ABSTRACT

This paper explores the ontological politics and practices of handwashing using hot tap water during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden through attending to how handwashing was performed, what thoughts and emotions handwashing practices evoked, and reflections about why these thoughts and emotions emerged. In analyses based on written diaries, stories, digital photos, and videos from the private sphere of the home, we show how the concepts of humans, non-humans, childhood, economy, ethics, infrastructure, and nature – together with public health organizations’ promotions of handwashing recommendations – are enacted and woven into the fabric of hot tap water use. Hot tap water emerged as an ambiguous commodity, differently shaped depending on past experiences and how messages from authorities were received. The politics of the seemingly mundane activity of washing hands (especially prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) consists of connectivities and relationships between various phenomena in fluid space, and blurs the boundaries between local and global, past and present. Thrifty handwashing practices previously established in the private sphere were challenged during the COVID-19 pandemic, as popular versions of surgical scrubbing were promoted. These versions were sometimes challenged when the inclusion of hot water was questioned at home and in public debate.

Resumen

Este artículo explora la política y las prácticas ontológicas del lavado de manos con agua caliente durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Suecia, prestando atención a cómo se realizaba el lavado de manos, qué pensamientos y emociones evocaban las prácticas de lavado de manos y reflexiones sobre por qué surgieron estos pensamientos y emociones. En análisis basados en diarios escritos, historias, fotografías digitales y videos de la esfera privada del hogar, mostramos cómo los conceptos de humanos, no humanos, infancia, economía, ética, infraestructura y naturaleza, junto con las organizaciones de salud pública que promovían las recomendaciones de lavado de manos; se promulgan y se integran en el tejido del uso de agua caliente. El agua caliente desde el grifo surgió como un bien ambiguo, con formas diferentes según las experiencias pasadas y cómo se recibieron los mensajes de las autoridades. La política de la actividad aparentemente mundana de lavarse las manos (especialmente antes de la pandemia de COVID-19) consiste en conectividades y relaciones entre diversos fenómenos en un espacio fluido, y desdibuja los límites entre lo local y lo global, el pasado y el presente. Las prácticas ahorrativas de lavado de manos previamente establecidas en la esfera privada fueron cuestionadas durante la pandemia de COVID-19, cuando se promovieron versiones populares del lavado de manos quirúrgico. Estas versiones fueron cuestionadas en ocasiones cuando la inclusión del agua caliente fue cuestionada en el hogar y en el debate público.

Résumé

Cet article étudie la politique ontologique et les pratiques de lavage de mains à l’eau chaude du robinet pendant la pandémie de COVID-19 en Suède. Il examine les techniques de lavage de mains, puis les pensées et les émotions qui en ont résulté. Il considère ensuite pourquoi ces dernières apparaissent. À l’aide d’analyses reposant sur des journaux personnels, des histoires, des photographies numériques et des vidéos provenant de l’espace privé du domicile, il montre comment les concepts d’humain, de non-humain, d’enfance, d’économie, d’éthique, d’infrastructure et de nature, ainsi que les promotions de conseils pour se laver les mains issus des organizations de santé publique, ont été adoptés et incorporés dans la trame de l’usage de l’eau chaude du robinet. Celle-ci s’avère être une ressource ambiguë, prenant des formes différentes selon les expériences vécues et la perception des messages gouvernementaux. La politique de cette activité apparemment ordinaire, surtout avant la pandémie, consistait de connectivités et de liens entre des phénomènes divers dans l’espace fluide, et estompe les frontières entre les échelles locale et internationale, entre le passé et le présent. Les pratiques économiques de lavage de mains, établies antérieurement dans l’espace privé, ont été remises en question pendant la pandémie de COVID-19, avec la promotion de versions populaires de la désinfection chirurgicale. Celles-ci étaient parfois contestées quand l’inclusion de l’eau chaude était remise en cause à la maison ou dans le discours public.

Introduction

Washing hands is a core hygiene practice in a range of settings such as health promotion, disease prevention, food control, and in medical and care facilities (Didier et al., Citation2021; Prüss et al., Citation2002). Handwashing is part of the global call for general access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene also known as WASH (Bartram & Cairncross, Citation2010), which signals the interconnectedness between people, technology, practice, health, and the environment (Tilley et al., Citation2014). When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world in 2020, handwashing was globally highlighted as a measure to limit the spread of the coronavirus (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2021). Some countries made water more accessible through measures like ‘free water for all’, but vulnerable groups of people, especially in rural communities in the global south, small towns, and informal settings, still lacked sufficient access to WASH (Amankwaa & Ampratwum, Citation2020).

The Swedish strategy to combat the spread of the coronavirus stood out globally, with mostly voluntary measures, even though the country was hit hard with many COVID-19 related deaths during the first wave of the pandemic (Kavaliunas et al., Citation2020; Ludvigsson, Citation2023). The less-strict COVID-19 responses in Sweden also diverged from those of the neighbouring Nordic countries (Laage-Thomsen & Frandsen, Citation2022). The pandemic was managed by experts of the Public Health Agency (PHA), and not politicians, as had been the case in many other countries (Kavaliunas et al., Citation2020). Instead, the politics of COVID-19 in Sweden could be argued to take place mostly where voluntary measurements were expected to occur: at home, at work, and in public places. Handwashing with soap and warm water was included in the voluntary measures in Sweden, together with general physical distancing and mobility restrictions. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, washing hands in Sweden was an everyday activity more or less consciously integrated into habits learned early on in life. Personal hygiene practice centred around washing hands when one’s hands were visibly dirty or presumably dirty from germs invisible to the human eye (Klein, Citation2003). Some countries that had experienced SARS in 2003–2004 noticed a change in handwashing practice after the epidemic and following increased awareness of the positive effects of washing hands to prevent spread of virus (Wong & Tam, Citation2005). Washing hands as a measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19 was eventually relegated to the background when the global medical community instead focused on indoor air quality.

Water use in private domains has previously been studied by scholars in human geography and related fields. Some studies have specifically positioned the use of hot tap water as relational – involving humans, non-humans, the material, technologies, and ecologies (Browne, Citation2016; Shove, Citation2003; Sofoulis, Citation2005; Waitt & Nowroozipour, Citation2020; Waitt & Welland, Citation2019). Shove (Citation2003), through her seminal work on social practice theory, laid the foundation for a research field connecting household’s ‘sayings and doings’ (Schatzki, Citation2002, p. 87) with our material world, competencies, and knowledge. Shove also delivered a critique against the present neoliberal conditions influencing the abilities of households to change their practices towards alignment with more sustainable lifestyles. Sofoulis (Citation2005) added to this critique and showed how private users of fresh water are ‘[…] living with systems and technologies designed to deliver the sublime illusion of endless supply’ (Sofoulis, Citation2005, p. 460). Research on intimate spheres has led to interest in the ethics and politics associated with practices involving water (Browne, Citation2016; Martens, Citation2012b), water use as assemblages (Waitt & Welland, Citation2019), and water use as embodied matter (Waitt & Nowroozipour, Citation2020). Practices can also be explored through ontological politics (Law, Citation2000; Mol, Citation1999). This approach recognizes practices as constantly changing and phenomena as multiple, rather than as routines, habits, and recurring patterns (cf. Browne, Citation2016; Shove, Citation2003).

Our aim is to explore the ontological politics (Mol, Citation2002; Whatmore, Citation2013) of hot tap water in handwashing practices, and through this exploration, unfold the relationships between humans, non-humans, materials, technologies, ecologies, and other phenomena that might be enacted in these relations (Mol, Citation2002). Politics based on this approach are made in connectivities (cf. Gandy, Citation2004), couplings, and relationships, which must be iteratively performed through practices (Law, Citation1999; Mol, Citation2013). In our research, we asked participants to submit written personal diaries, stories, photos, and videos, and specifically asked participants to document their thoughts, emotions and reflections about why certain thoughts and emotions emerged during handwashing.

Washing hands as politics, practice, and resource use

The politics of washing hands and the provision of necessary infrastructure, together with knowledge about how and when to perform handwashing, can be detected in its many versions, looking over time and space. Disease and deaths can be avoided globally if sufficient policies are in place and funds available for investments in safe water supply, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) (Prüss et al., Citation2002). However, access to infrastructure is not enough; the adoption of practices for proper hand washing is also necessary (Mosler, Citation2012). When accurate handwashing practices have been introduced in a community, practices have proven to be sustainable over time (Cairncross & Shordt, Citation2004; Cairncross et al., Citation2005). Scholars in social sciences of medicine have shown that habits, motivations, and costs of soap are factors that influence handwashing practices (Aunger et al., Citation2010). Promotion of handwashing with emotional levers such as ‘clean hands feel good’ are more efficient than cognitive statements (Bartram & Cairncross, Citation2010), and key motivations for handwashing include disgust, nurturing, comfort, and affiliation (Curtis et al., Citation2009). The COVID-19 pandemic brought insufficient WASH services to the fore (Giné-Garriga et al., Citation2021), and a correlation between poor WASH services and fatalities in COVID-19 has been suggested (Amankwaa & Fischer, Citation2020).

The present article started with an interest in exploring the energy – water nexus of which hot tap water is an example (cf. Foden et al., Citation2019; Hussey & Pittock, Citation2012; Leck et al., Citation2015). In this vein, Strengers (Citation2011) compared how energy and water are materialized in an Australian setting and concluded that water was a scarce resource which both providers and consumers are responsible for managing. Energy, on the other hand, was perceived as ‘always available for a price’ (Strengers & Maller, Citation2012, p. 760). Consequently, the responsibility associated with energy as a resource lies with suppliers. In Sweden, the situation is slightly different, as water scarcity is seldom discussed in public debate, and the energy used for heating water differs, depending on housing lease agreements. In most rental and cooperative housing (the main forms of lease for apartments in Sweden) the energy used to heat tap water is derived from the district heating system and costs are included in the rent (in rental housing) or in a fee (in co-operative housing) and are not visible costs for tenants or members of a cooperative housing association (Hjerpe, Citation2005; Krantz, Citation2005). In consequence, hot water is likely to be perceived as managed by providers, while tenants and members of cooperative housing associations might not reflect on their resource use at all. Residents in owner-occupied detached houses in Sweden are usually part of a similar energy – water infrastructure for provision, billing and management, as in the case in many other affluent parts of the world. Energy and water services are delivered directly to these residents, and they are billed per household.

Handwashing and hot tap water, in the context of resource use and everyday life practices, have not been studied to any large extent (cf. Somner et al., Citation2008 on surgical scrubbing), compared to, for example, bathing, showering, laundering, and dishwashing (Carrico et al., Citation2013). These practices-as-resource-use in domestic spheres have been extensively researched from sociomaterial and sociotechnical approaches, which have advanced our thinking about people, energy and water service systems, and relationships of power (Allon & Sofoulis, Citation2006; Browne, Citation2015, Citation2016; Gandy, Citation2004, Gram-Hanssen & Georg, Citation2018; Jack, Citation2013, Kadibadiba et al., Citation2018; Kuijer, Citation2017; Martens, Citation2012b; Pink, Citation2004; Shove, Citation2003; Shove et al., Citation2012; Sofoulis, Citation2005). Previous research in this vein has shown how households’ sociomaterial practices related to resource use are shaped by existing material worlds, changes in technologies available to users (such as the digitalization of services), and users’ competencies, emotions, and shared social meanings. Sofoulis (Citation2005) and Allon and Sofoulis (Citation2006) showed how water systems are expressions of power dynamics, and how water fittings support certain water use habits and hinder others. From this body of literature, we learn that practices are dynamic, but changes are slow, due to the complexity of relationships between the social and material (Shove, Citation2003). Kadibadiba et al., (Citation2018) explored sudden changes in water provision and showed how practices involving water can be dropped, resurrected, and re-created, thus pointing in the direction that Mol (Citation2002) suggested, with practices constantly being negotiated. A phenomenon like handwashing is only held together by the instantaneous actions of people, using the resources available.

Research in anthropology (Douglas, Citation2002), environmental management (Kadibadiba, Citation2018), sociology (Martens, Citation2012a, Citation2012b), and geography (Gandy, Citation2004; Waitt & Nowroozipour, Citation2020; Waitt & Welland, Citation2019) have provided insights into dirt, cleanliness, and water in different societies. This research highlighted how cleanliness became part of culture and politics, and people were ‘othered’ for having different views on what constituted ‘clean’. Douglas (Citation2002) showed how societal crises could change acceptable practices, and how hygiene routines might become rituals, which had a downside if they were ignored or neglected; for example, feelings of shame, guilt, or illness (cf. Didier et al., Citation2021).

Ontological politics (Mol, Citation1999, Citation2002) foregrounds relationships between humans, non-humans, the material, and technology in daily life and focuses on what these relationships do for societies (Law & Mol, Citation1995; Mol, Citation1999, Citation2002). Mol (Citation2002) proposed that ‘[…] ontologies are brought into being, sustained, or allowed to wither away, in common, day-to-day sociomaterial practices’ (Mol, Citation2002, p. 6). Hence, ontologies are constantly being negotiated, and politics are the microcosms of the everyday where changes occur. Through studying practices, we can understand politics. In mundane and dynamic practices – continuously performed at home or at work, in private or public life – different phenomena and their relationships to each other are enacted. How these relationships are formed constitute our societies, which are always negotiated through practices. With this approach we study what is made present: humans, non-humans, materials, and technologies.

Researching handwashing from the lens of ontological politics can make certain elements of hot tap water use visible; in our case the elements under consideration are thoughts and emotions (cf. Mol, Citation2002). Human geographers have inaugurated affectual and emotional geographies to analyse and understand thoughts, emotions, and power (cf. Curti et al., Citation2011; Thrift, Citation2004; Tolia-Kelly, Citation2006). Curti et al. (Citation2011) suggested that affect, emotions, and politics are connected. In a similar vein, Thrift (Citation2004) draws attention to the ‘essentially patchy and material nature of what counts as thought’ (Thrift, Citation2004, p. 59). He argues that reflexivity includes a range of actors and is ‘not just a property of cognition’ (ibid.). This notion of thought includes also affect, which can enable or disable action, depending on which mood is generated. Adding to the intricacy of affect, thinking is constantly in motion, in action, and – together with other phenomena – creates fluid space (cf. Law & Mol, Citation2001). Mol and Law (Citation1994) described fluid space as ‘[…] variation without boundaries and transformation without continuity’ (p. 658). In fluid space, handwashing is performed over and over again, in similar but not identical ways.

Methods

Our research started with an interest in resource use at home and how people used hot tap water in their private sphere. The research team consisted of competencies from cultural heritage, human geography, and visual arts, and we adopted an explorative approach. In a pilot study in 2015–2016 we used focus group interviews (Browne, Citation2016; Waitt & Welland, Citation2019), home visits (Pink, Citation2004), individual interviews, and audio-visual art (Borgdoff, Citation2010) to learn about sociomaterial practices that included hot tap water. None of the participants in the pilot study mentioned handwashing (Glad et al., Citation2017). In 2020 we conducted a second pilot study asking five people to write a ‘hot tap water diary’ and take pictures or record short videos (cf. Martens, Citation2012a; Martens & Scott, Citation2017). These participants reported handwashing as the main domestic activity that included hot tap water in 2020. We found this intriguing and continued to explore handwashing through stories submitted to us during the autumn and winter of 2020–2021, when many of our societies were seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We posted requests for stories on social media platforms (for example Facebook) and asked (originally in Swedish): ‘What are your thoughts about hot tap water when you wash your hands? What emotions emerge?’; and ‘If you reflect on your thoughts and emotions during handwashing, why do you think and feel like that?’ With these questions, we wanted our respondents to reflect on their handwashing activities and explore the reasons for their thoughts and emotions rather than only describing how they performed handwashing practices. The questions were posted together with questions about age, costs for hot tap water, country of birth, employment, family situation, gender identity, type of lease, income, and level of education. We viewed this information as complements to the stories and as giving background to the stories, rather than considering them as fixed categories.

Informed consent was acquired, and it was possible to submit the web inquiry without answering all questions and giving background information. In total, 64 people submitted their answers. Most of our respondents identified themselves as women and only one fifth of the respondents identified themselves as men. Since the research team are all women, and we used our social networks to distribute the inquiry, this was an expected bias. The dominating age group of 45–54-year-old respondents (one fourth of all respondents) also reflected the age range of our team. All but two of the respondents were born in Sweden, which was unexpected, since all research team members’ personal networks consist of people with different countries of birth. However, the inquiry was only available in Swedish since the research project concerned the situation in Sweden. One fifth of the respondents lived in cooperative housing, two fifths of the respondents lived in an owner-occupied house, and two-fifths rented a flat. Most respondents lived with others, had a university degree, and their household had a yearly income that would, in the Swedish context, be defined as ‘high income’ (the limit for paying state tax on top of municipal taxes). Most respondents also paid separately for hot tap water, but for two fifths of the respondents, these expenses were included in their rent or in a fee paid to the cooperative housing association and were therefore not a cost visible to them. The stories, photos, and videos were thematically coded, discussed in our research group, and analysed in relation to sociomaterial relationships, as encouraged in ontological politics (Mol, Citation2002).

In this article, we also draw on archival material from YouTube, Twitter, and websites to situate the stories about handwashing. To provide a historical contextualization of handwashing in Sweden, we searched in the National Library of Sweden’s database Libris (all years). Our research words were in Swedish (number of sources): ‘handhygien’ (38), ‘personlig hygien’ (990), ‘handtvätt’ (12), and ‘tvätta händer* (95) (In English: “hand hygiene”, ’personal hygiene’, ’handwash*’, ’wash* hands’. We have excluded material targeting children from the paper, since we are focusing on adults. The ‘handhygien’ search results contained several results with broken links to PHA and Public service television websites. Some links to local and regional authorities worked and mostly repeated the general message from PHA. ‘Personlig hygien’ naturally yielded diverse results and to limit the results, we looked at academic literature (Björk, Citation2016; Björkman, Citation2012; Erikson, Citation1970; Klein, Citation2003; Nordic Museum, Citation2004; Wiell, Citation2018).

In the following sections of the paper, we will first present a brief history and contextualization of handwashing in Sweden. We will then present the sociomaterial relationships of hot tap water and handwashing and the emerging ontological politics based on the themes identified in the submitted stories, photos, and videos. These themes included: infrastructure and ambiguous feelings; experiences and upbringing; economy; and the theme ‘not an issue’ and ‘no reflections’, when hot tap water and handwashing were absent in the focus group discussions or not generating any thoughts or emotions in some of the stories. To conclude, we discuss how handwashing practices and hot tap water were enacted in Sweden during the global crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Handwashing in Swedish society

Stories about personal hygiene have been collected by the Nordic Museum since the late 19th century (Nordic museum, Citation2004). This material shows that handwashing was not common practice in either rural or urban Sweden (Erikson, Citation1970). Swedish figures of speech showed how unimportant handwashing was in everyday life: ‘a peasant’s fist should be so dirty so grains can grow in it’ [Swedish: en bondes näve skall vara så smutsig så om han lägger ett sädeskorn i den skall det gro] or ‘a little shit clears the stomach’ [Swedish: litet skit rensar magen] (Erikson, Citation1970, p. 10). Stories from the early 20th century told how the fear of God and death made them avoid ‘the sin of pride’ by not using water and soap for personal hygiene (Klein, Citation2003). However, there was also an element of shame if visible parts of the body were dirty when people met with clergymen. Sweden was Christianized in the mid-11th century, and Catholics dominated the country until the Evangelical Lutheran Church was established as the state church in the 16th century until the year 2000. According to Erikson (Citation1970), women were generally cleaner than men, since household work included hygienic routines: preparing meals, and washing clothes and dishes. Handwashing for school children was stricter than general hand hygiene, since the teacher could ask the pupils to present their hands for inspection.

The promotion of handwashing as part of domestic personal hygiene in Sweden could, based on written sources, be traced back to around 1900 (Wiell, Citation2018). At the time, medical practitioners were concerned by the rapid increase in population, subsequent poor housing conditions, and diseases like tuberculosis, both in towns and in rural areas. In the 20th century, standards of living generally increased as a result of conscious political decisions to create the Swedish welfare state (Björkman, Citation2012). Coming from a very low standard of living, access to fresh tap water and sewage systems was gradually becoming standard in Sweden. Prime minister Per Albin Hansson introduced the political concept of ‘the People’s Home’ [Swedish: Folkhemmet] in a political speech in 1928, which also served as a trope for the Swedish welfare state (Björk, Citation2016). The People’s Home had a broader societal approach, but also targeted the private sphere and the personal hygiene of citizens by planning for the provision of proper bathrooms and kitchens in Swedish housing (Björkman, Citation2012). This form of politics continued in the decades following the end of the second world war and was integrated into Swedish building codes.

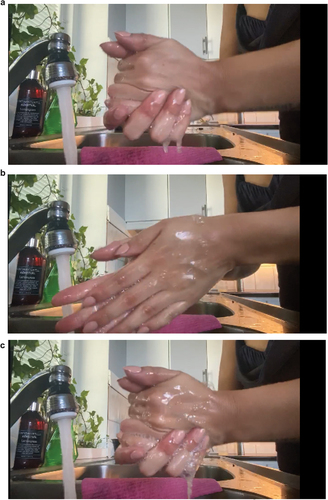

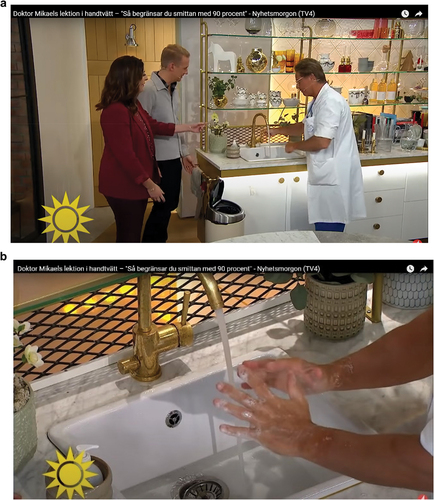

In recent times, a popular version of surgical scrubbing as the ‘right’ handwashing routine has been promoted by Sweden’s most popular morning news show [Swedish: Nyhetsmorgon] on the commercial channel TV4 (Nyhetsmorgon TV4, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018). The routine would, according to this TV show, protect you from diseases such as the ‘winter vomiting disease’ and annual influenzas. The demonstrated style for handwashing was a running tap, liquid soap, taking the time to really work up a foam and rubbing the soap around the palms, fingers, wrists, base of thumbs, and back of hands (see .). On one occasion, the running tap was questioned by the TV show host Soraya Lavasani (Nyhetsmorgon TV4, Citation2018):

You’ll get scolded for wasting water, I think.

Yes, a bit, but now we’re focusing on preventing diseases, you see.

Hahaha. (Nyhetsmorgon TV4, Citation2018)

Figure 1. News morning show TV4 invited medical doctor Mikael Sandström to demonstrate handwashing. Heading in Swedish reads in English: “Doctor Mikael’s lesson in handwashing: how to limit infection by 90% (news morning show TV4)” (Nyhetsmorgon TV4, Citation2018). ©2018 TV4.

The messages about handwashing from Swedish governmental agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic were very similar to the Swedish morning show prior to the pandemic but were delivered in a more impersonalized way with cartoon-like posters or video clips. PHA prescribed a handwashing routine and included some reasoning behind the prescription:

Wash your hands regularly—infectious agents are easily attracted to our hands. They can be passed on when you hold someone’s hand, for example. So, wash your hands regularly with soap and hot water, for at least 20 seconds. (PHA, Citation2021)

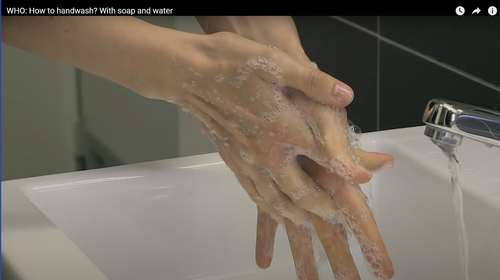

In contrast, the WHO (Citation2015) specifically advised that taps be left open during handwashing ‘[…] and let the water run smoothly to avoid touching the tap later on’ and stated that the handwashing procedure should take around one minute to perform (see ).

Figure 2. Prior to the covid-19 pandemic WHO posted videos to demonstrate handwashing under the headline: “how to handwash? With soap and water” (WHO, Citation2015). ©2015 WHO.

In Sweden, there was a contradictory message to the popular version of surgical scrubbing and spreading of the coronavirus sent through a Twitter account by the self-proclaimed ‘corona pedagogue’ and professor of clinical bacteriology Agnes Wold. The message was that excessive handwashing would only have limited effects on the spread of coronavirus. Eventually, Wold’s ability to communicate effectively – for example via the use of metaphors and by presenting complicated matters in simple language to the general public – led to her version being picked up by mass media such as newspapers, TV, and radio. Eventually a podcast ‘Ask Agnes Wold’ was launched, explicitly promoted with the ambition of being ‘health mythbusters’ (Swedish radio, Citation2021). One of the myths related to the coronavirus and COVID −19 was, according to Wold, handwashing as a disease-prevention measure.

In addition to questioning the use of handwashing as an important measure in COVID-19 prevention in private home settings, the inclusion of hot tap water was also disputed. Messages from authorities sometimes, but not always, included hot tap water. PHA and WHO recommended the inclusion of hot tap water ‘if possible’; a measure that was questioned both prior to the pandemic (Laestadius & Dimberg, Citation2005, Carrico et al., Citation2013), and during the pandemic (Swedish radio, Citation2022). Some scholars of medicine claimed that the use of heated water was not necessary to get hands clean (Laestadius & Dimberg, Citation2005, Carrico et al., Citation2013). Instead, scrubbing, the use of soap, and rinsing are the main elements in handwashing procedures that get rid of bacteria. The negative effects of using hot or warm water for handwashing includes skin irritation, and unnecessary use of heat with negative effects on the environment, and in the longer perspective, climate change (Carrico et al., Citation2013).

With other measures coming and going in 2020 and 2021 to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks, handwashing remained one of the few early and consistent measures, together with ‘keep your distance’ and ‘stay at home if you have symptoms’. Therefore, people in Sweden were generally, and in various places, exposed to messages about hand hygiene, and many had reasons to reflect about handwashing and hot tap water use in that context.

Being part of the infrastructure with ambiguous emotions

Some respondents who submitted stories to our research enacted global achievements and connectivities (cf. Gandy, Citation2004) when they washed their hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sigfrid, who is in his early 40’s, wrote:

[Handwashing evokes] thoughts about the time and effort it took for the infrastructure around hot water to be built and how fantastic people have worked with water in the world, so that we can have a better life. (Sigfrid)

The COVID-19 pandemic added yet another component to the already-intricate fabric of handwashing practices; handwashing became not only about concern for our own health, but also a collective responsibility to reduce the spread of the disease as members of the global population. The concerns and responsibilities involved in ethics and politics were incorporated into the stories shared by our respondents when they connected their handwashing with ambiguous thoughts and emotions about obligations, joyful feelings, and unease. Handwashing was rendered as multiple (cf. Mol, Citation2002) and hot water had, for many, enough force (cf. Whatmore, Citation2013) to find a way into their emotional life. In response to the question about thoughts and feelings when washing hands, Sixten, who in his late 40’s, wrote:

Today it is necessary and simultaneously comfortable […] I do it longer than previously. Warm feelings, it’s just right, but then comes the malaise and the pandemic … (Sixten)

Selma, is in her early 20’s, expressed the following:

Washing the hands in hot water is partly a feeling of luxury, partly anxiety. (Selma)

COVID-19 impacted mental health in Sweden, similar to the effects on people in China and Italy (McCracken et al., Citation2020). Soaking the hands in warm water can have a soothing effect on people but can, at the same time, evoke feelings of guilt for wasting a valuable resource such as hot water or act as a reminder to people about all the negative aspects of life during the COVID-19 pandemic or bring back unpleasant memories. Hot water had been loaded with messages from authorities; thus, water now had a different force and carried a different ontological politics than it had previously possessed. Sara, in her late 30’s, wrote:

I know that PHA says that you should wash your hands in warm water. I often think that they say that, but still always wash them in cold. I had bacilli fear as a child. Then the washing became manic, but the only thing that made me ‘free’. I often have to think about it so that I wash my hands fairly often. In these times, it’s easy to wash a little too much (or not?) (Sara)

This participant brought the Swedish authority PHA into the handwashing practice and also foregrounded childhood experiences of anxiety. Feelings of disgust and shame are common in relation to water and cleanliness (Douglas, Citation2002). During the pandemic, people in our study reported that they spent more time on handwashing and increased the frequency of this activity. New temporal and spatial connectivities with the hot water infrastructure became integrated into the everyday lives of ordinary people. Washing hands when re-entering the home after work or other activities away from home became a routine for many. The performance of handwashing included more visits to bathrooms and more time spent in bathrooms or other places where hot tap water could be accessed (cf. Martens & Scott, Citation2017). Kitchen sinks became a more consciously-enacted part of handwashing infrastructure, and other hot tap water practices, such as dishwashing, merged with handwashing (cf. Martens, Citation2012b, Martens, Citation2012a, Martens & Scott, Citation2017). Hence, handwashing spaces are fluid, not static, and is performed in certain localities at home (cf. Law & Mol, Citation2001, Mol & Law, Citation1994). One of our pilot respondents took a picture (see .) and wrote:

Soak the dishes. Does it count as the last hand wash of the day? Hot water, strong detergent, drier, and drier hands. (Siv, 34 years old)

Handwashing comes in multiple versions (cf. Mol, Citation2002), and foregrounding handwashing during the COVID-19 pandemic made our participants think about various ways of performing handwashing and the drawbacks they could entail (cf. Wong & Tam, Citation2005). The uncomfortable bodily experiences of the skin on one’s hands becoming drier from adopting handwashing routines promoted by Swedish and international authorities was common, especially in combination with Swedish winters, as indoor air was dry from central heating. Respondents’ thoughts and emotions were related to seasonal changes, and during the cold winter season when the outdoor temperature was low, some participants also experienced feeling cold indoors (from downdraughts, etc.). Warm tap water could, in winter, evoke feelings of being calm, relaxed, safe, and serve as a relief to cold fingers, hands, and even tense muscles in the rest of the body, built up from gradually becoming more and more immobile as the temperature decreased. Sofia, who is in her early 20’s, wrote:

Now during the winter, it feels like an almost luxurious feeling to be able to warm your hands in hot water. A feeling of calm. (Sofia)

Svea, who also is in her early 20’s, expressed:

[I] can sometimes let hot water run an extra moment on my hands as I am often cold, and my apartment has been poorly heated now during the winter—but also sometimes think that the heating is problematic! And that I should not use water for that. (Svea)

Handwashing was enacted as part of these participants’ thermal comfort practices, and hot water was an ingredient in these practices (cf. Mol, Citation2002). Through these practices, our participants formed relations between the systems for space heating and hot tap water. Both could be used to deliver bodily thermal comfort.

Experiences and up-bringing

Water can be a ‘socialising agent’ that is ‘[…] part of childhood training and amenable to later change and re-socialisation’ (Sofoulis, Citation2005, p. 448). Several of our respondents referred to and foregrounded their upbringing and memories from their childhood when we asked them to reflect about their thoughts and emotions during handwashing. Signe, who is in her late 30’s, wrote:

I realize that the feeling of safety comes from when I was little and had a habit of always having my hand under warm/lukewarm water when I brushed my teeth. Even though I was told by my parents not to do this (waste water), I did it out of sheer reflex. I realise that sometimes I still do this, but I turn the water off as I also get a bad conscience from wasting water. (Signe)

Handwashing was enacted through practices involving habits from childhood to create feelings of safety during the pandemic, which has taken many unpredictable turns over several years. The fluidity between and multiplicity of different, but connected, activities (brushing the teeth, warming the hand), and the emotions it evoked (reflexive enactment of a childhood habit, guilt for wasting water) could be an additional worry, on top of the anxiety many felt about the pandemic and the risk of becoming ill yourself or witnessing someone close to you become ill.

To handle anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, Professor Agnes Wold, with her ‘myth busting’ approach and factual pedagogics, brought relief to many Swedes (Swedish radio, Citation2021). Some respondents foregrounded statements by Wold and questioned the usefulness of choosing hot water over cold tap water. Stig, who is in his late 60’s, wrote:

[I] have bathed, and washed myself even in unheated water during my upbringing, but [I] prefer warm [water] and think it makes it more ‘clean’. If it really does … . (cf. Agnes Wold). (Stig)

The multiple versions (Mol, Citation2002) of clean are just as spatially- and temporally-bound as handwashing, and the practices performed are always historically located (Kuijer Citation2017; Law, Citation2004). When Wold is made present in the enactments of handwashing, it makes this participant uncertain about the relationship between ‘clean’ and the temperature of the water. Mixed messages from authorities are reflected in some of the stories, but most respondents seemed to have adopted the information promoted by the Swedish Public Health Agency.

Similarly, as in the research presented by Waitt and Nowroozipour (Citation2020) our participants foregrounded stories from their birthplaces and childhoods that were different from their present living conditions. Stories and references to poorer childhood conditions were often mentioned in the submissions, but so were expressions of joy at being more affluent as an adult. Sten, who is in his late 30’s, wrote:

I grew up in a country where the availability of water was not taken for granted. […] I will never forget my reaction the first day in Sweden when I washed my hands: there was such pressure in the tap that air bubbles formed on the hand! (Sten)

By making handwashing practices from the past visible and enacting handwashing in multiple versions (Mol, Citation2002) our respondents showed how previous experiences still matter. The memories of past experiences and practice memories from other countries affect current practices (Strengers & Maller, Citation2012). Various spaces for handwashing were also drawn into current practices, forming fluid spaces (Mol & Law, Citation1994). In their reflections, our participants gave many examples: growing up and visiting other countries; living in the countryside with one’s own freshwater well; spending time in the summer cottage with only ‘summer water’, which usually is water from a nearby lake that might be frozen in winter, and to prepare for winter it is necessary to empty the water pipes so they would not break when the water turns to ice and expands in the pipes. Experiences of parents teaching them as children, children teaching parents what they have learned in school, and experiences from mandatory military service were also present in the tales of hot tap water. Sensory experiences from the infrastructure at home were present: the noise from pipes, how the pipes felt, and the seasonal differences in water pressure (cf. Royston, Citation2014). In these stories, many different relationships were enacted and were important for their current handwashing practices. These relationships were a mix of the social, the material, the technical, and of nature.

Economy, individual metering, and billing

The appreciation of easy access to hot water in the tap was expressed in several stories. Some participants reflected on the relationship to expenses and mentioned cost in their interviews, even if their bills did not show costs for hot water. Previous studies have shown how thriftiness could be important in domestic resource use, especially for vulnerable groups in society; for example, for elderly persons in minority groups (Waitt et al., Citation2016). There is a unique situation in Sweden, where the costs for hot water and heating are obscured if included in the rent (if you’re a tenant) or fee (if you live in cooperative housing). This is evident in some of our participants’ stories, but again, is also ambiguous. Sören, a tenant who in his early 40’s, wrote the following:

It is natural for us who live in Sweden, but not for all countries. That hot water costs more to heat. Since I live in a rental apartment where water is included in the rent, I am not as frugal with the hot water as it is included in the rent; it would make a difference if I paid for it monthly. (Sören)

Current practices of making costs for hot water invisible in the relationships between energy providers, property owners, and residents influence how hot water is used. Consequently, some of the tenants and those living in cooperative housing had developed thrifty hot tap water practices and became ‘inadvertent environmentalist’ (Hitchings et al., Citation2015).

One of our pilot respondents, Sven, who is in his late 20’s had recently moved into a new home with individual metering of hot water. His pictures (see an example of his photos in .) and accompanied reflections stated:

Figure 4. Picture of bathroom sink with running water from the tap and the tap handle turned as far as possible in the direction of ‘only hot tap water’. (image by Sven).

9 am: I start washing my hands in cold water but turn to hot water because it feels too cold. But in the 20 seconds I wash my hands, no hot water emerges. I think it’s a bit poor for a newly built house that they cannot get the hot water faster. And since I pay individually for hot water, I wonder if those 20 seconds count as hot water use? In that case, it is not really worth washing your hands in hot water. (Sven)

The unclear model for debiting tenants in this rental flat made this respondent uncertain. The flow of the water might contain extra costs, but it is not certain. Cold tap water might include costs for hot water, even if the water feels cold. Despite feeling uncomfortable when using cold water when washing his hands, he considered washing his hands in cold water when he thinks about his future bills. Washing hands in cold water was, however, not a new experience for Sven, since the infrastructure for hot water in his parents’ house also resulted in a delay before hot water reached the tap. The sociomaterial relations in the home where you grew up could thus be (re)enacted as a practice memory (Strengers & Maller, Citation2012), even if the infrastructure of your new home is different.

In our previous research with focus groups on the topic of hot water, we noticed that tenants, in their conversations with each other, were inclined to not distinguish between hot and cold tap water (Glad et al., Citation2017). Tap water was treated as a unified substance. We interpreted the tenants’ lack of boundaries between hot and cold water as a consequence of hot water not being metered and billed separately. The costs were, and in many cases still are, veiled and made absent (cf. Law, Citation2004).

‘Not an issue’ and ‘no reflections’

Handwashing practices prior to the COVID-19 pandemic might have appeared to be too mundane an activity in Sweden to even mention in the context of hot tap water use. Handwashing was part of normality, and in fluid space, normality is a range that could be stretched without being perceived as abnormal (Mol & Law, Citation1994). Our focus group interviews from 2015–2016 did not include any discussions about handwashing, despite facilitators prompting the four different focus groups with a picture of a bathroom sink, a kitchen sink, and water faucets (Glad et al., Citation2017). Hot tap water was mentioned by the focus groups as bathing, showering, and dishwashing, but they also foregrounded heating water to cook meals and in laundering, and also tap water in general. No one mentioned handwashing; neither the participants, nor the research team. Our pilot study in the summer of 2020 also included respondents who stated ‘neutral’ with no thoughts or emotions during handwashing. Sonja recorded a short video (six seconds) with her performing handwashing at the kitchen sink, working up a foam when using liquid soap (see .) and wrote in her one-day diary:

1) Wash my hands: Neutral. […] 5) Wash my hands: Neutral. (Sonja)

Mol (Citation2002) proposed that in fluid space ‘[…] elements inform each other. But the way they do so continuously alters. The bonds within fluid spaces aren’t stable’ (p. 142). This creates viscosity in how handwashing might be performed and conceived. As we have shown in our brief history of handwashing in Sweden, research about this topic is scarce, but mass media picked up the public interest in preventing recurring diseases such as the ‘winter vomiting disease’, and with the COVID-19 pandemic, messages including handwashing instructions were visible on TV, social media, and at workplaces, schools, and shops, etc. With our collection of stories from the winter of 2020–2021, we were surprised to have a few respondents state that they experienced no thoughts, emotions, or reflections during handwashing. There is no obvious pattern as to who responded in that way: people with different backgrounds wrote ‘no thoughts’ in the stories they submitted to us. Thrift (Citation2004) suggested that emotions are difficult to discuss, and interviews as a data collection method might not be the best way to gather material on emotions. With our web-based inquiry asking for written stories, participants might be more able to think about and articulate their emotions, and we specifically asked for reflections on participants’ thoughts and emotions. Stefan, who is in his late 50’s, didn’t think of anything but still described how children spurred reactions and emotions:

Question: What are your thoughts about hot tap water when you wash your hands? What emotions emerge?

R62: Nothing special, but when my children rinse with lots of water, I usually tell them not to waste water. (Stefan)

Children’s hot tap water practices were made present as ‘wasteful’ and educating children not to waste heated water or any other source of energy became part of their upbringing. Relationships are also rooted in personal history, since this parent was taught the same thing during their own childhood. The past is made present through creating relationships between parent, child, and hot tap water.

Conclusions

During the first years of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sweden was internationally recognized for choosing a different path to combat the spread of the coronavirus compared to many other countries (Ludvigsson, Citation2023). Before vaccines became available, the Swedish government and the responsible governmental agency, the Public Health Agency of Sweden, relied mostly on voluntary measures and individual responsibilities, most prominently regular handwashing and physical distancing. These ‘soft measures’ rendered individuals at home and in society responsible for implementing COVID-19 politics (Kavaliunas et al., Citation2020). Our collection of stories from 2020–2021 showed how washing hands became a foregrounded activity when we explored the water – energy nexus and specifically hot tap water use, a result also found in Norway (Malmelund et al., Citation2021), Finland (Sedgwick et al., Citation2022), and during the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong (Wong & Tam, Citation2005). Handwashing, although multiple, is enacted through practices and can only be understood through its local sociomaterial complexities. Enacting handwashing as the core activity in COVID-19 politics also enacts the history and infrastructure of hot tap water in Sweden, as well as personal experiences, emotions, and practices.

When we examined hot tap water use in Sweden in 2015–2016, handwashing was made absent both by researchers and participants, as it was perhaps seen as too mundane an activity in Sweden to discuss at that time. When the coronavirus and COVID-19 became entangled in the hot tap water use in 2020–2021, handwashing came to the fore in multiple ways (cf. Mol, Citation2002). PHA prescribed a specific routine, including hot tap water and washing hands at least for 20 seconds, while the ‘corona pedagogue’ and professor of clinical bacteriology Agnes Wold questioned both handwashing and hot tap water use due to the potential risks of skin irritation, dermatitis, and bacterial growth on skin. PHA materialized hot tap water on posters and digital messages about handwashing, making hot tap water part of a heterogeneous network of a governmental agency, coronavirus, text, and handwashing (cf. Mol & Law, Citation1994). The materialities of water changed for our participants when handwashing was not only part of embodied practices from participants’ upbringing and previously-learned routines, but also text in messages from PHA. In their handwashing practices, our participants complied to the voluntary COVID-19 measures of regular handwashing and integrated the routines prescribed by PHA. Resource use and negative effects on the environment are prioritized areas of interest for Sweden in other contexts but are not present in the PHA version of hot tap water use. Several of our participants, however, included environmental considerations in their thoughts and feelings when using hot tap water, making the environment a personal matter.

Sweden could rightfully be described as a unique case as water, including hot tap water, is perceived as a free commodity by residents in rental housing and co-operatives. Over the longer perspective, this perception could be ‘bracketed’ in history. The ontological politics of hot tap water in Sweden are made by historical contingencies and practices. As an ingredient in the Swedish welfare society, the infrastructure for affordable hot tap water was included in modern housing for improving personal hygiene among the general public. Costs for hot tap water were made absent through practices of not billing hot tap water costs individually, but collectively (Hjerpe, Citation2005, Krantz, Citation2005). Our research participants still acknowledged the costs and cited hot tap water as a scarce resource through their previous experiences from other countries or upbringing and childhood in different housings and forms of tenure. In the PHA materialization of hot tap water in handwashing to prevent the spread of COVID-19, easy and affordable access to hot tap water was taken for granted.

The ontological politics of handwashing during the COVID-19 pandemic showed a compliance with the PHA and WHO handwashing instructions, rather than the popular version of clinical scrubbing suggested by the TV4 morning show a few years earlier (Nyhetsmorgon TV4, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2018). Still, handwashing came in many versions, as individualized practices, although most of the practices involved hot tap water, soap, and a duration in time (from 6 seconds to 20 seconds). Handwashing practices, as instructed by authorities, could be said to have kept some integrity, although they are performed by different individuals and in different parts of the world (cf. Mol & Law, Citation1994). Since memories and feelings are part of practices, and those who experienced the COVID-19 pandemic will remember for a long time how the coronavirus negatively affected many parts of our societies, handwashing practices will be associated with that era. Some people have integrated the prescribed handwashing routine in their personal hygiene practice, and some people find relief in not having to meticulously wash their hands regularly. Pandemics don’t respect administrative boundaries (Ludvigsson, Citation2023), and the notion of fluid space (Mol & Law, Citation1994) points in the direction of handwashing being subject to transformation but without continuity or boundaries. Fluid space acknowledges distant humans, non-humans, and materials as parts of practices, a potentially viable approach to other empirical fields within social and cultural geography.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to our research participants for making this research both possible and pleasant. We are grateful to our project advisory board: Fredrik Karlsson, Anna Malmberg, Mari-Louise Persson and Per Sjöström for their invaluable discussions, to visual artist Hasti Radpour for a fruitful collaboration, to the editor of this journal, and to the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and generous suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allon, F., & Sofoulis, Z. (2006). Everyday water: Cultures in transition. The Australian Geographer, 37(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180500511962

- Amankwaa, G., & Ampratwum, E. F. (2020). COVID-19 ‘free water’ initiatives in the global south: What does the Ghanaian case mean for equitable and sustainable water services? Water International, 45(7–8), 722–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2020.1845076

- Amankwaa, G., & Fischer, C. (2020). Exploring the correlation between COVID-19 fatalities and poor WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) services. medRxiv 2020.06.08.20125864.

- Aunger, R., Schmidt, W., Ranpura, A., Coombes, Y., Maina, P. M., Matiko, C. N., & Curtis, V. (2010). Three kinds of psychological determinants for hand-washing behaviour in Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 70(3), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.038

- Bartram, J., & Cairncross, S. (2010). Hygiene, sanitation, and water: Forgotten foundations of health. PLoS Medicine, 7(11), e1000367. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000367

- Björk, C. (2016). Den sociala differentieringens retorik och gestaltning: Kritiska perspektiv på funktionalistisk förorts- och bostadsplanering i Stockholm från 1900-talets mitt [The rhetoric and realisation of social differentiation: Critical perspectives on functionalistic suburban and housing planning in mid-20th century] [ Doctoral dissertation, Department of Culture and Aesthetics]. Stockholm University.

- Björkman, J. (2012). The right to a nice home: Housing inspection in 1930s Stockholm. Scandinavian Journal of History, 37(4), 461–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2012.703106

- Borgdoff, H. (2010). The production of knowledge in artistic research. In M. Biggs & H. Karlsson (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Research in the arts (pp. 74–93). Routledge.

- Browne, A. L. (2015). Insights from the everyday: Implications of reframing the governance of water supply and demand from ‘people’ to ‘practice’. WIREs Water, 2(4), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1084

- Browne, A. L. (2016). Can people talk together about their practices? Focus groups, humour and the sensitive dynamics of everyday life. Area, 48(2), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12250

- Cairncross, S., & Shordt, K. (2004). It does last! Some findings from a multi-country study of hygiene sustainability. Waterlines, 22(3), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.3362/0262-8104.2004.003

- Cairncross, S., Shordt, K., Zacharia, S., & Govindan, B. K. (2005). What causes sustainable changes in hygiene behaviour? A cross-sectional study from Kerala, India. Social Science & Medicine, 61(10), 2212–2220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.019

- Carrico, A. R., Spoden, M., Wallston, K. A., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2013). The environmental cost of misinformation: Why the recommendation to use elevated temperatures for handwashing is problematic. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 433–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12012

- Curti, G. H., Aitken, S. C., Bosco, F. J., & Goerisch, D. D. (2011). For not limiting emotional and affectual geographies: A collective critique of Steve Pile’s ‘emotions and affect in recent human geography’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(4), 590–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00451.x

- Curtis, V. A., Danquah, L. O., & Aunger, R. V. (2009). Planned, motivated and habitual hygiene behaviour: An eleven-country review. Health Education Research, 24(4), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyp002

- Didier, P., Nguyen-The, C., Martens, L., Foden, M., Dumitrascu, L., Mihalache, A. O., Nicolau, A. I., Skuland, S. E., Truninger, M., Junqueira, L., & Maitre, I. (2021). Washing hands and risk of cross-contamination during chicken preparation among domestic practitioners in five European countries. Food Control, 127, 108062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108062

- Douglas, M. (2002). Purity and danger: An analysis of concept of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

- Erikson, M. (1970). Personlig hygien. In C. Axel-Nilsson, N.E. Baehrendtz, S.O. Jansson & S.T. Nilsson. (Eds.), Fataburen: Nordic museum and Skansen Yearbook (pp. 9–22). Nordiska Museets förlag.

- Foden, M., Browne, A. L., Evans, D. M., Sharp, L., & Watson, M. (2019). The water–energy–food nexus at home: New opportunities for policy interventions in household sustainability. The Geographical Journal, 185(4), 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12257

- Gandy, M. (2004). Rethinking urban metabolism: Water, space and the modern city. City, 8(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360481042000313509

- Giné-Garriga, R., Delepiere, A., Ward, R., Alvarez-Sala, J., Alvarez-Murillo, I., Mariezcurrena, V., Göransson Sandberg, H., Saikia, P., Avello, P., Thakar, K., Ibrahim, E., Nouvellon, A., El Hattab, O., Hutton, G., & Jiménez, A. (2021). COVID-19 water, sanitation, and hygiene response: Review of measures and initiatives adopted by governments, regulators, utilities, and other stakeholders in 84 countries. Science of the Total Environment, 795, 148789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148789

- Glad, W., Axelsson, B., & Höijer, J. (2017). Hot (water) topics: The formation of an energy issue at home. In T. Laitinen Lindström, Y. Blume, & M. Regebro (Eds.), Eceee 2017 Summer study on energy efficiency: Consumption, efficiency and limits (pp. 2069–2074). Eceee Secretariat.

- Gram-Hanssen, K. & Georg, S. (2018). Energy performance gaps: Promises, people, practices. Building Research & Information, 46(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2017.1356127

- Hitchings, R., Collins, R., & Day, R. (2015). Inadvertent environmentalism and the action–value opportunity: Reflections from studies at both ends of the generational spectrum. Local Environment, 20(3), 369–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.852524

- Hjerpe, M. (2005). Sustainable development and urban water management: linking theory and practice of economic criteria [ Doctoral dissertation, Department of Thematic Studies]. Linköping University.

- Hussey, K., & Pittock, J. (2012). The energy-water nexus: Managing the links between energy and water for a sustainable future. Ecology and Society, 17(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04641-170131

- Jack, T. (2013). Nobody was dirty: Intervening in inconspicuous consumption of laundry routines. Journal of Consumer Culture, 13(3), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540513485272

- Kadibadiba, T., Roberts, L. & Duncan, R. (2018). Living in a city without water: A social practice theory analysis of resource disruption in Gaborone. Botswana,Global Environmental Change, 53, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.005

- Kavaliunas, A., Ocaya, P., Mumper, J., Lindfeldt, I., & Kyhlstedt, M. (2020). Swedish policy analysis for covid-19. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.009

- Klein, B. (2003). Nm 223 Personlig hygien. Nordiska museets förlag.

- Krantz, H. (2005). Matter that matters: a study of household routines in a process of changing water and sanitation arrangements [ Doctoral dissertation, Department of Thematic Studies]. Linköping University.

- Kuijer, L. (2017). Splashing: The iterative development of a novel type of personal washing. In D. Keyson, O. Guerra-Santin, & D. Lockton (Eds.), Living labs (pp. 63–74). Springer.

- Laage-Thomsen, J., & Frandsen, S. L. (2022). Pandemic preparedness systems and diverging COVID-19 responses within similar public health regimes: A comparative study of expert perceptions of pandemic response in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Globalization and Health, 18(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00799-4

- Laestadius, J. G., & Dimberg, L. (2005). Hot water for handwashing—where is the proof? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 47(4), 434–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000158737.06755.15

- Law, J. (1999). After ANT: Complexity, naming and topology. The Sociological Review, 47(1_suppl), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03479.x

- Law, J. (2000). Aircraft stories: Decentering the object in technoscience. Duke University Press.

- Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. Routledge.

- Law, J., & Mol, A. (1995). Notes on materiality and sociality. The Sociological Review, 43(2), 274–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1995.tb00604.x

- Law, J., & Mol, A. (2001). Situating technoscience: An inquiry into spatialities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 19(5), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1068/d243t

- Leck, H., Conway, D., Bradshaw, M., & Rees, J. (2015). Tracing the water-energy-food nexus: Description, theory and practice. Geography Compass, 9(8), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12222

- Ludvigsson, J. F. (2023). How Sweden approached the COVID-19 pandemic: Summary and commentary on the national commission inquiry. Acta Paediatrica, International Journal of Paediatrics, 112(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.16535

- Malmelund, S.-E., Dimka, J., & Bakkeli, D. Z. (2021). Social disparities in adopting non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19 in Norway. Journal of Developing Societies, 37(3), 302–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0169796X21996858

- Martens, L. (2012a). The politics and practices of looking: CCTV video and domestic kitchen practices. In S. Pink (Ed.), Advances in visual methodology (pp. 39–56.). Sage.

- Martens, L. (2012b). Practice ‘in talk’ and talk ‘as practice’: Dish washing and the reach of language. Sociological Research Online, 17(3), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2681

- Martens, L., & Scott, S. (2017). Understanding everyday kitchen life: Looking at performance, into performances and for practices. In M. Jonas, B. Littig, & A. Wroblewski (Eds.), Methodological reflections on practice-oriented theories (pp. 177–191). Springer.

- McCracken, L. M., Badinlou, F., Buhrman, M., & Brocki, K. C. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 in the Swedish population: Depression, anxiety, and insomnia and their associations to risk and vulnerability factors. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 63(1), e81. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.81

- Mol, A. (1999). Ontological politics. A word and Some questions. The Sociological Review, 47(1_suppl), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03483.x

- Mol, A. (2002). The body multiple: Ontology in medical practice. Duke University Press.

- Mol, A. (2013). Mind your plate! The ontonorms of Dutch dieting. Social Studies of Science, 43(3), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312712456948

- Mol, A., & Law, J. (1994). Regions, networks and fluids: Anaemia and social topology. Social Studies of Science, 24(4), 641–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631279402400402

- Mosler, H. J. (2012). A systematic approach to behavior change interventions for the water and sanitation sector in developing countries: A conceptual model, a review, and a guideline. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 22(5), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2011.650156

- Nordic museum. (2004) . Tio tvättar sig. Nordiska museets förlag.

- Nyhetsmorgon TV4. (2015, September 29) Tvätta händerna-skola [Wash hands school] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NiburgodoiY

- Nyhetsmorgon TV4. (2016, November 23) Så Tvättar du Händerna Rätt! [This is How You Wash Hands Properly] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u_aBrisqJTY&t=138s

- Nyhetsmorgon TV4. (2018, December 4) Doktor Mikaels lektion i handtvätt [Doctor Mikael’s lesson in handwashing] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1coUg5mXgg

- PHA. (2021, August 26). Public Health Agency of Sweden, How to Protect Yourself and Others from Being Infected by COVID-19. https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/communicable-disease-control/covid-19/protect-yourself-and-others-from-spread-of-infection/

- Pink, S. (2004). Home truths: Gender, domestic objects and everyday life. London: Berg.

- Prüss, A., Kay, D., Fewtrell, L., & Bartram, J. (2002). Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110(5), 537–542. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110537

- Royston, S. (2014). Dragon-breath and snow-melt: Know-how, experience and heat flows in the home. Energy Research & Social Science, 2, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.04.016

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Sedgwick, D., Hawdon, J., Räsänen, P., & Koivula, A. (2022). The role of collaboration in complying with COVID-19 health protective behaviors: A cross-national study. Administration & Society, 54(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211012418

- Shove, E. (2003). Comfort, cleanliness and convenience: The social Organization of normality. Berg: Oxford.

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. Sage.

- Sofoulis, Z. (2005). Big water, everyday water: A sociotechnical perspective. Continuum, 19(4), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310500322685

- Somner, J. E. A., Stone, N., Koukkoulli, A., Scott, K. M., Field, A. R., & Zygmunt, J. (2008). Surgical scrubbing: Can we clean up our carbon footprints by washing our hands? The Journal of Hospital Infection, 70(3), 212–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2008.06.004

- Strengers, Y. (2011). Beyond demand management: Co-managing energy and water practices with Australian households. Policy Studies, 32(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2010.526413

- Strengers, Y., & Maller, C. (2012). Materialising energy and water resources in everyday practices. Global Environmental Change, 22(3), 754–763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.04.004

- Swedish radio. (2021, February 16) Fråga Agnes Wold [Ask Agnes Wold] https://sverigesradio.se/poddar-program/teman/8066886

- Swedish radio. (2022, June 4) P4 Extra gästen–Agnes Wold om att hon alltid måste säga som det är [P4 Extra guest–Agnes Wold about always having to say how it is] https://sverigesradio.se/avsnitt/agnes-wold-om-att-hon-alltid-maste-saga-som-det-ar

- Thrift, N. (2004). Intensities of feeling: Towards a spatial politics of affect. Geografiska Annaler Series B, Human Geography, 86(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x

- Tilley, E., Strande, L., Lüthi, C., Mosler, H.-J., Udert, K. M., Gebauer, H., & Hering, J. G. (2014). Looking beyond technology: An integrated approach to water, sanitation and hygiene in low income countries. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(17), 9965–9970. https://doi.org/10.1021/es501645d

- Tolia-Kelly, D. P. (2006). Affect – an ethnocentric encounter? Exploring the ‘universalist’ imperative of emotional/affectual geographies. Area, 38, 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2006.00682.x

- Waitt, G., & Nowroozipour, F. (2020). Embodied geographies of domesticated water: Transcorporeality, translocality and moral terrains. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(9), 1268–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1550582

- Waitt, G., Roggeveen, K., Gordon, R., Butler, K., & Cooper, P. (2016). Tyrannies of thrift: Governmentality and older, low-income people’s energy efficiency narratives in the Illawarra, Australia. Energy Policy, 90, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2015.11.033

- Waitt, G., & Welland, L. (2019). Water, skin and touch: Migrant bathing assemblages. Social & Cultural Geography, 20(1), 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1347271

- Whatmore, S. (2013). Earthly powers and affective environments: An ontological politics of flood risk. Theory, Culture & Society, 30(7–8), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413480949

- WHO. (2015, October 20). WHO: How to handwash? With soap and water. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3PmVJQUCm4E

- Wiell, K. (2018). Bad mot lort och sjukdom: den privathygieniska utvecklingen i Sverige 1880–1949 [Public baths against dirt and disease: The personal hygiene development in Sweden 1880–1949] [ Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala studies in economic history]. Uppsala University.

- Wong, T. W., & Tam, W. W. (2005). Handwashing practice and the use of personal protective equipment among medical students after the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. American Journal of Infection Control, 33(10), 580–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2005.05.025