ABSTRACT

This paper explores the experiences of three Bangladeshi migrant workers who are the sole inhabitants and custodians of a former Maldivian island resort. We show how they currently remain in a state of indeterminate standby as the future of the resort remains uncertain, put in this state of limbo by the capacity of the resort’s owners to exploit their disposability and manipulability. We investigate the rich material and sensory qualities of the island, and investigate the everyday practices that characterize how the men live and work there. First, we illustrate how the island remains haunted by the workers and tourists who formerly inhabited this space, since much of the resort infrastructure remains. Second, we explore how the buildings and things on the island are unevenly intact, in a state of partial ruination. Third, we discuss how the inexpert daily maintenance practices undertaken by the three men focus on certain areas but neglect others. Finally, we emphasize that despite their uncertain future, the men endeavour to create a stable, convivial and pleasurable island home.

Resumen

Este artículo explora las experiencias de tres trabajadores migrantes de Bangladesh que son los únicos habitantes y cuidadores de un antiguo resort turístico en una isla de las Maldivas. Mostramos cómo actualmente permanecen en un estado de espera indeterminado mientras el futuro del complejo sigue siendo incierto, puesto en este estado de limbo por la capacidad de los propietarios del complejo de explotar su disponibilidad y su capacidad de ser modificado. Investigamos las ricas cualidades materiales y sensoriales de la isla, e investigamos las prácticas cotidianas que caracterizan cómo viven y trabajan los hombres allí. Primero, ilustramos cómo la isla sigue siendo acosada por los trabajadores y turistas que habitaban este espacio, ya que gran parte de la infraestructura turística permanece. En segundo lugar, exploramos cómo los edificios y otras cosas en la isla están intactos de manera desigual, en un estado de ruina parcial. En tercer lugar, analizamos cómo las inexpertas prácticas de mantenimiento diario llevadas a cabo por los tres hombres se centran en ciertas áreas, pero descuidan otras. Finalmente, destacamos que, a pesar de su futuro incierto, los hombres se esfuerzan por crear un hogar isleño estable, agradable y placentero.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article se penche sur les expériences de trois employés migrants originaires du Bangladesh qui sont les seuls habitants et gardiens d’une ancienne île-hôtel aux Maldives. Nous présentons leur situation actuelle, en attente indéterminée, due à l’avenir incertain du complexe touristique, placés dans cet état aléatoire par le pouvoir d’exploiter leur disponibilité et leur manipulabilité que possèdent les propriétaires des lieux. Nous étudions les riches qualités concrètes et sensorielles de l’île, et recherchons les pratiques quotidiennes qui caractérisent la façon dont ces hommes y vivent et y travaillent. Premièrement, nous montrons comment ce lieu reste peuplé par les employés et les clients qui l’ont occupé auparavant, puisque la grande majorité de son infrastructure est encore là. Deuxièmement, nous examinons le fait que les bâtiments et les objets installés sur l’île sont conservés de manière inégale, partiellement en état de ruine. Troisièmement, nous soulevons la question des pratiques d’entretien journalier sans expertise des trois hommes qui se concentrent sur certaines choses, mais en négligent d’autres. Pour finir, nous clarifions que, malgré leur avenir incertain, ces hommes s’efforcent de faire de l’île un endroit de vie stable, convivial et agréable.

Standing by: three men on a small island

Living in a rundown holiday resort, three men remain as the custodians and sole inhabitants of a tiny island in the Indian Ocean. The resort closed in 2016 following bitter conflict between the two owners, primarily over the division of their shareholdings. While they fight their case in the courts, three Bangladeshi workers, formerly employed by the resort, were persuaded to remain on the island to maintain a semblance of order by attending to the upkeep of the beach, trees, chalets, water sports equipment and gardens so that perhaps one day, the resort might reopen. The men’s encounters with this island space take place amidst crumbling walls, peeling paint, colonizing mould and uprooted trees, set within a dynamic, mobile island ecology of salt spray, tides, currents and storm surges, wind, monsoons and intense humidity. The island, around 180 metres long and 100 metres wide, is fringed by a lagoon protected by a coral reef some 20 metres beyond its glistening white beaches. Much of the space is covered by a thick spread of shrubs, trees and sea grasses including Magoo (Sea Lettuce/Scaevola), Dhigga (Sea Hibiscus), Hirudhu (Portia Tree/Pacific rosewood), Kuredhi (ironwood), Kaani (sea trumpet tree) and numerous palm trees.

Opening in 1981, it was one of the oldest resorts in the Maldives and one of the smallest and most informal. Unlike most Maldivian luxury resorts, its touristic appeal offered a sense of isolation and a more intimate encounter with a tropical island environment. Accommodation consisted of 30 chalets, each with a veranda facing the sea, basically furnished, without air conditioning, television or hot water (see ). A single central building combined reception, bar and restaurant areas and there was a separate, small diving centre. All buildings have been designed using local wood, coir rope, screw-pine matting and corrugated iron sheet roofing.

The resort was predominantly frequented by Italian tourists, many repeat holidaymakers, who had little interest in fishing or seeing dolphins and were more concerned with swimming and relaxation. Any requests for diving or fishing would be arranged but the resort did not actively market these activities. Here, the emphasis was on a less insulated confrontation with sensations generated by non-human forces: tides, breezes, humidity and swaying palms. At the height of the tourist season, 45 members of staff, mainly Maldivians, Sri Lankans and Bangladeshis, lived in three dormitories allotted to each nationality, while the boat launch crew, the captain and the diving team were accommodated in smaller individual rooms.

As the conflict between the two owners intensified, new bookings ceased and tourist numbers dwindled. The workers gradually left, most returning to Sri Lanka and Bangladesh or taking up employment in other Maldivian resorts. Following closure in 2016, only the three Bangladeshi workers, Mohammed, Ahmed and Hassan, all in their mid-40s, remained. They had arrived at the resort more than 17 years previously to work as cleaners and kitchen assistants but since its closure, have been tasked with the basic maintenance of the resort and island environment. They are each paid $US 200/month and were persuaded to stay on with the promise that if the resort reopens, they will be given good jobs while if it is sold they will each receive a large bonus, assurances that have kept them there. Yet, six years on, the three men are beginning to feel doubtful that they will ever receive a lump sum or that the resort will reopen. Additionally, since the Ministry of Tourism retracted the resort’s operations licence, their work visas have expired along with their passports; they have no legal documents and remain trapped, unable to leave the island and country. Each remains fearful that the other two will receive their travel documents, and they will be left behind on their own. The manager of a guest house on a neighbouring island manages the site and oversees the three workers on behalf of the owners, sometimes accruing extra income by bringing visitors to the island for picnics and barbecues. Every two or three weeks, or more frequently if required, he brings provisions of food, toiletries and cleaning supplies for the workers as well as sim cards.

The Maldives, a small-island state in the Indian Ocean, is an archipelago of around 1200 islands. It has a population of approximately 560,000 inhabiting 188 of these islands, a third residing on just one island, the capital Malé (United Nations Development Programme, Citation2020). Maldives has become renowned as a luxury destination for international tourists, attracting over 1.6 million annually. Tourism, accounts for approximately 25% of Maldives’ GDP (Ministry of Tourism, Citation2019). This renders the country particularly susceptible to global economic vagaries in addition to various on-going political, social and environmental challenges, notably its vulnerability to climate change and sea-level rise (McMichael et al., Citation2021) that cause storm damage, tidal incursion and activate other vibrant non-human agencies.

The Maldivian economy is largely sustained by employing migrant workers, estimated to number between 145,000 and 230,000 (UNDP, Citation2020), mostly unskilled and semi-skilled men aged between 20 and 34 from Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka working in the hospitality and construction industries. Estimates suggest that at least 65,000 are undocumented. The labour-intensive tourist sector is particularly reliant on migrant workers. The discrimination, mistreatment, economic exploitation and poor working and living conditions that they have suffered are well-documented (Bentz & Carsignol, Citation2021; International Organisation of Migration, Citation2019; Mohamed, Citation2021). In the Maldives, 130 ‘uninhabited’ islands, like the island discussed in this paper, are currently the location for holiday resorts (Ministry of Tourism Maldives, Citation2019), all advertised as idealized tropical islands replete with pristine beaches and clear water lagoons (Kothari & Arnall, Citation2020).

Research for the paper was carried out on six visits to the island between 2020 and 2022. Each time we were accompanied by a Maldivian research assistant and on one occasion by a member of the local council of a neighbouring island who was concerned about the three men’s mental health and welfare. Though the prolonged uncertainty about their future and continued sequestration on the island was beginning to promote some anxiety, the men remained largely upbeat and were always delighted by our visits, appreciating the company and the opportunity to share their concerns, experiences and everyday practices. We adopted the ‘go-along’ (Kusenbach, Citation2003) technique of data collection, asking questions as we moved alongside the men as they actively inhabited their maintenance routes and homely spaces and showed us sites of ruination and upkeep and described life when the resort was fully functioning. Much time was spent learning about their former and current lives as they showed us around the island and afterwards, as we sat together and recorded conversations at a slower pace. To supplement the information gathered from speaking with the three men, photographs visually document the physical landscape and the men’s everyday practices. As well as illustrating features described in the text, these photographs, all taken by the authors, offer a sense of the character, scale and location of the island and act as another source of data by providing powerful depictions of an environment thoroughly shaped by non-human and human encounters.

Most interviews were conducted in Dhivehi and later translated into English; some were recorded and subsequently transcribed whereas others were conducted more informally and later written up in a field diary. During the fieldwork, the ethical guidelines of the authors’ home institutions were adhered at all times, and the standard procedures and practices were followed in the Maldives to gain access. To protect the anonymity of the men, we have given them pseudonyms and avoided referring to the island by name or providing a map.

This paper argues that the island resort and the men currently remain in a state of indeterminate standby. Kemmer et al. (Citation2021, pp. 1–2) contend that standby ‘acts as an ordinary mode of organizing sociomaterial lifeworlds’ by mobilizing a ‘capacity to create, regulate, and synchronize heterogeneous formations of people, things, natural elements, and technologies’ and ensure their availability and disposability. This power to keep people, spaces and things in limbo, dormant but ready for action, also includes modes of keeping places ticking over in case they can be revived and generate future profitability. With an abundant supply of manipulable, disposable migrant labour, the potential to organize diverse modes of standby inheres in the political economy of Maldives tourism, facilitating flexible managerial responses to resort evacuation and periods of economic slow-down.

The paper primarily focuses upon how maintenance is undertaken within a context of indeterminate standby and prodigious non-human flourishing, expanding conceptual understandings of both standby and maintenance. We first explore how, because the men worked on the resort when it was operational, they experience the profound absences triggered by its extant material fabric and visions of its future reopening. Second, we identify the profuse non-human agencies that ceaselessly transform the island and resort, and that demand responses that keep ruination at bay and preserve a semblance of material and spatial order. Third, we investigate how particular forms of everyday maintenance take place under conditions of indeterminate standby within this dynamic environment and how this shapes the work that the men undertake. Accordingly, we illuminate how human and non-human agencies and (im)mobilities are intimately entangled in particular ways on the island. Finally, we explore the men’s relationships with each other and how they make a home on the island despite living under conditions of precarity and uncertainty.

Ghosts and vestiges: absences, silence, haunting, echoes

The ‘pluritemporal landscape’ (Crang & Travlou, Citation2001) of the currently dormant resort is both troubled by the spectre of future dissolution and remains powerfully haunted by memories of its recent tourist occupation. The resort has become detached from the networks of travel and tourism that once supported it, along which workers, tourists and supplies moved to and from the island. These are not enigmatic or indecipherable traces of the past (Edensor, Citation2005a) for their prior functions are evident. While numerous remnants have become detached from the tourist milieux that gave them meaning and purpose, they linger to interrupt the experiential flow of the present, triggering memories, social connections and sensations (Crewe, Citation2011).

Elements of the material legacy of the past reverberate across the island and throughout the day at moments of encounter. Numerous tourism related objects litter the former resort and its unoccupied buildings, summoning melancholic and nostalgic memories. The men are enfolded into a space replete with multiple traces of the holiday-makers who populated the island only a few years previously. As Ahmed wistfully exclaimed, ‘I still feel sad every time I pass the dining room, it was always such a happy place with tourists eating, drinking and laughing. There was a lot of noise, lots of shouting’. Similarly, a plethora of objects are stored, used, repurposed or uselessly linger. Together they constitute the ‘marks, residues or remnants left in place’ by an earlier and different cultural life (Anderson, Citation2015, p. 4). Yet, many things are not akin to Justin Armstrong’s (Citation2020) rural remnants in which material ruin signifies abandonment, the definitive end of usage. While some objects do decay and are not replenished, others remain redundant but linger in storage spaces or in plain sight or have been repurposed. And the possibility remains that many of these dormant objects will once more become used if the resort rises from its current redundancy.

The animated energies of holidaymakers and workers who formerly thronged the resort are affectively and sensorially marked by their absence, and this is especially heightened during the prolonged periods of silence that currently pervade life on the island. When the tide recedes, birdsong ceases and the wind subsides, the island is very quiet indeed: there is nobody in the bar to clink glasses together, no bartenders supply drinks, no waiters serve food, and no chatter or music wafts through the space. The spatial and material remains conjure up a recent past when guests wrapped in towels and sporting flip flops after a dip in the sea thirstily downed drinks at the beach tables. On the beaches, no gaggles of children cluster by the waterside, no adult bodies lie prone on the sun loungers and no talkative people weave between the palm trees. Yet, while a dream holiday world might have vanished, the multiple vestiges convey a sense that it might return.

The everyday rhythms of the holiday resort have been replaced by the quotidian routines of the three workers who quietly move across the island. Having been employed as part of a much larger team of workers when the resort was thriving, the men discuss inhabiting the kitchen, now bereft of the hustle and bustle of those who once animated the space. As Mohammed recounted, ‘I enjoyed being busy, surrounded by the other workers. It was really hard work, but I liked being in the kitchen with the chef and the other waiters, the smell of the food cooking, the clanging of the pans’. The men explain that this space in particular invokes memories and nostalgic sentiments that are also triggered by the scratches made long ago on the metal stove top and the industrial size cooking pots in which food was prepared. These remembered sensations and socialities sometimes cause them to lapse into a melancholic mood. As Mohammed continues, ‘the other day, I was sitting on the small wall of the bar area looking at the empty tables on the beach and it made me sad. I remember all the nice people I met from other countries; now it feels lonely, just me and my two friends’.

The restaurant and bar area, largely intact from resort times, are especially awash with extant utensils, receptacles and storage containers, some of which the men still use, while others are stored to await possible future use. A larder is crammed with dusty jam jars and plastic honey pots, large cooking vessels (see ), stores of food cans and kitchen implements, and numerous metal toast racks and porcelain platters. On the terrace outside the bar reside a collection of rusting metal towel racks that would have been allotted to each chalet (see ). A faded lunch menu and a flyer specifying mealtimes are still pinned to the notice board on the dining room wall, accompanied by other informational notices about the cost of drinks and the excursions offered by the resort. These act as a reminder that besides being sites of pleasure and relaxation, regulatory procedures also necessarily guide the running of such tourist realms.

Figure 2. a. Stored large pots and pans in the kitchen (photo by authors). b. Rows of drying racks in the kitchen (photo by authors) c. Reception area (photo by authors) d. Circular outdoor tables (photo by authors) e. Piles of sun loungers (photo by authors).

In the reception area, several promotional paraphernalia and decorations remain. Placed upon the reception desk is a wooden sculpture of two cavorting dolphins, a rather shapely piece of driftwood that glistens with varnish, and a lumpy piece of coral, peculiar forms that presumably reflected the idiosyncratic tastes of the managers. A large noticeboard is plastered with dozens of colourful tourist stickers that recollect that the resort was once part of a wider network of travel and tourism. On the walls hang a design of an idealized tropical island, a painted mural of two angel fish and sea vegetation, and wrought iron decorations. In an adjacent room, four large colourful posters portray the sea life that surrounds the island, adding to the visual enticements devised to foster a holiday atmosphere. A wall clock has stopped at the time of 5:24, and a wooden post-box from which mail is no longer sent indicates the next collection time. Although no longer functional, these items literally and starkly summon up another time (see ).

Most of the chalets are uninhabited but sufficiently intact to conjure up the reclining bodies of the former tourists who resided here for a week or two. Outside, a disused stone water tower and a small empty hut from which diving equipment was dispensed have no current purpose. A group of circular concrete tables remain under the shapely palms, their red paint peeling away. Sometimes the men sit amongst them but usually this is an unoccupied space (see ). Amidst an area of thick vegetation, a boat lies covered with a tarpaulin. Redundant fibreglass sun loungers are stacked in piles (see ), bleached by the sun. Cracked surf boards and damaged snorkelling equipment are scattered amongst flippers, wetsuits and other diving equipment. Hammocks, some intact, some with expanding holes in their netting, are slung between palm trees, and a torn volleyball net remains in place. These features summon up lounging, leaping, sitting and swimming bodies. Non-human bodies are also absent in the large container, now rusting, that served as a home for small turtles when the resort signed up to a turtle protection project.

The people, noise and activities that once enlivened the island are now absent, yet many of the buildings, spaces and objects remain, making the island recognizable as a tourist resort. For the casual visitor, however, this past cannot be recuperated in ‘any official or exact sense’ (DeSilvey & Edensor, Citation2013, p. 7); for us the objects and spaces carry intimations of what happened here, but we lack the direct experiences of the men and so our imaginations are largely triggered by mediatized representations of island holiday resorts. While the material traces conjure scenes that are vaguely recognizable, they can only summon up a partial sense of what happened here. For us, the resort’s past is elusive and fragmented, mysterious and ineffable, because it is confined to imaginative speculation (Edensor, Citation2005a). Yet for the men, having worked here when the resort was operational, these traces activate memories that were part of daily experience, tethering the resort and themselves to its recent past, supplementing the sense that this is a space in limbo. These haunted effects may endure for some time yet, depending upon decisions about the island’s future and the extent to which this temporal span will condition how ruination proceeds.

Ruination and non-human agency

DeSilvey and Edensor (Citation2013, p. 3) identify an ‘intensification of academic and popular interest in the ruins of the recent past and associated realms of dereliction’. Numerous contemporary accounts focus on industrial, rural, domestic, post-colonial and post-socialist abandoned and ruinous sites. Some celebrate them as contrary to normative spatially ordering impulses, as sites at which intimations of the past swarm and coagulate, and as replete with a distinctive array of sensations. Yet, while the agencies of decay are active on the island and the resort is slowly deteriorating, the care and upkeep performed by the three custodians mean that the island is only partly and unevenly ruined. It remains inhabited, partially intact and eminently recognizable as a tourist destination in which former activities have been paused. A sense of uncertain future and a state of indefinite standby is animated by the form and extent of this ruination.

Ruinous processes take place at different rates, under diverse economic, historical, geographical, environmental and cultural conditions, according to their material components, and in accordance with the various acts and agencies of humans and non-humans. The island resort, and specifically the buildings, may variously be considered to be in the process of becoming a ruin, as already a partial ruin, or as a site at which ruination is being and will be curtailed. Perhaps the chalets and other buildings will be repurposed, amended, redecorated, ceaselessly maintained to ensure their continuing integrity - or they will be demolished. This resonates with Ingold and Hallam’s (Citation2007, p. 4) observation that buildings are ‘continually modified and adapted to fit in with manifold and ever shifting purposes’. But all buildings, as Tait and While (Citation2009, p. 6) emphasize, irrespective of human designs, are ‘morphogenetic figures forged in time, tacking against a general entropic tendency’. Particular rates of ruination depend upon the materials out of which a building has been made and their capacities to adhere together over time as a stable assemblage (Edensor, Citation2011). Their destiny is also profoundly shaped by the effects of the non-human agencies that swirl around them. On the island resort, these exigencies of the non-human environment are acutely felt and vividly evident, and solicit thoughts of a post-human future for the island and beyond.

The island structures, like all buildings, are hybrid, composed of a heterogeneous, often changing collection of components that are forms of ‘vibrant matter’ (Bennett, Citation2010): they are not static elements but possess ‘incipient tendencies’ to self-arrange and are variously impacted upon by the other forces, affects or bodies with which they come into contact. As dynamic, processual entities, the numerous components out of which buildings are constituted have their own vibrant qualities that decay or mutate within the assemblage and interact in dynamic ways with other constituents, shaping the speed of ruination and decay. On the island, the concrete walls are embedded with stone and surfaced with plasterboard with minimal interior metal reinforcements. Corrugated iron roofs, tiled floors and timber frames and joists constitute other primary materials and while these materials are not particularly sturdy or resilient, in sheltered locations they can remain fairly durable. However, where they are exposed, they are more fragile.

The most obvious threat to the integrity of buildings is weather, although climatic conditions vary enormously. Tim Winter (Citation2004) explains how plentiful rain and humidity wreak havoc on the constitution of Cambodia’s Angkor Wat temple complex and provide rich conditions for bacteria, plants and other agents to work away at stony matter. The tropical climate of the Maldives similarly provides humidity and warmth; during the monsoon season, the saturation of plaster walls encourages the colonization of biofilms and weakens areas where water pools.

On the island, a combination of wind, rain, sand and salt unleashes powerful erosive forces. Gillon and Gibbs (Citation2019) detail how salt-laden winds and abrasive sand at seaside housing complexes in New South Wales, Australia, settle on and corrode surfaces, creating blemishes and speeding up decay. Similarly, on the resort island, sand enters cracks and settles in interiors, and salt penetrates matter and erodes it from within. The effects of salt and moisture are uneven across the island depending on the porosity of the materials. Plaster can be somewhat resistant to rapid deterioration, although on some of the surfaces of the buildings, diverse stains have added an unexpected array of colourful patterns caused by the biofilms that exploit wet matter. This exemplifies how building assemblages are habitats for myriad non-humans who colonize them to feed, reproduce and seek shelter. Particular species seek out the succouring qualities of chemistry, temperature, humidity and light, with plants exploiting moist cracks in surfaces, enlarging their dimensions and securing footholds. On this tropical island, botanical growth is rapid and any suspension of maintenance leads to the opportunistic colonization of building fabric.

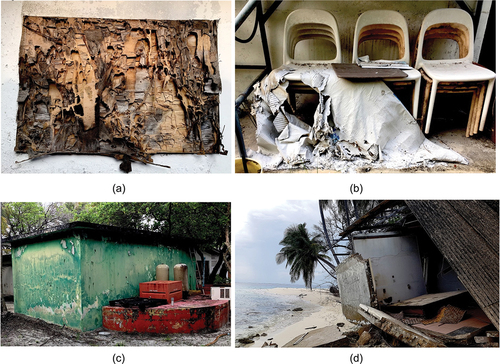

Certain material elements have been left to decay as disclosed by elaborate patterns of warping, peeling and mouldering. Concrete cracks, plaster crumbles and paint blisters. Other surfaces and materials have more gradually changed in appearance, subject to a variety of happenstance designs wrought by biotic and chemical agencies. A plywood signboard, now illegible, has given up its form and solidity over time, forming intricate ornamentation across its divergently degenerated layers (see ). A detached section of rubberized flooring lies on the sand, its black hues augmented by white blotches. A bag of plaster left outside and soaked is now solid and has melded with a stack of plastic chairs (see ). Some white plastered walls have become progressively cracked and smeared in diverse palettes of colour. Paint has become discoloured and reveals undercoats and earlier layers. A shed, formerly of uniform colour, is now adorned in a medley of green shades (see ). On another wall, blue wall piping is now complemented by the oozing pink hues that seep through the white painted surface. On one chalet, a pillar has lost its plaster surface to expose rough, lumpy aggregations of stone and concrete. At various locations, accumulated combinations of material have been placed into tidy piles as if the men are unsure about whether they may retain some future utility: differently sized fragments of corrugated roofing, fibreglass segments of a boat, coils of unused plastic tubing, snorkelling masks residing in a rusty bucket in the work shed. These emergent forms highlight how human action, neglect and non-human agency can transform the familiar material world, ‘changing the form and texture of objects, eroding their assigned functions and meanings, and blurring the boundaries between things’ (Edensor, Citation2005b, p. 318).

Figure 3. a. Decaying noticeboard (photo by authors) b. Plaster and chairs (source: authors) c. Discoloured green paint (source: authors) d. Destroyed chalet (source: authors).

These agencies of decay and deterioration are sometimes slow, gradual and incremental, yet certain non-human forces are unpredictable, and on the island, these have culminated in the rapid destruction of some structures. Violent storms carry untethered matter and scatter branches and palm fronds across the island, while exacerbating the corrosive power of sand. More destructive are the tidal swells that engulf parts of the island, swiftly obliterating chalets and uprooting trees. One chalet has shifted so that it periodically lies half in the sea, while another has been destroyed by wave power, its material components reorganized in a chaotic arrangement (see ) producing a defamilarized landscape. Those elements formerly hidden – the stones within the concrete walls, the concealed wires and pipes, the timber supports, the plasterboard affixed to interior walls – are splayed out of place and reveal the process of construction. Roof timbers and pipes mingle in unruly arrangements, walls tilt at various angles, corrugated iron roofs lay strewn alongside. The pier that provides access to boats is crumbling and might collapse in the face of tidal surges; indeed, Ahmed reported that around 50 ft of land on one side of the island has disappeared over the past six years. The texture and appearance of these distressed, deteriorating materialities foregrounds an emergent aesthetics as familiar fixtures are reorganized, becoming strange and enigmatic, contravening rectilinear perspectives and assuming sculptural form (Edensor, Citation2005b). But these shattered structures may also foretell of the fate of the remaining chalets if a future storm arrives or if maintenance ceases.

Salt spray, tides, storms, wind, monsoons, humidity, shifting sands, botanical fecundity and creaturely colonization have produced a particularly fluid material place, one in which extensive ruination and durable stasis coexist, producing diverse aesthetic effects. The resort thus provides an assortment of contrasting tactile, aromatic and visual pleasures amidst the already potent sensorial tropical environment. To move across the island and within the buildings is to experience a medley of shifting sensations. The orderly contrasts with the degenerative to produce a sensuous profusion that offers a haptic and visual apprehension of intact and smooth surfaces as well as objects and planes that have been disfigured and warped. While powerful ruinous sensations cannot be wholly expunged, in certain areas they are more strictly regulated. The smooth, cleansed counter of the bar, freshly painted walls and swept sand contrast with the tactile qualities of crumbling plaster and the visual riot of layers of wall paint. There is no confrontation with the scent of rot or carrion, or of the utter collapse and material mingling that would be found in a ruin left alone to the unpredictable effects of entropic forces. This is a space that combines the far-from-ruinous with the derelict, for the resort is a partially maintained, regulated space, as we now discuss.

Maintenance and indeterminate standby

The destructive agencies of salt spray, tides, storms and sand requires particular kinds of ongoing cleaning and clearing. While like all buildings, those on the island are incessantly falling apart, some slowly, others more quickly, a low-level maintenance regime ensures that most foundational structures remain somewhat intact. As Denis et al. (Citation2015, p. 9) emphasize, maintenance and ‘repair is at the heart of a continuous process that includes patching up, reconfiguring, interpolating, and reassembling settings from previous forms of existence’. In all places, if maintenance and repair is not systematically and regularly undertaken, environments are threatened by ruination, some at a more rapid rate than others (Edensor, Citation2016). Inhabited and well-used buildings require the performance of a range of practices that ensure they do not become disordered. Cairns and Jacobs (Citation2014, p. 82) aptly claim that ‘maintenance and repair is part of the social work that is required to offset the entropic destiny of the world’, what Solnit (Citation2006, p. 89) refers to as ‘the incremental processes of rot, erosion, rust, the microbial breakdown of concrete, stone, wood, and brick, the return of plants and animals making their own complex order’. These unheralded, mundane, practices are disclosed by their absence when buildings that have been abandoned start to fall apart.

Maintenance enlists a compendium of techniques, procedures and institutions, but is critically informed by the making of judgements. Such estimations focus upon whether structures have outlived their usefulness, should be repaired or are considered beyond repair, ought to be subject to continual maintenance, possess or lack esteemed aesthetic or symbolic qualities, or have retained or lost their function. According to prevailing values and strategies, some structures are assiduously maintained whereas others are neglected. Maintenance on the island currently takes place because contingent decisions have been made by the resort owners that the buildings should endure – for the time being. The cost of labour is cheap and so the expenditure is not onerous. Moreover, perhaps this is also because, as DeSilvey (Citation2017, p. 15) asserts, it can be difficult ‘to step back and allow things to collapse’ for ‘the urge to step in at the last minute to avert material disintegration is a powerful one’, and this impulse has fostered a desire to retain the material integrity of the resort.

Formerly subject to successive flows of tourists, workers, fuel and sustenance to and from the resort that required regular maintenance work when the resort was occupied by tourists, current maintenance follows a different temporal arrangement whereby the three men seek to hold entropy at bay through different practices of everyday upkeep. This shift in maintenance recalls Massey’s (Citation1995, p. 139) contention that place is a setting for negotiations between human and non-human actors that form, ‘conjunctures of trajectories which have their own temporalities … where the successions of meetings, the accumulations of weaving and encounters build up a history’. Relationships between humans and non-humans have been reconfigured on the island because of volatile economic and business contingencies alongside a desire for a semblance of material and spatial order to persist, at least for a while.

To emphasize, the enaction of maintenance is undertaken according to different temporalities and with different futures in mind.; sometimes things are contingently held together, at other times, a more permanent state of affairs is sought through systematic, scheduled practices. Denis and Pontille (Citation2023; also see Jackson, Citation2014) critique what they regard as a disproportionate focus on the mobilization of repair following episodes of breakdown, after which the normal socio-material order of things is re-established. They contend that the centrality of everyday maintenance routines are overlooked, as for instance with the cleaning schedules identified by Strebel (Citation2011) and the repetitive everyday maintenance described by Gillon and Gibbs (Citation2019, p. 105) through which residents in coastal housing developments undertake so that ‘home can endure in place’. While the shift in maintenance practices at the resort has resulted from a breakdown in relationships between the owners, the adoption of the mundane, daily maintenance routines by the three island inhabitants testifies to an attuned commitment to attentive caring. Through their routine choreographies, Mohammed, Ahmed and Hassan contingently carry out immediate maintenance, identify work to be completed later and register that which they cannot restore.

In some respects, this repeated daily maintenance resembles practices of standby. Indeed, standby is integral to many of the rhythms of tourism, as holiday seasons end and practices of refurbishment, repair and maintenance are enacted in the off season to prepare for the next seasonal influx of tourists. Things must be kept ticking over. Yet on the island at present, there is no definitive future point at which tourists will once more occupy the resort; however, the possibility that tourists may return means that things must be kept in order. The owners hold onto the hope that the enterprise will once more be up and running in the near future but are presently unable to commit to substantive refurbishing and marketing. In the midst of their business squabble, it has been important to banish a sense of ambiguity about the future through these standby maintenance procedures. Nonetheless, processes through which certain destinations become obsolescent, suddenly fashionable or popular after years of decline are endemic to the tourist industry, compounding uncertainty about the resort’s destiny.

As Kemmer et al. (Citation2021, p. 5) point out, standby has historically been performed by ‘on-demand’ seasonal and day workers and this aligns with the position of Bangladeshi workers throughout the Maldives who usually ‘must take whatever short-term work they can find, whenever they can find it’ as a means to cope with ‘detrimental material and social conditions’. Yet unlike most practices of standby during which things are maintained in a state of preparedness for a predictable, scheduled return to work, occupation or passage, for Mohammed, Hasan and Ahmed there is no obvious end point to their daily endeavours. Their work lacks the regular, systematic rhythms typical of other forms of standby, and they have become disconnected from the seasonal tourist rhythms which once prevailed. They remain adrift in a kind of indeterminate stuckness, though there is a possibility that the resort may be reopened for business; alternatively, it might be demolished, discarded or repurposed. This uncertainty also means that there is the prospect that maintenance will cease, and things will commence the transition from ‘an artefact – a relic of human manipulation of the material world’ to ‘an ecofact – a relic of other-than-human engagements with matter, climate, weather, and biology’ (DeSilvey, Citation2006, p. 223). If this happens, these objects and buildings will transition into very different objects and then become nothing discrete at all. Here, the ongoing remaking of the island will devolve to the non-human, to the tides, winds, chemicals, fauna and flora that are currently partly curtailed in their work.

At present, the men adopt a pragmatic approach and accept that they cannot repair suddenly destroyed objects or arrest major processes of denudation, such as the slow crumbling of the pier. Non-human agencies are less constrained for three workers provide insufficient labour power to maintain the resort as it once was. Nonetheless, they enact a subtle attentiveness to the site through ongoing ordering and making do. They do not intentionally practice ‘curated decay’ (DeSilvey, Citation2017) but certain spaces are privileged over others, with restaurant and bar areas far more diligently maintained than some chalets, producing a landscape of uneven decay and intactness. Some wall surfaces are permitted to become discoloured or colonized by biofilms and moss. It would be too strenuous to maintain the level of appearance demanded when the resort was inhabited by tourists, although such deterioration is rarely allowed to proceed to the point of no return. Even where structures have been demolished, some semblance of order remains with building materials scattered by the tide organized into neat piles. Unlike in other ruinous settings, objects and structures do not chaotically mingle with each other and unusual juxtapositions are less likely to arise (Edensor, Citation2005b). Yet these devastated buildings and objects do conjure up a future in which all island structures might be levelled by future storms and tidal incursions. In an era of sea level rise, these practices of conditional maintenance could be rendered futile at any time.

The endless maintenance of the material world depends upon the rhythms of maintenance to produce continuity and stability (Graham & Thrift, Citation2007). The three men attempt to ensure that matter is confined to its ‘proper’ place, and that non-human effects are managed and controlled, but their capacity to prevent decay and erasure is limited under the conditions of indeterminate standby. We now more substantively discuss the assiduous performance of their routine maintenance work and how this is combined with the everyday business of living on the island, of making it a homely, comfortable and enjoyable place in which to reside while they wait for an uncertain future to unfold.

Daily living: managing place, making home

Straughan et al. (Citation2020, p. 637) aptly note that ‘temporal immobilisation hinders the ability of people to undertake future-orientated actions and, subsequently, their ability to plan for and control the course of their own lives’. This is certainly the case with the three men on the island, unable to depart or make future plans, yet they make a life in the here and now. Neither immobilized, static nor disheartened by the duties with which they are entrusted, they have developed a sense of home characterized by domestic tasks and recreational pleasures, routines that supplement their work. These resourceful, creative, social and home-making practices include their repurposing of particular island spaces.

When employed as part of a large team servicing tourists, the men undertook very different work routines, but these rhythms and schedules have changed utterly. Now their daily work focuses upon keeping a semblance of order through repeatedly attending to the upkeep of trees, chalets and communal buildings, doing their best to resist the effects of slow material decay and botanical fecundity.

Hasan described their daily maintenance routine,

Each day we wake up early and walk around the island to make sure no intruders have landed overnight. We then go to the kitchen to make tea and eat breakfast before going outside again so we can deal with anything that has happened in the night. First, we clear all the rubbish that has blown across the paths. We collect the leaves, the palm fronds and branches and put them in a big pile. And we sweep all the smaller things that have fallen on the sand, like little berries and fruits from the trees. Later on, we burn these. We always have to check the pier because it’s often been washed over with large waves, so it’s covered with sand, and we have to clear that away. So, because things have got blown around, we have to put them back into their place. Then we repair equipment and building materials. Next, we go into each of the chalets because there are big gaps under the doors and the windows, so we have to sweep the sand out. And every day we go to the beach to check for rubbish that might have been deposited by the tide.

The rhythms of these quotidian maintenance routines are not predictable; can never be exactly repeated for their work is shaped by the exigencies of the ever-changing, fluctuating forces of non-human agents, the wind, tides, monsoons, plants and creatures. Besides the contingencies produced by their own bodies – whether they feel sick, despondent or tired – such routine rhythms are characterized by Lefebvre’s (Citation2004, p. 6) insistence that ‘there is always something new and unforeseen that introduces itself into the repetitive’. Often major, one-off repairs are required: the generator has broken down, a roof is becoming detached, the rotting corpse of a sea creature needs to be removed from the sand. Strewn building material from a demolished chalet needs to be tidily arranged. The men care for the resort slowly and kindly, feeling responsible for holding it in place and express satisfaction towards by their tasks. This work is especially sensual in its manifold encounters with non-human agencies, taking place amidst the caress of gentle breezes, the sounds of lapping waves, the sway of the trees and the relentless heat, and it is performed in an atmosphere of conviviality and peacefulness. Besides these work responsibilities, the men have organized their everyday lives around living and leisure practices that are distributed across a variety of island spaces.

Though the men could choose a range of chalets in which to sleep and organize their possessions, they maintain the arrangements that were made when the resort was operational: they remain in the far less spacious dormitory room allotted to Bangladeshi members of staff. Each occupies the lower bunk of one of the beds, using the top bunk to store their personal belongings. To do otherwise, they suggest, would make them feel disorientated, bereft and lonesome. As Hassan explains, ‘we are used to sleeping in this room, this is where we have always been. And we don’t want to stay separate, I wouldn’t like that, I would feel lonely’. Other long-standing arrangements also pertain. A small building close to their living quarters that is always diligently maintained serves as a mosque. The men are punctual about observing prayer times here, a practice that further gives shape to their day.

At mealtimes, the men use the industrial sized kitchen that was designed to provide food for dozens of tourists and remains furnished with a plethora of big cooking utensils and receptacles. They boil rice in oversized pots and fry in large pans, ensuring that these objects are kept clean and in working order. These objects and spaces have a cultural biography, but are also endowed with new meanings, and are reassembled to constitute the facilities necessary for the maintenance of daily washing and cleaning. Outside, a rather distressed plastic chair has been placed beneath a broken mirror that hangs from two rusty nails to create a makeshift ‘barber’ area where they shave and cut each other’s hair (see ). Nearby a washing line is supported by a spindly branch. Less communal in purpose is the small shack on the west side of the island constructed by the men out of driftwood. Erected at the only site at which it is possible to receive a phone signal, a cushion provides a measure of comfort while they communicate in privacy with their far-distant families.

Figure 4. a. Shaving area (photo by authors) b. Weights in the makeshift gym (photo by authors) c. Resort garden (photo by authors).

These functional spaces are supplemented by others that have been adapted for leisurely purposes. A veranda of one of the buildings has been modified to house a vernacular gym. Here, the men have created dumb bells, free weights and barbells out of empty cooking oil containers and tins of tomatoes of varying sizes, filling them with sand. Metal bars have been inserted into the tins which have then been set in concrete (see ). In addition, the men take great pride in a garden they have crafted, deploying old pots and containers to house an array of blooms and saplings. Mohammed enthusiastically reports that, ‘watering the garden and seeing how the flowers have grown is my favourite part of the day’ (see ). Using various receptacles to collect rainwater, they water the plants daily, participating in a shared project that generates important moments of creativity, delight and conviviality.

Islandness (Bocco, Citation2016) shapes the three workers’ everyday lives and their sense of well-being. On many days they experience a contented solitude and freedom, relishing the opportunities for contemplation and the absence of social interruption. At other times, they feel distant, isolated and disconnected, a sense of geographical remoteness heightened by memories and absences. Yet, the island does remain connected; it is part of extended social and spatial networks (Massey, Citation1995), though these connections have been reconfigured to be less regular, less numerous and more fragile than when the resort was operational (Kemmer et al., Citation2021). They remain connected with family in Bangladesh by telephone. Provisions of food and essentials are regularly delivered by boat from a nearby inhabited island to supplement the tinned food items that remain in the island stores and the fish the men catch. They also require supplies of materials for maintenance work, such as paint. In addition, their daily routines are often augmented when other tourists pay the manager to visit the island.

Critically, however, whether they are feeling detached or connected to the world beyond the island, the men are good friends; they care for and look after each other. As Ahmed declares, ‘these are my friends, why would we argue, we are friends. We only have each other’. Adapting their days to the seasons, the weather and their moods, together they work, train in their gym, worship, tend to their garden, cook and spend evenings playing the board game Carrom. They have come to inhabit the indeterminate situation that has devolved, and emotionally, socially and practically have made the best of existing in an ongoing state of standby.

Three men and an island on indeterminate standby

As we have detailed, Mohammed, Ahmed and Hassan are living in a partially ruined island resort, not a completely abandoned, derelict site. Their memories of this place in the recent past are continuously provoked by the spaces and objects that surround them. In some parts of the resort, they are able to maintain appearances and keep decay at bay. In other areas they accept the gradual distress wrought by non-human agencies, acknowledging that they can do little about those structures that are destroyed by overwhelming tides and storms; yet most of their maintenance work is consumed by responding to the effects produced by dynamic non-human agents, at an everyday level but also according to judgements that identify when material fabric has reached a point when it requires attention to avoid erasure. The material form of the resort continues to emerge through this prolonged period of indeterminate standby, and this also shapes the daily tasks the men perform. They too are on standby, waiting for an unknown future in which their prospects and that of the island resort in which they live is uncertain. The resort may be abandoned as have other Maldivian holiday sites at Avanti and Dolhiyadhoo, both seeking buyers at the time of research, and the long-abandoned Villingivaru resort which was repurposed as a quarantine facility during the recent COVID pandemic. Here, these ruinous resorts testify to the capacity of vibrant non-human energies to reconfigure the futures of abandoned sites in a tropical environment, producing spectacular human/non-human forms that will gradually disappear through botanical, physical and chemical agencies. Perhaps such settings prefigure a future in which unhindered non-human participants will transform places across the earth as climate and environmental change takes its toll on human presence.

Through this particular study, we have sought to expand understandings of standby, exploring its different temporalities, conditions and practices. Some accounts investigate the regular regimes enacted to resist any deterioration and prepare for the scheduled advent of workers or travellers, as with the planned infrastructural standby repetitively performed at Hamburg’s cruise ship terminals (Kühn, Citation2021). In other circumstances of standby, technical systems are devised to maintain high levels of reliability by imposing a constant anticipatory alertness to avoid catastrophic breakdowns. Examples include the prevention of digital data loss, procedures to deal with emergencies at nuclear power plants, and schemes to minimize power supply outages or curtail crises in aircraft control centres (Taylor, Citation2021). Likewise, the vigilant preparedness instantiated in emergency planning instals an anticipatory readiness to act when disasters occur (Deville, Citation2021). Other forms of standby include the basic maintenance of buildings as speculators wait for potential economic regeneration or funding. These modes mobilize strict maintenance procedures and rigorous oversight, whereas the smaller scale practices of upkeep performed by the workers on the island are more improvisational.

The indeterminate standby that we investigate here resonates more with the ‘standby urbanization’ detailed by Müller (Citation2021) in his study of how marginalized residents of Rio de Janeiro must accept a condition of ‘dwelling in limbo’. In this situation, organized crime has infiltrated official schemes and rendered ineffective both flood prevention measures to ameliorate property damage and the allotment of dwellings created in resettlement schemes intended to provide alternative accommodation. Residents must live in limbo, only basically maintaining their homes as they wait to be rehoused at an indeterminate future date, their destinies emerging under conditions of criminality, violence, inequality and corruption. The prolonged delays experienced by migrants in detention centres as they await decisions about whether they qualify for asylum or as refugees that will allow them to leave the camps similarly exemplifies a provisional standby without a definitive end (De Genova, Citation2021).

An extending of thinking about standby registers how each situation is shaped by a shifting array of contingencies, procedures and agencies, and so are the practices of maintenance that are undertaken. The indeterminate standby that prevails on the island resort is uniquely composed from a diverse range of political motivations, economic interests and conditions, spatial and material contexts, non-human agencies, and the practices and dispositions of those who work under conditions of unpredictability and fragility. Here, however, standby can only be performed if it is economically viable. It is possible because migrant labour costs are low, and workers can be easily controlled. The resort is on hold, and no one can predict when the legal dispute will be resolved, whether new investors might emerge or government policies may change. Adding to the uncertainty is advancing process of climate and environmental change – rising tides, rainstorms, winds – which make island life and infrastructure more precarious, as exemplified by the abandonment of other islands because of rising sea levels (Kothari et al., Citation2023; McMichael et al., Citation2021).

Yet, the affective and emotional qualities of the indeterminate standby on the resort island have changed. Whereas at the start of their work, the men envisaged a period that would come to an end after a few months, this has been extended over years with no end in sight. Their anxieties about the future are growing, and they continue to lack agency in determining their work or mobility. Despite the iniquitous position in which their lives are shaped by powerful economic interests that have command over their ‘availability and disposability’ (Kemmer et al., Citation2021, p. 2), Mohammed, Hassan and Ahmed have settled into a routine of maintenance work and everyday living. Accordingly, they are not simply passive victims of their circumstances.

Despite their inability to determine where they live and how they work, the men remain careful guardians of place, augmenting their work responsibilities with daily living, social pleasures and leisure practices. Their encounters with island space and with each other take place in an affective realm of incessant upkeep, growth and decay, daily maintenance and domestic and leisure practices, in an atmosphere of conviviality supplemented by the sensory overload of the heat, humidity, waves, wind and rain. The indeterminate standby in which they are situated has allowed them to become quiet custodians of an island whose traces of its resort past remain tied to this place and routinely trigger their memories. While conflict over the resort rages, they are slowly and carefully nurturing, inhabiting and holding the island resort in place so that it may once more thrum. Under these conditions, as Jackson (Citation2014) identifies, they undertake a far from instrumental approach to maintenance; their everyday, mundane, routine work is suffused with a deep sense of attachment to the island and its spaces, buildings and objects.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the three men on the island who shared with us their lives, experiences and aspirations. Thanks to our research assistant Anaa Mariyam Hassan who accompanied us to the island and provided much research support. We also appreciate the valuable insights and contributions from Moomina Mohamed and Susanne Schech.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, J. (2015). Understanding cultural geography: Places and traces (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Armstrong, J. (2020). In the presence of absence: Meditations on the cultural significance of abandoned places. In T. Edensor, A. Kalandides, & U. Kothari (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of place (pp. 518–528). Routledge.

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

- Bentz, A., & Carsignol, A. (2021). Maldives’ migrants the other side of paradise: Economic exploitation, human trafficking and human rights abuses. Fondation Pierre du Bois.

- Bocco, G. (2016). Remoteness and remote places: A geographic perspective. Geoforum, 77, 178–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.11.003

- Cairns, S., & Jacobs, J. (2014). Buildings must die: A perverse view of architecture. MIT Press.

- Crang, M., & Travlou, P. (2001). The city and topologies of memory. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 19(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1068/d201t

- Crewe, L. (2011). Life itemised: Lists, loss, unexpected significance, and the enduring geographies of discard. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1068/d16709

- De Genova, N. (2021). On standby… at the borders of ‘Europe’. Ephemera, 21(1), 283–300.

- Denis, J., Mongile, A., & Pontille, D. (2015). Maintenance and repair in science and technology studies. TECNOSCIENZA: Italian Journal of Science and Technology Studies, 6(2), 5–15.

- Denis, J., & Pontille, D. (2023). Before breakdown, after repair: The art of maintenance. In A. Mica, M. Pawlak, A. Horolets, & P. Kubicki (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Failure (pp. 209–222). Routledge.

- DeSilvey, C. (2006). Observed decay: Telling stories with mutable things. Journal of Material Culture, 11(3), 318–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506068808

- DeSilvey, C. (2017). Curated decay: Heritage beyond saving. University of Minnesota Press.

- DeSilvey, C., & Edensor, T. (2013). Reckoning with ruins’. Progress in Human Geography, 37(4), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512462271

- Deville, J. (2021). Waiting on standby: The relevance of disaster preparedness. Ephemera, 21(1), 95–135.

- Edensor, T. (2005a). The ghosts of industrial ruins: Ordering and disordering memory in excessive space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 23(6), 829–849. https://doi.org/10.1068/d58j

- Edensor, T. (2005b). Waste matter-the debris of industrial ruins and the disordering of the material world. Journal of Material Culture, 10(3), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183505057346

- Edensor, T. (2011). Entangled agencies, material networks and repair in a building assemblage: The mutable stone of St Ann’s Church, Manchester. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(2), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00421.x

- Edensor, T. (2016). Incipient ruination: Materiality, destructive agencies and repair. In M. Bille & T. Sorensen (Eds.), Elements of architecture (pp. 348–364). Routledge.

- Gillon, C., & Gibbs, L. (2019). Coastal homemaking: Navigating housing ideals, home realities, and more-than-human processes. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 37(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818811140

- Graham, S., & Thrift, N. (2007). Out of order: Understanding repair and maintenance. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407075954

- Ingold, T., & Hallam, E. (2007). Creativity and cultural improvisation: An introduction. In E. Hallam & T. Ingold (Eds.), Creativity and Cultural Improvisation (pp. 1–24). Routledge.

- International Organisation of Migration. (2019). Migration in Maldives: A country profile. IOM.

- Jackson, S. (2014). Rethinking repair. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality and society (pp. 221–239). MIT Press.

- Kemmer, L., Kühn, A., Otto, B., & Weber, V. (2021). Standby: Organizing modes of in-activity. Ephemera, 21(1), 1–20.

- Kothari, U., & Arnall, A. (2020). Shifting sands: The rhythms and temporalities of island sandscapes. Geoforum, 108, 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.03.006

- Kothari, U., Arnall, A., & Azfa, A. (2023). Disaster mobilities, temporalities and recovery: Experiences of the tsunami in the Maldives. Disasters, 47(4), 1069–1089. https://doi.org/10.1111/disa.12578

- Kühn, A. (2021). Infrastructurl standby: Caring for loose relations. ephemera, 21(3).

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street phenomenology: The go along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455–485.

- Lefebvre, H. (2004). Rhythmanalysis: Space, time and everyday life. Continuum.

- Massey, D. (1995). For space. Sage.

- McMichael, C., Kothari, U., McNamara, K., & Arnall, A. (2021). Spatial and temporal ways of knowing sea level rise: Bringing together multiple perspectives. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 12(3), e703. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.703

- Ministry of Tourism. (2019). Tourism yearbook 2019.

- Mohamed, M. (2021). Protecting migrant workers in Maldives. International Labour Organization.

- Müller, F. (2021). Standby urbanization: Dwelling and organized crime in Rio de Janeiro. Ephemera, 21(1), 137–172.

- Solnit, R. (2006). A field guide to getting lost. Canongate Books.

- Straughan, E., Bissell, D., & Gorman-Murray, A. (2020). The politics of stuckness: Waiting lives in mobile worlds. Environment & Planning C: Politics & Space, 38(4), 636–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419900189

- Strebel, I. (2011). The living building: Towards a geography of maintenance work. Social and Cultural Geography, 12(3), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.564732

- Tait, M., & While, A. (2009). Ontology and the conservation of built heritage. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 27(4), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11008

- Taylor, A. (2021). Standing by for data loss: Failure, preparedness and the cloud. Ephemera, 21(1), 59–93.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2020). Common country Analysis Maldives. UNDP.

- Winter, T. (2004). Cultural heritage and tourism in Angkor, Cambodia: Developing a theoretical dialogue. Historical Environment, 17(3), 3–8.