ABSTRACT

Experimenting with a new materialist diffractive approach, this article offers an insight into the agential capacities of lines by juxtaposing two apparently unrelated cases of large-scale drawing practices: the aesthetic process involved in an event of artistic creation and the scientific process of visual representation of data-supported meteorological measurements. The article makes use of the analysis of Jim Denevan’s land art as a tool with which to approach cartography-based colonial politics in the Naqab/Negev Desert (Israel). Such an unusual methodological strategy assists in exposing how political decisions based on the system of scientific classification of land have contributed to the substantial reconfiguration of settlement patterns in the region, negatively affecting the life of a significant number of Bedouin Arabs, indigenous to this land. By investigating the possibly harmful, highly politicised potentials of cartographic endeavours while uncovering their material-semiotic contingency, the article reveals how the enterprise of mapping space can benefit colonialism and discriminatory politics. The aim is to offer a cultural studies understanding of the problematic political and environmental developments taking place in the Naqab/Negev, explaining how the science-based politics of drawing has been mobilised for the purpose of colonial policy, translating into the discriminatory treatment of the indigenous population while extrapolating spatial injustices in the region.

A Story

IndigenousFootnote1 to the area, the Bedouin community currently comprises more than a third of the population of the Naqab/Negev,Footnote2 yet only 12.5% of the officially recognised settlements are designated for it (Rotem Citation2017). Similar disproportions apply to the patterns of land administration in the Naqab/Negev (Abu-Saad and Creamer Citation2012, 36). Moreover, the population of approximately 90,000–100,000 Bedouin living in Israel (out of 400,000 in total, and out of 300,000 in the Naqab/Negev region) currently inhabit ‘illegal’ – thus deliberately marked as exceptional and erased from the official maps – villages and other areas of the region. Also, as a result of political and spatial developments orchestrated by Israel, the well-established Bedouin techniques of low-intensity cultivation and grazing have been severely limited, significantly reconfiguring indigenous lifestyles, which typically rely on situated forms of human – land relationality. Owing to the policy of dispossession and forced urbanisation implemented by the state, paired with the colonial project of ‘making the desert bloom’, today the Bedouin townships – Rahat, Ar’arat an-Naqab (Ar’ara BaNegev), Kuseife (Kseifa), Shaqib al-Salam (Segev Shalom), Hura, and Laqiya – remain squeezed between the northern desert edge (spotted with Jewish-only settlements and covered with relatively vast green areas) and the hyper-arid terrains in the south (which the processes of desertification are systematically pushing northwards) ().

Figure 1. Northern threshold of the Naqab/Negev desert (Israel). The location of urban Bedouin communities: Rahat, Ar’arat an-Naqab (Ar’ara BaNegev), Kuseife (Kseifa), Shaqib al-Salam (Segev Shalom), Hura, and Laqiya. The green areas denote artificially irrigated zones, either forests or terrains located within, or administrated by, Jewish-only settlements. The biggest greenish patch on the right is the Yatir Forest, the largest Israeli forest. Via GoogleMaps (April 2022).

From Drawing to Making: An Introduction

As noted by Tim Ingold in his seminal work The Life of Lines, the study of lines is a ‘territory that rightfully belongs to the science of meteorology, or maybe to students of aesthetics’ (Citation2015, iix). Inspired by this assertion, while aligning with Ingold’s anthropological interest in lines’ intriguing liveliness (Citation2007, Citation2013, Citation2015), in this article I approach ‘the technologies of drawing (on) a desert’ from a feminism-inspired new materialist perspective. My analysis offers an insight into the agential capacities of lines by juxtaposing two apparently unrelated cases of large-scale drawing practices: the aesthetic process involved in an event of artistic creation and the scientific process of the visual representation of data-supported meteorological measurements. The former, seemingly unharmful case was produced in 2009 on the Black Rock Desert in Nevada (US) by the artist Jim Denevan; soon after, the giant drawing was washed away by a sandstorm. The latter case, at first glance equally innocent in nature, refers to the classificatory work undertaken by pioneering meteorologists at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, later to be translated into successive political decisions concerning the colonial conquest of the desert’s threshold. While cartography-aided colonial policy has had a considerable impact in several parts of the world (cf. Lacoste Citation1976), for the purpose of this analysis I investigate the substantial reconfiguration of settlement patterns in the Naqab/Negev Desert (Israel),Footnote3 negatively affecting the life of a significant number of Bedouin Arabs, indigenous to this region. While the heavy discrimination against the Naqab/Negev Bedouin by the Israeli state has been extensively studied over the past forty years, the original contribution of my analysis consists in disclosing how the discriminatory processes in the region have been facilitated by seemingly innocuous classificatory practices embedded in the Western scientific project, mobilised for the advancement of the Zionist settlement policy in Palestine. Thus, by reading these two cases diffractively, my intention is to draw attention to the ‘material-semiotic’ (Haraway Citation1988, 595) nature of the technologies of ‘drawing on land’. My aim is also to emphasise the consequential character of these activities, which have produced noteworthy environmental and political effects, albeit – as far as the two discussed cases are concerned – of a quite dissimilar nature.

Patrick Maynard defines drawing as a process in which ‘an object such as a fingertip, piece of chalk, pencil, needle, pen, brush … having something like a tip, which we therefore refer to as a “point”, is intentionally moved (drawn) over a fairly continuous track on a surface’ (Citation2005, 62). As he further underlines, ‘This action leaves, as the trace of its path, a mark of some kind, and is done for that purpose’ (Citation2005, 62). Thus, drawing consists of an important material reconfiguration, regardless of how enduring the discernible traces it leaves behind remain. Nevertheless, looking solely at what the process of drawing consists of is not sufficient to truly account for its compound nature, as drawing happens to be richly generative. Thus, it cannot be understood as an entirely neutral process, much less an innocent one. In fact, rather than being seen as a merely representational practice (and, as such, implying depiction, or multiplication, of what is already there), the act of drawing should be perceived – at least in certain cases – as an instance of meaningful intervention, potentially unleashing/catalysing new reconfigurations. The materiality of drawing – when ‘intra-actively’Footnote4 (Barad Citation2003, Citation2007) entangled with the discursive layers to form a complex, albeit ephemeral, entity – generates ‘material-semiotic’ (Haraway Citation1988, 585) effects. It has already been made clear by Ingold that there is a very close affinity, even a correspondence, between the processes of drawing and making, as ‘sketches are on their way towards propositions’ (Citation2013, 126; emphasis in original). According to such an understanding, drawing often enables – or conditions – making, substantially contributing to its very materialisation. As I intend to demonstrate in this analysis, the focus on the material character of drawing, and how it assembles with semiotic structures (which the process of drawing itself co-constitutes), exposes its deeply interventionist character as much as its reliance on material agencies. It also reveals how data-based drawing can potentially translate into politically informed, including vehement, actions, generative of new socio-political and ecological realities.

A new materialist approach, such as the one adopted in this analysis, helps us to realise how what is considered the ‘representational’ practice of (scientific) drawing is never merely about semiosis, but remains deeply embedded in and supported by, as much as productive of, material processes and reconfigurations. Bearing this in mind, and employing a diffractive method, my aim is to offer a cultural-studies understanding of the problematic political and environmental developments taking place in the Naqab/Negev and operating to the detriment of the indigenous population, by reading them critically through the lens of Denevan’s land art. This unusual methodological strategy not only allows for an illumination of the complex, multiscale character of both science-based political processes and artistic procedures; it also sheds an altogether different light on the possibly harmful, highly politicised potentials of cartographic endeavours, exposing how the enterprise of mapping space – as already recognised by Yves Lacoste (Citation1976, Citation2012) – can benefit colonialism and discriminatory politics. Therefore, in the second part of the analysis, I focus on the spatial (in)justice (Dikeç Citation2001; Soja Citation2010) experienced by the Naqab/Negev Bedouin as a result of the Israeli colonial (Yiftachel Citation2008) developments in the region. The concept of spatial (in)justice directs attention to the role that spatialisation (that is, the mode of production of space) plays in the processes of domination and repression (Dikeç Citation2001, 1787). Spatial (in)justice is not limited to questions of distribution but remains closely connected with the right to relate to and collectively produce a space-based political life (Dikeç Citation2001, 1790). In the case of the Bedouin community in Israel, these rights are seriously limited by the state. To fully understand this policy’s logic, and its important environmental dimension, it is necessary, I argue, to explore the role of the scientific system of classification of space, accounting for the tangled character of the technologies and apparatuses of drawing involved in this practice.

Reading Diffractively

Diffraction is identified as a conceptual tool for research into the material-semiotic reality of the contemporary world. It is believed to open novel interpretative planes for approaching the complex phenomena situated not only at the intersection of different academic disciplines, but also having multiple social, political, cultural, or material facets. As a form of critique, it has been framed as a particularly feminist instrument to counter the dominant, binarised forms of knowledge production grounded in representationalism. As Anna Hickey-Moody, Helen Palmer, and Esther Sayers point out, both Donna Haraway (Citation1997) and Karen Barad (Citation2003, Citation2007) – the initiators of feminist diffractive thinking – conceive of diffraction as a ‘non-linear method of reading and writing in which stable epistemological categories are challenged, temporalities are disrupted and disciplines are complexified’ (Hickey-Moody, Palmer, and Sayer Citation2016, 217; see also van der Tuin Citation2014). Diffraction is a phenomenon originally defined within classical physics and describes a situation in which waves, upon encountering an obstacle or overlapping with other waves, diffract in new directions and produce new patterns and new overlaps – something that Barad perceives as ‘patterns of difference that make a difference’ (Citation2007, 72). Similarly, for Haraway,Footnote5 diffraction can work to expose how ‘interference patterns can make a difference in how meanings are made and lived’ (Citation1997, 14), destabilising the taken-for-granted assumptions while displacing well-established classifications and conceptual divisions. According to Birgit Mara Kaiser and Kathrin Thiele, diffraction may serve ‘to move our images of difference from oppositional to differential, to move our ideas of scientific knowledge from reflective and disinterested to mattering and embedded’ (Citation2018, xi). This signals a substantial shift in understanding the practices of knowledge creation, calling for acknowledgement of a situated nature of what we know.

As Evelien Geerts and Iris van der Tuin note, in contemporary feminist theory, and especially in its new materialist variant, diffraction tends to denote ‘a more critical and difference-attentive mode of consciousness and thought’ (Citation2016, n.p.). Diffractive thinking ‘implies a self-accountable, critical, and responsible engagement with the world’ (Geerts and van der Tuin Citation2016, n.p.). This suggests, in academic terms, a deeper insight into materialities, their agencies, and their relational becomings, as much as a profound interest in, and commitment to, the socio-political realities in which we dwell. When applied in engagement with texts/narratives/drawings/cases, a diffractive approach postulates a dialogical mode of delivering a critique, enabling the creative reading of texts through one another (Barad Citation2007, 30). In Kaiser and Thiele’s words, ‘it is attractive as an image of thought and a praxis of analysis that foregrounds difference rather than sameness’ (Citation2018, xii; emphasis in original). Such a formulation makes possible new interferences and unusual conceptual alliances, shedding light on what otherwise might remain unnoticed, or silenced, in the critique. Thus, diffraction is about constellations and relationalities, maximising the potential of, and opening new routes for, a truly critical and self-reflexive inquiry. By no means is knowledge that is produced in this way meant to be classificatory or taxonomising; it remains performative (Seghal Citation2014, 188).

As applied in this kind of analysis, a diffractive approach, I propose, enables a better comprehension of the diverse materialisations the act of drawing consists of and generates. It also exposes the tangled material-semiotic practices and apparatuses involved in the procedures employed within the field of politically motivated cartography, as well as accounting for its multiscale political effects. Since cartography emerges as a constellation of lines – lines being the domain of both aesthetics and meteorology, as underlined in Ingold’s previously mentioned remark (Citation2015, iix) – in this diffractive exploration I make use of Denevan’s artistic practice as a companion with which, perhaps even a prism through which, to regard the transformative agencies of the cartography-based process of drawing a desert. My engagement with this specific example of land art also serves as a bridgehead for reflecting on the entangled material-semiotic aspects of the drawing process itself, exposing the sheer materiality of this act. Thus, in an experimental attempt at putting together issues pertaining to the domain of meteorology and political science on the one hand and creative practice on the other, I propose a methodological strategy which consists in critically approaching cartography-based decision-making processes. This adds to the cultural studies of science as applied to the fragile context of the ethnic conflict in the Naqab/Negev, aiming to explain how the politics of drawing has been mobilised for the purpose of an ideology-informed colonial endeavour, translating into the discriminatory treatment of the indigenous population while extrapolating spatial injustices in the region.

Obviously, the status of the two cases discussed in this article is not the same, and I devote considerably more space to the analysis of the situation of the Bedouin community in Israel than to the exploration of Denevan’s artistic practice.Footnote6 Rather, the latter is meant to serve as a creative tool with which to approach the complexities of the science-based political developments materialising in the Naqab/Negev. As such, following Haraway’s statement that ‘it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with’ (Citation2011, n.p.), by diffracting the story of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin with Denevan’s practice of land art, my intention is to delve into the material-semiotic densities of the Israeli colonial policies, heavily shaped by dominant Western ways of scientific thinking/knowing. This is a premeditated choice, as a close engagement with the emergence (and disappearance) of Denevan’s ‘work of art’ (Bolt Citation2004, Citation2014; emphasis in original)Footnote7 invites exploration of the complexities of the events of making (here, enabled by an act of power-infused cartographical drawing). This methodological decision encourages a detailed inquiry of the relationalities involved in the act of creation while facilitating a strategy of constant rescaling of the adopted perspective: from the focus on the situated details of material-semiotic processes of drawing to the zoomed-out view of its larger-scale entanglements, as well as of their meaningful effects.

Both cases explored in this analysis are preoccupied with, and conditioned by, the material-semiotic ontology of the desert. Whereas Denevan’s work exploits techniques of drawing on a desert, the understanding of the consequences of the Israeli colonial policy toward the Naqab/Negev Bedouin can be broadened by investigating the scientific processes of determining/mapping/drawing a desert’s threshold. Moreover, in both cases, the practices mobilised for their production remain co-determined by the agency of lines, indispensable for the emergence of a drawing understood either as an outcome of aesthetic practice or a result of cartographical endeavour. While attentiveness to lines in analysing the ‘life’ of the drawing on a desert may be seen as a somewhat natural field of interest, the exploration of lines in studying the enduring ethnic conflict within the boundaries of a Middle Eastern country appears slightly less obvious. By no means, however, is my interest in cartography accidental in the context of analysing the political developments in the Naqab/Negev. As the case of the Bedouin community inhabiting this area illustrates, cartographical technologies are at the roots of discriminatory political decisions, while geography-based understandings tend to be deliberately employed for the advancement of the Israeli colonial project in the region.

Visual descriptions of space – in the form of maps – can be instrumental in the undertaking of violent enterprises, serving as tools for taking control over land and its resources. Spatial data – reworked as drawings – happen to be weaponised in state-orchestrated military/colonial efforts, not only for defining a specific state territory but also for structuring socio-political and environmental relations within its borders. This has been especially salient in the project of building the State of Israel, officially proclaimed in May 1948, which forced a political redefinition of Palestinian land and a new organisation of social relations within the borders of a newly established state. As Yves Lacoste notes in his 1976 book La géographie, ça sert, d’abord, à faire la guerre, the discipline of geography, and the cartographic endeavours effectuated within it, must be understood as an important tool of social organisation and control. Lacoste underlines that ‘All colonial conquests were first geographical undertakings not only through the drawing of maps of the topography for reconnaissance purposes but also of the territorial and historical disputes between different ethnic groups’ (Citation2012, iv). Several scholars emphasise that the technologies of mapping space are at the origins of statehood (cf. Branch Citation2014, Citation2017; Briggs Citation1999; Caquard and Dormann Citation2008; Krupar Citation2015; Neocleous Citation2003; Steinberg Citation2005; Strandsbjerg Citation2008); therefore, maps – and the apparatuses involved in their creation – emerge as active agents participating in the processes of sustaining power (Crampton and Krygier Citation2006). Mastery of cartographical technologies (of surveying, measurement, printing, interpreting, distributing, etc.) is essential for producing specific understandings and experiences of space (Corner Citation2011; Harley Citation2001; Pickles Citation2004; Wood Citation2010). Thus, although maps themselves do not provide explicit spatial constraints, they function within contexts co-formed by practices and ideas which define the conditions of possibility of both the cartographic tools and their products (Branch Citation2017). As Jordan Branch asserts, ‘The definition and operationalisation of territory as spatial expanses separated by lines depends on the ability to negotiate, measure, and draw those lines, on maps and on the ground’ (Citation2017, 137). My analysis engages with a practical facet of this process.

In what follows, focusing on the two case studies, I will look at two dimensions of the procedure of drawing (on) a desert, namely the technologies of drawing involved in these events and the larger-scale political and environmental developments with which they entangle. This study is not meant to be exhaustive, as there are other aspects related to these two diffractively explored cases with which I will not engage here, mostly due to spatial constraints. Hence, this article is an invitation to further investigate the agential liveliness of lines – understood in aesthetic, technological, scientific, and political terms – with an aim to better grasp the complexities of our material-semiotic realities.

Technologies of Drawing

As Patrick Maynard asserts, ‘Drawing itself is rarely seen as itself but is rather taken for granted’ (Citation2005, xv; emphasis in original), thus conceptualisation of drawing ‘may be said to be a barely existing theoretical topic’ (Citation2005, 3). However, as he suggests, ‘the modern world is to a high degree the drawn one’ (Citation2005, 12), so close attention devoted to the practices and consequences of drawing may enhance understanding of the complex conceptual and material realities in which we dwell. Careful engagement with aesthetic practices, especially those exploiting drawing as their basic technique, may urge us to reconsider the complex textures and layers involved in creational activities, as well as acknowledging their potentially interventionist nature. Drawing consists of material encounters, a coming together of materialities, which produces a perceptible trace. Thus, the practical effect – both the mark left on a surface as a result of an encounter of different bodies and the more general result the practice is meant to achieve – is in a way inherent in the event of drawing. It matters what kind of bodies (materials, surfaces, techniques, instruments) are involved in the process. A close engagement with the relations constituting the practice of drawing contributes to an enhancement of our understanding of both the means and the meanings for which they are used. It also positions drawing as a technology which is not only enabled, but also substantially co-constituted, by other technologies; thus, what emerges from the process remains tinged with their agential materialities.

Drawing on a Desert

Jim Denevan’s artistic project in the Black Rock Desert (2009) emerges from spatial interactions between the lines and agential reconfigurations of the setting in which the work of art is situated. The logic of the emergence of the drawing is supported by the responsive collaboration of the artist’s body (and technological instruments – extensions of the bodily capabilities – used for leaving marks on the surface) and the surrounding landscape (understood as a dynamic assemblage of various materialities and natural forces operating in the area). Denevan’s practice is framed as a dialogical conversation with the site, a sensible response to its rhythms and dynamics, a cooperation with forces indigenous to the place, and a relational becoming of and with the site. Given the large scale of the project – the drawing was discernible even from space, thanks to a view enabled by airborne imagining techniques – it demanded the inclusion of specific tools in the process of its production. Along with the standard equipment used by Denevan’s team (such as sticks, rakes, and brooms), a heavy pick-up and a motor coach were needed for rifting the dry surface of the desert. Thus, both the planned result of the project (or what the drawing was supposed to be) and the setting in which it was produced co-determined – as well as themselves being co-determined by – the composition of technological apparatus necessary for their very emergence.

The use of heavy technical equipment was considered necessary to bruise the land of the desert with traces deep and wide enough to be perceptible from a long distance (in this case, a high altitude), a perspective allowing for the materialisation of the view of the drawing in its full breadth and length.Footnote8 Also, the drawing was predesigned, based on several earlier sketches (of different scale) and mathematical calculations, all meticulously effectuated to determine the final shape and size of the project, as well as to carefully design the trajectories of lines supposed to form a specific visual constellation. Still other technologies were used to document the project (digital cameras, software necessary for processing pictures, planes and helicopters enabling materialisation of the right perspective to record the fleeting life of the artistic work) and to display it in other sites (such as galleries or online archives). While a view from the ground allowed for the appreciation of the situated materialities involved in the creational endeavour, familiarising the observers with the means through which the visual effect was achieved, a ‘god-trick’ (Haraway Citation1988) perspective – produced within the assemblage of technological devices – ensured the project’s representational operations, in both the short and long run. Thus, the representational nature of the work of art, even though thoroughly embedded in, and conditioned by, the particularity of material traces rifted in the ground, emerges only from a distanced, disengaged point of view, to a great extent oblivious of the forces operating on site. Such a methodological rescaling of the examination of the work of art’s becoming exposes the material-semiotic complexity of the practices of drawing, delving into the practicalities and technologies involved in, and conditioning, the emergence of the artistic object. It also highlights the deeply relational nature of the project, documenting how the process extends far beyond the immediate act of drawing, and how its multitemporal becomings, also afar from the site in which it was created, are co-constituted by the agencies of a multiplicity of technologies and forces.

Aligning with the spirit of land art, according to which the work of art should remain unfinished and open to future interventions, Denevan’s site-specific oeuvre is returned to the landscape. It is gradually annihilated in the process of the becoming of the site, to the point of erasing all perceptible traces of the project. The gusting of the wind and a sandstorm wiped away the drawing. These movements, however, could not be understood in terms of the process of returning the site to its original, immaculate shape; rather, the disappearance of the drawing serves as obvious evidence of the metamorphous nature of the site itself, ruled by a whole range of material forces, including those which are not immediately perceptible to the human eye. The same forces to which Denevan’s project was meant to creatively respond now obliterate the lines in a constant process of movement and transformation. Thus, the surface of the desert should not be conceived of as an inert, frozen canvas against which the drawing occurs, but rather as an agential space which is constantly reconfigured by a group of forces actively participating in the becoming (and thus also in the disappearing) of the work of art, and of the site itself.

Drawing a Desert

It may seem that, while discussing Denevan’s work, I take the existence of the desert for granted. Conversely, I am far from conceiving of the desert as an objectively existing reality. Thus, it is now time to reflect on how the idea – as much as empirical actuality – of a desert materialises, and how this materialisation may have meaningful consequences. Certainly, there are different methodologies for defining scientifically what the desert is, while the content of these definitions relies heavily on the complex apparatuses involved in their production. The most popular way of delineating the desert’s threshold refers to the scientific interpretation of the combination of botanical and climate data, or how vegetation that grows in a particular region is dependent upon the temperature and precipitation there. According to meteorological definitions, a desert starts at the threshold of 200 millimetres of annual rainfall. This conceptual establishment – called ‘the aridity line’ – delineates the areas with a dry atmosphere. As described in The Encyclopedia of World Climatology (Olivier Citation2015), ‘Aridity is a function of a continuum of environmental factors including temperature, precipitation, evaporation, and low vegetative cover. Aridity indexes are quantitative indicators of the degree of water deficiency at a given location’ (Vaughn Citation2015, 85; see also Stadler Citation1987). Such a formulation is a legacy of the scientific system of classification of climate developed in the late nineteenth century by Russian-German climatologist and botanist Wladimir Köppen,Footnote9 who drew on earlier biome research.Footnote10 This was a continuation of the nineteenth century parallel endeavours of the systematic botanists committed to arranging the plants into classes, families, genera, and species, and plant geographers preoccupied with mapping the distribution of these plant groups over the earth. As Marie Sanderson notes, Köppen – trained as a plant physiologist – realised that ‘plants could serve as synthesisers of the many climatic elements’ (Sanderson Citation1999, 672). In a truly pioneering manner, he experimented with averaging temperature, evaporation, and precipitation patterns, aiming to determine the liminal conditions in which the cultivation of edible plants was possible. Wheat was used as a benchmark for defining whether land could be used for agriculture, while the measurements and determinations effectuated within this scientific enterprise considered mostly those methods of cultivation and those plant species that were at that time known to the representatives of Western (European) culture. All in all, a complex instrumentarium was developed in order to effectuate the measurements necessary to establish a scientific classification of climate. By turning plants into (parts of) meteorological instruments, Köppen defined climatic regions in terms of plant regions. More work involving meteorological data was later undertaken in order to further develop Köppen’s system, and even though his classification has remained the most influential until today, a brief engagement with some of these attempts may help us to grasp the logic of Western classificatory systems as well as their reliance on measurement and drawing apparatuses.

As Charles Thornthwaite, a continuator of Köppen’s oeuvre, straightforwardly asserts in the opening sentences of his work on a rational climate classification, ‘The direction that the modern study of climate has taken has been dictated largely by the development of meteorological instruments, the establishment of meteorological observatories, and the collection of weather data’ (Citation1948, 55). Nowhere in his study, however, does he question the assumed transparency of such an apparatus (although he complains about its inaccuracy), to a great extent ignoring the situated and deeply relational nature of measurement procedures. Somewhat paradoxically, however, he recognises the compound character of the data used for classification purposes. As he writes, ‘In order to achieve a rational quantitative classification of climate, definite and distinctive break points must be discovered in the climatic series themselves’ (Citation1948, 73). Nevertheless, as he adds, ‘No such break points exist in the data either of precipitation or of potential evapotranspiration. Both run in continuous series from very low values to very large ones. But when they are taken together, there are some distinctive points, and we have a beginning of a rational classification’ (Citation1948, 73). Consequently, the specific pattern – identified as a defining feature of the classificatory system – emerges within an encounter of different kinds of data in the process of human interpretation, in a somewhat artificial procedure of delineating boundaries (or break points). In meteorology, the visual representation of this data takes the form of a constellation of lines connecting the points with matching characteristics, even though – as Deanna Petherbridge asserts – ‘line itself … does not exist in the observable world. Line is a representational convention’ (Citation2010, 90; quoted in Ingold Citation2013, 134; emphasis in original).

When the various climatic elements, such as precipitation or temperature, are plotted on a map, they may appear to be fixed and determined, although they frequently owe their positions to arithmetical and cartographical convenience (cf. Thornthwaite Citation1948). From a new materialist perspective, however, the crucial point of this – and one with rather far-reaching implications – is that ‘the nature of the observed phenomenon changes with corresponding changes in the apparatus’ (Barad Citation2007, 106), that is, no transparency of measurement processes can simply be assumed. Measurement matters as it consists of entangled relationalities, including different forms of matter, knowledge of them, and observers involved in the process of meaning-making, tightly binding together the ontology of things and the epistemological practices involved in the production of knowledge. In a way similar to the workings of the technologies of drawing, which – as exposed in the brief reference to Denevan’s work above – codetermine the final shape of the drawing, measurement apparatus necessarily leaves its traces on what emerges from the process.

The classificatory strategy remains in line with the more general tendencies of Western culture expressed in the attempts at representing the studied phenomena in forms of visually organised grids and taxonomies. Within the logic of taxonomising, however, the categories identified in the system, with clearly delineated boundaries and precisely established contents, are essentially conflict-based. Every classification can thus serve as a canonising (and colonising) device, severely limiting the possibilities of other ways of knowing which cannot be easily squeezed within the predefined grid (cf. van der Tuin Citation2015). Classifications, therefore, can have the effect of disregarding, or suppressing, alternative knowledges, giving preference to what is already known within the dominant knowledge system. Iris van der Tuin, a feminist new materialist philosopher, captures the nature of this phenomenon in the term ‘classifixation’,Footnote11 signalling a Western obsession with control via the production of accurate ‘representations’ of the world. The term is also meant to ‘demonstrate how a classification is not a neutral mediator but is thoroughly entangled with the work that it does’ (van der Tuin Citation2015, 19), or, in fact, the materialisation of the depicted phenomena. In her insightful analysis, van der Tuin refers to Foucault’s (1994 [1966]) salient questioning of the ‘taxonomical’ tendency to organise knowledge in a grid-like order, which points out that ‘all classifications exist under the spell of an episteme’ (van der Tuin Citation2015, 28). Foucault’s genealogical approach enables him to expose how the taxonomy emerges as a conjunctive operation of language and things which co-constitute one another through the complex play of a word (classifier) and a world (classified). Referring to Haraway’s influential concept, assuming the located nature of knowledge, van der Tuin evinces that Foucault’s criticism clearly exhibits that ‘classifications do not provide Truth, but descriptively express situated knowledge’ (Citation2015, 28). Importantly, ‘classification becomes classfixation once [it is] naturalised’ (van der Tuin and Verhoeff Citation2022, 47) and subsequently operationalised. The primary role of definitions in knowledge production processes is clearly expressed in Thornthwaite’s statement about the definitions of moisture regions which, for him, ‘appear to be in final form’, yet ‘Further work is needed to improve the means for determining potential evapotranspiration, moisture surplus, and moisture deficiency. This may lead to revision of the location of the moisture regions but will not change the definition of them’ (Citation1948, 76).

This institutional/cultural context of producing meteorological knowledge, or – specifically – drawing a desert’s threshold, matters onto-epistemically as well as politically. The ‘deficit’ of water, used as a defining feature of arid areas (i.e., those with less than 200 millimetres of annual rainfall, conventionally called ‘dry deserts’), is here understood through a thoroughly anthropocentric lens, referring to a condition that severely limits the possibilities of human use of the land for agriculture or livestock farming. Moreover, the ‘technologies’ of using the land are also specifically defined, denoting such methods of cultivating/grazing that were known to, or elaborated by, particularly situated populations. In a colonising, even epistemicidal (Santos Citation2007, Citation2014), move such an approach considers these conditions, as well as the potentialities they create, from a Eurocentric perspective (even though this situatedness remains unacknowledged), ignoring other (indigenous, non-Western) methods of cultivating the land (e.g., the different practices of dry agriculture developed by people inhabiting arid areas). This is not an atypical strategy, as the processes of underestimating and suppressing indigenous knowledges have accompanied colonial endeavours from their very beginnings. Cartographical and botanical knowledge, the two most highly funded sciences in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Stroup Citation1990), have been successfully used to take advantage of the subdued territories, and botanists were considered ‘agents of the empire’ (MacKay Citation1996, 6; see also Brockway Citation1979, Citation1988; Crosby Citation2015; Fara Citation2003; Schiebinger Citation2004) actively participating in the colonial exploitative and extractive efforts. Certainly, both the delineation of climate zones and the establishing of which regions are suitable for income-oriented agricultural cultivation must be approached as grounded in principles of utility. Thus, utilitarian ethics – quite unsurprisingly for colonial efforts – paved the way for forging understandings of which regions count as potentially useful and which should be considered as wastelands. In such a context, the delineation of the desert’s edge – itself a complex entanglement of practices of knowing (classification) and drawing (cartography) – appears as a politically informed move.

If the aridity line – as well as its specific understandings and uses – emerges, as Eyal Weizman notes (Citation2015, 8; see also Weizman Citation2017), from a complex interplay of different factors situated in particular cultural and historical contexts, its existence cannot be simply assumed. In a new materialist idiom, it consists of: the semiotic entanglement of meteorological data (which itself is a result of specific practices and technologies of monitoring, measurement, and averaging of natural conditions in the area, as well as a material-semiotic effect of scientific classificatory endeavours); a human approach to the land and how it can be exploited (agriculture and the diverse farming machineries used for it); and soil conditions and botanical characteristics (both natural and those currently connected to intensive farming, synthetic agents, modification of the morphology/quality of the cultivated plants or seeds, etc.). In addition, cartographical practice – the act of drawing the desert’s threshold – itself appears as a material-semiotic process, as well as a venture rich in consequences. Thus, the existence of the desert cannot be taken for granted, as what is considered ‘a desert’ materialises within complex and dynamic relationalities and multi-scale entanglements. It emerges as an outcome of measurement and drawing, an actualisation that could have come out differently if measuring/drawing apparatuses were modified. Such a framing immediately questions the conditions under which the measurement/drawing was effectuated, calling for an attentive, situated approach. Thus, the desert necessarily bears the imprints of the practices and apparatuses involved in its material-semiotic production. And so do the political after-effects that such a process generates, especially as they are immediately and situationally experienced on the ground rather than solely being approached from a detached ‘god-trick’ (cf. Haraway Citation1988) perspective.

Political-Environmental Entanglements

The utilitarian understandings of land and its characteristics also lie – at least to a certain extent – at the origins of Denevan’s work, as nowhere else could it materialise on such a large scale, due to the potential interferences it would have produced on land already designated for particular uses (e.g., residential areas, industrial sites, agricultural terrains, military zones). But, from a pragmatic human-centric perspective, the desert is considered a wasteland, an ‘empty’ space situated beyond the zone of immediate practicality. When approached through utilitarian logic, the environment of the desert seems to remain relatively unreceptive to typical human exploitation, figuring as a deadland area delineated by the 200-millimetres isohyet, symbolically cut off – with a line drawn on a map – from the more ‘welcoming’ territories put at human disposal. But the lines on the ground are far more elusive than those drawn on a map. While isomers, isohyets, isohalines, isotherms, and isobars aspire to classify the surface of the ground according to fixed definitions, the processes happening on site continually work to blur these utilitarian distinctions, complexifying not only the straightforward taxonomies, but also the realities they intend to capture. As we learned from the close engagement with Denevan’s desert-based practice, the drawing of a line (whether on a map or on the ground) does not freeze the forces dynamically operating in the area. The site remains in a process of constant becoming, co-constituted by different factors entering into always-new relationalities and assemblages.

The meteorological lines drawn on maps oftentimes fail to satisfy the basic requirements of the classificatory system, as they cannot be automatically related to the truly active climatic factors they are meant to visually represent. Moreover, the geometric Euclidean line – itself an abstract figuration – does not have any thickness, while the organic, natural, fluctuating delineations on the ground – similarly to Denevan’s carvings – cannot be reduced to such a ‘non-space’. Consequently, when approached from the ground, the threshold of the desert remains in constant movement, a reconfiguration that the geometry-based cartographical representations are never able to seize and fix. People dwelling in arid areas, aware of the changeable meteorological patterns observable in the region, find their ways to make use of the land, even though it is perceived as inarable according to dominant (i.e., Western) standards. Geographers are aware of the fact that a space cannot be treated as a readable surface that can be comprehensively mapped (Lefebvre Citation1991, 142), as ‘the logic of visualisation has a vastly reductive power, flattening out the volume and depth of … reality’ (Butler Citation2012, 62) while tending to fully abstract understanding of space from its material embeddedness. Policymakers, however, often seem to ignore the contingent nature of the cartographical visualisation, preferring – in a rather pragmatic manner – to rely on visual intelligibility and readability, to a great extent divorced from, or openly ignoring, the concrete values that the space embodies for indigenous communities. They also tend to disregard the site-specific methods of using land considered as too arid for conventional (Western) forms of agricultural cultivation.

As has been the case in many other parts of the world – most notably in the areas of Northern Africa, South Asia, or both Americas being subject to different forms of European colonisation – in the Naqab/Negev the colonisers’ ignorance of the indigenous ways of using the land (in the Naqab/Negev case, based on techniques of dry farming and pastoralism)Footnote12 was not only a mere absence of knowledge about these communities, but a component of the cultural and political struggle for domination (cf. Schiebinger Citation2004, 3). In the Naqab/Negev, the meteorological delineation of the desert’s threshold has been instrumentalised for colonial purposes, which makes it a markedly salient case by which to demonstrate the impact of the science-based politics of cartographical drawing. As a result of the aerial inspection of the land undertaken by Israel, drawing on photographs from the British Mandate period, all the land considered a desert was classified as mawat,Footnote13 or ‘dead land’, as it was deemed as unsuitable for cultivation. Based on such a classification, during the 1950s, the land corresponding to 90% of the Naqab/Negev desert and 50% of the enclosed area was confiscated by the state (Falah Citation1989). Such a handling of land served as a mechanism for implementing a modern Western order of things, as contrasted with the site-specific methods – typically represented as traditional and retarded (Dinero Citation2010) – embedded in Bedouin culture.

The legal interpretation of land classification led to a substantial reconfiguration of settlement patterns in the Naqab/Negev. Whereas in the 1940s most of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin dwelled in the western part of the region, where the land is more fertile, after 1948, while most of them took refuge in the West Bank, Gaza, or North Sinai, a significant number of them were placed by the state in an area corresponding to around 10% of the Naqab/Negev, where, during the period of 1953–1966, they were subdued under Israeli military rule in a zone called Sayig (or ‘fence’). Within this area discriminatory mobility restrictions applied, even though in 1954 the Naqab/Negev Bedouin were granted Israeli citizenship (Marx Citation1967, 12; see also Law-Yone and Abu-Saad Citation2003; Lithwick Citation2003; Nasasra Citation2015). In the 1970s, Israel launched a programme of ‘regularisation’ of space (Rotem Citation2017) in the Naqab/Negev. Aimed at cleansing the region of indigenous inhabitants, it assumed transferring the Bedouin population to deliberately designed townships. A programme of evictions and resettlement was also designed. Although in the official rhetoric the project was presented as a means of integrating the Bedouin population within the national market economy, in fact it was premised on the logic that the protracted physical presence on a particular piece of land may signal a legal title to ownership of this land (as delineated in particular regulations of the 1895 Ottoman Land Law), which was considered dangerous for the vital interests of the Israeli state.

In 1965 Tel as-Sabi (Tel Sheva) was established as a Bedouin-only town. Rahat was built in 1972, while subsequent townships – Ar’arat an-Naqab (Ar’ara BaNegev), Kuseife (Kseife), Shaqib al-Salam (Segev Shalom), Hura, and Laqiya – were founded in the 1980s. The Israeli government used several incentives to encourage the resettlement of the Bedouin (Dinero Citation2010; Yiftachel and Meir Citation1998) in exchange for relinquishing any land claims, thus this option was only appealing to landless families. Moreover, the architecture of townships did not respond to the typical practices of dwelling, or ‘taskscapes’ (Ingold Citation2000),Footnote14 of the Naqab/Negev indigenous communities. This fact, in a truly colonial way, has been systematically ignored by the Israeli authorities responsible for the infrastructural developments in the region. The implementation of these politically informed efforts was enabled by a careful cartographic aerial documentation of the land, allowing for the systematic zoning of the Naqab/Negev into residential, agricultural, military, and public areas, thus rendering the space ready for defined forms of consumption. Earlier, meteorological classification of the region as a desert legitimised the strategy of confiscating the land by the state, now responsible for its thorough ‘management’; as a result of zoning, since the 1970s the Bedouin settlements located on the land categorised as mawat have been delegalised and symbolically erased from the official maps. Cartographically invisibilised, they remain doomed – as Oren Yiftachel observes – to increasing informality and temporality (Citation2006, 199). Their inhabitants materialise as ‘intruders’ or ‘trespassers’ on their own land (Kedar Citation2001, 927). While, since 1999, Israel has officially recognised 11 Bedouin villages, the remaining 35 – located mostly within the region formerly delineated as Sayig – still await a governmental decision. The structures erected by their inhabitants are subject to state-inflicted demolitions, understood as a means of correction when the space – classified in its predetermined way – is ‘misused’. The existence of the ‘illegal’ villages has been systematically ignored in the process of siting several noisy and unsafe facilities (such as electricity grids or toxic industries), causing delayed harm. Overall, the standard of living in Bedouin townships and villages (both recognised and unrecognised) is extremely poor. They lack appropriate infrastructure (e.g., transportation, proper housing) and basic facilities (e.g., health services, waste management, pipelines, schooling) while their architectural composition impairs any possibilities of cultivating indigenous practices of dwelling. Demolitions are frequently undertaken if the space is not used in a way desired by the state. Located at the aridity line (), with populations almost completely cut off from the traditional ways of making use of arid areas, they suffer from severe spatial injustice, especially in comparison to the constantly increasing number of Jewish-only settlements established in the Naqab/Negev and tasked with implementing the ideologically constructed project of colonising the desert’s threshold.

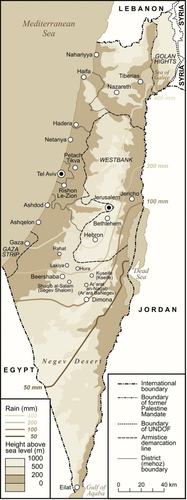

Figure 2. Current precipitation patterns in Israel. Based on data published in 2021 by the Israel Meteorological Service, available at: https://ims.gov.il/en/ClimateAtlas.

This is where the peculiar bifurcation of the Israeli policy towards the desert can be discerned, exposing the politically pragmatic nature of the declaration of the desert land as mawat. Whereas the use of land by the Naqab/Negev Bedouin remains restricted, which is officially motivated by both political and environmental reasons, the desert has been undergoing systematic colonisation by Jewish settlers – albeit with mixed results – from the inception of the Zionist settlement project in Palestine. Even though the impetus of the celebrated mission to ‘make the desert bloom’ has been significantly slowed down – especially in the aftermath of Israel’s swift victory in the Six-Day War (1967), which partly redirected settlement activities towards the Occupied Territories (Gaza, West Bank, and Sinai) – the domestication of the desert still tends to ignite the Israeli collective imagination. It is also frequently instrumentalised for the actual political interests of the state. Given the prevailing science-based categorisation of the land based on the distribution and type of vegetation, the agriculture-centred orientation of the first phase of the Israeli conquest of the desert appears as commonsensical. As the general purpose of this enterprise was to change the characteristics of the climate zone, thus re-categorising it according to the already established scientific classification based on the type of vegetative cover, plants have been mobilised as agents of change in the battle against the harsh conditions of the desert.

The desert has occupied a special place in the Jewish imaginary since the beginning of the nineteenth-century Jewish immigration to Palestine. It figures as a mythic land, from which the ancient Jews had been expelled, and which deteriorated during their exile. The return to the Promised Land must thus be accompanied with the effort to redeem both the land and the people (McKee Citation2016), and redemption is only achievable through the settlers’ effective work of cultivating the land (Sternhell Citation1998; Zakim Citation2006). Hence, for Israel, the value of the desert, as Yael Zerubavel notes, ‘appeared to be conditional on its future transformation into a settled land’ (Citation2019, 7; see also Zerubavel Citation2008). Typically for colonial endeavours infused with orientalising (Said Citation1978 (2003); see also Hochberg Citation2007) tendencies, the wilderness of the desert was represented as an enemy to be conquered, or – according to the colonial rhetoric – to be pulled out of its backwardness and uselessness and turned into a flourishing garden. Thus, aligning with colonial discourse, the settlement of the desert was perceived as a civilising mission, turning the arid areas into prosperous agricultural terrains. Complex scientific and technological machinery was used in order to infuse the ‘wasteland’ with the spirit of modernisation and development, or to take control of its natural rhythms and forces by experimenting with agrarian techniques () in a number of Jewish settlements established across the desert. Conditioned by the dispossession of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin, this policy gained momentum in the 1950s and further flourished in the 1960s. In this period, seven Jewish towns, some of them agriculture-related, were established in the Naqab/Negev (Arad, Dimona, Mitzpe-Ramon, Netivot, Ofaqim, Sderot, and Yeroham), while the existing towns of Beersheba and Eilat grew substantially (Portnov and Erell Citation1998). The installation of the Yarkon-Negev pipeline in 1955, which transported water to the region, diverting it from other areas, was instrumental in developing the project of ‘greening’ the region, forcing the desert to gradually retreat.

Figure 3. North of Eilat farmers of the village of Yutvata find a way to develop a prosperous agriculture using salty water to grow vegetables all year around and a sophisticated dairy farm (original description). Dan Hadani, Agriculture in the Negev Desert, 1969. Copyright, the National Library of Israel. From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of the Dan Hadani Collection, the Pritzker Family National Photography Collection.

Planting forests was used by the Jewish settlers as another strategy to battle the ‘chaos’ of the desert. Deeply rooted in the Jewish symbolic imaginary, trees – and especially the European species – were considered as instruments for putting down roots in the mythic land of Palestine. In the early twentieth century, still in a pre-state period, Jewish settlers considered the mission of planting forests chief in their efforts of colonising the land, or redeeming it from the ‘chaos’ which emerged during the Jewish nation’s absence from the area. In that sense, forests did not figure as spaces of wilderness; they were perceived as an embodiment of culture encroaching on the undeveloped and neglected area of the desert. Forests thus served as instruments of land regeneration, but also as living memorials to individuals and communities. The Jewish National Fund, established in 1901 as a unit tasked with purchasing land in Palestine, was highly engaged in the mission of afforestation,Footnote15 especially since – according to Ottoman law – trees could be considered as markers of land ownership (Zerubavel Citation1996, 97, see also Zerubavel Citation2019; Cohen Citation1993). In Israel, the practice of raising funds for, and collective planting of, forests in Palestine was highly ideologised and ritualised (), and trees became imbued with heavy nationalist symbolism, resonating with memorial politics as well as more current ethnicity-based political developments (such as expulsion and dispossession of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin). The technology of afforestation envisages planting trees in regular rows and only specific species are used, which embodies the modern, geometry-based dimension of ‘domesticating’, or taking control of the land. The biggest afforestation project in the Naqab/Negev is Yatir Forest (), which consists of over 4 million trees; smaller projects include the Lahav and Be’eri forests. Two types of afforestation programme are currently implemented in the Naqab/Negev: one is a dense planting of Aleppo pine, and the other is a low-density planting of exotic drought-tolerant deciduous species (a strategy known as ‘savannisation’). While the former requires generous irrigation (which causes the salinisation of soil), the latter is blamed for the degradation of natural conditions in the region. Savannisation involves the removal of endemic vegetation, as well as landscaping to create terraces to capture surface runoff which, as a result, does not end up in the wadis, the main areas for traditional Bedouin agricultural cultivation.

Figure 4. Planting trees following the forestation plans surrounding Jerusalem. IPPA Staff Photographer, 1970. Copyright, the National Library of Israel. From the collection of the National Library of Israel, courtesy of the Dan Hadani Collection, the Pritzker Family National Photography Collection.

Owing to the implementation of the technologies of ‘greening’ the desert, substantial parts of the Naqab/Negev area are now covered with geometrically arranged fields and forests, meticulously planned settlements, and lines of roads connecting them with each other. The cartographic order – a predesigned constellation of lines – embodies the (colonial) principles of modernisation, rationality, and advanced technology introduced into the otherwise ‘disordered’ wasteland of the desert. The project of taking control of the desert takes the form of introducing straight, methodically planned lines into the landscape, interpreting them as a measure of scientific progress and development (cf. Eveden Citation1992; Jackson Citation1979) as opposed to the untamed, virgin ‘counter-space’ (Zerubavel Citation2019) of the desert. As a result of this cartographical activity, the organic environment of the desert was dissipated according to the principles of geometry. Similarly to Denevan’s drawing in Nevada, the lines – whose trajectories are scrupulously devised – figure as technologies enabling the mastery, albeit temporary, of the landscape. Advanced equipment is necessary to implement an ambitious project of drawing (on) a desert. Denevan makes use of the advanced achievements of a petrofuel industry to ensure durability of his work of art, both for materialising the aerial perspective, from which the representational wholeness of the project can be fully appreciated, and for distributing knowledge on it through online and offline sites and activities. Even though initially imperceptible to the human eye, these interventions – and the apparatuses employed for their production – leave meaningful traces behind them (in the form of pollution, the reconfiguration of micro ecosystems, partial devastation, increase of the greenhouse effect). They happen to be ignored, especially because the site on which the giant drawing emerges remains considered as a wasteland. In such circumstances, Denevan’s practice passes, rather wrongly, as benign and innocuous, as it does not interfere with any other human-centred activities, since – on account of its properties – the land has not been assigned for any uses that the aesthetic project could negatively affect. Hence, invisibly dispersed across vast areas of land, thus stretching beyond the immediate site of their artistic materialisation, these meaningful traces are trivialised as supposedly harmless or irrelevant.

Differently, the effects of the scientifically and ideologically engineered ‘politics of planting’ (Cohen Citation1993) appear as far more serious, materialising both in the directly concerned areas and elsewhere. The survival of the intensive agriculture and artificially planted forests in the Naqab/Negev depends on irrigation infrastructure, and thus requires continuous human intervention. The water is diverted to the Naqab/Negev mostly from the Jordan River and the Sea of Galilee, causing substantial water deficits and degeneration of the landscape in the West Bank, hence producing – instead of countering – further environmental degradation. The dark patches of forest, exposed to the high sunlight radiation typical for such geographical zones, produce surges of evapotranspiration.Footnote16 Ironically, the state-sponsored programme designed to battle desertification ended up generating greater water shortages; typically for such situations, the negative consequences of these processes – entangling political and environmental dimensions – are experienced most severely by the most vulnerable communities in the region.

The colonial policy of conquering the wilderness of the desert has been deeply discriminatory. While Jewish settlers have been encouraged to move to the Naqab/Negev region and engage in efforts towards its ‘domestication’ through technologically enhanced agriculture and farming, the rights of the indigenous inhabitants of the area have been systematically violated by the policy of dispossession and forced urbanisation. Legal constraints have been systematically introduced to limit the traditional ways of using land cultivated for centuries by Bedouin communities of the Naqab/Negev. Their organic connection to the ‘chaotic’ environment of the desert has been suppressed, even ‘criminalised’ (cf. Gilmore Citation2002), and their traditional ‘taskscapes’ (Ingold Citation2000) irreversibly destroyed. In 1976, the state even created a law-enforcement unit, meaningfully called the Green Patrol, whose task is to counter any ‘misuses’ of the space. Exploiting the pro-environmental discourse and the rhetoric of preventing climate change, the unit inflicts demolitions of structures erected by the Bedouin, blaming the community for exacerbating the environmental degradation in the region. Such politics of the distribution and management of space rests on ethnicity-based principles, according to which the representatives of the dominant group (the Jews) are placed above the minoritarian Bedouin community in the socio-political hierarchy.Footnote17 This negatively affects both the quantity and the quality of space placed at the disposal of different ethnic groups.

Intensive afforestation, agrariasation, urbanisation, industrialisation, and militarisation – all employed in the service of the science-based ‘regularisation’ of the Naqab/Negev space, and all preceded by a carefully undertaken politics of cartographical planning – have generated several spatial injustices. Due to the extensive agricultural use of virtually all the land located in the north and northwest of the Naqab/Negev region – enabled by artificial irrigation from wetter regions, mechanised cultivation, and extensive use of new seed types, synthetic fertilisers, and pesticides – those practicing traditional and more sustainable forms of land use have been pushed to drier areas. These lands are typically even more susceptible to degradation, especially when the desert pushes back to the north, disregarding – as in Denevan’s work – the geometric lines introduced within the state-sponsored colonial policy to define its new contours and functions.

Concluding Remarks

In The End of Cognitive Empire (Citation2018), Boaventura de Sousa Santos exposes the involvement of Western ways of scientific thinking in the broader project of colonial/patriarchal/capitalist exploitation, indicating the need of a thorough epistemological transformation. While, in most parts of the world, colonialism ‘has come to an end as a political relationship’, it persists ‘in the shape of the coloniality of power’ (Santos, Nunes, and Meneses Citation2007, xlix), manifesting, inter alia, in knowledge production practices. The story of the spatial-social reconfiguration of the Naqab/Negev region referred to in this article clearly exposes the complex entanglement of colonialism and scientific imagination, paving the way for openly discriminatory, extractive politics. It also illustrates how various forms of disciplinary knowledge within the spatial sciences, embodied in the system of the classification of space, combine with the ideology-infused utilitarian politics of exploiting the land. This calls for a nuanced analysis of how the unsituated knowledges, typically positioned as a landmark of Western objectivism-driven scientificity, can become instrumentalised for the purpose of the advancement of discriminatory politics, and what kind of realities, as they are situationally experienced on the ground, emerge from the complex entanglement of scientific and political/ideological discourses and practices. In the case of the Naqab/Negev, such an approach enables an understanding of how Zionism has meticulously combined scientific, rational techniques of managing space with an ideologised, emotional connection to the land of Palestine. Interestingly, reliance on such a strategy positions the Zionist settlement project as different from other colonial land-centred endeavours driven by purely extractive motivations.Footnote18 Attentive examination of these entangled material-semiotic processes allows for the exposure of how – in certain conditions – ideas can materialise as powerful forces as well as how – in the case discussed in this article – fluent command of cartographical and meteorological tools, an epitome of modern science’s tendency towards taxonomising and control, if mobilised for emotionally framed political interests, can substantially contribute to this process.

Closer investigation of the apparatuses of knowledge production, as well as examination of knowledge’s embeddedness in complex material-semiotic practices, enables a more profound engagement with the project of rethinking the oppressive structures of power embodied in Western ways of knowing. In such circumstances, a critical new materialist commitment to methodological experimentation – as well as to the exploration of the how question of producing knowledge – remains of the utmost importance, as it creates spaces for more equality-oriented conceptual developments and for acute, situated examinations of how knowledge matters onto-epistemically and ethically. In such a context, a diffractive strategy assists in finding critical continuities between different scientific disciplines, ways of thinking, and diverse socio-cultural, political, and material phenomena. The sensible engagement that the new materialist study of artistic practices invites can shed a new light on the material nature of drawing (on land), paying attention to the complexity of material and semiotic factors involved in the process of both artistic creation and the generation of scientific knowledge. Such a perspective offers a novel prism through which to examine the production of political and social materialisations. This can contribute to pluralising and diversifying the extant landscape of knowledges, while inviting more situated and attentive accounts of the complex realities in which we dwell. Given the difference-sensitive orientation of new materialist philosophy, as well as its investment in efforts aimed at producing change, it can help us, in Barad’s idiom, ‘to breathe life into ever new possibilities for living justly’ (Citation2007, x).

Acknowledgements

Some of the ideas offered in this article were presented and discussed within the ad-hoc Design Studio: New Materialist Articulations at the Technical University of Vienna in April 2021, to which I was invited by the convenors of the event, Iris van der Tuin, Nanna Verhoeff, and Vera Bühlmann. I am grateful for this opportunity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The idea of indigenous rights refers, by definition, to the rights of a community (rather than individual rights of its members). International law does not mention such rights, as it remains conservative in its understanding of a state’s integrity; it also refers to a state as a social contract between the citizens and the sovereign. However, due to a surge in claims for the recognition of indigenous rights raised by many groups around the world, in 2007, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples was approved by the UN General Assembly with the support of more than 140 nations. In the case of Israel and the claims to indigenousness raised by the Naqab/Negev Bedouin community, there is a dispute over who counts as more indigenous, in the context of the convoluted history of the region, marked by multidirectional migrations and shifts in power among different ethnic communities. Several Israeli academics (see, for instance, Yahel, Kark, and Frantzman Citation2010) contest the indigenousness of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin, which attests to the fact that the issue is highly politicised and using the term in reference to particular communities involves taking a side in the conflict. In this article I use the term ‘indigenous’ in reference to the Bedouin of the Naqab/Negev. For a detailed discussion of the problem of indigenousness in international law, see Lerner (Citation2003), Anaya (Citation2004), Thornberry (Citation1991), Wiessner (Citation1999), Abu-Saad and Champagne (Citation2006), and Champagne and Abu-Saad (Citation2003). For a discussion of the Naqab/Negev Bedouin’s indigenousness, see Stavenhagen and Amara (Citation2012), Martinez-Cobo (Citation1986), and Amara, Abu-Saad, and Yiftachel (Citation2012).

2. I am using the double name of the region throughout the article. The desert is called the ‘Naqab’ by the Palestinian Arab population, while it is referred to as the ‘Negev’ by the Jewish population. I use the two names with a slash to represent the colonial reality of this area.

3. The reconfiguration of the settlement patterns in the Naqab/Negev region is a complicated issue. My discussion of it within this article is necessarily cursory and limited only to those aspects that remain crucial for the argumentation developed here. For more detailed discussion, see Golańska (Citation2023).

4. The concept of ‘intra-action’ (Barad Citation2003, Citation2007) signals the deep material-discursive entanglement of different agents and forces in the never-innocent procedures of producing knowledge. ‘Subjects’ and ‘objects’ cannot be taken for granted as pre-existing the relations in which they enter; rather, they emerge as a result of the complex relations they constitute and through with they are co-constituted in return.

5. Haraway refers to optical patterns of diffraction.

6. I have engaged more closely with Jim Denevan’s work in Golańska (Citation2018).

7. The term ‘work of art’, rather than an ‘artwork’, is used by Barbara Bolt to signal the work that the art is capable of doing, thus to point to the transformative nature of art (cf. Bolt Citation2004, Citation2014).

8. Extensive visual documentation of the Black Rock Desert (2009) project is available at https://jimdenevan.com/project/black-rock-desert-nv-2009/. Accessed 22 April 2022.

9. The results of his study were published in 1931.

10. Whereas the classification of climate is attributed to Köppen, the invention of the term ‘aridity index’ is attributed to Thornthwaite (Citation1931, Citation1948). This does not mean that there were not previous attempts at classifying climate. For a historical overview, see Sanderson (Citation1999).

11. van der Tuin (Citation2015) rehearses this term in the context of the problematic efforts at canonising feminist scholarship.

12. The agricultural techniques practiced by the Bedouin community of the Naqab/Negev, as Meir (Citation2009) and Meraiot, Meir, and Rosen (Citation2021) explain, should in part be considered an outcome of an adoption of ancient Nabatean knowledge regarding land use through terraces since their arrival in the region several hundred years ago.

13. Crucial to understanding any move to declare a particular land as mawat is the difference between mawat and miri land, as articulated in the 1858 Ottoman Land Code (articles 78 and 105). Mawat is a land inappropriate for cultivation, or a ‘dead land’, uninhabited and not possessed by any individual. As Amara and Miller explain, ‘Land was determined as mawat based on three possible measurements: (1) the point at which a loud voice from the nearest village, town, or inhabited place could no longer be heard; (2) half an hour’s walk from the nearest inhabited place; or (3) 1.5 miles away from the inhabited place’ (Citation2012, 82). However, the same regulations state that if anyone revived mawat and cultivated it for ten years without dispute, that person would acquire a titled deed to the land, even though it was still formally owned by the state. Such land was than categorised as miri. The fact that – for fear of taxation on the one hand, and because their ownership rights were not threatened by the ruler on the other (Kedar Citation2001; Swirski Citation2008) – the Naqab/Negev Bedouin did not register the land they used with the authorities in 1921 (under the ordinance that everyone wishing to cultivate mawat had to obtain state permission and thus register with the state) worked to their disadvantage under Israeli rule. The state authorities refused to consider their land as miri or as inhabited, as they had an interest in declaring as much land as possible as mawat, so that it could – by definition – be categorised as state land.

14. Ingold explores the co-formation of inhabitants and landscapes, asserting that landscapes emerge as products of ongoing ‘taskscapes’ (Citation2010; see also McKee Citation2016).

15. The afforestation efforts in Israel are officially framed as ‘reforestation’, which aims to restore the land to its pre-exile state, when it was represented as green and fertile (see Zerubavel Citation2019, 97).

16. As underlined by Rotem, Bouskila, and Rothschild (Citation2014), the 9-year study carried out in the Yatir Forest by Rotenberg and Yakir (Citation2010) found that the fact that the forest absorbs CO2 at a rate close to the global average for forests must be weighed against ‘the negative impact of increased heat absorption’. The darker shade of the forest, as contrasted with the surrounding natural area, causes a decrease in reflective heat radiation (which is called the ‘albedo or reflection coefficient’). Thus, ‘while the absorption of the CO2 has a cooling effect at the global level, the decline in the albedo value results in increased heating values. It can take decades before the cooling effect will be greater than the heating effect in forests in semi-arid regions, and up to 80 years in the case of Yatir Forest’ (Rotem, Bouskila, and Rothschild Citation2014, 42).

17. It is necessary to note that the power relations in the Naqab/Negev region cannot be reduced to the Jews – Bedouin binary. Multiple intersecting polarities of hegemony can be identified in the area. These include the dissimilarities in settlement patterns between Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews and the differences between rural and urban environments, as well as a variety of core – periphery extrapolations. Although it is not possible to comprehensively account for these tangled dynamics in a single article, it is necessary to keep them in mind while tackling the complexities endemic to the region. However, considering the space limitations, and given the fact that the cartography-based politics in the Naqab/Negev explored in this article has most significantly affected the Bedouin community, my analysis remains focused only on the Jews – Bedouin axis.

18. I would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for suggesting such an understanding.

References

- Abu-Saad, I., and D. Champagne, ed. 2006. Indigenous Education and Empowerment: International Perspectives. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

- Abu-Saad, I., and C. Creamer. 2012. Socio-Political Upheaval and Current Conditions of the Naqab Bedouin Arabs. In Indigenous (In)justice: Human Rights Law and Bedouin Arabs in the Naqab/Negev, ed. A. Amara, I. Abu-Saad, and O. Yiftachel, pp. 19–66. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Amara, A., I. Abu-Saad, and O. Yiftachel, ed. 2012. Indigenous (In)justice: Human Rights Law and Bedouin Arabs in the Naqab/Negev. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Amara, A., and Z. Miller. 2012. Unsettling Settlements: Law, Land, and Planning in the Naqab. In Indigenous (In)justice: Human Rights Law and Bedouin Arabs in the Naqab/Negev, ed. A. Amara, I. Abu-Saad, and O. Yiftachel, pp. 68–125. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Anaya, J. S. 2004. Indigenous Peoples in International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Barad, K. 2003. Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28 (3):801–31. doi:10.1086/345321.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bolt, B. 2004. Art Beyond Representation: The Performative Power of the Image. London: IB Tauris.

- Bolt, B. 2014. Beyond Solipsism in Artistic Research: The Artwork and the Work of Art. In Material Interventions: Applying Creative Arts Research, ed. E. Barrett and B. Bolt, pp. 22–37. London: IB Tauris.

- Branch, J. 2014. The Cartographic State: Maps, Territory, and the Origins of Sovereignty. London: Cambridge University Press.