ABSTRACT

This paper combines the ‘local turn’ in the study of migration policy with the ‘practice turn’ in EU studies by analysing the humanitarian practices applied in the Sicilian city of Siracusa in the years 2013-2018. The primary interest of this research is to explore the practices by which the local community responded to the migration crisis in the Mediterranean and the contribution provided to migration governance by border cities such as Siracusa. It seeks to test the hypothesis that local communities are better apt to react to the emergency. While scholarly attention has focused extensively on the explanation of the multiple causes of migration as a global phenomenon, the practices adopted to manage migration still deserve investigation. Migration governance relies upon practices, i.e. competent performances, existing or emerging ‘on the ground’, to effectively address the phenomenon. By deconstructing the dynamics involving the European Union, decentring the study of migration governance in the Mediterranean allows us to go beyond the lack of EU policy-response to explore the local levels where politics takes place. Drawing on interviews with local actors, or international and national ones acting locally, the article explores the interaction among stakeholders in a practical context where actors, as members of a ‘community of practice’, are involved in a process of ‘learning by doing’. Empirical research demonstrates that the actors’ role in addressing the crisis, their ideas and know-how, have shaped migration governance and developed community practices in a process of ‘learning by doing’. It suggests further empirical research to test whether an emergency operational model – consisting of competent performances, routine practices and procedures to be adopted in other areas and cases, has emerged in this Sicilian border city.

Introduction

In the 2010s, increasing migration flows to Europe across the central Mediterranean revealed the inadequacy of the European Union (EU) and EU Member States’ (EUMS) institutions to face the so-called migration crisis.Footnote1 Some scholars argued that the ‘refugee crisis’ is a crisis of the EU (Bauböck Citation2018; Biermann et al. Citation2019; Börzel and Risse Citation2018; Caporaso Citation2018; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2018). Other authors considered the EU crisis and the refugee crisis as part of a bigger, global crisis (Bello Citation2017; Castles, de Haas, and Miller Citation2014; Cohen and Deng Citation1998; Gammeltoft-Hansen and Tan Citation2017). Undoubtedly, the shortcomings revealed in the operation of a common EU migration policy are not suggestive of a cohesive international European actor providing effective policy-response. By deconstructing the dynamics involving the EU, decentring the study of migration governance in the Mediterranean allows us to go beyond this stalemate at EU-level to explore the local levels where politics takes place.

The article investigates the features of Mediterranean migration governance by focusing on the crucial role of state and non-state actors addressing the migration crisis in the years 2013-2018. The practices here analysed are those emerged and applied on the ground in the Sicilian city of Siracusa, until a significant reduction of arrivals was registered in 2018. A peculiar synergy between state and non-state actors set up an efficient setting that profited from the stakeholders’ experience, producing practices that might be replicated in other disembarkation areas. This empirical research seeks to explore “the doings and sayings of those involved in world politics” (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2018, 2), namely what the stakeholders do and say in migration governance, to get closer to the actions of the practitioners involved in migration governance. The focus here is on the interaction among stakeholders in a practical context where actors, as members of a ‘community of practice’, are involved in a process of ‘learning by doing’.

The primary interest of this research is to explore the practices by which the local community responded to the migration crisis in the Mediterranean and the contribution provided by border cities such as Siracusa. Following an unclear logic in its multi-level division of tasks, EU policy-making is a “continuous negotiation among nested governments at several territorial tiers – supranational, national, regional and local” (Marks Citation1993, 392). Analysing the shift from institutional settings to the practices, ideas and know-how of actors ‘on the ground’ allows us to grasp the real venues of migration policy in the EU. EU migration policy consists of a panoply of actors operating at the EU borders, and their practices constitute the content of the EU’s external action.

To test the hypothesis that local communities are better apt to react to crises such as migration, this article combines the ‘local turn’ in the study of migration policy (Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata Barrero Citation2019) with the ‘practice turn’ in EU studies (Adler-Nissen Citation2016). It applies the practice approach (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011; Bueger and Gadinger Citation2018) to the local dimension of the multi-level migration governance model (Penninx et al. Citation2014) and demonstrates that, when addressing irregular migration,Footnote2 there is often a lack of coordination between the different levels. However, local cooperation can provide an effective response. Focusing on the Siracusa experience, it explores the ‘field of practice’ of migration, namely “a distinct practical configuration consisting of several practices which together achieve effects” (Bueger Citation2016, 410) to address the primary research question: why local communities are more efficient in migration governance? The answer suggested by the empirical research is that competent practices, either existing on the ground or produced by a learning by doing process, provide effective policy-response.

In Adler and Pouliot’s terms (Citation2011, 1), practices are ‘competent performances’ that “give meaning to international action, make possible strategic interaction, and are reproduced, changed, and reinforced by international action and interaction”. International practices are a particular kind of action, but they are different from both ‘behaviour’ and ‘action’, as the term ‘practice’ enables action and behaviour to hang together in ‘one coherent structure, by pointing out the patterned nature of deeds in socially organized contexts’ (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011, 5). The practice approach provides a useful explicative framework for discussing the practices developed by actors involved in migration governance in the Mediterranean. It allows the observer to better understand the development of ‘competent performances’, conceived of as bottom-up processes. In particular, it can be assessed to what extent actors and institutions involved in migration governance at the EU borders interact to develop and institutionalise new practices via a process of ‘learning by doing’.

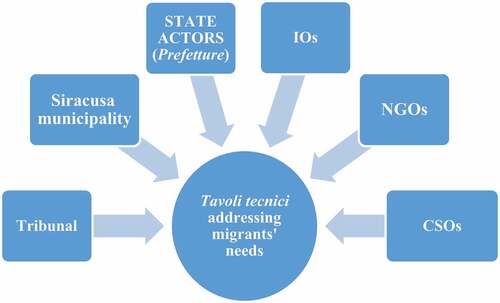

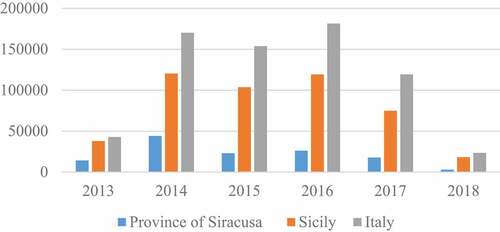

The phenomenon of crossing the Mediterranean by boat is not new. Until 2011, arrivals across the central Mediterranean remained fairly constant, to increase in scale since then. In 2014, irregular arrivals to Italy reached a peak, passing from 42,925 in 2013 to 170,100, with the Sicilian coasts being the main target (see ). This provoked the setting up of new migration procedures to respond to the emergency at the EU borders. State and non-state actors, European agencies, national and local authorities, all became engaged in the management of irregular migration. As the definition of governance as ‘self-organizing networks’ suggests, state and non-state actors operate together in complex networks to address societal issues (Rhodes Citation1996, 658). Similarly, to face the migration emergency, local authorities, local representatives of the national government and experts, set up procedures of first aid to address the disembarkation of migrants and provide them with initial reception facilities. Faced with emergency conditions, several International Organisations (IOs), Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) working in the hosting sector contributed to migration governance and shared their know-how in providing first aid and shelter to irregular migrants arriving in Italy, Sicily in particular. Close interdependence among actors, continuing interactions and exchange of resources, trust among participants and significant autonomy from the state (Rhodes Citation1996, 660) characterised the expert networks (in Italian they are called tavoli tecnici, literally ‘technical tables’) that were created to face the emergency, thus profiting from the expertise of relevant actors in the migration field, at local or international level. New and existing practices were applied on the ground to protect those in need, and priorities of irregular migration management were the duty to protect and the humanitarian dimension. This empirical research focuses on local, national and international actors that invest in ‘humanitarian practices’ by placing human beings at the centre of policy initiatives (Panebianco Citation2019, 387).

Table 1. Irregular entries through the Central Mediterranean (2013-2018)

While scholarly attention has focused extensively on the explanation of the multiple causes of migration as a global phenomenon (Attinà Citation2018; Bettini Citation2017; De Haas Citation2011; Geddes Citation2015; Van Hear, Bakewell, and Long Citation2018), or on personal reasons to leave (Carling and Schewel Citation2018; McMahon and Sigona Citation2018), various aspects of migration governance still deserve investigation, particularly institutional constraints/opportunities, the power of expertise and the role of ideas within operational local settings. By adopting an actor-centred approach, this research seeks to disentangle the complex interactions among actors addressing the Mediterranean migration crisis, thus providing empirical insights to “think about the contested concepts that lay at the core of the debate” (Bonjour, Ripoll Servent, and Thielemann Citation2018, quoted in the Introduction to this SI).

The article is organised as follows. The first part illustrates the research puzzle, which determined the choice of this case-study. The second explains the research design and methods used to conduct the empirical research. Part three develops the theoretical approach and applies the practice approach to the local level. Part four explores the policy practices typifying the Siracusa experience. Finally, the paper draws some conclusions on the replicability of the Siracusa operational model elsewhere.

Research Puzzle and Case-study Selection

The Siracusa experience in migration governance addresses the main assumption of this SI: a decentred approach improves our understanding of migration, and the local level provides useful insights.Footnote3 Siracusa is a case in point in migration governance in the Mediterranean, for several reasons. Geographically, Siracusa is a key Italian border city, located at the EU’s periphery on the south-Eastern coast of Sicily. Politically, it is on the front-line, since Augusta – a large industrial port of the province of Siracusa – was identified as a major disembarkation port at the time of the Italian Mare Nostrum operation (MNO), in 2013-2014.Footnote4 Socially, the city has developed a widespread hospitality approach that relies on voluntary associations, and has consolidated experience in the migrant reception sector.

Local actors have a long tradition of being proactive in migration governance, with a variety of stakeholders taking the lead and putting forward effective initiatives and strategies (Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata Barrero Citation2019). Moreover, cities are becoming prominent as spaces of cooperation and contestation in the context of national, European and international dynamics of reception and integration.Footnote5 Global migration cities such as New York, San Francisco, London, Barcelona and Milan, or smaller cities such as Rotterdam or Vienna have been extensively analysed and compared (Bazurli Citation2019; Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata Barrero Citation2019; Penninx et al. Citation2014). In contrast Siracusa, with its 122,000 inhabitants, stands out as an under-studied small-scale city, despite its remarkable experience in Mediterranean migration governance. Scholarly research on Southern Italy usually focuses on Lampedusa, rarely on Siracusa (McMahon Citation2019). However, Siracusa is particularly exposed to migrants’ arrivals across the Mediterranean. From 2013 to 2017 it was the Italian province with the highest number of arrivals. In 2014, the small province of Siracusa registered 44,116 arrivals, including daily arrivals due to favourable weather conditions (see ).

Siracusa has been selected as a case-study not only for its geographical position, but also because it experienced the emergence of humanitarian practices via the involvement of state and non-state actors, engaged in a context of cooperation where information and knowledge became valuable resources. This empirical research explains how the local level interacts with the national government on the one hand, and on the other with international actors engaged in migration management. In and around Siracusa, a form of migration governance characterised by solidarity and cooperation progressively emerged, often in a sudden, spontaneous fashion, providing relief alongside or outside the official political and administrative channels.

A practice approach is particularly useful to account for the process of migration governance and explain why local communities are more efficient in migration governance. In order to identify which factors favour or oppose the consolidation of practices, to assess the power of expertise and the role ideas play, the article seeks to answer the related research questions:

How do actors and institutions involved in migration governance at the EU borders interact to develop and institutionalise new practices?

Can we talk about a ‘community of practice’ within which information is shared and common understandings develop?

De facto, a decentring of practices – a ‘turn to the local’, was registered. Practices to face the migration crisis were elaborated on the ground, on a daily basis, to adapt to emerging needs, a process favoured by the attitudes and ideas pursued by key-stakeholders such as prefetti – who are charged by the central government with ensuring security at a local level (I17), prosecutors (I20), policemen (I18) and mayors (I4). At first, there was no clear-cut division of competence, but rather a fuzzy, fluid patchwork of activities. The Italian Red Cross (I12) and Emergency (I6) were acting in the same (health) sector, while legal information was provided by several associations (I1, I7, I9).

An operational model was created from scratch, involving all relevant stakeholders, including IOs, NGOs and local authorities in disembarkation activities. During the years 2013-2018, international actors such as Emergency (I6), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, I15), Médecins sans Frontiéres and Terres des Hommes moved to Siracusa and were welcomed by the local authorities for their expertise (I17); they joined existing or new expert networks set up to manage the disembarkation of migrants rescued by the Italian Coast Guard (I3) or by SAR NGOs. In order to fill the normative vacuum, which particularly regarded un-accompanied minors (UNMs), new procedures were set up (I17), new associations such as Accoglierete (I1) were created, and the new role of legal guardianship was established (I1, I9).

Empirical research explains what happened on the ground, how practices were elaborated and implemented by the actors involved in migration management in the Mediterranean. First-hand interviews were used to uncover the nature of the practices and their genesis via a process of ‘learning by doing’.

Research Design and Methods

The article relies upon original empirical research. The qualitative analysis combines document analysis – in particular the European Agenda for Migration (Citation2015), European Council Conclusions, the so-called Security Decrees adopted in Italy in 2018/2019, and reports of the selected organisations and associations, with semi-structured interviews conducted by the author.Footnote6

Fieldwork was carried out in Sicily in late 2019-early 2020. Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted primarily in Siracusa, mostly face to face. Interviewees were selected for their roles as key stakeholders in migration governance in Siracusa. Sample units were deliberately selected for the role they performed and the tasks they fulfilled in the management of the migration crisis, in order to guarantee a clear explanation and a deep understanding of migration governance. Selection was thus the result of deliberate choices.

Members of the sample were chosen to cover most of the relevant features of migration governance. Relevant stakeholders were easily identified. As in the case of qualitative sampling, selected units stand out for reasons of symbolic representation; in other words, they were chosen to represent and symbolise features of relevance to the investigation. The group of interviewees is largely representative, since it includes all relevant stakeholders: municipal authorities, Prefettura,Footnote7 Questura,Footnote8 Prosecutor’s Office, alongside IOs, NGOs and CSOs directly involved in the migration governance in Siracusa in the last decade, and particularly in the years 2013-2018. The collected data are not comprehensive, due to the difficulty of reaching actors such as staff working for Territorial Commissions at Prefetture or armed forces like Guardia di Finanza, but informal contacts combined with authorised interviews enabled to deeply explore the community of practice addressing migration.

The empirical research sheds light on the crucial role that local actors played in the years of the so-called emergency to address the increasing numbers of arrivals across the Mediterranean. The challenge of the research consists in the identification of relevant local actors in the fulfilment of migration governance, clarifying their proactive role in filling the vacuum left by state and EU actors. Interviews were conducted to explain the autonomy/coordination/dependence of local actors with relation to central government and the international level.

Due to their extensive experience in the field, almost all interviewees had been identified beforehand. In a few cases, interviewees were contacted as the result of a ‘snow-ball effect’, having been mentioned as relevant actors during other interviews. This is the case of small religious communities such as the Marist BrothersFootnote9 (I8) and the Scalabrinian NunsFootnote10 (I19), both supported by the Church (Arcidiocesi of Siracusa), and the municipality (I5). These two unexpected contacts did not affect the purposive sampling procedure, but rather reinforced it, since they exemplify the crucial role of churches and religious actors in providing housing and integration activities.

The Practice Approach Applied at the Local Level

Combining the ‘local turn’ in the study of migration policy (Caponio, Scholten, and Zapata Barrero Citation2019) with the ‘practice turn’ in EU studies (Adler-Nissen Citation2016) permits to explore the field of practice in migration governance. We take ‘governance’ as referring to the interaction of the different levels of government that are conducive to the management of a specific policy issue, which entails a sort of cooperative burden-sharing between actors (Rhodes Citation1996), including “the interdependence of public, private and voluntary sectors” (Stoker Citation1998, 16). Since migration is a highly politicised issue, a blurred interaction and cooperation context allowed for the multi-level governance (MLG) of migration, distributing tasks and responsibilities among levels of government.

The MLG approach originally elaborated by Gary Marks (Citation1993), bringing together actors operating at state, local and international levels, brings to the fore the local context. The contribution of cities in the migration field is crucial (Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2018; Penninx et al. Citation2014; Tortola Citation2017; Triandafyllidou Citation2014) since cities are on the forefront to react to crises. Broadly conceived, EU migration governance refers to all aspects of policy-response related to people on the move in and across the EU, and to the interconnection of several layers of policy. Regional migration governance includes “[r]egional institutions addressing mobility, asylum, migrant rights or migration control” (Lavenex Citation2018, 1275) and implies that complex interaction among various actors in the management of migration are made explicit in the MLG (Scholten and Penninx Citation2016). A focus on cities provides substance to the MLG in so far as they are close to where things happen.

However, an exclusive focus on distinct levels of government fails to grasp the complexity of migration governance. Migration is a complex phenomenon and can never be the responsibility of single authorities. MLG can plastically or figuratively portray the different levels of government, but cannot explain this mixture of levels, which is a peculiar feature of migration governance. Addressing the development of competent performances of the actors involved in migration governance, the practice approach provides a more sophisticated analysis. As illustrates, the Siracusa experience indicates that different levels of power are engaged in migration governance networks, but there is no linear top-down input, nor a clear distribution of tasks and roles, namely there can be dispersion of authority away from central governments, ‘upwards’ to the international level and ‘downwards’ to the subnational level (Hooghe and Marks Citation2001). Moreover, there is a very useful provision of information and knowledge is regarded as resource. The focus on competent practices in the border city of Siracusa adds another level of analysis and sheds light to migration governance in the EU periphery.

In the last two decades there has been a ‘practice turn’ (Adler-Nissen Citation2016), due to a growing scholarly interest in practices and flourishing literature adopting an actor-centred policy perspective (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011; Bigo Citation2002, Citation2011; Côté-Boucher, Infantino, and Salter Citation2014; Hopf Citation2018). On the one hand, there has been a sharp ‘local turn’ in policy-making with local governments of large cities becoming increasingly entrepreneurial (Scholten and Penninx Citation2016, 91). On the other, small cities faced with new challenges have also been compelled to react to a state of emergency, making a great effort to identify new practices and more efficient procedures that result from cooperation.

Siracusa shows that different layers are in a continuous state of fuzzy interaction. There is a bidirectional flow of information, and knowledge is understood as a precious resource. To address the sea arrivals across the Mediterranean in 2013-2018, cooperation within expert networks arose, producing dissemination of knowledge and an exchange of ideas, which led to effective practices. The practice approach helps us to understand policy-making because it explains where ideas reside. This empirical analysis of the Siracusa experience identifies knowledge and functioning mechanisms within expert networks or the individual contributions of experts giving rise to specific practices.

When governance fails, non-state actors can provide an effective contribution. Considering that IOs and NGOs possess specific know-how in the migration field, and CSOs have a privileged position due to their knowledge of the local community and territory, a continuous interaction among levels favours an exchange of information and knowledge, which are regarded as precious resources in migration governance. The increasing relevance of NGOs in global civil society is not an example of the transfer of power from state to non-state actors, but rather the expression of a changing logic of government, i.e. the essence of migration governance. This redefines civil society: from being a passive object of government that is acted upon, it is seen as an entity that is both an object and a subject of government (Sending and Neumann (2006) as quoted in Bueger and Gadinger (Citation2018, 125).

“The community of practice concept encompasses […] also the social space where structure and agency overlap and where knowledge, power, and community intersect. Communities of practice are intersubjective social structures that constitute the normative and epistemic ground for action, but they also are agents, made up of real people, who – working via network channels, across national borders, across organisational divides, and in the halls of government – affect political, economic, and social events” (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011, 18–19).

In his study on counter-piracy, Bueger (Citation2016) explored a community of practice, which was regarded as a platform of mutual engagement in the management of a crisis, serving to explore possible solutions for problems. He argued that counter-piracy actors agree on a common problem definition in legal, territorial and political terms (Bueger Citation2016, 408). In the same vein, the Siracusa experience unveils actual practices and shows that international and regional actors can develop strategies and institutions to address specific problems that have a transnational scale and global impact. When the migration crisis emerged – like counter-piracy, it was a field that was “relatively novel and characterized by high complexity”- roles and responsibilities were undefined and no routines were settled (Bueger Citation2016). In the migration crisis, roles, authority, and responsibilities had to be negotiated, providing space for the participation of international, national and local actors. These processes produced ‘governing practices’ (Bueger Citation2016, 409).

Domestic, regional and international dimensions are deeply intertwined in the Mediterranean, since the migration crisis has engaged several actors in providing first aid and shelters. Due to its geographical location in the centre of the Mediterranean, Italy finds itself at the forefront of the Mediterranean migration crisis. Most migration governance is conducted on Sicilian territory, but not necessarily by Italian state actors. In Siracusa, for instance, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) was involved in the hotspot system,Footnote11 the UNHCR has been acting with a permanent team since 2014, when the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), Save the Children and Terres des Hommes also arrived.

Bureaucrats, public officials, police and experts were all involved in issue networks set up to address the crisis; these ‘working tables’ (tavoli tecnici) are groups made of experts working alongside policy-makers, set up to respond to the emergency in a synergetic manner, produced what Prefetto Armando Gradone defines ‘a miracle, considering the great asymmetry between existing resources and needs’ (I17). Step-by-step, following a learning by doing process, they built an operational model from scratch to provide first aid, essential health services, food and shelters; what Gradone called the ‘Siracusa model’ (I17). A range of intermediaries acted as ‘service providers’ (Ambrosini Citation2018, 46), because the states’ restrictive immigration policies increased the role of NGOs and other non-public actors, such as religious institutions and CSOs, in bridging the gap between official policies and social reality.

The empirical findings provide tangible evidence of the contribution of non-governmental actors to the management of the migration crisis. Over the years, the various non-state actors involved in addressing the crisis have developed specific humanitarian practices (Panebianco Citation2019). Within migration governance, everyday humanitarian practices are pursued by a plurality of non-state actors involved in providing services and support to migrants. This has been the case of local actors located at the EU/Italian borders in Siracusa. The problem-solving capacity of the working tables that emerged in Siracusa around the migration governance is invaluable and conducive to the prompt elaboration of efficient modus operandi in the midst of the crisis.

The Empirical Findings: The Siracusa Experience in Developing Competent Practices

The theoretical argument of this article is tested through case-study research that seeks to assess where power resides in migration governance, how interests, ideas and calculations of relevant political actors shape decisions. Power is a major category in International Relations and is highly relevant in the practice approach, because it offers a “renewed understanding of what it means to govern, and how authority is distributed” (Bueger and Gadinger Citation2018, 6). The Siracusa experience in migration governance explains the configuration of power in local migration governance. Drawing on the concept of power elaborated by Adler-Nissen and Pouliot (Citation2014), we assume that power resides in resources such as competencies and know-how. The rise of non-state actors and transformations of authority in world politics have been explored in areas such as European diplomacy (Adler Nissen Citation2014). This article, however, is not about a nascent form of ‘migration diplomacy’ (Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019), but rather about explaining the processes through which various non-state actors have shared the responsibility of adopting authoritative decisions and exploring the factual management of the emergency within expert networks (here called tavoli tecnici).

The subjective evidence collected via interviews with relevant stakeholders, combined with objective official data, demonstrate that the continuous interaction between policy-makers and experts was favoured by the setting up of expert working groups aimed at finding operational procedures and effective solutions.

The sudden increase of arrivals to Europe across the central Mediterranean route had put Italy, and Sicily in particular, at the centre of the migration crisis. The lack of a coherent approach at EU level resulting from inter-institutional, intra-EUMS and domestic political crises (Menendez Citation2016; Slominski and Trauner Citation2018) induced Italy to adopt the MNO to face the emergency. Under pressure to deliver emergency responses, local authorities relied upon CSOs that were already active on the territory of Siracusa and had expertise in migration. Also, ‘new’ actors moved to Siracusa in 2013 when the Italian government identified the port of Augusta as the most suitable disembarkation place for the large military vessels conducting SAR operations. MNO had a direct impact on Siracusa: disembarkation taking place in Augusta caused nearly 45,000 arrivals in 2014 alone. In 2015, a mixed flow of 153,842 refugees, potential asylum seekers and economic migrants arrived in Italy: 103,693 arrived in Sicily, 22% arrived in Siracusa. The flows were almost constant from 2014 to 2016 ().

Figure 2. Sea Arrivals across the Mediterranean (2013-2018).

This significant movement of irregular migrants called for quick and effective responses that required the engagement of all the relevant actors, either international (UNHCR), national (the Italian Red Cross, Croce Rossa Italiana – CRI) or local (ARCI), in order to provide assistance to those in need. However, to provide food, shelter or health assistance requires know-how, connections and experience. The problem-solving approach of local authorities (especially Prefetto and Questore), combined with the idea that sharing expertise is an important added-value, in addition to humanitarian principles inspiring action and procedures on the ground, have produced a peculiar bottom-up methodology. Therefore, international actors such as IOM, UNHCR, EASO, Emergency, Medecins sans Frontières, Save the Children, Terres des Hommes, but also small religious communities such as the Scalambrinian Nuns, alongside nationwide NGOs like CRI, Caritas, Arci, contributed to first and second level reception and played a crucial role in the creation of effective procedures. A ‘Siracusa model’ (as Prefetto Gradone called it) of ‘governing through coordination’ (Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2018: 1998) emerged, based on a cooperative framework linking various urban actors, policy-makers, police, key civil society actors, alongside officials from UNHCR, IOM, CRI volunteers, priests and nuns, all ready to face the state of emergency. The Siracusa cooperation experience can be regarded as an almost spontaneous reaction to the emergency that brought local authorities and policy-makers together with NGOs, CSOs, volunteers, activists, etc., alongside IOs in a community of practice. They played a crucial role in delivering various social, humanitarian, political, and cultural services to incoming people.

The empirical findings indicate that migrant solidarity activism emerged as a response to the logic of emergency. The reaction to the migration crisis was quite controversial, slow and inconsistent, showing the structural weaknesses in the process of European integration. Respondents recall that there was an urgent need to act, quickly and effectively (I1, I10, I12, I14, I15, I18, I19, I20). Faced with the lack of EU intervention or concerted EUMS initiatives, local authorities (I17, I18) felt the pressure to deliver emergency responses and relied upon the expertise of local or international actors.

Empirical research provides support for the assumption that an organisational model peculiar to Siracusa has emerged. As explains, community practices emerged within tavoli tecnici set up around specific policy issues (UNMs, asylum, health protocols, housing). These expert networks are characterised by a blurred sharing of tasks; Prefettura, Questura or municipal administrations took into great consideration what IOs, NGOs, CSOs and voluntary associations had to offer to policy-makers in terms of expertise for identifying practices and implementing effective solutions (I1, I3, I6, I9, I12). Unsurprisingly, IOs, NGOs and CSOs possess specific expertise and can react more quickly to emergencies. The church and voluntary associations, too, are usually ready to contribute by investing in hosting and reception. Expertise in migration issues and deep knowledge of local realities and processes represent a unique source of expertise from which policy-makers profited (I4, I5, I17).

Although the central government has full responsibility for several aspects of migration governance, in the years of emergency local actors often acted in a normative vacuum – as in the case of UNMs. With the arrivals of high numbers of UNMs, the lack of procedures led to the elaboration of new practices (I1, I6, I9, I12, I15, I17). Siracusa experienced the adoption of practices elaborated spontaneously, while facing the emergency of the migration crisis through a process of ‘learning-by-doing’. shows that tavoli tecnici were set up as expert networks to manage the migration emergency and provide migrants with assistance and services. Comune di Siracusa and Prefettura arranged a series of formal and informal consultations to set up the required procedures to address the emergency. These consultations aimed at framing best practices and concrete policies on a local scale. The need to address the crisis more systematically explains why non-state actors such as IOs, NGOs and CSOs entered into full cooperation with local authorities.

A community of practice, for instance, emerged around the inter-force group GICIC that provided – between 2006 and 2018 – an innovative cooperation platform among prosecutors, Police, Coast Guard, Navy, Guardia di Finanza, Carabinieri and cultural mediators against smugglers that allowed for effective investigation strategies (I20).

The analysis of the Siracusa experience also allows us to identify specific practices such as the Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs) to be followed during disembarkation, which were elaborated locally and then adopted as procedures to be implemented in Messina, Salerno, Cagliari and Genova (I15). This is an example of best practices experienced in migration governance in the port of Augusta and replicated elsewhere, with the UNHCR favouring the institutionalisation of practices.

Experts, activists and volunteers engaged in cooperation with policy-makers usually aim at guaranteeing migrants’ rights. Ideological affinity provides a fertile ground for alliances with institutional actors and the promotion of expert networks (Bazurli Citation2019). While acknowledging some occasional serious friction, respondents described their relations with the political arena in a constructive manner, mostly depicting institutions as ‘allies’ rather than enemies to combat (I12, I15). Most respondents mentioned Prefetto Armando Gradone for being very open to dialogue with non-state actors (I1, I4, I9, I11); he ‘could have a tough vision on specific things’ (I12), but he was also ready to dialogue with CRI, UNHCR or IOM and profit from their expertise. Stakeholders’ ideas were revealed to be crucial; a problem-solving attitude of the local authorities (Prefetto and Questore in particular) has been widely acknowledged as being at the basis of this pragmatic framework of cooperation (I1, I9, I15).

Moreover, with their advocacy activity, several IOs, NGOs and CSOs tended to act as ‘migrants’ rights watchdog’ (e.g. IOM, UNHCR, CRI, CIR, ARCI, Borderline). Their critical stance allowed them to monitor the migrants’ conditions and conduct advocacy. Advocacy implies the promotion of migrants’ interests, and is inspired by humanitarian values; the organisations either engage in a frank and constructive, or a confrontational dialogue with local/national governments, sometimes creating advocacy coalitions (as in the case of ARCI and Accoglierete concerning UNMs). In other cases, a clear political stance can be expressed, as in the CIR case, with Director Morcone pleading for the revision of the Decreti Sicurezza (I13).

Some scholarly work has analysed the political party variable (Castelli Gattinara Citation2016). However, in the Siracusa experience, political party affiliation of local administrators has apparently not had a relevant impact on the pro- or anti-migrant attitude of the municipality (I1, I2, I9). Respondents do not consider the political affiliation of local elected representatives as a relevant explicative variable,Footnote12 but rather insist on the opportunity structure favoured by the Prefettura, first and foremost, as far as disembarkation was concerned. They also acknowledge concrete contributions such as the buildings made available for hospitality by the municipality, the support provided by the police concerning disembarkation procedures, and the role of the tribunal regarding the issue of UNMs. Respondents perceive the municipal political elite in Siracusa as sympathetic to migration issues. Apart from one critical respondent (I7), most respondents regard the local political élite as an ‘ally’, an approachable and cooperative counterpart (I6, I8, I11, I12, I19). Volunteers with great experience in the field are currently numbered among the Assessori (I5). A Mayor who offered the address of the Town Hall for the identity cards of migrants without a permanent address is acknowledged to be facilitating pro-migrant norms in terms of their regularisation (I1, I9). Moreover, the political context created by the Mayor Francesco Italia, since his election in 2018, has favoured the consolidation of existing cooperation networks among Accoglierete, ARCI, CIAO, CIR, OXFAM, or Impact Hub, thus furthering the institutionalisation of practices (I1, I2, I8, I9).

Conclusion: The Potential of the Siracusa Operational Model

Since the early 2010s, migration flows across the Mediterranean have become more visible, with millions of irregular migrants reaching Europe across the Mediterranean Sea. South European ‘frontline’ countries such as Italy, and border cities like Siracusa, have been more exposed to the increased arrivals and the political, humanitarian and societal crisis that followed. The main assumption at the basis of this research is that, in 2013-2018, migration governance required the elaboration of strategies and initiatives ‘on the ground’ to effectively address the phenomenon of the increasing number of arrivals across the Mediterranean. The Siracusa experience proves that local administrations and peripheral organisms of the state relied upon the help and support of IOs, NGOs and CSOs, that promptly participated in tavoli tecnici to face the emergency or contributed to the management of the crisis with their expertise. Irregular migration entered the political agenda as a relatively novel field characterised by great complexity. Communities of practice and expert networks based upon actual doing, sharing ideas and know-how, proliferated in Siracusa. Non-state actors and volunteer associations were numerous, favoured by local actors which profited from their expertise in the first aid and hospitality sectors, and regarded interaction and cooperation, sharing ideas and know-how in a multi-cultural setting as an added-value. NGOs, CSOs, regions, religious groups and local authorities provided hospitality and refuge to those in need, taking on some of the roles traditionally performed by national governments .

The article explored the Siracusa cooperation experience that was shaped by various actors, IOs, NGOs, CSOs and voluntary associations, with the support of local authorities. This operational model was not the result of a planned decentralisation process, but rather a spontaneous phenomenon that emerged thanks to farsighted local administrators, with the support of experts and volunteers who filled the gaps left by the EU and the central government. They were, de facto, engaged by municipal actors, local administrations and Prefettura (the territorial office of the state-government), convinced of the added-value of sharing expertise via cooperation in expert networks. To provide emergency responses, non-state actors played a crucial role in global and regional governance. The empirical research investigated the relation between the actors involved, both in cases where new alliances relying upon power-sharing were set up, or in those where a hands-off attitude of local institutions gave rise to competing behaviour among the actors concerned. Empirical research shows that in the Siracusa experience there was initially a sort of ‘delegation’ of functions to experts, which successively gave way to cooperation and mutual support. Practices were initially elaborated around tavoli tecnici that brought together the relevant stakeholders, i.e. institutions, policy-makers and experts, who cooperated in the search for practical solutions. Farsighted stakeholders convinced of the added-value of the problem-solving cooperation attitude favoured practices which took for granted the value of knowledge and information sharing. As a Mediterranean city located at the EU borders, Siracusa has tested an operational model based upon expertise and know-how.

Migration governance challenges state power (in Italy, in the Mediterranean, in Europe or elsewhere) and suggests that there are gaps in traditional state policies that can be filled by the direct involvement of local, transnational and private actors outside the state apparatus. Italy is situated at the EU’s southern maritime borders and experiences the EU’s permeability to global flows, even more than via land borders, where European rulers are intrigued by the construction of physical borders.

All in all, a practice approach implies that power involves a constant negotiation of what counts as competent and informed Adler-Nissen and Pouliot Citation2014. This article explains how practices, conceived as competent performances, have been adopted to face the migration crisis, particularly how ideas, competences and know-how have contributed to address the emergency. Tavoli tecnici are transnational migration networks that resemble epistemic communities. Communities of practice provide a fuller understanding of the phenomenon and explain that expert knowledge on migration is part and parcel of migration governance. It is not just about relations among people working together to manage migration, but rather about sharing views, ideas, behaviours, knowledge and expertise, because communities of practice are “containers of practice characterized by mutual engagement, joint enterprises, and a shared repertoire” (Brueger and Gadinger Citation2018, 54).

The main focus of this article was the adoption, evolution and institutionalisation of practices in migration governance at the local level following a ‘learning by doing’ process. Future research may explore confrontational interaction among the different levels of governance more deeply. Migration is a global phenomenon, not a contingent one. Bearing in mind the fact that migration flows from the Global South to the Global North are not destined to stop, but can select different entry points, the practices elaborated in the Sicilian border city of Siracusa can have application elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to the interviewees for having shared precious information and their experience via deep interviews. Special thanks go to the SI editors and to the anonymous referees for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript. Responsibility for the opinions expressed in the article remains with the author only.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. When talking about ‘migration crisis’, policy officials often imply large flows of uncontrolled migration to Europe. While acknowledging the increasing migration flows affecting Sicily in the 2010s, this article refers to ‘crisis’ first and foremost as the lack of institutional coordination and political response at the EU and national level conducive of a state of emergency. There was ‘an emergency’ not just in figures, but rather in the lack of policy-response that provoked “a wave of civil-society actions and initiatives of solidarity” (Castelli Gattinara Citation2017, 322).

2. The concept ‘irregular migration’ refers here to irregular access to Europe. We acknowledge that there are ‘refugees and other migrants,’ due to the mixed nature of the flows across the Mediterranean, and there is a continuous movement of people between categories across time and space (Crawley and Skleparis Citation2018). Being aware that refugees are also migrants and there is a tendency to privilege the former over the latter (Carling and Collins Citation2018), this article adopts an inclusive category of ‘irregular migrants’, without distinguishing between ‘refugees’ – who are entitled to international protection and asylum, and ‘migrants’ – mostly economic migrants, undeserving of protection in EU normative terms. An inclusive concept renders justice to forced displacements caused by multiple reasons.

3. On the contribution of the local level in moving the decentring agenda forward see Wolff and Kutz in this SI.

4. Since the adoption of MNO, in 2013, almost everyone who entered Italy after rescue by Search and Rescue (SAR) operations after an irregular journey across the Mediterranean, was disembarked in secured spaces at Italian ports, before being transferred into reception facilities. The identification procedure was initially rather fuzzy because the Italian authorities were not able to suddenly face such a high number of arrivals. To support frontline EUMS, in 2015, the European Commission set up the ‘hotspot system’ (see note 11).

5. Siracusa has recently expressed critical positions, challenging the national government. In January 2019, the Italian government used strong arm tactics against the SAR NGO SeaWatch, and for several days refused to assign a port of safety to let the SeaWatch 3: vessel disembark its rescued migrants. The Italian government was pursuing the ‘closed ports’ strategy defended by Matteo Salvini – Minister of the Interior in the years 2018-2019. However, Siracusa, in the shape of its Mayor (I4) and several associations (I1, I9, I16), decoupled from national migration policies and expressed itself in favour of the disembarkation of the on-board migrants.

6. A list of interviews is provided in Annex 1. To protect anonymity, interviewees are cited by institutional name or assigned code as in the Annex.

7. In Italy, Prefetture are the peripheral organs of the Ministry of the Interior representing the central government in the local territories. They play a crucial administrative role in the public security sector, in the migration field, concerning civil protection and more generally in the management of the relations with local actors.

8. Questura is the local office of the department of public security of the Ministry of the Interior. Questori make use of the police forces to guarantee public security and order.

9. Recently established in Siracusa, they founded an Intercultural Centre for Aid and Orientation (CIAO). Actively engaged in the integration of migrants, they provide first aid and education aimed at professionalization (courses of Italian primarily, but also English language, computer lessons, driving license and cooking).

10. They are investing in migrants’ professionalization via training for elderly care.

11. To support frontline EUMS – primarily Greece and Italy – to swiftly identify, register and fingerprint migrants, the European Agenda for migration established a ‘hotspot’ approach (European Commission Citation2015). EASO, Frontex and Europol work on the ground to ensure the swift identification, registration and fingerprinting of migrants in hotspots.

12. Some scholars have explored the meaning and implications of the rhetorical political claim ‘cities of welcome’ (Bazurli Citation2019). At the peak of the irregular migration crisis, Siracusa was governed by Giancarlo Garozzo – city mayor from 2013 to 2018 – of a left-leaning party (Partito Democratico). Since 2018 the mayor is Francesco Italia, Garozzo’s deputy Mayor. It has to be acknowledged that – during his electoral campaign, Italia defined Siracusa as a ‘city of peace and human rights’. However, this article focuses on the content and implication of practices, not on the pro-migrant narratives.

References

- Adamson, F. B., and G. Tsourapas. 2019. Migration diplomacy in world politics. International Studies Perspectives 20 (2):113–28. doi:10.1093/isp/eky015.

- Adler, E., and V. Pouliot. 2011. International practices. International Theory 3 (1):1–36. doi:10.1017/S175297191000031X.

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2014. Symbolic power in European diplomacy: The struggle between national foreign service and the EU’s External Action Service. Review of International Studies 40 (4):657–81. doi:10.1017/S0260210513000326.

- Adler-Nissen, R. 2016. Towards a practice turn in EU Studies: The everyday of European integration. Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (1):87–103. doi:10.1111/jcms.12329.

- Adler-Nissen, R., and V. Pouliot. 2014. Power in practice: Negotiating the international intervention in Libya. European Journal of International Relations 20 (4):889–911. doi:10.1177/1354066113512702.

- Ambrosini, M. 2018. Irregular immigration in Southern Europe. Actors, dynamics and governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave/MacMillan.

- Attinà, F. 2018. Tackling the migrant wave: EU as a source and a manager of crisis. Revista Española de Derecho Internacional 70 (2):49–70. doi:10.17103/redi.70.2.2018.1.02.

- Bauböck, R. 2018. Refugee protection and burden-sharing in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1):141–56. doi:10.1111/jcms.12638.

- Bazurli, R. 2019. Local governments and social movements in the ‘Refugee Crisis’: Milan and Barcelona as ‘Cities of Welcome’. South European Society and Politics 24 (3):343–70. doi:10.1080/13608746.2019.1637598.

- Bello, V. 2017. International migration and international security. Why prejudice is a global security threat. London/New York: Routledge.

- Bettini, G. 2017. Where Next? Climate change, migration, and the (bio)politics of adaptation. Global Policy 8 (Supplement 1):33–39. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12404.

- Biermann, F., N. Guérin, S. Jagdhuber, B. Rittberger, and M. Weiss. 2019. Political (non)reform in the Euro crisis and the refugee crisis: A liberal intergovernmentalist explanation. Journal of European Public Policy 26 (2):246–66. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1408670.

- Bigo, D. 2002. Security and immigration: Toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives 27 (1):63–92. doi:10.1177/03043754020270S105.

- Bigo, D. 2011. Pierre Bourdieu and International Relations: Power of practices, practices of power. International Political Sociology 5 (3):225–58. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00132.x.

- Bonjour, S., A. Ripoll Servent, and E. Thielemann. 2018. Beyond venue shopping and liberal constraint: A new research agenda for EU migration policies and politics. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (3): 409–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016

- Börzel, T. A., and T. Risse. 2018. From the Euro to the Schengen crises: European integration theories, politicization, and identity politics. Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1):83–108. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310281.

- Bueger, C. 2016. Doing Europe: Agency and the European Union in the field of counter-piracy practice. European Security 25 (4):407–22. doi:10.1080/09662839.2016.1236020.

- Bueger, C., and F. Gadinger. 2018. International practice theory. 2nd ed. Cham: Palgrave/MacMillan.

- Caponio, T., and M. Jones-Correa. 2018. Theorising migration policy in multilevel states: The multilevel governance perspective. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (12):1995–2010. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341705.

- Caponio, T., P. Scholten, and R. Zapata Barrero, eds. 2019. The Routledge handbook of the governance of migration and diversity in cities. New York: Routledge.

- Caporaso, J. A. 2018. Europe’s triple crisis and the uneven role of institutions: The Euro, refugees and Brexit. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (6):1345–61. doi:10.1111/jcms.12746.

- Carling, J., and F. Collins. 2018. Aspiration, desire and drivers of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6):909–26. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134.

- Carling, J., and K. Schewel. 2018. Revisiting aspiration and ability in international migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6):945–63. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384146.

- Castelli Gattinara, P. 2016. The politics of migration in Italy. Perspectives on local debates and party competition. New York: Routledge.

- Castelli Gattinara, P. 2017. The ‘refugee crisis’ in Italy as a crisis of legitimacy. Contemporary Italian Politics 9 (3):318–31. doi:10.1080/23248823.2017.1388639.

- Castles, S., H. de Haas, and M. J. Miller. 2014. The Age of Migration: International population movements in the modern world. Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave/MacMillan.

- Cohen, R., and F. M. Deng. 1998. Masses in flight: The global crisis of internal displacement. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Côté-Boucher, K., F. Infantino, and M. B. Salter. 2014. Border security as practice: An agenda for research. Security Dialogue 45 (3):195–208. doi:10.1177/0967010614533243.

- Crawley, H., and D. Skleparis. 2018. Refugees, migrants, neither, both: Categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding, in Europe’s ‘migration crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1):48–64. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1348224.

- De Haas, H. 2011. Mediterranean migration futures: Patterns, drivers and scenarios. Global Environmental Change 21 (Supplement 1):59–69. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.003.

- European Commission. 2015. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A European Agenda on Migration, Brussels, 13.5.2015 COM(2015) 240 final.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., and N. F. Tan. 2017. The end of the deterrence paradigm? Future directions for global refugee policy. Journal on Migration and Human Security 5 (1):28–56. doi:10.1177/233150241700500103.

- Geddes, A. 2015. Governing migration from a distance: Interactions between climate, migration, and security in the South Mediterranean. European Security 24 (3):473–90. doi:10.1080/09662839.2015.1028191.

- Genschel, P., and M. Jachtenfuchs. 2018. From market integration to core state powers: The Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis and integration theory. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1):178–96. doi:10.1111/jcms.12654.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2001. Multi-level governance and european integration. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hopf, T. 2018. Change in international practices. European Journal of International Relations 24 (3):687–711. doi:10.1177/1354066117718041.

- Lavenex, S. 2018. Regional migration governance – building block of global initiatives?. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (8):1275–93. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1441606.

- Marks, G. 1993. Structural policy and multilevel governance in the EC. In The state of the european community. The maastricht debates and beyond, ed. A. Cafruny and G. Rosenthal., Vol. 2, 391–410. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- McMahon, S. 2019. Making and unmaking migrant irregularity. In The Routledge Handbook of the Governance of Migration and Diversity in Cities, ed. T. Caponio, P. Scholten, and R. Zapata Barrero, 364–74. New York: Routledge.

- McMahon, S., and N. Sigona. 2018. Navigating the Central Mediterranean in a time of ‘crisis’: Disentangling migration governance and migrant journeys. Sociology 52 (3):497–514. doi:10.1177/0038038518762082.

- Menéndez, A. J. 2016. The refugee crisis: Between human tragedy and symptom of the structural crisis of European integration. European Law Journal 22 (4):388–416. doi:10.1111/eulj.12192.

- Panebianco, S. 2019. The Mediterranean migration crisis: Humanitarian practices and migration governance in Italy. Contemporary Italian Politics 11 (4):386–400. doi:10.1080/23248823.2019.1679961.

- Penninx, R., T. Caponio, B. Garcés-Mascareñas, P. Matusz Protasiewicz, and H. Schwarz. 2014. European cities and their migrant integration policies: A state-of-the-art study for the Knowledge for Integration Governance (KING) project, KING Project overview, paper No. 5. Milan: ISMU Foundation.

- Rhodes, R. A. W. 1996. The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies 44 (4):652–67. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x.

- Scholten, P., and R. Penninx. 2016. The multilevel governance of migration and integration. In Integration processes and policies in Europe. Contexts, levels and actors, ed. B. Garcés-Mascareñas and R. Penninx, 91–108. London: Springer.

- Slominski, P., and F. Trauner. 2018. How do member states return unwanted migrants? The strategic (non-)use of ‘Europe’ during the migration crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1):101–18. doi:10.1111/jcms.12621.

- Stoker, G. 1998. Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal 50 (155):17–28. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00106.

- Tortola, P. D. 2017. Clarifying multilevel governance. European Journal of Political Research 56 (2):234–50. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12180.

- Triandafyllidou, A. 2014. Multi-levelling and externalizing migration and asylum: Lessons from the Southern European islands. Island Studies Journal 9 (1):7–22.

- Van Hear, N., O. Bakewell, and K. Long. 2018. Push-pull plus: Reconsidering the drivers of migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6):927–44. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384135.