ABSTRACT

Although it has rarely been addressed as such, the regulation of disability within migration governance is a geopolitical issue. This article examines how refugee resettlement intersects with ablenationalism, an ideology that treats disability as exceptional, thereby shoring up the exclusionary terms of citizenship. Drawing on findings from our multi-sited study (2016–2019) of the resettlement of Iraqis to the US, we show how the fantasy of the ‘disability con’ and fantasy of the ‘bogus refugee’ feature overlapping logics. Asylum officers routinely question asylum seekers’ narrations, pointing to holes in logic, inconsistencies, embellishment, and perceptions of scripted stories as reasons for denying asylum claims. Our study shows how these moments of suspicion can double-up or intertwine for refugees seeking disability exceptions in the naturalisation process. We argue that the disenfranchisement of those who seek naturalisation on these grounds reproduces ablenationalist exclusion and shores up a geopolitics of impairment and militarised refuge.

Introduction

In 2018, as part of a suite of 1,059 immigration policies amended during the Donald J. Trump administration, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) proposed changes to the ‘Medical Certification for Disability Exceptions’ form (Immigration Policy Tracking Project Citation2022). This form, known as N-648, creates a disability exception to certain requirements of the naturalisation process, which legal permanent residents may file along with their citizenship application (N-400). Completed and signed by a medical authority, the N-648 attests to the medical basis for a physical or mental disability or impairment expected to last 12 months or longer, and how this impairment or disability prevents the person from learning English or civics to pass the required tests. The updated 2019 version of the N-648, which went into effect in 2020, increased the length of the form from 12 to 23 questions, to solicit information about the date when the impairment began, how the impairment affects daily functioning, and whether the impairment is a result of illegal drug use.

This change to a relatively obscure form was not inconsequential but rather intensified an already existing convergence between ableism and nationalism in practices of refugee resettlement and naturalisation. During the public comment period on the rule change and the time of its implementation, immigration and refugee advocates were outspoken about the onerous length of the form, potential unknowability about when an impairment began, and overreaching nature of questions about daily functioning (City of New York Citation2019; CLINIC Citation2019; Naturalization Working Group Citation2021). Revised guidance for USCIS agents published in the USCIS Policy Manual (Citation2022) also added new grounds for officers to find credible doubt, discrepancies, and fraud. The Immigrant Legal Resource Center (ILRC) concluded this increased latitude would ‘greatly increas[e] the already high level of scrutiny’ on these cases (Citation2019, p. 2). The assessment by Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLINIC) was even more stark, asserting that the new provision on daily functioning ‘wrongfully presumes fraud’ (Citation2019, p. 6).

The regulation of disability within migration governance is a geopolitical issue, stitching transnational mobility to state sovereignty and nationalisms. This article examines how the geopolitics of migration, specifically refugee resettlement, intersects with ablenationalism, an ideology that treats disability as exceptional, thereby shoring up the able-bodied and able-minded terms of citizenship (Grech et al. Citation2022; McRuer Citation2018; Mitchell and Snyder Citation2015; Snyder and Mitchell Citation2010). Contributing to and building upon scholarship in geography that has aimed to investigate and challenge ableism (Chouinard Citation1997; Crooks, Dorn, and Wilton Citation2008; Dorn and Keirns Citation2010; Dyck Citation2010; Park, Radford, and Vickers Citation1998), we focus on the intersection between disability and transnational migration to explore how disability becomes geopolitical and geopolitics informs disability (cf. Kirby Citation2020; Snyder and Mitchell Citation2010). Scholars examining the connections between migration and disability often begin with the World Health Organization estimate that some 15% of people in the world are disabled, that disabled people are among those who are on the move, and that the reasons why people move across borders – conflict, persecution, economic dislocation, disasters – also create impairments that may be experienced as disabilities (Burns Citation2017; Pisani, Grech, and Mostafa Citation2016; Smith-Kahn and Crock Citation2019).

Extending the scope of studies on disability within the asylum process to address how these dynamics play out at the point of naturalisation (Crock, Ernst, and McCallum Citation2013; Pisani, Grech, and Mostafa Citation2016; Soldatic et al. Citation2015), our work sheds light on how militarised refuge reproduces ablenationalism in the resettlement process. By ‘militarised refug(e)e’, Yến Lê Espiritu articulates the co-constitution of refuge and refugees, which ‘are both the byproduct of US militarism’ (Espiritu Citation2014, 2). Initially used to analyse the militarised displacement and resettlement of Vietnamese refugees by and in the US, the concept helps to inform a similar situation for Iraqis who were displaced by US wars and subsequently resettled in the US. The idea also has been extended by feminist geographers as a way to recognise the military-humanitarian imbrications of forced displacement (Jacobsen Citation2022; Loyd and Mountz Citation2018; Loyd, Mitchell-Eaton, and Mountz Citation2016). An important contribution of the concept of militarised refuge is to make visible how the administration of refugee lives is entwined with other instruments of social and political domination, including liberalism, patriarchy, racism, and heteronormativity (Espiritu and Duong Citation2018; Fekete Citation2001; Luibhéid Citation2002; Nguyen Citation2012). In this article, we examine how techniques of disenfranchisement that are bureaucratically enacted across the fields of disability determination and refugee resettlement further constitute the United States as a site of militarised refuge.

Bureaucratic procedures and documentation such as visas, passports, and diagnostic classifications are central aspects of asylum, naturalisation, and disability benefit processes. Such paperwork, which purports to establish the identity and veracity of an individual’s self-presentation, is part of what disability studies scholar Ellen Samuels refers to as biocertification, or state documentation that claims to ‘authenticate a person’s biological membership in a regulated group’ (Samuels Citation2014, 9). While the regulation of mobility and the administration of disability have been entwined since at least 14th century English Poor Law governing vagrancy (Stone Citation1984), biocertification became a central part of US immigration policy during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Vagrancy was incorporated into 1882 legislation as ‘likely to become a public charge’, and medical terms of exclusion were added to this category in subsequent legislation. These medical categories – including emergent frameworks like the IQ for measuring intelligence – upheld norms of able-bodiedness and able-mindedness that were rooted in racialised, elitist, gendered, and systems of power and domination (Batra Kashyap Citation2021; Baynton Citation2016; Luibhéid Citation2002; Snyder and Mitchell Citation2006). As states sought to know and regulate their body politics, medicine became enrolled in ‘fantasies of identification’ that would unequivocally identify and categorise persons in terms of race, gender, and ability, and ‘validate that placement through a verifiable, biological mark of identity’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 2). Given that these categories do not originate in the biological and that their social categorisations shift over time and space, biocertification can never achieve the fantasy of perfect identification. Its inevitable imperfection becomes cause for perennial changes in procedures and development of new scientific tools (fingerprints, DNA, biometrics, etc.), yet its failures are individualised and shifted onto inscrutable subjects, who are then met with ‘perpetual suspicion’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 14). In short, they are treated as ‘disability cons’, suspected to be faking their impairment or conning the system (Samuels Citation2014, pp. 52–3).

The fantasy of the disability con and fantasy of the bogus refugee feature (virtually) identical logics. Asylum officers routinely question asylum seekers’ narrations, pointing to holes in logic, inconsistencies, embellishment, and perceptions of scripted stories as reasons for denying asylum claims (Bohmer and Shuman Citation2018, pp. 15–37). This is not to say that fraud has not occurred in either process – it has – but that each instance, however infrequent, becomes evidence for a looming fraud in every application. Our study shows how these moments of suspicion can double-up or intertwine for refugees seeking disability exceptions in the naturalisation process. Disenfranchisement of those who seek naturalisation on these grounds reproduces ablenationalist exclusion and shores up the production and denial of impairment in militarised refuge.

In order to develop our argument that ablenationalism undergirds militarised refuge, we bring together refugee studies with disability studies. Critical arms of both fields attend to the discursive construction of medical, administrative, legal, and regulatory categories – such as the refugee or disability. Such work is centrally concerned with how these often intersecting categorisations distribute and normalise persons into populations, the effects these biopolitical projects have for actual people, and how these technologies of power may be challenged or subverted (Erevelles Citation2011; Espiritu Citation2014, Citation2021; Meekosha Citation2011; Mitchell and Snyder Citation2015; Ngô Citation2011; Schalk and Kim Citation2020; Soldatic and Grech Citation2014). Further, both critical refugee and disability studies have articulated powerful critiques of discourses of deservingness, pitiability, and inspiration that frame refugees and disabled people within two-sided narratives, as either victims to be saved and fixed or as miraculous survivors to be celebrated (i.e., the supercrip and model refugee) (Schalk Citation2016; Tang Citation2015). Such exceptionalist narratives sustain nationalist terms of exclusion and inequality, and obscure geopolitical and geoeconomic productions of impairment, disability, and displacement. In working at the intersection of these fields, our contribution is to show how the terms of militarised refuge are themselves ablenationalist, and thereby work to disenfranchise refugee subjects through the disability exception mechanism in the naturalisation process.

Studying Militarized Refuge

This article emerges from a multi-sited study on the resettlement of Iraqis to the United States since the U.S. and US-backed invasion in 2003. The project has built on the refusal, in critical refugee studies and feminist geopolitics, to dichotomise spaces of war and peace. We were interested in how trauma as a clinical and social phenomenon articulated and reshaped geopolitics (Ehrkamp, Loyd, and Secor Citation2022; Loyd, Ehrkamp, and Secor Citation2018). To trace this process, we conducted fieldwork in Jordan and Turkey in 2015 to 2016 and in the US from 2016 to 2019. Our United States fieldwork was done in two larger and two smaller cities, all sites of substantial resettlement of Iraqis post-2006, and in Washington D.C. In addition to document collection, we conducted interviews and focus groups with over sixty participants in the US.Footnote1 We interviewed people working in refugee resettlement and care as administrators, case workers, mental health screeners, employment agents, counsellors, attorneys, psychologists, social workers, physicians, and community leaders. We also spoke with Iraqis who came to the United States via refugee resettlement and Special Immigrant Visa processes. In the course of our research, we came to understand trauma as a multifold, contested phenomenon. Workers within refugee resettlement and (mental) health care systems carefully tried not to reduce refugees to their (potential) trauma, while at the same time refugee and health bureaucracies also used mental health screening practices to connect refugees with mental health care resources.

Over the course of our fieldwork, a recurrent theme emerged. While naturalisation and disability had not been the focus of our questions, our interviewees working in immigrant care and legal services frequently referred to their clients’ experiences with naturalisation and their own efforts to support them.Footnote2 Some of their observations focused upon the effects that PTSD could have in the naturalisation process, while others focused on other mental health issues or on cognitive issues associated with ageing. They drew on knowledge from work with a number of groups, not exclusively Iraqis.

In US citizenship law and practice, individuals who have been admitted to the United States as refugees are expected to apply for lawful permanent residency (a green card) at one year of physical presence in the U.S. After five years of permanent residency, they become eligible to apply for citizenship. The standard process includes submitting a lengthy application (N-400) and fee ($640 dollars + $85 biometric services fee, increased in 2016 from $595) followed by a series of internal security and background checks; if these are passed, the applicant moves on to an interview with a USCIS officer, which includes an English test and a civics test. If USCIS grants eligibility, the final step is to complete form N-445 and take an oath of allegiance at a naturalisation ceremony.

As we spoke to people working in agencies and community centres that provide extended support services to refugees, including citizenship classes, we began to hear about the all too often attenuated and painful process of naturalisation. Our interviewees told us about how some individuals experienced USCIS interviews as anxiety-producing and retraumatizing because they conjured painful memories, including of being interrogated in other contexts, for example, in the places they had fled. Other clients, for a variety of life course and disability reasons, would not be able to pass the civics and/or English portion of the interview. Some applications had been denied, sometimes more than once. These denials are consequential, including a loss of entitlements, such as Social Security Income, and preclusion from other citizenship rights like voting, international mobility afforded by a US passport, and being able to sponsor family members’ applications for residency. Prolonged time without citizenship means that potential encounters with police might create legal difficulties posing barriers to future naturalisation and risks of deportation.

Cultural orientation materials for refugees and infographics describing the resettlement process for lay audiences overwhelmingly end their narratives at the first 30–90 days in the United States, when formal services often end. This makes invisible subsequent legal steps that are necessary for permanent residency and naturalisation. The ‘USCIS Welcomes Refugees’ guide does delineate these steps, yet how trauma, age, language, literacy, or disability might shape the resettlement experience or trajectory to naturalisation is absent from such expectation-shaping documents. By omission, materials geared to refugees thus assume able bodyminds for permanent refuge, an example of what Espiritu (Citation2014, p. 18) calls the ‘hidden violence behind the humanitarian term “refugee”’ and US narratives of rescue and care (Nguyen Citation2012).

The Transnational, Imperial Context of Contemporary Ablenationalism

In her pivotal Disability and Difference in Global Contexts, Nirmala Erevelles urged feminist disability scholars to attend to racism, colonialism, imperialism, and war. ‘To put it simply’, she writes, ‘war is one of the largest producers of disability in a world that is still inhospitable to disabled people’ (Erevelles Citation2011, p. 132). Erevelles’s call came at a time when, as a result of the efforts of disability justice advocates since the 1970s, disability became established as an issue on the international stage through UN rights declarations, the World Health Organization’s attempts to create a universal classifications system, and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) that came into force in 2008 (Barnes, Citation2020; Berghs Citation2014; Meekosha and Soldatic Citation2011).Footnote3

Amidst this international recognition of disability (rights), the mid-2000s was also a time of deepening inequalities of wealth and power and austerity. Disability studies scholars Mitchell and Snyder (Citation2015) refer to this moment of visibility of disability in the global North amidst neoliberalism as inclusionism. Robert McRuer (Citation2018) calls it disability exceptionalism. They and other critics were concerned that legal recognition and rights would be hollow victories because of the dismantling of or failure to provide material supports necessary to make the rights a lived reality (Berghs Citation2014; Gill and Schlund-Vials Citation2014; McRuer Citation2018; Mitchell and Snyder Citation2015; Sherry Citation2014). Building on Jasbir Puar’s (Citation2007) concept of homonationalism, Snyder and Mitchell introduced ablenationalism, which refers to discourses and policies wherein ‘treating people with disabilities as an exception valorises able-bodied norms of inclusion as the naturalised qualification of citizenship’ (Snyder and Mitchell Citation2010, p. 113). To illustrate, McRuer juxtaposes the celebration of disabled athletes participating in the 2012 London Olympics and Paralympics games with the simultaneous widespread derision of disabled people in the UK as welfare scroungers. The spectacle of disabled athletes performing ‘inspiration’ for world audiences contrasted sharply with protests disabled people staged at the games against the devastating cuts to the UK’s social system. For McRuer, ‘disabled subjects […] who have often extremely limited legal rights or access within a given national context, and whose lives are made even more precarious by a global austerity politics, gain significant representational currency for the neoliberal establishment when situated within local manifestations of the current crisis of capitalism’ (McRuer Citation2018, p. 44, emphasis in original). That is, representations of some people with disabilities as having ‘overcome’ work to obscure simultaneous processes that make most disabled people’s lives more difficult to live.

Since the CRPD entered into force in 2008, these questions of the hollowness of rights amidst austerity and the occlusion of Global South disability justice movements’ demands for transnational redistribution (Soldatic Citation2013) have generated and coincided with critical re-examinations of the social model of disability. Within the medical model of disability, impairments are located within individual bodies, are the source of disability, and represent problems that can be cured or rehabilitated. By contrast, the social model of disability, itself a product of disability activism, counters that impairments are not inherently disabling; rather, oppressive social, cultural and material environments render impairments as disabilities. The significance of the social model of disability should not be understated: Much of the language within national legislation and international conventions reflects the influence of the social disability model (Barnes, Citation2020; Watson & Vehmas, Citation2020). Yet critics, especially writing from decolonial, feminist, and queer perspectives, were concerned that the model could inadvertently reproduce a binaristic frame of the human normalised around ablebodiedness (Rembis, Citation2020; Shildrick, Citation2020), obscure other understandings of impairment and disability in the Global South (Meekosha and Soldatic Citation2011), sidestep issues like chronic illnesses and pain for which some would like medical relief (Clare Citation2017), and ignore the political and economic processes responsible for producing impairment (Meekosha Citation2011).

Ablenationalism enters the picture here because it also obscures the (neo-)colonial and imperial production of disability transnationally. For Meekosha, the Global North’s relative inattention to these harms constitutes a ‘good example of “grand erasure”’ (Meekosha and Soldatic Citation2011, p. 671). Like Erevelles (Citation2011), Soldatic argues that it is through the global arms trade and imperial warfare that the ‘bodies and minds [of people in the global South] embody the injustices of the bio-politics of geopolitical power’ (Soldatic Citation2013, p. 747; also see Meekosha Citation2011; Meekosha and Soldatic Citation2011; Soldatic and Grech Citation2014). On the eve of the Iraq War, disability organisations in the US and internationally vehemently opposed the war for these very reasons. For groups in the US, the war was not only immoral, but would ‘provide a smokescreen’ for the ‘war at home against entitlements’ (Russell Citation2019, p. 121, 124). If the war itself deflected attention from the domestic suppression of disability rights, ablenationalist rhetorics – in which citizenship rights attach more securely to the able – have further and ongoingly worked to obscure the consequences of war making for both Iraqis and disabled people in the US.

The “Mainstreaming” of Disability Within Humanitarian Relief and Refugee Sectors?

Maria Berghs notes a ‘dearth’ of data on disability in the humanitarian sector (Berghs Citation2014, p. 32), which is echoed by scholars studying refugee systems (Burns Citation2020; Grech & Pisani Citation2022; Harris Citation2003). In 2008, one of the first studies on disabilities among refugees was published by the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children (Mirza Citation2011). This came amidst the so-called mainstreaming of disability in UN agencies in the mid-2000s. According to Mirza (Citation2010), through the mid-1990s, the UNHCR was disinclined towards recommending resettlement for disabled people. In 2007, it issued a Heightened Risk Identification Tool to identify women and other vulnerable categories, including disabled people, who at the time were categorised together with people with medical or health conditions (representing the medical model’s conflation of disability with poor health). While this shift has facilitated cross-border mobility for some, Mirza contends it has created a ‘hierarchy of mobility among people with disabilities, where those with less severe disabilities are considered more deserving of resettlement’ (Mirza Citation2014b, p. 229, emphasis in original). There is also a relative dearth of work linking migration and disability studies (Grech & Pisani Citation2022; Soldatic et al. Citation2015). Those that have examined disability within asylum and resettlement processes have found pervasive siloing of the refugee and disability service systems and the persistence of medical and charity models (Bonet and Taylor Citation2020; Burns Citation2017; Harris Citation2003; Mirza Citation2014a; Mirza and Heinemann Citation2012; Smith-Kahn and Crock Citation2019; Soldatic et al. Citation2015). The persistence of this situation nationally and transnationally has led Grech and Pisani to conclude that ‘disability is neither mainstreamed nor targeted in humanitarian action’, an observation that includes the refugee sector (Grech and Pisani Citation2022 p. 201).

Our study does not make claims about the disability or impairment status of Iraqi refugees. We ask, instead, what does it mean that the ‘gift of freedom’ in the form of resettlement (Nguyen Citation2012) is offered by a state that impairs, both through war and a disability exceptions process? To answer this question, we analyse how the disability exception mechanism in the naturalisation process is a transnational one, linking sites of displacement, asylum, and resettlement. We argue that both disability and impairment are produced geopolitically in the entanglement of war, displacement, refugee administration, and naturalisation. As we show, the process nonetheless obscures the transnational production of impairment by situating disability within biomedically diagnosed bodyminds (Clare Citation2017; Ngô Citation2011). In the three empirical sections that follow, we illustrate how the logics and procedures of biocertification are interwoven with naturalisation processes in ways that perpetuate ablenationalism and militarised refuge.

Figuring the ‘Disability Con’ in the N-648 Medical Exception

In the naturalisation process, the N-648 medical exception form becomes part of transnational circuits of refuge and disability. This process is distinct from reasonable accommodations for completing the civics or English language test (such as a sign language interpreter or extra time) provided under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 in that it creates an exception to these requirements. In 1994, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Technical Corrections Act (INTCA), which made an exception for the English language portions of the test. The Immigration and Naturalisation Service (portions of which are now USCIS) began rulemaking only after a lawsuit pressing the agency to do so; it issued its final rule, including the N-648 form, in 1997 (Lyons Citation1999). The form must be completed and signed by a medical professional who must narrate ‘a nexus between the diagnosed condition impairment and his or her [the applicant’s] inability to demonstrate knowledge of English and/or history and government’ (Loue et al. Citation2017, p. 284). This ‘nexus’ works to establish a causal connection between a diagnosis, impairment, and how it affects this particular person’s capacity to fulfill standard requirements of the naturalisation process.

The spectre of the disability con lurks behind new questions on the N-648 form. Since 1997 the form has changed substantially, expanding from four to 8.5 pages in length in the 2020 edition, with a major focus on assuring that medical professionals do not fraudulently complete the forms (Chatzky Citation2020). The Trump-era Citation2020 USCIS Ombudsman Report makes clear that ‘boilerplate’ or ‘one size fits all’ explanations are insufficient evidence for approval.Footnote4 Indeed, repetition, or stock responses, become cause for ‘credible doubt’: ‘Although the generic language may accurately reflect the medical diagnosis for any particular applicant, the pattern [of boilerplate language] itself raises reasonable suspicions that require further inquiries and a potential fraud investigation’ (USCIS Citation2020, p. 22). Since 2017, the form requires use of the ‘relevant medical code’ as systematised in the Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Classifications of Diseases (ICD). Doctors who complete these forms cannot bill health insurance or Medicaid for their services, which means that petitioners must either pay for the services themselves or doctors must provide them pro bono. As one of our interlocutors told us, a local health care agency that worked with significant numbers of refugees had been sent a letter from USCIS effectively saying, ‘You’re on the blacklist for doing these’. As we discuss more fully below, the Citation2021 Biden-era USCIS Ombudsman report concurred that it is often difficult to find ‘affordable medical professionals’ who will complete the forms, and that the 2018 changes made in the name of fraud prevention had ‘created challenges for legitimate applicants’ (Citation2021, p. vii). Refugee-serving doctors are thereby caught in a bind, with specialised care for these groups flagged as part of ‘medical mill’ or ‘doctor shopping’ schemes (cf. Ong Citation1995).

USCIS officers routinely question medical professionals’ expert findings. In one case, a woman passed the civics test by memorising answers to the questions, but could not write. Our respondent recounts, ‘The officer told her, “You’re memorising. You’re not understanding the question. I cannot pass you”, so she came back’. Some of our respondents conveyed that USCIS agents seemed to question some determinations of disability more than others. One attorney indicated:

So, we have some clients that are catatonic, essentially, that can’t speak for whatever reason, that are in almost like 24-hour care situations. And those clients, it seems like, they never give us any problems. And then, we’ve had some clients with like ‘severe mental retardation’ that appear a certain way and are ‘visually identifiable’, I guess, to the officers, so they also don’t really push back on cases like that. Dementia and Alzheimer’s, for the most part, they’re okay with that diagnosis.

Here, the attorney conveys a sense that USCIS officials operate with their own assessments about who is ‘really’ disabled – the ‘“visually identifiable”, I guess’ or ‘like “severe mental retardation”’—that are rooted in eugenicist categories and hierarchies. While some of our interlocutors conveyed that USCIS agents seemed unfamiliar with diagnoses such as PTSD or ‘a cognitive disability or a mood disorder or something with psychosis’, other respondents found familiarity with PTSD on the part of USCIS agents. Yet, USCIS scepticism of medical determinations and a sense on the part of respondents that agents made highly capricious decisions remained consistent as did the sense that some disabilities seemed to be treated as more real or disabling than others.

We can see this non-medical determination of ability and disability at work in the invocation of daily activity or function as evidence of non-disability. Functioning is an element of benefits assessments for the Social Security Administration, which uses the medical model, and in WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (not named for use in the N-648), which considers functioning in context following the social model of disability. Here, though, the question of functioning on the part of USCIS agents uses an undisclosed and seemingly arbitrary set of personal judgements. The same respondent who suggested that USCIS agents employ an implicit calculus of degrees of ‘real’ disability also noted that they are ‘suspicious if you have a driver’s licence’. A different respondent living in a different part of the country also made this observation. Their agency had seen waivers rejected under the logic that, ‘If you were able to get a driver’s licence at some point, then you should be able to pass the waiver even though there are lots of tricks for passing the driver’s licence examination’. One of these ‘tricks’ might be memorisation. Yet, the daily functioning conveyed by possessing a driver’s licence is used to counter medical testimony to a disability diagnosis. The reality that ability can change over time (or as a result of new life events or diagnoses), or that some aspect of a person’s functioning might be impaired while other aspects are not, is summarily sidelined in such a conclusion. Here, the verification provided by a government transportation agency (that itself assesses competence for a particular task) supersedes that of medical professionals, an issue to which we return in the final empirical section of this article.

Other evidence of ability to function was also used to override medical determinations of disability. The same respondent who noted creative ways of passing driver’s licence exams shared how USCIS officers’ simple questions might be used to undermine the claim to disability exception: ‘They’ll say, “What’s that picture of?” and maybe somebody’s able to say, “Cat”, and they’ll say, “Well, you said cat – […] so therefore you can pass”, and deny their waiver’. In this case, conveying knowledge of one image and its associated word in English is used to establish sufficient literacy and cognitive functioning to pass the test. Another respondent – notably a person who was unsympathetic to the use of disability benefits by refugees and viewed medical waivers as a way to avoid learning English – offered what she viewed as a reasonable rationale for USCIS scepticism. When a person who seems to be living their life fully also asks for a medical exception:

And then when you go in and say, “Oh, I can’t learn English because I’m traumatized”, and the officer sees, “Well, you’ve been to Jordan three times”. So it’s like, “Well, it seems like he can function pretty well on normal daily life, and now you’re telling me you can’t”. It’s a hard sell, hard sell.

These examples accord with Samuels’ contention that, ‘One of the most powerful cultural assumptions underlying the fantasy of disability identification is that a person’s state of impairment must be absolute and unchanging and that even the slightest hint of “normal” function renders both the individual and her social categorisation suspect, even criminal in nature’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 130). In the example of the international traveller, the idea that mobility to maintain family connections is disqualifying assumes that disabled people can have no function and cannot (or should not be able to) travel abroad and continue to serve as an integral member of a family. Yet, disconnection from family can undermine relations of care.Footnote5 Bonet and Taylor recount the case of an Iraqi husband and wife who were prioritised for resettlement due to their disabilities. Because their resettlement did not include their families, the process ‘essentially broke up the family unit that had allowed him to thrive his whole life’ (Bonet and Taylor Citation2020, p. 248).

Across these examples of the cat drawing, driver’s licences, and travel, an implicit dichotomising logic of ‘really’ disabled or non-disabled is at work, which reflects an adherence to a medical model of disability even while treating medical determinations with suspicion. These examples further suggest an implicit discourse that disability must mean immobility (at home, within the US) and disconnection (from one’s diasporic communities, family ties). Even as naturalisation would mark inclusion, or the rehabilitation of the refugee subject into the citizenry (Nguyen Citation2012; Ngô Citation2011), the process creates conditions for perpetual exclusion. Through the logics of medicalised, bureaucratised disability and its accompanying suspicions, the refugee themself is cast as ‘the problem’ for naturalisation, while the exclusionary work of ablenationalist norms and practices go unexamined. In the following section, we further examine how this casting of the refugee outside of the demands of disability documentation and legibility takes place, with serious implications for the outcomes of resettlement.

The Problem of Inconsistency: Folding Transnational Space

What makes it so difficult to narrate one’s life such that it conforms with bureaucratic rationalities? As studies from outside the context of refugee resettlement have argued, the unaligned temporality of loss and trauma ‘causes difficulty in legal contexts where survivors are expected to produce orderly, linear accounts of the violence that they experienced’ (Morrigan Citation2017; p. 55; also see Crock, Ernst, and McCallum Citation2013). It is not only trauma and its retroactivity – that is, the way that past events become traumatic in relation to later events (Freud and Breuer Citation2000 [1955/1893]) – that troubles the documentation of events in bureaucratically legible ways. More broadly it is the non-fixity of the ‘truth’ of ‘what happened’. Against the presumption of a single verifiable ‘truth’ of refugee lives, we begin from a recognition that ‘what happened’ is not a stable, pre-existing, and unchanging series of linear events that the subject reveals or hides, shares or withholds. Indeed, any narration of ‘what happened’ – composed of what is possible, necessary, or seemingly relevant to say – cannot be abstracted from the time and place of its articulation. Our approach aims to counter ablenationalist exclusions and to bring into focus the ongoing impact of war and violence – that is, the long arm of militarised refuge – on those who have been resettled (see also Secor, Ehrkamp, and Loyd Citation2022).

When talking about the role of mental health care or years-long engagement with their refugee clients, resettlement workers and other service providers routinely spoke to moments in their clients’ lives when apparent inconsistencies in paperwork arose and became sites of scrutiny. As an immigration attorney we interviewed explained, questions that might appear to ask for ‘simple, biographical information’ such as ‘Are you married?’, ‘How many children do you have?’, or ‘Where have you lived for the past five years?’ can be triggering or even unanswerable at the time of the refugee status determination (RSD) interview held in Jordan, Turkey, or other countries of first asylum. Yet such non-revelations can resurface as an inconsistency years later, and in a different place, in the citizenship process. People’s lives are ordinarily complicated (with marriages and children sometimes part of what gets hidden or disclosed differently in different times and spaces). In the context of war and displacement, the answers to such seemingly basic questions may be wrapped in layers of pain and protracted uncertainty. What an asylum officer initially records may be only part of the story, as in this example that the attorney shared:

So maybe, you got to [a refugee] camp with five of your seven children and you register, but maybe they don’t ask you, “Are there other children that are with you?”. Maybe you can’t even think about those other two kids because you’re so afraid that they’re not alive that you don’t even talk about them in your interview. And then, when it comes time to get your green card, disclosing new children or previously undisclosed children can really be a problem, like a misrepresentation issue.

What gets written down depends not only on what asylum officials consider ‘obvious’ or what is visually apparent about the situation, but also on what a person can bear to say. Uncertainty about whether spouses, parents, and other relatives are still alive may inflect answers to these questions, so too may be the immediate struggle to process or to represent their loved one’s absence. Moreover, reporting certain events may still carry too many repercussions at the moment.

It is well established that some events arise as traumatic for people years later, especially in the presence of exacerbating circumstances such as occur in the process of resettlement in a new country (Andrews et al. Citation2007; Sack, Him, and Dickason Citation1999). When a story that could not be told at the site of first asylum becomes a revelation required to support a PTSD diagnosis in the US, it is not simply that now the truth can be told, but that what is sayable about the event and the significance that can be attached to it has undergone a qualitative reformulation. A case worker shared with us a powerful story of a client’s citizenship application that dragged on for years through multiple reapplications and failures. Our interviewee described how this saga finally came to an end in what would be the successful citizenship interview:

The last time when we went there, the [USCIS] officer looked at the file. Big like this. [gestures to a thick stack of documents] She just closed the file. She said, “I don’t wanna look at any other medical waivers, because I’m tired of them. Tell me who you are and why you have been in this office more than ten times. Tell me what’s going on”.

Finally, with the file closed on the desk, the applicant explained what happened to her. As the case worker recounted:

She was jailed. In the jail, she was raped by a group of military. She got pregnant. Then, like three months when she started to show, they throw her out of the jail with her seven kids. Then, when they were out, they were in the forest because of the war. She fell down and then she lost the baby.

The interview lasted for three hours, the case worker told us. And finally,

The last question [from the USCIS officer] was, “Why wasn’t your information in the bio?” She [the client] said, “But, how was I going to say that? It’s the military who are over there. Am I going to say that they raped me? They’re gonna kill me and my kids”.

The story that was not in the file had been withheld out of necessity, a reckoning to save herself and her children; it simply could not be told in the time and place where it had been asked. In this particular case, there is a breakthrough: the officer closes the file, addresses the person in front of her, and approves the application. Did this happen because the officer shared gendered knowledge about the more than physical violences of rape and its routine silences? Did this happen because the officer knew that rape is a gendered weapon of war (Card Citation1996)?Footnote6 Did these considerations weigh against the spectre of inconsistency? We cannot say. But this outcome did not come without an ordeal, and it did not come as a matter of course. What wasn’t said – and in fact could not be said – created a gap in the paperwork that continued to haunt the client in the naturalisation process. This scenario cannot be uncommon, given the reality and threat of violence that defines the refugee categorically. Rape survivors may not be forthcoming about what happened for fear of retribution, shame, or other emotions. That citizenship applications are then challenged or denied on the basis of such ‘inconsistencies’ reveals that the commitment to ‘fantasies of fakery’ bound up with ablenationalist norms and practices has the capacity to extend the harms of sexual violence and short circuit logic, compassion, and the principles of trauma-informed care.

Where there are wounds, the demand for bureaucratic legibility nevertheless ploughs on. How saturated with pain the site of an ‘inconsistency’ can be emerges, again, in the following case. The story was told to us by the director and employee of a bustling agency that provides a wide range of social services to Iraqi refugees, from help with financial assistance, employment and education to mental health services, trauma-focused therapy, and citizenship workshops. Both were social workers who themselves had come as asylum seekers to the US from Iraq decades previously. They told us about how, in contrast to the short-term mandate of resettlement agencies, their organisation worked with individual clients and families for many years after their arrival, including instituting a ‘citizenship program, even though we don’t have the grant for it, but because it’s so needed’. In the context of explaining the need for this program, one of our interlocutors shared the following wrenching account, in which a man’s story takes on different coordinates at the time of his citizenship application than it had during his RSD interview:

We have many incidents that the officers not only ask them the question or makes them feel comfortable by the question, but they interrogate them, for example, tells them, “This is not what you said in your application at the UNHCR”. We had one incident for the past three years, have not gotten citizen yet. We’re working with a lawyer, with a pro bono lawyer now.

This guy, two of his daughters were kidnapped. In our society back home, when the female gets kidnapped, automatically, automatically, not all of them, automatically, the family abandon her. It’s sexual assault cases. It hurts when you hear that, but it’s the reality. When the family abandons the daughter, [it’s] like she’s never alive, like she’s dead. When they go to their interview, this gentleman went to the [RSD] interview in Jordan, and he told them she’s dead. The truth, she’s not dead. When he came here and he was in treatment for seven years, of course, he told his therapist the truth. He didn’t tell her the truth, she told him, ‘Is this how you feel? Did you abandon her?’ and it took him three years to say yes, and he cried because he felt, now, he starts feeling guilty. In our report, in our N-648 report, we have to say the truth.

This is a truth that appears as a discrepancy in the paperwork because of how the man represented the events of his life at the time and place of his first asylum and how those preparing his N-648 form now represent the ‘truth’ of his situation. Thus, in this process it is not a simple matter of something hidden coming to light or discovery of deception (Bohmer and Shuman Citation2018): it is that the very meaning and emotional impact of the events through which he lost his daughter have taken a new form over the course of seven years of mental health treatment and living in a new country/across transnational space. The N-648 not only reports this new version of events, but affirms it as the relevant, documented truth.

Yet this new ‘truth’ does not correspond with what was sayable, or even emotionally bearable, at the time of the UNHCR interview. In other words, one could say that in Jordan, at that time of his UNHCR interview, his daughter had indeed been ‘dead’ according to how he was able, at that time and place, to speak (or even think) of what had happened. Our interviewee, in her repetition of ‘automatically’, may have been trying to underline for us researchers that the father had responded in a way that was socially prescribed, not as someone making an individual or intentional decision. The ‘automatically’ seeks to hold off any judgement of the father, and to instead emphasise that this initial framing of the traumatic events was a ‘cultural silence’, a term that Shuman (Citation2005) uses to refer to ‘cultural prohibitions to speaking, for example in response to shame and humiliation and other conditions of tellability’ (Shuman and Bohmer Citation2014, p. 941). It was only after several years and working through trauma and other emotions with a therapist, that the initial official story cracked and another one became not only sayable but the ‘truth’ that must (according to the logics of the system) appear on the N-648 report. As a result, the documentation of the father’s situation appears inconsistent for USCIS officers who fold the space of asylum onto the space of the naturalisation interview; the ‘truth’ on his N-648 waiver does not match the ‘truth’ seven years earlier in Jordan. The interview becomes another interrogation, and three years later this tormented father was still struggling for his citizenship.

In all the examples discussed in this section, authorities impose an unrealistic expectation of immutability, which resonates with what Samuels identifies as ‘the overmastering fantasy of disability identification […] that disability is a knowable, obvious, and unchanging category’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 121). Despite being ‘repeatedly and routinely disproved by the actual realities of those bodies and minds fluctuating abilities’, this fantasy persists and permeates the discourse on disability (Samuels Citation2014, p. 121). Likewise, the expectation of an unchanging narrative, especially between the initial UNHCR interviews and the N-648 form that is filed many years later, papers over what is incongruent and inhumane in the system: the doubling down on ‘fantasies of fakery’ with their overweening investment in distinguishing between authentic and fraudulent claims, and the lack of recognition of the violent realities of war and refuge. This expectation of consistency and categorical fixity is thus a site where ablenationalism is asserted in the naturalisation process: the refugee, their life and story, is held to the same damaging standard of immutability that has been used to cast doubt on disability claims and to deny rights to the disabled.

‘Drilling down’: The Violence of Scrutiny and Ablenationalist Refuge

While the mutability of ‘what happened’ is not unique to those who have been resettled, nor even solely the province of trauma survivors,Footnote7 what is notable is that state refusal to grapple with mutability could mean the denial of permanent residency or naturalisation. This denial displaces the right to have rights (Arendt Citation1973 [1951]), producing disabling conditions through what Jacobsen calls ‘war in refuge’, that is, the ways that ‘war and refuge stretch and fold into one another, no longer completely distinct from one another but deeply entwined’ (Jacobsen Citation2022., pp. 1, 7–8, emphasis added).

Despite the fact that the USCIS Policy Manual instructs officers not to ‘second-guess’ medical professionals’ statements (Chatzky Citation2020, p. 156), as we have established, USCIS officers routinely override medical opinions.Footnote8 In so doing, they claim the authority, based on what appears ‘obvious to them’ to determine the ‘truth’ of the lives of resettled refugees, thereby extending the practices of scrutiny that permeate biocertification processes more broadly (Samuels Citation2014). An immigration attorney, whose observations we have discussed earlier in the article, explained the situation,

[…] Especially under the new [Trump] administration, it’s almost like the goal is to find why people aren’t eligible rather than to make more people get benefits. Like, there’s been a shift in how they’re operating. And so, what that means is they’re going all the way back to the refugee file for citizenship cases and saying, ‘Well, you never said that you watched your grandfather burn or that you saw your massacred children when you were going through your refugee interview. So, do you really have PTSD?’ Like, is this something that you’ve come up with now? […] We’ve seen it, too –have had to combat, sort of – USCIS officers diagnosing people.

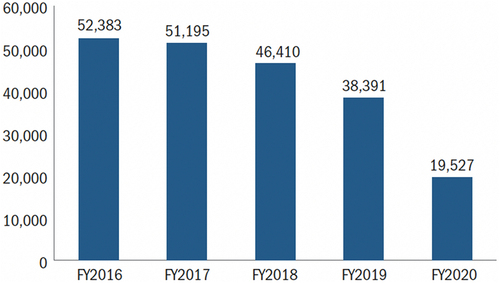

We would like to draw out two aspects of this passage. First, she observes a notable shift in operations under the Trump administration, suggesting that disqualifying applicants motivates scrutiny of applications. This attorney was not alone in making this observation. According to a 2019 nationwide survey of migration attorneys about changes to the naturalisation process during the Trump administration, fourteen of 110 agencies surveyed reported that they had observed more questioning and denial of N-648 forms (Capps and Echeverría-Estrada). While this number does not seem huge, the increased length and detail of the N-648 has had chilling effects on the submission of the form. The 2021 USCIS Ombudsman’s annual report (Citation2021, p. 42) disclosed that there was a steep decline in the numbers of naturalisation applications accompanied by a N-648, from 52,838 submissions in FY2016 to 19,527 submissions in FY2020 (see ). They note particular difficulties for ‘those first admitted as refugees or asylees [who] face specific obstacles by virtue of their history’ (USCIS Citation2021, p. 42). These difficult pasts result in a much higher, but fluctuating, percentage of these applicants also filing N-648s, ranging from 8.3% to 13.4% of submissions between FY2015 and FY2020, compared to approximately 0.5% of other applicants (USCIS Citation2021, p. 43). This report does not indicate the percentage of N-400s filed with N-648s that were rejected for either group. However, in each year between FY2017 and FY2020, USCIS denied applications from those admitted as asylees or refugees at a higher rate than other applicants because of inability to meet English or civic test requirements (USCIS Citation2021, p. 43).

Figure 1. Caption: Forms N-400 Submitted that Included at Least One Form N-648 Between FYs 2016 and 2020 (Source: USCIS Citation2021, Figure 4.1).

Second, the attorney suggests that officers’ questioning– ‘going all the way back’ to the refugee interview – crudely and unnecessarily elicits graphic details about a person’s experiences. Not only does pawing through refugees’ files in search of such inconsistencies extend the authority of the USCIS officer, ‘imbuing the government official with the diagnostic gaze’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 132), but it also does violence to the material and emotional complexities of a life. With every interview a(nother) potentially retraumatizing interrogation, and cases dragging on for years – often through multiple applications and application fees, and sometimes requiring the involvement of pro bono lawyers – the naturalisation process can thus be extended to the point of exhaustion and despair. The situation isn’t helped when guidance for psychologists reproduces ableist and nationalist terms of belonging: ‘A proper conducted assessment and completion of the N-648 form by the forensic psychologist can mean all the difference for the worthy candidate’ (Meyers Citation2020, p. 116).

The problem of how trauma becomes exacerbated in the process of naturalisation converges with practices of heightened scrutiny. The same respondent who expressed some scepticism about other refugees’ claims they could not learn English also told us that:

in this political climate, it’s just gonna be even harder and harder for there to be a willingness from the government to accept what might be obvious. And clearly there are people who are clearly traumatized, and they’re so traumatized that they can’t tell the story the same way each time because [of] their memory and all the things that are involved. But, unfortunately, the USCIS officers haven’t taken trauma-informed survey training.

Once again, the issue of greater scrutiny amidst the Trump administration arises such that ‘what might be obvious’ about how a ‘clearly traumatised’ person acts is no longer so obvious or so clear.

This was not the only time that a respondent suggested that USCIS officers could benefit from trauma-informed training. Such remarks, we think, were meant to draw out the gap between what medical and human services professionals know about trauma and how USCIS interviews too often are traumatising for their clients. It is less certain that they would view such training as a fundamental improvement. When asked whether a USCIS process could be trauma-informed, one attorney replied, ‘It’s not, at all. Not at all. And that’s the thing’. She explained:

I have to drill down. And that’s – messy and awful. And maintain – I feel, as an attorney, I have to maintain a distance for professionality purposes […] There has to be this kind of wall. And that’s the opposite of trauma-informed care.

Also, there’s the idea of choice and dignity. And I hope that I offer all my clients dignity, but in a lot of situations, I cannot offer choice. It’s like, get the benefit or get deported. There’s like this – there’s no choice.

This attorney’s perspective suggests the limits of trauma-informed practices when the legal context is one that requires particular details and forms of narration. When the ‘choice’ to not disclose difficult pasts in an asylum or immigration proceeding can result in the foreclosure of rights and even deportation, the coercive terms of the state prevail over that of trauma-informed practice. As Paskey, citing Gangsei and Deutsch (Citation2007), observes about the potential for retraumatization for torture survivors during the asylum process, ‘because the goal of torturers is often to make their victims talk, a torture survivor may associate talking in a legal setting “with the experience of forced talking under torture”’ (Gangsei & Deutsch in Paskey Citation2016, p. 464). Indeed, we have shown that it is not only torture survivors who experience naturalisation interviews as retraumatizing. Migration attorneys themselves are enrolled in ‘drilling down’, which structurally constrains how much ‘choice’ an applicant has over their narrations of the past.

These foldings of experiences of war and persecution, recounted and documented in particular ways at time of asylum, and then revalidated at time of naturalisation illustrate how the naturalisation process can be traumatic and potentially disabling. Citizenship applications presume one is able-bodied, cognitively and emotionally unimpaired; the exception requires gruelling biocertification. Shuman and Bohmer argue that the asylum process ‘produces particular kinds of cultural silences, invisibilities, and hypervisibilities’ (Shuman and Bohmer Citation2014, p. 940, emphasis in original). Within the naturalisation process, we see how the biocertification of disability rests upon and re-examines these productions, subjecting applicants once again to adversarial scrutiny, this time seeking to expose a ‘disability con’. ‘Drilling down’ into applicants’ life experiences, in turn, shapes the naturalisation process as another site in which the violence of ‘broader structures of imperial and state power’ pierces through refugees’ lives to recreate refuge as militarised and ablenationalist while creating disabling conditions for them in the process (Jacobsen Citation2022, p. 3).

Conclusion

Our article focus on disability exceptions for some resettled refugees exposes how the naturalisation process is a site where a reckoning with the transnational production of displacement and disability is routinely thwarted. Experiences with the N-648 process that our respondents shared both preceded and followed changes made in 2019 by the Trump administration. The expansion of terms of credible doubt in 2019 amplified the tensions in the biocertification process that Samuels identified between medical professionals and state agents. The Policy Manual on this topic reads: ‘In general, USCIS should accept the medical professional’s diagnosis. However, an officer may find a Form N-648 insufficient if there is a finding of credible doubt, discrepancies, misrepresentation or fraud as to the applicant’s eligibility for the disability exception’. CLINIC (Citation2019, p. 6) contended that ‘This question invites the adjudicator to substitute his/her judgement [sic] for that of the medical professional and to use daily activities as an overly simplistic litmus test for N-648 eligibility, such as presuming that someone who can drive can pass the citizenship test’. In November 2022, revisions to the N-648 went into effect, almost two years into the Biden administration. Advocates’ criticisms seem to have been taken into account. The new form is again shorter, at 4.5 pages, and removes questions that legal advocates had flagged, such as daily activities, the cause of a disability, and date of diagnosis. The term ‘nexus’ is no longer used, but the form still asks for how a disability or impairment prevents the applicant’s ability to take the civic exam or learn English (Burdick Citation2022). These changes are welcome, yet it remains to be seen what will happen in practice.While the medical model of disability is the face of the N-648, USCIS agent decisions supersede medical authority, serving as what Foucault Citation1995 [1977] called “the judges of normality” (in Mitchell & Snyder, Citation2000, p. 48).

Our critical examination of state categories shows how fantasies of fakery shore up the legal and bureaucratic spheres of disability and naturalisation, underwriting presumptions and practices that seek to discredit asylum and naturalisation applications. We echo Mirza who found that, ‘Disabled and displaced persons are often constructed as “aberrations in need of therapeutic intervention” and become recipients of institutionalised practices targeted at returning them to the natural order of things’ (Mirza Citation2014b, 217; also see Nguyen Citation2012, pp. 64–65). The higher rejection rate of naturalisation applications from asylees and refugees, and higher rejection of N-400s accompanied by N-648s, which are more often submitted by these groups support this claim and point to how the gift of freedom (Nguyen Citation2012) is an ablenationalist one, assuming people who can be assimilated as able-bodied, emotionally and cognitively highly functioning, and literate. Ablenationalism, in turn, is disabling in that it undermines the possibilities of social reproduction among these individuals by dispossessing them of citizenship entitlements, possibilities for family reunification, and more. Instead of rights, a paternalistic ‘humanitarian’ relationship of subjection and gratitude is maintained. Indeed, Trump administration changes to the N-648–alongside more high-profile migration bans and efforts to extend the use of the public charge rule against low-income immigrants – suggest the heightened defence of what Erevelles calls ability as property, ‘an important property right that had to be safeguarded, protected, and defended in the effort to decide who could or could not be a citizen’ (Erevelles Citation2002, 19).

We concur with Mimi Thi Nguyen, following Ngô, that ‘disability studies must be brought to bear on critical refugee and war studies to challenge the narrative overdetermination of the forcible inscriptions of trauma and disability on racialised others’ (Nguyen Citation2012, p. 64). Here we draw attention to how the determination of disability for the purposes of naturalisation both rests on this narrative overdetermination – and hence prevalence of suspicion – while also undermining material procedures to attend to actual people’s lives. Meanwhile, the legitimacy of the medical model of disability is seemingly underscored by USCIS agents’ claim to the ‘diagnostic gaze’ (Samuels Citation2014, p. 132). Ultimately, this exceptional procedure renders violence both elsewhere and interred within the refugee subject.

Bringing disability studies and critical refugee studies together enhances intersectional approaches to refugee studies. By showing how certain discourses and practices traverse refugee and disability administration (in each case working to cast doubt on the validity of claims and the worthiness of people), we make evident how the exceptionalization of refugees and disability interlock. For Sami Schalk and Jina B. Kim, intersectional analyses in feminist-of-colour disability studies demonstrate how intersecting systems work, ‘particularly as they assign value or lack thereof to certain bodyminds’ (Schalk and Kim Citation2020, p. 38). As we have suggested, how states enable and constrain social reproduction is a feminist refugee studies issue. Furthermore, an intersectional approach to disability and refugees shows how state practices delimit these categories and in the process sustain legal limbo for all applicants, and dispossession and disability for those who are most vulnerable. This intersectional analysis can and should be deepened by further attention to how positions that refugees occupy (gendered, racialised, heteronormative) intersect in resettlement and naturalisation processes. For example, the demand for a consistent and unchanging story embeds an assumption that is both ableist and masculinist: that the ‘truth’ of a life is the matter of an autonomous individual, floating free from the entanglement of context and social relations (Walker Citation2002). Further, the lack of recognition of how difficult and traumatising it can be to speak of sexual violence in particular reflects gendered assumptions (regarding violence and sexuality) embedded in the protocols and practices associated with naturalisation. And as our discussion of how Trump-era policies ratcheted up fantasies of fakery with regard to refugees suggests, racism and Islamophobia are implicated in these processes through which refugees are accepted or denied naturalisation. In short, bringing disability studies together with critical refugee studies contributes to a recognition of how multiple relations of power are at work in practices of refuge, resettlement, and citizenship.

Finally, the folding of scrutiny at time of asylum onto scrutiny at time of naturalisation underscores the contention from feminist geopolitics and critical refugee studies that war stretches beyond declared times and zones of war. We show how the naturalisation process for refugees stretches war beyond a conflict zone or its recounting at time of asylum, and into medical and USCIS spaces for naturalisation, years later. In reinvoking difficult pasts and seeming to disallow lives to change while in the US, USCIS agents reassert the war/peace divide. Building on Espiritu’s concept of militarised refuge, we suggest that this invocation of wartime pasts by USCIS agents also militarises refuge, insistently tying refugees to that time of their lives and affixing violence over there. Ablenationalism, it can be said, sustains militarism while undermining meaningful terms of refuge.

Acknowledgements

The authors are deeply grateful to Banu Gökariksel and the Feminist Refugee Geographies Workshop Group that helped bring this article into being. For these ongoing discussions, we extend our gratitude to Betül Aykaç, Emanuela Borzacchiello, Christopher Courtheyn, Alicia Danze, Caroline Faria, Shae Frydenlund, Valentina Glockner, Sameera Ibrahim, Suad Jabr, Devran Öcay, Adam Saltsman, Nathan Swanson and Rebecca Torres.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. There is overlap between these categories of interviewees. The majority of our 62 U.S.-based research participants worked in refugee administration, service provision, or health and some were themselves from Iraq. These interviewees often shared both professional and personal experiences and reflections. In addition to these interviews with Iraqis and others in the role of service providers, we conducted two focus groups with refugees (composed with help from service providers) and six in-depth individual interviews with refugees. Across these groups, Iraqis we spoke to in the U.S. were from a range of class, religious, and ethnic backgrounds, with the majority being Arab and Muslim.

2. Disability in the process of naturalisation did not come up in our interviews with Iraqis whom we asked to reflect on their own resettlement experience. This is not a significant finding but more likely the outcome of the kinds of questions we asked in these interviews and the fact that some had not yet been through the naturalisation process. Therefore, this article draws on our interviews with service providers and their discussions of the N-648 form and their experiences working with clients from a range of backgrounds in the process of naturalisation.

3. The CRPD came into force while the US was at war with Iraq under George W. Bush’s leadership. Barack Obama later signed the Convention, but Congress has not ratified it.

4. The same report cites DHS officials who claim that ‘fraud and “doctor shopping” are both significant concerns within the N-648 process’ (USCIS Citation2020, 21). These assertions were offered as fact; no statistical evidence or other forms of verification were provided.

5. Thank you to Stepha Velednitsky for this observation during the 2022 AAG meeting.

6. On wartime rape as ‘a fundamental way of abandoning subjects’ see (Diken and Laustsen Citation2005).

7. There is no end of literature in the field of psychology that could be cited to corroborate the claim that life stories are mutable. For an introduction to the field of narrative psychology, see (Crossley Citation2000). For a classic psychoanalytical treatment, see (Schafer Citation1992). For a discussion of narrative and suspicion within asylum processes, see Bohmer and Shuman, 2018, (Crock, Ernst, and McCallum Citation2013), Shuman and Bohmer Citation2021.

8. In their practice advisory for attorneys, ILRC suggests, ‘Detailed answers from the medical provider will reduce the risk that the USCIS officer will try substituting their opinion’ (Citation2019, 5).

References

- Andrews, B., C. R. Brewin, R. Philpott, and L. Stewart. 2007. Delayed-onset posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of the evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry 164 (9):1319–26. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091491.

- Arendt, H. 1973 [1951]. The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Barnes, C. 2020. Understanding the social model of disability: Past, present and future. In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, ed. N. Watson and S. Vehmas, pp. 14–31. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Batra Kashyap, M. 2021. Toward a race-conscious critique of mental health-related exclusionary immigration laws. Michigan Journal of Race & Law 26 (26.0):87–111. doi:10.36643/mjrl.26.sp.toward.

- Baynton, D. C. 2016. Defectives in the land: Disability and Immigration in the Age of Eugenics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Berghs, M. 2014. The new humanitarianism: Neoliberalism, poverty and the creation of disability. In Disability, human rights, and the limits of humanitarianism, ed. M. Gill and C. J. Schlund-Vials, pp. 27–44. New York: Routledge.

- Bohmer, C., and A. Shuman. 2018. Political asylum deceptions: The culture of suspicion. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Bonet, S. W., and A. Taylor. 2020. “I have an idea!”: A disabled refugee’s curriculum of navigation for resettlement policy and practice. Curriculum Inquiry 50 (3):242–61. doi:10.1080/03626784.2020.1834332.

- Burdick, L. (2022). New form N-648 and policy guidance on disability waivers. CLINIC. Available from: https://cliniclegal.org/resources/new-form-n-648-and-policy-guidance-disability-waivers.

- Burns, N. 2017. The human right to health: Exploring disability, migration and health. Disability & Society 32 (10):1463–84. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1358604.

- Burns, N. 2020. Boundary maintenance: Exploring the intersections of disability and migration. In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, ed. N. Watson and S. Vehmas, pp. 305–20. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Capps, R., and C. Echeverría-Estrada. 2020. A rockier road to US citizenship?: Findings of a survey on changing naturalization procedures. Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/changing-uscis-naturalization-procedures.

- Card, C. 1996. Rape as a weapon of war. Hypatia 11 (4):5–18. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1996.tb01031.x.

- Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLINIC). (2019). Re. Public comments on agency information collection activities. Available at: https://immpolicytracking.org/policies/uscis-proposes-revisions-n-648-medical-certification-disability-exceptions/#/tab-policy-documents.

- Chatzky, E. B. 2020. Almost citizens: How the medical exception continues to limit refugee naturalization. Elon Law Review 12:137.

- Chouinard, V. 1997. Guest editorials: Making space for disabling differences; challenging ableist geographies. Environment and Planning D, Society & Space 15:379–90.

- City of New York, Office of the Mayor. (2019). Re. Public comments on agency collection activities. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/comment-uscis-rule-n648-natz-uscis-docket-no-2008-0021.pdf.

- Clare, E. 2017. Brilliant imperfection: Grappling with cure. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Crock, M., C. Ernst, and R. McCallum. 2013. Where disability and displacement intersect: Asylum seekers and refugees with disabilities. International Journal of Refugee Law 24 (4):735–64. doi:10.1093/ijrl/ees049.

- Crooks, V. A., M. L. Dorn, and R. D. Wilton. 2008. Emerging scholarship in the geographies of disability. Health & Place 14 (4):883–88. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.013.

- Crossley, M. 2000. Introducing narrative psychology: Self, trauma and the construction of meaning. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Diken, B., and C. B. Laustsen. 2005. Becoming abject: Rape as a weapon of war. Body & Society 11 (1):111–28. doi:10.1177/1357034X05049853.

- Dorn, M. L., and C. C. Keirns. 2010. Disability, health and citizenship. In The SAGE handbook of social geographies, ed. S. J. Smith, R. Pain, S. A. Marston, and J. P. Jones III, pp. 99–117. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Dyck, I. 2010. Geographies of disability: Reflections on new body knowledges. In Towards enabling geographies: ‘Disabled’bodies and minds in society and space, ed. E. Hall, pp. 253–63. New York: Routledge.

- Ehrkamp, P., J. M. Loyd, and A. J. Secor. 2022. Trauma as displacement: Observations from refugee resettlement. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112 (3):715–22. doi:10.1080/24694452.2021.1956296.

- Erevelles, N. 2002. (Im)material citizens: Cognitive disability, race, and the politics of citizenship. Disability, Culture and Education 1 (1):5–25.

- Erevelles, N. 2011. Disability and difference in global contexts: Enabling a transformative body politic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Espiritu, Y. L. 2014. Body counts: The VIetnam War and militarized refugees. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Espiritu, Y. L. 2021. Introduction: Critical refugee studies and Asian American studies. Amerasia Journal 47 (1):2–7. doi:10.1080/00447471.2021.1989263.

- Espiritu, Y. L., and L. Duong. 2018. Feminist refugee epistemology: Reading displacement in Vietnamese and Syrian refugee art. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 43 (3):587–615. doi:10.1086/695300.

- Fekete, L. 2001. The emergence of xeno-racism. Race & Class 43 (2):23–40. doi:10.1177/0306396801432003.

- Foucault, M. 1995 [1977]. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books.

- Freud, S., and J. Breuer. 2000 [1955/1893]. Studies in Hysteria. Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. J. Strachey, Vol. II. New York: Basic Books.

- Gangsei, D., and A. C. Deutsch. 2007. Psychological evaluation of asylum seekers as a therapeutic process. Torture: Quarterly Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture 17 (2):79–87.

- Gill, M., and C. J. Schlund-Vials. 2014. Protesting the ‘hardest hit’: Disability activism and the limits of human rights and humanitarianism. In Disability, human rights, and the limits of humanitarianism, ed. M. Gill and C. J. Schlund-Vials, pp. 1–14. New York: Routledge.

- Grech, S., and M. Pisani. 2022. Disability and forced migration: Critical connections and the global South debate. In Disability law and human rights: Theory and policy, ed. F. Felder, L. Davy, and R. Kayess, pp. 199–220. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harris, J. (2003). 'All doors are closed to us': A social model analysis of the experiences of disabled refugees and asylum seekers in Britain. Disability & Society 18 (4):395–410.

- Immigrant Legal Resource Center. (2019). Assisting applicants who have disabilities by using form N-648. Available from: https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/n-648_practice_advisory_part_2_september_2019.pdf.

- Immigration Policy Tracking Project. (2022). 1,059 Trump-era immigration policies (and their current status). Available from: https://immpolicytracking.org/home/.

- Jacobsen, M. H. 2022. Wars in refuge: Locating Syrians’ intimate knowledges of violence across time and space. Political Geography 92:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102488.

- Kirby, P. 2020. Battle scars: Wonder woman, aesthetic geopolitics and disfigurement in Hollywood film. Geopolitics 25 (4):916–36. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1510389.

- Loue, S., and C. Nunez. 2017. Illness, inadmissibility, waivers, and other health-related issues. In The waivers book. I. Scharf, ed., et al. 2nd edn, pp. 253–87. Washington, D.C.: American Immigration Lawyers Association.

- Loyd, J. M., P. Ehrkamp, and A. J. Secor. 2018. A geopolitics of trauma: Refugee administration and protracted uncertainty in Turkey. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 43 (3):377–89. doi:10.1111/tran.12234.

- Loyd, J. M., E. Mitchell-Eaton, and A. Mountz. 2016. The militarization of islands and migration: Tracing human mobility through US bases in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Political Geography 53:65–75. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2015.11.006.

- Loyd, J. M., and A. Mountz. 2018. Boats, borders, and bases: Race, the cold war, and the rise of migration detention in the United States. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Luibhéid, E. 2002. Entry denied: Controlling sexuality at the border. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lyons, J. 1999. Mentally disabled citizenship applicants and the meaningful oath requirement for naturalization. California Law Review 87 (4):1017. doi:10.2307/3481023.

- McRuer, R. 2018. Crip times: Disability, globalization, and resistance. New York: New York University Press.

- Meekosha, H. 2011. Decolonising disability: Thinking and acting globally. Disability & Society 26 (6):667–82. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.602860.

- Meekosha, H., and K. Soldatic. 2011. Human rights and the global South: The case of disability. Third World Quarterly 32 (8):1383–97. doi:10.1080/01436597.2011.614800.

- Meyers, R. S. 2020. Conducting psychological assessments for U.S. immigration cases. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Mirza, M. 2010. Resettlement for disabled refugees. Forced Migration Review 35:30–31.

- Mirza, M. 2011. Disability and cross-border mobility: Comparing resettlement experiences of Cambodian and Somali refugees with disabilities. Disability & Society 26 (5):521–35. doi:10.1080/09687599.2011.589188.

- Mirza, M. 2014a. Disability and forced migration. In The Oxford handbook of refugee & forced migration studies, ed. E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, G. Loescher, K. Long, and N. Sigona, pp. 420–32. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mirza, M. 2014b. Refugee camps, asylum detention, and the geopolitics of transnational migration: Disability and its intersections with humanitarian confinement. In Disability incarcerated: Imprisonment and disability in the United States and Canada, ed. L. Ben-Moshe, C. Chapman, and A. C. Carey, pp. 217–36. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mirza, M., and A. W. Heinemann. 2012. Service needs and service gaps among refugees with disabilities resettled in the United States. Disability and Rehabilitation 34 (7):542–52. doi:10.3109/09638288.2011.611211.

- Mitchell, D., and S. L. Snyder. 2000. Minority Model: From liberal to neoliberal futures of disability. In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, ed. N. Watson and S. Vehmas, pp. 45–54. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Mitchell, D. T., and S. L. Snyder. 2015. The biopolitics of disability: Neoliberalism, ablenationalism, and peripheral embodiment. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.