of ‘machinic enunciation’.

Following Maurizio Lazzarato’s (Citation2014) and Felix Guattari’s (Citation2016) respective writing, by machinic enunciation I refer to a set of processes where the subject is produced through both sensible and infra-sensible powers of organisation. Operating on the genesis of subjectivity, rather than on individuated subjects, machinic enunciation directly concerns those subjectivation processes that structure conscious and unconscious behaviour prior to the human’s capacity for contemplation, intentionality, and self-reflection. Machinic, in this context, is not understood as ‘technological’ per se, but as an ‘assemblage’ that ‘is at once material and semiotic, actual and virtual’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 81). Following Lazzarato, machinic enunciation concerns the way these assemblages produce certain kinds of referents that enable the production of subjectivity: it is a ‘power of self-positioning, self-production’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 18) that occurs not merely through the representational semiotics (signifying forms of contemplation, intentionality, and conscious reflection), but through semiotic systems operating imperceptibly below the representations of the human subject. These processes of machinic enunciation, I contend, have certain implications for how we come to understand, on the one hand, the background operation of technologies and, on the other hand, the formalisation of thought into the category of the technological unconscious. However, unlike Freudian readings of the technological unconscious, which might entail a focus on the technological modification of certain ‘drives’ pertaining to an individuated subject, machinic enunciation understands the technological unconscious as something that acts most directly on infra-sensible, non-individuated qualities and ‘components of subjectivity’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 97 emphasis added).

To explore this articulation of the technological unconscious, I introduce an empirical engagement with ultrasound sonography to search for the radial artery blood vessel in my right forearm. Sonographic imaging is a particularly useful way to develop the concept of the technological unconscious for two reasons. First, sonography helps examine the substantialist distinction between the individuated body (human substance) and the technological object (nonhuman substance) by imaging in real-time an interactive relationship between human interiority and the exterior technological object. However, following Barad’s (Citation2007) exemplary analysis of the objectivation and subjectivation processes involved in sonographic imaging of the human body, rather than assume some ontological separation between human and technological matter, I focus on the sense that sonographic imaging is a process that is not easily resolved into individuated terms and, instead, disturbs the separation of the human and technological as distinct units of comprehension and locations of (un)conscious thinking. This is to understand the human body in terms of a ‘folding of the outside’ (Deleuze, Citation1988, p. 119) that, as Colls and Fannin (Citation2013, p. 1101) develop in the context of the mobilities of placental tissue, demands attention to the ‘varied materialities’ and processes at work in organising the relations between bodily interior and exterior world.

Second, sonography helps foreground the sense that technological systems have specific capacities to modify human behaviour in ways that might bypass the awareness of the human subject. Rather than treat the human as an individualised unit that contains a strong sense of intentionality and agency vis-à-vis digital technological systems (see, for example, Greenfield, Citation2015), I develop the idea that the powers to modify individual human behaviour have always been enacted by a host of infra-sensible forces that exceed it (Bonnet, Citation2017; Lazzarato, Citation2014). Lazzarato’s philosophy is especially instructive for the task of examining the technological modification of (so-called) human behaviour because, as with certain philosophical writings of Raymond Ruyer, Gilbert Simondon, Gilles Deleuze, and Felix Guattari, he is interested in understanding how human–technological relationships might be explained in terms of infra-sensible processes that prompt, direct, and lure human thought in certain directions. What is the human given its involvement with numerous other technologies that variously ‘think’ (nudge, remember, prompt, perceive, etc.) it? How do technologies modify what it means to ‘choose’, ‘select’, or ‘decide’ as a subject, and how might the conceptual language of machinic enunciation help grasp these processes? Addressing these questions through sonographic imaging, I explore how the technological unconscious, in a narrow sense, might be understood in terms of the operations of signifying and a-signifying semiotics acting at the limit between the human body and technological object.

Developing this argument, this paper comprises five sections. The first explores geographical research into the technological unconscious. The second introduces an alternative theorisation of the technological unconscious via Ruyer, Deleuze, Guattari and Lazzarato. The third develops the link between (a)signfying semiotics and a fieldwork encounter with ultrasonographic imaging. The fourth presents some of the reasons why sonographic imaging makes palpable a notion of the technological unconscious through machinic enunciation. The fifth concludes by reflecting on the significance of the technological unconscious for social and cultural geographies.

Geographies of the technological unconscious

In geography, the technological unconscious today operates both directly and indirectly as a concept for thinking about the interplay between human action and technologically mediated environments. Whilst geographers have often engaged with psychoanalytic literature and theories of the unconscious with a ‘degree of suspicion’ (Kingsbury & Pile, Citation2016, p. 6), nonetheless the technological unconscious continues to operate today in the work of social and cultural geographies in three key ways.

First, the technological unconscious has come to refer to the pervasive functioning of digital technologies in forming an operational backdrop to urban life. Thrift (Citation2004, pp. 185–7), for example, refers to the technological unconscious in terms of specific kinds of ‘performative infrastructures’ that, whilst operating below human awareness, shape and constrain the capacities of human action that is subject to specific forms of digital urban surveillance. Developing Thrift’s attention to the infrastructural, Kitchin and Dodge (Citation2014) refer to the technological unconscious in terms of the autonomous operations of code/space. Using the example of travelling through an airport, they note how the possibility for bodily movement and action becomes strongly reliant on the seemingly autonomous background relations of digital code. Developing this line of thinking, the relationship between the technological unconscious and digital infrastructure has been advanced through research into the ways online platforms operate within economies of attention capture (Wilson, Citation2015). In this context, the attention economy concerns not only the monetisation of attention but also the way the body is itself figured as part of the attentional infrastructure in digitally mediated environments. As Kinsley (Citation2010, p. 2784) details, the modification of a subject’s attention by digital infrastructures is to understand the technological unconscious as a form of ‘embodied cognition that is inherently worldly’. For Kinsley, this embodied mode of the technological unconscious not only participates in how a body acts, but also only modifies pre-emptively a subject’s anticipation and imagination of what technologies might be able to do in the future.

Second, the technological unconscious has been understood in psychoanalytic terms to articulate the communicative and spatial qualities of unconscious drives. This sense of the technological unconscious, broadly conceived, has been developed indirectly through a Lacanian ontology of psychic-material space (Blum & Secor, Citation2011). For instance, something of the technological unconscious is detectable in accounts of the ‘latent revolutionary potentials’ (Hardesty et al., Citation2019, p. 507) of Internet memes. In this case, such revolutionary potentials are made discernible in those moments a subject gets seized by the movement of a GIF whose political force is felt through the affective lure of its endless repetition.

Third, the technological unconscious is discernible in Deleuzian engagements with film and cinema. Clarke (Citation2015, p. 835) engages pejoratively with the notion of the unconscious through the technologies and techniques of the film Metropolis by examining the foreclosing of the future through the ‘neurotic fantasy’ of the Oedipal narrative. Differently, Lapworth (Citation2016, p. 28) develops the unconscious through director Yasujirō Ozu’s use of empty space that enacts different registers of time containing micropolitical powers to produce ‘indeterminate potentials of futures yet to come’.

Whilst sharing an interest with previous research approaching the technological unconscious to understand alternative registers of thought and experience – and particularly those relations between the ‘visible, barely visible and the imaged’ (Kingsbury & Pile, Citation2016, p. xix) – in this paper I develop the technological unconscious in a different direction by focussing on the subtle interplay of processes of machinic enunciation operating at the limit between the human body and the technological object. Despite being difficult to detect, such processes of machinic enunciation have expressive powers to modify human decision-making in specific ways. Inspired by geographical research rethinking the logics of subjectivation processes (Brice, Citation2021; Ruddick, Citation2017; Stark, Citation2017), including writing advancing conceptual understandings of the politics of molecular subjectivations (Bassett, Citation2021; Hynes & Sharpe, Citation2021; Roberts, Citation2012), this paper’s attention to the involvement of the technological unconscious in the production of subjectivity speaks to two key conversations.

Feminist theorisations of the body

First, the paper engages with the extensive work of feminist geographies and theories interested in rethinking the body through sonographic imaging. Feminist theoretical engagements with obstetric ultrasound, for example, have raised critical questions around the safety, rights, and (dis)empowerment of subjects in the process of imaging bodily interiors (Johnson, Citation2008). McNiven (Citation2016), notably, advances geographic understandings of bereavement by highlighting how the technological process of ultrasonography reproduces certain normative valuations of pregnancy loss. Here, the spatial and temporal mobilities of sonographic imaging, as well as the affective site of the Early Pregnancy Unit waiting room, are used to understand how the aesthetics and phenomenal experiences of sonographic imaging reproduce certain, and often diminished, valuations of pregnancy loss in medical spaces. Elsewhere, feminist scholars have questioned how the rise of 3D and 4D sonographic imaging has influenced material and discursive delineations of the body as ‘vital life’. Palmer (Citation2009) calls for a critical epistemology of foetal images in examining the way that 3D images become co-opted within abortion debates to evidence calls for a reduction in the gestational time limit. Taylor (Citation2008), meanwhile, engages with the rise of non-diagnostic 4D sonographic imaging (bonding scans) as something that creates specific forms of parental attachment. In part, this research considers how the process of using sonographic imaging implicates much wider productions of human behaviour and subjectivity, including the production of legal subjects, consumer behaviour, the objectification of uterine interiors, and the social (re)production of particular valuations of the subject (Petchesky, Citation1987).

Engaging with the way ultrasonography is understood as a process of subjectivation and objectification, Barad’s (Citation2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway is noteworthy for developing this technological process as something capable of producing certain subjects of surveillance and expertise. For Barad, the ‘piezoelectric transducer is the interface between the objectification of the fetus and subjectivation of the technician, physician, engineer, and scientist’ (Barad, Citation2007, p. 204). This focus on the subjectivation of expertise via sonographic imaging has a number of political consequences, as Ewalt (Citation2016, p. 139) notes, since it addresses the ‘complex entanglements of material-discursive forces that have arranged to differentially structure access to safe and legal abortions’.

Whilst informed by this effort to rethink individuated forms of human and technological agency through intra-action, in this paper I strike a different emphasis by focusing on how ultrasound technologies modify human behaviour through processes of machinic enunciation that operate with a degree of abstraction from both material-discursive forces and the lived experience of the body. In some part, this focus on processes of machinic enunciation takes its cue from feminist theorisations of the technological unconscious as something concerning pre-individual modulating powers of digital media (Clough, Citation2018), and a wider task of speculative philosophies to argue for pluriversal articulations of experience (Debaise, Citation2017). Considering the technological unconscious as one way of approaching pre-individual and speculative articulations of experience, I focus on understanding how conscious and unconscious modes of thought are produced and affected by technological operations of ultrasound – operations that, as Clough (Citation2018, p. 25) notes, may not be detectable discursively but operate ‘above and below the speaking subject of conscious and unconscious representation’.

Nonhuman agency and technological affects

Second, and relatedly, this approach to the technological unconscious foregrounds the subtle operation of technological processes that modify human behaviour in ways that are not necessarily made perceptible at the level of the subject (Roberts, Citation2012; Sellars, Citation2015). In geography, research into the imperceptible powers of technologies to modify human behaviour has been developed in work engaging questions of nonhuman agency and technological affects. Ash (Citation2018) has advanced geographical understandings of specific powers of technologies to affect human behaviour through the concept of ‘phase time’. Drawing on Stiegler’s (Citation1998) notion of hypomneses, phase time concerns the mnemetic character of technologies to exteriorise the human through the splitting of knowledge and memory via technological supports. Although often bypassing human perception, the hypomnetic character of technology, which includes various processes of informational exteriorisation of human memory (language, hard drives, etc.), exert specific affective powers when they combine to intensify, perhaps uncomfortably, a subject’s anticipation of the future (Ash, Citation2018, pp. 77–100). Likewise, Amoore (Citation2018) has advanced the notion of the cloud as one way to conceptualise the imperceptible operations of digital technologies. Articulating multiple ways cloud computing can be said to modify the subject’s capacity to think and act, for Amoore (Citation2018, p. 8) the cloud takes on a geopolitical import in the way unfelt operations of digital data become ‘reterritorialized as an intelligible and governable entity’. Elsewhere, and intersecting geographical research that emphasises the material situatedness of technologies (Barratt, Citation2011; Bissell, Citation2018), nonrepresentational geographies have focused on articulating the automaticity of human-technological action as a form of nonhuman intelligence. Referring to the surprising capacity of a subject to skilfully type on a computer without being able to consciously recite the full QWERTY keyboard, Dewsbury (Citation2015, p. 45fn5 citing Connolly, 2010, p. 17) develops the notion of ‘biological rewiring’ to articulate how the materiality of the human body can become capacitated to engage in technological habits and ‘modes of living without thinking’.

In conversation with emerging work intersecting nonhuman agency, technological affects, and the technological unconscious, what I want to emphasise uniquely in this paper is the role of a-signifying semiotics in contributing to how geographers come to understand the technological unconscious. Notwithstanding some notable exceptions (Doel & Clarke, Citation2019; Gerlach & Jellis, Citation2015; Williams, Citation2020; Williams & Burdon, Citation2022), the notion of a-signifying semiotics has been largely overlooked by social and cultural geographers, and yet this focus provides a unique entryway for thinking about technological processes operating below human perception and experience. For Lazzarato (Citation2014, p. 84), who draws extensively on the writing of Deleuze and Guattari, signifying semiotics describe a system of representational signs that ‘refer to another sign by way of representation, consciousness, and the subject’. Signifying semiotics (language, images etc.) can thus be understood as any system of representation that operates directly at the sensible, self-reflexive, and consciousness level of an individuated subject. Differently, a-signifying semiotics operate infra-sensibly below the level of subjective representation. A-signifying semiotics thus ‘slip past’ the individuated subject (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 80) since they do not concern the movement of signs but certain processes that bypass subjective perception and consciousness. As Lapoujade (Citation2019, p. 7) helps clarify, at the a-signifying level the notion of the unconscious poses the question: ‘What is needed for signs to lead a consciousness to produce other signs, actions or thoughts in connection with the first ones?’. In other words, a-signifying semiotics – including, but by no means limited to ‘[s]tock market indices, unemployment statistics, scientific diagrams and functions, and computer languages’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 80) – exhibit an operational rather than representational quality: they concern functions that work directly to multiply ‘the power of a “productive” assemblage’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 40), rather than working through the actions carried out by individuated subjects.Footnote1 As Williams (Citation2020, p. 12) develops in the context of geographical engagements with style, as a set of processes involving a degree of abstraction from the human, a-signifying semiotics tend to ‘cut across centralised systems for organising and apprehending the social’. No longer operating at the level of subjectivity, a-signifying semiotics:

mobilize partial and modular subjectivities, non-reflexive consciousnesses, and modes of enunciation that do not originate in the individuated subject. (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 89)

Hence, insofar as it concerns partial and modular components of subjectivity, ‘[a]-signification is essentially machinic’ (Genosko, Citation2008, p. 15) since a-signifying semiotics involve assemblages where human consciousness and activity would no longer have any ontological prominence. Crucially, whilst Lazzarato does not advocate splitting signifying from the a-signifying into two bifurcated realities, he does insist on the need for a certain attention to the machinic operation of a-signifying semiotics that too often get overlooked in social scientific accounts of the production of subjectivity. It is for this reason that for Lazzarato (Citation2006) ‘television, science, music’ can be understood as forms of a-signifying semiotics, rather than only as signifying semiotics, insofar as they are taken not merely as something ‘routed through a signification or a representation’ but as ‘sign production machines’ acting directly on the body to ‘trigger an action–reaction sequence’. Thus, aside from no longer being routed through individuated subjects, for Lazzarato a-signifying semiotics also pinpoint those processes wherein the movement of signs come to function in a wider machinic system that trigger conditions for acting and evaluating as a subject prior to a moment of decision.

Rethinking the technological unconscious via machinic enunciation

In theorising the technological unconscious in relation to signifying and a-signifying semiotics, I draw upon on a genealogy that exists in the writing of Ruyer, Deleuze, Guattari and Lazzarato that conceptualises conscious and unconscious ‘thought’ without relying on a transcendental principle that would separate processes of thinking into human (living) and technological (non-living) being. Referring to a number of examples from biological morphogenesis, Ruyer (Citation2019, p. 167) conceives of the unconscious not as an individuated property of a human body, an individual cell, or a collectively produced set of drives, but as a transpatial process of ‘active formation’ (p. 161). To conceptualise the unconscious in terms of processes of active formation, what Deleuze (Citation1998, p. 63) refers to as an unconscious ‘of mobilization’, is to articulate how processes of thinking might be understood ontogenetically across multiple bodies rather than being grounded in an individuated substance (the brain, the body, etc.). For Guattari, who was well-aware of Ruyer’s writing on embryogenesis, understanding this ontogenesis of thought means attending to varied forms of the unconscious produced through different spaces and materials, since:

… one never deals with the Unconscious with a capital U, but always with n formulae for unconsciouses, varying according to the nature of the semiotic components that connect individuals to one another: somatic and perceptual functions, institutions, spaces, equipment, machines, etc. (Guattari, Citation2016, p. 6)

Taking up Guattari’s task of theorising multiple components of unconsciouses, Lazzarato (Citation2014, p. 38) refers to the unconscious as something ‘manufactured’ within Capitalism through a ‘pre-personal (pre-cognitive and preverbal)’ and ‘supra-personal level’ that produce ‘certain modes of perception and sensibility’. Crucial for Lazzarato (Citation2014) is the sense that the unconscious is no longer tied to individuated notions of the personological or familial, but is produced through ‘digital, communicational, media’ technologies (p. 56) that modulate human behaviour in ways that bypass the subject’s perceptive syntheses.Footnote2 This notion of the unconscious as something manufactured via certain media and technologies, what Lazzarato (Citation2015, p. 179) elsewhere refers to as ‘“incorporeal” instruments of governance’, concerns not individuated subjects but components of subjectivity that are operated on by signifying and a-signyfying semiotics.

To conceptualise the unconscious as something that produces specific modes of perception and sensibility, through the operations of signifying and a-signifying semiotics of technologies and digital media, is not to say these semiotic processes are qualities of technological objects. Indeed, part of the reason that Guattari and Lazzarato are both careful to insist that machinic enunciation cannot be reduced to a technological process is to avoid falling into the trap of technological determinism. Insofar as it concerns the production of conscious and unconscious behaviours via the production of subjectivity, machinic enunciation involves technological processes but is not determined by them since it acts precisely on the production of subjectivity through assemblages that engage technologies as ‘components parts’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 82). As Genosko explains

Guattari did not reduce his machines to technical devices; yet, his repeated description of how a-signifying semiotics trigger processes within informatic networks … makes it clear that we are dealing with a complex info-technological network.

(Genosko, Citation2008, p.15)

That is, there is a technological component of machinic enunciation – what Genosko (Citation2008, p. 15) describes after Guattari as a ‘complex info-technological network’ – which provides one way to explicitly analyse the technological modification of unconscious behaviour without merely suggesting that technologies are the ‘source’ of the production of unconscious behaviour.

(A)Significations of the technological unconscious

One way to explore how the technological unconscious can be understood through the machinic enunciation enacted through signifying and a-signifying semiotics is to turn to Lazzarato’s (Citation2014, pp. 96–97) discussion of the stock market trader. Critical to this example is the idea that the actions of the trader must involve processes of thought and decision-making that vastly exceed the figure of the individuated subject. As a subject carrying out market decisions, the trader enters into a system of semiotics with its own powers of subjectivation. In this case, these powers are enacted through the expressive thresholds of trading room data and diagrams that immerse the subject in the act of making decisions about price setting. Crucially, these diagrams do not simply determine the thought and decision-making of an individuated subject, but act on ‘memory, attention, perception’ components of subjectivity (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p.96–97)Footnote3 - components that take expression via the representation of information (signifying semiotics), and an info-technological network that has its basis in the functioning of much wider system (a-signifying semiotics).

How, then, are we to understand how signifying and a-signifying semiotics operate in this theorisation of the technological unconscious as machinic enunciation? Here Lazzarato is quite instructive:

That signs (machines, objects, diagrams etc.) constitute the focal points of proto-enunciation and proto-subjectivity means that they suggest, enable, solicit, instigate, encourage, and prevent certain actions, thoughts, affects or promote others. (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 97 original emphasis)

Following Lazzarato’s logic, technological processes modify the production of subjectivity only insofar as they produce signs that act to affect and enunciate subjectivation. As with Dewsbury’s (Citation2015) discussion of the computer keyboard, what is highlighted in this example is the sense that technological interfaces often only partially enter into the consciousness of the subject, and more often operate at the level of proto-subjectivity and proto-enunciation that engage in a partial subjectivation. To understand how a subject ‘types’, ‘thinks’, or ‘decides’ in using digital technologies, what takes priority for Lazzarato is less the action of signifying signs, but rather a specific reliance of the subject on (a)signifying processes of proto-subjectivity and proto-enunciation – what I refer to as the technological unconscious – that emerges in the act of using technological infrastructures.

Developing this reading of the technological unconscious further, at this point I introduce an empirical encounter with sonographic imaging. This empirical account pays close attention to nonhuman processes informing an act of sonographic imaging – a procedure that, at first sight, may seem entirely directed by the expertise of the ultrasound technician. However, building on research that evokes nonhuman agencies and modifications of the human body as a qualitative ‘method’, including sensory methods with digital technologies (Pink et al., Citation2019), non-representational engagements with digital spaces (Shepherd, Citation2019), and autoethnographic methods utilising the researcher’s body in medical spaces (Ellingson, Citation2006), in this empirical vignette I evoke something of the power of human-technology semiotic relations established in imaging bodily interiors (Sellars, Citation2015). Whilst acknowledging some of the dangers associated with writing empirically about my body with a degree of abstraction from embodied meaning (Ellingson, Citation2006), the aim in doing so is to consider how the technological unconscious is enacted by subtle machinic enunciating processes between the human–technological interface that often bypass the experience of the individuated subject.

Thinking the technological unconscious with sonographic imaging

On Tuesday 19 April 2016 I met Nina Sellars in a medical studies laboratory at the University of Western Australia. This is not the first time I have met Nina; I have spent the last three weeks following her work as an artist and research fellow at the Alternate Anatomies Laboratory in Perth. Today, however, is the first time I have met with her friend and colleague Stuart Bunt – a neuroscientist and anatomist who has recently acquired a medical ultrasound machine. Stuart, excited to try out his department’s new device, invited us to join him in exploring some of its capabilities.

Stuart immediately turns to the ultrasound display and reaches for one of the smaller, rectangular transducers. I, meanwhile, sit down to roll up my sleeve and begin applying conduction gel along the underside of my right forearm.

I watch as Stuart turns his back to focus on the ultrasound display, his left hand holding the transducer firmly against my wrist. As he explains, different transducers are used for different kinds of imaging: here it is a VFX13-5 transducer suitable for imaging muscle, bone and blood vessels inside the body with a depth of up to 6 cm. The VFX13-5 is broad-spectrum and can be used for a variety of 2D imaging functions. Over the next few minutes Stuart remains mostly fixed to the ultrasound display in his effort to image the blood vessel.

As either object of, or subject directing, an ultrasound machine, the human inhabits abstract realms of technological mediation. Grey muscle fibre, for instance, is the product of a particular transduction of form: from ultrasonic wave forms (sound), to the perceptible light, and colour of the image. Mediated between these iterative undoings of the bounded individual (Barad, Citation2007), consciousness is defracted between matter and machine; something about the conventional separation between interiority and exteriority is obliterated.

For the human body to emerge as an object of medical research, a series of individuations must occur: the arm, the cell, the blood vessel must emerge as objects of imaging functions. My right arm is projected and re-configured, and then abstracted and re-mapped onto certain forms of value. Produced on screen is an image of the body that is deterritorialised from habituated durations of perceptibility (Guattari, Citation2016).

Fine tuning an image on an ultrasound machine is much like a camera. Using a trackball the contrast, brightness, depth of field and focus all require some adjustment to specificity of this body. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that rendering a particular image of the body does not come easy. What is required is a process of homing-in to the machine–subject ensemble. By homing-in the technician is on the lookout for specific cues: the murmuring sound of a pulse, or a flash of colour. In doing so, the technician must partly surrender perception, judgment, and evaluation over to technological device that appears with a whole system of pre-set configurations and forms of standardisation – including, but not limited to, transducer depths of field for imaging muscle, bone, and organs. In other words, the technician emerges with the evaluations of these semiotics systems.

Blue red pulses indicate a blood vessel has been found, one that mimics a rhythm initiated at the genesis of the organism (Ruyer, Citation2019).

Enunciative powers of the technological unconscious

As a process that foregrounds various relations between the human and the technological, there are a number of reasons why sonographic imaging helps make palpable the technological unconscious modification of human behaviour through machinic enunciation. In setting out these reasons, the effort to think about the technological unconscious through sonographic imaging becomes engaged with a wider questioning of how this focus understands the actions of ultrasound technicians and technologies in terms of the interplay of signifying and a-signifying semiotics.

The first of these reasons concerns the relationship between thought and the enunciative qualities of sound. Intersecting Kitchin and Dodge’s (Citation2014, p. 123) engagement with computer hardware as an ‘unconscious layer for manipulating digital realities’, there is a sense that the physical act of using an ultrasound machine involves certain operational qualities that are not easily reduced to the figures of the individuated subject or object. As with the machinic subjectivity of the stock market trader (Lazzarato, Citation2014, pp. 96–97), the process of creating sonographic images demands a specific immersion of the technician within a technological system exhibiting a mixture of different semiotic processes. These semiotic processes – such as the 2D-image diagram, the pulse rate data, and focus point co-ordinates on the ultrasound display – convert material qualities of a body’s interior into ‘diverse flows of information’ (Lazzarato, Citation2014, p. 97); that is, the sound and rhythm of the pulse directly informs subjective evaluations about how the image is and could be displayed. For the task of imaging a blood vessel, the audible sound emitted from the display speakers is particularly useful in guiding the transducer-holding-hand of the technician to follow the murmur of a pulse. In thinking through these audible pulses, the task of imaging becomes one of tracking the differing rhythms and intensities of sound. Prompted by these different sensory cues, the difficult act of imaging the interiority of the body – in this case of homing-in on a blood vessel – becomes facilitated in the act by the perceptible sounds of the machine that help produce subjects with a heightened sense of immediacy to the present (Ash, Citation2018).

Yet the task of homing-in on a sound is far from seamless: the challenge for the technician is to grip the transducer still in one hand whilst, at once, focussing their vision on the display screen. At the same time, the technician subject must also use another hand to guide the trackball of the ultrasound machine to alter the image focus according to the audible sound and rhythm of the pulse rate. As something that guides the technician, or more precisely components of the technician’s subjectivity, the transduction of ultrasound waves into audible sound can be understood, after Lazzarato and Guattari, as an event of proto-enunciation. This is because the audible sound of the pulse takes on a referential power that guides the technician towards the (ab)normal rhythms of a particular blood vessel. Linking to recent engagements in geography to attend to the rhythms and ‘styles of phonographic practice’ that enact specific relationships between the listener and technological apparatus (Gallagher & Prior, Citation2014, p. 277), this transduction produces subjective components of the technician in its structuring of perception through a series of alterations in sound (Sellars, Citation2015). The structuration of the technician, therefore, occurs at the level of signifying semiotics (searching and focussing using the audible sound of the machine pulse) and a-signfying semiotics (the nudging, luring and prompting produced through alterations of sound only just detectable by the subject).

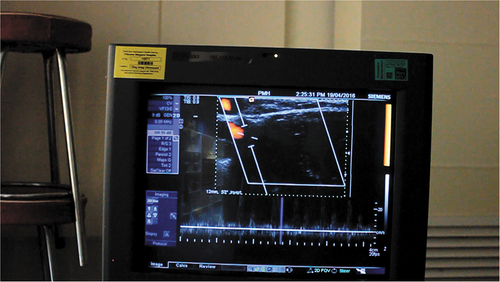

The second reason concerns the relationship between thought and vision. To examine this relationship it is worth here specifying some of the processes – technological and semiotic – involved in producing an ultrasound image. As a medical device designed to image organic matter, the ultrasound machine in this case consisted of a number of identifiable components, including: a trackball, a set of transducers or probes (in this case a VFX13-5 transducer), a display monitor, computer, printer, as well as a keyboard and image function controls (such as a contrast knob, pulse control settings, and shortcut keys). In addition to these physical components, in this case the machine was also made up of various software components displayed via the image monitor (). This interface can be broadly divided into three parts: (1) a control panel containing image functions and presets, (2) a spectrogram at the bottom of the screen relaying the frequency of a pulse rate, and (3) a 2D image in the top half of the display presenting a given cross-section of a body. Considering how sonographic imaging might be understood in terms of machinic enunciation, this interface contains certain notable imaging functions, including: contrast, sonographic image frequency (brightness), orientation, and zoom. Insofar as they concern the alternation of the perceptible qualities of a sonographic image, the components and interface of the ultrasound machine can be analysed in terms of signifying semiotics understood through certain expressive representational signs. One example includes the way the transducer acted as a focal point organising the relationship between my body as a site of measurement, and the subjectivation of the technician as a skilled practioner (Barad, Citation2007). In organizing this relationship, the transducer became formative, albeit partially, of a subtle bodily orientation that directed Stuart’s vision in certain directions. Without directly looking at the transducer, Stuart was directly guided by a set of semiotic cues - including the colours and textures on the ultrasound monitor. In attending to these cues, the transducer was not the focal point for the technician’s vision – which was fixed on the sonographic display – but acted as a way for the technician to ‘think-feel’ through the technological system in evaluating whether or not to continue imaging certain areas of my arm.

Figure 1. Homing-in. This image depicts something of the process of imaging a blood vessel using an ultrasound machine. The rounded yellow and Orange shapes are the colour differentials of two blood vessels that have been brought into focus between the two lines of the pointer. Source: author’s own.

Put in terms of signifying semiotics, what is notable is the way the ultrasound transducer helps produce certain kinds of vision, such as through a reliance on specific depths of field. For example, the VFX13-5 transducer has a depth of field of 6 cm that can be used for a number different medical image processes, including both exploratory imaging examinations and pedagogic practices. In other cases, where a particular transducer is selected with a shallow or deep depth of field – depending on whether the technician wants to image, for example, a human wrist or a hip bone – the transducer is significant in the kinds of images it filters out. In filtering out certain image resolutions and depths, the transducer is formative not only in the act of producing sonographic images, but also in evaluating and selecting – at the level of signifying semiotics – the informational composition of an image. The process of selecting a particular transducer is here significant in the way it intervenes in the production of a component of subjectivity of the technician. The transducer can thus be understood to help partially produce a ‘critical’ subject imbued with a sense of assurance that an image produced has been carefully constructed through the specialised process of selecting a particular transducer. In this sense, the transducer might be said to participate in a subtle process of decision-making, what Bonnet (Citation2017, p. 10) refers to as a ‘protocol of representation’, through which something like the ‘critical or ‘skilled’ subject-component of the ultrasound technician is able to emerge.

Insofar as they concern the alteration of the imperceptible qualities of a sonographic image, the components and interface of the ultrasound machine can also be analysed in terms of a-signifying semiotics with the power ‘to move us where conscious meaning falters’ (Williams & Burdon, Citation2022, p. 10). In this instance of medical sonographic imaging, a-signifying semiotics – those expressive ‘signs of signs’ (Doel & Clarke, Citation2019, p. 28) – include various image presets available within the ultrasound interface. Image presets, in this case located in a blue drop-down panel on the left of the image display, are software functions that provide pre-given imaging ratios of contrast and frequency of ultrasound radiation. Preset ratios are useful for technicians insofar as they provide standardized image resolutions for certain parts of the body – such as the brain, the abdomen, muscle fibers (), and so on. On one level, image presets are a-signifying in the way that they act to automatically produce certain types of images for particular parts of the body, but where the operational decision-making that is formative in producing these images emerges through an enunciative process that is removed from the signifying semiotics available to the ultrasound technician. These a-significations have a degree of separation from the technician because the operational function that matches a certain image preset ratio to a certain part of the body – that is, to determine what a technician does and does not ‘see’ – does not have its basis in the decision-making of the individuated subject of the technician, but instead emerges out of a much wider info-technological network (Genosko, Citation2008). The unconscious operations of this info-technological network can be thought about in terms of an informational assemblage that consists of – among other things – legal apparatuses, medical research, ethical standards, and the decision-making carried out during manufacturing of medical equiptment. Linking to Sellars’ (Citation2015) critical engagement with the political production of the ‘anatomical body’ through technologies and techniques of light, this a-signifying quality of sonographic imaging has an operational quality in (re)producing certain ideas about the anatomical body that is assumed to be rendered ‘visible’ for observation through technologies and techniques of sound. This question of the visibility of the body through ultrasound is not just about what parts of the body are technically able to be imaged, but about the way a-signifying semiotics come to decide which bodily matter (muscle, fat, stem cells, etc.) should or should not be imaged prior to act of ‘seeing’ by the machine–technician ensemble.

Figure 2. (A)significations. This image depicts the use of a shallow depth of field to image muscle fibres. Source: author’s own.

The third, and final, reason concerns the sense that sonographic imaging demands the technician is superseded, to some degree, by the actions of a-signifying semiotics. Acting as a skilled subject, the technician establishes certain focal points that carry out specific functions through the use of colour differentials superimposed on the ultrasound display (). To produce colour differentials – the red/yellow or red/blue shapes in a sonographic image – the ultrasound technician must use the Doppler setting on the ultrasound machine. The Doppler setting refers to a digital program installed on medical ultrasound machines to allow technicians to observe the velocity and direction of blood flow as a difference in colour. The red/blue or red/yellow shape overlaying the sonographic image indicates a movement of blood towards the transducer, suggesting that this blood vessel is located in an artery (moving away from the heart) rather than a vein (moving back towards the heart). Put in terms of machinic enunciation, the Doppler effect can be understood in terms of signifying (shape, colour, velocity) and a-signifying semiotics (computer code). This semiotic system triggers a process wherein a flow of blood is interpreted as having a determinable direction that is revealed through a colour-codified image, the outcome of which is to affect the perception of the technician as they come to recognise a difference in colour as an anatomical difference – such as red/yellow for arteries or blue/green for veins. As an effect of signifying and a-signifying semiotics, the Doppler setting thus renders the blood vessel palpable for thought and evaluation: it becomes a site of partial subjectivation that modifies components of the technician’s subjectivity (i.e. perception) in the act of using the device (is that the ‘correct’ shape? Is this the ‘correct’ velocity and direction of blood flow? Is the rhythm ‘regular’?).

In approaching the Doppler effect in terms of machinic enunciation, one political point here is that it is not enough to consider how the technological unconscious acts on individuated subjects since it also concerns signifying and a-signifying semiotic processes that bypass the subject’s perceptive syntheses. This amounts to a different way of thinking about the production of evaluative decision-making through technological processes, which tend to be shaped by processes of subjectivation that are not easily explained through the figures of the individuated subject and object. As one way to consider the relationship between the human body, technological process, and proto-subjectivation, sonographic imaging operates through an interplay of signifying (curves, diagrams, data) and a-signifying semiotics (preset imaging functions) that variously modify, nudge, and lure the direction of thought enacted through human-technology relationships.

Conclusion

Contributing to research that emphasises the imperceptible powers of technologies to modify human behaviour, and particularly social and cultural geographical engagements with bodily interiors (Colls & Fannin, Citation2013; McNiven, Citation2016) and nonhuman agency (Amoore, Citation2018; Ash, Citation2018), in this paper I develop a reading of the technological unconscious in terms of enunciating powers of signifying and a-signifying semiotics. If in geography the technological unconscious has come to refer to the way infrastructures modify the subject through anticipatory logics of pre-emption (Kinsley, Citation2010; Thrift, Citation2004), my focus here is to develop this line of thinking by articulating how signifying and a-signifying semiotics participate in these processes at the level subjectivation and the production of systems of evaluation through machinic enunciation. On one level, this articulation of the technological unconscious highlights the underexplored role of signifying and a-signifying semiotics in explaining how human action becomes modified, albeit subtly, through the interplay of the body and technological processes (Lazzarato, Citation2014). This focus on signifying and a-signifying semiotics to apprehend the technological unconscious modification of thought is significant, as Antonioli (Citation2019) observes, because it foregrounds not the interior familial qualities of individuated subjects and objects but an exteriority of bodily relations, gestures, and institutional connections that act infra-sensibly on the human. Through an empirical encounter with sonographic imaging, this paper argues that technologies do not simply act on individuated subjects but on processes of subjectivation and components of subjectivity, which modify the possibilities for human action prior to a moment of decision-making.

In a medical setting, the impact of signifying and a-signifying semiotics is detectable in the way that the human body becomes objectified through certain diagnostic processes. As an object of medical technologies, the anatomical body emerges as ‘a spectrum that is divided by artificial boundaries and categories, and thus itself forms a record of the qualities and histories of our measuring devices’ (Sellars, Citation2015, p. 62). Following Sellars, the anatomical body would not simply be an organismic entity but also something made up of a series of imagined categories and units – such as the ‘organ’ – produced through medical imaging technologies that render the body open to certain kinds of abstraction. Enunciated by medical imaging technologies, these medical units might be understood as signifying semiotics that act to enunciate a particular notion of the body open to certain kinds of diagnostic decisions. In the case sonographic imaging, the interplay of signifying and a-signifying semiotics, acting both sensibly (sound, colour, etc.) and infra-sensibly (Doppler effect, image preset ratios etc.), at once raise critical questions around what is revealed or hidden in the process of producing sonographic images (Taylor, Citation2008). What unites these different processes of abstraction is the problem of how medical sonographic imaging encourages the production of a ‘critical’ or ‘knowing’ technician subject – a subject that emerges through the seeming reliability of a-signifying and signifying semiotic systems. Linking to research theorizing collective subjectivation besides pre-given individuated models (Brice, Citation2021), this problem of medical imaging can be understood in relation to a recent tendency within the social sciences to invoke an idea of the subject – as a user of technological systems – as an individualised unit housing agency and intentionality, rather than attending to the ways this agency is also suffused within the act of using technological systems. Instead, what is revealed through an attention to the machinic enunciation of the ultrasound technician is the inadequacy of asserting individualised notions of agency and intentionality given the subject’s emergence in signifying and a-signifying semiotics.

If technological processes modify subjectivation through the participation of signifying and a-signifying semiotics (Lazzarato, Citation2014), then clearly this notion of the technological unconscious also reveals certain ethico-political challenges. As Guattari reminds us, what is at stake in surrendering subjective thought and action to the proto-subjectivations and proto-enunciations of machinic enunciation is the danger that:

… a central signification will irradiate all local significations, such that nothing … will be able to escape from the signifying contamination that constitutes an empty humanity as centre of the world, perpetually referring to systems of redundancy and self-enclosed hierarchies. (Guattari, Citation2016, p. 183)

Which is to say there is a danger that a machinic assemblage of signifying and a-signifying semiotics might constrain the production subjectivity around certain infantilizing systems of redundancy. In the context of sonographic imaging, responding to this problem might mean becoming more attentive to how the figures of the ‘healthy’ or ‘natural’ anatomical body becomes produced through certain technologies of enunciation, which constrain the possibilities for the emergence of other thoughts, behaviours and evaluations that have their basis in an infra-sensible, ‘un-presentable element that remains immune to perceptual neutralization’ (Bonnet, Citation2017, p. 91).

Acknowledgments

This paper was improved by the comments of two anonymous reviewers and the editorial guidance of Prof David Bissell and Dr Elizabeth Straughan. Special thanks to Dr Nina Sellars at the Alternative Anatomies Laboratory at Curtin University in 2016 for facilitating this visit, and to Prof Stuart Bunt of the University of Western Australia for acting as an ultrasound technician to facilitate this work. A version of this paper was presented at the AAG in Washington DC in 2019 in the session The Unconscious Before and After Freud and Lacan kindly organised by Dr Andrew Lapworth and Dr Scott Sharpe. Thanks to Mat Keel, Linköping’s P6 seminar group, as well as friends and colleagues in Bristol for comments on an earlier version of this writing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Thus, a-signifying semiotics operate ‘dividually,’ rather than individually, since they bypass the need for an individuated subject as an agent of power (see Lazzarato, Citation2014, pp. 26-27).

2. This focus on the technological strikes a different emphasis to Guattari’s (Citation2011) notion of the ‘machinic unconscious’, which resists relating the ‘machinic’ with the ‘technological’ (see Genosko, Citation2008).

3. Following Guattari, Lazzarato’s use of the term ‘components of subjectivity’ does not describe an individuated unit belonging to a fully individuated subject. As Guattari notes: ‘it is not a matter each time of the same subject, who would miraculously make messages, decisions and laws pass from one component to another. A little subject in my head, like a minuscule manager on the top floor of a building!’ (Guattari, Citation2016, p. 221). Instead, these components are perhaps closer to what Guattari (Citation2016, p. 220) refers to as ‘subjectivation functions’ that operate without any need for an individuated structure.

References

- Amoore, L. (2018). Cloud geographies: Computing, data, sovereignty. Progress in Human Geography, 42(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516662147

- Antonioli, M. (2019). Mapping the unconscious. In T. Jellis, J. Gerlach, & J. D. Dewsbury (Eds.), Why Guattari? A liberation of cartographies, ecologies and politics (pp. 34–44). Routledge.

- Ash, J. (2018). Phase media: space, time and the politics of smart objects. Bloomsbury.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Barratt, P. (2011). Vertical worlds: Technology, hybridity and the climbing body. Social & Cultural Geography, 12(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.574797

- Bassett, K. (2021). Badiou and Lazzarato on the politics of the event: formalism or vitalism? Theory & Event, 24(3), 650–674. https://doi.org/10.1353/tae.2021.0038

- Bissell, D. (2018). Automation interrupted: How autonomous vehicle accidents transform the material politics of automation. Political Geography, (65) , 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.05.003

- Blum, V., & Secor, A. (2011). Psychotopologies: Closing the circuit between psychic and material space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(6), 1030–1047. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11910

- Bonnet, F. (2017). The infra-world. Urbanomic.

- Brice, S. (2021). Trans subjectifications: Drawing an (Im)personal politics of gender, fashion, and style. GeoHumanities, 7(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2020.1852881

- Clarke, D. (2015). Metropolis, blood and soil: The heart of a heartless world. GeoJournal, 80(6), 821–838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-015-9649-z

- Clough, P. (2018). The user unconscious: On affect, media, and measure. University of Minnesota Press.

- Colls, R., & Fannin, M. (2013). Placental surfaces and the geographies of bodily interiors. Environment and Planning A, 45(5), 1087–1104. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44698

- Debaise, D. (2017). Speculative empiricism: Revisiting whitehead. Edinburgh University Press.

- Dekeyser, T. (2018). The material geographies of advertising: Concrete objects, affective affordance and urban space. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 50(7), 1425–1442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18780374

- Deleuze, G. (1988). Foucault. University of Minnesota Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1998). Essays critical and clinical. Verso.

- Dewsbury, J. D. (2015). Non-representational landscapes and the performative affective forces of habit: From ‘Live’ to ‘Blank’. Cultural Geographies, 22(1), 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014561575

- Dixon, D., & Whitehead, M. (2008). Technological trajectories: Old and new dialogues in geography and technology studies. Social and Cultural Geography, 9(6), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360802320560

- Doel, M., & Clarke, D. (2019). Through a net darkly: Spatial expression from glossematics to schizoanalysis. In T. Jellis, J. Gerlach, & J. D. Dewsbury (Eds.), Why Guattari? A liberation of cartographies, ecologies and politics (pp. 19–33). Routledge.

- Duffy, M., & Waitt, G. (2013). Home sounds: Experiential practices and performativities of hearing and listening. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(4), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2013.790994

- Ellingson, L. (2006). Embodied knowledge: Writing researchers’ bodies into qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(2), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305281944

- Ewalt, J. (2016). The agency of the spatial. Women’s Studies in Communication, 39(2), 137–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2016.1176788

- Gallagher, M., & Prior, J. (2014). Sonic geographies: Exploring phonographic methods. Progress in Human Geography, 38(2), 267–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513481014

- Genosko, G. (2008). A-signifying semiotics. Public Journal of Semiotics, 2(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.37693/pjos.2008.2.8822

- Gerlach, J., & Jellis, T. (2015). Guattari: Impractical philosophy. Dialogues in Human Geography, 5(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615587787

- Greenfield, S. (2015). Mind change: How digital technologies are leaving their mark on our brains. Random House.

- Guattari, F. (2011). The machinic unconscious: Essays in schizoanalysis. Semiotext (e).

- Guattari, F. (2016). Lines of flight: For another world of possibilities. Bloomsbury.

- Hardesty, R., Linz, J., & Secor, A. J. (2019). Walter Benja-Memes. GeoHumanities, 5(2), 496–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2019.1624188

- Horton, J., & Kraftl, P. (2012). Clearing out a cupboard: Memory, materiality and transitions. In O. Jones & J. Garde-Hansen (Eds.), Geography and memory (pp. 25–44). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hynes, M., & Sharpe, S. (2021). Cosmic subjectivity: Guattari and the production of subjective cartographies. Area, 53(2), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12695

- Johnson, E. (2008). Simulating medical patients and practices: Bodies and the construction of valid medical simulators. Body & Society, 14(3), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X08093574

- Kingsbury, P., & Pile, S. (2016). Introduction: The unconscious, transference, dives, repetition and other things tied to geography. In P. Kingsbury & S. Pile (Eds.), Psychoanalytic geographies (pp. 1–49). Routledge.

- Kinsley, S. (2010). Representing ‘things to come’: Feeling the visions of future technologies. Environment and Planning A, 42(11), 2771–2790. https://doi.org/10.1068/a42371

- Kitchin, R., & Dodge, M. (2014). Code/space: Software and everyday life. MIT Press.

- Kitson, J., & McHugh, K. (2019). Olfactory attunements and technologies: exposing the affective economy of scent. GeoHumanities, 5(2), 533–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2019.1644961

- Lapoujade, D. (2019). William James: Empiricism and pragmatism. Duke University Press.

- Lapworth, A. (2016). Cinema, thought, immanence: Contemplating signs and empty spaces in the films of Ozu. Journal of Urban Cultural Studies, 3(1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1386/jucs.3.1.13_1

- Lazzarato, M. (2006) Semiotic pluralism and the new government of signs. Transversal. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from http://eipcp.net/transversal/0107/lazzarato/en

- Lazzarato, M. (2014). Signs and machines: Capitalism and the production of subjectivity. Semiotext (e).

- Lazzarato, M. (2015). Governing by debt. Semiotext (e).

- McNiven, A. (2016). Geographies of dying and death’ in relation to pregnancy losses: Ultrasonography experiences. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1033448

- Palmer, J. (2009). Seeing and knowing: Ultrasound images in the contemporary abortion debate. Feminist Theory, 10(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700109104923

- Petchesky, R. (1987). Fetal images: The power of visual culture in the politics of reproduction. Feminist Studies, 13(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177802

- Pink, S., Fors, V., & Glöss, M. (2019). Automated futures and the mobile present: In-car video ethnographies. Ethnography, 20(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138117735621

- Roberts, T. (2012). From ‘new materialism’ to ‘machinic assemblage’: Agency and affect in IKEA. Environment and Planning A, 44(10), 2512–2529. https://doi.org/10.1068/a44692

- Rose, N., & Abi-Rached, J. M. (2013). Neuro: The new brain sciences and the management of the mind. Princeton University Press.

- Ruddick, S. M. (2017). Rethinking the subject, reimagining worlds. Dialogues in Human Geography, 7(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617717847

- Ruyer, R. (2019). The Genesis of Living Forms. Rowman & Littlefield International.

- Sellars, N. (2015). The optics of anatomy and light: A studio-based investigation of the construction of anatomical images. Leonardo, 48(5), 481. https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_01114

- Shepherd, M. (2019). Attuning to the geothermal urban: kinetics, cinematics, and digital elementality. In C. Boyd & C. Edwardes (Eds.), Non-representational theory and the creative arts (pp. 227–242). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stark, H. (2017). Deleuze, subjectivity and nonhuman becomings in the Anthropocene. Dialogues in Human Geography, 7(2), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820617717857

- Stiegler, B. (1998). Technics and time 1: The fault of epimetheus. Stanford University Press.

- Taylor, J. (2008). The public life of the fetal sonogram: technology, consumption and the politics of reproduction. Rutgers University Press.

- Thrift, N. (2004). Remembering the technological unconscious by foregrounding knowledges of position. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 22(1), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1068/d321t

- Williams, N. (2020). Theorizing style (In three sketches). GeoHumanities, 7(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2020.1798801

- Williams, N., & Burdon, G. (2022). Writing subjectivity without subjecthood: The machinic unconscious of Nathalie Sarraute’s tropisms. Social & Cultural Geography, 1–19. Retrieved April 30, 2022, from https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2022.2065694

- Wilson, M. (2015). Paying attention, digital media, and community-based critical GIS. Cultural Geographies, 22(1), 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014539249

- Zhang, V., Kelly, D., Rodriguez Castro, L., Iaquinto, B.L., Hughes, A., Edensor, T., McKay, C., Lobo, M., Kennedy, M., Wolifson, P. and Ratnam, C. (2019). Experiential Attunements in an Illuminated City at Night: A Pedagogical Writing Experiment. GeoHumanities, 5(2), 468–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2019.1624187