Abstract

The management of archaeological human remains poses numerous ethical and practical challenges for archaeologists and museum personnel throughout the world. While several countries have developed extensive legislation and guidelines to ensure best practice, Turkey has no specific laws concerning the management of archaeological human remains. The current heritage legislation defines all archaeological materials, including human remains, as state property, a position which makes engagement with stakeholders seeking shared ownership or repatriation of these remains problematic. In the absence of adequate legislation and professional guidelines, a wide range of ad hoc practices have developed among professionals whose dominance in decision-making processes leaves little room for inclusive museum management practices, such as stakeholder consultation, co-curation, the insurance of equal access to museums, and the promotion of human rights. Through a series of interviews with archaeologists and museum professionals, an online visitor survey with 780 participants, and on-site observations in four museums in Turkey, this article examines the existing management practices concerning archaeological human remains and sheds light on various professional biases that have discouraged effective community engagement with this issue in Turkey. This article is intended as a catalyst for further discussion about a topic which has been largely ignored in Turkey by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (TMoCT), museum personnel, and archaeologists.

Introduction

Concepts such as ethics, ownership and stakeholder consultation are just typical examples of western sensitivities that are irrelevant to the Turkish context. Turkey does not even have any indigenous communities; why should archaeological human remains be anybody’s business but the professionals?

Archaeological human remains, and decisions about their management, have been solely the domain of experts since 1925, the year when archaeology and anthropology were established as formal academic disciplines in Turkey (Özbudun-Demirer, Citation2011; Üstündağ & Yazıcıoğlu Citation2014). Despite the diverse nature of human remains collections in Turkey, the role of stakeholders in the management of these remains has never been consultative, shared, or equitable. Insufficient legislation, the lack of procedural clarity, and the centralizing role of the state all mean that more inclusive management strategies have not been considered. As a result, almost a century after the founding of archaeology as a scientific discipline in Turkey, there is limited public engagement and awareness about the management of archaeological human remains.

In this article, we investigate how these factors have impacted the management of archaeological human remains in Turkey. After an overview of the current legislative framework and the stakeholder landscape we assess how both a centralized state and hierarchy in the archaeological and museum professions has contributed to a lack of awareness and disenfranchisement of the public. Relying on semi-structured interviews with sixteen archaeologists and museum personnel, and a public survey of 780 people, we investigate the ethical dilemmas and biases that shape the current policies and practices of archaeological human remains management in Turkey.

Managing hierarchies: expert dominance and public engagement in human remains management

In the past three decades, different legislation and guidelines concerning the management of archaeological human remains has emerged in many countries to address issues such as respect for the dignity of the deceased, the importance of dialogue and stakeholder consultation, and the ethics of display (Fforde, et al., Citation2002; Cassman, et al., Citation2006; Giesen, Citation2013; Fletcher, et al., Citation2014; Gazi, Citation2014; Swain, Citation2016; Overholtzer & Argueta, Citation2018; Squires, et al., Citation2019; Clegg, Citation2020). Decolonization projects in several museums have drawn attention to the problematic nature of human remains collections at many North American and European museums and have raised public awareness and community engagement in debates about the ethics and ownership of human remains (Lonetree, Citation2012; Wintle, Citation2013; Wergin Citation2021). These collections include countless human remains taken from formerly colonized countries without the consent of the related communities by European travellers, collectors, and archaeologists (Walker, Citation2000; Curtis, Citation2003; Stumpe, Citation2005; Aldrich, Citation2009; Jenkins, Citation2011; Fforde, Citation2013; Bruning, Citation2017; Biers, Citation2019). As a result, many museums have faced repatriation claims and lawsuits (Thomas, Citation2001; Stumpe, Citation2005; Jenkins, Citation2011; Bruning, Citation2017).

The display of human remains in museums has been a controversial issue for groups with different sensibilities and beliefs, and views differ about the appropriate role of these types of remains. For example, the controversial Body Worlds exhibitions received considerable criticism from many visitors who found the explicit displays of human remains sensational and unethical (Barilan, Citation2006; Allen, Citation2007; Moore & Brown, Citation2007). Initiatives such as the UK group Honouring the Ancient Dead promote respect for the ancient dead and advocate for the inclusion of spiritual or faith-based groups in the decision-making process (Restall Orr, Citation2004; Wallis & Blain, Citation2011). Outside of North America and Europe there are also several cases related to the management of human remains which reflect different cultural practices and beliefs. Since the 1980s, both Christian and Muslim stakeholders in Egypt have challenged state archaeological museums about displays of human remains. Disputes have intensified and divided public opinion following a fatwa issued in January 2021 by the religious scholar Ahmed Karima who proclaimed that, according to Islam, the display of mummies in Egypt’s museums violated the dignity of the dead (Ikram, Citation2018; Sabry, Citation2021).

In many countries, a growing awareness about the ethics of displaying human remains has forced a re-evaluation of both the existing legislation for human remains management, and who is authorized to make decisions about these remains. Many institutions have taken steps in the past two decades to meet more diverse stakeholder expectations. For example, the World Archaeological Congress created the Vermillion Accord on Human Remains in 1989 to urge archaeologists to engage more effectively with stakeholders (WAC, Citation1989). Countries such as Canada, Australia, and the US developed legislation to protect the rights of Indigenous communities concerning their human remains and highlighted the importance of dialogue and consultation (Cybulski, Citation2011; Fforde, Citation2013; Pardoe, Citation2013). The International Council of Museums’ Code of Ethics and Standards for Museum Practice, Principles IV and VI also emphasize how museum collections often have a range of meaning and identity for different communities which should be respected. Museums are encouraged to prioritize inclusive management strategies such as community consultation, co-curation, and an openness to restitution and repatriation, particularly with collections of human remains. Addressed in section 4.3 ‘Exhibition of Sensitive Materials’, ICOM notes that

Human remains and materials of sacred significance must be displayed in a manner consistent with professional standards and, where known, taking into account the interests and beliefs of members of the community, ethnic or religious groups from whom the objects originated. They must be presented with great tact and respect for the feelings of human dignity held by all peoples. (ICOM, Citation2017)

In line with ICOM’s recommendations, several surveys have been conducted in museums throughout North America and Europe to examine more systematically the diverse professional and public responses towards human remains displays (Kilminster, Citation2003; Brooks & Rumsey, Citation2006; Patterson, Citation2007; Tatham, Citation2016). Collectively, these surveys have shown that most visitors support the display of human remains in museums (Biers, Citation2019). Many museums, fortified by this strong public support, are reluctant to remove or repatriate their human remains collections. Instead, they are working to prioritize the educational over the sensational value of displaying these collections (Stumpe, Citation2005; Jenkins, Citation2011; Fletcher, et al., Citation2014; Swain, Citation2016).

Balancing the needs of heritage professionals, meeting the demands of the public, and including a more diverse range of stakeholders are challenges, but continual reassessment of and revisions to national legislation, and consulting with diverse stakeholders, are becoming common practice in many countries (Fforde, 2002; Walker, Citation2004; Stumpe, Citation2005; Lohman & Goodnow, Citation2006; Cybulski, Citation2011; Fossheim, Citation2012; Pardoe, Citation2013; Squires, et al., Citation2019). These efforts challenge top-down decisions about human remains management and help to dismantle the unequal power dynamic that has existed for centuries between the public and state institutions. Yet, in some parts of the world, such as Turkey, professionals who are vested in maintaining traditional hierarchies of power in state museums and university archaeology departments continue to shape decisions and restrict any involvement of the public with human remains collections.

Understanding historical legacies of hierarchy and power: the archaeological and museological professions in Turkey

The aforementioned discussions have clearly shaken the archaeological and museological professions in many parts of the world. Yet, these international discussions have had a limited impact on archaeology and museums in Turkey (Doğan & Thys-Şenocak, Citation2019). To understand why there has been so little attention paid to the question of human remains by the TMoCT, archaeologists, and museum professionals in the country, and a resistance to bringing inclusive and consultative practices into the management of these remains, we first need to look at the history of archaeology and museums in Turkey and the hierarchical structures that have shaped these related professions and disciplines.

Archaeology emerged as a formal scientific discipline in the 1920s as part of a nation-building project of the newly established Turkish Republic. The project aimed to build a new future and identity for Turkey that was deeply rooted in Anatolia (Özdoğan, Citation1998; Tanyeri-Erdemir, Citation2006; Atakuman, Citation2008; Özbudun-Demirer, Citation2011). Between the 1920s and the 1940s, archaeologists and anthropologists, with the support of the Turkish state, embarked on an ambitious campaign to excavate many sites around the country and to find evidence for the biological and racial origins of Turkish people in Anatolia (Atakuman, Citation2008; Özbudun-Demirer, Citation2011; Üstündağ, Citation2011; Üstündağ & Yazıcıoğlu, Citation2014). Enthusiasm for this ideologically motivated research lost momentum after the 1950s owing to the changing political climate in the country, but Turkish archaeology sustained its steady growth with the discovery of new sites and by training a new generation of archaeologists and museum professionals. However, public engagement in archaeological projects is still rare (Ricci & Yılmaz, Citation2016; Gürsu, Citation2019). How ‘the public’ is defined and whether they should be involved are decisions often made by experts long before stakeholders are identified.

Part of the problem with heritage site management practices in Turkey is the highly centralized bureaucratic system which leaves little room for actors who are not appointed by the TMoCT (Baraldi, et al., Citation2013; Human, Citation2015; Gürsu, et al., Citation2020). Directors and co-directors of each archaeological excavation must first be approved by the Ministry; non-Turkish archaeologists are rigorously scrutinized by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and can only lead an excavation with a co-director who is a Turkish citizen. Directors of archaeological projects are not required to solicit opinions or accommodate the demands of local communities unless the excavation site needs to expropriate property owned by these communities.

The role of the public in decision-making processes about human remains in Turkish state museums has been similarly limited as these institutions are managed by state-employed professionals who must follow the approved collections management policies established by the TMoCT (Baraldi et al., Citation2013; Shaw, Citation2011).Footnote2 Until the 1990s Turkish museums were designated by the state to be the caretakers of the country’s heritage and to educate the public about their common past (Atakuman, Citation2010; Özkasım & Ögel, Citation2005; Shaw, Citation2007, Citation2011; Ünsal, Citation2008). Public engagement was limited to conferences, talks, and educational programmes which were more didactic than dialogic (Ilıcak, Citation2010; Ünsal, Citation2008; Shaw, Citation2007, Citation2011). Therefore, although most museum professionals today appreciate the potential benefits of visitor studies and surveys, such activities are rarely conducted in Turkish state museums because this tradition is still not well established, or insufficiently funded (Bozoğlu, Citation2019; Karadeniz, Citation2015).

In both archaeological excavations and museums, the Conservation of Cultural and Natural Property Law 2863, enacted in 1983, defines all archaeological finds and sites as ‘state property’, and does not require collaboration with diverse stakeholders. Nor does it provide incentives for archaeologists or museum professionals to devise inclusive public engagement strategies. Despite this pessimistic tableau, inclusion of the public in academic, archaeological, and heritage projects is increasing (Atalay, Citation2007; Apaydın, Citation2016; Ricci & Yılmaz, Citation2016; Pulhan, Citation2019). A policy passed by the TMoCT in 2005 stipulated that all research excavations conducted in Turkey must include a site management plan which makes provisions for public engagement in their project applications to the ministry (Çolak, Citation2011; Human, Citation2015; Orbaşlı, Citation2013).

A few archaeological excavations in Turkey have tried to informally implement participatory approaches in their projects to encourage more sustainable dialogues with local communities (Atalay, Citation2007; Orbaşlı, Citation2013; Apaydın, Citation2016; Ricci & Yılmaz, Citation2016; Pulhan, Citation2019). These efforts have shown that the public is indeed interested in learning about the past and contributing to existing decision-making mechanisms. A public survey with 3,601 participants titled ‘The Relationship Between the Public and Archaeology in Turkey’, conducted by the SARAT project (Safeguarding Archaeological Assets of Turkey) in May 2018, similarly demonstrated that, contrary to the assumptions made by most academics and museum professionals, the public does have an interest in the heritage of Turkey’s distant past. Forty-six per cent of the surveyed population considered the remains of ancient civilizations in their country as part of their heritage (Gürsu, et al., Citation2020: 13–14). These examples show that there is significant but unrealized potential to increase stakeholder engagement in Turkish archaeology and museums.

The current legislative framework in Turkey concerning archaeological human remains

In the light of the above discussion about how heritage legislation in Turkey is shaped by bureaucratic and professional hierarchies, it is useful to consider how this situation has impacted human remains management. Several laws concerned with the preservation of antiquities in Turkey were passed from 1869 to 1973 (Özdemir, Citation2005; Eldem, Citation2011), but none specifically addressed human remains (Üstündağ, Citation2011). The aforementioned Law 2863 became the first comprehensive heritage legislation to introduce a variety of new concepts (such as natural and cultural heritage), while expanding the list of cultural and natural properties to be protected, including human remains. Both Law 2863 (1983) and its later iteration, Law 3386 (1987), define protected property as:

All kinds of animal or plant fossils, human skeletons, flints (slag), volcanic glass, bone, all types of metal tools, tile and ceramic vessels, statues, figurines, tablets, cutters, weapons of defence and bludgeons, icons, glass objects, decorative objects, ring stones, earrings, needles, pendants, seals, bracelets and similar types of objects, masks, diadems, documents made of leather, textile, papyrus or metal, weights and measures, coins, inscribed or stamped plates, handwritten and illuminated manuscripts, miniatures, engravings, oil and watercolour paintings that have artistic value, inherited relics, medals and medallions, ceramics, earthenware, glass, wooden, textile and similar moveable objects and their parts.

As is evident from the inclusion of human skeletons in this long list of cultural and natural property, there is no distinction made between human remains and other types of objects, all of which are defined as ‘state property’ (devlet malı) (Law 2863, Part 1 Article 5). Unlike many countries where specific legislation exists for human remains from different time periods, such as the UK Human Tissue Act (HTA, Citation2004) which defines archaeological remains as over 100 years old, there is no chronological distinction in Law 2863 differentiating between human remains from prehistoric, more recent archaeological, or forensic contexts (Üstündağ, Citation2011: 462). Apart from Laws 2683 and 3386, the only other legislation that addresses archaeological human remains is the Military Museum Law, passed in 1984 (Article 18.3), which stipulates that military museums have jurisdiction over all material in their collections which is military in nature, including forensic institutions.Footnote3 Similar to Laws 2863 and 3386, the Military Museum Law also defines human remains as ‘state property’. In the absence of specific legislation for human remains management, decisions made in the field and museums are generally left to individual archaeologists and museum personnel. As discussed in more detail below, most prefer to have a limited engagement with stakeholders in the decision-making process about the ethics and practicalities of managing these types of remains.

Implications of limited legislation: assessing archaeological and museological practices of human remains management and display in Turkey

Between December 2016 and March 2018 semi-structured interviews were conducted with sixteen experts; these interviews were divided equally between archaeologists working at excavations and museum personnel employed in state museums. Six of the eight archaeologists interviewed were female and all archaeologists were over forty-five years of age at the time of the survey. Collectively their work represents a wide range of archaeological sites in Turkey and includes five geographical regions (i.e., Marmara, Aegean, Central Anatolia, Mediterranean, and South-east), and seven archaeological periods: Late Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Late Antique, Byzantine, and Ottoman. The criteria used to select museum personnel for interview were based upon the nature of the collections in the museums where they worked; all included archaeological collections that are rich in human remains. In the museums, directors and curators were interviewed. Three of the eight museum personnel interviewed were female; the ages for all ranged from thirty to sixty years old. Interviewees were shown our questionnaire prior to an in-person recorded interview,Footnote4 and were asked about various aspects of human remains management. Questions were divided into three categories: the practical problems of working with human remains, evaluation of existing legal guidelines, and, finally, stakeholder engagement. Below we have classified the answers given to each category under three themes which summarize the issues most frequently raised during interviews: limited resources, limited guidelines, and conflicting interests.

Limited resources

In the first section of the interviews, we asked the archaeologists and museum professionals, 1) what they considered as proper management strategies for human remains, and 2) what management problems they have encountered in the field. The answers given by the archaeologists revealed that the ambiguous status of human remains in Turkish legislation, and the lack of resources allocated to their management, have resulted in a wide range of ad hoc decisions and varying professional practices. While all archaeologists interviewed agreed that the question of how to properly treat human remains was important, they mentioned they often faced more urgent problems such as limited excavation budgets and suitable storage to properly protect these types of vulnerable organic finds. Seven out of the eight interviewees noted that when attempts were made to give these remains to local state museums affiliated with the excavations, museum personnel did not want to accept them because they also lacked suitable storage. Faced with these difficult circumstances, most archaeologists did the best they could. This generally resulted in human remains stored together with animal remains and other excavation finds in on-site excavation depots lacking climate or pest controls.

All museum personnel interviewed had similar practical concerns about inadequate conservation and storage facilities.Footnote5 They recognized the vulnerable nature of human remains and acknowledged that these deserved careful treatment, but stated that the museums where they worked lacked the resources to ensure the proper storage and display of these remains. As with archaeological excavations, methods of storage and display varied considerably between museums depending on resources. One museum was able to conduct a yearly inspection and inventory of the human remains in its collection; yet most had conducted the last inspection five to seven years prior to our interviews. Both groups in the survey indicated that, despite a general willingness to better preserve human remains, this was hampered by a lack of resources.

Limited guidelines

The second part of our survey examined what these sixteen professionals thought about the existing legal and professional guidelines concerning human remains. Five of the archaeologists did not see a major problem with the general failure to offer specific management solutions for human remains. Furthermore, most archaeologists voiced varying degrees of concern about how more specific legislation might hamper scientific research and make archaeological work less efficient. Ambiguous guidelines were considered by some as advantageous as this resulted in more flexibility. The reasoning behind this stance was expressed more clearly during our conversations concerning stakeholder engagement and will be discussed below.

The museum professionals, on the other hand, were less forthcoming about their opinions and perceptions of current legislation. They stated that they adhered to the centralized and state-generated collections management policy for museums as well as Law 2863 and made no comments about the content or efficiency of these laws. However, some indicated that they did not have an in-house anthropologist and that more guidance on how to handle human remains could have been helpful at times. In particular, personnel who worked in stores, who were involved in moving or auditing collection items, admitted that they felt uncomfortable when encountering human remains either because they lacked the expertise or felt uneasy around human remains in general. They stated that they would have appreciated more guidelines so they could be better prepared to deal with these types of collections.

Regarding display, each museum had substantial differences in exhibition strategies, and preferred display methods usually depended on the museum’s financial position and the beliefs and initiatives of the museum director or curator. In some museums, human remains were the focal point of the exhibition and displayed in illuminated, climate-controlled cases; in others they were displayed in more secluded corners of galleries in older and more traditional exhibition cases. Some displays were conceptualized as part of a larger narrative about burial traditions, and human remains were contextualized within an exhibition about ancient graves; in others, especially galleries with Byzantine and Seljuk mummies (eleventh to thirteenth centuries), human remains were in better states of preservation with skin and organs quite visible.

A conflict of interests

In the third part of our survey, we asked what the interviewees thought about the classification of human remains together with other archaeological finds. The answers to this question were quite striking. Human remains, according to one interviewee (an archaeologist), should not be differentiated from animal bones and evaluated free of ethical or emotional responses since ‘the priority of science should be producing knowledge’. Others, despite acknowledging potential ethical problems, treated the issue of ethics as ‘a secondary issue’ compared to the benefits of scientific progress and educational opportunities that could be extracted from the remains. On the other hand, the responses to questions about the ethics of displaying human remains varied considerably. One curator reiterated the fact that state legislation dictates that human remains are no different from other cultural objects, hence they should be displayed. Another noted that exhibitions of human remains were useful for educational purposes. Displaying the actual skeleton in some kind of archaeological context was essential for one museum director as this helped people imagine the distant past more vividly. Only one museum curator who was responsible for mummy exhibits felt that the museum should be concerned about the ethics of displaying these remains as visitors can attribute very different meanings to them. This curator felt that museums should not perceive these remains as just another artefact but as actual human beings who had lived in the past. In general, for most interviewees, it did not matter that human remains were classified with other archaeological finds, yet they acknowledged there should be some distinction made with this category of finds.

Questions of stakeholder consultation and engagement

In the final part of our survey, we collected views on stakeholder engagement and asked the interviewees: 1) what they thought about defining human remains legally as ‘state property’, and 2) how they engaged with potential stakeholders (e.g., living relatives, ethnic and religious groups, the general public) who might claim ownership of the human remains with which they worked. Many reiterated that all archaeological finds were defined as state property according to Turkish heritage legislation, and this was a bureaucratic matter which should not be interfered with. Half of the archaeologists and museum professionals agreed that this definition might pose ethical challenges, particularly human remains from more recent eras, such as the Byzantine (fourth century–fifteenth century), late Ottoman (eighteenth century–twentieth century) and early Republican eras (1923–1940), as they could be linked to living relatives. The collection of human remains from the battlefields of the First World War in Gallipoli, and their sensationalist displays in museums and private ‘war galleries’, are the most striking examples which occasionally cause stakeholder disputes (Thys-Şenocak & Doğan, Citation2018).

Most of the archaeologists admitted feeling uneasy when they discovered human remains from the Islamic periods as they felt the cultural norms and expectations surrounding how these should be treated were different and they wished to avoid controversy. Therefore, they often refrained from making independent decisions about these remains and sought advice from the TMoCT. With regard to both excavated and displayed pre-Islamic human remains, both archaeologists and museum professionals expressed doubt that there would be any living stakeholders related to these remains. Moreover, some of the interviewees, including the archaeologist quoted at the beginning of this article, claimed that Turkey did not have indigenous communities similar to the Native Americans/First Nations in the US and Canada or Indigenous/Aboriginal Peoples in Australia and New Zealand. Hence, they felt that prioritizing such ethical considerations based on a concern for living stakeholders would be pointless.

When reminded that there could be potential stakeholders among the general public and local communities, the interviewees revealed different biases. For the archaeologists, the prospect of consulting with stakeholders (in most cases the public and local communities) about human remains discovered during an excavation was neither a consideration nor an attractive strategy. Some expressed a fear that sharing information about a site could attract grave robbers. Others were concerned that scientific analysis of human remains, such as DNA sampling, could be hampered by the emotional sensitivities of local communities if they were made aware of the remains. Although an example of a participatory research project from the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük, where the local community expressed discomfort with the excavation of human remains for religious reasons (Atalay, Citation2007: 259), confirms these concerns to a certain degree, there is no comprehensive research verifying how widespread these concerns might be at other sites. Two of the archaeologists interviewed were strongly against engaging in stakeholder consultation because they believed the public did not have sufficient education about the requirements of fieldwork and would not understand how these remains could be used to answer scientific questions. For most of the archaeologists, reburial constituted a complete loss of scientific data. Similarly, the museum professionals claimed that neither museum visitors nor the local community were particularly interested in human remains unless they were from the Islamic periods. As a result, they did not see a benefit to engaging with the public about the management of human remains in their collections.

What does the public really think about human remains?

Our interviews with archaeologists and museum personnel revealed that both groups had made certain assumptions about the views of museum visitors, the local community, and the public in general. This is implicit in statements such as ‘people are not concerned about the display of human remains unless they are from the Islamic periods’ or ‘the public is not educated enough to participate in decision-making’, and reflect assumptions that there is no need to engage with the public and consult a wider range of stakeholders. However, no systematic survey has ever been conducted in Turkey to assess public opinion regarding human remains management and display. We therefore decided to initiate a survey to determine what the public in Turkey actually thought about this topic. To answer our questions two types of data, both qualitative and quantitative, were collected. First, as qualitative data, we recorded and evaluated the reactions of museum visitors to various displays of human remains. The results of these observations were compared with the accounts of visitor behaviour made by museum personnel in the stakeholder questionnaire. Quantitative data were then gathered using an online visitor survey of 780 people to help us to understand the attitudes of museum visitors in Turkey about the display of a variety of human remains from diverse contexts (e.g., skeletons, mummies, anatomical collections, human remains from prehistoric, Roman, Greek, Turkic, and Islamic provenance).

On-site observations of museum visitors

During our interviews of museum personnel, several provided fascinating accounts of visitor behaviour. Some of these contradict the general picture painted by museum personnel already outlined of a public with no interest in human remains and their narratives revealed something quite different. One anecdote concerned a local wedding party which requested official permission from the museum to sacrifice an animal in the garden of the museum. According to the curator who responded to this request, the wedding party believed that by sacrificing an animal on behalf of the mummies in the collection the newlywed couple would be blessed. In another account, a curator noted that many people in the local community of a museum displaying Seljuk era (eleventh–thirteenth centuries) mummies believed that they have talismanic properties and, as a result, the museum had received several requests for pieces of mummy wrappings from local people. These requests were denied with an explanation that they were archaeological remains and state property.

Besides these requests, museum staff from three museums observed visitors praying in front of mummy displays. One example is the so-called ‘blonde nun mummy’ at one museum which is popular with visitors and has attracted international media attention. This mummy was discovered in Cappadocia in an eleventh-century Byzantine cave church (Doğanbaş, Citation2001; Efe, Citation2015). Scientific analysis conducted on her well-preserved remains revealed that she had blonde hair and was buried according to Christian traditions (Efe, Citation2015). The very human quality of the remains elicits strong visitor reactions. Our own on-site observations, along with the testimonies of museum personnel, suggest that reactions are considerably stronger towards this particular mummy than others on display in the same museum. The presence of recognizable human features such as skin and hair are known to affect visitors as they can better identify with the person as they appeared in life (Joy, Citation2014; Zhuravska, Citation2015; Biers, Citation2019). When asked about visitor reactions to the mummies in the collection, the museum personnel noted that they had observed a wide range of responses, from children crying to visitors praying for the blonde nun mummy and the adjacent display of three baby mummies. Two museum staff reported that they had been confronted by some visitors who believed the mummies should be removed from the display cases and reburied. A few visitors shared their views with staff about unethical aspects of the exhibition; other groups expressed their discomfort about viewing human remains and believed that according to Islam it was a sin to display them.

Despite the interest and mixed reactions shown by visitors to the displays of human remains, none of the museums in this study had conducted surveys to determine public opinion. Museum personnel believed visitors would have little interest in the ethical aspects of displaying these remains because they assumed that their public, composed largely of Turks, were not genetically or culturally related to these mummies. Modern Turkish society, however, includes many different communities, such as Greeks, who could be culturally or genetically related to the Byzantine era mummies and human remains displayed in these, and many other Turkish museums. Regardless of the interest or affiliation of present-day Greeks with these remains, collecting data about public opinion can help the museum to recognize stakeholders’ concerns, especially since there is evidence that some visitors do have strong feelings about these displays. Like the museum staff, we also noted during our on-site observations some visitors performing prayers and children crying in front of the mummy displays. Student groups were often the most engaged visitors; their reactions ranged from taking selfies with the mummies to walking away from the display cases in disgust. Our on-site observations and the anecdotes from museum personnel constitute only a small sample of visitor reactions. However, when combined with our survey results discussed below, it is clear there is a much richer and more nuanced range of visitor responses to the display of human remains for which museum personnel had not accounted.

Assessing public opinion: online survey

To better assess the role of public opinion in issues related to the management of human remains 780 respondents were invited to participate in a public survey conducted online via the Google Forms platform between 8 February 2021 and 22 June 2021.Footnote6 The survey language was Turkish, and the survey had twenty-two questions: eight were multiple choice, seven linear scale, four checkbox, and two open-ended questions. The survey was divided into five sections: 1) demographics, 2) how the participant felt while viewing human remains in museums, 3) assessing the extent to which the participant approved of the display of different types of human remains, 4) assessing the extent to which the participant approved of the display of human remains from various periods, and lastly 5) measuring the degree of participant approval concerning the reasons for display, and whether museums should exercise special care to differentiate human remains collections.

Demographics

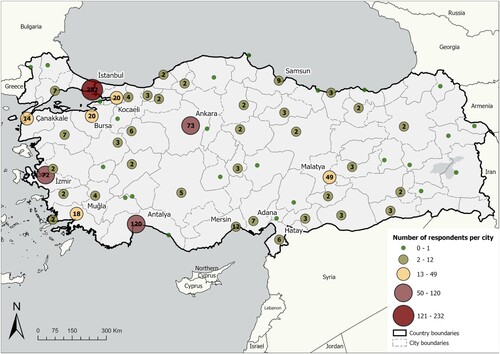

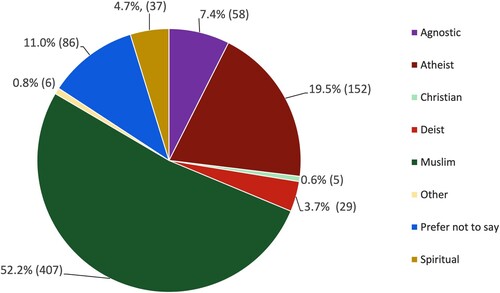

We initially aimed to conduct the survey in person in the museums where we had undertaken on-site observations of visitors and interviewed museum personnel. However, owing to Covid-19 restrictions and museum closures, we conducted the survey online. This format significantly increased the participation rate (65 of the 81 cities in Turkey are represented), but also limited our participants to a computer-literate sample group (). Nevertheless, the age distribution of the participants is quite balanced. According to our results, 45.2% were between the ages of 18–32 years, 36.8% between 33–48, 15.8% between 49–65, and 2.2% 66 or over. Under 18s were not asked to take part. Moreover, 40.3% of participants were male and 58.1% female. 1.54% preferred not to disclose this information; one identified their gender as other. Lastly, in terms of the representation of different belief groups, Muslims (52.2%) and Atheists (19.5%) made up the two largest groups,Footnote7 followed by six others ().

Results

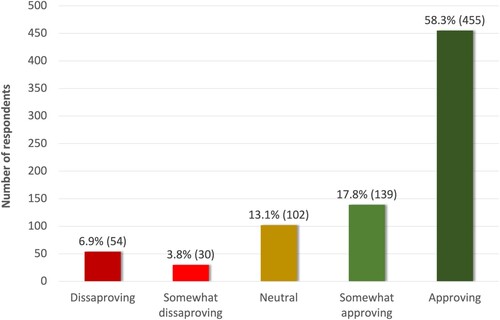

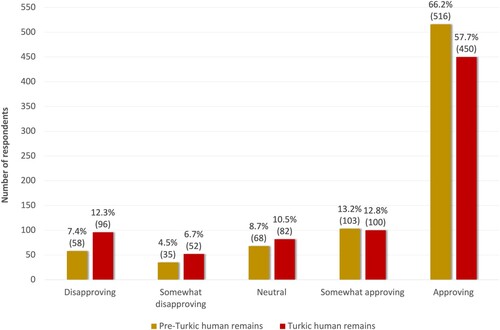

Based on the answers to the survey, 58.3% approved, and 17.8% somewhat approved, of the display of human remains in Turkish museums, demonstrating a considerably positive attitude towards viewing displays of human remains ().

figure 3 Graph showing the overall approval rates of respondents for the display of human remains in museums.

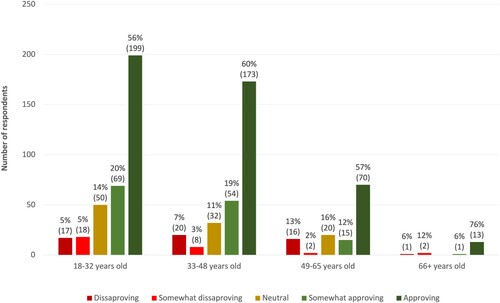

This approval rate showed no major differences between different age groups, except for those aged over 66 whose respondent number was the lowest and may have skewed the data for this question ().

The rate of approval for the display of human remains from pre-Turkic periods was 79.4%; for Ottoman and Seljuk remains it was 70.5% (). Approval rates for the display of human remains from different religious contexts were similar with 69% indicating they approved or somewhat approved of the display of a Muslim individual, and 72% approved or somewhat approved of displaying an individual affiliated to a religious group other than Islam. When asked which types of human remains were preferred for a museum exhibition, 83.5% wanted to see prehistoric human remains, 49.2% Turkic and Ottoman, and 60.4% wanted to view human remains from other periods, such as the Roman, Greek, and Byzantine periods. Sixty-nine per cent indicated they wanted to see human remains from all of the archaeological periods of Anatolia.

figure 5 Graph showing a comparison of the approval rates for the display of human remains from Turkic periods (Seljuk and Ottoman) and pre-Turkic periods (including prehistoric, Roman, Byzantine).

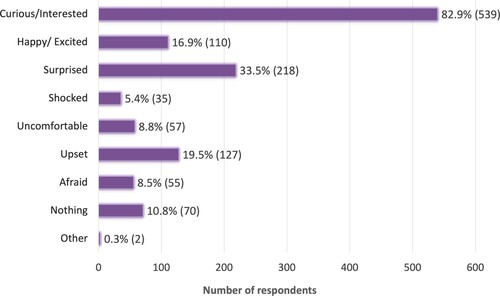

A significant majority, 81%, stated that museums should place signs and information panels to warn visitors in advance about the presence of human remains in galleries. Out of ninety-two open-ended answers given to Q22, twenty-six (28.26%) specifically addressed the potential psychological harm the display of human remains might cause for children and sensitized adults. Although 83.3% stated they felt ‘interested/curious’ while viewing human remains in museums, a range of other positive and negative emotions was also shared ().

figure 6 Graph showing the range of emotions felt by respondents when they viewed human remains in museums.

Lastly, 81.3% considered human remains to be different from other museum objects and deserving of special care. Twelve per cent gave more extensive answers to the survey’s open-ended questions about why they view human remains differently. Respondents who approved of the display of human remains for educational (82.5%) and scientific purposes (90.2%) stated that they were not sure how they would feel if they were the ones exhibited, acknowledging the complicated nature of the issue of consent. Those who disapproved strongly of the display of human remains, despite recognizing the potential educational benefits of display, cited humanitarian, ethical, and religious concerns. Forty-nine percent of all open-ended responses indicated some level of discomfort with the display of human remains in museums, emphasising the dead's right to respect, privacy and/or a final resting place.

Discussion: is the inclusive management of human remains possible?

Prior to our public survey, no study had been conducted to assess public opinion about archaeological human remains collections in Turkish museums. What we had initially assumed about public opinion on this issue was largely based on our on-site observations in museums and the anecdotal evidence provided by museum professionals and academics. The qualitative data collected on-site allowed us to assess limited aspects of public opinion concerning human remains, but when compared to the more quantifiable survey data a different story emerged. Contrary to the claim made by many museum professionals, our survey clearly demonstrated that human remains from the Islamic or Turkic periods did not elicit stronger objections from visitors. Almost half of the respondents (49.2%) indicated that they wanted to see Turkic and Ottoman human remains exhibited in museums. Yet, visitor interest was slightly higher for human remains from Roman, Greek, or Byzantine periods (60.4%) and for prehistoric human remains (83.5%).

Moreover, visitors did not differentiate between human remains based on ethnic or religious affiliation. Thus, the suggested public sensitivity about Islamic or Turkic remains compared to remains from other eras appears to be a reflection of professional biases, and is an inaccurate reading of visitor opinion. Second, the high percentage of participants (81.3%) who acknowledged that human remains are not ordinary objects and deserve special care indicates that visitors are both aware of, and appreciate, the unique nature and management needs of human remains compared to other archaeological materials. This awareness is equally present for all groups of visitors from all educational backgrounds, an outcome that contradicts the opinions of museum personnel who claim that the public is neither interested nor sufficiently educated to engage in discussions about the ethics of displaying these remains.

None of the museums where our on-site interviews were conducted had signs warning the visitor prior to entering galleries to expect human remains on display. Even though an overwhelming majority of the survey respondents (81%) stated that this was necessary, the museums had never considered implementing a more sensitive proactive exhibition strategy. In particular, the display of the remains of children, and mummies whose bodily integrity is not well preserved, were of most concern to visitors as these are the least approved category of human remains displays (44% and 52.6% respectively). Out of ninety-two open-ended answers given to Q22, seventeen (18.5%) specifically underlined the problem of children viewing human remains within museums. The reactions we observed of children upset by the displays of the Byzantine blonde nun mummy and the baby mummies in two museums corroborate the results of our survey and point to the need for these museums to ask, rather than assume, the needs and opinions of their visitors.

Conclusion: towards new legislation and practices for inclusive human remains management in Turkey

The management of human remains is neither easy nor straightforward as the subject is entangled with countless cultural, religious, scientific, and ethical concerns. The question of how to respectfully manage human remains has been asked by many researchers in several countries, yet the academic literature in Turkey has yet to offer solutions. This current study does not attempt to suggest an easy fix to the problem of a lacuna in policies and legislation; rather, it aims to investigate current practices, issues, and biases in the field, and promote public and professional awareness about the challenges of managing archaeological human remains.

Our research has demonstrated that limited human remains legislation and expert dominance in both museum and archaeological excavations have shaped display and management strategies in Turkey. Contrary to what has developed in many countries, legislation which differentiates human remains from other objects and reflects an awareness of ethical concerns has failed to develop in Turkey. This gap in legislation has encouraged some professionals to treat archaeological human remains as ordinary artefacts, failing to recognize the unique and sensitive nature these finds may have for potential stakeholders. Moreover, the process of including stakeholders in decision-making processes pertaining to human remains, such as repatriation, restitution, and co-curation, is not established in Turkish museology and archaeological practice for two fundamental reasons. First, participatory and consultative approaches to heritage are often considered in Turkey to be inefficient, and many academics and museum personnel believe that inclusive and collaborative management policies can lead to delays. Second, the dominance of centralized bureaucracy and professional experts has created a top-down decision-making mechanism in the Turkish heritage sphere, leaving little room for public participation and expressions of interest about human remains collections.

Although these problems result from established professional biases and cultural norms, they are not insurmountable. Recognizing a basic distinction between archaeological human remains and other archaeological finds is the first step. Our research, and that of many working with these types of remains, has shown that human remains are not ordinary artefacts. A clearer distinction between different types of human remains is essential particularly from recent periods, as there could be living stakeholders. Legislation that distinguishes between different types of human remains can move the decision-making processes about the management of the dead into a more equal partnership between ‘experts’ and stakeholders, raising awareness among relatives, members of a local community, and the general public. Clearer professional guidelines based on inclusive management strategies will reduce the number of ad hoc decisions while opening up space for consultation, a process which may be less convenient for museum personnel and archaeologists, but will allow for diverse voices to enter into the discussion about how to manage archaeological human remains.

This research has clearly demonstrated that, contrary to what professionals working in the field have posited, the public in Turkey is interested in and do have strong opinions about archaeological human remains. Therefore, our next step is to expand the data collected for this research, increase the number and diversity of stakeholders and communities consulted about these issues, including more NGOs, representatives of ICOM in Turkey, the relevant ministry authorities, and other members of the public. We can then identify more precisely where policies could be developed and integrated into the existing archaeological excavation and site management regulations, and the official museum collections management guidelines for Turkey.

Geolocation information

The Republic of Turkey, 38.9637° N, 35.2433° E

Funding details

This paper forms part of a wider PhD research funded by the Cambridge Trust and the Smuts Memorial Fund. The fieldwork undertaken in the museums was funded by Koç University.

Acknowledgements

We thank the TMoCT for giving permission to interview museum personnel working in the state museums where the interviews were conducted. We also thank the archaeologists and museum professionals interviewed for sharing valuable field experiences. Finally, we thank the 780 participants who responded to our online survey.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial interest and have not benefited from any direct applications of this research.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elifgül Doğan

Elifgül Doğan is a PhD candidate and a Cambridge Trust Scholar in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge. She is an archaeologist, specialising in museum studies and heritage management. Her PhD research investigates the problems and challenges associated with the management of archaeological human remains collections in Turkish museums. Besides human remains collections, her research interests include socio-politics of the past, ethics and conflict studies. Besides her academic work, Elif volunteers at the Duckworth Collection and Laboratory, and works as a PhD representative for various diversity and decolonisation committees across different academic organisations.

Correspondence to: Elifgül Doğan, St John’s College, St John’s Street, Cambridge cb2 1tp, UK. Email: [email protected]

Lucienne Thys-Şenocak

Lucienne Thys-Şenocak is a Professor of Cultural Heritage Management, Museum Studies and Art History in the Department of Archaeology and the History of Art at Koç University, Istanbul. She has worked on several heritage projects in the Gallipoli region of Turkey since 1997 and was the co-director of the team which began the first documentation, survey, and archaeological work at the fortress of Seddülbahir. Her publications and research interests include the patronage of architecture by imperial Ottoman women, Ottoman fortifications of the early modern era, post-First World War heritage and cultural landscapes of the Gallipoli peninsula, medical and health humanities, and sensory studies of Istanbul.

Jody Joy

Jody Joy is Senior Curator at the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, University of Cambridge. He specializes in the archaeology of north-west Europe during the first millennium BC. His main interests concern art and technology and also human remains, particularly exploring issues surrounding display and storage in museums. He has previously worked at the British Museum, where he was Curator of European Iron Age Collections for eight years.

Notes

1 Throughout this paper, the word ‘expert’ defines both academics and museum professionals and is inspired by the use of the term in Lowenthal (Citation2000).

2 The Museology Guideline (Müzecilik Klavuzu) was published by the TMoCT on 21 March 2001. https://teftis.ktb.gov.tr/TR-267740/muzecilik-klavuzu.html.

3 To see the relevant law, please see the Official Gazette (Resmi Gazete 18531), published by the TMoCT. https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/18531.pdf

4 The TMoCT granted official permission to conduct and record interviews with all museum personnel, and to publish information from these interviews. All questionnaires were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Koç University.

5 Interviews of museum personnel at three museums were conducted between 12–14 April 2016. A further interview took place on 6 March 2018. All interviews were recorded with a voice recorder. This data is kept in an external hard drive and a university administered password protected cloud storage.

6 Prior to the survey, the questions and methods were assessed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

7 It is noteworthy that the representation of belief groups among the participants significantly diverge from the official statistics pertaining to the Turkish population. The statistics shared with the European Commission in December 2021 indicates that 99% of the Turkish Nation is formed by Muslims. Although our results present an interesting case, challenging these statistics, this discussion is outside the scope of this paper. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/population-demographic-situation-languages-and-religions-103_en

References

- Aldrich, R. 2009. Colonial Museums in a Postcolonial Europe. African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 2(2): 137–56.

- Allen, A. L. 2007. No Dignity in Body Worlds: A Silent Minority Speaks. The American Journal of Bioethics, 7(4): 24–25.

- Apaydın, V. 2016. Effective or Not? Success or Failure? Assessing Heritage and Archaeological Education Programmes — The Case of Çatalhöyük. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(10): 828–43.

- Atakuman, Ç. 2008. Cradle or Crucible: Anatolia and Archaeology in the Early Years of the Turkish Republic (1923–1938). Journal of Social Archaeology, 8(2): 214–35.

- Atakuman, Ç. 2010. Value of Heritage in Turkey: History and Politics of Turkey's World Heritage Nominations. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 23(1): 107–31.

- Atalay, S. L. 2007. Global Application of Indigenous Archaeology: Community Based Participatory Research in Turkey. Archaeologies, 3: 249–70.

- Baraldi, S. B., Shoup, D. & Zan, L. 2013. Understanding Cultural Heritage in Turkey: Institutional Context and Organisational Issues. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 19(7): 728–48.

- Barilan, Y. M. 2006. Bodyworlds and the Ethics of Using Human Remains: A Preliminary Discussion. Bioethics, 20(5): 233–47.

- Biers, T. 2019. Rethinking Purpose, Protocol, and Popularity in Displaying the Dead in Museums. In: K. Squires, D. Errickson and N. Márquez-Grant, eds. Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 239–63.

- Bozoğlu, G. 2019. Museums, Emotion, and Memory Culture: The Politics of the Past in Turkey, 1st ed. London: Routledge. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429030604>.

- Brooks, M. M. & Rumsey, C. 2006. The Body in the Museum. In: V. Cassman, N. Odegaard and J. Powell, eds. Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 261–89.

- Bruning, S. B. 2017. Complex Legal Legacies: The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Scientific Study, and Kennewick Man. American Antiquity, 71(3): 501–21.

- Cassman, V., Odegaard, N. & Powell, J. eds. 2006. Human Remains: Guide for Museums and Academic Institutions. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

- Clegg, M. 2020. Human Remains: Curation, Reburial and Repatriation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Çolak, N. I. 2011. Alan Yönetiminin Hukuki Boyutu. Hukuk, Ekonomi ve Siyasal Bilimler Aylık İnternet Dergisi 108 [online]. Available at: <http://e-akademi.org/makaleler/nicolak-7.pdf>.

- Curtis, N. G. W. 2003. Human Remains: The Sacred, Museums and Archaeology. Public Archaeology, 3(1): 21–32.

- Cybulski, J. S. 2011. Canada. In: N. Márquez-Grant and L. Fibiger, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation: An International Guide to Laws and Practice in the Excavation and Treatment of Archaeological Human Remains. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 525–32.

- Doğan, E. 2018. Legislative, Ethical and Museological Issues regarding Archaeological Human Remains in Turkey. MA thesis, Koç University.

- Doğan, E. & Thys-Şenocak, L. 2019. Türkiye’de Arkeolojik İnsan Kalıntıları Yönetimi. In: A. M. Büyükkarakaya and E. B. Aksoy, eds. Memento Mori Ölüm ve Ölüm Uygulamaları, İstanbul: Ege Yayınları, pp. 521–38.

- Doğanbaş, M. 2001. Mumyalama Sanatı ve Anadolu Mumyaları. Ankara: Doğuş Matbaacılık.

- Efe, Z. 2015. Türkiye Müze ve Türbelerindeki Mumyaların Tarihi ve Bugünkü Durumları. Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 34: 279–92.

- Eldem, E. 2011. From Blissful Indifference to Anguished Concern: Ottoman Perceptions of Antiquities, 1799–1869. In: Z. Bahrani, Z. Çelik and E. Eldem, eds. Scramble for the Past: A Story of Archaeology in the Ottoman Empire. İstanbul: SALT, pp. 281–330.

- Fforde, C. 2013. In Search of Others: The History and Legacy of ‘Race’ Collections. In: L. Nilsson and S. Tarlow, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial [online]. Oxford University Press. Available at < https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569069.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199569069>.

- Fforde, C., Hubert, J. & Turnbull, P. 2002. The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Fletcher, A., Antoine, D. & Hill, J. D. eds. 2014. Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

- Fossheim, H. 2012. More Than Just Bones: Ethics and Research on Human Remains. Oslo: The Norwegian National Research Ethics Committee.

- Gazi, A. 2014. Exhibition Ethics — An Overview of Major Issues. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 12(1): 1–10.

- Giesen, M. 2013. Curating Human Remains: Caring for the Dead in the United Kingdom. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.

- Gürsu, I. 2019. Public Archaeology: Theoretical Approaches and Current Practices. London: British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara.

- Gürsu, I., Pulhan, G. & Vandeput, L. 2020. ‘We Asked 3,601 People’: A Nationwide Public Opinion Poll on Attitudes Towards Archaeology and Archaeological Assets in Turkey. Public Archaeology, 18(2): 87–114.

- Human, H. 2015. Democratising World Heritage: The Policies and Practices of Community Involvement in Turkey. Journal of Social Archaeology, 15(2): 160–83.

- Human Tissue Act [HTA]. 2004. The Stationary Office, London.

- Ikram, S. 2018. An Overview of the History of the Excavation and Treatment of Ancient Human Remains in Egypt. In: B. O’Donnabhain and M. C. Lozada, eds. Archaeological Human Remains: Legacies of Imperialism, Communism and Colonialism. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 45–55.

- Ilıcak, G. Ş. 2010. Mükemmel Halkla İlişkiler Deği̇şkenleri Bağlamında Türkiye’de Müze Halkla İlişkileri. PhD thesis, İstanbul Marmara Üniversitesi.

- International Council for Museums [ICOM]. 2017. Code of Ethics for Museums. Paris: International Council for Museums.

- Jenkins, T. 2011. Contesting Human Remains in Museum Collections: The Crisis of Cultural Authority. New York: Routledge.

- Joy, J. 2014. Looking Death in the Face: Different Attitudes towards Bog Bodies and their Display with a Focus on Lindow Man. In: A. Fletcher, D. Antoine and J. D. Hill, eds. Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum, London: The British Museum, pp. 10–19.

- Karadeniz, C. 2015. Çağdaş Müze Ve Kültürel Çeşitlilik: Arkeoloji Müzesi Uzmanlarının Kültürel Çeşitliliğe İlişkin Yaklaşımlarının Değerlendirilmesi. PhD thesis, Ankara Üniversitesi.

- Kilminster, H. 2003. Visitor Perceptions of Ancient Egyptian Human Remains in Three United Kingdom Museums. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 14: 57–69.

- Lohman, J. & Goodnow, K. eds. 2006. Human Remains and Museum Practice. London and Paris: Museum of London and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

- Lonetree, A. 2012. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. University of North Carolina Press.

- Lowenthal, D. 2000. Stewarding the Past in a Perplexing Present. In: D. Lowenthal, E. Avrani, R. Mason, & M. de la Torre, eds. Values and Heritage Conservation: Research Report. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, pp. 18–25.

- Moore, C. M. & Brown, C. M. 2007. Experiencing Body Worlds: Voyeurism, Education, or Enlightenment? Journal of Medical Humanities, 28(4): 231–54.

- Orbaşlı, A. 2013. Archaeological Site Management and Local Development. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites, 15(3–4): 237–53.

- Overholtzer, L. & Argueta, J. R. 2018. Letting Skeletons out of the Closet: The Ethics of Displaying Ancient Mexican Human Remains. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 24(5): 508–30.

- Özbudun-Demirer, S. Ö. 2011. Anthropology as a Nation-Building Rhetoric: The Shaping of Turkish Anthropology (from 1850s to 1940s). Dialectical Anthropology, 35(1): 111–29.

- Özdemir, M. Z. 2005. Türkiye’de Kültürel Mirasın Korunmasına Kısa Bir Bakış. Planlama, 31: 20–25.

- Özdoğan, M. 1998. Ideology and Archaeology in Turkey. In: L. Meskell, ed. Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. New York: Routledge, pp. 111–23.

- Özkasım, H. & Ögel, S. 2005. Türkiye’de Müzeciliğin Gelişimi. İTÜ Dergisi, 2(1): 92–102.

- Pardoe, C. 2013. Repatriation, Reburial, and Biological Research in Australia. In: L. Nilsson-Stutz and S. Tarlow, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Death and Burial [online]. Oxford University Press. Available at < https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199569069.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199569069-e-41 > .

- Patterson, A. R. 2007. ‘Dad Look, She’s Sleeping’: Parent–Child Conversations about Human Remains. Visitor Studies, 10(1): 55–72.

- Pulhan, G. 2019. The Public and Archaeology: Some Examples from Current Practices in Turkey. In: I. Gürsu, ed. Public Archaeology: Theoretical Approaches & Current Practices. London: British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, pp. 41–50.

- Restall Orr, E. 2004. Honouring the Ancient Dead. British Archaeology, 77: 39.

- Ricci, A. & Yılmaz, A. 2016. Urban Archaeology and Community Engagement. The Küçükyalı ArkeoPark in Istanbul. In: M. Alvarez, A. Yüksel and F. Go, eds. Heritage Tourism Destinations: Preservation, Communication and Development. Oxfordshire: CABI, pp. 41–62.

- Sabry, M. 2021. Uproar after Scholar Bans Excavation of Egyptian Mummies. Al-Monitor [online], 25 January [accessed 1 February 2021]. Available at: <https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2021/01/egypt-scholar-islam-ban-digging-mummies-pharaos-archeology.html>.

- Shaw, W. 2007. Museums and Narratives of Display from the late Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic. Muqarnas, 24: 253–80.

- Shaw, W. K. 2011. National Museums in the Republic of Turkey: Palimpsests within a Centralized State. Building National Museums in Europe 1750–2010. In: P. Aronsson and G. Elgenius, eds. Conference Proceedings from European National Museums: Identity Politics; the Uses of the Past and the European Citizen. Bologna: Linköping University Electronic Press, pp. 925–51.

- Squires, K., Errickson, D. & Márquez-Grant, N. eds. 2019. Ethical Approaches to Human Remains: A Global Challenge in Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology. Cham: Springer.

- Stumpe, L. H. 2005. Restitution or Repatriation? The Story of Some New Zealand Maori Human Remains. Journal of Museum Ethnography, 17: 130–40.

- Swain, H. 2016. Museum Practice and the Display of Human Remains. In: H. Williams and M. Giles, eds. Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society [online]. Oxford University Press. Available at: <https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198753537.001.0001/isbn-9780198753537-book-part-16>

- Tanyeri-Erdemir. T. 2006. Archaeology as a Source of National Pride in the Early Years of the Turkish Republic. Journal of Field Archaeology, 31(4): 381–93.

- Tatham, S. 2016. Displaying the Dead: The English Heritage Experience. In: H. Williams and M. Giles, eds. Archaeologists and the Dead: Mortuary Archaeology in Contemporary Society [online]. Oxford University Press. Available at: <https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198753537.001.0001/isbn-9780198753537-book-part-17>

- Thomas, D. H. 2001. Skull Wars Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and The Battle for Native American Identity. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Thys-Şenocak, L. & Doğan, E. 2018. Archaeology, Museums and Tourism on the Gallipoli Peninsula: Issues of Human Remains, Ordnance, and Local Decision-Making. In: B. Akan, K. Piesker, D. Göçmen, and S. Sezer-Altay, eds. Heritage in Context 2: Archaeology and Tourism. Istanbul: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, pp. 289–313.

- Ünsal, D. 2008. Museums and Belonging: Visitors, Citizens, Audiences and Others. In: P. R. Voogt, ed. Can We Make a Difference?: Museums, Society and Development in North and South. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, pp. 64–75.

- Üstündağ, H. 2011. Turkey. In: N. Márquez-Grant and L. Fibiger, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation: An International Guide to Laws and Practice in the Excavation and Treatment of Archaeological Human Remains. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 455–67.

- Üstündağ, H. & Yazıcıoğlu, G. B. 2014. The History of Physical Anthropology in Turkey. In: B. O’Donnabhain and M. C. Lozada, eds. Archaeological Human Remains: Global Perspectives. New York: Springer, pp. 199–211.

- Walker, P. L. 2000. Bioarchaeological Ethics: A Historical Perspective on the Value of Human Remains. In: M. A. Katzenberg and S. R. Saunders, eds. Biological Anthropology of the Human Skeleton. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–40.

- Walker, P. L. 2004. Caring for the Dead: Finding a Common Ground in Disputes Over Museum Collections of Human Remains. Documenta Archaeobiologiae, 2: 13–27.

- Wallis, R. J. & Blain, J. 2011. From Respect to Reburial: Negotiating Pagan Interest in Prehistoric Human Remains in Britain through the Avebury Consultation. Public Archaeology, 10(1): 23–45.

- Wergin, C. 2021. Healing through Heritage?: The Repatriation of Human Remains from European Collections as Potential Sites of Reconciliation. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 30(1): 123–33.

- Wintle, C. 2013. Decolonising the Museum: The Case of the Imperial and Commonwealth Institutes. Museum and Society, 11(2): 185–201.

- World Archaeological Congress [WAC]. 1989. The Vermillion Accord, Archaeological Ethics and the Treatment of the Dead. In: A Statement of Principles Agreed by Archaeologists and Indigenous Peoples at the World Archaeological Congress, Vermillion, USA [accessed 1 February 2021]. Available at: <https://worldarch.org/code-of-ethics/>

- Zhuravska, N. 2015. Bodies in Showcases: Objectification of the Human Body from a Cognitive Perspective. Amsterdam Bulletin of Ancient Studies and Archaeology, 1: 24–32.