Abstract

This article examines how collaboration with Public Service Media structures the relationship between archaeologists and the public. To be able to understand such collaborations, we have studied an online news production by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Always Viking’, covering one week of excavating the recently discovered Viking ship at Gjellestad in Norway. The findings suggest that the journalists, even when doing an online-first production, mostly worked according to a broadcasting media logic, with few opportunities for the public to participate. In this, they prioritized the audience’s ‘perceived reality’ over the archaeologists’ ‘referential reality’ (Holtorf, Citation2007: 151–52) to secure a broader reach. Some elements of the format supported more reciprocal audience participation, however, by combining a livestream with open and ongoing Q&A sessions. This opened for more unmediated, direct, and meaningful encounters between the archaeologists and the public. Overall, the study shows that the long and mutually beneficial collaboration between public service broadcasting and archaeology (Piccini, Citation2007) can be strengthened by undertaking joint experimentation and exploration of participatory communication models online.

Introduction

The recent high-profile excavation of a large Viking ship at Gjellestad in Norway, the first of its kind in over 100 years, has given the Museum of Cultural History (MCH) the opportunity to explore new ways to share ongoing archaeological excavations with the public. One such opportunity presented itself to the museum when the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s (NRK) news department suggested producing one week of livestreaming, Q&As, celebrity guests, and posts on social media in 2020, as ‘Always Viking’. The concept was an adaption of the ‘Always Together’ format developed by NRK during the COVID-19 pandemic to support young audiences isolated at home. This article will explore this collaboration in depth to shed light on how it structured the relationship between the archaeologists and the public.

We address well-known issues in the literature concerning the relationship between archaeology and the media and, more specifically, Public Service Broadcasting (PSB). There seems to be a consensus among researchers that in the early days of PSB, archaeological institutions and broadcasters found common ground in their mandates to educate and inform the public (Clack & Brittain, Citation2007; Kulik, Citation2006; Rogers, Citation2019). Further, when public service broadcasters moved on from a paternalistic educational model to an entertainment model in the 1980s, factual television series focusing on archaeology continued to be an attractive format for broadcasters. In the 1990s and 2000s, PSBs were able to harness archaeology’s strong position in popular culture — its ‘archaeo-appeal’ (Holtorf & Green, Citation2005) — to keep viewers onboard in a deregulated and commercialized media landscape. The period has been characterized by Karol Kulik (Citation2006) as a golden age for archaeology on television.

Since the 2000s, with the increased importance of online and mobile media, PSBs have been challenged to find ways to attract new audiences online. The development has led broadcasters to actively develop their online services, most importantly for opening dialogue and online communication with their audiences (Enli, Citation2008; Moe, Citation2008). This has led policy-makers and researchers to an extended understanding of PSB, captured by the more technology-neutral concept Public Service Media (PSM). Terry Flew (Citation2011: 215) characterizes PSM as a ‘wide-ranging transformation of public service broadcasters from entities with a mission of serving the nation through radio and TV, to public service media organizations contributing to a flourishing digital commons and providing content across multiple platforms to diverse publics’. Further, Karen Donders (Citation2021: 84) has emphasized PSM as the means to provide meaningful (not superficial) participation to its publics, reframing them as citizens rather than consumers. Engagement via social media becomes a key priority for PSM services, to reach younger and hard-to-reach audiences with content natively created for these platforms (Belair-Gagnon, et al., Citation2019). In this, PSMs often need to use platforms owned by powerful companies like Meta, Snap Inc., Alphabet and Apple, entities following a commercial logic at odds with the ideals of PSM. This challenge has been acknowledged by most PSM outlets, who are still struggling to develop strategies to cope (Donders, Citation2019). In summary, despite the challenges posed by platformization, the development of PSM promises opportunities to innovate with technology and content, and find ways to interact with the public.

The relationship between factual television produced by PSBs and archaeology is well described, most recently by Kathryn Elizabeth Rogers (Citation2019), and several studies of using social media to disseminate directly from archaeological excavations have been undertaken (Gruber, Citation2017; Wakefield, Citation2020). Still, little research has been undertaken investigating the opportunities for archaeological institutions to achieve a more reciprocal relationship with the public online by collaborating with public broadcasters that are re-inventing themselves as Public Service Media (PSM). This article will therefore shed light on how collaboration PSM structures the relationship between archaeologists and the public by investigating NRK’s online news production ‘Always Viking’ (AV).

In the following, we will give a fuller description of the background for the collaboration with NRK, before outlining a framework for understanding the relationship between archaeologists and the public. After an account of the AV project, we discuss how it structured the relationship between archaeologists and the public, focusing on 1) how the media format supports reciprocity and dialogue, 2) whether the use of celebrities as intermediaries strengthens the archaeologists’ relationship with the public, and 3) whether the collaboration supported the museum’s ongoing work of building an online platform where followers can interact with archaeologists.

Making the Gjellestad excavation available to the public

When the Gjellestad ship was found with the help of ground-penetrating radar (undertaken by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research) in 2018, news of the discovery was broadcast widely and soon went viral (Solås, et al., Citation2020). The last such find of a ship burial from a monumental burial mound was in 1903 when the Oseberg ship was discovered and subsequently excavated in 1904. In comparison to the Oseberg ship, however, analysis of a wood sample extracted from the keel of the Gjellestad ship during a test survey of the site in 2019 showed extensive spread of fungi and a rapid state of decomposition (Bjørdal, Citation2019). Plans were soon set in motion to excavate the site to investigate and preserve whatever remained of the find. The Museum of Cultural History (MCH), responsible for excavations in south-eastern Norway, including Gjellestad, quickly understood that this would be a one-of-a-kind event and planned from the outset to share the experience with as broad an audience as possible. Subsequently, after funding for excavating the ship was secured in spring 2020, the museum quickly hired a designated dissemination coordinator to communicate news and information from the project. A bilingual site dedicated to the excavation was put in place on MCH’s main website, and social media was actively used to further spread the stories and information posted on this website (Rødsrud, Citation2020). Before AV was hosted in September 2020, the Norwegian version of the museum excavation website had 20,000 individual visitors, while the English version had close to 12,600. As the Museum of Cultural History consists of two museums, the Historical Museum and the Viking Ship Museum (renamed as the Museum of the Viking Age when temporarily closed in 2022 — scheduled to reopen in 2026), the latter was chosen as a venue for presenting the Gjellestad excavation on social media. In particular, the Facebook eventFootnote1 ‘The Gjellestad Ship Project’ hosted by the Viking Ship Museum was actively used to post frequent updates, reaching more than 2900 Facebook users. Video updates quickly became popular and reached from 3500 to 120,000 viewers per video. Here, the most reached demographic was the age group 25–54. To reach beyond the Facebook event hosted by the Viking Ship Museum, the videos need to be re-posted in larger and more general Facebook groups with a higher and different segment of viewers and readers.

In spring 2020, the journalists at NRK’s regional news division indicated some interest in covering the dig and made a first contact with the Director of MCH to make this happen. They suggested adapting a media format developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, ‘Always Together’, to create a real-time, live, and ongoing online coverage of the excavation. The format was simple, combining a live video stream from a studio, a curated Q&A, and a news feed that could be accessed on multiple platforms. During COVID-19 lockdowns, the format was developed as an attempt to bring people together (Sprus, Citation2020). The service was extensively used and became very popular, especially with younger audiences. After a series of meetings between MCH and NRK to clarify roles and expectations, NRK decided to produce a first week of AV, starting on 7 September 2020, which would include cross-media news coverage on radio, television, online, and on social media.

How to understand the relationship between archaeologists and the public

To shed light on how collaboration with Public Service Media (PSM) structured the relationship between archaeologists and the public in AV, we rely on concepts developed in the field of Public Archaeology. The term public archaeology has been in use since it was first introduced as a descriptor of a methodological approach by Charles McGimsey in the early 1970s (Merriman, Citation2004: 3). What exactly public archaeology entails is still an ongoing debate and a variety of definitions of the term have been proposed as it has developed into a field of its own (see Moshenska, Citation2017: 1–2; Oldham, Citation2017: 4–8). For the purposes of this article specifically, the definitions of public archaeology that resonate the most have been narrowed down to public archaeology as any ‘arena of archaeological activity that interacts or has potential to interact with the public’ as suggested by Tim Schadla-Hall (Citation1999: 147), and Gabriel Moshenska’s (Citation2017: 3) more recent ‘practice and scholarship where archaeology meets the world’. Expanding on the concept of public archaeology as an intersection or bridge between the general field of archaeology and the world at large, Reuben Grima (Citation2016: 57) suggests that public archaeology needs to be a part of ‘the essential toolkit of the overall competencies’ required for working within the archaeological discipline, and provides a map of previously and currently prevalent models for the relationship between archaeologists and the public.

The first model outlined by Grima (Citation2016: 51–53), termed the ivory tower model, describes the archaeologist’s relationship with the public as one where archaeologists act as specialists with privileged access to information which they may or may not choose to share. Within this model, actually communicating with the public is not considered a priority but rather something that others could take care of while the archaeologist gets on with the actual work (Grima, Citation2016). In contrast, within the second model, the gateway or deficit model, the archaeologist serves as a conduit between archaeological material and the wider public. This entails cherry picking, simplifying, and/or editing archaeological knowledge in order to make it ‘suitable for public consumption’ (Grima, Citation2016: 53–54). Both models are frequently regarded as problematic as they not only present archaeology as something to be gatekept by specialists, but also as something that is inherently difficult for the public to comprehend without professional translation. To accommodate this, a third model has been proposed: the multiple perspective model (Merriman, Citation2004: 6–8). Here the archaeologist is regarded as a part of a wider community in which the general public is also included, where a variety of perspectives, attitudes, and needs are recognized and addressed, depending on the audiences that are being engaged (Grima, Citation2016). This not only acknowledges the participatory potential of public archaeology but also the beneficial nature of a reciprocal relationship between scientific knowledge and popular culture; regarding archaeological knowledge as something that should not be monopolized as such. As noted by Mark Oldham (Citation2017), there is still a need to bridge the gap between practice and theory in including the more theoretically oriented multiple perspective model to the archaeologist’s essential toolkit.

A recent discussion has addressed how the models matter in digital media with Chiara Bonacchi (Citation2017) outlining two approaches, echoing the dichotomy between the top-down and bottom-up models already described. The first top-down approach is referred to as ‘broadcasting’ and essentially entails the transmission of messages from a sender to receiver through a certain type of medium, in this case digital platforms. In this approach, feedback is mainly focused on commentary of the information sent but seldom concerned with active collaboration with the actual receivers themselves. She breaks the second approach, the bottom-up participatory approach, into three main types, all of which, in comparison to the previous approach, rely on active feedback. The first, contributory participation, entails members of the public assisting with the completion of tasks such as data collection; the second, collaborative participation, concerns members of the public helping with, for example, the interpretation of data or development of new methods and practices. Finally, the third subgroup, co-creative participation, pertains to activities that are both planned and developed by all members involved in a certain project such as members of the public, non-profit organizations, and larger institutions.

In summary, is worth noting how the historical communication models of both Public Archaeology and Public Service Broadcasting have changed in similar ways since the early 1990s, reflecting a changing media landscape, going from top-down, specialist-led communication models to participatory, multi-perspective, and co-creative communication models.

Methodology

Data collection

The three authors had different roles and responsibilities during the AV week. Karlsen was an external researcher with no role in the excavation or in NRK’s AV production, Havgar was the excavation’s dissemination coordinator, and Rødsrud led the excavation project. In addition, Havgar and Rødsrud were actively involved with the AV production as experts and interviewees. Therefore, it largely fell to Karlsen to coordinate the data collection and, when Havgar and Rødsrud were able, to confer with them to ensure the continuity of the account.

Karlsen took an open and flexible, not pre-structured, approach to making observations, taking few decisions beforehand when it came to theories and topics. He took the role akin to what Robson (Citation2002: 318) labels a ‘marginal participant’, of being ‘largely passive, though completely accepted’ — a role similar to being a passenger on a train or a spectator at a concert. There was some scepticism from the NRK project manager, however, who was afraid that the presence of a researcher would draw attention away from keeping the dialogue with the audience going. Karlsen stayed close to where the NRK team worked together with Havgar in monitoring the livestream and to answer incoming questions in the Q&A. In addition, he was able to move around freely to observe and ask simple clarifying questions of both crews, like ‘what are you doing now?’, sometimes becoming more a participant-as-observer than marginal participant. He took extensive field notes along with photos, videos, and, at regular intervals, screenshots of how AV was framed by the top news desk at NRK, and how high up it was placed on NRK’s news website’s front page. During the AV week, Havgar and Rødsrud were participants-as-observers and sometimes complete participants (Angrosino, Citation2007: pt 1283). When engaging as a participant-as-observer, the activities as researcher are not hidden and are acknowledged by the other participants. A complete participant can at times forget the research agenda, being fully engaged with the ongoing activities.

To be able to document more of the activities not taking place in the tent during the AV week, we have relied on observations made by Havgar and Rødsrud through their participation in the project. By attending meetings, exchanging emails, making decisions, etc., they have collected a rich set of what can be categorized as project documentation. Further, their insights and reflections with regard to the project were collected by interviews with Karlsen shortly after the AV week was concluded, and refined through the process of all the authors interpreting the collected data material. To collect this type of information from NRK’s team, Karlsen conducted semi-structured interviews with the project manager, the programme host, the main journalist, and the head of digital development and innovation at the NRK news department, shortly after the AV project ended. The interview guide was prepared with a focus on whether, and if so how, NRK’s AV contributes to innovating new journalistic methods, tools, and techniques. The guide also covered how the informants had experienced the collaboration with MCH and their rationale for doing the project in the first place.

The interviews were transcribed and imported into an application providing tools for doing computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS). Further, the field notes were converted into text, cleaned up with some additions and amendments to secure the readability of the data. Photos and screenshots were added to the field notes according to the timestamps noted when observing. In analysing the data, we followed John Creswell’s (Citation2009) suggestions for what steps to take. The transcripts and field notes were read to get a general sense of the data. Then a more thorough reading of answers and observations informed the development of bottom-up thematic codes, which again were used to select and group statements and observations, giving structure when summarizing the results.

Results

Initially, we considered describing the project by levels of analysis, from the work going on in the tent during the week of streaming to the collaboration on an institutional level between NRK and MCH. We chose, however, to describe the project chronologically to provide cohesion and clarity. The account will therefore have the following structure: 1) the planning of the AV week, 2) the AV week itself, and 3) what happened afterwards, focusing on dialogues concerning possible extensions of the project. Since information about the project and its participants is public, we could have used real names in the following account, but we have chosen to anonymize most names, except for the two participants who are also co-authors of this article.

Table 1 LIST OF INFORMANTS

Before the week of excavations

Even before the excavation was under way, a small group of journalists and producers from NRK with a special interest in cultural heritage, archaeology, and Gjellestad understood that the dig was worthy of broader news coverage, being one of the most important archaeological investigations of its kind in the last 100 years. In the interview, Alex, the person in charge of digital development in the NRK news department, said the excavation was ‘very exclusive, it hasn’t happened in a hundred years and at the same time it’s delightfully nerdy’. He was therefore disappointed when he first suggested the story to one of his colleagues and was met with disinterest:

I tested the idea on … one of my concept developers at NRK who has such good instincts … whether this is interesting or rubbish, and she reacted sharply, revealing that she can’t stand archaeology. (Alex)

Accordingly, the request to use resources on covering the dig was turned down by NRK’s managing editors, being too much of a niche to be of interest to the broader public. The group was not discouraged by this, however, and managed to mobilize resources for covering the excavation anyway. The key to their success seems to have been that they developed a concept that could be rationalized as a low-cost innovation experiment in accordance with NRK’s mandate to be first in digital innovation and explore new ways to reach and engage young audiences on social media. The combination of online livestreaming, real-time questions and answers (Q&A), using the site as a live field studio, and giving priority to publishing content on Snapchat, were seen as such an innovation experiment. Further, they came up with the idea to invite Norwegian celebrities associated with Vikings in popular culture to visit the site during the week and to use this to mobilize broader audiences. They managed to recruit celebrities from the blockbuster series Game of Thrones and Norsemen (Vikingane in Norwegian). The programme host explains the rationale behind the concept:

… but I think that for NRK, which should offer something for everyone, it is important that one … I think at least it’s cool that one considers covering a Viking excavation. … I think everyone has an inner nerd and for us to have the guts to focus on niche things, with elements that allow us to reach broadly, is interesting. (Per)

The concept was pitched in a high-level meeting between NRK and MCH in spring 2020. One of the senior members of the NRK team describes the pitching:

We pitched what we wanted to do. They said they were ready for anything. They saw how Corona threatened their dissemination goals, and we invited them to dance. (Alex)

MCH accepted the invitation and from then on both parties were committed to the collaboration. Initially, NRK planned to stream the first week of the dig, but quickly understood that the greatest discoveries would not be made early on, with mere removal of the topsoil. After some back and forth, they decided to go for the week when the archaeologists started to uncover the remains of the ship burial chamber, with the greater chance that something well preserved and interesting would surface.

Kristin, The AV project leader at NRK, describes how the planning gained momentum during the summer (after the excavation was under way, but before the AV week) with the addition of journalists and ideas for what to produce during the week, mostly to add to the wider cross-media coverage of the event. The archaeologists, on their part, did not contribute directly to this planning but were in general positive about increasing the reach on multiple platforms, both new and old. Some of the planning involved the excavation team directly, however, and agreements were made in meetings and through email exchanges.

The first set of agreements concerned the practicalities of rigging the infrastructure and equipment needed for the production. The available space was limited both inside and outside the construction tent where the excavations took place (see ), but MCH did what they could to accommodate NRK’s requests. Producing the livestream required multiple cameras on tripods, microphones on tripods, cables, and a big chunk of the available 4G bandwidth. In addition, the NRK crew needed a space within the tent to follow the process closely. Parking spaces for the NRK crew were provided just outside the tent, as was office space in the barracks for the project manager to communicate with the newsrooms involved and the programme host preparing the daily summaries together with Rødsrud and Havgar. In sum, the production was going to take up a considerable amount of the space already in use by the excavation project and crew.

Figure 1 Exterior of the Gjellestad excavation tent with accompanying parking space and barracks. Photo: Joakim Karlsen.

The second set of agreements concerned clarifying Havgar and Rødsrud’s areas and degrees of involvement in the production. There was a clear division of roles between Havgar and Rødsrud, where both were going to answer questions directly related to the dig, but Rødsrud would answer questions related to political aspects of the project. Havgar was going to be responsible for helping with the Q&A stream, in between tending to her ongoing tasks, updating MCH’s media channels, and coordinating and hosting on-site guided tours. Both Havgar and Rødsrud were going to be on-deck for planning and performing the live-studio session every afternoon from Monday to Thursday.

The third set of agreements concerned the livestream itself. In general, MCH wanted the cameras and microphones to be a bit removed from the ongoing work both in space and time. The excavation crew was uncomfortable with the idea of their casual, everyday work chat and discussions being broadcast on an internationally accessible livestream and expressed concerns that this could, potentially, negatively affect the crew’s social dynamic and work performance. As such, it was requested that NRK placed the microphones at a distance that would allow the audience of the livestream to hear the noise of voices, but not discern actual conversations. In addition, MCH set a demand that the stream had a one-minute delay, so that they could take it off air if a safety hazard or an injury should occur. NRK agreed to these terms.

During the week of excavations

The AV week was covered through a livestream on the website NRK.no, which broadcasts both online and on TV, features on radio, and adapt information to younger audiences on social media. The programme host, recruited from the NRK N17 newsroom (set up to reach 17-year-olds with news), explains the strategy to reach a young demographic:

I was constantly thinking about how I would use Snapchat, which is our main platform for reaching young people. Before the week began, I made what is called a snap special with 10 to 15 slides for a snapchat story … devoted to the Gjellestad excavation. So, I brought with me the excavation project manager, and made a Snapchat story where I showed the audience the excavation site. We got to see a bead they had recovered. [Rødsrud] explained who could be buried in the ship grave, and the reason for conducting the dig. I gave them a big visual and entertaining package on what was going on down there. (Per)

The live coverage on NRK.no also included audience dialogue and interaction with a Q&A section hosted by an NRK journalist, Espen, and the Gjellestad project’s dissemination coordinator, Havgar. There was also a thirty-minute section every day where the background for the dig, general questions about Vikings, excavation techniques, and the discoveries of the day were discussed. An NRK reporter, Per, hosted these interview sections where Havgar and Rødsrud were the main participants, in addition to celebrity guests visiting on Tuesday and Thursday. Alex, responsible for the concept, explains the rationale behind adding the Q&A to the livestream:

Audience dialogue is a clear strategic point at NRK, which we try to incorporate where we can. That’s why it had to have audience dialogue. Livestream alone does not work. We must have a commentary track … . The dramaturgy is not of a football match, it’s a seven-and-a-half-hour livestream from an excavation. (Alex)

Alex points to an evident challenge when livestreaming on site excavations which is that digging is a slow process, with little certainty of whether or when discoveries are going to be made. At the time when the AV week was about to commence, it had become evident that the excavation had not proceeded as much as estimated, with the uncovering of the best-preserved remains of the ship likely in the future. The emergent results of the dig at the time when NRK was ready to produce and publish AV were therefore somewhat underwhelming compared to what the production crew had expected. The difficult and meticulous work that was going on, excavating and preserving the remains of the rivets that had held the construction together, was not very TV-friendly. Even if the poor preservation conditions of the ship burial, slowly uncovered by the excavation, made interpretations less straightforward for the broader audience, NRK chose to go through with the production. Espen was confident that this was the right choice to make and contributed a rationale that the archaeological process would be interesting enough in itself.

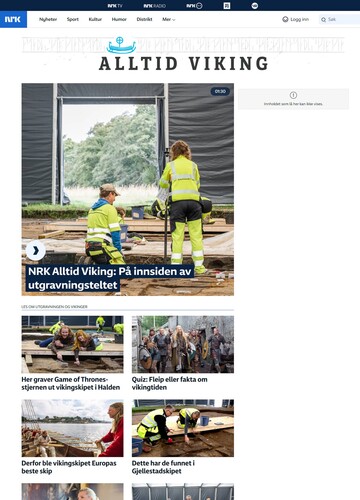

The main access point to AV was the front page of the website NRK.no with a vertical section in the main column of the page including the latest stories from the dig and a link to the AV landing page (see ). Most of the time, the section was placed high up on NRK.no, but rarely in the top three rows. The decision of how high up in the news feed the section was going to be at any time was being made by the central news desk in Oslo. During the AV week several news stories broke that pushed the section down on NRK.no (a celebrity trial, the King’s illness, and a bus strike) and Alex put it like this:

We struggled with the news agenda that week. … The week started with a bus strike on Monday and ended on Friday with the King being admitted to hospital. … We had hoped to prioritize [AV] higher on NRK.no, but it was not possible with everything that was happening. (Alex)

Below we summarize the AV week according to the main elements of the NRK Always media format: the stream, the Q&A, and the live field-studio summaries.

Figure 2 The landing page for NRK: Always Viking. Although the site is still up, the Q&A section, marked on the image with a greyed-out box and an exclamation mark, was shut down soon after the livestream ended and is no longer visible on the page. Photo: Screenshot, nrk.no/alltidviking.

The stream

On site, there was little physical interference between the production of the stream and the ongoing excavation work (see ). The cameras and microphones were fixed in the same places in the tent, quickly blending into the background. One of the cameras was used to produce the live studio footage but was moved only when needed for this purpose. When it comes to the question of privacy, several of the archaeologists told Karlsen that they were acutely aware of the cameras and microphones and suppressed normal behaviours, like cracking jokes and airing frustration. At one point, one of the lead archaeologists working in the front of the ship made some unexpected finds, changing his working hypothesis, which demanded reinterpretation and re-planning, but felt that he had to muffle his urge to share his concerns with other co-workers.

The Q&A

The Q&A was accessible on the AV landing page in a separate column to the right or beneath the stream, depending on screen size. The public started asking questions from the outset on Monday morning and the questioning continued through the week. Most of the questions concerned the archaeological work undertaken and how to interpret the findings made so far. A lot of questions aimed to clarify what people saw in the stream: Why do you use flags? What are the plastic cups? Why do you leave walls inside the ship? Why are you covering up the areas you are not working on? etc. Furthermore, people were curious about the main method applied (uncovering one layer at a time) and how everything was documented. There were many questions about interpretations: Do you know who’s buried? How big is the ship? How do you know the ship has been plundered? How old is the ship? Do you expect to find food? Do you expect to find textiles? How does the Gjellestad ship compare to the ships already found? There were also a few examples of questions requiring more in-depth answers from Havgar: How can you tell the difference between marks of plundering and marks from farming? Why do you expect to find a burial chamber in the bottom of the ship? Does this mean that the chamber was 20 cm high? Why did you find animal bones so close to the surface? What does this say about where animals were placed in ship burials? Were the ships used for burials built for this purpose or were they decommissioned used vessels? These questions, however, requiring more elaborate answers, rarely triggered follow-up questions from the same person. All in all, the questions attested to people’s interest in learning more about the archaeological process and interpreting the discoveries being made. During the week it became evident that a few school classes were also following the stream, something that was regarded as especially valuable by the NRK team.

The collaboration between Espen, the journalist, and Havgar, the archaeologist responsible for dissemination for the museum, was established early on the first day. After getting a quick introduction and access to the Q&A tool by Espen, Havgar started answering questions immediately. Espen was generally surprised by Havgar’s willingness and ability to contribute to the Q&A and summarized her contribution in the interview:

… she was going to sit there from 12pm to 13pm, and I was going to do the rest. So, I was a bit surprised when she sat there from the start of the day because she liked it. Then she came and went when she had other tasks, … she worked with me when she had the opportunity, and when not, I could ‘hold the fort’. (Espen)

The journalist and the archaeologist worked side by side in answering questions from the audience, and, when needed, involved Rødsrud and other members of the excavation crew to provide appropriate answers. When Havgar was not there, Espen walked the 5–6 metres to the excavation area (see ), and got the answers he needed: What did they find now? What is the use of the many plastic cups placed evenly across the ship footprint? and Who brought the cool pirate flags used as markers?

Live field studio summaries

The third major element of the production was the daily summaries with the site itself becoming a studio. The summaries focused on ‘discoveries made during the day’, the celebrity visitors being interviewed by the programme host, and the visitors doing some digging themselves while talking to archaeologists (Rødsrud and Havgar) (see ). The summaries were prepared by Per, in collaboration with Rødsrud and Havgar, sometimes leaving the tent together to plan what was going to be focused on and how. This collaboration was smooth with reciprocal respect and understanding between the programme host and the two archaeologists. Per took care to be open and curious when it came to topics and examples, and explicitly humble when it came to the archaeological expertise of Havgar and Rødsrud.

I think my role in this is to be the envoy of the audience, of asking questions the public wants answers to, then they [Havgar and Rødsrud] will shine in their expert roles, me being an audience envoy wondering what is going on. (Per)

The fact that the archaeologists were not directly involved in planning and preparing the celebrity visits led to some misunderstandings and frictions, however. They agreed that it was a good idea to invite celebrities to attract new audiences, but after two unpredictable events during the first visit, they saw the need for being more engaged in managing the celebrities’ expectations. The archaeologists’ attempt to certify more control over the celebrity visits was met with resistance from the NRK team, however, who did not want Havgar and Rødsrud to intervene with the visitors before the live coverage and gave only minor updates to what the celebrities were going to be asked and talk about. They did not give any explanation or reason for resisting the request.

Figure 5 Havgar and Rødsrud in conversation with Per on site during one of the live field-studio summaries, flanked by some of the AV production team, and excavation crew. Photo: Joakim Karlsen.

The first incident occurred at the excavation pit itself, when Game of Thrones actor Kristofer Hivju exclaimed that he would not stop before picking up a sword and increased the pace of his digging. The plan had been to let Hivju and his wife, Gry Molvær Hivju, a well-known Norwegian journalist and popular science disseminator, participate in some digging while Rødsrud explained the importance of excavating layers separately. Rødsrud had to intervene and stop him, however, before a new layer was breached. Later, when helping with sifting through some soil, Hivju shook the ‘sifting screen’ so hard that he lost control and tipped it over. Luckily, Rødsrud had made sure that it was filled with topsoil that had already been sifted. This visit stands in sharp contrast to the second visit when the celebrity visitor, Norsemen actress Silje Torp, curiously asked questions about how archaeologists work and how archaeologists feel about the way Vikings are portrayed in popular media. For further discussion it is important to note how NRK’s team used the incidents occurring in the first visit to actively promote AV on social media and on NRK.no (Her går det galt for Kristofer Hivju, Citation2020).

Engagement figures for main elements of the format

Karlsen checked the number of viewers of the stream from time to time and noted the figures, ranging from around 400 to about 1000. It is difficult to assess how the stream was used, by whom and by how many. Whether the same crowd followed the stream or whether a lot of different people checked in during the week is unknown. Engagement with the Q&A is well documented, with 412 questions answered, asked by 288 individual persons. Forty-nine visitors asked more than one question (39%), 21 more than two questions (21%), and the top five contributors asked 46 questions in all (11%). NRK has given us high level figures when it comes to engagement with AV on social media. A total of 700,000 viewers watched Facebook videos and 150,000 viewers saw the Snapchat stories. Forty per cent of the viewers on Facebook and 90 per cent of the viewers on Snapchat were under thirty years old. We do not have numbers when it comes to likes, comments etc. on these two social media platforms. The articles posted on NRK.no during the week were read by 680,000, with only 15 per cent of readers being under thirty years old. Data on reading times from NRK show that, in general, readers read the whole article. The total reading time for all the articles was ten minutes and forty seconds with an expected reading time of ten minutes and forty one seconds. In addition to this, NRK produced television and radio news stories, reaching the ordinary news-consuming audience, usually about 40 per cent of the Norwegians on any day. In summary, AV reached a large audience in addition to smaller crowd following the stream day to day and with some of them posting questions and comments to the archaeologists. The numbers are remarkably high in comparison to MCHs own outreach on social media (with the most popular posts reaching 120,000 viewers), but also compared to the views (115,000) created by the Must Farm excavation in Cambridgeshire, England 2015–16 (Wakefield, Citation2020: table 3).

After the excavation

After the AV week both teams were keen on doing another week of AV towards the end of the excavation. In addition to many school classes following the stream, there were also enquiries from senior centres and online viewers from a broad range of age groups that called for continued broadcasts, indicating even broader audiences than anticipated by NRK.

A suitable event for further AV coverage could have been the raising of the keel, with more action and striking visuals. The whole process of raising the keel, with the use of advanced archaeological tools and techniques, could be the type of event that would fit an ongoing livestream. The archaeologists kept the NRK team informed about the progress and they, on their part, attempted to mobilize resources for another week of AV. In this, they emphasized reaching out to Norwegian school classes as a justification, based on how they achieved this during the first week. These attempts failed, however, due to the ongoing summer vacation impeding schools from following the event, and other commitments for the programme host, like planning coverage of the upcoming parliamentary elections. The archaeologists were a bit disappointed, but at the same time relieved. They knew the raising of the keel was going to be a demanding and complex process, needing their full focus, and with an unpredictable time schedule. As a second AV week would not occur, they decided instead to livestream the extraction of the largest keel piece on their own, using the excavation’s previously mentioned Facebook event. As of April 2023, the stream has reached an audience of 8500.

Discussion

We will now discuss how collaboration with Public Service Media (PSM) structured the relationship between archaeologists and the public in the case of AV. As has become evident, there are no straightforward and unified answers to this. AV was a complex, multifaceted, and heterogenous news production with video stream, Q&A, live reporting (with and without celebrities), and the production of news for multiple platforms simultaneously, the web, Snapchat, radio, and television. After categorizing how public participation was structured by AV, we will highlight two aspects of AV that mattered to the archaeologists’ public encounters during AV, the journalists’ use of celebrities to attract audiences, and the NRK news department’s refusal to refer its audiences to MCH’s own media platforms.

Public participation in AV

The most salient element to consider when shedding light on the opportunities for public participation in AV would be the Q&A sessions. Here the public could give feedback to the archaeologists and journalists beyond mere commentary. Both Havgar and Espen were directly involved with the audience, answering questions and follow-ups while the stream was live. Rødsrud was also involved in dialogues with Havgar and Espen, to answer questions as accurately as possible. The question, then, is whether this entails contributory participation, collaborative participation, or co-creative participation as outlined by Bonacchi (Citation2017). When looking at the questions and answers in the Q&A it is evident that the participants, both the public and the on-site archaeologists, engaged in interpretive activities related to what was happening in the stream. People asked questions to better understand what they were witnessing, and there were some examples of questions that challenged Havgar to elaborate more on the interpretive work-in-progress being undertaken by the archaeologists. One example is a question concerning evidence of a ‘mast partner’, signifying whether the ship would have had sails. Another is a question concerning the location of the burial chamber. One questioner asked: ‘Midships, the archaeologists have found some structures … could it be part of the burial chamber?’ Havgar answered: ‘Hi … we think that’s actually true! The archaeologists are digging where we are now becoming more and more certain that a burial chamber probably has been’. Even if the relationship was far from equal when it came to authority and knowledge, the running Q&A can be characterized as open, ongoing, informal, and reciprocal, thanks to the combined efforts of Havgar and Espen. Using Bonacchi’s (Citation2017) taxonomy of models of digital public archaeology, the public participation in the Q&A sessions were more than mere commentary as described by the broadcasting model, and less than what could be described by one of the three participatory models. What comes closest, though, is ‘collaborative participation’ with the public engaging with the interpretations being made on site. There were, however, no examples of questions posed in the Q&A that triggered the need for reinterpretation by the archaeologists. The rest of the elements — livestream, live reporting (with and without celebrities), and the production of news for multiple platforms — gave few opportunities for participation by the public, other than as passive consumers. This, then, can be easily classified as transmission of messages from a sender to receiver through a certain type of medium, i.e. according to Bonacchi’s (Citation2017) broadcast model. In this, the archaeologists were given and performed their usual roles as experts, translating the process and material evidence for the public with journalists as intermediaries. This can be squarely characterized according to the deficiency or gateway model, rather than the ivory tower model as outlined by Grima (Citation2016: 51–53).

Celebrities as intermediaries

How the AV’s use of celebrities as intermediaries structured the relationship between archaeologists and the public deserves consideration. NRK’s stated rationale for bringing in well-known representatives of how Vikings are portrayed in popular media in dialogue with researchers was to reach under-represented audiences and more specifically the hard-to-get younger viewers (under thirty) who traditionally do not engage with archaeology. When Tormund Giantsbane visited (Kristofer Hivju’s Game of Thrones role), NRK’s team saw an opportunity for reaching such a demographic and used the mishaps to create attention online,Footnote2 as described in the results section (Live feed studio summaries). At the same time, this can be understood as conveying a lack of respect for the accurate and highly accountable work archaeologists do. Rhetorically, it is possible to see how in this case increased engagement does not necessarily support a meaningful relationship between the archaeologists and the public. The incident with Hivju and how it was used to attract the wider public highlights the dilemma often surfacing when using celebrities as intermediaries, of shifting focus away from the archaeologists’ referential knowledge (Frank, Citation2003; Holtorf, Citation2007: 151–52) in letting the celebrity appeal to their audiences.

Recently, the National Museum of Denmark experienced this dilemma when using the celebrity designer Jim Lyngvild to attract attention by commissioning him to refurbish their Viking exhibition. This resulted in many critics praising the design, but also questioning why this was handled by an outsider, if it provided advertising space for a celebrity, or if the museum was risking its reputation in pursuit of publicity? Søren Sindbæk (Citation2019: 257) rightfully criticized the museum for the lack of control by expert curators as Lyngvild was given a free hand with everything except the texts, in the worst case reducing the display to pure entertainment or myth. Dialogue between fact (curators) and fiction (designer) would have made the terms clearer to the visitors and played well to the idea of a celebrity-driven exhibition. In a reply, three museum curators stressed that museums are no longer ivory towers where relics of distant ages are safely kept, but rather need to respond to a changing social environment and interact more with the audience (Pentz, et al., Citation2019). A lesson learned from Denmark clearly seems that a more dynamic collaboration between all parties involved would have allowed for an even better mix of popular culture and scholarly facts.

The Gjellestad incident triggered the need by the archaeologists to certify more control over subsequent visits, both to secure the excavation site and to ensure that archaeological knowledge was not undermined in the process of reaching out broadly. To frame it according to the matter of concern here, the archaeologists needed a more direct relationship with the AV viewers, to keep the relationship with the public meaningful with enough focus on the archaeological facts. This need has been articulated by Jeremy Sabloff (Citation2016: 106) when arguing that much could be gained if ‘professional archaeologists routinely helped to write and even host many of the archaeology shows on television’. Although the archaeologists’ concerns were real and legitimate, there is also a case to be made for the beneficial aspect of pop-culture relevancy. Making archaeology fun and relevant with the help of celebrities trying to entertain rather than understand could have the potential to reach beyond a standard museum demographic for better equality, diversity, and inclusion. Further, an enthusiastic but not necessarily accurate or careful film star turned hobby archaeologist might encourage members of the public to develop their own enthusiasm and interest in archaeology (Holtorf, Citation2007: 158–61).

Reaching and building a community?

The last aspect to highlight and discuss is how AV structured or restructured MCH’s longer term relationship with its audiences after the production week. There is no doubt that the collaboration supported them in making one of the most important archaeological events of the last 100 years available to the wider public — with one million views or uses of everything published on NRK’s platforms under the AV umbrella on NRK.no, social media, television, and radio. Further, since NRK explicitly aimed at younger audiences on their Snapchat platform, MCH reached an audience practically out of bounds on their own platforms. Without hesitation, MCH duly linked everything AV in their channels: the MCH home page, their Facebook page, and Instagram. NRK, however, with reference to their editorial policies and independent position as one of Norway’s dominant newsrooms, refused to link back to MCH’s online resources. Havgar, who proposed this multiple times, was a bit surprised by their response. Reciprocal linking to the respective partners had not been touched upon during the planning of the week, and as neither Havgar nor Rødsrud were intimately familiar with NRK’s editorial policies, Havgar had, perhaps naively, assumed that NRK would naturally link back to MCH as the museum did to NRK. Despite multiple efforts on her part and on Alex’s, the eventual response from central NRK was that this would not happen. That being said, the on-site journalists were positive to linking to the museum’s channels, but indicated that restrictions were imposed ‘higher up’ in their hierarchy and that their hands were tied in this regard. This linking practice was obviously advantageous to NRK, by keeping viewers/users on their platform during the week. The lack of reciprocity in linking practices is unfortunate since the increased reach on NRK’s platforms could potentially have been converted to a larger and broader following for the excavation, participating in the ongoing work.

The takeaway from this for museums collaborating with PSM newsrooms is to explicitly negotiate how the increased reach of PSM can help build a larger online following on their own channels and familiarize themselves with the editorial and backlinking policies of the newsroom in question. The PSM newsroom will always refer to the need for editorial independence, control, and their platform policies when refusing to link back. The museums, as a result, will need to develop and argue techniques for two-way linking practices that do not interfere with PSM newsroom’s editorial independence. Important in this is to make sure that it is made explicit what is edited by archaeologists only and what has gone through additional editorial and critical treatment by independent journalists. Such practices could support the development of mutual trust between archaeologists and journalists and open more reciprocal linking practices and co-creative projects in the future.

Conclusion

In this paper we have examined how collaboration with Public Service Media in NRK’s ‘Always Viking’ structured the archaeologists’ opportunities to have meaningful encounters with the public during the Gjellestad excavation. Most of the production was undertaken in broadcast mode with a broad and shallow reach, giving the archaeologists roles as experts according to the ivory tower and deficit models (Grima, Citation2016). It is possible to understand the archaeologists’ roles in AV mostly as a continuation of how these roles have been described in earlier research on archaeology in Public Service Broadcasting (Clack & Brittain, Citation2007; Kulik, Citation2006; Rogers, Citation2019). Further, it seems that journalists continued to rely on archaeology’s strong position in popular culture, its archaeo-appeal (Holtorf & Green, Citation2005), to reach the broader public, something that became pronounced in how they used celebrity visits to promote the production, in friction with the archaeologists’ need to secure the site and convey a professional foundation to the public.

The Q&A together with the livestream, however, opened new opportunities for establishing participatory and more reciprocal archaeologist–public encounters, where the archaeologists were allowed to communicate directly with NRK’s viewers or users. Analysing the 412 questions and answers, it is evident that the Q&A invited people to take on the roles of citizens rather than consumers in the exchange with Havgar and Espen, with most of the questions and comments being serious and relevant to the ongoing excavation and interpretation of the emerging facts. This example signals a new potential for future collaborations between archaeology and Public Service Broadcasting that is redefining itself to become Public Service Media, and how a common search for new participatory models of communication online can benefit both parties. Public Service Media providers can achieve their goals of ‘contributing to a flourishing digital commons and provid[e] content across multiple platforms to diverse publics’ (Flew, Citation2011: 215), and providing politically and socially relevant participation to their audiences (Donders, Citation2021: 84). Archaeologists, for their part, can explore multi-perspective and participatory models of archaeologist-public encounters contributing to developing the methodological approach of public archaeology (Schadla-Hall, Citation1999; Moshenska, Citation2017).

The main barriers to the collaboration between these institutions, which surfaced in this study, were the journalists’ insistence on editorial independence when it came to handling its visiting celebrities and their unwillingness to refer viewers or users on their platform to the museum’s own platforms. The rationale for editorial independence is unassailable in a democratic society, but the economic rationale for not establishing outbound links to collaborators is in our view undefendable. The question, then, is whether both incidents signify a power imbalance between the MCH and NRK in the AV collaboration. It is possible to argue that in these cases MCH ceded control to NRK to ensure that the AV was produced. The archaeologists needed the journalists to disseminate the event broadly. At the same time, it was evident that the journalists had great respect for the work going on at the site and tried to accommodate the archaeologists’ requests, i.e. the placement of microphones. In general, both parties seemed to meet any request with a will to collaborate and to make compromises. Further, we do not believe archaeologists should insist on gaining more direct control in such collaborations. That would be to hold on to the older top-down communication models in archaeology. They should welcome participation by journalists and the public in speculating and interpretating their objects of study and see their role as supporting any imagination triggered by the archaeological work and still try to keep the speculation within reasonable limits.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joakim Karlsen

Joakim Karlsen is an associate professor at the Faculty of Computer Sciences, Engineering and Economics at Østfold University College. He has focused on developing sound theoretical understandings of cultural and media work and how this work is adapting to new media technologies. Currently, he researches the collaborative practice of designing compelling and meaningful museum experiences, as part of the project pARTiciPED, funded by the Research Council of Norway (2021–23).

Margrethe Havgar

Margrethe Havgar is an archaeologist based in the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo. Her main areas of interest are pre-Christian cosmology, iconography, and burial customs, human–non-human relations, and archaeological dissemination. She is currently working on her PhD thesis within the multidisciplinary research project TexRec — Virtual Reconstruction, Interpretation and Preservation of the Textile Artifacts from the Oseberg Find, funded by the Norwegian Research Council (2021–25).

Christian. L. Rødsrud

Christian Løchsen Rødsrud is an archaeologist based in the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo where he currently works as an advisor and regularly leads archaeological excavation projects. He completed his PhD at the University of Oslo in 2012 on the topic of Iron Age pottery and the ritualized feasting culture of the elite. His main research interests include burial practices, settlement and society, social networks and early urbanism, cultural hybridization and studies of past within the past.

Notes

1 A tool within the Facebook platform for creating landing pages dedicated to organizing and communicating information about time-specific events. These are ‘hosted’ by a Facebook account, such as an organization’s account or a personal user account.

2 We have no data on whether this strategy worked or not.

References

- Angrosino, M. 2007. Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research. Kindle Edition. Qualitative Research Kit. London: SAGE Publications.

- Belair-Gagnon, V., Nelson, J.L., & Lewis, S.C. 2019. Audience Engagement, Reciprocity, and the Pursuit of Community Connectedness in Public Media Journalism. Journalism Practice, 13(5): 558–75.

- Björdal, C.G. 2019. Undersökning Av Ett Trädprov från Gjellestadvraket. Nedbrytning och Status. Institutionen för marina vetenskaper, Göteborgs universitet.

- Bonacchi, C. 2017. Digital Media in Public Archaeology. In: G. Moshenska, ed. Key Concepts in Public Archaeology, 60–72. London: UCL Press.

- Clack, T. & Brittain, M. 2007. Introduction: Archaeology and the Media. In: T. Clack and M. Brittain, eds. Archaeology and the Media, 11–67. New York: Routledge.

- Creswell, J.W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Donders, K. 2019. Public Service Media Beyond the Digital Hype: Distribution Strategies in a Platform Era. Media, Culture & Society, 41(7): 1011–28.

- Donders, K. 2021. Public Service Media in Europe: Law, Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Enli, G.S. 2008. Redefining Public Service Broadcasting: Multi-Platform Participation. Convergence, 14(1): 105–20.

- Flew, T. 2011. Rethinking Public Service Media and Citizenship: Digital Strategies for News and Current Affairs at Australia’s Special Broadcasting Service. International Journal of Communication, 5(2011): 215–32.

- Frank, S. 2003. Reel Reality: Science Consultants in Hollywood. Science as Culture, 12(4): 427–69.

- Grima, R. 2016. But Isn’t All Archaeology ‘Public’ Archaeology? Public Archaeology, 15(1): 50–58.

- Gruber, G. 2017. Contract Archaeology, Social Media and the Unintended Collaboration with the Public — Experiences from Motala, Sweden. Internet Archaeology, 46.

- Her går det galt for Kristofer Hivju. 2020. [online] [Accessed 12 April 2023]. Available at: <https://www.nrk.no/video/her-gaar-det-galt-for-kristofer-hivju_44756f3f-0fa4-460f-b281-968dff8ab1e0>.

- Holtorf, C. 2007. Can You Hear Me at the Back? Archaeology, Communication and Society. European Journal of Archaeology, 10(2–3): 149–65.

- Holtorf, C. & Green, T. J. 2005. From Stonehenge to Las Vegas: Archaeology as Popular Culture. Rowman Altamira.

- Kulik, K. 2006. Archaeology and British Television. Public Archaeology, 5(2): 75–90.

- Merriman, N. 2004. Public Archaeology. London and New York: Routledge.

- Moe, H. 2008. Dissemination and Dialogue in the Public Sphere: A Case for Public Service Media Online. Media, Culture & Society, 30(3): 319–36.

- Moshenska, G., ed. 2017. Key Concepts in Public Archaeology. London: UCL Press.

- Oldham, M., 2017. Bridging the Gap: Classification, Theory and Practice in Public Archaeology. Public Archaeology, 16(3–4): 214–29.

- Pentz, P., Varberg, J., & Sørensen, L. 2019. Meet the Vikings: For Real! Antiquity, 93(369): e19.

- Piccini, A. 2007. Faking It: Why the Truth Is So Important for TV Archaeology. In: T. Clack and M. Brittain, eds. Archaeology and the Media, 221–36. New York: Routledge.

- Robson, C. 2002. Real World Research, 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing.

- Rødsrud, C. 2020. Prosjektbeskrivelse. Arkeologisk undersøkelse av Gjellestadskipet Gjellestad vestre/nordre (26/1), Halden kommune, Viken. Kulturhistorisk Museum.

- Rogers, K.E. 2019. Off the Record: Archaeology and Documentary Filmmaking. Phd thesis, University of Southampton.

- Sabloff, J.A. 2016. Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World. New York: Routledge.

- Schadla-Hall, T. 1999. Editorial: Public Archaeology. European Journal of Archaeology, 2(2): 147–58.

- Sindbæk, S.M. 2019. ‘Meet the Vikings’ — or Meet Halfway? The New Viking Display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Antiquity, 93(367): 256–59.

- Solås, S.V., Fange, P.Ø. & Bjørke, C.N. 2020. Gjellestadskipet er trolig fra tidlig vikingtid — og angrepet av sopp. NRK [online], 17 January [accessed 19 April 2023]. Available at: <https://www.nrk.no/osloogviken/gjellestadskipet-er-trolig-fra-tidlig-vikingtid-_-og-angrepet-av-sopp-1.14862801>.

- Sprus, N. 2020. Vær sammen på NRK. 2020. NRK [online]. 19 March [accessed 19 April 2023]. Available at: <https://www.nrk.no/oppdrag/vaer-sammen-pa-nrk-1.14951745>.

- Wakefield, C. 2020. Digital Public Archaeology at Must Farm: A Critical Assessment of Social Media Use for Archaeological Engagement. Internet Archaeology, 55.