ABSTRACT

In recent years, labour in fisheries has emerged as a field of study, gaining traction both from academics and through policy implementations. Fish workers often migrate across jurisdictional borders to work on industrial fishing boats around the world. I argue that research on labour in fisheries would benefit from the inclusion of concepts found within migration studies that can unpack the implications of being a migrant in a host country. In this paper, I borrow the concepts of ‘regularisation’ and ‘migrant agency’ from migration studies to examine how migrant fish workers navigate migration regimes in order to work in the offshore fishing industry. I illustrate my argument through a case of Burmese fish workers in the border city of Ranong, Thailand. Methodologically, I focus on three disruptions to Thai fisheries – labour regulatory reforms, the pandemic, and the recent military coup in Myanmar, in 2021—as open moments to explore ways in which Burmese migrant fish workers navigate their livelihood strategies. Regularisation highlights the trade-off between the benefits and the costs for migrant fish workers of gaining legal status during the disruptions. The concept of migrant agency provides a lens through which to capture how migrants explored the space of possibilities through the cultivation of ethnicity and digital technology during the disruptions. I conclude that theoretically drawing on concepts found within migration studies has the potential to reveal the complexity of migrant fish workers, who exercise their agency, rather than being understood as mere victims in the unruly nature of ocean governance.

Introduction

It is generally acknowledged that fish workers work in one of the most dangerous workplaces in the world. The challenges of regulating and improving working conditions on offshore fishing vessels are twofold. First, fish work takes place at sea, which makes it difficult to monitor conditions that include long irregular working hours with short-term rest, hazardous weather conditions, and unsafe equipment (Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2021). Second, fish workers are often migrants, taking jobs that others do not want (Marschke, Vandergeest, et al. Citation2020). Labour in fisheries became a global concern, sparking academic and public interest, a decade ago when modern slavery scandals in fisheries were exposed in S. E. Asia (McDowell et al. Citation2015), which triggered further investigations globally (Lawrence and McSweeney Citation2018). More recently, similar stories emerged when the investigative journalist Ian Urbina published two powerful stories: ‘The crimes behind the seafood you eat’ and ‘The Uyghurs forced to process the world’s fish’ in The New Yorker magazine in October 2023. These two investigations link forced labour of international migrants and Uyghur workers on Chinese fishing vessels to seafood processing factories and global seafood retailers and supermarkets (Urbina, Citation2023). The quest to understand how labour abuses occur across global fisheries drives scholars to explore diverse concepts and theoretical endeavours to comprehend the complexities of ‘labour in fisheries’, an emerging field of study that requires more attention.

In addressing the challenges of labour in fisheries, scholars working in the fields of research governance (Tickler et al. Citation2018), business and management studies (Wilhelm et al. Citation2020), labour studies (Sparks et al. Citation2022), and critical geography (Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2020, Yea et al. Citation2022) have situated fish workers within broader institutional structures of labour and the environment and seafood commodity chains. However, such research fails to contextualise labour as migrants, who unavoidably need to navigate complex institutional, geographical, and social boundaries when moving to a new country. That is, the migrant fish workers’ awareness of their limited labour rights, and their willingness to demand these rights, is significantly circumscribed by complex and confusing immigration policies, written in languages they do not necessarily speak or understand, all of which renders migrant workers vulnerable to employers’ whims and retribution. Intricate immigration policies have the potential to reinforce precarious lives and work and/or to enable the ability of workers to voice their demands individually and collectively.

To capture how migrant fish workers navigate the transnational migratory spaces they find themselves in, contemporary migration scholars have begun exploring labour in fisheries using migration concepts and theories, situated within the interdisciplinary field of migration studies. For instance, Le (Citation2022b, Citation2022c) has explored the homeland processes that provide (informal) migrant networks and feelings of ‘home’ for Vietnamese migrant fish workers on distance fishing vessels. In a way, homeland processes are tied to why workers decide to sell their labour at sea and how they reorient themselves to work and workplace. Yea et al. (Citation2022) use funnels as a metaphor for shirking decision-making and the control over migrant fishworkers’ own agency. Their example of Filipino migrant fish workers on distant Taiwanese vessels pays attention to the trajectory of deployment, wherein workers’ choices of continuing their journey are narrowed/diluted at each transit point along the migratory route. The processes of unfreedom and human trafficking are then understood as a ‘relational unfolding of constrained choices across time and space in multiple sites’ (Yea et al. Citation2022, 4). The implications of being a migrant within fisheries are the next conceptual venture in labour in fisheries. This paper takes a step in this direction by exploring migration concepts that offer insights into migrants’ agency and what it means to be a migrant in the context of offshore fisheries.

Thailand’s importance as a hotspot of policy interventions and an academic study site for labour in fisheries is well documented (Kadfak and Widengård Citation2022, Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2021, Wilhelm et al. Citation2020). In Thailand, the modern-slavery scandal resulted in major fisheries and labour reforms through a revision of regulations, stricter implementation of existing laws, and the documentation and tracking of fishing vessels and fish workers (Kadfak and Linke Citation2021, Vandergeest Citation2018). In the aftermath of major regulatory reforms brought about by pressure from international media and market actors (Kadfak and Widengård Citation2022), fish workers experienced a shift from working in what was apparently a lawless space to being members of the most surveilled and regulated sector for migrant workers.

While the major legal changes to fisheries and labour reform had seemingly stabilised by early 2019 (Kadfak and Linke Citation2021), the subsequent pandemic and political unrest in Myanmar caused new disruptions, creating uncertainties for Burmese fish workers who had to decide whether to continue working in Thailand or to leave. COVID-19 introduced new restrictions on geographical mobility within Thailand and along immigration routes, further intensifying the movement of fish workers and surveillance policies previously introduced by the fisheries and labour reforms. As well, the military coup in Myanmar introduced a new and major phase of out-migration from Myanmar to Thailand, while those who were already in Thailand looked for new ways to stay, as they saw no future in returning to Myanmar. Political turmoil forced a pause in the formal emigration route, forcing fish workers to move beyond formal organisations and to rely on their personal relations, such as online communications and support networks, to navigate their precarious lives and work.

Methodologically, I use these three key disruptions – new Thai regulatory reforms, the pandemic, and the recent Myanmar military coup – as open moments that ‘provide a lens to examine the reconfigured lifeways of low-wage migrant workers’ (Suhardiman et al. Citation2021, 91). Instead of focusing these open moments as ruptures and drastic changes, I will explore the moments of uncertainty that led migrants to action and change (Stiernström and Arora-Jonsson Citation2022). These moments reveal the migration challenges – including the shift of migration regime from unregulated to regulated, requiring migrants to earn legal status if they were to continue working in the industry – and the structural instability of short-term migration policies regarding COVID-19 and the political turmoil in Myanmar.

This paper starts by taking stock of current approaches to studying labour in fisheries, then expands the conceptual boundaries of the field by discussing two concepts within migration studies: regularisation and migrant agency. These two concepts will provide analytical approaches to making sense of how Burmese fish workers navigated these disruptions in Ranong, Thailand’s border city to Myanmar. Data collection and the research site of Ranong are described in the methods section. The results are organised in a chronology of three open moments. The discussion and conclusion sections point towards the benefits that studies of labour in fisheries would derive from engaging with migration literature.

Current Approaches to Labour in Fisheries

Academic work and ‘grey’ scientific literature on labour in fisheries have conceptually viewed the problem from four broad strands. Resource-governance scholars have highlighted correlations between increased labour exploitation and marine resource depletion (Kittinger et al. Citation2017, Nakamura et al. Citation2018, Tickler et al. Citation2018). Such labour rights violations are often discussed in association with illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and fisheries crimes (Kadfak and Linke Citation2021, Stringer and Harré Citation2019). This debate aligns with the growing interest in research on the intersections between labour exploitation, climate change, and environmental degradation (Brown et al. Citation2019, Le Citation2022b).

Business-and-supply-chain scholars investigate labour violations as a failure of market mechanisms to include labour rights in supply chains’ accountability (Stringer, Burmester, and Michailova Citation2022, Wilhelm et al. Citation2020). The term ‘modern slavery’ has done damage to firms’ reputations, which has, in turn, provoked a rapid response to the problem (Nolan and Bott Citation2018, Wilhelm et al. Citation2020). Clark and Longo (Citation2022) argue convincingly that labour exploitation within the Thai fishing industry is a result of competitive markets and a stressed marine ecosystem. Their take on global labour value chains (GLVC) connects the economic worthlessness of trash-fish and low-value seafood to the unskilled, undesirable, and low-value labour within the agri-food system. Such an analysis situates Thailand as holding a precarious political-economic position within global seafood commodity chains (Clark and Longo Citation2022, 19).

Critical-labour scholars have further explored labour exploitation using free/unfree and human trafficking approaches. Such free/unfree labourer bodies and movement occur throughout labour mobility routes from countries of origin to destinations and far out at sea (Stringer, Burmester and Michailova Citation2022, Stringer et al. Citation2016, Yea et al. Citation2022). The pressure to eradicate human trafficking and unfree labour is placed on states from which vessels are owned or flagged through actions such as downgrades in the annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports and blocking imports of seafood products from sources designated as using forced labour (EJF Citation2015).

Slavery, trafficking, and forced labour concepts come under scrutiny by critical human geographers as these concepts fail to take into account the characteristics and course of poor working conditions and how displacement and poverty force people to sell their labour in the first place (Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2020, Yea Citation2022). Within this strand, scholars have instead focused on exploring voluntary guidelines, regulations, and governing mechanisms to support and improve working conditions of fish workers on fishing boats (Sparks et al. Citation2022). Such work starts to pay attention to socio-political and economic conditions in relation to migration status, and begins to unpack workers’ aspirations to migrate, collective actions, recruitment, wages and contracts, and everyday working conditions on fishing vessels (Chantavanich, Laodumrongchai, and Stringer Citation2016, Kadfak and Widengård Citation2022, Le Citation2022c, Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2021, Vandergeest et al. Citation2021, Yen and Liuhuang Citation2021). However, these four stands of labour in fisheries have not intentionally centred fish workers within a broader migration regime in the receiving country, and have ignored the implications of migrant agency within the neoliberal policy and economy backdrop in which they live in.

Regularization and Migrant Agency in Migration Regimes

The migration regime of labour in fisheries is in need of theorisation. In this section, I foreground the concepts of regularisation and migrant agency, borrowed from the broad field of migration studies, to explore my case. I am aware that these two concepts are small drops in a pool of useful conceptual lenses that migration studies have to offer. However, these two concepts offer the potential to rethink migrant fish workers’ position, by moving away from the dominant narrative of victim or vulnerable group, due to the unfree labour structure within fisheries resource governance, to autonomous agents that lead to social and political transformations (Nyers Citation2015).

Regularisation concerns the question of whether or not legal status provides social support for migrant workers. This body of literature highlights the double-edged nature of regularisation. Becoming documented/formal or regular workers, in some cases, provides workers with social welfare, e.g. basic health care and education, unemployment benefits, and the possibility of gaining legal supports, reduced threats from employers to deportation and wage exploitation, regular payment, safer migration route etc (Bylander Citation2022, Franck and Anderson Citation2019).

There are, however, many downsides of regularisation as well. Considering the work of migration scholars working in S.E. Asia, many have agreed that legal status does not necessarily offer protection and rights, nor empower migrants and improve precarious work (Bylander Citation2021, Derks Citation2010), and often does not come cheap. Franck and Anderson (Citation2019) show, via the example of Burmese migrants in Malaysia, how they experience legal status as something not fixed. Instead, migrants ‘strategically move between legal and illegal status in order both to protect themselves from violence and maintain their livelihood’ (ibid 33). Migrants, therefore, need to calculate the trade-off between being legal or documented migrants, which comes with high costs and often immobility, or being illegal, with the risk of losing their jobs and needing to return home.

Apart from the additional control by host country governments, migrants have to pay high fees to formal brokers and recruitment agencies, with regular renewal of short-term working permits (Anderson Citation2021, Le Citation2022a, Molland Citation2022). Migrants become even more dependent on employers and lack job mobility once they become documented (Bylander Citation2022). A constant calculation of the costs and benefits of having legal status, therefore, becomes part of migrants’ everyday decision-making (Franck and Anderson Citation2019). Such a calculation is associated essentially with their ability to be mobile. Regulatory regimes could potentially create hyper-dependence between employer and migrant, and lead to less safety for regular migrants (Bylander Citation2019).

Being legal or illegal may mean different things for different migrants; a more important question is how migrants, individually and collectively, plan their strategies to navigate regulatory migration regimes. This question can be understood through the concept of migrant agency. While it is important to point out within the fragmented literature on migrant agency – spanning across approaches including political belonging within citizenship debates, resistance and transgression, autonomous migration and choices of individuals (Mainwaring Citation2016) – I find the definition by Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998, 970) most useful for my case. The authors refer to human agency as a ‘temporally embedded engagement by actors of different structural environments – the temporal-relational contexts of action – which through the interplay of habit, imagination, and judgment, both reproduces and transforms those structures in interactive response to the problems posed by changing historical situations’. Therefore, the focus of migrant agency is to comprehend how migrants enact, co-opt and perform their agency against contested border community, host society’s norm or the host regulatory governing regime (Borrelli et al. Citation2022). That is, even within strict regulatory migration regimes, where migrants are often being pushed to the edge of society, migrants continue to make decisions by craving out tactics within their narrow margin of social space and finding room for negotiation in their everyday lives (Mainwaring Citation2016).

Migrants perform agency and employ several tactics of resistance and navigation. For instance, migrants engage in reactive ethnicity, such as the ways in which migrants use ‘ethnic resources, solidarity and symbols to survive in a situation of exclusion and disadvantage’ (Castles Citation2003, 17). Strengthening identity and ethnicity as part of place making among migrants leads to enclave communities. As Seo and Skelton (Citation2017) illustrate convincingly through their ethnographic work of Nepal Town in South Korea, that space of migrants’ agency is practiced in their coming together in public space, speaking Nepali, eating Nepali food, and sharing leisure time. Nepal town then becomes a ‘space of possibility’ for Nepalese migrants to resist the oppressive regulatory migration regime and have freedom to be Nepalese.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) is another tactic co-opted by migrants to respond to changes. I approach ICTs as an empowering tool for migrants to integrate processes and reduce their precarity at work (Molland Citation2021), to stay connected with families and their wider networks (Kelly and Lusis Citation2006), as well as to seek immediate support for forced and trafficked migrants (Marschke, Andrachuk, et al. Citation2020). Increasing usage of digital platforms and smartphones among migrants around the world leads us to pose questions about migrants’ capacity to take advantage of digital technologies to navigate regulatory migration regimes. Digital technologies take on a ‘mediating role’ in migration processes, which have enhanced migrants’ agency (Nedelcu and Soysüren Citation2022). Molland’s (Citation2021) research on the use of social media, i.e. Facebook among Burmese migrants, to navigate ‘safe migration’ in Thailand shows the scalability of potential migrant assistance and pseudo union activities on digital space. Social media, in his example, provides migrants with easy access to rich and updated information of migration regulatory regimes, to connect with other migrants who are encountering similar problems, and to contest the policies of the Thai government.

Context and Methods

The regularisation of fisheries and labour, which resulted from the modern slavery scandal (Kadfak and Widengård Citation2022), was layered on top of Thailand’s already complex migration regime. According to excellent conceptual work by Bylander (Citation2019), Thailand’s migration regime displays four distinct characteristics: robust and well-established migrant networks in the region, the persistence of an amnesty programme for irregular migrants, the distinction between migrants, registered through Memorandum of Understanding, and irregular migrants, and the poor regulation of formal recruitment. The majority of migrants cross borders via informal movement to Thailand, relying on strong and extensive informal knowledge sharing among well-developed migrant networks (Bylander Citation2019, Molland Citation2022). This is true of migrant fish workers, who make up a majority of fish workers in Thailand’s fishing industry. Burmese migrants are approximately 70% of the workforce in the fishing industry, and among those are the ‘superworkers’ who move back and forth between Thailand and Myanmar, involved in 3Ds work (dirty, dangerous and difficult) (Ra and Franco Citation2020).

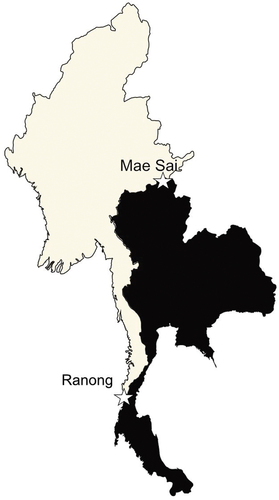

To capture migrants’ perceptions and navigations of the three disruptions, I zoom into migrant fish workers based in Ranong, a city that borders Myanmar (see in Map 1). Through Ranong, migrants take this route to southern Thailand and further to Malaysia and Singapore. Ranong is economically dominated by commercial fishing, with an estimated 413 vessels (DoF Citation2021). With a population of around 175,000 people, Ranong has been hosting approximately 50,000 Burmese migrant workers. This paper is based on analyses from multiple methods, including interviews, fieldnotes, and online content analysis and has been a joint effort between the author and a trained research assistant, who lives in Ranong.Footnote1

(Insert Map 1: Map of Ranong, the border-crossing channels between Myanmar and Thailand)

The primary data for this paper comes from two sources: fieldnotes and interviews. First, fieldnotes were produced through observation during two visits to Ranong, pre- and post-pandemic, between March – April 2020 and November – December 2022, and a short visit to Yangon, Myanmar, during March 2020. Second, we conducted interviews with two groups of experts and Burmese fish workers (hereafter the informants). We conducted semi-structured interviews with 11 experts, including Thai and Burmese NGO officers working on labour, a Burmese recruiter, fisheries associations, and Thai government officers, boat owners, two focus group discussions with boat owners (see appendix A). We also conducted 39 semi-structured interviews with Burmese migrant fish workers working in Ranong and four Burmese fish workers working in Myanmar, between October 2020 to April 2022 (see appendix B on age, number of years in Thailand, and date and location of the interview).

To complement our primary data, we gathered online news articles and Facebook pages as our secondary data. First, 200 COVID-19 news articles were collected between 2020–2021. The research assistant wrote detailed fieldnotes between March 2021 and August 2022, describing the assistant’s own experiences of living through the lockdown in Ranong. In addition, the research assistant took fieldnotes on the emerging issues among the migrant community in Ranong, which provided me with significant insights into challenges that I could not experience due to travel limitations. Second, using the snowball-sampling technique, we explored 83 public and private Facebook pages of NGOs, recruitment services, labour and youth associations, news, language learning that were accessed by Burmese migrant workers in Thailand between September 2020 and February 2021. The majority of the communications in these pages is done in Burmese.

Burmese Fish Workers Navigate the Three Disruptions

In this section, I explore the three key disruptions – fisheries and labour reforms, Covid-19, and the military coup in Myanmar – to understand how migrant fish workers navigated these disruptions and how they navigated ways to secure their legal status to continue their livelihoods, gain basic rights, and work towards improved working conditions.

First Moment: Fisheries and Labour Reforms (2015–2019)

Fish workers went from being members of an outlaw sector to members of the most regulated sector for migrant workers in Thailand as a result of the reforms. The reforms started in 2015, when the EU issued Thailand an IUU yellow card, which triggered two major reforms in fisheries and labour, in relation to migrant workers in the industry (See in details in Kadfak and Linke Citation2021). In particular, the reforms introduced two traceability systems, one addressing the movement of fishing vessels and another the movement of fish workers. The labour traceability system has increased visibility and state presence through documentation, inspection, and infrastructure processes. In addition to all the documents that confer legal status and the right to work for migrant workers in other sectors, since the reforms all fish workers are required to apply for a seabook, equivalent to a seafarer identity card, before they are allowed to join any fishing trip. Individual workers, therefore, are being identified pre- and post-fishing trip.

The regulatory migration regime creates a sense of safety and provides an insurance of regular monthly payments for migrant fish workers. With the close-up vessel monitoring system (VMS), Thai fishing vessels are only restricted to exclusive economic zone (EEZ) within 30 days per trip, which has reduced the risk of extreme exploitation. Reports of forced labour and trafficking have been drastically reduced. One fish worker compared his feelings of safety before and after the reforms.

Ten years ago, we used to say that fishers who worked on fishing boats weren’t afraid to die. It was the most dangerous job you could imagine … There was no card needed back then, and it wasn’t as difficult as it is now. Anyone who wanted to work on a boat could do it. Nowadays, you need a card and all the documents in order to work on a boat. Because before leaving for a fishing trip, PIPO (port-in port-out authority) will come to check the card and take photos of the crew, and make sure that we get back. (no. 29)

Moreover, during the reforms Thai and international NGOs have received funding from international donors to put resources into grievance and forced labour detection activities (Kadfak et al. Citation2023). This includes a hotline phone operation and group-chats on communication applications, such as Line and WhatsApp. The research assistant has been working part-time with an international NGO providing translation support for a Line Application group-chat. He mentioned that these group chats operate via ‘word of mouth’. The NGO he works with has set up various group chats titled ‘Leaning Thai language’ or ‘Family support’ to avoid employers’ investigation into the content inside the chat room. Fish workers can report cases of rights violations directly to the NGO’s officers.

Regularisation, however, comes at a price. The cost of documentation has increased. According to our interviews, fish workers, or their employers, depending of the arrangement, need to pay between 10,000–20,000 THB (300–600 USD) every two years for their work permit, visa, and health insurance. An additional administrative service is added in for a document broker to help navigate the new migration policy. We talked to some workers who have to bear the cost of documentation through salary deductions. Regularisation also ties fish workers to employers in ways that make it harder for fish workers to move to new employers when they are not happy or face poor work situations. Some workers have also become dependent on employers for obtaining, paying for, and holding their documents. The new regulations allow for only a short unemployment period before finding a new employer. Workers, then, become dependent on their employers for keeping track of documentations, or what I refer to as ‘document bondage’. These findings align with the recent report produced by Human Rights and Development Foundation (HRDF) on wage deductions and document detention among migrants in fisheries (HRDF Citation2023). In other words, regularisation has the potential to produce unfreedoms – ‘limiting the potential of migrants to exert basic rights to enter and exit employment’ (Bylander Citation2022, 4).

The intensification of tracking and surveillance in fisheries, as a result of human/labour rights concerns over ethical supply chain products, increased pressure on boat owners and operators as actors accountable for workers’ welfare. To continue fishing operations, Thai-flagged vessels need fully legal and documented migrant fish workers on board; otherwise, boat owners face major fines and punishment. One of the boat owners I interviewed reflected on this point, stating that ‘not a single fish worker in Thai waters is undocumented; if PIPO finds out, we would have to pay millions of Thai baht!’. Strict regulation of fisheries and the migration regime provides workers an upper hand when negotiating for a spot on a fishing boat. I met one of largest fishing operators in Phuket who mentioned that ‘we need to change our strategy toward fish workers. We have to give them advance money and good food and alcohol for each fishing trip, otherwise we cannot keep them with us’. He continued, complaining that ‘last month, my boat was ready to go out fishing, we spent more than a million Thai Baht on petrol and ice, planning for 30 days fishing trip, but we were short of workers by a few people. You see, with purse seine fishing, if you are less than certain number of fishing crew, you cannot operate’.

Unlike the seafood processing sector, the fishing industry continues to conduct informal recruitment. Often boat owners ask the heads of the fishing crew, often migrants with the most experience, to return to their home villages to recruit new workers. While these informal recruitment practices have been critiqued by ILO as potentially perpetuating human trafficking, this process portrays the specificity of labour relations of work at sea. This is because work at sea requires cooperation and teamwork. Thus, the head of the fishing crew can exercise his reactive ethnicity to recruit new workers who are part of his social networks in Ranong or back home in Myanmar. This close connection among workers on a fishing vessel allows them to form a loose network within their own unit to resist and negotiate with the captain and boat owners for better working conditions. Sometimes negotiations come down to small issues, such as maintaining a good stock of basic medicines, drinking water, and food and drink on board, which do not require too much investment from employers but which improve the quality of life at sea.

Most of the informants we interviewed confirmed that it is easy to find a job in fishing once you have figured out the documentation processes. For fish workers, there is a trade-off in the of regularisation in fisheries; on the one hand, it has improved safety conditions of work at sea, guaranteed a monthly salary and basic health care, and has reduced extreme abuses; on the other hand, it has not improved the problems of precarious work and has created further dependencies on employers due to the complexity of the documentation process. My case study, thus, aligns with Franck and Anderson’s (Citation2019) argument that both migrants and employers face financial risk, turning legal status into an expensive ‘commodity’. Regularisation makes it expensive, and creates potential risks for workers of falling into a trap of document bondage; at the same time, it creates an opportunity for workers to have an upper hand in deciding to whom they will sell their labour.

Second Moment: COVID-19 (March 2020–Early 2022)

Covid-19, as an open moment, made visible the discrimination policies and practices of government authorities towards migrants (ILO Citation2022, MWG Citation2021), making this open moment crucial to studying migrants’ agency as they navigated the uncertainties. During the pandemic, migrant workers were treated differently in comparison to Thai citizens. All of our informants observed the increased presence of police and PIPO officers visiting the harbour during the lockdown. Landing of fish had become more difficult due to strict regulations regarding wearing masks and checking temperatures. Our observations showed that there was extra control of migrants’ mobility in public spaces via the installation of roadside checkpoints. Almost all informants mentioned the increased identification check-ups and felt that they had become objects of policy harassment. From the fieldnotes and interviews, we know that boat owners often hold workers’ original documents: Certificate of Identity, pink card, and seabook, often without having provided photocopied versions to fish workers. One informant reflected on the COVID-19 inspections and the importance of immigration documents:

The police always came to the port to check fish workers’ documents, because most of the fishing crew did not bring their documents, and some forgot to bring their documents when leaving home. This is a very normal scene for us. The fishing harbour is the police’s livelihood space. During Covid-19, the police came more often to check the documents. If we forgot to bring along the identity documents, the police would ask us ‘did you illegally cross the border from Kawthoung (Myanmar border-city crossing from Ranong)?’ (no. 11)

While the closed border during the pandemic made it difficult for many fish workers to cross back and forth, as they once did, we also observed how migrant workers used social media platforms to overcome restrictions on movement and immigration policy, i.e. obtaining extensions of work permits.

Evidence shows that a large number of migrants travelled to their home countries during the first wave of COVID-19 in March 2020, and have not returned. The seafood industry was deeply impacted by the shortage of workers (Marschke et al. Citation2020, Stride Citation2021). At the beginning of the pandemic, fish production had slowed due to the diminished tourist market and some restrictions on movement. However, seafood exports from Thailand continued to rise in 2020–2021, as the sector was prioritised by the Thai government (ILO Citation2022). With seafood catch and export products continuing to increase, while the fishing workforce was declining, those workers that remained in Thailand employed a ‘wait and see’ livelihood strategy.

Fish workers paid close attention to updates to Thailand’s border policy in relation to COVID-19 quarantine policies before deciding to go home, since they feared they would not be allowed to return to Thailand if the left.Footnote2 The Thai government extended migrant visas several times during Covid-19. Migrant fish workers who were already registered as documented workers were allowed to stay and renew their visas during this period. Almost all of our informants reported following the COVID-19 situation and new immigration policies via their employers and Facebook information pages in Burmese, while a few of them mentioned receiving information from local NGOs. For instance, one informant shared with us that

I read Burmese news on Facebook. I hardly read any COVID-19 news in Thailand because I cannot read Thai. My boss keeps informing me about the new information. For example, we are not supposed to go out after 10 p.m. or we have to wear masks all the time when we go out. (no. 2)

Most of the informants thought positively about the Thai government’s general COVID-19 policy compared to that of the Burmese government, which had limited support for the wider population. They mentioned that even though they received minimal healthcare supports and vaccinations from the public hospital in Ranong, the conditions were much better in Thailand than in Myanmar. This influenced their decision to remain in Thailand.

Moreover, Thailand’s short-term immigration policy during the pandemic collided with the political instability in Myanmar, which forced waves of illegal crossings during the new, often short-term, migrant worker registration programme (MWG Citation2021). Ironically, learning from everyday conversations, local news, and social media, a spike in irregular crossings via the Ranong province border align with the announcement of short-term registration of migrant work-permits. In a way, Burmese migrants calculated their risks and attempted to be physically present in Ranong via different channels, legal and illegal, so that they could apply for work permits and visa extensions. Being a legal or an illegal worker depends on timing and one’s individual agency to find supports, often from paid informal brokers or relatives and friends in Ranong.

Covid-19 is a crucial open moment to test the regulatory reforms. Migrant fish workers continued to live in fear of harassment even though they held legal status. While my case observed discriminatory COVID-19 policies against low-skill migrants, similar to that of other countries in S.E. Asia (Suhardiman et al. Citation2021), legal status and worker shortages in fisheries allowed Burmese workers to experience less pressure to renew working visas, as they felt that they had the right to stay in the country.

Third Moment: Military Coup in Myanmar (February 2021–Present)

In February 2021, in the middle of the pandemic, the Burmese military took over the government in Myanmar, which influenced the long- and short-term plans for migrant fish workers working in Thailand. Since the coup, approximately 1.5 million Burmese have been displaced, while 2.2 million continue working in Thailand and Malaysia (ILO Citation2023).Footnote3 This political crisis landed on top of the already difficult situation facing landless and marginal farm households in Myanmar. As such, migration to Myanmar cities and neighbouring countries has been the main option for many rural Burmese who are otherwise facing unemployment (Belton and Filipski Citation2019). Cross-border movement between Thailand and Myanmar since the military unrest has been dependent upon on the military-government order. By the end of 2022, the Burmese government had implemented a short-travel ban from Ranong (Thailand) into Myanmar to limit the support of anti-military groups from Thailand. Thailand’s continuing pandemic restrictions on movement and limits on physical meetings required fish workers to recreate virtual online spaces to reproduce their social networks.

Political shifts created uncertainty for the near-future livelihood trajectory of millions of Burmese, who tried to flee the country seeking better livelihood possibilities (Kyed Citation2021). The interview period between late 2020 and early 2022 allowed us to explore the changes in fish workers’ perceptions about their future and how COVID-19 and the military coup have changed their ideas about livelihood pathways. When we asked, ‘what is your plan for the near future, e.g. next year?’, and ‘what do you think will happen in Myanmar in terms of job opportunities in coming years?’, answers were clearly divided in two directions – before and after the coup. The majority of the first group of 18 informants, interviewed before the coup, mentioned that they planned to work in Thailand for only a few more years, or until the pandemic situation improved. Ten out of eighteen planned to save up and return to Myanmar to work in fisheries-related occupations. After the coup, however, nine of them believed that the situation would not get better anytime soon, and that they planned to stay in Thailand as long as they could.

The common thread of how fish workers began their journey to Thailand is that they knew someone, either relatives or friends in Thailand or Myanmar. ‘Knowing someone personally’ connects to the issue of trust, which has not improved in terms of trust in the Thai government to solve their problems during the reforms. This point is reflected in our findings; when we asked about the reforms, keywords like ‘safe’, ‘reliable’, and ‘check-up’ were common reflections from the informants, but when we asked, ‘whom do you contact if you experience problems at your work?’ and ‘whom do you contact if you experience problems with your employer?’, the majority of informants direct their answers to employers, their families, and friends; very few mentioned local NGOs or Thai government authorities regarding supports. Migrants have enacted their agency through reactive ethnicity as discussed within migration studies (Castles Citation2003) by connecting to networks with whom they share language and culture.

With this limitation of mobility and opportunity to find interpersonal supports during COVID-19 and the military coup, we observed the growing dependence on digital spaces for social supports among fish workers. According to our semi-structured interviews, the majority of fish workers access Facebook as the main application to update information about recruitment and job seeking, immigration policy, Covid-19, the recent political situation back home, and for communicating with their friends and family at home. Even though fish workers cannot access the Internet at sea, when they can access it, they prefer a one-stop-service online application like Facebook, which provides multiple functions including entertainment, news, personal communication (Facebook messenger), private sub-groups for open discussion, and as a source of information. A few examples from the interviews show how fish workers access new information on ever-changing immigration policy and the COVID-19 situation from Facebook.

The cost of extension is expensive every year, because we need to extend visas, work permits, and health insurance at the same time, which costs 10,000 THB per person. Most of the visa extension information I got from Surachai Mintun Facebook page,Footnote4 and he explains the process of visa extension and other documents information (no. 17).

When the boat returned to shore, I didn’t have time to stop because I had to do some shopping and check the engine to get ready for the next boat trip. If I’m free, I go to my friend’s house. Most of the news I will see on Facebook (no. 26).

According to the interviews, online communication applications like Facebook Messenger, Line, WhatsApp, and Viber have been widely used for direct communication between fish workers and someone they trust to discuss sensitive issues and to ask for support (including Line group-chats, as mention in section 5.1). These applications also benefit from their low cost, compared to international phone calls a decade ago, which thus expands and intensifies migrant social networks in Thailand and at home. At the beginning of the military coup, all four of the Burmese fish workers working in Myanmar used Facebook as a source of information. They mentioned that they used to read and watch news channels such as Democratic Voice of Burma and Eleven Media on Facebook pages, to stay informed about street protests and movement against the military regime.

Learning from the empirics, Facebook is an important online social space that fish workers use to connect to their social networks but also to information on labour rights and immigration policy (Kadfak, Pale, and Wai Yan Citation2021). In our observations across 83 Facebook pages – there are more than 40 million members and followers on these pages (counted by end of February 2021) – we detected themes discussed in these forums including recruitment opportunity, detection of labour rights abuse, facilitating workers’ voices, information sharing on the socio-political situation in Myanmar, discussions on migration regimes, networking, and COVID-19 related issues. However, the most common topics were migration policies and social supports, e.g. visas, work-permit extensions, and health insurance. While these pages allow migrants to share their experiences, find supports, and connect with private service providers who help them navigate the complex and overwhelming information and documentation processes, these forums may also lead to scams.

In this study, we see that the political situation further emphasised the importance of online communication among Burmese migrant workers, since it provides less-filtered information and easy access from Thailand. The networked social space in the digital world has reshaped how fish workers stay connected with friends and family in Myanmar, and how the processes of migration are practiced and navigated. This online social space has made visible the complex narratives of migrant fish workers facing an increasing strict regulatory space, on the one hand, while having the ability to access open social and informal spaces through online forums, on the other hand. Digital technologies, social media in particular, have taken on a ‘mediating role’ in interactive response to this structural political change. The expansion of fish workers’ networks beyond the purely personal was clearly relevant in this case.

Discussion and Conclusion

Labour in fisheries is an emerging field of study that explores the extreme abuses and violations of labour in relation to fishing activities, often caused by workers’ precarity, rooted in their lack of citizenship and inability to implement their rights vis-à-vis boat owners and/or captains (Kadfak and Widengård Citation2022). While this field has enjoyed transdisciplinary attention in recent years, current developments in this field lack a crucial analysis of workers as migrants with agency. This paper attempts to expand the research boundaries of labour in fisheries to include key migration concepts of regularisation and migrant agency to re-centre our attention to notions of being a migrant within fisheries. Using a migration lens shows the emerging dilemmas that fish workers face through their lifeworld of being migrants. It shows that Thailand’s temporary and restrictive immigration policy programme allows the Thai government to ‘import labour but not people’ (Castles Citation2006) in (Palmgren Citation2022, 17). The temporality due to the restricted short-term immigration policies creates uncertainty, so that forming labour unions or carrying out collective actions is very difficult to achieve, and, to date, illegal in the context of Thailand. However, focusing on migrant agency allows us to explore how workers negotiate precariousness for better working conditions and how they can navigate socio-political changes – in particular, in this case study, the three disruptions proposed as methodological venture points.

Three open moments become a useful methodology to critically assess how migrants navigate the changes in order to continue their lives and livelihoods in the host country. The fisheries and labour reforms brought about a major regulatory change, which shifted the industry from an outlaw sector to the most regulated sector within a very short period of time, but with long-term consequences. This reform provided workers with basic rights and a sense of safety from physical violations. However, the reforms come with a high risk of creating document bondage and subjecting workers to control and surveillance by the Thai government. COVID-19 and the military coup further restricted fish workers’ movements and revealed pre-existing marginalisation more visible among migrant fish workers (Marschke et al. Citation2020). The COVID-19 disruption has confirmed the long and unresolved discriminatory migration policy through double-standard implementations, particularly with regards to the mobility of migrants during different phases of restriction. Fish workers navigated the movement restrictions during COVID-19 and future uncertainty caused by political crisis, but migrants have been creating ‘spaces of possibility’ via their access to knowledge and social networks online. ‘Open moment’ as a methodology is, of course, not limited to the three disruptions discussed in this paper. Rather, labour in fisheries could benefit from disruption methodology to explore the uncertainties that workers face with respect to all sorts of socio-political changes. For instance, the increasing restrictions on supply chains governance due to recent due diligence laws by market nations would require a shift in regulatory regime to ensure human and labour rights of upstream workers.

The case of Burmese migrants contributes to the labour in fisheries field in two ways. First, it provides an example of how a regulatory migration regime influences migrants’ livelihood strategies in fisheries. This is because migration status and the processes of applying for legal status affect how workers plan their choice of occupations and influence their decisions to stay or leave the industry completely. Second, this case shows how ethnographic work and long-term engagement in a border city can provide insight to migrants’ agency and their perceptions of change over time. This case does, however, have some limitations regarding generalisation in the field of labour in fisheries. This case has focussed on the informal route of recruitment, which often occurs at land border crossings. Therefore, it does not include in the discussion some key migration recruitment actors, e.g. formal/registered recruiters and labour brokers (see Campbell Citation2018). The roles of actors that support the migration process are important for international migration processes, such as the case of Indonesian and Philippine fish workers on Taiwanese and Chinese fishing vessels (Yea Citation2022, Yea et al. Citation2022) or West African workers in Ireland’s fisheries (Marschke and Vandergeest, Citation2023, Murphy et al. Citation2023). In addition, although I do not highlight the physical boundary of fishing vessels, the Thai case represents only the fishing vessels found within national EEZ waters, unlike the case of international fishing fleets of China and Taiwan. The Thai case does, however, have merit for cases of EEZ fishing, such as those of Ireland or Vietnam, where inspections occur regularly, but fish workers continue to face challenges (Alonso and Marschke Citation2023, Marschke and Vandergeest Citation2023).

Despite being one of the riskiest professions in the world, fish work is not recognised as part of the Marine Labour Convention nor general territorial labour laws (Vandergeest, Marschke and MacDonnell Citation2021) and was only recently included as part of transportation unions at sea (Kadfak et al. Citation2023). The ILO has attempted to improve working conditions through the Work in Fishing Convention, ILO C188, which includes specific sections on working conditions, rendering the responsibility to a skipper/captain’s ‘lawful orders’ to provide fair working conditions (Vandergeest and Marschke Citation2020). With the slow progress of legal support of labour at sea, migrant workers have the alternative route of holder skipper/captain or even boat owner accountable through migration regime. This paper attempts to go beyond the discussion of freedom and unfreedom and to explore how having legal status in a regulatory migration regime can become an asset for migrants endeavouring to claim basic rights, to improve their working conditions, and to claim compensation in the case of abuse or violations. This analysis shares similar conclusions with the recent study by Marschke and Vandergeest (Citation2023), wherein the authors argue for the importance of a regularisation campaign for migrant fish workers in the Irish fishing industry. The legal status of migrant workers on Irish boats allows them to pursue claims of injustice or unfair payment through the court system.

Migrant agency is a useful concept that allows us to understand the reasons behind individuals’ actions when they encounter hardships and/or abuses in fisheries. Some early work on labour in fisheries has already engaged in this concept. This includes the work of Le (Citation2022c) and Yea et al. (Citation2022). Le (Citation2022c) applied the infrapolitics concept, drawing from James Scott, as a form of individual agency and resistance that helped Vietnamese migrant fish workers escape exploitation on Taiwanese fishing boat. Yea et al. (Citation2022) prefer the term liquid agency, to explain how migrants’ agency is shrinking with respect to decision-making and control over their movements further down the trajectory of their migratory route, before arriving at the fishing vessel. In my case, I use concept of agency to make visible the importance of migrants’ calculated choices to continue or enter into a heavily regulated fisheries governance regime, or to leave fisheries altogether. In addition, ICT and digital space can add to our understanding of agency in labour in fisheries. The recent exposé by investigative journalist Ian Urbina showed the powerful ICT techniques used to communicate with fish workers trapped on Chinese fishing vessels and to connect with the workers’ families back home (Urbina Citation2023).

Finally, migration studies is a broad field, equipped with relevant concepts that can make sense of migrants’ perceptions, livelihood trajectories, and choices of migration routes (See Le Citation2022c, Leder Citation2022, Molland Citation2022). In this paper, I borrowed the concepts of ‘regularisation’ and ‘migrant agency’ to offer a more complex picture of fish workers as both active and passive migrant individuals who engage in ongoing strategies to navigate the changes confronting them, as opposed to their being understood as mere victims of an unfair business model. Migration theories and concepts have the potential to expand the theoretical boundaries of labour in fisheries. For instance, one could use the concept of im/mobility to further explore the informed choices underlying migrants’ choices to move to new geographical spaces or to investigate freedom/unfree labour in a broader migration regime (Franck Citation2016). The concept of autonomy in migration studies is another concept we could draw on to explore how migration becomes ‘force that is capable of social and political transformations’ (Nyers Citation2015, 27) for migrant fish workers. Therefore, the notion of ‘being migrant’ should earn the central attention of this emerging field of labour in fisheries.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.6 KB)Acknowledgements

For a useful and critical feedback on an earlier version, I would like to thank Prof. Peter Vandergeest for his kind support. I would also like to thank all the informants who took time to respond to our questions. This research received support from the Swedish Research Council (VR) grant no. 2018–05925 and the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (Formas) grant no. 2019–00451.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2024.2302422

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. I would like to stress the important contribution of the research assistant who collected data in the field, in both the Thai and Burmese languages. We have, however, decided not to include the research assistant’s name in this publication due to vulnerability in the field. Therefore, I use the pronoun ‘we’ in the next sections to recognise these fieldwork contributions.

2. Although there was reported to be a massive flow (nearly 200,000 people) of migrants crossing back to their home countries within the first two weeks of the first wave of COVID-19 (ILO, Citation2022), expecting to be able to return soon after, many workers could not return due to Thailand’s long lockdown policy. However, the Thai government was pressured to bring back fish workers and seafood processing workers, since seafood demand remained high.

3. The number of Burmese migrants in Thailand is unclear, but is predicted to more than 3 million (Ra and Franco, Citation2020).

4. Sarachai Mintun is a public figure who started Myanmar Live – a famous Myanmar news service in Thailand. His personal Facebook page has more than 950K followers, while Myanmar Live has more than 1.5 M followers.

References

- Alonso, G., and M. Marschke. 2023. Blue boats in deep waters: how aspects of IUU policy impact Vietnamese fish workers. Maritime Studies 22 (2):14. doi:10.1007/s40152-023-00303-7.

- Anderson, J. T. 2021. Managing labour migration in Malaysia: Foreign workers and the challenges of ‘control’beyond liberal democracies. Third World Quarterly 42 (1):86–104. doi:10.1080/01436597.2020.1784003.

- Belton, B., and M. Filipski. 2019. Rural transformation in central Myanmar: By how much, and for whom? Journal of Rural Studies 67:166–76. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.02.012.

- Borrelli, L., P. Pinkerton, H. Safouane, A. Jünemann, S. Göttsche, S. Scheel, and C. Oelgemöller. 2022. Agency within mobility: Conceptualising the geopolitics of migration management. Geopolitics 27 (4):1140–67. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1973733.

- Brown, D., D. S. Boyd, K. Brickell, C. D. Ives, N. Natarajan, and L. Parsons. 2019. Modern slavery, environmental degradation and climate change: Fisheries, field, forests and factories. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4 (2):191–207. 2514848619887156 doi:10.1177/2514848619887156.

- Bylander, M. 2019. Is regular migration safer migration? Insights from Thailand. Journal on Migration and Human Security 7 (1):1–18. doi:10.1177/2331502418821855.

- Bylander, M. 2021. The costs of regularization in Southeast Asia. Contexts 20 (1):21–25. doi:10.1177/1536504221997864.

- Bylander, M. 2022. The trade-offs of legal status: Regularization and the production of precarious documents in Southeast Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (13):3434–54. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2147910.

- Campbell, S. 2018. Border capitalism, disrupted. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Castles, S. 2003. Migrant settlement, transnational communities and state strategies in the Asia Pacific region. In Migration in the Asia Pacific, ed. R. Iredale, C. Hawksley, and S. Castles, 3–26. Massachusetts, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Castles, S. 2006. Guestworkers in Europe: A resurrection? The International Migration Review 40 (4):741–66. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00042.x.

- Chantavanich, S., S. Laodumrongchai, and C. Stringer. 2016. Under the shadow: Forced labour among sea fishers in Thailand. Marine Policy 68:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2015.12.015.

- Clark, T. P., and S. B. Longo. 2022. Global labor value chains, commodification, and the socioecological structure of severe exploitation. A case study of the Thai seafood sector. The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (3):652–76. doi:10.1080/03066150.2021.1890041.

- Derks, A. 2010. Migrant labour and the politics of immobilisation: Cambodian fishermen in Thailand. Asian Journal of Social Science 38 (6):915–32. doi:10.1163/156853110X530804.

- DoF. (2021). Thai Fishing Vessels Statistics 2021. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www4.fisheries.go.th/local/file_document/20211224151206_new.pdf

- EJF. (2015). Pirates and slaves: How overfishing in Thailand fuels human trafficking and the plundering of our oceans. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://ejfoundation.org/reports/pirates-and-slaves-how-overfishing-in-thailand-fuels-human-trafficking-and-the-plundering-of-our-oceans

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. What is agency? American Journal of Sociology 103 (4):962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Franck, A. K. 2016. A(nother) geography of fear: Burmese labour migrants in George Town, Malaysia. Urban Studies 53 (15):3206–22. doi:10.1177/0042098015613003.

- Franck, A. K., and J. T. Anderson. 2019. The cost of legality: Navigating labour mobility and exploitation in Malaysia. International Quarterly for Asian Studies 50 (1–2):19–38.

- HRDF, (2023). Wage Deductions of Workers in Fishery Sector. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://hrdfoundation.org/?p=3267.

- ILO. (2022). Rough Seas: The Impact of COVID-19 on Fishing Workers in South-East Asia. Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/asia/events/WCMS_842553/lang–en/index.htm

- ILO. (2023). TRIANGLE in ASEAN Quarterly Briefing Note: Myanmar (January – March 2023). Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/documents/genericdocument/wcms_735107.pdf

- Kadfak, A., and S. Linke. 2021. More than just a carding system: Labour implications of the EU’s illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing policy in Thailand. Marine Policy 127:104445. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104445.

- Kadfak, A., T. Pale, and H. Wai Yan. 2021. Looking for clues: COVID-19 and ‘Facebook Fieldwork’ with cross-border Burmese migrants. Society from Cultural Anthropology. Retrieved February 16, 2023. from https://culanth.org/fieldsights/looking-for-clues-covid-19-and-facebook-fieldwork-with-cross-border-burmese-migrants.

- Kadfak, A., and M. Widengård. 2022. From fish to fishworker traceability in Thai fisheries reform. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 6 (2):1322–42. 25148486221104992 doi:10.1177/25148486221104992.

- Kadfak, A., M. Wilhelm, and P. Oskarsson. 2023. Thai labour NGOs during the ‘Modern Slavery’ reforms: NGO transitions in a Post‐aid world. Development and Change 54 (3):570–600. doi:10.1111/dech.12761.

- Kelly, P., and T. Lusis. 2006. Migration and the transnational habitus: Evidence from Canada and the Philippines. Environment and Planning A 38 (5):831–47. doi:10.1068/a37214.

- Kittinger, J. N., L. C. Teh, E. H. Allison, N. J. Bennett, L. B. Crowder, E. M. Finkbeiner, and Y. Ota, C. G. Scarton, K. Nakamura, Y. Ota. 2017. Committing to socially responsible seafood. Science 356 (6341):912–13. doi:10.1126/science.aam9969.

- Kyed, H. M. 2021. Everyday justice in Myanmar: Informal resolutions and state evasion in a time of contested transition. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 36 (2):358–62. doi:10.1355/sj36-2m.

- Lawrence, F., and E. McSweeney. 2018 May 18. ‘We thought slavery had gone away’: African men exploited on Irish boats. The Guardian.

- Le, A. N. (2022a). Broker Wisdom: How Migrants Navigate a Broker‐Centric Migration System in Vietnam 1, 2. Paper presented at the Sociological Forum.

- Le, A. N. 2022b. The homeland and the high seas: Cross-border connections between Vietnamese migrant fish workers’ home villages and industrial fisheries. Maritime Studies 21 (3):379–88. doi:10.1007/s40152-022-00272-3.

- Le, A. N. 2022c. Unanticipated transformations of infrapolitics. The Journal of Peasant Studies 49 (5):999–1018. doi:10.1080/03066150.2021.1888722.

- Leder, S. 2022. Beyond the ‘feminization of agriculture’: Rural out-migration, shifting gender relations and emerging spaces in natural resource management. Journal of Rural Studies 91:157–69. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.02.009.

- Mainwaring, Ċ. 2016. Migrant agency: Negotiating borders and migration controls. Migration Studies 4 (3):289–308. doi:10.1093/migration/mnw013.

- Marschke, M., M. Andrachuk, P. Vandergeest, and C. McGovern. 2020. Assessing the role of information and communication technologies in responding to ‘slavery scandals’. Maritime Studies 19 (4):419–28. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00201-2.

- Marschke, M., and P. Vandergeest. 2023. Migrant workers in Irish fisheries: Exploring the contradictions through the lens of racial capitalism. Global Social Challenges Journal 2 (2):146–67. doi:10.1332/27523349y2023d000000003.

- Marschke, M., P. Vandergeest, E. Havice, A. Kadfak, P. Duker, I. Isopescu, and M. MacDonnell. 2020. COVID-19, instability and migrant fish workers in Asia. Maritime Studies 20 (1):87–99. doi:10.1007/s40152-020-00205-y.

- McDowell, R., M. Mason, and M. Mendoza. 2015. AP investigation: Slaves may have caught the fish you bought. Retrieved August 29: 2020.

- Molland, S. 2021. Scalability, Social Media and migrant assistance: Emulation or contestation? Ethnos 1–18. doi:10.1080/00141844.2021.1978520.

- Molland, S. 2022. Safe migration and the politics of brokered safety in Southeast Asia. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Murphy, C., D. M. Doyle, and S. Thompson. 2023. Workers’ perspectives on state-constructed vulnerability to labour exploitation: Experiences of migrant fishers in Ireland. Social and Legal Studies 32 (4):562–85. doi:10.1177/09646639221122466.

- MWG, H. (2021). Joint Civil Society Report Submission to the Committee on the elimination of racial discrimination (CERD). RAccessed February 20, 2023. https://mwgthailand.org/en/press/1623828275

- Nakamura, K., L. Bishop, T. Ward, G. Pramod, D. C. Thomson, P. Tungpuchayakul, and S. Srakaew. 2018. Seeing slavery in seafood supply chains. Science Advances 4 (7):e1701833. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701833.

- Nedelcu, M., and I. Soysüren. 2022. Precarious migrants, migration regimes and digital technologies: The empowerment-control nexus. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 1821–37. Taylor and Francis

- Nolan, J., and G. Bott. 2018. Global supply chains and human rights: Spotlight on forced labour and modern slavery practices. Australian Journal of Human Rights 24 (1):44–69. doi:10.1080/1323238X.2018.1441610.

- Nyers, P. 2015. Migrant citizenships and autonomous mobilities. Migration, Mobility and Displacement 1 (1). doi:10.18357/mmd11201513521.

- Palmgren, P. A. 2022. Reactive control: Development, governance, and Social Reproduction in Thailand’s Regimes of Labor Migration. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Ra, D., and J. Franco (2020). Myanmar’s cross-border migrant workers and the covid-19 pandemic.

- Seo, S., and T. Skelton. 2017. Regulatory migration regimes and the production of space: The case of Nepalese workers in South Korea. Geoforum 78:159–68. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.02.001.

- Sparks, J. L. D., L. Matthews, D. Cárdenas, and C. Williams. 2022. Worker-less social responsibility: How the proliferation of voluntary labour governance tools in seafood marginalise the workers they claim to protect. Marine Policy 139:105044. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105044.

- Stiernström, A., and S. Arora-Jonsson. 2022. Territorial narratives: Talking claims in open moments. Geoforum 129:74–84. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.01.005.

- Stride, J. (2021). Precarity and the pandemic: A survey of wage issues and covid-19 impacts amongst migrant seafood workers in Thailand. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/precarity-and-the-pandemic-a-survey-of-wage-issues-and-covid-19-impacts-amongst-621193/

- Stringer, C., B. Burmester, and S. Michailova. 2022. Modern slavery and the governance of labor exploitation in the Thai fishing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 371:133645. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133645.

- Stringer, C., and T. Harré. 2019. Human trafficking as a fisheries crime? An application of the concept to the New Zealand context. Marine Policy 105:169–176. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.024.

- Stringer, C., D. H. Whittaker, and G. Simmons. 2016. New Zealand’s turbulent waters: The use of forced labour in the fishing industry. Global Networks 16 (1):3–24. doi:10.1111/glob.12077.

- Suhardiman, D., J. Rigg, M. Bandur, M. Marschke, M. A. Miller, N. Pheuangsavanh, and M. Sayatham, D. Taylor. 2021. On the coattails of globalization: Migration, migrants and COVID-19 in Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (1):88–109. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1844561.

- Tickler, D., J. J. Meeuwig, K. Bryant, F. David, J. A. Forrest, E. Gordon, and U. R. Sumaila, B. Oh, D. Pauly, U. R. Sumaila. 2018. Modern slavery and the race to fish. Nature Communications 9 (1):1–9. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07118-9.

- Urbina, I. (2023, 9 October). The crimes behind the seafood you eat. The New Yorker Magazine.

- Vandergeest, P. 2018. Law and lawlessness in industrial fishing: Frontiers in regulating labour relations in Asia. International Social Science Journal 68 (229–230):325–41. doi:10.1111/issj.12195.

- Vandergeest, P., and M. Marschke. 2020. Modern slavery and freedom: Exploring contradictions through labour scandals in the Thai fisheries. Antipode 52 (1):291–315. doi:10.1111/anti.12575.

- Vandergeest, P., and M. Marschke. 2021. Beyond slavery scandals: Explaining working conditions among fish workers in Taiwan and Thailand. Marine Policy 132:104685. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104685.

- Vandergeest, P., M. Marschke, and M. MacDonnell. 2021. Seafarers in fishing: A year into the COVID-19 pandemic. Marine Policy 134:104796. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104796.

- Wilhelm, M., A. Kadfak, V. Bhakoo, and K. Skattang. 2020. Private governance of human and labor rights in seafood supply chains–the case of the modern slavery crisis in Thailand. Marine Policy 115:103833. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103833.

- Yea, S. 2022. Human trafficking and jurisdictional exceptionalism in the global fishing industry: A case study of singapore. Geopolitics 27 (1):238–59. doi:10.1080/14650045.2020.1741548.

- Yea, S., C. Stringer, and W. Palmer. 2022. Funnels of unfreedom: Time-spaces of recruitment and (im) mobility in the trajectories of trafficked migrant fishers. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (1):291–306. doi:10.1080/24694452.2022.2084016.

- Yen, K.-W., and L.-C. Liuhuang. 2021. A review of migrant labour rights protection in distant water fishing in Taiwan: From laissez-faire to regulation and challenges behind. Marine Policy 134:104805. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104805.