1. Introduction: definition, prevalence, and impact of pediatric functional dyspepsia

Dyspepsia in Greek means bad digestion. Functional dyspepsia (FD) refers to upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (including epigastric pain or burning sensation, early satiety, and postprandial fullness) that are unrelated to bowel movements and are unrelated to another etiology to explain these symptoms. Rome criteria are used in adults and children to diagnose functional GI disorders (FGID), including FD.

The criteria for the diagnosis of FD have evolved over time; Rome IV identified, for the first time, epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) as two subtypes of FD in children, as recognized in adults [Citation1]. Symptoms have to be present at least 4 days per month for 2 months to diagnose FD. PDS is defined as postprandial fullness/early satiation that interferes with completion of a meal and could be associated with upper abdominal bloating or nausea. EPS is a pain or burning sensation localized to the epigastrium that can be induced or relieved by ingestion of a meal and can occur while fasting.

FD affected 23–31% of children who had recurrent upper abdominal pain in a school-based survey [Citation2]. FD is the second most common FGID in children after irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); about 4.5% of children worldwide experience symptoms of FD sometime in their life [Citation3]. As with other FGID, FD in children can be associated with significant morbidity, and symptoms can have a negative impact on the child’s quality of life (QOL), negatively affecting school attendance. There are also significant health-care costs associated with FD; one study estimated $6000 average cost for assessment of any child with FGID, including FD [Citation4].

2. Etiology and pathophysiology of pediatric functional dyspepsia

FD should be considered as a biopsychosocial disorder with multiple etiological factors. A triggering event such as infectious gastroenteritis is commonly identified. Pathophysiological features include altered upper GI motility, mucosal disturbances, and visceral hypersensitivity, with psychosocial stressors and mood disorders altering and modulating the severity of symptoms. Indirect and direct evidence suggests that acid hypersecretion is not a feature of recurrent abdominal pain [Citation5], but this may not reflect EPS.

Abnormalities in gastric emptying (GE) and gastric accommodation (GA) have been described in children with FD [Citation6]. More frequent and worse symptoms were found in patients with delayed GE and lower postprandial GA, estimated by the fed to fasting gastric volume ratios [Citation6] using SPECT imaging (which involves radiation exposure) and comparing results of pediatric FD patients to normal data in adults aged 18-25years.

Gastric visceral hypersensitivity has been demonstrated in children with FD using a gastric barostat. Fifty percent of FD patients had epigastric discomfort at lower balloon pressure and volume [Citation7] compared with normal values in young adults (18–22 years). In this mechanistic study, patients with reduced GA had more early satiety, and those with visceral hypersensitivity had more epigastric pain. The dysfunctions of reduced accommodation and gastric hypersensitivity can be noninvasively assessed by a nutrient drink test [Citation8].

Recently high-resolution gastric manometry has been developed to assess gastric accommodation, by measuring intragastric pressure changes in response to ingestion of nutrition drink in children with FD. This form of high-resolution manometry is a less invasive test than barostat and does not include radiation exposure, in contrast to SPECT measurement of gastric accommodation [Citation9].At the level of mucosal structure and function in children with FD, there are conflicting data suggesting altered mucosal permeability leading to chronic inflammation with increased eosinophils in the upper GI tract and mast cells degranulation [Citation10].

Patients with FGID including FD have higher rates of anxiety, depression, poor coping skills, and somatization symptoms compared to children without FGID. Moreover, parents of children with FGID have psychopathology symptoms one standard deviation higher than those of non-psychiatric patients [Citation11].

Abnormalities in gastric sensory and motor function may be helpful in managing patients and guiding therapy, but they do not necessarily classify patients into the clinically recognized subgroups of FD, as there is significant overlap in the pathophysiology between the FD subgroups of EPS and PDS [Citation12].

3. Pharmacological, behavioral and complementary medical therapy

3.1. General comments

Pharmacological approaches target the underlying pathophysiology of FD and include antacid therapy, drugs enhancing accommodation, neuromodulators, and prokinetic agents (summarized in ).

Table 1. Available Medications for Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia in Children.

A systematic review evaluated evidence on the efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments of FD in children [Citation13]. Three randomized controlled trials (256 children with FD, 2–16 years of age) were included and all showed a considerable risk of bias. Compared with baseline, successful relief of dyspeptic symptoms was observed with omeprazole (53.8%), famotidine (44.4%), ranitidine (43.2%), and cimetidine (21.6%) (p = 0.024). Compared with placebo, famotidine showed benefit in global symptom improvement (OR 11.0; 95% CI 1.6–75.5; p = 0.02). Compared with baseline, mosapride reduced global symptoms compared to pantoprazole (p = 0.011; p = 0.009, respectively). The authors concluded that more high-quality clinical trials are needed [Citation13].

Therefore, pharmacotherapy for dyspepsia in the pediatric age group is based predominantly on open-label studies, expert opinion, and extrapolation from experience in adults with dyspepsia.

3.2. Specific comments on available therapies

3.2.1. Acid suppression

In a large cohort of 169 children, aged 2-16 years, the proton pump inhibitor (PPI), omeprazole, and diverse H2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) administered over a treatment period of 4 weeks reduced symptom severity in FD, with omeprazole being more efficacious for pain [Citation14], and the H2RAs and the PPI being highly efficacious for nausea and/or vomiting relief.

3.2.2. Histaminic and serotonergic approaches

Cyproheptadine, an antagonist of serotonin, histamine H1, and muscarinic receptors, is commonly used in children with FD, and its effects are attributed to gastric fundus relaxation (not proven) and appetite stimulation. Cyproheptadine appears to be a safe, generally well-tolerated medication that facilitates weight gain in underweight pediatric patients, based on a systematic review [Citation15]. Cyproheptadine has also been shown to be safe and efficacious in relief of FD in an open-label study of 80 children, with greater benefit in females, children younger than 12 years of age, and those with early satiety [Citation16]; 30% experienced mild side effects including somnolence (16%), irritability and behavioral changes (6%), increased appetite and weight gain (5%).

Buspirone, 5-HT1A agonist, is an anxiolytic drug that enhanced GA in adults with FD [Citation17] and leads to symptom improvement, mainly in patients with PDS. Buspirone is generally safe and well-tolerated at doses up to 30 mg, bid, in adolescents and in most children with anxiety disorder [Citation18].

3.2.3. Central neuromodulators

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) are the most commonly used neuromodulators in FGID. In a large retrospective review, both amitriptyline and imipramine were helpful in children with FD, with up to 80% improvement on a follow-up to 44 months [Citation19]. TCA has the potential of QT prolongation, but low dose (10–25 mg, once at bedtime) has been generally regarded safe. In a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline in children (8–17 years of age) with FGID, both amitriptyline and placebo were associated with excellent therapeutic response, with no significant differences after 4 weeks of treatment [Citation20]. In adults with FD, amitriptyline works best in FD without delayed GE [Citation21].

In adults, the antidepressant, mirtazapine, in the placebo-controlled trial was efficacious in FD patients with weight loss, and it improved overall symptoms, mainly nausea and early satiety, through its predominantly central site of action [Citation22,Citation23]. There are no studies evaluating the effectiveness of mirtazapine in children with FD.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) have not been studied extensively in children with FD, but a placebo-controlled trial in adults showed that the SSRI, escitalopram, was ineffective compared to placebo, in contrast to amitriptyline, which was significantly more efficacious than placebo [Citation21].

3.2.4. Prokinetics

Prokinetic agents can be helpful in FD patients with delayed gastric emptying and in patients with PDS. Unfortunately, most drugs in this category (metoclopramide, domperidone, and cisapride) have not been studied extensively in children with FD, and they carry risks of side effects. Both domperidone and cisapride are not available for prescription in many countries. With the advent of newer 5-HT4 receptor agonists with no cardiac toxicity, it is hoped that this class of prokinetics might be available in the future for the treatment of FD and PDS in pediatric patients.

Erythromycin, a motilin receptor agonist, is the most wildly used prokinetic agent for delayed gastric emptying in children, but it has the potential of QTc prolongation. It is also susceptible to tachyphylaxis and may, therefore, lose efficacy over a few weeks.

3.2.5. Miscellaneous

Acotiamide is a newer cholinesterase inhibitor (approved in Japan) that enhances both GE and GA. It has shown benefit in adults with FD, especially PDS [Citation24].

Natural supplements such as melatonin, and herbal medications such as iberogast (STW5, derived from Iberis amara) and capsaicin (component of red pepper) have shown some benefit in adults with FD [Citation25].

Psychological therapies such as biofeedback, relaxation, cognitive behavioral therapy, guided imagery, and hypnotherapy have also been shown to be beneficial in children with FGID including FD [Citation26]. Biofeedback-assisted relaxation training with medication was superior to medication alone in a pilot study of 20 children with dyspepsia [Citation27].

4. Expert opinion

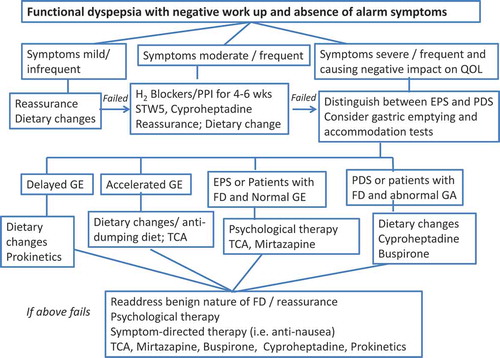

Management of FD in children should be tailored to the severity and frequency of symptoms, psychological comorbidity, and the degree of dysfunction associated with symptoms. This approach could avoid excessive testing and medication use. A detailed approach is summarized in .

If FD symptoms are mild, infrequent, and with minimal impact on QOL, it may be sufficient for the health-care provider to provide reassurance and explanation about the benign nature of FD in order to ease some of the patient’s concerns and anxiety about symptoms. Although often forgotten in the management of FD, simple dietary modifications such as smaller, more frequent meals and avoiding triggering foods might provide some symptom relief. Eating bland foods and cooking vegetables before ingestion may also help.

When symptoms are moderate in severity, with increased frequency, but with no significant impact on QOL, a 4–6 week trial of a PPI or H2RA is reasonable. Herbal supplements such as iberogast can also be tried as a single intervention or in combination with a PPI, if either medication fails when used alone. Given the benign profile of cyproheptadine, it can also be tried in this group of patients, especially those younger than 12 years of age.

A more comprehensive approach is needed in children with severe, frequent symptoms and those with significantly reduced QOL, leading to school avoidance and disrupted social life. Helpful noninvasive tests are measurements of GE (e.g. scintigraphy or stable isotope breath test) and of GA/hypersensitivity with a nutrient drink test or imaging methods (e.g. SPECT), but the latter are available in only a few centers. Prokinetic agents and an anti-dumping diet would be helpful for patients with delayed and accelerated GE, respectively. In children with abnormal GA and FD, PDS subtype, with early satiety; medications such as buspirone or cyproheptadine could be helpful. In patients with no abnormality in gastric function or FD, EPS subtype, a neuromodulator such amitriptyline or mirtazapine is recommended. Mirtazapine is particularly useful in patients with significant nausea and/or weight loss. In addition, psychological therapy should be utilized in patients with severe pain, impaired QOL, and associated mood disorders. Combination therapy addressing symptoms (i.e. nausea), pain, abnormal gastric function, and psychological therapy may be required in patients with refractory symptoms. Whereas gastric electrical stimulation has been suggested as helpful in children with FD, the mechanism of efficacy is still unclear [Citation28], and it is not recommended. Similarly, there should be no endoscopic intervention such as gastric per-oral endoscopic myotomy (G-POEM) for children with FD.

Measurements of gastric motor and sensory functions are helpful in guiding pharmacological therapy, as detailed above. However, in patients with severe refractory disease or when testing is not available, it is reasonable to use available pharmacotherapy regardless of the subtype of FD or abnormalities found in gastric motor or sensory functions, given the complexity and overlapping pathophysiology in children with FD.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, et al. Functional disorders: children and adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1456–1468.e2.

- Hyams JS, Burke G, Davis PM, et al. Abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: a community-based study. J Pediatr. 1996;129(2):220–226.

- Korterink JJ, Diederen K, Benninga MA, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders: a meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0126982.

- Dhroove G, Chogle A, Saps M. A million-dollar work-up for abdominal pain: is it worth it? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(5):579–583.

- Liebman WM. Gastric acid secretion and serum gastrin levels in children with recurrent abdominal pain, gastric and duodenal ulcers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1980;2(3):243–246.

- Chitkara DK, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Gastric sensory and motor dysfunction in adolescents with functional dyspepsia. J Pediatr. 2005;146(4):500–505.

- Hoffman I, Vos R, Tack J. Assessment of gastric sensorimotor function in paediatric patients with unexplained dyspeptic symptoms and poor weight gain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19(3):173–179.

- Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, et al. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14(3):249–253.

- Carbone F, Tack J, Hoffman I. The intragastric pressure measurement: a novel method to assess gastric accommodation in functional dyspepsia children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):918–924.

- Friesen CA, Lin Z, Singh M, et al. Antral inflammatory cells, gastric emptying, and electrogastrography in pediatric functional dyspepsia. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(10):2634–2640.

- Robins PM, Glutting JJ, Shaffer S, Proujansky R, Mehta D. Are there psychosocial differences in diagnostic subgroups of children with recurrent abdominal pain? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(2):216–220.

- Vanheel H, Carbone F, Valvekens L, et al. Pathophysiological abnormalities in functional dyspepsia subgroups according to the Rome III criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):132–140.

- Browne PD, Nagelkerke SCJ, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, et al. Pharmacological treatments for functional nausea and functional dyspepsia in children: a systematic review. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(12):1195–1208.

- Dehghani SM, Imanieh MH, Oboodi R, et al. The comparative study of the effectiveness of cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and omeprazole in treatment of children with dyspepsia. ISRN Pediatr. 2011;2011:219287.

- Harrison ME, Norris ML, Robinson A, et al. Use of cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and body weight gain: a systematic review. Appetite. 2019;137:62–72.

- Rodriguez L, Diaz J, Nurko S. Safety and efficacy of cyproheptadine for treating dyspeptic symptoms in children. J Pediatr. 2013;163(1):261–267.

- Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, et al. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(11):1239–1245.

- Salazar DE, Frackiewicz EJ, Dockens R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of buspirone during oral administration to children and adolescents with anxiety disorder and normal healthy adults. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41(12):1351–1358.

- Teitelbaum JE, Arora R. Long-term efficacy of low-dose tricyclic antidepressants for children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(3):260–264.

- Saps M, Youssef N, Miranda A, et al. Multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(4):1261–1269.

- Talley NJ, Locke GR, Saito YA, et al. Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: a multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):340–349.e342.

- Tack J, Camilleri M. New developments in the treatment of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2018;43:111–117.

- Tack J, Ly HG, Carbone F, et al. Efficacy of mirtazapine in patients with functional dyspepsia and weight loss. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):385–392.e384.

- Matsueda K, Hongo M, Tack J, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of acotiamide for meal-related symptoms of functional dyspepsia. Gut. 2012;61(6):821–828.

- Romano C, Valenti S, Cardile S, et al. Functional dyspepsia: an enigma in a conundrum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(6):579–584.

- Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC, et al. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5:Cd003968.

- Schurman JV, Wu YP, Grayson P, et al. A pilot study to assess the efficacy of biofeedback-assisted relaxation training as an adjunct treatment for pediatric functional dyspepsia associated with duodenal eosinophilia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(8):837–847.

- Teich S, Mousa HM, Punati J, et al. Efficacy of permanent gastric electrical stimulation for the treatment of gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(1):178–183.