ABSTRACT

Graffiti has flourished in the post-apartheid period in Johannesburg, South Africa, in a context where investment in the inner city carries large risks and the city struggles to support arts and culture. In the Maboneng precinct, graffiti and street art have become prolific alongside the recent redevelopment of the neighbourhood. Embracing the global creative city discourse, property developers in Maboneng have co-opted public art, street art and graffiti to brand space and make place, echoing instances of artwashing in other cities around the world. However, Maboneng’s first street art festival was initiated by artists among several other artist-led creative activities. Using mapping and photography, we combine visual and spatial analyses to show the variety and concentration of creative visual inscriptions in Maboneng. Our analysis demonstrates how artists have responded to the opportunities for increased visibility generated through the process of redevelopment. Mapping graffiti and street art reveals a hybrid space that combines both sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions and shows how urban redevelopment can enable a platform and audience for creative endeavours. Our research shows we need a more nuanced understanding of the potential impacts of implementing the creative city discourse in cities such as Johannesburg in the global South.

Resumen

El grafiti floreció en el período posterior al apartheid en Johannesburgo, Sudáfrica, en un contexto en el que la inversión en el centro de la ciudad conlleva grandes riesgos y la ciudad lucha por apoyar las artes y la cultura. En el recinto de Maboneng, el grafiti y el arte callejero se han vuelto prolíficos junto con la reciente remodelación del vecindario. Adoptando el discurso global de la ciudad creativa, los promotores inmobiliarios de Maboneng han elegido el arte público, el arte callejero y el grafiti para marcar el espacio y crear un lugar, haciéndose eco de ejemplos de artwashing en otras ciudades del mundo. Sin embargo, el primer festival de arte callejero de Maboneng fue iniciado por artistas entre otras varias actividades creativas dirigidas por artistas. Usando mapas y fotografías, combinamos análisis visuales y espaciales para mostrar la variedad y concentración de inscripciones visuales creativas en Maboneng. Nuestro análisis demuestra cómo los artistas han respondido a las oportunidades de mayor visibilidad generadas a través del proceso de remodelación. El mapeo del grafiti y el arte callejero revela un espacio híbrido que combina inscripciones visuales autorizadas y no autorizadas y muestra cómo la remodelación urbana puede habilitar una plataforma y una audiencia para los esfuerzos creativos. Nuestra investigación muestra que necesitamos una comprensión más matizada de los impactos potenciales de implementar el discurso de la ciudad creativa en ciudades como Johannesburgo en el Sur Global.

Résumé

Les graffiti ont fleuri pendant la période d’après-apartheid à Johannesbourg, en Afrique du Sud, dans un contexte où l’investissement dans le centre-ville était très risqué et la métropole avait du mal à soutenir les arts et la culture. Dans le quartier de Maboneng, les graffiti et l’art urbain ont commencé à proliférer en parallèle à sa rénovation récente. En adoptant le discours créatif général de la ville, les promoteurs immobiliers de Maboneng ont récupéré les arts publics et urbains et les graffiti pour personnaliser le quartier et le lancer, faisant écho à d’autres exemples d’artwashing dans les villes autour du monde. Néanmoins, ce sont des artistes qui, ainsi que d’autres activités innovantes menées par des créateurs, ont organisé le premier festival d’art urbain à Maboneng. En utilisant la cartographie et la photographie, nous combinons des analyses visuelles et spatiales pour présenter la variété et la concentration d’inscriptions visuelles créatives dans Maboneng. Notre analyse dévoile la réponse des artistes face aux possibilités accrues de visibilité générées par le processus de rénovation. Une cartographie des graffiti et de l’art urbain révèle un espace hybride qui combine les inscriptions visuelles autorisées avec celles qui ne le sont pas et montre comment la rénovation urbaine peut favoriser une scène et une audience pour les projets créatifs. Notre recherche atteste que nous avons besoin d’une compréhension plus nuancée des impacts potentiels de l’implémentation de discours créatifs dans les grandes villes telles que Johannesbourg dans les pays du Sud.

Introduction

In 2013, graffiti artists Freddy Sam and Gaia collaborated on a mural in Johannesburg, South Africa, that depicted a portrait of Jan van Riebeeck, the Dutch coloniser of South Africa. The mural was located in the Maboneng precinct on the eastern edge of Johannesburg’s inner city and was intended as a commentary on the redevelopment of the area, begun in 2009, suggesting that the urban renewal project was a form of neo-colonialism. Although Propertuity, the main developers of the precinct, were not the owners of the wall nor had they commissioned the piece, they received several complaints questioning the prominence given to the Dutch coloniser, implying that the public did not easily interpret the intended meaning of the mural.

The mural reflects broader criticism of the redevelopment of the area as a form of gentrification and exclusion (Ah Goo, Citation2018; Nevin, Citation2014; Walsh, Citation2013) and is also indicative of concerns with the application of the creative city discourse in Johannesburg (Pieterse & Gurney, Citation2012). Despite the mural’s meaning, complaints to the developers, and significant investment in the public environment in Maboneng, graffiti and street art have not been censored or erased as buildings have been redeveloped. Rather, Propertuity used photographs of the mural (among many images of graffiti and street art) to promote the precinct, including on their website and in official documents. This is consistent with how graffiti and street art murals have been co-opted in redevelopment projects – a process termed ‘artwashing’ and foregrounded by several scholars (Francis, Citation2017; O’Sullivan, Citation2014; Schacter, Citation2014). At the same time, the mural was intended to be critical, reflecting the transgressive tradition of graffiti and street art (Mackay, Citation2015).

The mural illustrates the complexity in exploring the application of the creative city discourse and artwashing in Maboneng. We explore these tensions in this paper, beginning with a consideration of the relationship between graffiti, street art and the urban environment, including processes of urban renewal and the creative city discourse. We then provide some contextual background to our research methods and the case study area of Maboneng. Our empirical findings focus on detailed mapping of the many visual inscriptions in Maboneng, documented through geocoded photographs in 2017 and 2018. We show that alongside the redevelopment of Maboneng there has been a substantial increase in visual inscriptions in the area, predominantly of graffiti but including street art and public art. In addition, property developers, tenants and residents have fostered other artistic activities such as theatre, art studios, and independent cinema. Our analysis shows how graffiti, street art, public art and murals coexist in the precinct and serve to make place and brand space, while also revealing that the redevelopment has created an audience for graffiti, allowing artists to be both creative and visible. Sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions are scattered throughout the precinct, resulting in surfaces and structures in Maboneng being multilayered, incorporating both old and new inscriptions, unsanctioned graffiti and street art as well as commissioned murals explicitly branding space. Far more than simple artwashing, the redevelopment has supported and enabled original creative expression in the precinct in the context of a small arts industry in Johannesburg.

Defining graffiti, street art and public art

Defining modernFootnote1 graffiti is difficult as it is fluid and its practice and definitions have evolved since its origins in the late 1960s (Avramidis & Tsilimpounidi, Citation2017). Street art is a practice that emerged from graffiti some 30 years later in the late 1990s and has been defined as a specific art period rather than a practice (Schacter, Citation2014, Citation2017). The key distinction that most scholars agree on is that graffiti explores textual forms and uses media such as markers and aerosol paints while street art is image-based and has a much wider use of media and materials, including aerosol paints as well as posters, found objects and sculpture (Avramidis & Tsilimpounidi, Citation2017; Chung, Citation2009; Grider, Citation1997; Schacter, Citation2014; Whitehead, Citation2004; Young, Citation2017). This is largely where consensus ends.

A significant aspect of defining street art and graffiti is in relation to the law. Street art, with its accessible images, is seen to be more acceptable than and distinguished from graffiti which has for a long time been considered vandalism (Schacter, Citation2014; Whitehead, Citation2004; Young, Citation2017). Although Schacter (Citation2014) notes that no street artist (as defined by the author) has yet been arrested for their practice, both street art and graffiti comprise activities that span a spectrum from legal to illegal (Avramidis & Tsilimpounidi, Citation2017). For criminologists who have studied graffiti, its definition is dependent on the practice being illegal (Weisel, Citation2002; White, Citation2001). However, other scholars have long recognised that some graffiti is authorised, commissioned or painted with permission (Anderson & Verplanck, Citation1983; Craw et al., Citation2006; Kramer, Citation2010).

There is also value in not striving to distinguish between graffiti and street art. ‘Graffiti and street art unfold as a series of dialectical tensions’ (Ferrell, Citation2017, p. 27) and, by considering them together, key ‘theoretical, methodological and empirical connections’ can be drawn (Avramidis & Tsilimpounidi, Citation2017: 11). Sabrina Andron’s (2017, p. 71) research examines graffiti and street art in a larger visual context to bring these practices and others together under the term ‘hybrid surface inscriptions’.

In some instances, street art that is formally commissioned forms a part of public art. Public art includes various forms of creative expression in public spaces, such as sculptures, murals and statues (Sitas, Citation2015), and is usually commissioned and publicly or privately funded. In Johannesburg, formal definitions of public art in policy include graffiti among a variety of media (JDA, Citation2010). There are thus considerable overlaps between the practices of graffiti, street art, and public art.

This paper investigates the visual landscape of Maboneng, including graffiti, street art, public art, painted signage and commercial advertising. These expressive forms are present in the Maboneng precinct and artists are increasingly incorporating several of them in their practices (Ferrell, Citation2017). Wherever possible, we identify the nature of a visual inscription but recognise the difficulty in distinguishing definitively between graffiti, street art, murals and public art. We use the term ‘creative visual inscription’ to encompass graffiti, street art and public art, differentiating them from other forms which are less creative and more functional, such as signage and advertising.

Graffiti in the urban context

Graffiti is both a highly global phenomenon as well as a hyperlocal practice. Contemporary graffiti originated in the US in the 1960s and spread quickly to other parts of the world through various media. South Africa was no exception, although graffiti during the apartheid regime was largely political and concentrated on resistance and fighting for freedom (Waddacor, Citation2014). Since the advent of democracy in 1994, graffiti artists and the South African graffiti subculture have been less engaged with politics (Sitas, Citation2015). Graffiti has flourished in the South African post-apartheid period, evolving into a more expressive art form, although falling short of developing a distinctive South African style as it still leans heavily on western art styles (Waddacor, Citation2014). From 1984, substantial graffiti and hip hop subcultures emerged in Cape Town (Waddacor, Citation2014). However, Johannesburg currently boasts the biggest graffiti scene in South Africa, with up-and-coming writers making constant contributions (Waddacor, Citation2014). Graffiti artists in Johannesburg are focused on placing themselves within the global street art movement and actively refrain from pieces that invite oppositional politics, resulting in a relative lack of political graffiti in the city (Smith, Citation2017).

Over time, residents of Johannesburg have accepted some forms of graffiti as an addition to the urban landscape, largely embracing the aesthetics of the graffiti subculture. This is similar to the conditions in ‘saturated cities’ such as Sao Paulo or Bogota, where graffiti is so ubiquitous that residents and authorities tolerate it (Morrison, Citation2015; Van Meerbeke & Sletto, Citation2019). Graffiti and street art are prolific in Johannesburg and are highly varied in their subject matter and political stance.

Graffiti may be the most familiar form of visual culture in our everyday lives (Kan, in Whitehead, Citation2004, p. 26). Graffiti artists seek visibility on international stages as part of global practices but also engage with the urban environment at micro scales and in multifaceted ways (Ferrell & Weide, Citation2010; Scheepers, Citation2004). The graffiti subculture is fuelled by contact with police, media attention and public recognition, all of which enhance an artist’s reputation (Ferrell & Weide, Citation2010). Graffiti often follows high traffic areas to be more visible (Ferrell & Weide, Citation2010). Artists constantly shift between clandestine spraying to evade authorities and seeking visibility and fame through their writing. Graffiti artists carefully appraise locations and consider ‘patterns of light, human movement, neighbourhood policing tendencies, lines of visibility, major routes of commuter travel, and phases of urban development and decay’ when choosing a ‘spot’ for their graffiti (Ferrell & Weide, Citation2010, p. 49). The scale, placement and visibility of graffiti at the local scale is critical to understanding how artists leverage the urban environment as part of their practice.

Graffiti and the creative city

Graffiti and street art are intertwined with both organic (artist-led) and inorganic (developer-led) creative city transformations. The creative city discourse was sparked by the scholarship of Richard Florida in the early 2000s. He argued that cities could attract investment, economic growth and urban renewal by courting the creative class (Florida, Citation2002). In theory, this could be achieved relatively cheaply by building bike lanes or supporting music scenes and was rapidly adopted by urban authorities and incorporated into policies around the world. However, while many urban policy-makers have embraced the creative city discourse, scholars have criticised the approach for showing little evidence of success (Peck, Citation2005). In Johannesburg, the application of the creative city discourse has been criticised for ignoring structural inequalities in favour of notions of diversity (Pieterse & Gurney, Citation2012). In a context of high inequality, the City of Johannesburg frequently struggles to balance serving the needs of the poor and attracting investment.

There is a close relationship ‘between graffiti and the ways in which subcultural creative clusters emerge and migrate around the city’ (Dovey et al., Citation2012, p. 36). Graffiti and street art are signifiers of change and difference, leading to ‘distinction’ and identifying districts inhabited by creatives (Zukin & Braslow, Citation2011). Spontaneous street murals in lower-income areas created by graffiti artists are viewed as a form of positive participatory urban refurbishing that indicates a shift towards greater artistic residency and activity. But this same shift can be the beginning of gentrification, as creative activities are frequently followed by higher-income residents and property developers, often excluding lower-income inhabitants, including the artists themselves (Zukin & Braslow, Citation2011). This may be a fairly guaranteed process in the cities of the Global North but in the shifting property market of Johannesburg these processes are far less predictable.

This organic process has been adopted and accelerated in urban redevelopment projects. Property developers have deployed artists and public art, motivated by the organic process as well as the creative city discourse, to enhance property values and realise greater economic returns (Dovey et al., Citation2012; Gregory, Citation2016; Sharp et al., Citation2005; Zukin & Braslow, Citation2011). Graffiti and street art become key urban planning tools in the placemaking of urban renewal projects, ‘with two fundamental requirements; to anchor place and accrue profit’ (Schacter, Citation2014, p. 164). The use of public and street arts in urban regeneration has been critiqued as a capitalist logic which seeks to commodify urban spaces and increase property values, while also being exclusionary, only benefiting urban developers and the economically privileged of society (Bridge, Citation2001; Kuyucu & Unsal, Citation2010). While graffiti and street art have been used in much the same way in Maboneng, we challenge the idea that this does not offer some benefits to the artistic community.

Property developers’ deliberate use of artists and commissioned artworks in urban areas has led to the derogatory term ‘artwash’ and has seen artists in these contexts heavily criticised (Francis, Citation2017; Schacter, Citation2014). Graffiti and street artists are seen to be complicit in these urban politics, losing all radicality and reduced to selling place and branding space (Pritchard, Citation2017; Schacter, Citation2014). However, artwashing is a brush with broad strokes that can overlook how graffiti artists navigate these urban politics: sometimes being pushed out of a redeveloped area (Halsey & Pederick, Citation2010) and in other situations securing opportunities through the expanding urban canvas (Romero, Citation2018) and increasing ‘opportunities for collective criticism, transgression, and subversion’ (Zukin & Braslow, Citation2011, p. 132). Graffiti artists are increasingly operating between the world of sanctioned murals and street art and the free-form, often illicit world of graffiti, because there are both economic and aesthetic gains from exploiting these opportunities (Ferrell, Citation2017; Kramer, Citation2010). Whilst this diversity of graffiti writing does not eliminate the politics of the control of surfaces and spaces, it does have the potential to offer a new urban ecology: ‘an ecology that makes room for graffiti as neither publicly sanctioned art nor crime’ (Halsey & Pederick, Citation2010, p. 97), particularly in contexts such as Johannesburg.

In Johannesburg, graffiti occupies a legal grey area: several by-laws prohibit graffiti in relation to municipal property or structures related to public roads. However, the Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA) has a city-wide public art programme that includes graffiti (JDA, Citation2010). At the same time, Section 16 of the City of Johannesburg’s 2007 Public Art Policy enacts an Anti-Graffiti Rapid Response Unit, which has been known to issue harsh punishments for the defacement of public property (City of Johannesburg, Citation2007). The City’s conflicting and ambiguous policies towards graffiti and its management is apparent in the visual landscape of Johannesburg: full of graffiti and street art.

Method

Our research focused on documenting the visual inscriptions in Maboneng, observing any changes during fieldwork, and the public’s engagement with graffiti, street art and public art in the precinct. The primary data collection method was participant observation through tours and photography. Most data were collected through photographic observation during two visits to Maboneng spanning a period of six months, in August 2017 and January 2018. Both visits were guided by a local tour guide with a focus on graffiti and street art. We also interviewed the local tour guide as an expert on graffiti in Johannesburg, as well as the marketing and brand manager of Propertuity, the main developer at the time in Maboneng. Secondary data collection was conducted using Google Earth satellite imagery and archival images from Google Maps Street View. We also obtained eight maps from various online sources to contextualise the locations of redeveloped buildings in the precinct.

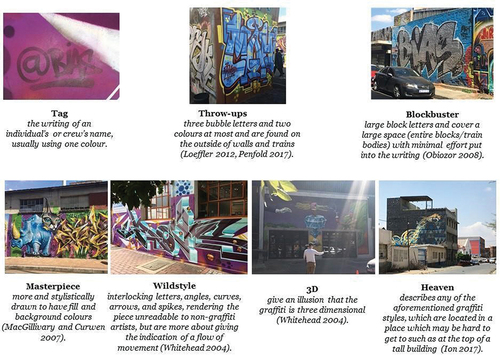

During the site visits, geo-enabled photos of visual inscriptions were taken and the locations were digitised from maps using Google Earth satellite imagery. Photographs were taken of approximately 133 sites of visual inscriptions in Maboneng – 166 in August 2017 and another 195 in January 2018. All visual inscriptions identified in the photographs, including public art, hand-painted signage and commercial advertising, were categorised by type, with the help of similar studies for reference to distinguish between different types of graffiti, e.g., tags, masterpieces, blockbusters and throw-ups, etc. (see ; Grider, Citation1997; Gross & Gross, Citation1993; Ion, Citation2017; Loeffler, Citation2012; MacGillivray & Curwen, Citation2007; Penfold, Citation2017; Whitehead, Citation2004). The photographs were recorded in Microsoft Excel and used to categorise and quantify each visual inscription at each location in Maboneng. Mapping software (ESRI ArcMap 10.3 and 106 and Quantum GIS (QGIS) 2.8) was used to open and create spatial layers from the geocoded photos and maps showing redeveloped buildings and map the spatial layers.

Figure 1. A visual glossary of graffiti types using examples from Maboneng, Johannesburg. Photos and compilation by author.

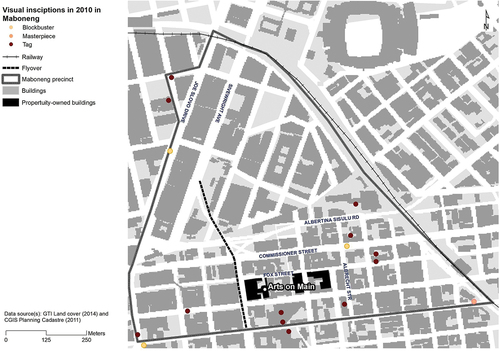

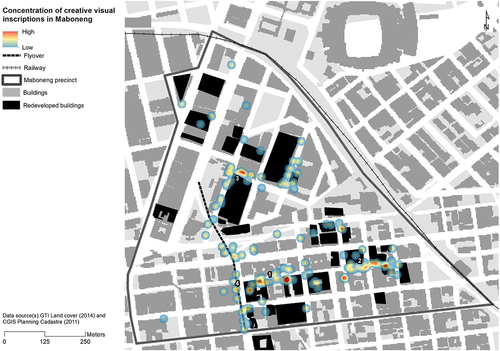

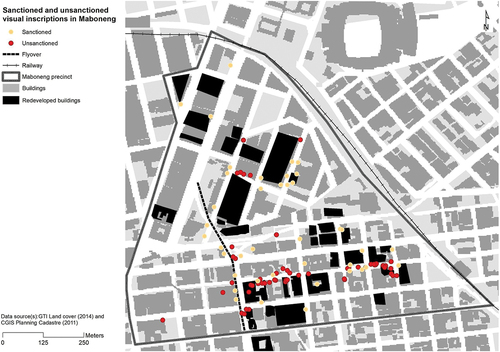

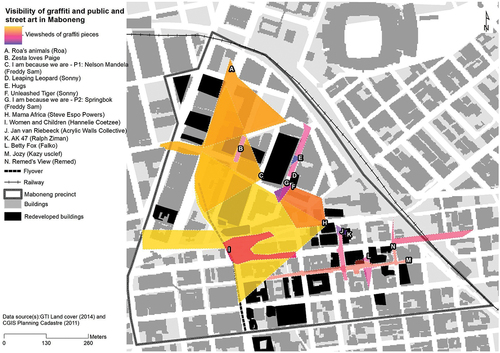

These resultant spatial layers were used to map and analyse the visual inscriptions and their relationship with urban renewal processes in Maboneng. Five key maps were produced: a map of the different types of visual inscriptions (); a heat map showing the concentration of creative visual inscriptions (); a map showing visual inscriptions present in 2010 (); a map of sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions (); and a map showing the visual reach of large-scale murals [also termed ‘heaven’ pieces] (Figure 10).

The first map shows the different types of graffiti and public and street arts prevalent in Maboneng. Several types of graffiti were present in some sites, while some sites were characterised by both graffiti and public and street art. The graffiti and public and street art types’ spatial layer was thus separated based on the visual inscription type to enable layering and the modification of the layer symbology. The second map used the locations of visual inscriptions to generate a heat map (a map showing concentration), using a radius of 15 metres in QGIS desktop.

The third map shows sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions. To distinguish between the two categories, we employed a number of assumptions about graffiti, public and street art in Maboneng, in line with broader assumptions about authority and control in the urban environment (Young, Citation2017). We also had some data from our guided tour and interview with the graffiti expert to guide some of the categorising. In this study, we assumed that the more informal and less elaborate forms of graffiti, such as tagging and throw-ups, and street art forms, such as stickers and stencils were unsanctioned as these were likely done quickly and without permission. Large murals on building facades were assumed to be sanctioned given the investment of time and resources needed to produce these works. Between these two extremes is a grey area where visual inscriptions could be sanctioned or unsanctioned, a level of categorisation is increasingly difficult (Andron, Citation2017) and we used the location (private wall or public surface), redevelopment status as well as materials and details of the work to estimate whether permission was obtained. This pertains to 15 of the visual inscriptions, so we are confident that the majority of the data have been correctly categorised.

The fourth map, a visibility analysis of visual inscriptions, used analysis conducted on Google Earth (taken 25 March 2018) and Google Maps Street View (2017 data), using the default Landsat satellite imagery. The three-dimensional buildings feature was enabled to establish the visual reach of the inscriptions, considering various aspects of the urban fabric and topography. The visual reach of each inscription was analysed from different angles and at the street level using Google Maps Street View. Polygons, closed geometrical shapes were created covering the extent of the visibility or viewshed of the visual inscriptions.

The fifth map sought to understand how visual inscriptions have changed since the redevelopment began in Maboneng. To do this, a systematic review of the Maboneng precinct was conducted using Google Street View in March 2021. The most recent image data for Maboneng is from 2017 but using the archive function on the Google Maps Street View application, where images from between February and September 2010 were accessed. Unfortunately, no earlier data are available. For our analysis, we only used data and images from 2010, as this is shortly after redevelopment began in the precinct. We reviewed every street included in the Maboneng precinct. For the majority of streets, data were available from 2010, but only from 2013 in a few locations. Screenshots of visual inscriptions were taken with the location and address recorded. These images were then coded by type and mapped using the address data to produce a map of visual inscriptions in Maboneng in 2010. There are limitations to this method: the graffiti needed to be large enough to be visible in the photographs, so small tags and stickers that can only be viewed in close proximity were not captured; and only graffiti visible from the street was captured in the images – graffiti around corners and between buildings were not recorded.

Maboneng as a site of urban renewal

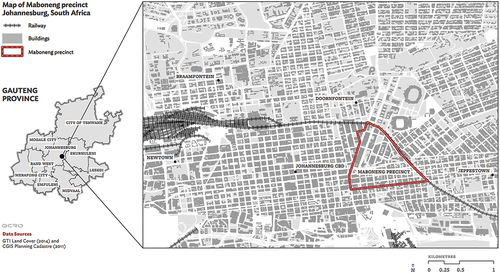

Maboneng is a rebranded area of urban renewal of Johannesburg known as City and Suburban, named after the City and Suburban Mine of Johannesburg’s earliest years (). The precinct, measuring approximately500000m2, began in 2009 with the development of Arts on Main: a gallery and art studio space. The objective was to create a mixed-use higher-density neighbourhood from the existing, light industrial buildings (dating from the 1940s and 1950s) and commercial offices. From 2011 onwards, Propertuity acquired and developed Main Street Life, which included a hotel, a cinema and a theatre and placed a significant focus on the arts and creative businesses in the precinct (Gregory, Citation2016). By 2016, although not the exclusive developers of Maboneng, Propertuity owned 47 buildings in the area providing residential, commercial and retail space (Propertuity, Citation2016), mostly to the north of Arts on Main (Parker et al., Citation2019) but by 2019, the company had been liquidated and the majority of its assets sold on auction.

Although Maboneng is a private-led development, it is strongly aligned with the City’s urban renewal policies and creative city discourse, which emerged from severe decay and decline in the inner city. Beginning in the 1970s, the inner city witnessed a decrease in business and manufacturing (Beavon, Citation2004; Goga, Citation2003) coupled with white flight to the north. This change in racial composition led eventually to the accommodation of poorer Black residents (Morris, Citation1994). The 1990s saw an enormous influx of people, the densification of existing residential accommodation, and the informal conversion of vacant office buildings for residential use. These changes in the inner city were associated with deterioration, congestion, overcrowding and crime.

From the early 2000s, the new metropolitan administration, the City of Johannesburg, responded to the poor inner-city conditions by drafting policies to redevelop and regenerate the central business district. These drew heavily on the creative city discourse (Dinath, Citation2014; Pieterse & Gurney, Citation2012) and led to the establishment of the JDA, to implement renewal projects in precincts such as the Newtown Cultural Precinct and the Fashion District (Harrison & Phasha, Citation2014). The urban regeneration policies were intended to promote local economic development by encouraging local investment by the private sector through the provision of a national tax incentive for urban development zones (UDZs; Gregory, Citation2016). As a way of managing these UDZs and accompanying changing urban economies, as well as the physical and social environment driven by private investment, the City initiated city improvement districts (CIDs), which are collectives of property owners, to provide additional services such as cleaning, beautification and security (Didier et al., Citation2013).

Scholars and practitioners have critiqued the City’s adoption of creative city policies, primarily because they fail to address the stark inequalities, both current and historical, plaguing Johannesburg (Dinath, Citation2014; Pieterse & Gurney, Citation2012). Similarly, Matsipa argues that the use of public art in urban redevelopment fosters neoliberal capitalist accumulation and the formation of a mechanism for limiting ‘informal economic activities in the city’s public and commercial spaces’ (2014, p. 6). Maboneng has not escaped this criticism. Policy-makers and the public alike have criticised this private-led urban regeneration as a form of gentrification (Nevin, Citation2014; Walsh, Citation2013), despite its self-promotion as an inclusive and conscientious development. Although its development has displaced some residents and users of Maboneng, Nevin (Citation2014) argues that the social exclusion in Maboneng also stems from its distinct aesthetic and architecture. Maboneng is also highly securitised and is managed by a ‘super CID’ formed with the New Doornfontein CID. Although not secured by walls or a fence, it has a heavy security presence (Ah Goo, Citation2018) – mainly security guards visibly patrolling the streets, which limits accessibility and participation and promotes further class divisions (Nevin, Citation2014; Vejby, Citation2015). However, we illustrate in this paper that Maboneng is far from a straightforward case of gentrification, particularly following the liquidation of the main property developers, and the distinct aesthetic has fostered original artistic expression in the neighbourhood.

Maboneng as a creative site in Johannesburg

Johannesburg supports many creative industries, with artists and creative professionals tending to be scattered all over the city rather than concentrated in a particular neighbourhood. For example, there is a thriving television and film industry, bolstered by the presence of the South African Broadcasting Corporation headquarters in Auckland Park, but research shows that film and television businesses are dispersed across the city with very little agglomeration (Visser, Citation2014). Similarly, theatres and art galleries are dotted around the inner city and the northern suburbs. August House is a collective of artists living and working together but it is limited to a single inner-city building (Gurney, Citation2017). Even with one other building supporting artists in residence (The Bag Factory in Newtown), the conditions are precarious for artists, demonstrated when they were once again dispersed in anticipation of ownership change of August House (Gurney, Citation2017).

There is substantial evidence that the redevelopment in Maboneng successfully sparked a number of artistic activities that enriched the city. Maboneng hosted the PopArt theatre (2011–2020), The Bioscope, an independent cinema (one of only a handful in Johannesburg), the Museum of African Design (even if the museum functioned more as a gallery and event space), and the annual student exhibitions of the Graduate School of Architecture from the University of Johannesburg, among others. Perhaps the best evidence is detailed through world-renowned artist William Kentridge’s relationship to Maboneng. He was the most prominent artist to occupy a studio in the first development of the area, Arts on Main. Since then, he has established an arts programme called The Centre for the Less Good Idea in Maboneng, which funds and stages experimental arts projects. Kentridge invested further in the area by purchasing other studios and buildings, particularly around the time of the liquidation auction (Anderson, Citation2019; Ho, Citation2019). These activities reveal some of the ways in which artists gathered and created in Maboneng following the investment of the property developers.

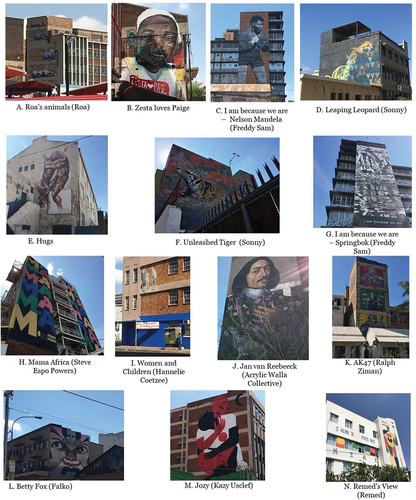

This artistic engagement is reflected in the graffiti and public and street art of Maboneng. Maboneng’s first street art festival, I Art Joburg, in 2012, was initiated and organised by the artist Ricky Lee Gordon and sponsored by Adidas and Plascon. Gordon was motivated to access the large, high walls and facades prevalent in the neighbourhood and not easily available in other locations (Taitz, Citation2012). Although Propertuity did not instigate the festival, they were supportive of it and provided three walls for artists (Ciolfi, Citation2013). The festival was clearly aligned with Propertuity’s creative city focus and Jonathan Liebmann, head of Propertuity, is quoted at the time as saying ‘ … mural art can play a significant role in urban renewal as it has the ability to change the way people perceive and engage with their environment and can often be the catalyst for the upliftment of the built environment’ (Ciolfi, Citation2013, webpage). Eight murals, which went on to become iconic emblems for the Maboneng precinct, were installed as part of the festival. They were photographed by world-renowned graffiti enthusiast Martha Cooper, not only creating high visibility for Maboneng within the city but also putting the precinct on the global map. Other murals followed. In 2013, the mural of Jan van Riebeeck was added by Gaia and Freddy Sam and followed in 2014 by two 40 metre murals commissioned by Propertuity on the sides of a redeveloped building. Our detailed mapping below elaborates on how the redevelopment of Maboneng fostered this creative expression of graffiti and street artists in the precinct.

Mapping visual inscriptions in Maboneng

A systematic review of all streets in Maboneng, using the archived images from 2010, revealed 25 sites of graffiti, of which the majority contained single or multiple graffiti tags. These sites are mapped in . The map shows that most of the tagging occurs along busier streets with higher vehicular and pedestrian traffic levels, a common tactic amongst graffiti artists to increase visibility (Ferrell & Weide, Citation2010). However, it also shows significant absences – areas all along the railway line are free of any graffiti despite the fact that graffiti artists in other contexts frequently target these kinds of areas. This is probably because the train services in Johannesburg are severely underutilised.

Graffiti can be found on a variety of urban surfaces and objects, including walls, trains, infrastructure, signage, advertising and road surfaces; this is no different in Maboneng. Visual and spatial data, captured through photographs, captures a diverse range of visual inscriptions, from simple graffiti tags to more elaborate and artistic works, including public and street art, hand-painted signage and commercial advertising. Approximately half of the photographs contained more than one type of visual inscription by different artists and the most commonly recorded visual inscription was graffiti tagging. Most sites contain multiple instances of graffiti and are characterised by more than one graffiti style and instance – all indicative of a neighbourhood saturated in graffiti and street art and illustrated in .

The map shows a scale of concentration ranging from high (red) to low (blue) with four areas in Maboneng of very high concentrations. Sites 1 and 2 are located on Fox Street and are closely tied to the redevelopment activities along this street; site 3 is a wall that explicitly invites graffiti artists to ‘#MakeYourMark’ and, as such, has generated an intensity of graffiti inscriptions; and site 4, along the underside of the flyover (shown as a dotted line), includes a wide range of creative visual inscriptions as well as Maboneng place branding. The highest concentrations are in places along the streets that were redeveloped first. The map thus highlights the relationship between the redevelopment of Maboneng and creative visual inscriptions, revealing how the redevelopment has fostered significant artistic expression in the area. This can also be seen in the different intensities of creative visual inscriptions shown in , showing a dramatic increase in less than eight years.

Maboneng’s creative visual inscriptions have occurred in conjunction with various place branding elements implemented by Propertuity, including several public art installations, pavement upgrades and new street trees. Although large murals can be used to deter graffiti (Craw et al., Citation2006), this is not the case in Maboneng as most of the murals are at heights that are not easily accessible or are located on walls that were not previously heavily inscribed. In addition, graffiti is not actively erased by either Propertuity or the New Doornfontein CID, the collective authorities who manage the precinct.Footnote2 In fact, there is a high degree of tolerance for graffiti in the precinct – evident in the wall inviting artists to ‘#MakeYourMark’ and the many graffiti inscriptions that are larger, more detailed and therefore more time consuming to produce.

This co-occurrence of graffiti and public and street art is illustrated in a map of sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions in Maboneng (). The map shows that unsanctioned visual inscriptions are scattered throughout the precinct and are prevalent in the parts of Maboneng that were developed first, along Fox Street. While sanctioned visual inscriptions include those that were not commissioned by the property developers, the occurrence of both sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions in the redeveloped parts of the precinct indicates that street art, public art and murals have not been used to sanitise or limit other forms of visual inscription. The map also reinforces that multiple forms of creative visual inscription have been fostered in the precinct, reflecting the hybrid practices of many of the artists.

The explosion of creative visual inscriptions in the Maboneng precinct since 2010 can be attributed to the way in which the urban redevelopment has increased visibility for artists by congregating an audience. As artists seek visibility and recognition for their work, they choose locations or sites where people will see their inscriptions. With the redevelopment of Maboneng, these high-visibility locations are no longer along the busy main roads but instead are in close proximity to the redeveloped buildings (). The Maboneng redevelopment has created greater visibility in two key ways: through the concentration of artistic activities, cultivating a creative audience; and through maximising large-scale structures and surfaces for visual impact.

The graffiti tours best exemplify the greater visibility and increased audience for graffiti in Maboneng in the precinct. A local tour company conducts a variety of tours in Johannesburg, including specific tours focused on graffiti. These tours attract both local visitors and international tourists and are frequently guided by local graffiti artists – reminiscent of walkabouts with artists in galleries. This ‘tourist gaze’ is responding to the heightened occurrence and visibility of graffiti in Maboneng (Urry, Citation2002), in turn further increasing the visibility of graffiti through promotional platforms such as brochures, the internet and social media. Graffiti tours legitimise a street art scene through authoritative discourse (Andron, Citation2018) and are key to how the creative city creates additional value through urban redevelopment.

The second key way Maboneng has created greater visibility for artists is through the use of large-scale structures and surfaces for graffiti, street art and murals. Initiated by graffiti artists and enthusiastically adopted by the property developers, large murals have become an iconic visual element of Maboneng. Some are explicit branding images, using the SeSotho word ‘Maboneng’ or its English translation ‘Place of light’ to make place in the precinct, but many are creative expressions and artworks.

To further explore the scale and visibility of these murals, we selected large, prominent graffiti and public and street art pieces on high-rise buildings in Maboneng () and mapped the visual reach or viewsheds of each (). Viewsheds with greater reach cover a larger area while the viewsheds with less visual reach are represented by smaller polygons. Works such as ‘Nelson Mandela’ by Freddy Sam, ‘Mama Africa’ by ESPO () and ‘Jozy’ by Kazy Usclef can be seen down streets for several blocks and in some cases beyond the boundaries of Maboneng itself. Both ‘Mama Africa’ and ‘Nelson Mandela’ are well placed for visibility along the raised flyover coming down from the M2 highway. These works conform much more to the conventions of street art, maximising visibility and accessibility by taking advantage of the building facades (Schacter, Citation2017).

Figure 6. Images of the most prominent graffiti and street art murals in Maboneng. The letters next to the name of each mural, correspond with the letters and labels on the map. Photos and compilation by author.

Graffiti and street art with greater visual reach is concentrated in the northern part of the precinct, located on buildings bought and developed after 2013. This is because the taller buildings in the north are less crowded and are more easily viewed from the flyover roads. The placement of graffiti and street art on these taller buildings increases the visibility of these inscriptions beyond the precinct boundaries and beyond the audience cultivated around the activities and buildings in the southern part, along Fox Street. In addition, the large-scale and colourful murals painted by artists inspired existing property owners in the precinct. A long-standing bar, the Zebra Inn, painted the facade of its building in striking zebra stripes in 2013, contributing to the changing visual landscape of Maboneng (visible in ).

Figure 8. ‘Mama Africa’ by ESPO is a large-scale, highly visible mural in the Maboneng precinct. Photo by author, August 2017.

The maps and analysis indicate that the number, variety and type of creative visual inscriptions, including street art, have increased significantly since 2010, coinciding with the period of urban redevelopment. As noted, this has largely been driven by artists and later adopted by the main property developers, Propertuity. These inscriptions are primarily located around redeveloped buildings, rather than around existing busy vehicular routes, reflecting the change in audience and its location in the precinct.

Visibility is a key element of graffiti, street art and visual inscriptions in general. However, visibility is not limited to the surfaces and structures that provide visibility or who has control over these surfaces (Andron, Citation2017; Schacter, Citation2017), but also includes the people who will view the inscriptions. Maboneng’s developers, by clustering and fostering a variety of artistic activities and enterprises, created an audience for creative visual inscriptions. In some cases, the property developers leveraged these inscriptions to brand space and promote the precinct, but in many cases, artists were attracted to creating in Maboneng and leveraged their own resources to access the surfaces and newly available audience. These spaces were not tightly controlled by the property developers and include both sanctioned and unsanctioned visual inscriptions and a variety of media.

Conclusion

Rather than focusing on the nuanced differences between graffiti, street art, public art and murals, we have instead shown how all of these creative visual inscriptions are erupting in the redevelopment of Maboneng. From its inception, the developers of Maboneng courted creative professionals, carefully selecting tenants and activities, and supported this through investment in public art. Thus, Maboneng is an exemplar of the implementation of the creative city agenda in Johannesburg. However, Maboneng has not had to compete with any existing organic creative hubs in the city, and is in fact a departure from Johannesburg’s status quo, where investment in the inner city carries large risks and the city struggles to support arts and culture. It is in this context that the redevelopment of Maboneng has enabled and supported original artistic expression, evident in the now rich visual landscape.

This research provides a mixed picture of the role of graffiti and street art in urban renewal steeped in the creative city discourse. Property developers have explicitly used public art, street art and graffiti to brand and promote the Maboneng precinct and to make place – what many would define as ‘artwashing’. However, at the same time, the redevelopment has fostered original artistic creativity. The redevelopment of Maboneng has created an audience and increased visibility for graffiti and street artists who have responded to these changes by producing larger and more elaborate pieces. Artists are capitalising on the creation of an audience in the precinct and leveraging access to large surfaces with greater visibility, showing how multiple stakeholders are laying claim to the surfaces in Maboneng, echoing artists in other locations (Ferrell, Citation2017; Kramer, Citation2010). We have shown that terms such as ‘artwashing’ are not always easily applied and that urban redevelopment with a creative city lens may offer some benefits to local artists and visual culture in general. The variety of creative visual inscriptions and hybrid practices in Maboneng offers some insight into what Halsey and Pederick (Citation2010) term the ‘new urban ecology’.

The context of Maboneng is key to reconsidering the roles of the creative city discourse and ‘artwashing’. The reframing of these concepts may only be applicable in contexts where artistic activities are not strongly supported and where redevelopment retains some elements of inclusion – thus allowing artists to independently participate in the redevelopment process. Studies in similar contexts in other parts of the world would contribute significantly to the development of these ideas.

These findings are tentative, however. The redevelopment of Maboneng is a little over a decade in progress and the area is still very much in transition. The prevalence of graffiti and street art in Maboneng may just be a reflection of this social upheaval (Ferrell, Citation2017). The commodification of placemaking and street art in Maboneng proved to be limited for Propertuity, which went into liquidation in 2019, indicating that profit does not always follow extensive place branding (Schacter, Citation2014). Some artistic activities have endured but some have closed or moved to the northern suburbs. Recently completed redeveloped buildings are targeting more affordable housing markets – much more in keeping with surrounding neighbourhoods and the demographics of the city as a whole. This may change the audience in Maboneng and only time will tell how this will impact the visual inscriptions and the associated cultural practices.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to our colleagues, in particular, Richard Ballard and Julia de Kadt, who provided invaluable input in shaping this research. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on a previous draft and appreciate the support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Graffiti, the practice of writing or drawing on walls, is almost as old as human civilisation. Diverse examples include San rock paintings in sub-Saharan Africa and the etchings on buildings in Pompeii, Italy.

2. Shruthi Nair, interview by authors, March 2018, Propertuity Offices, Maboneng.

References

- Ah Goo, D. (2018). Gentrification in South Africa: The ‘forgotten voices’ of the displaced. In J. Clark & N. Wise (Eds.), Urban Renewal, Community and Participation: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 89–110). Springer.

- Anderson, A. (2019). William Kentridge to Maboneng’s rescue? Financial Mail, 2 May. https://www.businesslive.co.za/fm/fm-fox/2019-05-02-william-kentridge-to-mabonengs-rescue/

- Anderson, S. J., & Verplanck, W. S. (1983). When walls speak, what do they say? The Psychological Record, 33(3), 341 https://search.proquest.com/openview/4c3e35a884a3bb98c9b1b75fe3513278/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&1817765.

- Andron, S. (2017). Interviewing walls: Towards a method of reading hybrid surface inscriptions. In K. Avramidis & M. Tsilimpounidi (Eds.), Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (pp. 71–88). Routledge.

- Andron, S. (2018). Selling streetness as experience: The role of street art tours in branding the creative city. The Sociological Review, 66(5), 1036–1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118771293

- Avramidis, K., & Tsilimpounidi, M. (Eds). (2017). Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City. Routledge.

- Beavon, K. (2004). Johannesburg: The Making and Shaping of the City. Unisa Press.

- Bridge, G. (2001). Bourdieu, rational action and the time–space strategy of gentrification. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 26(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5661.00015

- Chung, S. K. (2009). An art of resistance from the street to the classroom. Art Education, 62(4), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043125.2009.11519026

- Ciolfi, T. (2013). Adidas Area 3/I Art Joburg. Texx and the City, 24 January. https://texxandthecity.com/2013/01/adidas-area-3i-art-joburg/

- City of Johannesburg. (2007). Public Art Policy. The City of Johannesburg: Arts, Culture and Heritage Services.

- Craw, P. J., Leland, L. S., Bussell, M. G., Munday, S. J., & Walsh, K. (2006). The mural as graffiti deterrence. Environment and Behavior, 38(3), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505281580

- Didier, S., Morange, M., & Peyroux, E. (2013). The adaptative nature of neoliberalism at the local scale: Fifteen years of city improvement districts in Cape Town and Johannesburg. Antipode, 45(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.00987.x

- Dinath, Y. (2014). Between fixity and flux: Grappling with transience and permanence in the inner city. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing Space, Changing City: Johannesburg after apartheid (pp. 231–250). Wits University Press.

- Dovey, K., Wollan, S., & Woodcock, I. (2012). Placing graffiti: Creating and contesting character in inner-city Melbourne. Journal of Urban Design, 17(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2011.646248

- Ferrell, J. (2017). Graffiti, street art and the dialectics of the city. In K. Avramidis & M. Tsilimpounidi (Eds.), Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (pp. 27–38). Routledge.

- Ferrell, J., & Weide, R. D. (2010). Spot theory. City, 14(1–2), 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810903525157

- Florida, R. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class: And How it’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life. Basic Books.

- Francis, A. (2017). “Artwashing” gentrification is a problem – But vilifying the artists involved is not the answer. The Conversation, 5 October. https://theconversation.com/artwashing-gentrification-is-a-problem-but-vilifying-the-artists-involved-is-not-the-answer-83739

- Goga, S. (2003). Property investors and decentralization: A case of false competition? In R. Tomlinson, R. Beauregard, L. Bremner, & X. Mangcu (Eds.), Emerging Johannesburg: Perspectives on a Postapartheid City. Routledge 71–84.

- Gregory, J. J. (2016). Creative industries and urban regeneration: The Maboneng precinct, Johannesburg. Local Economy, 31(1–2), 158–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094215618597

- Grider, S. (1997). Graffiti. In T. A. Green (Ed.), Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Beliefs, Customs, Tales, Music, and Art (pp. 424–426). ABC-CLIO.

- Gross, D. D., & Gross, T. D. (1993). Tagging: Changing visual patterns and the rhetorical implications of a new form of graffiti. Etcetera, 50, 251–264 www.jstor.org/stable/42577458.

- Gurney, K. (2017). August House is Dead, Long Live August House! The Story of a Johannesburg Atelier. FourthWall Books.

- Halsey, M., & Pederick, B. (2010). The game of fame: Mural, graffiti, erasure. City, 14(1–2), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810903525199

- Harrison, K., & Phasha, P. (2014). Public Art: Aesthetic, Evocative and Invisible? South African Research Chair in Development Planning and Modelling.

- Ho, U. (2019). Maboneng: A new dream for a new decade. The Daily Maverick, 23 July. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-07-23-maboneng-a-new-dream-for-a-new-decade/

- Ion. (2017). The 7 main styles of graffiti. Design Like: Design News and Architecture Trends. http://designlike.com/the-7-main-styles-of-graffiti/

- JDA. (2010). Johannesburg Development Agency: Public Art, Impact Report: 2003-2010.

- Kramer, R. (2010). Painting with permission: Legal graffiti in New York City. Ethnography, 11(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466138109339122

- Kuyucu, T., & Unsal, O. (2010). “Urban transformation” as state-led property transfer: An analysis of two cases of urban renewal in Istanbul. Urban Studies Journal, 47(7), 1479–1499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009353629

- Loeffler, S. (2012). Urban warriors. Irish Arts Review, 29(1), 70–75 www.jstor.org/stable/41505657.

- MacGillivray, L., & Curwen, M. (2007). Tagging as a social literacy practice. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(5), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.50.5.3

- Mackay, T. J. (2015). Reading rebellion: Hip hop graffiti art as a public literacy text: The case of mak1one, Cape Town, South Africa. Master’s dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/19894

- Matsipa, M. (2014). The order of appearances: Urban renewal in Johannesburg. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/etd/ucb/text/Matsipa_berkeley_0028E_14115.pdf

- Morris, A. (1994). The desegregation of Hillbrow, Johannesburg, 1978-82. Urban Studies Journal, 31(6), 821–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989420080691

- Morrison, ca. 2015. “Saturated Cities: Graffiti Art in Sao Paulo and Santiago de Chile.” PhD diss., University of Cambridge.

- Nevin, A. (2014). Instant mutuality: The development of Maboneng in inner-city Johannesburg. Anthropology Southern Africa, 37(3–4), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2014.993805

- O’Sullivan, F. (2014). The pernicious realities of “artwashing”. http://www.citylab.com/housing/2014/06/the-pernicious-realities-of-artwashing/373289/. Accessed 11 March 2021

- Parker, A., Khanyile, S., & Joseph, K. (2019, March). Where Do We Draw the Line?: Graffiti in Maboneng. GCRO Occasional Paper No. 14. Johannesburg: Gauteng City-Region Observatory.

- Peck, J. (2005). Struggling with the creative class. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(4), 740–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Penfold, T. (2017). Writing the city from below: Graffiti in Johannesburg. Current Writing: Text and Reception in Southern Africa, 29(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1013929X.2017.1347429

- Pieterse, E., & Gurney, K. (2012). Johannesburg: Investing in cultural economies or publics. In Anheier, H. K. & Isar, Y. R. (Eds.), Cultures and Globalisation: Cities, Cultural Policy and Governance (pp. 194–203). Sage Publications.

- Pritchard, S. (2017). Artwashing: Social capital & anti-gentrification activism. Blog post, Colouring in Culture, 17 June. http://colouringinculture.org/blog/artwashingsocialcapitalantigentrification

- Propertuity. (2016). Maboneng: Developing a Neighbourhood Economy.

- Romero, R. (2018). Bittersweet ambivalence: Austin’s street artists speak of gentrification. Journal of Cultural Geography, 35(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2017.1338855

- Schacter, R. (2014). The ugly truth: Street art, graffiti and the creative city. Art & the Public Sphere, 3(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1386/aps.3.2.161_1

- Schacter, R. (2017). Street art is a period. Period!. In K. Avramidis & M. Tsilimpounidi (Eds.), Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (pp. 103–118). Routledge.

- Scheepers, I. (2004). Graffiti and urban space. http://www.graffiti.org/faq/scheepers_graf_urban_space.html

- Sharp, J., Pollock, V., & Paddison, R. (2005). Just art for a just city: Public art and social inclusion in urban regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(5–6), 1001–1023. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500106963

- Sitas, F. (2015). Becoming otherwise: Two thousand and ten reasons to live in a small town. PhD dissertation, University of Cape Town. https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/16559/thesis_ebe_2015_sitas_friderike.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Smith, M. R. (2017). Telltale signs: Unsanctioned graffiti interventions in post-apartheid Johannesburg. In K. Miller & B. Schmahmann (Eds.), Public Art in South Africa: Bronze Warriors and Plastic Presidents (pp. 284–304). In Indiana University Press.

- Taitz, L. (2012). The city gets a paint job from I ART JOBURG. nothing to do in Joburg besides, 11 October. http://todoinjoburg.co.za/2012/10/the-city-gets-a-paint-job-from-i-art-joburg/

- Urry, J. (2002). The Tourist Gaze. Sage Publications.

- VanMeerbeke, G. O, & Sletto, B. (2019). Graffiti takes its own space: Negotiated consent and the positionings of street artists and graffiti writers in Bogotá, Colombia. City, 23(3), 366–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2019.1646030

- Vejby, C. E. (2015). The remaking of inner city Johannesburg and the right to the city: A case study of the Maboneng precinct. Master’s dissertation, University of California. https://www.alexandria.ucsb.edu/downloads/5d86p052v

- Visser, G. (2014). The film industry and South African urban change. Urban Forum, 25(1), 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-013-9203-3

- Waddacor, C. (2014). Graffiti South Africa. Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

- Walsh, S. (2013). “We won’t move”: The suburbs take back the center in urban Johannesburg. City, 17(3), 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2013.795330

- Weisel, D. L. (2002). The problem of Graffiti. Center for Problem-Oriented Guides for Policing. Guide No. 9, U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. http://www.popcenter.org/problems/graffiti

- White, R. (2001). Graffiti, crime prevention and cultural space. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 12(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2001.12036199

- Whitehead, J. L. (2004). Graffiti: The use of the familiar. Art Education, 57(6), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/27696041

- Young, A. (2017). Art or crime or both at the same time? On the ambiguity of images in public space. In K. Avramidis & M. Tsilimpounidi (Eds.), Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (pp. 39–53). Routledge.

- Zukin, S., & Braslow, L. (2011). The life cycle of New York’s creative districts: Reflections on the unanticipated consequences of unplanned cultural zones. City, Culture and Society, 2(3), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2011.06.003