1. Introduction

Gastric adenocarcinoma (GAC) is a major global health problem with an estimated 951,600 new cases and 723,100 deaths in 2012 [Citation1]. Treatment of GAC depends on the stage at diagnosis. At early stage (e.g. stage I), it can be potentially cured by endoscopic therapy or minimal surgery; however, at more advanced stage (e.g. stages II and III), it requires adjunctive therapy, in addition to surgery [Citation2]. However, for all potentially curable cases, multidisciplinary evaluation and discussions are essential to determine the best initial approach. One should begin by completing thorough staging [Citation2]. Once the clinical stage is determined, a consensus should be developed for optimized therapy for all patients with localized GAC. We also emphasize that patients with localized GAC are best treated at high-volume centers and be operated by high-volume surgeons [Citation2]. Despite the application of multimodality treatment, recurrence rate is not negligible for localized GAC [Citation2]. Adjunctive approaches vary in different regions of the world such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy or postoperative chemoradiotherapy are popular in the United States, pre- and postoperative chemotherapy is popular in Europe, and adjuvant chemotherapy in Asia [Citation2,Citation3]. For advanced-stage patients, outcome is more troublesome with an overall survival (OS) of less than 12 months despite the availability of active cytotoxic agents (fluoropyrimidines, platinum compounds, taxanes, and irinotecan) for GAC [Citation3]. Today, a fluoropyrimidine and a platinum combination with or without trastuzumab according to human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER)-2 status is the standard of care in the first-line setting for advanced GAC [Citation4]. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel is the suggested second-line therapy as this combination provides better benefit than ramucirumab alone which has a marginal/negligible effect [Citation5]. The survival prolongations provided by these agents are not satisfactory, and more targets and therapeutic agents need to be discovered.

2. Individual GAC profiling for personalized therapy

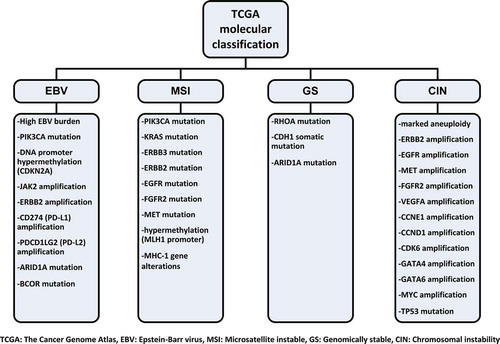

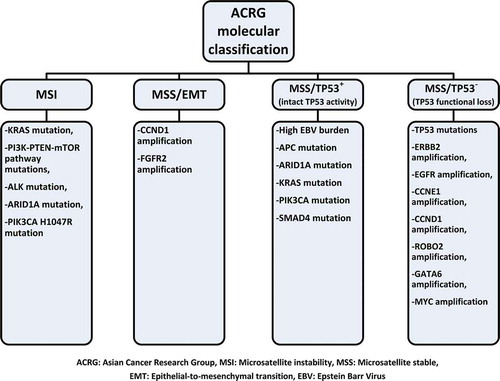

Histologic classification systems of GAC like Lauren (intestinal and diffuse types) and World Health Organization classification (papillary, tubular, mucinous, and poorly cohesive types) are often used for determining prognosis but not used for guiding treatment decisions. Despite the advances in staging procedures, patients at the same stage of GAC can have highly variable outcomes with the same therapy. As our understanding of cancer pathogenesis deepens, it is being realized that every GAC can have different genetic, molecular, and immunologic characteristics and these will need to be considered. In 2012, Deng et al. reported molecular analysis of small number of GAC [Citation6]. They showed 22 recurrent genomic alterations in GAC, but particularly, amplifications in fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)2 were sensitive to dovitinib (TKI258). Shortly thereafter, in 2014, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project reported molecular classification for GAC [Citation7]. Four genetic subtypes were identified according to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) status, microsatellite instability (MSI) status, and level of somatic copy-number aberrations: (1) tumors positive for EBV (9%), (2) MSI (22%), (3) genomically stable tumors (20%), and (4) tumors with chromosomal instability (50%), all with different potential therapeutic targets () [Citation7,Citation8]. The molecular classification of Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) [Citation9] was more limited than that of TCGA; however, ACRG also reported four subtypes () with slightly different characteristics than TCGA but also having an overlap with TCGA [Citation8]. After the demonstration of durable and highly beneficial effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors in malignant melanoma, lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma, there are many efforts to demonstrate the benefits of these agents in GAC.

3. Established targeted drugs and ongoing studies

HER-2 overexpression in GAC does not appear to be prognostic; however, there is some benefit to the addition of trastuzumab to combination chemotherapy in patients with HER-2-positive GAC. In the Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer (ToGA) trial, adding trastuzumab to standard first-line treatment showed a survival benefit (median OS: 13.8 vs. 11.1 months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.60–0.91; p = .0046) () [Citation4]. This benefit considerably reduced after additional follow-up analysis by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Unfortunately, other anti-HER-2 agents such as lapatinib (LOGIC, TyTAN) and TD-M1 (GATSBY) could not show any survival benefit in large phase III trials, and the results of the trial that compares two trastuzumab dosing regimens (HELOISE) and the study of pertuzumab in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy (JACOB) are awaited [Citation10]. Another established target in GAC is angiogenesis pathway. The phase III trials (AVAGAST and AVATAR), exploring the benefit of adding bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A antibody, to the first-line treatment of advanced GAC did not show any survival benefit. However, ramucirumab (fully human immunoglobulin G1 antibody against VEGF receptor-2) showed a marginal but statistically significant survival advantage as a single agent compared to placebo (median OS: 5.2 vs. 3.8 months; HR: 0.776; 95% CI: 0.603–0.998; p = .047) in the second-line setting in the REGARD trial [Citation11]. Ramucirumab with paclitaxel produced much better survival advantage compared to paclitaxel alone (median OS: 9.6 vs. 7.4 months; HR: 0.807; 95% CI: 0.678–0.962; p = .017) in the second-line setting in the RAINBOW trial [Citation5]. In 2014, the FDA approved ramucirumab both alone and in combination with paclitaxel as second-line agent for the treatment of advanced GAC. The third positive phase III study targeting angiogenesis pathway was recently reported with a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor apatinib for previously heavily pretreated advanced GAC patients (median OS: 6.5 months for apatinib vs. 4.7 months for placebo; HR: 0.709; 95% CI: 0.537–0.937; p = .0149) () [Citation12]. However, apatinib is approved only in China. Unfortunately, some other studies targeting other promising molecules did not meet expectations. Phase II trial targeting FGFR2 (SHINE) and phase III trials targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (REAL-III and EXPAND), mesenchymal epithelial transition factor (RILOMET-1, RILOMET-2, and METGastric), and mammalian target of rapamycin (GRANITE) could not meet their primary endpoint [Citation10]. Some of these negative results can be related to the unselected (not biomarker enriched) patient population (AVAGAST, AVATAR, REAL-III, EXPAND, GRANITE), inaccurate method to detect biomarker, or incorrect biomarker for enriching the patient population. There may be many other factors influencing the failure of targeted therapies in selected patient populations and should be investigated with new well-designed trials.

Table 1. Summary of positive phase III targeted therapy trials in gastric adenocarcinoma.

One of the most promising treatment modality for GAC is immunotherapy. Immune checkpoint inhibition through cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein (CTLA)-4, programmed death (PD)-1, and programmed death-ligand (PD-L)1 forms the basis of current immunotherapy. Tremelimumab and ipilimumab are the anti-CTLA-4 antibodies that were investigated in phase II trials of GAC and did not show any survival benefit [Citation13]. Nonetheless, early-phase trials of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 were more encouraging. In gastric cohort of KEYNOTE-012 phase 1b trial, overall response rate for 36 evaluable patients was 22% and median duration of response was 40 weeks to anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab with manageable toxicity profile [Citation14]. Phase II (KEYNOTE-059) and phase III (KEYNOTE-061 and KEYNOTE-062) trials evaluating pembrolizumab in GAC are ongoing (). Another anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab also showed encouraging results with 14% overall response rate alone and 26% with ipilimumab in recently reported phase I/II CheckMate-032 trial [Citation15]. According to TCGA data, the EBV-associated subgroup due to amplification of PD-L1 and PD-L2 and the MSI subgroup due to high mutation rates that causes neoantigens may be ideal candidates for immune checkpoint inhibition [Citation7]. Immune profiling of tumors of that subgroup of patients will help to determine the most appropriate patient group that can benefit from immunotherapy.

Table 2. Ongoing phase III trials of targeted therapies in different stages of gastric adenocarcinoma.

4. Expert opinion

GAC is a highly heterogeneous disease in terms of etiologic and histologic differences. TCGA has uncovered four molecular subtypes. Standard approaches are generally very unsatisfactory. Only limited number of agents are available to treat patients with advanced GAC. Personalizing therapy in patients with GAC will remain challenging for some years to come until much more detailed understanding of molecular and immunologic understanding is achieved. Newer efforts such as Personalized Antibodies for Gastro-Esophageal Adenocarcinoma (PANGEA-IMBBP, NCT02213289) and Targeted Agent eValuation in gastric Cancer basKeT KORea (VIKTORY, NCT02299648) trials also remain challenging. One can remain optimistic that future trials with more promising agents will produce better results. We have summarized a few completed trials () and several ongoing () phase III targeted therapy trials.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108.

- Elimova E, Ajani JA. Surgical resection first for localized gastric adenocarcinoma: are there adjuvant options? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3085–3091.

- Elimova E, Shiozaki H, Wadhwa R, et al. Medical management of gastric cancer: a 2014 update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(38):13637–13647.

- Bang Y-J, van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697.

- Wilke H, Muro K, van Cutsem E, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(11):1224–1235.

- Deng N, Goh LK, Wang H, et al. A comprehensive survey of genomic alterations in gastric cancer reveals systematic patterns of molecular exclusivity and co-occurrence among distinct therapeutic targets. Gut. 2012;61(5):673–684.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513(7517):202–209.

- Fontana E, Smyth EC. Novel targets in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer: a perspective review. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8(2):113–125.

- Cristescu R, Lee J, Nebozhyn M, et al. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 2015;21(5):449–456.

- Lee J, Bass AJ, Ajani JA. Gastric adenocarcinoma: an update on genomics, immune system modulations, and targeted therapy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:104–111.

- Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9911):31–39.

- Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448–1454.

- Bockorny B, Pectasides E. The emerging role of immunotherapy in gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Future Oncol. 2016;12(15):1833–1846.

- Muro K, Chung HC, Shankaran V, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with PD-L1-positive advanced gastric cancer (KEYNOTE-012): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):717–726.

- Janjigian YY, Bendell JC, Calvo E, et al. CheckMate-032: phase I/II, open-label study of safety and activity of nivolumab (nivo) alone or with ipilimumab (ipi) in advanced and metastatic (A/M) gastric cancer (GC). 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting; 2016 June 3–7; Chicago, Illinois.