ABSTRACT

In this article, we explore refugees’ countervisuality, an emancipatory protest against the visuality of border watchers. Focusing on the social media campaign ‘Now You See Me, Moria’, led by refugees in the Moria camp on the Greek island of Lesvos, we examine their digital rights claims against camp conditions and the EU-funded new Closed Controlled Access Centre. By analysing refugee-produced images and captions shared online, we unpack how refugees challenge the Greek authorities’ watching out for, of, and over refugees. Our findings indicate a power struggle wherein the authorities employ invisibilisation to shield the camp from external scrutiny while hypervisibilising and disciplining refugees inside the camp, proudly advertised and visibilised to the wider public as exemplary. We clarify how refugees strive to look back, be seen, and be recognised by a transnational audience in their just call for decriminalisation and humanisation, countering the authorities’ visuality regime. We conclude by discussing the significance of emancipating our ways of seeing refugees from an anti-democratic visuality regime imposed by state authorities.

Introduction

We open with an image, an insightful as well as troubling image, that may serve as an illustration of how Greece, on behalf of the European Union (EU), is hosting refugees.Footnote1 , taken anonymously by Deportation Monitoring Aegean, an independent monitoring group of activists and scholars, represents the newly inaugurated camp on the island of Samos. In 2019, the Greek authorities proudly announced the construction of new camps like this one on five Eastern Aegean islands, with 276 million Euros provided by the EU (AIDA Citation2023, 41). Not only Greece is proud of it, but also the French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin described the camp on Samos as a ‘European model’ for the reception of protection seekers (Kefalas, Savaricas, and Prousalis Citation2021). What is strikingly visible in the image are the three-metre-high double fences surrounding a highly structured, top-down planned area with bulky and identical containers used to warehouse people, quite literally. One could easily assume that this site is a lock-up for hardened criminals who, for safety reasons, are kept far away from the public. The visual message of the site is one of prison-like control, segregation, and isolation. It is clearly visible that the site was inserted all at once with no relationship to its green surroundings, with the intention to mark a border in space, and at a distance from the rest of society. Furthermore, the large camera in the picture reveals that someone is watching from an elevated vantage point but does not want to be seen. Who is watching and from where? Why are people seeking protection and refuge from violence and hardship treated as threats that Greece wishes to protect itself from through this security-obsessed and criminalising ‘panopticon’ (see Foucault Citation[1977] 1995)? Strikingly, in images like the one above, those who are being watched are conspicuously absent. What is their perspective on this fenced-in visuality?

Figure 1. Samos Closed Controlled Access Centre, 24 March 2022. Image source: Deportation Monitoring Aegean. https://dm-aegean.bordermonitoring.eu/2022/03/24/the-dystopia-in-form-of-a-camp-the-closed-controlled-access-centre-of-samos.

In this article, we explore in depth how the bordering practice of ‘watching’ (which we identify as humanitarian care, control, and surveillance) and the refugees’ ‘right to look back’ (Mirzoeff Citation2011) are juxtaposed in this supposedly model camp for refugees. We do this by confronting the visualisation regime of state authorities, using state-sponsored information and communication technologies (ICT), with the countervisualisation tactics of refugees using private ICT, mainly social media. In particular, we explore the digital rights claims recounted through the social media campaign ‘Now You See Me Moria (NYSMM)’ by refugees hosted in the Moria refugee camp, who will be transferred to the new Closed Controlled Access Centre (CCAC) constructed on the Greek island of Lesvos.

There is a rich and burgeoning literature that addresses refugees’ use of social media platforms (Dekker et al. Citation2018; Leurs and Ponzanesi Citation2018; Marlowe Citation2019; Noori Citation2022; Scheibe and Zimmer Citation2022; Şanlıer Yüksel Citation2022), particularly as a space for political action (Georgiou Citation2018; Isin and Ruppert Citation2020). Strikingly, however, there is a dearth of literature analysing the social media produced and shared by refugees themselves, apart from the work of a handful of scholars (Bayramoğlu Citation2023; Creta Citation2021; Leurs Citation2017). In this article, building on these studies, we juxtapose the perspectives of states on watching (as visuality) and refugees on looking back (countervisuality). We conduct a multimodal analysis of visual imagery and accompanying texts that self-represent refugees’ struggles with and against state-centric visuality. Rather than focusing solely on images or on texts disseminated via digital media, our multimodal approach enables us to concentrate on both. Finally, by reflexively considering our own ‘ways of seeing’ refugees’ countervisuality (see Berger Citation1972), we explore the ways in which spectators make sense of refugees’ digital rights claims.Footnote2 While recognising the potential for overlooking certain aspects as an ‘outsider’ or involuntarily reinforcing existing power dynamics, our study aims to shed light on the hosting conditions shaping refugees’ lives and the challenges they face. By providing insights into the confrontational forms of visuality and digital rights, and focusing on refugee-produced digital content and everyday spectatorship, we aim to contribute to the multidisciplinary scholarship on bordering, migration management, and refugee struggles, as well as to advocacy and policymaking, with implications for a wider geography where the politics of visualisation is contested. With this in mind, we formulate the following questions: How, why, and by whom is ‘watching’ constructed as a bordering practice in the Lesvos border camp? What digital rights claims (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020) do refugees involved in the social media campaign ‘Now You See Me Moria (NYSMM)’ raise, and in what ways do they challenge the border watch in Lesvos?

In what follows, we first further elucidate the contextual framework of the article. Then, we present the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of the power interplay between watching and looking back (and being seen) through juxtaposing the confrontational uses of ICT by states and refugees. After this, we introduce and analyse the NYSMM campaign and the posts shared on its Instagram account. We triangulate this inquiry with a semi-structured interview we conducted in April 2023 with Noemí,Footnote3 NYSMM’s co-founder, as well as with legal and policy documents, reports of international organisations and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) concerning the Lesvos CCAC. We conclude with an analysis of the impact of the power struggle between the state’s watching out for, of, and over refugees and refugees’ struggles to look back, be seen, and be recognised by a transnational spectatorship in their just call for decriminalisation and humanisation.

EU’s Watchtower in Lesvos

Since the so-called ‘migrant crisis’ in 2015, followed by a brief period of a relatively hospitable policy, notably implemented by Germany, a leading EU Member State, that welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees (Tazzioli Citation2020, 37), we have witnessed the intensification of a severely hostile and criminalising border policy within and by the EU. This has been accompanied by a sharp rise of the far right in Europe (Molnar Citation2020, 36). A case in point of the heightened undesirability and hostility in the hosting of refugees – or what Derrida (Citation2000) termed ‘hostipitality’ – is the transformation of the refugee camps on five Greek islands into ‘hotspots’ in 2015 (Council of the EU Citation2015a, 2015b), further enforced by the launch of the EU – Türkiye Statement of 18 March 2016,Footnote4 and then into ‘closed and controlled access centres’ (CCACs) over 2021 and 2022 (European Commission Citation2020b, AIDA Citation2023, 39; iHaveRights Citation2023b).

In the words of the memorandum of understanding on the establishment of a CCAC in Lesvos, agreed, inter alia, between the European Commission and Greece in December 2020: ‘[t]hose arriving on the [Lesvos] island will undergo full reception and identification procedures, including screening upon arrival … , identity checks, security checks, finger printing in the Eurodac database, registration, health and vulnerability assessment, … and access to the asylum procedure (lodging)’ (European Commission Citation2020b, 5–6). Moreover, ‘[t]he conditions for the reception of asylum seekers, including possible detention after individual assessment, will be ensured in line with the EU law … , notably ensuring adequate sanitation, catering and/or availability of cooking facilities, information provision and counselling, clothing and non-food items, and common areas’ (European Commission Citation2020b, 6, emphasis added). The creation of these, what we would call, ‘border-ceptions’, borders inside borders, demonstrates the vigorous attempts of the EU and its Member States to not only impose full control over the mobility of undesired refugees, but also exceptionalise, dislocate, immobilise, warehouse, and guard them. The border-ception, also referred to as ‘post-border’ or ‘the border camp’ as described by van Houtum and Bueno Lacy (Citation2020), has now evolved into an EU ‘reception’ model imposed on people fleeing hardships and violence, particularly from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, and labelled as ‘irregular migrants’. In fact, progressively ‘[s]ince 2016, the European Union has been pushing hard to externalise its migration policies by moving asylum seekers out of public sight into remote, inaccessible spaces at its borders and beyond, to evade its human rights obligations’ (iHaveRights Citation2023b). Subsequently, the Eastern Aegean islands, mainly Lesvos, have become a primary test ground for the EU’s exceptionalisation tactics, ultimately resulting in the creation of CCACs on the islands. These bordering tactics do not apply to all refugees, however. In the eyes of the EU, some refugees are apparently more equal than others, depending on their country of origin. For instance, Ukrainian refugees who have fled the Russian invasion since February 2022 were given a warm and safe welcome, including quick integration into the labour market and education system (see Bueno Lacy and van Houtum Citation2022; European Parliament Citation2022; Osso Citation2022). They were framed as ‘European’ or belonging to ‘our region’ (Bueno Lacy and van Houtum Citation2022).

It is hard to deny that despite the ostensible improvement of accommodation conditions from makeshift tents of the former Moria camp to containers equipped with actual beds, showers, and basic services, the main structures designed for all ‘other’ refugees, largely fleeing war-inflicted countries like Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and Somalia, in the new CCAC resemble a criminalising and dehumanising prison (see Close Citation2022; AIDA Citation2023, 19). With the ‘integrated digital surveillance system, including CCTV [closed-circuit television], video monitors, patrolling drones, perimeter violation alarms, control gates and loudspeakers to broadcast announcements’, 24/7 monitoring by the police and private security guards, and surrounded by a double NATO-type security fence, the CCACs underline the discriminatory and carceral features of the hosting of non-Ukrainian refugees (Close Citation2022; see also Hellenic Ministry of Migration and Asylum Citation2021). This is further emphasised by the highly secured entrance to the camp. Access to and from the sites is limited ‘between 8 am and 8 pm through a turnstile magnetic gate with a two-factor access control requiring both an electronic card and fingerprinting’ (Close Citation2022). CCAC inhabitants have to undergo searches with x-rays and metal detector devices whenever they enter or exit the camp or transit to another area of the camp (iHaveRights Citation2023a, 21–22).

This securitisation at the entrance has reduced the visibility of refugees to the outside world and augmented public unawareness for potential human rights abuses in the centre. To wit, already in 2020, the plans for the construction of CCACs brought new access restrictions against media reporters, journalists, activists, and NGOs ‘from publicly sharing any information related to the operations or residents of refugee camps’ in Greece, such as restrictions on taking photographs or videos of CCACs (Euro-Med Citation2020; European Parliament Citation2023, 26–28). It is in this context of invisibilising the camp conditions and, as Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 8) wrote, ‘the policing of visuality’ both inside and outside the camp by the Greek authorities that NYSMM emerged: over 600 inhabitants of Moria attempted to visually crack open in cyberspace the black box that the Greek camps have become by reporting on the camp conditions from the inside.

On the Art of Watching vs. Looking Back

In the last decades, legal, critical border, migration, and security scholarships have focused on different uses of ICT and visual technologies in border governance and the implications of these tools for people on the move. Most scholars adopted a state-centric approach, focusing on how these technologies increasingly expand sovereign spaces of control over targeted migrant and refugee populations (see Jones and Johnson Citation2016; Koca Citation2022; Leese, Noori, and Scheel Citation2022; Loukinas Citation2022). In addition, there is a growing scholarly emphasis on the perspectives of migrants and refugees themselves. Addressing the digital technologies used at borders and the images of refugees in digital media, Chouliaraki and Georgiou (Citation2022) for instance, investigated digital borders as a site of power struggle between states and the media on the one side and refugees on the other. Along these lines, Nedelcu and Soysüren (Citation2022) proposed an analytical approach of ‘empowerment-control nexus’, contrasting the use of ICT by states for control with its use by refugees and migrants for empowerment (see also Koca Citation2022; Noori Citation2022; Şanlıer Yüksel, Citation2022). By claiming the need to ‘push the analysis beyond the “empowerment-control nexus”’, Tazzioli (Citation2023, 5) proposed a shift from the state gaze on migration and technology to ‘seeing (technology) like a migrant’ to better grasp the effects of these technologies on migrants and migrants’ struggles.

In what follows, we build on these insights by focusing on the bordering within borders, described as ‘a crucial site of surveillance, where identities, mobilities, and narratives are examined by agents of the state’ (Amoore, Marmura, and Salter Citation2008, 97), the fissures of which are often contested by refugees. We dissect how the confrontational interplay between watching and looking back manifests a power struggle over visuality and in/visibility in Lesvos.

On the Watching Out, Of, and Over

We postulate that the EU and Greek border guard practices of ‘watching’ certain refugees at the hotspots, particularly in Lesvos, materialise in three forms: (1) watching out through criminalising, pushing back, allowing refugees to perish, and even killing them (see Tazzioli Citation2020, 48; van Houtum and Bueno Lacy Citation2020), (2) followed by securitisation and monopolisation of the watching of refugees who nonetheless reached the shore, behind closed doors, and (3) resulting in paternalistic, subjectifying watching over people seeking protection, eroding their agency by sequestering and externalising the care of their basic necessities, and silencing of their voice. Underlying these practices is the dominant discourse in EUrope that indecisively portrays certain refugees as victims, villains, or invaders, revolving around ensuring the EU’s and national security, combating ‘irregular migration’ and migrant smuggling, and saving lives at sea (see European Commission Citation2020a; on European media, see Leurs Citation2017; Georgiou Citation2018). The prevailing discourse, thus, dehumanises (Chouliaraki and Georgiou Citation2022, 15–18) and demonises refugees, particularly those from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, with racialised and humanitarian undertones, while further undermining refugees’ agency (Bayramoğlu Citation2023, 596).

Refugees, visualised as victims, villains, invaders, and ‘illegals’ ‘rescued’ at sea, are those whom the EU and Greek authorities watch out for and often, unlawfully, aim to deter and push back. Those who do arrive are segregated from the rest of the population and contained in camps. Next, the refugees are screened by the Greek authorities: a watching of refugees. They are watched through identification and registration procedures (Pollozek and Passoth Citation2019), including health and security screenings and pre-entry screenings, distinguishing the ‘returnable’, irregular migrants from those who are eligible to claim asylum (see European Council Citation2018, para. 6; European Commission Citation2020a). Once hosted in the CCAC, these refugees are watched as in a Foucauldian ‘panopticon’ (Foucault Citation[1977] 1995). They are monitored 24/7 ‘without ever seeing’ their border watchers, ‘notably from elevated observation posts making [the watchers’] presence ubiquitous’, and through diverse ICT (see Foucault Citation[1977] 1995, 202; Close Citation2022). The authorities have invested considerable time, energy, and money to incorporating a wide range of screening and monitoring technology along with their sentinels into what supposed to be ‘hosting’ facilities for refugees – people who, paradoxically, mainly have no intention other than to travel away from hardship, conflicts, and authoritarianism.

Lastly, the border watchers have also appropriated, in a totalitarian manner, the watching over. The ‘care’ for refugees who seek protection is turned into a paternalistic, agency-eroding manner by the Greek authorities and border guards, further exemplifying the above-mentioned ‘hostipitality’ (Derrida Citation2000). Akin to dangerous prisoners, every aspect of refugees’ life (food, sleeping, playing) is regulated in an undemocratic, top-down fashion. What is more, the border watchers are careful to keep the refugees out of the sight of EUropean citizens. Therefore, refugees are not only compelled to remain invisible and clandestine, but they are also silenced, rendered passive, helpless, and unable to articulate their agony and struggles.

Seen in this way, watching emerges as a bordering practice that goes beyond the wider public perception of borders merely as the visible ends of states, in the form of border guards, walls, fences, or barbed wires (Osso Citation2023; van Houtum Citation2021, Citation2024). Instead, it should be understood as a machinery of filtering, sorting, screening, guarding, and invisibilising undesired bodies and populations.

On Refugees’ Countervisuality

Refugee resistance against discriminatory border regimes has gained bourgeoning consideration in migration, citizenship, and border studies. Conventional protests organised by refugees under detention or awaiting status determination have created various local impacts and also attracted global attention, including silent protests, sit-in protests (Moulin and Nyers Citation2007), and demonstrations involving extreme acts of self-inflicted bodily harms, such as sewing of lips (Nyers Citation2003) and hunger strikes (Fiske Citation2016).

The proliferation of ICT has spurred new forms of refugee political action and activism, which caught the attention of a novel and already considerable body of literature (Georgiou Citation2018; Isin and Ruppert Citation2020), some of which concentrated on refugee-produced social media (Bayramoğlu Citation2023; Creta Citation2021; Leurs Citation2017). An important contribution to this field was made by Diminescu (Citation2008), who introduced the concept of ‘connected migrants’. Diminescu discussed how ICT facilitates new tactics for mobility, integration, and survival for migrants. Following her line of work, a growing amount of research has focused on the use of social media by connected migrants (Leurs and Ponzanesi Citation2018; Marlowe Citation2019), how social media affected or facilitated migrant decision-making about cross-border movement (Dekker et al. Citation2018; Noori Citation2022), and migrants’ survival strategies and integration in host countries (Scheibe and Zimmer Citation2022; Şanlıer Yüksel Citation2022). Focusing on the social media content shared by young Syrian refugees living in the Netherlands, Leurs (Citation2017) examined how digital practices can invoke human rights and address power relations. In a similar vein, Creta (Citation2021) explored the comments and posts shared by refugees on UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) Libya’s Facebook page to investigate how digital media offered a space of appearance for people on the move in Libya. Studying ‘the political significance’ of smartphone videos shared online by migrants crossing EUropean borders, Bayramoğlu (Citation2023) addressed how these videos created a ‘countervisuality’ of border crossing, challenging Eurocentric visualisations in media and politics. Despite immense contribution to our knowledge and understanding of refugee-produced social media by these and other similar studies, little is known yet, however, about how refugees ‘look back’ at and confront the ICT-induced watching practices in Lesvos through private ICT (social media), and what these refugees demand from their online spectators.

Such is important as reciprocating refugees’ right to look back and be seen on social media shifts the focus away from the hegemony of state’s visuality, to use Tazzioli’s (Citation2023, 5) words, ‘to the struggles [refugees] engage in over technological hurdles’. It enables emancipating our ways of seeing refugees from an anti-democratic visuality regime imposed by state authorities. In The Right to Look, Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 1–4) defined ‘the right to look’ as the claim to autonomy from authority, a political subjectivity, and collectivity, thus refusing to be classified, segregated, and controlled. This right is what Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 1–5) termed as countervisuality: ‘[c]ountervisuality is the assertion of the right to look, challenging the law that sustains visuality’s authority in order to justify its own sense of “right”’ (Mirzoeff Citation2011, 25). Countervisuality, thus, counteracts the visuality of what we are able, allowed, or made to see or unsee (see Rose Citation2001, 6), especially as portrayed by the media and state authorities. In our view, by producing a new form of visuality on social media, refugees endeavour to enact spaces of appearance with a transnational spectatorship to challenge the state’s visuality regime and, to recall Rancière (Citation2009, 14), ‘make [their spectators] see’ refugees’ struggles. Thus, the digital practices of refugees affirm their autonomy and their agency. By ‘agency’, we refer to the capability to navigate one’s life trajectories according to one’s own terms and decisions, which may involve organised or spontaneous political action against structural constraints.

In this context, Hannah Arendt’s (Citation1998) account of ‘space of appearance’ and the Greek polis is worth recalling. By claiming ‘[w]herever you go, you will be a polis’, Arendt (Citation1998, 198) explicated the ubiquity of ‘space of appearance’, a space where one can divulge their unique self by acting and speaking in concert with others. Moreover, we would add, by making digital rights claims on social media platforms, refugees can create a (cyber-)space of appearance, even when they are contained in exclusionary spaces like Moria. Certainly, this, also has its limitations. Not every refugee has access to internet or possesses a smartphone (Creta Citation2021, 377), and the authorities may trace what refugees share on social media (Leurs Citation2017, 692). Nevertheless, camp refugees may find tactics for connecting to the worldFootnote5 and producing countervisuality, to look back at the border camp guards. A powerful example is the ‘Now You See Me Moria’ (NYSMM) movement, to which we turn next.

Now You ‘See’ Me?

In an attempt to create a cyberspace of appearance by claiming the right to look back, ‘Now You See Me Moria’ started and has grown as a digital social movement among Moria refugees. In this section, we discuss the context and outline the methodology we used to study this movement.

The Story

In recent years, we have witnessed a steady rise in hashtagsFootnote6 on Instagram by ‘Now You See Me Moria’ (NYSMM), protesting the conditions of the infamous Moria refugee camp, such as #moriacamp, #nochildinaprison, receiving hundreds of likes, comments, and interactions. The images under these hashtags mostly represented makeshift tents and containers in muddy and unsanitary surroundings. Intrigued by these posts, we investigated further and discovered that NYSMM was launched in 2020 by two people who came together online: Noemí, a Spanish photographer and photo editor based in the Netherlands, and Amir, a young Afghan refugee who had lived in Moria for two years. They began communicating when Noemí saw a photograph that Amir shared on Facebook, depicting the situation in Moria during the COVID-19 pandemic. The two decided to share images from Moria and Lesvos. Their campaign gradually grew, first with Qutaiba from Syria and Ali from Afghanistan,Footnote7 and then with more Moria inhabitants joining in (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023). Since 2020, over 4,600 posts (display images (screenshots), photographs, videos) and countless ‘Insta stories’ have been shared on NYSMM’s Instagram account, which has gained over 41,100 followers.Footnote8

Over 600 refugees have now joined this campaign, sharing images and stories without any specific prompts or assignments (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023). There is no centralised leadership; every refugee at NYSMM is a leader and has their own agency. Most photographs and videos are taken clandestinely with smartphones and emerge as a self-representation of refugees’ everyday life. Through collaborating with ‘outsiders’, such as artists, graphic designers, activists, researchers, students, lawyers, NGOs, and human rights advocates, NYSMM is present not only in cyberspace, but also in public spaces. To wit, together with these ‘outsiders’, NYSMM organised over 30 photograph and poster exhibitions in museums and cultural spaces (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023), including in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands between October 2021 and March 2022,Footnote9 in Düsseldorf, Germany in April 2023,Footnote10 and elsewhere in Europe, as well as in some refugees’ home countries, such as in Aleppo, Syria. The movement also created ‘an “action book” that functions as a ready-made protest object’ (see note 9) and has a continuous call where anyone can create posters, print, and make them visible in public spaces.

Regarding Refugees’ Right to Look

By reciprocating the right of refugees at NYSMM to look back, we seek to gain a deeper understanding of refugees’ struggles in Lesvos, as recounted on Instagram. Because Instagram is a popular social media platform, which allows its users to share multimodal content, including photographs, audiovisual media, written language (as screenshots), diagrams, emojis, and so forth alongside multilingual captions and comments, and potentially reaches a very large audience (Bateman, Wildfeuer, and Hiippala Citation2017), we consider it a very useful case for our social media analysis.

After an initial scanning of the posts on NYSMM’s Instagram account since the first one shared on 20 August 2020, right before the fire that destroyed the former Moria camp, we realised that many of the posts dealt with issues like camp conditions, calls to action, and help for advocacy and resettlement. The posts publicised since 2021 focused more on protesting the new Lesvos CCAC, the topic of our concern here. Addressing the content shared between October 2022 and May 2023 (and a few from 2020 and 2021 that addressed our research themes), we sampled a total of 50 posts featuring photographs and videos from Lesvos, along with their accompanying captions.Footnote11

Inspired by a multi-site (Rose Citation2001) and multimodal (Bateman, Wildfeuer, and Hiippala Citation2017; Jewitt Citation2013) qualitative content analysis, we developed six coding themes. These themes were formulated drawing on extensive critical scholarship on bordering, migrant agency, and rights claims to analyse the images: (1) experiences and struggles of refugees in the camp, such as containment, lack of decision making, time, waiting, call to action, migration policy; (2) emotions, such as hopelessness, fear, uncertainty, stranded; (3) visual elements present (or absent) in the image, such as objects and subjects (e.g., everyday life, camp, belongings, no people, children, seacoast), perspectives and composition (such as zoomed in/out, tilted angle, or blurry, which we interpreted as that the image was taken covertly, instantaneously, and/or from afar); (4) rights claims raised and endorsed by refugees, such as loss of home, inability to find home, free movement, free speech, adequate food, decent conditions, and the way they are raised, such as digitally and/or in practice; (5) visible and invisible borders, such as digital (e.g., censorship), legal (e.g., encampment, deportation), physical (e.g., barbed wires, camp structures), and their implications for refugees, such as oppression, restriction, immobilisation; (6) overall message and common themes (which we revisited multiple times to better respond to our research questions). To learn further about the context of the images, bearing in mind what Rose (Citation2001, 15) has argued, ‘[t]he seeing of an image … always takes place in a particular social context that mediates its impact’, we triangulated our inquiry with the semi-structured interview we conducted with Noemí in April 2023, legal and policy documents, and reports of international organisations and NGOs concerning the Lesvos CCAC.Footnote12

In Regarding the Pain of Others, Sontag (Citation2003) cautioned about the ‘voyeurism’ trap, meaning that showing the images of suffering people can arouse empathy, but also possibly violates them, as it turns these people into objects that can be symbolically possessed and potentially desensitises viewers to the real pain experienced by others. In our case, this could be translated to the potentially desensitising effects of imagery showing the human rights abuses inflicted on refugees that make the spectators compelled to look at the refugees who suffered merely as symbolic objects, without doing anything. This is an important and powerful argument. For this reason, Butler (Citation2005, 823–825) argued that ‘a photograph can incite and motivate its viewers to change a point of view or to assume a new course of action’, and, that it is, therefore, of crucial importance ‘to transform that affect [towards photographs] into effective political action’. Taking this critique seriously, and bearing in mind that the images on NYSMM’s Instagram account had their own effects (see Rose Citation2001, 10) that could evoke sympathy and pity (see Bayramoğlu Citation2023), we endeavoured to see and represent the creators of these images and the posed subjects (refugees) not merely as pitiful, suffering victims but people with agency who resist border violence. Moreover, because refugees held the camera themselves, we believe the gap between the photographer and the photographed was also minimised unlike in standard journalistic or humanitarian imagery. At NYSMM, refugees reported the stories of individuals like themselves in the images they captured, complemented by impactful captions.

Looking Back at the Lesvos Watchtower

With our analysis, we gained important insights into refugees’ everyday life in Moria where refugees covertly contest the Greek practices of watching out for, of, and over certain refugee populations. We found that there were at least four common demands emerging from the images and captions shared on NYSMM’s Instagram page, which we interpreted as refugees’ spatiotemporal, digital rights claims raised to a transnational spectatorship: (1) Demanding control of lives while resisting the erosion of migrant agency; (2) Staying invisible while resisting control and surveillance; (3) Countering the monopolised visuality regime by enacting visibility for refugees’ rights; and (4) Demanding recognition for struggles before a transnational spectatorship. We will elaborate on these rights claims in the following sections.

Demanding Control of Lives While Resisting the Erosion of Migrant Agency

Refugees sharing content on NYSMM’s Instagram account often demand control over their lives while resisting the agency-eroding seizure of everyday care of refugee needs by the EU and Greek authorities and private aid agencies in Lesvos. Refugees challenge such watching over by proposing temporary, alternative ways of governance in the quasi-permanent life of the camp, for instance, by providing food vouchers, thus enhancing their autonomy.

In an Instagram post, one of the refugees expressed:

When you arrive here, time stops. Suddenly you don’t have any choice. You eat what they give you. You wait in line for the food. You just have with yourself your memories from home. You wear clothes that doesn’t belong to you. Anything anymore belongs to you not even your dreams because [no one] can dream when you live in hell. ()

Figure 2. An image posted on ‘Now You See Me Moria’ Instagram page, 1 April 2023. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/CqgJF_gohGv.

We understand the caption above as illustrating refugees’ lack of decision-making power and their loss of autonomy, stemming from prolonged confinement, elongated waiting, and enforced immobility (being stranded) in Lesvos. The caption, which we interpret as illustrating how the ‘spatiotemporal suspension’ of refugee lives becomes prolonged in the camp (Agamben Citation1998, 37), accompanies a rather paradoxical photograph, devoid of any visible humans. Instead, the image depicts the permanence of ‘temporary’ camp structures: everyday items used by refugees, such as bikes for transportation and baby strollers symbolising the presence (and perhaps, birth) of children in the squalid camp. These structures include the ‘isoboxes’ and tents provided by UNHCR for shelter, covered with makeshift tarpaulins ().Footnote13 As Noemí expressed, and we also recognised in some posts on Instagram, refugees also frequently express frustration about ‘waiting for everything’ (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023), including enduring waits of two, three hours just to receive insufficient and low-quality food. The inability to choose what and how much to eat illustrates that ‘Greek and European authorities have full control over refugees’ lives. They even control what [refugees] can eat or not’.Footnote14 This highlights how the EU and Greek authorities view and treat certain refugees as mere bodies to watch over, as destitute victims reliant on humanitarian care. This comprehensive ‘watching over’ approach denies refugees the opportunity, space, and time to sustain their own lives independently.

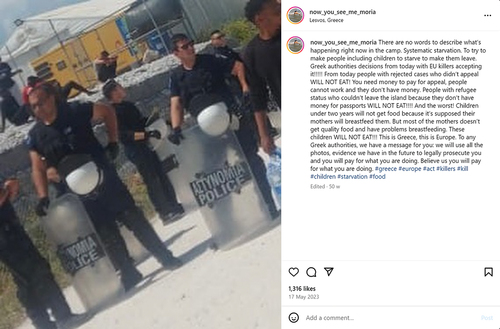

In May 2023, refugees reported that the Greek authorities were cutting off food supplies for those whose asylum cases were rejected, reducing their meals from three times a day to just one meal (; see also AIDA Citation2023, 170). The caption reporting this news accompanies a photograph showing Greek police holding riot shields and standing firm, watching over and out for camp refugees who may seek to protest against the authorities’ recent decision (). The tilted composition and low quality of the image tells us that the person who took this image did so very quickly and secretly, likely zooming in from a distance. The person who took this image ‘looked back’ at the police to challenge the decision that sequesters refugees’ right to food. This ‘sequestration’ of refugee lives, as Tazzioli (Citation2020, 47) contends, seeks to subdue refugees and debilitate their resistance. Through first making refugees dependent on state’s aid and care, deploying endless waiting and procrastination as a deterrent (time as a border), and then forcing them to leave the Greek territory and rescind the care, the Greek authorities effectively strip refugees of power, rights, and opportunities to independently access resources. This mode of subjection, or ‘compassionate repression’ as Fassin (Citation2005) put it, in Lesvos ‘work[s] by depriving lives without killing them, by wearing out and exhausting migrants, by hampering the building up of spaces of life and by stealing migrants’ time’ (Tazzioli Citation2020, 47). As we see it, without completely immobilising or blocking refugee mobility, the EU and Greek authorities, in effect, deter, subjugate, and psychologically induce refugees ‘irregularly’ arriving at the EU, suggesting to them that they are undeserving protection and building a life on EU soil. Perplexingly, all of this is done under the guise of ‘hospitality’ of Greece and the EU, who present themselves to the outside world as benevolent ‘saviours’ receiving refugees with open arms, which appears as ‘episodes of compassion toward refugees … eluding the common law of their repression’ (Fassin Citation2005, 375).

Figure 3. An image posted on ‘Now You See Me Moria’ Instagram page, 17 May 2023. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/CsWoWItIfYx.

To overcome some of these challenges posed by humanitarian watching over in Lesvos, refugees find noteworthy strategies. In many posts, they contest the authorities’ visuality that sequesters refugees’ autonomy, sharing images that visibilise the sorts of packaged, unwholesome, unnourishing food delivered to them (see note 14). Moreover, together with the ‘outsiders’ they collaborate across Europe, refugees produce alternative ways of governance by distributing monthly food vouchers generated from online sales of t-shirts and sweatshirts to camp residents (see note 14).Footnote15 In doing so, refugees occasionally decide for themselves what to eat, thereby asserting their claims to adequate and quality food. Such tactics ostensibly materialise in reaction to inedible and inadequate food delivered through aid agencies and the Greek government. Most importantly, these tactics reveal the refugees’ intention to reclaim control of their lives in Lesvos, asserting autonomy in response to authorities’ watching over and agency-restricting tactics. They also represent a countervisuality that emphasises agency and ability, countering the portrayal of refugees as helpless victims in need of humanitarian aid and care.

Staying Invisible While Resisting Control and Surveillance

Refugees’ posts on NYSMM’s Instagram page further often reflect their resistance against control and surveillance of Greek authorities, challenging the far-reaching watching of refugees in Lesvos. As we detail below, refugees seek to stay invisible in public spaces against their ‘enforced visibility’ (or ‘hypervisibility’, to cite Mirzoeff Citation2011, 231) due to comprehensive surveillance technologies. Worryingly, this self-invisibilisation is, in effect, the continuation of their clandestine and invisible journeys from home to seek safety and protection in Europe, which implies the continuity of their lack of security and autonomy. From the refugee-produced content, we found that with this in mind, refugees propose long-term alternatives for the hosting of refugees, such as stopping the construction of the Lesvos CCAC. This would help refugees no longer feel the need to be invisible or to expose to the outside world the dehumanising conditions of refugee camps.

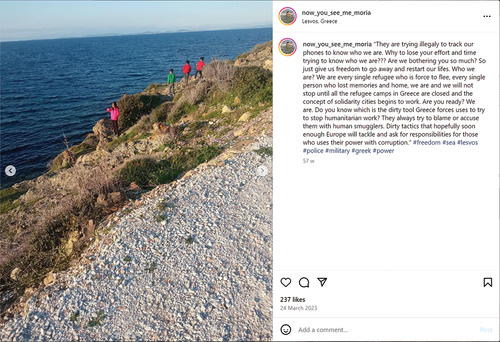

As some of the posts on NYSMM Instagram page reveal,Footnote16 many refugees inhabiting Moria joined peaceful demonstrations in Lesvos before and right after the former Moria camp burned down in September 2020. Protesting their transfer to the new camp in Kara Tepe (Mavrovouni) with equally squalid conditions, refugees in Lesvos engaged in hunger strikes for five to six days, slept on and blocked roads (see note 16). To curb the demonstrations, Noemí explained, the Greek authorities threatened the refugees with not processing their asylum claims and their deportation (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023; see also Deportation Monitoring Aegean Citation2019). Faced with this blackmail of the authorities, refugees felt compelled to bring their demonstrations in public spaces to an end. The refugees then continued their resistance in more scattered, subtle, and clandestine ways using social media, such as via Instagram posts. To wit, the images refugees share on Instagram often depict refugees’ everyday life, intentionally avoiding any human presence to protect refugees’ identities (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023). In contrast, the captions contain more overt political statements (see ). Even when the images depict people, especially those representing refugees and refugee children, refugees at NYSMM are keen to protect people’s identities. Refugees conceal the faces of posed people using digital techniques, such as painting over the faces (), or take the photographs from a distance where people are vaguely visible, or from behind ().

Figure 4. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 24 March 2023. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/CqLgNRAo7du.

Remaining invisible themselves, while raising a set of demands online, refugees at NYSMM challenge the constant watching of refugees by the authorities. In many Instagram posts, they criticise the physical camp structures in which the Greek authorities attempt to relentlessly monitor and control refugees, such as in Moria and the new Lesvos CCAC. Refugees express that they wish to regain their freedom and continue their lives that is consciously being suspended in Moria (see ). Particularly in the posts shared from 2021 onwards, refugees demand to stop the construction of the CCAC. They enunciated, ‘[they] will not stop until all the refugee camps in Greece are closed’ () or ‘until no child is living in miserable European refugee camps’ (). As can be observed from the images they publicised, children are frequently the main figures (see ), highlighting that they are among those whose lives are most disrupted in Lesvos. Using #nochildinaprison, refugees oppose the detention of both children with families and unaccompanied children, calling for action to halt the new CCAC. Instead, they advocate for the creation of places where they feel safe and have the decision-making power and agency to self-sustain their lives. Together with the ‘outsiders’, they insist on the creation of safe, self-autonomous, and non-segregated hosting places in Greece () or elsewhere in Europe (; Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023).

Figure 5. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 3 November 2022. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ckg2gTaIwn_.

Finally, refugees posting on NYSMM’s Instagram page confront the ICT-induced surveillance practices of Greek authorities, both in Moria and the new CCAC, which is constructed in a much more remote and inaccessible area (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023). With their clandestine and subtle resistance, refugees ‘look back’ at these practices by documenting how the Greek authorities attempt to censor what refugees share on social media: ‘The more you make … our life miserable, the more we will fight against this injustice. They are trying to track our phones. That’s illegal, unconstitutional and against everything!’Footnote17 Moreover, they voice their rightful objection against the watching of refugees in the new CCAC, or as they name it, in ‘high surveillance/fingerprints prisons’ (). Several rights organisations consider these new camps as a ‘de facto detention’ centre (AIDA Citation2023, 41–42; iHaveRights Citation2023a). The refugees’ actions make it clear that although ‘hostipitable’ (Derrida Citation2000) reception conditions in Greece have been challenged many times at supranational courts, Greek authorities, on behalf of the EU, have continued transforming the notorious camps into even more deplorable spaces (ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights) Citation2011, Citation2023; see also iHaveRights Citation2023b).

Countering the Monopolised Visuality Regime by Enacting Visibility for Refugees’ Rights

The posts refugees shared on NYSMM’s Instagram page also commonly reflect refugees’ struggles for the human rights denied to them in Lesvos. The human rights abuses by the EU and Greek authorities may be seen as a deterrent against refugees who aspire to flee to the EU. By enacting a cyberspace of appearance to claim their rights as the subject of rights inscribed in international treaties and calling for the Greek authorities’ accountability, refugees debunk the monopolisation of the authorities’ visuality that some refugees are undeserving of these rights.

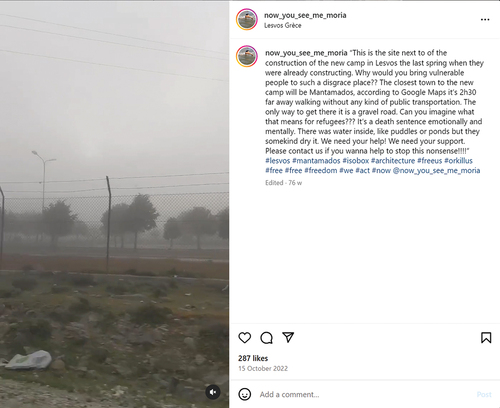

While refugees remain increasingly invisible to cover their identities and bodies from the Greek police and authorities, they demand visibility for the denial of their human rights by providing clandestine evidence from inside Moria and the new CCAC. For instance, refugees reported a video near the CCAC construction site in Vastria where barbed wired fences next to the site are clearly visible, demonstrating that nobody from outside is allowed to get close to or enter the site (). They also created a countervisuality by sharing the precise location of the Lesvos CCAC on Instagram, posting a screenshot of a pin dropped on Google Maps.Footnote18 As refugees revealed, the CCAC is built in a secluded place far away from public transport and about 2 hours and 30 minutes away by foot from the nearest town, Mantamados () and 30 kilometres from Mytilene, the centre of Lesvos (AIDA Citation2023, 40). Moreover, as we addressed, entries to and exits from the new camp is strictly restricted, making the communication of refugees with the outside world and the monitoring of their conditions and human rights increasingly challenging.

Figure 6. A video posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 15 October 2022. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cjv13wpozo9.

By summoning their rights by way of Instagram posts, refugees create ‘dissensus’ and enact themselves as autonomous political subjects (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 155; Rancière Citation2004). In this sense, refugees’ countervisuality transpires as ‘the dissensus with visuality, … a dispute over what is visible’ (Mirzoeff Citation2011, 24). With dissensus, as Isin and Ruppert (Citation2020, 156) argued, refugees as political subjects may invoke ‘the imaginary, performative, and legality of rights all at once’. Refugees ‘make digital rights claims by their acts through the Internet (performativity) … in or by what they say about those rights in declarations, bills, charters, and manifestos (imaginary) … and call on authorities for the inscription of those rights (legality)’ (Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 12). By asserting themselves as the subject of the rights they are denied in Lesvos through their posts on NYSMM’s Instagram page, refugees perform the rights ‘that they do not have and the rights that they should have’ (see Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 156; also Rancière Citation2004, 305–306). Thus, they are claiming their ‘right to have rights’ (Arendt Citation1973).

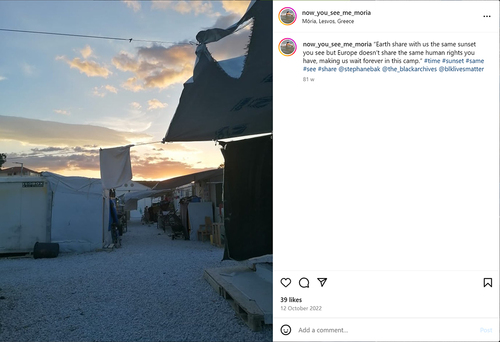

As political subjects, refugees involved in the NYSMM movement summon the imaginary, performative, and legality of their rights on Instagram in various ways. For utmost visibility, the captions on Instagram are written in English. Clearly, they address their demands to a transnational audience: EU institutions, EU citizens, NGOs, researchers, lawyers, the international media, etc (see Moulin and Nyers Citation2007, 361). Moreover, refugees and their audience endorse refugees’ digital rights claims by using hashtags under the posts and ‘tagging’ the media (see ; note 16), human rights organisations (such as Amnesty International), the EU Parliament and the Commission, high-ranking EU bureaucrats, such as Ylva Johansson (Home Affairs Commissioner) and Ursula von der Leyen (Commission President) (see the link under ). Refugees also refer to the rights inscribed in existing human rights declarations and treaties, recounting that ‘Europe doesn’t share the same human rights you [EU citizens] have’ (; see also ). Ironically, while refugees express their resentment that Europe (i.e., the EU) does not change their plight and stop the denial of their rights, contending that it is ‘making us [refugees] wait forever in this [Moria] camp’ (), they also address some of their claims to the EU institutions, claiming visibility in an invisibilisation regime. Refugees call on the Greek authorities to comply with their human rights obligations and the EU institutions to hold the Greek authorities accountable for the human rights abuses in Moria and protect the rights of refugees in Lesvos ().

Figure 7. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 12 October 2022. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/CjlwkqroiZP.

Figure 8. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 7 August 2021. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/CSRIVE2oZ2t.

Demanding Recognition for Struggles Before a Transnational Spectatorship

Finally, refugees demand the recognition of their struggles in Lesvos before a transnational spectatorship through the posts on NYSMM’s Instagram page. They employ various tactics for such recognition in cyberspace and, with the words of Moulin and Nyers (Citation2007, 358), in ‘public space[s] of their own making’. This kind of recognition comes with refugees’ cognisance of their refugee identity and prior to their formal recognition as status refugees by the Greek authorities, which may take as long as two to three years. Although nearly all refugees involved in NYSMM are officially asylum seekers (Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023; see also AIDA Citation2023, 9), they self-proclaim themselves as refugees: ‘[w]e are every single refugee who is force[d] to flee, every single person who lost memories and home’ (; see also ). Considering this, refugees demand urgent acknowledgement of their rights claims and call their spectators to support Moria refugees in their resistance against the repressive and dehumanising border regime and the juridico-political normalisation of the conditions offered to these refugees.

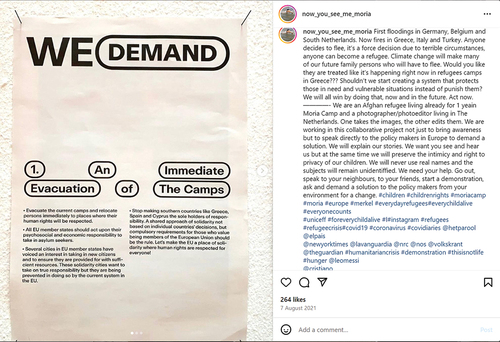

One of the most striking accounts on Instagram that demand the recognition of refugees’ struggles in Europe is a manifesto-like post shared in August 2021, though we cannot confirm if the author of this post is a refugee or not (). The post shows images of three posters with the headline ‘We Demand’. In these posters, NYSMM raises a set of demands concerning the refugees under three titles: an immediate evacuation of the camps, the creation of new spaces for asylum procedures, and structural changes of EU migration policies. Through the posters, refugees ‘perform digital acts in or by saying and doing “I, we, they have a right to”, … [thus] enact themselves as citizen subjects’ (see Isin and Ruppert Citation2020, 61). The caption accompanying this post supplements the demands raised in the posters, aiming to foster empathy with refugees, and concludes with a call to act for and with refugees.

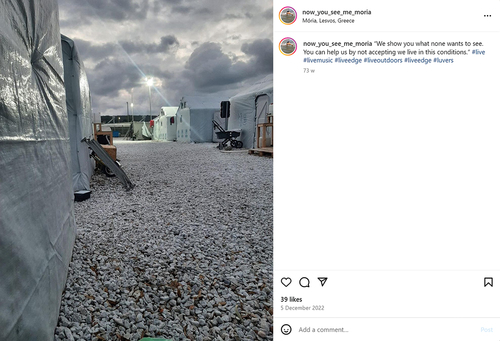

In a post shared on Instagram in December 2022, refugees recount, ‘[w]e show you what [no one] wants to see. You can help us by not accepting we live in [these] conditions’ (). The text accompanies a peopleless image from inside Moria camp, visibilising the degrading camp structures. It is likely that tolerating the suffering of Moria refugees gradually increases their invisibility and lessens the acknowledgement of brutality, human rights violations, and violence occurring at the EU’s borders. Refugees direct their message to EUropean citizens, highlighting that challenging the normalisation of their dehumanising and degrading detention and containment in squalid camps, particularly in contrast to the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees, is crucial for improving their plight. In their eyes, change can happen for instance, by seeing the irreconcilable differences, motivated by racial and discriminatory undertones, between the treatment of Ukrainian refugees and the refugees contained in the Greek islands:

Figure 9. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 5 December 2022. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cly2EIUoCzh.

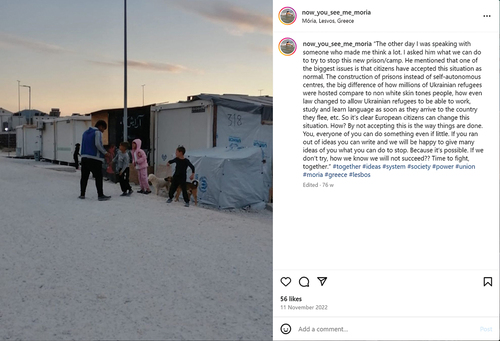

[O]ne of the biggest issues is that citizens have accepted this situation as normal. The construction of prisons instead of self-autonomous centres, the big difference of how millions of Ukrainian refugees were hosted compare[d] to non-white … people, how even law changed to allow Ukrainian refugees … to work, study and learn language as soon as they arrive [from] the country they flee, etc. So it’s clear European citizens can change this situation. How? By not accepting this is the way things are done. ()

Figure 10. An image posted on ‘Now you see me moria’ Instagram page, 11 November 2022. Reproduced with permission. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ck1AutGo3Wb.

While refugees involved in NYSMM ‘put their bodies in action’, as Rancière (Citation2009, 11–12) claimed, with the words, images, and stories they share on social media, they also seek to mobilise their audience as active participants of their cause. NYSMM’s overarching call to its audience is ‘acting and speaking’ with refugees contained in exceptionalised spaces like Moria (see Arendt Citation1998): ‘You, every one of you can do something even if little. … Because it’s possible. If we don’t try, how [can] we know we will … succeed? Time to fight, together’ (; see also ).

NYSMM’s call is certainly heard. A significant audience has demonstrated solidarity with the refugees, not only aiming to increase awareness of their struggles through organising exhibitions and launching campaigns to create, print, and display posters in cyberspace and urban areas worldwide, but also striving to enact change by reaching decisionmakers, advocating for the rights of children detained in Lesvos, and providing legal support for refugees (; Noemí, interview by author, April 17, 2023). NYSMM has encouraged its transnational audience to raise awareness of refugees’ claims and to bring their demands to mainstream media and art platforms. Yet, considering the increasingly hostile and even violent climate towards refugees in and by the EU, it is evident that their battle clearly has been and will continue to be an uphill battle.Footnote19

Conclusion

In this article, we examined how refugees confront EU and Greek border authorities by enacting spaces of looking back and breaking open the authorities’ visuality regime, in terms of surveillance, control, and humanitarian care. We dismantled the official, peopleless image of the CCAC we started out with () and investigated how countervisualities of the EUropean bordering regime represented in this image would look like from refugees’ perspectives. As the spectators of refugees’ countervisualisation, we mobilised our gaze further to access the aspects of pervasive border-ception at the EU’s external borders which, as Kudžmaitė and Pauwels (Citation2022, 271) claimed, ‘otherwise would remain inaccessible’. In our case, the process of transitioning from viewers of refugee-produced content in cyberspace to active participants through scientific research required a critical examination of the act of looking within the broader discourse on refugees’ experiences vis-à-vis their border watchers. While acknowledging the potential for overlooking certain aspects as ‘outsiders’ or inadvertently reinforcing existing power dynamics, our exploration provided valuable insights into the hosting conditions shaping refugees’ lives, which could contribute to advancing academic and political discourse. Using the example of NYSMM, we dissected how refugees trapped in ‘hostipitable’ detention centres in Lesvos (see Derrida Citation2000) challenge the Greek practices of watching out for, of, and over refugees. We ascertained that ICT-induced watching practices do not solely confine refugees to immobilisation in hotspots and similar spaces, nor do they only manifest in the criminalisation, pushing back, and deliberate neglect of refugees at the EU’s external land or maritime borders. They also disrupt refugees’ migratory journeys and their life trajectories by choking refugees ‘without letting die’ (Tazzioli Citation2020, 133). The tightening circle around refugees follows them towards what we termed as ‘border-ceptions’, such as the CCACs on the Greek islands, where every movement of refugees is monitored and controlled. Some policymakers consider this as a model for the entire EU.

We found that the visuality interplay in Lesvos represents a power struggle between visibility and invisibility that the border authorities and refugees are fighting over, hence embodies, in the words of Mirzoeff (Citation2011, 34), ‘a crisis of visuality itself’. While camps like the new CCACs are visibilised and marketed as hospitable ‘reception’ centres, even proudly and blatantly, the camp inhabitants and the denial of their human rights are invisibilised to the outside world while their bodies are hypervisibilised through state-sponsored ICT on the inside in a hostile fashion. It is these visual bordering strategies that refugees at NYSMM make visible by asserting the right to ‘look back’ in scattered, subtle, and clandestine yet virtually united acts of resistance, aiming to be seen and respected (once again) as political subjects with rights. The countervisualisation, supported with refugees’ slogan ‘Now you see me’ is, therefore, also to be regarded as a claim for respect, in the literal meaning of the word ‘respect’, coming from the Latin re (back) and spicere (seeing), to be seen back, to be recognised. Through the protest movement NYSMM, refugees assert claims to improve their conditions in Lesvos. These demands include human rights and dignity, access to adequate and quality food, sufficient shelter, an end to arbitrary detention practices, and halting the construction of the new CCAC. Additionally, they propose the creation of safe, self-autonomous, and non-segregated hospitality places for refugees, and a positive change in the EUropean migration policy. Thus, their protests are shaped around what Brigden and Mainwaring (Citation2016, 428) called ‘individual room for manoeuvre’, and ‘appropriating’ (Borrelli et al. Citation2022) the very spaces in which they are currently monitored, controlled, and debilitated.

We argue that understanding the complexities of the EUropean bordering regime is enhanced from situated analyses that take a bottom-up approach, juxtaposing refugees’ perspectives on their own experiences with and against states’ care, control, and surveillance. Emancipating our ways of seeing from the anti-democratic visuality regime imposed by state authorities, akin to what refugees at NYSMM have been doing, presents significant and timely opportunities for new research avenues in the multidisciplinary scholarship on bordering, migration management, and refugee struggles. For, as refugees herald with their digital rights claims, it becomes increasingly imperative to ‘look back’, to watch out, not for the people coming to EU’s borders for safety and protection, but rather for the authoritarian and choking gaze of the EU’s border watch.

Ethics Statement

The design of this study did not require an ethical review according to the guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity.

Acknowledgements

We hereby wish to thank the Nijmegen Centre for Border Research for hosting the first author for a research visit during April–May 2023, as well as Prof. Panu Minkkinen, Dr. Päivi Neuvonen, Dr. Elisa Pascucci, and the conveners of the panel ‘The datafication of borders in transnational context’ at the ISA 2023 Annual Convention for their comments to refine our ideas on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this article, the term ‘refugee’ includes the term ‘asylum seeker.’ While no single definition of ‘asylum seeker’ exists in refugee law, we understand this term as a person who intends to apply or applied for the recognition of their refugee status under the Refugee Convention (UNGA Citation1951) and is waiting for a determination decision, or a person who remained in the country in which their asylum claim was rejected.

2. ‘Ways of seeing’ denote the idea ‘that what is important about images is not simply the image itself, but how it is seen by particular spectators who look in particular ways’ (Rose Citation2001, 11–12).

3. Last names of our respondent and other subjects mentioned in this article are omitted for privacy.

4. The EU—Türkiye Statement was reached between EU Member States and Türkiye, inter alia, to reduce the number of ‘irregular migrants’ (including refugees) entering the Greek islands from Türkiye. In exchange, the agreement provided EU funding for Syrian nationals under temporary protection in Türkiye and visa-free access of Turkish nationals to the EU (European Council Citation2016).

5. Noemí (co-founder of ‘Now You See Me Moria’), online interview by the first author, April 17, 2023.

6. A hashtag is a word or phrase with a hash sign (#) that tags messages about specific topics on social media.

7. See https://nowyouseememoria.eu.

8. See https://www.instagram.com/now_you_see_me_moria. The numbers are up to date as of June 2024.

9. Stedelijk. Now You See Me Moria, Exhibition. Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/exhibitions/now-you-see-me-moria-2.

10. Rausgegangen. Now You See Me Moria — Poster Exhibition. Accessed January 24, 2024. https://rausgegangen.de/en/events/now-you-see-me-moria-poster-exhibition-3.

11. Screenshots from Instagram are taken and used with the permission of our respondent. To ensure the privacy of users, we covered the comments that were shared under the posts we exhibit in the body of this article. We used Atlas.ti to code each of the screenshots we gathered on social media.

12. Given privacy issues and potential harm to refugees’ safety, we do not reveal any details about refugees involved in NYSMM or by whom the Instagram posts are shared. We acknowledge the limitations of interviewing only one person, such as our respondent’s individual biases and viewpoint as an ‘outsider’ unlike a refugee inhabiting a camp. We, therefore, used the interview data only to support our main data (i.e., social media).

13. ‘Isobox’ is a metal container that houses several families in Moria camp although it is designed for one family (Bicanski Citation2020).

14. Now You See Me Moria. Untitled video. Instagram, October 15, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CjvRSb0oAkc.

15. See also https://everpress.com/profile/now_you_see_me_moria.

16. See e.g., Now You See Me Moria. Untitled image. Instagram, September 13, 2020. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CFEn2ZkF67g.

17. Now You See Me Moria. Untitled image. Instagram, March 22, 2023. Accessed January 19, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/CqGraSoIshC. See also .

18. Now You See Me Moria. Untitled image. Instagram, November 4, 2022. Accessed January 19, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ckjg6l2Iajv.

19. In 2022, the construction of Lesvos CCAC was put on hold by the Greek Council of State’s (highest administrative court) decision (199/19.12.2022) upholding that the access road would irrevocably destroy the forest and avifauna in the protected area (AIDA Citation2023, 41). However, this decision is not directly connected to NYSMM’s attempts to stop the construction.

References

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- AIDA (Asylum Information Database). 2023. Greece country report (2022 update). Accessed March 5, 2024. https://asylumineurope.org/reports/country/greece.

- Amoore, L., S. Marmura, and M. B. Salter. 2008. Smart borders and mobilities: Spaces, zones, enclosures. Surveillance & Society 5 (2):96–101. doi:10.24908/ss.v5i2.3429.

- Arendt, H. 1973. The origins of totalitarianism. (New York): Harcourt Brace.

- Arendt, H. 1998. The human condition. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bateman, J., J. Wildfeuer, and T. Hiippala. 2017. Social media. In Multimodality: Foundations, research and analysis, ed. J. Bateman, J. Wildfeuer, and T. Hiippala. 355–65. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Bayramoğlu, Y. 2023. Border countervisuality: Smartphone videos of border crossing and migration. Media Culture & Society 45 (3):595–611. doi:10.1177/01634437221136013.

- Berger, J. 1972. Ways of seeing. London: Penguin Books.

- Bicanski, M. 2020. Moria refugee camp during the coronavirus pandemic. International Rescue Committee. Accessed June 8, 2023. https://www.rescue.org/uk/article/moria-refugee-camp-during-coronavirus-pandemic.

- Borrelli, L., P. Pinkerton, H. Safouane, A. Jünemann, S. Göttsche, S. Scheel, and C. Oelgemöller. 2022. Agency within mobility: Conceptualising the geopolitics of migration management. Geopolitics 27 (4):1140–67. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1973733.

- Brigden, N., and Ċ. Mainwaring. 2016. Matryoshka journeys: Im/mobility during migration. Geopolitics 21 (2):407–34. doi:10.1080/14650045.2015.1122592.

- Bueno Lacy, R., and H. van Houtum. 2022. The proximity trap: How geography is misused in the differential treatment of Ukrainian refugees to hide for the underlying global apartheid in the European border regime. The ASILE project. Accessed March 7, 2024. https://www.asileproject.eu/the-proximity-trap-how-geography-is-misused-in-the-differential-treatment-of-ukrainian-refugees-to-hide-for-the-underlying-global-apartheid-in-the-european-border-regime.

- Butler, J. 2005. Photography, war, outrage. PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 120 (3):822–27. doi:10.1632/003081205X63886.

- Chouliaraki, L., and M. Georgiou. 2022. The digital border: Migration, technology, power. (New York): NYU Press.

- Close, J. 2022. The EU policy of containment of asylum seekers at the borders of Europe: The closed controlled access centres. International Law Blog. Accessed April 5, 2024. https://internationallaw.blog/2022/04/07/the-eu-policy-of-containment-of-asylum-seekers-at-the-borders-of-europe-2-the-closed-controlled-access-centres.

- Council of the EU. 2015a,2015b. Council decisions (EU) 2015/1523 of 14 September 2015, OJ L239/146 and 2015/1601 of 22 September 2015, establishing provisional measures in the area of international protection for the benefit of Italy and Greece. OJ L248/80.

- Creta, S. 2021. I hope, one day, I will have the right to speak. Media, War & Conflict 14 (3):366–82. doi:10.1177/1750635221989566.

- Dekker, R., G. Engbersen, J. Klaver, and H. Vonk. 2018. Smart refugees: How Syrian asylum migrants use social media information in migration decision-making. Social Media + Society 4 (1):1–11. doi:10.1177/2056305118764439.

- Deportation Monitoring Aegean. 2019. Ongoing criminalization of refugee protests — upcoming trials against migrants on Lesvos. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://dm-aegean.bordermonitoring.eu/2019/02/19/ongoing-criminalization-of-refugee-protests-upcoming-trials-against-migrants-on-lesvos.

- Derrida, J. 2000. Hostipitality. Angelaki 5 (3):3–18. doi:10.1080/09697250020034706.

- Diminescu, D. 2008. The connected migrant: An epistemological manifesto. Social Science Information 47 (4):565–79. doi:10.1177/0539018408096447.

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). 2011. M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece. App no 30696/09. Accessed 21 July, 2024.

- ECtHR (European Court of Human Rights). 2023. A.D. v. Greece. App no 55363/19, 4 April 2023. Accessed July 20, 2024.

- Euro-Med. 2020. Greece’s new confidentiality law aims to conceal grave violations against asylum seekers. Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor. Accessed January 16, 2024. https://euromedmonitor.org/a/4057.

- European Commission. 2020a. Communication on a new pact on migration and asylum (COM(2020) 609 final). Accessed March 5, 2024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0609.

- European Commission. 2020b. Memorandum of understanding between the European Commission … and the Government of the Hellenic Republic … on a Joint Pilot for the establishment and operation of a new Multi-Purpose Reception and Identification Centre on Lesvos (C(2020) 8657 final). Accessed March 5, 2024. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-12/03122020_memorandum_of_understanding_en.pdf.

- European Council. 2016. EU—Turkey Statement, 18 March 2016 (press release 144/16). Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement.

- European Council. 2018. European Council conclusions. June 28. Accessed January 26, 2024. http://europa.eu/!Tx99Dv.

- European Parliament. 2022. The deterioration of the situation of refugees as a consequence of the Russian aggression against Ukraine (debate). Verbatim report of proceedings, March 8. Accessed January 29, 2024. https://perma.cc/5PCG-H4GR.

- European Parliament. 2023. The situation of article 2 TEU values in Greece. LIBE Mission to Greece, March 6–8. Accessed January 29, 2024. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/745609/IPOL_STU(2023)745609_EN.pdf.

- Fassin, D. 2005. Compassion and repression: The moral economy of immigration policies in France. Cultural Anthropology 20 (3):362–87. doi:10.1525/can.2005.20.3.362.

- Fiske, L. 2016. Human rights, refugee protest and immigration detention. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Foucault, M. [1977] 1995. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (New York): Vintage Books.

- Georgiou, M. 2018. Does the subaltern speak? Migrant voices in digital europe. Popular Communication 16 (1):45–57. doi:10.1080/15405702.2017.1412440.

- Hellenic Ministry of Migration and Asylum. 2021. Closed controlled access center of Samos (press release, 21 September 2021). Accessed March 5, 2024. https://perma.cc/P7S9-SM6S.

- iHaveRights. 2023a. The EU-funded closed controlled access centre - the De facto detention of people seeking protection on Samos. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://ihaverights.eu/de_facto_detention_in_the_ccac.

- iHaveRights. 2023b. Young mother successfully sues the Greek government for the treatment she suffered as a pregnant woman in the “hotspot” on Samos. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://ihaverights.eu/ecthr_jugement_greek_hotpsot.

- Isin, E. F., and E. Ruppert. 2020. Being digital citizens. 2nd ed. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Jewitt, C. 2013. Multimodal methods for researching digital technologies. In The SAGE handbook of digital technology research, ed. S. Price, C. Jewitt, and B. Brown. 250–65. London: SAGE Publications.

- Jones, R., and C. Johnson. 2016. Border militarisation and the re-articulation of sovereignty. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (2):187–200. doi:10.1111/tran.12115.

- Kefalas, A., N. Savaricas, and S. Prousalis. 2021. Inside Greece’s closed Samos camp, a ‘European model’ for asylum seekers. France24. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://f24.my/8A5O.

- Koca, B. T. 2022. Bordering processes through the use of technology: The Turkish case. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (8):1909–26. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1796272.

- Kudžmaitė, G., and L. Pauwels. 2022. Researching visual manifestations of border spaces and experiences: Conceptual and methodological perspectives. Geopolitics 27 (1):260–91. doi:10.1080/14650045.2020.1749838.

- Leese, M., S. Noori, and S. Scheel. 2022. Data matters: The politics and practices of digital border and migration management. Geopolitics 27 (1):5–25. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1940538.

- Leurs, K. 2017. Communication rights from the margins: Politicising young refugees’ smartphone pocket archives. International Communication Gazette 79 (6–7):674–98. doi:10.1177/1748048517727182.

- Leurs, K., and S. Ponzanesi. 2018. Connected migrants: Encapsulation and cosmopolitanization. Popular Communication 16 (1):4–20. doi:10.1080/15405702.2017.1418359.

- Loukinas, P. 2022. Drones for border surveillance: Multipurpose use, uncertainty and challenges at EU borders. Geopolitics 27 (1):89–112. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1929182.

- Marlowe, J. 2019. Social media and forced migration: The subversion and subjugation of political life. Media and Communication 7 (2):173–83. doi:10.17645/MAC.V7I2.1862.

- Mirzoeff, N. 2011. The right to look: A counterhistory of visuality. US: Duke University Press.

- Molnar, P. 2020. Technological testing grounds: Migration management experiments and reflections from the ground up. Accessed June 10, 2024. https://edri.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Technological-Testing-Grounds.pdf.

- Moulin, C., and P. Nyers. 2007. “We live in a country of UNHCR”-refugee protests and global political society. International Political Sociology 1 (4):356–72. doi:10.1111/j.1749-5687.2007.00026.x.

- Nedelcu, M., and I. Soysüren. 2022. Precarious migrants, migration regimes and digital technologies: The empowerment-control nexus. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (8):1821–37. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1796263.

- Noori, S. 2022. Navigating the Aegean Sea: Smartphones, transnational activism and viapolitical In(ter)ventions in contested maritime borderzones. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (8):1856–72. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1796265.

- Nyers, P. 2003. Abject cosmopolitanism: The politics of protection in the anti-deportation movement. Third World Quarterly 24 (6):1069–93. doi:10.1080/01436590310001630071.

- Osso, B. N. 2022. Of borders and hypocrisy: The very thin line between protection and expulsion. Refugee Law Initiative Blog. Accessed March 7, 2024. https://rli.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2022/06/14/of-borders-and-hypocrisy-the-very-thin-line-between-protection-and-expulsion.

- Osso, B. N. 2023. Unpacking the safe third country concept in the European Union: B/orders, legal spaces, and asylum in the shadow of externalization. International Journal of Refugee Law 35 (3):272–303. doi:10.1093/ijrl/eead028.

- Pollozek, S., and J. H. Passoth. 2019. Infrastructuring European migration and border control: The logistics of registration and identification at Moria hotspot. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (4):606–24. doi:10.1177/0263775819835819.

- Rancière, J. 2004. Who is the subject of the Rights of Man? The South Atlantic Quarterly 103 (2–3):297–310. doi:10.1215/00382876-103-2-3-297.

- Rancière, J. 2009. The emancipated spectator. London: Verso.

- Rose, G. 2001. Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. London: SAGE Publications.

- Şanlıer Yüksel, İ. 2022. Empowering experiences of digitally mediated flows of information for connected migrants on the move. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies 48 (8):1838–55. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1796264.

- Scheibe, K., and F. Zimmer. 2022. Asylees’ ICT and digital media usage: New life — new information? Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Sontag, S. 2003. Regarding the pain of others. (New York): Picador.

- Tazzioli, M. 2020. The making of migration: The biopolitics of mobility at Europe’s borders. London: SAGE Publications.

- Tazzioli, M. 2023. Counter-mapping the techno-hype in migration research. Mobilities 18 (6):920–35. doi:10.1080/17450101.2023.2165447.

- UNGA (UN General Assembly). 1951. The Geneva convention relating to the status of refugees, 189 UNTS 150. Geneva: United Nations.

- van Houtum, H. 2021. Beyond ‘borderism’: Overcoming discriminative b/ordering and othering. TESG 112 (1):34–43. doi:10.1111/tesg.12473.

- van Houtum, H. 2024. Free the map. From Atlas to Hermes, a new cartography of borders and migration. Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers.

- van Houtum, H., and R. Bueno Lacy. 2020. The autoimmunity of the EU’s deadly b/ordering regime; overcoming its paradoxical paper, iron and camp borders. Geopolitics 25 (3):706–33. doi:10.1080/14650045.2020.1728743.