ABSTRACT

This article analyses whether the European Union returns more irregular migrants to democratic or autocratic states. It establishes the EU’s return rates with the whole world over a period of twelve years (2008–2019) and connects it to non-EU countries’ democratic credentials. Democracy mattered to some extent in the sense that the EU had generally fewer return orders and higher return rates with democratic states. Yet, a macro perspective indicates that the EU was driven by an interest to maximise returns to non-EU countries, irrespective of the regime type. Some autocratic regimes – and those that became more autocratic – had high return rates and were actively targeted for achieving more returns. A non-EU country’s change towards more or less democratic standards had a comparatively minor likelihood of impacting the EU return rate.

Introduction

The control and return of irregular migrants have become key priorities for the European Union (EU) (European Commission Citation2023a).Footnote1 The EU has bolstered the resources of its border management agency, Frontex, and harmonised its procedures and standards for the return of irregular migrants (Gkliati Citation2022; Majcher and Strik Citation2021). It strived for more formal or informal agreements on readmission with non-EU countries, including with authoritarian countries. It concluded a formal EU readmission agreement with Belarus in 2020 and signed informal return arrangements with states such as Afghanistan (in 2016), Bangladesh (2017), Guinea (2017) and Ethiopia (2018).

These EU initiatives can be seen as an element of the ‘geopolitics of return migration’ (Fakhoury and Mencütek Citation2023; cf.; Hyndman Citation2012), which has become an area of inquiry for scholars. Indeed, the EU’s external relations in the area of return can provide insights into broader shifts in foreign policy-making. On the one hand, the EU’s focus on control has been framed as an attempt to reduce irregular migration and protect the public from (perceived or potential) threats (Bello Citation2022; Huysmans and Squire Citation2010). On the other hand, the EU understands itself as a community of states bound by treaties and puts an emphasis on the fundamental rights and democratic standards. This self-perception has informed its engagement with non-EU countries, captured by the notion of a ‘normative power Europe’ (Manners Citation2002, Citation2006). However, governments across the EU have come under pressure from the far-right. Their actions have been presented as too liberal or not up to the challenge of controlling irregular migration (Lutz Citation2019; Ruzza Citation2018). Several EU readmission agreements and return deals with authoritarian states have been signed in reaction to such debates. Yet, the EU increasingly faces accusations of neglecting its founding values and the rights of migrants by cooperating with autocratic governments for the sake of migration control and return (Batalla Adam Citation2017; Fernando-Gonzalo Citation2023; Slominski and Trauner Citation2021).

This article seeks to contribute to this debate by going beyond the small-n studies that have dominated the field of return governance and applying a bird’s-eye view of the world. It asks whether the EU returns more irregular migrants to democratic or autocratic states. And what happens if the democratic context of a partner country changes – precisely, if a non-EU country becomes more autocratic? The study answers these questions by analysing the EU’s return rate with every country in the world over a period of 12 years and relate it to their state of democracy. The EU return rate is the ratio between orders to leave issued within the EU, and the actual number of people who return to a non-EU country after such an order. While an imperfect measurement for ‘effectiveness’ (Stutz and Trauner Citation2022), the number of leave orders and the ratio itself can – if aggregated – provide evidence for wider patterns of return cooperation that the EU has put in place.

This research focus contributes to a wider debate on the drivers of EU foreign policymaking. When it comes to the EU’s external cooperation on migration, does the EU act on the basis of values as a ‘force for good’ (Barbe and Johansson-Nogues Citation2008)? Is it guided by normative considerations and focusing on mutually beneficial partnerships (Üstin Citation2019)? Or does the EU follow security-driven concerns and a realist understanding of the world (Hyde-Price Citation2006)?

A worldwide view on increasing or high(er) EU return rates with autocratic states could be interpreted as an indicator for the second (realist) argument. It would suggest that the EU is keen to return more migrants irrespective of the regime type of the non-EU country. That said, we demonstrate that the EU’s return rate tends to be higher with democracies worldwide even if there have been notable exceptions. Becoming more or less democratic matters less than the geographical region of a country. The article consists of three parts. First, the link between democracy, autocracy, and EU return policy is conceptualised. Then, we outline our data and methodological approach. The empirical section will then examine the return data in relation to the state of democracies, across the whole world and from a longitudinal perspective. This article concludes with avenues for further research on why the observed dynamics may have occurred.

Democracies, Autocracies, and the EU Return Rate

This section conceptualises the relationship between the state of democracy in a non-EU country, proposing four possible outcomes (see ). The EU may have a high return rate with either democracies or autocracies – or vice versa.

Table 1. Conceptualising the relationship between the EU return rate and the level of democracy in a non-EU country.

Democracies and the EU’s Return Rate

In principle, the EU is expected to cooperate more – and more comprehensively – with other democracies. The EU has a close economic and political relationship with other democracies, particularly from the OECD region. Migration is one cooperation area among others.

The EU understands itself as a community of states interested in promoting democratic norms and values, first and foremost in its enlargement and neighbourhood policies (Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2011). This has occurred through functional cooperation across different policy fields (Freyburg et al. Citation2011; Lavenex Citation2014) or by negotiating agreements to strengthen certain democratic standards (Van Hüllen Citation2019). Moreover, the EU is bound by international law, such as the principle of non-refoulement (Mink Citation2012). It maintains not to expel or forcibly return people to a country in which the returnees’ lives are in danger. Unrest, civil war, or authoritarianism in non-EU countries can, hence, lead to a halt of return operations (and return migration) from the EU. By default, the EU can therefore be expected to return more to democracies where the context is more favourable.

Other democracies may also be more open to rules-based arguments. Returning their own nationals is often seen as an obligation under public international law (Hailbronner Citation1997). Migration is only one area of cooperation – and is often not the most important one. If an EU member state returns a non-EU country national to, say, the US, UK, Canada or an OECD country, this tends to be less contested compared to returning an individual to an autocratic state. However, notable exceptions exist, such as the question of deporting UK citizens from the EU since the end of the Brexit transition period (Henley Citation2023).

Yet, scholars have already highlighted reasons why we may expect that the return rate can be low with democracies. As such, democratic standards may not be a sufficient condition for return rates to be high. Many countries of migrants’ origin greatly benefit from remittances sent back by individuals who made it to Europe or elsewhere. If such a government cooperates with the EU on return and readmission, this is often seen as a betrayal of the interests of its own population (Adam et al. Citation2020; Zanker et al. Citation2019). Return practices may therefore be highly contested, notably in democracies of the Global South. The freer people can express their opposition, the more likely a government will feel electoral pressure to not cooperate on return and readmission. This may cause return rates to be low.

Autocracies and the EU’s Return Rate

A realist perspective on EU foreign policymaking may contrast the perspective of Europe as a ‘force for good’ (Barbe and Johansson-Nogues Citation2008; cf.; Hyde-Price Citation2006). According to the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell, Europe must learn to ‘speak the language of power’. In his view, the EU should develop and strengthen strategic partnerships with international partners to pursue its own interests, including migration (EEAS Citation2020). This perspective is not new. In the early and mid-2000s, the EU sought closer cooperation with countries in the Middle East and North Africa to fight terrorist groups and boost security (e.g., Bicchi and Martin Citation2006). The EU’s external cooperation on security issues gained relevance, often at the expense of the EU’s democratisation efforts (Joffe Citation2008; Bosse Citation2007). Within this context, irregular migrants were already targeted as potential threats ‘who are to be found not in society but on the state’s territory’ (Collyer Citation2006, 266) and, thus, should be returned (cf. Cassarino Citation2010, 40). Securitising migration can lead to a policy shift towards more restrictiveness (Huysmans and Squire Citation2010; Bello Citation2022). The EU’s migration cooperation with authoritarian regimes is often legitimised by a realpolitik approach, which concentrates on the EU’s own security, economic, and public interests. These interests ought to be defended on the basis of a rational cost-benefit calculation. This implies that any non-EU country can and should be convinced to cooperate with the EU if the offered (positive or negative) incentives outweigh the costs of refusal or adaptation (Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier Citation2019).

Still, the EU’s room for manoeuvre is not absolute. The EU’s external cooperation is constrained legally by human rights safeguards, and politically by commitments to shared norms such as the rule of law and democracy. Yet, we have seen a weakening of liberal or value-based approaches in favour of realist ones in the EU’s external dimension (Rynning Citation2011; Lavenex Citation2001; for an overview see; Maher Citation2021). In the migration field, human rights safeguards have been increasingly subject to a narrow interpretation or even a proactive reinterpretation so that more migrants can be returned (Hyndman and Mountz Citation2008; Dedja Citation2012). The EU may argue that non-democracies have areas which are ‘safe’ for returnees within a general context of instability and insecurity (Carrera et al. Citation2016; Parkes Citation2016). For instance, before the Taliban take-over of Afghanistan in mid-2021, EU institutions and agencies argued that some places in Afghanistan (such as Kabul) could be regarded as ‘safe’ for most migrants to be sent back (Blitz, Sales, and Marzano Citation2005; Warin and Zhekova Citation2017).

Regarding non-EU countries, democracies and autocracies might differ significantly regarding their return and exit policies (Natter Citation2023: 688f.). We assume that this may also have an impact on the cooperation between the EU and different non-EU countries. An authoritarian government may seek rewards, recognition, and/or legitimacy by enhancing cooperation with the EU on return and readmission (Koch, Weber, and Werenfels Citation2018). Autocratic states can strategically link the EU’s demands to their own priorities (such as Morocco which asked the EU for support to capacity building and modernisation). However, a lack of cooperation is possible too (and has been detected, for instance, in the case of Algeria; see Werenfels Citation2018). In general, autocracies tend to make strategic choices on migration policies depending on whether they consider emigration beneficial for regime survival (Miller and Peters Citation2020; Tsourapas Citation2018). Similar strategic considerations can be assumed to take place regarding return migration – if returnees are considered to contribute to a risk of (democratic) regime change from the perspective of the autocratic regime in place, they may not be let in again.

Towards More or Less Democracy

Of interest is not only a static picture, implying whether or not an autocratic regime cooperates with the EU at a given moment in time. What happens on the ground over time – for instance, if a regime becomes more democratic?

It seems obvious that the EU hopes to cooperate more with a democratising country (for instance, after a military dictator is ousted). The cooperation gets less politically contentious and can be framed more easily as legitimate and built upon common values (Bodansky Citation2012). Yet, a realist perspective may quickly accentuate such hopes. The democratic standards of a third country might be less consequential for the cooperation compared to its material interests vis-à-vis the EU. They may remain the same even if a more democratic government is in place.

The literature provides some hints in this respect, although our knowledge is primarily based on small-n studies. Looking at the Tunisian revolution of 2011, Natter (Citation2015) investigated how migration cooperation changed after a political transition towards more democracy. While Tunisia cooperated closely with Italy and the EU, the Tunisian government faced an increasingly vocal electorate, calling for ‘more dignity, human rights, and freedom in their migration policies’ (Natter Citation2015, 16). These insights have been echoed by a study in the Gambia, which ousted a long-term dictator in a 2016 election. According to Cham and Adam, the migration theme became quickly politicised once the Gambia started to have a freer press and an open public debate after 2016. While the new government was keen to improve relations with the EU and also (initially) agreed to cooperate more on forced returns, the actual policy did not change that much once the politicisation kicked in. The domestic pressure to not cooperate with the EU on return issues turned out to be very high (Cham and Adam Citation2023). In other words, the politics of the Gambia changed but the migration policy outcome remained largely the same.

If a regime becomes more authoritarian, the cooperation with EU may also deteriorate. The EU-Belarusian border crisis of mid-2021 was a case in point in this regard. The Lukashenko regime actively tried to exert pressure on the EU by facilitating the influx of migrants and stopping cooperation on return (Bodnar and Grzelak Citation2023). Academic debate on the topic of democratic backsliding provides a different angle on EU migration cooperation. The EU’s heightened focus on migration control in its cooperation with non-EU countries may have had a negative impact on the democratic quality of such a country or even contributed to backsliding. Ozcurumez makes this argument by focusing on the societal resilience of migrant-host countries in the Eastern Mediterranean (especially in Turkey) (Ozcurumez Citation2021, 1312; cf.; Tansel Citation2018). Differently, our research does not focus on whether democratic quality has an impact on return cooperation with the EU (or vice versa). Yet, we acknowledge that this complex relationship can have an impact that is mutually reinforcing.

Operationalising the Research Interest

The EU – similar to the understanding and practices of the US and most other Western states – draws a distinction between ‘voluntary’ and ‘enforced’ returns of irregular migrants. The distinction concerns the level of cooperation of the person ordered to leave. ‘Removal’ implies the ‘enforcement of the obligation to return, namely the physical transportation out of the Member State’ (EU Directive 2008/115/EC, Article 3, European Union Citation2008). A person may also leave ‘voluntarily’ after such an order, thereby avoiding a forced return.

Eurostat data on forcible returns can include data on voluntary and assisted returns (after individuals have received an order to leave) with data on forcible returns, as member states register the status of a person who is not authorised to remain in quite different ways.Footnote2 This means that the data on voluntary/assisted returns and forcible returns is not differentiated enough for us to say with analytical certainty whether a person has been returned by state authorities or returns ‘voluntarily’ (on own initiative or with an assisted return programme). Therefore, the EU’s return rate also depends on what migrants may do (or are compelled to do) after an order to leave. There may be autocratic countries with high return rates even if the EU is not actively seeking to increase the return cooperation.

In any case, scholars often put aside the technicalities of return procedures. Peutz and De Genova define deportation as the ‘compulsory removal of “aliens” from the physical, juridical, and social space of the state’ (Peutz and De Genova Citation2010; cf.; Van Houte Citation2014). Such a definition underemphasises the operational form of return. What is important is the element of ‘compulsiveness’ in terms of having to leave a territory. ‘Voluntary’ returns are publicly and politically less contentious (ECRE Citation2018) and are favoured by the EU and its member states (cf. Cherti and Szilard Citation2013; Paasche Citation2014).Footnote3 Yet, discussions around procedures risk over-emphasising the manner in which a person leaves. Hence, some scholars call for a ‘terminological readjustment’ (Cassarino Citation2014, 17). In this article, we subscribe to this understanding and focus on migrants compelled to leave the EU, leaving aside other forms of ‘return migration’ (cf. King and Kuschminder Citation2022; Kessler and Rother Citation2016).

Our key research interest is to visualise and discuss macro-trends relating to the state of democracy and the return rate. We seek to provide a macro, longitudinal perspective on how democratic standards and processes of democratisation may impact the EU return rate. Throughout the article, however, we are cautious in terms of claiming causality. Different factors may affect the return of a person, aside from the regime type of a third country. Within the EU, policy-makers may prioritise the return of irregular migrants very differently (Leerkes and Van Houte Citation2020; Cleton Citation2022; Finotelli Citation2018) or struggle to legitimatise the deportation of well-integrated migrants, or migrants with a vulnerable background (Cleton Citation2022). Everyday state practices as well as migrant strategies to move and resettle can also influence what has been called the ‘geopolitics of migrant mobilities’ (Ashutosh and Mountz Citation2012). Planned deportations may be prevented by judicial challenges or local protest movements that often spontaneously form to prevent it (Acosta and Geddes Citation2013; Rosenberger Citation2018). With regard to the external dimension, Cassarino (Citation2010) argues that the EU’s readmission cooperation hinges on the EU incentives, geographical proximity and the salience of the migration issue in a non-EU country. The number of ‘implementing protocols’ that an EU member states signs with a non-EU country tends to influence the actual application of an EU readmission agreement (Carrera Citation2016). More widely, bilateral readmission cooperation between member states and non-EU countries remains relevant yet the EU has become a vehicle for migration control by national governments (Leerkes, Maliepaard, and van der Meer Citation2022; cf. Leerkes and Van Houte Citation2020). It should also not be underestimated as to how reintegration issues impact a receiving state’s policy approach. In a highly disputed ‘post-deportation market’, migrants, states and civil society actors often stand opposite each other and compete for funds (Sylla and Cold-Ravnkilde Citation2022; also; Marino, Schapendonk, and Lietaert Citation2023).

This article acknowledges these different factors and dynamics, but it does not engage in testing their relative importance. Our key research interest is to get a worldwide picture of the relationship between the EU return rate and the state of democracy. The return rate is therefore a measurement to assess the differences between cooperation partners without claiming that it is a perfect – or even the only appropriate – instrument to capture EU (migration) cooperation patterns.

The Data Underlying the Analysis

We rely on different Eurostat datasets. One dataset outlines the number of persons ordered to leave in the EU member states. Another presents the numbers of persons who returned to a non-EU country after such an order to leave. Dividing the latter by the former, we calculate the ‘EU return rate’ for all non-EU countries in the world.Footnote4 We establish the EU return rate for each country in the world over a period of twelve years, concretely from 2008 to 2019.Footnote5 The data collection for the Eurostat datasets regarding ‘persons being returned after having received an order to leave’ and ‘persons being ordered to leave’ starts at 2008. The investigation period is cut off from 2020 onwards, the return numbers and return rates are very low primarily due to the border closings in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a particular context which we seek to exclude to avoid the distortion of a more longitudinal picture. However, we provide an overview over the whole period from Eurostat’s start of data collection until 2019.

We look at the aggregate scores of the ‘Freedom in the World’ (FIW) index of the Freedom House dataset. They are based on seven different dimensions that broadly assess ‘political rights’ and ‘civil liberties’ (Freedom House Citation2023). The FIW dataset relies on experts to code sub-indicators subjectively. Each score is subsequently reviewed by other experts and Freedom House staff to ensure ‘methodological consistency, intellectual rigor, and balanced and unbiased judgments’ (Freedom House Citation2021). There is some debate about the quality of Freedom House and other democracy indices (Munck and Verkuilen Citation2002; Steiner Citation2016). However, we are less interested in contributing to an understanding of the very score of a non-EU country. Rather, we compare the level of democracy with the level of return of migrants having received an order to leave the EU.

The EU’s return data has also been subject to criticism given that the definitions and methods of collecting this data in member states sometimes diverge (Mananashvili Citation2017; Singelton Citation2016; Stutz and Trauner Citation2022; Scheel Citation2024). We take the quality and reliability of the data seriously. Using aggregate scores for ‘democracy’ and ‘return rate’ allows us to divide countries in ‘high’ and ‘low’ levels (separated by the average mean for both indicators). This entails that our assessment of a country’s score is relative to the other countries. This methodological choice has the benefit to reflect upon the cooperation patterns between the EU and different regime types of non-EU countries worldwide. In doing so, we also avoid focusing on exact scores, as probabilistic methods would do. Also, a longitudinal perspective and a comparison of the whole world allows mitigating some technical problems, which are likely to be of more relevance in specific years and/or with particular partners.

The EU’s Return Rate and Democratic Standards Worldwide

The empirical analysis starts with a global view of the EU’s return rate (). The darker a country, the higher the return rate. The EU average return rate with non-EU countries for 2008–2019 was about 33%. In 2019, it was 29%. We present the average data for all non-EU and non-Schengen countries which had at least received 200 orders to leave for the whole time period and we cut off the return rate at 100%.

Figure 1. EU’s return rate with non-EU countries (average 2008–2019); adapted from (Stutz and Trauner Citation2022, 159).

A word of caution: A country may reach a high return rate more quickly in case overall numbers are low (few removal orders and few, or rather, slightly higher number of returns than removal orders). This is, for instance, the case with island states in the Caribbean and the Pacific as well as with states in the Arabian Peninsula, but also countries in the south of Africa such as Botswana and Namibia. Another factor that increases some countries’ return rates is a large share of voluntary returns. Theoretically, this type of returns should be excluded from the dataset, but some member states report them together with the forced returns. For example, based on available Eurostat data ca. 30 citizens of Saudi Arabia have been returned forcefully; ca. 150 returns have been conducted ‘voluntarily’ (ca. 20 member states collected data on this from 2014 until 2019). Overall, there are about 2,500 returns from the member states to Saudi Arabia in the same period compared to 1,500 orders to leave. This results in a return rate of more than 100%, even though it seems most returns are not forcible ones.Footnote6

Voluntary return after a removal order is also of high relevance for other OECD countries such as the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Overall, the EU’s return rate is highest with Southeastern and Eastern neighbours, North American states, countries in Southern Africa, and Australia. Asia has seen higher return rates from the EU compared to Sub-Saharan Africa (and also South America).

In the next figures, we take a look at the relationship between democracy and the EU’s return rate. We examine the relevance of each possible outcome. The bubble size shows the total number of removal orders issued for citizens of the country between 2008 and 2019. In other words, the bigger a bubble is for a country, the more people with the corresponding citizenship have received a leave order. The higher up the country, the higher the return rate. These numbers are contrasted with the aggregate score of the FIW-index for each partner country. The higher the FIW aggregate score (the more to the right), the more democratic a country is considered to be.

The outcome ‘high democracy/high return rate’, shown in , includes different OECD countries (such as the US, Canada, Australia, Israel, Chile, and New Zealand) and a range of other countries with a comparatively high aggregate score on the FIW-scale (such as Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia). These states tend to share certain features. They have relatively high democratic standards, relatively few removal orders and relatively high return numbers. Noticeably, the bubbles are relatively small, indicating fewer removal orders for citizens of these countries.

Higher return numbers in this group of states are primarily applicable to countries seeking to come closer and join the EU in the future including Albania, Ukraine, Serbia, North Macedonia, Moldova, and also Georgia (Georgia had very low return rates in 2008 and 2009 but it consistently oscillated between 52 and 66% between 2016 and 2019). Brazil is an exception in this regard. It can be added to this group, with a return rate at around 45% and relatively high numbers of removal orders.

The EU often considers countries in the Western Balkans and in Eastern Europe primarily as transit countries. That is why the cooperation strongly focuses on border controls and is led by Frontex. The citizens of these neighbouring states usually enjoy visa-free travel, which renders cooperation on return less contentious (Council of the EU Citation2024). A similar dynamic likely plays out with other OECD countries that are not members of the EU. Topics such as the strengthening of institutional capacities and the rule of law might be more prevalent with this type of non-EU states, notably if compared to the relevance of migration themes with priority countries in Africa (Ibid.).

turns the attention to the countries that have comparatively low democratic standards and low return numbers from the EU. This category ranges from China and Pakistan to states in Africa and the Middle East. Among the states having a return rate lower than 10% belong Chad, Congo, Mauritania, and Ivory Coast. Between 2008 and 2019, the comparatively highest number of removal orders of states were issued to citizens of Morocco, Afghanistan, Syria, Pakistan, Iraq, and Algeria.Footnote7 The case of China is noteworthy. It has low democratic credentials yet a relatively high number of return orders. Within this category of ‘low democratic standards, low return rate’, China is at the upper end with a return rate of 34.4% on average for the whole period (roughly 42,000 returns).

For countries in , the return decisions were often the subject of contestations and legal appeals given that many of the countries refrained from adhering to human rights’ standards. The highly contested nature of forcible returns from Germany to Afghanistan before the take-over of the Taliban in mid-2021 was a point in case for this (Sökefeld Citation2019). Furthermore, compared to Eastern Europe or the Western Balkans, the EU did not employ the incentive of visa facilitation/liberalisation to sign a readmission agreement and increase return numbers with these states (cf. Ademmer and Delcour Citation2016; Hernandez i Sagrera Citation2014).

At the same time, in this group we also find many countries whose economies are highly dependent on remittances of their diasporas, which might make the governments of these countries less inclined to cooperate with the EU (see e.g Adam et al. Citation2020; Zanker et al. Citation2019).

We can see, however, that return is hardly non-existing with this group of countries. The average EU return rate since 2019 has decreased even further and stays below 20% since 2020. Many of the countries in this group have, comparatively speaking, a rather high return rate, especially Morocco, Algeria, Pakistan, Iraq, China, Iran, and Nigeria. With many of these countries, the EU has actively sought to cooperate on return by proposing new readmission agreements (China, Morocco, Algeria and Nigeria), or has even concluded an agreement (Pakistan in 2010); especially the African countries have been named as priority countries for cooperation (European Commission Citation2016). This shows that the level of return might be low(er), but it is not for a lack of trying on the EU’s part. This lends cause to view the EU’s efforts as trying to maximise return capacities due to its own interests. This is also reflected by the fact that the EU has continuously sent senior officials such as the High Representative and different Commissioners to West and North Africa to discuss the issues of migration and return (Council of the EU Citation2024). Therefore, the EU is not suspending return because of a value-based policy to not return people to autocracies. It rather might not be capable to increase returns – while at the same time the EU continues to return to countries in this group.

represents states that feature relatively low regarding democratic credentials but have a comparatively high return rate with the EU. Importantly, our data does not include the developments after the Russian invasion of Ukraine which started in February 2022 (but covers the period 2008–2019). Prior to this invasion, Russia and Belarus had relatively high return numbers (the EU signed a readmission agreement with Belarus in June 2020). Both the removal orders and return numbers were above average until 2018.

The absolute number of removal orders and return numbers were, in comparison, much lower with the Central Asian countries Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan, yet they consistently showed very high average return rates. Kosovo was also a case with both a high number of removal orders and return rates. In the Freedom House data, Kosovo was put as a country with lower democratic standards compared to the average mean of the countries included in the dataset. However, it managed to be consistently above this average from 2014 to 2019. Nicaragua and Malaysia were also close to the average mean, yet Nicaragua’s FIW score decreased consistently after 2015 and Malaysia was consistently slightly below the average mean.

With few exceptions such as Russia, the number of removal orders (i.e. the size of the bubble) was relatively small for this category of states. The EU has actively sought to cooperate with several of them. It has readmission agreements with Russia, Belarus, and Azerbaijan regardless of the fact that such agreements were criticised by the European Parliament and civil society actors (European Parliament Citation2017). Again, the cooperation with countries in this group indicates that the EU has been proactively seeking to return migrants to some states lacking democratic credentials.

While there are some autocratic states with high return numbers, the opposite can be found too – more democratic states with lower return rates from the EU (shown in ). Some examples were Nigeria (23%), Tunisia (21%), Ghana (22%), Senegal (11%), Cape Verde (9%), and Niger (10%). India and Turkey can also be included in this category. For the period 2008–2019, Freedom House scored them comparatively high while their return rates have been at around 30%.

This figure sheds light on a few states that have long been in the centre of interest for the EU’s return cooperation. The EU has been keen on negotiating a readmission agreement or an informal return arrangement with states such as Nigeria and Senegal (Reslow and Vink Citation2015). Also, they were designated as priority countries in 2016, yet the cooperation on return has lagged behind the EU’s expectations (Council of the EU Citation2024). Especially in Africa, cooperation with the EU on migration control and return has been very contentious (Adam et al. Citation2020). More recently, however, the EU has doubled down its efforts. A series of visits by senior EU officials were followed by new proposals including Talent Partnerships for Tunisia, Nigeria and Senegal (Council of the EU Citation2024). In July 2023, Tunisia agreed on a ‘comprehensive partnership package’ which was meant to reduce irregular migration from the country (European Commission Citation2023b).

What is the overall picture? The four figures show that there tended to be a positive relation between democracies and the EU return rate. Low(er) democratic standards went hand-in-hand with low(er) return rates. This was, in fact, the most relevant category in terms of removal orders issued by the EU to non-EU country nationals. The same relationship was visible at the other end, too. Return rates tended to be high with most states having high democratic standards. However, a clear positive relation was undermined by some autocratic states which had comparatively high return numbers with the EU for our period of investigation, including Russia and Belarus.

Becoming More Democratic or Autocratic

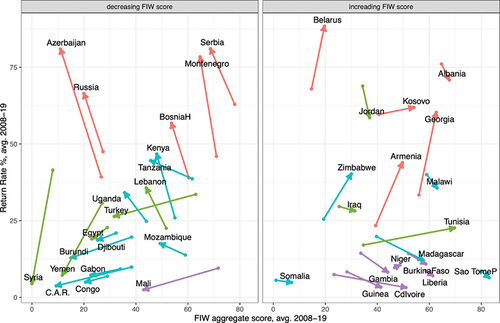

This section examines the consequences of non-EU countries becoming more democratic or autocratic for the EU return rate. In a first step, we selected the countries that changed most in terms of becoming either more democratic or autocratic in the examination period. In a next step, we looked at the countries in the regions of the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe (in in red); West Africa (in purple); Central, East and Southern Africa (in blue); and Middle East/North Africa and Turkey (MENA+T, in green). On the one hand, the Western Balkans and Eastern Europe are regions with comparatively high return rates, that are based on high numbers of returned people. If these numbers decreased, they would affect the overall average EU return rate with non-EU countries, so it is in the EU’s interest to maintain high return rates with these regions (cf. Stutz and Trauner Citation2022). On the other hand, Africa and the MENA region are in the EU’s focus due to their lower than EU average return rates, as specified in the EU’s Action Plan on Return of 2015 (European Commission Citation2015, 10). As seen in the overall bubble plot (see also figure in Annex), countries from these regions had either very high return rates (Eastern Europe) or very low return rates (West African and MENA-countries), while their FIW scores varied significantly.

Figure 6. Changes in democratisation and EU return rate in selected regions (average scores for 2009–2011 and 2017–2019).

We further explore the countries in these regions by looking at the changes in their FIW-scores and compare their scores at the beginning and the end of the examination period. In concrete terms, we create average scores for the two periods of 2010–12 and 2017–19. includes selected countries from the top 30 countries that had (on average) decreased or increased their FIW-score in both time periods. The left plot shows all the countries that shifted towards authoritarianism. On the right, we can see countries that were seen to improve their democratic credentials until 2019. The arrows indicate the development of their return rates over the two examination periods.

A striking finding of is that the return rate often develops in a similar direction, irrespective of whether a country gets more autocratic or democratic. Eastern and Southeastern European countries changed the most (Russia and Azerbaijan in terms of becoming more autocratic; Georgia, Armenia and Kosovo in terms of becoming more democratic). Irrespective of these changes, they all started to have higher return rates. For instance, some countries in Eastern and Southeastern Europe became more democratic (such as Georgia or Kosovo) or more autocratic (such as Serbia and Russia). Albania was the only exception in this region as it saw a slight decrease of average return rates in comparison to the levels of the early 2010s. Yet, this country remained on a very high level until 2019.Footnote8

A similar development took place in West Africa, albeit in the opposite direction. Practically all West African states developed lower return rates. This concerned Mali turning more autocratic and states such as the Gambia and Guinea becoming more democratic during our investigation period. The situation is slightly less clear-cut for the MENA region and the rest of Africa. The return rates of Turkey and countries in the MENA region decreased, although Tunisia and Lebanon were exceptions (at a relatively low average). The return rate of other African states tended to go down too, irrespective of their (non-)democratisation. Here too, some countries were exceptions, such as Zimbabwe or Kenya.

According to , democratisation does not seem to have a lot of influence on whether the return rate goes down or up. It also indicates that EU readmission agreements or informal return deals may not make much of a difference either (Stutz and Trauner Citation2022). In Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans, most countries had an EU readmission agreement during the examination period, yet Belarus (that concluded an agreement only in 2020) did not. Still, it had the highest return rate of all countries shown in . Furthermore, Turkey, and the Gambia, Guinea and Ivory Coast concluded a readmission agreement or arrangements, but their return rates did not increase; in fact, their trajectory followed other countries in their regions.

In addition, the EU has sanctioned three countries under the Visa Code due to low return rates over the last years, namely the Gambia, Iraq and Bangladesh. They all have experienced either a democratisation process or have comparatively high democracy levels (see also ). While these are too few cases to make generalisations, this might indicate that the EU assumes that negative incentives have a potentially bigger impact on, comparatively, more democratic or democratising countries (cf. European Commission Citation2023c).

The analysis has therefore shown that there is a convergence trend within the regions of Eastern Europe and in West Africa. In the former region, the states mostly moved towards higher return rates and in the latter, they remained the same or decreased. Becoming more or less democratic has been of secondary importance within these wider trends.

Conclusions

The article has investigated how changes towards more or less democratic standards, and the overall level of democratic quality may have an impact on the rate of returns of irregular migrants from the EU. It has done so by establishing the return rate that non-EU countries all around the world had with the EU and relating it to their democratic credentials. The period of investigation has been from 2008 to 2019. The data derived from Eurostat and the ‘Freedom in the World’-index provided by Freedom House.

The article has in particular investigated whether the EU has higher return rates with democracies than autocracies. Also, it has looked at whether democratisation processes coincide with higher return rates. The answer to the first question is a partial yes. The data has shown that this concerned in particular other OECD countries and democratic states in the EU’s eastern and Southeastern neighbourhood. However, a clear positive relation was undermined by some autocratic states which had comparatively high return numbers with the EU during our period of examination, including Russia and Belarus. China also had a return rate only slightly below the EU’s average. Similarly, some states with higher democratic standards (including Tunisia, Ghana, India and Japan) had a lower return rate.

Furthermore, the article has investigated whether changes towards more or less democracy, denoted by changes to the FIW-democracy scores co-occur with a higher return rate. The answer is that it depended on the region. We specifically compared those countries in Eastern Europe, the Western Balkans, West Africa and the MENA region and Turkey that are among those countries that have seen the biggest (positive and negative) changes to their democracy scores. In (South-)Eastern Europe, both governments that got more democratic or more autocratic started to have higher return rates with the EU. In West Africa, the opposite can be observed. Both democracies and autocracies show lower return rates (or stagnating ones on low levels). In other regions, the picture was more mixed. Overall, there are indications that the EU is more inclined to employ positive and negative incentives vis-à-vis more democratic or democratising countries.

How does the article hence contribute to the state of the literature? Empirically, the article confirms previous small-n studies indicating that autocratic states may differ from one another in their handling of the EU (cf. Natter and Thiollet Citation2022, Koch, Weber, and Werenfels Citation2018). There is no evidence from a bird’s-eye view that autocratic states – or states that become more autocratic over time – are likely to cooperate more with the EU and/or have higher return rates than their democratic peers. On the contrary, there is always the risk that their systems of oppression trigger new refugee flows and/or a halt of return migration. A process towards democratisation does not automatically increase the return rate over time. Democracies matter to some extent but the forcible returns of migrants from the EU cannot be explained by the regime type of a non-EU country alone.

On a theoretical level, the research supports a realist understanding of EU foreign policymaking. While more research is needed to delve into individual cases, the macro-perspective indicates that the EU is less driven by normative, value-based constraints than by an interest to maximise returns to (most) non-EU countries. The EU prefers to cooperate with democracies (and vice-versa), which tend to have higher return rates. Yet autocratic regimes or those becoming more autocratic are not excluded as partners for achieving more returns. This realist understanding sheds new light on the ‘geopolitics of return migration’ and enriches the literature on migration diplomacy and EU foreign policy (cf. Vathi, King, and Kalir Citation2023: 382f; Fakhoury and Mencütek Citation2023; Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019; Pänke Citation2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on earlier drafts. Previous other versions of this article have been presented at different conferences including the IMISCOE General Conference, ECPR Standing Group EU Conference, the EU in International Affairs Conference and the workshop ‘The frontiers of EU external migration governance’ at the London School of Economics. We would like to thank the respective panel participants for their constructive feedback. The financial support of Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) for the ERC Follow-up project ‘The creation of a dataset on coercive EU mobility rules’ (FWOEUMOB; G0G2821N) is gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. We follow the EU’s terminology regarding the term ‘return’ to avoid confusion with the datasets from which we derive our data. It indicates the forcible removal of migrants having no longer an authorisation to be present or stay on the territory of the EU and its member states. In practice, the term can be equated with repatriation or deportation.

2. According to Eurostat, the data can ‘include forced returns and assisted voluntary returns. ‘Unassisted voluntary returns are included where these are reliably recorded’, as discussed in the meta data file of Enforcement of Immigration Legislation statistics (Eurostat Citation2023). What is more, Eurostat presents statistics for voluntary and assisted returns in other datasets. We do not include these as they do not cover the whole investigation period and not all member states. This results in further data issues.

3. When comparing different Eurostat datasets (‘Enforcement of Immigration Legislation’; statistics on ‘voluntary return’) with the return data of Frontex, we can see that, on average, about half of the returnees leave with assistance from a return programme. Yet, this does not necessarily indicate that 50% of persons leave ‘voluntarily’, as the data is difficult to compare.

4. We do this separately for each year and the whole period between 2008 and 2019 (with the average mean). If there is no data available for a year or no person has been returned, we treat the case as having a return rate of 0%; if no person was ordered to leave but people were returned, the return rate is 100%. Countries to which continuously less than 25 persons are returned are excluded from the analysis. We cut off the return rate at 100%.

5. The EU has stopped including the United Kingdom in its migration data both pre- and post-Brexit. However, we include the United Kingdom’s figures for our calculations since we seek to analyse the return policy retrospectively. The UK’s average return rate was always higher than the rest of the EU member states. It had an important influence on the EU’s return policy and cooperation which likely continues to have an impact even after Brexit.

6. Eurostat has confirmed this upon author’s request.

7. See similarly for Germany, e.g., (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2023: 35f).

8. In 2016/2017, the average return rate was over 100%, but saw a drop below 50% in 2019 – the lowest value for Albania since 2011 which resulted in this slight decrease of the average.

References

- Acosta, D., and A. Geddes. 2013. The development, application and implications of an EU rule of law in the area of migration policy. Journal of Common Market Studies 51 (2):179–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02296.x.

- Adam, I., F. Trauner, L. Jegen, and C. Roos. 2020. West African interests in (EU) migration policy. Balancing domestic priorities with external incentives. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 46 (15):3101–18. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1750354.

- Adamson, F., and G. Tsourapas. 2019. Migration diplomacy in world politics. International Studies Perspectives 20 (2):113–28. doi: 10.1093/isp/eky015.

- Ademmer, E., and L. Delcour. 2016. With a little help from Russia? The European Union and visa liberalization with Post-Soviet States. Eurasian Geography and Economics 57 (1):89–112. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2016.1178157.

- Ashutosh, I., and A. Mountz. 2012. The geopolitics of migrant mobility: Tracing state relations through refugee claims, boats, and discourses. Geopolitics 17 (2):335–54. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2011.567315.

- Barbe, E., and E. Johansson-Nogues. 2008. The EU as a modest “force for good”: The European neighbourhood policy. International Affairs 84 (1):81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00690.x.

- Batalla Adam, L. 2017. The EU-Turkey deal one year on: A delicate balancing act. The International Spectator 52 (4):44–58. doi: 10.1080/03932729.2017.1370569.

- Bello, V. 2022. The spiralling of the securitisation of migration in the EU: From the management of a ‘crisis’ to a governance of human mobility?. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (6):1327–44. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851464.

- Bicchi, F., and M. Martin. 2006. Talking tough or talking together? European security discourses towards the Mediterranean. Mediterranean Politics 11 (2):189–207. doi: 10.1080/13629390600682917.

- Blitz, B. K., R. Sales, and L. Marzano. 2005. Non-voluntary return? The politics of return to Afghanistan. Political Studies 53 (1):182–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00523.x.

- Bodansky, D. 2012. Legitimacy in International Law and International relations.’ chapter. In Interdisciplinary perspectives on International Law and International relations: The state of the art, ed. J. Dunoff and M. Pollack, pp. 321–42. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bodnar, A., and A. Grzelak. 2023. The Polish–Belarusian Border crisis and the (lack of) European Union response. Bialystok Legal Studies 28 (1):57–86. doi: 10.15290/bsp.2023.28.01.04.

- Bosse, G. 2007. Values in the EU’s neighbourhood policy: Political rhetoric or reflection of a coherent policy? European Political Economy Review 7 (1):38–62.

- Carrera, S. 2016. Implementation of EU readmission agreements. ebook: Springer.

- Carrera, S., J.-P. Cassarino, N. El Quadim, M. Lahlou, and L. den Hertog. 2016 January 22. EU-Morocco cooperation on readmission, borders and protection: A Model to follow?’ Centre for European Policy Studies, CEPS Paper Nr 87.

- Cassarino, J.-P. 2010. Readmission policy in the European Union. Brussels: European Parliament, PE 425.632.

- Cassarino, J.-P. 2014. Bridging the policy gap between reintegration and development. In Reintegration and Development, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, ed. J.-P. Cassarino, pp. 1–18. Robert Schuman Centre Research Report. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/30401/Reintegration-and-Development-CRIS.pdf.

- Cham, O. N., and I. Adam. 2023. The politicization and framing of migration in West Africa: Transition to democracy as a game changer? Territory, Politics, Governance 11 (4):638–57. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2021.1990790.

- Cherti, M., and M. Szilard. 2013. ‘Returning irregular migrants: How effective is the EU’s response?’. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. https://ippr-org.files.svdcdn.com/production/Downloads/returning-migrants-EU-130220_10371.pdf. Online.

- Cleton, L. 2022. The time politics of migrant deportability: An intersectional analysis of deportation policy for non-citizen children in Belgium and the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (13):3022–40. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1926943.

- Collyer, M. 2006. Migrants, migration and the security paradigm: Constraints and opportunities. Mediterranean Politics 11 (2):255–70. doi: 10.1080/13629390600682974.

- Council of the EU. 2024. Update on the state of play of external cooperation in the field of migration policy. Brussels, 5484/24 LIMITE.

- Dedja, S. 2012. Human rights in the EU return policy: The case of the EU-Albania relations. European Journal of Migration and Law 14 (1):95–114. doi: 10.1163/157181612X628291.

- Deutscher Bundestag. 2023. Ergaenzende Informationen zur Asylstatistik fur das Jahr 2022. Berlin, Drucksache. https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/057/2005709.pdf.

- ECRE. 2018. Voluntary departure and return: Between a rock and a hard place. Policy Brief Nr. 13, European Council on Refugees and Exiles. Online: https://www.ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Policy-Note-13.pdf.

- EEAS. 2020. Europe must learn quickly to speak the language of power. European External Action Service. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/several-outlets-europe-must-learn-quickly-speak-language-power.

- European Commission. 2015. EU action plan on return. Brussels, COM(2015) 453 final.

- European Commission. 2016. Communication from the commission on establishing a new partnership framework with third countries under the European agenda on Migration’. Strasbourg, COM(2015) 385 final.

- European Commission. 2023a. Towards an operational strategy for more effective returns. Brussels, COM(2023) 45 final.

- European Commission. 2023b. The European Union and Tunisia: Political agreement on a comprehensive partnership package. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/european-union-and-tunisia-agreed-work-together-comprehensive-partnership-package-2023-06-11_en.

- European Commission. 2023c. Report from the commission to the council: Assessment of third Countries’ level of cooperation on readmission in 2022. Brussels, COM(2023) 467 final.

- European Parliament. 2017. European parliament recommendation of 15 November 2017 to the council, the commission and the EEAS on the Eastern partnership, in the run-up to the November 2017 summit, 2017/2130(INI).

- European Union. 2008. Directive 2008/115/EC of the European parliament and of the council of 16 December 2008 on common standards and procedures in member states for returning illegally staying third-country nationals.

- Eurostat. 2023. Enforcement of immigration legislation (migr_eil): Reference metadata in euro SDMX metadata structure (ESMS). Luxembourg: Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/migr_eil_esms.htm. Online.

- Fakhoury, T., and Z. S. Mencütek. 2023. The geopolitics of return migration in the International system. Geopolitics 28 (3):959–78. doi:10.1080/14650045.2023.2187981.

- Fernando-Gonzalo, E. 2023. The EU’s informal readmission agreements with third countries on migration: Effectiveness over principles? European Journal of Migration and Law 25 (1):83–108. doi:10.1163/15718166-12340145.

- Finotelli, C. 2018. Southern Europe: Twenty-five years of immigration control on the waterfront. In Routledge handbook of justice and home affairs research, ed. A. R. Servent and F. Trauner, pp. 240–52. London: Routledge.

- Freedom House. 2021. Freedom in the world 2021 methodology. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/FreedomInTheWorld_2021_Methodology_Checklist_of_Questions.pdf.

- Freedom House. 2023. Freedom in the World 2023: Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2023/marking-50-years.

- Freyburg, T., S. Lavenex, F. Schimmelfennig, T. Skripka, and A. Wetzel. 2011. Democracy promotion through functional cooperation? The case of the European neighbourhood policy. Democratization 18 (4):1026–54. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.584738.

- Gkliati, M. 2022. The EU returns agency: The Commissions’ ambitious plans and their human rights implications. European Journal of Migration and Law 24 (4):545–69. doi:10.1163/15718166-12340140.

- Hailbronner, K. 1997. Readmission agreements and the obligation of states under Public International Law to readmit their own and foreign nationals. Zeitschrift für Ausländisches Öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht 57 (1):1–50.

- Henley, J. 2023. Brexit: Thousands of Britons expelled from EU since end of transition period. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2023/jan/06/brexit-thousands-britons-expelled-eu.

- Hernandez i Sagrera, R. 2014. Exporting EU integrated border management beyond EU borders: Modernization and institutional transformation in exchange for more mobility? Cambridge Review of International Affairs 27 (1):167–83. doi:10.1080/09557571.2012.734784.

- Huysmans, J., and V. Squire. 2010. Migration and security. In The Routledge handbook of security studies, ed. M. D. Cavelty and V. Mauer, pp. 169–79. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hyde-Price, A. 2006. “Normative” Power Europe: A Realist Critique. Journal of European Public Policy 13 (2):217–34. doi:10.1080/13501760500451634.

- Hyndman, J. 2012. The geopolitics of migration and mobility. Geopolitics 17 (2):243–55. doi:10.1080/14650045.2011.569321.

- Hyndman, J., and A. Mountz. 2008. Another brick in the wall? Neo-refoulement and the externalization of asylum by Australia and Europe. Government and Opposition 43 (2):249–69. doi:10.1111/j.1477-7053.2007.00251.x.

- Joffe, G. 2008. The European Union, democracy and counter-terrorism in the Maghreb. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 46 (1):147–71. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00771.x.

- Kessler, C., and S. Rother. 2016. Democratization through migration? Political remittances and participation of Philippine return migrants. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- King, R., and , Kuschminder, K. 2022. Introduction: definitions, typologies and theories of return migration. In Handbook of return migration, ed. King, R., and K. Kuschminder, pp. 1–22. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Koch, A., A. Weber, and I. Werenfels. 2018. Profiteers of migration? - Authoritarian States in Africa and European migration management. SWP Research Paper 4. Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

- Lavenex, S. 2001. Migration and the EU’s New Eastern Border: Between realism and liberalism’. Journal of European Public Policy 8 (1):24–42. doi:10.1080/13501760010018313.

- Lavenex, S. 2014. Justice and home affairs: Institutional change and policy continuity. In Policy-making in the European Union, ed. H. Wallace, M. A. Pollack, and A. R. Young, pp. 367–87. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lavenex, S., and F. Schimmelfennig. 2011. Democracy promotion in the EU’s neighbourhood: From leverage to governance? Democratization 18 (4):885–909. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.584730.

- Leerkes, A., M. Maliepaard, and M. van der Meer. 2022. Intergovernmental relations and return. Part 2: From paper to practice? EU-wide and bilateral return frameworks between EU+ and non-EU+ countries and their effects on enforced return. Memorandum 2022-02, Research and Knowledge Centre for the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security (WODC).

- Leerkes, A., and M. Van Houte. 2020. Beyond the deportation regime: Differential state interests and capacities in dealing with (non-) deportability in Europe. Citizenship Studies 24 (3):319–38. doi:10.1080/13621025.2020.1718349.

- Lutz, P. 2019. Variation in policy success: Radical right populism and migration policy. West European Politics 42 (3):517–44. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1504509.

- Maher, R. 2021. International relations theory and the future of European integration. International Studies Review 23 (1):89–114. doi:10.1093/isr/viaa010.

- Majcher, I., and T. Strik. 2021. Legislating without evidence: The recast of the EU return directive. European Journal of Migration and Law 23 (2):103–26. doi:10.1163/15718166-12340096.

- Mananashvili, S. 2017. ‘EU’s return policy: Mission accomplished in 2016? Reading between the lines of the latest EUROSTAT return Statistics’. https://www.icmpd.org/file/download/48172/file/EU%2527s%2520Return%2520Policy_%2520Mission%2520Accomplished%2520in%25202016_%2520Reading%2520between%2520the%2520lines%2520of%2520the%2520latest%2520EUROSTAT%2520retrurn%2520statistics.pdf.

- Manners, I. 2002. Normative power Europe: A contradiction in terms? Journal of Common Market Studies 40 (2):235–58. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.00353.

- Manners, I. 2006. Normative power reconsidered: Beyond the crossroads. Journal of European Public Policy 13 (2):182–99. doi:10.1080/13501760500451600.

- Marino, R., J. Schapendonk, and I. Lietaert. 2023. Translating Europe’s return migration regime to the Gambia: The incorporation of local CSOs. Geopolitics 28 (3):1033–56. doi:10.1080/14650045.2022.2050700.

- Miller, M. K., and M. E. Peters. 2020. Restraining the huddled masses: Migration policy and autocratic survival. British Journal of Political Science 50 (2):403–33. doi:10.1017/S0007123417000680.

- Mink, J. 2012. EU asylum law and human rights protection: Revisiting the principle of non-refoulement and the prohibition of torture and other forms of ill-treatment. European Journal of Migration and Law 14 (2):119–49. doi:10.1163/138836412X643317.

- Munck, G. L., and J. Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: Evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies 35 (1):5–34. doi:10.1177/001041400203500101.

- Natter, K. 2015. Revolution and political transition in Tunisia: A migration game changer? In’Migration information source country profiles. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/revolution-and-political-transition-tunisia-migration-game-changer.

- Natter, K. 2023. The Il/Liberal paradox: Conceptualising immigration policy trade-offs across the Democracy/Autocracy Divide’. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 50 (3):680–701. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2023.2269784.

- Natter, K., and H. Thiollet. 2022. Theorising migration politics: Do political regimes matter? Third World Quarterly 43 (7):1515–30. doi:10.1080/01436597.2022.2069093.

- Ozcurumez, S. 2021. The EU’s effectiveness in the eastern Mediterranean migration quandary: Challenges to building societal resilience. Democratization 28 (7):1302–18. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1918109.

- Paasche, E. 2014. Why Assisted Return Programmes Must Be Evaluated. PRIO Policy Brief 8, Peace Research Institute, Oslo. https://cdn.cloud.prio.org/files/236de7d6-36b0-4c75-b2b1-bcf2c31f6514/Paasche%20Erlend%20Why%20Assisted%20Return%20Programmes%20Must%20Be%20Evaluated%20PRIO%20Policy%20Brief%208-2014.pdf?inline=true.

- Pänke, J. 2019. Liberal empire, geopolitics and EU strategy: Norms and interests in European foreign policy making. Geopolitics 24 (1):100–23. doi:10.1080/14650045.2018.1528545.

- Parkes, R. 2016. People on the move - the new global (Dis)order. Paris: EU Institute for Security Studies. http://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/detail/article/people-on-the-move-the-new-global-disorder/.

- Peutz, N., and N. De Genova. 2010. Introduction. In The deportation regime: Sovereignty, space, and the freedom of movement, ed. N. De Genova and N. Peutz, pp. 1–29. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Reslow, N., and M. Vink. 2015. Three-level games in EU external migration policy: Negotiating mobility partnerships in West Africa. Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (4):857–74. doi:10.1111/jcms.12233.

- Rosenberger, S. 2018. Political Protest in Asylum and Deportation. An Introduction. In Protest Movements in Asylum and Deportation, ed. Rosenberger, S., V. Stern, and N. Merhaut. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 3–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-74696-8.

- Ruzza, C. 2018. Populism, migration, and xenophobia in Europe. In Routledge handbook of global populism, ed. C. de la Torre, pp. 201–16. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Rynning, S. 2011. Realism and the common security and defence policy. Journal of Common Market Studies 49 (1):23–42. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02127.x.

- Scheel, S. 2024. The deportation gap as a statistical chimera: How nonknowledge informs migration policies. Geopolitics, Online First: 1–23. doi:10.1080/14650045.2024.2368620.

- Schimmelfennig, F., and U. Sedelmeier. 2019. The europeanization of Eastern Europe: The external incentives Model revisited. Journal of European Public Policy 27 (6):814–33. doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1617333.

- Singelton, A. 2016. Migration and asylum data for policy-making in the European Union – The problem with numbers. CEPS (blog). https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/migration-and-asylum-data-policy-making-european-union-problem-numbers/.

- Slominski, P., and F. Trauner. 2021. Reforming me softly – How soft law has changed EU return policy since the migration crisis. West European Politics 44 (1):93–113. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1745500.

- Sökefeld, M. 2019. Nations rebound: German politics of deporting afghans. International Quarterly for Asian Studies 50 (1–2):91–118.

- Steiner, N. D. 2016. Comparing freedom house democracy scores to alternative indices and testing for political bias: Are US allies rated as more democratic by freedom house? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 18 (4):329–49. doi:10.1080/13876988.2013.877676.

- Stutz, P., and F. Trauner. 2022. The EU’s “return rate” with third countries: Why EU readmission agreements do not make much difference. International Migration 60 (3):154–72. doi:10.1111/imig.12901.

- Sylla, A., and S.M. Cold-Ravnkilde. 2022. En route to Europe? The anti-politics of deportation from North Africa to Mali. Geopolitics 27 (5):1390–409. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1995358.

- Tansel, C. B. 2018. Authoritarian neoliberalism and democratic backsliding in Turkey: Beyond the narratives of progress. South European Society & Politics 23 (2):197–217. doi:10.1080/13608746.2018.1479945.

- Tsourapas, G. 2018. The politics of migration in modern Egypt: Strategies for regime survival in autocracies. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108630313.

- Üstin, C. 2019. The impact of migration policies on the EU’s image as a value-driven normative Actor. Paper, Euromesco. https://www.iemed.org/publication/the-impact-of-migration-policies-on-the-eus-image-as-a-value-driven-normative-actor/.

- Van Houte, M. 2014. Returnees for change? Afghan return migrants’ identification with the conflict and their potential to be agents of change. Conflict, Security & Development 14 (5):565–91. doi:10.1080/14678802.2014.963392.

- Van Hüllen, V. 2019. Negotiating democracy with authoritarian regimes. EU democracy promotion in North Africa. Democratization 26 (5):869–88. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1593377.

- Vathi, Z., R. King, and B. Kalir. 2023. Editorial introduction: The shifting geopolitics of return migration and reintegration. Journal of International Migration & Integration 24 (2):369–85. doi:10.1007/s12134-022-00974-x.

- Warin, C., and Z. Zhekova. 2017. The joint way forward on migration issues between Afghanistan and the EU: EU external policy and the Recourse to non-binding law. Cambridge International Law Journal 6 (2):143–58. doi:10.4337/cilj.2017.02.03.

- Werenfels, I. 2018. Migration Strategist Morocco - Fortress Algeria. In Profiteers of migration? Authoritarian states in Africa and European migration management, ed. A. Koch, A. Weber, and I. Werenfels, pp. 22–33. Berlin: SWP Research Paper.

- Zanker, F., J. Altrogge, K. Arhin-Sam, and L. Jegen. 2019. Challenges in EU-African migration cooperation: West African perspectives on forced return. Policy Brief 2019/5, Mercator Dialogue on Asylum and Migration.

Annex

Figure A1. Global average freedom in the World aggregate scores, average EU return rates, and sum of orders to leave, 2008–2019.

x-axis: Freedom in the World, average aggregate score 2008-2019; y-axis: average EU Return Rate 2008-2019; bubble size: sum of total orders to leave per country 2008-2019.

Please note: The figure shows all the countries with at least 150 orders to leave for the whole period with the average mean for country return rates and FIW aggregate scores for the years 2008-2019. The horizontal line denotes the average mean of all countries included in the set, with a global average return rate of 34.9%. The vertical line denotes the global average aggregate FIW score for all countries in the set of 49.